Couple Conflict-facing Responses from a Gender Perspective: Emotional Intelligence as a Differential Pattern

[Las respuestas a los conflictos de pareja desde una perspectiva de g├ęnero: la inteligencia emocional como patr├│n diferencial]

María Alonso-Ferres, Inmaculada Valor-Segura, and Francisca Expósito

University of Granada, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a9

Received 14 October 2018, Accepted 6 April 2019

Abstract

Conflicts that arise in romantic relationships can be one of the greatest causes of suffering when they are not faced appropriately. Through two studies, this research analyses the differential effect of gender and the influence of emotional intelligence on conflict-facing responses, as well as their consequences at an individual and relationship level. In Study 1, we examined the existence of gender differences during conflicts through four independent samples of subjects (N = 727). After meta-analysing the results, we observed that women responded more expressively and loyally to conflict, while men had a more negligent response. In our observations in Study 2 (N = 185), emotional intelligence became a key factor in promoting a constructive response to face conflicts that is adopted by both women and men. Moreover, emotional intelligence finally favours their psychological well-being and satisfaction with the relationship. This research shows the importance of emotional skills in confronting conflicts that originate in intimate contexts such as romantic relationships and their consequences to both men and women.

Resumen

Los conflictos que surgen en las relaciones de pareja pueden ser una de las mayores causas de sufrimiento cuando no se afrontan idóneamente. A través de dos estudios, esta investigación analiza el efecto diferencial del género así como la influencia de la inteligencia emocional en el afrontamiento de los conflictos de pareja y sus consecuencias a nivel individual y relacional. En el estudio 1 se examina la existencia de diferencias de género en el afrontamiento de conflictos a través de 4 muestras independientes de sujetos (N = 727). Tras metaanalizar los resultados de las mismas se observa que las mujeres responden de manera más expresiva y leal ante los conflictos, mientras que los hombres emplean una respuesta más negligente. En el estudio 2 (N = 185) se comprueba como la inteligencia emocional se convierte en un factor clave al promover el afrontamiento constructivo de conflictos adoptado tanto por mujeres como por hombres, lo que favorece tanto su bienestar psicológico como la satisfacción con la relación. Esta investigación muestra la importancia de las habilidades emocionales ante los conflictos que se originan en los contextos más íntimos, como son las relaciones de pareja, y sus consecuencias tanto en hombres como en mujeres.

Keywords

Conflict-facing responses, Gender, Emotional intelligence, Psychological well-being, Relationship satisfactionPalabras clave

Afrontamiento de conflictos, G├ęnero, Inteligencia mocional, Bienestar psicol├│gico, Satisfacci├│n con la relaci├│nCite this article as: Alonso-Ferres, M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Couple Conflict-facing Responses from a Gender Perspective: Emotional Intelligence as a Differential Pattern. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(3), 147 - 156. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a9

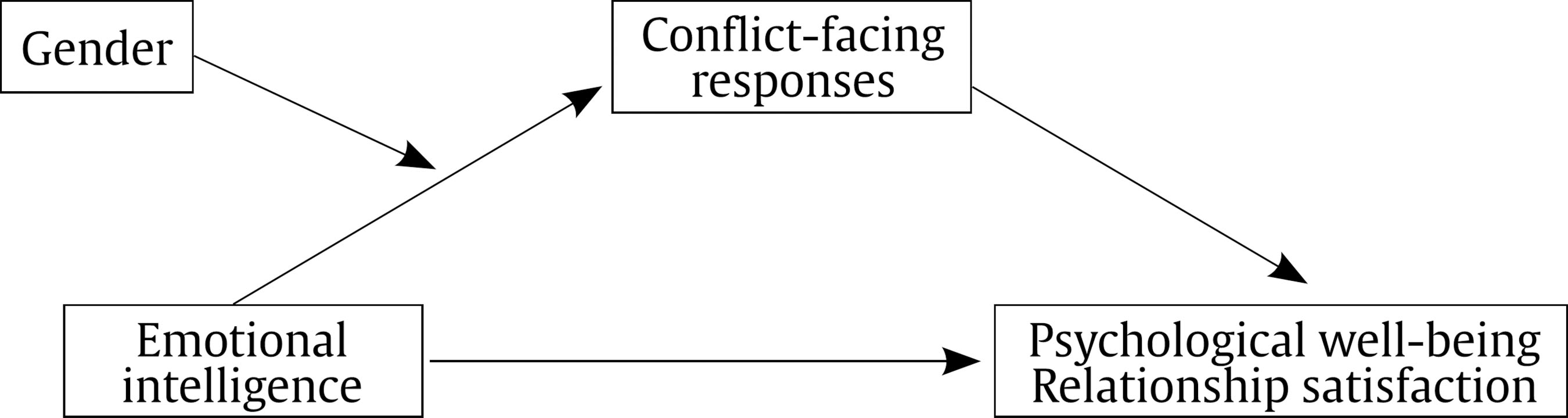

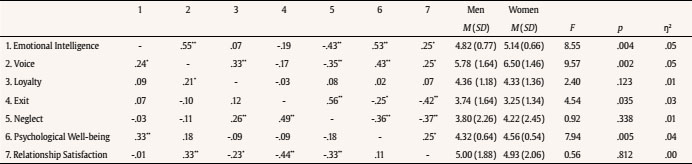

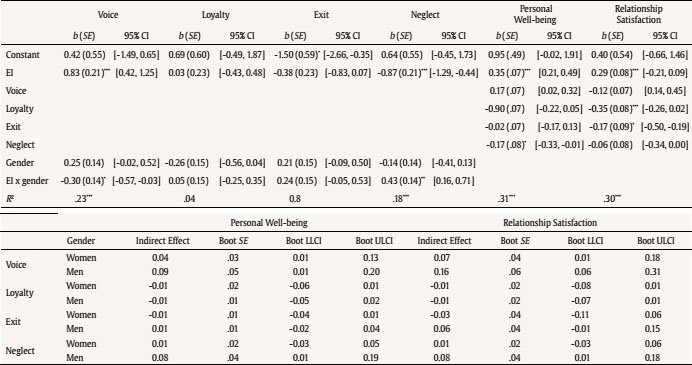

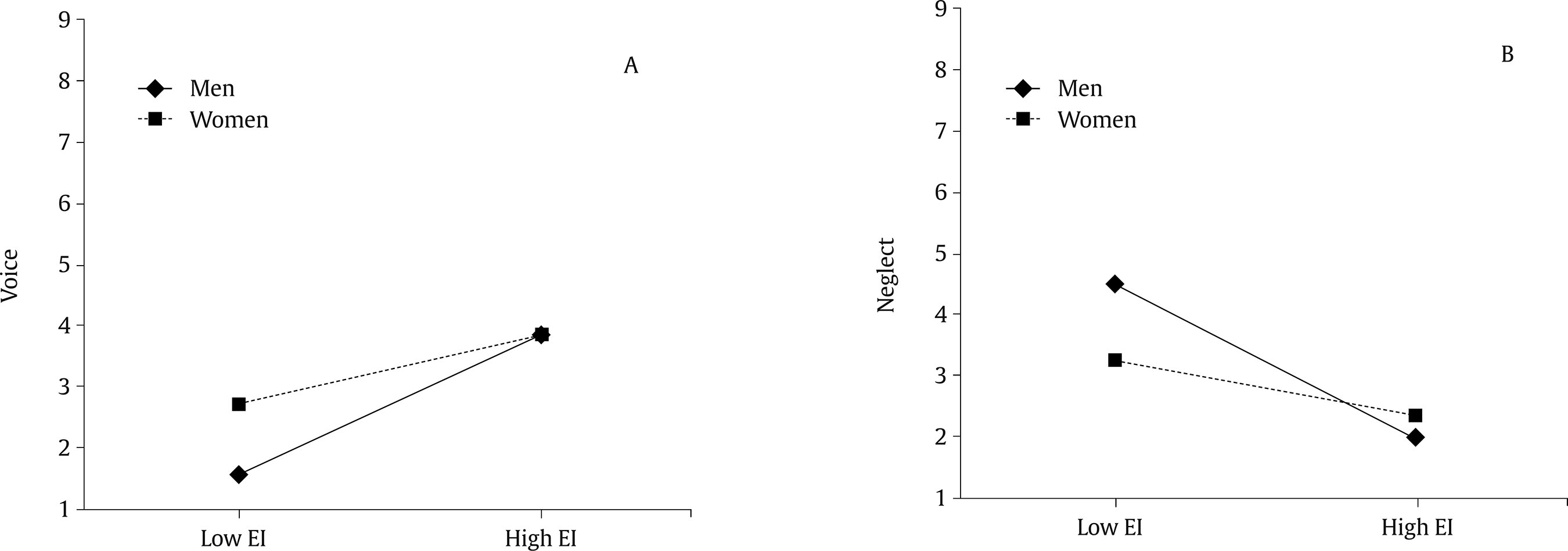

maalfe@ugr.es Correspondence: maalfe@ugr.es (M. Alonso-Ferres).Romantic relationships are an important part of people’s lives. Unfortunately, relationship conflicts are inevitable and risks damaging if they are not adequately addressed (Overall & McNulty, 2017; Valor-Segura, Expósito, Moya, & Kluwer, 2014). Indeed, one of the key issues couples identify is how to face their discussions, and relationship therapists have said that problematic conflict resolution is the most challenging relationship problem to treat (Geiss & O’Leary, 1981; Overall & McNulty, 2017). For these reasons, one of the most relevant theoretical and applied goals in the field of close relationships is to study the strategies that people can use to manage conflict (Garrido-Macías, Valor-Segura, & Expósito, 2017; Valor-Segura et al., 2014). In the present research, we thus aimed to make this knowledge grow. Specifically, we seek to answer two questions. First, what types of strategies do men and women (differently) use to manage conflict in their romantic relationships? Second, may individuals’ emotional intelligence shape women and men conflict-facing responses and, in turn, their personal and relational consequences? To answer these questions, we analyse the different responses women and men can use to face romantic conflicts (Study 1) and test a model—described in more detail in the following sections—examining whether gender moderates the association of emotional intelligence and conflict-facing responses impacting in turn, their psychological well-being, and relationship satisfaction (Study 2). A Conceptual Model Linking Emotional Intelligence, Couple Conflict-facing Responses, and Their Outcomes from a Gender Perspective The primary focus of the present research is on understanding which types of responses people could adopt to face conflicts. Rusbult, Johnson, and Morrow (1986) established a clear framework for investigating the responses to problems in romantic involvements and the consequences of those responses by proposing a typology of different conflict-facing strategies. They specifically made a distinction between constructive and destructive responses when facing conflicts. Constructive responses help to maintain the relationship and can manifest in two types: (a) “voice”, an active response that promotes the discussion of problems to find a solution (e.g., suggesting possible solutions or freely communicating with others), and (b) “loyalty”, a passive response characterised by cooperative behaviours (e.g., waiting for the relationship to improve, supporting the partner unconditionally, or minimizing the problems). Destructive responses refer to hostile behaviours that convey negativity, spur competition, or damage the relationship. They come in two types: (a) “exit”, an active response that promotes a relationship’s destruction (e.g., separating or filing for divorce), and (b) “neglect”, a passive response that allows a relationship’s deterioration through control and opposition behaviours (e.g., abuse, threats, insults, or criticism; Overall & McNulty, 2017; Overall, Sibley, & Travaglia, 2010). Although problem-solving strategies have been widely investigated, the factors that explain the origin of particular style formation in the context of romantic relationships are still unclear. Based on previous evidence which, separately, has suggested the relevance of participants’ gender and emotional intelligence in romantic situations (O’Connor, Izadikhah, Abedini, & Jackson, 2018; Smith, Heaven, & Ciarrochi, 2008; Stolarsky, Postek, & Smieja, 2011), in the present research we have focused on studying these variables as a determinant factor for conflict management. Gender and Conflict-facing Responses Here we draw from diverse theoretical perspectives on gender—such as evolutionary psychology perspectives (Trivers, 1972), and the social role theory (Eagly & Wood, 2012)—to propose, secondary focus of the present research, an underlying argument that men and women are willing to face differently their relationships conflicts. For example, evolutionary psychologists argue that females are more willing to behave constructively to maintain their relationship that provide them the resources to raise their limited offspring. Conversely, ancestral males seek to increase paternity certainty by (a) mating with many females or (b) controlling women through neglect responses (Midlarsky & Rosenzweig, 2018). The social role theory goes one step further and build in this knowledge adding that—beyond evaluative learning processes—sex differences in social behaviour (e.g., conflict-facing responses) arise from how men and women are educated into the distribution of social roles within a society (Biernat & Sesko, 2018; Wood & Eagly, 2002). Specifically, it is suggested that men are usually socialised to be independent and to confront a threatening condition, such as a couple’s conflict, directly, aggressively, or coercively (Ellemers, 2018; Holtzworth-Munroe, Stuart, & Hutchinson, 1997). Conversely, women, who are usually educated in traditional gender roles, are encouraged to be communal, expressive, and dependent. Therefore, they are expected to be cooperative and concerned about relationship maintenance, behaving loyally during interpersonal conflicts (Birns, Cascardi, & Meyer, 1994; Horne & Johnson, 2018; Wood & Eagly, 2002). Supporting this view, Valor-Segura et al. (2014) observed how, after experiencing a conflict situation with their partners, women were more likely to remain loyal to their partners, whereas men were more likely to show a greater aggressive response. However, Holt and DeVore (2005), after meta-analysing 36 empirical studies, found no gender differences in the intention of leaving an interpersonal relationship (exit). Emotional Intelligence and Conflict-facing Responses: Links to Gender While a normal part of intimate relationships, conflict is often a source of stress and emotions for couples. Thus, in addition to gender contextualization, social and emotional insight may be part of the skill set that helps couples handle conflict in healthier ways (Stolarsky et al., 2011). Therefore, the third focus of the present research is on the potential link between emotional intelligence (EI) and four conflict-facing responses. Emotional intelligence is a recently developed concept defined by Mayer and Salovey (1997, p. 10) as “the ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotion; to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth”. Since its introduction by Salovey and Mayer (1990), EI has been the subject of much empirical work studied from different perspectives and thus, measured by different instruments. Depending on that, EI literature has been divided into three models: 1) the performance-based ability model understands EI as a form of intelligence based on emotional aptitudes that implies the reasoning about our emotions using emotional problems with a set of correct and incorrect responses (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 2016; Mayer, Salovey, y Caruso, 2002); 2) the self-report ability model, like the performance-based ability model, understands EI as a form of intelligence based on emotional aptitudes, but uses self-reports to measure the construct, and participants have to estimate subjectively their own EI (Extremera, Rey, & Sánchez-Álvarez, 2019); 3) finally, the self-report mixed model also measures EI with self-report instruments, but it understands EI as a broad construct that includes personality factors, mental abilities, and motivation instead as a form of intelligence (Bar-On, 2004; Gómez-Leal, Gutiérrez-Cobo, Cabello, Megías, & Fernández-Berrocal, 2018). Because emotional skills are essential for establishing effective social interactions, it is reasonable that emotional intelligence is frequently linked to adequate social functioning (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Accordingly, the literature has shown that adequate emotional management, assessed both as ability and as trait, seems to play a crucial role in constructive responses adopted in social interactions like conflicts (Schutte et al., 2001; Zeidner, Kloda, & Matthews, 2013). Nevertheless, while most studies have focused on the organizational and educational field (Schlaerth, Ensaril, & Christian, 2013; Vashisht, Singh, & Sharma, 2018), to our knowledge, relatively few studies have explored how EI shapes romantic interpersonal conflict management. We thus propose that interpersonal conflicts can be highly emotional experiences—often characterized by intense feelings and reactions. As EI reflects the extent to which individuals are emotionally and cognitively aware of their partners’ goals and constructively use emotions in social interactions (Salovey & Mayer, 1990), it is expected to play an important role in shaping individuals’ conflict behaviour within their romantic partner. This prediction is supported by some few empirical studies that demonstrate a positive relationship of EI with interpersonal functioning (Brackett, Rivers, & Salovey, 2011). For example, based on the EI performance-based ability model, Stolarsky et al. (2011) found among heterosexual couples that higher EI ability would result in the use of constructive and active resolution strategies that are assumed to be healthier in relationships. In the same line, Zeidner and Kloda (2013) and Zeidner et al. (2013) examined how both, EI ability and trait, are linked to a positive conflict resolution. Moreover, Lopes et al. (2004) noted that people with greater EI ability tend to inhibit behaviours that are negative or destructive. Likewise, the role of EI in the positive conflict resolution as a form of marital quality among married couples was found based on EI self-report mixed model (Batool & Khalid, 2012; Monteiro & Balogun, 2015; O’Connor et al., 2018). Because no existing research in the romantic field, to our knowledge, has tested these associations using the self-report ability model, and self-report measures of EI have demonstrated utility in predicting various psychological and emotional outcomes (Law, Wong, & Song, 2004; Wong, 2015), for the purposes of this study, EI is conceptualized using the self-report ability model. Specifically we suggest that, following this perspective, a higher level of emotional perceived abilities would also allow people to better face a conflict situation. Nevertheless, might the utility of emotional abilities described above—and their association to conflict management—differ for men and women? Previous studies in the literature have revealed gender differences in EI—indeed women score higher than men in the main factors of EI (Cabello, Sorrel, Fernández-Pinto, Extremera, & Fernández-Berrocal, 2016; Fernández-Berrocal, Cabello, Castillo, & Extremera, 2012). However, several studies suggest that this gender effect vary across EI measures and dimensions (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2012; López-Zafra & Gartzia, 2014). For example, a meta-analysis of studies involving 30,077 people showed higher EI for women in performance based EI tests, but they found no average sex-related differences for self-report ability EI tests (Joseph & Newman, 2010). In contrast, López-Zafra and Gartzia (2014) found gender differences across dimensions for self-report ability EI tests. In addition to not having a single pattern in EI gender differences, previous research that has separately analysed the association between EI and romantic conflict resolution in men and women revealed unclear conclusions. While some studies showed that, according to traditional female stereotypes, higher EI was associated with the use of constructive conflict management strategies (voice and loyalty) for women but not for men (Stolarsky et al., 2011), other studies found that EI is positively linked to an active positive conflict resolution (voice) in both men and women (Batool & Khalid, 2012; Brackett, Warner, & Bosco, 2005; Zeidner & Kloda, 2013; Zeidner et al., 2013) and negatively to the passive destructive conflict resolution (neglect) in men (Brackett, Mayer, & Warner, 2004). These unclear patterns guided us to study—as the fourth focus of the present research—if participants’ gender could be a variable that moderates the effect of EI on romantic conflict-facing responses. Psychological Well-being and Relationship Satisfaction as Model’s Outcomes The fifth focus of the present research is on studying the personal and interpersonal consequences of both EI and conflict-facing responses. On the one hand, the significance of both EI and conflict management styles in a person’s psychological well-being—a set of positive cognitive and affective evaluations that people make of their own lives (Díaz et al., 2006)—has separately been documented. For example, the preferential use of an active conflict-facing response (i.e., the communication of one’s own needs) seems to favour personal well-being (Marroquín, Tennen, & Stanton, 2017). Moreover, EI has been considered an indicator of psychological adjustment (Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016). In this line, Sánchez-Álvarez, Extremera, and Fernández-Berrocal’s (2016) meta-analysis showed how high EI individuals who can perceive, express, understand, and regulate their emotions and thus have a positive interaction with others, possess a greater state of psychological well-being. On the other hand, conflicts that arise in intimate relationships, as well as responses that people may adopt to face them, could also have interpersonal consequences, such as affecting the level of satisfaction with the relationship (Falconier, Jackson, Hilpert, & Bodenmann, 2015; Schutte et al., 2001). Several studies have shown the correlation between conflict-coping responses and satisfaction with the relationship (Bradbury & Karney, 2010; Smith et al., 2008). Specifically, couples who openly discuss their problems (i.e., a constructive conflict-facing response) seem to have a higher level of satisfaction with their relationship (Overall & McNulty, 2017). Likewise, EI is a construct that helps people maintain these positive interactions and, therefore, be more satisfied with their relationships (Lavalekar, Kulkarni, & Jagtap, 2010; Malouff, Schutte, & Thorsteinsson, 2014). For example, it has been noted that couples who were the most satisfied with their relationships were those who used an adaptive response to face their problems and classified their partners as having greater EI (O’Connor et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2008; Zeidner et al., 2013; Zeidner & Kloda, 2013). The Present Research Based on the previous notions that (a) there are different ways to face romantic conflicts, (b) people characteristics (e.g., gender and EI) may shape the way they resolve conflicts, and (c) the response people adopt to a romantic conflict affects their own well-being as well as the quality of the relationship, the main goal of the present research is to explore the underlying factors that explain the origin of particular style of romantic conflict responses and their effects at both a personal and relationship level. To do so, in Study 1 we firstly categorized responses that are adopted in romantic-relationship conflicts based on participants’ genders. For that purpose, we analysed gender differences in the conflict-facing responses of four independent samples of subjects. Specifically, we expected women to use voice (Hypothesis 1a) and loyalty responses (Hypothesis 1b) more often than men. In contrast, we expected men to use more neglect responses compared to women (Hypothesis 1c). Conversely, we did not expect gender differences in the exit response (Hypothesis 1d). Following Goh, Hall, and Rosenthal (2016), we carried out a mini meta-analysis of the previous results to provide more solid and replicable evidence of this research goal. In Study 2, we aimed to completely analyse our conceptual model (see Figure 1 for graphical representation), that is, if the EI is associated to an adaptive conflict-facing responses, favouring in turn their psychological well-being and satisfaction with the relationship (Hypothesis 2). Moreover, given the unclear conclusions in the literature, we explore whether participants’ gender moderates the relation between EI and conflict facing-responses through two moderated mediation models. Figure 1 Conceptual Model Showing the Proposed Relationship between Emotional Intelligent and Well-being or Relationship Satisfaction as Mediated by Conflict Styles Resolution (Voice, Loyalty, Exit, and Neglect), Moderated by Gender.  On the basis of previous findings that suggest a superior conflict-facing ability in EI individuals, we first expected to find that greater EI will be positively related to the use of the active constructive response (voice; Hypothesis 2a) and negatively related to the use of the active destructive response (exit; Hypothesis 2b) in romantic-relationship conflicts in both men and women, that is, independently of participants’ gender. This would correspond to a better psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction. Second, based on traditionally gender roles education—previously described—we also anticipated there would be a positive relation between EI and the passive constructive response (loyalty; Hypothesis 2c) to romantic conflicts only in women, whereas there would be a negative relation between EI and the passive destructive response (neglect; Hypothesis 2d) during romantic-relationship conflicts in men, both of them resulting in a better psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction. Study 1 Method Sample. We employed four independent samples to analyse the existence of gender differences in couple conflicts (N = 727). Sample 1. The first sample consisted of 221 participants (115 women and 106 men) from the general population. The average age of the participants was 34.72 (SD = 11.09); they had been involved in their relationships for an average of 10.91 years (SD = 10.57). In the sample, 41.2% of the participants were dating, whilst 21.7% were cohabiting and 37.1% were married. Sample 2. The second sample consisted of 159 participants (81 women and 78 men) from the general population. The average age of the participants was 27.69 (SD = 9.93); they had been involved in their relationships for an average of 6.19 years (SD = 8.14). In the sample, 59.1% of the participants were dating, whilst 20.1% were cohabiting and 20.8% were married. Sample 3. Sample 3 recruited 162 participants (108 women and 54 men) from the general population. The average age of the participants was 28.4 (SD = 10.94); they had been involved in their relationships for an average of 7.04 years (SD = 8.97). In the sample, 62.3% of the participants were dating, whilst 14.9% were cohabiting and 22.8% were married. Sample 4. For sample 4 we recruited 182 participants (108 women and 74 men) from the general population. The average age of the participants was 29.80 (SD = 11.01); they had been involved in their relationships for an average of 1.39 years (SD = 8.22). In the sample, 36.4% of the participants were dating, 21.4% were cohabiting, 22.9% were married, and 19.3% answered based on a previous relationship. Procedure. The total sample was recruited through two incidental sampling procedures at different times to obtain a greater variability of the sample. In samples 1 and 3 participants were assessed in different public locations (e.g., local transportation stations) in a Spanish city. Data from samples 2 and 4 were collected using an online questionnaire through the Qualtrics’ platform. A trained evaluator requested participants’ collaboration to use paper-pencil (samples 1, and 3) and informed them about the main objective of this research, the questionnaire’s estimated duration (approximately 10 min), and the agreement with the principles of confidentiality and anonymity regarding their responses. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaire booklet individually. Specifically, they had to vividly describe in writing a conflict situation that they had experienced with their intimate partner in the previous 6 months using the critical incident technique (Flanagan, 1954). After recalling and briefly writing about this incident, the participants had to complete the rest of the measures of interest. In the online administration (samples 2 and 4), the same information and requirement were included. Previous research indicated that data produced online are as reliable and valid as data produced through paper-pencil (Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004). Finally, participants were debriefed and thanked. All participants were volunteers, provided informed written consent and were provided with no monetary incentives for their participation. This study is part of a research project approved by the ethical committee of the University of Granada. Measures. The measurements used in the four samples relied on the scale of accommodation among romantic couples (Rusbult et al., 1986; Valor-Segura et al., 2014) and socio-demographic characteristics. The Accommodation among Romantic Couples Scale. Participants were then asked to report how they responded to the described conflict situation with their partner (“When that problem occurred . . .”) using the Accommodation among Romantic Couples Scale (Rusbult et al., 1986; Valor-Segura et al., 2014). This measure was selected because it was based on the framework for investigation of responses to problems in romantic involvements from which we develop our hypotheses. The scale includes 28 items ranging from 1 (never does that) to 9 (always shows that type of behaviour). It is composed of four conflict-facing dimensions: (a) voice (e.g., “I told my partner why I was upset”), (b) loyalty (e.g., “My partner treated me inconsiderately although I did not take it into account”), (c) exit (e.g., “When I am very upset with my partner, I think about terminating our relationship”), and (d) neglect (e.g., “When I am really angry, I treat my partner badly. For example, I do not take it into account or I tell him cruel things”). Table 1 shows the alpha coefficient of each variable in each of the samples. Socio-demographic characteristics. We gathered information about gender, age, marital status, and duration of the relationship. Results Gender differences in facing conflicts. We calculated gender differences in conflict-facing responses using independent t-tests for each sample (Hypotheses 1a, 1b, 1c, and 1d). The participants’ gender was used as independent variable, while voice, loyalty, exit, and neglect responses were used as dependent variables. The results are presented in Table 1. We arbitrarily coded gender as 2 for male and 1 for female. Any effect size (Cohen’s d) with a positive value would therefore indicate that men had a larger use of the response, and any effect size (Cohen’s d) with a negative value would indicate that women had a larger use of the response. Specifically regarding women, the results showed that women tended to have greater voice responses in samples 1 and 2, as well as greater loyal responses in samples 1, 2, and 3. Regarding men, we found a greater use of exit responses in sample 4 and a greater use of neglect responses in samples 1, 3, and 4. Table 1 Gender Differences in Conflict-facing Responses (Study 1)  Note. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) with a positive value indicate that men have a larger use of the response, and any effect sizes with a negative value indicate that women have a larger use of the response. Mini meta-analysis. In order to obtain more solid and replicable evidence of gender differences in conflict-facing responses, we conducted a meta-analysis of our four studies using fixed effects, in which the mean effect size (Cohen’s d) was weighted by sample size. Overall, the effect was negative and highly significant for voice, Md = -0.32, Z = -4.09, p < .001, 95% CI[-0.47, -0.16], and loyalty, Md = -0.77, Z = -9.25, p < .001, 95% CI[-0.94, -0.61], such that, consistent with Hypotheses 1a and 1b, women had a higher use of voice and loyalty as conflict-facing responses than men. Moreover, the results showed a positive and significant effect for neglect, Md = 0.28, Z = 3.57, p < .001, 95% CI[0.13, 0.44]. In other words, men had a higher use of neglect as a conflict-facing response than women, consistent with Hypothesis 1c. Finally, no significant effects were found regarding the exit response, Md = 0.05, Z = 0.59, p = .277, 95% CI[-0.11, 0.20]; therefore, there were no gender differences when it came to the abandonment of a relationship (Hypothesis 1d). Study 2 Method Sample. A total of 200 participants from the young general population who were involved in a romantic relationship at least 6 months participated in the study. Of those participants, 15 were excluded because they did not complete the main measures. Hence, the final sample consisted of 185 participants (99 women and 86 men, Mage = 20.01, SD = 2.71), having been involved in their relationships for an average of 1.85 years (SD = 1.67). In the sample, 49.7% of the participants were dating, 3.8% were cohabiting, and 46.5% answered based on a previous relationship. Procedure. The sample was obtained using the procedure described for Study 1 (samples 1, and 3), in which participants were assessed in different public locations (e.g., local transportation stations) and university centers (e.g., libraries) in a Spanish city. The participants provided informed written consent, and then, individually completed the questionnaire (conflict description and study measures) in a study with a pre-experiment design (Montero & León, 2015). After that, participants were thanked and provided with information about the study. No reward was offered for participation. Like in the previous study, this experiment is part of a research project approved by the ethical committee of the University of Granada. Measures Emotional intelligence. The Wong and Law’s Emotional Intelligence Scale (Extremera et al., 2019) was used to evaluate self-report participants’ ability emotional intelligence. The scale includes 16 items ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree), that refer to the perception, understanding, and regulation of own and others’ emotions (e.g., “Most of the time I can distinguish why I have certain feelings”); α = .84. Psychological well-being. A Spanish adaptation of Ryff’s Psychological Well-being Scales (Díaz et al., 2006) was used to evaluate participants’ well-being. This scale includes 29 items rated on a range from 1 (completely disagree) to 6 (completely agree; e.g., “In general, I feel safe and positive about myself”); α = .88. Satisfaction with the relationship. The Relationship Assessments Scale (Hendrick, 1988) was used to evaluate the participants’ satisfaction with their relationships. This scale includes seven items rated from 1 (completely dissatisfied) to 7 (very satisfied; e.g., “In general, how satisfied are you with your relationship?”); α = .92. Conflict resolution: voice (α = .74), loyalty (α = .59), exit (α = .91), and neglect (α = .71), in addition to socio-demographic characteristics, are described in Study 1. Table 2 Mean, Standard Deviations Correlations and Differences for the Variables Studied by Gender (Study 2)  Note. N = 185; correlations among variables for man appear on the upper diagonal and for woman on the lower diagonal. Higher scores on continuous variables indicate greater standing on the variable (e.g., greater emotional intelligence). Results from one-way between-groups analysis of covariance to investigate gender differences in our main measures are presented in the Table. These results include participants’ age, relationships length and status as covariates showing a statistically significant difference between men and women on the combined dependent variables; F(7, 175) = 4.21, p < .001; Wilks’ Lambda, ŋ2 = .15. *p < .05, **p < .01. Table 3 Regression Results for Moderated Mediation (Study 2)  Note. N = 185. EI = emotional intelligence; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval. Higher scores on continuous variables indicate greater standing on the variable (e.g., greater EI). Unstandardized regression coefficients are reported. Bootstrap simple size: 5,000. LLCI = lower level of the 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval; ULCI = upper level of the 95% bootstrap percentile confidence interval. The indirect effect is significant where the confidence intervals does not contain zero. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Results Table 2 shows descriptive statistics regarding the main variables used in this study and the correlations between them by gender. The mediator role of conflict-facing responses between emotional intelligence, psychological well-being, and relationship satisfaction, moderated by gender. To test Hypotheses 2 (the conditional indirect effect of EI on psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction through conflict-facing responses moderated by gender), we applied the moderated mediation model following the steps suggested by Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes (2007)—see Figure 1 for graphical representation. To assess moderated mediation, we examined four conditional effects: (a) the significant effect of EI on psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction, (b) the significant effect of EI on the response to conflict, (c) the significant interaction between EI and participant’s gender on conflict-facing responses, and (d) the conditional, indirect effect of EI on psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction via the conflict-facing responses depending on a participant’s gender. Moderated mediation analyses were conducted using SPSS PROCESS macro 2.16 model 7 (Hayes, 2013). Two analyses were conducted. In both of them we introduced EI as independent variable, conflict-facing responses as mediator variables, participants’ gender as moderator variable, and psychological well-being (first model) and relationship satisfaction (second model) as dependent variables. Moreover, because 46.5% of the participants answered measures based on a previous relationship and conflict-facing responses could differ in the initial stage of romantic relationships (Nader, Alireza, Roben, & Shokoh, 2016), we included being or not involved in a current relationship and the relationship’s length as covariates in the models. Furthermore, because previous research had found that EI scores could be affected by participants’ age (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2012) we also controlled for age. We generated 95% bootstrap bias-corrected confidence intervals for the indirect effect conditioned by participants’ genders on the basis of 5,000 bootstrap samples. The conditional, indirect effect is significant where the confidence intervals do not contain zero. To facilitate interpretation and provide estimates of effect size, all continuous variables were standardized. Results are presented in Table 3. Figure 2 Effects of Emotional Intelligence and Participants’ Gender on Voice Response (A), and Neglect Response (B). Higher scores on continuous variables indicate greater standing on the variable (e.g., greater emotional intelligence).  The results showed a direct, significant effect of emotional intelligence on psychological well-being. However, no effect of emotional intelligence was found on the relationship satisfaction (conditional effect A). Moreover, a significant effect of both emotional intelligence (conditional effect B) and the interaction between EI and participant’s gender (conditional effect C) were found for the voice and neglect responses. Therefore, in both women and men, greater EI was associated with a greater voice response (Figure 2A presents a graphical representation of this effect). Furthermore, greater EI was associated in men with a lower neglect response (Figure 2B presents a graphical representation of this effect). Conversely, no significant effects of EI and its interaction with gender were found for loyalty or exit response. Finally, the indirect effect of EI on psychological well-being and satisfaction with the relationship was observed through the constructive voice response and the destructive neglect response (conditional effect D). Voice response mediated the relation between EI and psychological well-being, as well as between EI and satisfaction with the relationship when the participant was a woman or a man (consistent with Hypothesis 2a). Likewise, the neglect response mediated the relation between EI and both consequences but only when the participant was man (consistent with Hypothesis 2d). Conversely, no indirect effect of EI on psychological well-being and satisfaction with the relationship was found through exit (Hypothesis 2b) or loyalty (Hypothesis 2c) response. Close relationship partners inevitably encounter situations in which their preferences diverge, leading to disagreement; likewise, potential consequences can be determined by the type of responses that people use to face such conflicts (Overall & McNulty, 2017). However, the responses adopted to a romantic conflict and the underlying factors that explain the origin of a particular style of romantic conflict responses are still unclear. Given the findings of previous literature, to address this gap we study the responses to romantic conflicts based on the participants’ gender (Study 1), and tested a moderated mediation model in which we analysed whether participants’ EI is related to responses used to face romantic conflicts, and in turn their psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction, and whether this relationship vary to the extent of participants’ gender (Study 2). When focusing on responses that women and men used after a conflict with their partners in four independent samples, after meta-analysing the results, we confirm our Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c, finding that women respond more expressively (voice) and loyally to conflicts, while men may respond more negligently. This fact seems to note the existence of a differential gender pattern in conflict-facing actions. According to the social role theory (Eagly & Wood, 2012), the results showed that even today men and women normally use stereotypes congruent with their gender roles to face conflicts generated in their most intimate contexts, such as romantic relationships. Therefore, it seems that women are still educated in communal values. This promotes, on the one hand, their expression responses during stressful situations but, on the other hand, enhances their awareness and concern for the maintenance of their relationships, leading them to accept the situation and behave loyally during romantic conflicts. Conversely, after finding a greater neglect response in men, we observed how they are socialized in agentic values according to traditional gender stereotypes that promote aggressive responses, independence, and self-confidence during their romantic conflicts (Biernat & Sesko, 2018; Bradbury & Karney, 2010; Ellemers, 2018). Finally, consistent with Hypothesis 1d, the results indicated the absence of gender differences in the use of the exit response, or abandoning the relationship. Therefore, according to the previous literature, exit responses could be primed by other factors with a relational or situational nature such as commitment to the relationship or people’s perception of the seriousness that could arise from the conflict’s consequences (Beltrán-Morillas, Valor-Segura, & Expósito, 2015; Garrido-Macías et al., 2017; Holt & DeVore, 2005). Once we observed the different romantic conflict-facing responses by men and women, perhaps the most noteworthy finding from this study was the confirmation of a moderated mediation model in which EI became a key factor associated to the adoption of adaptive conflict-facing responses by both women and men and, ultimately, to their greater psychological well-being and satisfaction with the relationship. Specifically, in line with previous studies (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2016; Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016; Schutte, Malouff, Thorsteinsson, Bhullar, & Rooke, 2007), this model showed, on the one hand, that EI was positively related to psychological well-being because it promotes greater knowledge and personal control (Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 2000; Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2016). Likewise, on the other hand, EI was found to be positive and indirectly related to the personal level through psychological well-being and to the interpersonal level through satisfaction with the relationship (Hypotheses 2). This situation manifests because the responses adopted in conflict situations and, therefore, the dynamics of couple relationships could be favoured by emotional intelligence (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2016; Fernández-Berrocal & Extremera, 2016; Schutte et al., 2007; Zeidner et al., 2013). Specifically, the moderated mediation model revealed that having a high EI is particularly important for increasing the active constructive response (voice) to face romantic disagreements in women and men, and in turn their psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 2a). This voice facing is the most adaptive response that people may adopt to solve conflicts that arise in intimate contexts (Overall & McNulty, 2017; Rusbult et al., 1986). Secondly, besides the positive association between EI to voice, results showed that a greater EI is also negatively associated to the negligent destructive responses that men traditionally have used to cope with conflict and, in turn, to their psychological well-being and relationship satisfaction (Hypothesis 2d). This could indicate that EI, in addition of being a factor that promotes the development of constructive social interactions, could also become a protective factor for the habitual use of aggressive and coercive responses (previously shown in the mini meta-analysis) directed towards women in certain conflict situations (Jaffe, Simonet, Tett, Swopes, & Davis, 2015; Lopes et al., 2004). An explanation could lie in the fact that EI allows people to perceive and understand both their own emotions and their partners’ emotions during conflict situations. Thus, this moderated mediation model, according to previous studies (Śmieja & Stolarski, 2018; Smith et al., 2008; Zeidner & Kaluda, 2008; Zeidner et al., 2013), corroborate the sequence through which EI is associated to conflict-facing responses and personal or relational outcomes, and sheds light on the gender impact in theses associations. Specifically, by showing the positive association between EI and active constructive conflict resolution in both men and women (Batool & Khalid, 2012; Brackett, et al., 2005; Zeidner & Kloda, 2013; Zeidner et al., 2013) and extending it by showing that as EI scores increase, the passive destructive conflict resolution of men decreases, filling the unclear conclusion left open by previous studies. In contrast, results have not shown the expected relationship between EI, psychological well-being, and satisfaction with the relationship through the constructive loyalty response in women (Hypothesis 2c), and destructive exit response in both, women and men (Hypothesis 2b). Thus, Hypotheses 2 cannot be fully supported. These results are not surprising, given that both loyalty and exit are responses that imply a conflict of interest. For example, despite being a constructive response that encourages the maintenance of the relationship, loyalty implies passivity and inactivity in a threatening situation. Therefore, according to Overall et al. (2010), the loyalty response could have negative consequences for the person, for example by blocking the regulation of internal discomfort and contradicting the ultimate goal of EI, which is to use emotions to favour both social relations and personal well-being (Bear, Weingart, & Todorova, 2014; Marroquín et al., 2017; Overall et al., 2010). Regarding the exit response, despite being a destructive response for the relationship, this response could be associated with (inter)personal benefits by ending a relationship that is conflictive (Overall & McNulty, 2017). Therefore, it is possible that this behaviour may be used by EI people in order to stop a damaging situation, which could explain the absence of congruent results found for these responses. Future studies would benefit from testing these ideas in order to provide more extensive explanations. In addition to being of theoretical importance, our results have practical implications that might be incorporated in an intervention program in couple therapy. Nowadays, couples’ interventions during conflictive dynamics usually work on how communicate and face romantic conflicts (Gottman & Krokoff, 1989), the behaviours they may adopt to their partner (Dimidjian, Martell, & Christensen, 2002), and the emotional regulation process during couples’ conflicts (Johnson, Batey, & Holdsworth, 2009; O’Connor et al., 2018). In the present research, we go a step further noting two important factors to work in couples’ therapy. First, we demonstrate that women and men face conflicts differently. Given one of the main explanations of this result lies in the social role theory (Eagly & Wood, 2012), we suggest that, as one part of their overall approach, couples’ therapist works on gender socialization processes to demystify gender stereotypes that may underlie human behaviour. Secondly, given the protective role that EI could play in conflict resolution as well as in psychological well-being and relationship’s satisfaction, an effective form of treatment for such couples might be working on emotional competences (Martínez, Rodríguez, Álvarez, & Becedóniz, 2016). Specifically, we suggest that an EI training focused on the ability to perceive, regulate, and use the emotions of both partners during an conflict situation enable people how to connect with their partner, discuss their emotional experience, deal with them and, therefore, practice a new form of communication that should improve the couple dynamics (O’Connor et al., 2018). Indeed, prior studies have already shown the effectiveness of ability and trait EI training in young couples’ dynamics due to the enabling role that emotional competences play in conflictive situations that arise in interpersonal relationships (Johnson, Batey, & Holdsworth, 2009; Nader et al., 2016). However, they have not analysed the EI training impact on conflict resolution and their personal or relationship implications regardless of the gender inequality explanations of conflict behaviour. Therefore, future research should aim to analyse how an interactive gender and EI training increases constructive conflict-facing responses and thus, the personal and relationship quality in an adult sample of women and men. The present research provides evidence of conflict-facing gender differences and the adaptive role of EI for them. Yet, there are some limitations that also offer other valuable opportunities for future research. First, the sample of our second study was withdrawn from the young general population, which hinders generalization of the results to other populations. Future studies using a larger sample composed by a representative participants’ selection of each cohort from the general population should corroborate our finding in more detail. Second, in the present research, we have controlled participants’ age, relationships status, and length differences by including them as covariates; nonetheless, further research controlling other personal and situation variables would be necessary. For example, regarding participants’ characteristics, their educational level is a variable that needs to be considered given that the educational level could correlate positively with EI (Goldenberg, Matheson, & Mantler, 2006) and adaptive marital conflict management (Gherghinescu & Glăveanu, 2015). With regard to situational characteristics taken into account, variables such as the frequency and the severity of the conflicts may be necessary because they could influence the type of responses that people will adopt (Garrido-Macías et al., 2017). Third, although the use of self-report measures has a strong external validity, they are based on subjective perceptions of the participants. Future studies should benefit from employing behavioural measures of our interested variables, and especially from comparing the different effect of EI on conflict-facing responses and personal or relationship outcomes for men and women depending on the EI’s theoretical approach (performance-based ability, self-report ability, and self-report mixed models) and type of instrument used. Finally, the correlational and cross-sectional nature of our study prevents us from establishing any causal relationships between variables. Therefore, future lines of investigation should employ longitudinal as well as experimental designs in order to overcome these limitations and test the practical implications of our model. Romantic relationships can be one of the main causes of suffering when they are violent or cause conflict. Analysing the mechanisms involved in conflict-facing responses could have both theoretical and practical implications. This research highlights the need to continue with gender equality education, as well as the use of adaptive strategies that improve EI in romantic conflicts. These suggestions can positively impact personal well-being and relationship satisfaction. In conclusion, the present research makes a specific contribution to the importance of emotional skills in couples’ relationship therapy from the gender perspective. However, continuing to research in this line is necessary to provide a complete understanding of the contribution of EI to intimate contexts and to apply such a knowledge to effective personal and social interventions. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Alonso-Ferres, M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Couple conflict-facing responses from a gender perspective: Emotional intelligence as a differential pattern. Psychosocial Intervention, 28, 147-156. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a9 Funding: This paper was made possible thanks to the financing provided by the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports through a university teaching training grant (FPU16/03023), and by the projects “Macrosocial realities (economic crisis and social class) and psychosocial processes: Trust, welfare, altruism, and politics” (Ref. PSI-2017-83966-R) (MINECO/AEI/FEDER/UE) and “New ways of gender violence: Risk and protector factors for psychosocial well-being” (Ref. PSI2017-84703-R) (MINECO/AEI/FEDER/UE). |

Cite this article as: Alonso-Ferres, M., Valor-Segura, I., & Expósito, F. (2019). Couple Conflict-facing Responses from a Gender Perspective: Emotional Intelligence as a Differential Pattern. Psychosocial Intervention, 28(3), 147 - 156. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a9

maalfe@ugr.es Correspondence: maalfe@ugr.es (M. Alonso-Ferres).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS