Machiavellianism, Job Autonomy, and Counterproductive Work Behaviour among Indian Managers

[Maquiavelismo, autonomía en el puesto y conducta contraproductiva en el trabajo entre managers indios]

Usama Rehman and M. G. Shahnawaz

Department of Psychology, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, India

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2018a10

Received 14 April 2017, Accepted 23 February 2018

Abstract

The present study explored the relationship between Machiavellianism and counterproductive work behaviour (CWB) through the lens of the social exchange theory. The present research further aimed at exploring the relationship between the two by introducing job autonomy as the mediator following trait activation theory. The Machiavellian personality scale was used to assess Machiavellianism, whereas a job autonomy scale was used to assess job autonomy, and counterproductive work behaviour was assessed with the help of the CWB questionnaire. Data was analysed using SPSS version 21 and Smart PLS version 2. Results showed that Machiavellianism is positively associated with counterproductive work behaviour and job autonomy did not act as a moderator in the relationship between the two.

Resumen

El presente estudio explora la relación entre el maquiavelismo y la conducta contraproductiva en el trabajo (CCT) desde la perspectiva de la teoría del intercambio social. Además, la presente investigación trató de explorar la relación entre las dos variables al introducir la autonomía en el puesto de trabajo como variable mediadora siguiendo la teoría de la activación del rasgo. La escala de personalidad maquiavélica fue usada para evaluar el maquiavelismo, mientras que la escala de autonomía en el puesto de trabajo se ha utilizado para evaluar la autonomía laboral, y la CCT se evaluó con la ayuda del cuestionario CWB. Los datos se analizaron utilizando SPSS versión 21 y Smart PLS versión 2. Los resultados mostraron que el maquiavelismo está asociado positivamente con la CCT y que la autonomía en el puesto de trabajo no actuó como moderadora en la relación entre maquiavelismo y CCT.

Palabras clave

Maquiavelismo, Conducta contraproductiva en el trabajo, Autonomía en el puesto de trabajo, Activación del rasgo.

Keywords

Machiavellianism, Counterproductive work behaviour, Job autonomy, Trait activation.

Cite this article as: Rehman, U. & Shahnawaz, M. G. (2018). Machiavellianism, job autonomy and counterproductive work behaviour among Indian managers. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 34, 83-88. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2018a10

Correspondence: usama.ktw@gmail.com (U. Rehman).

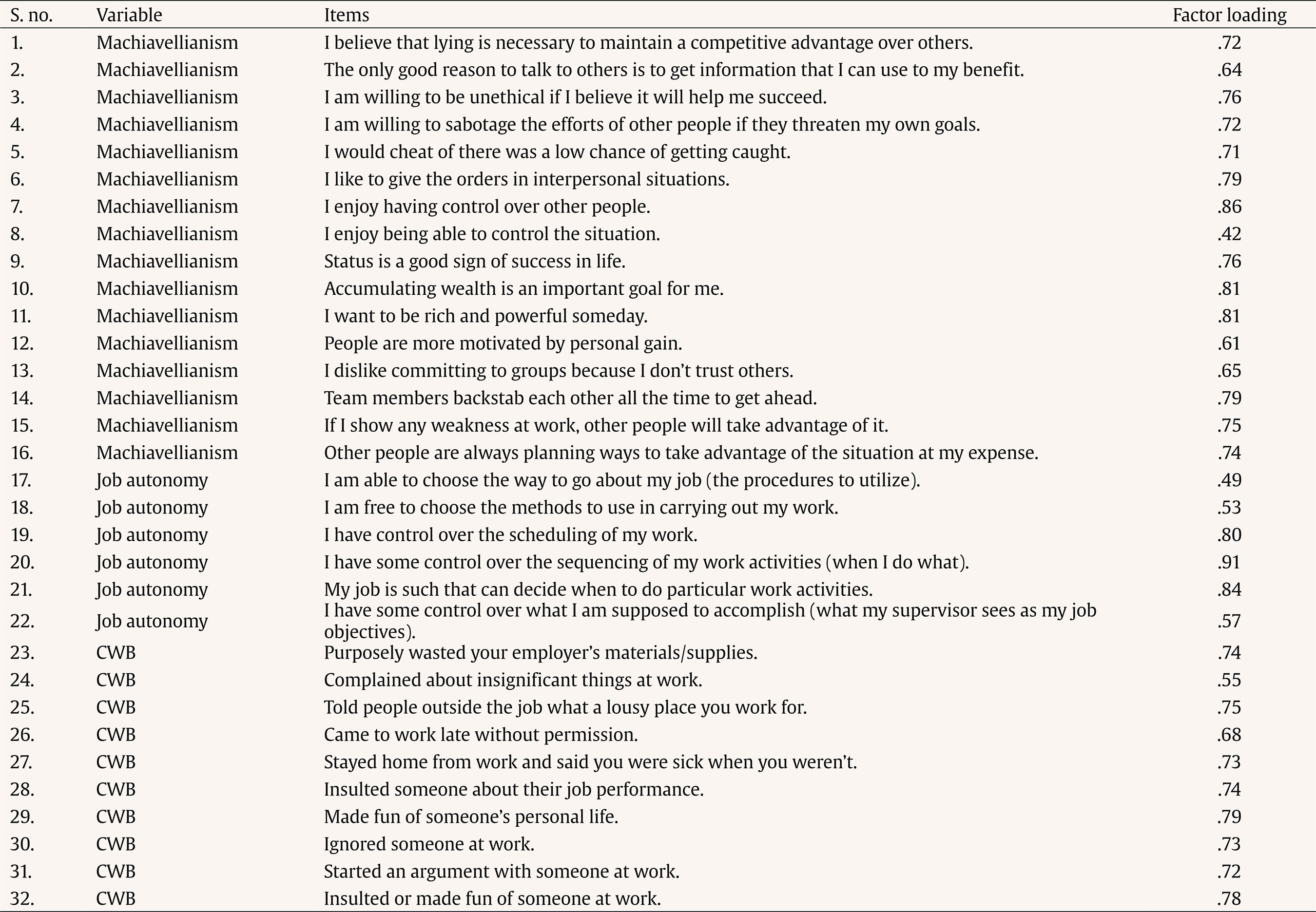

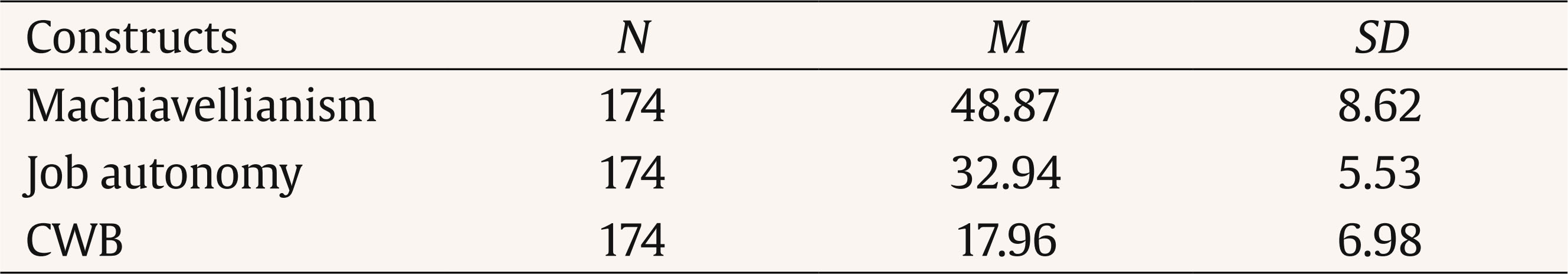

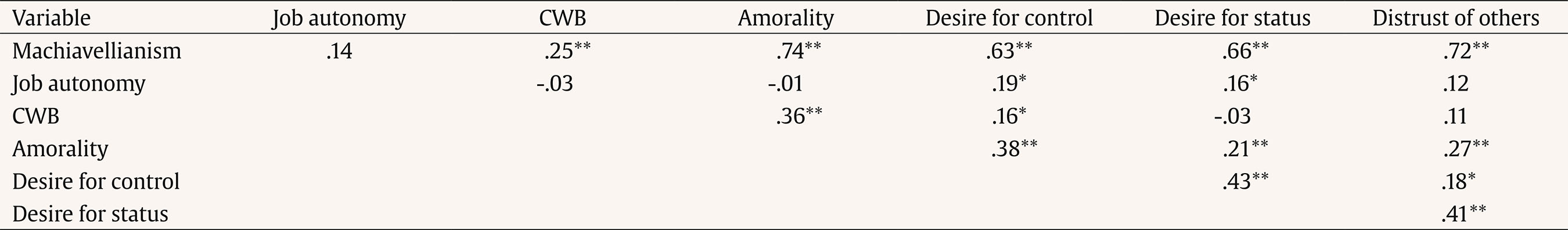

Introducción Christie & Gies (1970) defined Machiavellian as a person who has a cynical worldview, amoral orientation, and uses manipulative tactics to get work done in their favour. Later, Dahling, Whitaker, and Levy (2009) added new dimensions to Machiavellianism, such as seeking control over others and thriving for status for oneself. They have also developed a psychometrically sound tool named Machiavellian Personality Scale (MPS) to incorporate the extended framework of Mach and to overcome the problems of existing highly cited tool Mach IV. Machiavellianism, along with narcissism and psychopathy, forms an umbrella term commonly known as Dark Triad (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Because of the commonness among them, they have been clubbed together as “dark triad”. According to Paulhus and Williams (2002) “To varying degrees, all three entail a socially malevolent character with behaviour tendencies toward self-promotion, emotional coldness, duplicity, and aggressiveness” (p. 557). Recently, Mededov and Petrovi (2015) added sadism as a fourth dark personality, and together they are termed as Dark Tetrad. Machiavellianism or Machs are usually associated with negative outcomes. They are prone to take revenge (Nathanson, 2008), lie repeatedly (Kashy & DePaulo, 1996), are dissatisfied at work and emotionally distressed (Dahling et al., 2009), and would have high job turnover rates as compared to non Machs (Jones & Paulhus, 2009). Despite these negative outcomes, researchers acknowledge its positive side as well. Rubio (2016) wrote in his blog that despite negative attributes there are skills in Machiavellians which help develop critical and strategic thinking, which are quite essential for any managerial or leadership activity. According to him, great thinkers such as “Baruch Spinoza, Diderot, and Rousseau thought that there were positive things to learn from Machiavelli” (Rubio, 2016). Machs are chosen for the leadership roles when it comes to face the enemy or the opposition (Wilson, Near, & Miller, 1998). In a classic study by Deluga (2001) on American presidents, it was found that Machiavellians were preferred for their highest leadership role. Rehman, Shahnawaz, and Imran (2017) found clear association of Machiavellianism with task-oriented leadership style. It is debatable as whether Machs have short term (Wilson, Near, & Miller, 1996) or long-term life orientation. Jones and Paulhus (2009) strongly advocated that Machs have long term orientation and this has implications as whether they would indulge in strategic planning or building relationship or involving in counterproductive work behaviour. As the focus of the study is only on counterproductive work behaviour, a brief review is presented below. Giacalone and Knouse (1990) found that Machs indulge in counterproductive work behaviour (CWB), while Kessler et al. (2010) found that Machs do not like to indulge in counter productive work behaviour (CWB). Therefore, this needs to be explored further as counterproductive behaviour, such as theft, absenteeism, misuse of organization assets, and spreading rumours is quite common (Raman, Sambasivan, & Kumar, 2016). Theft alone as CWB costs $10 billion to $200 billion yearly to American organizations (iresearchnet.com. Psychology Research and Reference, 2017). As far as India is concerned, Karthikeyan and Thomas (2017) in their review paper concluded that India records highest number of unplanned absenteeism than any other country in the world, which impacts the employee´s performance as well as that of the organization. Organizational performance can be measured in two ways - task and contextual performance (Borman & Motowidlo, 1997). Task performance focuses on behaviours which are directly related to task and duties at work (Rotundo & Sackett, 2002), while contextual performance is the context in which tasks and duties take place. Employees who exhibit contextual performance voluntarily do tasks which are not directly related to their duty, such as OCB (organization citizenship behaviour) or CWB. In the present research, we focused on CWB only as it has not been explored much in the past. CWBs are behaviours which are intended to harm the organization. These acts are directed towards individuals, organization, or both. These acts include absenteeism, theft, sabotage, aggression (both verbal and physical), or withdrawal, etc. In general, these behaviours negatively affect organizational effectiveness (Lau, Au, & Ho, 2003). CWB not only influences the organizational effectiveness, but also creates an environment of mistrust and negative affectivity, which in turn affects task as well as contextual performance and employees’ wellbeing. Machiavellianism is not always directly related to job outcomes. The relationship between Machs and outcome depends on the organizational context. Machs are low on conscientiousness and bloom in unstructured environment, where rules are not explicitly communicated and situations can be exploited (Becker & O’Hair, 2007; Jones & Paulhus, 2009). There is also evidence that they perform badly in highly structured organizations (O’Connor & Morrison, 2001; Jones & Paulhus, 2009). To the best of our knowledge, an organizational context of flexibility/autonomy and rigidness has not been explored so far in the context of Machiavellianism and outcomes. Therefore, the present paper is a modest attempt to fill this gap in knowledge by exploring the relationship between Machiavellianism and counterproductive work behaviour by the introduction of job autonomy as the moderator. Theoretical Framework and Development of Hypotheses The social exchange and the trait activation theories have been used in the current research to conceptualize and develop the hypotheses. The social exchange theory can explain the process of how tasks and relationships are performed and with the exchange of rewards and recognition (O’Boyle, Forsyth, Banks, & McDaniel, 2012). In an organizational context, employees want to be rewarded as well as recognised in return of their performance for the organization (Settoon, Bennett, & Liden, 1996). However, Machiavellians do not see reward and compensation in a manner that is similar as perceived by others (O’Boyle et al., 2012). They usually violate the fair exchange of task and reward, which makes social exchange theory a possible lens to explore Machiavellians and their work-related outcomes (Blau, 1964; Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). Unlike others, Machiavellians would not prefer to put an extra effort in job, because they believe that they would not be paid extra for it (Gunnthorsdottir, McCabe, & Smith, 2002). Machiavellians are less likely to follow norms of the social exchange theory than others and thus are more likely to engage in personal forms of CWB (O’Boyle et al., 2012). Kish-Gephart, Harrison, and Treviño (2010) and Dahling, Kuyumcu, and Librizzi (2012) also found that higher levels of Machiavellianism were associated with an increase in unethical work place behaviour. Therefore, we hypothesize that Machiavellianism would be significantly associated with counterproductive work behaviour. H1: Machiavellianism would be significantly associated with counterproductive work behaviour. The relationship between personality trait and behaviour can be explained with the help of the trait activation theory (Tett & Guterman, 2000), which posits that the relationship is moderated by the strength (or demands) of the situation (Weiss & Adler, 1984). Job autonomy was introduced as a moderator, which could act as a trait activator, with Machiavellians resulting in unethical behaviour exhibition, because there would be no hard and specific norms to be followed. Managers high on conscientiousness and extraversion performed better in jobs with high autonomy compared with those managers in jobs, low in autonomy (Barrick & Mount, 1993). Whitaker and Dahling (2013) found that job autonomy is a significant moderator in the relationship of Machs and peer intimidation. Greenbaum, Hill, Mawritz, and Quade (2014) assessed the role of abusive supervision as a trait activator in the relationship of Machs and unethical behaviour and found support for this proposition. Rehman et al. (2017) found that job autonomy worked as a trait activator in the relationship of Machiavellianism and task-oriented leadership. We, therefore, hypothesize that job autonomy would facilitate Machiavellians to indulge in counterproductive work behaviour. H2: Job autonomy will act as moderator in the relationship between Machiavellianism and Counterproductive Work Behaviour. MethodSample Three hundred managers were approached for the study: 50 rejected to participate, while 76 never returned the questionnaire citing different reasons. Managers who rejected were mostly from banking industry. Finally, data were collected and analysed in 174 middle level managers, out of whom 49 were females and 125 were males, after they had signed a consent form. The participants were also briefed about the study. The mean age of the sample was 31.4, with 23 being the minimum and 59 being the highest. Data was collected from the organizations in and around the national capital region of Delhi, India. All the participants were Indian nationals: 78 participants were from different IT firms, 42 were from marketing, while 22 were from purely sales job profiles; 20 participants were HR managers, while 12 mangers were from export industry. The average number of subordinates under each manager was 12, while the range was 5 to 25. Their primary duty was to handle a team of subordinates and get the work done as per job requirements. Data Analysis The analysis was done using SPSS and Smart PLS version 2. Common method bias was analysed using Harman single factor test, which indicated that data is free from bias, as single factor only explained 18.5% of variance. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to check the validity of the tools before testing the moderation model. Factor loadings of all measures are shown in Table 1. Table 1 Showing Factor Loadings of the Items  Measures Machiavellianism. Machiavellian personality scale (Dahling et al. 2009) was used which consists of 4 dimensions, namely amorality, distrust, desire for control, and desire for status, measured by 16 items. Responses were collected on a 5-point likert scale, where 1 is strongly disagree and 5 is strongly agree. Factor loadings were found to be satisfactory. The average factor loading was .72 for all the items. The average variance explained and composite reliability were found to be .54 and .84 respectively. Croncbach’s alpha for the 4 dimensions of Machiavellianism were found to be .75 (amorality), .52 (desire for control), .70 (desire for status), and .75 (distrust of others). Job autonomy. It was assessed by the 9-item work autonomy scale of Breaugh (1999). The responses were captured on a 5-point rating scale. Three items were deleted one by one due to low factor loading during CFA. Only 6 Items were used for further analysis. The average factor loading of the remaining items was found to be .70. The average variance explained and composite reliability were also found to be .51 and .85 respectively. Counterproductive work behaviour. It was assessed by the 10-item questionnaire developed by Spector, Bauer, and Fox (2010). Responses were captured on a 5-point frequency scale. CFA results revealed good statistical features to use the scale. The average factor loading was found to be .72. The average variance explained and composite reliability was .52 and .91 respectively. ResultsDescriptive Table 2 shows the mean scores of 174 employees of private organizations. Table 2 Mean and Standard Deviation of the Study Variables  The mean score of Machiavellianism is 48.87, with a standard deviation of 8.62, which is almost the mean value of scale. The job autonomy mean score is 32.94, with 5.53 standard deviation. The score shows that people reported high job autonomy. The mean score of CWB is approximately 18 ,which is below average. Table 3 shows the correlations among the constructs and Machiavellianism dimensions. A correlation coefficient of .251 between Machiavellianism and CWB was found to be significant and positive. The relationship between Machiavellianism and job autonomy was found to be positive but insignificant (r = .14). All the dimensions of Machiavellianism, such as amorality (r = .74, p < .01), desire for control (.63, p < .01), desire for status (.66, p < .01), and distrust of others (.72, p < .01) strongly correlated with the latent construct (Machiavellianism). The dimensions of Machiavellianism had different relationships with job autonomy and CWB. Job autonomy had a non-significant relationship with amorality (r = -.01) and distrust of others (r = .12), while it shared a significant positive relationship with desire of control (r = .19, p < .05) and desire of status (r = .16, p < .05). However, both correlation coefficients were significant at .05 level, but low. CWB had a positive significant correlation with amorality (r = .36, p < .01) and desire for control (r = .16, p < .05) but had an insignificant relationship with desire for status (r = -.03) and distrust of others (r = .11). Table 3. Matrix of Observed Correlations among the Study Variables  To test the the two hypotheses formulated above, data were loaded into the Smart PLS version 2 and the results are presented below in Figures 1 and 2. To assess the relationship as per our hypotheses and to test the significance, the path coefficients were transformed into t-statistics using bootstrapping of 5,000 samples, as suggested by Hair, Hult, and Ringle (2013), as this is the standard way of interpreting the results from Smart PLS software. Figure 1 Path Diagram of the Relationship between Machiavellianism and CWB (path coefficients changed to t-statistics). Figure 2 Moderation Results (path coefficients changed to t-statistics). Figure 1 shows the path coefficients from a) the latent construct of Machaivellianism to four of its components and b) Machiavellianism to counterproductive work behaviour; t-values of 11.05, 8.87, 12.25, and 14.55, all significant at .01 level, imply that Machiavellianism has been significantly tapped by these four dimensions. This is totally in sync with the conceptualization of the Machiavellianism personality scale (Dahling et al., 2009). The t value of 4.559 is significant at .01 level, providing support for the H1 that Machiavellianism is a significant predictor of CWB. The result of moderation analysis in Figure 2 shows that job autonomy does not have a moderating effect. A new variable of a moderator (Mach * job autonomy) (light purple ellipse) has been created to test the moderation in smart PLS software. The calculated t value 1.351 is not significant at .05 level, indicating that moderation is not taking place. It implies that with the introduction of job autonomy as the moderator variable, the previous relationship between Mach and CWB, which was significant, becomes insignificant. This means that when autonomy is given in the organizational context, Machiavellians would not indulge in CWB. This result rejects H2. The possible reasons are discussed in the next section. DiscussionThe current study focused on the relationship between Machiavellianism and counterproductive work behaviour. The role of job autonomy was examined as the moderator between them. The study provided evidence that Machiavellians engage in counterproductive work behaviour. Machs do not believe in fair exchange rules in the organizations and involve in unethical behaviour (O’Boyle et al., 2012). Our first hypothesis has not been thus rejected. The same is also supported by the literature on Machiavellianism, which says that they engage in unethical behaviour (Dahling et al. 2012; Kish-Gephart et al., 2010). The result strengthens the existing body of knowledge by providing cross cultural evidence for it. Our study rejects the second hypothesis, as job autonomy did not act as a moderator. One possible reason could be that all the studies were done on a western sample and Indian self is different. Indian self is largely context specific (Roland, 1988; Sinha & Kanungo, 1997), collectivistic, as well as relational (Mascolo, Misra, & Rapisardi, 2004). Indians strive for status, are money conscious as well as long term planners (Verma, 2004); hence, the idea of morality changes from person to person and situation to situation. It can be inferred that when job autonomy is given, the onus is on the employee to complete the job in an efficient way and to make a name for themselves, as striving for status is one of the essential ingredients of Machs as well as for Indians (Verma, 2004). Another possible reason could be impression management. Lopes and Fletcher (2004) found that high Machs use impression management as a strategy to get the job during interviews. They could also tolerate unethical behaviour (Kaur & Dubey, 2015) if they think that it could be beneficial to them (Verma, 2004). Thus, we can say that as Machiavellians engage in impression management (Jaiswal & Bhal, 2014), when autonomy is presented, Machs may not likely engage in unethical behaviour. This could also be seen as a part of their long-term planning or strategic thinking, which is hinted by Jones and Paulhus (2009). This would eventually allow them to move ahead in the organization, which in turn will give them more power where the chances of being caught would be fewer. Conclusion and LimitationsThe study adds significant knowledge in the literature available on Machiavellianism. The study suggests that a Machiavellian engages in unethical behaviour, but the relationship disappears when job autonomy is introduced as the moderator. The direction of the relationship is different from what has been reported so far in the literature, thus more studies need to be carried out in different cultures to develop a robust understanding on Machs and outcome variables. Other trait activators, such as organizational culture, engagement, perceived appraisal satisfaction, etc., simultaneously and as interaction, need to be studied. The study also provides evidence that all the three tools (MPS, Job Autonomy Scales, Counterproductive Work Behaviour) were having construct validity in the Indian context. This study, like others, also has its limitations. Although the data was collected from managers, they were different from each other in terms of years of experience and companies they worked for. Female representation is also reduced when compared to males’. All the questionnaires were self-report measures; however, they did not suffer from common method bias. Taking other perspectives (such as superiors or peers) would have added to the external validity of the study. References |

Cite this article as: Rehman, U. & Shahnawaz, M. G. (2018). Machiavellianism, job autonomy and counterproductive work behaviour among Indian managers. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 34, 83-88. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2018a10

Correspondence: usama.ktw@gmail.com (U. Rehman).

Copyright © 2024. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef