Beyond the Initial Assault: Characterizing Revictimization in Intimate Partner Violence and Its Implications for WomenŌĆÖs Health

Marina J. Muñoz-Rivas1, Román Ronzón-Tirado1, Juan J. López-Ossorio2, and Natalia Redondo1

1Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain; 2State Secretariat for Security, Ministry of Interior, Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a4

Received 13 July 2023, Accepted 15 January 2024

Abstract

Recent research has emphasized the importance of addressing specific victim-related factors to reduce victims’ vulnerability and prevent future revictimization experiences. This study aimed to analyze the vulnerability profiles of women who were victims of intimate partner violence, including those who had experienced a single incident of violence and those who had endured revictimization. Participants were 338 women with active judicial protection measures registered in the system of support for victims of gender violence (VioGén) in Madrid, Spain. The analysis considered sociodemographic characteristics, victimization history, perceived triggers of violence, women’s responses and feelings, as well as clinical outcomes linked to revictimization history. The study revealed that many victims faced socioeconomic vulnerability. Furthermore, the findings underscored the intricate link between the likelihood of enduring chronic violence and women’s awareness of early indicators of violence risk, their initial responses to aggression, communication skills, and recurrent behaviors in the context of an established violent dynamic. This study offers valuable insights for law enforcement to identify the risk of revictimization. Furthermore, findings raise awareness about the particularly vulnerable situation of some women to repeated victimization experiences and provide relevant information for clinical intervention.

Keywords

Intimate partner violence, Against women, Revictimization, Vulnerability profilesCite this article as: Muñoz-Rivas, M. J., Ronzón-Tirado, R., López-Ossorio, J. J., & Redondo, N. (2024). Beyond the Initial Assault: Characterizing Revictimization in Intimate Partner Violence and Its Implications for WomenŌĆÖs Health. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 65 - 72. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a4

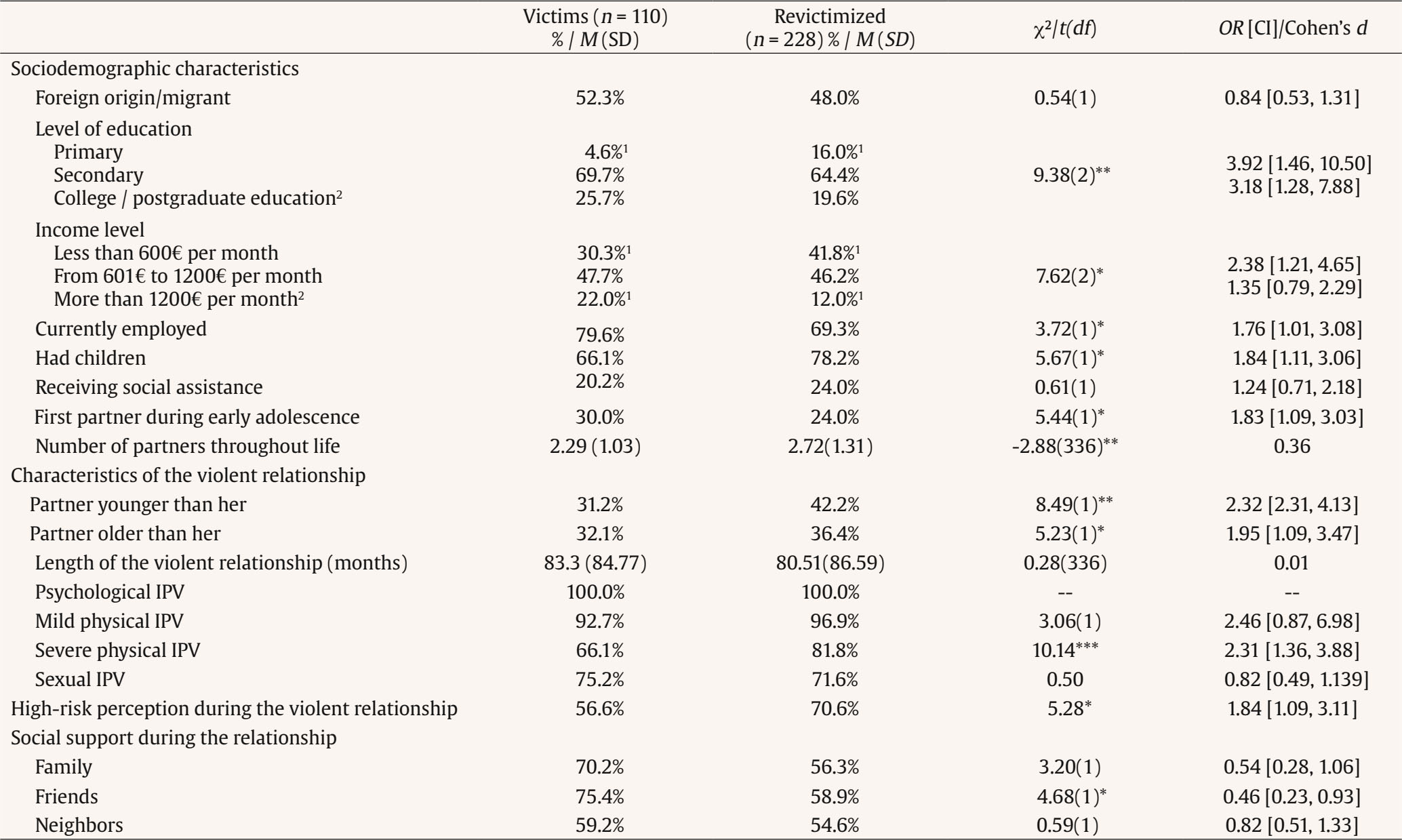

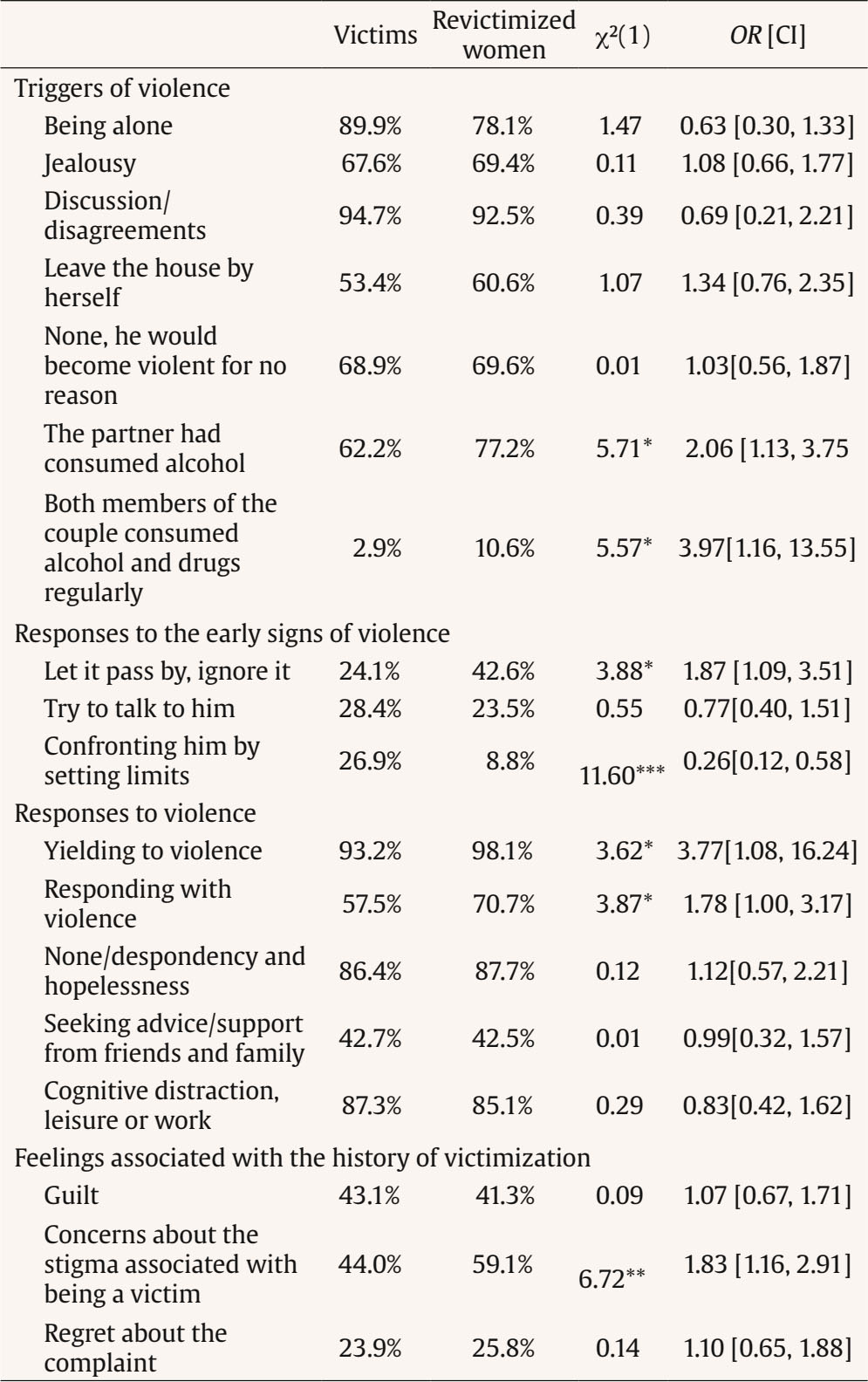

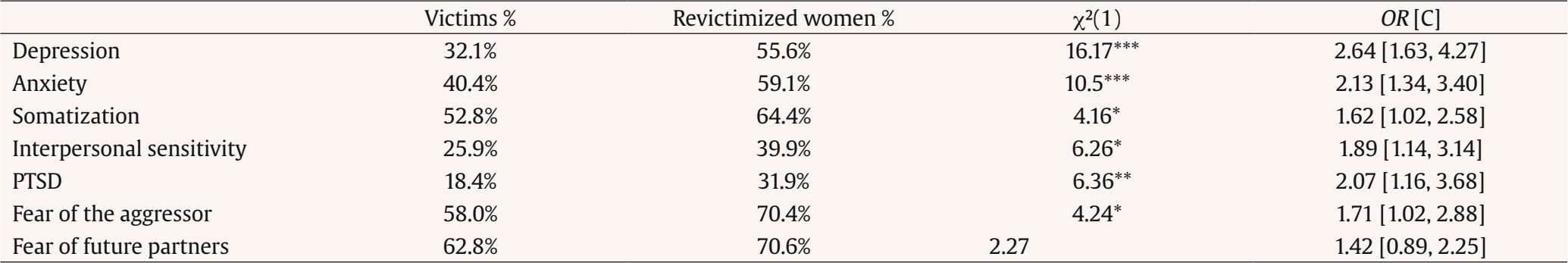

Correspondence: natalia.redondor@uam.es (N. Redondo).Intimate partner violence (IPV) revictimization is a prevalent phenomenon characterized by its chronicity over time. Current studies estimate that between 40% and 60% of women who are victims of IPV experience a new physical or sexual assault perpetrated by their current or former partner, or even a future partner, particularly within the six months following the initial violent event (Iverson et al., 2013; Tomkins et al., 2023). Due to the seriousness of the issue, an increasing number of researchers have become interested in studying the factors associated with the risk of victimization, highlighting the fundamental role of certain characteristics of the aggressors, the culture, and the social context of the victims (Petersson & Strand, 2017; Redondo et al., 2019; Travers et al., 2021). However, a significant portion of studies have neglected the formal analysis of factors associated with victims’ vulnerability. This current knowledge gap hinders the early attention to a significant percentage of women who remain vulnerable even after successfully reporting the aggressor or ending the violent relationship (Cattaneo, & Goodman, 2015; Dardis et al., 2018; Herrero et al., 2018; Orke, 2018). The scarce studies in this field highlight the relevance of specific resources that women possess to perceive the risk they are facing, their motivations to adopt protective behaviors, and the strategies they employ to leave or avoid future violent partners (Cho et al., 2023; Petersson & Thunberg, 2022; Strand et al., 2021). The literature highlights several key vulnerability factors associated with victimization, including a lower socioeconomic status (Cheng & Lo, 2016), lower educational attainment, unemployment, having children, and initiating relationships at an early age. All these factors appear to be indicators of heightened vulnerability that place these women at a high risk of victimization from early adulthood onwards (Kenndy et al., 2018; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2021; Petersson & Thunberg, 2022). In line with this, it has been suggested that to understand the processes of IPV victimization and revictimization it is crucial to figure out aspects such as power imbalances between both members of the couple, marked by factors such as age difference and/or disparities in available economic and social resources (Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2016; Sarway, 2020). Furthermore, it has been noted that revictimization tends to occur among individuals who receive limited informal support from their close family, friends, and neighbors. This lack of support creates significant challenges in terminating the abusive relationship and making a resolute decision to seek formal assistance (i.e., legal, or psychological) to achieve this goal (Katerndahl, et al., 2013). Regarding the history of victimization, the existing results draw attention to aspects related to the duration of the violent relationship or the severity of the received aggression. It has been evidenced that the risk of revictimization increases when the duration of the violent relationship is longer and when the violence is expressed more severely and persistently (e.g., physical and sexual violence), causing intense fear in the victim towards the aggressor, leading them to acquiesce to their demands in order to avoid the escalation of violence or future attacks (Kenndy et al., 2018; Kropp et al., 2010; Robinson & Howard, 2012; Robinson et al., 2018). Finally, it is important to note that victims exposed to repeated violent relationships are those who are more likely to develop mental health problems, particularly depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress (Christ et al., 2022; Iverson, et al., 2013; Stein et al., 2019). Moreover, the presence of pre-existing health issues, which may have developed before or during the course of the violent relationship, can contribute to a victim’s dependence on the aggressor and increase the risk of revictimization. These health problems can create challenges and diminish the victim’s motivation to establish protective behaviors, thus further exacerbating their vulnerability (Kropp et al., 2010; Petersson & Thunberg, 2022). As observed, recent research in this field has demonstrated the importance of attending to certain variables related to the victims to reduce their vulnerability and, more importantly, to prevent them from experiencing new episodes of violence in their lives. However, studies specifically focused on analyzing the detailed individual characteristics and behavioral patterns of women victimized and revictimized by their partners (beyond social and economic aspects) are still very rare. This is likely due to the concern of avoiding any interpretation that could “blame” them for the violence they have experienced (Petersson & Thunberg, 2022; Stein et al., 2019). Although this concern is understandable, due to the historical tendency to blame and socially revictimize victims (Fernández-Romero, 2020), it is important to analyze the characteristics of the victims themselves. This includes examining their unique perception of risk, as well as the development of protective behaviors and strategies utilized to escape the cycle of violence. Such analysis can provide valuable insights to enhance their capacities and improve institutional and professional approaches to prevention, protection, and intervention (Mannell et al., 2014; Waller et al., 2023). Current Study The present study is based on the need to expand the current knowledge of the risk factors associated with IPV victimization and revictimization. It aimed at characterizing the vulnerability profiles of the victims to gain a deeper understanding of their resources and specific needs. The study specifically targeted women who were currently being protected by the Gender Violence Monitoring System (VioGén), a comprehensive monitoring system implemented by the Secretary of State for Security within the Spanish Ministry of the Interior. VioGén serves as a central tool for coordinating various public institutions involved in addressing gender violence cases. The system aims to enhance the care and protection of victims by unifying information, assessing risks, monitoring victims nationwide, and implementing preventive measures through an automated notification subsystem. All the participants had previously filed judicial complaints against their aggressor, leading to court-ordered police and judicial protection measures. Protective orders included prison sentences, restraining orders, telematic devices for the control of compliance with restraining orders, batterers treatment programs for their social reintegration, police monitoring, and risk assessment of women, as well as periodic phone calls to know the status and needs of women. The participation in the study was entirely voluntary and under their explicit consent. The study explores various aspects, including socio-demographic characteristics (such as country of origin, level of education, income, presence of children, and age at the onset of their first relationship), variables related to the abusive relationship (such as the age difference with their former partner, social support during the relationship), triggers of the assaults (such as substance abuse, arguments, and jealousy), responses to the assaults (such as compliance or responding with violence), and clinical consequences based on their history of revictimization (including anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and fear). Specifically, the study aimed to answer the following questions: 1. What vulnerability factors characterize women victims of a single event of IPV? and 2. What vulnerability factors characterize women victims of IPV with at least one experience of revictimization? Overall, this study aimed to provide valuable and specific knowledge to improve the understanding of revictimization as a complex phenomenon. Moreover, it aimed at facilitating targeted improvements in early detection, police monitoring, prevention interventions, and addressing the clinical consequences associated with revictimization. Ultimately, the study sought to promote greater social awareness regarding the particularly vulnerable position in which certain women find themselves about the risk of experiencing further victimization events (Costanza & Cinquegrana, 2021; Petersson & Thunberg, 2022; Strand et al., 2021). Participants The study included 338 women aged between 18 and 69 years (M = 38.13, SD = 11.15, mode = 30 years), victims of IPV, and with active police protection measures. These women were representative from the 21 districts of the city of Madrid. Of these, 50.9% were Spanish, while 49.1% had an immigrant background, with origins including Latin America (41.1%), Eastern Europe (5.3%), Africa (1.5%), and Asia (1.1%). In terms of educational level, 12.7% of the women had completed primary education, 66.0% had secondary education, and 21.3% had university or postgraduate studies. Among the participants, 32.4% had suffered a single violent event associated with a report of intimate partner violence, while the remaining 67.6% had been revictimized by the same partner (39.3%) or by multiple partners (28.3%). The number of reported intimate partner violence complaints ranged from 1 to 20 (M = 2.85, SD = 2.96), while the number of former partners associated with these complaints varied from 1 to 5 (M = 1.29, SD = 0.65). Data collection for this study was conducted from April 2020 to June 2022. Inclusion criteria for participants were as follows: a) residency in Madrid, b) being at least 18 years old, and c) having an active judicial sentence associated with police protection measures. Additionally, to ensure the representativeness of the sample encompassing women with diverse histories of victimization, potential participants were selected based on one of the following three profiles: a) victim: women with a single complaint recorded in the VioGén system since 2014, b) multivictim: women with multiple complaints against the same aggressor recorded in the VioGén system, and c) polyvictim: women with multiple complaints against different aggressors recorded in the VioGén system. Measurements Sociodemographic and Relationship Characteristics Women’s sociodemographic and relationship characteristics were gathered using a series of structured multiple-choice questions. The variables examined included income level, educational attainment, current employment status, and number of children. Additionally, the characteristics of the violent relationship that led to the most recent police report were examined, including the duration of the violent relationship, age difference with the partner/ex-partner, and perceived social support during the violent relationship. Type of Aggression Experienced by the Victim The frequency of victimization by the partner during the last year of the relationship was measured using the Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS-2; Strauss et al., 1996). The scale consisted of 26 Likert-type items from the original scale including 8 items to measure psychological victimization, 11 items for physical victimization, and 7 items for sexual coercion. Participants rated the frequency of victimization on a 6-point response scale ranging from 0 (never happened) to 5 (occurred more than 20 times in the last year). Total scores were calculated for each type of violence by summing the items. The total scores for each dimension were dichotomized to determine the prevalence of each type of aggression in the relationship (0 = participant scored 0 on the dimension, 1 = participant scored 1 or more on the dimension). Previous studies have confirmed the factorial structure of the CTS-2 in diverse cultural samples (Strauss et al., 2004). Additionally, the CTS-2 has demonstrated satisfactory criterion validity by correlating with theoretically relevant variables in general and clinical samples (Chapman & Gillespie, 2018). In the present study, the internal consistency for each dimension was acceptable, ranging from α = .69 to α = .81, with an ωT = .93. Perceived Triggers of Violence A multiple-choice question was formulated to explore the victims’ perception of the possible reasons behind the violent acts they experienced (“What motived/triggered, led to, or facilitated your partner/ex-partner’s act of violence against you? Check all the responses that apply from the following list”). Response options included being alone with the aggressor, the aggressor being under the influence of alcohol or drugs, the victim being under the influence of alcohol or drugs, going out alone, jealousy, arguments, and/or others. Response options were selected based on a prior literature review on the topic (Neal & Edwards, 2017). Women who checked “other” could provide their own responses on the questionnaire. Responses to violence Women’s responses to episodes of violence were assessed using the Gender Violence Response Index (I-RVG). This index was developed specifically for this study and comprised 29 items, of which 26 items were organized into six principal components to measure women’s responses during and after episodes of violence: 1) seeking support and assistance, 2) experiencing feelings of hopelessness and resignation, 3) seeking legal support, 4) seeking distraction through leisure and work, 5) avoiding confrontation and acquiescing to violence, and 6) responding with violence. Additionally, the index included three specific items to measure responses to early risk indicators. The two response options for the 29 items indicated whether the response was utilized during the duration of the violent relationship. The scale’s psychometric properties were analyzed through a principal component analysis, confirming the grouping of the 26 items into six components with an average associated eigenvalue of 3.09, all exceeding the value of 1, and an acceptable root mean square residual (RMSR) value of .07. A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted over a factorial analysis (AF) to effectively reduce the dimensionality of the dataset while preserving maximum variability. This approach enabled data summarization into categories derived from linear combinations of the original variables, facilitating data interpretation and management (Ringnér, 2008). A matrix of tetrachoric correlations was utilized to enhance the performance of PCA, as this method outperformed Pearson correlations when dealing with dichotomous data (Debelak & Tran, 2013). Subsequently, response distribution and correlations between components were assessed. Criterion validity was evaluated by examining the relationship between inventory components and theoretically relevant variables, including aggression typology and frequency, revictimization measured through police reports, and relationship duration. Intimate partner violence consequences A number of measures were employed to evaluate the severity of the consequences associated with victimization by intimate partner violence. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Severity Scale-Revised (PTSD; EGS-R; Echeburúa et al., 2016) was used to evaluate the severity of PTSD symptoms in the sample. This scale consisted of 21 Likert-type items with four response options (0 = never to 3 = 5 or more times per week). The 21 items are grouped into four symptom clusters, namely re-experiencing, avoidance, negative cognitions/mood alterations, and increased arousal/reactivity in accordance with the DSM-V diagnostic criteria. The scale’s factorial structure has been confirmed in a Spanish sample and has demonstrated discriminant and predictive validity (Echeburúa et al., 2016). In the present study, the dimensions measured by the EGS-R exhibited satisfactory internal consistency values ranging from α = .79 to α = .85, and the omega index ranged from ω = .81 to .87. The Spanish version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21; Antúnez & Vinet, 2012) was used to measure the symptomatology of depression, anxiety, and stress in the sample. Each dimension of the DASS-21 consisted of 7 Likert-type items with response options ranging from 0 to 3 (0 = not at all, 1 = a little, 2 = quite a lot, 3 = very much). The depression dimension assessed dysphoria, lack of interest, anhedonia, and self-depreciation. The anxiety dimension evaluated autonomic arousal, situational anxiety, and subjective experience of anxious affect. The stress dimension measured non-specific persistent arousal, irritability, and difficulty in relaxing. In the present study reliability indices for each dimension were α = .89 and ω = .90 for anxiety, α = .92 and ω = .93 for depression, and α = .90 and ω = .91 for stress. As suggested by previous validation studies of the DASS-21 in Spanish-speaking samples (Román et al., 2017), the clinical cutoff scores for the depression scale were 6 or higher, 5 or higher for anxiety, and 6 or higher for stress. The Symptom Assessment Questionnaire (SA-45; Davison et al., 1997) is a self-report instrument with Likert-type items comprising five response options (0 = not applicable to 4 = very much/extremely) to measure the frequency of psychiatric symptomatology. Specifically, two dimensions of the SA-45 were utilized to address the objectives of this study: somatization, which encompasses the presence of physical symptoms that cannot be explained from a medical perspective and significantly disrupt the individual’s daily life, and interpersonal sensitivity, which involves the presence of persistent feelings of inferiority and inadequacy. The factorial structure of the scale has been confirmed in clinical and non-clinical Spanish samples (Holgado-Tello et al., 2019). In the present study, both dimensions show satisfactory consistency indices for somatization α = .88 and ω = .88), and interpersonal sensitivity (α = .83 and ω = .86). Procedure The present study was conducted in collaboration with the Gender Violence, Studies, and Training Department, which manages the Monitoring System for Gender Violence Cases (VioGén) of the State Security Secretariat (Ministry of the Interior of Spain). The main objective of this collaboration was to better understand the profile and needs of women assisted by the system to improve police care and protection measures, particularly in cases at greater risk of revictimization. After establishing initial contact between this department and the research team, police officers were requested to inform victims with active judicial measures registered in VioGén about the possibility of voluntarily participating in a study on profiles and consequences related to intimate partner violence. Women who agreed to participate in the study were contacted by members of the research team via telephone to schedule an appointment to complete the evaluation protocol. The assessment lasted approximately 90 minutes, either at victims’ homes or at the police stations responsible for their protection. All procedures conducted in this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Madrid (CEI-941720) and complied with regulations regarding the treatment of personal data. Table 1 Sociodemographic Characteristics and Aspects Related to the History of Victimization   Note. 1typified residuals ± 1.96; 2reference category. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Data Analyses Firstly, the internal consistency coefficients of the scales used were calculated using Cronbach’s alpha and omega coefficients. Subsequently, descriptive statistics were estimated for the studied variables in the total sample. The participants were then classified into two mutually exclusive groups: 1) “victims,” which included women who had only one report of intimate partner violence registered in the VioGén System and who also responded “no” to the question “Have you previously been in another violent relationship?”, 2) “Revictimized,” which included women who had more than one report of intimate partner violence registered in the VioGén System or who responded “yes” to the question “Have you previously been in another violent relationship?”. Then, differences between the groups (“victim” = 0 vs. “revictimized” = 1) were estimated. The chi-square statistic and the odds ratio associated with revictimization were calculated for each of the variables. A power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007) indicated that with two groups 1 degree of freedom, alpha set at .05, and our sample size of 338, power exceeded .95 to detect an effect size of w = .20 or bigger. The results indicated that approximately 84% of women had incomes below 1,200 euros per month, and in 78.7% of cases they had completed only secondary studies. About one-third of the women were unemployed, and in 74% of cases they had at least one child (ranging from 1 to 7 children). On average, the violent partner relationship was the second formal relationship experienced by women, with a mean duration of 7.4 years (range: 1 month to 50 years). In 38.5% of cases, women established the romantic relationship with a partner younger than themselves, while in 35.2% of cases, the partners were older. Throughout the course of the relationship, 100% of women had been victims of psychological aggression, 95.6% had experienced mild physical abuse, such as punches and slaps, 76.6% had been victims of severe physical abuse, including beatings, attempted strangulation, and threats with weapons, and 72.8% had suffered sexual assaults. During the relationship duration, 62% of women reported receiving support or advice from their family, 61.9% from their friends, and 28.4% from a neighbor (Table 1). Regarding the perceived triggers of violence, most women identified conflicts and disagreements between the couple as a trigger for violence (93.2%), followed by jealousy associated with knowing or suspecting that the victim had spoken to other men (68.6%) or had been outside of the home alone (58.0%). Furthermore, in 71.9% of the cases women identified their partners’ consumption of alcohol or drugs as triggers for violence, and 8% mentioned that both members of the couple had consumed alcohol or drugs before the violent incidents. However, 69.4% of women stated that in most cases there was no specific situation that triggered the violence. They mentioned that their partners could become “violent at any moment without any apparent reason” (Table 2). Table 2 Triggers of Violence, Responses to Violence, and Feelings Associated with the Victimization History   *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. When asked if they recalled any behavior or comment that indicated their partner’s potential for violence, 77.3% confirmed that they had suspected it from the beginning of the relationship. However, 38% chose to overlook it, 24.4% attempted to address the issue through conversation, and only 14.6% attempted to establish boundaries. Once the pattern of violence was established, women’s responses to the aggression involved yielding, trying to keep everything calm (96.1%), doing nothing due to feelings of despair and hopelessness (87.4%), or seeking distraction by avoiding thoughts about the situation or focusing on work (85.8%). Additionally, in 66.8% of the cases, on some occasions, women had attempted to respond with verbal or physical aggression. Regarding feelings associated with the history of revictimization, 75.0% of women reported feeling guilty about what had happened, 25.0% of the victims regretted filing the report due to the negative consequences it had on their lives, and 75.7% expressed concerns about the stigma associated with being recognized as a victim of intimate partner violence. Finally, concerning their health status (Table 3), many women met clinical criteria for depression (48.5%), anxiety (53.6%), and somatization (61.0%). Furthermore, 27.5% met the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder and 35.4% experienced a persistent sense of inadequacy and insecurity. Additionally, 75.7% expressed fear of experiencing further aggression from their former partner, while 58.6% were concerned about the potential harm their former partner could inflict on their children or other close family members. Characteristics Associated with Revictimization Experiences Women who were revictimized were more likely to have disadvantaged socioeconomic characteristics (Table 1). Specifically, revictimized women had a higher likelihood of having completed only primary education (OR = 3.92), having a monthly income below €600 (OR = 2.38), being unemployed (OR = 1.76), or having children (OR = 1.84). Additionally, revictimized women had a higher number of lifetime partners, t(336) = -2.88, p < .01, d = 0.36, and were more likely to have established their first romantic relationship during early adolescence (OR = 1.83). Regarding the characteristics of the violent relationship, it was identified that revictimized women were more likely to establish a relationship with a younger person (OR = 2.32), and had a higher prevalence of experiencing prior severe physical aggressions (OR = 2.31). Furthermore, revictimized women tended to lack support from friends during the violent relationship and, in general, perceived a high level of risk to their lives throughout the duration of the violent relationship (OR = 1.84). Although triggers of violence and responses to aggression reported by both victims and revictimized women were similar, certain differences were found between the profiles of both groups of women (Table 2). Specifically, revictimized women were more likely to inform as trigger of violence that: a) the perpetrator had consumed alcohol or drugs (OR = 2.06), b) both members of the couple had consumed psychoactive substances during the relationship (OR = 3.97), and c) women had chosen to dismiss the initial signs of violence without attributing importance to them (OR = 1.87). Once the violent dynamics were established, revictimized women tended to respond more to the assaults by yielding and trying to keep everything calm (OR = 3.77). Furthermore, they had in general a higher level of concern regarding the stigma associated with being a victim of intimate partner violence (OR = 1.83) and tended to respond to the aggressions with verbal or physical violence in an attempt to stop them (OR = 1.78). However, confronting and setting boundaries in response to the initial signs of violence was more characteristic of women with a single experience of victimization (OR = 0.26). Finally, regarding the clinical characterization (Table 3), women with a history of revictimization had an increased risk of experiencing clinical symptoms of depression (OR = 2.64), anxiety (OR = 2.13), somatization (OR = 1.62), and post-traumatic stress disorder (OR = 2.07). They also exhibited higher levels of interpersonal sensitivity (OR = 1.89) and fear of future experiences of victimization by the ex-partner (OR = 1.71). The results of this study have demonstrated the close relationship between certain characteristics of women who are victims of intimate partner violence and their increased risk of revictimization, even after successfully reporting or ending a previous violent relationship. Specifically, it has highlighted the socio-economic vulnerability faced by many victims of intimate partner violence, as well as the link between the risk of chronicity of violence and the level of alertness of women regarding initial indicators of violence, their initial responses to the assaults, communication skills, and frequent behaviors once the violent dynamics were established. Specifically, this study has enabled the identification that the romantic relationships of women attended to by the Law Enforcement Agencies [Fuerzas y Cuerpos de Seguridad – FFCCS] were mostly relationships with a chronic history of violence, lasting an average of over 7 years, and in some cases up to 50 years. In almost 80% of the cases victims identified the presence of risk indicators or “mild” violent behaviors from the beginning of the relationship. However, they did not report the assaults until they had significantly escalated in severity and frequency. As findings confirm, many women who are victims of intimate partner violence decided to keep the abuse a secret, perhaps as a survival strategy in the face of the adversity and uncertainty they encounter daily (Costanza & Cinquegrana, 2021). Currently, the police and clinical response to the violent reality that many women experience is limited. Early attention to victims is rare and the actual number and severity of abuses are certainly much higher than estimated based on the number of reports (Strand et al. 2021; Viera-Pinto et al., 2022). In this regard, it was identified that only 14% of women communicated their discomfort and rejection to their partners in response to initial signs of violence. Most women, once they found themselves immersed in violent dynamics, tended to respond to the attacks by yielding, evading, or trying to maintain a sense of calm. Many of these women perceived that their partners could become violent “for no reason”, and without them having any control. It is important to understand that this behavioral pattern of women should not be interpreted as a passive or permissive role in the face of aggression, but rather it needs to be seen in relation to the high vulnerability that these women are experiencing (Iverson et al., 2013; Petersson & Thunberg, 2022). On one hand, it is important to consider the factors that contributed to the low initial response rate to early indicators of violence. Aspects such as communication styles, emotional self-regulation, and conflict resolution skills of women may have played a significant role in justifying the aggression and their lack of response to the violence. Exploring these factors, along with potential cognitive dissonance in the face of early signs of violence and the perception of stigma associated with being a victim, appears to be crucial elements to assess and address in women who are victims of intimate partner violence, as well as in their perception and management of risk (Martín-Fernández et al., 2022; Nicholson & Lutz, 2017; Robertson & Murachver, 2006). On the other hand, it is not surprising that nearly 90% of the interviewed women report reaching a point of despair and hopelessness, with over 80% continuing to experience fear of the aggressor, despite having current police protection measures. Over time, these women, who most likely had never been taught how to exit a violent relationship, and whose attempts had, in the short term, yielded negative outcomes such as an escalation of violence, may have experienced a decline in motivation and a narrowing range of behaviors employed to confront aggressions. This learned helplessness would partially explain the markedly submissive behavior and reluctance to leave the violent relationship documented in previous studies (Bargai et al., 2007), as well as the expectation/normalization of violence and an internal attribution style of victimization (Redd, 2019). Even though the profile and characteristics of the victimized and revictimized women were quite similar, it was identified that, as suggested by previous literature, women who experience greater economic precariousness, social isolation, and have children are those at higher risk of revictimization (Cheng & Lo, 2015; Katerndahl, et al., 2013; Pineda et al., 2023). These data confirm that the chronic victimization of these women often forms part of a broader reality characterized by disadvantage and widespread social exclusion. It should not be assumed that, after filing a report, the woman will have the ability to end the relationship. The report is likely the beginning of a longer process, conditioned by factors such as a lack of economic resources to sustain themselves or fear that the perpetrator may harm the children, especially when joint custody is maintained, which can significantly limit women’s margin of action and their ability to distance themselves from the aggressor. Victims of intimate partner violence may require specific services to help strengthen their employment situation and protect their children (Petersson & Thunberg, 2022). In this way, the importance of maintaining regular communication between the personnel of the law enforcement agencies and intimate partner violence victims is highlighted, in order to provide them with the necessary assistance resources, taking into account the diverse supports that may be required for managing complex cases. It is noteworthy that one of the factors significantly associated with the risk of revictimization was women entering a relationship with a younger partner, as well as starting their first relationship at an earlier age or having a higher number of past relationships. These findings, rather than contradicting previous studies on the significance of power and control inequity of older men over younger victims (Ruiz-Pérez et al., 2017; Sarway, 2020), complement the landscape regarding the potential effect of age differences on IPV dynamics. These data point to the importance of the role that the level of maturity and emotional development of the partners could play in addressing conflicts and establishing balanced relationship dynamics. Additionally, they highlight the role that previous victimization experiences could have on the self-perception of the victims and, consequently, on the development of specific relational patterns during the partner selection process (Burton et al., 2009; Herrero et al., 2018; St. Vil et al., 2021). As expected, revictimized women exhibited higher clinical symptoms of depression, anxiety, somatization, PTSD, and interpersonal sensitivity (Kropp et al., 2010; Petersson & Thunberg, 2022; Vilariño et al., 2018). These mental health problems, in addition to likely being consequences of abuse, could be related to the observed tendency in a high percentage of women to remain in the violent relationship, feeling less motivated or capable of coping with adversity. A similar case is substance use, which may be an attempt by more vulnerable women to cope with the distress resulting from the re-experiencing of continuous acts of violence. Furthermore, this behavior, in addition to representing a health issue, was one of the main triggers of violence perceived by the victims, confirming the close relationship between substance use and revictimization (Cole et al., 2018; Lipsky & Caetanao, 2011). Table 3 Clinical Consequences Due to the History of Revictimization   Note. PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; Fear of the aggressor = fear of future victimization experiences by the same aggressor.; Fear towards future partners = fear of future victimization experiences by future partners; % = percentages of women in each group that displayed clinical levels of each consequence. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Limitations Despite the notable contributions of the present study, the findings described should be interpreted considering the following limitations: the sampling was conditioned to active cases in the VioGén System, which may compromise the generalizability of the findings to other samples of women without police protection or belonging to different cultures. Specifically, women who participated in this study might have different experiences and severity of IPV victimization than women who had never attended to the judicial system. Furthermore, women who filed a complaint due to IPV may exhibit distinct personality characteristics and motivations when participating in this study, in contrast to those who have not sought judicial support or those who were contacted but chose not to participate. Additionally, it is recommended that future studies analyze, through a longitudinal design, the potential effect of confounding variables on the direction and evolution of the relationships described in this study, which will allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the revictimization processes. Conclusions This study explored the complex factors contributing to the victimization and revictimization of women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) in Spain. The findings revealed that socioeconomic vulnerability and isolation played a significant role in perpetuating the cycle of violence. Additionally, the study highlighted the importance of women’s awareness of IPV, their initial responses to aggression, their communication skills, and their ability to recognize and escape abusive dynamics. Despite numerous public awareness campaigns aimed at promoting gender equality and eradicating IPV, many participants in the study struggled to recognize early signs of violence. This lack of awareness often led to responses, such as yielding, evading, or keeping everything calm, which facilitated the escalation of the abuse. Moreover, revictimized women faced challenges in establishing boundaries and sometimes lacked the assertive communication skills necessary to effectively address deviant behaviors or initiate a separation from their abusive partners. These findings underscore the need to adapt current clinical, judicial, and social interventions to better address the unique needs and heightened risk of revictimization faced by women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV). Such interventions should encompass early identification of clinical symptoms and prompt treatment to address mental health issues, providing women with the necessary support to overcome their challenges. Additionally, interventions should prioritize equipping women with tailored resources that respond to their particular vulnerabilities and requirements, which could include effective communication skills, conflict resolution strategies, or emotional regulation techniques, depending on the case. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Authors’ Contributions All authors contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, formal analysis, and writing. Cite this article as: Muñoz-Rivas, M. J., Ronzón-Tirado, R., López-Ossorio, J. J., & Redondo, N. (2024). Beyond the initial assault: Characterizing revictimization in intimate partner violence and its implications for women’s health. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 65-72. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a4 Funding: This work was supported by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain (Grant number: PGC2018-096130-B-I00) and the funding for the predoctoral contract FPI (PRE2019-091184). |

Cite this article as: Muñoz-Rivas, M. J., Ronzón-Tirado, R., López-Ossorio, J. J., & Redondo, N. (2024). Beyond the Initial Assault: Characterizing Revictimization in Intimate Partner Violence and Its Implications for WomenŌĆÖs Health. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 65 - 72. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a4

Correspondence: natalia.redondor@uam.es (N. Redondo).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS