Dating Violence and Gender Beliefs Legitimizing Dating Violence among Cape Verdean University Students

Secci├│n monogr├ífica "Violencia de g├ęnero"/Monographic section "Gender violence"

[La violencia en el noviazgo y las creencias vinculadas al género que la legitiman en alumnos universitarios caboverdianos]

Sofia Neves1, Janete Borges2, 3, & Arimery Antunes1

1University of Maia, Portugal; 2University of Coimbra, Portugal; 3Polytechnic of Porto, Portugal

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a14

Received 1 July 2024, Accepted 3 March 2025

Abstract

The present study analyses the association between victimization and perpetration of dating violence and gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence among Cape Verdean university students. The sample consisted of 301 Cape Verdean university students, 220 female (73.1%) and 80 male (26.6%), with an average age of 23.86 years old (SD = 6.112). An online survey with sociodemographic characterization, the Inventory of Gender Beliefs, and the Inventory of Violent Juvenile Relationships were completed by each participant. Findings reveal high levels of dating violence, with 61.1% (n = 184) and 46.8% (n = 141) of students admitting having been exposed to or perpetrated, respectively, at least one act of violence. Female participants showed higher rates of victimization when compared to male participants, while males presented a higher level of beliefs legitimizing dating violence when compared to females. Education policy recommendations for dating violence prevention and combat are provided.

Resumen

Este estudio analiza la asociación entre victimización y perpetración de la violencia de género y las creencias sobre el género que legitiman la violencia en el noviazgo en alumnos universitarios caboverdianos. Se contó con una muestra de 301 estudiantes, de los cuales 220 (73.1%) eran mujeres y 80 varones (26.6%), con una media de edad de 23.86 (DT = 6.112). Cada participante cumplimentó una encuesta por internet con caracterización sociodemográfica, el Inventario de Creencias sobre el Género y el Inventario de Relaciones Juveniles Violentas. Los resultados muestran una gran violencia en el noviazgo, en el que el 61.1% (n = 184) y el 46% (n = 141) admiten que había sido expuesto al menos a un episodio de violencia o lo había perpetrado, respectivamente. Las mujeres presentaban un mayor porcentaje de victimización, en comparación con los participantes masculinos, mientras que estos presentaban mayores creencias que ligitimaban la violencia en el noviazgo en comparación con las mujeres. Se hacen recomendaciones sobre medidas para prevenir y combatir este fenómeno.

Palabras clave

Violencia en el noviazgo, Género, Creencias, Cabo Verde, Estudiantes universitarios

Keywords

Dating violence, Gender, Beliefs, Cape Verde, University students

Cite this article as: Neves, S., Borges, J., & Antunes, A. (2026). Dating Violence and Gender Beliefs Legitimizing Dating Violence among Cape Verdean University Students. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 36, Article e260467. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a14

Este artículo forma parte de la sección monográfica "Violencia de género". Correspondence: asneves@umaia.pt (S. Neves).

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pervasive problem in Cape Verde, affecting victims of different ages and educational levels. In order to explain the high rates of victimization, especially towards females, it is necessary to understand that Cape Verde is rooted in traditional values concerning gender-social relations, particularly regarding family and intimate issues (Carter & Aulette, 2009; Thomas, 2018). As Challinor (2017) pointed out, traditional gender ideologies were developed throughout a nation’s history of colonialism and migration, which defines women’s and men’s places in social organization. As a Portuguese former colony, Cape Verde is still characterized by the patriarchal system left by the Portuguese legacy, highly influenced by the moral values imposed by the Catholic Church (I. F. P. B. Rodrigues & Sheldon, 2010) and by the core assumptions of the dictatorship that lasted almost fifty years. Thus, the regime established in Portugal between 1933 and 1974, known as Estado Novo [New State], fostered not only colonial racism but also colonial sexism, both conceived as mechanisms of oppression (E. F. Monteiro, 2016). However, in the last decades, due to democracy instauration and changes in migration patterns, several social, political, and economic transformations favored the global development of the country and stimulating women’s emancipation, contributing to their academic and professional growth (Challinor, 2012). In fact, since its independence from Portugal in 1975, Cape Verde has improved its social and economic conditions, with the state recognizing equal participation of women in all domains (UN Women, 2018). In 2021, Cape Verde’s┬áHuman Development Index value was┬á.662, placing the country in the┬ámedium┬áhuman development category (position 128┬áout of┬á191 countries and territories) (UNDP, 2022). Concerning the Gender Inequality Index, in the same year, Cape Verde┬áhad a value of┬á.349 (position┬á84┬áout of┬á170┬ácountries) (UNDP, 2022). The rate of juvenile alphabetization (15 to 24 years old) is almost 100% for boys and girls, with girls showing a higher presence in universities in the last years (INE, ICIEG & ONU Mulheres, 2017). As argued by J. Monteiro (2018) and Borges (2019), although democracy has risen recently, social inequality still impacts the most vulnerable groups, such as youth, women, and the urban poor. The male population still represents the majority of active and employed people, and unemployment affects particularly young females, corresponding females to 53% of the poor (United Nations Cape Verde, 2022). Cape Verdean girls and women are also disproportionally affected by gender-based violence, as explored in the next section. Gender-based Violence in Cape Verde Gender-based violence is a result of power imbalances, reflecting political, social, and cultural elements of patriarchal structures (Fortes, 2015; Lobo, 2017). African girls and women have significant levels of physical and sexual violence (SVRI & UN Women Africa, 2023), with research unveiling an intersection between violence and culture (Thomas, 2020). As an androcentric society, Cape Verde perpetuates unequal practices between men and women, fostering conditions that normalize violence as a means of maintaining gender hierarchies. Gender-based violence is criminalized in Cape Verde. Since 2000, with the approval of the first Penal Code, maltreatment among spouses was typified as a semi-public crime. In 2011, the Special Law on Gender-based Violence (Law No 84/VII/11) defined violence against women as a symptom of unequal power relations and a mechanism to control women. In doing so, the concept of domestic violence was replaced, and the crime was converted into public, i.e., the criminal procedure became independent of the victims’ will (Silva, 2022). Data from the Demographic and Reproductive Health Survey-II (INE & Ministério da Saúde, 2008), concerning 2005, signals that 17% of women since the age of 15 years old were exposed to physical violence, 14% to emotional violence, and 4% to sexual violence by their spouses or intimate partners. Thirteen years later, the situation is slightly different, with recent evidence from the Demographic and Reproductive Health Survey-III (INE & Ministério da Saúde & Segurança Social, 2020), concerning 2018, indicating that 14% of women since the age of 15 years old were exposed to emotional violence, and 11% and 6% to physical and sexual violence, respectively. Nearly 7% of the victims suffered from intimate partner violence between the age of 15 and 24 years old. Considering that the average age of the first marriage is 25.5 years old for women, the percentage may be referred to cases of dating violence. The main authors of intimate partner violence were male spouses or intimate partners in current or former relationships. Despite this, 9% of women admitted having perpetrated physical violence against their spouses or intimate partners. The percentage of female aggressors is higher in cases where they were previously victims of physical violence by their spouses or intimate partners (26% vs. 3%). Only 40% of women victims of intimate partner violence sought help. According to the United Nations (2022), although the incidence of gender-based violence decreased by 50% between 2015 and 2020, dropping from 22% to 11%, women and girls residing in rural areas and with limited formal education experience higher rates of victimization, reaching 19%. As a result of the pandemic for COVID-19, the rate increased by 24%. Despite legal advances, E. M. Rodrigues et al. (2024) found that the severity of punishment in gender-based violence cases is inconsistent and frequently informed by subjective factors, with victims facing difficulties in being protected. The authors concluded that the Cape Verdean criminal justice system requires improvement, particularly in behavioral and psychological support in judicial decisions, responding to victims’ needs, and contributing to perpetrators’ recidivism decrease. Although official statistics on dating violence in Cape Verde are lacking, scientific studies and data from non-governmental associations show that youth is also vulnerable to intimate partner violence (Medina, 2020; M. L. Monteiro et al., 2019; Neves et al., 2016; Neves et al., 2019). As concluded by research conducted in other West African countries, traditional beliefs legitimizing intimate partner violence persist as an indicator of gender asymmetries (Ribeiro et al., 2024). Ghana, Liberia, and Gambia, among others, reveal high percentages of violence, with lower socioeconomic status and cultural norms influencing discrimination and gender-based violence (Jabbi et al., 2020; Ogum Alangea et al., 2018; Sileo et al., 2021). A study aiming to compare Portuguese and Cape Verdean youths’ beliefs about intimate partner violence and the frequency of self-reported violent behavior in dating relationships discovered a more significant relationship between traditional beliefs and self-reported violence among Cape Verdean adolescents when compared to Portuguese, though no differences were found in the overall prevalence of abuse between the two samples (Neves et al., 2016). Recent research, conducted by Neves et al. (2019), revealed that though the differences between genders are not significant in terms of dating violence practices, attitudes toward male psychological dating violence are significantly higher in Cape Verdean male students. M. L. Monteiro et al. (2019) concluded that while Cape Verdean youth present, in general, a lower rate of dating violence, boys have a higher average in what is concerned with perpetrated sexual violence, perpetrated and suffered relational violence, and suffered physical violence. Girls scored higher in experiencing sexual violence, perpetrating and experiencing threats, perpetrating and experiencing emotional violence, and perpetrating physical violence. Girls scored higher in suffering sexual violence, perpetrated, and suffered threats, perpetrated, and suffered emotional violence, and perpetrated physical violence. For the whole sample, psychological violence was the most perpetrated, followed by physical and sexual violence. To fill the gap in scientific studies on dating violence among Cape Verdean youth, the present study aims to analyze the association between victimization and perpetration of dating violence and Cape Verdean university students’ gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence. The following research questions were defined:

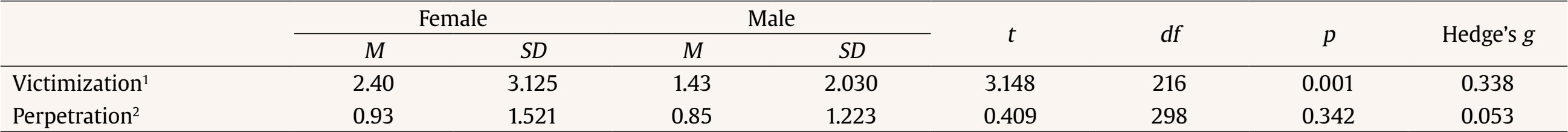

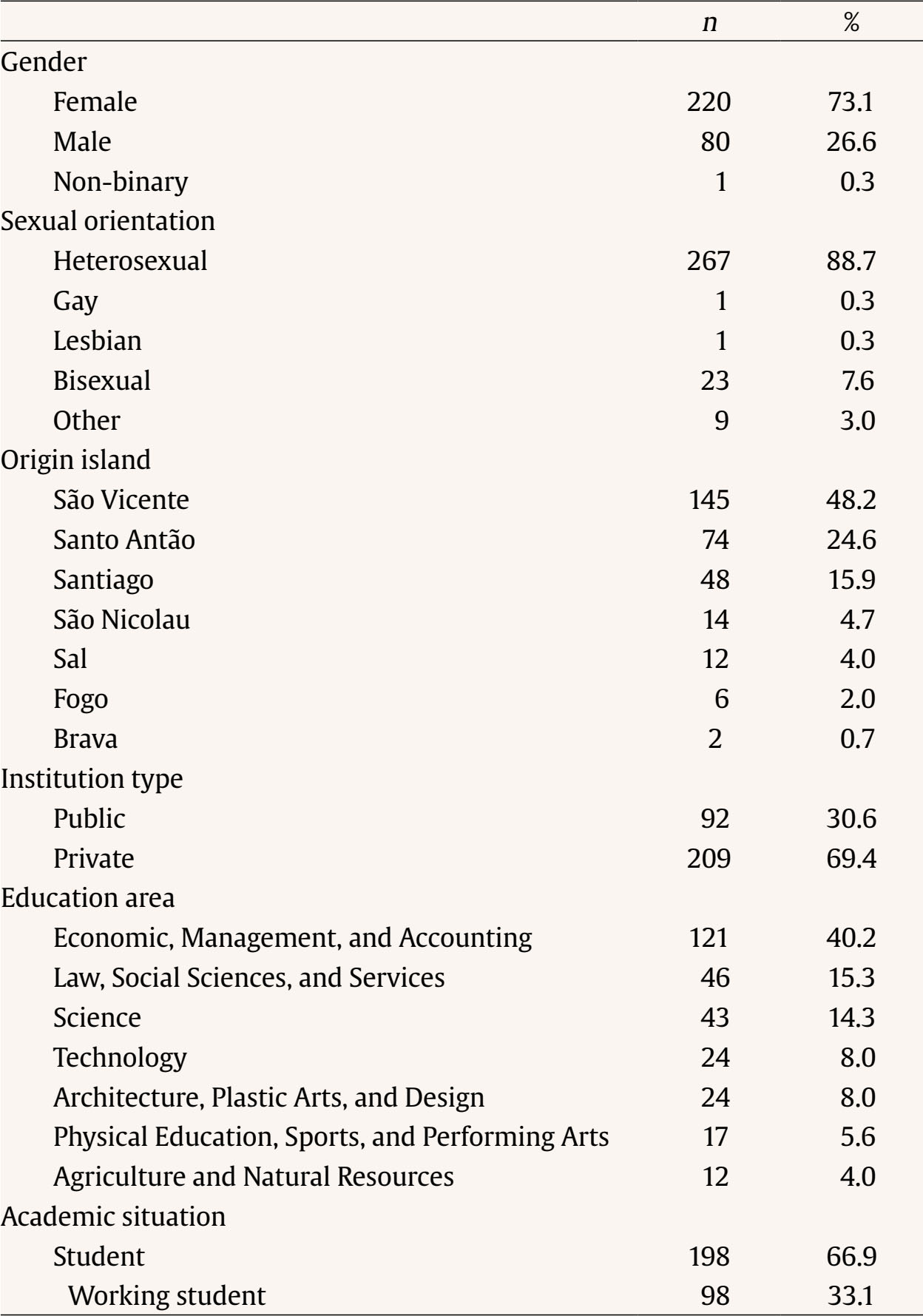

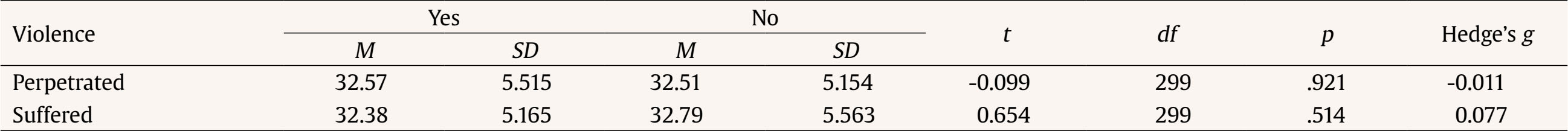

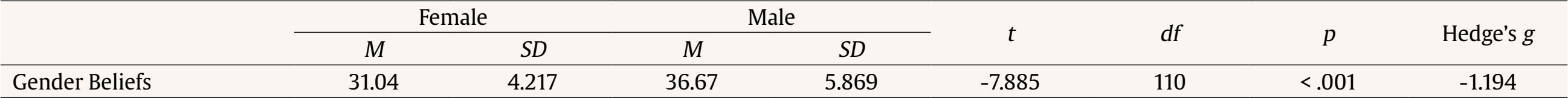

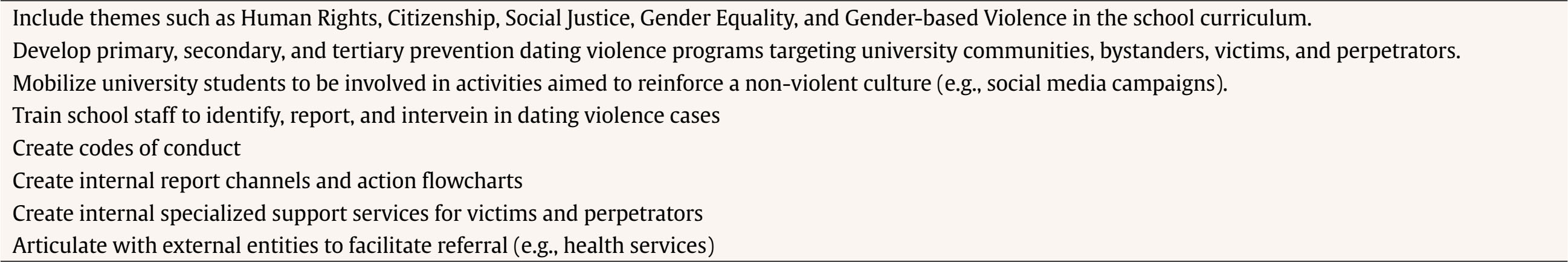

Research Hypotheses Our first hypothesis was that dating violence would reveal no gender differences in terms of victimization (H1). The second hypothesis was that dating violence would be more frequently perpetrated by males than by females (H2). The third hypothesis was that psychological and physical violence would be more prevalent than sexual violence, stalking, and economic violence (H3). The fourth hypothesis was that males would show higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence than females (H4). The fifth hypothesis was that participants who suffered violence would exhibit higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence than participants who did not suffer violence (H5). The last hypothesis was that participants who perpetrated violence would show higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence than participants who did not perpetrate violence (H6). Sample and Procedure The sample consisted of 301 Cape Verdean university students, 220 females, 80 males, and one non-binary person, aged between 17 and 53 years old (M = 23.86, SD = 6.112) (Table 1). Most students were heterosexual (n = 267, 88.7%). Nearly 50% were from S. Vicente (n = 145, 48.2%) and 24.6% (n = 74) were from Santa Antão. Almost 70% (n = 209, 69.4%) attended private universities, 40.2% (n = 121) attended courses in Economics, Management, and Accounting, and 15.3% (n = 46) and 14.3% (n = 43), respectively, courses in Law, Social Sciences, and Services and Sciences. Almost 67% (n = 198 of the participants were full-time students and 33.1% (n = 98) had also a job. The boards of Cape Verde’s universities were contacted via email, informed about the study goals (the characterization of the relationship between gender beliefs and dating violence practices among university students in Cape Verde) and asked to disseminate it among students. Additionally, the study was divulgated through social media accounts, namely Instagram and LinkedIn. Once authorized, Cape Verdean students were invited to fill out an anonymous, confidential online questionnaire. Data was collected between 2021 and 2022. The study met all the ethical standards of scientific research with human beings, the Code of Ethics of the Order of Portuguese Psychologists, and the General Data Protection Regulation. At the end of the questionnaire information on Cape Verdean services aimed to support victims of domestic violence was provided, along with an email of the person in charge of the study to be used if necessary. Instruments The first part of the questionnaire consists of informed consent, followed by sociodemographic questions (e.g., age, nationality, education area), the Inventory of Gender Beliefs, and the Inventory of Violent Juvenile Relationships (Neves et al., 2023). The Inventory of Gender Beliefs assesses participants’ beliefs on gender social relations and contains 24 items on a five-Likert scale (e.g., “Women who don’t want to become mothers aren’t real women”; “Women are victims of sexual violence because they provoke men”; “Women and men must share domestic work”). The sum of the responses to the 24 items of the inventory was used to measure gender beliefs: higher values reflect more conservative beliefs. Cronbach’s alpha value was .737. The Inventory of Violent Juvenile Relationships seeks to characterize psychological, physical, sexual, economic, and social violence and stalking. It is composed of 21 items, with the answer options: “Never happened to me”, “I already suffered”, “I already perpetrated”, and “I already suffered and perpetrated” (e.g., “Force me to have unwanted sex behaviors”; “Keep all my money or limit/control my expenses”; “Threat me verbally or through behaviors causing fear”). Victimization was measured by accounting for the number of “I already suffered” responses, and perpetration was measured by accounting for the number of “I already perpetrated” responses. Persons who responded to at least one item with “I already suffered” or “I already perpetrated” were accounted as victim and/or perpetrator, respectively. The different typologies of violence were defined according to the definitions presented in the literature. The instruments were chosen because the study’s authors used them with reliable results in prior research with similar samples. Statistical Analyses Data were treated and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 28 for Windows. Descriptive and inferential analyses were run, using association and difference tests as inter-subject design tests. Regarding the different sample sizes, Hedge’s g was used to evaluate the effect size of differences in means. The repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse-Geisser correction and Cochran’s Q test was also used to analyze differences between violence typologies. A significance level of .05 was assumed to identify statistically significant differences. From the sample, 166 participants referred to being involved in a dating relationship (55.1%) and 115 have been in the past (38.2%). Nearly sixty percent (61.1%, n = 184) admitted having been victims of dating violence, while 46.8% (n = 141) mentioned having perpetrated at least one act of dating violence. Of these, 120 (39.9%) acted simultaneously as victims and perpetrators (65.2% of victims and 85.1% of perpetrators). A statistically significant, moderate, association between victimization and perpetration, was found, χ2(1) = 64.177, p < .001, φ = .462. In terms of victimization, psychological violence was the most expressive (54.8%, n = 165), followed by social violence (27.2%, n = 82), physical violence (13.6%, n = 13.6%), stalking (11.6%, n = 35), sexual violence (10.6%, n = 32), and economic violence (2.0, n = 6), with Cochran’s Q test determining that there was a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of victimization for different types of violence, χ2(5) = 399.215, p < .001. Psychological violence is also the most perpetrated (38.9%, n = 117), followed by physical violence (10.0%, n = 30), social violence (9.0%, n = 27), sexual violence (4.3%, n = 13), stalking (2.3%, n = 7), and economic violence (0.7%, n = 2), with significant differences between proportions, χ2(5) = 335.931, p < .001. Differences between the means of dating violence perpetrated between different typologies were found to be statistically significant, F(3.12, 934.44) = 45.975, p < .001, η2p = .133, with psychological (M = 0.11, SD = 0.169) revealing higher levels of perpetration when compared with physical (M = 0.02, SD = .079), social violence (M = 0.02, SD = 0.083), sexual violence (M = 0.02, SD = 0.075), stalking (M = 0.02, SD = 0.151) and economic violence (M = 0.01, SD = 0.081). Female participants show higher levels of victimization (M = 2.40, SD = 3.125) compared to male participants (M = 1.43, SD = 2.030) (Table 2), with a statistically significant difference, t(216) = 3.148, p = .001, g = 0.338. Although female participants show higher levels of perpetration (M =.93, SD = 1.521) when compared to male participants (M = .85, SD = 1.223), the difference between groups is not statistically significant, t(298) = 0.409, p = .342, g = 0.053. Concerning gender, the difference in victimization levels is statistically significant, while it is not for perpetration. Tabla 2 Results of the Inventory of Violent Juvenile Relationships by Gender   Note. 1Number of items selected as suffered. 2Number of items selected as perpetrated The global sample reveals a low level of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence (M = 32.53, SD = 5.318). When comparing participants who suffered violence (M = 32.38, SD = 5.165) with participants who did not suffer violence (M = 32.79, SD = 5.563), no statistically significant differences were found, t(299) = 0.654, p = .514, g = 0.077. In the same way, when comparing participants who perpetrated violence (M = 32.57, SD = 5.515) with participants who did not perpetrate (M = 32.51, SD = 5.154), no statistically significant differences were found, t(299) = -0.099, p = .921, g = -0.011 (Table 3). Regarding gender, male participants reveal a higher level of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence (M = 36.67, SD = 5.869) when compared to female participants (M = 31.04, SD = 4.217), a difference which is statistically significant, t(110) = -7.885, p < .001, g = -1.194) (Table 4). The results of the present study reveal that dating violence among Cape Verdean university students is extensive, reaching nearly 60% and 50% of the sample concerning victimization and perpetration, respectively. Compared to recent international studies (Sardinha et al., 2022), the prevalence of the phenomena is higher than the global average, with 24% of women aged 15 to 19 years and 26% of women aged 19 to 24 years having already experienced at least once since the age of 15 years, physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence.┬áIn the same sense, general data on gender-based violence in Cape Verde indicate a percentage of 11% of victims, aggravated to 19% in the case of women and girls residing in rural areas and with limited formal education (United Nations, 2022), which are significantly lower when compared to 61.1% of the sample of the present study who reported being victimized in dating relationships. This finding is not only relevant in terms of its novelty, as data on dating violence among Cape Verde university students is almost inexistent, but also because it reinforces the necessity to act preventively. Additionally, and considering the shortage of studies characterizing dating violence in West Africa, the present research may contribute to a better understanding of how African culture, which is yet framed by patriarchal norms, informs criminal behaviors in intimate relationships. As dating violence is a risk factor for adult intimate partner abuse violence (Greenman & Matsuda, 2016), it is critical avoiding that early perpetration is associated with later perpetration of dating violence, by investing and more and better community-level approaches (Debnam, & Temple, 2021; Neves et al., 2023). Although female and male participants are both exposed to the phenomena, female participants show higher levels of victimization and perpetration compared to male participants, despite the difference between groups is not statistically significant concerning perpetration. Thus, we did not find support for both our first and second hypothesis that dating violence reveals no gender differences in terms of victimization and that dating violence is more perpetrated by males than by females, respectively. Even though scientific research has concluded that there are no gender differences regarding dating violence perpetration, with female and male adolescents being perpetrators and victims (e.g., Ahmadabadi, 2021), evidence suggests that male adolescents’ engagement in dating violence is higher than females, with females reporting more adverse outcomes (Dardis et al., 2015). Authors such as Malhi et al. (2020) argue that male entitlement might explain why adolescent males engage most in perpetration behaviors against female adolescents. Male entitlement is justified by the social belief that men are legitimized to exert control towards women, even though the practice of intimate partner violence. In our study, male participants show higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence than females, which allows us to accept the fourth hypothesis. The research conducted by Neves et al. (2016) had previously shown an association between violent behavior in intimate relationships, especially physical violence, and endorsement of beliefs among Cape Verdean adolescents, with an average age of 16 years old. In the same way, the study developed by Neves et al. (2019) illustrates that male Cape Verdean students support violence justified by a woman’s misconduct, except for physical and sexual attitudes towards female dating violence, and minimize small violent acts. As argued by Reyes et al. (2016), gender role attitudes strongly increase the risk of dating violence perpetration among boys. This argument might be pointed out to discuss the results, as Cape Verdean society is still marked by traditional representations of gender-social relations and intimate relationships (Carter & Aulette, 2009; Thomas, 2018). As demonstrated earlier, by M. L. Monteiro et al. (2019), psychological violence is the most common typology of dating violence suffered by university Cape Verdean students, followed by physical violence. In this study, we confirm that psychological violence is the most common typology both for victimization and perpetration, with a significant difference for other typologies of violence. Regarding perpetrated violence, physical and social typologies show up as the second most expressive. When suffered violence is analyzed, Cape Verdean students refer to social typology as the second most prevalent. Thus, the third hypothesis, that psychological and physical violence was more prevalent than sexual violence, stalking, and economic violence, was accepted. As in other studies, the prevalence rates of psychological violence vary between 20 and 70% among adolescents (Stonard et al. 2014) and the prevalence rate of physical violence is 21% (Wincentak et al., 2017). In the present study, the prevalence rate of psychological violence is 54.8% and the prevalence rate of physical violence is 13.6%. Regarding both the fifth and the sixth hypothesis, that participants who suffered violence showed higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence than those who did not suffer violence and that participants who perpetrated violence manifested higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence than those who did not perpetrate, respectively, we did not find support to accept them. Contrary to other studies (e.g., Neves et al., 2020; Nydegger et al., 2017), in the present research suffering or perpetrating dating violence is not associated with gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence. Hence, in this sample, gender seems to be the most relevant factor in the endorsement of conservative beliefs regarding dating violence, supporting the idea that different prevention strategies must be used for males and females. The present study aimed to analyze the association between victimization and perpetration of dating violence and Cape Verdean university students’ gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence, responding to four research questions. Although data is referred to Cape Verde, results can bring to light important questions on how cultural backgrounds influence interpersonal relationships, especially in the context of intimacy. Moreover, as there are no previous studies on the phenomenon, the present research opens the way to a better understanding of how dating violence affects youth and their development. One of the main conclusions is that dating violence exists and largely affects Cape Verdean university students of both sexes, as victims and perpetrators. The most prevalent typologies are psychological and physical violence. Second, female students suffer more dating violence than male students. Third, male participants reveal higher levels of gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence. Fourth, there is not an association between victimization and perpetration of dating violence and Cape Verdean university students’ gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence. As concluded in other studies, gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence play an important role in youth behaviors. Deconstructing traditional values rooted in power asymmetries between women and men should be addressed as a priority in educating children and adolescents. According to the results, it is possible to state that policies and measures preventing and combating gender-based violence in Cape Verde must consider university students and that universities must develop internal plans addressing dating violence as a major problem, offering specialized services to victims and offenders. Following national orientations (e.g., Cape Verde National Gender Equality Plan 2022/2026) concerning dating violence prevention and specialized support services for victims and perpetrators, some education policy recommendations are suggested in Table 5. Policy recommendations must adopt a multi-sectorial approach and be subject to a systemic evaluation, by governmental and non-governmental institutions, and academia, so changes can be adjusted over time. Limitations and Further Research Although academically and socially significant, the study presents some limitations. The size of the sample size could be larger, and the representativeness of the islands more equilibrate. Additionally, male participants are underrepresented, as well as other gender identities and sexual orientations. The adhesion of participants was difficult to obtain, maybe because the data collection methodology was exclusively online. Online social science surveys tend to present gender effect on the survey participation rate, with a lower rate of response from men (Becker 2022; Slauson-Blevins & Johnson, 2016), with this phenomenon being particularly noticed in sensitive topics such as intimate partner violence (Fanslow et. al, 2023; Tourangeau, 2007). Therefore, the findings across gender cannot be assumed to be free from gender bias and results should be carefully interpreted. The lack of scientific research on the topic makes comparative analyses difficult, so more studies are needed to better understand the dimensions and the dynamics of the phenomena. A qualitative study focusing on Cape Verdean university students’ practices and beliefs might be an important contribution to clarify some results, namely results that are related to gender differences. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Neves, S., Borges, J., & Antunes, A. (2026). Dating violence and gender beliefs legitimizing dating violence among Cape Verdean university students. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 36, Article e260467, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a14 References |

Cite this article as: Neves, S., Borges, J., & Antunes, A. (2026). Dating Violence and Gender Beliefs Legitimizing Dating Violence among Cape Verdean University Students. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 36, Article e260467. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a14

Este artículo forma parte de la sección monográfica "Violencia de género". Correspondence: asneves@umaia.pt (S. Neves).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS