Evaluation of a Parenting Training Program, “Limits”, in a Juvenile Justice Service: Results and Challenges

[La evaluación de un programa de formación parental, Límites, en un servicio de justicia juvenil: resultados y retos]

Màrius Martínez-Muñoz, Laura Arnau, and Marta Sabaté

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra (Cerdanyola del Vallès), Barcelona, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2018a14

Received 27 October 2017, Accepted 16 April 2018

Abstract

The aim of the study is to evaluate the results of “Limits”, a parenting training program which was implemented in a juvenile justice service by professionals from the Department of Justice. A controlled before and after design was undertaken to measure the effects of the program on the use of parental practices and parents’ perception of self-efficacy. Fifty-nine families with adolescents involved in the juvenile justice system participated either in an intervention group (n = 42 families) or in a waiting list group (n = 17 families). In order to triangulate the information, professionals and the target adolescents were also asked about the improvement of the parents in their parenting practices. A generalized linear model was used to compare the intervention and comparison groups. The findings demonstrate that the program had a positive impact on the intervention group with regards to the transfer of practices to their real life, especially those related to communication and family relationships. However, no significant changes were observed in parents’ perception of self-efficacy. The results are geared towards the improvement of future research evaluations using longitudinal designs.

Resumen

El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar los resultados del programa de entrenamiento de habilidades parentales “Limits” implementado en un servicio de justicia juvenil por profesionales del Departamento de Justicia. Se aplicó un diseño cuasi experimental pre-post test con grupo control para medir los efectos del programa en la utilización de las prácticas parentales y la percepción de autoeficacia de las familias. Participaron 59 familias con adolescentes dentro del circuito de justicia juvenil, ya fuera formando parte del grupo de intervención (n = 42 familias) o del grupo en lista de espera para entrar en el programa (n = 17 familias). Para triangular la información, se preguntó tanto a los profesionales participantes como los propios adolescentes por su percepción de mejora en relación con las prácticas parentales aplicadas por las familias en el ámbito cotidiano. Se aplicó un modelo lineal general para comparar el grupo intervención y el grupo comparación. Los resultados demuestran que el programa tuvo un impacto positivo en el grupo de intervención en lo referente a la transferencia de las prácticas parentales a la vida real, especialmente en aquéllas relacionadas con la comunicación y las relaciones familiares. Sin embargo, no se observaron cambios significativos en la percepción de autoeficacia por parte de los progenitores. Los hallazgos de este estudio están orientados hacia la mejora de futuras investigaciones utilizando diseños de evaluación longitudinales.

Keywords

Program evaluation, Juvenile justice, Family intervention, Self-efficacy, Parental practices.

Palabras clave

Evaluación de programas, Justicia juvenil, Intervención familiar, Autoeficacia, Prácticas parentales.

Cite this article as: Martínez-Muñoz, M. , Arnau, L. , & Sabaté, M. (2019). Evaluation of a Parenting Training Program, “Limits”, in a Juvenile Justice Service: Results and Challenges. Psychosocial Intervention, 28, 1 - 10. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2018a14

Correspondence: Laura.arnau@uab.cat (L. Arnau).

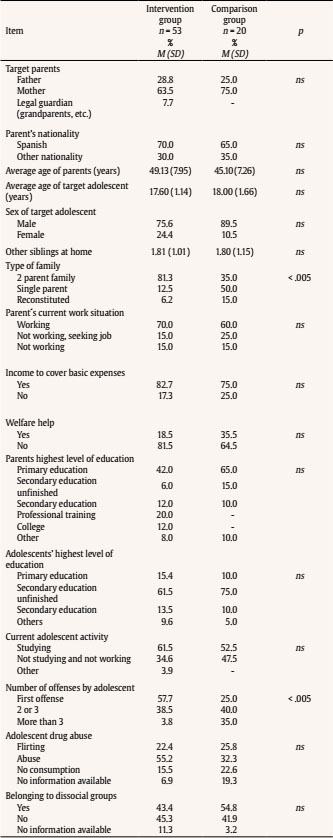

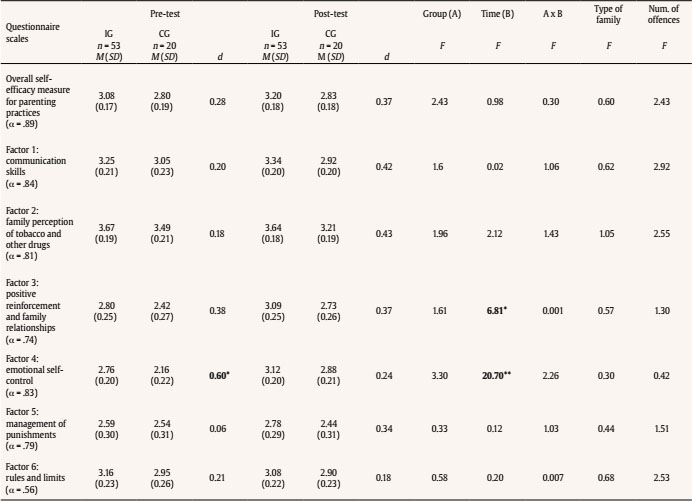

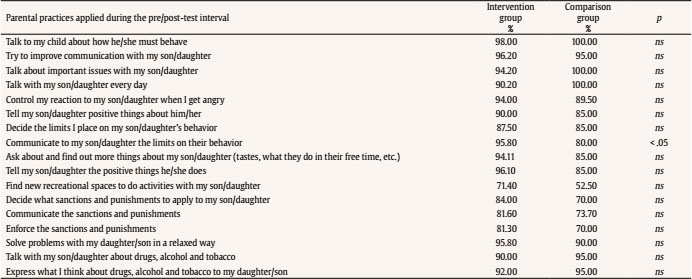

Introduction Social changes in the dynamics of family life have led to European Union (EU) governments to become aware of the need to respond to and support families in developing positive transition and adaptation processes for their internal dynamics (Martínez González & Becedóniz Vázquez, 2009). This resulted in the Committee of Ministers of the Member States of the EU dictating Recommendation 19 in support of the development of positive parenting (Council of Europe. 2006), highlighting those activities which promote positive parenting as a set of behaviors based on the best interests of the child (upbringing, empowerment, non-violence, setting limits), which in turn allow the child to develop fully and achieve better outcomes at home, at school, with friends, and in the community. As underlined by Martínez and Becedóniz (2009), the EU recommends that positive parenting practices be promoted and supported through institutional services and educational programs. The structured training of family members has proven to be effective in reducing disruptive behavioral problems in young people (Axberg & Broberg, 2012; Fletcher, Freeman, & Mathey, 2011), showing that it is possible to modify educational skills and therefore teach family management skills as well as train them. As Letarte, Normandeau, and Allard (2010) noted, the primary agents of socialization for children and young people with difficulties are their families, so it is essential to examine which types of intervention can provide these families with effective support. Martín-Quintana et al. (2009) identified three different generations of group programs for promoting parenting skills. First generation programs emphasize the quality of parenting patterns in providing a supportive and stimulating environment for children’s development. Second generation programs, consisting of bidirectional programs, emphasize the quality of parents’ and children’s interactions in daily activities, attachment, empathy, setting limits, and managing inappropriate and/or aggressive behaviors. Third generation programs seek to improve quality in how the family system functions through comprehensive, durable, multidomain, and multicontext actions. With regard to training parents, the authors refer to three models: academic, managerial, and experiential model. In the international context, Sanders, Kirby, Tellegen, and Day (2014) identify several parental training programs, shaped according to different formats, theoretical approaches, training methods, intensities, and durations (McConnell, Breitkreuz, & Savage, 2012), including “The Incredible Years” (Webster-Stratton, 1998), “Parent Management Training - Oregon Model” (PMTO; Forgatch & Patterson, 2010), “Parent-Child Interaction Therapy” (Fernandez & Eyberg, 2009), “The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program”- especially at levels 4 and 5 - (Sanders, 2012), all of which have different formats. In Spain, multidisciplinary preventive programs targeting different types of needs in different contexts have been developed. Methodologies are often bidirectional, experiential, in-group, active, and participatory. The following programs are worth highlighting in this respect: “Program Guide for the development of competencies” (Ministry of Social Affairs; Martínez González, 2009) and “Program of educational interventions and family” (Bartau & De la Caba Collado, 2009), as second-generation programs, and “Programa de Apoyo Personal y familiar” (Martín, Máiquez, Rodrigo, Correa, & Rodríguez, 2004) and “Aprender Juntos, crecer en família” (Amorós, Balsells, Mateos, Jose & Vaquero, 2014) as third-generation programs. In Catalonia, the Department of Health and Justice has developed and applied “Limits”, a second-generation program (Larriba, 2010). Several authors warn that many of the programs have been poorly evaluated (Letarte et al., 2010; Rodrigo, Martín, Cabrera, & Máiquez, 2009) and a significant proportion of evaluated programs display significant methodological limitations: very few use control groups (Lundahl, Nimer, & Parsons, 2006) and they are all aimed at a very limited number of families or at a narrow age gap (Sanders, Markie-Dadds, Rinaldis, Firmani, & Baig, 2007). Also, some studies show little evidence of sustained deterrent effects through strong research designs and multiple site replications (Mihalic, Fagan, Irwin, Ballard, & Elliott, 2004); consequently, they have a limited impact at the population level (Sanders et al., 2014). Mulford, Redding, and Mendoza (2016) note that there are few studies on behavioral parent-training programs aimed at treating justice-involved juvenile populations. Most of the research on parent-training programs is focused on treating disruptive behavior in younger children. Reviews by Letarte et al. (2010), considering several meta-analyses of studies on these programs and their results, indicate that they showed positive effects on parents’ attitudes and behaviors towards their children in families with children with behavioral problems. These programs also seem to be effective for these children. Parents’ sense of competence or self-efficacy has been one of the factors used in program evaluations (Gilmore & Cuskelly, 2008), with differences being found between mothers and fathers in this issue (Fletcher et al., 2011). Letarte et al. (2010) showed a positive impact on parental practices and the perception of infant behavior (perceiving less and less frequent disruptive behaviors in children) but not in the expression of clear expectations or self-efficacy (which seems to take longer, especially in difficult interaction paths between parents and children). They also noted that families preferred to participate in group programs rather than in individual therapy. Axberg and Broberg (2012) highlighted the positive results when emotional communication skills, positive interaction with children or young people, and consistency in discipline have been taught. Research from the “The Incredible Years” program in Sweden has shown positive results in reducing disruptive behavior in contrast with the group in the waiting list, one year after the completion of the program. Webster, Gaspar, and Seabra-Santos (2012) showed the results of the program when adapted to the Portuguese context – after it had been successfully adapted to UK, Ireland, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and Holland – noting how research has shown that early intervention is the key to addressing problems and that actions during the adolescent period have limited effect, especially when aimed at criminal or aggressive behaviors or secondary risk factors (school failure, absenteeism, and substance abuse). Salari, Ralph, and Sanders’ (2014) evaluation of the Positive Parenting Program for Parents of Teenagers reported a decrease in teen disruptive behaviors, a reduction in the negative impacts associated with teen difficulties, and a greater improvement in parent-child relationships. The intervention was also associated with a greater reduction in using coercive parenting strategies. Taylor et al. (2015) evaluated The Adolescent Parent Ways program for parents of youths experiencing social behavioral issues, focusing on enhancing parent-adolescent relationship quality and on the increase of parental knowledge regarding adolescent development, monitoring of adolescents, and reduction of parent and adolescent stress. It also showed improvements in the overall parent-adolescent relationship. Simoes, Fonseca, and Anglin (2014) also identified a high level of satisfaction among professionals applying these programs; Taylor et al (2015) demonstrated some advantages that result from having multiple group sessions with other parents led by trained group leaders. Parents reported lower levels of perceived stress during post-testing, indicating that the in-person parent training resulted in overall improvements in relationship dynamics and well-being for parents. The assessment carried out by Bartau & de la Caba Collado (2009) in Spain identified improvements in the understanding of children’s needs, parenting skills, children’s emotional development and family relationships, as well as in children’s awareness of parents’ difficulties in taking care of them. More recently, Martínez-González, Rodríguez-Ruiz, Álvarez-Blanco, and Becedóniz-Vázquez (2016) reported that after participating in the Program-Guide with children aged from 1 to 18 years old, participants perceived themselves more competent as parents in all five dimensions analyzed (emotional self-regulation abilities, self-esteem and assertiveness, communication strategies, conflict resolution strategies and coherent limits, norms and consequences strategies). As Mulford et al. (2016) underlined, several characteristics moderate the effectiveness of parent-training programs: socio-economically disadvantaged families, single parent families, and families lacking social support are less likely to demonstrate gains from these programs. The age of children is also associated with effectiveness, being higher when having younger offspring. These authors also noted that there are relatively few studies of behavioral parent training programs aimed at treating justice-involved juvenile populations. In such cases, results showed beneficial effects on family communication and family relationships but only modest reductions on offending. In short, this article aims to approach an evidence-based assessment of the parent-training program “Limits” developed in Catalonia and implemented in several editions since 2007. Particularly, the evaluation focuses on the effect of the intervention on parents’ self-efficacy and the use of parenting practices and to what extent this was perceived by adolescents and facilitators. In light of that, some improvements and recommendations are suggested to improve the program and its implementation. The article gives evidence on the first rigorous evaluation process of the “Limits” program in the frame of public administration accountability, where few such evaluations have been attempted. As Slavin (2008) and Spiel (2009) indicated, an evidence-based assessment uses research and theory to guide the evaluation in all its phases. This article provides some preliminary evidence that contributes to the “Limits” program as potentially being an evidence-based program. Evaluation Plan and Intervention of “Limits” The “Limits” program (Larriba, 2010) is a second-generation bidirectional parenting program (Martín Quintana et al., 2009), focused on the quality of parents’ and children’s interactions in daily activities, attachment, empathy, setting limits and managing inappropriate and/or aggressive behaviors. The program targets families with a higher risk of disruptions than other families in the general population. The content of the program is based on the social development approach (Mulford et al., 2016), and is also based on the research on parent training and parenting skills (Mulford & Redding, 2008) and on the support and control dimensions in parenting (Hoeve, Dubas, Eichelsheim, van der Laan, Smeenk, & Gerris, 2009). The “Limits” program is aimed at families with adolescents aged 14 to 16 who are in the juvenile justice system because they have committed an offense, whether proven or alleged. It is addressed to that segment of population identified as being exposed to a particular risk (drug abuse or other behavior problems and risk factors such as poor social adaptation or school dropout). It is a parenting skills training program, selective and preventive in nature, which provides active training in parenting skills (to improve communication skills with their adolescents, the parent-adolescent relationship, strengthen family ties, etc.). The two-month program involves 8 face-to-face weekly group sessions (lasting two hours each) in which different activities are delivered by facilitators: presenting information, conducting exercises, promoting group discussions, and group dynamic, skill practices, etc. The contents are: learning to define change of behavioral goals, communication skills, reducing conflicts and improvement of family relations, establishing norms and limits, supervision, sanctions and family ties, problem solving, family position with regards to tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, and monitoring. Every session includes the delivery of short written support material for parents and the assignment and completion of various tasks to do at home with the aim of applying positive parenting skills and establishing boundaries with adolescents in their day-to-day life. Tasks at home should be practiced during the week, in between sessions. The task assignment is reviewed over the next program session. The program has a 130-page treatment manual in which each session (120 minutes) is clearly explained and protocolled with a very precise timing for every activity, precise explanations, and methodological recommendations. It also includes written information to be delivered to participants. A total of 351 parents have participated in different applications of the “Limits” program across Catalonia since its conception in 2007. The program facilitators are supervised by the Center for Legal Studies and Specialized Training (CEJFE), a Catalan government body reporting to the Department of Justice that provide them with training and technical assistance. CEJFE compiled a protocol to clarify procedures so as to ensure consistency in training and measurement, and also ensured that all ethical requirements were met. MethodA quasi-experimental method using a controlled before-and-after design (Mertens, 2010) was carried out to evaluate the effects of a parenting intervention program, “Limits”, for families of juvenile offenders that has been applied over the past decade in Catalonia, Spain. A nonequivalent comparison group design with multiple informants and mixed (quantitative and qualitative) methodology was used. By comparing the two groups (intervention and comparison groups), the study seeks to answer the following question: Is there any statistically significant difference in parents’ perception of self-efficacy and in the use of parenting practice between the two groups before and after the implementation of the intervention? It is expected to find the “Limits” program helps those families who receive the intervention to improve their perception of self-efficacy and the use of their parenting practices in comparison to those families who do not. Sample Ninety-one parents being monitored by the juvenile justice teams in Catalonia were identified by their caseworker as eligible to participate in the “Limits” program according to different criteria. The participating sample was divided into an intervention group (IG) (n = 60) and a waiting list comparison group (CG) (n = 31). All the families who agreed to participate constituted the intervention group. Meanwhile, those families who did not agree or were not available to participate in the program edition (conflicts with work schedules, other responsibilities, etc.) made up the comparison group and were put on the waiting list to attend a following edition of the program. Therefore, participants in the program condition were compared with their counterparts in reported parenting practices, before and after the intervention. Six parents in the CG were excluded from the analysis as they reported that they had participated in other parenting interventions previously and a further 5 were excluded because they did not do the post-test. Six parents in the IG dropped out of the program or had attended less than 50% of the sessions and 1 did not do the post-test; despite finishing the program, none of them were included in the analysis. The final valid sample for the comparisons pre-post test consisted of 73 parents divided into two groups: the intervention group receiving the program (n = 53) and the comparison group (n = 20). Those 73 parents represented a total 59 families that had participated either in the intervention group (n = 42 families) or were part of the waiting list comparison group (n = 17 families). All parents participated voluntarily. Adolescents also took part in the study and were interviewed (using a single-question survey) to determine their perceptions of their parents’ behavior after the program; 47 adolescents completed the survey after they received prior parental consent (35 from the IG and 12 from the CG). Characteristics of the Families Of the 53 parents that participated on the “Limits” program, 63.5% were mothers, 28.8% were fathers, and 7.7% legal guardians. With regard to the parents’ nationality, 70% were Spanish. The mean age of parents in the IG was 49.13 (SD = 7.95) and their adolescents’ was 17.6 (SD = 1.14). The distribution by gender was 75.6% boys and 24.4% girls, with a mean of 1.8 (SD = 1.01) siblings. Almost half of the parents in the IG (42%) had at least primary education, while over 60% of their adolescents had not completed secondary; 70% of the parents reported having a job and 18.5% said they received welfare benefits; 81.5% reported having enough income to sustain themselves and their family. The CG had similar socio-demographic characteristics to the IG and their adolescents were also involved in the juvenile justice system. There were no significant differences between IG and CG with regard to demographic data (see Table 1), except for the type of family variable: in the IG, the majority consisted of two-parent families (81.3%) while half of the parents in the CG consisted of single-parent families (50%), χ2(1, 73) = 21.352, p =< .0005. Most of the target adolescents in the IG were studying (61.5%), although 34.6% were neither working nor studying. The target adolescents in the IG presented several problems associated with dabbling with drugs and/or drug abuse (77.6%), and belonging to dissocial groups (43.4%). There were no significant differences between IG and CG with regard to the target adolescent’s situation (see Table 1), except for the number of offenses: more than half of the adolescents (57.7%) in the IG had committed only one offense, whereas the percentage of adolescents in the CG who had committed either 2 or 3 (40%) or more than 3 (35%) offenses was higher than in the IG (38.5% and 3.8%, respectively), χ2(1, 73) = 14.906, p =< .005. Fidelity and Program Adaptation A total of 16 professionals selected from the Catalan Justice Department’s specialized teams (EMO: Equips de Medi Obert, open environment intervention teams, and SMAT: Serveis de Mediació i Assessorament Tècnic: mediation and technical advice teams) implemented the program according to agreed standards, leading a total of 9 groups in 2013. All the professionals took a training course, provided by the Catalan Administration, to ensure adherence and consistency in the implementation of the program and also the quality of delivery to make it effective. They were trained in the core components of the program as well as in the procedures on how to implement it. First-time caseworkers (facilitators) who implemented the program were monitored by another member of the team with previous experience of its implementation to provide corrective feedback and promote positive outcomes (delivering the prescribed content and activities, engaging participants in the session, using appropriate methodology, etc.). Those behavioral observations provided a more objective assessment of the program implementation and decreased the risk of having large deviations from the original content of the program. Also, facilitators were asked to complete a checklist after every session using direct observation in order to: a) compare participants’ changes in program outcomes in each session, b) capture participants’ responsiveness to and attendance at the program, and c) control adherence to criteria established in program implementation. All professionals involved (those who implemented the program and those who only did the referrals) also received a full day’s training provided by researchers at the university in order to consistently apply all data sources and protocols to both groups (IG and CG) during program implementation. Attendance Parents in the IG attended an average of 7.1 (SD = 1.10) of the 8 planned sessions. Of the 53 parents in the IG, 25 (47%) attended all 8 sessions, 14 (26.5%) participated in 7 sessions, 9 (17%) participated in 6 and 5 (9.5 %) in 5 or fewer sessions. Participants attending less than half of the sessions were excluded from the analysis. When parents missed a session, the professional had a meeting with them to explain the content missed in the previous session. It was also ensured that all ethical requirements were met. All participants signed a written consent form and data was delivered anonymously to researchers so as to preserve confidentiality and participants’ anonymity. Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics and Target Adolescents Profile  Note. ns = non-significant. Measures To measure the results of the intervention, different data sources were designed and used to collect data from the perspective of the different agents involved (parents, adolescents, and caseworkers-facilitators). Use of parenting practices and measure of self-efficacy. An ad hoc questionnaire was created and validated to measure the use of parenting practices and parents’ self-efficacy perception on the practices taught on the “Limits” program. A tailored and versatile instrument was required in order to gather detailed and specific data from the performance indicators of the program. The design of the questionnaire was conducted in four phases: a) revision of literature regarding parent’s self-efficacy and parental practices; b) design of the instrument based on the performance indicators directly related to the program’s objectives; c) revision of the instrument, carried out by 7 experts (4 experts in juvenile justice programs and 3 caseworkers), in terms of relevance and clarity of scales items and dimensions – in line with this revision some changes were made: items deleted, rephrasing other parts, etc. to increase content validity; and d) first application of the questionnaire to a sample of 9 parents (all of them potential participants in the “Limits” program) in order to obtain information about the accessibility of the items and format – this phase generated preliminary information about its internal consistency. After that phase, further improvements were made to the final version of the instrument. Finally, the field work was conducted, and the questionnaire was applied to the participant families to determine the use of parenting and self-efficacy practices of parents and to generate more information with regard to its psychometric properties (validity and reliability). The final questionnaire included 17 items and was divided into two sections: in the first, parents were requested to indicate on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (a lot) how confident they felt about the practices before and after program implementation (internal consistency, alpha = .89). In the second section (on the post-test questionnaire), parents were asked to give a Yes or No response about whether they had used each of the 17 practices over the past two months. An exploratory factorial analysis with varimax rotation was conducted in order to give additional evidence on the internal validity of the questionnaire by exploring the underlying structure and its components. The analysis revealed the presence of a six-factor solution explaining 76.7% of the variance with alphas between .56 and .84 (see Table 2): 1) communication skills (e.g., “I feel I have the skills to tell my son/daughter how to behave”); 2) family perception of tobacco and other drugs (e.g., “I feel I have the skills to tell my son/daughter my opinion about drugs, tobacco and alcohol”); 3) positive reinforcement and family relationships (e.g., “I feel I have the skills to find new recreational spaces to do activities with my son/daughter”); 4) management of punishments (e.g., “I feel I have the skills to decide which punishment to give to my son/daughter”); 5) rules and limits (e.g., “I feel I have the skills to decide which limits to place on my son/daughter’s behavior”); and 6) emotional self-control (e.g., “I feel I have the skills to control my reactions when I get angry with my son/daughter”). Therefore, the results from the psychometric analysis showed that the questionnaire has great potential to determine the use of parenting practices and parents’ self-efficacy in the context of the “Limits” program. Ongoing efforts should provide more conclusive evidence through a confirmatory factorial analysis. A single question survey to the adolescents. A single item was used to triangulate adolescents’ and parents’ perceptions regarding the application of parental practices at home (e.g., “In the last two months, have you noticed a change in your mother and father’s behavior towards you? If so, what changes have you noticed?”). It was validated by a group of three caseworkers who were asked about the relevance and appropriate formulation of the question. Observational checklist of parenting practices by caseworkers/facilitators. The facilitators used this tool in each session to record the changes observed in outcomes and parents’ use of parental practices in their day-to-day lives. Dichotomous responses (e.g., “did the person get involved in the session? did the person try to apply the strategies that he/she had learned in the session?”), rates (e.g., number of sessions attended), and open ended responses (e.g., “which strategies he/she had applied during the session; reasons for not attending the sessions”) were used to systematically collect the relevant information concerning the progress (or lack of it) of the participants in the program. All the questions from this tool were anchored to the specific behavior or activities from the “Limits” program. It was validated by two caseworkers who were asked about the relevance of the items and the usefulness of the instrument. Some changes were made according to their suggestions before its application. Data analysis A descriptive chi-square analysis for socio-demographic data and baseline variables was used. A generalized linear mixed model comparing outcomes of the IG and CG was employed. “Type of family” and “number of offences” (both statistically different between IG and CG) were included in the model as co-variables to control their possible effects on the final parents’ self-efficacy outcomes. As the analysis included more than one parent from the same family we took into account the non-independence of observations considering “family register” as a random factor in the model. A conventional content analysis was conducted using coding categories emerging directly from the text data (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Once the researchers agreed upon and consistency was found in the coding, data was coded and analyzed using a descriptive analysis matrix. ResultsThe results presented here are based on parents’ perceptions regarding their self-efficacy and use of the parenting training practices in their daily lives, together with those of the professionals and the target adolescents. Before describing the results, some relevant features of the sample are described. Effects of Intervention on Parents’ Self-efficacy and Use of Parenting Practices Pre-test comparisons between the IG and CG showed no differences in the measure of parenting self-efficacy within the 6 subscales (program outcomes), so the two groups do not initially differ in the dependent variable. A generalized linear mixed model was performed (Table 2) and the results indicated no significant difference either between the two groups after the intervention on the overall self-efficacy measure and within the 6 subscales, .(1, 73) = 0.305, p = .582. However, a time-effect analysis indicated that the IG improved significantly in terms of self-confidence in 2 of the 6 parental practices performed (gray-colored cells, Table 2). Parents in the IG reported feeling more confident in “giving positive reinforcement and family relationships” and “emotional self-control” as a result of their participation in the program. The CG also improved significantly in these two subscales during the pre- and post-test interval. Therefore, no treatment effects between both groups were observed on parents’ self-efficacy perception. Table 2 Results of Group by Time  Note. IG = intervention group; CG = comparison group. *p < .05, **p < .005. Regarding the use of parental practices, over 70% of the parents in the IG reported applying all the parental practices taught in the program in real life (program outcomes). Parents in the CG performed similarly. However, there were significant differences in the parental practice “communicating limits of behavior” between IG and CG in favor of the IG, χ2(1, 73) = 4.399, p < .05 (see Table 3). Table 3 Use of Parental Practices in Day-to-day Life according to Parents’ Perception  Note. ns = non-significant. However, the strategies least applied in the CG (70%) are those related to deciding, communicating, and enforcing a sanction using the content strictly related to the program, while over 80% of the parents in the IG reported applying them. Adolescents’ Perceptions of their Parents’ Parenting Abilities Forty-seven adolescents responded to the survey (35 from the IG and 12 from the CG); 65.7% of the adolescents from families in the IG noticed positive changes in their parents’ behavior in the previous two months as a result of their participation in the “Limits” program. Most parents were reported to have been more communicative and to have exercised greater self-control after the program: “She is calmer now, and she doesn’t get so angry, she talks to me more.” (case A-047-05-M-I). Some of the adolescents recalled how their parents had tried to establish a closer relationship with them and reinforce them in a positive way: “She gives me more support; our communication has improved.” (case A-072-02-M-I). Some adolescents also noticed that they had had fewer arguments in the previous two months and that the communication and their relationship with their parents had improved in general: “There is more communication. She has improved in everything; there are no arguments and fights like the ones we had before.” (case A-013-02-F-I ). Some also reported that their parents had been more able to establish limits and rules in a more assertive way. Out of the adolescents from families in the CG, 58.3% also noted changes in their parents’ behavior despite their not participating in the program. The reported changes were related to improving communication and greater emotional self-control. However, after applying a chi-square analysis, no significant differences were found between the CG and IG with regard to adolescents’ perceptions. Professionals’ Perceptions of Parents’ Parenting Abilities Some difficulties and aptitudes in applying the parental practices were also observed and reported by facilitators. So, facilitators made some adaptations to some of the components of the program in order to meet participants’ needs and profile better. The information provided by professionals was useful for contrasting adolescents and parents’ feelings of self-efficacy and perceptions of their use of parental practices at home, and for capturing participants’ engagement to the “Limits” program. Following the implementation of the program, facilitators were asked about parents’ level of involvement in each session and their use of parental practices taught in each session during the pre/post-test interval. Sixty-eight percent of the professionals reported that parents increased their overall awareness and capacity to address their adolescents’ behavioral problems after the program. By contrast, other professionals had reservations about parents’ improvement, in some cases reporting that they observed a change in parents’ behavior but had doubts about the true internalization of practices and noting that more time would be necessary to determine the effects of the program. In still other cases, professionals mentioned that change was not possible due to the existence of other serious circumstances regarding the adolescents’ behavior. “He has generated new attitudes and ways of communication with the adolescent, although these were positive from the outset.” (case P-072-02-M-I). “He lacks the time and support to internalize the program and use it.” (case P-020-02-M-I). “We think he needs a continuation to consolidate all the small changes and the awareness he has gained with the group. He shows an interest in putting everything worked on in the sessions into practice, but his son’s problems are bigger than his ability to act.” (case P-007-01-M-I). In general, around 65% of professionals reported that participants displayed a good level of involvement in each session. Regarding the parental practices used during the pre/post-test interval, the professionals reported that the strategies implemented by most participants are related to communication skills and improving family relationships (66% and 64.2% of the participants applying these strategies, respectively). It seems that these skills were the ones attempted most during the pre/post-test interval from the professionals’ perspective, probably because communication is a basic skill found in any kind of interpersonal interaction. To a lesser extent with other strategies implemented by families were those related to setting norms, rules, and limits (62.3%). Strategies related to family problem solving and family position regarding tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs were applied, according to a professional’s points of view, only by a little more than half of the participants. The difficulties and facilitating factors were reported by the facilitators. The characteristics of the person participating in the program, including their attitudes, emotions, and skills, difficulties seeing the problem (due to excessive focus or lack of perception of the problem), and discrepancies and difficulties with their own partner made up the bulk of the problems perceived by professionals. Some characteristics of the adolescents, such as their personality, impulsiveness, reaction to interactions, substance abuse, or persistence in challenging behaviors, were also hindering elements. Finally, the lack of a relationship, and the communication difficulties, were other highlighted elements. “Lack of communication with the partner and discrepancies over criteria.” (case P-073-02-M-I). “The high intake of drugs and the refusal to reach an agreement.” (case P-044-05-P-I). “The lack of a more intensive relationship.” (case P-047-05-M-I). Regarding facilitating factors, professionals emphasized attitudes or attitude change in parents: belief in the possibility of change, awareness of change in oneself and in the adolescent, adolescent’s vision from a new perspective and not only casting blame. The mobilization of parents’ personal characteristics (persistence, perseverance, etc.), awareness of own mistakes, acknowledging the adolescents’ positive features, increasing communication, and sharing space and time all became enhancing elements of a new stage in which both agents recognize and acknowledge each other’s actions and efforts. “Acknowledging the positive changes in the adolescent. Cooperation within the couple to overcome problems.” (case P-005-01-M-I). “Belief in the possibility of change for his daughter and himself.” (case P-018-02-P-I) DiscussionProgram evaluation is complex and many programs do not meet the minimum requirements of evaluation. In the case presented here, in order to overcome some methodological limitations described in previous reviews (Letarte et al., 2010; Rodrigo et al., 2009; Sanders et al., 2007), a set of strategies were included in designing the program evaluation: a comparison group was used and samples of 30 parents or more were expected to be included in CG and IG. Also, the point of view of both facilitators and target adolescents were included in the design as a way of improving the consistency of the results. The evaluation of the “Limits” program revealed no statistically significant differences between IG and CG in the pre-test and post-test measures of parents’ self-efficacy on any subscale. These results are in accordance with those of other evaluations of similar programs addressed at improving parental practices (Letarte et al., 2010). Regarding emotional self-control, both groups showed an improvement after post-test. The fact that both groups used juvenile justice services (basically advising and counseling through interview sessions with the Services of Mediation and Technical Advice - SMAT) may have had a collateral effect on results. The implementation of communication strategies was significantly higher among the IG than the CG. Strategies related to communication were reported as the most widely used in this study. In this respect, the program appears to have had a clear impact on the most basic aspects of relations between parents and adolescents, showing significant differences from the CG. Communication strategies do improve the quality of the relationship with adolescents but do not necessarily affect the application of other skills such as setting rules and sanctions. As communication is the vehicle for the majority of interactions between parents and adolescents, communication strategies are probably the first resource to be mobilized as they can be used in the practice of other parenting skills. The program therefore seems to contribute to the initial implementation of simple strategies that can then provide the basis for deploying other skills. This result is consistent with what Mulford et al. (2016) suggested in their meta-analysis. In accordance with previous studies, it was found that a more prolonged intervention is needed for the program to take effect, particularly when there are difficulties between parents and adolescents (Letarte et al., 2010; Mulford et al., 2016; Webster et al., 2012). The sample presented added difficulties associated with the characteristics of target adolescents: they were older adolescents, flirting with drugs or drug abuse, belonging to dissocial groups and having committed more than one offense. These traits could have an impact on relationships among family members and the lack of communication. As a strategy to triangulate information, the perceptions of the parents, their adolescents and professionals concerning parents’ behavior after participating in the program were considered. Adolescents’ perceptions were in accordance with IG parents’ self-efficacy results reported in the questionnaire with regard to “positive reinforcement” and “self-control”. These two scales showed a significant improvement in the IG as a result of the program. For their part, professionals also perceived an improvement in the IG regarding the acquisition of parenting skills for improving relationships dynamics at home, even though parents’ perceptions tended to be more positive than professionals’ in the use of their parental practices in their day to day lives. Both adolescents and professionals agreed that parents had tried to apply the practices and had improved in them, especially those related to increasing the quality of communication. Professionals emphasized their impression that the program had allowed parents to become aware of their adolescents’ situation and their relationship and tried to apply communication strategies in order to improve the latter. However, their view was more critical in terms of the true internalization of these skills and especially their application in daily home life. However, it is worth noting that the program is aimed at families with adolescents aged between 14 and 16 and is currently being applied to families with adolescents aged 18 on average. This would suggest the need to design and deploy more specialized programs – where prevention would be secondary or tertiary – aimed at the more complex specific problems facing families. If the target adolescent is 18, other issues arise and the program no longer plays a preventive role. In fact, the older the boy or girl, the less effective these kinds of programs (Webster et al., 2012). In his regard, it seems clear, and the results are consistent with this idea, that early intervention is key when the program is aimed at addressing risk factors that become problems over time. There may be limitations in the possibilities of developing such programs in the institutional environment of juvenile justice in the near future and cases will continue to be diverted to the “Limits” program because it is one of the few specific programs that exist and is available to open prison and juvenile justice professionals. To sum up, the program helps raise awareness of problems related to family relationships between parents and adolescents and the need to establish rules and boundaries to promote cohabitation in a framework of respect and effective communication. This awareness can also be related to the results obtained; the program and its evaluation tools generate an effect of awareness that could influence post-test responses as the result of a more critical and sensitive vision of the situations arising in this area. Professionals stated that families were more critical of their respective situations after participating in the program. This effect is attributable to their having answered a questionnaire and has been identified in other spheres, contributing to the idea that people answering a questionnaire become sensitized as an effect of the response process itself (Lajunen & Summala, 2003). Along those lines, the program seems to have a positive impact on improving skills related to communication and improving parents-adolescents relationship dynamics (Mulford et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2015) but fails to achieve its objectives in relation to establishing rules and sanctions. Thus, the evidence seems to suggest that “Limits” is ineffective at changing its primary target behavior. It would seem, as mentioned, that more time is required for interaction and monitoring actions should be incorporated after the program has finished. Finally, and in accordance with that suggested by Chacon, Sanduvete, Portell, and Anguera (2013), it would be important to adapt the participant selection procedure to ensure that participants’ profile matches the aims and features of the program and guarantee its success; findings show that the program was applied to families with adolescents aged 18 on average who had already been exposed to a particular risk, instead of the age range of 14-16 (its original target). There is still a lot of work to be done regarding both the program itself and its evaluation. Nevertheless, this work is a first attempt to draw attention to the need of delving into the evidence based approach to both the practice (program design and implementation) and its assessment as Axford, Elliott, and Little (2012) suggest in relation to the promotion of “evidence-based” programs in children’s services, or more recently Vázquez, Molina, Ramos, and Artazcoz (2017). The program has not achieved its goals, but this evaluation has identified the way ahead. Limitations/Future Research Some limitations emerged from this exploratory evaluation of “Limits”. These limitations need to be considered for a definitive evaluative study of the program and further research using longitudinal designs should be done in order to prove its effectiveness. The use of a homegrown outcome questionnaire rather than a standardized one to measure parents’ self-efficacy could be considered a study limitation. However, one of the reasons to use an ad hoc questionnaire was because it is more versatile to obtain the needed information and adapted to the contents of the “Limits”. Thus, the questionnaire used suggested reasonable construct validity and reliability for parental self-efficacy subscales and the evidence provided corresponded with the measures used in other studies on parental behavior. Even though some strategies were used to ensure fidelity (initial training monitoring, etc.) more methods and data sources to measure fidelity should be used in future research to achieve more accurate and possible stronger results. The groups were not assigned randomly to conditions, but using a quasi-experimental controlled before-and-after study. Nevertheless, it would be desirable to use higher levels of randomization to minimize the risk of contamination from other variables that could bias the intervention effects. However, the initial difference between groups (IG and CG) in different socio-demographic data and baseline variables were considered in the analysis to discern better if the differences observed between both groups were attributed to the intervention and not to this existing profile differences. The initial results showed no significant differences between the IG and CG as they were having equivalent scores in the pretest. Most probably, a longitudinal evaluation design would have identified the true impact of “Limits” in participants. Facilitators were not blind to condition, and that could have an effect on their data on parent success. For similar future research, it could be necessary to consider observational data instead of facilitator perceptions. Another limitation is associated with the nature of measurement (pre/post-test questionnaires). The measures were self-reported and the influence of socially desirable response tendencies should therefore also be considered. That said, the participants were asked to respond sincerely and honestly, so as to minimize inaccurate responses. It would be recommendable to use interviews with the parents to contrast questionnaire response regarding the use/transfer of parenting practices at home or other observational measures. As Hamilton and Carr (2016) stated, self-reported scales are one of the main types of instrument for assessing family. In the context of the “Limits” program, evaluating the transfer of learned skills through self-reported procedures also raised methodological problems, as it is very difficult to know whether the skills learned in the course were being practiced effectively at home. Therefore, there is a double inference: the first arising from the perception of families about their reality and practice, and the second derived from professionals’ reports about what families claim. This double inference, added to the percentage of random error (which may be present in a population of these characteristics), suggests caution should be applied in interpreting the data. Implications and Future Directions According to the evidence presented, some modifications need to be made prior to future implementation or further expansion of the program in order to improve its usability and effectiveness with its target population. It seems necessary to maintain the same initial training for practitioners to ensure program consistency. It would also be desirable to monitor the use of parental practices and parent self-perception of those practices over time or 3 or 6 months after program implementation to verify its durability and provide feedback on the program itself. This follow-up evaluation would also provide evidence on which to base the design and implementation of a set of follow-up programs. Despite the fact that “Limits” was designed as a preventive program addressed at families with some incipient communication and relational difficulties and it is necessary to maintain it as such, the objectives of the program need to be readjusted to make them achievable within 8 sessions. Other authors have already stressed the need to extend the intervention period to find evidence of effectiveness and impact. Some other improvements should also be considered in order to achieve a better cultural and linguistic adaptation to participants’ profile and their context, as suggested for other parental programs addressing specific populations with specific needs (Buzhardt, Rusinko, Heitzman-Powell, Trevino-Maack, & McGrath, 2015; Domenech Rodriguez, Baumann, & Schwartz, 2011). The results of this study have demonstrated the need to design complementary tailored and remedial programs aimed at solving serious and specific problems already detected in the target group (i.e., drug abuse, child-parental violence), for which “Limits” could not address effectively as it is conceived as a preventive program. Finally, it would also be desirable to improve the evaluation system of the program itself and to include it as a core part of the program. Last but not least, it would also be highly advisable to promote the partnership scheme bringing together policy makers, service providers, professionals, and researchers to approach the “Limits” program to the indicators of evidence-based programs (Rodrigo, 2016). Notes 1 This study reports findings from an independent evaluationof the Limits program implemented within the juvenile justiceservices in Catalonia. The authors have no affiliation with thedevelopers or distributors of the “Limits” program. Cite this article as: Martínez-Muñoz, M., Arnau, L., & Sabaté, M. (2018). Evaluation of a parenting training program, “Limits”, in a juvenile justice service: Results and challenges. Psychosocial Intervention., 28, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2018a14 Funding: This study was supported by a grant from CEJFE and Àrea de Medi Obert i de la Unitat de Programes d’Innovació de la Direcció General d’Execusió Penal a la Comunitat i de Justícia Juvenil, Department of Justice, Autonomous Government of Catalonia. |

Cite this article as: Martínez-Muñoz, M. , Arnau, L. , & Sabaté, M. (2019). Evaluation of a Parenting Training Program, “Limits”, in a Juvenile Justice Service: Results and Challenges. Psychosocial Intervention, 28, 1 - 10. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2018a14

Correspondence: Laura.arnau@uab.cat (L. Arnau).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS