Legal Consciousness: A Systematic Review of its Conceptualization and Measurement Methods

[La conciencia jurídica: una revisión sistemática de su conceptualización y de los métodos de medición]

Filip Horák1, David Lacko2, and Adam Klocek2

1Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic; 2Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a2

Received 7 September 2019, Accepted 25 April 2020

Abstract

This article reports on a conducted systematic review focused on conceptualization and measurement methods of legal consciousness, which can be understood as the equivalent for the legitimacy of law. A systematic search identified 2,054 articles, resulting in the inclusion of 156 relevant articles after two phases of the screening process. Articles analyzed lacked a clear conceptualization of a legal consciousness construct and validated methods of its measurement with satisfactory quality. A considerable room for improvement was found for both conceptualization and measurement methods of legal consciousness. This review identifies six separate components of legal consciousness (general knowledge, skills, specific knowledge, attitudes, trust, and identity) and offers a unifying and comprehensive definition of legal consciousness based on those components. Using descriptive characteristics and inference statistics, main methodological weaknesses of selected articles were discussed and a set of criteria for optimal measurement method of legal consciousness was introduced.

Resumen

Este artículo versa sobre la revisión sistemática de los métodos de conceptualización y medición de la conciencia jurídica, que puede entenderse como el equivalente de la legitimidad del derecho. La búsqueda sistemática identificó 2,054 artículos, que dio lugar a la inclusión de 156 artículos relevantes después de dos fases en el proceso de selección. Los artículos analizados carecían de una conceptualización clara del constructo de conciencia jurídica y de métodos validados de medición de suficiente calidad. Se vio que había bastantes posibilidades de mejorar tanto la conceptualización como los métodos de medición de la conciencia jurídica. Esta revisión encuentra seis componentes distintos de la conciencia jurídica (conocimiento general, habilidades, conocimiento específico, actitudes, confianza e identidad) y ofrece una definición unificadora e integral de la conciencia jurídica basada en esos componentes. Utilizando las características descriptivas y estadística inferencial se abordan los principales fallos metodológicos de los artículos seleccionados y se propone una serie de criterios de un método óptimo de medición de la conciencia jurídica.

Palabras clave

Conciencia jurídica, Conocimiento jurídico, Conceptualización, Revisión sistemática, Legitimidad legal

Keywords

Legal consciousness, Legal knowledge, Conceptualization, Systematic review, Legitimacy

Cite this article as: Horák, F., Lacko, D., & Klocek, A. (2021). Legal Consciousness: A Systematic Review of its Conceptualization and Measurement Methods1. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 31(1), 9 - 34. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a2

david.lacko@mail.muni.cz Correspondence: david.lacko@mail.muni.cz (D. Lacko).

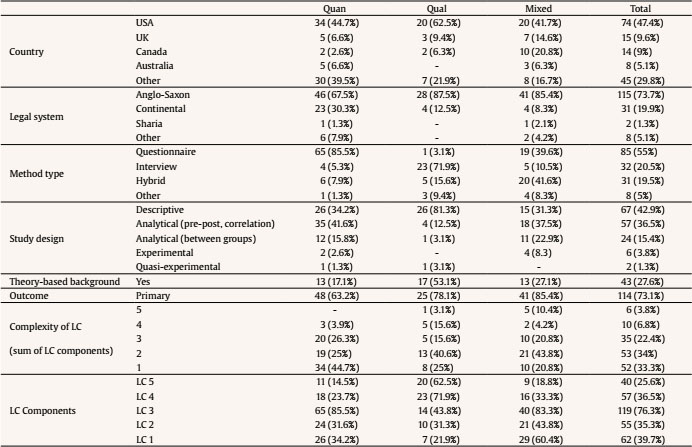

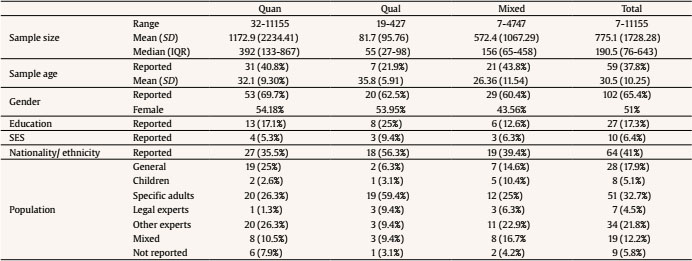

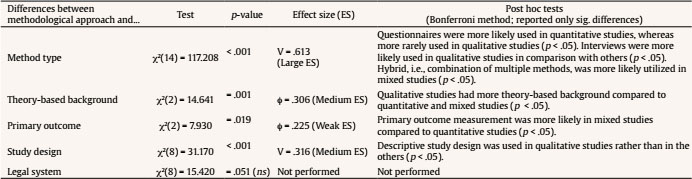

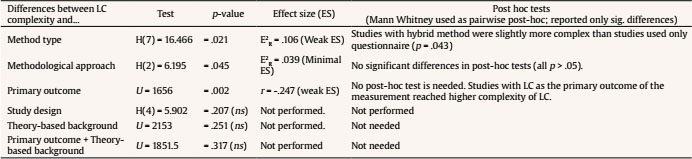

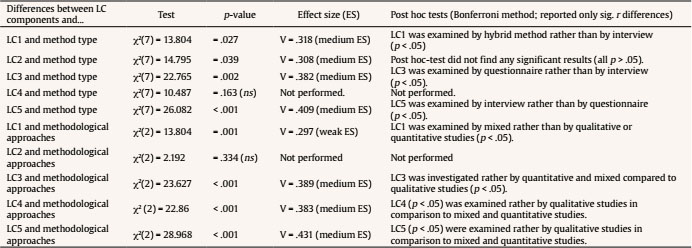

The aim of this article is to conduct a systematic review of articles on both the conceptualization and the measurement possibilities of legal consciousness (hereinafter LC). There are two main goals of this review: the unification of the so far highly diverse terminology and the exploration of recent measurement methods in the field. We argue that further development of LC research field is of crucial importance in current legal science, because LC itself can be understood and explored as one of the core elements of the legitimacy of any legal system (Jennes & Calavita, 2018; Young, 2014). Generally, two different ways of accessing legitimacy of law can be distinguished. First, legitimate law should be “justifiable” (i.e., considered as potentially just and acceptable by legal philosophers and other professionals). Second, legitimate law ought to be also “justified” (i.e., considered as actually just and acceptable by citizens or, in other words, by those who are supposed to follow legal rules; see Horák & Lacko, 2019a). We claim that this second meaning of legitimacy of law is in fact equivalent to LC. This leads us to conclude that, if LC was empirically measurable, it would be also possible to empirically measure the level of legitimacy of law in the population and use these results to offer scientifically based advices and recommendations to both legislative and judicial bodies. Proper scientific analysis of people’s demands for and reactions to legal development could allow a gradual adaptation of law-making and law-interpretation processes according to findings provided by “behavioral legal science” (Berns, 1963; Korobkin & Ulen, 2000; Sunstein et al., 1998; analogously to “behavioral economics”; Thaler, 1980; Kahneman & Tversky, 2000). Through this research, legitimacy as well as the entire functioning of the legal system could be significantly improved, which makes this research justified and desirable (see Horák & Lacko, 2019b). LC research development is nevertheless significantly slowed down by a serious problem, which is inability of researchers to agree upon LC’s universal and broadly accepted definition. We argue that questions of “what exactly we do measure” and “how we should measure it” are yet to be answered and without the answers to these questions LC research cannot fulfil its theoretical, empirical, and practical potential (for a deeper discussion, see Horák & Lacko, 2019b). Therefore, a systematic review focused on conceptualization and measurement of LC seems to be not just helpful but also necessary. This conclusion is even amplified by the fact that there is no previous truly systematic review on LC concept available. Background The term LC itself has gone through a significant development (see Stevens, 2013), which gradually broadened and blurred its meaning. The investigation of LC has a long history, beginning with Ehrlich (1913) and empirical studies investigating the knowledge of specific laws (e.g., Flavier & Chen, 1980). The most frequent term in those studies seemed to be the legal knowledge which was quantitatively measured. Simultaneously, the term LC was used, but it referred to the particular form of consciousness that characterizes the legal profession as a social group, at a particular moment. It contained a vast number of legal rules, arguments, and theories, a great deal of information about the institutional workings of the legal process, and the constellation of ideals and goals current in the profession at a given moment (Kennedy, 1980, p. 23). This rather quantitative approach was considered as too reductionistic and therefore unsatisfactory, which initiated both methodological and conceptual discussions. Current development in this field is therefore characteristic for its clash of diverse approaches. LC has become a more general term which encompassed not only the knowledge of the legal system but also the ways ordinary people think of, talk about, and understand law in their everyday lives (Ewick & Silbey, 1998; Merry, 1990; Nielsen, 2000; Sarat, 1990). The LC concept was thus understood as the integration of terms such as legal knowledge, legal awareness, trust in law, and opinion about law, etc. Furthermore, it expanded its focus from legal experts to the general population. As far as conceptualization of LC is concerned, studies focused primarily on a deeper understanding of specific LC components including their classification. For instance, Ewick and Silbey (1998) presented three schemas of LC, namely “before the law”, “with the law”, and “against the law”. Another example can be Hull’s (2003) argumentation that LC should be understood as a “layered phenomenon”, composed of cognitive and behavioral layers. Generally, this approach, based on more psychological point of view, can be characterized as an individual, static, or micro perspective focusing on LC as a measurable variable (i.e., the state of knowledge, understanding, skills, opinions, or beliefs concerning law at a certain moment) through qualitative research designs based mainly on narrative interviews or ethnographic evidence (e.g., Peterson-Badali & Abramovitch, 1992). A second paradigm, which evolved gradually as a reaction to the former one, used a more sociological approach and analyzed social relations whereby the meanings, opinions, and beliefs concerning law are created and recreated. Therefore, this approach can be described as social or macro perspective (Silbey, 2005) and also rather qualitative, for it gains results primarily through qualitative methods and surveys (Gómez, 2016). The most recent development tried to overcome this cleavage through “second-order legal consciousness research” was based upon the idea of individuals adjusting their LC according to their subjective assumptions of the state of LC within the society (i.e., the people around them). Such an approach, therefore, connects both the individual and the social point of view as well as focuses on the dynamic processes of LC creation and modifications rather than on static LC measurement (Gómez, 2016; Young, 2014). This whole development led to both conceptual and methodological diversity in the LC research field, making the concept of LC rather blurred or terminologically ambivalent. This situation was probably caused by the interdisciplinary nature of LC integrating psychological (Nielsen, 2000), sociological (Hirsh & Lyons, 2010), legal (Klare, 1978; Mandelstam, 1996), pedagogical (Ashar, 2016), and other perspectives. The conceptualization problem is even amplified by the fact that there have not been any attempts to agree upon a universal and broadly accepted definition of this concept yet (Ranasinghe, 2010). Consequently, many of the analyzed studies do not correspond to one another, even though they actually use the same terminology. Most LC researchers discuss the same term but measure completely different constructs. As far as methodology is concerned, again, the enormous diversity ranging from the most rigorous quantitative methods (e.g., experiments) to the variety of qualitative approaches (e.g., in-depth interviews or ethnographic studies) causes the inability of LC researchers to agree upon and validate optimal measurement methods. We believe that the systematic review which is presented in this article can contribute to the solution of all these problems. For the purposes of this review, it is, therefore, necessary to include as many diverse and frequently overlapping terms and constructs corresponding to LC as possible (see searching string). As mentioned before, the meaning and terminological ambivalence of LC was gradually increasing till the current state, where the concept of LC might include numerous constructs, such as “public sense of justice” (Balvig et al., 2015), “knowledge about law” (Swoboda et al., 1978), “legal knowledge” (Riles, 2008), “trust/faith in law” (Messing et al., 2015), “law awareness” (Uzoka, 2016), “legal awareness” (Macura et al., 2011), “sense of justice” (Tapp & Kohlberg, 1971). The majority of scientists usually choose one or more of those constructs and define it differently. However, most of those definitions share some elements with one another. Hence, it is necessary to take all of them into consideration. Systematic Review A systematic review is defined by strict and well described procedures, namely locating, sorting, extracting information from previous sources, and synthetizing the results in one complex study treating eligible sources as individual cases and comparing them with one another (Farrington & Petrosino, 2001). Application of systematic review procedures in the field of law seems to be both possible and desirable (see Baude et al., 2017; Davies & Boruch, 2001). Moreover, the systematic review is useful for the selection of an optimal specific measurement method (Terwee et al., 2012), which is one of the primary goals of this article. Therefore, we used systematic review with elements of integrative and scoping review (see Grant & Booth, 2009; Whittemore & Knafl, 2005; Peters et al., 2015) in order to achieve the aforementioned goals. Due to lack of evidence-based results in this field, no explicit hypotheses were set; therefore, this research shall be understood as exploratory. Database Search Strategy To systematize and synthetize the research of LC, a systematic literature review was conducted, targeting all aforementioned constructs encompassing qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methodological approaches as well as various measurement methods and study designs because the primary goal of the article was to analyze current LC measurement methods. A systematic search was applied within three electronic databases (EBSCO, Web of Science, and SCOPUS) to recognize the vast majority of relevant articles. The search was conducted during December 2017. We used the following searching string2: “legal consciousness” OR “public sense of justice” OR “knowledge about law” OR “legal knowledge” OR “trust in law” OR “faith in law” OR “law awareness” OR “legal awareness” OR “sense of justice”) AND (“quantitative” OR “method” OR “experiment” OR “measurement” OR “assessment” OR “evaluation” OR “screening” OR “classification” OR “level” OR “data” OR “index” OR “scale” OR “questionnaire” OR “interview”) AND (“pupils” OR “adolescents” OR “students” OR “children” OR “youth” OR “young adults” OR “adults” OR “older adults” OR “elderly” OR “seniors”) Screening and Eligibility Criteria The articles found during database search were imported into Mendeley (v1.18) and after removal of duplicates a two-step process of article screening (abstract screening and full text screening) was used in order to remove irrelevant articles. During the first step, screening of titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles were performed. Articles were divided into thirds and examined by the three reviewers independently. Krippendorff’s alpha (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007) within the 100 shared articles demonstrated high satisfactory inter-rater reliability (α = .806). This result showed that there would be only 4.16% chance estimation of alpha being below the usable minimum of .67 if all abstracts were tested and thus all reviewers coded article very similarly. During the second step, all remaining articles were again divided into thirds, swapped between the reviewers, and their full texts were examined. Eligibility (e.g., inclusion/exclusion) criteria used in both screening phases were: a) study contained at least one of the LC-related constructs (i.e., LC component); b) study contained at least any kind of measurement; c) study contained data of real (i.e., not simulated or artificial) population; and d) study language was English. The direct results of the inclusion process (search & screening) are depicted in the PRISMA consort diagram in Figure 1. Primary database search found 2,054 articles. After removing duplicates, 1,836 articles in the abstract screening phase and 300 articles in the full text screening phase were analyzed. Finally, 156 articles were included into the study (Figure 1). Data Extraction and Coding After full text screening, relevant information, e.g., country, legal system, study design, population characteristics or LC components (complete list of variables is depicted in online supplement material 1 - Methodological properties description) from eligible studies were extracted and coded. Methodological properties (MP) were also extracted, categorized and coded. Separated sets of MP categories were created for quantitative (based on Higgins et al., 2011), qualitative (based on Long & Godfrey, 2004), and mixed (based on Fàbregues & Molina-Azorín, 2017; Heyvaert et al., 2013) methodological approaches with modifications in order to be better suited for both the socio-legal research and LC construct specifications (for all MP categories, see Table 3; for definitions of categories, see Appendix). This chapter is divided into two parts – Descriptive characteristics of articles and Differences among articles. Data extracted from 156 articles included and processed with IBM SPSS Statistics (v. 25) are comprehensively reported in Appendix. Descriptive Characteristics of Articles In order to conduct general descriptive statistics, we separated the articles according to the methodological approaches used into qualitative (n = 32), quantitative (n = 76) and mixed (n = 48) clusters. Most of the studies were examined within the Anglo-Saxon legal system (73.7%), especially in the USA (47.4%). Even though 114 studies (73.1%) focused on LC as their primary outcome, only 43 (27.6%) of all studies had a theoretically based background. Although the majority of studies used a descriptive (42.9%) and analytical (36.5%) study design, only few studies (3.8%) used a experimental design, which is adequate for an analysis of causal relationships. The most used standardized methods include the Inventory of Legal Knowledge (ILK; n = 5), MacArthur Competency Assessment Tool - Criminal Adjudication (MacCAT-CA; n = 5), Survey of Children’s Legal Rights (n = 3), Ethical and Legal Issues in Counseling Questionnaire (ELICQ; n = 2), and Test of Malingered Incompetence (TOMI-L; n = 2). Based on the variety of terms used and constructs measured in the analyzed articles, LC components were identified and coded during data gathering. The most frequently used construct corresponded to a) knowledge about the functions of basic legal regulation, institutions, and the laws, which also incorporates the basic ability to search for such information and to use it (coded as general legal knowledge, LC1, 39.7%); b) the ability to orientate oneself in a legal environment and to perform basic juridical acts such as filing a lawsuit, concluding a contract, or finding a proper attorney (coded as legal awareness, LC2, 35.3%); c) more detailed knowledge of a particular area of legislation (coded as ad hoc legal knowledge, LC3, 76.3%); d) critical reasoning about and an evaluation of a certain legal regulation or court decision (coded as opinion about law, LC4, 36.5%); and e) general trust in law within a state or society, i.e., an abstract, often affective attitude of citizens towards the legal system (coded as trust in law, LC5, 25.6%). We also reported the complexity of LC (i.e., the sum of all five LC components). The majority of the studies reached the complexity of up to three points (89.4%), whereas only a few articles reached the complexity of 4 or 5 points (10.6%). This indicates that there is an enormous space for further research as far as complexity of the entire LC construct is concerned. The detailed descriptive characteristics of all articles are shown in Table 1. It is important to highlight that the general population was examined only in 17.9% of the articles, whereas specific populations (e.g., homeless, LGBT, drug users, and inmates) in 32.7% of the articles. Moreover, only seven studies focused on populations of legal experts (4.5%). It is also interesting to point out that only a few articles reported relevant socio-cultural variables such as SES (6.4%), education (17.3%), nationality/ethnicity (41%), and age (37.8%). Even gender was reported only in 65.4% of the articles. The median sample size was 190.5 (range = 7-11155) and the mean age of participants was 30.5 years (range = 8.6-49.1). It is interesting that articles with reported age completely lack the population of older adults with the mean age higher than 50. Detailed descriptive characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 2. MPs were estimated for each methodological approach separately. Quantitative studies varied between 0.5 and 4.5 points (max 7 points; M = 2.22, SD = 0.99). Qualitative studies varied between 1 and 5 points (max 6 points; M = 3.03, SD = 1.08) and mixed methods studies varied between 0.5 and 9 points (max 13 points; M = 4.82, SD = 2.31). However, mean values of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed studies cannot be compared due to different MP categories for each approach. In general, irrespective of which methodological approach was used, the articles analyzed showed a rather lower to moderate MP3. Table 3 represents the mean score of individual categories of MP (1 = best MP score). As a consequence, the main weaknesses of each methodological approach could be described. Within the sample of qualitative studies, the main weaknesses were in impact of findings (i.e., transparent, clarified, and easily utilized results). As could be expected, these studies had relatively rich theoretical background because of its qualitative nature. However, the result of .452 is still unsatisfactory because this category should be main strength of qualitative approach. Within the sample of quantitative studies, the main weaknesses were in psychometric properties of used methods (i.e., reliability, validity) and lack of comparability and randomized sampling. Also, their theoretical background was unsatisfactory. Within the sample of mixed studies, main weaknesses were categories responsible for conjunction of both qualitative and quantitative approaches (i.e., mix design utilization and symbiosis), unsatisfactory theoretical background, as well as insufficient psychometric properties responsible for both quantitative (validity) and qualitative (data analysis) parts of the studies. Similarly to quantitative studies, mixed studies showed unsatisfactory comparability and randomized sampling as well. Differences among Articles Despite the explorative character of the research and the absence of the explicit set of hypotheses, we decided to perform statistical inference. For this purpose, we included all potential variables into analysis in order to provide regular hypothesis testing. However, for the purpose of avoiding data fishing, all expected relations and differences are described and explained in each of three following thematically coherent subsections (i.e., Differences between Methodological Approaches, Differences in LC Complexity, and Differences between LC Components concerning LC Measurement). The nominal or ordinal character of the examined variables and their non-parametric distributions (Shapiro-Wilk tests were performed) determined possible statistical procedures primarily to robust and non-parametric analysis, such as chi-square tests (χ2), Mann-Whitney (U), Kruskal-Wallis (H), their adequate effect sizes (Cramer’s V, φ, r, E2R), and post-hoc tests where appropriate. Differences between methodological approaches. In this part differences between the methodological approach (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed) and five other variables (i.e., method type, theory-based background, primary outcome, study design, and legal system) were analyzed (see Table 4). Two statistically significant differences (method type and study design) were expected, because specific methodological approaches imply specific study designs and adequate measurement methods (e.g., quantitative approach typically uses questionnaires and qualitative approach is often descriptive). We also expected that continental legal researchers should prefer quantitative approach and that Anglo-Saxon legal researches, who gradually accepted rather sociological and second-order LC paradigm, should prefer qualitative approach. Although continental researchers used quantitative approach in 74.2% studies and Anglo-Saxon researchers only in 40% studies, the difference was not statistically significant. Finally, two statistically significant differences (theory-based background and primary outcome) were found. More specifically, the qualitative approach was more theory-based than other approaches and mixed approach focused more on LC as its primary outcome than quantitative approach. The difference within theory-based background can be explained by the rather theoretical character of qualitative approach compared to the other two. We therefore assume that numerous quantitative and mixed studies examined some of the LC components without realizing the entirety of the LC concept, including its theoretical background (e.g., knowledge of a specific law among nurses; see Cho et al., 2015). Nevertheless, this assumption also suggests that researchers using a qualitative approach should be more likely aware of LC as the primary outcome, which was not confirmed. However, this result had only weak effect size. Differences in LC complexity. This part analyzes the differences between LC complexity (i.e., the number of LC components distinguished in the studies) and six other variables (i.e., method type, methodological approach, primary outcome, study design, theory-based background and primary outcome + theory-based background). Differences in this part were either not significant or significant but with rather weak effect sizes (see Table 5). We expected that a more theoretical qualitative methodological approach, a non-reductionist descriptive study design, and more complex hybrid methods would imply higher LC complexity. Nevertheless, statistically significant differences were found only in two of these cases (method type and methodological approach). Surprisingly, the difference between LC complexity and the study design was not significant. Furthermore, the difference between LC complexity and methodological approach had only minimal effect size and did not show any significant result in the post hoc test. These results suggest that even those approaches and methods which aim to assess the LC concept more comprehensively were not actually able to achieve such a goal. We also supposed that researchers who are aware of LC concept of their primary outcome and are able to offer LC theoretical background properly should study LC in a rather complex and comprehensive way. However, the difference between primary outcome and LC complexity had only weak effect size and the difference between theory-based background and LC complexity was not even significant. Possible interpretation of these results is that despite the complex knowledge of the current LC theory, researchers are not able to assess the LC concept comprehensively. Although the focus on LC as the primary outcome is a necessary condition of the complex approach, it is certainly not sufficient. In addition, we created a new combined variable (i.e., primary outcome + theory-based background) in order to analyze differences within LC complexity between studies, which cumulatively were theory-based and focused on LC as a primary outcome, and the other studies. This difference was neither statistically significant, which could suggest that even meeting both of these properties is not enough to assess the LC concept more comprehensively. Nevertheless, statistical insignificance cannot be understood as a proof of non-existing relation (i.e., a proof in favor of the null hypothesis). Differences between LC components concerning LC measurement. The final part of statistical inference presents differences between each of the LC components (i.e., LC1-LC5) and two variables related to LC measurement (i.e., method type and methodological approach; see Table 6). We assumed that the aforementioned LC measurement aspects are determined by the character of individual LC components. LC1-LC3, which are typically a set of information or skills regarding positive law, should be more frequently examined by quantitative and analytical tools (e.g., questionnaires with closed-ended questions), whereas LC4-LC5, which are characteristic for their attitudinal or emotional relations of an individual towards law, ought to be more suitably examined by qualitative and descriptive tools (e.g., in-depth interviews with open-ended questions or vignettes). The findings of the statistical inference indicated significant differences between methodological approaches and specific LC components, namely the qualitative methodological approach was more frequently used for the study of components LC4 and LC5, whereas quantitative or mixed methodological approaches were more frequently used for the investigation of component LC3. Moreover, researchers used various methods and study designs depending on measured LC components. Namely, LC1 and LC3 were examined more via questionnaire and hybrid methods than via interview, and LC5 was mostly examined via interviews. These results are in compliance with our expectations and suggest that in the context of LC measurement it is necessary to use adequate measurement methods determined by the specific character of each LC component. Possibilities of LC Construct Conceptualization The first main goal presented in this article was the creation of a new general and unifying definition of the LC construct. During full text screening and coding phase of the research new LC-related terms emerged, which could possibly be included into the LC construct (e.g., “legal nihilism”, Hendley, 2012; “legal literacy”, Preston-Shoot & McKimm, 2013; “competency to stand a trial”, Ficke et al., 2006). Nevertheless, each of these terms were successfully incorporated into one of of the distinguished LC components (LC1-LC5) and were, therefore, not able to further broaden the meaning of the LC concept. Contrary to the aforementioned terms, there were actually identified two constructs related to LC, which could potentially enrich the LC concept with new valuable content or meaning. First, the LC “conative/behavioral element” was found in several articles (e.g., Al-Rukaibi et al., 2008; Hull, 2003; Jiang et al., 2013; Sarat, 1975). Compliance or non-compliance with the law would probably covariate with LC. Nevertheless, it can be objected that non compliance with the law is a consequence rather than an inherent part of LC itself. The conative part was therefore not included into our LC conceptualization. Second, “legal identity” was found in few articles (LC6; e.g., Muñoz, 2016). This LC component should be even more abstract than trust in law and shall contain beliefs and values about what should the ideal system of legal norms look like. By incorporating this component, an individual not only becomes the object of legal regulation but also its co-creator. Law and an individual (as a member of society) create hereon mutually constitutive relationship, which corresponds to the newest LC research development described in the first chapter of this article. Despite its inclusion into our LC conceptualization, this LC component was identified in a negligible number of articles and was, therefore, not reported in the Results section. Based on the previously presented overview of possible LC-related constructs as well as of descriptive characteristics, we suggest that the LC concept shall consist of six components (LC1-LC6), namely “general legal knowledge” (LC1; e.g., Crawford & Bull, 2006), “legal awareness” (LC2; e.g., Cho et al., 2015) “ad hoc legal knowledge” (LC3; e.g., Erickson et al., 1993), “opinion about law” (LC4; e.g., Jülich, 2006), “trust in law” (LC5; e.g., Berrey et al., 2012), and “legal identity” (LC6; e.g., Muñoz, 2016). These components can be further connected into two separate dimensions of LC. LC1-LC3 components are focused on what law is, i.e., “LC ‘real’ dimension” or “de lege lata dimension ”, whereas LC4-LC6 components aim at what law ought to be, i.e., “LC ‘ideal’dimension” or “de lege ferenda dimension” (for further information, see Engel, 1998; Hertogh, 2004; Podgorecki, 1973; Rehbinder, 2003). To conclude the conceptualization, the six LC components (and two LC dimensions respectively) can be synthesized into the following universal (i.e., generally acceptable and cultural independent) definition of the LC concept: Legal consciousness is a complex of law-related knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs, and values of an individual, whereby the mutual relationship between the individual and law is being created, deepened, and developed within the context of specific society and legal system providing such system with the necessary authority and legitimacy for the regulation of human behavior. We believe that this definition includes all important characteristics of the LC concept and simultaneously excludes all similar but still different terms and constructs. It also endorses its potential impact on the functioning of the legal system. This is especially crucial in the light of the conceptualization and methodological problems observed in this review. We found that numerous researchers (those using quantitative and mixed approaches more than those using qualitative approach) study LC without even being aware of doing so (see Table 4). Furthermore, even the deep and proper knowledge of current LC theoretical background does not help researchers to achieve higher LC complexity (i.e., to study the LC concept in a sufficiently comprehensive way; see Table 5). This finding suggest that current LC theory is not satisfactory and complex enough. We suggest that the primary cause of this problem lies in the insufficient and too vague definition of the object of study itself. So far, the most comprehensive definition by Merry (1990), who describes LC as “the ways people understand and use law” and consciousness as “the way people conceive of the ‘natural’ and normal way of doing things, their habitual patterns of talk and action, and their commonsense understanding of the world” (p. 5) is still too general, abstract, and consequently vague. It is impossible to find out, what “understand and use law” specifically means and how to operationalize those properties. We believe we have provided a clarification of these former definitions within this review article. The definition and conceptualization presented in this article is not in contradiction with current LC paradigms. On the contrary, it combines, deepens, and specifies these definitions as well as current knowledge in order to allow further development of the LC research field. Possibilities of LC Construct Measurement The second main goal presented in this article was the comparison of current methods of LC measurement and suggest a set of criteria for the development of the optimal LC measurement method. At the beginning of this section we focus on several specific methodological problems observed in the analyzed articles. First, examined articles showed a lack of ability to report the results properly because many important values were missing (e.g., effect sizes, reliability and validity estimates, etc.). Second, most of the articles did not report relevant socio-demographic and cultural variables, such as ethnicity, education, age, or SES (see Table 2). We assert that these factors are important determinants of LC at an individual level (see Horák & Lacko, 2019b). Therefore, omitting these variables could limit the analysis of individual differences at LC level. Third, most of the articles were focused on a specific (i.e., contrary to general) population. Therefore, their results cannot be smoothly generalized to the common society. Fourth, the majority of studies were conducted in the Anglo-Saxon legal system (see Table 1). Since every legal system and legal culture is unique in a way (Horák & Lacko, 2019a; Horák & Lacko, 2019b), it can be supposed that the LC construct is perceived and understood differently across the world. For example, Miyazawa (1987) argues that LC is understood differently in Japan than in the USA. Thus, it is possible that there are differences in the usage of LC between Anglo-Saxon and continental legal systems (cf. Hertogh, 2004) as well as between two countries within one legal system (cf. Cowan, 2004). Ignoring potential cross-cultural differences represents a danger of artificial implementation of methods and results in societies where they do not fit. Fifth, all analyzed articles shared weaknesses as far as methodological properties (MP) are concerned (see Table 3). Generally, the MP of the examined articles was not satisfactory even though we deliberately designed it only as a set of minimum requirements for scientific and empirical method of measurement. Although a few of the examined articles evinced an almost maximum level of MP, it is not possible to evaluate them as “ideal”, because there are many more factors on top of methodological properties assessed in this review. Besides these specific problems, a more general issue was also identified. The findings of the conducted review suggest that researchers used all mentioned methodological approaches (quantitative, qualitative, and mixed), as well as various study designs and methods, while the questionnaire was the most used method of all (see Table 1). Moreover, all LC components were represented in the articles with the exception of LC6 which had only negligible occurrence. On the one hand, the diversity in LC operationalization as well as methodology of LC measurement suggests that LC is an interesting topic accented by numerous researchers across various scientific disciplines. Consequently, the LC research field is characterized by enormous complexity and variability. It is also positive, that researchers attempted to use the different measurement methods for assessing specific LC components (see Table 6). This suggests that all of the identified methods can be beneficial for LC measurement, but it is crucial to use only adequate methods determined by the specific character of each LC component. On the other hand, this situation causes ambivalence and methodological chaos. This is even amplified by the fact that no broadly accepted and validated LC measurement instrument have been developed yet. Even though the latest development of the LC research field seems to prefer and advocate qualitative methodological approach (e.g., Ewick & Silbey, 1998; Gómez, 2016; Merry, 1990; Nielsen, 2000; Sarat, 1990; Young, 2014) for its presupposed ability to analyze the LC concept in more complex (i.e., non reductionist) way, the results showed that the complexity of LC research is rather poor irrespective of the methodological approach used (see Table 5). Within these conditions the results of the analyzed articles are hardly comparable and therefore no meta-analysis can be conducted. Consequently, LC researchers are able to produce a plentiful of partial knowledge about rather specific aspects of the LC concept but are not able to study and understand this phenomenon comprehensively and deeply enough to provide results influencing the real functioning of legal praxis (e.g., law-making and judiciary). The potential of LC research remains therefore unfulfilled. In spite of searching for an optimal measurement method in the selected articles, we decided to point out the major mistakes and provide the set of criteria for such a method. The optimal method of LC measurement for empirical and scientific purposes depends not only on the perfect MP (such as proper theoretical background, psychometric characteristics, impact of results, etc.), but also on a) consideration of both the LC concept in its complexity and the specifics of individual LC components, b) ability of testing and analyzing the real level of LC within the general population, c) standardization and normalization, d) elimination of researchers’ subjectivity, e) consideration of socio-cultural variables and their adequate statistical procedures (e.g., in case of different ethnicity: invariance measurement, multi-level analysis, multi-group factor analysis, etc.), and f) applicability of results to practical functioning of legal system (e.g., legislation, legitimacy of law, and legal education). As for future directions of LC research, the next step should rest in designing a new, reliable, and valid measurement method of the LC concept based on the presented conceptualization in its entire complexity and to conduct pilot testing of such method as well as the whole standardization procedure. This method should be used for empirical research of LC on the general population as well as for finding relevant socio-cultural variables determining the LC concept (see Horák & Lacko, 2019b). Since the six extracted LC components were derived from reviewed articles and not from the measurement of the LC concept itself, further empirical research (e.g., by factor analysis) could lead to a different amount or definitions of LC components compared to those presented in this article. Moreover, its findings could verify the real level of legitimacy of law in the legal system as well as provide important recommendations and suggest desirable improvements for both the legal system (i.e., law-making and judiciary; see Horák & Lacko, 2019a) and the individuals within this system (i.e., their knowledge, skills, and attitudes towards law). As far as legal system is concerned, in order to be considered legitimate, law should be understandable (LC1), accessible (LC2), recognizable (LC3) and rationally (LC4), intuitively (LC5), and axiologically (LC6) acceptable to people. In other words, every individual LC component, if assessed and measured properly in the population, can provide an answer to the question whether laws and judicial decisions meet the demands of social efficacy and elimination of extreme injustice presented for example by Alexy (2016) in order to be considered legitimate by the people. Practical application of LC measurement and its results can be found in both preventive (ex ante) and subsequent (ex post) measures. Among preventive measures, the most important one is the possibility to significantly improve current Impact Assessment (IA), which the legislator ought to conduct before any laws are enacted (e.g., Bäcklund, 2009). One of the most neglected deficiencies of IA may be seen in the absence of assessing the sociopsychological impact of legal regulation, i.e., the impact on the six LC components. We assert that studies of understandability, accessibility, recognizability, and rational, intuitive and axiological acceptability of laws for individuals and society should be one of the most important and inherent assessments in the framework of IAs in the future. Possible ex post measure, which should be nonetheless used rather restrictively, is the competence of constitutional courts to hold unconstitutional a statute or a judicial decision, if such legislation or decision extremely fails to meet the demands derived from individual LC components (for further discussion see Horák & Lacko, 2019b). Concerning individuals within the legal system, practical applications could be found especially in new innovative and rather personalised ways of dissemination of legal information (e.g., Janeč, 2019) and, more generally, legal education. These measures could potentially enhance the level of LC in the population significantly. A systematic review of 156 selected articles focusing on the concept of LC was conducted. Main research goals were to provide a unifying conceptualization of LC as well as to discuss the possibilities of an empirical LC measurement. Concerning the conceptualization of the LC concept, this article provided two important outcomes. First, six separated LC components (LC1-LC6) encompassing all the possible aspects of the LC concept were identified. Second, a complex and unifying a definition of LC based on the aforementioned LC components with the potential to solve current conceptualization issues was introduced. As far as the possibilities of empirical LC measurement are concerned, this review provided a set of descriptive characteristics as well as statistical inferences describing and analyzing LC measurement among selected articles. Findings indicated that there is quite an extensive room for methodological improvement within LC research field. Hence, a set of general quality criteria for a LC research method, which could potentially overcome current methodological issues, was described. We believe that our results, as well as our suggestions and recommendations, will help to enhance future LC research to the state where it can actually produce valid results and findings directly influencing and improving the functioning of the legal system. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. 1 We strongly support the idea of open science (i.e., the open materials and the open data), hence, our materials and data are included within: “Complete data” (https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12890.59840) “Specific data” (https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.33023.25765) “Screening phase material” (https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.21698.63687) “MP assessment phase material” (https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13310.02880) 2 There are two important reasons for the incorporation of a population-related criterion based upon the enumeration of specific age groups. Applying such a process of selection granted us a) the rigorous restriction to only real, not artificial or simulated population by eliminating other potentially misleading terms regarding population type, and b) the possibility of retaining a wide spectrum of age groups providing possibilities of comparison of articles studying various kinds of population. 3 According to MP, the best qualitative studies were Stevens (2013) with a value of 5 and Hernández (2010), Kilmer (2016), Berrey et al. (2012), and Lageson (2017) with a value of 4.5. The best quantitative studies were Murdock (2013), Cavanagh and Cauffman (2017), and Grisso et al. (2003) with a value of 4.5. As for mixed studies, the best MP score was achieved by Block et al. (2010) with a value of 9 and Viljoen, et al. (2002), and Dickert et al. (2012) with a value of 8.5. Cite this article as: Horák, F., Lacko, D., & Klocek, A. (2020). Legal consciousness: A systematic review of its conceptualization and measurement methods. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 31, 9-34. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a2 Funding: This article is part of the project Specific academic research “Legal Consciousness: Concept, Formation, Effects with respect to the Impact of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union on Legal Consciousness in the Czech Republic” [in Czech language: “Právní v─Ľdomí: pojem, formování, účinky se zvláštním zřetelem k působení Listiny základních práv Evropské unie na právní v─Ľdomí v eské republice.”] solved at the Faculty of Law, Charles University. The work was supported by the grant SVV 260 495/2020. References References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in this meta-analysis. See Appendix. Appendix Characteristics of All Reviewed Studies   Note. PP = study with pre/post design; G = group; IG = intervention group; CG = control group; S = study; OVL = overlap in sample; LGB = lesbian, gay, bisexual; LGBT = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer; LC = legal consciousness; y/n = yes/no; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; SES = socioeconomic status; H = hybrid method (combination of various methods, except for observation); P/S = Primary/secondary outcomes; T-B = Theory-based. |

Cite this article as: Horák, F., Lacko, D., & Klocek, A. (2021). Legal Consciousness: A Systematic Review of its Conceptualization and Measurement Methods1. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 31(1), 9 - 34. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2021a2

david.lacko@mail.muni.cz Correspondence: david.lacko@mail.muni.cz (D. Lacko).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS