Associations between Demographic Factors and Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration and Victimization: A Meta-analysis

Paul A. Zehr, Chelsea M. Spencer, Mariah Moore, and Adi Siegmann

Kansas State University, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a11

Received 14 January 2025, Accepted 29 April 2025

Abstract

Objective: Sexual intimate partner violence (SIPV) is a significant public health concern of global importance. This meta-analysis sought to examine the relationship between demographic factors and SIPV perpetration and victimization. Method: The database searches identified a total of 143 articles to be included in the meta-analysis. Comprehensive meta-analysis 3.0 was used to calculate aggregate effect sizes (Pearson’s r) for the relationship between demographic variables and SIPV exposure. Variables were examined for SIPV perpetration and victimization and were separated between male and female samples. Results: There was a significant relationship between SIPV victimization and being bisexual (r = .25, p < .001), LGBTQ (r = .21, p < .001), female (r = .19, p < .001), and disabled (r = .19, p < .001). Lower income (r = .07, p = .001), lower education (r = .06, p < .001), and younger age (r = .04, p < .001) also correlated with SIPV victimization. Being married (r = -.08, p = .027) was identified as a protective marker against SIPV victimization. Identifying as female (r = -.17, p = .003) had a negative association with SIPV perpetration. Conclusions: The current study found that several demographic factors are significantly related to increased risk of SIPV perpetration and/or victimization, while few have a protective effect.

Keywords

Sexual IPV, Demographics, Risk markers, Meta-analysisCite this article as: Zehr, P. A., Spencer, C. M., Moore, M., and Siegmann, A. (2025). Associations between Demographic Factors and Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration and Victimization: A Meta-analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 137 - 149. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a11

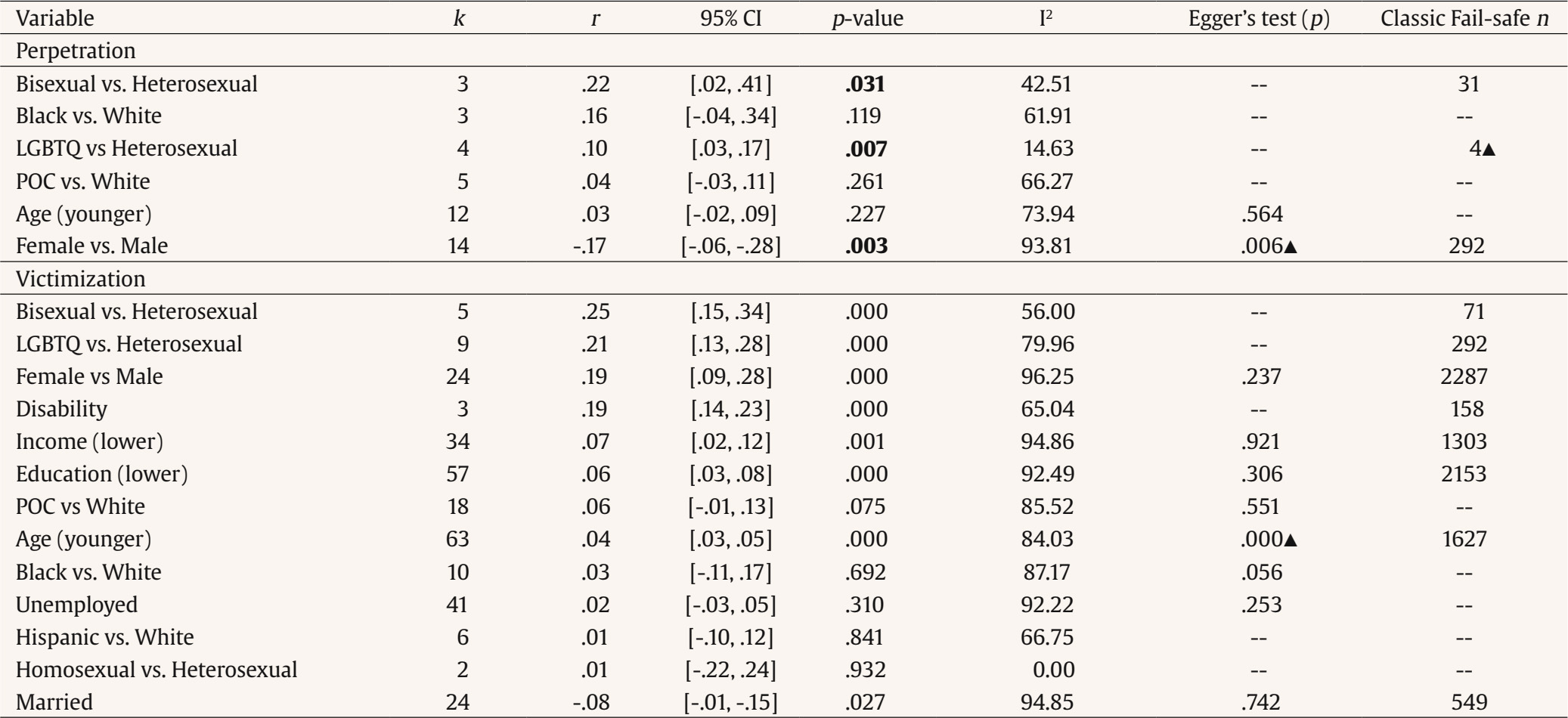

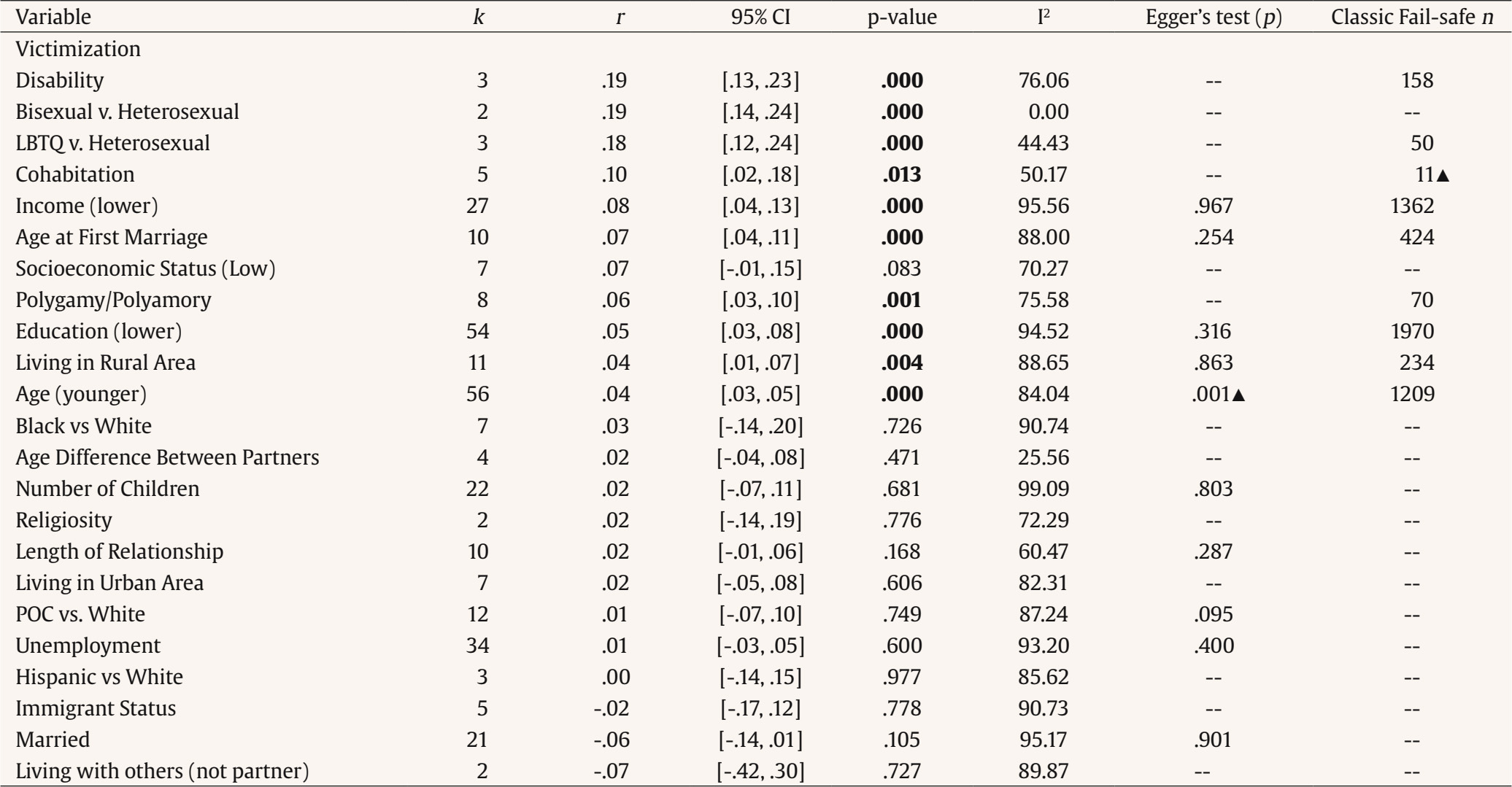

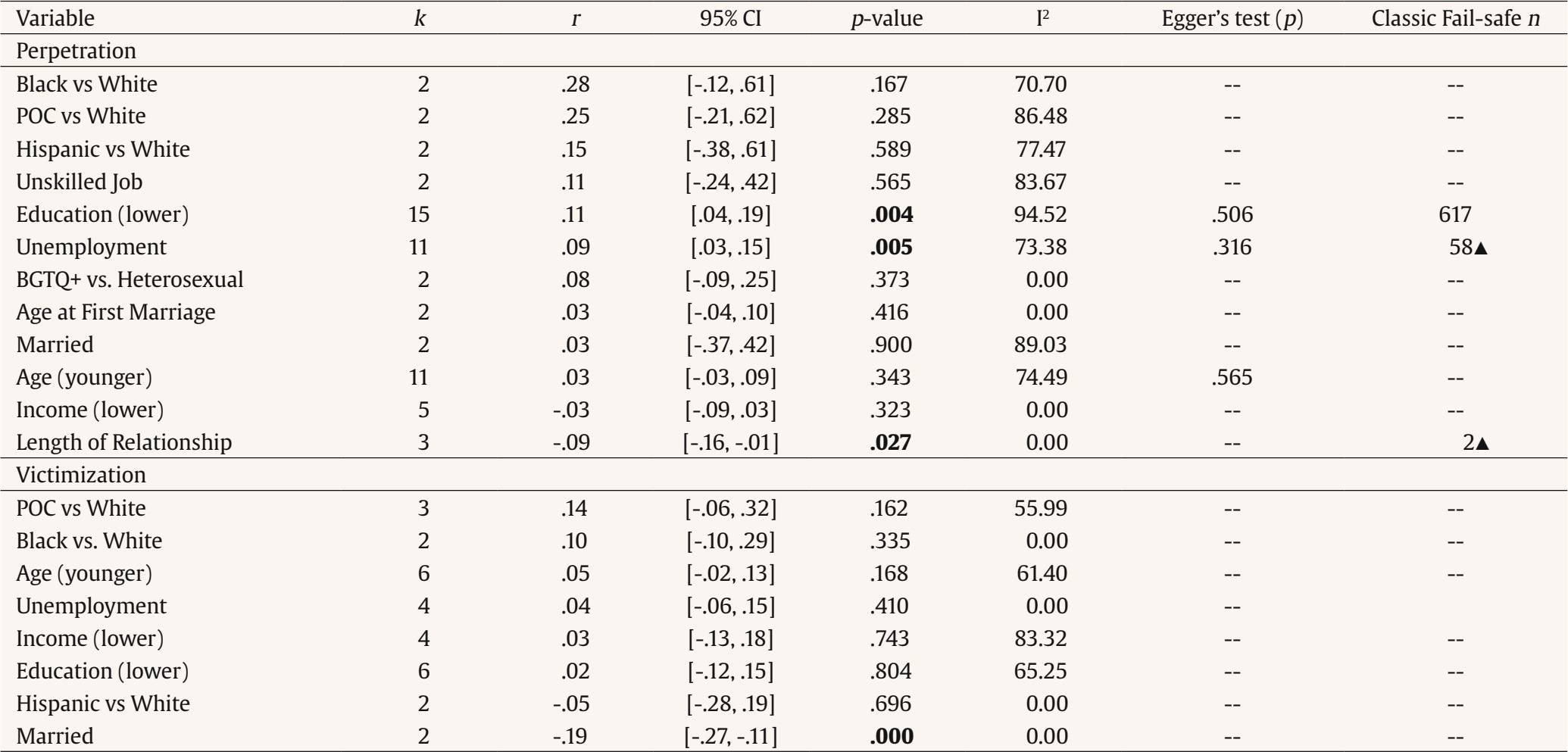

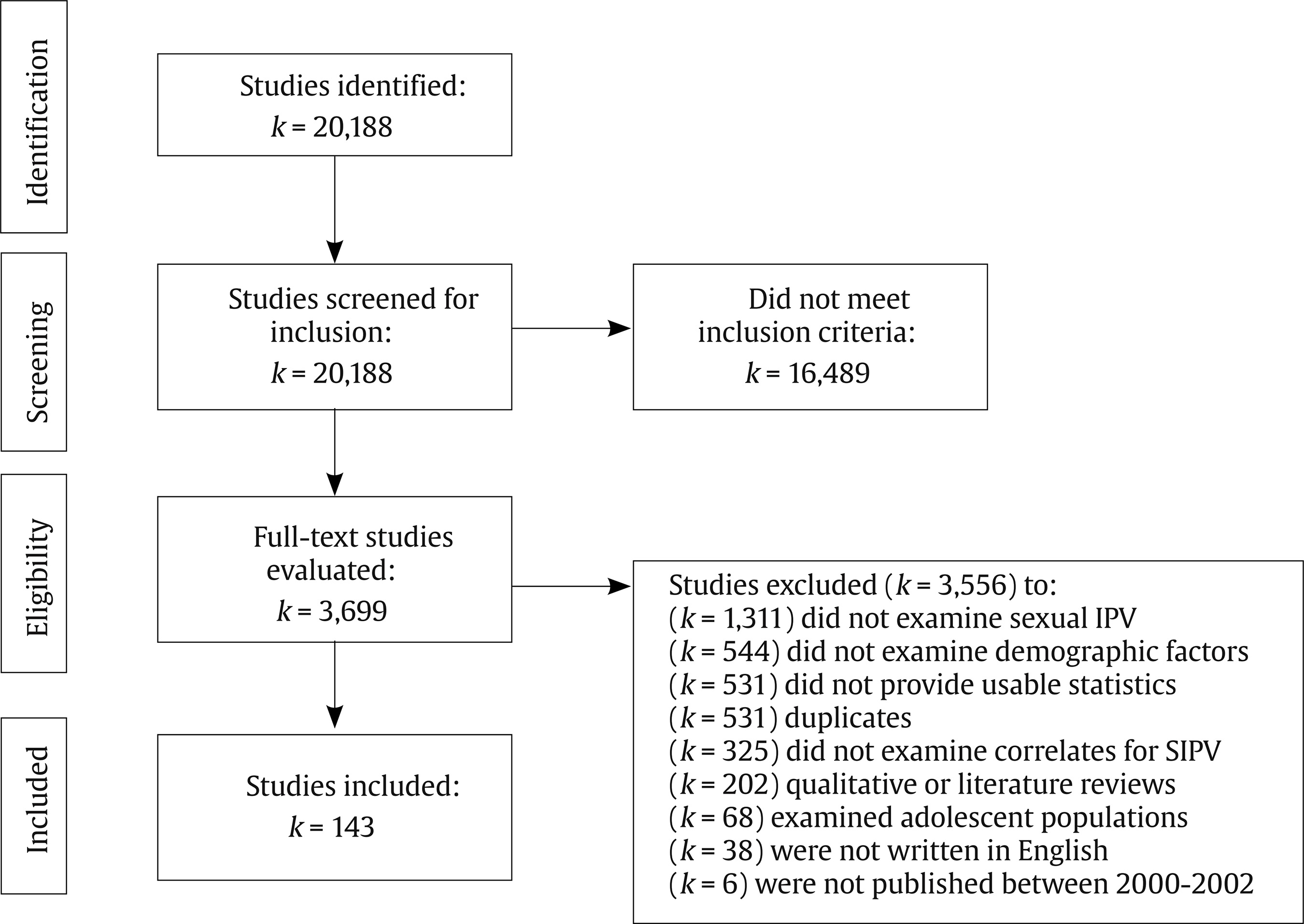

Correspondence: pazehr@ksu.edu (P. A. Zehr).Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a major public health concern affecting a significant portion of the global population. IPV occurs in many types of intimate relationships and can include psychological aggression, physical violence, and sexual violence. Recent global prevalence estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO, 2014) show that 27% of women of reproductive age (15-49 years old) have experienced physical or sexual IPV in their lifetime (2018). Previous global estimates of IPV victimization as high as 37% have been reported in specific regions. Other national studies which include psychological IPV show that almost half of all women (47.3%) and more than 2 in 5 men (44.2%) have experienced some form of IPV in their lifetime (Basile et al., 2022). This high prevalence is particularly concerning due to the deleterious effects of IPV on other aspects of health. The WHO (2014) found that female victims of IPV are 16% more likely to have a low birthweight baby, 1.5 times more likely to acquire human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and 4.5 times more likely to attempt suicide. In a recent U.S. study, a significant percentage of victims sustained physical injuries (1 in 3 women, 1 in 5 men) or needed medical attention (1 in 8 women, 1 in 23 men) after exposure to IPV. Victims also developed mental health concerns, including generalized fear and symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Leemis et al., 2022). Physical and mental health injuries associated with IPV accrue significant costs like emergency room visits, contact with law enforcement, and increased use of health care services over time (Walby & Olive, 2014). All of these put a significant strain on personal and public resources. Sexual intimate partner violence (SIPV) is a complex category of nonconsensual activities in which the victim is raped, sexually assaulted, or coerced by their intimate partner. Though globally representative data rarely separate SIPV from physical IPV, data from the U.S. show that 39.1% of women and 1 in 8 men reported rape victimization in their lifetimes. In addition, 58.3% of women and 45.8% of men experienced lifetime sexual coercion by their partners (Basile et al., 2022). Adverse effects of SIPV include injury, transmission of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and unwanted pregnancy (Basile et al., 2022). SIPV victims are also at higher risk for other forms of IPV, including stalking, physical abuse, and psychological aggression (Krebs et al., 2011). In addition to physical health risks, previous research shows that SIPV is associated with an increased risk for mental health diagnoses such as PTSD, major depressive episodes (MDE), and substance use (Zinzow et al., 2012). Taken together, these effects represent a serious threat to public health. This study aims to examine demographic factors that correlate with individuals’ risk for SIPV, both as victims and as perpetrators. In contrast to previous research, this meta-analysis separates SIPV from physical IPV in international samples. Demographic Factors and SIPV A range of demographic factors have been found to correlate with SIPV perpetration and victimization. Regional and national studies have found that race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, disability status, and other demographic characteristics are significantly related to the risk of SIPV (Basile et al., 2022; Breiding et al., 2014; Kebede et al., 2021; Kwagala & Galande, 2022). The current study is crucial because demographic factors are frequently captured by health organizations and governmental bodies. This means any correlations found between SIPV and demographic information can be important in establishing early interventions in the public health sphere. In addition, previous globally representative studies have rarely separated SIPV from physical IPV, which highlights a significant advantage of the present study. Race and sexual identity are significant markers for the prevalence of sexual violence. For instance, among American women, those who identify as multiracial, American Indian/Alaska Native, and non-Hispanic Black are at highest risk for sexual violence (Basile et al., 2022; Breiding et al., 2014). Lesbian victims have reported lower rates of contact sexual violence (CSV) by their partners than heterosexual women, yet bisexual female victims have reported higher prevalence than both. Gay men have also experienced higher rates of CSV victimization than heterosexual men (Chen et al., 2023). Studies have also shown that income level, employment, and disability status have some relationship to IPV risk. Kebede et al. (2021) found that high income correlated to lower risk of physical IPV in a multi-country study. Other national samples have demonstrated that higher risk of SIPV victimization is often correlated with low income, though moderated by complex factors such as the perpetrator’s education and which partner has a higher income (Dildar, 2021; Larsen et al., 2021). Multiple studies have reported that higher rates of female employment increase the risk of IPV victimization, particularly if the perpetrator is unemployed (Bhalotra et al., 2021; Bourey et al., 2022; Dhanaraj & Mahambare, 2022). In addition, disability status has been reported as a risk factor for SIPV, especially when paired with lower income (Kwagala & Galande, 2022). Other significant demographic risk factors include level of education, marital status, and number of children in the household. In their recent study, Larsen et al. (2021) found that a husband’s higher level of education decreased his risk for SIPV perpetration. Vyas and Heise (2016) concurred that higher education generally has a protective effect on IPV risk, though it has a more complex effect on the lower end of the education spectrum, with low education correlated with higher risk of perpetration than no formal education. Being married has also been reported as a protective factor against IPV (Spencer et al., 2022; Yakubovich et al., 2018). Conversely, studies have shown mixed results regarding the relationship between IPV exposure and the number of children in the home (Larsen et al., 2021; Spencer et al., 2022; Vyas & Heise, 2016). The current study will examine the power of these complex effects across studies, creating a clearer picture of how income level, education, and employment directly interact with SIPV in a global context. Gender Differences and IPV According to nationally representative data on prevalence rates of victimization of SIPV, women experience forms of SIPV (i.e., rape, sexual coercion) more frequently than men (Basile et al., 2022; Breiding et al., 2014). Further, extant literature reveals that women who have experienced stalking victimization and violence by non-intimate partners are more likely to experience all types of IPV by intimate partners, including SIPV (Krebs et al., 2011). Notably, 80% of men and women reported experiencing SIPV victimization for the first time before age 25 (Basile et al., 2022). Similarly, a study by Breiding et al. (2014) found 78.7% of female rape victims reported being raped before age 25. It is apparent that adolescents and emerging adults are at high risk for experiencing sexual violence in their intimate relationships, especially young girls and women (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Stark et al., 2019). Moreover, an international study on IPV highlights experiences of physical IPV and/or SIPV victimization of men and women, noting the association with sexual risk behaviors (i.e., alcohol use in context of sex, STIs, having multiple sexual partners) that may be harmful to their future partners (Pengpid & Peltzer, 2020). Due to the gender differences associated with SIPV, it is necessary to examine gender separately regarding demographic factors and their relationship with SIPV victimization and perpetration. The Present Study Understanding the factors that predict SIPV is a crucial step in preventing its acute and long-term negative effects on health. For this study, a meta-analysis was conducted of the last 25 years of available global research on SIPV. It separates SIPV from physical IPV and specifically focuses on demographic factors as predictors for SIPV exposure. Variance in SIPV exposure between different gender identities and sexual identities is highlighted, based on significant results in previous studies (Basile et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023). In addition, the study aims to examine the direction of violence (i.e., perpetration vs. victimization) across demographic factors. This meta-analysis seeks to examine demographic factors as correlates of SIPV, unearth emerging trends, and identify gaps in the literature thereby strengthening the research and clinical applicability of future SIPV research. Literature Search The meta-analysis was conducted using standard protocols for obtaining studies to be included in the meta-analysis (Card, 2012). Peer-reviewed journal articles, dissertations, and theses published between 2000-2022 were identified to be included in the study through database searches (Proquest, Proquest Dissertations and Theses, PsycInfo, ERIC, Sociological Abstracts, Social Service Abstracts). Boolean search terms were used related to violence (violen*, aggress* abus*, perpetrat*, victim*, maltreat*, domestic violen*, assault), sexual violence (sex*, harass, rape, coerc*, non-consensual, unwanted, manipulation, forced, penetrat*, misconduct, threat, revenge, sodomy, molest, genital, oral, anal), intimate relationships (partner, couple, relation*, married, dat*, spous, marital, intimate, roman&, spous*), and correlates (predict*, associate*, correlate*, marker, risk, path, factor, predict*). The searches identified a total of 20,188 studies for potential inclusion in the current meta-analysis. Included Studies Once studies were identified, they were examined for potential inclusion in the meta-analysis. The inclusion criteria was: (a) examined SIPV specifically and not merged with another type of IPV, (b) examined demographic correlates with SIPV, (c) examined samples of adults, (d) included statistics in the study that allowed for the calculation of one or more bivariate effect sizes, (e) were published between 2000-2022, and (f) were written in English. There were 20,188 studies originally identified for potential inclusion in the meta-analysis (See Figure 1 for flowchart of included studies). During the first round of screening, article titles and abstracts were reviewed by members of the research team to see if there was a possibility of inclusion in the study. If it was at all possible that studies fit the inclusion criteria, they were included in the second round of screening. A total of 16,489 studies were excluded in the first round of screening, leaving 3,699 studies for further review. A total of 531 duplicates were identified, so a total of 3,168 articles were included in the second round of screening, where full texts were examined to determine eligibility. In the second round of screening, 1,311 were excluded for not examining sexual IPV, 544 did not examine demographic factors as correlates for SIPV, 531 did not provide statistics to calculate one or more bivariate effect sizes, 325 did not examine any correlates for SIPV perpetration or victimization, 202 were qualitative papers or literature reviews, 68 examined child or adolescent populations, 38 were written in a language outside of English, and six were not published during the timeframe examined. A total of 143 studies were included in the current meta-analysis. Coding Procedures A 26-item code sheet was created by the research team in order to capture relevant information from each study included in the meta-analysis. The codes sheet collected pertinent information from each included study, such as the location of where data was collected, the sample size, the demographic makeup of the sample (e.g., gender, race, ethnicity), information on the study design (e.g., longitudinal or cross-sectional), how SIPV was defined/measured, and any statistical information to calculate one or more bivariate effect sizes for each study. Each article was cross-coded by two separate researchers in order to ensure accuracy of the data. If there were discrepancies in the data, a lead research team member would consult to determine the correct information. The coding agreement rate was 98.04% Data Analysis Data was entered and analyzed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 4.0 (Borenstein et al., 2022) using a random-effects approach to the data analyses. A random-effects approach allows for increased generalizability of the data, as it accounts for both within-study and between-study variance, assuming that effects differ between studies due to true population differences between studies (Borenstein et al., 2010; Dettori et al., 2022). Studies were included in the analysis from all countries and regions, supporting the notion that true population differences between studies are present. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 4.0 (Borenstein et al., 2022) was used to calculate aggregate effect sizes (Pearson’s r) for each demographic factor found in at least two unique studies (Cumming, 2012) to examine the relationship between those demographic factors and SIPV victimization or perpetration. Additionally, the I² statistic was also calculated for each variable to examine heterogeneity between studies. Aggregate effect sizes were calculated for samples including all gender identities, for samples including just men, and samples including just women. Next, for any significant results found in at least three studies, a classic fail-safe n was calculated to examine the potential of publication bias (Rosenthal, 1979). The possibility of publication bias can occur when insignificant findings go unpublished, and are therefore unable to be included in a meta-analysis (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). In order to determine if results are robust against possible publication bias, the classic fail-safe n provides the number of studies with insignificant findings that it would take for the results to no longer be statistically significant. If the number of studies in the analysis, multiplied by five, and plus ten, is smaller the classic fail-safe n, then results are deemed to be robust against potential publication bias (Rosenthal, 1979). Additionally, Egger’s test was calculated to examine asymmetry in the funnel plot to examine potential publication bias among variables that included at least 10 studies (Higgins et al., 2022; Sterne & Egger, 2001). If Egger’s test is significant (p < .05), it indicates that there may be small-study effects or publication bias (Sterne & Egger, 2001). A total of 143 studies were included in the analysis. There was a total sample size of 964,955 from all included studies. Approximately 45.5% of the studies were conducted in the United States (n = 65), followed by Uganda (7%, n = 10), China (5.6%, n = 8), South Africa (4.9%, n = 7), India (4.2%, n = 6), Nigeria (4.2%, n = 6), Bangladesh (2.1%, n = 3), and Iran (2.1%, n = 3). Two studies were identified that studied populations in multiple countries in Africa, Ethiopia, Malawi, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, and Turkey. There were 21 countries that were found in only one study. There were 103 studies that focused on male perpetration, 38 that examined both male and female perpetration, and 2 that focused specifically on female perpetration. There were 98 studies that focused solely on female victimization, 35 examined both male and female victimization, and 9 focused on male victimization. There were seven studies that were longitudinal, and the remaining studies (n = 136) were cross-sectional. There were 12 studies that specifically examined LGBTQ+ populations and 131 did not. Table 1 Demographic Factors as Correlates for Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration and Victimization among Samples of Men and Women   Note. k = number of effect sizes; r = Pearson’s r; CI = confidence interval; â–˛ = not robust against publication bias; boldface indicates statistical significance. Demographic Correlates for SIPV For samples that included both men and women, the strongest demographic factors associated with SIPV victimization were being bisexual (r = .25, p < .001; See Table 1), being LGBTQ+ (r = .21, p < .001), being a female (r = .19, p < .001), and having a disability (r = .19, p < .001). Having a lower income (r = .07, p = .001), and having a lower education (r = .06, p < .001) were all significantly related to SIPV victimization. Being younger (r = .04, p < .001) was significantly related to SIPV victimization, but was not robust against potential publication bias. Being married was negatively related to SIPV victimization (r = -.08, p = .027). Being a Person of Color, being Black, being unemployed, and being Hispanic were not significantly related to SIPV victimization. Being bisexual (r = .22, p = .031) and being a member of the LGBTQ+ community (r = .10, p = .007) were significantly related to SIPV perpetration. However, these were not robust against potential publication bias and should be interpreted with caution. Being a female was negatively associated with SIPV perpetration (r =- .17, p = .007), but was also not robust against potential publication bias. Being Black, a Person of Color (i.e., an aggregate of multiple racial categories), and younger age was not significantly associated with SIPV perpetration. Demographic Correlates for SIPV for Women For women, the strongest correlates for SIPV victimization were having a disability (r = .19, p < .001; see Table 2) and being bisexual (r = .19, p < .001). The next strongest correlates were being a member of the LGBTQ+ community (r = .18, p < .001), and cohabitating with a partner (r = .10, p = .013), although cohabitation was not robust against potential publication bias and should be interpreted with caution. Next, lower income (r = .08, p < .001), lower age at first marriage (r = .07, p < .001), polygamy/polyamory (r = .06, p = .001), lower education (r = .18, p < .001), and living in a rural area (r = .04, p = .004) were associated with SIPV victimization for women. Younger age (r = .04, p < .001) was associated with SIPV victimization among women, but results were not robust against possible publication bias and should be interpreted with caution. Socioeconomic status, being Black, the age difference between partners, number of children, religiosity, length of the relationship, living in an urban area, being a Person of Color, being unemployed, being Hispanic, immigrant status, being married, and living with others (and not their partner) were not significantly related to SIPV victimization. Table 2 Demographic Factors as Correlates for Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Victimization among Samples of Women only   Note. k = number of effect sizes; r = Pearson’s r; CI = confidence interval; â–˛ = not robust against publication bias; boldface indicates statistical significance. Demographic Correlates for SIPV for Men For men, lower education (r = .11, p = .004; see Table 3) was significantly related to SIPV victimization. Being unemployed (r = .09, p = .005) was associated with SIPV victimization, but was not robust against potential publication bias and should be interpreted with caution. The length of the relationship was negatively related to SIPV victimization (r = -.09, p = .027), suggesting the longer the relationship, the less likely SIPV victimization was occurring. Being Black, a Person of Color, Hispanic, having an unskilled job, being LGBTQ+, age at first marriage, being married, younger age, and lower income were not significantly related to SIPV victimization for men. For men, being married was negatively related to SIPV perpetration (r = -.19, p < .001). Being a Person of Color, Black, Hispanic, younger in age, unemployed, having a lower income, and having a lower education level were not significantly related to SIPV perpetration. Table 3 Demographic Factors as Correlates for Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration and Victimization among Samples of Men Only   Note. k = number of effect sizes; r = Pearson’s r; CI = confidence interval; â–˛ = not robust against publication bias; boldface indicates statistical significance. This meta-analysis synthesized data from 143 studies to explore associations between demographic factors and SIPV victimization and perpetration. This study examined SIPV specifically, as opposed to combined forms of IPV, adding to the current literature on the correlates for various types of IPV. The current study confirms that several risk factors for other forms of IPV are also significant risk factors for SIPV victimization, such as identifying as female, LGBTQ+, or being disabled. The meta-analysis highlighted surprising results such as an insignificant relationship between race and SIPV victimization on a global scale, which warrants further discussion. In addition, the current study highlighted the differences in the risk markers studied between genders, such that SIPV perpetration is understudied among women and SIPV victimization is rarely studied among men. Demographic Factors as Correlates of SIPV Victimization Additionally, there were several significant demographic factors significantly correlated with SIPV victimization, with the strongest being bisexual compared to heterosexual. The current meta-analysis also demonstrates that bisexual individuals are at even higher risk for SIPV victimization than LGBTQ+ folks generally, which has been found previously in research on U.S. university students (Cantor et al., 2020). Previous literature has posited that biphobia and jealousy may explain this increased risk, especially when the victim’s partner is not bisexual (Turell et al., 2018). Lack of understanding of bisexuality can also lead to stereotyping and oversexualizing bisexual people, which further highlights the increased risk of SIPV victimization in this population. Identifying as LGBTQ+ was also a significant risk marker for SIPV victimization among both men and women, which is consistent with studies of LGBTQ+ participants in college-aged samples (Spencer et al., 2024). These findings align with previous research that lesbian women, bisexual women, gay men, and bisexual men were found to have experienced SIPV at a higher rate than their heterosexual counterparts (Chen et al., 2023). While care interventions designed for this population do exist, there is little evidence of implementation, evaluation, and effectiveness. The findings from the study suggest that members of the LGBTQ+ community, and especially those who identify as bisexual, are at an increased risk for SIPV victimization and intervention and prevention efforts, as well as resources for this population are needed. For example, queer women have identified challenges in seeking resources for IPV victimization, such as the fact that their abusers have the opportunity to invade spaces that were supposed to be safe (e.g., domestic violence shelters) due to the fact that their perpetrator was also a woman (Harden et al., 2022). The next strongest factor correlated with SIPV victimization was having a disability. For samples of only women, having a disability was the strongest correlate for SIPV victimization. Previous research has found that having a disability is a strong risk marker, with some finding as much as two times the likelihood of experiencing sexual victimization compared to able-bodied persons (Mailhot Amborski et al., 2022; D. L. Smith, 2008). It has been found that this traumatic experience is not limited by gender either, with both women and men alike having an increased risk of sexual IPV if they have a disability (Basile et al., 2022). Although there is a notably higher prevalence rate of sexual IPV among victims with disabilities, there are limitations in care for the population. One study found lack of funding, lack of training, and structural limitations of service facilities as limiting factors to providing accommodating services to women with disabilities (Chang et al., 2003). Additionally, a victim’s disability may increase dependency on their abusive partner, which may further complicate or lengthen their relationship (Thomas & Weston, 2020). Previous research has examined additional variables that further increased the risk of abuse among women with disabilities, such as being unemployed and being younger in age (D. L. Smith, 2008). This suggests the importance of examining how multiple demographic factors can influence the risk of SIPV victimization. Findings from the study suggest a need for resources designed for victims of IPV to take into account individuals with disabilities and potential barriers they may face when seeking resources or help. The meta-analysis also revealed marriage as a significant protective factor for SIPV victimization among men but not among women. Moreover, being married was the only protective factor for SIPV victimization among men, which is a unique finding of this study. Further, a previous meta-analysis on physical IPV victimization has examined the relationship between marriage and physical IPV victimization among men, and the results were insignificant (Spencer, Stith, et al., 2019). Therefore, the current meta-analysis provides valuable insight into marriage as a protective factor, specifically when examining risk for SIPV victimization among men. However, this relationship was not significant among women. Some findings suggest marriage might be a protective factor against women’s victimization of SIPV, while other studies suggest the opposite, highlighting another area for further investigation (Cherlin et al., 2004; Spencer, Mendez, et al., 2019; Spencer et al., 2022; Yakubovich et al., 2018). Younger age correlated with increased risk of SIPV victimization for females in the current study. Multiple studies have examined correlates for sexual assault (SA) in college-aged populations (Cantor et al., 2020; Edwards & Sylaska, 2013; Spencer et al., 2023; Spencer et al., 2024). However, previous research has not found a significant correlation between lower age and risk of SIPV victimization within-cohort. Rather, Spencer et al. (2023) found that risk of victimization increased along with respondents’ year in school. A similar study among adolescents also found that year in school correlated with SIPV victimization risk (Meadows et al., 2022). Based on these findings, it appears that the risk of SIPV victimization increases when people enter the young adult cohort. The findings of the current study are in line with national data on SIPV, which shows that over 80% of female victims experience their first rape before age 25 (Basile et al., 2022). Considering this trend, future research on SIPV should continue to monitor and refine the factors that contribute to young adults’ risk of victimization. In the current study, polygamy and polyamory were combined due to low amounts of studies examining these separately in relation to SIPV, and was found to be significantly associated with SIPV victimization among women. Polygamy as a relationship structure is a sociocultural factor often practiced outside of the U.S., mostly in sub-Saharan African countries, and has been found to be a risk factor for women experiencing SIPV victimization (Ahinkorah, 2021; Ebrahim & Atteraya, 2021; Issahaku, 2017). Polyamory, or open relationships, are relationship structures that are practiced all around the world, and research has suggested that there may be a link between non-monogamy and SIPV victimization for women in relationships, particularly bisexual women who have a male partner (Head & Milton, 2014; Turell et al., 2018). More research ought to be done examining these relationship structures separately and how they pertain to SIPV victimization among women, attuning to sexual orientation, geographic location, and culture. Demographic Correlates for SIPV Perpetration The sole protective factor for SIPV perpetration was being a woman compared to being a man, implying that women are less likely to perpetrate sexual IPV when compared to men. These findings align with previous research that found that most female victims of SIPV reported only male perpetrators (Chen et al., 2023). For male victims, there was a more varied distribution, with the study finding male perpetrators reported by 75.3% of gay victims, 31.4% for bisexual victims, and 22.6% for heterosexual victims. The findings from this meta-analysis highlight the notion that men are more likely to perpetrate sexual IPV compared to women. For men, the only correlate for SIPV perpetration that was robust against publication bias was having a lower education. This is in line with previous research which demonstrates that men with a low education were at higher risk for IPV perpetration than those with high education (Vyas & Heise, 2016). However, the literature points out that the relationship between male and female partners’ levels of education may be more significant. Previous studies have found that men with lower education than their female spouses were at higher risk for perpetration (Dildar, 2021) and that women with a lower level of education were at decreased risk of IPV victimization (Larsen et al., 2021). The current analysis shows a significant, though weak positive correlation between women’s low education and SIPV victimization. The complexity of these findings highlights the need to study the interrelationship between male and female partners’ level of education in order to confirm or rule out what Dildar (2021) calls a “backlash effect” when studying men’s risk of IPV perpetration. The study also revealed a significant relationship between unemployment and SIPV perpetration among men only, in line with previous literature (Bhalotra et al., 2021; Bourey et al., 2022; Dhanaraj & Mahambare, 2022). Previous literature suggests that this often is observed in heterosexual relationships where the woman is employed and the man is not, increasing risk for male perpetration which may be due, in part, to gender norms (Bhalotra et al., 2021; Bourey et al., 2022; Dhanaraj & Mahambare, 2022; Tur-Prats, 2021). Male perpetration of SIPV might make sense in the face of unemployment in a household where traditional gender roles are adhered to and/or the man is the primary breadwinner due to a felt sense of threat toward their role (Alonso-Borrego & Carrasco, 2017). Nonetheless, our analysis indicated this relationship remains trivial and is not robust against publication bias. Therefore, further research is needed to provide more accurate knowledge of this potential relationship. It is important to note that unemployment was not examined as a risk factor for women’s perpetration of SIPV. This may be due to traditional gender roles held in many countries/provinces where it is more common for men to be the breadwinner compared to women and men contributing to household income (Tur-Prats, 2021). Regardless, this relationship may be important to examine since there are relationships where women are the main contributors to household income; thus, losing their job may cause threat to their role and potentially their relationship. Gaps in the Current Literature This meta-analysis also highlights large gaps in the literature regarding demographic factors associated with women’s perpetration of SIPV and men’s victimization of SIPV. Namely, younger age and lower income were examined as correlates of SIPV victimization among men the most of any single factor, which only included six studies. Along with this, there were no demographic factors examined as correlates for women’s perpetration of SIPV found in at least two unique studies. For example, being a member of the LGBTQ+ community and sexual IPV perpetration was examined among men, but not for women. This may be due to stereotypes about the absence of violence for women in the LGTBQ+ community in same-sex relationships that has been coined as “lesbian utopia,” meaning women in relationships with women don’t experience violence. Literature suggests that this bias or notion of utopia came from “lesbian feminism” (i.e., woman-to-woman relationships are equal, non-exploitative, and non-violent; Barnes, 2007, 2011). Therefore, violence in these relationships is a contradiction to this utopia and lesbian feminism, yet it still occurs (Barnes, 2007, 2011). Violence perpetration is also common among women in relationships, whether same-sex or heterosexual (Leemis et al., 2022; Sutter et al., 2018). Moreover, violence in woman-to-woman relationships, especially perpetration, has been heavily understudied due to these stereotypes and the desire to break free from traditional patriarchal norms; thus, further research on sexual violence in these relationships is necessary to inform prevention and practice in woman-to-woman relationships. Overall, our results highlight significant gaps in research regarding the link between demographic factors and sexual IPV perpetration for women and sexual IPV victimization for men. Among all participants combined, as well as men and women separately, our meta-analysis revealed a lack of studies examining the relationship between SIPV perpetration and victimization and race, highlighting a need for further investigation. Further, race was not found to be a significant risk marker of SIPV victimization when comparing POC, Black, and Hispanic participants to White participants. This might be due to the lower number of studies examining these relationships, as previous studies have noted that American women who identify as multiracial (i.e., American Indian/Alaska Native, non-Hispanic Black) are at a significantly increased risk for sexual violence victimization compared to White women (Basile et al., 2022; Breiding et al., 2014). Therefore, future research ought to investigate this further to provide a broader understanding of this potential relationship. It is also important to note that studies included in the analysis were from countries around the world, and examining the relationship between race and ethnicity and SIPV may differ depending on the country or location the study was conducted. Implications Previous literature has found that SIPV exposure has a damaging effect on public health, including physical disease and injury, as well as comorbid mental health issues, such as major depression and PTSD (Basile et al., 2022; Zinzow et al., 2012). SIPV victims are also at higher risk of other forms of IPV exposure, which vary in terms of their cost to health systems across the globe (Krebs et al., 2011; Walby & Olive 2014). The findings in this study demonstrate demographic information that may allow health service agencies, governments, and other professionals to identify and screen for SIPV at an earlier stage of exposure, preventing further harm in the process. Policy changes that increase early interventions for at risk populations may serve to curb health costs and concerns related to SIPV exposure. Limitations & Future Research Several limitations were present in the current analysis. For example, no studies examined the risk of SIPV perpetration among women only. By contrast, comparatively few studies examined the risk of SIPV victimization among men, which is a well-established gap in the literature. Future research should work to fill these gaps by considering correlates of SIPV for female perpetrators and male victims. Another considerable limitation is that many variables included in the meta-analysis were only examined in two or three studies. Meta-analyses with less than five included studies may lack power (Jackson & Turner, 2017). Although it is important to highlight the variables examined in few studies, future research on these variables is warranted in order to draw more generalizable conclusions. Additionally, multiple factors in the current study were not robust against publication bias. More studies examining lesser-studied variables are needed to combat this issue in future research on demographic correlates for SIPV. As mentioned above, the meta-analysis relied heavily on research conducted in the United States. This could have an impact on the generalizability of findings related to marriage, a state-sanctioned relationship that may have varying norms of appropriate behavior across cultures. Income level, which is frequently related to in-country wealth differences, could also be affected by this geographic weighting. Furthermore, findings about risk of SIPV in LGBTQ+ populations (e.g., Harden et al., 2022; Turell, 2000) were reliant on data from Western countries. Further research is needed to confirm if these risk factors hold in different cultures and nations across the globe. Another limitation of this meta-analysis is that some of the factors included may be confounded by complex relationships between factors within a couple dyad. Specifically, previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between IPV exposure and a difference in unemployment status between male and female participants (Bhalotra et al., 2021; Bourey et al., 2022; Dhanaraj & Mahambare, 2022). Other research has found a correlation between a difference in education level within a couple and increased IPV exposure (Vyas & Heise, 2016). The current meta-analysis was unable to capture this complexity, highlighting the need for future research to keep these established relationships in mind when working to understand the risk factors for SIPV. As mentioned above, the current study found that identifying as LGBTQ+ or bisexual correlated with increased risk of SIPV victimization, particularly in women, and SIPV perpetration in both men and women. In the current meta-analysis, transgender and non-binary (TNB) individuals were only identified in one study (Turell, 2000). Within that study, only 7 out of 499 participants identified as transgender and no participants endorsed a non-binary identity. This highlights a significant gap in the literature. Survey measures often do not provide “transgender” as an option and non-binary individuals tend to endorse “transgender” when they are not able to endorse a more nuanced identity. This, in effect, makes TNB people largely invisible in the extant literature. An additional difficulty in researching the TNB population is that individuals often endorse a myriad of labels to describe their gender (Richards et al., 2016). Though it may be difficult to gain momentum due to this challenge with gender labels, it behooves the research community to pay closer attention to how TNB participants are included or excluded in future research on SIPV. One noted strength of this study is its focus on SIPV as a distinct form of IPV. This distinction illuminates trends in the literature that have not previously been captured on an international scale. SIPV is complex, however, especially when recorded by self-report measures. While the sources in this analysis addressed varied forms of SIPV, the current study combined these definitions to consolidate the effect of demographic factors on combined SIPV risk. Previous research has hypothesized that men endorse SIPV victimization more frequently when measures refer to sexual coercion rather than forced sex or rape, likely due to social desirability bias (Scott-Storey, 2022). Gender norms clearly have an impact on the current understanding of sexual violence victimization. Future research is needed to further distinguish between different types of SIPV, especially in international samples. Conclusion The present study demonstrates that several demographic factors increase the risk of SIPV perpetration and victimization. This represents an important shift in the research on SIPV as SIPV and physical IPV have previously been conflated in global research on IPV. This study also highlights a gendered research gap between risks for SIPV perpetration and victimization. Male participants are often studied for SIPV perpetration and rarely for victimization while the inverse is true for female populations. In addition, a significant gap was identified regarding transgender and non-binary (TNB) people’s experiences of SIPV. Race and ethnicity were also understudied and confounded by the cultural contexts of international studies. Future research should address these concerns to strengthen the findings on risk factors for SIPV across the globe. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Zehr, P. A., Spencer, C. M., Moore, M., Siegmann, A. (2025). Associations between demographic factors and sexual intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization: A meta-analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 137-149. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a11 References References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the metaanalyses |

Cite this article as: Zehr, P. A., Spencer, C. M., Moore, M., and Siegmann, A. (2025). Associations between Demographic Factors and Sexual Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration and Victimization: A Meta-analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 137 - 149. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a11

Correspondence: pazehr@ksu.edu (P. A. Zehr).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS