Space for Action and Mental Health of Women Survivors of Psychological Intimate Partner Violence

[El espacio para la acción y la salud mental en las mujeres supervivientes de violencia psicológica en la pareja]

Natalia Fernández-Álvarez1, María Y. Fontanil1, Joel Juarros-Basterretxea2, and María Á. Alcedo1

1University of Oviedo, Spain; 2University of Zaragoza, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a5

Received 18 November 2022, Accepted 3 December 2023

Abstract

No previous studies have explored how women’s autonomy (space for action) could mediate between psychological intimate partner violence (IPV) and mental health. This study explores this issue. Participants were 102 women recruited from specialized formal support services who answered self-reports about the target variables. Structural equation modeling was used to estimate the direct and indirect effects of IPV (verbal-emotional violence and domination-isolation) on current psychopathological symptomatology and satisfaction with life considering the mediator effect of space for action. Results indicate that both types of IPV had a direct negative effect on women’s space for action during the relationship. Domination-isolation predicted current space for action directly and positively, which in turn had a negative direct effect on psychopathological symptomatology and positive on satisfaction with life. Finally, both types of IPV showed indirect effects on psychopathology and satisfaction with life through space for action during the relationship and currently.

Resumen

En España ningún estudio ha explorado cómo podría mediar la autonomía (espacio para la acción) entre la violencia psicológica en la pareja y la salud mental. El trabajo ha analizado este tema reclutando en servicios de apoyo especializados a 102 mujeres que respondieron a autoinformes sobre las variables diana. Mediante ecuaciones estructurales se estimaron los efectos directos e indirectos de la violencia verbal-emocional y de dominación-aislamiento en la sintomatología psicopatológica actual y en la satisfacción con la vida, considerando como mediador el espacio para la acción. Ambos tipos de violencia psicológica tuvieron efecto directo negativo en el espacio para la acción durante la relación. La dominación-aislamiento predijo directa y positivamente el espacio para la acción actual, que tuvo un efecto directo negativo en la sintomatología y positivo en la satisfacción con la vida. Por último, ambos tipos de violencia mostraron efectos indirectos en la sintomatología y satisfacción con la vida mediados por el espacio para la acción durante la relación y en la actualidad.

Palabras clave

Violencia de género en la pareja, Violencia psicológica, Espacio para la acción, Satisfacción con la vida, Salud mental, Ecuaciones estructurales

Keywords

Intimate partner violence, Psychological violence, Space for action, Satisfaction with life, Mental health, Structural equation modeling

Cite this article as: Fernández-Álvarez, N., Fontanil, M. Y., Juarros-Basterretxea, J., & Alcedo, M. Á. (2024). Space for Action and Mental Health of Women Survivors of Psychological Intimate Partner Violence. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 57 - 66. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a5

Correspondence: fernandeznatalia@uniovi.es, psicoalvareznatalia@gmail.com (N. Fernández-Álvarez).

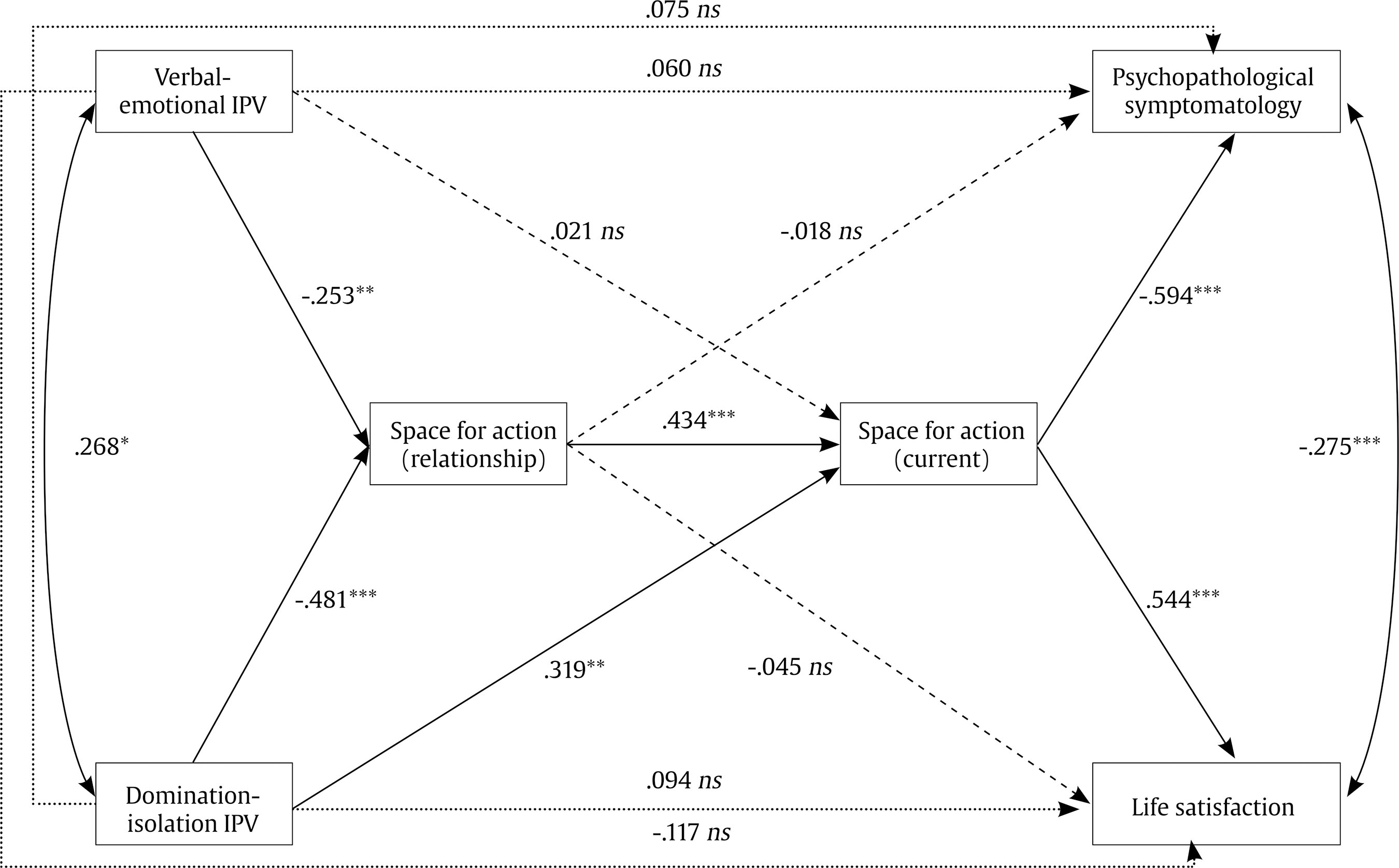

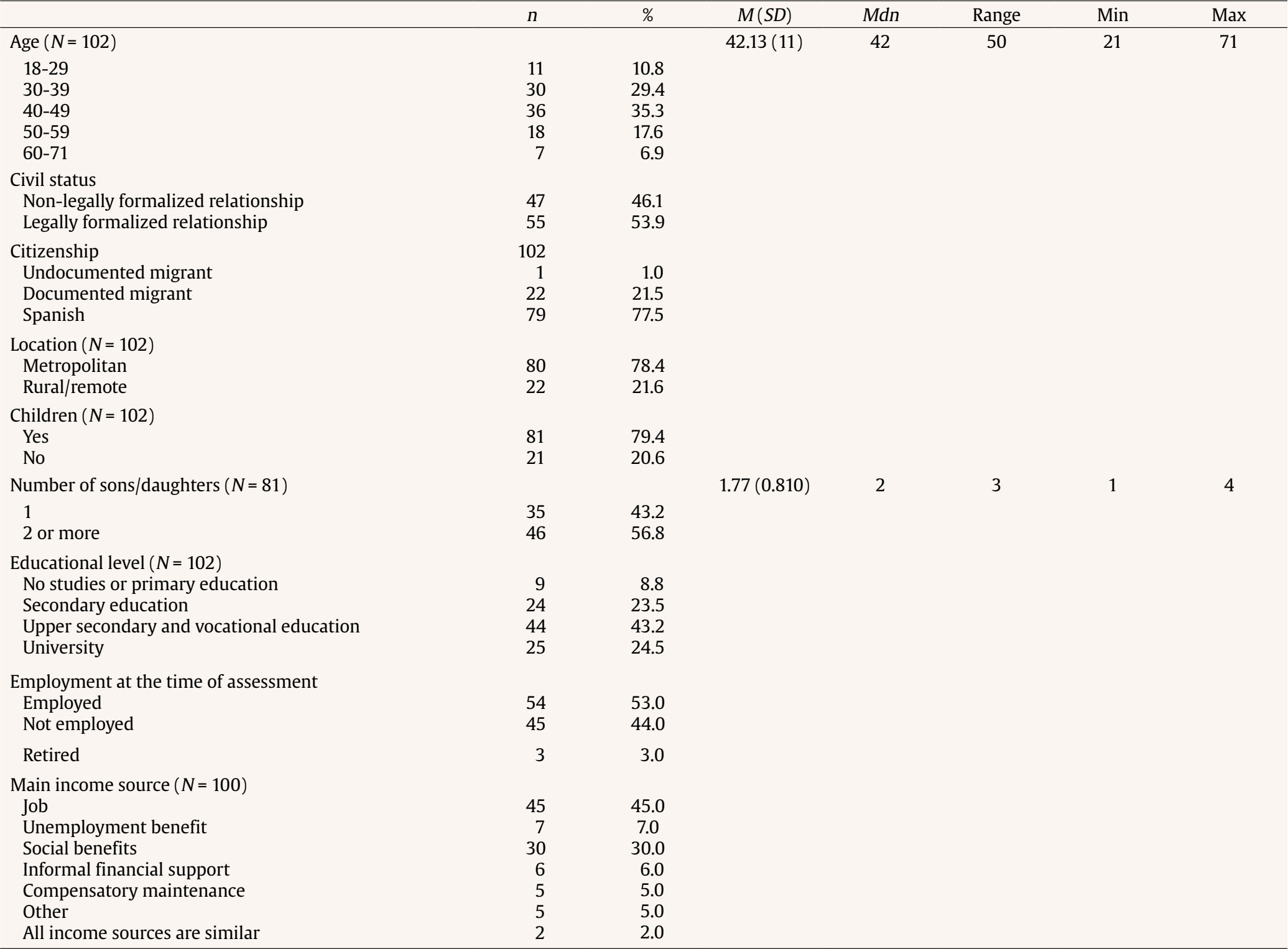

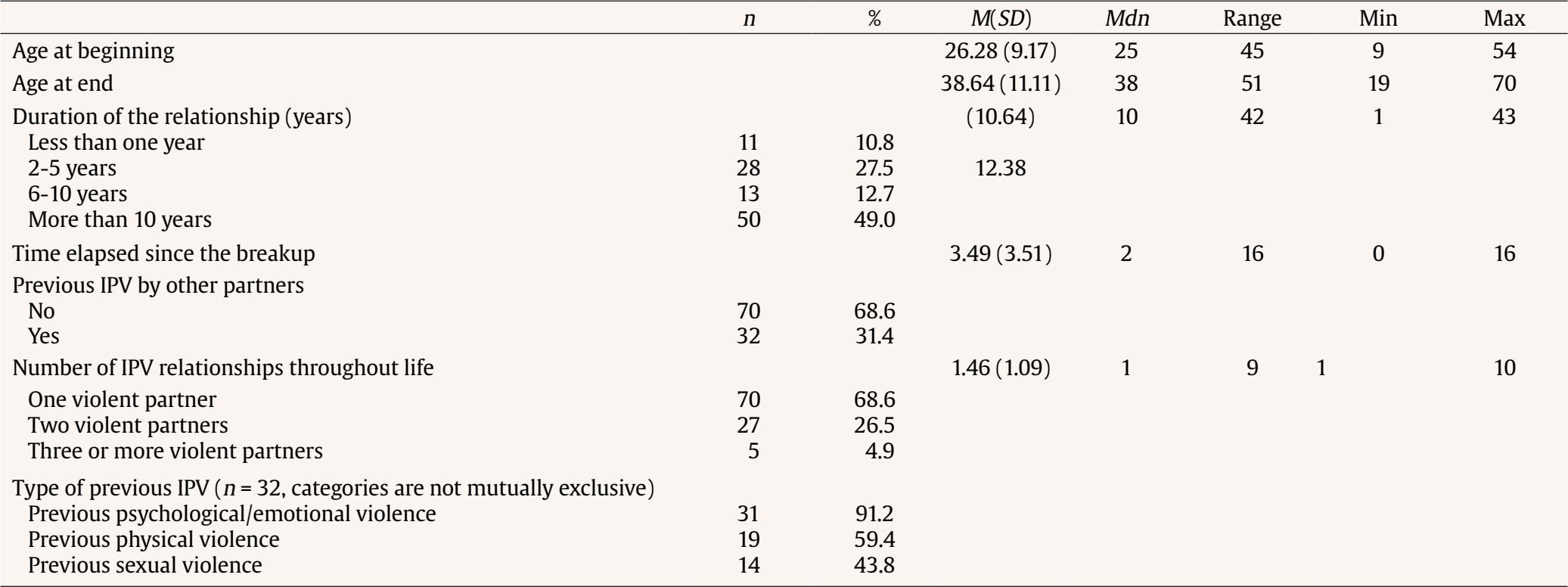

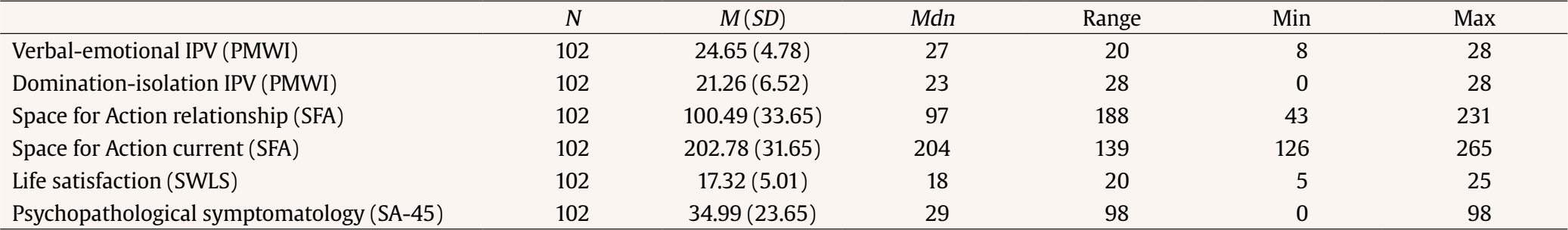

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a global public health problem that affects a high proportion of women around the world, undermining their physical, psychological, and social health and causing higher government-funded health costs (William et al., 2022; World Health Organization [WHO, 2021]). For a long time, research into IPV focused on physical violence due to the social normalization of other forms of maltreatment, such as psychological, emotional, or control violence, which also undermine women’s rights (Blasco-Ros et al., 2010; Dokkedahl et al., 2022; Fontanil et al. 2020; Mechanic et al., 2008; Moulding et al., 2020; Stark, 2007). The high prevalence rates of nonphysical violence support the urgent need for a response to this type of maltreatment. Data from the European Union (EU) survey on violence against women (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights [FRA, 2014]) showed that 43% of European women aged 15 years or more had experienced some form of psychologically abusive behavior, controlling behavior, economic violence, or blackmail. In Spain, a 2020 report found that 37.1% of women aged 15 years or more had suffered psychological control violence, 32.4% had experienced emotional violence, and 12% economic violence. In 72.7% of the cases the relationship continues after having reported IPV to the police, being the most common consequence the maintenance or worsening of IPV (Delegación del Gobierno contra la Violencia de Género [DGVG, 2020]). In Spain, from 2003 to date, 1,226 women have been murdered by their partner or former partner (DGVG, 2023; González et al., 2018). Psychological Maltreatment and Mental Health Women who have been subjected to IPV often report that psychological IPV is the worst experience of maltreatment (Dokkedahl et al., 2022; Mechanic et al., 2008; Moulding et al., 2020). The literature has explored in-depth the association between IPV and mental health, finding that psychological and emotional abuse are associated with a higher likelihood of reporting severe psychological problems, such as PTSD, anxiety, and depressive or psychosomatic symptoms (DGVG, 2020; Romito et al., 2022; Shuman et al., 2021; Stöckl & Penhale, 2015; Trevillion et al., 2012), which go above and beyond the impact of physical or sexual IPV (Lagdon et al., 2014; Nevala, 2017). In Spain, the macro-survey on violence against women shows that 74.7% of women over 15 who had experienced IPV from a former partner reported several psychological consequences, including low self-esteem, anxiety, despair, sleep or eating disturbances, and drug consumption (DGVG, 2020). More recent studies also find out that psychological IPV is associated with the presence of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress symptoms, as well as significant interferences in all aspects of the daily life (Cirici-Amell et al., 2023; Domenech del Rio & Sirvent-Garcia del Valle, 2017). Psychological IPV reduces self-efficacy and sense of control, causing deep distress and feelings of disempowerment that may hinder the process of leaving the violent relationship (Grillo et al., 2019; Perez et al., 2012; Webermann et al., 2022). This is all the more relevant considering that empowerment and self-efficacy are associated with resilience and psychological well-being in cases of IPV (Dutton & Kropp, 2000; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; Muñoz et al., 2017; Perez et al., 2012). Some research has suggested that psychological IPV complicates the process of leaving and recovering from the negative effects and psychological dysfunctions associated with the abuse (Blasco-Ros et al., 2010). Much research in the field of IPV has focused on the damage the violence causes to women’s health, with the inherent problem of conceptualizing women as passive victims that suffer pain or discomfort, and forgetting the active efforts women make to overcome. Women are not only ‘sufferers’ but also people that make decisions to thrive (Flasch et al., 2017). In contrast, feminist approaches consider women as active agents and recognize their ability to cope with IPV, survive, and protect their children (Gondolf & Fisher, 1988). Recent studies highlight the capacity of women to manage multiple resilience resources to overcome IPV and draw positive learnings from their experiences (Carney et al., 2022; D’Amore et al., 2021; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; Flasch et al., 2017; Fontanil et al., 2020; González-Méndez & Hamby, 2021). Studies have also shown that women experiencing IPV have an awareness of their poorer mental health and a willingness to approach health services for multiple kinds of assistance. In other words, although it is important to consider IPV as a phenomenon with a severe impact on women’s mental health, it is equally necessary to acknowledge women’s resilience in the face of this abuse (Anderson et al., 2012; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; Fontanil et al., 2022; Romito et al., 2022). It has been suggested that new theoretical perspectives with a wider view of the IPV phenomenon, such as ecological and feminist approaches, could be essential in guiding future research and effective policies designed to prevent IPV and support the recovery process (Carney et al., 2022; Farhall et al., 2020; González-Méndez & Hamby, 2021; Moulding et al., 2020; Myhill, 2017; Sharpless et al., 2022; United Nations, 1992). Ecological and Feminist Perspectives on IPV Feminist and ecological research has identified IPV as more of a systemic issue than an individual one. From this perspective, macrosystemic factors such as geographical, community, social, and ideological or cultural features are relevant variables in a comprehensive understanding of maltreatment (Dutton & Goodman, 2005; Fontanil et al., 2020; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2019; Moulding et al., 2020; Nevala, 2017). Feminist and gender perspectives explain IPV as a complex phenomenon in which multiple variables are involved. This constitutes a common point with the ecological model that considers human development as shaped by the interactions stablished between individuals and their multiple and interrelated ecological systems (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem). In this respect, the feminist perspective highlights that, to understand the IPV phenomenon, it is necessary to consider gender as a category for analysing the rest of explanatory variables of the differential men/women violent behaviour. That is to say that the wider context of power inequality between men and women along all the ecological levels and the unequal power relationships, generally unfavourable to women and socially and historically constructed, are those that make up the framework of IPV. Although at the genesis and/or maintenance of IPV other factors could be present, the social norms based on the gender that uphold male domination and female subordination are essential to perpetuate men’s violence against women. This inequality should be considered by researchers on the field since gender-blindness threatens the usefulness of science for providing knowledge to solve the problem of IPV (Delgado-Álvarez, 2020; Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2019). In the academic literature on IPV, the feminist and gender perspectives are present through different concepts, among which “coercive control theory” should be highlighted. This proposal differs from other research in this field in that the explanation of IPV dynamics focuses on the pattern of violence more than on the discrete episodes of explicit psychological, physical, or sexual aggression. In addition, from this point of view, IPV is considered a “liberty crime” since women’s freedom is constricted by men’s use of a variety of strategies for controlling, intimidating, and isolating women (Stark, 2007). Stark’s (2007) and other feminist proposals were nuanced by Johnson’s (2008) acceptance of the existence of different kinds of violence in the relationship apart from what feminist theories refer as IPV. In Johnson’s typology, “intimate terrorism” is the type of IPV that is rooted in the patriarchal model that validates men’s power, and consists of the use of violence and coercive control tactics, primarily by men against women, to take general control over the partner (Johnson, 2006, 2008; Johnson et al., 2014; Johnson & Leone, 2005). Some of the coercive controlling tactics are “structural forms of deprivation, exploitation, and command that compel obedience indirectly by monopolizing vital resources, dictating preferred choices, micro-regulating a partner’s behavior, limiting her options, and depriving her of supports needed to exercise independent judgment” (Stark, 2007, p. 229). The effectiveness of the control is explained by a woman’s behavior being continuously regulated by the batterer, which leads to a feeling of “entrapment” that diminishes her ability to find a way out of the violence. Yet it is also crucial to understand that control tactics are effective because they take place within the cultural context of gender inequality in heterosexual intimate partner relationships. The wider social context normalizes the control of the male partner over the female partner, so when the control starts, it is difficult for women to identify, recognize, and disclose the abuse (Fontanil et al., 2020; Fontes, 2015; Kirkwood, 1993; Patafio et al., 2022; Stark, 2007). Some recent studies carried out in Spain are focusing on issues related to psychological IPV, such as the potential of non-physical behavior in predicting the risk of feminicide (López-Ossorio et al., 2021) or the profiles of non-violent or antisocial aggressors (González-Álvarez et al., 2022). Despite this, classically, psychological IPV has received less research attention than physical IPV, so there is much scope to explore its influence on women’s well-being, specifically on their mental health and their “space for action”. Space for Action: The Other Side of Psychological IPV The limitation of women’s volition and autonomy is an under-researched consequence of psychological IPV, despite it being frequently experienced by women who have been subjected to abuse (Kelly et al., 2014; Moulding et al., 2020). However, as part of their diverse and active coping behaviors to overcome maltreatment (Carney et al., 2022; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; Fontanil et al., 2020; Gondolf & Fisher, 1988; González-Méndez & Hamby, 2021), women also fight to keep a portion of their agency and identity in “safety zones” where they feel autonomous and secure, by building or maintaining other relationships or by keeping personal and meaningful objects, for example. As a response to women’s self-care, independent behaviors, and ability to keep safety zones, abusive male partners usually increase their use of violence (Stark, 2007). Kelly (2003) used the term “space for action” to refer to women’s autonomy and agency, which tends to decrease in a process of behavioral, cognitive, and emotional adaptation to avoid and survive the abuse. In other words, space for action are women’s capacities to think and act from their own perspectives and be independent across different areas such as motherhood, sense of self, community, friends and family, help-seeking, competence, well-being and safety, and finances (Kelly et al., 2014). There have been few studies—and none in the Spanish context—that empirically explore the association between psychological IPV and women’s space for action in the individual, social, economic, and community spheres, although existing studies point out that the greater the violence suffered by women, the lower their space for action during the relationship (Kelly et al., 2014; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Kelly et al. (2014) recruited a sample of 100 sociodemographic diverse women who had accessed IPV services and followed them for 3 years taking measures at four different waves. The study was multi-method and employed scales and questionnaires, interviews, exercises, life history calendars, focus groups, artwork, and photographs. The objective was to identify the factors that support or block long-term women’s settlement, as well as how community resources could facilitate the expansion of women’s space for action. The authors showed that space for action was significantly lower when women were suffering violence and expanded immediately after leaving the perpetrator. After the breakup, women’s lives became constrained by structural barriers such as difficulty for accessing resources to rebuild their lives, victim blame, delay, misinformation, and scrutiny of social services. During the 3 years, multiple variables enabled or hindered this non-linear, gradual, and slow process. In the study of Sharp-Jeffs et al. (2018), associations between coercive control and space for action were explored to test whether ending violence resulted in significantly expanded space for action. This study confirmed that space for action increases after the separation and that dealing with IPV is not a linear process that also depends on external conditions, and concluded that supports need to extend beyond the breakup. Several studies also show that the negative impact of violence is not limited to the time when women are in a violent relationship; even after the relationship has ended, physical, psychological, and social consequences are still present and new difficulties appear (Fontanil et al., 2020; DGVG, 2020). In the post-separation phase, control disappears or decreases, and although space for action increases, it remains constrained to some extent by structural barriers that block women’s access to resources for an independent and secure life. To put it another way, in the post-separation phase, batterer-generated risks give way to life-generated risks (Farhall et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2014; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Restoring control to the survivor and giving them the chance to regulate their own life is therefore key in the process of overcoming IPV trauma (Doyle et al., 2022; Herman, 1992). Several models for treating IPV sequelae promote empowerment and have obtained improvements in mental health as well as decrements in IPV (Iverson et al., 2022; Johnson et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2020; Karakurt et al., 2022; Kulkarni, 2019). Recent studies have also indicated that a sense of control stands out as a key individual resilience resource for women who have experienced IPV (Crann & Barata, 2016; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; Katerndahl et al., 2019; López-Fuentes & Calvete, 2015). Researchers and professionals must move beyond conceptualizations of women as passive victims and start to think in terms of women’s freedom and agency (Carney et al., 2022; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; González-Méndez & Hamby, 2021). Therefore, for a better understanding of the recovery process for women IPV survivors, there is a need for an in-depth exploration of space for action from a feminist and women’s emancipation perspective. Studies have shown that IPV has a deleterious impact on women’s health and space for action, as well as the fact that women’s autonomy increases after leaving the violent relationship. However, no previous studies have analyzed the potential mediator role of space for action on women’s well-being. Given the absence of studies addressing this topic, especially in the Spanish context, the aim of the present exploratory study is to estimate the direct and indirect effects of psychological IPV during the relationship on current psychopathological symptomatology and life satisfaction considering the mediator effect of space for action during the abusive relationship and current space for action. It is hypothesized that higher psychological IPV will be associated with less space for action during the relationship and, in turn, less current space for action. Lower levels of current space for action will be associated with more psychopathological symptomatology and less satisfaction with life. The study design was retrospective and cross-sectional. Participants, procedure, measures, and statistical analysis are described below. Participants A nonrandom convenience sample of 102 women was recruited between September 2020 and January 2022. Women were included if they (a) were at least 18 years old, (b) spoke and understood Spanish, (c) had experienced IPV, (d) were no longer in the relationship and did not cohabit with the aggressor, and (e) had sought help from at least one formal resource (social services, police or legal services, health services). The final sample is described in Table 1. The financial hardship faced by most of the participants is evident. A high percentage of the women were unemployed at the time of assessment (47%) and depended primarily on social benefits to sustain themselves and their dependents (79.4% of the participants had children). In general, the monthly household income per person was low (M = €479.60), and 33.4% of the women had a monthly income below €276. Note that the minimum vital income in Spain is €734.99 for a cohabitation unit integrated by an adult and a minor or two adults, and €904.60 for an adult and two minors, two adults and a minor or three adults. Further, 29.4% of participants considered that their monthly income was not enough to live on, and 51.9% said that they struggled to make ends meet or that they could not afford any whim. Only 18.5% reported having enough or fairly good money to live on. Finally, 56.9% of participants were living in their own home or in a borrowed property, but 14.7% of the women were still living in the property that they co-owned with (or that was owned exclusively by) the abuser, and 28.4% were living in a shelter or with family, friends, or other people. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the IPV experienced by participants. A large proportion of the women in the sample had been psychologically, physically, or sexually victimized by at least one previous partner (31.4%). In addition, 61.7% of participants had stayed in the relationship for 6 or more years. Procedure The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias (CEImPA 2021.246) and the Committee of the University of Oviedo 2_RRI_21). The Asturian Women’s Institute was contacted to obtain consent for access to various women’s services and request collaboration in the process of sample recruitment. Staff from the Asturian shelters net, women’s advisory centers, and the psychosocial care program of the Public Health Service were contacted to introduce the study. The centers invited service users to participate and requested permission to share their contact information with the researchers. One of the researchers phoned each woman to present the study aims, procedures, implications, participants’ rights, and researchers’ duties. On the same call, the researcher clarified any queries with the woman, and they both arranged a date for the assessment interview. Upon receipt of the informed consent, the interview was then conducted face-to-face, by video call, or by phone call, depending on the woman’s preference and the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Of the women who met the inclusion criteria and were contacted by the researchers, 85% agreed to take part in the study, 4.17% did not agree, and 10.83% either changed their minds after arranging the date or were unable to complete the assessment process. The assessment generally required one or two sessions per participant and lasted three hours on average. The procedure was carried out in compliance with the Nuremberg Code, respecting the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence, and prioritizing participants’ well-being at all times. As specified by the Helsinki Declaration, and the Standards of the American Psychological Association, women took part in the study in an informed and voluntary way. In addition, data confidentiality was strictly respected, in accordance with Spanish and European legislation. Measures During the assessment process, a number of instruments were applied. Psychological Maltreatment of Women Inventory-Short Form (PMWI-SF; Tolman, 1999) This 14-item instrument uses a 5-point Likert response scale (0 = never to 4 = always) to assess psychologically abusive actions experienced by a woman during the final year of the relationship. In addition to the total psychological violence score, it is possible to obtain a score for each of the two subscales: verbal-emotional abuse and domination-isolation. The original validation study demonstrated good reliability values (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .87 to .92), adequate convergent and discriminant validity, and capacity to discriminate between women who had experienced psychological violence, women in a bad relationship, and the control group. The Spanish version has also shown good convergent validity and adequate capacity for detecting psychological IPV (García-Esteve et al., 2011). For our study, Cronbach’s alpha was .78 for the global scale, .78 for the verbal-emotional subscale, and .77 for the domination-isolation subscale. Symptom Assessment-45 Questionnaire (SA-45; Davison et al., 1997) This instrument has 45 items rated on a 5-point Likert response scale (0 = not at all to 4 = a lot or extremely) to assess the presence and degree of psychopathological dysfunctions during the previous week. It provides a total scale score and individual scores for each of the subscales: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. For our study, we used the Spanish validated version of the questionnaire (Sandín et al., 2008), and only the overall score—the Global Severity Index (GSI)—was considered. The Spanish version of the SA-45 has shown good internal consistency (Cronbach’s a = .95), as well as adequate convergent and discriminant validity. For the present study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .92 was obtained. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) This scale has five items rated using a 5-point Likert response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to assess participants’ current overall satisfaction with their life. The instrument has shown good internal consistency and reliability, with Cronbach’s alphas ranging from .79 to .89 (Pavot & Diener, 1993), as well as good convergent and discriminant validity (Diener et al., 1985). For the Spanish validation, Atienza et al. (2000) found a Cronbach’s alpha of .84, good item-test correlations, and convergent validity. In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .76. Space for Action Scale (SFA; Kelly et al., 2014; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018) This 39-item instrument uses a 7-point Likert response scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree) to measure the extent to which women’s lives are constrained in such domains as motherhood, sense of self, community, friends and family, help-seeking, competence, well-being and safety, and finances. High scores indicate that women feel freer to decide what to do in their lives. The SFA scale was drew on the nested ecological model of IPV by Dutton et al. (2006) and the domains across which they proposed that power and control can be exerted: individual, social, economic, and community domains. To measure different aspects of women’s autonomy for each of the SFA domains, the authors built statements based on previous assessment instruments focused on self-esteem, psychological abuse, general functioning and service utilization, and health status and quality of life. The original authors obtained an internal consistency ranging from .87 to .95 for the overall scale and adequate internal consistency with little variations over time for the subscales (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). For the present study, the scale was adapted to Spanish using a forward translation and, to account for cultural differences, items were adjusted to the Spanish context as required (International Test Commission, 2017). In our case, the scale was employed to explore participants’ space for action at two different points in time: during the violent relationship (former space for action) and at the time of assessment (current space for action). In our sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was .93 when applied to the period of abuse and .95 when applied to the current time. The “elapsed time since the end of the relationship” was registered by asking the participants “when the relationship finished” and then it was included as a covariable in the analysis. Statistical Analysis Descriptive statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS version 26 to profile the sociodemographic and IPV characteristics of the sample (Table 1, Table 2), and women’s scores in the main variables of the study (Table 3). Structural equation modeling was used to estimate the direct and indirect effects of verbal-emotional abuse and domination-isolation during the relationship on current psychopathological symptomatology and life satisfaction through the space for action during the relationship and current space for action. Three specific indirect effects were estimated: the indirect effect through former space for action (specific indirect effect 1), the indirect effect through current space for action (specific indirect effect 2), and the indirect effect through former and current space for action (specific indirect effect 3). Considering that the period of time between the end of the violent relationship (victimization) and the assessment varied across different cases, it was included in the model as covariable to control the potential effect of the time passed between them. To achieve the research aim of this study, a fully saturated model was estimated. Saturated models do not have degrees of freedom, and thus the fit of the model to the data cannot be estimated (it is artificially perfect). The purpose of the fully saturated models is not to test the appropriateness or the fit of the model to the data but to estimate all the potential relations between the model variables simultaneously. Mplus version 8.7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2021) was used to estimate the model. Descriptive statistical analysis of the main variables is summarized in Table 3. Women in the sample experienced high severity of psychological IPV during the last year of the relationship, being verbal-emotional slightly higher (M = 24.65, SD = 4.78) than domination-isolation (M = 21.26, SD = 6.52). Current space for action is higher (M = 202.78, SD = 31.65) than the women’s space for action during the relationship (M = 100.49, SD = 33.65) and life satisfaction is good (M = 17.32, SD = 5.01). Finally, the presence of current psychopathology is low (M = 34.99, SD = 23.65). The results of the model are displayed in Figure 1. As shown, the direct effects of verbal-emotional IPV and domination-isolation IPV on current psychopathological symptomatology (ß = .297, p = .291; ß = .272, p = .370 respectively) and on life satisfaction (ß = -.123, p = .218; ß = .073, p = .362 respectively) were not statistically significant. Nevertheless, other direct effects are present in the model: both types of victimization (verbal-emotional and domination-isolation) showed statistically significant negative direct effects on space for action during the violent relationship (ß = -.253, p = .01; ß = -.481, p = .001 respectively), which in turn directly predicted current space for action (ß = .434, p = .001). Domination-isolation IPV directly and positively predicted current space for action (ß = .319, p = .01), whereas verbal-emotional IPV had no statistically significant effect (ß = .021, p = .827). Current space for action showed a statistically significant direct negative effect on psychopathological symptomatology (ß = -.594, p = .001) and a positive effect on life satisfaction (ß = .544, p = .001). Figure 1 Structural Equation Model for the Analyzed Variables   Note. The covariable of time between victimization and assessment was omitted in the model to simplify it and facilitate the understanding. The covariable only had statistically significant effect on life satisfaction (ß = -.122, p = .047). ns = non (statistically) significant. *p = .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Regarding the specific indirect effects through former space for action (specific indirect effect 1), neither verbal-emotional IPV nor domination-isolation IPV showed a statistically significant indirect effect on psychopathological symptomatology (ß = .005, p = .831; ß = .009, p = .827 respectively) or on life satisfaction (ß = .011, p = .709; ß = .022, p = .696 respectively). In summary, when current space for action is not considered and only space for action during the violent relationship is taken into account, higher or lower levels of verbal-emotional or domination-isolation IPV did not predict lower or higher levels of psychopathological symptoms or satisfaction with life. The results regarding the specific indirect effects through current space for action (specific indirect effect 2) were mixed: in verbal-emotional IPV there was no statistically significant indirect effect on psychopathological symptomatology (ß = -.012, p = .827), but domination-isolation IPV showed a statistically significant negative effect on psychopathological symptomatology (ß = -.189, p = .01). To summarize, when the effect of former space for action is not considered, different levels of verbal-emotional IPV did not predict different scores in psychopathological symptoms or in satisfaction with life. In contrast, it was found that higher levels of domination-isolation IPV predicted more current space for action, which in turn predicted lower psychopathological symptoms and higher satisfaction with life. Finally, there were statistically significant indirect effects via space for action during the relationship and current space for action (specific indirect effect 3). Both verbal-emotional IPV and domination-isolation IPV showed statistically significant indirect positive effects on current psychopathological symptomatology (ß = .065, p = .05; ß = .124, p = .001 respectively) and statistically significant indirect negative effects on life satisfaction (ß = -.060, p = .05; ß = .114, p = .001 respectively) via former and current space for action. The aim of the present exploratory study was to estimate the direct and indirect effects of verbal-emotional and domination-isolation IPV during the relationship on current psychopathological symptomatology and life satisfaction through space for action during the abusive relationship and current space for action. The study was carried out with a sample of women who had experienced IPV, had ended the relationship, and had sought help from at least one formal resource (social services, police or legal services, health services). Our results shed some light on the mechanisms through which psychological IPV damages women’s mental health and satisfaction with life. While there is a considerable body of research focusing on the health impact of physical IPV, less attention has been paid to the deleterious health impact of psychological IPV (Dokkedahl et al., 2022). Some studies on this issue have found a significant association between IPV and a worse mental health status (Blasco-Ros et al., 2010; Cirici-Amell et al., 2023; Domenech del Rio & Sirvent-Garcia del Valle, 2017; DGVG, 2020; Lagdon et al., 2014; Mechanic et al., 2008; Nevala, 2017; Romito et al., 2022; Shuman et al., 2021; Stöckl & Penhale, 2015; Trevillion et al., 2012). However, to date, few studies have sought to clarify the mechanisms that explain the interaction between violence and health outcomes, subjective well-being and resilience, especially in relation to the role played by women’s independence-related variables, such as empowerment (Perez et al., 2012), autonomy in household-decision making (Mavisakalyan & Rammohan, 2021), or agency promoted by state-level restorative justice policies (Sharpless et al., 2022). Recent studies have shown that spheres of women’s lives that are usually repressed by the abusive partner, such as having a sense of purpose and projects, freedom for building and maintaining interpersonal relationships, and access to work and hobbies, among others, are connected to women’s well-being (Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; González-Méndez & Hamby, 2021). Our study found that the restriction of women’s space for action is an important mediator variable and so is a relevant concept for understanding the recovery process. According to our results, poorer mental health directly predicted lower satisfaction with life among our participants and vice versa. This is an expected result that highlights the need for public health services to guarantee adequate mental health support to enhance women’s quality of life (Doyle et al., 2022; Fontanil et al., 2020; Grillo et al., 2019; Mechanic et al., 2008). Participants of the present study showed quite good psychological health status and life satisfaction. It should be highlighted that women were recruited from formal support services and, on average, more than 3 years had passed since breakup, so women’s recovery process may have been quite advanced in general, what is also evidenced by the great increase in their space for action. Consistent with previous research (Kelly et al., 2014; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018), our study has found that both types of psychological IPV (verbal-emotional and domination-isolation) predict lower levels of space for action during the relationship, with domination-isolation violence having the strongest effect. This is one of our study’s main findings, highlighting the damage that psychological IPV causes to women’s mental health and citizenship rights. The finding is in line with researchers’ growing awareness about the destructive impact of psychological IPV and coercive control on women’s health (Cirici-Amell et al., 2023; Fontes, 2015; DGVG, 2020; Lagdon et al., 2014; Romito et al., 2022; Stark, 2007; Webermann et al., 2022). Domination-isolation violence in particular has a direct effect not only on space for action during the relationship but also after it has ended. Previous work analyzing the relationship between coercive control violence, post-separation violence, and the recovery process has noted that IPV impacts women’s independence even after they have left the violent relationship. Our findings add to this knowledge by suggesting that women who experience more domination-isolation IPV during the relationship have more current space for action (specific indirect effect 2). Considering the results from Kelly et al. (2014) and Sharp-Jeffs et al. (2018), this is a surprising result, but there are some plausible explanations that should be explored through further research. On the one hand, there is a cognitive hypothesis based on the phenomenon of “contrast effect”: it could be that women have a more acute perception of—and place greater value on—their current space for action after a relationship characterized by domination-isolation IPV has ended. In other words, due to the huge contrast between their volitional space during the relationship and their volitional space after the relationship, women have more capacity to develop in areas of autonomy. On the other hand, our results could be the consequence of the therapeutic intervention received by each woman. Psychological psychotherapy for women IPV survivors has a series of transversal components, some of which are emphasized more than others (Doyle et al., 2022; Grillo et al., 2019). It might be that women who had been in a more dominating or isolating relationship learned with more intensity during the therapy to detect the controlling behaviors of their partner. As a result, they would have been more conscious of how limited their former space for action was and they would then have been more aware of their current space for action. Future studies should aim to clarify how and why higher domination-isolation IPV predicts higher current space for action. It would also be useful to control for the effect of other variables, such as resilience, help-seeking behavior, coping style, formal and informal support, and post-separation abuse. Previous jobs did not find strong statistically significant associations between sociodemographic characteristics, such as age, and women’s global space for action (Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Further research could deeply explore how specific sociodemographic characteristics taken together could configure a factor of violation of women’s civil rights that, in turn, would affect their space for action, apart from the IPV suffered. Economic level, migrant status, and the presence of children could be vulnerability factors in the face of the abuser’s control strategies. Even after the breakup, former partners often continue to control and abuse women (Crossman et al., 2016). Another important finding is that neither of the assessed forms of IPV (verbal-emotional and domination-isolation) directly predicted global psychopathology dysfunction or satisfaction with life. This contradicts what was expected based on findings from previous research (DGVG, 2020; WHO, 2021), and it also highlights the relevance of mediator variables, such as space for action. In fact, both verbal-emotional and domination-isolation IPV indirectly predicted women’s overall mental health and satisfaction with life. This relationship was mediated by the space for action that women had while they were in the violent relationship and after they broke up. Thus, according to indirect effect 3, higher levels of past psychological IPV predicted statistically significant lower space for action during the violent relationship. Lower space for action during the violent relationship in turn predicted lower current space for action, and these lower levels of current space for action predicted worse current mental health and satisfaction with life. The opposite was also true: lower levels of psychological IPV predicted greater space for action during the relationship, which in turn predicted more current space for action and, finally, lower psychopathological symptomatology and greater satisfaction with life. These findings lead to the main conclusion of our study: as suggested by earlier research, in the post-violence recovery phase there are a number of variables that play a substantial role in women’s well-being (Kelly et al., 2014; Sharp-Jeffs et al., 2018). Independence-related variables, such as self-efficacy or sense of control, are essential in the recovery process, which to a large extent depends on the achievement of a state of emancipation that must be promoted by public policies and health practices (Doyle et al., 2022; Fernández-Álvarez et al., 2022; Fontanil et al., 2022; Herman, 1992; Iverson et al., 2022; Perez et al., 2012; Sharpless et al., 2022). Finally, in accordance with previous research, we found that greater current space for action was connected to better psychological health and satisfaction with life (Kelly et al., 2014). Research has amply proven the importance of autonomy and agency for women’s well-being, especially in the post-separation phase. Our contribution provides further confirmation that should make society think about the need for interventions on multiple ecosystemic levels to enhance women’s mental health after they have left a violent partner. Summarizing, space for action seems to play a role in the recovery process of women survivors of IPV since it is associated with lower psychopathological symptomatology and higher life satisfaction. In terms of applicability, this conclusion supports policies focused on women’s independence and autonomy. In the field of mental health, for example, therapeutic interventions oriented to women’s empowerment though the improvement of self-care, self-esteem, self-efficacy, assertiveness, decision making, and conflict resolution skills, the search for their own projects and goals and, especially, psychoeducation about violent dynamics and gender influence in IPV. The rights and supports recognized to women victims of IPV by the Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe, 2011) and the Spanish Organic Law 1/2004, of December 28, on Comprehensive Protection Measures against Gender Violence (Ley Orgánica 1/2004) must be put in practice. Women should have access to secure housing, feeding, employment adjusted to their idiosyncrasy, and training opportunities. Protection should be real for women and their children, especially in the period immediately after the breakup, because it allows them to participate in the community and be socially included. Since the recovery process is non-linear, slow, and gradual, women who have suffered any kind of IPV (psychological, physical, and/or sexual) need long-term support for rebuilding their lives (Kelly et al., 2014). Limitations Findings from the current study must be interpreted in the context of the limitations of our research. First, we used convenience sampling to recruit women who had sought and received support from formal services. This form of sampling implies less representativeness, although it is important to note that women IPV survivors are a hard-to-access population and similar studies usually have a small size sample with respect to the target population (e.g., Cirici-Amell et al., 2023). A bigger sample size could allow to explore more complex structural equation models and include new variables and covariables in the analysis. Having access to other women’s profiles could be insightful for exploring the recovery process in women who did not seek help from formal sources, since their coping strategies and sociodemographic and psychosocial conditions may differ. Second, the retrospective nature of the assessment means that participants could have been affected by bias associated with memory functioning. Future longitudinal research should address this issue by applying instruments that relate to the present at different timepoints. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could also offer a more in-depth exploration of the recovery process, detecting the main variables influencing achievements at each stage. Finally, given the novelty of the topic, the Spanish version of the SFA scale is not validated yet, which is a limitation that should be solved for future studies. Strengths To our knowledge, this is the first study about space for action in women IPV survivors to have been carried out in Spain. The literature has shown that the process of overcoming violence goes beyond the legal or physical separation from the abuser. It has also pointed out the importance of supporting women to recover their power and control. Therefore, there is a need for deeper insight into how women become empowered in different areas of their lives after IPV. Our study is the first step in this direction. Research into IPV has historically focused on a victim conceptualization of women, ignoring their resilience to cope with their situation. Our holistic and ecological perspective considers not only the negative post-traumatic changes but also the positive ones, such as the increase in control over their lives and the enhancement of satisfaction with life after leaving the violent relationship. Further, the theoretical perspective of the study describes IPV as a continuum phenomenon affecting women’s behavior, decisions, and opportunities, not only when an episode of explicit aggression occurs but also after the violent relationship has ended. Directing attention to psychological violence sheds light on types of abuse that have been normalized and ignored for a long time. In addition, the systemic theory is incorporated into our study through the assessment of women’s conditions at the microsystemic level (psychopathological dysfunctions) and through the mesosystemic and macrosystemic issues related to the constraints IPV imposes on women’s human rights (space for action). The focus on psychological violence and women’s strengths, and the analysis of what happens once the relationship has ended, is a complete approximation of women’s experiences, which could guide effective policies and professional practices to better support the recovery and emancipatory process of IPV survivors. Conclusions This study makes a significant contribution to the body of literature on psychological IPV by exploring women’s circumstances in the post-violence phase, with particular attention paid to the process of recovering autonomy and agency (known as space for action). Our results support the need to place psychological IPV at the center of the gender violence debate. If society wants to prevent the damage caused by IPV, it is crucial to remember that psychological abuse negatively impacts women’s democratic citizenship. Tertiary prevention must be complemented by primary prevention policies aimed at blocking any contextual attempts to normalize, justify, or minimize psychological IPV. Society must work to prevent this global public health problem which is an attack on women’s human rights, and ensure that survivors have access to resources that enhance their space for action and their social inclusion. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Fernández-Álvarez, N., Fontanil, M. Y., Juarros-Basterretxea, J., & Alcedo, M. A. (2024). Space for action and mental health of women survivors of psychological intimate partner violence Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 57-66. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a5 Funding: This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities (FPU scholarship19/00441). References |

Cite this article as: Fernández-Álvarez, N., Fontanil, M. Y., Juarros-Basterretxea, J., & Alcedo, M. Á. (2024). Space for Action and Mental Health of Women Survivors of Psychological Intimate Partner Violence. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 34, 57 - 66. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2024a5

Correspondence: fernandeznatalia@uniovi.es, psicoalvareznatalia@gmail.com (N. Fernández-Álvarez).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS