Understanding of Factors Associated with Reporting to the Police, Helping Seeking, and Adopting in Self-protection among Stalking Victims: A Latent Class Analysis

[Conocer los factores asociados a las denuncias a la policĂa, la bĂşsqueda de ayuda y la adopciĂłn de autoprotecciĂłn en las vĂctimas de acoso: un análisis de clases latentes]

Sujung Cho1, Chunrye Kim2, and Jennifer Gatewood Owens3

1Southern Illinois University Carbondale, USA; 2Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia, USA; 3University of Missouri–Kansas City, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2023a5

Received 1 November 2021, Accepted 8 February 2022

Abstract

Victims of stalking use multiple help-seeking behaviors including reporting their experiences to the police, obtaining a restraining order, blocking communication, and relying on informal social networks like friends, family, or therapists. The goal of this study is to, first, identify distinct subgroups of stalking victims based on their help-seeking behaviors. Next, we identify the direct effect of sex, victim-offender relationship, and offense severity on class membership. Finally, we include negative emotions as a mediating effect. Using the 2016 National Crime Victimization Survey’s Supplemental Victimization Survey data, latent class analysis was utilized to identify class membership among 1,459 stalking victims. The results indicate three groups: passive help-seekers, informal help-seekers, and active help-seekers. We found that females are more likely to be assigned to the active or informal group and these two groups appear to experience more severe stalking behaviors compared to the passive group. Specifically, victims were less likely to ask for help actively and ask family, friends, and non-professional people for help for whom stalking took place by other/unable to identify individuals. Victims whose stalkers had a criminal record, whose stalkers threatened themselves or others, as well as who suffered stalking lasting for months and the most often were more likely to ask for help actively and ask family, friends, and non-professional people for help. The significance of victims’ perceptions of severity of both groups is only partially mediated by negative emotions.

Resumen

Las víctimas del acoso utilizan diversos comportamientos de búsqueda de ayuda, como denunciar los hechos a la policía, conseguir una orden de alejamiento, bloquear la comunicación o confiar en las redes sociales informales como amigos, familia o terapeutas. El objetivo del estudio es en primer lugar reconocer distintos subgrupos de víctimas de acoso en función de sus comportamientos de búsqueda de ayuda. A continuación observamos el efecto directo en la pertenencia al grupo del sexo, la relación víctima-agresor y la gravedad del delito. Por último, abordamos el efecto mediador de las emociones negativas. Utilizando los datos de la encuesta suplementaria de victimización de la Encuesta Nacional de Delitos de Victimización de 2016 nos servimos del análisis de clases latentes para analizar la afiliación de clase en 1,459 víctimas de acoso. Los resultados muestran tres grupos: buscadores de ayuda pasivos, informales y activos. Resultó que es más probable que las mujeres sean asignadas al grupo activo o informal y que estos dos grupos parecen experimentar comportamientos de acoso más graves en comparación con el grupo pasivo. En concreto era menos probable que las víctimas pidieran ayuda activamente y a la familia, amigos y personas no profesionales que habían sufrido acoso por parte de otras personas incapaces de identificar. Era más probable que las víctimas cuyos acosadores tenían antecedentes penales y les habían acosado a ellos o a otras personas y cuyo acoso había durado meses y más a menudo pidieran ayuda activa y también a la familia, amigos y personas no profesionales. La importancia de cómo percibían la gravedad ambos grupos solo estaba mediatizada en parte por las emociones negativas.

Keywords

Stalking, Help-seeking, Latent class analysis, Negative emotions, Victim-offender relationshipPalabras clave

Acoso, BĂşsqueda de ayuda, Análisis de clases latentes, Emociones negativas, RelaciĂłn vĂctima-agresorCite this article as: Cho, S., Kim, C., & Owens, J. G. (2023). Understanding of Factors Associated with Reporting to the Police, Helping Seeking, and Adopting in Self-protection among Stalking Victims: A Latent Class Analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 32(3), 141 - 154. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2023a5

Correspondence: sujung.cho@siu.edu (S. Cho).

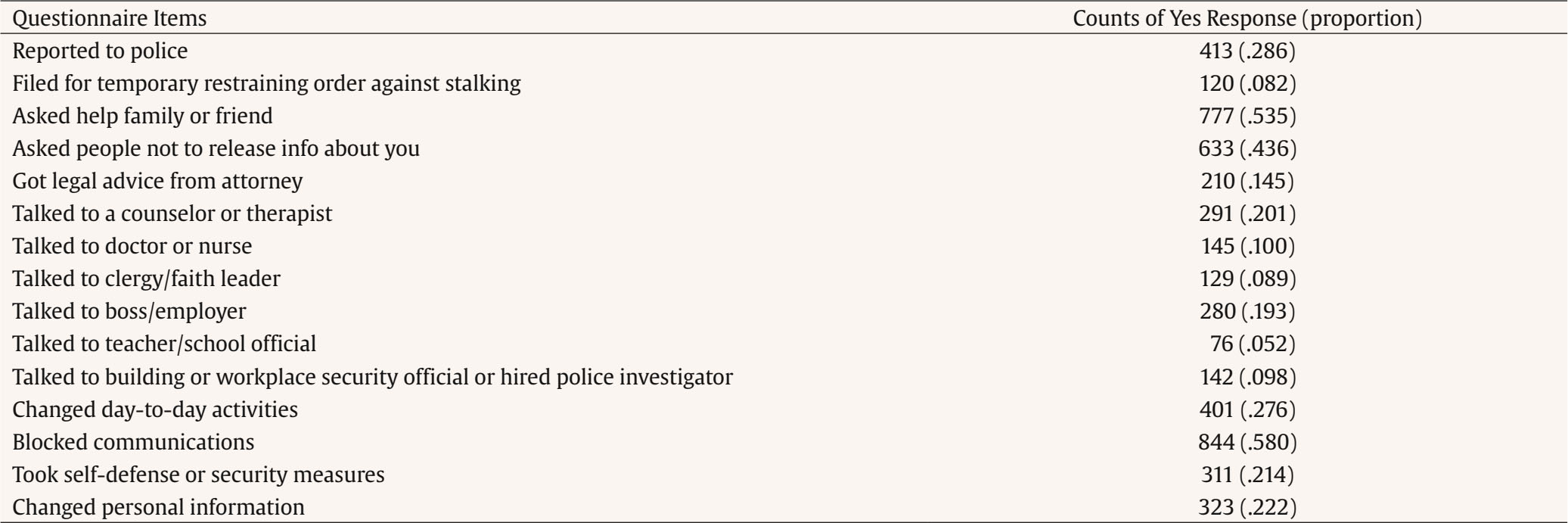

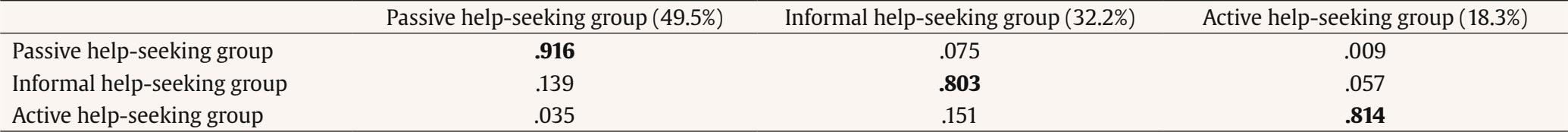

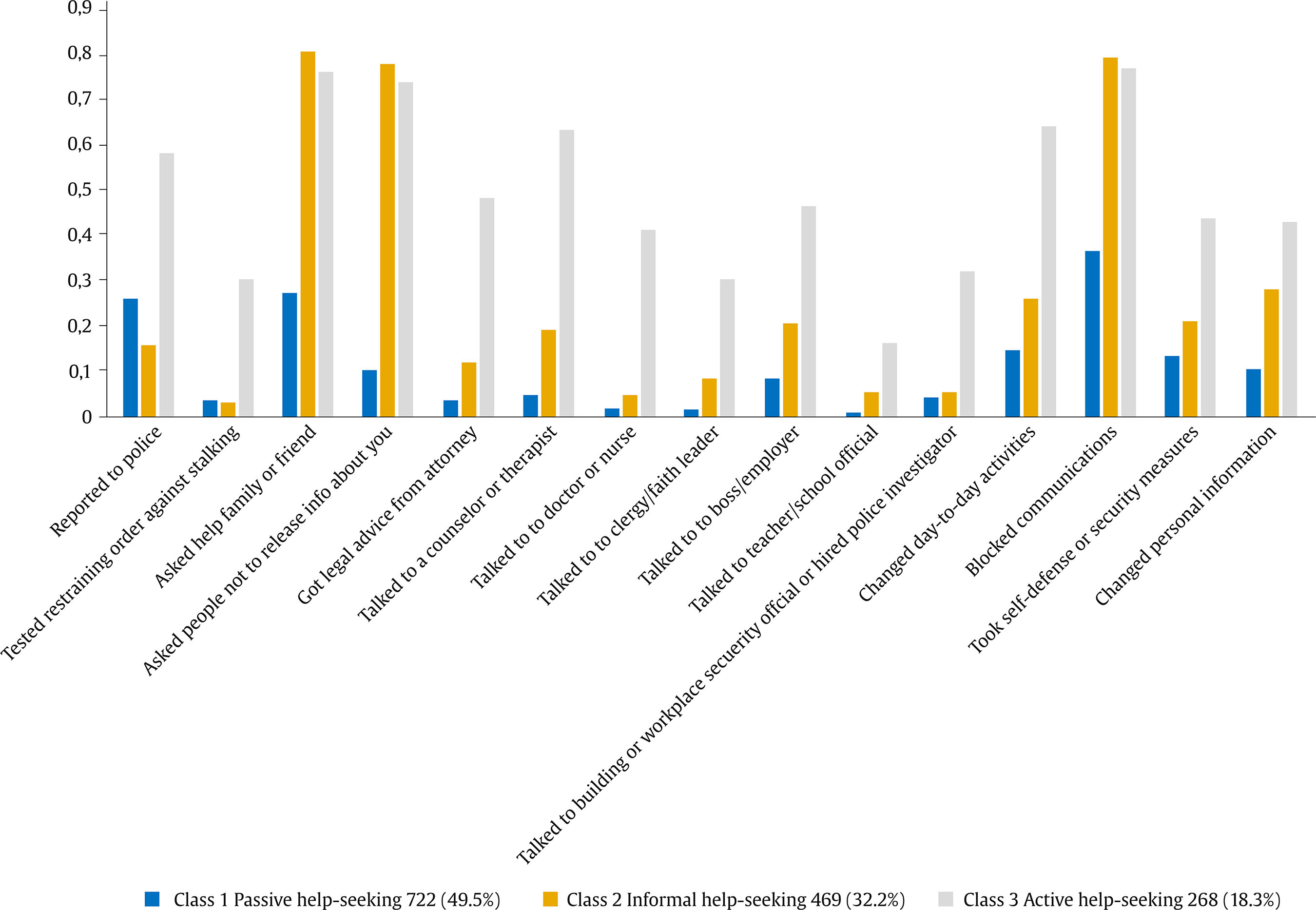

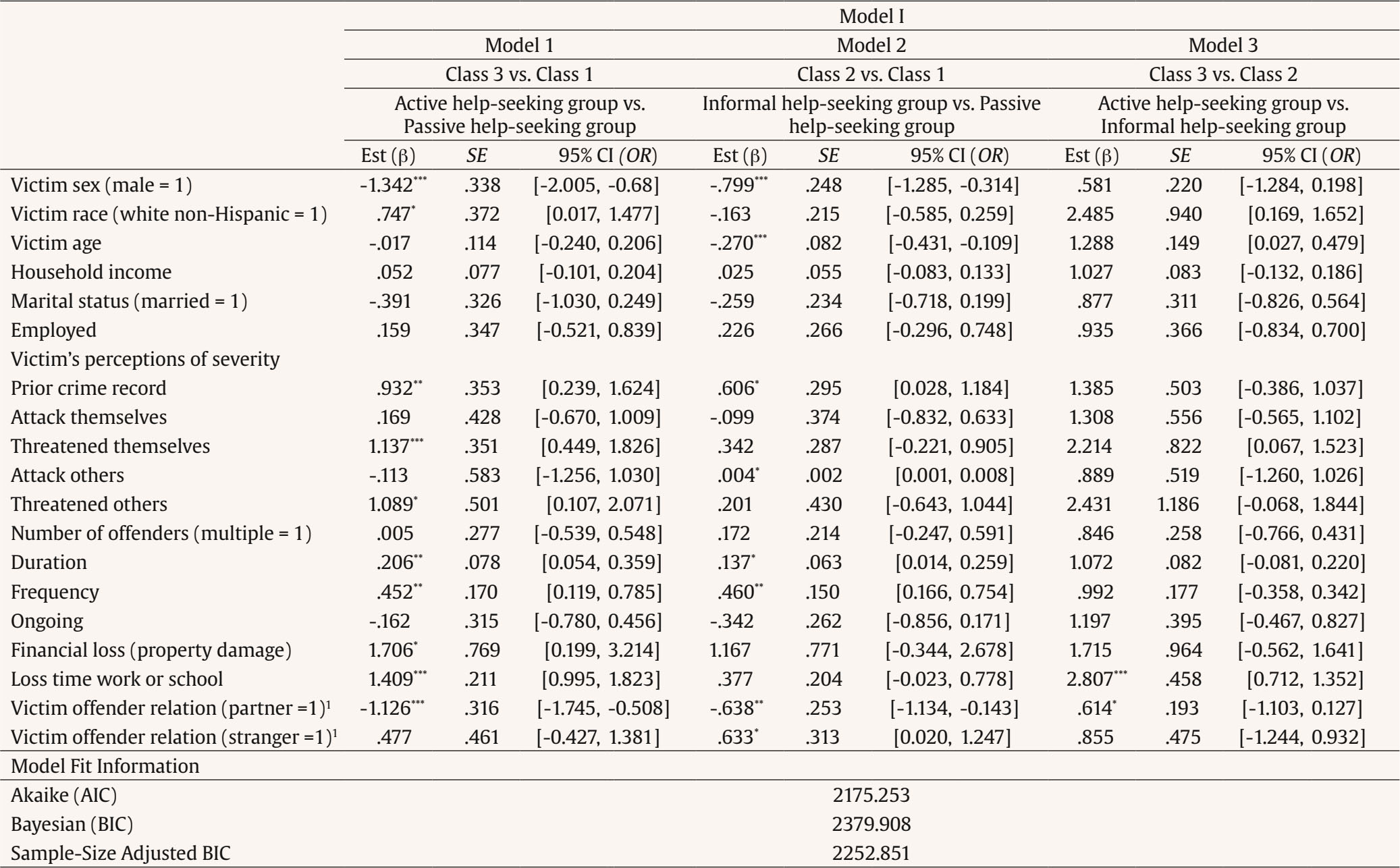

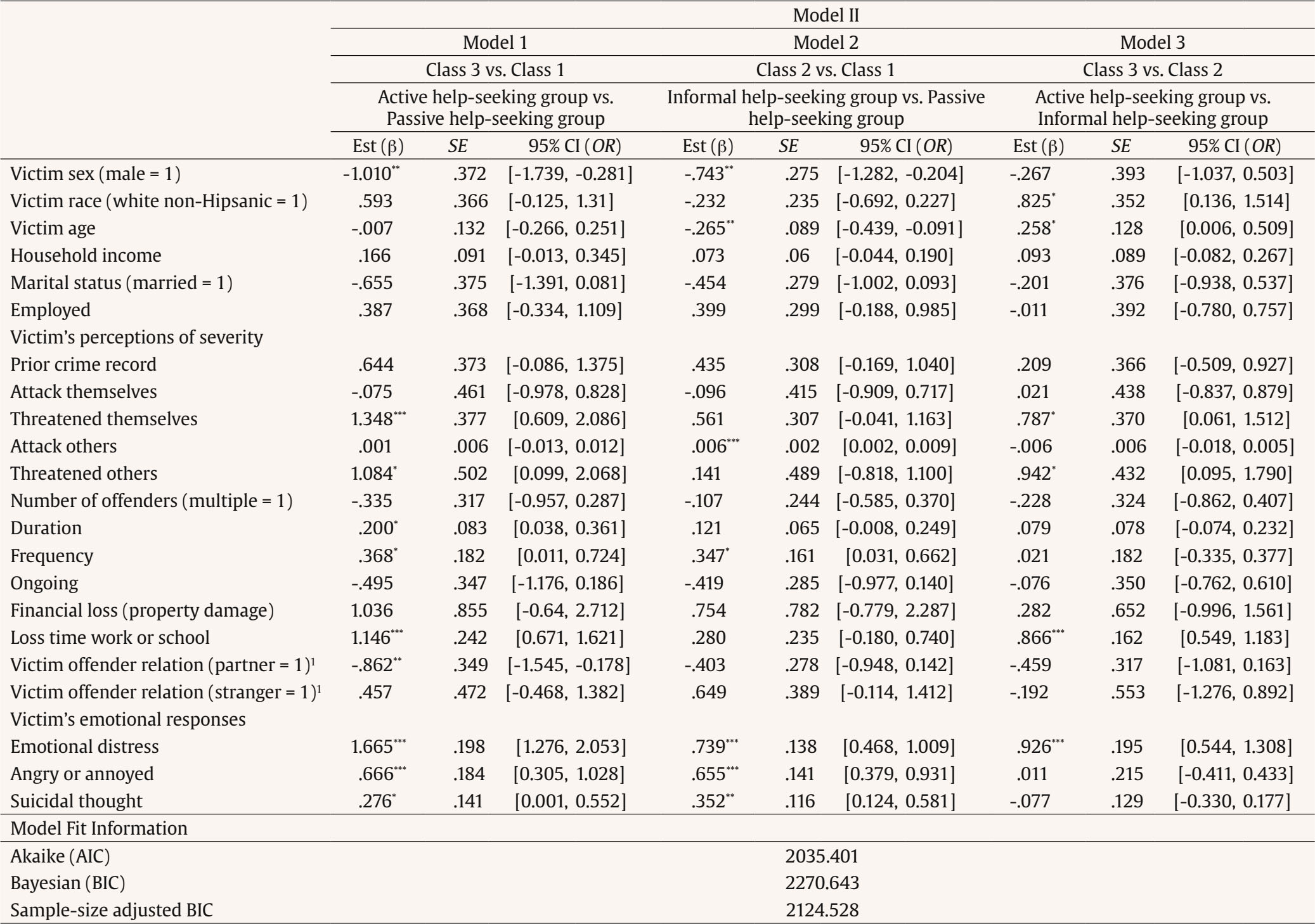

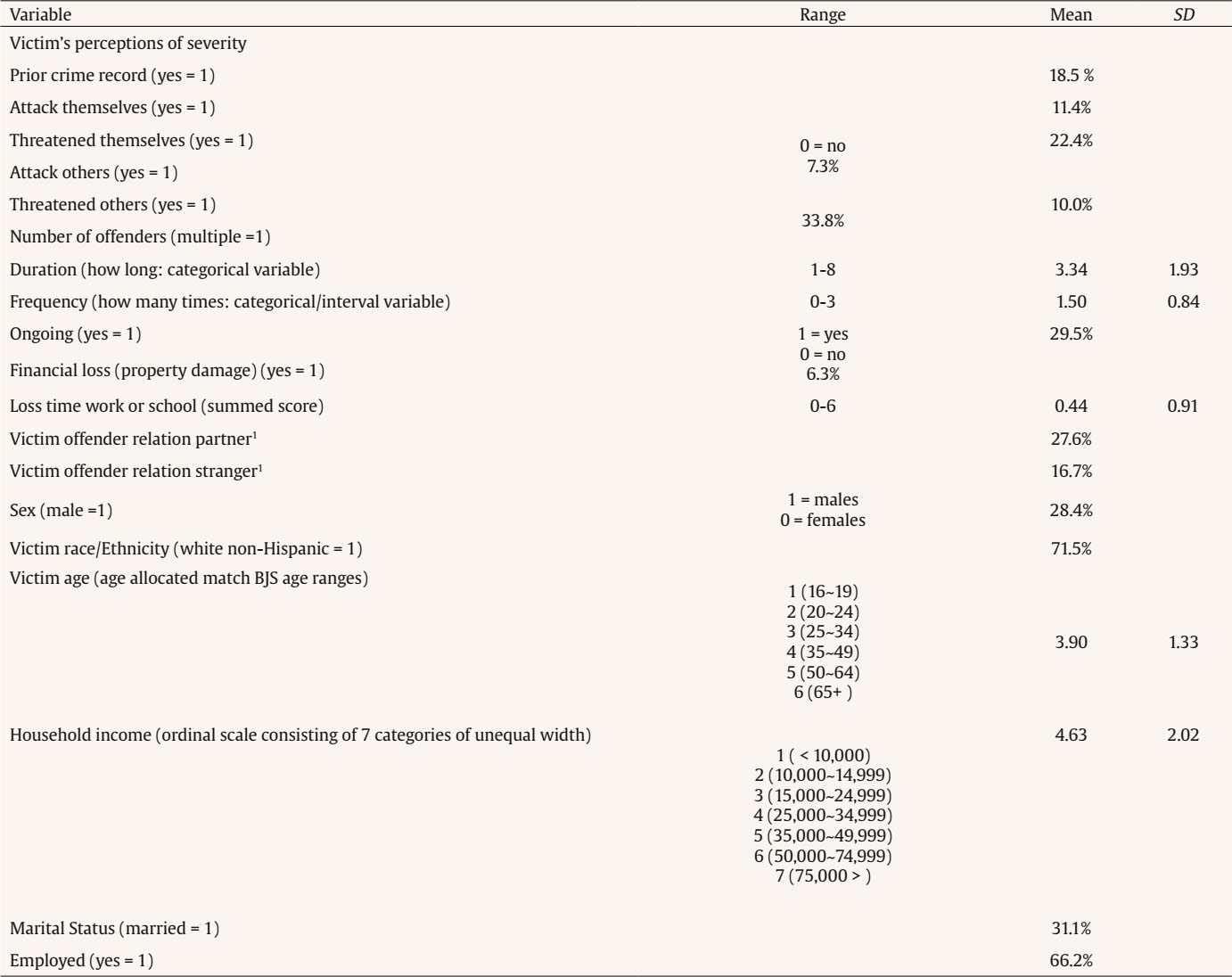

Stalking is widely recognized as a serious public health and societal concern. Although the definitions of stalking behavior vary by state and in the literature, they are generally repeated, unwanted in-person and/or electronic behaviors that cause the victim to suffer. The Bureau of Justice Statistics defines stalking as “repeated unwanted contacts or behaviors that either cause the victim to experience fear or substantial emotional distress or that would cause a reasonable person to experience fear or substantial emotional distress” (Truman & Morgan, 2021, p. 1). There are many economic consequences associated with stalking victimization including social, psychological, and physical (Blaauw et al., 2002; Dressing et al., 2006). Victims report altering their behaviors to avoid their perpetrator(s), including moving or leaving their jobs, obtaining protection orders, and seeking psychological treatments due to stalking (Purcell et al., 2005; Tjaden, 1997). Those who are stalked for a longer period deal with higher rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic symptoms (Purcell et al., 2005). A significant body of empirical research has shown that certain factors such as victims’ perceptions of severity and emotional responses increase the likelihood that victims report to the police (Reyns & Englebrecht, 2010), seek help (Buhi et al., 2009; Reyns & Englebrecht, 2013), and take self-protective measures (Goldsworthy & Raj, 2014; Nobles et al., 2014; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2003). Identifying how these different reactions to stalking situations manifest in different combinations is critical because the possible mechanism for the reactions likely differs. Little research has attempted to identify distinct patterns (classes or subgroups) of victim decision-making. Even less has considered variation in victims’ perceptions of severity and emotional responses in combination with typologies of victim decision-making. Similarly, among women who sought temporary protective orders related to their IPV victimization, Parker et al. (2015) examined their perceived dangerousness such as being seriously injured or even killed by the perpetrators on victims’ safety strategies. They found that when victims perceived that their risk is serious, they tend to utilize safety planning, including keeping money and other valuables hidden, working out an escape plan, removing, or hiding weapons, etc. Given the lack of research on typologies of stalking victim decision-making, the current study sought to address this gap in the literature. Using latent class analysis (LCA), this study attempted to first identify latent subgroups of stalking victims, each having a unique pattern of decision-making. Once identified, it examined the impact of relevant correlates of victims’ perceptions of severity and emotional responses on the probability of class membership. Review of Literature There were an estimated 3.8 million persons stalked in the United States in 2016 or 1.5% of the population aged 16 and older (Truman & Morgan, 2021). Stalking victimization is not always veiled threats but also results in violence and property damage (Hall, 1998; Meloy, 1996; Mullen et al., 2000; Pathé & Mullen, 1997; Slashinski et al., 2003; Tjaden & Thonenes, 1998). Mohandie et al. (2006) used a nonrandom sample of 1,005 North American stalkers, not victims, and found 46% were violent towards and 26% damaged or stole property from their victims and this was most common when they had an intimate relationship with the victim. Using the prior SVS in 2006, Baum et al. (2009) found 21% of stalking victims reported the offender attacked them, 15% reported the stalker attacked another person or pet, and over 24% reported property damage. Similarly, Tjaden and Thoennes (1998) found 45% of females and 43% of males were overtly threatened and 29% of females and 30% of males stalking victims reported property damage. Help Seeking – Police and Beyond Victims respond to crime in numerous ways but one frequency discussed is reporting the crime to the police. Several factors have been found to be important in understanding what increases a victim will report a crime to police, including 1) crime severity with more severe types of crime, injury, and monetary loss is more likely to be reported; 2) victims’ sex with females is more likely to report than males; 3) victims’ age where older victims are more likely to report than younger ones; and 4) victim-offender relationship where offenders and victims’ relationship is close such as intimate partner has some of the lowest reporting levels (Langton et al., 2012; Ménard & Cox, 2016; Skogan, 1984). Research documents several factors that are related to why victims, in general, will not come to the attention of police through reporting. The NCVS gathers this data each year. In a report using NCVS data from 2006-2010, 58% of all violent and property crimes were not reported. The most common reasons for not reporting a crime to the police were the police would not/could not help (31%), it was not important enough to report (27%), and the victim dealt with it in another way (20%) (Langton et al., 2012). Researchers have also studied police reporting following stalking victimization. Baum et al. (2009) found only 37% of males and 41% of females reported their stalking victimization to the police. The most common reasons for not reporting were it was a “minor incident” (27%), “private/personal matter” (27%), or it was “reported to another official” (14%). In an earlier study, Tjaden and Thoennes (1998) found nearly 48% of male and 55% of female victims reported their stalking cases to the police. It is important to note that third parties can also report stalking to the police. Of those who reported, 75% of male victims said they self-reported while 84% of female victims of stalking said they reported it to the police, so the remainder were from third parties. The most common reason to not report to the police was it was “not a police matter” (20%), “police couldn’t do anything” (17%), and fear of “reprisal from stalker” (16%) (Tjaden & Thoennes, 1998). Beyond reporting to the police, stalking victims have many ways to seek help through other mechanisms. Spitzberg and Cupach’s (2003) review of the literature identified five categories of coping or management tactics: moving inward (e.g., ignoring the issue, self-destructive escapes like drugs), moving outward (e.g., seeking social support friends, legal system input), moving away (e.g., create distance from the stalker), moving toward/with (bargain with the stalker), and moving against (use aggression or build a legal case against the stalker). Victims can use one or all of these strategies throughout the course of the stalking incident as stalking behaviors can last for years (Catalano, 2012). Recently, Diaz (2021) found when multiple stalkers worked together, compared to single offenders or multiple, independent stalkers, the victim experienced an increase in the number of negative outcomes. There is also evidence to suggest that men might take a greater variety of strategies and in-particular ones that directly confront stalking compared to women who tend to reduce social contact (Acquadro et al., 2020). Classifying Subtypes of Stalking Victims’ Decision-Making Victims of stalking tend to use multiple help-seeking behaviors, including reporting their experiences to the police, obtaining a restraining order, blocking communication, and relying on informal social networks like friends, family, or therapists (Kaukinen, 2004; Podana & Imriskova, 2016). However, not all victims adopt the same strategies to deal with their victimization. Some victims seek informal help only, whereas some other victims seek formal help or professional help. At the same time, some victims take multiple measures to deal with their victimization. Different patterns emerge among victims in their decision-making as they are dealing with their victimization. Using the data from the Violence and Threats of Violence against Women and Men in the United States Survey, 1994-1996 (NVAWS), Kaukinen (2004) examined help-seeking strategies among violent crime victims of stalking, sexual assaults, physical assaults, and violent threats. They found three different help-seeking strategy patterns—minimal or no help-seeking, family and friend help-seeking, and substantial help-seeking among violent crime victims. Thirty-nine percent of victims were “minimal or no help-seeking,” meaning they rarely seek help from others. Forty-one percent of them belonged to a “family and friend help-seeking” group and 20% of them were a “substantial help-seeking” group who would seek help from various groups of people, including family, friends, the police, and professional care and service agencies. Similarly, among citizens of the Czech Republic, Podana and Imriskova (2016) identified three different behavioral coping strategies victims used in dealing with their stalking victimization. The first group is the “proactive behaviors” group, who used proactive strategies to solve their situation, including contacting the police, seeking professional or informal help, and changing their address. The second group is the “avoidance” group (30%), who tried to avoid physical contact with offenders by changing their daily routine, their route used to travel to work, and so on. Finally, the last group is the “passive behaviors” group (23%), who responded to stalking using passive means, such as just ignoring the offender. Similarly, among college students who experienced repeated and unwanted pursuit for the purpose of intimate relationships, an act called “obsessive relational intrusion,” Cupach and Spitzberg (2000) identified 4 different coping responses: 1) interaction (e.g., yelled, talked seriously to that person), 2) protection (e.g., called the police, sought a legal remedy), 3) retaliation (e.g., shamed the person), and 4) evasion (e.g., ignored that person). Although they did not include stalking victims directly, Cheng et al. (2022) also examined patterns in stalking strategies employed among 369 adult female intimate partner violence (IPV) survivors recruited from IPV service agencies. They found three different subgroups—a group that broadly engages formal and informal networks (50%), one that primarily engages informal networks (15%), and one that broadly engages networks but avoids the legal system (35%). Interestingly, women who “broadly [engage] formal and informal networks” and women who “broadly [engage] networks but [avoid the] legal system” tend to show similar probabilities of utilizing social services, but the latter group of women has a lower probability of contacting the criminal justice system. As a large number of stalking victims have experienced IPV while they were in relationships or after break-ups (Kim & Cho, 2022), we can safely conclude that the existence of different help-seeking strategy patterns among IPV victims might be similar among stalking victims. Assessing Impacts of Victims’ Perceptions of Severity There is evidence that victims of crime tend not to seek help until their victimization is severe, and one of the main reasons they do not seek help, especially from formal agencies, is that they do not think their victimization is severe enough (Ameral et al., 2020; Fernandez-Cruz, 2021; Kim & Ferraresso, 2022; Park & Ko, 2020). A victim’s perception of the severity of their violent experience plays an important role in their decision-making process. Although the perception of severity can be measured differently, according to various studies, there is evidence that a strong relationship exists between victims’ severity perception and their help-seeking behaviors and strategies. For instance, Nobles et al. (2014) compared the stalking and cyberstalking victims’ self-protective behaviors using data from the 2006 Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS) to the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). Using offenders’ threatening behaviors, the duration of stalking, fear of victimization, and other variables that are associated with the perception of violence severity, they examined the impact of those variables on their protective behaviors. They found that both stalking and cyberstalking victims tend to install caller ID or call-blocking systems at a higher rate and change their usual activities outside of work or school. Though cyberstalling victims tend to change email addresses at a higher rate (17.57%), this behavior’s frequency was not high among stalking victims (2.91%). In addition, costs of victimization were statistically associated with the number of self-protective behaviors among both stalking and cyberstalking victims, but having experienced an offender’s threat was only statistically associated with stalking victims’ behaviors while having experienced an offender’s attack was associated with cyberstalking victims. This result indicates that victims’ perception of severity is associated with their protective behaviors, but there are some differences between stalking victims and cyberstalking victims. Among the sample of 76 Portuguese male stalking victims, Gonçalves et al. (2021) examined help-seeking behaviors. They found that only 25% of victims sought help, and those people who sought help were seeking it from their family members and friends. It was not too common for them to seek professional or formal help, similar to other studies’ findings (Kim & Ferraresso, 2022). Experiencing diverse types of stalking behaviors, fear of stalking and the total impact of victimization were associated with their help-seeking behaviors. Help-seeking behaviors, regardless of whether help is sought from formal or informal sources, are dependent upon the severity of violence experienced among male stalking victims as well. Similarly, Tenkoran et al. (2018) examined the impact of the seriousness of violence, which measured the perceived risk of injuries, on help-seeking behaviors among female IPV victims in Ghana. They found that most women did not seek help (62.2%) and, even if they did, they sought help from their families, neighbors and/or friends, rather than from the police. When they perceived their risk of violence to be moderate or high, they were more likely to seek formal and informal help. In addition, their perceived risk of violence increases their future help-seeking decisions. Negative Emotions Stalking victims experience various negative emotions, including fear, anger, anxiety, and even suicidality due to their stalking victimization, although not all stalking victims experience negative emotions (Ngo & Paternoster, 2016). According to a study among American and Spanish college students (Cruz & Ngo, 2022), 36% of Spanish students and 48% of American students had experienced stalking, and 61.9% of them experienced anger, followed by anxiety (61.6%), fear (35.1%), and helplessness (28.8%) due to their stalking victimization. Nearly 4% of students reported that they felt suicidal. They also found that depending on what types of stalking victims experienced, their emotional reactions were different as well. For instance, victims who experienced surveillance stalking were more likely to be anxious, fearful, helpless, and sick. Also, victims who had experienced approach stalking were more likely to be angry and depressed (Cruz & Ngo, 2022). There is evidence to support that stalking victims’ emotional responses have an impact on their decisions to deal with their victimization, including seeking formal or informal help. Reyns & Englebrecht (2014) examined the factors associated with stalking victims’ decisions to seek help by analyzing the Supplemental Victimization Survey. They found that when victims felt fearful, they were more likely to seek informal help regardless of their sex and their reporting to the police status. In addition, victims who had fearful emotional responses were also more likely to seek formal help by reporting the incident to law enforcement. Being fearful increases both formal and informal help-seeking. Similarly, using the same data, Ngo and Paternoster (2016) examined whether negative emotions triggered by stalking victimization were associated with their coping strategies. They found that when victims felt depressed due to their stalking victimization, they were more likely to adopt different types of strategies, including changing daily activities, taking protective measures, and moving. When victims felt sick or helpless, they were more likely to seek help from others and moving. However, when victims reported being annoyed/angry, they were less likely to change their daily activities. In addition, the co-occurrence of negative emotions had effects on their different coping strategies as well (Ngo & Paternoster, 2013). For female victims, when they were angry and anxious, they were more likely to seek help from others including friends and family, whereas when they were depressed and fearful, they were more likely to change their daily activities. For males, when they were angry and physically sick, they were more likely to change their daily activities. These results indicate that victims experience various negative emotions and the (co)occurrence of different emotions is an important factor for understanding their decision-making and coping strategies to their victimization. The Present Study There is the consideration that some stalking victims may decide to report to the police, while others may take self-protective measures and/or seek help (Nobles et al., 2014; Owens, 2016). Despite emerging evidence regarding stalking victim decision-making, little is known about latent subgroups or typologies of stalking victims based on how they react to a stalking situation. Identifying potential typologies of reactions to stalking behavior is critical because victims react to stalking behaviors differently, conditional upon a victim’s perceptions of severity and emotional responses. The goal of the present study was to identify distinct subgroups in which stalking victims react to a stalking situation by using latent class analysis (LCA) as a “person-centered” approach, which allows us to determine whether subgroups exist based on stalking victim decision-making to address methodological limitations in empirical research that use a “variable-centered” approach that oversimplifies the relations “among individuals”. Stalking victim decision-making was measured with 15 items identified in prior literature, establishing several reactions to a stalking situation (Brewster, 2001). This study extends prior stalking victimization research in three ways by: (1) identifying subtypes of victim decision-making and (2) examining the impact of victims’ perceptions of severity and emotional responses on subgroups/classes membership among persons aged 16 or older about their experiences with stalking during the preceding 12 months in the U.S. This study addresses several gaps in the literature through four research hypotheses: Hypothesis 1: There would be distinct groups of stalking victims based on stalking victims’ decisions to report to the police, seek help, take protective measures, and change daily actions. Hypothesis 2: Victims’ perceptions of the severity of a stalking situation will have greater odds of being a member of a certain subtype of stalking victims’ decisions to report to the police, seek help, take protective measures, and change daily actions. Hypothesis 3: Victims’ emotional responses will have greater odds of being a member of a certain subtype of stalking victims’ decisions to report to the police, seek help, take protective measures, and change daily actions. Hypothesis 4: The significant relationship between victims’ perceptions of the severity of a stalking situation will be reduced by the victim’s emotional responses, conditional on a subtype of the stalking victims’ decision-making. Data Sample To address these research questions, this project draws the National Crime Victimization Survey’s Supplemental Victimization Survey (SVS) (United States Department of Justice). Between July and December of 2016, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS)collected its second supplement to the NCVS that measured stalking victimization (BJS, 2016), the SVS. After completing the NCVS interview, respondents 16 and over were asked to complete the SVS about stalking behaviors that had occurred in the past 12 months. Of the 126,000 eligible NCVS respondents, approximately 96,300 were asked the SVS screener questions, a response rate of 76.1% (Truman & Morgan, 2021). The first step was to replicate the BJS Stalking Victimization, 2016 (Truman & Morgan, 2021) report to align with their coding decisions.1 The first key variable was to determine stalking victimization. “Stalking victimization” was any victim who met all three criteria, they experienced traditional or cyberstalking behaviors in the past 12 months, they experienced it repeatedly, and they expressed fear, emotional distress, or reasonable fear from these behaviors (see Appendix A for specific questions).2 After the removal of non-victims, a total of 1,470 unweighted stalking victims in the past 12 months remained, of which 1,459 were used in the final analysis3. The SCS sample weights were used to avoid sampling bias, leading to the maximization of generalizability. We applied sampling weights for a latent variable structural equation model estimated with a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) estimation by using the WEIGHT option of the VARIABLE command. Measures Dependent Variable “Help-seeking” was created from 15 unique dichotomous responses to questions related to the various ways a victim may ask for help, including reporting to police, talking to friends or others, getting legal advice or a restraining order, changing day-to-day activities, or blocking communication. All variables for the analysis, including the exact phrasing from the 2016 SVS, are described in Appendix A. Independent Variables Prior studies have found that more severe victimizations are more likely to be reported to the police or find other help-seeking behaviors (Reyns & Englebrecht, 2010; Spitzberg & Cupach, 2003). To better understand these impacts, several variables were added to better understand a victim’s perception of severity. “Prior crime record” assesses if the victim believes the offender(s) had already committed a crime. “Attack themselves” is for victims who had been physically attacked or experienced an attempted attack by the stalker(s) while “attack others” refers to attacks or threats to someone close or a pet. “Threatened themselves” refers to victims who were threatened with an attack from the stalker(s) and “threaten others” notes the stalker(s) threatened to attack someone else or a pet. Victims could also note if they were stalked by a single offender, multiple offenders, or an unknown number of offenders. The “number of offenders” is used to capture this with multiple as the reference group. “Duration” is a categorial variable ranging from less than one month, one to less than six months, six months to a year, 1 to less than 2 years, 2 to less than 3 years, 3 to less than 5 years, five or more years. “Frequency” is also categorial including don’t know/remember, two to ten times, 11-50 times, and too many to count.4 “Ongoing” is a dichotomous response to whether the unwanted contacts or behaviors still going on. “Financial loss (property damage)” is a dichotomous measure of whether the stalker(s) damaged or attempted to damage or destroy property belonging to the victim or someone else in their household. “Loss time work or school” is a summed score of seven variables, loss time work or school due to 1) fear or concern safety, 2) police-related activities, 3) court-related activities, 4) changing phone/personal info, 5) moving, 6) fixing damaged property, and 7) other. To assess the impact of “victim-offender relationship” on help-seeking, three categories were created: intimate partners (current or former), strangers, and all others (relative, friend, acquaintance, etc.)/unable to identify (reference group). In our last analysis, we included a measure of the victim’s emotional response. Using exploratory factor analysis of ten emotional responses to stalking, we found three factors. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis with eight items in order to derive one factor we call “emotional distress” including feeling fearful or terrified, worried or anxious, sad or depressed, vulnerable or helpless, couldn’t trust people, sick, stressed or unsafe (Cronbach’s alpha reliability score for the items = .823). “Suicidal thoughts” loaded as its own factor (a single-item measure) as well as “angry or annoyed”. Control Variables The control variables include six variables: victims’ sex (reference = male), victims’ race/ethnicity (reference = White Non-Hispanic compared to all other groups), victims’ age range (interval), annual household income (interval), victims’ marital status (reference = married compared to non-married groups), and victims’ employment status (reference = employed). Analytic Strategy Using Mplus version 7.4, we conducted a latent class analysis (LCA) as a “person-centered” approach (versus a “variable-centered” approach)5 to identify a meaningful number of classes of stalking victims with similar response patterns to binary indicators addressing help-seeking behaviors (Muthén & Muthén, 2015). The analysis of this study utilized a manual 3-step approach. First, models with ascending numbers of classes were compared across one through five-lass models, using multiple relative model fit indices, such as AIC, BIC, SABIC, CAIC, and AWE, with lower values indicating better fitting models (see the bottom of Table 2). Additionally, for likelihood ratio tests (LRT) statistics, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT) was used to compare two adjacent/nested models in assessing whether adding an additional class significantly improves model fit. We tested whether a k-class model (H0) provided a better fit than a k+1 class model (H1), with nonsignificant p-values indicating that an additional class does not provide a better fit (i.e., failing to reject H0) (Nylund et al., 2007). Further, we reviewed the average posterior probabilities (AvePP) of the analysis, which define an individual’s likelihood of assigning to a given latent class and specify how well the indicators predict class membership. The values of diagnostic measures > the .70 threshold suggest that the class assignment accuracy is adequate and well-separated. Lastly, entropy with values approaching one indicates a clearer class separation. After determining the optimal solution model, we used Vermunt’s (2010) three-step approach using the R3STEP6 to address measurement error variances (i.e., misclassification rates/uncertainty rates), which are not well accounted for by other approaches, such as the old classify-analyze approach. A real problem with the old classify-analyze approach ignored uncertainty/imprecision in classification that might lead to biased estimates and biased standard errors for the relationship of class membership with covariates subsequently added to models. With the class modification step, the classification and interpretation of latent class membership were not affected by the subsequent addition of covariates. After this step, the multinomial logistic regression model with the dependent variable with unordered categories was conducted to examine the relationship between class membership and covariates. The logit coefficients of class membership in each category were estimated and contrasted with a chosen reference group. Sample Descriptive Statistics The proportions of stalking victims responding “yes” to binary indicators of help-seeking behaviors are depicted in Table 1. Approximately 58% of the sample reported blocking communications, followed by asking for help from family or friends (53.5%) and asking people not to release information about themselves (43.6%). About 28.6% reported to the police, and 27.6% changed their day-to-day activities. Almost 21.4% took self-defense or security measures, and 22.2% changed their personal information. Table 1 Proportions of Stalking Victims Responding “Yes” for Binary Latent Class Indicators about Help-seeking (N = 1,459)   Latent Class Enumeration Table 2 presents the model fit indices varying numbers of classes estimated during the class enumeration process. Moving from the one to the five-class model, AIC, BIC, and SABIC decreased. However, the minimum CAIC and AWE occurred for the three-class model, and adjust LMR-LRT of the 3-class model (H0) provided a non-significant p-value (p = .21), indicating that we failed to reject the 3-class model. These fit indices have proven to be a consistent indicator of classes, confirming that the three-class model was selected as the final optimal solution. The AvePP for all is greater than .70, indicating that the three classes were well separated and highly accurate in the latent class assignments (see Table 3). Table 2 Model Fit Indexes for Class Enumeration of Help-seeking Items among Stalking Victims   Note. N = 1,527. LL = model maximum log likelihood value (the value shown in bold indicates that a model with the smallest LL value that perfectly fits the data); n-par = number of free parameters estimated in the model; AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = the Bayesian information criterion; SABIC = the sample-size adjusted BIC (the value shown in bold indicates the model with the smallest value); CAIC = consistent AIC; AWE = approximate weight of evidence criterion (the value shown in bold indicates the model with the smallest value); LRTS = likelihood ratio test statistics comparing a current model (k class) to a model with one more latent class (k+1 class); Adj LMR p-value = the adjusted Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test p-value; entropy = a standardized measure of how accurately respondents are classified, ranging from 0 to 1 with higher values representing better classification. 1Model with the smallest value; 2non-significant p-value, indicating the current model with the smaller number of classes is not rejected. Table 3 Posterior Probabilities of Assignment to Latent Trajectory Classes   Note. Average latent class probabilities for most likely latent class membership (row) by latent class (column). After the determination of the optimal solution model, the relative proportions of stalking victims responding “yes” to the items of help-seeking behaviors, given membership in a particular class are displayed in Table 4. Item response probability values greater than .50, which indicate a high degree of class homogeneity, were used to interpret the meaning of the latent classes and assign labels to the latent classes. Figure 1 represents the bar chart of the three-class model where the specific item-class probabilities are plotted on the Y axis and the 15 LCA items are on the X axis (the distribution of the items across the three classes). The horizontal lines on the plot > .50 also indicate that the three classes are characterized by a high degree of class homogeneity. As illustrated in Table 4 and Figure 1, the three classes were identified as stalking victims who (1) asked for help passively, labeled “passive help-seeking group” (49.5%), (2) asked family, friends, and non-professional people for help, labeled “informal help-seeking group” (32.3%), and (3) asked for help actively, labeled “active help-seeking group” (18.3%). Tabla 4 Three-Latent-Class Model of Help-seeking among Stalking Victims (N = 1,459)   Note. 1Recoded from original response categories. 2Item-response probabilities > .50; the probability of a “No” response can be calculated by subtracting the item-response probabilities shown above. Figure 1 Probability of Help-seeking Based on Class Membership (N = 1,459).   Note. This figure represents the profile plots of the three-class model in which the 15 indicators of latent classes are plotted on the x-axis, and the specific item-class probabilitiesare on the y-axis. Class Membership by Covariates The multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether any factors were related to class membership of reaction to stalking-related phenomena (reporting to the police, professional help-seeking, informal help-seeking, and coping strategies) by the stalking victims. Results of the multinomial logistic regression analyses are reported in Tables 5 and 6. Statistically significant logit coefficients of class 3 (“active help-seeking group”) and class 2 (“informal help-seeking group”) were detected in comparison with class 1 (“passive help-seeking group”) as the reference group (in Model 1 and Model 2, respectively). In Model 3, logit coefficients of class 3 (“active help-seeking group”) were estimated, compared to class 2 (“informal help-seeking group”). Tabla 5 Latent Class Regression Model Estimating Direct Effects of Perceptions of Severity on Class Membership in Help-seeking   Note. ML coefficients (b) reported with standard errors and 95 % CI (confidence interval) for the odds ratio (OR). Parameterization using Reference Class 1 (passive help-seeking group). 1Reference group is all other relationships/unable to identify relationship. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Tabla 6 Latent Class Regression Model Estimating Mediating Effects of Emotional Response on Class Membership in Help-seeking   Note. ML coefficients (b) reported with standard errors and 95 % C.I. (confidence interval) for the odds ratio (OR). Parameterization using Reference Class 1 (Passive help-seeking group). 1Reference group is all other relationships/unable to identify relationship. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Model I of Table 5 tested the impact of the variety of covariates related to the seriousness of the offense, conditional on class membership. In Model 1 of Model I, “active help-seeking group” membership, compared to the reference group, “passive help-seeking group”, was significantly and positively related to prior crime record (β = .932, p < .01), both victims’ and others’ experience of being threatened (β = 1.137, p < .001; β = 1.089, p < .05), duration and frequency of stalking (β = .206; β = .452, p < .01), financial loss (β = 1.706, p < .05), and loss time work or school (β = .409, p < .001). Victims whose stalkers had a criminal record, whose stalkers threatened themselves and others, who suffered stalking lasting for months and the most often, who had property damage, and who lost their time at work or school were more likely to ask for help actively, compared to “passive help-seeking group”. Victim-offender relationship (partners) was significantly and negatively related to “active help-seeking group” membership, compared to “passive help-seeking group”, indicating that victims were less likely to ask for help actively for whom stalking took place by other/unable to identify individuals. Females (β = -1.342, p < .001) and white victims (β = .747, p < .05) were significantly more likely than male and other races/ethnicities to be “active help-seeking group” membership, compared to “passive help-seeking group”. In Model 2, comparing “informal help-seeking group” with “passive l help-seeking group”, victims whose stalkers had a criminal history (β = .606, p < .05), whose stalkers attacked others (β = .004, p < .05), who suffered stalking lasting for days and the most often (β = .137, p < .05; β = .460, p < .01) were more likely to ask friends or family for help, compared to “passive help-seeking group”. Regarding victim-offender relationship, victims were less likely to ask friends or family for help for whom stalking took place by other/unable to identify individuals (β = -.638, p < .01), but were more likely for whom stalking took place by strangers (β = .633, p < .05) to ask friends or family for help, compared to “passive help-seeking group”. The likelihood of being “informal help-seeking group”, compared to “passive help-seeking group”, increased with females (β = -.799, p < .001) and the younger (β = -.270, p < .001). Stalkers’ prior crime record, as well as stalking’s duration and frequency were predictive of both “active help-seeking” and “informal help-seeking group” membership, compared to “passive help-seeking group”. In Model 3, comparing “informal help-seeking group” with “active help-seeking group”, victim-offender relationship (partners) and loss time work or school were significant predictors among “active help-seeking group” members, compared to “informal help-seeking group” members. Victims who were stalked by their partners (β = .614, p < .05) and who lost their time at work or school (β = 2.807, p < .001) were more likely to ask for help actively rather than to ask family, friends, and non-professional people for help. Negative emotion variables (emotional distress, angry or annoyed, suicidal thoughts) were added in Model II of Table 6 to examine the direct and mediating effects of negative emotions on class membership. Both “active help-seeking group” and “informal help-seeking group” membership, compared to the “passive help-seeking group”, was significantly and positively related to emotional distress (β = 1.665, β = .739, p < .001, respectively), angry or annoyed (β = .666, β = .665, p < .001, respectively), suicidal thought (β = .276, p < .05, β = .352, p < .01, respectively). Victims who felt distressed, angry/annoyed, and have suicidal thoughts were more likely to be in both groups, compared to the “passive help-seeking group”. There was a significance in the impact of emotional distress between the “active help-seeking group” and “informal help-seeking group” (β = .926, p < .001) but no significant difference in angry or annoyed and suicidal thoughts between the “active help-seeking group” and “informal help-seeking group” in Model 3. Prior crime record was rendered nonsignificant, indicating the full mediating role of victims’ emotional response in the link between those perceptions and class membership of the “active help-seeking group” and “informal help-seeking group”, compared to the “passive help-seeking group”, while financial loss was rendered non-significant for the “active help-seeking group”, compared to the “passive help-seeking group”. However, most covariates related to the seriousness of the offense remained significant, and the impact of some covariates was attenuated after controlling for negative emotion variables. Overall, there was no clear pattern of either partial or full mediation effect. The purpose of the current study was to identify the patterns of help-seeking behaviors among stalking victims and to examine the association between victims’ perceptions and emotional responses to a stalking situation and class membership. Using the basis of survey data from 1,459 SCS samples with the LCA model, a research was conducted to determine whether one can condense the mass of the different help-seeking behaviors of stalking victims into clearly delineated profiles. We found distinct patterns of help-seeking behaviors with different numbers of subgroups, and class differences were also found in terms of victims’ perception of severity and emotional response. Consistent with the proposed Hypothesis 1, the following three groups were identified based on the classification and item probabilities: (1) “passive help-seeking group” (49.5%), (2) “informal help-seeking group” (32.3%), and (3) “active help-seeking group” (18.3%). Our findings are consistent with previous studies that show there are distinct groups of help-seeking strategies among stalking victims (Kaukinen, 2004; Podana & Imriskova, 2016). The finding of this study confirmed that help-seeking patterns among stalking victims are different, and thus, victims are not homogeneous groups in terms of help-seeking behaviors. Victims’ perceptions of a stalking situation’s severity were compared across the latent classes (supporting Hypothesis 2). The overall findings revealed that victims who perceived the stalking situation to be severe were more likely to ask for help “actively”, compared to those asking for help “passively” and seeking help from family and friends (i.e., informal help-seeking group). This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that victims do not seek help until their lives are dangerous (Kim & Ferraresso, 2022; Park & Ko, 2021). The problem is that the perception of violence severity can be subjective, and if victims do not seek help until they think it is dangerous, it might be too late for stalking victims. The rate of stalking perpetrated by current or previous intimate partners is high (Catalano, 2012), and unfortunately, many victims are less likely to take it seriously when the acts are committed by someone they know (McKeon et al., 2014). However, stalking can lead to victims dying or experiencing severe injuries (McKeon et al., 2014, and getting help and having safe plans are very important to prevent their further victimization. Thus, it would be beneficial for potential stalking victims to have access to educational programs to acknowledge the signs of stalking (not just talk about their perceptions) and provide appropriate channels through which to seek help. Regarding victims’ emotional responses, the overall findings indicated that victims who felt distressed, angry/annoyed, and/or have suicidal thoughts, were more likely to ask for help “actively” and seek help from family and friends (i.e., informal help-seeking groups), compared to those asking for help “passively”, supporting Hypothesis 3. This finding is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that emotional distress within their victimization increases help-seeking behaviors among victims (Reyns & Englebrecht, 2014). It is a good sign that people who experience emotional distress are more likely to seek help actively and informally. This means that individuals who are in emotionally vulnerable situations are going to get some help. For those people who seek help from their friends or family it will be very important for the helpers not to ignore victims’ negative emotions and help them to get proper treatment. In addition, not all victims experience negative emotions caused by their victimization immediately and it might take time for some victims to develop those emotional responses. In addition, it does not mean that those people who do not experience emotional distress do not have other negative consequences such as physical health problems (Reidy et al, 2016). Thus, paying special attention to those people who do not have salient negative emotions caused by stalking is important. Regarding the mediating role of victims’ emotional responses, having a prior criminal record was rendered nonsignificant among members of both the “active help-seeking group” and the “informal help-seeking group”, compared to the “passive help-seeking group”. This means that prior criminal records no longer directly predict who will fall into the “active help-seeking group” and “informal help-seeking group” when controlling for emotional responses. Emotional responses play an important role in their help-seeking behaviors among active help-seekers and informal help-seekers. Studies found that young, female victims who were stalked by strangers were more likely to feel emotionally distressed. Similar to the programs for those people who did not report salient emotional responses, programs targeting those groups of people (e.g., young, female, etc.) to provide the right channels to get help are important means for them to overcome their victimization. Limitations Despite the strength of this study, there are several methodological limitations that should be noted. First, this study used cross-sectional data and, thus, the association between victims’ perceptions and emotional responses to a stalking situation and class membership may be bidirectionally but not temporally ordered relationships. Future research utilizing longitudinal data should be considered to better understand causal inferences. Second, due to the nature of the dataset, all variables were measured using self-reported instruments. Thus, underreporting or overreporting among the participants might have played a role. Thus, careful interpretations of the results will be necessary. Conclusion This study identified help-seeking patterns among stalking victims and found that negative emotional responses and the seriousness of victimization predict which help-seeking groups victims will join. Although this is not the first attempt to understand the patterns of stalking victims’ help-seeking patterns and the factors associated with those patterns, this result fills a gap in the stalking research, as not many scholars have paid attention to this phenomenon compared to other types of violence victimization, such as IPV (Cheng et al., 2022). As not all victims utilized the same strategies to deal with their victimization and different factors play a role, this study’s findings can assist with developing strategies for (potential) stalking victims to seek help. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Cho, S., Kim, C., & Gatewood Owens, J. (2023). Understanding of factors associated with reporting to the police, helping seeking, and adopting in self-protection among stalking victims: A latent class analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 32(3), 141-154 https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2023a5 Appendix A Variable Creation Stalking Victimization: requires all three elements

Help-Seeking (1 = yes, 0 = no)

Considering all of these unwanted contacts or behaviors that have occurred over the past year, did you feel…

Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables |

Cite this article as: Cho, S., Kim, C., & Owens, J. G. (2023). Understanding of Factors Associated with Reporting to the Police, Helping Seeking, and Adopting in Self-protection among Stalking Victims: A Latent Class Analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 32(3), 141 - 154. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2023a5

Correspondence: sujung.cho@siu.edu (S. Cho).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS