A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Interventions for Individuals Who Have Committed Online Sexual Crimes Involving Children

Cláudia Gouveia1, Teresa Silva1, Olga Cunha1, Michael C. Seto2, Sacha Maimone2, & Sónia Caridade1

1Psychology Research Center (CIPSI), School of Psychology, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal; 2Institute of Mental Health Research, Royal Ottawa Health Care Group, Brockville, Ontario, Canada

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a16

Received 19 February 2025, Accepted 14 August 2025

Abstract

Objective: Online sexual crimes involving children have increased significantly with greater public access to the internet, underscoring the pressing need for effective intervention programs. While previous reviews attest to the effectiveness of psychological interventions for people who commit sexual offenses, none have specifically addressed those who commit sex crimes involving children using the internet. This systematic review aims to evaluate the effectiveness of psychological intervention programs targeting these crimes, identifying the most effective approaches in behavioral change. Method: The research was conducted across five databases (Scopus, B-on, APA PsycNet, PubMed, and Sage Journals), including studies evaluating the effectiveness of any psychological intervention in adults who have committed sexual crimes involving children through the internet, resulting in nine relevant studies. Most studies employed pre-post designs assessing psychological factors linked to reoffending, emphasizing integrated approaches including cognitive-behavioral therapy, life satisfaction promotion, multimodal treatments, and monitoring. Results: Findings indicated that, in most cases, there were psychological improvements related to criminal behavior, along with a reduction in the frequency and severity of offenses. Methodological limitations were common, such as reliance on pre-post designs, self-reported data, and absence of control groups or conditions. Conclusions: This review underscores the necessity for further research to gauge intervention program effectiveness in this population, stressing larger sample sizes, control group inclusion, and follow-up periods. Despite limitations, the review offers practical insights for clinicians, identifying key treatment components and risk assessment tools useful for personalized intervention planning and clinical decision-making in this population.

Keywords

Online sexual crimes, Psychological interventions, Effectiveness, Children, Systematic reviewCite this article as: Gouveia, C., Silva, T., Cunha, O., Seto, M. C., Maimone, S., & Caridade, S. (2026). A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Interventions for Individuals Who Have Committed Online Sexual Crimes Involving Children. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260808. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a16

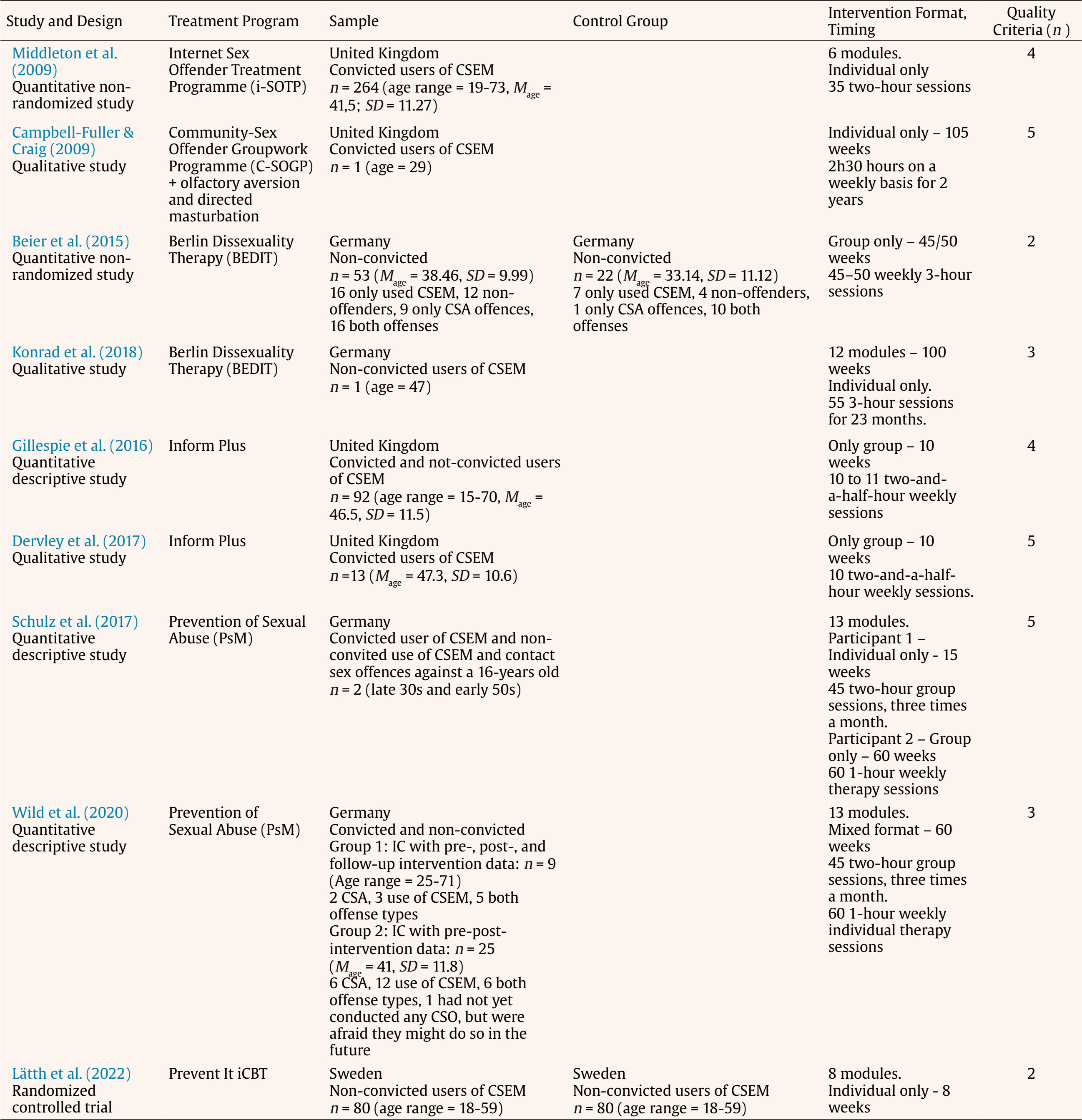

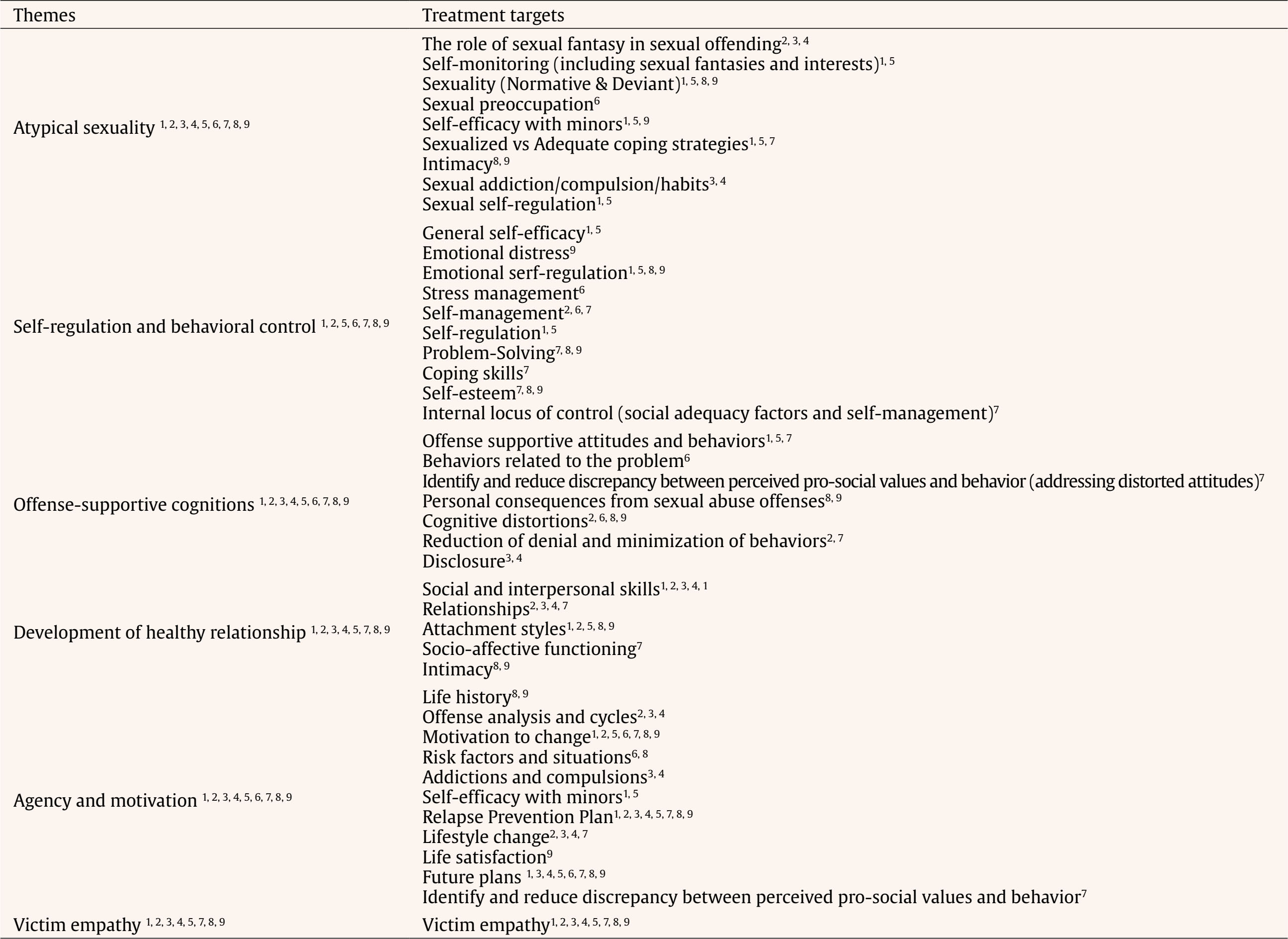

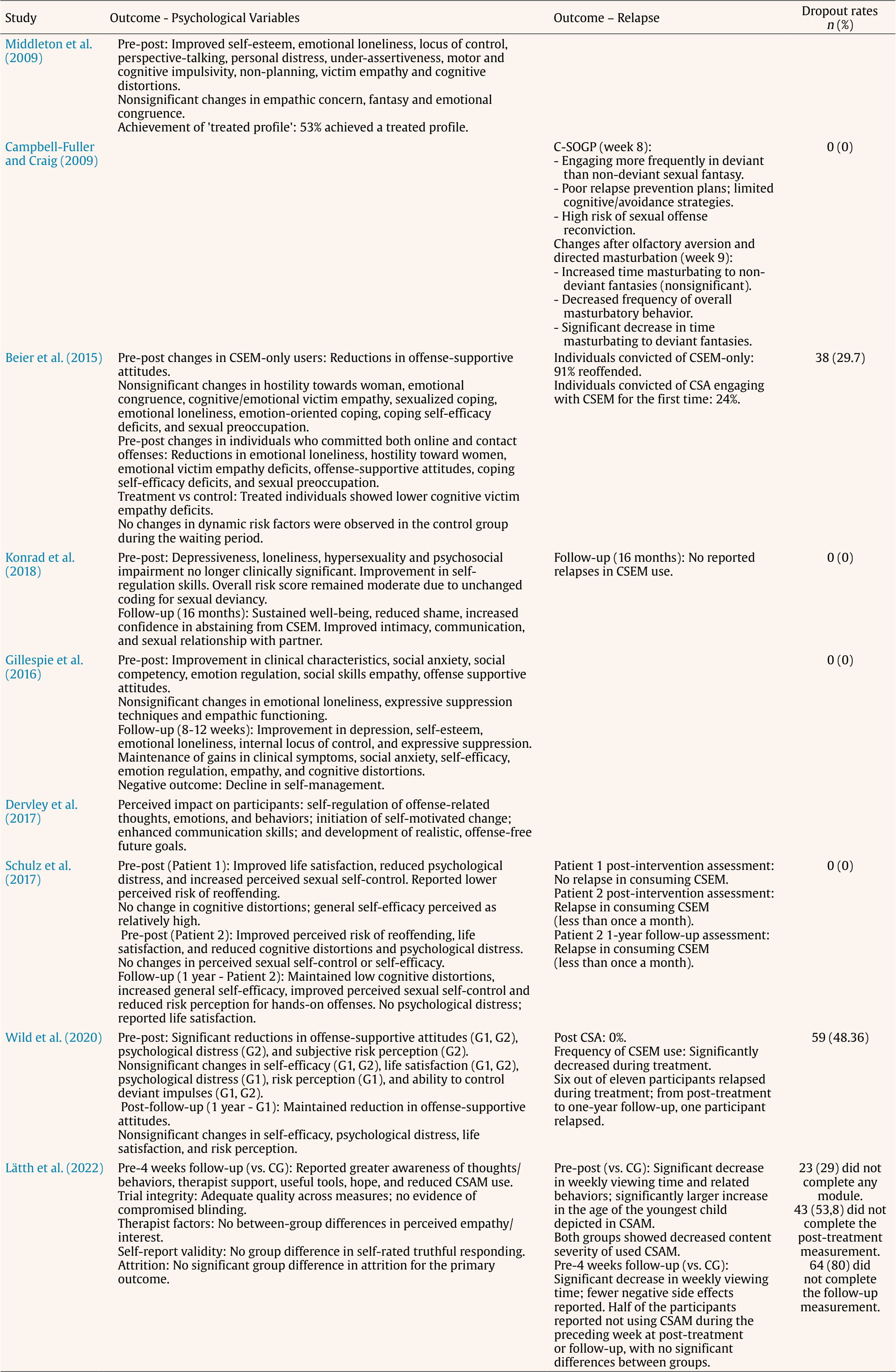

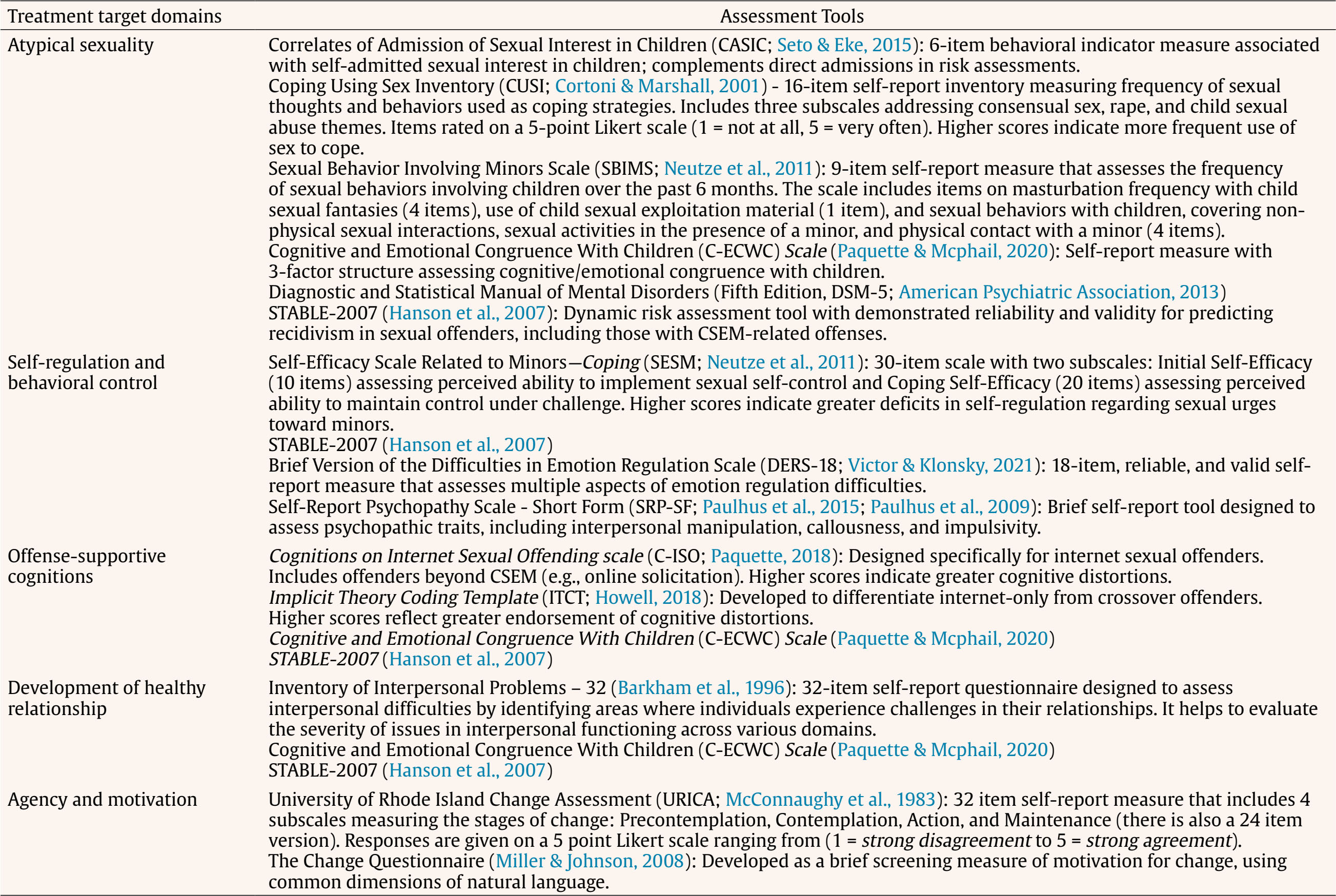

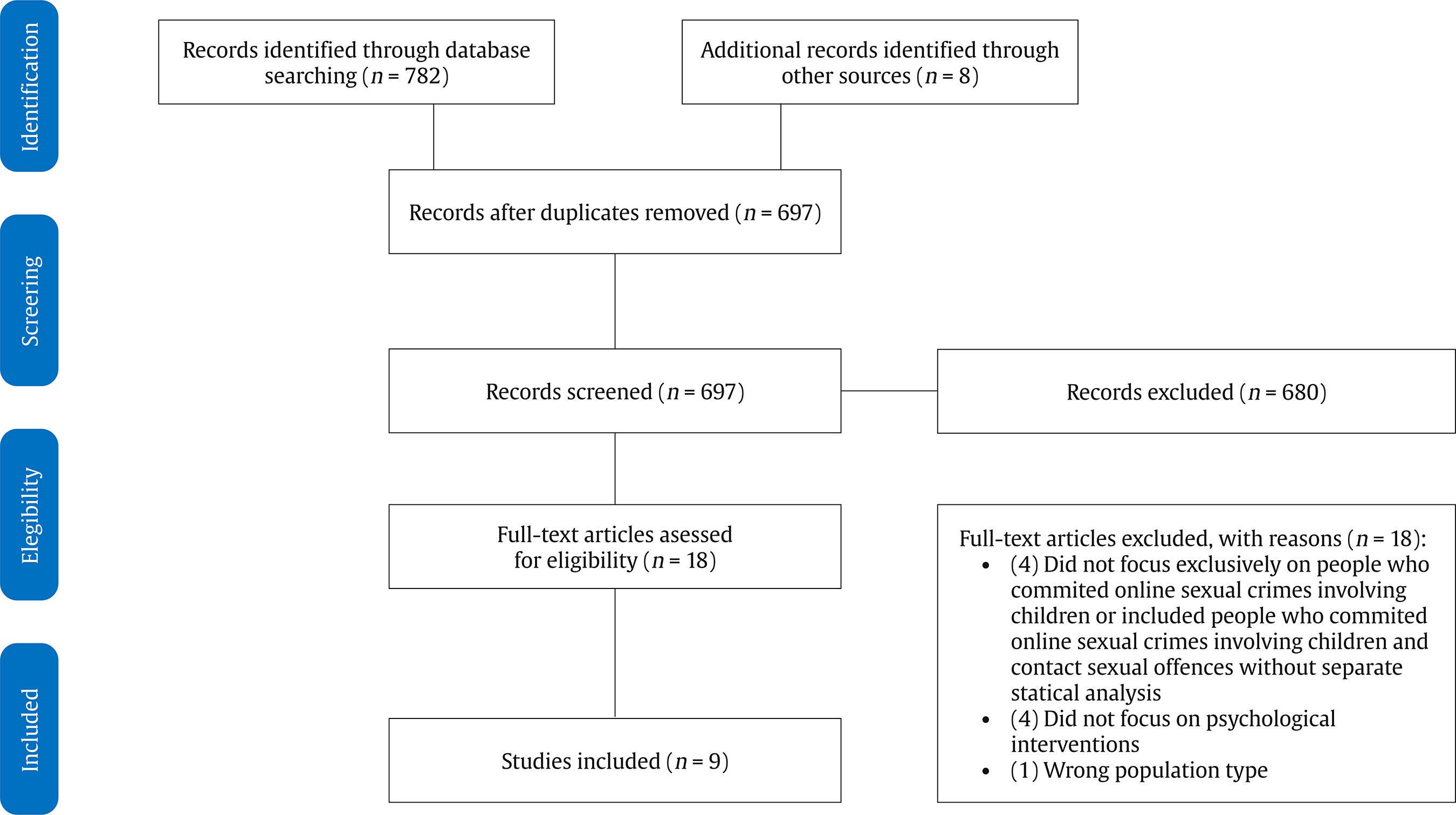

Correspondence: id11238@uminho.pt (C. Gouveia).The proliferation of internet technologies has facilitated people's access to information and communication, but it has also made it easier for individuals to access potential victims. Due to its accessibility, affordability, and anonymity (Cooper, 1998), the internet provides a unique environment where online sexual offenses can be committed (Seto, 2013; Wortley & Smallbone, 2006). The sexual exploitation of children through the internet includes online sexual solicitation as well as the possession, creation, and distribution of child sexual exploitation materials (CSEM, legally referred to as child pornography; Babchishin et al., 2018; Gottfried et al., 2020; Paquette & Cortoni, 2020). The term online child sexual solicitation is used to describe sexual communications between an adult and a minor through online apps or platforms (Babchishin et al., 2018; Gottfried et al., 2020; Paquette & Cortoni, 2020). According to data from INTERPOL's International Child Sexual Exploitation database (n.d.), more than 4.9 million CSEM and over 43,300 victims and 18,300 perpetrators had been identified worldwide. In 2024, reports of suspected CSEM declined compared to the previous year, but still totaled a substantial 20.5 million reports, following a peak of 36.2 million reports submitted in 2023 (CyberTipline Report, 2024). The substantial rise in convictions for online sexual crimes involving children has led to a growing body of research focusing on individuals who commit these kinds of offenses (Babchishin et al., 2015; Seto et al., 2011). One of the most extensively researched questions is whether this population is different at the level of assessment, risk factors, and intervention needs, compared to other sexual offenders. The literature has highlighted significant differences among groups of individuals who have committed sexual offenses involving children, particularly those who commit exclusively online offenses compared to those who commit contact sexual offenses (Babchishin et al., 2015; Henshaw et al., 2017; Seto et al., 2023). Exclusively online individuals tend to exhibit atypical sexual interests, especially pedophilic sexual interests, but display lower levels of antisocial traits or behaviors such as offense-supportive cognitions, aggression, or substance use (Babchishin et al., 2015). Overall, individuals who have committed online-only sexual crimes involving children show greater difficulties in interpersonal and romantic relationships, more socio-emotional deficits, emotional avoidance, and a tendency to use sexualized coping strategies. At the same time, they also tend to demonstrate higher victim empathy, greater self-control, and better academic and occupational functioning (Aslan et al., 2014; Babchishin et al., 2015; Elliott et al., 2013). In contrast, individuals who engage in both online and contact sexual offenses involving children display a higher-risk profile, marked by greater criminal history, greater sexual dysregulation, higher levels of antisocial traits, and reduced empathy (Babchishin et al., 2015; Henshaw et al., 2017; Paquette & Brouillette-Alarie, 2024). Among the factors contributing to this elevated risk, emotional congruence with children (i.e., a strong emotional connection or identification with children), has emerged as a relevant risk factor across offender subgroups. It not only increases the likelihood of contact and online sexual recidivism but may also facilitate the transition from online to contact offending (Paquette & Brouillette-Alarie, 2024). These findings underscore the heterogeneity of individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children, emphasizing the need for differentiated, multidimensional risk assessments and tailored intervention strategies based on offender profiles and offense types. Despite previous reviews and meta-analyses suggesting sexual recidivism rates are lower for perpetrators who received specialized psychological intervention (Hanson et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2016; Lösel & Schmucker, 2005; Mpofu et al., 2018; Sousa et al., 2022; Tyler et al., 2021), none have specifically focused on individuals who offend online. The only scoping review and gap analysis for this population was conducted by Perkins et al. (2018). However, this review evaluated interventions qualitatively through an online survey of experts and clinicians. Also, very few of the developed interventions were evaluated using clinical trials, most involved pre-post comparisons, or matched comparisons of some kind. There have been some published evaluations of intervention programs that vary considerably in their design, treatment approach, and target populations. For example, a former randomized controlled trial (RCT) of the Prevent It program – an online cognitive-behavioral therapy-informed intervention – found a significant reduction in use of CSEM among participants recruited through the Darknet (Lätth et al., 2022), while an evaluation of i-SOTP, a manualized, group-based intervention designed for individuals convicted of internet-related sexual offenses showed significant pre-post reductions on self-report measures of treatment targets among convicted individuals on probation in the United Kingdom (Middleton et al., 2009). Further details on these interventions are discussed later in the review. The evaluation of an intervention’s effectiveness is based on both the rigor of the methodological design employed and on the appropriateness and specificity of the outcome measures used to assess program impact. The Collaborative Outcome Data Committee (Beech et al., 2007a; Beech et al., 2007b) establishes that the evaluation of the effectiveness of sexual offending treatment should primarily consider recidivism rates, but it is also important to understand what changes lead individuals to desist from committing sexual crimes. Additionally, it is relevant to know how a program works in the short term, which may involve measuring changes in individuals over time on empirically identified criminogenic needs (Nunes et al., 2011). Ideally, treatment effectiveness is assessed by comparing a specific intervention with an alternative intervention or with a no-treatment condition. Many critics have pointed out that RCTs are the gold standard for evaluating program effectiveness, because they can minimize selection biases and other confounding variables through the random assignment of participants to intervention and control groups (Rice & Grant, 2013; Seto, 2008). This approach ensures that any observed pre-post changes can be largely attributed to the intervention itself rather than to external factors such as regression to the mean or natural maturation (Rice & Grant, 2013; Seto et al., 2008). However, most forensic interventions face additional challenges that hinder rigorous evaluation, such as limited follow-up periods, lack of comparable control groups and institutional constraints like session scheduling conflicts, inmate infractions, and the risk of contamination between treatment and control groups in communal prison settings. As a result, the majority of existing programs have not undergone robust empirical evaluation using methodologically sound designs (Lennox et al., 2022; Marshall & Marshall, 2007). Systematic reviews have concluded that sexual offending treatment can reduce sexual recidivism. Schmucker and Lösel (2015) identified 29 studies comparing a total of 4,939 treated and 5,448 untreated individuals who have sexually offended and found a significant effect of sexual offending treatment, with a relative reduction of 26.3% in sexual recidivism. Surprisingly, they also found that study quality did not moderate effect sizes, but there were few RCTs. Gannon et al. (2019) conducted a more recent meta-analysis, concluding that cognitive-behavioral therapy-informed treatment that focusses on sexual arousal and includes psychologists is more effective at reducing sexual reoffending. The aim of the present systematic review is to identify and analyze the quality of empirical evaluations of programs for individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children. This systematic review builds upon prior literature examining treatments for online sexual offending by (1) providing a more detailed description of treatment procedures, (2) examining how treatment needs were measured, (3) analyzing the effectiveness of treatment programs in the short term (pre-post measures) and/or long term (recidivism rates), and (4) giving evidence-informed recommendations for practice. Search Strategy The present systematic review adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009; Page et al., 2021) and was formally registered on the Open Science Framework [blinded for review]. No date restrictions were applied; the search was conducted up to October 2024 by two independent psychology doctorate students. The following search was used to ascertain the pertinent articles: (“treatment” OR “intervent*” OR “therapy” OR “counselling”) AND (“internet child sex offen*” OR “online child sex offen*” OR “online pedophi*” OR “internet offen*” OR “online offen*” OR “online child molest*”) AND (“child pornogra*” OR “child sexual exploit*” OR “internet child sexual abuse” OR “internet child grooming” OR “you* online sex offend*”) AND (“effectiveness” OR “efficacy” OR “outcomes” OR “impact”). The search was conducted using the following databases: B-on, SCOPUS, APA (PsycNet), and PubMed. Reference lists of included articles, as well as formerly conducted systematic reviews and meta-analyses, were checked for additional relevant studies. Also, authors were contacted for any missing information and to inquire about any relevant unpublished data. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria The PICOS framework guided the definition of inclusion criteria: Participants (P), Interventions (I), Comparisons (C), Outcomes (O), and Study Designs (S) (Thomas et al., 2021). Inclusion criteria comprised studies involving adults (both men and women) aged 18 or older, who have committed online sexual crimes involving children (P), subjected to a psychological intervention (I), with or without a comparative group (C). The primary outcome was the effectiveness of psychological intervention, assessed through clinical changes and/or recidivism rates (O). All types of study designs were considered within this review (S). Exclusion criteria were: (a) literature reviews, (b) reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, and (c) studies not written in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. Literature Selection Process and Data Extraction Studies identified through the literature search were imported into Rayyan software for duplicate removal and screening of titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Two raters independently assessed article titles and abstracts, determining eligibility for full-text analysis. Any discrepancies between the two raters were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer available to intervene if needed. Articles meeting the inclusion criteria underwent comprehensive review by two independent raters to reach a final decision. A codebook was developed to extract data from all included articles, encompassing various aspects such as reference details (e.g., authors, year); samples’ characteristics (e.g., location, size, age); design characteristics (e.g., design type, length of follow-up); intervention’s characteristics (e.g., setting, modality, number of sessions or hours, treatment targets, complementary intervention); measurement’s characteristics (e.g., assessment measures, assessment of recidivism); and intervention’s results (e.g., dropout/completion rate; effectiveness). Quality Assessment The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Hong et al., 2018) was used to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. The MMAT is a critical appraisal instrument designed to assess the methodological quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies included in systematic reviews. It comprises five core criteria for each of the five study design categories: qualitative research, randomized controlled trials, non-randomized studies, quantitative descriptive studies, and mixed methods. The 2018 version was refined through a literature review, content validity studies, and expert consensus, resulting in an efficient, flexible, and reliable tool for evaluating study quality (Hong et al., 2018). It comprises two screening questions (e.g., “Are there clear research questions?” and “Do the collected data address the research questions?”), and five items designed to assess methodological quality, tailored to the specific study design. Each item is categorized as “yes”, “no”, or “don’t know”. The main results are displayed in Tables 1 (study design and characteristics of the sample), 2 (themes and treatment targets in systematic review studies), and 3 (summary of therapeutic procedures and outcomes). A total of 782 articles and book chapters were obtained from both primary and supplementary research. Following duplicate removal, 697 titles and abstracts were subjected to relevance screening. The eligibility of 18 studies was assessed by reviewing their full texts in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Ultimately, nine studies met all eligibility requirements for inclusion in the analysis. Due to the significant differences among the programs, varied outcomes, and inconsistent reporting of effect sizes, a quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Therefore, this review remains descriptive in nature, focusing on summarizing and synthesizing the findings qualitatively. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process flow, detailing the reasons for exclusion. Table 1 Study Design and Characteristics of the Sample   Note. CSEM = Child sexual exploitation material; CSA = Child sexual abuse. Table 2 Themes and Treatment Targets in Systematic Review Studies   Note. 1Beier et al., 2015; 2Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; 3Dervley et al., 2017; 4Gillespie et al., 2016; 5Konrad et al., 2018; 6Lätth et al., 2022; 7Middleton et al., 2009; 8Schulz et al., 2017; 9Wild et al., 2020. The treatment targets and treatment outcomes are described using the terminology employed by the original authors in each study. Although some terms may appear conceptually similar, they have been retained as reported to preserve the authors' intended meanings and avoid misinterpretation. Table 3 Summary of Therapeutic Procedures and Outcomes   Note. CSEM = child sexual exploitation material; CSA = child sexual abuse; G1 = group 1; G2 = group 2; CG = control group. Quality Assessment Among the included studies, three demonstrated all criteria of excellence, two met four out of five criteria, two met three criteria, and two studies demonstrated only two criteria (see Table 1). Each study was assessed based on specific criteria, such as the adequacy of the design, sample representativeness, and data collection quality. The ‘excellence’ ratings were assigned based on the number of criteria met by each study. For example, the qualitative study by Dervley et al. (2017) received an ‘excellence’ rating for meeting all five MMAT criteria. The chosen qualitative method was well aligned with the study’s objective of exploring experiential accounts of completing the Inform Plus program, particularly regarding perceived changes in participants’ ability to manage thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to internet offending. The data collection process was considered adequate, as it included audio-recorded interviews with program participants, professionals, partners, and parents, thereby ensuring a rich and diverse set of perspectives. The analysis was described in detail and followed a rigorous thematic approach, using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidelines for inductive thematic analysis. This allowed themes to emerge from the data itself rather than being constrained by pre-established theoretical categories. The interpretation of findings was well grounded in the data, with illustrative quotations provided to support each theme. Moreover, there was strong coherence across data sources, collection methods, analytical procedures, and interpretation, enhancing the study’s transparency, consistency, and credibility. In contrast, the quantitative study by Lätth et al. (2022), involving the randomized controlled trial evaluation of Prevent It, received a lower quality rating based on several methodological limitations identified through the MMAT criteria. First, the study presented a substantial proportion of missing outcome data, with dropout rates in the intervention group reaching 29% during the treatment, 53.75% at post-treatment, and 80% at the one-month follow-up (well above the generally accepted thresholds of 5% to 20% indicated in the MMAT guidelines). Second, the study lacked blinded outcome assessment, as acknowledged by the authors themselves, who noted that it was not feasible to blind psychotherapists or research team members involved in data collection. Finally, the study also raised concerns regarding adherence to the intervention protocol, as defined by the MMAT as imperfect compliance, cessation of intervention, crossovers to the comparator intervention, and switches to another active intervention. Given the high dropout rate observed, it is unclear whether participants meaningfully engaged with the intervention as intended, thereby limiting the validity of conclusions about its effectiveness. Despite these findings, RCTs remain the gold standard for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions (Rice & Grant, 2013; Seto, 2008). The lower quality rating attributed to this article does not undermine the methodological rigor of the RCT design itself, nor does it suggest that this method is inferior to other study designs with higher quality scores. Rather, it indicates that, according to the MMAT criteria and the expectations established in the literature for this specific design, certain methodological elements commonly required in RCTs were not adequately addressed in this study. Study Characteristics Sample The sample size of the studies ranged from 1 to 264. Although gender or sex was not specified as an inclusion criterion in our search strategy, nearly all studies included only male participants (k = 8; Beier et al., 2015; Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016; Konrad et al., 2018; Middleton et al., 2009; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). The only exception was the study by Lätth et al. (2022), which reported participants’ gender identity rather than biological sex: of the 160 individuals, 157 identified as male, two as non-binary, and one did not report their gender (see Table 1). All studies focused on samples consisting of individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children. This included convicted individuals (k = 3), non-convicted individuals (k = 3), and individuals both with and without convictions (k = 3). Regarding the index offenses, the majority of studies (6 out of 9 studies or 66.7%) included cases solely involving the use of CSEM, while the remaining studies included perpetrators of both child sexual abuse and the use of CSEM. All studies were conducted in Europe (4 UK, 4 Germany, 1 Sweden), and no evaluations of program efficacy or effectiveness were identified from non-European contexts. Several study designs were identified, including one randomized controlled trial (k = 1, 11.1%), three quantitative descriptive studies (k = 2, 22.2%), two quantitative non-randomized controlled trials (k = 3, 33.3%), and three qualitative studies (k = 3, 33.3%). Treatment Approaches Among the included papers, two studies implemented a psychoeducational component plus the Good Lives Model (GLM) plus Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) approach (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016). Two studies employed cognitive-behavioral therapy based on the Sex Offender Treatment Program (SOTP), Behandlungsprogrammfür Sexualstraftäter (BPS), Rockwood Program, good-lives-model, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR), a stress management manual, cognitive reframing methods according to Wilken, and specific features in the therapy of Child Pornography Offenders (CPOs) according to Quayle and Erooga (Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). In two studies the interventions were based on the Berlin Dissexuality Therapy (BEDIT) treatment program, each employing different therapeutic approaches. One study used a combination of the good lives model, risk-need-responsivity, cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches in addition to pharmacological intervention (Konrad et al., 2018), while another implemented a treatment that included cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychopharmacology, relapse prevention, self-regulation, and good lives model (Beier et al., 2015). One study applied an Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy plus Mindfulness (Lätth et al., 2022). One study focused on the Fisher and Beech Model of Change plus Quayle and Taylor Model of Problematic Internet Use combined with good lives model (Middleton et al., 2009), and one study employed cognitive-behavioral therapy in combination with behavior stimuli, namely, olfactory aversion and directed masturbation (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009). Three studies included interventions delivered in group format (Beier et al., 2015; Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016), four studies delivered interventions in an individual format (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Konrad et al., 2018; Lätth et al., 2022; Middleton et al., 2009), and one study utilized a combination of individual and group intervention (Wild et al., 2020). One study (Schulz et al., 2017) presented the intervention to two distinct individuals, with one receiving individual intervention only, while the other received only group intervention. The criteria for describing the duration of the intervention program varied among studies: those focusing on the number of sessions indicated that sessions ranged from 10 (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016) to 60 sessions (Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). Studies specifying the duration in time revealed variations from eight weeks (Lätth et al., 2022) to two years (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009). Three studies used only clinical change as an outcome (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016; Middleton et al., 2009), while one study only focused on recidivism (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009). Additionally, five studies employed both clinical change and recidivism as outcomes (Beier et al., 2015; Konrad et al., 2018; Lätth et al., 2022; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). The follow-up periods ranged from eight weeks to sixteen months. Four studies did not include follow-up. Moreover, the non-completion rates varied between 0% (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Gillespie et al., 2016; Konrad et al., 2018; Schulz et al., 2017) and 48% (Wild et al., 2020). One study did not report the completion rates (Dervley et al., 2017). Treatment Targets Recent research on interventions for individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children emphasizes the importance of addressing multiple risk domains and psychosocial factors (Seto et al., 2023). Seto et al. (2023) identified multiple dynamic risk factors for sexual offending, organizing them into four domains: atypical sexuality (which includes sexual preoccupation and paraphilic sexual interests); self-regulation problems (including impulsivity, lifestyle instability, emotional regulation deficits, and problem-solving deficits); antisocial cognitions (including offense-supportive attitudes and beliefs, hostile masculinity, and non-compliance with interventions); and relationship problems (including capacity for adult intimacy, emotional congruence with children, and negative social influences). The treatment targets specific to each study are organized chronologically by intervention programs to see the evolution of practices over time and highlight potential similarities, differences, and changes observed across the same program. The Internet Sex Offender Treatment Programme (i-SOTP) presented by Middleton et al. (2009) emphasized several treatment objectives. These included enhancing motivation for treatment, reducing denial, identifying and bridging the gap between perceived pro-social values and actual behavior, challenging offense-supportive attitudes and behaviors, fostering victim empathy, decreasing the use of sex as a coping mechanism and emotional avoidance, and replacing these with effective problem-solving strategies. Additionally, the program aimed to develop appropriate relationships, intimacy, and coping skills, enhance self-esteem and internal locus of control, and formulate realistic relapse prevention strategies and new pro-social lifestyle goals. The intervention facilitated by Campbell-Fuller and Craig (2009) involved the use of olfactory aversion and directed masturbation techniques with a patient who had previously completed the Community-Sex Offender Groupwork Programme (C-SOGP); the behavioral conditioning techniques were introduced as a follow-up to the initial group-based intervention. Both interventions collectively addressed motivation to change, reduction of denial and minimization, cycles and cognitive distortions, exploring relationships and attachment styles, enhancing self-management and interpersonal skills, understanding the role of fantasy in offending, fostering victim empathy, implementing relapse prevention strategies, and promoting lifestyle changes. The Berlin Dissexuality Therapy (BEDIT; Beier et al., 2015; Konrad et al., 2018) targeted motivation for change, self-efficacy and behavior control (including sexual fantasies and interests), differentiation between sexualized and appropriate coping strategies, emotional and sexual self-regulation, social functionality, attachment and sexuality, offense-supportive attitudes and behaviors, fostering empathy towards children affected by child sexual abuse and exploitation, and developing relapse prevention strategies and objectives. The Inform Plus intervention (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016) addressed various treatment targets including offense analysis and cycles, the fantasy in offending, fantasy patterns on sexual offending, fantasy management techniques, addiction/compulsion/habits, collecting behaviors, victim empathy, the legal system, disclosure, social skills, relationship dynamics, achieving change, relapse prevention, lifestyle changes, and endings. The Prevention of Sexual Abuse (PsM) program was evaluated across two separate studies (Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020), and focused on addressing factors such as motivation for change, life history, risk factors, empathy with victims, cognitive distortions, self-esteem, personal consequences from sexual abuse offenses, intimacy, attachment styles, emotional regulation, problem-solving skills, sexuality, developing a relapse prevention plan, and future planning. Additionally, the Prevent It iCBT program (Lätth et al., 2022) aimed to target variables such as sexual preoccupation, behaviors related to the problem, high-risk situations, motivation, goal setting and stress management skills, and distorted cognitions about child sexual offenses. To facilitate the analysis of the treatment targets identified in the reviewed studies, these targets were organized into evidence-based thematic categories. This approach aimed to assess the extent to which existing intervention programs address empirically supported dynamic risk factors for sexual offending, as outlined by Seto et al. (2023). Thus, we have organized the identified treatment targets into six domains that are consistent with those outlined by Seto et al. (2023): atypical sexuality (i.e., sexual preoccupation and pedophilic or hebephilic interests, which are major risk factors for both online and offline sexual offending; Babchishin et al., 2015; Beier et al., 2015; Seto et al., 2023); self-regulation and behavioral control (i.e., improving self-control and coping strategies is a core treatment goal, as deficits in these areas are linked to ongoing offending; Beier et al., 2015, Garrington et al., 2023); offense-supportive cognitions (such as attitudes and beliefs associated with the risk of sexual offending, beliefs that viewing CSEM does not harm victims, or that children can consent to sexual interactions). These cognitions are strong predictors of both online and contact sexual recidivism; Beier et al., 2015; Paquette & Brouillette-Alarie, 2024; Seto et al., 2023); development of healthy relationships (including interpersonal skills, understanding appropriate relational dynamics, and promoting positive emotional bonds; Seto et al., 2023); agency and motivation (i.e., contemporary treatment models increasingly emphasize personal agency, individual values, and motivation for change; Beier et al., 2015; Fromberger et al., 2021; Garrington et al., 2023; Heffernan & Ward, 2015; Seto et al., 2023). Finally, although the development of victim empathy is a common target in treatment programs for sexual offenders, the empirical evidence supporting its effectiveness and relevance—particularly for internet-based offenders—is weak and inconclusive. Some studies suggest that an excessive focus on this domain may be disproportionate to its demonstrated impact on reducing recidivism, especially considering that many online offenders do not present general empathy deficits. Rather, their difficulty lies in recognizing the individuals depicted in abusive material as victims, due to the absence of direct victimization by them against the depicted children (Babchishin et al., 2015; Barros et al., 2022). Nonetheless, given its prominence in present interventions, we have decided to retain victim empathy as one of the thematic categories against which to categorize the treatment targets of these existing programs (Table 2). All the programs included in this systematic review targeted atypical sexuality, offense-supportive cognitions and agency and motivation. Development of healthy relationships and victim empathy were a key focus in eight of the studies. Additionally, self-regulation and behavioral control was highlighted in seven studies. Treatment Outcomes Across the studies included in the review, a variety of methods were used to assess treatment effectiveness, ranging from self-report measures to structured clinical tools and risk assessment instruments. Most studies (Beier et al. 2015; Gillespie et al., 2016; Konrad et al., 2018; Lätth et al., 2022; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020) relied primarily on self-report questionnaires administered before and after the intervention. Others employed more comprehensive strategies, such as combined clinical interviews with self-reported questionnaires (Beier et al. 2015), and actuarial tools such as the Risk Matrix 2000 (Thornton et al., 2023) alongside self-reported measures (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Middleton et al. 2009). In the case of Campbell-Fuller and Craig (2009), these assessments were not directly administered by the researchers but derived from post-treatment file information, including therapist reports and risk evaluations. Additionally, Campbell-Fuller and Craig (2009) employed therapist reports and participant-maintained behavior diaries to monitor fantasy patterns. Dervley et al. (2017) uniquely applied semi-structured interviews to explore participants’ subjective experiences of treatment-related changes. Middleton et al. (2009) developed the i-SOTP for offenders convicted of an internet-related sexual offence who were assessed as low, medium, or high risk. The program was evaluated for its effectiveness through pre- and post-treatment analyses involving 264 participants (Middleton et al., 2009). Participants completed self-report measures of pro-offending attitudes, socio-affective functioning, locus of control, and impulsiveness. The results indicated a significant improvement in self-esteem, emotional loneliness, locus of control, perspective-taking, personal distress, under-assertiveness, motor and cognitive impulsivity, non-planning, victim empathy, and cognitive distortions. However, there were nonsignificant changes in empathic concern, fantasy, and emotional congruence. Specifically, 53% of participants achieved a treated profile, indicating positive treatment outcomes, while 47% did not achieve a treated profile. Campbell-Fuller and Craig (2009) presented a detailed account of approximately two-year therapeutic intervention employing the C-SOGP followed by behavioral stimuli for a 29-year-old male convicted of a crime involving the use of CSEM. The study focused on analyzing self-reported fantasies, masturbation behaviors, and the time allocated to these activities. During the initial eight-week period, corresponding to the phase when the individual received solely the C-SOGP, there was a notable prevalence of paraphilic sexual fantasies compared to non-paraphilic ones, poor relapse prevention plans and little cognitive/avoidance strategies to avoid future re-offending, having a high-risk evaluation of being reconvicted for a sexual offence. However, following the introduction of olfactory aversion and directed masturbation techniques, there was an observable increase in the time spent masturbating to non-paraphilic fantasies, alongside a general reduction in the frequency of masturbatory behavior. In post-intervention, there was a significant decrease in the time devoted to masturbating to paraphilic fantasies, while the increase in time spent on non-paraphilic fantasies was not statistically significant. BEDIT was also employed in two studies (Beier et al., 2015; Konrad et al., 2018). Beier et al. (2015) conducted a non-randomized waiting-list design to assess the impact of the BEDIT on dynamic risk factors and sexual behaviors. This intervention integrated cognitive-behavioral therapy, good lives model, psychopharmacology, and relapse prevention strategies. The intervention group included 53 individuals who completed the treatment program and provided complete data on dynamic risk factor measures. Among these participants, 16 had committed exclusively offenses related to CSEM, while another 16 had a history of both online and contact sexual offenses involving minors. The control group (n = 22) was retrospectively formed from individuals who provided complete data at two pre-treatment assessment points, with an average waiting time of 12 months. BEDIT was administered for a minimum of 45 weeks, with weekly 3-hour sessions. Among participants with offenses exclusively related to CSEM, the results indicated significant reductions in offense-supportive attitudes from pre- to post-treatment assessments. However, no significant differences were observed between the two assessment points for the remaining measures. Conversely, individuals who committed both online and contact offenses demonstrated significant reductions from pre- to post-treatment assessments in emotional loneliness, hostility toward women, emotional victim empathy deficits, offense-supportive attitudes, coping self-efficacy deficits, and sexual preoccupation. Comparisons between the treatment and control groups revealed that treated individuals exhibited lower cognitive victim empathy deficits compared to untreated individuals. No significant differences were observed between groups for the remaining dynamic risk factor measures. Relapse occurred for both child sexual abuse and child pornography-only convicted individuals, with rates in the treated group at 20% and 91%, respectively. Notably, 24% of participants who had previously committed only contact child sexual offenses reported engaging with CSEM for the first time during treatment. Konrad et al. (2018) conducted a qualitative study focusing on a 47-year-old man who engaged in the consumption of CSEM, aiming to evaluate the effectiveness of the BEDIT. This therapy integrated elements of the good lives model, risk-need-responsivity, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and pharmacological intervention. The program comprised 12 modules, spanning 55 three-hour sessions over a period of 23 months. Findings indicated that depressiveness, loneliness, hypersexuality, and psychosocial impairment were no longer clinically significant post-intervention. While the overall risk score remained moderate due to unchanged coding for sexual deviancy, there was a notable improvement in self-regulation skills. Additionally, the individual reported sustained well-being. The patient found it beneficial to openly discuss and address sexual fantasies, which helped overcome feelings of shame. Moreover, he expressed confidence in abstaining from the use of CSEM after disclosing his struggles to his supportive wife. Their relationship saw improvements in intimacy, communication, and sexual relationship. In terms of relapse, the patient reported no instances of CSEM use, maintaining abstinence for a period of three years. The Inform Plus intervention was employed in two papers (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016), with the participants in Dervley et al. (2017) comprising a subsample of those included in the Gillespie et al.'s (2016) study. Gillespie et al. presented a detailed examination of an eleven-week therapeutic intervention, rooted in cognitive-behavioral therapy and the good lives model supplemented by a psychoeducational component, within a cohort of 92 individuals. The pre-post outcome analysis revealed a significant reduction in depression, anxiety, and stress levels. Moreover, there was noted enhancement in social competency, emotion regulation, social skills, empathy, and a reduction in offense-supportive attitudes. Notably, during the eight to 12 weeks follow-up period, sustained improvements were observed in depression, social anxiety, self-esteem, emotional loneliness, and internal locus of control. Additionally, participants reported decreased utilization of expressive suppression strategies. The study also observed the maintenance of reduced clinical characteristics (anxiety and stress), decreased social anxiety, increased self-efficacy, adoption of emotion regulation strategies, improved empathic functioning, and reduced distorted thinking. However, a decrease in self-management was observed following treatment. Importantly, participants did not demonstrate excessive levels of socially desirable responding. Dervley et al. (2017) employed thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) to examine the perceived impact of the Inform Plus program on a sample of 13 individuals convicted of offenses related to the use of CSEM. This involved analyzing self-reported feedback from offenders, their relatives, and external professionals (e.g., police officers, probation officers). The study investigated perceived changes in participants' abilities to manage thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to internet offending, as well as their experiential accounts of completing the Inform Plus program. This included insights into participants’ management of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, perspectives from partners and/or parents, and feedback from external professionals. The findings revealed perceived improvements in the ability to manage offense-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, initiation of self-driven change, enhanced communication skills, and the establishment of achievable goals for a future free from offending. Schulz et al. (2017) and Wild et al. (2020) conducted studies with the Prevention of Sexual Abuse (PsM) program. Schulz et al. (2017) conducted a comprehensive evaluation of the PsM intervention program, implemented in two distinct formats (individual and group). The individual intervention consisted of a 90-hour program, while the group intervention spanned 120 hours. Results from the individual intervention revealed improvements in life satisfaction, subjective psychological distress, and perceived ability to maintain sexual self-control at the post-intervention assessment. Additionally, there was a decrease in the perceived risk of reoffending, although no improvements were observed in the level of cognitive distortions. The participant reported a relatively high level of self-efficacy overall and there was no relapse in consuming CSEM. Conversely, findings from the patient who received only group intervention indicated improvements in the perceived risk of reoffending, greater life satisfaction, and level of cognitive distortions at the post-intervention assessment. Additionally, there was a decrease in psychological distress, although no changes were noted in the perceived ability to maintain sexual self-control or experienced self-efficacy. The participant also reported a decrease in the use of CSEM, limiting consumption to less than once a month. At the 1-year follow-up, this patient exhibited a stable low level of cognitive distortions, reported a sense of self-efficacy in general, perceived ability to maintain sexual self-control, and perceived risk of committing a hands-on sexual offense. Moreover, the patient reported no psychological distress and expressed satisfaction with their life and confirmed no hands-on offenses in the past six months, while maintaining infrequent use of CSEM (less than once a month). Wild et al. (2020) conducted a quantitative descriptive study to assess the impact of the PsM program on various outcome measures, including self-efficacy, offense-supportive attitudes, personal well-being, subjective sexual self-regulation, relapse, and dropout, across two intervention groups. The first group (Group 1, n = 9) was evaluated at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and at a 1-year follow-up. Results indicated that post-intervention evaluation showed nonsignificant changes in self-efficacy, self-perceived overall psychological distress, self-reported life satisfaction, subjective risk perception, and self-perceived ability to control paraphilic impulses. However, there was a significant reduction in offense-supportive attitudes and in the frequency of CSEM use. At the follow-up evaluation, there were nonsignificant changes in self-efficacy, self-perceived overall psychological distress, self-reported life satisfaction, and subjective risk perception, with maintenance of reductions in offense-supportive attitudes and frequency of CSEM use. The second group (Group 2, n = 25) underwent only pre- and post-treatment evaluation. The findings revealed nonsignificant changes in self-efficacy and self-reported life satisfaction, along with a significant reduction in offense-supportive attitudes, self-perceived overall psychological distress, and subjective risk perception. Lastly, Lätth et al. (2022) conducted an RCT to assess the efficacy of an anonymous internet-based CBT-informed intervention on various outcome measures compared to a placebo control. The study evaluated self-reported time spent watching children for sexual purposes (included time spent using CSEM), interacting sexually with children, socializing with children for purposes, the severity of CSEM viewed, quality of life, and adverse events and treatment effects. A total of 160 participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (IG group, n = 80) or the control group (n = 80). Participants were assessed at baseline and then every week/module, with a one-month follow-up. Regarding recidivism, the intervention group demonstrated a significant decrease in weekly time spent watching children for sexual purposes (including the use of CSEM) and related behaviors compared to control group post-treatment. Both groups exhibited decreased content severity of CSEM used. While no significant difference was found between groups in the proportion of participants who ceased viewing CSEM entirely, those in the Prevent It group reported a significantly higher age of the youngest child depicted in the material viewed during the past week. At the 12-week follow-up, the intervention group demonstrated a significant decrease in weekly viewing time compared to control group, along with fewer reported negative side effects. Additionally, half of the participants in both groups reported not using CSEM during the preceding week at post-treatment or follow-up, with no significant between-group differences. Results also revealed positive effects at follow-up, including increased awareness of thoughts and behaviors (no specific details in the article), support from therapists, acquisition of useful tools (no specific details), feelings of hope, and reduced use of child sexual exploitation materials compared to the control condition. Finally, dropout rates for interventions ranged from 0% (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Gillespie et al., 2016; Konrad et al., 2018; Schulz et al., 2017) to 48.36% (Wild et al., 2020). Two articles did not report dropout rates (Dervley et al., 2017; Middleton et al., 2009), while the remaining studies reporting dropout rates of 29% (Lätth et al., 2022) and 29.7% (Beier et al., 2015) (See Table 3). In this review, we comprehensively examined the effectiveness of existing intervention programs targeting individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children. Nine studies were identified, revealing several challenges related to study design, methodological quality, and intervention protocols. Most of the studies used a pre-post-intervention design, not adapted or developed for individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children. Notably, most studies did not include control or comparison groups, leaving plausible alternative explanations for the observed changes, such as regression to the mean. Furthermore, the methodological quality of many studies was deemed insufficient according to the analysis framework used (MMAT; Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Dervley et al., 2017; Schulz et al., 2017). All but one of the samples (that did not specified the biological sex, just the gender), were entirely composed of male(s) highlighting a significant gap in research and interventions specifically targeting women in the context of online sexual crimes involving children. Only three studies included representative samples of the population (Lätth et al., 2022; Middleton et al., 2009; Schulz et al., 2017), limiting the generalizability of the results to the populations of interest. Among these, only one was an RCT (Lätth et al., 2022), which included some methodological limitations according to the MMAT criteria, as stated previously. These factors weaken the strength of conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the interventions studied. Treatment Approaches Cognitive-behavioral therapy was the most used approach, followed by the good lives model, with few studies adopting all elements of the risk-need-responsivity (RNR; Bonta & Andrews, 2017) model. Cognitive-behavioral therapy focuses on identifying and addressing potential risk factors for reoffending by exploring hypothetical risky situations, emotions, and moods, enabling individuals to develop strategies to manage, avoid, or modify these triggers through proactive planning (Seto, 2013; Ward & Gannon, 2006; Ward & Hudson, 2000). Good lives model emphasizes the continuous pursuit of purpose and meaning in life to achieve universal human “goods”, positing that sexual offending may stem from misguided attempts to fulfill fundamental human needs (Ward & Brown, 2004; Ward & Gannon, 2006). By addressing the risk factors, criminogenic needs, and individual responsivity of offenders, the RNR model provides a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing intervention programs that aim to rehabilitate sexual offenders and reduce the likelihood of re-offending (Bonta & Andrews, 2017). Programs did generally adhere to the Need Principle in that they targeted a variety of important dynamic risk factors, such as sexual self-regulation, offense-supportive cognitions, and interpersonal deficits. However, few studies systematically assessed participants’ risk levels before treatment, as prescribed by the Risk Principle (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Konrad et al., 2018; Middleton et al., 2009). Henshaw et al. (2020) argue that, given their typically low rates of official recidivism, most individuals who commit online sexual offenses may only require low-intensity interventions, or, in some cases, no treatment at all. However, five out of six studies included in the current review self-disclosed recidivism, suggesting a higher incidence of reoffending than what is typically captured in official judicial records. This suggests that intervention may still be appropriate, even for individuals assessed as presenting lower risk, and highlights the limitations of relying exclusively on official data sources. Incorporating self-report measures offers added value by providing a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of treatment outcomes and offense patterns that may otherwise go undetected. Although some cases of reoffending were recorded, a substantial reduction in the frequency of offending behavior was observed. Moreover, no escalation in criminal conduct was reported, and notable improvements were documented in clinical symptoms associated with risk factors for this type of offending, all of which are considered key indicators of success in intervention programs (Duwe & Clark, 2015; Giesbrecht, 2023; Schmucker & Lösel, 2015). Other Potential Treatment Approaches Third-wave therapies like Acceptance and Commitment Therapy have shown promise in reducing offending behaviors in forensic settings (Cunha et al., 2024; Eisenbeck et al., 2016). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy helps individuals accept negative emotions while focusing on actions that promote a valuable and meaningful life (Harris, 2013). Although only the PsM program (Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020) used Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, it may be particularly effective for individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children due to its emphasis on emotional regulation and self-awareness, areas where these individuals often struggle (Garrington et al., 2018; Henshaw et al., 2017; Steene et al., 2023). Also, Garrington et al. (2023) suggested that Compassion-Focused Therapy may be advantageous for online sexual offending cases because, when combined with risk-relevant approaches, it helps tailor interventions to individual needs, supports rehabilitation, and enhances community protection by addressing both risk factors and emotional well-being. Recommendations Given the complex and heterogeneous nature of individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children, we advocate for a multi-approach intervention framework that integrates cognitive-behavioral therapy, the good lives model, and elements from third wave therapies, grounded in the RNR framework. Research has identified several key risk factors that appear associated with individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children. These include atypical sexual interests, impulsivity, engagement in risky online sexual behaviors, offense-supportive cognitions, interpersonal difficulties such as social isolation, a history of childhood sexual abuse, and sociodemographic variables such as lower parental education and prior experiences of offline abuse (Babchishin et al., 2015; de Santisteban & Gámez-Guadix, 2017; Paquette & Brouillette-Alarie, 2024; Seto, 2025; Seto et al., 2023; Steene et al., 2023). There is a lack of existing, validated risk tools for individuals who have committed exclusively online sexual crimes involving children. A static risk tool developed specifically for men convicted of offenses related to CSEM is the Child Pornography Offender Risk Tool (CPORT; Seto & Eke, 2015). The CPORT is a seven-item actuarial scale that has demonstrated moderate predictive accuracy for both five-year sexual recidivism (AUC = .72) and online recidivism (AUC = .74; Eke et al., 2018). Moreover, it has the largest body of available research for this population, with effect sizes among the highest (Helmus et al., 2025). To assess dynamic risk among this group, Helmus et al. (2025) recommend the STABLE-2007 and ACUTE-2007 (Fernandez et al., 2015), based on research by Babchishin et al. (2023). They also suggest combining static and dynamic risk assessments to optimize the accuracy of recidivism risk evaluations. To address the Responsivity Principle of the RNR model, we recommend individualized treatment, tailored to their learning styles and other responsivity considerations. Although the current evidence base does not allow for definitive conclusions regarding optimal treatment dosage, the literature suggests that individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children generally require lower treatment intensity compared to those who commit contact offences (Henshaw et al., 2020). This recommendation aligns with their typically lower risk of engaging in sexual contact offenses and is supported by the findings of this systematic review. Treatment Targets The systematic review identified a broad range of treatment targets that were organized into six key themes, reflecting the criminogenic needs and psychological vulnerabilities of those who commit exclusively online crimes involving children (Babchishin et al., 2018; Merdian et al., 2018; Steene et al., 2023). Atypical sexuality, along with offense-supportive cognitions and agency and motivation were present in all studies. Additionally, eight studies focused on the development of healthy relationships and victim empathy. Most individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children do not exhibit deficits in empathy but rather in victim awareness, failing to recognize the harm caused to children involved in CSEM (Bartels & Merdian, 2016). Last, promoting emotional regulation and behavior control was highlighted as critical in seven studies (Garrington et al., 2018; Steene et al., 2023). Consistent with the findings of this review, we propose that relevant treatment targets for individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children encompass atypical sexuality, particularly sexual preoccupation and sexual interest in children (Babchishin et al., 2015; Beier et al., 2015; Seto et al., 2023); deficits in self-regulation and behavioral control, which are closely associated with ongoing offending (Beier et al., 2015; Garrington et al., 2023); and specific offense-supportive cognitions, such as minimization, justification, and the belief that viewing abusive images does not harm victims or that children can consent to sexual interactions (Beier et al., 2015; Paquette & Brouillette-Alarie, 2024; Seto et al., 2023). Additionally, interventions should target the development of healthy interpersonal relationships by fostering interpersonal skills, promoting understanding of appropriate relational dynamics, and strengthening emotional bonds (Seto et al., 2023). Finally, recent treatment models emphasize the importance of agency and motivation for change, shifting the focus beyond risk reduction to include the identification of dynamic and static risk factors, monitoring of risk-relevant behaviors, and the development of individualized strategies to prevent recidivism (Beier et al., 2015; Fromberger et al., 2021; Garrington et al., 2023; Heffernan & Ward, 2015; Marshall & Marshall, 2017; Seto et al., 2023). Targeting these domains has the potential to enhance self-regulatory capacities, reduce the risk of reoffending, and support long-term behavioral change, provided that treatment is tailored to an individual’s specific criminogenic needs and offense-related motivations (Beier et al., 2015; Paquette & Brouillette-Alarie, 2024; Seto et al., 2023; see Table 4 for an overview of treatment targets and corresponding psychological and risk assessment tools). However, while these domains appear to be promising treatment targets, more methodologically robust research is needed to empirically identify which factors are most strongly associated with risk of reoffending among individuals who engage in online offenses. Table 4 Practice Guidelines for Clinicians: Treatment Targets and Assessment Instruments in Online Sexual Offending   Note. STABLE-2007 should be combined with Child Pornography Offender Risk Tool (CPORT; Seto & Eke, 2015) to optimize the accuracy of recidivism risk evaluations, and guide the clinicians' decisions about treatment dosage and targets. Treatment Outcomes Across the studies reviewed, treatment effectiveness was primarily assessed using self-report questionnaires. Such tools are often favored for their practicality, standardization, and capacity to capture subjective experiences related to symptoms, well-being, and quality of life (Carr et al., 2020; Hendriks et al., 2020; van Agteren et al., 2021); however, they are not without limitations, including susceptibility to biases such as social desirability, minimization, and memory distortions, particularly salient in the context of sensitive or stigmatized behaviors. Clinical interviews, used in a minority of the reviewed studies, offer valuable contextual insights and are considered the gold standard for in-depth assessment and diagnosis (Caro et al., 2023). Similarly, the use of actuarial tools and file information, as seen in a few studies, provides more objective data and helps mitigate biases in self-report. Nevertheless, these sources may also suffer from limited standardization or incomplete records (Boonpattharatthiti et al., 2024), which can undermine their reliability. Integrating self-reports with clinical interviews, file data, behavioral monitoring, and, where possible, ecological momentary assessments (i.e., real-time self-reports collected in participants’ natural environments) can enhance the robustness and ecological validity of findings (Fu et al., 2020; Lipsey & Wilson, 1993). Future research should use multiple assessment strategies to provide a more accurate and nuanced picture of treatment effectiveness. Most studies assessing recidivism (Campbell-Fuller & Craig, 2009; Lätth et al., 2022; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020) indicated that the programs did manage to significantly reduce the use of CSEM. All studies that assessed clinical changes showed improvements across most treatment targets (Beier et al., 2015; Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016; Konrad et al., 2018; Lätth et al., 2022; Middleton et al., 2009; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). There were several differences regarding the modality of the intervention applied. Regarding symptomatology assessment, the only program that showed deteriorations in one of the treatment targets was delivered in a group format (Gillespie et al., 2016). Simultaneously, the article that presented the highest recidivism rate (91%), also implemented a group approach (Beier et al., 2015). The authors suggested that group interventions for individuals who have committed online sexual offenses involving children may lead to “contamination” among participants, potentially reinforcing criminal behaviors (Beier et al., 2015). Additionally, it was observed that both individual and group programs that reported recidivism noted a reduction in criminal behaviors. However, some group programs showed negative results in certain treatment targets or did not demonstrate significant pre-post changes. While caution is needed when generalizing these conclusions due to study limitations, it raises the question of whether group programs have limitations in addressing individual responsivity. We found heterogeneity in adherence to intervention programs, reflecting differences in program approaches, participant motivation, and the quality and support provided during the interventions. For instance, the program by Wild et al. (2020), which reported the highest dropout rate (48%) attributed most dropouts to motivational issues, highlighting the need to reinforce behavioral techniques aimed at enhancing motivation. However, the long treatment duration (approximately two years for the majority of patients) may have contributed to participant attrition, further underscoring the importance of considering the RNR model to reassess the adequacy and individualization of treatment length. Lätth et al. (2022), reported a 29% dropout rate. The online format of the program may have impacted participants’ motivation and engagement, possibly contributing to attrition. These findings suggest that it is essential to assess individual responsivity and consider how the mode of delivery may interact with participant characteristics. The study by Beier et al. (2015), was administered in a group setting, which may have limited the individualized attention and support necessary for some participants, contributing to a 30% dropout rate. Programs with no reported dropouts were mostly case studies, except for one (Dervley et a., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016, involving the same participants and intervention), which involved a self-selected sample. These observations suggest that participant motivation and the structure of the programs appear to play a fundamental role in adherence and the success of intervention programs. Also, the combination of being motivated and required to attend in-person sessions may contribute to lower dropout rates, as opposed to online programs where disengagement might be easier. There was heterogeneity in the methods used to evaluate interventions. The most common evaluation method was the combined use of pre-post treatment change and recidivism (Beier et al., 2015; Konrad et al., 2018; Lätth et al., 2022; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020), followed by only the measurement of changes in pre-post treatment variables (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016; Middleton et al., 2009). The use of pre-post treatment changes and recidivism rates in combination may help determine if treatment promotes changes in criminological factors, reduces recidivism, and if those changes are linked to desistance from offending. This also underscores the necessity for RCTs that can provide stronger empirical evidence to determine the effectiveness of existing interventions. While RCTs are considered the gold standard for evaluating intervention efficacy, Lennox et al. (2022) argue that more flexible and adaptive research designs are also essential. These approaches can provide valuable insights into intervention outcomes while addressing the practical challenges of forensic settings. Another critical gap in the literature is that most intervention programs for online sexual offenders are not specifically tailored to this population. Many programs may not meet the specific needs of this population, raising concerns about whether the treatment targets are appropriate. For example, internet-only consumers of CSEM were found to have low overall endorsement of offense-supportive cognitions exhibited by those who commit contact sexual offenses (Steel et al., 2020), exhibiting instead ideas such as “virtual is not real” (Paquette & Cortoni, 2020). Also, most individuals who have sexually offended against children online do not exhibit general victim empathy deficits (Elliott et al., 2013; Paquette & Cortoni, 2020; Steel et al., 2020) and instead demonstrate problems with victim awareness as they fail to appreciate that children are harmed to facilitate their involvement with CSEM (Bartels & Merdian, 2016; Kettleborough & Merdian, 2016). Three intervention programs in the review addressed this aspect (Dervley et al., 2017; Gillespie et al., 2016; Middleton et al., 2009; Schulz et al., 2017; Wild et al., 2020). Although treatment programs have been developed based on clinical and empirical evidence, some intervention targets are less well-founded (e.g., self-esteem, stress management, denial, disclosure, general self-efficacy). Self-esteem, although identified as a prevalent factor in this population (Merdian et al., 2018; Steene et al., 2023), still lacks investigation regarding its impact on recidivism. The literature also emphasizes that individuals who consume CSEM often exhibit unique risk factors, such as paraphilic interests, which may require specialized interventions in addition to individual or group therapy, such as psychopharmacological treatment. The World Federation of Societies in Biological Psychiatry guidelines state that pharmacological treatment is only appropriate for high-risk individuals (Thibaut et al., 2010), underscoring the need for accurate risk assessment to determine the intensity and type of intervention required. Without tailored interventions based on these assessments, treatment programs risk failing to address the underlying causes of offending behavior, thereby reducing their overall effectiveness. For higher-risk individuals, more intensive, in-person treatment programs, such as the one implemented by Beier et al. (2015) may be necessary. These programs are demanding and costly, running for extended periods (e.g., a year), but are justified for individuals with more severe risk factors and criminogenic needs. On the other hand, online interventions like the Prevent It program offer a less intensive but still structured and guided approach. These interventions may be more suitable for moderate-risk individuals who may not require the same level of resources or intensity. However, online interventions provide flexibility and accessibility, making them a valuable option for a broad range of individuals at risk of perpetrating child sexual exploitation and abuse, particularly those who are motivated to engage in treatment but face logistical or financial barriers to in-person participation. A third option includes self-help websites and helplines, which provide guidance and resources for individuals at lower risk. These interventions are the least intensive and most cost-effective, making them ideal for individuals at lower risk or those seeking preliminary support before engaging with more intense interventions. Self-help websites and helplines could also be helpful in mobilizing motivation to engage with more intense interventions. However, they are likely insufficient for higher-risk individuals, as they lack the personal guidance, accountability, and comprehensive support required to address more deeply ingrained behaviors or paraphilic interests. Strengths and Limitations Overall, our findings suggest that intervention programs for perpetrators of online child sex offenses have shown promising outcomes, providing preliminary support for their use. However, despite these contributions, several limitations must be acknowledged. The main limitation is that there are few outcome studies, making it challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the effectiveness such interventions. Additionally, it was not possible to meta-analyze or quantitatively examine moderator candidates, further limiting the ability to assess how different factors, such as age or risk level, might influence the effectiveness of these interventions. The scarcity of studies with comparison conditions further complicates the ability to evaluate the success and generalizability of these programs. More rigorous research with control or comparison groups is needed to better understand and improve treatment approaches for individuals who commit online sexual crimes involving children. While the use of the MMAT tool provided a systematic approach to evaluating the quality of the included studies, we acknowledge the potential limitations associated with its application. Specifically, the subjective nature of some of the criteria may have affected the consistency of ratings. To mitigate this concern, the rating process was conducted by two experienced researchers, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third researcher. Furthermore, the MMAT tool does not differentiate between the inherent strengths of different designs when comparing overall quality scores. As such, studies employing RCT designs, despite being widely recognized as the gold standard for establishing intervention efficacy, may still receive lower quality ratings than qualitative or non-randomized studies. This is exemplified by the trial conducted by Lätth et al. (2022), which, despite its ability to support strong causal inference, received a lower score than the qualitative study by Dervley et al. (2017), which cannot say as much about causal effects. Therefore, the interpretation of study quality should consider the design-specific strengths of RCTs, which are not fully captured by the MMAT’s uniform scoring framework. This study demonstrates the positive effects of psychological intervention on risk-related indicators for individuals who engage in online sexual offenses involving children (e.g., emotional regulation, cognitive distortions, social relationships, and clinical symptoms). However, the identified limitations across existing studies highlight the need for continued empirical research using rigorous methodology to evaluate the effectiveness of these intervention programs. Further research is essential to better understand the effectiveness of rehabilitation for online sexual offending. This can be achieved through RCTs, larger sample sizes, inclusion of control groups, and longer follow-up periods. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Gouveia, C., Silva, T., Cunha, O., Seto, M. C., Maimone, S., & Caridade, S. (2026). A systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions for individuals who have committed online sexual crimes involving children. Psychosocial Intervention. Article e26080 https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a16 |

Cite this article as: Gouveia, C., Silva, T., Cunha, O., Seto, M. C., Maimone, S., & Caridade, S. (2026). A Systematic Review on the Effectiveness of Interventions for Individuals Who Have Committed Online Sexual Crimes Involving Children. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260808. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a16

Correspondence: id11238@uminho.pt (C. Gouveia).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS