Raising Generation Z Children in China: Parenting Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment

Marta Alcaide, Oscar F. Garcia, Fangzhou Chen, and Fernando Garcia

University of Valencia, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a9

Received 13 February 2025, Accepted 1 April 2025

Abstract

Objective: This study aims to analyze the relationship between parenting styles, i.e., authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful, and psychosocial adjustment, i.e., aggression, self-concept, and emotional-social competence, among Generation Z (Gen Z) individuals. Method: The participants were 1,417 Chinese individuals, 736 young adults (born between 2003-2005) and 681 adolescents (born between 2006-2008). A multivariate multifactorial design 4 × 2 × 2 × 2 was applied. Dependent variables were various components of child psychosocial adjustment (aggression, five dimensions of self-concept and emotional-social competence). Independent variables were parenting styles, children antisocial tendency during adolescence, sex, and age (adolescent vs. young adult cohorts). Results: Children from authoritarian homes reported higher levels of aggression, and the worst scores in self-concept and emotional-social competence. By contrast, the optimal results were consistently associated with warm parenting (i.e., authoritative and indulgent). Conclusions: Parental warmth was beneficial for Gen Z, including both adolescent and young adult cohorts. The present findings seriously questioned that the Chinese authoritarian parenting, which has often been related to positive outcomes—particularly for educational success—is beneficial for child psychosocial adjustment.

Keywords

Aggression, Parenting styles, Gen Z, Antisocial tendencyCite this article as: Alcaide, M., Garcia, O. F., Chen, F., & Garcia, F. (2025). Raising Generation Z Children in China: Parenting Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(2), 103 - 115. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a9

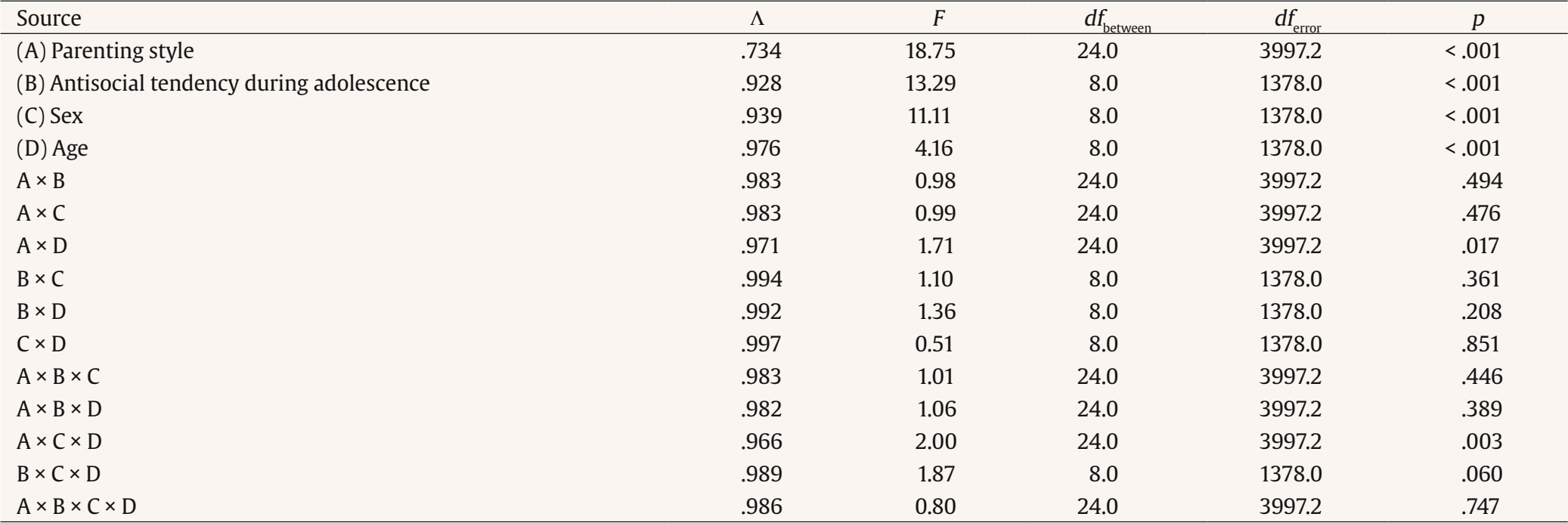

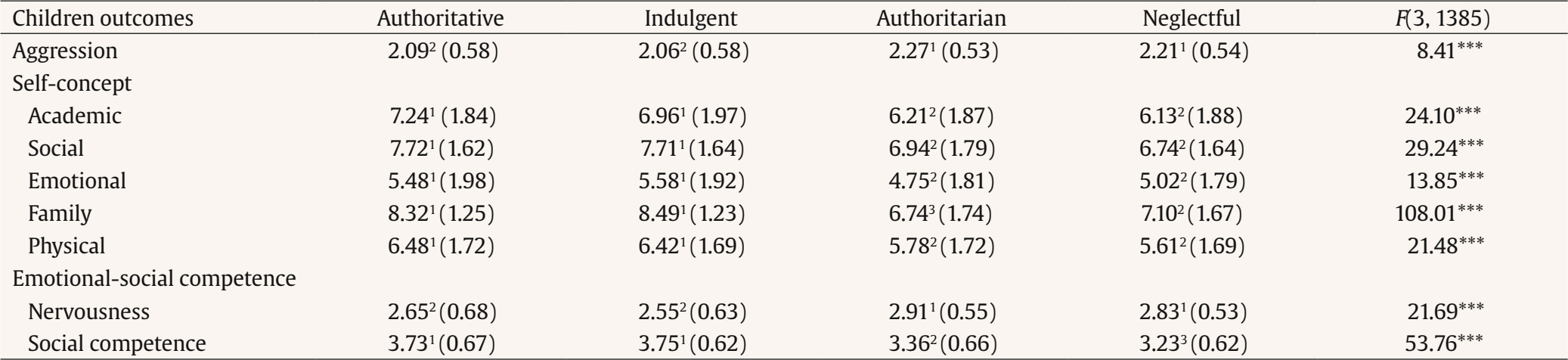

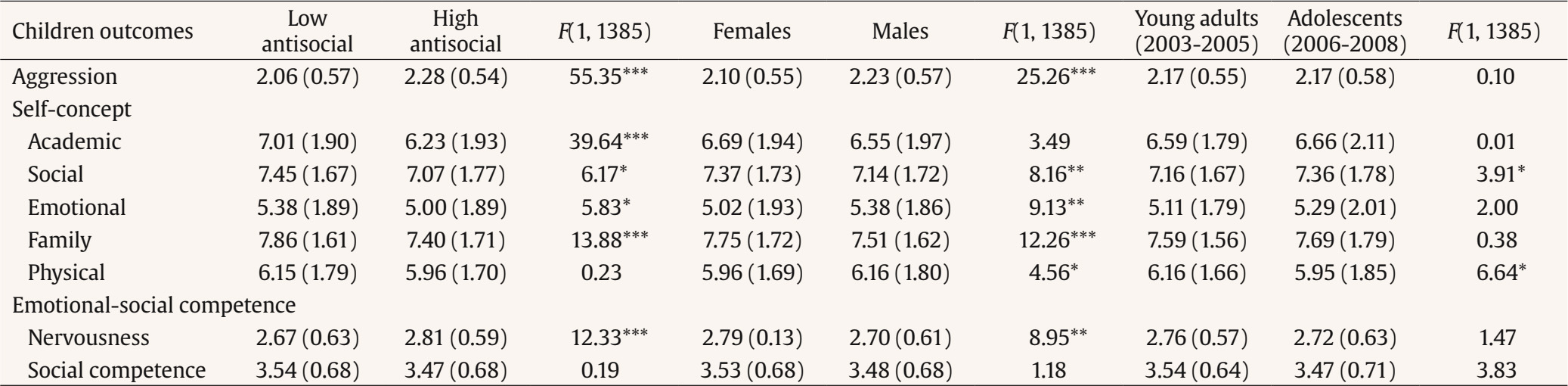

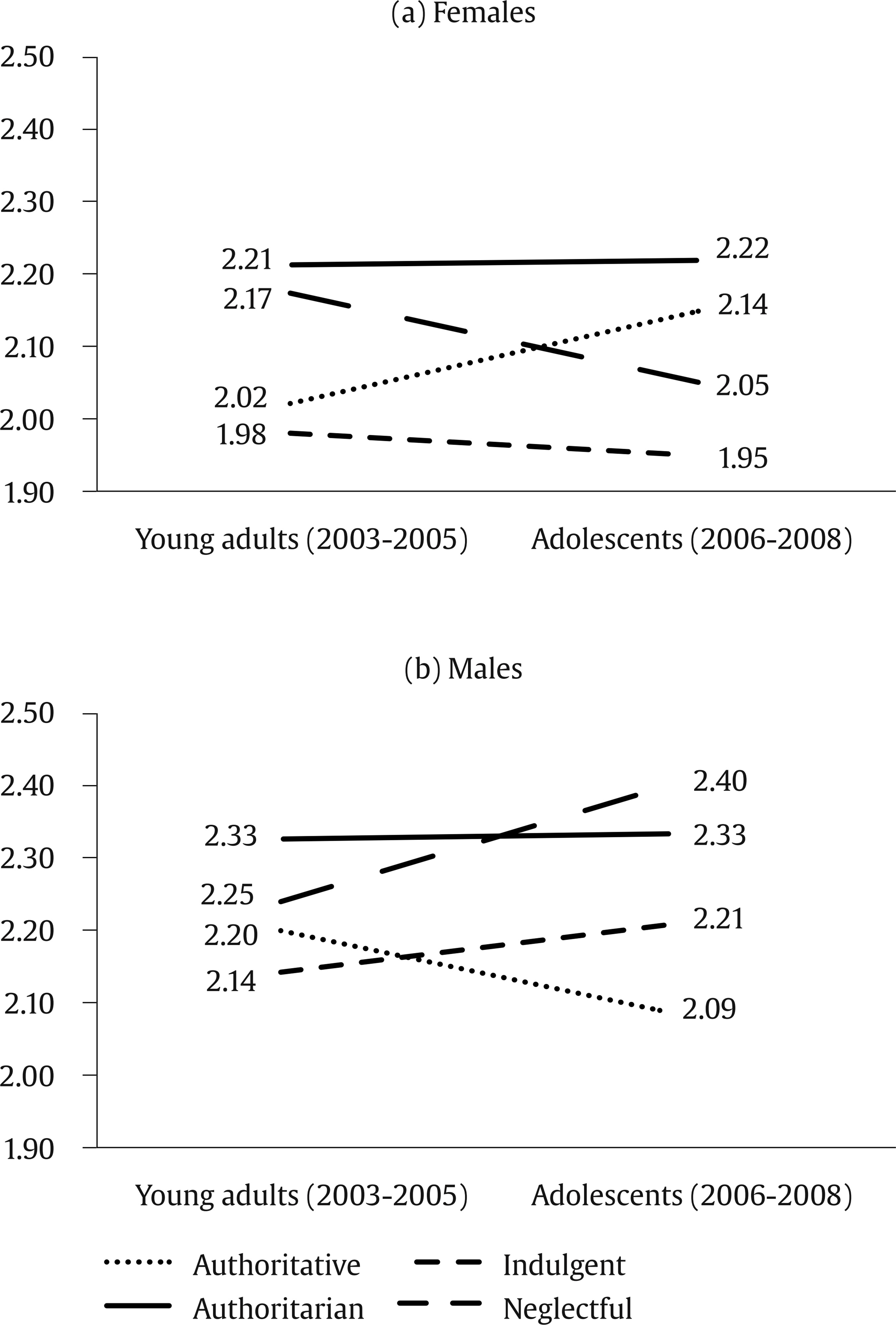

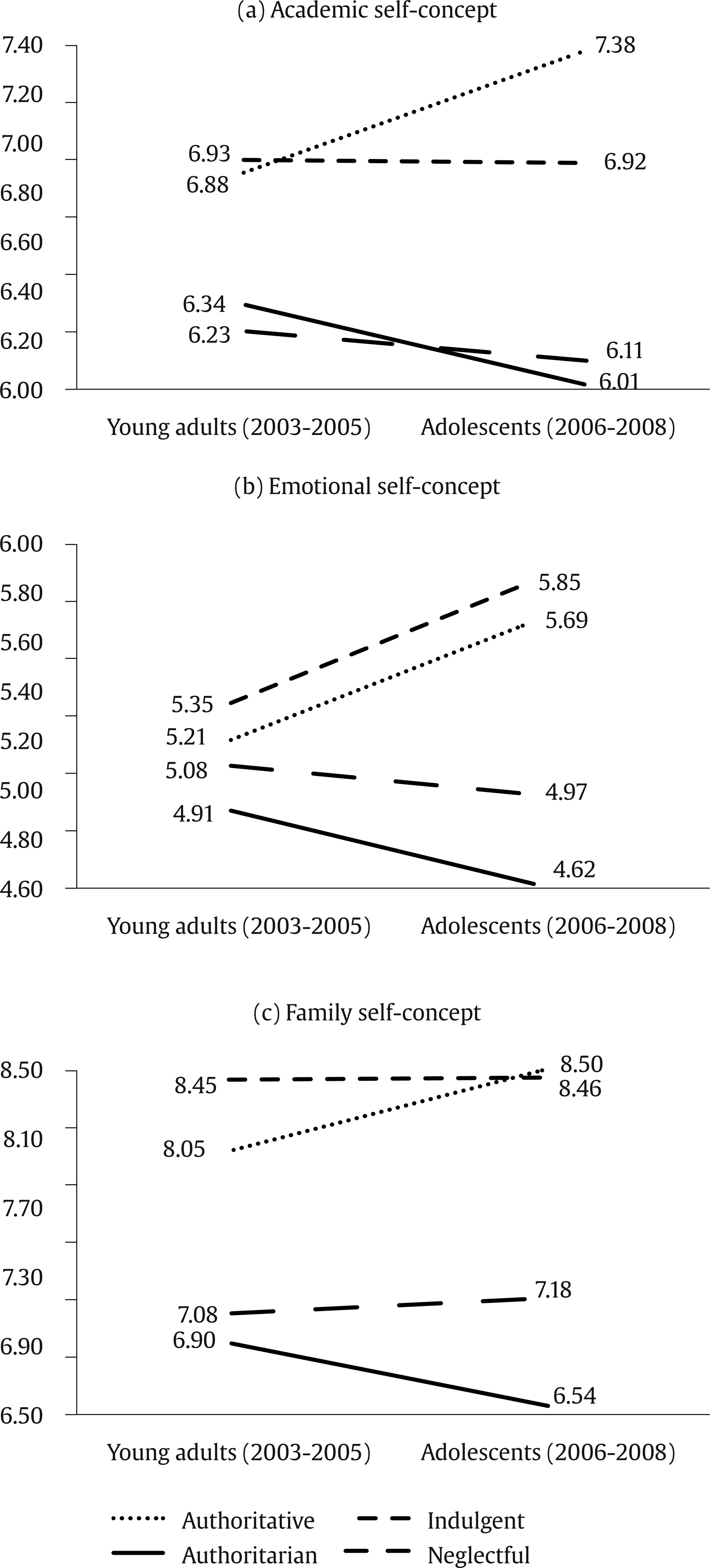

Correspondence: oscar.f.garcia@uv.es (O. F. Garcia).The present study aims to investigate the relationship between the way parents interact with their children and child psychosocial adjustment (i.e., aggression, self-concept and emotional-social competence) in Chinese Generation Z (Gen Z) individuals. Parental socialization uses a classical two-dimensional theoretical model (Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Schaefer, 1959; Sears et al., 1957). This model has universally been applied (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; F. Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991; Maccoby & Martin, 1983) and identifies two main dimensions (i.e., warmth and strictness). From the combination of these dimensions, four parenting styles are defined: authoritative (high warmth and high strictness), authoritarian (low warmth and high strictness), indulgent (high warmth and low strictness) and neglectful (low warmth and low strictness). The family serves as the primary social unit for individuals, establishing initial emotional connections with parents (O. F. Garcia et al., 2024; Gomez-Ortiz et al., 2025; Maccoby & Martin, 1983; Steinberg, 2001). Parents are responsible for transmitting the values and norms of the society in which their child is raised, facilitating socially desirable behaviors and promoting optimal psychosocial adjustment (Baumrind, 1978; Bowlby, 1969; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Maccoby, 1992). The dynamics of parent-child interactions significantly influence a child’s psychosocial adjustment, but the cultural context where parental socialization occurs also plays a critical role. Optimal parenting styles might vary across different cultural contexts (F. Garcia et al., 2019; Gomez-Ortiz et al., 2016; Martin-Blesa et al., 2024; Palacios et al., 2022; Pinquart & Kauser, 2018; Pinquart & Luak, 2024). Evidence indicates that even within a single country, such as the United States, multiple optimal parenting styles coexist, likely due to the cultural and ethnic variations present within American people (Baumrind, 1972; Chao, 2001; Darling & Steinberg, 1993). Among middle-class individuals in the United States, research suggests that the authoritative parenting style may be considered optimal, whereas children of authoritarian parents may have more problems and lower levels of psychosocial adjustment (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Lamborn et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). In contrast, among ethnic minorities in the USA, such as African-American and Chinese-American communities, the authoritarian parenting style might be viewed as more effective (Baumrind, 1972; Chao, 2001). In this line, some cross-cultural research also identifies not harmful consequences or even some benefits associated with the authoritarian parenting style in Arab (Dwairy, Achoui, Abouserie, & Farah, 2006; Dwairy, Achoui, Abouserie, Farah, et al., 2006; Dwairy & Menshar, 2006) and Asian societies (Ho, 1986; Y. Li et al., 2010; Quoss & Zhao, 1995). Vertical vs. horizontal as well as collectivistic vs. individualistic defines two general cultural traits proposed to explain differences in optimal parenting across various cultural contexts (F. Garcia et al., 2019; Shavitt et al., 2011; Triandis, 2001). Some scholars suggest that, depending on the cultural context of parental socialization, children might perceive their parents’ attitudes and behaviors in different ways (Martinez et al., 2021; Pinquart & Lauk, 2024; Triandis, 2001). In vertical collectivistic cultures, such as those found among poor ethnic minority families in the United States and in dangerous neighborhoods, children could perceive parental strictness as a form of care, affection, love, respect, and responsibility. This perception could help a child’s adaptation to difficult contexts (Brody & Flor, 1988; F. Garcia & Gracia, 2010; O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Randolph, 1995). However, in horizontal cultures—that do not prioritize hierarchical relationships—parental strictness tends to be less positively associated with child adjustment. In horizontal collectivistic cultures, where parent-child relationships are more egalitarian and individuals are more interdependent with the groups to which they belong (e.g., family, nation), children give more priority to group goals over their own. As a result, they may perceive parental strictness (e.g., supervision of behavior or imposition of rules) as a deprivation of their freedom, whereas parental warmth could be more beneficial for child adjustment (Calafat et al., 2014; O. F. Garcia et al., 2021). However, cultural variations in vertical vs. horizontal and collectivistic vs. individualistic have also been identified, which could lead to differences in optimal parenting from one generation to another (Bian et al., 2022; Gorla et al., 2024; Lansford et al., 2021). Interestingly, due to rapid globalization and technological advancement, cultural changes in China have emerged in Gen Z (individuals born after 1995) compared to previous generations (F. Tang, 2019). Moreover, traditional Chinese Eastern culture has undergone significant social changes in recent years. Chinese studies have observed a rise in individualism alongside a decline in collectivism. Children are becoming more autonomous, curious, expressive, and have liberal beliefs while showing less obedience and shyness (F. Tang, 2019; Zhou et al., 2018). Gen Z individuals exhibit different values across various countries; however, the values of China’s Gen Z are quite similar to those of the US Gen Z in certain aspects, such as being more confident, more secularly oriented, self-promoting, and professionally individualistic compared to previous generations (F. Tang, 2019). Parents play a crucial role in their children’s education and psychosocial adjustment (X. Lin et al., 2023). Younger Chinese generations show a significant increase in parental warmth, while the pattern of parental strictness remains less clear (Zhou et al., 2018). In contemporary Chinese society, there is a growing trend toward individualism and more egalitarian relationships among family members (i.e., horizontal culture) (Kisbu et al., 2023). It is possible that having more egalitarian parent-child relationships may render emotional distance and coldness (i.e., authoritarian parenting, strictness, and lack of warmth) detrimental, especially in a context where the hierarchy of the parent’s role has become less defined (F. Chen et al., 2024; X. Lin et al., 2023). Recent studies involving Chinese Gen Z children have found that the authoritative parenting style (characterized by high warmth and strictness) is negatively related to behavioral problems (X. Lin et al., 2023) and serves as a protective factor for self-esteem and self-concept, similar to the indulgent parenting style (which emphasizes warmth and non-strictness) (F. Chen et al., 2024). Additional research on Gen Z Chinese individuals indicates that the authoritative parenting style is positively associated with the development of a personal belief in a just world (J. Wang et al., 2024). Furthermore, parental care (a component of parental warmth) appears to be positively related to child adjustment in Chinese Gen Z (Zhu & Zhou, 2022). The Present Study The most recent literature on parenting has focused on Western cultures, while fewer studies have examined Eastern cultures. The present study aims to analyze parenting styles and their relationship with child psychosocial adjustment (i.e., aggression, self-concept, and emotional-social competence) in a culture that has undergone significant changes (i.e., China). Additionally, other independent variables analyzed include antisocial tendency during adolescence, sex, and age, in order to test both main and interaction effects. An important indicator of psychosocial maladjustment is aggression, defined as any behavior directed toward another with the immediate intent to cause harm (Anderson & Bushman, 2002). Recent decades have seen an increase in aggression (Marciano et al., 2020; Smeets et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2024), posing a public health threat (World Health Organization, 2015), particularly among Gen Z individuals (Boboc & Rosoiu, 2019). A significant body of literature supports the link between aggression and various personal and social adjustment problems, including internalizing and externalizing problems (Card et al., 2008; Gómez-Ortiz et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2008; Teng et al., 2015). Aggression correlates with low prosocial behavior, peer acceptance (Card et al., 2008), resilience (Gomez-Ortiz et al., 2015), low self-esteem (Donnellan et al., 2005; Teng et al., 2015), and is associated with peer rejection (Morrow et al., 2008) and mental health problems, such as depression (Messer & Gross, 1994; Morrow et al., 2008) and narcissism (Bushman et al., 2009; Du et al., 2022; Kjaervik & Bushman, 2021), as well as drug use (Moore et al., 2008), alcohol consumption (Chermack & Giancola, 1997) and educational failures such as school dropout (Risi et al., 2003). Persistent aggression increases the likelihood of school dropout (Risi et al., 2003). Antisocial tendency during adolescence has been examined for years, particularly due to its connection to major aggressive behaviors and other forms of maladjustment. Antisocial tendencies, as a form of relative maladjustment during adolescence, might have consequences for adulthood, as well as affect the efficacy of parenting styles. The antisocial tendency may be limited during adolescence (Moffitt, 1993, 2018) or extend into adulthood (Steinberg et al., 1994; Steinberg, 2001). Adolescents often experience a decline in self-perception of autonomy and identity (Moffitt, 1993), leading to rebellion against parents (Simmons & Blyth, 1987). Biological changes and entering high school contribute to dissatisfaction with their maturity compared to slightly older peers (Moffitt, 1993). Some adolescents resort to disruptive behaviors to manage these feelings and assert independence from their parents (Erikson, 1968), which may be seen as normative (Moffitt, 1993). A controversial question is whether problems during adolescence contribute to the development of a healthy and independent identity in adulthood compared to experiencing no significant problems during that period. According to the storm-and-stress hypothesis, an expression of maladjustment and problems (e.g., antisocial tendency) could even help adolescents to achieve a healthy independent identity and good adjustment once they become adults (Arnett, 1999; Erikson, 1968). On the opposite side, studies primarily based on community samples suggest that conflict during adolescence is not normative and may be related to maladaptive parent-child relationship patterns (Riquelme et al., 2018; Steinberg, 2001). Additionally, some family studies suggest that personal child traits (e.g., antisocial tendency during adolescence) might affect the efficacy of parenting styles (O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Z. Lin et al., 2023; Reyes et al., 2023; Steinberg et al., 2006). Self-concept signifies a personal representation of oneself and is positively associated with psychosocial adjustment. Self-concept is the evaluative component of self-perceptions, an individual’s construction of his or her personal worth in different interrelated dimensions of self (Ertema et al., 2025; Marsh et al., 1988; Shavelson et al., 1976). Self-concept is positively related to prosocial behavior (Laible et al., 2004), self-esteem, conscientiousness, agreeableness, internal state awareness, and negative with neuroticism (Campbell et al., 1996). Self-concept is also positively associated with social acceptance and scholastic competence and negatively related to socio-emotional behavior (Hotulainen & Lappalainen, 2011). In the same line, emotional-social competence represents other components of psychosocial adjustment. Emotional-social competence is an individual’s ability to identify and manage their emotions, comprehend and empathize with others, harmonious relationships through perspective-taking, and make responsible decisions to resolve problems effectively through cooperation with others (Greenberg et al., 2003). The learning of emotional-social competence is very significant in adolescence because it is a critical period in which emotional habits are formed (Kang et al., 2022). Emotional-social competence plays an important role in the prevention of aggression and depression (Kang et al., 2022) and is positively related to academic achievement (Elias & Haynes, 2008). Research shows that parents significantly influence their child’s aggression levels (Delfini et al., 1976; O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Patterson, 1980; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020). They can enhance or impair a child’s self-concept and ability to perceive themselves positively (F. Chen et al., 2024; Fuentes et al., 2022; Martinez et al., 2021). Parents also contribute to the development of emotional-social competencies in children (Y. Tang et al., 2023). This study examines parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, or neglectful) and their positive or negative relationship with aggression, self-concept, and emotional-social competence in a rapidly changing culture like China. Additionally, this study also tests possible variations in the relationship between parenting and child psychosocial adjustment depending on antisocial tendency during adolescence (low vs. high), sex (females vs. males), and Gen-Z groups (young adult vs. adolescent cohorts). Participants and Procedure The participants were 1,417 children from a large metropolitan urban area in southwest China, with about 4.6 million inhabitants. Participants were Gen Z individuals born between 2003 and 2008, with an age range from 16 to 21 years (M = 18.41, SD = 1.48), comprising 735 females (51.9%) and 682 males (48.1%). The participants were from two cohorts: 736 (51.9%) were from young adult cohort born between 2003 and 2005, with 53.5% females, ranging from 19 to 21 years old (M = 19.63, SD = 0.74), and 681 (48.1%) were from the adolescent cohort born between 2006 and 2008, with 50.1% females, ranging from 16 to 18 years old (M = 17.10, SD = 0.79). A priori power analysis indicated that a minimum sample of 1,200 participants was required to identify a low effect size, f = 0.12. The sensitivity power analysis showed that with the study sample size of N = 1,417 (α = β = .05), statistically significant differences with a slightly lower small effect size (f = 0.11) can be detected in the main effects among the four parenting styles (Cohen, 1977; J. F. Garcia et al., 2008). The sample was collected during the first three months of 2024. All participants a) were Chinese, as were their parents and four grandparents, b) did not have any mental disorders, and c) signed the informed consent form, which, in the case of adolescents, was also signed by their parents (Arrojo et al., 2024). This study follows ethic principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The directors of the high schools invited to participate were contacted, and if they declined the invitation the next high school on the list was contacted until the required sample size was reached. Young adults were recruited from university students. All participants completed an online questionnaire that included items for all study variables, and all items were compulsory. The anonymity of the responses was guaranteed. To ensure data safety, identifiers of participants and investigation data were collected in separate files, sensitive data archives were protected, and passwords for web directories were stored in an encryption-protected system (Alcaide et al., 2025; Climent-Galarza et al., 2022). The questionnaires included in the online survey were checked for suspicious response patterns, such as implausible inconsistencies between answers to positively and negatively worded items (J. F. Garcia et al., 2011; Tomás & Oliver, 2004). Measures were administered in Chinese language, following forward- and back-translation and meetings to resolve any item-by-item ambiguities in linguistic or semantic content (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011; Erkut, 2010). This approach helps prevent errors during translation and ensures conceptual equivalence (Brislin, 1970; F. Chen et al., 2020; F. Garcia et al., 2013; Gomez & Suhaimi, 2015). Measures Parenting Styles Parental warmth was assessed with the 20 items of Warmth/Affection Scale (WAS) of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) (F. Chen et al., 2024; Rohner et al., 1978a). The WAS assesses the extent to which the child perceives parental love and involvement in his or her life (e.g., “Make me feel proud when I do well”). Cronbach’s alpha value was .921. Parental strictness was assessed with the 13 items of the Parental Control Scale (PCS) of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ) (Rohner et al., 1978a). The PCS assesses how children perceive their parents’ behavior as strict and controlling towards their own behavior (e.g., “Want to control whatever I do”). Cronbach’s alpha value was .921. Adolescents answered the items of the scales written in the present tense, while young adults responded to items in the past tense. Both WAS and PCS provide reliable measures in young adults (Ali et al., 2015). Participants answered for both parental measures on a 4-point scale (1 = almost never true, 4 = almost always true). Higher scores on WAS and PCS represent higher parental warmth and parental strictness. The two scales show good psychometric properties and has been used in many countries (Khaleque & Rohner, 2002, 2012), such as Australia, the United States (Gomez & Rohner, 2011), Spain (O. F. Garcia et al., 2018), Italy (Senese et al., 2016) or China (Deater-Deckard et al., 2011). The two scales also show the same factorial structure across cultures (Khaleque & Ali, 2017). Parenting styles were defined using the median dichotomization procedure, which involves splitting the sample into categories of parental warmth and strictness based on the 50th percentile (median), while controlling for sex and age to analyze both parenting variables simultaneously (Gimenez-Serrano et al., 2022; Lamborn et al., 1991; Martinez et al., 2012). Authoritarian families scored below the 50th percentile on warmth but above it on strictness. Authoritative families scored above the 50th percentile on both dimensions. Indulgent families scored above the 50th percentile in warmth but below it in strictness. Finally, neglectful families scored below the 50th percentile on both dimensions. Antisocial Tendency Antisocial tendency during adolescence was assessed with the 13 items of the Youth Deviance Scale (Gold, 1970). This measure includes school misconduct (i.e., the rate of recurrence of behaviors such as cheating, copying homework, and tardiness) (e.g., “Misrepresenting a classmate in homework or assignments on purpose) and delinquency (i.e., the frequency of behaviors such as carrying a weapon, stealing, and getting into trouble with the police) (e.g., “Spoiling or damaging trees or plants in public spaces). Participants responded on a 3-point scale (1 = never, 3 = two or more). The low antisocial tendency condition consisted of participants who scored below the median (50th percentile), whereas the high antisocial tendency condition included those who scored above the median (50th percentile). The medians were calculated controlling for sex and age. Higher scores on this scale indicate a greater antisocial tendency during adolescence in terms of school misconduct and delinquency. The Cronbach’s alpha value was .863, indicating good reliability. This scale has been utilized in various parenting studies evaluating antisocial tendency in adolescents (F. Garcia & Gracia, 2009; O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Lamborn et al., 1991), including China (C. S. Chen et al., 1998). The scale has good reliability indices (C. S. Chen et al., 1998; F. Garcia & Gracia, 2009; O. F. Garcia et al., 2021). Aggression Aggression was assessed using the six items of the Hostility/Aggression Scale from the Personality Assessment Questionnaire (Rohner, 1978b). This scale evaluates acts intended to harm something or someone (another person or oneself), which may manifest as verbal (e.g., arguing, humiliation, insults) or physical (e.g., hitting, kicking, scratching) behaviors (e.g., “I get so mad I throw or break things”). Participants responded on a 4-point scale (1 = almost never true, 4 = almost always true). Higher scores on this scale represent higher aggression. Cronbach’s alpha value was .686. This scale has been widely used in parenting studies across the world to assess child aggression in both adolescents and adults (Ali et al., 2019; Khaleque & Ali, 2017), including China (Li, 2014). The scale has good psychometric properties (Rohner, 1978b). Self-concept Self-concept was assessed using five dimensions (i.e., academic, social, emotional, family, and physical), with each dimension measured by six items from the AF5 Multidimensional Self-concept Scale (F. Chen et al., 2020; F. Garcia & Musitu, 1999). The academic subscale evaluates one’s perception of performance as a student or worker (e.g., “I am a hard worker [good student]”). The social subscale assesses one’s perceived performance in interpersonal relationships (e.g., “It is difficult for me to make friends”, reversed item). The emotional subscale evaluates one’s perception of their emotional state and performance in response to specific situations (e.g., “When an older person says something to me, I become very nervous”, reversed item). The family subscale assesses one’s perceived contribution, integration, and involvement in the family (e.g., “My family would help me with any type of problem”). The physical subscale evaluates one’s perception of appearance and physical condition (e.g., “I like the way I look”). Participants responded on a 99-point scale (1 = complete disagreement, 99 = complete agreement). Higher scores on AF5 subscales represent a higher self-concept. Cronbach’s alpha values for the AF5 subscales were as follows: academic, .873, social, .774, emotional, .728, family, .749, and physical, .666. The AF5 questionnaire has been widely used to assess self-concept in adolescents (O. F. Garcia & Serra, 2019; Queiroz et al., 2020) and adults (Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023; Villarejo et al., 2020). Exploratory (F. Garcia & Musitu, 1999) and confirmatory analyses (Murgui et al., 2012; Tomás & Oliver, 2004) have tested the five-dimensional structure in different cultural contexts, such as Spain (Murgui et al., 2012), Portugal (J. F. Garcia et al., 2006), Brazil (F. Garcia et al., 2018), Chile (J. F. Garcia et al., 2011), Mexico (Ertema et al., 2025), United States (F. Garcia et al., 2013), and China (F. Chen et al., 2020). Emotional-social Competence Emotional-social competence was assessed using the Psychosocial Maturity Questionnaire (Greenberger et al., 1975), which includes the eight-item nervousness scale and the eight-item social competence scale. The nervousness scale evaluates emotional stability related to anxiety and tension (e.g., “I rarely feel relaxed”). The social competence scale evaluates the ability to develop positive interpersonal relationships with peers and adults (e.g., “I am persistent, tenacious; I finish what I start”). Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 5 = agree strongly). Higher scores on the nervousness scale indicate greater anxiety, while higher scores on the social competence scale reflect better social skills. Cronbach’s alpha values for these subscales were .724 for nervousness and .824 for social competence. This questionnaire is widely used in parenting literature to assess children’s emotional and social competencies in Eastern (Palacios et al., 2022; Villarejo et al., 2024) and Asian Societies (Mantzicopoulos & Oh-Hwang, 1998; W. Wang, 1991; Xia, 2025) and has shown good psychometric properties (O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Gimenez-Serrano et al., 2022; Greenberger et al., 1975). Data Analysis A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with a 4 × 2 × 2 × 2 design was conducted to examine aggression, self-concept (including academic, social, emotional, family, and physical aspects), and emotional-social competence (measured through nervousness and social competence). The independent variables were parenting styles (authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful), antisocial tendency during adolescence (low vs. high), sex (females vs. males), and age groups (young adult vs. adolescent cohorts). Following the MANOVA, a univariate F-analysis was applied to the sources of variation that were statistically significant. Additionally, Bonferroni post-hoc tests were performed on these significant sources to identify differences across all possible pairs of means. Parenting Style Groups and Antisocial Tendency groups Participants were distributed based on parenting styles: 371 (26.2%) authoritative, 312 (22.0%) indulgent, 356 (25.1%) authoritarian, and 378 (26.7%) neglectful. Authoritative (M = 68.95, SD = 5.30) and indulgent parenting (M = 68.67, SD = 5.28) scored higher on warmth than authoritarian (M = 52.47, SD = 8.26) and neglectful parenting (M = 52.62, SD = 6.93). Additionally, authoritative (M = 38.07, SD = 2.41) and authoritarian parenting (M = 38.75, SD = 3.32) obtained higher scores on strictness than indulgent (M = 31.46, SD = 3.08) and neglectful parenting (M = 30.89, SD = 3.56). Participants were also categorized according to antisocial tendency, with 720 (50.8%) in the low antisocial tendency condition and 697 (49.2%) in the high antisocial tendency condition. The low antisocial tendency condition had a lower antisocial tendency (M = 1.01, SD = 0.30) than the high antisocial tendency condition (M = 1.32, SD = 0.34). Multivariate Analyses Multivariate analyses found statistically significant differences in the main effects of parenting style, Λ = .734, F(24, 3997.2) = 18.75, p < .001, antisocial tendency, Λ = .928, F(8, 1378.0) = 13.29, p < .001, sex, Λ = .939, F(8, 1378.0) = 11.11, p < .001, and age, Λ = .976, F(8, 1378.0) = 4.16, p < .001. Significant interaction effects were also found for parenting style by age, Λ = .971, F(24, 3997.2) = 1.71, p < .05, and parenting style by sex and age, Λ = .966, F(24, 3997.2) = 2.00, p < .01 (see Table 1). Table 1 Multivariate Factorial MANOVA 4 × 2 × 2 × 2 for Aggression, Self-concept (academic, social, emotional, family, and physical), and Emotional-social Competence (nervousness and social competence)   Main Effects Parenting Differences Children raised in warm homes (i.e., authoritative and indulgent) showed less aggression than their peers from households characterized by low warmth (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful), p < .001 (see Table 2). Similarly, children from authoritative and indulgent families had higher academic, social, emotional, family, and physical self-concept than those raised by parents characterized by low warmth, p < .001. Additionally, children from both authoritative and indulgent homes showed better emotional-social competence (lower nervousness and higher social competence) compared to those raised by authoritarian and neglectful parents, p < .001. Although, in general, differences were found between warmth and non-warmth parenting, differences in family self-concept and social competence were identified among those styles associated with low scores (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). Children from authoritarian families scored more negatively in family self-concept than their peers from neglectful families, while the most negative scores in social competence were associated with the neglectful style. Table 2 Descriptive Statistics, Mean, and Standard Deviations (in parenthesis), for Parenting Style and Univariate F-values for Aggression, Self-concept (academic, social, emotional, family, and physical), and Emotional-social competence (nervousness and social competence)   ***p < .001; 1 > 2 > 3. Antisocial Tendency, Sex and Age-related Differences Children with antisocial tendency had higher levels of aggression and nervousness, but lower academic, social, emotional, and family self-concept than their peers without antisocial tendency, p < .05 (see Table 3). Sex-related differences indicated that males had higher levels of aggression and both emotional and physical self-concept than females. Conversely, females scored higher on social and family self-concept as well as on nervousness than males, p < .05. Age-related differences showed that adolescent cohort obtained higher levels of social self-concept and lower physical self-concept than young adult cohort, p < .05. Table 3 Descriptive Statistics, Mean and Standard Deviations (in parenthesis), for Antisocial Tendency, Sex and Age, and Univariate F-values for Aggression, Self-concept (academic, social, emotional, family, and physical), and Emotional-social Competence (nervousness and social competence)   *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. Interaction Effects A significant interaction between parenting styles, age, and sex was found for aggression, F(3, 1385) = 4.58, p < .01 (see Figure 1, panels a and b). Sex-differentiated profiles for parenting styles were observed in aggression, males generally reported higher levels than females according to the main effects. Additionally, warm parenting styles were associated with lower child aggression. For females for both young adult and adolescent cohorts, those with authoritarian parents had the highest levels of aggression, whereas daughters with indulgent parents reported the lowest levels. For the young adult cohort, only daughters from non-warm families (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful) scored high in aggression, while young adult daughters with authoritative and indulgent parents reported similar and lower levels of aggression. In contrast, within the adolescent cohort, daughters with authoritative parents scored more negatively than those from neglectful families (see Figure 1, panel a). Males reported the highest levels of aggression in both young adult and adolescent cohorts when raised by non-warm parents (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). In contrast, those with warm parents (i.e., indulgent and authoritative) showed the lowest levels of aggression. While sons with authoritarian parents reported the highest aggression within young adult cohort, their counterparts from neglectful parents reported the greatest aggression in the adolescent cohort. Similarly, sons from indulgent parents reported the lowest aggression in the young adult cohort, whereas the lowest aggression in the adult cohort was found among sons from authoritative parents (see Figure 1, panel b). Figure 1 Interaction between Age, Parenting Style, and Sex for Aggression, (a) Females, and (b) Males.   A significant interaction between parenting style by age was also found in self-concept in the academic, F(3, 1385) = 3.01, p < .05, emotional, F(3, 1385) = 3.91, p < .01, and family, F(3, 1385) = 3.91, p < 0.01, dimensions (Figure 2 panels a, b, and c). (i) Cohort-differentiated profiles were observed in academic self-concept. Overall, children from homes characterized by high warmth (i.e., indulgent and authoritative) tended to report better academic self-concept compared to those from homes low in warmth (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). Among the warm parenting styles, both indulgent and authoritative parenting were associated with similarly high academic self-concept scores in the young adult cohort. By contrast, within the adolescent cohort, authoritative parenting was related to higher academic self-concept scores than indulgent parenting. Conversely, both authoritarian and neglectful parenting were associated with poor academic self-concept; however, this pattern was slightly less pronounced in the young adult cohort than in the adolescent cohort. The worst academic self-concept in the young adult cohort corresponded to neglectful parenting, whereas in the adolescent cohort, the lowest scores were associated with authoritarian parenting (Figure 2, panel a). (ii) A similar profile related to benefits of warm parenting was also found in emotional self-concept. Children with indulgent parents consistently reported the highest emotional self-concept, followed closely by those from authoritative homes. Conversely, in parenting styles characterized by low warmth, children from authoritarian households had the lowest emotional self-concept, followed by those from neglectful homes. Interaction effects showed that the degree of difference in this common profile is less pronounced in the young adult cohort than in the adolescent cohort (Figure 2, panel b). (iii) Again, in family self-concept, children from warm homes (i.e., authoritative and indulgent) always had a better family self-concept than their counterparts from non-warm households (i.e., authoritarian and neglectful). In parenting styles characterized by warmth, indulgent parenting was associated with higher family self-concept than authoritative parenting within the young adult cohort; however, family self-concept scores related to authoritative and indulgent parenting were both positive and similar within the adolescent cohort. In parenting styles without warmth, children from authoritarian homes always had the lowest emotional self-concept, followed by those with neglectful parents. However, the differences were smaller in young adult cohort than in adolescent cohort (Figure 2, panel c). Figure 2 Interactions between Age and Parenting Style for (a) Academic, (b) Emotional, and (c) Family Self-concept.   This study aimed to investigate the role of parents in promoting or hindering psychosocial adjustment in children. It focuses on aggression, five dimensions of self-concept, and emotional-social competence depending on parenting styles, antisocial tendency during adolescence, sex, and age. The study analyzes two cohorts of Chinese Gen Z, young adults (born between 2003 and 2005) and adolescents (born between 2006 and 2008), tested in the first quarter of 2024. The influence of parents was assessed using a two-dimensional theoretical model (warmth and strictness) which includes four parenting styles: authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful. Contrary to classical parenting literature, this study found that authoritarian parents not only fail to protect against aggressiveness in their children but may elevate the risk of such behaviors. This finding is relatively unexpected, given that traditional parenting theories have long suggested that authoritarian parenting is related to benefits for preventing external problematic behaviors as violence (Baumrind, 1991; Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Lamborn et al., 1991; Simons & Sutton, 2021). This assumption has also been supported by perspectives in ethnic minorities in the United States (Baumrind, 1972; Chao, 1994, 2001; Deater-Deckard et al., 1996) and hierarchical collectivistic cultures, including China (W. Chen, 2015; Ho, 1986; Leung et al., 1998; Y. Li et al., 2010). Self-concept findings indicate that children raised by authoritarian parents reported low scores across all dimensions—academic, social, emotional, family, and physical. The family self-concept of children from authoritarian homes was even lower than that of their peers from neglectful households. Furthermore, in terms of emotional-social competence, these children experienced heightened nervousness and reduced social skills, performing worse than their peers raised in neglectful homes. Although some previous research supported that authoritarian parenting in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was related to benefits such as academic achievement, less depression, and family cohesion (W. Chen, 2015; Ho, 1986; Leung et al., 1998; Y. Li et al., 2010), present findings identify serious damages related to authoritarian parenting, at least on two Gen Z cohorts. The classic two-dimensional model (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; F. Garcia & Gracia, 2009; Lamborn et al., 1991; Maccoby & Martin, 1983) provides valuable insights into the emerging trends in the relationship between parenting styles and children’s aggression. The present study shows that warm parenting acts as a protective factor, while non-warm parenting serves as a risk factor. This contradicts classical parenting literature, which posits that strict parenting is protective and non-strict parenting is risky (Baumrind, 1983; Lewis, 1981; Steinberg et al., 1991; Steinberg et al., 1994). Children raised by warm parents—those identified as authoritative (high warmth and high strictness) and indulgent (high warmth and low strictness)—reported the lowest levels of aggression. This trend extends to other psychosocial adjustment criteria; children raised in warm environments had the highest levels of self-concept and showed better emotional-social competence, characterized by low nervousness and high social skills. The results of this study align, at least in part, with emerging research mainly conducted in Europe that questions classical views about the limitations of indulgent parenting. These emergent studies indicate that warmth alone could be sufficient for reducing aggression levels (Alcaide et al., 2023), decreasing child-to-parent violence (Gamez-Guadix et al., 2012; Suarez-Relinque et al., 2019), lowering proactive school violence (Moreno-Ruiz et al., 2018), diminishing delinquency (Climent-Galarza et al., 2022), reducing drug use (O. F. Garcia et al., 2020; Villarejo et al., 2024) and achieving conformity to social standards (Alcaide et al., 2025). Additionally, the present study conducted in a non-Western society (i.e., China) has also shown that high warmth is crucial for fostering optimal levels of self-concept and emotional-social competence (Fuentes et al., 2015; Gimenez-Serrano et al., 2022; Martinez-Escudero et al., 2023; Palacios et al., 2022; Villarejo et al., 2024). It is possible that the rapid acceleration of social change, described as experiencing more changes in a short period of time (e.g., a decade) than in a much broader timeframe (e.g., a century), may partly explain the radical shifts observed in the Chinese society, describing the transition of authoritarian parenting from a protective factor to a risk factor. It appears that children raised in Gen Z by authoritarian parents have serious psychosocial maladjustment, unlike those from previous generations. Although the findings of this study do not differentiate between authoritative and indulgent parenting styles regarding their effectiveness in promoting child psychosocial adjustment—at least in terms of main effects—interaction effects reveal significant insights, particularly concerning sex and age. Overall, a relatively consistent pattern was observed between parenting styles and aggression; however, nuances emerged among daughters and sons in the two Gen Z cohorts. Daughters benefit particularly from the combination of high warmth and low strictness (i.e., the indulgent style). These benefits are evident not only in the young adult cohort, who are pursuing university studies, but also in the adolescent cohort, despite the fact that the latter presumably have lower maturity and is still under the supervision of their parents and teachers. For sons, indulgent parenting is beneficial similarly to daughters, but only within the young adult cohort. In the adolescent cohort, authoritative parenting was associated with less aggression than indulgent parenting. Interestingly, warm parenting (i.e., both authoritative and indulgent styles) is related to a mixed profile of benefits and costs within the adolescent cohort, with differences particularly pronounced among females. While adolescent sons benefit more from authoritative parenting, for adolescent daughters indulgent parenting acts as a protective factor, whereas authoritative parenting is a risk factor similarly negative as authoritarian parenting, which is associated with the highest aggression levels. These findings about parenting styles and aggression may be partly attributed to the greater psychosocial maturity of the young adult cohort compared to the adolescent cohort (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000), suggesting that young adults may not benefit from the strict component once parental socialization ends. Additionally, results revealed that females tend to score lower in aggression than males, substantiating previous evidence indicating more externalized problems such as aggression among males (Björkqvist & Österman, 2018; Martino et al., 2008). Adolescent females mature psychosocially earlier than males (Cauffman & Steinberg, 2000) and may not gain from strictness. This partially might explain that the strict component of authoritative parenting may be necessary for adolescent sons, but not for adolescent daughters, who appear to benefit in terms of low aggression only with indulgent parenting. Other important findings included the interaction between parenting style and age on self-concept, particularly in the academic, emotional, and family dimensions. Overall, children from warm homes (i.e., authoritative and indulgent) tended to report the highest levels of self-concept, while children from authoritarian homes scored the lowest, even lower than their peers from neglectful homes. The academic self-concept not only reflects self-perceptions of being a good student but is also associated with academic outcomes, such as grade point average (Preckel et al., 2013; Reynolds, 1988). Within the young adult cohort, parental warmth was beneficial for academic self-concept, while parental strictness was unnecessary; young adults with indulgent parents did not differ in their academic self-concept from young adults with authoritative parents. In contrast, a different pattern was found within the adolescent cohort: strictness combined with parental warmth was necessary to achieve the highest academic self-concept, as authoritative parenting was associated with more positive scores than indulgent parenting. This may be partly because university students generally possess greater abilities and capacities than their high school peers (Mañez et al., 2024; Veiga et al., 2021; Wentzel et al., 2019). The Gen Z young adult cohort seems to experience the most positive outcomes regarding self-concept when their parents adopt a warm approach, without significant benefits linked to strictness, likely because they are no longer under their parents’ supervision and care, indicating that parental socialization has concluded. By contrast, high school can be particularly stressful, especially within the competitive and demanding Chinese education system, where Gen Z adolescents face significant pressure by parents and teachers to secure limited access to university degrees (Liu et al., 2021). This adolescent cohort may also require parental warmth alongside supervision and demands. Additionally, contrary to classical assertions regarding the benefits of Chinese authoritarian parenting for academic success (Chao, 2001; Leung et al., 1998), the present findings caution that parental strictness without warmth (i.e., authoritarian parenting) could negatively impact academic self-concept in both adolescent and young adult cohorts. A relatively different profile compared to what was observed in academic self-concept was found in emotional self-concept, and even more remarkably in family self-concept. In terms of emotional self-concept, both the young adult and adolescent cohorts showed that high parental warmth was associated with greater emotional self-concept than low parental warmth; the highest scores were related to indulgent parenting, while the lowest scores were associated with authoritarian parenting, with authoritative and neglectful styles occupying a middle position. Furthermore, differences in emotional self-concept related to parenting styles were less pronounced in the young adult cohort than in the adolescent generation, suggesting that family influence could be more critical during adolescence and play a key role in self-regulation during this more difficult developmental stage. The present study also clarifies how parenting can either harm or enhance family self-concept. Previous research has shown that a child’s perception of their involvement in the home (i.e., family self-concept) is related to positive adjustment, such as reduced antisocial behavior, emotional instability, psychological distress, and depressive symptoms (Ertema et al., 2025; Martinez et al., 2021). Only indulgent parenting was consistently associated with the highest scores on family self-concept in both the young adult and adolescent cohorts. The findings indicate that, when comparing families based on warmth, parental strictness even when combined with warmth (i.e., the authoritative style) was detrimental within the young adult cohort (indulgent parenting was related to more positive scores than authoritative parenting), but not for the adolescent cohort (where no significant differences were found between indulgent and authoritative parenting). These results suggest that warmth is beneficial for feeling loved and valued by the family; however, unlike the adolescent cohort, parental strictness that characterized authoritative parenting could be particularly detrimental in the young adult cohort, probably due in part to the consequences of no longer being under parental supervision and care, given that socialization time has concluded. Moreover, the results further indicate that authoritarian parenting was associated with significant problems related to family functioning; individuals from both adolescent and young adult cohorts raised by authoritarian parents reported even lower levels of family self-concept than their peers from neglectful homes, particularly within the adolescent cohort. These findings contradict traditional views asserting that children from authoritarian homes in cultures such as China feel like valued members of their families (Ho, 1986). Extending previous evidence, results from the present study showed that children with an antisocial tendency during adolescence, in comparison to their peers without antisocial tendency, reported higher levels of aggression (Coie & Dodge, 1998), lower levels of academic, social, emotional, and family self-concept (O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020; van de Groep et al., 2023; Vázquez-Figueiredo et al., 2013) and higher levels of nervousness (O. F. Garcia et al., 2021). Results from this study have important consequences for the contemporary society. Based on a community sample of Chinese Gen Z comparing two cohorts, adolescent and young adults, this study found that antisocial tendency during adolescence was related to maladjustment, regardless of age (the interaction effect between antisocial tendencies and age was not statistically significant). Therefore, the findings contradict the notion that adolescent antisocial behavior is relatively normative and beneficial to a successful transition from adolescence to adulthood, as suggested by the classic “storm and stress” hypothesis (Arnett, 1999; Blos, 1967; Erikson, 1968). Instead, present findings align with previous research indicating that problems during adolescence do not contribute positively to the development of a healthy adult identity (O. F. Garcia et al., 2021; Steinberg, 2001), thereby extending evidence to the less-studied context of Chinese society. Furthermore, the results indicated that the effectiveness of parenting style did not change based on antisocial tendency during adolescence (the interaction was not significant). These results partially confirm previous studies in which no greater effectiveness of a parenting style was observed based on the child individual characteristics (Reyes et al., 2023; Steinberg et al., 2006). The present results have significant theoretical and practical implications, including for educational and mental health policies. Despite significant cultural variations between Western (e.g., the United States and Europe) and Eastern societies, the two-dimensional theoretical model of four parenting styles (i.e., authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful) can be extended to Chinese families to consistently identify relationships between parenting styles and child psychosocial adjustment—although there might also be some generational nuances in this relationship. Families, through parental socialization, can be protective or risk factors for children. Public policies should caution against the risks associated with authoritarian parenting (i.e., strictness without warmth), not only due to its highly detrimental effects on children’s health but also because it could be highly harmful to academic adjustment, even though the authoritarian style has historically been associated with potential benefits, particularly in terms of academic success. Instead, public policies should promote family interventions that foster affection, involvement, trust, and open dialogue between parents and children. Importantly, even children with adjustment problems —who typically report more difficulties than their peers—can greatly benefit from a warm-based parenting style. Interventions aimed at parents of adolescents with antisocial tendency should focus on ensuring that children feel loved and protected, using dialogue and reasoning to address their maladjustment. Additionally, consistent with previous research, this study identified differences in child adjustment based on sex and age. Males had higher levels of emotional and physical self-concept, as well as aggression, compared to females (Alcaide et al., 2023; F. Chen et al., 2024; DeBlassie & Healy, 1970; Perez-Gramaje et al., 2020; Villarejo et al., 2024). In contrast, females had higher levels of social and family self-concept and greater nervousness than males (Bahrami & Yousefi, 2011; Palacios et al., 2022; Rosenberg & Simmons, 1975; Stumpf et al., 2015). Furthermore, adolescent cohort had higher levels of social self-concept and lower levels of physical self-concept than young adults (F. Chen et al., 2024). The present study has several limitations. It was conducted with an urban sample from a specific region in China; thus, its findings may not be applicable to extensive rural areas within the country. In the transformations occurring within Chinese society, there appears to be a decrease in collectivism—though it remains significant in some areas, particularly in the emphasis on academic success—and a shift towards more egalitarian relationships (Bian et al., 2022). However, it is possible that these social transformations have a greater impact on urban areas compared to rural ones in China. Therefore, future studies should also examine whether rural children benefit from warm parenting (i.e., authoritative and indulgent) or if more traditional and hierarchical parent-child relationships lead them to benefit from an authoritarian style (i.e., strictness without warmth). Likewise, future studies with Chinese families (i.e., authoritative, indulgent, authoritarian, and neglectful) should continue exploring the relationship between parenting and child adjustment depending on other sociocultural factors such as the parents’ socioeconomic status or family structure. The study explores the relationship between parenting styles with aggression, self-concept, and emotional-social competence during the parental socialization process (i.e., within the adolescent cohort) and after its conclusion (i.e., within the young adult cohort), using a cross-sectional design rather than a longitudinal approach. Since this is not an experimental study, causal relationships cannot be established between parenting styles and child aggression, nor can they be determined between the antisocial tendency during adolescence and the aggression experienced in adulthood. Future longitudinal studies should add evidence by analyzing over time the relationship between parenting and child psychosocial adjustment, not only during adolescence but especially when the child reaches the adult age and is no longer under the supervision and care of their parents. Conclusion Parents play a crucial role in their children’s psychosocial adjustment by preventing deviant behaviors and influencing self-concept and emotional-social competence. Some previous research in collectivistic cultures such as China suggested that authoritarian parenting (i.e., strictness without warmth) was beneficial for achieving good adjustment, especially in school (Ho, 1986). However, the present study shows that in contemporary Chinese culture, authoritarian parenting is a risk factor for aggression, and problems of self-concept —including academically— and emotional-social competence. In contrast, parenting styles characterized by warmth (i.e., authoritative and indulgent) were associated with low aggression, high self-concept and social-emotional competence. When analyzing parenting and adjustment by sex and Gen Z cohorts, nuances emerge that require further research to clarify the socialization consequences for sons and daughters. The adolescent cohort deserves special attention. In terms of academic self-concept, Chinese adolescent sons benefit more from the authoritative style like their European-American peers from USA (Lamborn et al., 1991), while daughters benefit from the indulgent style, similar to their counterparts from Europe (F. Garcia & Gracia, 2009). Additionally, the authoritative style supports academic success in terms of academic self-concept among Chinese adolescents, in line with findings from European-American families of USA (Steinberg et al., 1994), while indulgent parenting is particularly effective for emotional and family self-concept in Chinese adolescents, consistent with recent evidence from Europe (F. Garcia et al., 2019). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Alcaide, M., Garcia, O. F., Chen, F., & Garcia, F. (2025). Raising generation Z children in China: Parenting styles and psychosocial adjustment. Psychosocial Intervention 34(2), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a9 Funding: The research reported in this study has been supported by grant CIAICO/2021/252 (Conselleria for Innovation, Universities, Science and Digital Society, Generalitat Valenciana). Additionally, it has been partially supported by grants FPU20/06307 (Ministry of Universities, Government of Spain), and BEFPI/2017/058, which provided funding for a research stay at Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom (Generalitat Valenciana and European Social Fund). The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. |

Cite this article as: Alcaide, M., Garcia, O. F., Chen, F., & Garcia, F. (2025). Raising Generation Z Children in China: Parenting Styles and Psychosocial Adjustment. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(2), 103 - 115. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a9

Correspondence: oscar.f.garcia@uv.es (O. F. Garcia).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS