The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Adolescent Bullying: A Systematic Review

[El papel de la inteligencia emocional en el acoso escolar adolescente: una revisión sistemática]

Pilar Rueda, Nuria Pérez-Romero, M. Victoria Cerezo, and Pablo Fernández-Berrocal

Universidad de Málaga, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a29

Received 18 June 2020, Accepted 2 August 2021

Abstract

Bullying is a problem within the school context and with important consequences for the victim. The scientific literature has shown that emotional intelligence (EI) enhances the role of cohabitation within the school context. This systematic review aims to analyze the evidence of the role of EI in bullying. Results show greater levels of emotional perception in students involved in bullying and lower levels of emotional understanding and regulation compared to students not involved in these behaviors. In addition, gender differences in their levels of EI were found among students involved in bullying. The results reveal the importance of designing and implementing programs of EI in the school context as prevention and action against bullying.

Resumen

El acoso escolar o bullying tiene lugar en el contexto escolar y tiene importantes consecuencias para la víctima. La literatura ha mostrado ampliamente que la inteligencia emocional (IE) tiene un rol favorecedor de la convivencia en el contexto escolar. Por ello, el objetivo de esta revisión sistemática fue analizar la evidencia que existe sobre el papel de la IE en el acoso escolar. Los resultados señalan que hay un mayor nivel de percepción emocional en el alumnado implicado en el acoso (tanto agresor como víctima) y menor en comprensión y regulación en comparación con el alumnado que no está implicado en estas conductas. Además, se observaron diferencias en el grado de IE de los estudiantes implicados en acoso según el género. Los resultados indican la importancia que tiene diseñar e implementar programas de desarrollo de la IE en el contexto educativo como prevención y actuación en el acoso escolar.

Palabras clave

Adolescencia, Acoso escolar, Educación, Inteligencia emocional, Revisión sistemáticaKeywords

Adolescence, Bullying, Education, Emotional intelligence, Systematic reviewCite this article as: Rueda, P., Pérez-Romero, N., Victoria Cerezo, M., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2022). The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Adolescent Bullying: A Systematic Review. PsicologĂa Educativa, 28(1), 53 - 59. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a29

pilarrueda@uma.es Correspondence: pilarrueda@uma.es (P. Rueda)Adolescence is a transition period between childhood and adulthood, marked by the development of autonomy, personality, and identity. In this period, relationships with peers play an important role. Therefore, experts advise focusing on adolescence to reduce possible long-term risks (Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2020; Sánchez-Ventura & Grupo PrevInfad/PAPPS Infancia y Adolescencia, 2012). Many of these peer interactions take place within the school environment, where children and adolescents spend a large part of their time, in some cases longer than the time they spend with their families. Therefore, school is an environment deserving special attention, as it is in this environment where most bullying takes place, a problem that has recently become particularly virulent (Chu, 2019; Modecki et al., 2014; Unesco, 2019). Conflicts arising in the peer group are natural, even potentially positive (Narejo & Salazar, 2002). The key that will determine their magnitude lies in how the involved adolescents manage to resolve them, without actually bullying (Ruiz et al. 2016). The scientific literature has shown that adolescents’ emotional skills play a determining role in bullying (Estévez et al., 2019; Méndez et al., 2019). This systematic review aims to synthesize research conducted within the last twelve years focusing on the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and bullying in the adolescent population, as well as the possible knowledge gaps within this field. Bullying at School It is common for conflicts to occur during coexistence in the school environment, and these can become violent. However, when this violence is exercised repeatedly towards the same person we are dealing with bullying. Bullying is defined as a set of interpersonal aggressions in which an aggressor repeatedly and intentionally carries out behaviors that lead to an imbalance of power between him/her and the victim (Volk et al., 2014). Bullying can be physical, verbal, or psychological (e.g., isolating the victim). The group component (bystanders witnessing bullying situations) is of great importance in this dynamic (Nickerson, 2019; Ruiz et al., 2016). In recent years, parallel to the rise of the Internet and social networks, another form of violence has arisen, called cyberbullying, which includes the use of social networks and the Internet for bullying (Slonje & Smith, 2008). The focus of this review is on bullying, not cyberbullying, because, although both forms of bullying share some features (Baldry et al., 2016), they also have their own characteristics. Bullying can be carried out by a person or group of people who exercise power over others, acting as aggressors. In this sense, different roles that influence bullying are identified (Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010; Ruiz et al., 2016): the bully, the victim, the observers (people who witness the bullying but do not intervene), and the bully/victim, that is, those adolescents who suffer bullying and at the same time exert it against others (Ruiz et al., 2016). Bullying is a major problem due to the consequences it has on health, social relationships, and school performance, among many other consequences in the lives of the victims and the environment itself (Baldry et al., 2016; Chu, 2019; Nickerson, 2019). Bullying has also mid- and long-term effects on the lives of the victims, causing distrust towards others and problems with self-concept; and on the aggressors, who may present maladaptive behaviors and end up involved in criminal actions (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2019; Cerezo, 2008; Goodwin et al., 2019; Nickerson, 2019). Therefore, it is essential to understand the problem to address it and design strategies to help prevent bullying in schools, as well as to intervene in cases where it has already occurred (Goodwin et al., 2019; Méndez et al., 2019; Nickerson, 2019; Quintana-Orts et al., 2018). Emotional Intelligence Emotions generate brain and body changes, and this information can be used for an individual’s benefit, influencing their decision-making (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016; Mayer & Salovey, 1997). According to Damasio (1999), all emotions have a regulatory function and act as an advantage for the person experiencing them. There are two major theoretical approaches to EI: the mixed model and the ability model (Joseph & Newman, 2010; Mayer et al., 2008). The mixed model defines EI as a set of abilities and personality characteristics that allow a person to interact successfully with the environment as well as to maintain their well-being (e.g., Bar-On, 1997). These models primarily use self-report tests for the assessment of EI. On another hand, the ability model defines EI as an ability to identify one’s and others’ emotions, using them to direct one’s thoughts and behaviors (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). These authors’ process model conceptualizes EI based on four skills: perception of emotions, use of emotions to support thinking (called assimilation or facilitation), understanding of emotions, and finally regulation of emotions. These four skills are interdependent, occurring at both intrapersonal and interpersonal levels, and can be assessed using self-report and ability tests (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016; Mayer et al., 2016). Emotional perception refers to the ability to identify one’s own emotions as well as those of others. This is done by paying attention to the sensations and states of one’s body and interpreting facial and body signals and the tone of voice of others. The second skill, emotional assimilation or facilitation, relates to the ability to take emotions into account when making decisions, as emotional states will influence how we manage our problems and information processing. Thirdly, understanding of emotions involves the ability to know and break down the different emotions and feelings, as well as the knowledge of their causes and the transition from one emotional state to another. Finally, emotion regulation is the most complex skill and refers to the ability to reflect on feelings and thus be able to regulate both one’s own feelings and those of others, carrying out different strategies and seeking personal growth (Cabello et al., 2016). This review aims to explore what is currently known about the role of EI in bullying. Specifically, this paper pursues the following specific objectives:

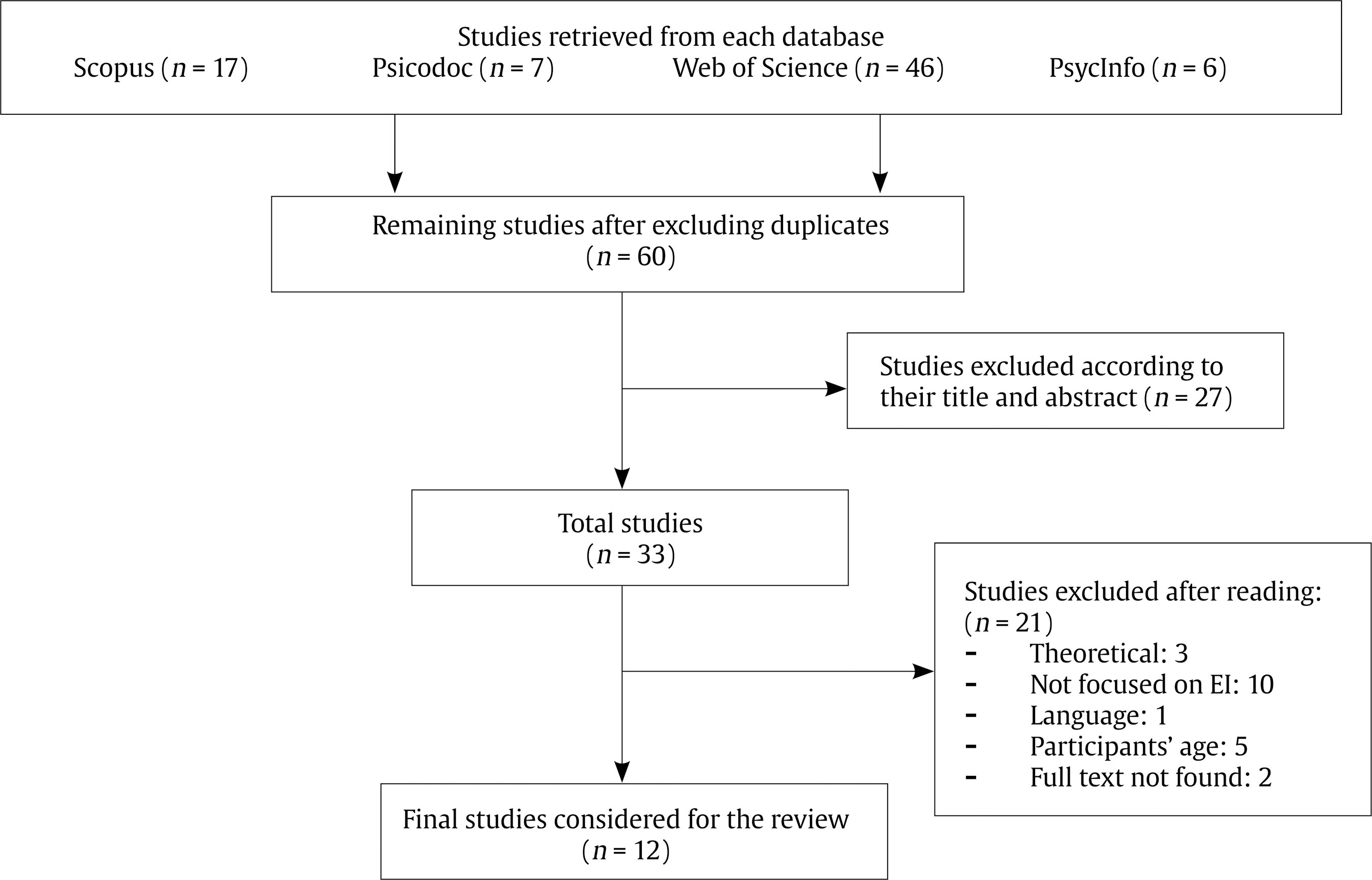

Answering these questions will ultimately allow us to better understand whether there is a relationship between EI skills and bullying. Bibliographic Search The databases used in this study were PsycInfo, Psicodoc, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search in each of them was carried out using the terms “Emotional Intelligence” and “Bullying” in the title and topic fields according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for this study were the age of the population, being limited to adolescents between 11 and 18 years old, the language of the articles, only collecting those in English and Spanish, studies focused on the mixed or ability model, and the year of publication of the articles, focused on the last twelve years (from January 1, 2008 to June 1, 2020). The exclusion criteria were studies carried out in population with adults and/or children, studies focused on population with mental disorders, studies only focused on cyberbullying or not distinguishing between cyberbullying and traditional bullying, studies not looking for relationships between EI and bullying, studies not distinguishing between adolescents involved and not involved in bullying or between victims and bullies, and purely theoretical studies (i.e., not performing any evaluation). Article extraction. The search in the databases yielded numerous articles in each of them: 17 in Scopus, 7 in Psicodoc, 46 in Web of Science, and 6 in PsycInfo, leading to a total of 74 articles. Of these, 16 were excluded as duplicates, 2 of the articles could not be accessed in full text, and 27 were discarded after reviewing the title and abstract, and refining according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, a full reading of the remaining articles was carried out to further refine the sample, eliminating a total of 19 articles. These articles were discarded for various reasons which are not within the scope of this review: not offering assessment, using age groups outside the established age criteria, assessing social intelligence only, or focusing specifically on other aspects such as, for example, cyberbullying or school safety according to gun ownership. After the last screening, the present review was carried out with a final number of 12 articles. This process is shown in Figure 1. Instruments Used in the Studies Retrieved EI assessment. The instruments used for the assessment of EI in the studies reviewed, all of which were self-report measures, are detailed below. The TMMS-24, the Bar-On Inventory, and the Adolescent SUEIT were used in eight of the twelve studies. Among the instruments were those corresponding to the ability model, such as the TMMS-24, the SUEIT or the EIS, and instruments corresponding to the mixed model, such as the Bar-On Inventory, the CTI, or the SEC. We decided to include studies using these instruments despite belonging to different models of EI because the scales contained in the mixed model measure characteristics comparable to the skills measured in the questionnaires belonging to the ability model: emotional coping, which can be understood as emotion regulation, and self-awareness, understood as intrapersonal emotional perception or emotion regulation. The instruments are described as follows:

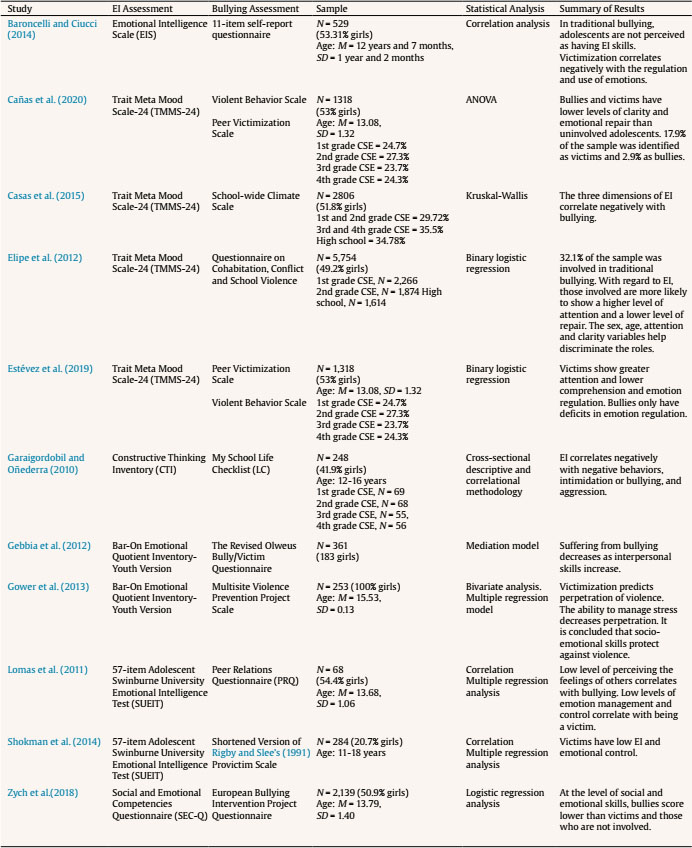

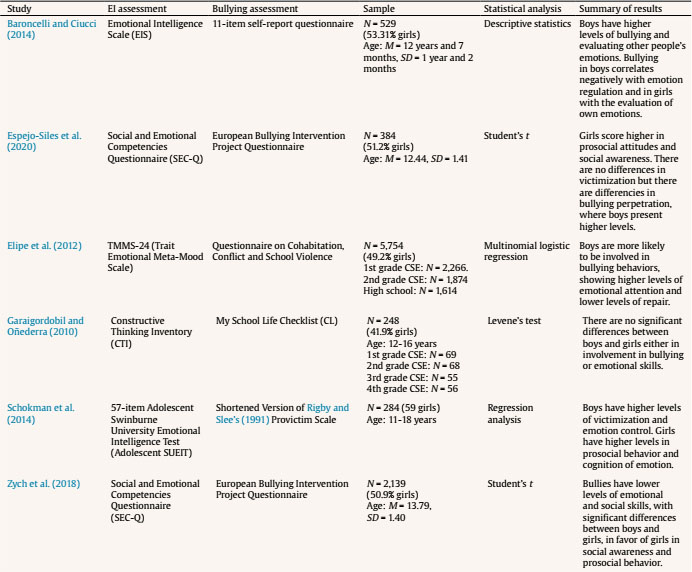

Bullying Assessment Each study reviewed used a different instrument to assess bullying. Despite this variability in the measures used, all of the instruments differentiate the roles of victim and aggressor. The results obtained from this review are organized in two blocks, according to the two objectives of this study: to determine whether there are differences in EI levels according to bullying roles (Table 1) and to analyze whether there are differences in EI dimensions according to gender in adolescents involved in bullying (Table 2). Table 1 Summary of Results Found when Relating IE to Bullying  Note. CSE = compulsory secondary education; EI = emotional intelligence. Levels of EI in Different Bullying Roles The studies analyzed indicated a clear negative association between EI and bullying. Lower levels of EI associated with bullying are found in all articles. However, different levels are observed depending on the EI component and the bullying role in question. In other words, differences are found depending on whether the adolescent is the bully or the victim, with each of them having higher or lower levels of certain EI components. In four of the articles (Cañas et al., 2020; Casas et al., 2015; Elipe et al., 2012; Estévez et al., 2019) EI was measured with the TMMS-24 (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004; Salovey et al., 1995). These studies have shown that the levels of each component of EI help to discriminate between uninvolved and involved adolescents and, within the latter, between victim and bully. The results show high levels of attention and lower levels of clarity and repair both in victims and bullies (Cañas et al., 2020; Casas et al., 2015; Elipe et al., 2012). Estévez et al. (2019) showed that the emotional profile of victims is characterized by high levels of attention and low levels of clarity and repair, which worsens victimization. On another hand, bullies only show deficits in the ability to repair emotions (emotion regulation). These results are consistent with data from other research. One work, by Baroncelli and Ciucci (2014) used the EIS (Schutte et al., 1998) to assess EI. Their results show lower levels of appraisal of one’s emotions as the level of bullying increases (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014). On another hand, two of the studies (Lomas et al., 2011; Schokman et al., 2014) assessed EI with the 57-item SUEIT. These studies found that bullies have a low ability to recognize others’ emotions whereas victims have low levels of emotion management (Lomas et al., 2011). Schokman et al. (2014) reported low levels of emotional management in victims. In three of the studies reviewed, we found that victims of bullying have lower levels of emotional control and use of emotions (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014; Lomas et al., 2011; Schokman, et al., 2014). Emotional control and use are understood as the ability to regulate and modify emotions according to the circumstances in which the person finds themselves, for example, to overcome obstacles in everyday life. Levels of understanding of others’ feelings were also found to be significantly lower in those who engage in bullying behavior (Lomas et al., 2011). The study by Garaigordobil and Oñederra (2010), unlike the previous ones, was focused on Epstein’s (2001) model and used the Constructive Thinking Inventory (CTI). This study showed that those adolescents who showed higher levels of GCT received higher levels of positive behaviors and lower levels of negative behaviors from their peers, presenting a lower rate of bullying and a lower rate of aggression, and vice versa. Similar results were also found in the study by Gebbia et al. (2012), in which EI is measured with the two Bar-On scales, finding lower scores in bullies. Two of the studies reviewed suggest that multiple roles can be performed. On the one hand, the study by Gower et al. (2013) found that girls who had been bullied were more likely to carry out violence against others, that is, victims can become aggressors, referring to the bully-victim or aggressor/victim role. On another hand, the results of Baroncelli and Ciucci (2014), in line with other studies (Baldry et al., 2016), showed that adolescents can be involved both in traditional bullying and cyberbullying, thus performing multiple roles. Differences in EI according to Gender among Students Involved in Bullying Five of the twelve studies found a clear difference between boys and girls, whereas one of the studies found no differences (Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010). It should be noted that, in this study, although the instrument used assesses emotional competences, mainly emotion regulation, it is primarily a thinking inventory. Four of the studies reported higher levels of prosocial attitudes in girls (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014; Espejo-Siles et al., 2020; Schokman et al., 2014; Zych et al., 2017), conceiving prosocial attitude as the understanding of emotions and tendency to help others and have good relationships. Girls also showed greater cognition of emotion and greater ability to evaluate emotions. The results of three studies show differences in boys’ emotion regulation, although contradictory, with two of the articles showing higher levels (Schokman et al., 2014; Zych et al., 2017), whereas another obtained the opposite (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014). This systematic review focused on the relationship between EI and bullying in the adolescent population. The aim was to analyze whether there are differences in EI levels according to the different roles in bullying (aggressor and victim). We also tested whether there are differences between the emotional skills of boys and girls involved in bullying. We can conclude that EI is indeed associated with less bullying because adolescents with higher EI scores were also those who were less involved in bullying, either as aggressor or victim. Although bullying is a complex and multi-causal phenomenon, we can state that having adequate emotional skills has a positive impact on a student’s non-involvement in this problem. Regarding the different roles, it was found in all the studies that the level of EI is lower in those adolescents involved in bullying, whether they are victims of bullying or aggressors. In contrast, higher levels of EI are found in those adolescents who are not involved in bullying. The results can be disentangled according to the components of the model of EI by Mayer and Salovey (1997). The decision to use this model as a framework responds to the fact that all the instruments used in the studies measure skills parallel to those proposed in this model: emotional perception, assimilation, understanding, and regulation. Thus, for example, the CTI comprises a dimension that can be considered emotion regulation, the SEC measures self-perception and regulation, and the Bar-On EQ comprises subscales of emotion regulation. The results show different levels in each of the EI components, with adequate levels of emotion perception, but lower levels of emotion understanding, and regulation. This means that adolescents involved in bullying do not have great difficulties in perceiving and expressing emotions, but they do have deficiencies in understanding and regulating them (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014; Cañas et al., 2020; Casas et al., 2015 ). In particular, both bullies and victims seem to lack adequate emotional management or regulation skills. A possible and interesting explanation for the results found may be related to the ability of bullies to attend to and perceive emotions; this would make them able to identify victims (those peers they consider vulnerable) and to gain a dominant role in the class group. Regarding deficits in regulation, we observed a tendency towards aggressiveness as a way of regulating diverse emotions such as anger, frustration, or sadness (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2019; Ruiz et al., 2016). Likewise, this dominance over others could be alleviating a deficit in self-esteem or attention (Carrera-Fernández et al., 2019). On another hand, victims’ difficulties to regulate their emotions could be due to the use of maladaptive strategies. This could worsen the phenomenon of bullying and victimization, which is aggravated by a high perception of one’s emotions, and which has been related to anxiety and increased risk of depression (Cañas et al., 2020; Elipe et al., 2012; Estévez et al., 2019; Salguero & Iruarrizaga, 2006). Considering gender, we observed discrepancies in the levels of EI shown by boys and girls (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014; Espejo-Siles et al., 2020; Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010; Schokman et al., 2014; Zych et al., 2017). It seems that girls have higher levels of prosocial attitudes and emotional perception. Boys, on the other hand, in addition to being more involved in bullying, seem to show higher levels of emotional control, although not all studies show unanimous results in this regard. A possible explanation for these differences in emotional skills between boys and girls could be based on the education received by each gender and the different socialization processes since childhood (Espejo-Siles et al., 2020; Zych, et al., 2017). In the light of these results, we can reach different conclusions. On the one hand, the importance of EI in the understanding of bullying, as studies have shown that involved adolescents present lower levels in different dimensions of EI compared to adolescents not involved in bullying (Cañas et al., 2020; Elipe et al., 2012; Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010; Gower et al., 2013). Along the same lines, the assessment of EI levels can contribute to preventing bullying in adolescence and, therefore, to improving intervention programs, also acting as a protective and preventive factor (Lomas et al., 2011; Nickerson, 2019). This would be the right path to follow in the development of the school curriculum (Garaigordobil & Oñederra, 2010; Lomas et al., 2011; Zych et al., 2017). Thus, the results suggest the importance of addressing students’ emotional competences to reduce the level of bullying and promote adequate personal development, taking into account the existing differences between boys and girls in their emotional skills (Cabello et al., 2016; Schokman et al., 2014). One of the limitations of this study is that the results regarding gender differences in EI levels are not conclusive, as not all studies analyzed this issue and, among those that did, there are discrepancies. This gap points to the need for further research on this topic, not only to find out whether these differences exist but also for the design and implementation of EI education programs. It would also be interesting to know if the effect of the gender x role interaction clarifies the different dynamics of bullying and victimization between boys and girls. Another limitation to drawing strong conclusions may be the variety of questionnaires used to assess both EI and bullying in each of the studies, which makes it difficult to obtain comparable results. In addition, all questionnaires used to measure EI are self-report measures, which always entails limitations as they are based only on self-perceptions (Mayer et al., 2016). Future lines of research should conduct studies that overcome these limitations, helping to clarify, for example, how boys and girls are different in their emotional skills and their involvement in bullying. Emphasis should also be placed on the homogenization of questionnaires and measurements both of EI and bullying to facilitate discussion of the results. Another important line of research to be developed in the future is to look more deeply into the influence of EI in each of the roles, as studies tend to focus on the bully and the bullied, but only some of them mention the bully-victim role. Also, most do not take into account the observers of bullying, even though they are very important for assessing the dynamics of bullying. In conclusion, higher levels of EI are found in adolescents not involved in bullying and lower levels of EI are found in adolescents involved in this behavior. This review, by analyzing the different roles, has shown that the promotion of EI to address this problem must be understood in a multi-focal way, with the ability to regulate emotions being an aspect to work on both bullies and victims. Likewise, gender differences in emotional skills must be taken into account. To know and understand the role of EI in bullying, differentiating both by roles and gender, is of great relevance to act more effectively in its prevention and treatment and aiming at promoting students’ well-being and a safe and healthy school environment. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Rueda, P., Pérez-Romero, N., Cerezo, M. V., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2021). The role of emotional intelligence in adolescent bullying: A systematic review. Psicología Educativa, 28(1),53-59. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a29 Funding: This research was partially funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (Project: PSI2017-84170-R) and the Junta de Andalucía (Project: UMA18-FEDERJA-114) to Pablo Fernández Berrocal. References |

Cite this article as: Rueda, P., Pérez-Romero, N., Victoria Cerezo, M., and Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2022). The Role of Emotional Intelligence in Adolescent Bullying: A Systematic Review. PsicologĂa Educativa, 28(1), 53 - 59. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2021a29

pilarrueda@uma.es Correspondence: pilarrueda@uma.es (P. Rueda)Copyright © 2024. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS