Cyber Dating Abuse: Conceptualization and Meta-analysis of Prevalence Rates

[El ciberabuso de pareja: conceptualización y metaanálisis de las tasas de prevalencia]

Ainize Martínez-Soto and Izaskun Ibabe

Universidad del País Vasco UPV/EHU, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a11

Received 10 August 2022, Accepted 14 February 2023

Abstract

In this study, a systematic review was carried out with the aim of analyzing the terms, definitions, dimensions, and prevalence rates of cyber dating abuse (CDA). After the analysis, the term cyber dating abuse is considered as the most appropriate and a complete definition of the construct is provided, along with the related dimensions. In order to synthesize the victimization prevalence rates of CDA, a meta-analysis of 16 studies was also carried out, including 14,235 participants, based on most suitable and most commonly used instrument for CDA measurement. This meta-analysis indicated an estimated global prevalence of CDA victimization of 47%, the prevalence for the control dimension being 63%, while for direct psychological aggression it was 24%. The results hardly showed differences between male and female victimization, which would support gender symmetry. Despite some limitations, this bibliographic and meta-analytic review sheds light on the field of CDA.

Resumen

En este estudio se realiza una revisión sistemática con el objetivo de analizar los términos, definiciones y dimensiones utilizados, así como las tasas de prevalencia del ciberabuso de pareja. Tras el análisis, el término ciberabuso de pareja (CP) se considera el más adecuado. Se proporciona además una definición completa del constructo junto con las dimensiones relacionadas. Con el fin de sintetizar las tasas de prevalencia de la victimización de CP, se realiza un metaanálisis de 16 estudios, que incluyen 14,235 participantes, basado en el instrumento más adecuado y utilizado. El metaanálisis indica una prevalencia global estimada de victimización por CP del 47%, 63% para la dimensión control y para la de agresión psicológica directa un 24%. Además, los resultados apenas mostraron diferencias entre la victimización de chicos y chicas, lo que avalaría la simetría de género. A pesar de algunas limitaciones, la revisión bibliográfica y metaanalítica arroja luz sobre el campo del CP.

Palabras clave

Ciberabuso de pareja, Ciberviolencia de pareja, Jóvenes, Conceptualización, Metaanálisis

Keywords

Cyber dating abuse, Cyber dating violence, Youth, Conceptualization, Meta-analysis

Cite this article as: Martínez-Soto, A. & Ibabe, I. (2024). Cyber Dating Abuse: Conceptualization and Meta-analysis of Prevalence Rates. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 133 - 144. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a11

Correspondence: amartinez275@ikasle.ehu.eus (A. Martínez-Soto)

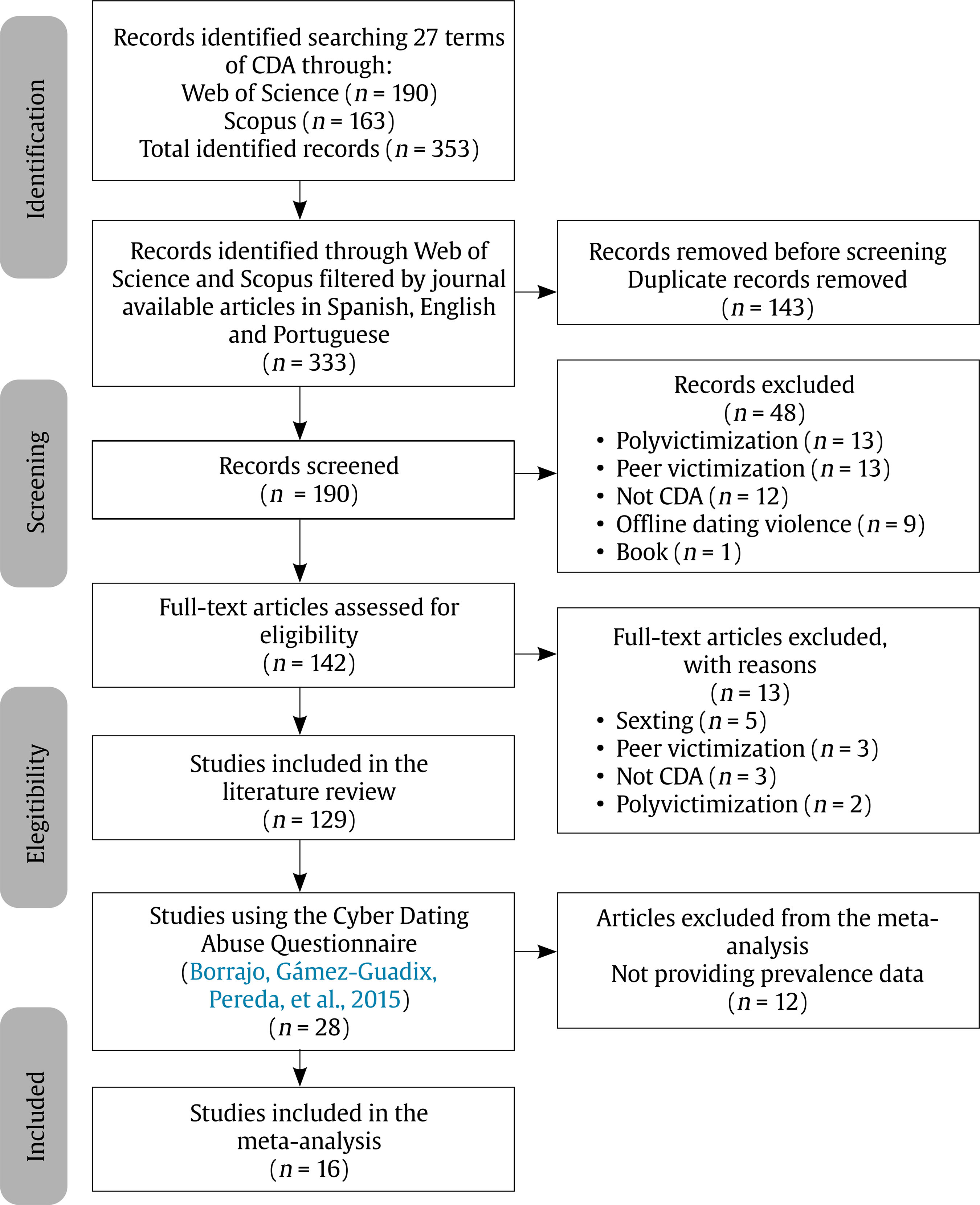

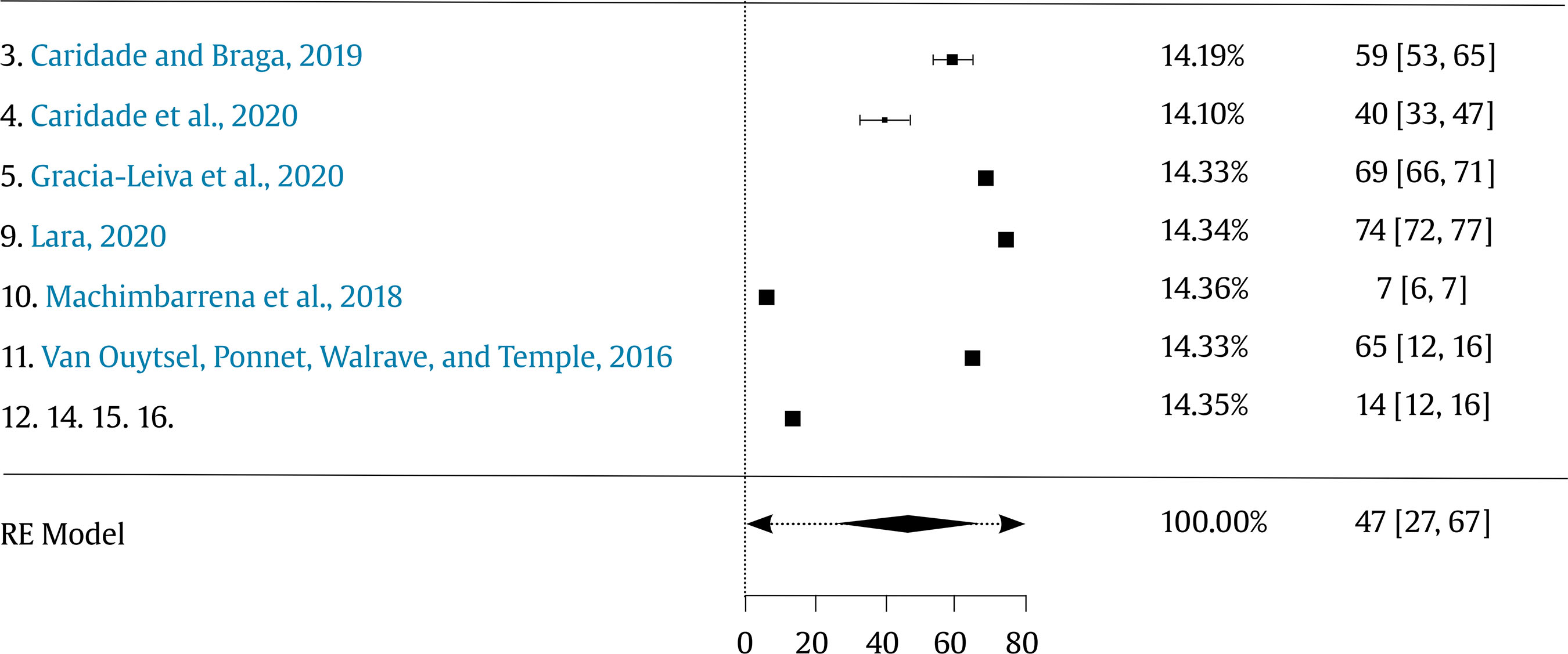

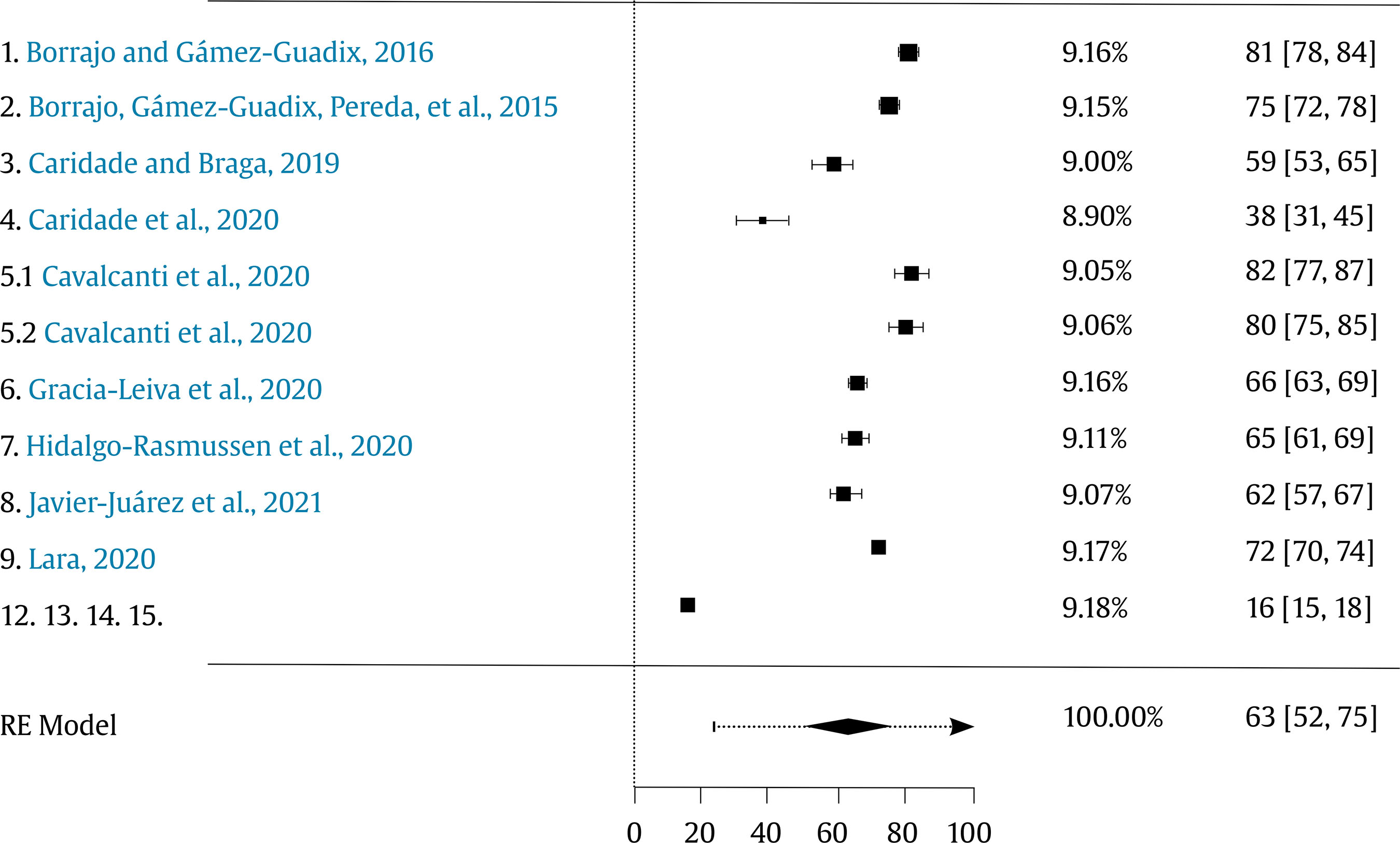

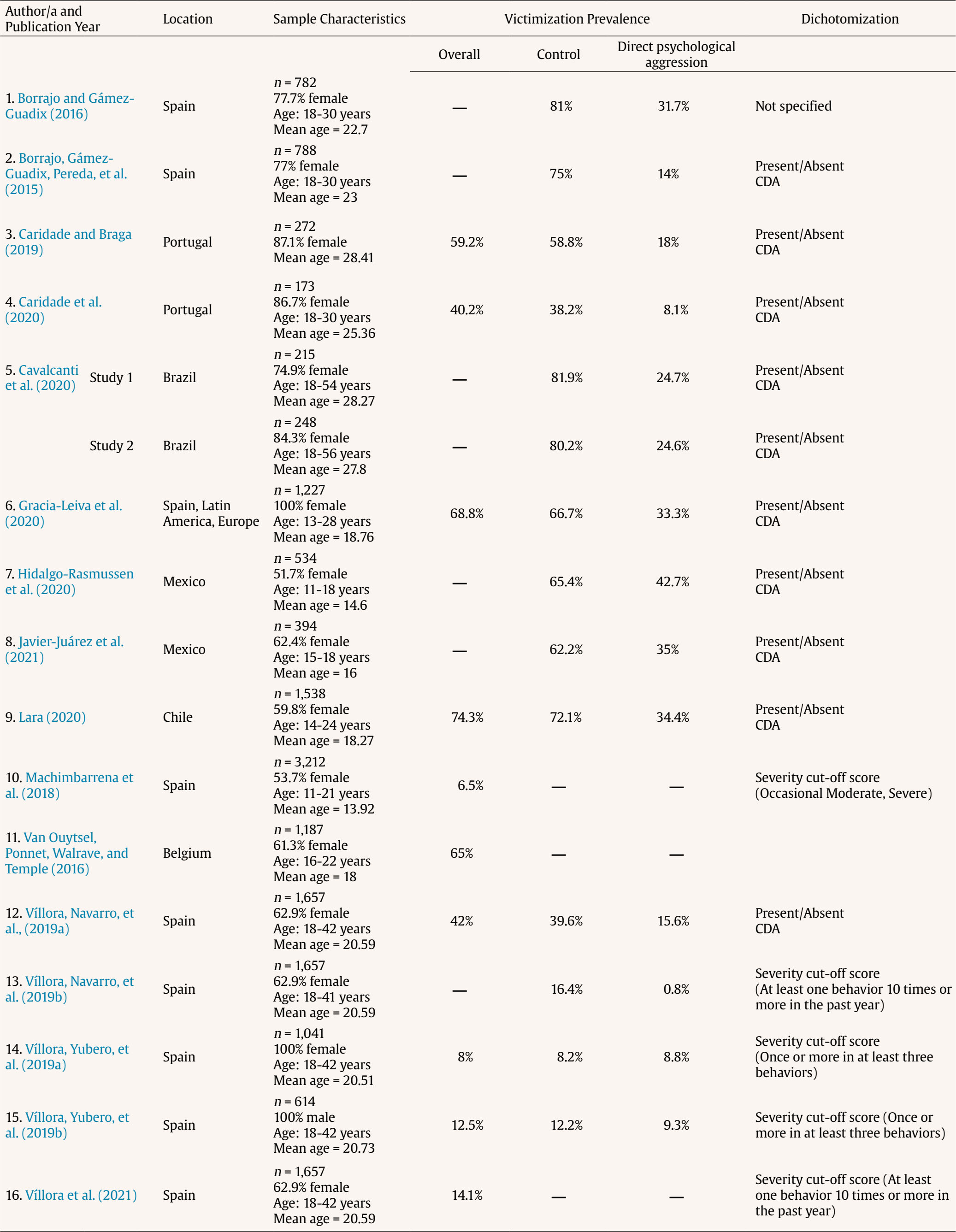

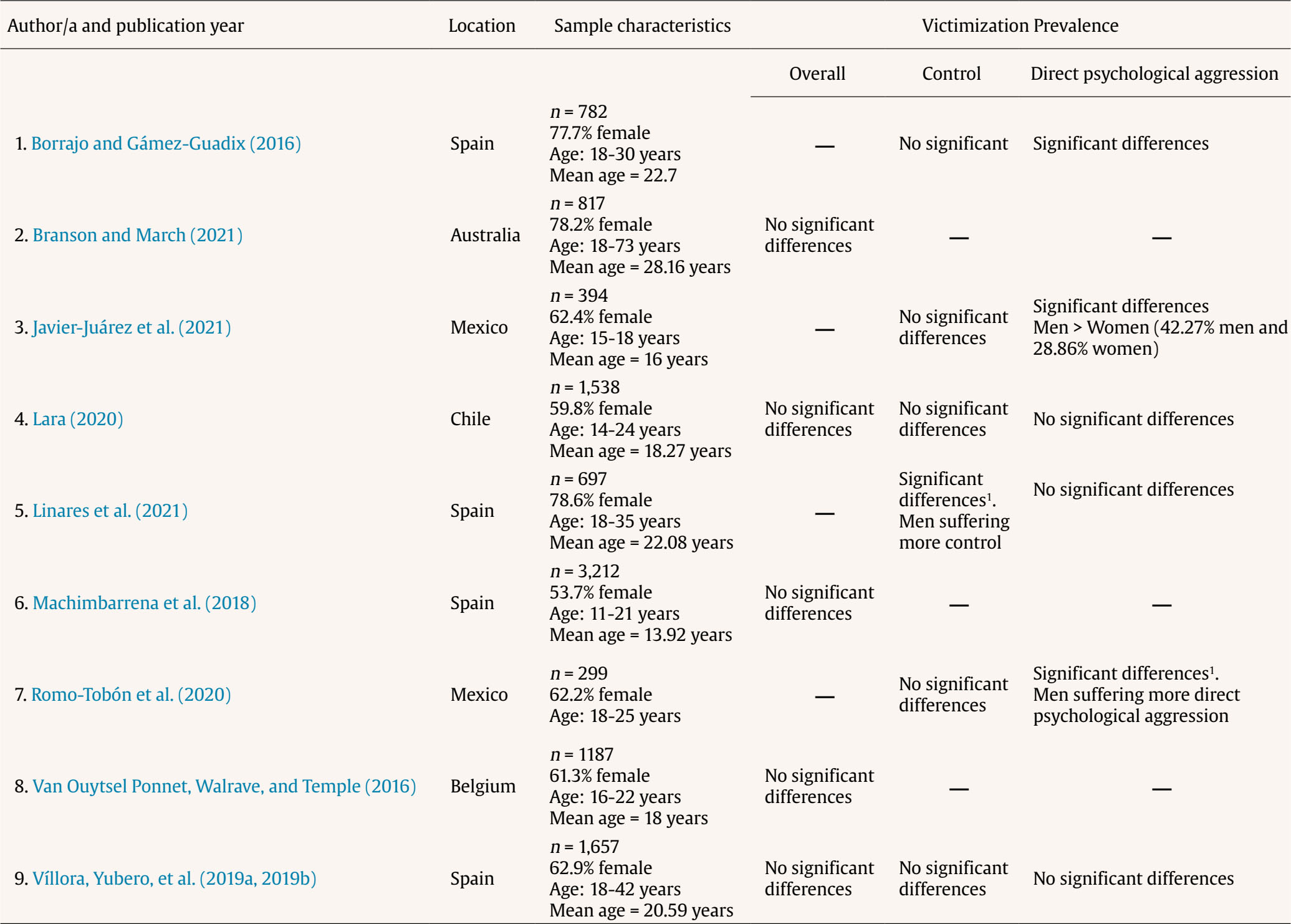

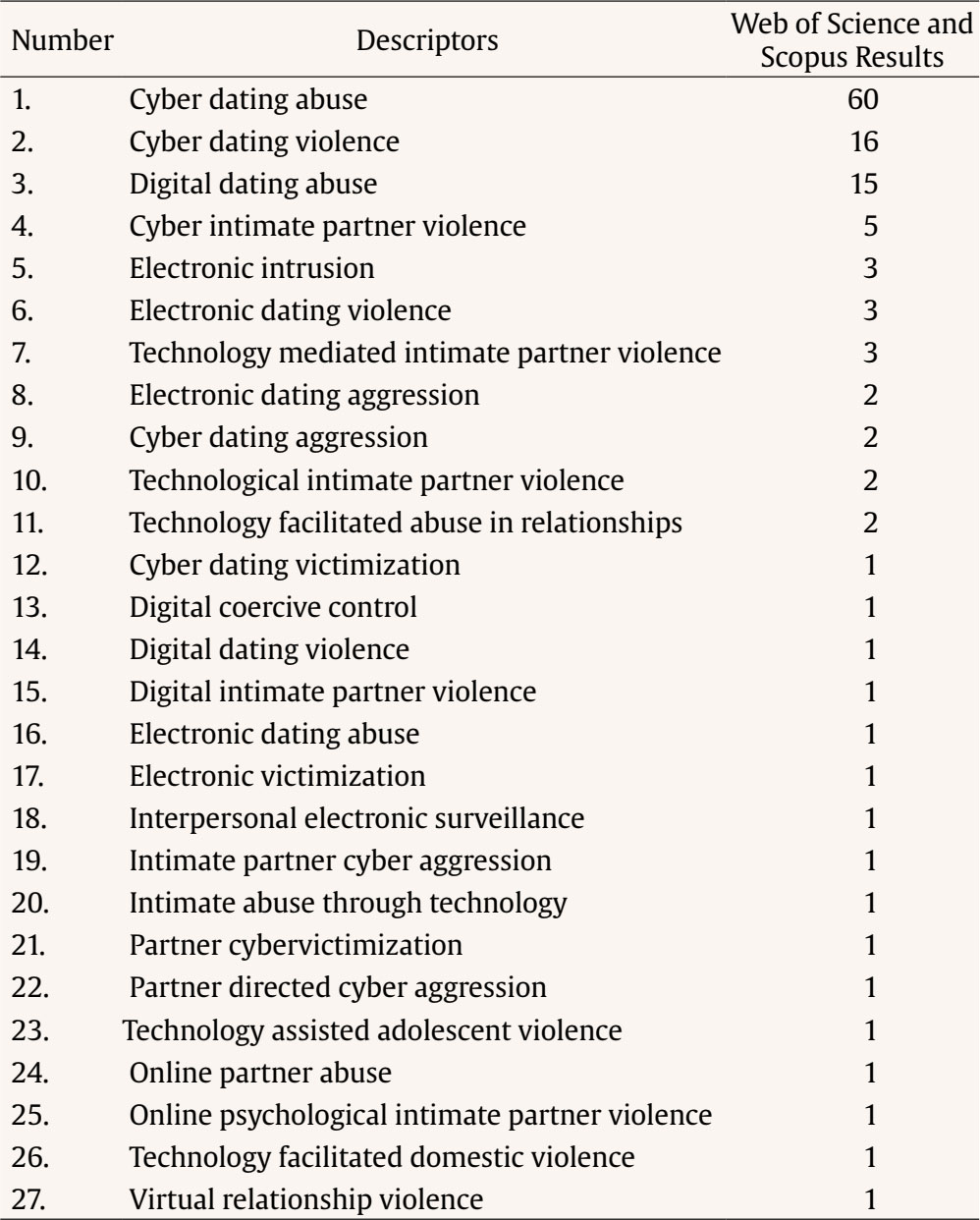

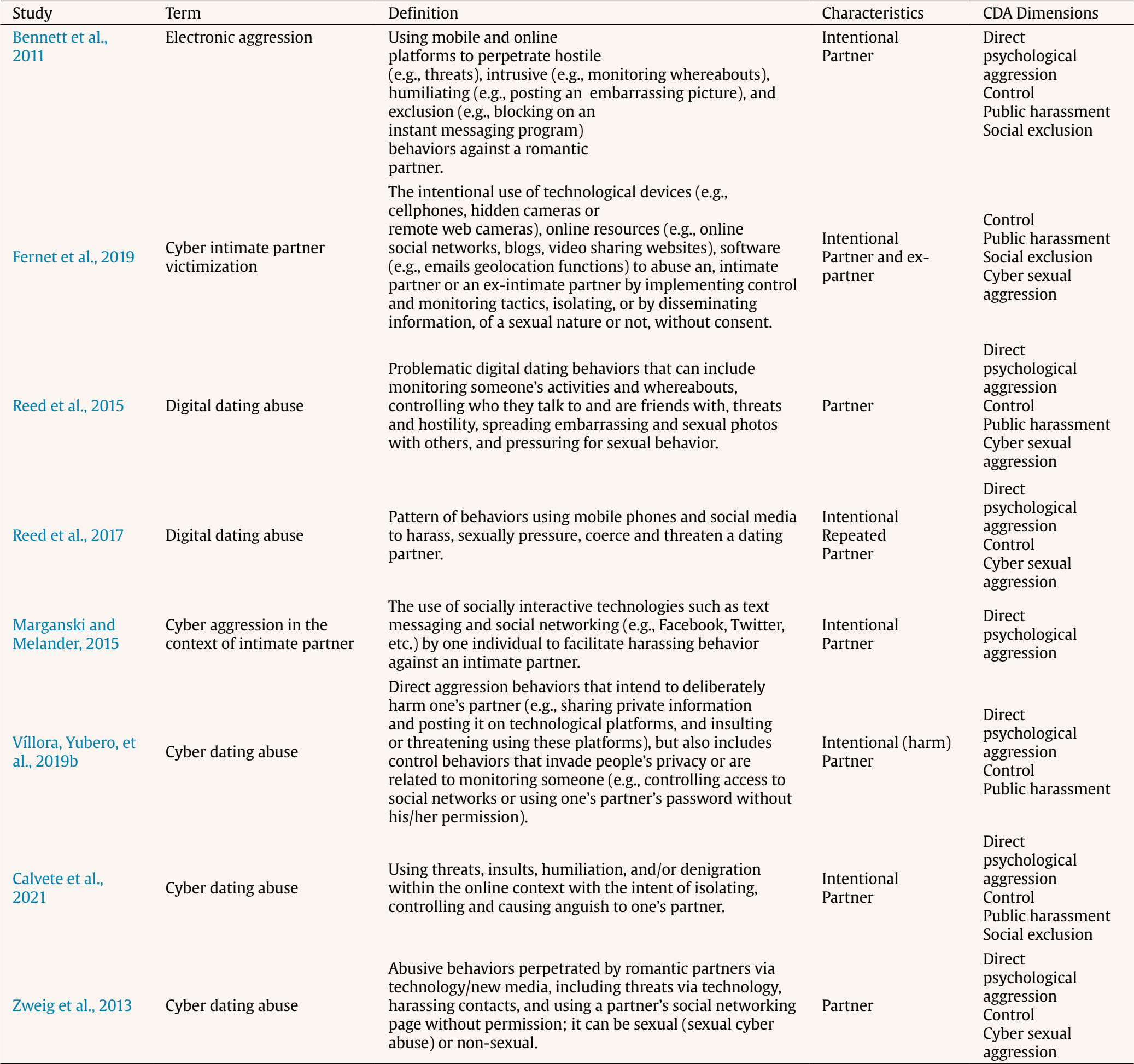

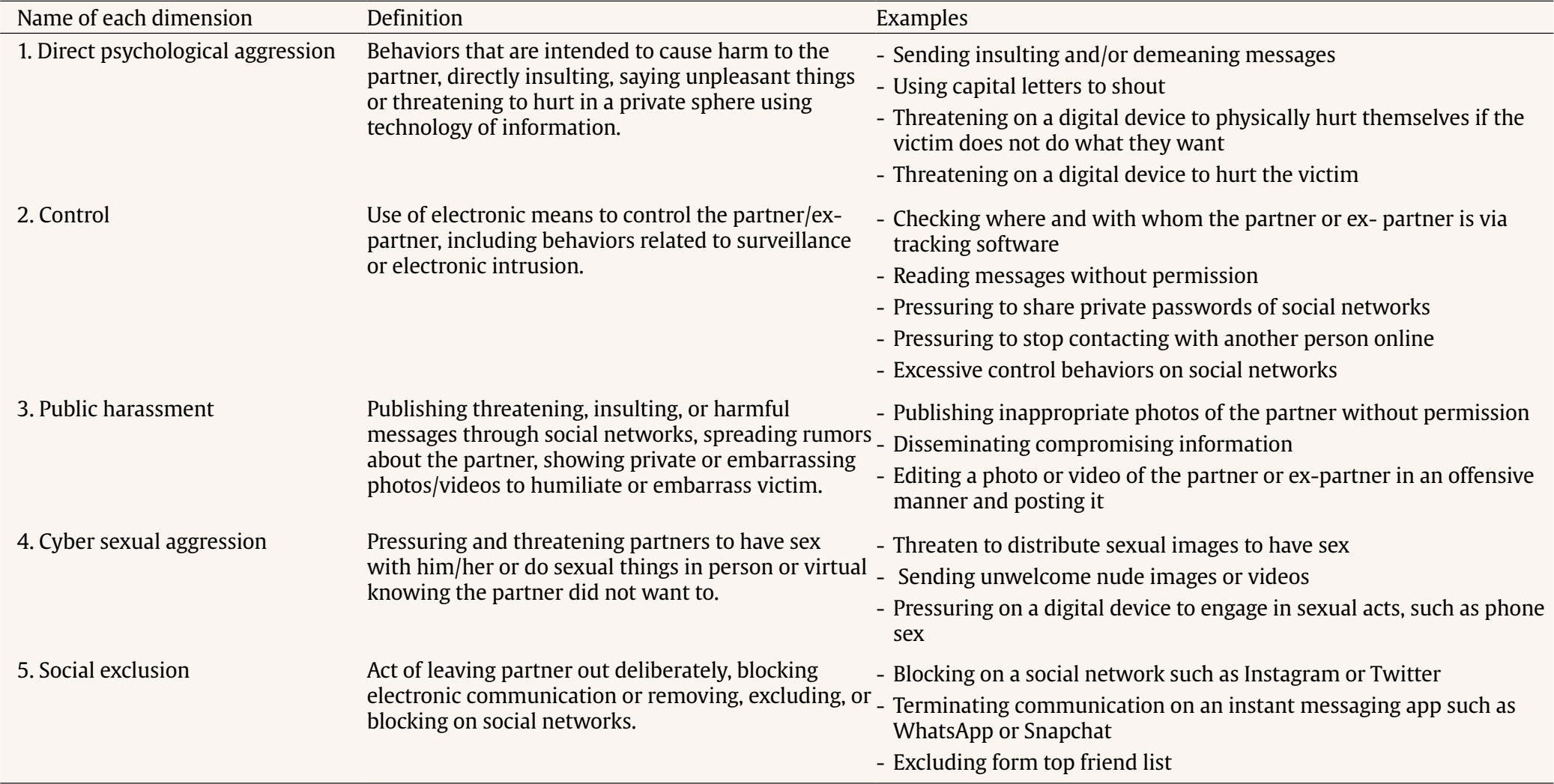

Gender-based violence is spreading to the online context. Although there is currently no uniformly accepted definition of gender based violence, Van Der Wilk (2018) describes it as any act of gender-based violence against women that is committed through the Internet or any other communication technology. In this case, perpetrators can be partners or ex-partners, colleagues, schoolmates or, as is often the case, anonymous individuals. However, cyber dating abuse (CDA) is focused on dating relationships and is an emerging form of dating violence that can be a negative experience for youth and adolescents, causing serious psychological harm to its victims (Caridade & Braga, 2020; Fernet et al., 2019). According to recent studies, the range of terminology used in the scientific community referring to this phenomenon is currently very wide and varied, probably since it is a relatively recent subject of study and there is a lack of scientific consensus on how to conceptualize and define it (Brown & Hegarty, 2018; Cavalcanti & Coutinho, 2019; Fernet et al., 2019; Flach & Deslandes, 2017). As a consequence, prevalence rates for both perpetration and victimization tend to fluctuate considerably between studies. To exemplify, previous systematic reviews found perpetration and victimization rates higher than 90% among youth (Brown & Hegarty, 2018; Caridade et al., 2020). However, these same reviews also documented prevalence rates as low as 5.8% for CDA victimization (Caridade et al., 2020) and 6% for CDA perpetration (Brown & Hegarty, 2018), concluding, in line with other studies (e.g., Flach & Deslandes, 2017; Stonard et al., 2015), that research on this type of abuse has produced extremely variable and difficult to interpret results. This variability can also be found when analyzing gender differences, as existing literature reports that CDA victimization might be gendered, but findings are mixed. For example, some studies report CDA victimization as gender symmetrical (Smith et al., 2018; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016), while other studies report victimization greater for young women (Dick et al., 2014; Zweig et al., 2013; Zweig et al., 2014), and yet others report victimization greater for young men (Brown et al., 2021; Jaen-Cortés et al., 2017). These discrepancies in prevalence rates when considering gender demonstrate the need to examine the differences between men and women in their use and experience of CDA. The use of different terms, conceptual and operational definitions, and dimensions to study CDA can hide the real prevalence rates and hinder the detection of risk factors. Gaps between terms, definitions, dimensions, and prevalence rates prevent public health agencies from developing programs adapted to the victims and their characteristics. Without clarifying the construct of CDA it is difficult to improve scientific knowledge regarding the risk factors. There is thus a need to summarize the available knowledge in order to make recommendations to scholars and social health services. Several reviews have been published in recent years, such as analyzing prevalence rates, instruments, and risk factors (Calvalcanti & Coutinho, 2019), summarizing what has been done and what is known about CDA (Caridade et al., 2019), describing the instruments created to measure intimate abuse through technology (Brown & Hegarty, 2018), and identifying how the literature defined the phenomenon, the terms used for it, the implications for health, and proposed social intervention technologies (Flach & Deslandes, 2017; Rocha-Silva et al., 2021). The objectives of the latest studies were focused on revealing the constructs and definitions used in the scientific literature, but critical analysis, theoretical discussion, or concrete proposals for future studies have not been provided. In the same way, some meta-analyses regarding CDA have been published in recent years, studying prevalence rates of victimization and perpetration of CDA along with its association with face-to-face intimate partner violence among men and women (Gilbar et al., 2022), and analyzing risk and protective factors (Caridade & Braga, 2020). Gilbar et al. (2022) conducted a meta-analysis without considering the measurement tool used by the studies, which could affect the results of the meta-analysis. Authors included some studies without using validated measures, using single item measures or not reporting psychometric properties. Any meta-analysis of the prevalence of CDA should be focused on the best validated measurement tools, and this has not been done. Research Aims The first objective of this study was to provide a literature review of the conceptualization of CDA (terms, definitions, and dimensions), with recommendations regarding the most suitable term and definition, and the dimensions that should be included in the construct. To achieve the first goal, a systematic review was carried out, ensuring transparent and complete reporting of the systematic search. Based on the outcomes of the review, this study discusses the inconsistencies found in terminology, conceptualization, and dimensions used to assess this issue. It concludes with suggestions that can help understand this type of dating violence. Figure 1 Flowchart of the Literature Review Process according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses.   The second objective was to analyze victimization prevalence rates based on the findings of those studies using the most suitable and most commonly used instrument for CDA measurement (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022), and to synthesize, through a meta-analysis, the prevalence rates of CDA taking into account dimensions and gender. Literature Review The present study is based on an integrative literature review using the PRISMA protocol (Page et al., 2021). This form of review includes studies with different methodologies in order to analyze the knowledge from previous research on CDA and generate new knowledge. This type of review shows the state of the art on a theme and contributes to the development of new theories. The identification, screening, and eligibility of the studies included are outlined in the flow diagram (see Figure 1). Search Strategies In order to identify all terms and definitions potentially relevant for the review purpose, and to avoid publication bias, the searches were conducted in two electronic databases: Web of Science (title, abstract, author keyword, and keyword plus) and Scopus (title, abstract, and author keyword). Journal articles published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese up to July 2022 were selected. Articles retrieved from these databases were exported to RefWorks in order to make the removal of duplicates much easier. The selection process was carried out by reading abstracts, but sometimes articles were removed after reading the full text. The search was limited to 27 terms (“cyber intimate victimization” OR “cyber intimate aggression” OR “cyber intimate violence” OR “cyber intimate abuse” OR “electronic victimization” OR “cyber dating abuse” OR “cyber dating aggression” OR “cyber dating victimization” OR “cyber intimate partner violence” OR “cyber dating violence” OR “digital dating abuse” OR “digital dating violence” OR “digital dating victimization” OR “digital dating aggression” OR “intimate partner violence through electronic mediums” OR “computer mediated communication based teen dating violence” OR “cyber psychological abuse in romantic relationships” OR “intimate partner cyber aggression victimization” OR “virtual intimate partner violence” OR “electronic aggression in emerging adult romantic relationships” OR “electronic intrusion cyber dating aggression” OR “electronic dating aggression” OR “technology assisted adolescent violence” OR “technological intimate partner violence” OR “partner directed cyber aggression” OR “technology facilitated domestic violence” OR “virtual relationship violence”). Eligibility Criteria Inclusion criteria were used: i) academic journals, ii) studies focused on adolescents or youth, iii) theoretical and empirical studies, iv) terms in title, abstract, or keywords, v) studies published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Figure 1 shows the literature search flowchart and the selection of articles from the analyzed sources, with a total of 129 scientific articles addressing CDA obtained. Statistical Analysis Those studies included in the review that used the best-valued and most commonly used instrument (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022) were considered for presentation of their victimization prevalence data, given that the majority of studies did not report perpetration rates. Thus, to carry out the meta-analysis, only the studies (n = 16) that used the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., 2015) were considered. Pooled prevalence of CDA victimization and two of its dimensions was estimated using event rates and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Variability was corroborated with the corresponding diagnoses of heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity of prevalence estimates was assessed using the Q test and the I2 statistic. Important variations were found across studies, with I2 > 99% (large heterogeneity). Given the substantial heterogeneity of the reviewed studies and their methodologies (the studies used different types of samples, or participants were from different populations), all pooled estimations were performed with the random effects model, utilizing the restricted maximum-likelihood estimation algorithm. Forest plots were generated for each pooled prevalence estimate. All analyses were performed with Jamovi software (Version 2.2.5) (R Core Team, 2021; The Jamovi Project, 2021) using the MAJOR statistical package. Analysis of Terms Used for Cyber Dating Abuse and the Most Suitable Term Cyber dating abuse literature uses a wide variety of terms to name the phenomenon and in this review 27 different terms were identified, as can be seen in Table 1. Analyzing the results, it is noticeable that the constructs “cyber dating abuse” (n = 60), “cyber dating violence” (n = 16), “digital dating abuse” (n = 15), and “cyber intimate partner violence” (n = 5) are the most prevalent in scientific publications. The remaining 23 terms have a lower prevalence, from one to three publications. This shows that, despite the high number of terms identified, the scientific literature has tended to adopt “cyber dating abuse”, “cyber dating violence”, and “digital dating abuse”. To talk about this phenomenon in its entirety, it is important for the term to include the three elements that form the concept (cyber/digital context, dating/romantic relationship, violence/abuse/aggression). Regarding the first element, the term “cyber” is considered to be the most suitable because it denotes a relationship with information technology, encompassing all kinds of technologies related to the virtual world as opposed to face-to-face interaction. Constructs including the term “technology-facilitated” have been criticized as it might position the technology as the problem rather than the broader causes of cyber dating abuse. As for the second element, the term “dating” is used, referring to current or former adolescent and young adult romantic relationships where the members of the couple do not live together, are not financially independent from their parents and do not have well-established relationships (Ibabe et al., 2020). Terms such as electronic victimization, technology assisted adolescent violence or electronic intrusion have been found in research on CDA, but these terms can be confused with other types of violence involving digital media, such as “cyberbullying” or “stalking”, which exclude the “dating relationship” that is key when referring to the phenomenon. Lastly, in regard to the third element, Table 1 shows that the terms “aggression/violence” and “abuse” are used indiscriminately, but it is important to emphasize they are not the same. In the context of intimate partner violence, violence is usually framed as a physical or sexual acts or behaviors (Geffner, 2016). While the terms above generally refer to isolated events, abuse encompasses an ongoing pattern of multiple forms of aggression, assumes there is a relationship between partners and considers the intent as well as the negative effects (such as helplessness, anxiety or fear) on the victim. Taking this differentiation into account, it becomes clear that “aggression”, “violence”, and “abuse” are not the same. Distinguishing between these constructs is key for research, as is keeping in mind the consequences, frequency, duration, and severity when discussing or attempting to measure these behaviors in order to provide a full picture that includes motivation, intent, and dynamics. After analyzing 27 terms related to cyber dating abuse, the recommended term to use in future studies is “cyber dating abuse”. Analysis of Definitions and the most Suitable Definition of Cyber Dating Abuse It is important to emphasize that most of the analyzed articles do not provide a clear definition of CDA or even a definition at all; this becomes a problem when developing measurement instruments, analyzing risk factors, or implementing prevention or intervention programs. The most significant definitions of cyber dating abuse found in this literature review and their main characteristics are shown in Table 2. Almost all of the analyzed definitions (n = 7) referred to the current partner only (Bennett et al., 2011; Calvete et al., 2021; Marganski & Melander, 2015; Reed et al., 2015; Reed et al., 2017; Víllora, Yubero, et al., 2019b; Zweig et al., 2013), while (n = 1) also included the ex-partner (Fernet et al., 2019). According to recent research, the definition should include both the partner and the ex-partner, as it has been shown that it is common for the ex-partner to be involved in this type of behavior. The feeling of losing control over the partner in a breakup, as well as not being able to accept the separation, could increase the occurrence of CDA or its frequency (Fernet et al., 2019). Related to the selection of the term, and as explained above, “aggression” and “abuse” constructs are used interchangeably, which might also be a definitional issue. Some behaviors can be considered abuse after just one manifestation (e.g., threatened to hurt), just as other behaviors might not be considered abuse if experienced just once or twice (e.g., insulting). Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al. (2015), in their instrument development, established that greater frequency was required for a victim’s experience to constitute abuse and higher frequency was associated with higher levels of abuse. Therefore, to consider the presence of abuse, there should be a pattern of behavior, that is, these behaviors should occur repeatedly. The definition of Reed et al. (2017) includes a “pattern of behavior”, implying repeated actions. However, the other analyzed definitions did not address this issue. Most of the definitions (n = 6) imply intentional behavior (Bennett et al., 2011; Calvete et al., 2021; Fernet et al., 2019; Marganski & Melander, 2015; Reed et al., 2017; Víllora, Yubero, et al., 2019b). Intention is an important element of abuse, but behaviors occurring without the conscious or explicit intent to harm might also be considered abusive. An important percentage of victims reported a playful or joking context in which cyber dating abuse had occurred, which does not imply an explicit intend to harm (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, & Calvete, 2015). Therefore, the definition of CDA should include intentional or conscious behavior, but it should not specify that the intention is specifically to harm one’s partner or ex-partner since the explicit perpetrator’s intentions are hard to determine in this particular type of abuse. Thus, the most suitable definition of CDA is the use of technology and digital media to perpetrate any abusive behavior deliberately and repeatedly towards the partner or ex-partner in the context of a dating or courtship relationship. Analysis of CDA Dimensions and Proposal In the definitions presented in Table 2, it can be seen that diverse terminology has been used when referring to the same dimension of CDA, which can blur the sets of behaviors that should be part of the phenomenon (Rocha-Silva et al., 2021). Different terminologies have been found to refer to behaviors of direct psychological aggression (e.g., hostility, threats, denigration, insults), control (e.g., controlling, monitoring, intrusion, coercion, surveillance), public harassment (e.g., humiliation, sharing private information, and spreading embarrassing photos), cyber sexual aggression (e.g., pressure for sexual behavior, sexual cyber abuse, disseminating information of a sexual nature), and social exclusion (e.g., exclusion, isolation). Despite these terminological differences in the dimensions, the analysis of such behaviors shows that they refer to the same core behaviors, which are displayed in Table 2 in the column named Dimensions. Rodríguez-Domínguez et al. (2020) pointed out methodological deficiencies in the construction of knowledge in the field of CDA, indicating, for example, a lack of attention to manifestations of cyber sexual aggression. In the analyzed definitions, direct psychological aggression (n = 7) and control (n = 7) were the dimensions that appeared the most frequently. Public harassment appeared in five definitions of CDA, with cyber sexual aggression (n = 4) and social exclusion (n = 3) the least considered dimensions. It is not easy to establish a definitive classification of CDA dimensions due to emerging new behaviors related to technology use, and because there is no consensus in the scientific literature. However, to advance the conceptualization, five potential dimensions for CDA based on the qualitative analysis of studies are proposed in Table 3, with their terminology, definitions and examples. The first proposal for CDA dimensions (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022) has been improved in the current study. Meta-analysis of the Victimization Prevalence Rate For this section only those studies using the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (CDAQ) (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., 2015) were included to reach a valid conclusion about victimization prevalence rate (see Table 4). The studies 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 (Víllora, Navarro, et al. 2019a, 2019b; Víllora, Yubero, et al., 2019a, 2019b; Víllora et al., 2021) performed their analyses using the exact same sample. Therefore, for the purpose of this meta-analysis, their prevalence rates had to be pooled in order to avoid sampling errors that could affect the results. Overall Victimization Heterogeneity of overall victimization was very large, Q(7) = 5,947.478, p < .001; I2 = 99.84%. The forest plot in Figure 2 shows the summary of the prevalence of cyber dating violence victimization (with a combined sample of n = 9,266) with an estimated global prevalence of 47% (95% CI [27, 67]). Variability ranged from a minimum of 7% (95% CI [6, 7) to a maximum prevalence of 74% (95% CI [72, 77]). Figure 2 Forest Plot of Overall Victimization Prevalence Rate.   Note. See Table 4 to identify each study. The prevalence scale goes from 0 to .80, which is equivalent to 0 to 80%. The individual results of each study are represented with a square and their corresponding confidence interval with a line through the square. The larger the size of the square, the greater the importance of the study (random weight). The global prevalence that integrates the information from all the studies is represented by the diamond-shaped figure (effect size), whose length corresponds to the length of the confidence interval of the global prevalence. Thus, there is a global prevalence for each analysis group. Control Heterogeneity of control was very large, Q(11) = 2,869.174, p <.001; I2 = 99.32%. Figure 3 shows the summary of the prevalence of control victimization (with a combined sample of n = 7,846) with an estimated global prevalence of 63% (95% CI [52, 75]). Variability ranged from a minimum of 16% (95% CI [15, 18]) to a maximum prevalence of 82% (95% CI [77, 87]). Figure 3 Forest Plot of Control Victimization Prevalence Rate.   Note. See Table 4 to identify each study. In this forest plot, the prevalence scale corresponds to a proportion that goes from 0 to 100%. Tabla 4 Victimization Prevalence Rates of the Studies Using the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (CDAQ) (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda et al., 2015)   Direct Psychological Aggression Heterogeneity of direct psychological victimization was proved, Q(11) = 2,260.839, p < .001), being very large (I2 = 99%). The forest plot in this figure shows the summary of the prevalence of direct psychological aggression victimization (with a combined sample of n = 7,846) with an estimated global prevalence of 24% (95% CI [17, 32]). Variability ranged from a minimum of 1% (95% CI [0, 1]) to a maximum prevalence of 43% (95% CI [39, 47]). In order to analyze one of the potential reasons for the heterogeneity observed in prevalence rates of CDA, the different criteria to determine the prevalence rate (present/absent or severity cut-off criteria) was reported. As can be seen in Table 4, studies using a dichotomous criterion (present/absent) report higher prevalence rates (overall victimization from 74.3% to 40.2%) than those relying on severity cut-off scores (overall victimization from 6.5% to 14.1%). A possible explanation for all of the above variability observed in prevalence rates of CDA is that, as opposed to a severity cut-off criterion, a dichotomous criterion does not necessarily capture the repetitive nature or severity of CDA victimization and therefore tends to provide higher prevalence rates. Gender Differences in CDA Victimization Gender differences across victimization of CDA were analyzed and presented in nine of the studies using the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (CDAQ; Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., 2015), as shown in Table 5. Regarding overall victimization, six studies did not found any significant differences between men and women victimization (Branson & March, 2021; Lara, 2020; Machimbarrena et al., 2018; Van Ouytsel, Ponnet, Walrave, & Temple, 2016; Víllora, Yubero, et al., 2019a, 2019b). Tabla 5 Gender Differences in CDA Victimization of the Studies Using the Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (CDAQ) (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., 2015)   Note. 1Prevalence rates in men and women were not reported. Figure 4 Forest Plot of Psychological Direct Aggression Victimization Prevalence Rate.   Note. See Table 4 to identify each study. In this forest plot, the prevalence scale goes from 0 to .50, which in terms of percentages is equivalent to 0 to 50%. When analyzing gender differences across the behavioral dimensions of cyber dating abuse separately, some variability was found. Seven studies provided information on the control dimension but just one (Linares et al., 2021) found significantly more control victimization among men than women. Regarding direct psychological aggression, seven studies analyzed the victimization level, and significant differences were shown in three of the studies (Borrajo & Gámez-Guadix, 2016; Javier-Juárez et al., 2021; Romo-Tobón et al., 2020), with men reporting more direct psychological aggression victimization than women, although the differences were not very marked (first study 38.5%-29.6%; second study 42.27%-28.86%; the third study did not reported prevalence rates). In general, these results show an absence of significant gender differences to a large extent, which could be evidence of gender symmetry. However, there is a need for further exploration and scientific clarification to wholly comprehend the phenomenon and its dynamics. One of the main objectives of this study was to analyze the conceptualization of cyber dating abuse, with recommendations regarding the most appropriate term, a complete definition of the construct and the its dimensions. To achieve this goal, a systematic review was carried out, ensuring transparent and complete reporting of the systematic search. A further goal was to analyze the victimization prevalence rates of CDA, taking into account its dimensions and gender differences. In the present systematic review, 129 papers referring to cyber dating abuse on youth and adolescents were analyzed. With most of the studies published in the last five years, the growing interest of the scientific community in this phenomenon is clear and highlights not only a problem that affects boys and girls in their romantic relationships but also the need to define the construct more clearly and comprehensively. This review confirmed that CDA literature uses a wide variety of terms to name the phenomenon, and these definitions present different characteristics. After analyzing all definitions, we recommend the use of the term “cyber dating abuse”, and have proposed a definition of CDA including all characteristics found. Specifically, CDA is understood as the use of technology and digital media to perpetrate any abusive behavior deliberately and repeatedly towards the partner or ex-partner in the context of a dating or courting relationship. In general, the definitions analyzed and the assessment instrument used in the studies and included in the meta-analysis did not contain the five dimensions proposed in this review, namely, direct psychological aggression, control, public harassment, cyber sexual aggression, and social exclusion. The behavioral dimensions that were more frequently included in the definitions and in the assessment tool were direct psychological aggression and control. The least mentioned dimensions were cyber sexual aggression (which includes pressuring and threatening partners to have sex in person or virtually) and social exclusion (which involves blocking on social networks or friend lists). However, it is important to take into account these two dimensions in CDA research when exploring the prevalence and impact of this type of abuse in order to capture the full range of experienced CDA behaviors. A meta-analysis of 16 studies, involving 14,235 participants, was also conducted in order to examine the frequency of cyber dating abuse victimization in adolescents and youth, based on the most used instrument, the CDAQ (Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., 2015), also considered a promising tool (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022). To our knowledge, the current review was the first to explore the victimization prevalence of adolescents and youth CDA, including studies using the same measurement instrument, in an attempt to provide a comprehensive picture of the occurrence of this phenomenon. The meta-analysis indicated an estimated global prevalence of CDA victimization of 47%; for the control dimension the prevalence was 63% and direct psychological aggression showed a 24% of victimization. Regarding gender differences, the majority of the studies analyzed provided evidence of the non-existence of significant gender differences, both in overall victimization and in the two dimensions of victimization analyzed (direct psychological aggression and control), which could be suggesting gender symmetry in cyber dating abuse. According to Straus (2011), gender symmetry means approximately equal rates of perpetration of non-sexual physical assaults by men and women partners, or slightly higher rates by women partners. Knowing the state of the art on cyber dating abuse can provide a better understanding of this opaque phenomenon, as well leading to reflection on new forms of intimate partner violence and gender-based violence, now also assisted, or aggravated by the use of technologies. In fact, cyber gender-based violence is increasing (Hinson et al., 2018) due to the community connectivity and in response to the rise of the feminist movement (Chan, 2022). These new realities should be taken into account in theoretical and legal frameworks. In fact, in Spain, the Organic Law 1/2004 on Comprehensive Protection Measures against Gender Violence does not even mention any of these phenomena. Therefore, it would be necessary that future judicial reforms include and regulate these types of abuse. In any case, it is essential to identify the victims and make available all the necessary resources for their attention, as well as to implement policies to prevent cyber dating abuse and cyber gender-based violence. Limitations and Strengths Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results and taken into account by further research. First, the review did not include unpublished studies (dissertations and research reports), and therefore significant versus non-significant results could have been over-represented in this meta-analysis (i.e., publication bias). Second, the generalizability of the findings may be questioned. It is unknown whether the prevalence estimates of CDA victimization differ: (a) in other cultures (the studies were conducted mostly in Western cultures); (b) according to the participants’ age; (c) according to sexual orientation; and (d) according to different romantic relationships. Another limitation of the study may be the presence of substantial heterogeneity of studies in the meta-analysis. Thus, it is inappropriate to derive an estimate of an overall prevalence rate from that particular set of studies. The heterogeneity observed in the prevalence rate could be due to the procedure followed for the dichotomization of CDA (present/absent or severity cut-off criteria), and it is possible that no real differences in prevalence between the different populations existed. Despite the mentioned limitations of the current study, one of strengths is that an exhaustive literature review was made using the PRISMA method, showing the constructs and definitions used in the scientific literature, and critical analysis, theoretical discussion, and concrete proposals for future studies have been provided. A previous review (Rocha-Silva, 2021) had already described terms, definitions and dimensions, but no proposals were made. A further strength is that all studies included in the meta-analysis were carried out with the same questionnaire (Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire; Borrajo, Gámez-Guadix, Pereda, et al., 2015), an instrument that has shown positive and good-quality evidence in its psychometric properties (Martínez-Soto & Ibabe, 2022). Conclusion Cyber dating abuse is a highly prevalent problem among adolescents and young people which has been related to several negative experiences for victims of this type of abuse. This bibliographic and meta-analytic review sheds light on the field of CDA by addressing the terminology regarding cyber dating abuse. The construct would include five dimensions, and its overall prevalence of victimization (47%) should be understood with caution due to excessive heterogeneity. Consistent with the proposed definition of CDA, which includes a repeated pattern of abusive behavior towards the partner or ex-partner, studies that include a severity criterion in their measurement would be the most appropriate; thus, the overall victimization prevalence rate should be between 14.1% and 6.5%. Since prevalence rates vary according to the criterion used (dichotomous vs. severity cut-off score), researchers should provide a rationale or justification for using one criterion over the other depending on the research goals. The risk of CDA begins in preadolescence and it is important to note that perpetration and victimization often co-occur (Thulin et al., 2022) at similar rates among boys and girls. Thus, in the future, it is important that research in the field of CDA emphasizes issues of gender and sexual minorities of young people. Indeed, despite research indicating that LGTB adolescents and youth experience higher prevalence of cyber dating abuse (Dank et al., 2014), there has been very limited study among these youth. Further investigation of the prevalence, predictors, and consequences of CDA adolescents is necessary to develop effective prevention and intervention programs (Dank, et al., 2014; Flach & Deslandes, 2017). Currently available dating violence prevention programs have been mainly focused on “offline” dating violence rather than CDA. Prevention programs would help young people recognize the signs and expressions of this type of violence, and provide ways to protect against it (e.g., by raising awareness of the importance of not sharing private information on the Internet, explaining how to select safe passwords, or by aiming to modify potentially dangerous attitudes, such as those related to the myths of romantic love or sexist attitudes). In addition, prevention efforts could also focus on the potential legal consequences of certain aspects of cyber dating abuse, such as unauthorized access to another person’s email or the dissemination of private information or photos without the victim’s consent, being punishable by data protection legislation. The results of this study could also suggest that gender symmetry and violence bidirectionality could be the most prevalent pattern in cyber dating abuse. According to different studies carried out on intimate partner violence (Geffner et al., 2016; Pereda & Tamarit, 2019; Straus, 2008), one of the aspects that generates the most controversy in the field of intimate partner violence (IPV) is the existence of a pattern of gender symmetry or asymmetry, that is, whether IPV is primarily perpetrated by men as compared to women (Brown, 2012). Although studies conducted from a gender perspective have identified patriarchy as the main factor influencing men’s violence against women (Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2019), family violence researchers (e.g., Straus, 2008; Straus, 2011) present quite a different view, showing that both men and women report the same amount of violence between them and their partners. Thus, denying the existence of gender symmetry and a pattern of bidirectionality in CDA could have serious consequences, such as a) developing ineffective prevention and treatment programs by not considering the whole reality of the phenomenon, b) not offering any help resources to male victims, who also present serious consequences (Pereda & Tamarit, 2019), c) having no impact on women who use abusive behaviors in their dating relationships, and d) potentially ignoring couples in the LGB community also suffering and perpetrating CDA. Beyond any debate about gender, violence and abuse of any kind by either partner, no matter what his/her gender or his/her partner’s gender is, is unacceptable and all efforts must be directed to eliminating it. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Martínez-Soto, A. & Ibabe, I. (2023). Cyber dating abuse: Conceptualization and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 133-144. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a11 References |

Cite this article as: Martínez-Soto, A. & Ibabe, I. (2024). Cyber Dating Abuse: Conceptualization and Meta-analysis of Prevalence Rates. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 133 - 144. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a11

Correspondence: amartinez275@ikasle.ehu.eus (A. Martínez-Soto)

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS