A Comparative Study between Recidivism Offenders and Non-recidivism Offenders in a Prison Sample

[Estudio comparativo entre delincuentes reincidentes y no reincidentes de una muestra en prisi├│n]

Verónica Molina-Coloma1, Karmele Salaberría2, and José I. Pérez2

1Universidad Aut├│noma de Coahuila, M├ęxico; 2Universidad del Pa├şs Vasco, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a19

Received 3 September 2020, Accepted 25 March 2021

Abstract

Research on penitentiary recidivism is an essential topic for the prevention of crime because, at the time of release, inmates with a high risk of committing crimes do not usually have the necessary tools to cope with the challenges of community life. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to identify criminal personality and psychopathological characteristics related to recidivism. The sample made up of 89 (n = 49 non-recidivists, n = 40 recidivists) inmates in a prison in Ecuador. The results showed that recidivist inmates, unlike non-recidivist inmates, present antisocial, borderline, and aggressive-sadistic personality, higher alcohol and drug dependence, and higher levels of physical aggression. From a criminal viewpoint, recidivist inmates commit more crimes against property; a larger proportion presented a history of juvenile delinquency and more disciplinary records in adult prison. Consequently, the results indicate the need to design and implement specific interventions to reduce recidivism in these offenders.

Resumen

La investigación acerca de la reincidencia penitenciaria es un tema fundamental para la prevención del delito, pues los internos al momento de la liberación, particularmente aquellos con alto riesgo de cometer delitos, no suelen contar con las herramientas necesarias para hacer frente a los desafíos de la vida comunitaria. Por tanto, el objetivo principal de este estudio ha sido identificar la personalidad delictiva y las características psicopatológicas relacionadas con la reincidencia penitenciaria. La muestra estuvo conformada por 89 (n = 49 no reincidentes, n = 40 reincidentes) internos de un centro penitenciario de Ecuador. Los resultados mostraron que los reincidentes, a diferencia de los no reincidentes, presentan personalidad antisocial, límite y agresiva-sádica, mayor dependencia al alcohol y drogas y un mayor nivel de agresión física. Desde el punto de vista penal los reincidentes cometen más delitos contra la propiedad; una proporción mayor presentaba antecedentes de delincuencia juvenil y más antecedentes disciplinarios en la prisión de adultos. En consecuencia, los resultados indican la necesidad de diseñar e implementar intervenciones específicas para reducir la reincidencia en estos infractores.

Palabras clave

Reincidencia, Personalidad, Psicopatolog├şa, Prisi├│n, Estudio de casos controlKeywords

Recidivism, Personality, Psychopathology, Prison, Case-control studyCite this article as: Molina-Coloma, V., Salaberría, K., and Pérez, J. I. (2022). A Comparative Study between Recidivism Offenders and Non-recidivism Offenders in a Prison Sample. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 32(1), 33 - 39. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a19

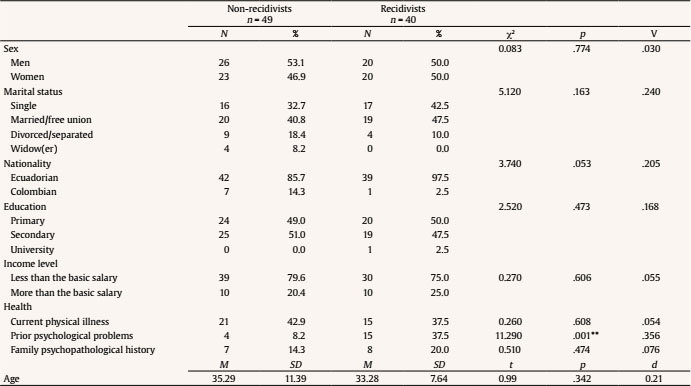

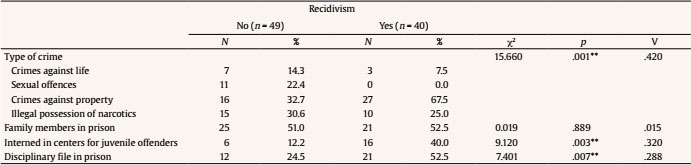

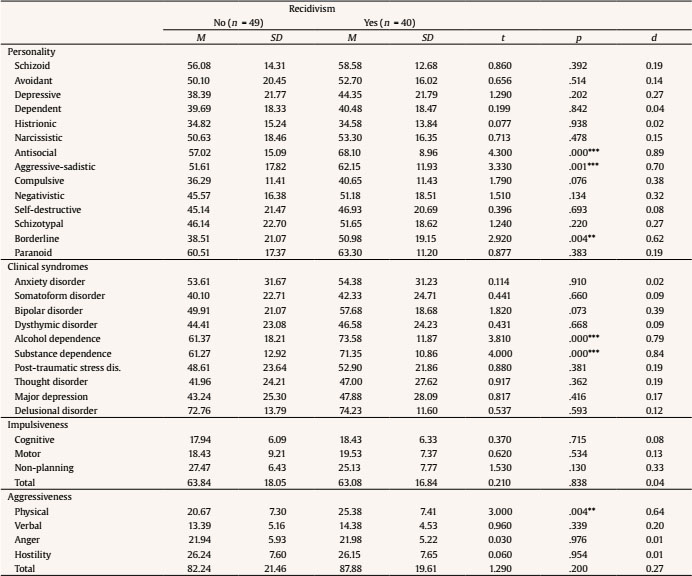

veronicamolinacoloma@gmail.com Correspondencia: veronicamolinacoloma@gmail.com (V. Molina-Coloma).The present study focuses on penitentiary recidivism, defined as reentry into prison due to a new criminal offence committed by the same person (Nguyen et al., 2011). Capdevila and Ferrer (2009) distinguish two types of penitentiary recidivism: on the one hand, general recidivism, which is the commission of any new offense and, on the other hand, violent recidivism, which is the commission of a violent act that implies threat, harm, aggressions, or injuries to another person. Among the types of crimes most commonly associated with penitentiary recidivism are offences against property (Capdevila & Ferrer, 2009; Zabala-Baños, 2015) followed by crimes of drug trafficking (Hakansson & Berglund, 2012), and, to a lesser extent, violent crimes (Nguyen et al., 2011). Most of recidivism events are non-violent (property crimes, violation of post-release conditions, etc.), though released prisoners also have an elevated risk of violent recidivism that has much more impact on a psychological and physical level (Heeks et al., 2018). The study of prison recidivism is considered a way of evaluating the effectiveness of the penitentiary system; in that sense, prison recidivism rates are a reflection of security policies, effectiveness of police control, and the results of applying a certain legislation, or the application of social and health policies. In Ecuador, the current Constitution, the Organic Penal Code, and the National Plan for Good Living point out that the rehabilitation system established in the country is aimed at social reintegration (Molina-Coloma, 2019). While is true that Ecuador is considered one of the South American countries with the lowest rates of people incarcerated, in October 2013 there were 24,2037 inmates in the whole country, but in September 2014 this figure increased to 26,821 people hospitalized and in 2017 there were 36,661 inmates. However, in practice there is no real rehabilitation. Many people who leave reoffend for the same crimes or for other modalities and the prison; population has grown (Campaña-Muñoz et al., 2019). Criminal acts and recidivism can have their origin in individual, social, and environmental factors (Redondo, 2015). In this regard, some studies have shown contextual factors, such as economic disadvantage, racial segregation, and proximity to other recidivists, can all influence individual recidivism (Clark, 2016; Mears et al., 2008; Stahler et al., 2013). In this study, we are going to try to establish a recidivist profile considering sociodemographic and criminal characteristics but with special emphasis on personality and psychopathology (Krueger et al., 1994), particularly in the externalizing spectrum (Krueger et al., 2007). Savage (2009) suggests criminal recidivism represents a stable behavioral pattern in the sense of assuming that personal dispositions could be one of the determinants of that kind of behavior. Also, personality traits that are related to criminal recidivism have been found to be those that were already proven as being related to criminal behavior in general. Several studies point out those recidivist offenders to be characterized by antisocial tendencies and the development of criminal behavior at an early age. Likewise, studies suggest that neuropsychological problems related to learning difficulties, reasoning problems, and children’s and adolescents’ academic failure, along with the interaction with criminogenic environments throughout their development, may end up in a pathological personality and as a result, leading to persistent or recurrent criminal behavior (Međedovi et al., 2012; Moffitt, 1993; Savage et al., 2013). In the study of delinquency, temperament is an important figure for the study of the externalizing spectrum of psychopathology, which is associated with attentional focus, inhibitory control, and effort. In this sense, early facets of temperament, such as activity, level, negative affectivity, and low inhibitory control can prospectively predict the development of externalizing behavior, especially in high-risk environments (Beauchaine & McNulty, 2013; Stringaris et al., 2010). Therefore, the presence of neurobiological vulnerabilities in conjunction with the interaction of high-risk environments increases the probability of participating in criminal behaviors (Meier et al., 2008). It has been found that some adult offenders can follow a developmental path that begins in preschool, many with severe ADHD problems, close relationships with fellow offenders, substance abuse and dependence, ASPD, incarceration, and ends up with recidivism (Beauchaine et al., 2010). Along these lines, studies in prison population point out that antisocial and borderline personalities are more associated with recidivism (Chang et al., 2015; Krueger et al., 1994; Krueger et al., 2007). Another compared study with recidivists and non-recidivists evaluated through the MCMI-III inventory found that sadistic-aggressive, antisocial, paranoid, and borderline personality types predominated among criminal recidivists (Kiwi & Sadeghi, 2015). In the same vein, others studies found impulsive characteristics, aggressive behavior (Dargis & Koenigs; Hiscoke et al., 2003), and substance abuse (Walter et al., 2011) are important risk factors for criminal recidivism in adults (Gendreau et al., 1996). These studies in the prison context point out the aforementioned about the association of crime and particularly recidivism with the externalizing spectrum of psychopathology. Thus, these characteristics could be considered for prison treatment around reduction of recidivism. This study is important since empirical findings demonstrate that people who often engage in criminal activity cause more damage to society than those who do it only once (Međedovi et al., 2012). As such, evaluation of risk of recidivism is a priority because recidivist offenders will need intensive interventions (Bonta & Andrews, 2016). In a Latin American context, one in three offender recidivists, most of them enter prison because of more serious crimes than when they were put in jail for the first time (La Pizarra, 2020). In this sense, in these contexts and in the case of Ecuador, prison treatment aimed at reducing recidivism in prison is still an issue that is little addressed (Campaña-Muñoz et al., 2019). In this regard, the objective of this study is to stablish sociodemographic, criminal, personality, and psychopathological characteristics in recidivist, incarcerated men and women. Participants This is a case-control study with a non-probability convenience sample composed by 89 inmates in the prison of Ambato (Ecuador). The inclusion criteria for the study were: a) being able to read and write, b) giving informed consent, c) not being on remand, and d) presenting valid profiles in the MCMI-III (based on validity or sincerity indices). Of them, 49 are nonrecidivists, that is, they are in prison for the first time, and 40 are recidivists for committing another crime. Among the latter, 22 are recidivists for the first time, 11 for the second time, and 7 for the third time. Among non-recidivists, 26 are men and 23 are women, with a mean age of 35.58 years (SD = 11.39) and among recidivists, 20 inmates are men and 20 are women with a mean age of 33.27 years (SD = 7.64), without significant differences in these variables. Prisoners interned for the first time had a sentence of 96.14 months (SD = 77.81) and recidivists of 44.67 months (SD = 56.69, t = 3.49, p < .001, d = 0.75). Non-recidivist offenders had been in prison for 39.69 months (SD = 32.16) and recidivists for 15.45 months (SD = 22.04, t = 4.05, p < .000, d = 0.88). Differences in these variables were significant. Instruments Questionnaire of sociodemographic characteristics. This study’s first author designed the ad hoc questionnaire and collected sociodemographic data, which were contrasted with prison records. Questionnaire of crime characteristics. Study’s first author designed the ad hoc questionnaire to gather data about the criminal history, which were then corroborated with data from records of each prison inmate. Millon Multiaxial Clinical Inventory-III (MCMI-III; Millon et al., 1997). This inventory evaluates 14 clinical personality (schizoid, avoidant, depressive, dependent, histrionic, narcissistic, antisocial, aggressive-sadistic, compulsive, negativistic, self-destructive, schizotypal, paranoid, and borderline) patterns and 10 clinical syndromes (anxiety disorder, somatoform disorder, bipolar disorder, dysthymic disorder, alcohol and substance dependence, post-traumatic stress disorder, thought disorder, major depression, and delusional disorder). MCMI-III consists of 175 items, which are rated as true or false. We employed the Spanish adaptation of Cardenal and Sánchez (2007), which has a Cronbach alpha between .96 and .82. In previous studies in Ecuadorian prison population, Cronbach alpha was .92 (Molina-Coloma, Salaberría, et al., 2018). The questionnaire has four control indices: a validity scale (consisting of three items; if two or more of the items are endorsed it invalidates the profile) and Disclosure, Desirability, and Debasement scales (Cardenal & Sánchez, 2007). Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11). We used Oquendo et al.’s (2001) Spanish adaptation. This scale consists of 30 questions, grouped into three subscales: cognitive impulsiveness, motor impulsiveness, and unplanned impulsiveness and a total impulsiveness score. The respondent rates the items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (seldom or never) to 4 (always or almost always). This instrument does not have control scales, although items 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 13, 17, 19, 22, and 30 are inversely worded and allow controlling for response acquiescence. Internal consistency (Cronbach alpha) of the Spanish adaptation was .80 and Ecuadorian adaptation internal consistency was .83 (Molina-Coloma, Salaberría et al., 2018). Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ). This scale’s Spanish adaptation (Andreu et al., 2002) was used, consisting of 4 subscales: physical aggression, verbal aggression, anger, and hostility. The sum of the 4 subscales makes up the total score. The scale has 12 items that are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely untrue for me) to 5 (completely true for me). It does not have control scales but items 15 and 24 are inversely worded and allow controlling random responses. The scale presents a Cronbach alpha of .88. The physical aggression subscale is the most precise, with an internal consistency of .86, the anger subscale has an internal consistency of .77, verbal aggression .68, and hostility, .72 (Andreu et al., 2002). In the Ecuadorian context, Cronbach alpha was .82 (Molina-Coloma, Salaberría et al., 2018). Procedure To perform this research, we first obtained permission to access the penitentiary. Prisoners in this penitentiary were convicted of violent and non-violent crimes. They are assigned to three pavilions organized according to the degree of danger. Subsequently, prison’s inmates received a letter informing them about the study and requesting their voluntary participation. The first author of the study carried out the questionnaires and the interview, and people who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form. The evaluation process was carried out individually in the office of evaluation and psychological diagnosis of the prison took place in Ambato-Ecuador. Finally, a report of outcomes was offered to all participants who so requested, and a final report was provided to the institution. Data Analysis Information was analyzed using the statistical package SPSS (version 22.0). Descriptive analysis (means and standard deviations). Convicted recidivists and non-recidivists were compared using chi-square and Student’s t-test. From a sociodemographic viewpoint, as shown in Table 1, there were no differences between recidivist and non-recidivist inmates in nationality, educational level, marital status, number of children, income level, housing type, kind of work prior to incarceration, and occupation in prison. However, there were differences in the presence of psychological problems prior to imprisonment, χ2(1) = 11.28, p <.001, V = .35. In this sense, 15 out of 40 recidivists (37.5%) had prior psychological problems versus 4 out of 49 non-recidivists (8.16%). From a criminal viewpoint, 48% the sample had committed offences against property, and 28% illegal possession of narcotics. To a lesser extent, they presented sexual offences (12%) and offences against persons (11%). As seen in Table 2, recidivists committed more crimes against property, had a longer criminal history because they had more frequently been interned in centers for juvenile offenders, and presented more disciplinary problems in prison. Table 3 also shows the comparison between recidivists and non-recidivists in clinical personality patterns and clinical syndromes assessed with the MCMI-III. As shown, recidivists presented more antisocial (d = 0.89), aggressive-sadistic (d = 0.70), and borderline (d = 0.62) personality traits, as well as more substance (d = 0.84) and alcohol dependence (d = 0.79). Accordingly, externalizing psychopathology characterizes recidivism offenders as has been found in other studies (Chang et al., 2015; Krueger et al., 1994; Krueger, et al., 2007). Regarding the Aggression Scale, there were statistically significant differences in the physical aggression subscale, where recidivists had a mean score of 25.37 (SD = 7.40) versus non-recidivists, who had a mean score of 20.67 (SD = 7.30), t = 3.00, p < .004, d = 0.64. In other words, recidivist offenders are characterized by being more physical aggression, that is, they get involved in fights and they attack others. This research on the differential aspects between recidivist and non-recidivist inmates took into account the types of personality and clinical syndromes, and some criminal variables present in the inmates. From a criminal viewpoint, it shows that recidivist inmates have committed mainly crimes against property, as revealed in most previous research (Redondo, 2017). In these cases, penalties are lower than other types of offences, such as violent crimes and, consequently, inmates have spent less time in prison than non-recidivists. Recidivist inmates present a long criminal career and have committed offences in adolescence. Along these lines, early initiation in a criminal career indicates the need to address therapeutically and at an early age adolescents who begin to commit crimes (Thornberry et al., 2013). It is important to emphasize the presence of family members in prison, which, along with a violent context, is associated with criminal behavior; that is, it increases the probability that a family member will be delinquent (Farrington et al., 2001). Recidivist inmates in this study also presented a history of more disciplinary breaches in prison and higher scores on physical aggression. Thus, as seen in other studies, inmates with inadequate behavior in prison are more likely to relapse, especially those who are punished for violent behavior in prison (Cochran et al., 2012). In this study, it was expected that impulsivity would be present in recidivism inmates, but it was not. This result can be understood as, on the one hand, impulsiveness has generally been found in many offenders, whether recidivist or non- recidivist offenders (Griffin et al., 2018). On the other hand, it could be explained because impulsivity occurs in a wide range of internalizing and externalizing psychiatric disorders (Berg et al., 2015). In relation to aggressiveness, physical aggression was the only dimension of personality associated with recidivist offenders. In this regard, it can be noted that what distinguishes recidivist from non-recidivist offenders is the use of physical violence. However, the study of premeditated aggression was considered appropriate in the future, since previous studies have indicated this aggression type is associated with recidivism (Swogger et al., 2014). From a personality and psychopathology viewpoint, antisocial, aggressive-sadistic, and borderline personality, and addictive disorders, such as alcohol and drug dependence, were largely the ones that were associated with recidivism in this study and in previous research (Comín et al., 2016; Kiwi & Sadeghi, 2015). The relationship between delinquent behavior and substance use is bi-directional, particularly in socially and economically depressed environments (Redondo, 2015). For this reason, it could be considered that untreated addictive disorders lead people to commit new criminal acts to finance their addiction, which involves a risk factor for recidivism. The literature demonstrates we must assess the risk and protective factors to know how to intervene with those who are serving prison sentences (Sousa et al., 2019). Insofar as we can identify those prisoners, who are at increased risk for recidivism, this can maximize the effectiveness of the treatments carried out in prisons at rehabilitation, social reintegration and as a crime prevention strategy. Likewise, with the results found in this study, from a clinical perspective, intervention treatments could be established. Interventions have proved highly effective in prison contexts; for the treatment of psychopathology, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has proved the most effective (Folk et al., 2016), particularly for ASDP (Kramer, 2016). However, although further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of CBT in reducing recidivism, it may show promise for the treatment of recidivism (Folk et al., 2016). In addition, we also deem it relevant for future research to assess recidivism by type of offence, because each type of offender presents different therapeutic needs (Loinaz & Echeburua, 2010; Muñoz-Vicente & Lopez-Osorio, 2016). Thus, treatments tailored to specific risk factors would reduce recidivism more than generic treatments (Loinaz et al., 2011). This study presents some limitations, such as the small sample size, which prevents differential analysis depending on the number of re-imprisonments or the violent criminal typology presented by recidivists. Therefore, we wonder if the risk of recidivism and associated factors are the same for crimes against property or for sex crimes and crimes against persons, or whether they are specific in each case (Herrero, 2013). Another limitation is that there was no assessment of the risk of recidivism (Medina & Baños, 2016). This study has focused on the analysis of some of the individual risk factors, a few sociodemographic and criminological characteristics, but it would be of interest to determine protective factors, that is, factors that inhibit the recidivism of criminal and violent behavior (Redondo, 2015). This study has implications for both public policy and establishment of interventions. On the one hand, in terms of public policies, this research contributes to the strengthening of one of the main specific objectives of the National Plan for Good Living. This objective attends exclusively to juvenile and adult felons’ right to social rehabilitation (Consejo Nacional de Planificación [CNP, 2016]). In this sense, this study contributes to the psychosocial area. On the other hand, in order to establish effective intervention programs, it is important to consider the principles of Risk-Need-Responsiveness in the design and application, since they have multiple therapeutic objectives, a solid theoretical and empirical foundation, the integrated application of the entire program, the provision of standardized manuals for their application, and therapists’ skills and training (Redondo, 2017). In this regard, in terms of intervention proposals associated with the results obtained in this paper and considering that in the context of Ecuador there are no evidence-based programs (Ministerio de Justicia, Derechos Humanos y Cultos, 2017; Molina-Coloma et al., 2021; Molina-Coloma, Pérez, et al., 2018), at first, intervention programs already established in other prison contexts could be taken as a basis, such as those carried out in the United Kingdom, which are accredited programs (Correctional Services Accreditation and Advice Panel [CSAAP, 2021]). Subsequently, it must be assessed whether the replication of programs in the Ecuadorian context has been effective or, at the same time, developing own programs considering the benefits and limitations of the application of replicated programs. For the intervention in drug and alcohol addictions, Building Skills for Recovery (BSR) or the Alcohol Dependence Treatment Program (ADTP) could be considered as the basis. For treating personality disorders found in this study, the Mentalization-based Treatment (MBT) can be considered for example. Finally, regarding the intervention to reduce recidivism, the Thinking Skills Program (TSP) could be useful (CSAAP, 2021). In conclusion, despite limitations, this research is particularly relevant in the Ecuadorian context, because it allows identifying factors that promote recidivism and thus is able to establish intervention programs to prevent recidivism and guarantee effective social rehabilitation (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2018). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest Acknowledgement We appreciate the interinstitutional agreement between the Ministry of Justice, Human Rights and Cults with the Technical University of Ambato, Ecuador, which allowed the entry into prison in Ecuador. Cite this article as: Molina-Coloma, V., Salaberria, K., & Pérez, J. I. (2021). A comparative study between recidivism offenders and non-recidivism offenders in a prison sample. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 32, 33-39. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a19 Referencias |

Cite this article as: Molina-Coloma, V., Salaberría, K., and Pérez, J. I. (2022). A Comparative Study between Recidivism Offenders and Non-recidivism Offenders in a Prison Sample. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 32(1), 33 - 39. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a19

veronicamolinacoloma@gmail.com Correspondencia: veronicamolinacoloma@gmail.com (V. Molina-Coloma).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS