Child Sexual Abuse Attributions: Are They Different Depending on Mothers versus Fathers’ Reactions?

[La atribución del abuso sexual en la infancia: ¿es distinta según la reacción de la madre o del padre?]

Eunice Magalhães1, Andreia Gomes2, João Graça3, 4, Carla Antunes5, Inês Chim1, Célia Ferreira5, Patrício Costa6, and 7

1Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE), CIS-ISCTE, Lisbon, Portugal; 2Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE), Lisbon, Portugal; 3Instituto de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal; 4University of Groningen, The Netherlands; 5Universidade Lusófona, HEI-Lab: Digital Human-Environment Interaction Labs, Lisbon, Portugal; 6ICVS/3B’s - PT Government Associate Laboratory, Braga/Guimarães, Portugal; 7Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Porto, Portugal

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a5

Received 7 September 2023, Accepted 4 September 2024

Abstract

Family reactions to child sexual abuse (CSA) are important, but there is a lack of research on the effect of maternal and paternal reactions on social attributions towards the victim and perpetrator. We conducted an experimental study (N = 549, aged 18-76) using vignettes in which the reactions of the mother or father (blame, denial, or support) were manipulated. Statistically significant differences were found for the blame scenario on victim culpability, meaning that participants reported greater victim culpability when the father blamed the victim than when the mother did so. The hypothesised moderating effect of empathy was not confirmed. The results also showed that younger participants tended to attribute greater seriousness to the assault, greater honesty and credibility to the victim, greater culpability to the perpetrator, and less culpability to the victim. Women reported higher levels of victim credibility than men. Furthermore, women and more educated participants reported lower levels of victim culpability and greater assault seriousness. Positive associations were also found between empathy and the perceived seriousness of the assault. The findings and discussion shed light on the differences in CSA attributions depending on mothers’ and fathers’ reactions.

Resumen

Las reacciones familiares al abuso sexual infantil (ASI) son importantes, pero hasta donde sabemos la investigación aún no ha explorado el papel específico de la reacción materna y paterna en la atribución social de la víctima y del perpetrador. Se realizó un estudio experimental (N = 549, edad 18-76) utilizando viñetas en las cuales se manipulaban las reacciones de la madre o del padre (culpa, negación o apoyo). Se encontraron diferencias significativas para el escenario de culpabilización de la víctima, lo que implicaba que los participantes atribuyeron mayor culpabilidad a la víctima en el escenario en el que el padre culpaba más la víctima que cuando era la madre. No se confirmó el hipotético efecto moderador de la empatía. Los resultados también mostraron que los participantes más jóvenes tendían a atribuir mayor gravedad a la agresión, mayor honestidad y credibilidad a la víctima, mayor culpabilidad al agresor y menor culpabilidad a la víctima. Las mujeres confesaron un mayor nivel de credibilidad a la víctima que los hombres. Además, las mujeres y los participantes de mayor nivel educativo mostraron un menor grado de culpabilidad de la víctima y mayor gravedad de la agresión. También se encontró una asociación positiva entre empatía y percepción de gravedad de la agresión. Los resultados y la discusión destacan las diferencias en la atribución de ASI según la reacción de las madres y los padres.

Palabras clave

Abuso sexual infantil, Reacción de la madre, Reacción del padre, Empatía, Atribución

Keywords

Child sexual abuse, Mother’s reaction, Father’s reaction, Empathy, Attribution

Cite this article as: Magalhães, E., Gomes, A., Graça, J., Antunes, C., Chim, I., Ferreira, C., & Costa, P. (2025). Child Sexual Abuse Attributions: Are They Different Depending on Mothers versus Fathers’ Reactions?. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 35, 71 - 78. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a5

Correspondence: Eunice_magalhaes@iscte-iul.pt (E. Magalhães).

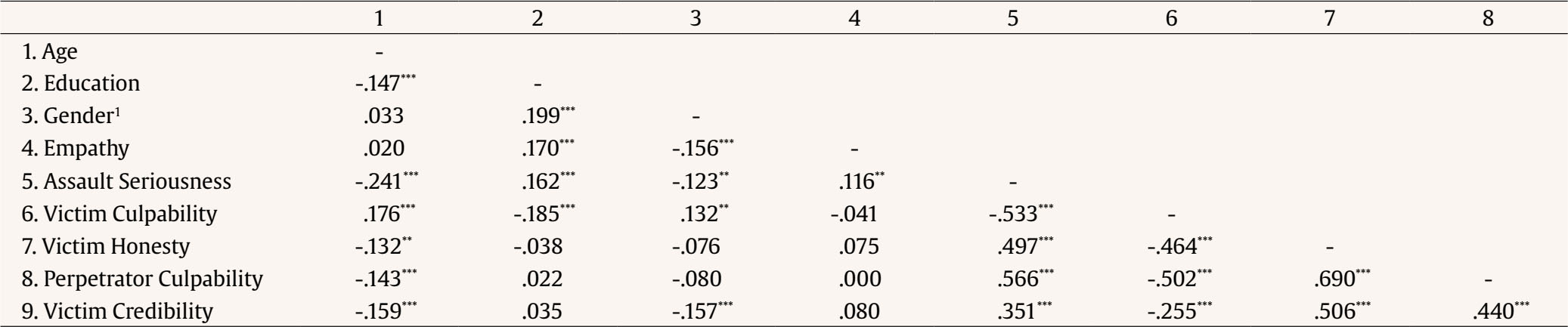

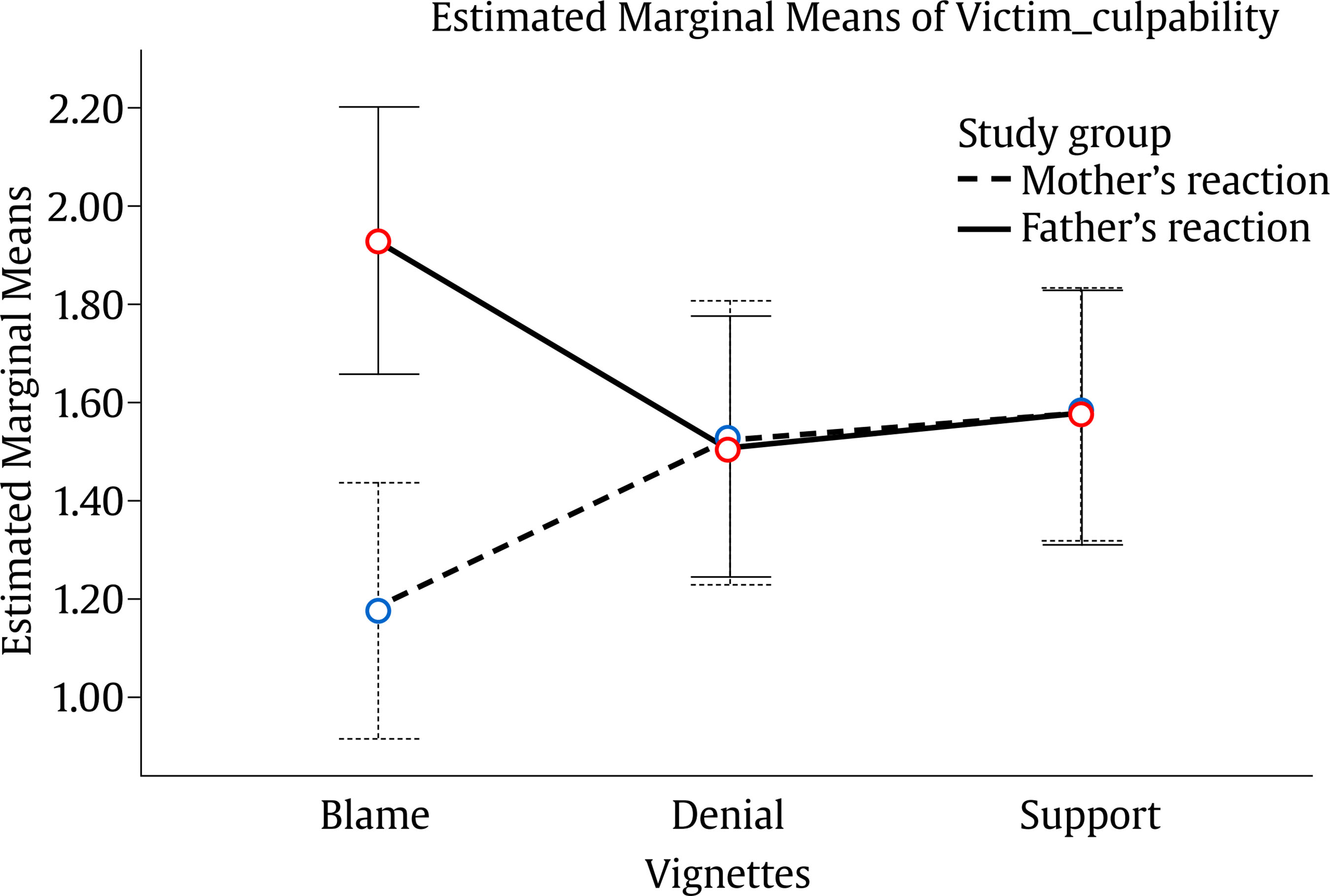

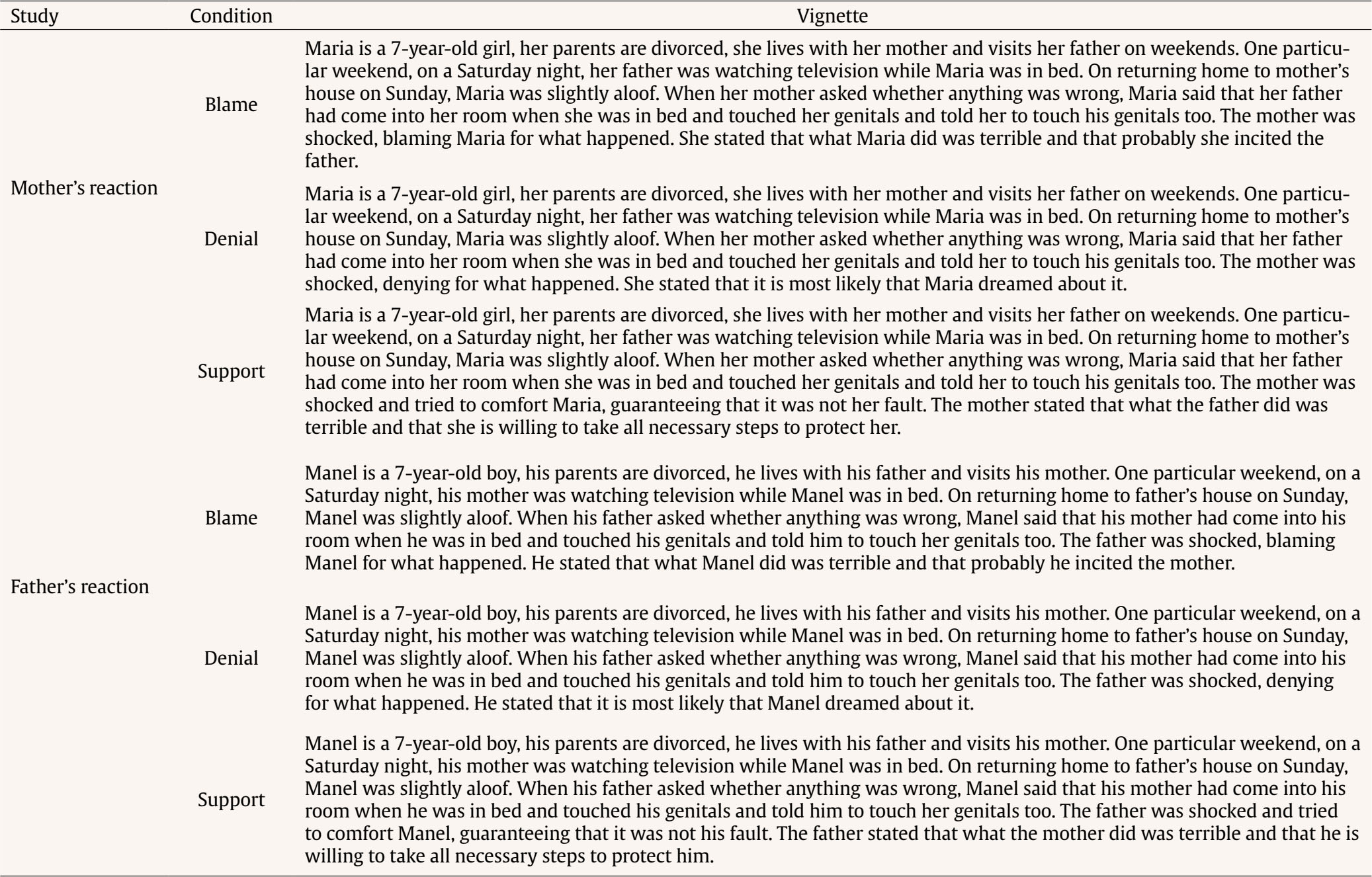

Child sexual abuse (CSA) has been extensively studied regarding its prevalence and impact on victims’ psychological functioning (Barth et al., 2013; Stoltenborgh et al., 2015). CSA, particularly intrafamilial CSA (Stroebel et al., 2012), presents a wide range of negative emotional, behavioural, and cognitive consequences, such as low self-esteem, social and interpersonal difficulties, anxiety, and depressive or dissociative disorders that may persist into adulthood (e.g., Fergusson et al., 2013; Greene et al., 2016; Hailes et al., 2019; Maniglio, 2009; Pérez-Fuentes et al., 2013). This negative impact of CSA may be exacerbated by negative and non-supportive social reactions. Blaming victims of CSA is a type of secondary victimisation which may have negative consequences on their psychological and emotional functioning (Anderson & Lyons, 2005; Greeson et al., 2016; Patterson, 2011), but also on future disclosures by CSA victims (Patterson, 2011). Fears of being blamed for CSA or not being believed are often identified as the reasons why victims do not disclose CSA and, consequently, do not seek or receive the support they need (Alaggia et al., 2017; Culda et al., 2018; Hamilton-Giachritsis et al., 2021). Minimizing, shaming, and blaming the CSA victims is particularly critical when conveyed by professionals working at formal institutions and agencies where CSA victims might seek help or support, such as police officers, judges, mental health professionals, or medical staff (Ahrens, 2006; Caproli & Crenshaw, 2017; Greeson et al., 2016). Nevertheless, these processes of blaming the victim and denying CSA are also conveyed by relatives of CSA victims (Graham et al., 2007). The literature suggests that the family is perceived as failing to care about their child when they are sexually abused (e.g., Graham et al., 2007), but to the best of our knowledge, there is no evidence focusing specifically on a comparison between the roles of mother and father. Given the widely acknowledged influence of gender roles on socialisation, and specifically on parenting, in this study, we aimed to explore attributions to CSA depending on maternal vs. paternal reactions. Child Sexual Abuse Attributions: The Role of Social Reactions CSA disclosure often involves negative social reactions (Kennedy & Prock, 2016), including devaluing the abusive experience, disbelieving, or blaming the child, which is especially common in cases of intrafamilial abuse (Ullman, 2003, 2007). These social reactions and devaluations may be due to the lack of evidence (physical and material) to substantiate CSA, since this abusive experience does not always leave physical marks and might involve a variety of abusive behaviours, ranging from sexualised touching or exposure to pornography to more intrusive behaviours such as vaginal or anal penetration (Faller, 2020; Frangez & Maver, 2013). Moreover, the secret involved in CSA cases (McElvaney et al., 2012), the length of judicial proceedings, and the lack of specific training for the professionals involved in these cases pose additional challenges for investigation and evaluation (Shead, 2014). This evidence highlights that both social reactions and children’s ability to disclose CSA are multi-determined, underlining the complexity of this phenomenon. The disclosure of intrafamilial CSA seems to be more complex and difficult than that of extrafamilial CSA (Alaggia et al., 2017; Loinaz et al., 2019; Morrison et al., 2018; Tener, 2017). The victim’s ambivalent feelings toward the perpetrator, together with the child’s fear of the disclosure’s consequences (e.g. fear of social reactions to disbelieve) and the need to protect the family (specifically, the non-abusive parent), may explain these difficulties of CSA disclosure (Foster & Hagedorn, 2014; Jensen et al., 2005; McElvaney et al., 2013; Schaeffer et al., 2011; Schönbucher et al., 2012; Shalhoub-Kevorkian, 2005). Negative social reactions to CSA disclosure have both short- and long-term consequences for victims, namely psychological difficulties (Hong et al., 2011; Palo & Gilbert, 2015; Ullman & Filipas, 2005), and a higher risk of sexual revictimization (Brenner & Ben-Amitay, 2015; Hornor & Fischer, 2016). Therefore, it is critical to explore the factors that influence CSA attribution. Previous evidence suggests that attributions of honesty and credibility to CSA victims depend on the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator (Davies et al., 2013; Davies & Rogers, 2009). Victims of CSA perpetrated by the father were considered less honest and credible than those in which the perpetrator was a stranger. Furthermore, the CSA perpetrated by the father is perceived as more severe than the CSA perpetrated by a family friend (Davies & Rogers, 2009), arguably because it goes against what is expected about parents’ role in care and protection. Nevertheless, fathers are also viewed as less guilty when compared to a stranger (Davies & Roger, 2009), possibly because individuals perceive CSA perpetrated by a stranger as involving more planning and premeditation whereas when the perpetrator is the father less “assault planning” may derive from greater physical and emotional closeness with their child (Davies & Roger, 2009). In Western countries, there is a widespread social representation that a parent’s primary responsibility includes protecting their children from harm, therefore when a child is abused, the family is perceived as failing to care about their child (e.g., Back & Lips, 1998; Berkowitz, 1997; Graham et al., 2007; Waterman & Foss-Goodman, 1984). Back and Lips (1998), for example, found that 70% of participants in their study ascribed some level of responsibility to parents for the CSA of their daughter in a hypothetical scenario, stating that parents should not have left the younger child alone and that they should have been taught to the older child how to prevent CSA. Additionally, gender stereotypes persist, particularly regarding the parenting roles of women and men. Mothers are stereotyped as primary caregivers, as it is expected that when women become mothers, childcare becomes a priority and overlapping with work if required, although this is not the case for men (Ellemers, 2018; Morawska et al., 2021). This might lead to the social expectation that women, rather than men or fathers, oversee child protection and caregiving (Caplan, 1990; Croghan & Miell, 1995; Davies et al., 2013; Graham et al., 2007). In the context of CSA, Waterman and Foss-Goodman (1984) supported this social representation by demonstrating that despite a certain level of liability for CSA being ascribed to both parents (non-offenders), this ascription is higher than that of mothers. Specifically, in intrafamilial CSA, Croghan and Miell (1995) add that “while fathers and parental figures are more likely to be perpetrators, they are also more likely to be excused and exonerated than mothers and maternal figures” (p. 37). The literature suggests that women, compared to men, attribute more blame for CSA to their mothers, especially when the perpetrator is the biological father (compared to the stepfather) (Davies et al., 2013) and when the child is younger (Rogers et al., 2009). Moreover, the mother seems to be perceived as more guilty when the perpetrator is emotionally distant (vs. close) from the victim (Davies et al., 2013). This evidence was supported by Zagrodney and Cummings (2016), who explored the differences in blame attributions to non-offending mothers depending on whether the perpetrator was the child’s biological father or the mother’s boyfriend. The authors found that blaming attributions to the mother were greater when the perpetrator was her boyfriend, which means that the relationship between the child and father is perceived as different. The relationship between the child and father is perceived as emotionally closer than that between the child and mother’s boyfriend (Zagrodney & Cummings, 2016). Davies et al. (2013) have highlighted this evidence by suggesting that participants may perceive the mother as neglecting the child’s safety, namely due to the lack of supervision of an emotionally distant relationship. Overall, these findings emphasise the participants’ perceptions of their mothers as primary caregivers and as having the key responsibility to protect their children (Davies et al., 2013). Despite the stereotypes and perceptions that portray the mother as a protecting caregiver, evidence suggests that the maternal response to CSA disclosure can be negative (e.g., blaming the child for what happened) or inconsistent and ambivalent (e.g., believing the child’s allegations but not taking protective action), particularly when the abuse is intrafamilial (Bolen, 2002; Elliott & Carnes, 2001; Heriot, 1996; Pintello & Zuravin, 2001; Ullman, 2003). Similarly, past research suggests that a family’s reaction to CSA plays an important role in attributing blame to the child’s victim. Graham et al. (2007) conducted a pioneering study on this topic, examining how the family’s reaction to their daughter’s CSA disclosure influences blame attributions to the victim, the family, and┬áthe perpetrator.┬áThe results showed that when a family’s reaction was supportive of the victim, the family was perceived as less culpable than when it denied abuse or blamed the child (Graham et al., 2007). In short, if a family’s reaction to CSA disclosure was not supporting the child, the family was viewed as non-protective, given that they allowed CSA to occur and did not provide support to the child thereafter. These findings are strengthened by evidence suggesting that when victims of sexual violence are supported by family, friends, and the local community, they tend to be perceived as less guilty than victims without support (Anderson & Lyons, 2005). Even if false allegations of CSA are not typical (Cromer & Goldsmith, 2010) and delays in disclosure are more frequent than false allegations (London et al., 2005), supportive relationships in these circumstances are also important to ensure that the truth is determined. Suggestibility is described in the literature as being associated with false CSA allegations (Denne et al., 2020; London et al., 2005), which suggests that providing support for the child, being available to them, and validating the child’s emotional states and potential suffering may offer a favourable context for sharing truthful and reliable information (Hershkowitz, 2009; Hershkowitz et al., 2014; Saywitz et al., 2002). Child Sexual Abuse Attributions: The Role of Empathy Empathy involves the ability to take others’ perspectives and emotions (Geer et al., 2000). Past research suggests that more empathetic individuals tend to attribute less responsibility and higher credibility to CSA victims (Bottoms et al., 2014), perceive CSA as more severe, perceive the victim as more honest and less guilty, and perceive the perpetrator as more guilty (Magalhães et al., 2021). These findings indicate that empathetic individuals can be compassionate and fully understand the victims’ experiences and feelings (Bottoms et al., 2014). On one hand, being able to take the victim’s perspective allows people to hold more pro-victim attitudes in the context of CSA (Bottoms et al., 2014; Feldman et al., 1998). On the other hand, people who are unable to recognise the state of mind or emotions of others may be more prone to blame CSA victims (Magalhães et al., 2021). Moreover, these differences may be due, in part, to gender differences in empathy, as men tend to score lower on empathy than women; therefore, they may reveal more negative attributions in the context of CSA (Bottoms et al., 2014; Magalhães et al., 2021). For these reasons, we assumed that empathy may play a moderating role in the association between the manipulation of parents’ reactions and participants’ attributions of CSA. Research Aims and Context Considering the short- and long-term impact of social reactions to CSA on victims’ psychosocial adjustment (Brenner & Ben-Amitay, 2015; Hong et al., 2011), there is a pressing need to explore the factors that contribute to people’s attributions to CSA. Previous evidence has highlighted the relevance of families’ reactions to CSA disclosure (Graham et al., 2007); however, to our knowledge, there are no studies that explore parents’ reactions to CSA disclosure on people’s attributions to CSA, and specifically consider the role of maternal versus paternal reactions. As such, we conducted an experimental study aimed at providing additional evidence on the role of parents’ reactions to CSA disclosure in participants’ attributions towards CSA, the victim, and the perpetrator. Bearing in mind the gender stereotypes and differences regarding the caregiving role (Caplan, 1990; Croghan & Miell, 1995; Davies et al., 2013), three scenarios (blame, denial, and support) were manipulated according to two conditions: mother’s reaction and father’s reaction. In addition, considering that attributions to CSA may vary according to individuals’ empathy (Bottoms et al., 2014; Jones & Bottoms, 2020; Magalhães et al., 2021), we aimed to analyse the moderating role of empathy in these associations. Based on previous evidence, we hypothesise the following. H1: Participants with lower empathy scores will make more negative attributions toward sexual abuse (i.e., higher attribution of responsibility and blame to the victim and less to the perpetrator, lower attribution of severity to the abuse, lower attribution of honesty, and credibility to the victim) than participants with higher empathy scores; and H2: When mothers (but not fathers) support the victim, fewer negative attributions toward sexual abuse will be assigned than when mothers do not support the victim (i.e., where the mother denies the abuse or blames the child), particularly for participants scoring higher on empathy. Participants Five hundred forty-nine adults participated in this study (Mage = 36.81, SD = 12.80, aged 18-76). Most participants were female (80.3%, n = 441), 51.9% were single, 36.2% were married, 11.5% were divorced, and 0.4% were widowed. Almost 66% participants were employed, 16.8% were students, 9.7% were unemployed, and 3.8% were retired. Most participants had completed an undergraduate degree (35.1%), 30.6% had a high school degree, 19% had a master’s degree, 13.1% had completed compulsory education only, and 2.2% had a doctoral degree. Materials Sociodemographic Questionnaire Participants filled out a short questionnaire to describe their demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, marital status, and education). Empathy Following previous studies (Magalhães et al., 2021; Milfont & Sibley, 2016), a three-item scale was included to measure participants’ empathy: “I sympathize with others’ feelings”, “I am not interested in other people’s problems” (reversed item), and “I feel others’ emotions”. These items were answered using a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In the current study, internal consistency was α = .55; however, when the reversed item was removed, acceptable internal consistency was obtained (α = .65, inter-item correlation = .34). CSA Vignettes A hypothetical CSA scenario was created based on previous studies (Davies & Rogers, 2009; Graham et al., 2007). The mother’s or father’s reaction (blaming the victim vs. denying the abuse vs. supporting the victim) was experimentally manipulated, yielding a total of six vignettes/scenarios. A between-subject design was adopted as each participant was randomly presented with one scenario (see Table 1). CSA Questionnaire After reading the vignette, the participants filled out a CSA questionnaire composed of ten CSA attribution items (Davies & Rogers, 2009; Magalhães et al., 2021) and rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). This questionnaire enables the assessment of five dimensions: perpetrator culpability (e.g., “The father is responsible for this event”; α = .91), victim culpability (e.g., “Maria is guilty of what happened.”; α = .70), victim honesty (e.g., “Maria is telling the truth about the event”; α = .79), victim credibility (e.g., “Maria is competent to provide reliable information about this type of event”; α = .72), and assault seriousness (e.g., “Maria’s life could be negatively affected by this event”; α = .77) (Magalhães et al., 2021). In the current study, the following internal consistency was found: perpetrator culpability (α = .88, inter-item correlation = .79), victim culpability (α = .54, inter-item correlation = .38), victim honesty (α = .79, inter-item correlation = .66), victim credibility (α = .67, inter-item correlation = .52), and assault seriousness (α = .72, inter-item correlation = .57). Manipulation Check After the completion of the materials (presented in this order), a manipulation check question was used to assess whether the manipulation was successful. This question is presented as follows: “In the scenario, the mother (or father) responds to Maria/Manel’s statement by” a) “Blaming her/him for what happened”, b) “Denying what happened”, c) “Protecting her/him from what happened”, or “Don’t know/do not remember”. Participants who provided non-valid responses or responded “Don’t know/do not remember” (n = 25) were excluded. Procedures of Data Collection and Analyses The current study is part of a wider project about myths and beliefs focused on CSA, developed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for implementing studies with human beings and approved by the Ethics IRB of ISCTE. Data collection was carried out using Qualtrics software, and the link was distributed on social media (e.g., Facebook) targeting adults aged 18 years or more. Participants were informed about the study conditions, such as anonymity, confidentiality, and voluntary participation. Self-selection bias was minimised by not providing specific details regarding the study’s aims. Participation in the study was voluntary and no financial/material compensation or incentives were offered. First, the participants filled out a sociodemographic questionnaire and then completed an empathy questionnaire. Lastly, the vignette was presented (i.e., each participant was randomly assigned to one scenario – three including the mother’s reaction and three including the father’s reaction), and a set of attribution items were filled out. Finally, a manipulation check is conducted. The data collection was performed in two steps. The data from the vignettes with the mother’s reaction were collected first (March-April 2021), followed by the data from the vignettes with the father’s reaction (January-May 2022). To increase the thoroughness of the data analysis, address our research aims, and reduce the type 1 error, the two datasets were merged, allowing the inclusion of experimental manipulation (mothers’ or fathers’ reactions) as a factor in the statistical analysis instead of duplicating tests. Data analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS® for Windows (version 28.0). A MANCOVA was used to examine how participants differed in their CSA attributions depending on the experimental manipulation of mothers’ or fathers’ reactions, controlling for participants’ demographics. In addition, the moderating role of participants’ empathy was tested. Similar to previous studies (e.g., Maffei et al., 2019), two subgroups of participants were created: one included participants (n = 176) reporting high levels of empathy (i.e., scores exceeded the 75 percentile) and the other included participants reporting low levels of empathy (i.e., scores were below 25 percentile) (n = 179). Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Study Variables   Note. Education: higher scores mean greater education; Gender: 0 = female, 1 = male. 1Point-biserial correlation coefficient. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Correlations for Sociodemographic and Study Variables Statistically significant associations were found between the study variables and sociodemographic attributes. Negative associations were found between age and Assault Seriousness, Victim Honesty, Victim Credibility, Perpetrator Culpability, and positive ones with Victim Culpability. Education was positively associated with Assault Seriousness and negatively associated with Victim Culpability. Males scored higher than females on Victim Culpability and lower on Assault Seriousness, Victim Credibility, and Empathy. Positive associations were found between Empathy and Assault Seriousness. Finally, positive associations were found between Assault Seriousness and Victim Honesty, Victim Credibility, Perpetrator Culpability, and negative ones between Victim Culpability and Assault Seriousness, Victim Honesty, Victim Credibility, Perpetrator Culpability (Table 2). Multivariate Analysis of Covariance Based on the correlation analyses, a multivariate analysis of covariance was performed, controlling for the participants’ gender, education, and age, and testing the moderating role of empathy. Box’s Test of Equality of Covariance Matrices was significant (481, p < .001), but Levene’s test of equality of error variances was significant for all dependent variables (p < .05), except for the victim’s credibility (p = .089). Wilks’ lambda test statistic was selected for heterogeneous variance to determine the significance of multivariate effects. There were no effects for either of the three scenarios (Wilks’ lambda = .952, p = .091, ηp2 = .024) or the moderator effect of empathy (Wilks’ lambda = .987, p = .930, ηp2 = .007). Significant multivariate effects were found for the parental role (father’s versus mother’s reactions) (Wilks’ lambda = .958, p = .015, ηp2 = .042), and for the interaction of the scenarios (blame, support, and denial) and parental role (father’s versus mother’s reactions) (Wilks’ Lambda = .946, p = .050, ηp2 = .027). Univariate analyses for the effect of the parental role in the attribution factors revealed significant effects for Assault seriousness, F(1, 342) = 7.583, p = .006; ηp2 = .022, Victim Culpability, F(1, 342) = 4.855, p = .028; ηp2 = .014, Victim Honesty, F(1, 342) = 10.911, p = .001; ηp2 = .032, and Perpetrator Culpability, F(1, 342) = 4.764, p = .030; ηp2 = .014. Specifically, participants reported greater Assault Seriousness (M = 6.58, SD = 0.75), Victim Honesty (M = 5.66, SD = 1.27), Perpetrator Culpability (M = 6.39, SD = 1.22), and lower Victim culpability (M = 1.41, SD = 0.87) in the mother’s reaction scenario than in the father’s reaction scenario (M = 6.31, SD = 0.98; M = 5.13, SD = 1.31; M = 5.98, SD = 1.50; M = 1.64, SD = 1.19; respectively). Moreover, univariate analyses for the interaction of the scenarios and parental role revealed significant effects on Victim Culpability, F(2, 343) = 5.376, p = .005, ηp2 = .031. Specifically, statistically significant differences were found only for the Blame scenario on victim’s culpability (p < .001, 95% CI [0.385, 1.135]), which means that greater victim’s culpability was reported by our participants on the scenario of father’s blaming the victim than on mother’s blaming reaction (Figure 1). Figure 1 The Interaction Effect of the Manipulation (blame, support and denial conditions) and Parental role (father versus mother) on Victim’s Culpability.   Note. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: gender = .1983, age = 35.69, education = 4.62, error bars = 95% CI. This study aimed to provide evidence on the influence of parents’ reactions to CSA disclosure on participants’ attributions towards CSA, the victim, and the perpetrator, as well as the moderating role of empathy. Specifically, we aimed to 1) provide additional insights regarding the associations between CSA attributions and empathy and 2) analyse the moderating role of empathy on the association between fathers’ and mothers’ reactions and participant attributions. Confirming our first hypothesis, participants scoring lower on empathy reported lower CSA severity than those scoring higher on empathy. Previous research has focused on the association between empathy and victim blaming, suggesting that lower empathy is associated with higher victim blaming (Bottoms et al., 2014; Feldman et al., 1998; Magalhães et al., 2021); however, previous studies have not addressed the role of empathy concerning severity attributions. Thus, these findings suggest that more empathetic people might be better able to anticipate the potential suffering of others in hypothetically risky circumstances, as is the case with CSA. These results can also be explained by other individual characteristics of the participants, such as gender, age, or education. Victim-blaming tendencies seem to differ according to gender (Bottoms et al., 2014; Magalhães et al., 2021), which was also true in the current study, given that males were more likely to score higher on victim culpability and lower on assault seriousness, victim credibility, and empathy than females. Age differences were also found, as older participants scored lower on attributions regarding CSA severity, blamed the victim more and the perpetrator less, and scored lower on victim honesty and credibility. This is consistent with evidence suggesting that older people might blame more victims because of their greater endorsement of CSA myths (e.g., Carey, 2015; Ford et al., 2001). Finally, highly educated participants perceived the CSA hypothetical case as more severe and the victim less culpable than less educated participants, which may suggest that more information and education may reduce the acceptance of sexual violence (Abeid et al., 2015) and the acknowledgment of CSA as potentially harmful. Regarding the second aim of this study and based on previous associations, a multivariate analysis of covariance was performed, controlling for participants’ gender, age, and education. Our second hypothesis was not supported by our findings, given the non-significant moderating effects of empathy, and the experimental manipulation did not work as hypothesised, in relation to the mother’s support for the victim. In fact, the results revealed a significant effect of the experimental manipulation (i.e., parental reactions) on the victim’s culpability only in the blame scenario. Participants ascribed significantly more blame to the victim when the father blamed the child for CSA than when the mother blamed the child. These results did not confirm our hypothesis, but they are in line with the findings of Graham et al. (2007) suggesting that the family reaction to CSA had no impact on attributions of blame and responsibility to the perpetrators. Moreover, the findings from this study seem to suggest that the scenario in which the mother blamed the child for the CSA may have been particularly threatening to the stereotype of the mother as a responsive, protective, and supportive caregiver (e.g., Waterman & Foss-Goodman, 1984), and for this reason our participants in this scenario ascribed less blame to the victim as a way of “protecting” the child. In addition, the victim’s age in our vignettes (seven years old) may have played an important role in participants’ attributions, considering that the gender stereotype about mothers’ protective role seems to be more noticeable in younger victims (Back & Lips, 1998; Rogers et al., 2007). Taken together, it is possible that reading about the mother blaming the child may have threatened our participants’ conceptions of motherhood and women as caregivers and caused them to blame the victim less as a cognitive compensatory mechanism to protect the child from secondary victimisation due to the mother’s blaming. Furthermore, the higher victim culpability when the father blamed the child might be explained by the social representation of women as not being able to sexually abuse their children (Tabak & Klettke, 2014), according to the stereotype of the mother as the main caregiver (Gerke et al., 2021; Gölge et al., 2021). Although theoretically plausible, these claims are only hypothetical explanations for our findings, which require further empirical support. Family reactions to disclosure of child sexual abuse are important. The results of this study suggest that participants reported greater victim culpability when the father blamed the victim than when the mother did so. The results also showed that younger participants tended to attribute greater seriousness to the assault, greater honesty and credibility to the victim, greater culpability to the perpetrator, and less culpability to the victim. Women reported higher levels of victim credibility than men. Furthermore, women and more educated participants reported lower levels of victim culpability and greater assault seriousness. Positive associations were also found between empathy and the perceived seriousness of the assault. Additional research is warranted to substantiate these findings and contributions. First, this study was based on an online convenience sample that mostly comprised female participants. Therefore, replication studies with representative and more balanced samples are needed to strengthen the external validity of our findings. Second, participants’ parental experiences were not assessed. Future research is needed to understand whether being a mother or father influences personal attributions of parental reactions to CSA. Similarly, no evidence was observed for the moderating role of empathy; therefore, additional efforts should be made to identify other moderating variables or mechanisms linked to these attributions (e.g., gender stereotypes and CSA myths). Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study offers a set of innovative findings on how parental reactions may shape others’ views about CSA, which is particularly significant for victims’ recovery (Elliot & Carnes, 2001; Yancey & Hansen, 2010; Zajac et al., 2015). Understanding these processes can improve supportive mechanisms in CSA allegations, facilitating a more adaptive recovery for victims and a better understanding of what is happening in false allegations. Specifically, optimising judicial procedures could also contribute to successful CSA processes, implementing developmentally appropriate information gathering protocols, specialised training for the professionals involved in CSA cases, and mobilising further resources to speed up the proceedings. Fostering positive attitudes toward CSA hypothetical victims means reducing myths and stereotypes that might undermine judicial procedures. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Magalhães, E., Gomes, A., Graça, J., Antunes, C., Chim, I., Ferreira, C., Costa, P. (2025). Child sexual abuse attributions: Are they different depending on mothers versus fathers’ reactions? Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 35, 71-78. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a5 References |

Cite this article as: Magalhães, E., Gomes, A., Graça, J., Antunes, C., Chim, I., Ferreira, C., & Costa, P. (2025). Child Sexual Abuse Attributions: Are They Different Depending on Mothers versus Fathers’ Reactions?. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 35, 71 - 78. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a5

Correspondence: Eunice_magalhaes@iscte-iul.pt (E. Magalhães).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS