Indicators of Child Victimization in High-conflict Divorce: Interprofessional Consensus Based on a Delphi Panel

[Indicadores de victimización infantil en los casos de divorcio muy conflictivo: consenso interprofesional basado en un panel Delphi]

Mila Arch, Josue Garcia-Arch, and Noemí Pereda

Universidad de Barcelona, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a1

Received 1 September 2022, Accepted 5 June 2023

Abstract

Highly conflictive divorces represent a serious problem that affects the health of the children involved. Thus, in addition to the consequences derived from a tense and difficult judicial procedure, children experience the negative effects of inappropriate parental behavior that can have an impact on their health and development. To date no work has formally addressed the identification of parental behaviors that may be considered victimizing to children. In the present study, we explore the specific indicators that could define that a child is suffering victimization due to some undesirable behavior or attitude displayed by his or her parents in the specific context of high-conflict divorce. The sample consisted of an interprofessional group of experts (psychologists, judges, lawyers, prosecutors) at the national level (n = 15). The results showed a high consensus among professionals on the majority of inappropriate parental behaviors. This study is the first to provide a list of victimizing behaviors of children in the context of high-conflict divorce that may guide future interventions and prevention policies to mitigate the effects they experience during this process.

Resumen

Los divorcios que son muy conflictivos representan un grave problema que afecta a la salud de los niños afectados. Además de las consecuencias derivadas de un procedimiento judicial tenso y difícil, los niños experimentan los efectos negativos de un comportamiento parental inadecuado que puede repercutir en su salud y su adecuado desarrollo. Hasta la fecha no hay ningún trabajo que haya abordado formalmente la identificación de los comportamientos parentales que pueden considerarse victimizadores para los niños. En el presente estudio se exploran los indicadores específicos que podrían definir que un niño está sufriendo victimización debido a algún comportamiento o actitud indeseable de sus padres en el contexto específico de un divorcio que sea muy conflictivo. La muestra está conformada por un grupo interprofesional de expertos (psicólogos, jueces, abogados y fiscales) a nivel nacional (n = 15). Los resultados mostraron un gran consenso entre los profesionales sobre la mayoría de las conductas parentales inadecuadas. Este estudio es el primero que proporciona una lista de conductas victimizadoras de los niños en el contexto de un divorcio muy conflictivo que puede orientar futuras intervenciones y políticas de prevención para mitigar los efectos que experimentan durante este proceso.

Palabras clave

Divorcio muy conflictivo, Victimización infantil, Comportamiento de los padres

Keywords

High-conflict divorce, Child victimization, Parental behavior

Cite this article as: Arch, M., Garcia-Arch, J., & Pereda, N. (2024). Indicators of Child Victimization in High-conflict Divorce: Interprofessional Consensus Based on a Delphi Panel. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 41 - 46. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a1

Correspondence: march@ub.edu (M. Arch).

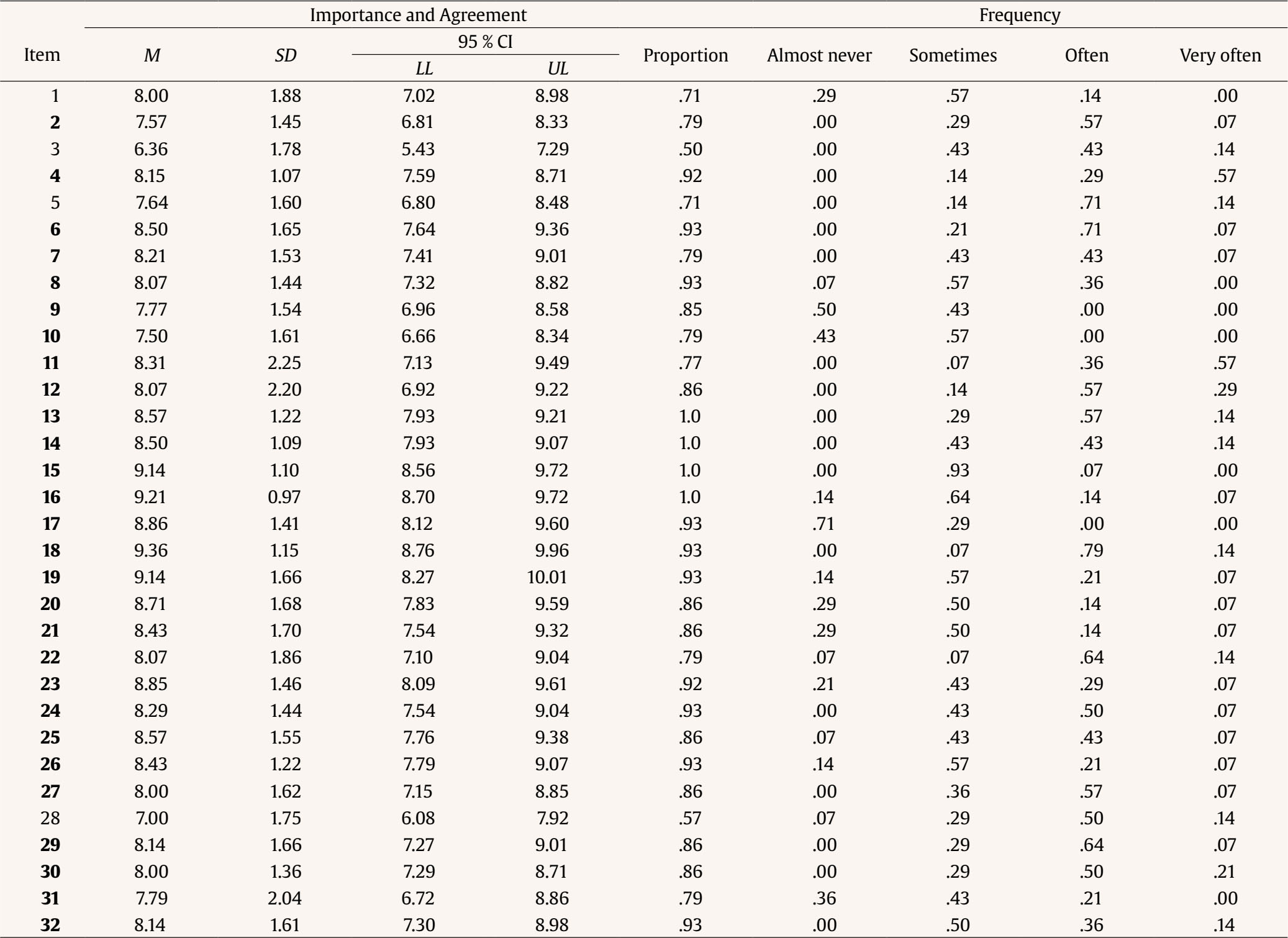

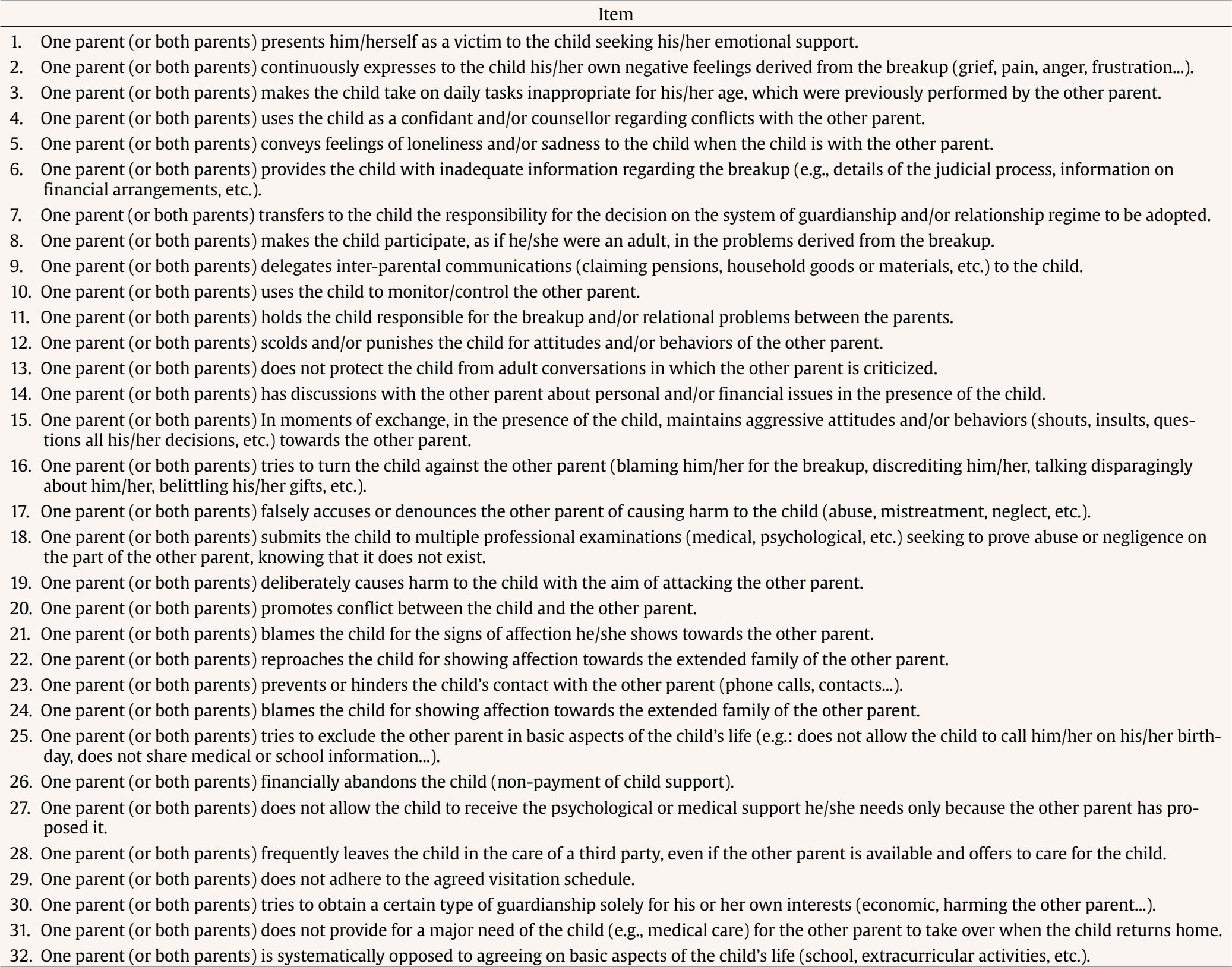

In Spain, more than 41,000 marriages with minor children were divorced in 2019 Consejo General del Poder Judicial [CGPJ, 2021]. To these rates we should add the data referring to the break-up of couples that are not legally married, which are estimated to be similar to those cases with a legal bond. Thus, in Spain around 8,800 children are believed to face the situation of their parents’ break-up every year. Despite the short history of divorce in our country, the data show that the divorce rate is similar to the one reported in the countries with the longest tradition of divorce in Europe and North America (see European Statistics [EUROSTAT, 2022] and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC, 2022]). Data also reveal that about 50% of the cases registered by the system need to be resolved through litigation, i.e., using the traditional adversarial system, which entails a high emotional and economic cost and often contributes to an escalation of interparental conflict, invading children’s daily lives (Johnston, 2000; Joyce, 2016). At the international level, estimates on high conflict and high judiciary conflict break-ups of couples with children have historically been one third of the total cases (Arch & Fabregas, 2020; Fischer et al, 2005; Joyce, 2016; King & Heard, 1999) and the situation tends to remain unchanged after the time estimated for the re-stabilisation of the family system (Fischer et al, 2005; King & Heard, 1999; Maccoby & Mnookin, 1992; Mitcham-Smith & Henry, 2007). The constant involvement of these parents in the legal system – often directly and inconveniently involving the children – not only does not contribute to conflict resolution (Johnston, 2020) but also contributes to perpetuating the conflict (Francia et al., 2019), which increases the risk of emotional harm for children (Harold & Sellers, 2018). These situations of highly conflictual separation are not only difficult to resolve, but also result in the family being immersed in what some authors have called a ‘perpetual cycle’ of conflict (Mitcham-Smith & Henry, 2007) that often results in the victimization of the children involved (Joyce, 2016). Children going through this experience tend to suffer emotional neglect, with psychological consequences similar to those experienced by children who are victims of physical abuse. The unavoidable negative implications of this phenomenon have led to its clear identification by classical studies as a public health problem (Areen, 1975). There is no doubt that the exposure to a highly conflictual divorce has negative effects on children at physical, emotional, and relational levels (Cummings & Davies, 2010; Cummings et al., 2015; Grych & Fincham, 2001; Harold & Sellers, 2018) that are likely to persist into adulthood (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002). Importantly, evidence of negative effects on children’s mental health as a result of this type of situation has been recently included in the DSM 5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA, 2018]) under the diagnostic category of “child affected by parental relationship distress”, within the chapter on “other conditions that may be subject to clinical attention.” Many of the identified effects relate to what is valued as a form of psychological or emotional abuse, a common form of neglect in these cases (Joyce, 2016). For instance, some parental behaviors place children in a highly stressful situation that sometimes leads them to experience a parental loyalties conflict (Afifi & McManus, 2010; Bernet et al., 2016; Verrocchio & Backer, 2015), which is considered as a specific form of psychological maltreatment (Binggeli et al., 2001). Although these attitudes and behaviors may not be the intentional result of one or both parents, they will inevitably cause negative consequences for children, such as physical, social, educational, and emotional impairments (Joyce, 2016), and might require the Child Protective Services to step in and protect the emotional well-being of children during high-conflict divorce cases. Along the same lines, the Council of Europe (2021) notes that in many cases the experience that children will go through in the case of complex, high-conflict divorces, and especially those where the custody of the children and adolescents is involved, can be compared to situations of ‘alternative care’, that is, situations in which the child may be considered destitute due to possible child risk situation. As can be appreciated, although it is known that in these cases the displayed parental attitudes and behaviours can be harmful for children, there is still little information and consensus regarding their concretion. This is a fundamental issue that has to be addressed to be able to design protocols aimed at the detection and prevention of potentially victimizing behaviours. It would be difficult to effectively intervene or prevent the problem if we do not gain a more fine-grained knowledge of the ways in which it manifests itself. This situation makes it necessary to initiate a research line capable of identifying and understanding these behaviors with the aim of providing the competent bodies and professionals with the necessary tools. Aim of the Study The aim of this study is to identify specific indicators of victimization in children that result from behaviors or attitudes exhibited by one or both parents during a highly conflictive divorce. Given the lack of existing literature on the topic, the study employs the Delphi method to gather insights from professionals in the field who have observed such behaviors in their practice. By identifying these indicators, the study aims to improve the detection of victimization in this specific context, and to equip professionals with tools to detect and intervene in such cases effectively. Participants To ensure a diverse and experienced panel of experts, we invited a group of national researchers and practitioners recognized for their contributions to the field. We identified potential participants through our extensive network of contacts and selected those with at least 10 years of specific accredited experience in the field for practitioners, and a demonstrated trajectory of research and publications for researchers. In addition, we took into account their participation in conferences and other scientific events. We contacted the selected experts via email and invited them to participate as panellists in a Delphi Panel. In total, we invited 18 experts, including psychologists, judges, lawyers, and prosecutors. Of these, 16 agreed to participate in the Delphi Panel, and 15 of them completed the two rounds of the Delphi process. The final multidisciplinary sample was composed by 15 experts (12 women; M = 59.14, SD = 7.48, 95% CI [54.82, 62.46]) highly experienced in the field (min = 15 years, max = 42 years, M = 28.78, SD = 7.91, 95% CI [24.21, 22.35]). Five of them were forensic psychologists, 4 family court judges, 2 family lawyers, 2 specialized university professors, 1 parentality coordinator and 1 family law prosecutor. Procedure To accomplish the main goal of this study we chose to rely on the Delphi method. The choice was based on the fact that this method is highly versatile and has provided with valuable knowledge in numerous studies and fields (e.g., Benavente et al., 2021; Expósito-Vizcaino et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2008; Martínez-Ezquerro et al., 2021). Its objective is to reach the most reliable consensus among the opinions of a group of experts, avoiding direct confrontation between them (Almenara & Moro, 2014). It is a qualitative technique that is especially useful in non-exact disciplines, in situations of uncertainty or when objective information is lacking. The basic defining characteristics of the technique are that: a) it is an iterative process – with several rounds of responses that allow for reflection, b) it is anonymous – no member of the panel knows who has offered a particular response, c) it has controlled feedback after each round of responses, and d) if a numerical assessment is requested, it provides a statistical response from the group (Varela-Ruiz et al., 2012). We considered that this was the procedure that best suited the objective of our study: obtaining experts’ consensus regarding specific parental behaviours or attitudes that victimize children who are immersed in highly conflictive divorce situations. Study Construction Process The aim of the study was to address a complex topic on which there is no clear consensus to date, despite its importance and impact on children’s lives. Acting accordingly, and given the lack of available empirical data, we designed a first survey with open-ended questions where experts from the legal and forensic psychology fields were asked to give their opinions based on their professional experience. The main aim of this first survey was to capture as much information as possible, while preserving the interpretability and the possibility of classification of the answers given by the experts. To this end, the initial survey was designed as follows: first, experts were asked to list, according to their professional experience in the family setting, all the behaviors they had witnessed during their professional practice that could be related to child victimization in the context of a contentious divorce. After this open question, which had no word limit, they were offered another space for them to add any comments, clarifications or reflections that could nuance or complement their own list of behaviors. Aware of the difficulty of recalling all the behaviors that the experts might have witnessed and in order not to lose information and obtain a list of behaviors as exhaustive as possible, the survey included a third question with the same format as the first one. There, professionals were asked to reflect once again on their experience in this area and were reminded that the behaviors to be included could by related to a wide range of topics (e.g., economy, care, violence, etc.). Finally, they were again offered a space to share any clarifications, nuances, or comments. Once experts’ responses were received, the research team conducted a thorough reading of all the behaviors reported by the panelists (122 total behaviors reported). The screening and selection system was carried out in the following way: after the responses had been cleared, we proceeded to identify (A) complex responses that were difficult to categorize as behaviors and (B) responses that were not related to the main topic. Responses susceptible to meet at least one of the two (A, B) criteria were independently flagged by two researchers. Responses with 2 flags were directly excluded and responses with only one flag were reviewed by a third researcher to determine if they were susceptible to be included (or excluded). After this process a total of 38 responses were excluded. Subsequently, both researchers identified duplicates (identical or almost identical responses) in the responses and responses with similar content in order to eliminate them (in the case of duplicates) or derive a unique response from those similar. Once the final list of behaviors (n = 32) was obtained, we proceeded to derive items for each of them. Given the multidisciplinary nature of the study, items were written to avoid technicalities and several of them contained explanatory examples. To ensure that items to be sent to the experts in the subsequent phase were sufficiently clear, we recruited an independent sample of 5 experts (2 forensic psychologists and 3 family lawyers), who were not participating in the study. These experts were asked to rate the clarity of the items on a scale of 1 to 4. In the same vein, if they rated any of the items with a low score, they were asked to report what problem they had encountered or, if they considered it appropriate, to recommend a specific rectification. The descriptive analysis showed that all the items included displayed a high degree of clarity (min = 3.8, max = 4, M = 3.97, SD = .066, 95% CI [3.952, 3.999]). In the next phase, the list of items was sent back to the sample of experts. There, participants were asked to indicate on a graduated scale from 1 to 10 the extent to which each item was required/important for the definition of “child victimization in the context of conflictual divorce.” As in the previous phase, in order not to lose information, a space was provided after each item so that the professionals, after making the judgment of importance, could make any comments or clarifications. In order to enrich the data derived from this study, we also decided to include, for each item, a frequency judgment. Experts were asked to evaluate how frequent it was for them to witness each of the proposed items (behaviors) during their professional practice. We took this approach to provide initial evidence on the frequency distribution of this potential type of victimization. Consensus Definition Development Given the lack of a universally recognized threshold to establish the consensus within a Delphi process, we decided to set a rather conservative a priori requirement. Similar to previous research (Campbell et al., 2021), to consider that an item was required for the definition of the concept, that item had to obtain a score of 7 (out of 10) or higher by at least 75% of the panelists. The respective descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and 95% confidence interval) were computed for each item (behavior). Results showed that all items, except item 3 (“One parent [or both parents] makes the child take on daily tasks inappropriate for his/her age, which were previously performed by the other parent”), received scores equal to or higher than the established threshold. As for the consensus, our results suggested that there was not enough agreement to include items 1 (“One parent [or both parents] presents him/herself as a victim to the child seeking his/her emotional support”), 3 (“One parent [or both parents] makes the child take on daily tasks inappropriate for his/her age, which were previously performed by the other parent”), 5 (“One parent [or both parents] conveys feelings of loneliness and/or sadness to the child when the child is with the other parent”), and 28 (“One parent [or both parents] frequently leaves the child in the care of a third party, even if the other parent is available and offers to care for the child”). The most frequent behaviors according to the experts’ criteria were those included in items 4 (“One parent [or both parents] uses the child as a confidant and/or counsellor regarding conflicts with the other parent”) and 11 (“One parent [or both parents] holds the child responsible for the breakup and/or relational problems between the parents”) while the least frequent behaviors were considered to be those included in items 9 (“One parent [or both parents] delegates inter-parental communications [claiming pensions, household goods or materials, etc.] to the child), 10 (“One parent [or both parents] uses the child to monitor/control the other parent”), and 17 (“One parent [or both parents] falsely accuses or denounces the other parent of causing harm to the child [abuse, mistreatment, neglect, etc.]). The complete distribution of importance, agreement and frequency scores are reported in Table 1. Item descriptions are detailed in Table 2. Table 1 Summary Statistics Describing Experts’ Ratings, Agreement and Behaviours’ Frequency (proportions)   Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation; LL = lower bound of the confidence interval; UL = upper bound of the confidence interval; proportion = proportion of between-expert agreement. Highlighted rows denote included items (behaviors). Items’ indices are matched with items descriptions reported in Table 2 (appendices). The aim of this study was to identify indicators of victimization in children involved in a conflictual divorce process. This is the first empirical study that has attempted to address the issue directly, collecting information from professionals who study and care for the impact on children in highly conflictual break-up situations. In general terms, professionals reached a high level of agreement in the great majority of the items (87.5%) derived from the victimizing parental behaviors they reported in the first round of the procedure based on their own experience. The high level of agreement reached in an interdisciplinary professional sample indicates that these forms of victimization of children do not go unnoticed by the different agents involved in these cases (lawyers, judges, forensic psychologists, prosecutors, etc.). These results might provide supporting and systematized empirical evidence for some of the negative phenomena observed in high-conflict divorce cases that have been repeatedly pointed out by various researchers (Camisasca et al., 2019; Fosco & Bray 2016; Grych et al., 2004; Saini et al., 2013). Our results show that the most prevalent inappropriate parental behaviours/attitudes could be the use of the child as a confidant and/or counsellor in relation to interparental conflict and the attribution of responsibility for the break-up or interparental problems to the child. The former is in line with what has been reported by authors such as Saini & Birnbaum (2007), who suggested that making the child the channel of interparental communication inappropriately in the context of high conflict might be one of the circumstances most frequently appreciated by professionals. The later might symbolize an especially harmful situation for children. Arguably, any attitude that leads the child to feel responsible for the situation generated can potentially be a highly distressing experience that is likely to have a significant impact on their emotional and relational spheres. Among the behaviors that were less frequently reported by professionals are possible false allegations of abuse, maltreatment, or neglect. This is in line with the findings of authors such as Saini et al. (2013), who reported that in investigations conducted by child protective services they found that malicious allegations were present in only 13% of cases. Although data indicates that this reality exists and it is undoubtedly a very harmful circumstance for children, it is not as prevalent as others in Spain. Note, however, that it has also been suggested that the prevalence of these behaviors could be around 29% of cases, which coincides with what has been described in the scientific literature regarding allegations of abuse, mistreatment, or neglect in the context of contentious divorce that are uncertain (González et al., 2012; Trocmé & Bala, 2005). Our data also suggest greater heterogeneity in the observed frequency of child victimization behaviors in the context of contentious divorce than in the agreement on their importance in defining the construct itself. This is relevant as it implies that the importance attributed to each behavior is likely not biased by the frequency with which it was observed. For example, the behaviors excluded by low agreement (items 1, 3, 5, and 28) show relatively high and higher frequencies than several items that have obtained higher agreement. Limitations The present study has several limitations that need to be taken into account. First, the results obtained are strictly limited to the Spanish context. Studies with other professionals from different cultural contexts are needed to corroborate these results. Secondly, the option of obtaining the list of indicators openly from the experts (without previously designing items derived from the scientific literature), although it offers obvious advantages – such as to collect aspects appreciated in common practice that have not been previously determined – may also mean that some specific aspects specified in the international scientific literature may not have been collected and that, therefore, there are other behaviors/attitudes harmful to children that are not covered in this study. Conclusion The present research offers a series of specific indicators, confirmed by the technical knowledge and experience of the participating experts. They provide valuable knowledge that can guide professionals in their daily assessments, facilitating the detection of parental behaviour/attitudes that constitute victimisation of children immersed in these highly conflictive divorce situations, and which, in turn, should facilitate the recommendation of judicial and/or therapeutic measures that can contribute to minimising their associated risks. Likewise, the specification of a list of specific parents’ behaviours and attitudes that are victimising should facilitate the design and application of psycho-educational measures that can contribute to the prevention of harm to children and serve as a basis for future research. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Arch, M., Garcia-Arch, J., & Pereda, N. (2024). Indicators of child victimization in high-conflict divorce: Interprofessional consensus based on a delphi panel. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 41-46. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a1 References |

Cite this article as: Arch, M., Garcia-Arch, J., & Pereda, N. (2024). Indicators of Child Victimization in High-conflict Divorce: Interprofessional Consensus Based on a Delphi Panel. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 41 - 46. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a1

Correspondence: march@ub.edu (M. Arch).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS