Police Interviewing in Spain: A Self-Report Survey of Police Practices and Beliefs

[La entrevista policial en Espa├▒a: una encuesta de autoinforme sobre pr├ícticas y creencias de la polic├şa]

Jennifer M. Schell-Leugers1, Jaume Masip2, José L. González3, Miet Vanderhallen1, 4, and Saul M. Kassin5

1Maastricht University, The Netherlands; 2Universidad de Salamanca, Spain; 3Secretar├şa de Estado de Seguridad, Ministerio del Interior, Gobierno de Espa├▒a, Spain; 4Antwerp University, Belgium; 5John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2022a4

Received 21 December 2021, Accepted 3 June 2022

Abstract

Over the past decades, the psychological science has accumulated a large corpus of empirical knowledge about police interviews, deception detection, and suspects’ confessions. However, it is unclear whether European police forces’ practices and beliefs are consistent with recommendations derived from this empirical literature. The study described in this report is part of a larger research project examining European police investigators’ practices and beliefs. An online survey was administered to Guardia Civil (n = 89) and Policía Nacional investigators (n = 126). The survey inquired about the length, frequency and electronic recording of interviews, the suspects’ use of their right to remain silent, investigators’ self-reported skills in distinguishing between truthful and deceptive statements, their estimates of the frequency of (false) confessions, and their use of specific interview tactics. The outcomes provide insights into investigators’ knowledge and practices, highlight specific needs, and allow for a comparison between European and North American police forces.

Resumen

Durante décadas, la ciencia psicológica ha acumulado numerosos conocimientos sobre entrevistas policiales, detección de mentiras y confesiones. Sin embargo, se desconoce si las prácticas y creencias de las fuerzas policiales europeas coinciden con las recomendaciones derivadas de esta investigación. Este estudio forma parte de una investigación más amplia que examina las prácticas y creencias de investigadores policiales en Europa. Administramos un cuestionario online a guardias civiles (n = 89) y policías nacionales (n = 126) de la policía judicial. En el cuestionario se preguntaba por la duración, frecuencia y grabación de las entrevistas, la invocación del derecho a guardar silencio por parte de los sospechosos, la capacidad autoinformada de los policías para diferenciar entre verdades y mentiras, la frecuencia de confesiones (falsas) y el empleo de tácticas concretas de entrevista. Los resultados ofrecen información sobre los conocimientos y prácticas de los investigadores, destacan sus necesidades y permiten comparar las fuerzas policiales europeas y norteamericanas.

Palabras clave

Polic├şa, Entrevista, Interrogatorio, Guardia Civil, Polic├şa NacionalKeywords

Police, Interviewing, Interrogation, Guardia Civil, Polic├şa NacionalCite this article as: Schell-Leugers, J. M., Masip, J., González, J. L., Vanderhallen, M., & Kassin, S. M. (2023). Police Interviewing in Spain: A Self-Report Survey of Police Practices and Beliefs. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 33(1), 27 - 40. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2022a4

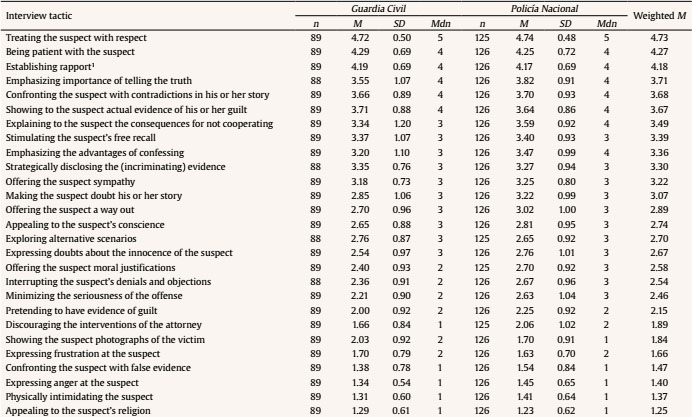

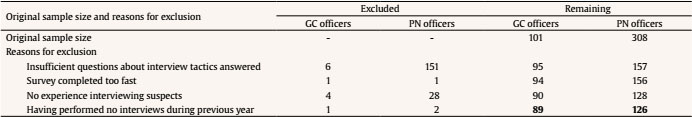

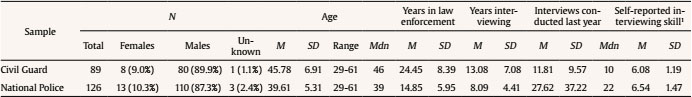

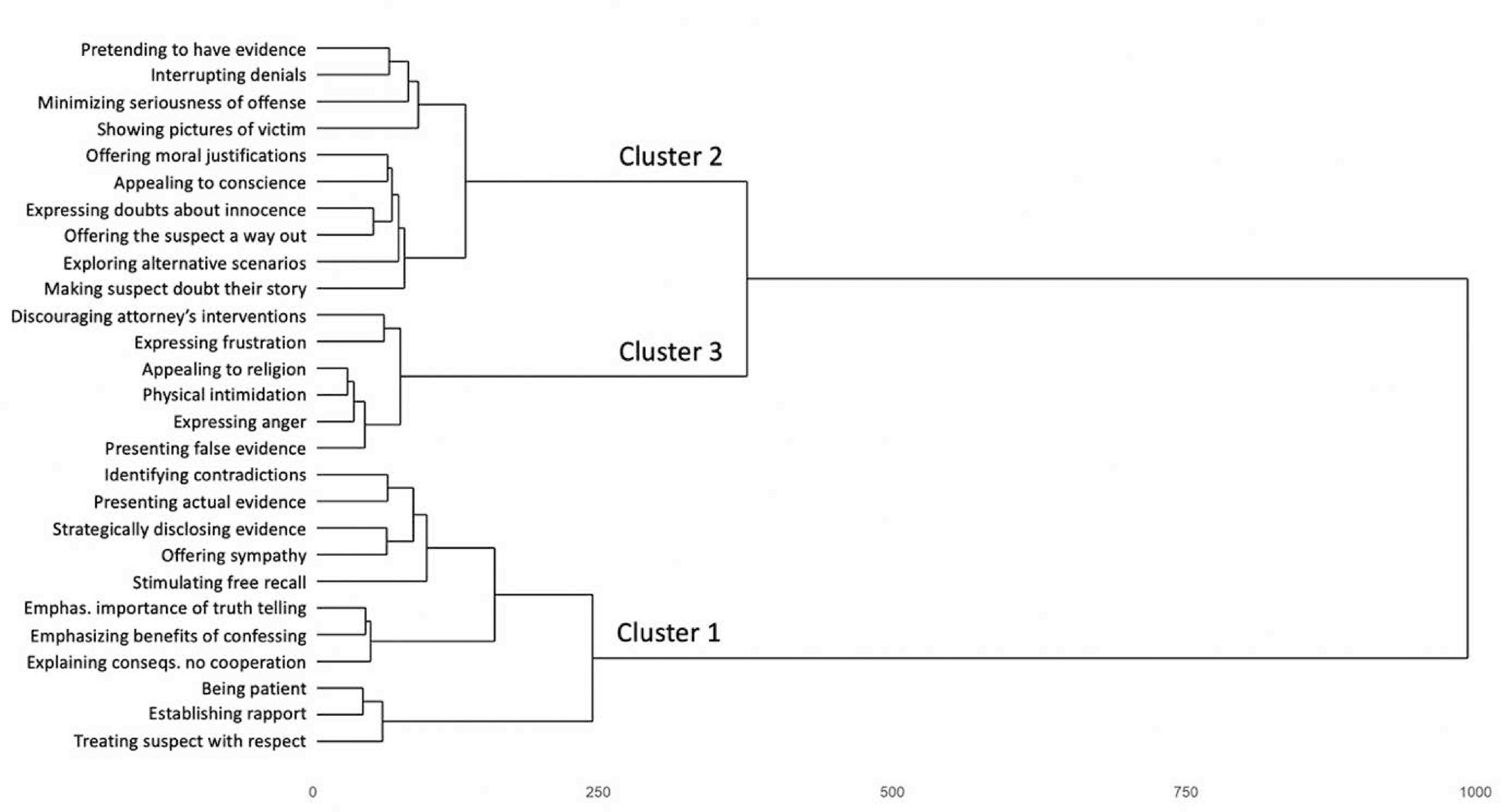

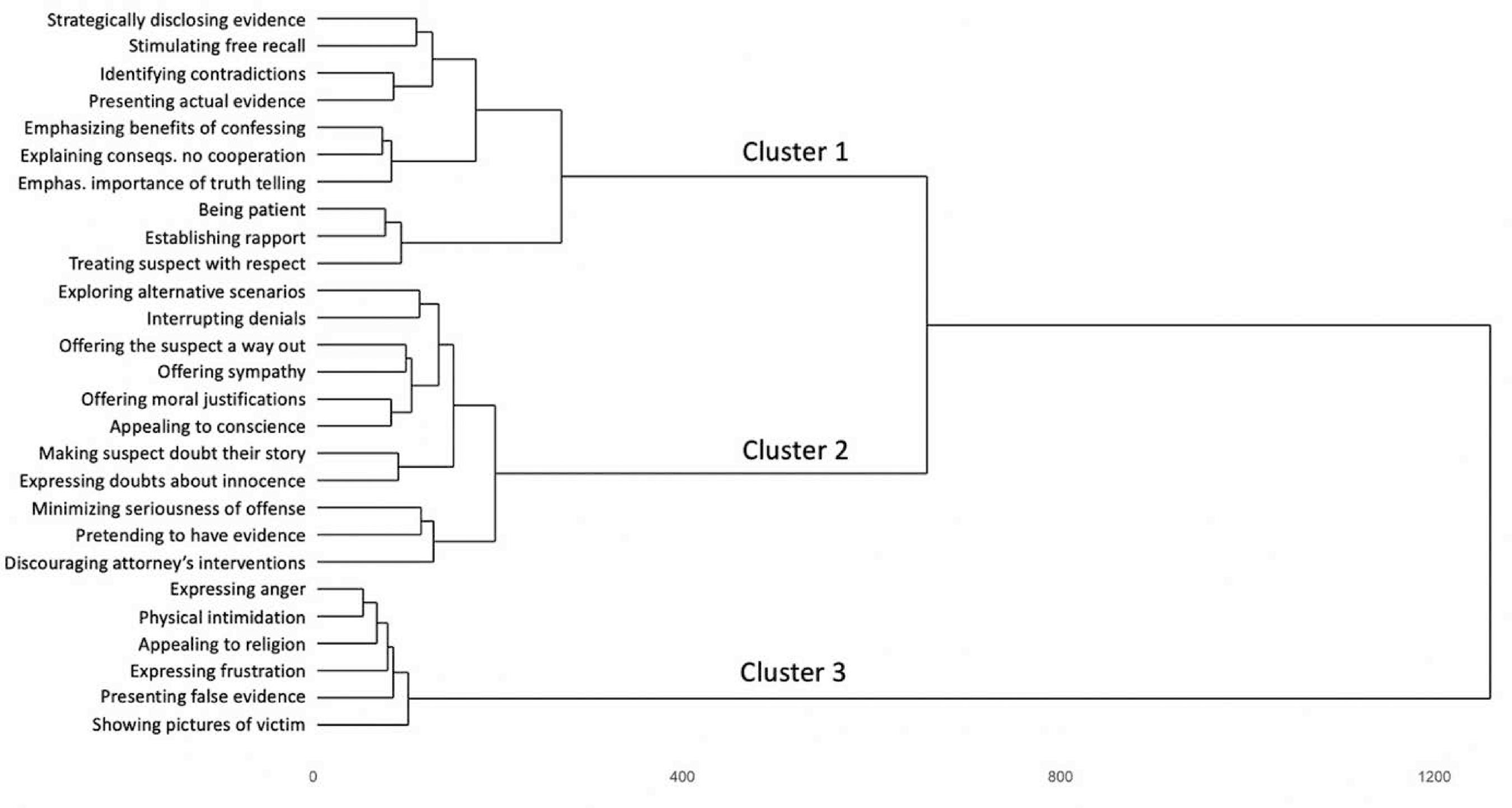

Correspondence: jmasip@usal.es (J. Masip).Over the past decades, much research has been conducted on police interviews and suspects’ confessions (see reviews by Gudjonsson, 2021; Kassin, 2017; Lassiter & Meissner, 2010; Meissner et al., 2017; Milne & Bull, 1999; Vrij et al., 2017). A large corpus of empirical knowledge has been accumulated regarding ethical and effective ways to interview suspects (e.g., Brandon et al., 2018; Milne & Bull, 1999), how to prevent false confessions (Kassin et al., 2010), and lie detection (e.g., Granhag et al., 2015; Masip, 2017). However, it is not known to what extent police forces are familiar with empirical research findings and whether they are applied in practice. Misguided beliefs and practices among law enforcement officers can have detrimental effects, as they can lead to false confessions and wrongful convictions (e.g., Leo & Drizin, 2010). Indeed, false confessions are among the major causes of wrongful convictions in the US (Drizin & Leo, 2004; Innocence Project, n.d.; National Registry of Exonerations, n.d.). Therefore, the question whether police officers’ practices and beliefs align with the empirical evidence is crucial, and the examination of these practices and beliefs may suggest specific areas where the police are in need of training or education. Kassin et al. (2007) conducted a survey to examine North American (N = 631) police investigators’ views and practices regarding suspect interviews and interrogation. However, little is known about European police officers’ views and practices. Based on the original questionnaire by Kassin et al. (2007), we surveyed police investigators from across Europe (Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, and Sweden). The covered topics were the electronic recording of interviews, the use of rights by the suspect, lie detection, false confessions, and interview tactics used. The current paper presents the results from Spain.1 Suspect Interview and Interrogation Approaches When it comes to questioning suspects in police custody, a distinction has been made between an accusatorial and an information-gathering approach. According to Meissner et al. (2017), accusatorial approaches: are generally characterized as both guilt presumptive and confession-focused. Interrogators typically seek to establish control over the suspect, use questions that confirm what they believe to be true, and assess credibility based upon nonverbal indicators and the suspect’s level of anxiety in response to questioning. In this context, interrogators will generally attempt (a) to isolate the subject and create a reliance upon the interrogator, (b) to confront the subject with accusations of guilt and exaggerate the consequences associated with the alleged act (“maximization”), and then (c) to downplay the consequences associated with confession and to offer face-saving excuses for the act (“minimization” ...) (p. 441). Accusatorial approaches are highly prevalent in the US, where the police can legally present false incriminating evidence to suspects, conduct lengthy interrogations, and employ various manipulative tactics to obtain a confession (see, e.g., Kassin et al., 2010). One example of an accusatorial approach is the Reid Technique (Inbau et al., 2013). In contrast with accusatorial approaches, an information-gathering approach: focuses on developing rapport with the subject, explaining the allegation and the seriousness of the offense, and emphasizing the importance of honesty and truth gathering. Subjects are given the opportunity to offer their account without interruption, and investigators are encouraged to actively listen. Thereafter, subjects are questioned with regard to inconsistencies and contradictions in their narrative. This interview method has the goal of “fact finding” rather than obtaining a confession, and investigators are prohibited from deceiving suspects (Meissner et al., 2017, p. 442). Since the early 1990s, the information-gathering approach has been used in England and Wales. Due to evidence of several miscarriages of justice resulting in false confessions as well as several scholarly studies on police interrogation, it became apparent that the police needed training on how to properly interview suspects. This ultimately led to the development of the PEACE approach2 (e.g., Bull, 2018; Bull & Soukara, 2010; Milne & Bull, 1999), which is non-accusatorial and information-gathering. Within this approach, the term “investigative interviewing” is preferred over “interrogation,” which may imply a confrontational questioning style more in line with accusatorial approaches.3 There is evidence that many tactics characterizing accusatorial approaches have the potential of eliciting false confessions (e.g., Kassin, 2017; Kassin et al., 2010). Indeed, a meta-analysis revealed that, relative to accusatorial approaches, information-gathering interviews increase the number of truthful confessions while decreasing the number of false confessions (Meissner et al., 2014). Suspect Interviews in Spain: Legal Safeguards Although, to the best of our knowledge, Spanish officers do not receive extensive formal training on interviewing suspects, a number of legal safeguards ensure that overly coercive tactics are not used. There is a dearth of specific legal regulations in Spain concerning judicial police’s tasks and duties (e.g., Nieva, 2007), including the questioning of suspects (González, 2014). One reason behind this lack of specific regulation may be that criminal investigators in Spain are under the responsibility of an investigative judge rather than the police. Once the judicial police have determined that a crime might have occurred, they must inform the investigative judge, who takes over the investigation. The police reports of the investigation, which are transferred to the investigative judge, are treated as mere formal complaints to the judicial authorities (see Bujosa, 2008; Martínez, 2018). Despite this lack of specific regulations for the police, (a) the Spanish constitution (Constitución Española, 1978) mandates the delivery of rights to detainees (Article 17.3) and establishes the length of custody (Art. 17.2); (b) both the Spanish constitution (Art. 15) and the Spanish criminal law (Arts. 174-176) prohibit torture and any other inhuman or degrading treatment; (c) concerning interviews, the judicial police normally follow the regulations for investigative judges contained in the Spanish Ley de Enjuiciamiento Criminal (1882) (Criminal Prosecution Law; hereafter LECrim); (d) the Spanish Secretaría de Estado de Seguridad [Security State Secretariat] has issued some specific guidelines for the police covering the arrest, custody, and questioning of suspects (in particular, Instrucción 12/2007), which are based on the LECrim requirements for judges; and (e) in 2017, the National Commission for the Coordination of the Judicial Police published a series of criteria concerning the way the judicial police have to perform their job (Comisión Nacional de Coordinación de la Policía Judicial, 2017), which are, again, strongly based on LECrim. Below we summarize the most relevant LECrim articles relative to arrest, custody, and the police questioning of suspects.4 According to LECrim (Art. 520.2; see also Art. 17.3 of the Spanish constitution, Constitución Española, 1978), detainees must be immediately informed in writing, in a language that they can understand, of the reasons for their arrest and their rights. These include, among others, the right to silence, to not incriminate themselves, to legal assistance, to make a phone call to a person of their choice, and to be assisted by an interpreter if necessary. Detainees must also be informed about the maximum length of arrest, and about the procedures to challenge the legality of their arrest (LECrim, Art. 520.2). Both LECrim (Art. 520.1) and the Spanish Constitution (Art. 17.2) establish that “preventive arrest must not last longer than the time strictly necessary to conduct the necessary inquiries to clarify the facts,”5 and that the detainee must be either released or brought to the judicial authority within a 72-hour period. The first statement must be taken within the first 24 hours of arrest (LECrim, Art. 386).6 Also, during the interview, questions must not be misleading or suggestive (LECrim, Art. 389); this also means that interviewers cannot lie to suspects about evidence. Denials cannot be ignored or downplayed because LECrim Art. 396 dictates that suspects must be allowed to say whatever they consider necessary to support their innocence, and that the procedures that they suggest to verify their statements have to be carried out urgently. Furthermore, “in no case can charges or counterclaims be made to the accused, nor will any part of the proceedings be read to them other than their previous statements if they so request, unless the Judge has authorized the publicity of those in whole or in part” (LECrim Art. 396). This latter requirement reduces—though it does not eliminate—the risk of contamination of the suspect’s statement (see Leo & Drizin, 2010). Measures are also taken to prevent fatigue: whenever the interview extends for a long time, or the number of questions asked is so large that the individual shows mental fatigue, the examination must be interrupted for as long as necessary such that the detainee can rest (LECrim, Art. 393). However, overnight interrogation is not forbidden. Suspect statements should be transcribed literally (LECrim, Art. 397) and completely, including both questions and answers (LECrim, Art. 401).7 No erasures or amendments can be made to the transcript; instead, mistakes must be listed at the end of the document (LECrim, Art. 450). Whenever separate statements by the same suspect are contradictory, or the suspect recants an earlier confession, the suspect must be asked to explain the reasons for these contradictions or recantation (LECrim, Art. 405). A confession cannot be the sole basis to establish guilt. LECrim Art. 406 dictates that a confession “will not free the investigating judge from carrying on all necessary procedures to gain the conviction that the confession is truthful, and that the crime has occurred.” Furthermore, the confessing suspect must be asked “to explain the circumstances of the crime and whatever they can contribute to corroborate their confession” (LECrim Art. 406). Also, interestingly, according to Spanish procedural law, a confession to the police is inadmissible as evidence at trial unless the suspect repeats it in the presence of the investigative judge or during the trial.8 Finally, police officers must not use fact-finding procedures “that are not permitted by law” (LECrim, Art. 297.3). All the above requirements suggest that Spanish officers will not endorse “harsh” interrogation tactics typical of accusatorial approaches. However, note that legislation still leaves room for minimization tactics. Also, since Spanish officers receive little formal suspect interview training, it is uncertain the extent to which they will endorse information-gathering techniques. Research on Police Interviews of Suspects in Spain There is almost no empirical research on police interviews of suspects in Spain. We are aware of only one study, which was conducted from a linguistics perspective (Taranilla, 2011). The author examined police suspect interview transcripts to see whether during an interview the police search for the truth in an objective manner or, rather, they try to corroborate their own version of the criminal event. The data revealed that most questions were suggestive or confirmatory. Each transcript contained two different versions of the event: the police’s version, which is apparent in the questions, and the suspect’s version, which is apparent in the answers. In addition, the author also discussed the particular, very unusual syntactic structure of the question/answer sentences in the transcripts (which follows specific prescriptions; see, e.g., p. 318 in Martín & Álvarez, 2011). This structure places the interviewee in the foreground while minimizing the suggestive role of the police. As a result, the transcripts give a misleading impression of police neutrality. A clear limitation of that study is the small number of transcripts, as well as their homogeneous nature (they all were from the same police department and from cases with a subsequent not-guilty verdict with no possibility for an appeal). Recording of Suspect Interviews While the electronic recording of suspect interviews is mandatory in some countries, there is no such legal requirement in Spain. An electronic-recording policy entails many advantages for both suspects and the police (e.g., Kassin et al., 2010). It can deter interrogators from using coercive tactics, thus protecting suspects’ rights (Kassin et al., 2014). At the same time, it may also prevent unfounded accusations of maltreatment or police misconduct stemming from either suspects or their attorneys. Electronic recording also releases interviewers from careful note taking, permitting them to fully concentrate on the interview. Furthermore, it provides a complete and accurate record of both the interrogation process and the suspect’s statements that can be shown to judges and/or juries. This is important, as there is evidence that verbatim contemporaneous accounts of interviews are highly inaccurate (Lamb et al., 2000). Electronic recording can also capture subtle but relevant details that might otherwise be lost. Finally, it can enhance public trust in law enforcement (e.g., Kassin et al., 2010). Right to Silence and Legal Assistance As stated above, in Spain, suspects are granted a number of rights, including the rights to keep silent, to not incriminate themselves, to not confess, and the right to an attorney. Regarding legal assistance, the suspect can freely designate an attorney of their choice to be appointed. If they do not do so, they will be assisted by a public defender (LECrim, Art. 520). A request must be made immediately by the police to the Bar Association to send either the designated attorney or a public defender. The attorney must show up within a period of three hours (LECrim, Art. 520), and formal interviewing cannot commence until the attorney is present. As a general rule, detainees cannot decline legal assistance.9 The attorney can have a private meeting with the suspect both prior to and after the police interview. The attorney should ensure the detainee is informed of their rights and understands them, can inform the suspect about the consequences of making/declining to make a statement to the police, can be present during the interview and, at the end of the interview, can suggest to the officer ask additional questions and to include in the report aspects that s/he believes are relevant (LECrim, Art. 520.6). Deception Detection People worldwide believe that lies can be detected from passive observation of nonverbal behavior (Global Deception Research Team, 2006). Police officers hold similar beliefs as non-officers (Sporer & Schwandt, 2007; Strömwall et al., 2004). However, meta-analyses show that behavioral cues are extremely poor indicators of deception (DePaulo et al. 2003; Luke, 2019; Sporer & Schwandt, 2006, 2007), and that humans trying to separate truths from lies based on the sender’s behavior perform only slightly better than chance (Bond & DePaulo, 2006). Law enforcement officers and other “professional lie detectors” do not outperform laypeople, though they are more confident and display a stronger tendency to judge statements as deceptive rather than truthful (see reviews by Aamodt & Custer, 2006; Alonso et al., 2009; Bond & DePaulo, 2006; Garrido & Masip, 1999). Research conducted in Spain mirrors these international findings. Spanish officers believe deception can be detected from behavior (Masip & Herrero, 2015), have similar (but stronger) beliefs about deception cues to non-officers (Masip et al., 2012; Masip & Herrero, 2015), do not outperform non-officers in judging veracity (Garrido et al., 2004; Manzanero et al., 2015; Masip et al., 2016), display a lie bias (Garrido et al., 2004; Masip et al., 2016; Masip & Herrero, 2017; but see Manzanero et al., 2015), and are more confident than non-officers (Masip & Herrero, 2017; see also Garrido et al., 2004; Masip et al., 2016). The Present Study The goal of this study was to gain insight into European police investigators’ practices, perceptions, and beliefs concerning interviewing and interrogation of suspects. We developed a self-report questionnaire, based on Kassin et al.’s (2007) survey, covering six issues: a) the length and frequency of suspect interviews, b) the electronic recording of interviews, c) the estimated use of rights by suspects, d) investigators’ believed skill in distinguishing between truthful and deceptive statements, e) their estimates of the frequency of (false) confessions, and f) their use of specific interviewing techniques. In this report, we describe the results for Spain. Participants The survey was distributed to two nationwide police forces in Spain: Guardia Civil (Civil Guard; hereafter GC) and Policía Nacional (National Police; hereafter PN). A total of N = 427 respondents participated in the online survey. However, several respondents had to be removed from the sample. Three respondents indicated they were from regional police forces and 15 from local forces. Since the sample sizes were too small for these forces, these participants were removed. Participants who did not indicate their police force were removed as well. The remaining sample contained 409 participants (GC: n =101; PN: n = 308). Several additional exclusion criteria were applied to the sample: first, because of the strong emphasis of this study on interviewing techniques, participants having replied to fewer than 24 (out of 27; see Materials section below) questions about how often they used specific interview tactics were removed (to our surprise, 148 of the 308 PN respondents did not reply to any of these 27 questions); second, we also removed two participants who had completed the survey in an exceptionally short time (less than 5 min); third, respondents who indicated they had 0 years of experience interviewing suspects were dismissed; finally, because many questions in the survey referred to the interviews conducted over the last year, those participants saying they had conducted 0 interviews during the last year were also removed (see Table 1 for details).10 After applying these criteria, the final sample consisted of 89 GC and 126 PN officers (see Table 2 for details). All respondents were members of the judicial police (i.e., crime investigators) rather than frontline officers. As shown in Table 2, nearly 90% were males, their mean age was around 40 (PN sample) or 46 (GC sample) years, had extensive experience in both law enforcement and conducting interviews, and rated themselves as moderately good at interviewing suspects. Their main cases covered a broad variety of crimes (e.g., burglary, corruption, homicide, and sexual offences). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Maastricht University. Materials The questionnaire of the original survey of Kassin et al. (2007) was adapted to the European context. It was subsequently translated into Spanish according to the guidelines for translating established by Pan and de la Puente (2005). Two bilingual research assistants conducted the initial translation, which was then revised in cooperation with the two Spanish researchers. All aspects raising doubts or concern were discussed during an online meeting between the researchers and the translators until a consensus was reached. Also, several adaptations were made owing to specific aspects of the Spanish legislation (e.g., because generally in Spain all suspects must have legal assistance, the question asking respondents to indicate the percentage of suspects using their right to legal assistance was dropped). Finally, a few police investigators participated in a short pilot of the questionnaire. They informed us that the questions were clear for police investigators and provided some general comments about the study. No change to the survey questions seemed necessary based on these comments. Brief instructions placed at the beginning of the questionnaire asked participants to consider the interviews they conducted over the last year with adult suspects concerning various types of crimes. A short definition of suspect interviews was provided. The questionnaire was divided in three sections. The first section focused on background variables; specifically, respondents were asked to report their gender, age, police force, length of job experience as both an officer and an interviewer of suspects (years), main type of cases investigated (open question), estimated interviewing skill (0 [not good at all]-to-10 [excellent] scale), the estimated number of interviews they had conducted over the last year, and whether they had received any specific training (besides their basic initial training to become a police officer) on how to interview suspects. The second section contained experience-based questions. The participants were asked to consider their experiences in interviewing adult suspects over the last year and indicate whether they electronically record their interviews “yes, always”/”yes, in specific cases”/”no”), the kind of record (“audio”/”video”/”sometimes audio, sometimes video”), and whether they believed suspect interviews should be electronically recorded (“no”/”yes, audio”/”yes, video”). They also had to indicate the percentage of suspects using their right to silence and, among those who do so, how many are guilty and how many are innocent (percentages). The same questions were asked again focusing on suspects giving a statement but refusing to answer one or several specific questions. Respondents were also asked to report the average duration of an interview, the duration of the longest interview in which they had been involved, the average number of times a suspect is interviewed, and the interview goal (“to obtain a confession”/”to obtain the truth”/”to gather accurate information”). Investigators also had to estimate how often they can tell whether suspects lie or tell the truth (percentage of times), and whether that depends on whether the suspect confesses or claims innocence (“No, it doesn’t make a difference”/”Yes, I am better at judging whether a confessing suspect is telling the truth or lying”/”Yes, I am better at judging whether a denying suspect is telling the truth or lying”). The final questions in this section focused on confessions. Considering all suspect interviews with adults conducted over their career, the participants had to indicate the percentages of suspects making an admission or confession, whether any suspect had confessed falsely to them (No/Yes) and, if so, how many times, and whether these false confessions had been voluntary or coerced. The third section of the questionnaire listed 27 suspect interview tactics; the participants had to indicate how often they used each tactic (1 = never, 2 = on rare occasions, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). They could also write additional tactics they employed if they wished. Two additional open questions at the end of the survey invited participants to write any thoughts, remarks, etc. that they wished. None of the questions were mandatory—the participants were able to leave a question blank and proceed.11 Procedure To recruit participants, an email message was sent from the Spanish State Security Secretariat (Ministry of Interior) to the Technical Cabinet of the Civil Guard and the General Direction of the National Police. The email contained a letter with an invitation to participate, the hyperlink to the questionnaire, and a request to forward the invitation with the link to police investigators. After clicking on the Qualtrics link, participants were informed about the topics of the survey and that the estimated length of the task would be 15-20 min. Following their consent, participants received the three-part questionnaire. We examined the dataset for all countries for outliers. Both for the average length of an interview and for the longest interview conducted, values under 10 min and over 24 hr were removed. Similarly, whenever a participant said that they could tell whether a suspect lies or tells the truth 0% of the time, this value was deleted. Finally, we computed z-scores for experience (number of years in law enforcement), interviews (number of interviews conducted over the last year), and confidence (estimated truth/lie detection skill). Outlying responses (z-score > 3) were deleted. Some questions were left unanswered by one or several respondents. Therefore, (a) for multiple-choice questions, we report not only the frequency or percentage of participants having selected each option, but also of participants having left the question blank (if anyone did so), and (b) wherever we report means and medians that are not based on all the participants in the sample, we also indicate the number of participants. Furthermore, because some distributions were skewed, we report medians in addition to means. Training The data revealed that 71.90% of investigators in the Guardia Civil (GC) and 92.86% of investigators in the Policía Nacional (PN) had received no specific interview training. Those who said they had received training were asked to indicate the type of training they had received. Examination of the responses revealed that most of the workshops or seminars that they had taken did not focus on interviewing. Rather, they were either general (e.g., “Specialist seminar on judicial police”, “Basic information seminar”, etc.) or specific but unrelated to interviewing (e.g., “Cyberterrorism investigations”, “Dealing with individuals with psychiatric disorders”, “Workshop on homicides”, etc.). In total, only seven (7.89%) GC investigators and six (4.76%) PN investigators provided workshop names or topics explicitly and unambiguously related to interviewing, including lie detection and synergology (these figures include two GC and one PN respondents who said they read relevant materials independently rather than attending formal workshops or seminars). Electronic Recording More than half of the respondents (61.80% of GC investigators and 86.50% of PN investigators) indicated that they never electronically record suspect interviews. Only four GC respondents (4.50%) and one PN respondent (0.80%) said they always make an electronic record. Additionally, 28 GC respondents (31.50%) and 16 PN respondents (12.70%) said they electronically record their interviews in specific cases. Two GC investigators (2.20%) did not reply to this question. Those who said they (always or sometimes) electronically record their suspect interviews (32 GC and 17 PN investigators; the two GC respondents who left the previous question blank also had access to these questions) were asked two additional questions. First, they had to indicate the modality of the electronic record. The most frequent modality was audio (14 GC respondents, 41%, and 8 PN respondents, 47%), followed by “sometimes audio, sometimes video” (13 GC respondent, 38%, and 6 PN respondents, 35%) and video (4 GC respondents, 12%, and 3 PN respondents, 18%). Three GC respondents (9%) left this question blank. Second, they were also asked whether they believed interviews should be electronically recorded and, if so, how (modality).12 Twenty-seven GC (79%) and 14 PN (82%) investigators said interviews should be video recorded, four GC (12%) and two PN (12%) investigators said they should be audio recorded, and only three GC respondents (9%) and one PN (6%) respondent said they should not be recorded. Right to Silence According to GC officers, 79.11% of suspects (SD = 23.05, Mdn = 90%) use their right to silence and choose to not give any statement to the police. GC officers believe that the vast majority of these suspects (M = 91.85%, SD = 11.39, Mdn = 95%) are guilty. Similarly, PN respondents (n = 125) indicated that 82.90% of suspects (SD = 20.11, Mdn = 90%) choose to not give any statement to the police, and they believe that most of these suspects (M = 87.51%, SD = 14.27, Mdn = 90%) are guilty. Suspects who are willing to give a statement to the police may nevertheless refuse to answer certain questions. GC respondents indicated that 30.69% of suspects (SD = 34.27, Mdn = 10%) do so, and that most of them (M = 90.76%, SD = 13.89, Mdn = 95%) are guilty. Similarly, PN investigators estimated that 25.44% of suspects (SD = 35.36, Mdn = 10%) refuse to reply to specific questions, and that most of them (M = 85.01%, SD = 19.44, Mdn = 90%) are guilty. Interview Length and Goals On average, a crime suspect is interviewed 2.22 times (SD = 1.43, range = 1-8, Mdn = 2) according to GC respondents, and virtually the same number of times, M = 2.21 (SD = 1.86, range = 1-11, Mdn = 2), according to GC respondents. The average interview duration is 70.74 min (SD = 34.65, range = 10-200, Mdn = 60) according to GC respondents (n = 88), and 52.64 min (SD = 41.48, range = 10-240, Mdn = 40) according to PN respondents (n = 123). The longest interview in which respondents had participated lasted 183.65 min (SD = 158.76, range = 20-1200, Mdn = 150) according to GC investigators, and 137.29 min (SD = 114.30, range = 30-820, Mdn = 100) according to PN investigators (n = 120). In line with information-gathering approaches, respondents indicated that the goal of the interview is either to gather accurate information (GC: 71.90%; PN: 77.00%) or obtain the truth (GC: 27.00%; PN: 21.40%) rather than to obtain a confession (only one GC respondent, 1.10%, and two PN respondents, 1.60%, chose this option). Table 3 Self-Reported Frequency of Usage of 27 Interview Techniques on a 1 (Never) to 5 (Always) Scale   Note. 1There is no word for “rapport” in Spanish. Therefore, this tactic read “Establecer un buen entendimiento/clima relacional” [“Establishing a good understanding/relational climate”]. Truth and Lie Detection GC officers (n = 88) indicated they can tell whether suspects tell the truth or lie 80.23% of the time (SD = 14.38, Mdn = 80), and PN officers (n = 125) said they can do so 81.40% of the time (SD = 13.02, Mdn = 80). Slightly over 50% of respondents indicated that truth/lie detection skill does not depend on whether the suspect confesses or claims innocence (GC: 52.80%; PN: 55.60%), about 30% indicated that they are better at judging whether a denying suspect is telling the truth or lying (GC: 29.20%; PN: 31.00%), and the rest indicated that they are better at judging whether a confessing suspect is telling the truth or lying (GC: 15.70%; PN: 13.50%; two GC officers, 2.20%, did not answer this question). Confessions The percentage of suspects providing either a full confession or a partial admission during the police interview is 37.39% (SD = 28.65%, range = 0-95%, Mdn = 25%) according to GC respondents, and 35.60% (SD = 28.15%, range = 0-100%, Mdn = 25%) according to PN respondents. A large percentage of investigators (GC: 86.50%; PN: 82.50%) indicated having obtained a false confession. This subset of respondents (77 GC and 104 PN investigators) was asked how many times they had encountered a false confession during their suspect interviews. GC respondents (n = 77) estimated 24.60 times (SD = 33.69, range = 1 - 150, Mdn = 10 times) and PN respondents (n = 93) estimated 15.32 times (SD = 19.21, range = 1-100, Mdn = 9).13 Regarding the type of false confession, out of 73 GC respondents replying to this question, 58 (79.45%) said they had encountered only voluntary false confessions, eight (10.96%) only coerced false confessions, and seven (9.59%) false confessions of both kinds. Out of the GC respondents, 65 (89.04%) said they had witnessed voluntary false confessions, and 15 (20.55%) said they had witnessed coerced false confessions. Similarly, out of 91 PN respondents answering this question, 68 (74.73%) said they had encountered only voluntary false confessions, 12 (13.19%) only coerced false confessions, and 11 (12.09%) false confessions of both kinds. Together, 79 PN respondents (86.81%) said they had witnessed voluntary false confessions, and 23 (25.27%) said they had witnessed coerced false confessions. Interview Tactics Table 3 lists the 27 tactics we asked about in descending order of frequency according to the weighted mean of usage (on a 1-to-5 scale) across both samples. It is noteworthy that the order of tactics was extremely similar for the two samples (r = .98, p < .001). This was due to the ratings being also very similar; indeed, the mean absolute difference between GC and PN ratings across all 27 tactics was only M = 0.18 (SD = 0.13) on the 1-to-5 scale. Table 3 shows that, according to their self-reports, investigators almost always show respect for the suspect. Also, they often establish rapport, are patient with the suspect, emphasize the importance of telling the truth, confront the suspect with contradictions, and show the suspect actual evidence of guilt.14 Respondents also indicated that they sometimes explain to suspects the consequences for not cooperating, try to stimulate free recall, emphasize the advantages of confessing, disclose the evidence strategically, show sympathy, try to make the suspect doubt their story, offer a way out to the suspect, appeal to the suspect’s conscience, explore alternative scenarios, express doubts about the suspect’s innocence, offer them moral justifications, and interrupt their denials and objections. Only on rare occasions do the participants minimize the seriousness of the offense, pretend to have independent evidence of guilt, discourage the attorney’s interventions, show photographs of the victim to suspects, or express frustration towards the suspects. Finally, respondents indicated that they almost never confront the suspects with false evidence, express anger, physically intimidate suspects, or appeal to their religion. We conducted two separate cluster analyses, one for each sample, to identify subgroups of interviewing tactics that are used together. We used the stats and ggdendro packages for R. To measure the distance between tactics, we employed the Manhattan metric rather than other alternatives (such as the Euclidean distance) because it is more appropriate in high-dimensional settings and is easier to understand. We employed the Ward method for linking clusters and saving a dendogram. The outcomes are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. We retained three clusters in each analysis. These clusters made theoretical sense, and the specific tactics clustering together were almost identical across the two samples (the only exceptions were offering sympathy [Tactic 11], showing photographs of the victim to the suspect [Tactic 20], and discouraging the attorney’s interventions [Tactic 21]). This is evidence supporting the validity of the clusters (e.g., Clatworthy et al., 2005). The first cluster mostly involved ethical and respectful tactics; specifically, establishing rapport with the suspect, treating the suspect with respect, being patient, offering sympathy (GC sample only), emphasizing the importance of truth telling, explaining the consequences for not cooperating, stimulating free recall, presenting to the suspect actual evidence of their involvement, doing so strategically, confronting the suspect with contradictions, and emphasizing the advantages of confessing. The mean frequency of usage of this cluster was 3.69 (SD = 0.44) for the GC sample, and 3.80 (SD = 0.42) for the PN sample (1-to-5 scale). The second cluster contained tactics that, despite being neither aggressive nor unlawful, are less benevolent than those in the first cluster and have some coercive potential. These involved minimization techniques (downplaying the seriousness of the offense, offering moral justifications to the suspect, appealing to the suspect’s conscience, and offering sympathy [PN sample only]), attempts to convince the suspect of their guilt (expressing doubts about the suspect’s innocence, pretending to have evidence of guilt, making the suspect doubt their story, interrupting the suspect’s denials, exploring alternative scenarios, discouraging the attorney’s intervention [PN sample only], offering the suspect a way out), and showing pictures of the victim to the suspect [GC sample only]). The mean frequency of usage of this set of techniques was 2.45 (SD = 0.58) for the GC sample, and 2.73 (SD = 0.55) for the PN sample. The third cluster was made up of overly coercive tactics: Expressing frustration, expressing anger, physically intimidating the suspect, confronting the suspect with false evidence, appealing to the suspect’s religion, discouraging the attorney’s interventions (GC sample only), and showing the suspect photographs of the victim (PN sample only). The mean frequency of usage of this cluster was small: M = 1.45 (SD = 0.44) for the GC sample, and M = 1.49 (SD = 0.42) for the PN sample. Pairwise comparisons for the clusters’ mean frequencies of usage were all statistically significant; for the GC sample, all ts(88) ≥ 22.71, all ps < .001, all Cohen’s ds ≥ 1.87; for the PN sample, all ts(125) ≥ 22.66, all ps < .001, all ds ≥ 2.16. In other words, investigators indicated that they use tactics of the first cluster significantly more often than tactics from any of the other two clusters, and tactics from the second cluster significantly more often than tactics from the third cluster.15 Kassin et al. (2007) conducted several regression analyses to see whether certain variables were related to the usage of each of the interviewing tactic factors that they identified. Specifically, the variables they entered in their analyses were experience (years in law enforcement), interrogation training (yes/no), confidence (estimated truth/lie detection ability), the number of interviews conducted by the respondent, and the average length of these interviews. Similarly, we entered the same variables (except interviews, which in our case was the number of interviews conducted over the last year), in six multiple regression analyses: three (one for each cluster) for the GC sample and three for the PN sample. We used linear normal regression models and maximum likelihood estimates (MLE), which are commonly used in statistics. Because the number of predictors was much smaller than the number of observations, only the full models were fitted. The regression model was significant for only one of these six analyses, F (5, 116) = 2.57, p = .030, multiple R2 = .10, adjusted R2 = .06. The more confident PN respondents were in their truth/lie detection ability, the more likely they were to employ Cluster-2 tactics (Table 4). The other predictors were not significant (Table 4). The regression models for the other two clusters were not significant for the PN sample, Fs (5, 116) ≤ 1.90, ps ≥ .099, adjusted R2s ≤ .04, and neither model was significant for the GC sample, all Fs (5, 82) ≤ 1.41, ps ≥ .228, adjusted R2s ≤ .02.16 Table 4 Results of the Regression Model for Cluster 2 for the PN Sample   Note. F (5, 116) = 2.57, p = .030; multiple R2 = .10; adjusted R2 = .06. An open question at the end of the 27 techniques provided the respondents with the opportunity to mention additional tactics that they employed which were not covered by our list. Seventeen GC investigators (19.10%) and 17 PN investigators (13.49%) mentioned additional tactics. These tactics are listed in the Appendix. Open Remarks At the end of the survey, the participants were asked whether they wished to provide additional information and/or remarks, as well as whether they had any comments about the topics covered in the survey. Thirty-two GC respondents (36%) and 26 PN respondents (21%) replied to either of these questions. The most mentioned topic was their need for training on how to interview suspects (GC: 11.24% of the full sample, 31.21% of those who replied to any of these two questions; PN: 11.36% of the full sample, 19.23 of those replying to these questions). The second most frequent topic was complaints about the legal restrictions relative to suspect interviewing (GC: 10.11% of the full sample, 28.13% of those replying to these questions; PN: 10.23% of the full sample, 34.62% of those replying to these questions). Among these restrictions, one in particular stood out: a recent change in LECrim that allows attorneys to talk to the suspect before the police interview; respondents complained that attorneys always instruct suspects to not make any statement to the police at all (GC: 4.49% of the full sample, 12.50% of those answering these questions; PN: 4.55% of the full sample, 26.92% of those answering these questions). Other themes mentioned were the variability across interviews—the interview will differ depending on the crime, the suspect, the circumstances, etc.—(GC: 5.62 of the full sample; PN: 5.68%), a few additional interview tactics, which we added to the Appendix (GC: 4.49% of the full sample; PN: 4.55%), and the assertion that interviews are always conducted in accordance with the law (GC: 2.25% of the full sample; PN: 2.27%). Several additional responses were quite diverse and did not fit any of these main topics. The current findings provide insights into Spanish investigators’ beliefs and practices, highlight specific needs (e.g., the need for training), and allow for a comparison between Spanish investigators and those surveyed by Kassin et al. (2007). We focused on the two nationwide police forces in Spain—Guardia Civil (GC) and Policía Nacional (PN). As their history, nature (military/civilian), geographical coverage (rural/urban), and specific tasks assigned differ (Ministerio del Interior, n.d. a, n.d. b), we analyzed and reported the data separately, yet the pattern of results is almost identical across the two forces. Interview Tactics Spanish investigators appear to be less willing than their American counterparts to use coercive interrogation tactics. Several tactics of this kind were included in both our survey and Kassin et al.’s (2007), and scores were typically higher in the North American sample. Two techniques with relatively high scores among our respondents, confronting the suspect with contradictions and showing the suspect actual evidence of guilt, may look somewhat hostile. However, in Spain interviewers are required to use these tactics (LECrim Arts. 405 and 391). Moreover, they are recommended within the framework of non-confrontational, information-gathering approaches (Bull, 2018; Brandon et al., 2018; Milne & Bull, 1999). Currently, there is some controversy in the US about the police being allowed to lie to suspects about the evidence in pursuit of a confession (Kassin, 2021). In Kassin et al.’s (2007) study, this tactic had an average score of 3.11 on the 1-to-5 scale. Conversely, lying to suspects about the evidence is almost never used by Spanish investigators. With an average score of 1.47, it appears to be employed as infrequently as physical intimidation (Table 3). The separate cluster analyses for the GC and PN samples produced almost identical groupings. The first cluster contained legal, ethical, and respectful techniques. Tactics in this cluster were employed most often. The second cluster consisted of tactics that are permitted by law, are neither hostile nor aggressive, but which may nevertheless be psychologically coercive. These were minimization techniques (see Kassin & McNall, 1991) and attempts to convince the suspect of their guilt (see Henkel & Coffman, 2004). Officers might be oblivious of the dangers that using these techniques may entail for innocent suspects, which calls for science-based interview training. Finally, the third cluster contained overly hostile and coercive tactics. As expected, these are used only rarely. These three clusters differ from Kassin et al.’s (2007) four factors, which were more heterogeneous. The most-often employed factor in Kassin et al.’s study (which contained contradictions, confrontation, and interrupting denials) looks more confrontational than our most-often used cluster. Regarding the tactics that our participants mentioned in response to open-ended questions, these were quite diverse, ranging from several empirically supported techniques, through subtly coercive minimization tactics to the explicit use of manipulation and deception. However, each of these tactics was spontaneously mentioned by only one or a few specific individuals; thus, it is unclear how widespread their use is. Future studies should examine this. In any case, this finding suggests that training is needed to attain more uniformity in the interview tactics used. Legal Safeguards, Police Training, and Police Ethos Our results show that Spanish investigators rarely employ coercive tactics, especially compared to the North American findings. An obvious reason is that they are not allowed to use them as many legal safeguards protect suspects from questionable techniques. Even though legislation is a useful and essential means to prevent police misconduct, there are also caveats. First, while strict legal restrictions might be effective in hindering police misconduct, they may at times hinder the police in doing their job. For example, in Spain, a confession to the police is not admissible as evidence in court unless it is subsequently corroborated to the investigative judge or during the trial. This is indeed an effective protection against injustices due to false confessions coerced by police; however, after talking to their attorney, suspects sometimes recant a prior confession made to the police when they talk to the investigative judge. This often elicits frustration among investigators, who see their efforts going astray. Furthermore, a recent change to the LECrim allows suspects to speak to their attorney before the police interview (rather than only afterward), and investigators complain that attorneys nearly always recommend suspects not to give any statement to the police (this was a frequent topic in the responses to the open-ended questions in the survey). Suspects’ statements, whether they are self-incriminating or not, are an essential source of information to the police. Investigators face serious difficulties to do their job if suspects provide no information at all. In any case, in view of (a) the null evidentiary value of the confession to the police in Spain, and (b) attorneys’ constant practice of advising their clients to testify only when asked by the investigative judge, but not to the police, we believe it is crucial to examine Spanish investigative judges’ practices and beliefs concerning suspect interviews. Second, legislation is no substitute for training. European police recruits spend much more time at the police academy than American officers (Hirschfield, 2020). However, police training should extend far beyond the initial instruction period at the academy. The percentage of respondents saying they had received special interview training was 82% in Kassin et al.’s (2007) study, but only 28% (GC sample) or 7% (PN sample) in this study. After examining the title or topic of the specific workshops or seminars taken by our respondents, it became apparent that the actual figures were even lower (8% and 5%, respectively). In short, virtually none of the Spanish investigators has received any specific training on how to conduct interviews. The investigators are aware of their need for interview training, as this was the topic mentioned most often in response to the open-ended questions. Police interviewers know they must not use the techniques forbidden by the law, but are left with little guidance concerning which techniques they should use. Interview training is imperative. Officers must be knowledgeable about: (a) effective, science-based interview approaches; (b) the risks of employing certain permitted tactics that are nevertheless potentially suggestive (e.g., many of the tactics in the second cluster); and (c) rather than not using highly coercive tactics just because they are forbidden, investigators should also be aware of the specific problems associated with them. Besides legal safeguards, some additional differences between Spanish and American police forces may help explain Spanish investigators’ greater unwillingness to deploy coercive tactics during suspect interviews. The US police have been characterized as increasingly militarized and hostile towards citizens, who are seen as “the enemy” rather than the community whom they are supposed to serve. Aggressive crime control seems to have taken over other police roles, such as providing support to the broad community (e.g., American Civil Liberties Union, 2014). In contrast, the Spanish police have moved away from an authoritarian stance. Currently, Spanish police forces are community-oriented, fully endorse the nation’s democratic values and the constitutional rights of citizens, are respectful and educated in the way they treat citizens, and resort to violence and hostility only under exceptional circumstances, after everything else failed. Using hostility and confrontation is not the norm but the exceptional last resort. The reasons behind these cross-country differences are beyond the scope of this article (see Hirschfield, 2020, for some explanations). Electronic Recording A majority of Spanish investigators said they do not make electronic records of suspect interviews. When they do, they take audio rather than video records. However, about 80% of those who take electronic records believe interviews should be video recorded. These findings align well with the beliefs of North American investigators (Kassin et al., 2007). While an electronic-recording policy entails many advantages for both suspects and the police, concerns have been raised that awareness of the presence of a recording device may distract or inhibit suspects (see Kassin et al., 2019). However, in a recent field study (Kassin et al., 2019), camera-informed and camera-uninformed suspects did not differ across a range of relevant measures (interview length, suspects’ decision to invoke their rights, the detectives’ perceptions of the suspects’ talkativeness and cooperativeness, etc.). Whenever the interview is video recorded, the camera should focus on both the interviewer and the interviewee, since an exclusive interviewee focus leads observers to underestimate the influence of situational forces on the suspect (Lassiter et al., 2010). The electronic records could also be shown to trial judges or the jury. Although this would be at odds with current procedural law in Spain (LECrim, Art. 297), other advantages of electronic recording still hold. In fact, all interactions of the potential suspect with police officers, rather than only the formal interview, should be electronically recorded (Kassin et al., 2010). This measure would prevent overzealous officers from using questionable persuasive strategies before the formal interview and would also disarm suspicious critics who may accuse officers of using such strategies at this stage. Right to Silence Our respondents estimated that roughly 80% of suspects use their right not to make any statement to the police. This figure is in sharp contrast with Kassin et al.’s (2007), whose participants estimated that only 19% of suspects invoke their Miranda rights to silence and to an attorney. Also, our respondents estimated that a substantial proportion of suspects who do make a statement refuse to answer some questions. Finally, investigators in this study considered that about 90% of suspects who refuse to talk are in fact guilty. It is a cause of concern that using one’s constitutional rights is viewed as a sign of guilt. Research is needed to gain more insight into police officers’, judges’, and juries’ perceptions of suspects’ use of their rights (see Geven et al., 2020; Sukumar & Kassin, 2017, cited in Kassin et al., 2020). Interview Length and Goals In addition to being less willing to use coercive tactics than the American investigators surveyed by Kassin et al. (2007), Spanish officers also conduct fewer interviews, and these are shorter. In Spain, a crime suspect is interviewed an average of 2.2 times (3.1 times in Kassin et al., 2007), and an interview lasts an average of 53 (PN) or 71 min (GC) (96 min in Kassin et al., 2007). Our participants were asked to report the duration of the longest interview in which they had participated. Their estimations averaged two hours and 17 min for PN respondents, and three hours and four minutes for GC respondents (four hr and 21 min in Kassin et al., 2007). Interviews are shorter in Spain than in Kassin et al.’s (2007) survey despite the fact that, in Spain, the interviewer must make a break whenever the interviewee shows signs of fatigue (LECrim, Art. 393). This is not the case in the US. Our respondents were asked to report interview length including breaks. In general, the estimated interview lengths are much shorter than those reported in case studies of false confessions (which was 16.3 hours on average; Drizin & Leo, 2004). Virtually all respondents indicated that the interview goal is to gather accurate information or to obtain the truth rather than to secure a confession. This finding aligns well with the recommendations of information-gathering approaches. However, it does not mean that investigators have no specific hypotheses about the suspect’s involvement, nor that they do not try to confirm their hypotheses (see Taranilla, 2011). As pointed out by Nieva (2007), “the police cannot begin their investigations assuming [the suspect’s] innocence because then they would initiate no investigations at all” (section VI, para. 8), and “they [the police] only abandon the investigation when they find no evidence whatsoever of a criminal event. But … they don’t work, of course, to discredit the existence of the criminal event but, on the contrary, to prove it” (section VI, para. 8). Truth and Lie Detection Spanish investigators estimate they can distinguish whether someone is lying or telling the truth about 80% of the time (Mdn = 80%). This figure is similar to Kassin et al.’s (2007; M = 77%, Mdn = 80%), and differs substantially from the conclusions of empirical literature reviews, which show that, on average, both law-enforcement officers and lay individuals judging veracity show accuracy rates close to 54% (Aamodt & Custer, 2006; Alonso et al., 2009; Bond & DePaulo, 2006). Substantial deviations from this value are rare (Bond & DePaulo, 2008; Levine et al., 2021). Studies conducted specifically with Spanish officers yielded similar accuracy rates (Garrido et al., 2004; Manzanero et al., 2015; Masip et al., 2016). In short, Spanish investigators are overly optimistic regarding their truth and lie detection skill. This finding calls for training programs to correct the officers’ misconceptions about their detection ability. About 30% of respondents said they are better at judging the truthfulness of denying suspects, while about 15% said they are better at judging confessing suspects. According to empirical research, police investigators are inaccurate in judging the honesty of both suspects’ denials (e.g., Meissner & Kassin, 2002) and confessions (Kassin et al., 2005). Confessions The estimated percentage of suspects making an admission or confession was 36% (PN) or 37% (GC; both Mdns = 25%). These figures are substantially lower than those reported by Kassin et al. (2007), M = 68%, Mdn = 75. There are at least two possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, while many US interviews seem to be confession-oriented (Kassin et al., 2010), almost all our respondents said that the interview goal was to collect accurate information or learning the truth (note, however, that information-gathering strategies also elicit [true] confessions). Second, as explained above, according to our data many more suspects invoke (vs. waive) their right to silence in Spain (80%) than in the US (19%). This difference can also help to explain the difference in the percentage of suspects making a confession or admission. Although Spanish interviewers stated they obtain fewer confessions than American ones, over 80% admitted to having elicited at least one false confession. Since our data (as well as legal safeguards) suggest that coercive tactics are typically not used in Spain, this rate looks surprisingly high (though most false confessions were voluntary according to the respondents). Kassin et al. (2007) did not ask this question in their survey; instead, they asked investigators to estimate the percentage of innocent suspects giving a false confession. They found a mean value of 4.78% (after removing outliers). This rate is strikingly low considering that coercive and guilt-presumptive tactics that can elicit false confessions (Meissner et al., 2014) are legal in the US, and that many investigators are trained in using such tactics (e.g., the Reid technique; see Kassin et al., 2010). We asked those respondents who said they had obtained at least one false confession how many times they had done so. On average, 15 times (PN sample) and 25 times (GC sample) were reported.17 In Kassin et al.’s (2007) survey, respondents were asked to indicate not only how many times they themselves had obtained a false confession, but how many times they, their friends, or others had done so. Despite the question being much broader in Kassin et al.’s survey than in this study, their rate was much smaller: 0.71 times (after removing outliers). These findings suggest that American investigators might be unwilling to admit they elicit false confessions, or that they might genuinely believe some false confessions they elicit are true. Note, however, that neither we nor Kassin et al. asked respondents to report how they were aware that some confessions were false. Investigators may vary widely in the kinds of indicia employed to determine whether a confession is false, which may affect their estimations. Future research should address this issue. Among our respondents, nearly 90% of those having obtained at least one false confession said these confessions were voluntary. However, over 20% (GC: 21%; PN: 25%) also said they had collected at least one coerced false confession. Limitations There are several limitations with this study. First, only a rather small portion of all Spanish officers completed the survey. Also, we removed many respondents because they did not report their police force or did not answer enough questions to provide useful data. While this may look like a shortcoming, final sample sizes were still large, and we believe that they were representative. Moreover, the participants’ thoughtful, serious, and often detailed responses to the open questions suggest that the retained participants took the task seriously and provided high-quality data. Second, because we used self-reports, the responses may be distorted owing to social desirability bias (Krumpal, 2013). While we cannot discard this possibility, we note that respondents were informed that their answers would be anonymous. More importantly, some of the results are contrary to what one would expect if desirability bias were operating. For instance, we were surprised by the high percentages of respondents saying they had obtained false confessions, including coerced ones. Third, the US data were collected approximately 15 years before the present study, so the two samples also differ along this temporal dimension. Finally, Kassin et al. (2007) noted that they asked participants to estimate percentages, and that research shows that humans are not very good at this task (Burton & Blair, 1991). Our study shares this limitation. Conclusions To our knowledge, our survey is the first of this kind having been administered to large samples of investigators from the Guardia Civil and the Policía Nacional. Compared to the US and Canadian officers surveyed by Kassin et al. (2007), our respondents appear more reluctant to employ coercive tactics, conduct fewer interviews with the same suspect, and these interviews are shorter. They also believe that the goal of an interview is to gather accurate information or learn the truth rather than obtaining a confession—and, in fact, they reported obtaining fewer confessions than North American interviewers. Legal safeguards in Spain and a different police ethos may explain these differences. Most respondents admitted to having obtained false confessions, but these were voluntary more often than coerced. Typically, Spanish investigators do not take electronic records; when they do, these are audio rather than video records. Investigators estimate that about 80% of suspects use their right to silence, and that about 90% of those who do so are guilty. They also overestimate their ability to separate truth from deception. Despite typically not using coercive tactics, Spanish investigators need training on the strengths and perils of specific interview techniques. Their misconceptions about deception detection also need to be addressed. In fact, almost none of the investigators surveyed had received any specific training on how to conduct interviews, and a substantial percentage of respondents stressed their need for training in their responses to the open-ended questions in the survey. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Carmen Jiménez and Lorena Ortiz for translating the survey, investigators who participated in the pilot of the questionnaire, the Technical Cabinet of the Civil Guard and the General Direction of the National Police for their help in recruiting respondents, and especially to all police investigators who took the time to complete the survey. Notes 1 In addition to publishing detailed reviews of the result per country (e.g., Vanderhallen et al., in press), a comparative paper including all results is being prepared. 2 The name of the approach (“PEACE”) is made up of the initials of the separate phases of an interview—namely, Planning and Preparation, Explain and Engage, Account, Closure, and Evaluation. 3 In this article, we decided to use “interviewing” as a single word for convenience. Please note that in this article “interviewing” may refer to either information-gathering approaches, accusatorial approaches, or anything else in between. 4 Some additional safeguards are in place for underage suspects (i.e., younger than 18; see Instrucción 1/2017 de la Secretaría de Estado de Seguridad). 5 These inquiries do not refer to the complete investigation of the crime, but only to certain preliminary procedures, including the collection of a statement from the suspect (e.g., Gimeno, 2004). 6 This period can be extended up to 72 hours for serious crimes. Also, for suspects of terrorism, the length of arrest can be extended for 48 additional hours (LECrim, Art. 520 bis). 7 Doing a full literal transcription is hard and, probably, uncommon; see Taranilla (2011). 8 This requires some explanation. We said in the text that the information collected by the police has to be subsequently transferred to the investigative judge, and it is regarded as a formal legal complaint (LECrim, Art. 297). The criminal case is not open until the judge has examined the police files and has come to the conclusion that a crime may have occurred. After this point, evidence supporting the information transferred to the judge by the police, including the suspect’s statements, must be collected and presented in court. Therefore, the suspects’ confession to the police is not accepted as proof (i.e., a piece of evidence), but something that has to be proven—either by independent evidence of by the suspect herself/himself, who can corroborate their confession in front of the investigative judge and/or during the trial (for detail and interesting legal arguments, see Bujosa, 2008; González, 2014; Martínez, 2018; Nieva, 2007). However, in a number of cases, confessions to the police have been presented as evidence in Spanish courts of law, and the rulings, on appeal, of both the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court have often been contradictory. For an in-depth discussion, and for the criteria that both the Supreme Court and the Constitutional Court seem to have adopted recently, see Martínez (2018). 9 The only exception to this rule is for adult suspects of an offense against traffic safety, and they can revoke their refusal to legal assistance at any time (LECrim, Art. 520.8). 10 Additional criteria were also applied but resulted in no suppression of any participant from Spain (e.g., respondent’s age younger than 18, 0 years working in law enforcement, etc.). Feel free to contact the corresponding author for more information. 11 Both — the English- and the Spanish-language — questionnaires are available upon request. 12 This question was intended to be asked to all respondents, not only to those saying they recorded the interviews or leaving that question unanswered. However, because of a programming error in the online survey it was asked to only this subset of participants. 13 Ninety-six PN participants answered this question, but three of them said they had encountered a false confession zero times (which contradicted their response to the previous question) and were therefore excluded. With these three participants included, M = 14.84, SD = 19.09, range = 0 – 100, and Mdn = 8.5. 14 These two latter tactics are mandated by law in Spain (see LECrim. 405 and 391, respectively). 15 Because for some of the comparisons the assumption of normality was violated, we also conducted non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. These tests also showed all pairwise comparisons to be significant; all Ws = 4005.00, all ps < .001, for the GC sample; all Ws ≥ 7875.00, all ps < .001, for the PN sample. 16 For the PN sample, however, the effect of confidence was significant in the Cluster-1 analysis, t = 2.24, p = .027, and the effect of interview length was significant in the Cluster-3 analysis, t = 2.09, p = .039. 17 Considering also those participants who said they never encountered a false confession, means were 12 times for the PN sample and 21 times for the GC sample. Funding: The University Fund Limburg contributed financially to this project. Cite this article as: Schell-Leugers, J. M., Masip, J., González, J. L., Vanderhallen, M., & Kassin, S. M. (2022). Police interviewing in Spain: A self-report survey of police practices andbeliefs. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 33, 27-40. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2022a4 References Appendix Tactics Mentioned by Participants in Response to the Open Question about Additional Interviewing Techniques not Included in the Survey

Tactical Strategies

Moral Appeals

Playing Tricks or Using Deception

Other |

Cite this article as: Schell-Leugers, J. M., Masip, J., González, J. L., Vanderhallen, M., & Kassin, S. M. (2023). Police Interviewing in Spain: A Self-Report Survey of Police Practices and Beliefs. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 33(1), 27 - 40. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2022a4

Correspondence: jmasip@usal.es (J. Masip).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS