Reliability of Positive and Negative Life Experiences Reported by Inmates: A Pilot Study

[La fiabilidad en los relatos de experiencias de vitales positivas y negativas de los reclusos: un estudio piloto]

Cristina Fernandes1, Ângela Maia2, Tânia Gonçalves2, and Vanessa Azevedo3

1Private Practice; 2School of Psychology, University of Minho, Centro de Investigação em Psicologia (CIPsi), Portugal; 3Faculty of Psychology and Education Sciences, University of Porto, Centro de Psicologia da Universidade do Porto (CPUP), Portugal

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a7

Received 8 September 2023, Accepted 22 May 2024

Abstract

The reliability of life experience reports is a significant concern for both research and practical purposes. However, studies about this topic are scarce and limited: studies mainly focused on negative life experiences, and some populations are under-investigated, such as inmates. This study assessed the temporal reliability of positive and negative life experiences throughout the lifespan based on reports of 30 inmates selected from a convenience sample. Life experiences before and during incarceration were assessed using LIFES, which was applied twice. Results showed that the inmates’ reports are reliable. This study suggests that retrospective reports are reliable concerning experiences before and throughout incarceration. Moreover, when comparing the reliability of positive and negative experiences before incarceration, the reliability was similar. Still, the kappa value was higher on positives than negatives during incarceration despite similar agreement percentage values. The results from this pilot study may be informative and inspiring for further studies.

Resumen

A pesar de su importancia, hay escasez de estudios sobre la fiabilidad de los relatos de experiencias vitales, sobre todo de experiencias positivas y en poblaciones específicas, como los reclusos. Este estudio mide la fiabilidad temporal de las experiencias vividas por 30 reclusos a lo largo de su vida. Las experiencias de vida se han clasificado como positivas o negativas y como previas al encarcelamiento o vividas durante el encarcelamiento. Se aplicó los mismos cuestionarios (LIFES y LIFES-P) dos veces a cada sujeto, con un intervalo de 3 meses, para evaluar su confiabilidad (procedimiento test-retest). Se utilizó el coeficiente kappa de Cohen (?) para evaluar la concordancia. La fiabilidad fue similar en el reporte de experiencias positivas (? = .744) y negativas (? = .746) vividas antes del encarcelamiento, y ligeramente superior en el informe de experiencias positivas durante el encarcelamiento (? = .824) que en negativas (? = .585). Los resultados de este estudio sugieren una coherencia similar en los informes retrospectivos de los reclusos respecto a experiencias positivas y negativas, contrariamente a lo observado en otras poblaciones.

Palabras clave

Reclusos, Evaluación forense, Sucesos vitales, Información autorreportada, Sesgo de información, Informes retrospectivos

Keywords

Prisoners, Forensic evaluation, Life events, Self-reported information, Reporting bias, Retrospective reporting

Cite this article as: Fernandes, C., Maia, Â., Gonçalves, T., & Azevedo, V. (2025). Reliability of Positive & Negative Life Experiences Reported by Inmates: A Pilot Study. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 35, 89 - 98. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a7

Correspondence: vanessa.mazev@gmail.com (V. Azevedo).

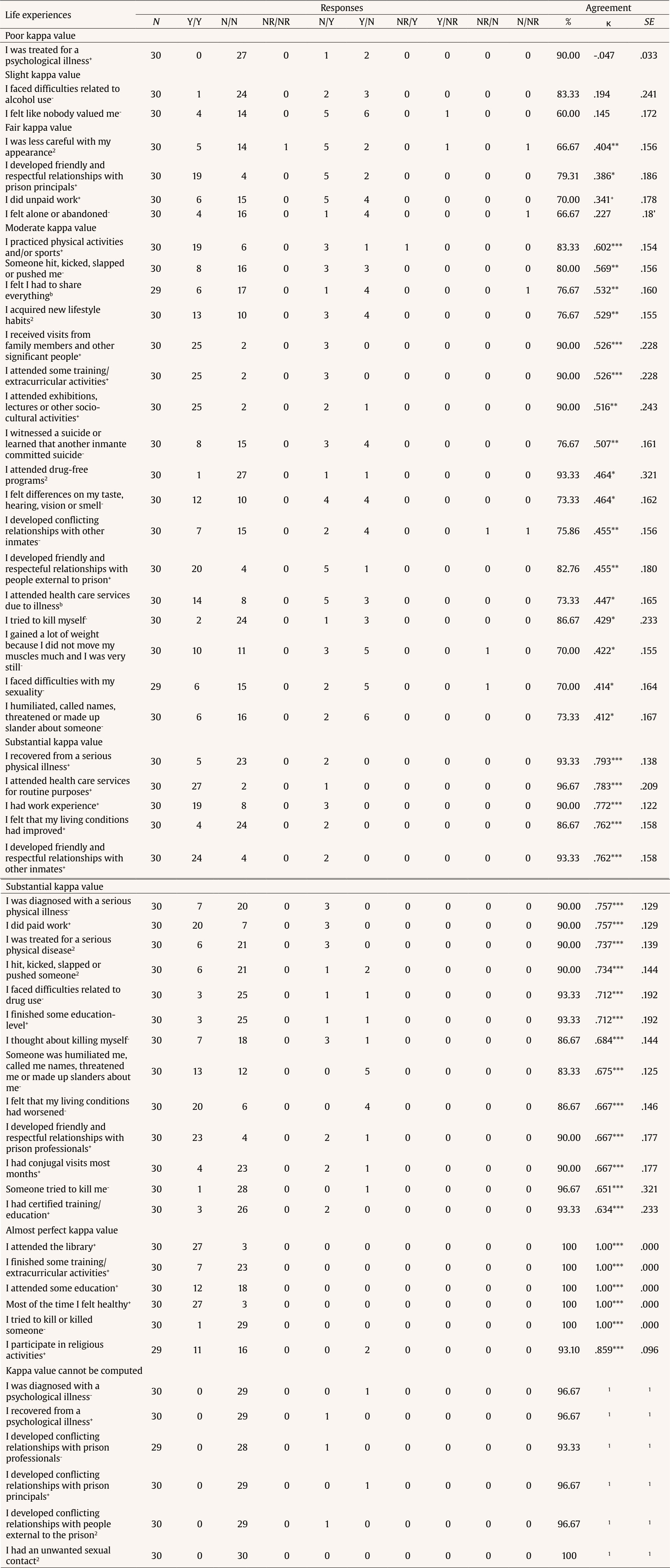

All individuals, throughout their lifespan, live a diversity of experiences that can occur due to their will or in an unpredictable way. Researchers from different fields (e.g., Psychology, Psychiatry, Sociology) and clinicians recognize the impact of these experiences on human health and behaviors. Although there are several studies about life experiences some questions still need to be explored. For instance, life experiences have traditionally been labeled as negative or positive. Negative life experiences, also denominated as adverse (Pinto & Maia, 2012, 2013), traumatic (Garieballa, 2004), and/or stressful events (Martins et al., 2011), are the focus of a wide range of studies. The fact that most of the literature in this field focuses on negative life experiences rather than positive ones suggests that “bad is stronger than good” (Baumeister et al., 2001). Most studies about negative experiences, especially in childhood, describe the impact of these events on individuals who experience them, emphasizing their association with psychopathology in the short-, medium-, and long-term (Garieballa, 2004; Overbeek et al., 2010). Moreover, there are fewer studies regarding positive life experiences. The methodology most commonly used in research about life experiences relies on retrospective self-reports, i.e., reports about experiences that occurred in the past (Beckett et al., 2001; Monteiro & Maia, 2010). However, researchers have expressed doubts about this design, claiming retrospective self-reports are unreliable (e.g., Brewin et al., 1993; Monroe, 1982; Zimmerman, 1983). Indeed, in most studies that apply this methodology, it is almost always identified as a potential limitation. Reliability refers to the stability of the report (Kottner et al., 2011). For instance, when asked more than once to report their life experiences or when using different assessments, individuals are expected to provide similar answers (Dube et al., 2004). The reliability phenomenon has been studied mainly through longitudinal studies, whose results are not conclusive: while some studies suggested a high reliability (Dube et al., 2004; Yates et al., 2008), others noted significant inconsistencies (Azevedo et al., 2022; Fergusson et al., 2000). Studies also indicate specificities in the reliability of reports. For instance, Yancura and Aldwin (2009) assessed the reliability of adverse childhood experiences in a sample of 571 participants aged between 22 and 61, with a five-year time-lapse, through a test-retest procedure. The authors concluded remarkable reliability. However, they found that males had a greater tendency to change their answers, a result that is similar to the results found by Alea and Bluck (2003). Azevedo et al. (2022) reported that inconsistencies in positive experience reports were higher than negative ones in a 171 adult community sample. Besides the heterogeneity and specificities of the results, studies about the reliability of life experiences presented two significant limitations: the experiences studied and the samples investigated. In short, most studies focus on negative life experiences, especially those occurring throughout childhood/adolescence (e.g., Dube et al., 2004; Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Pinto & Maia, 2012). Indeed, as far as we know, only a few exceptions included positive experiences, as is the case of a study that compared the reliability of reports of positive and negative experiences (i.e., Hardt et al., 2006) and the study that compared and predicting inconsistency on positive and negative life experiences reports in a community sample (Azevedo et al., 2022). A study from Hardt et al. (2006), with a sample of 100 patients interviewed with an average lag of 2.2 years, evaluated variables such as family situation, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and protective factors and found moderate to good reliability for most childhood experiences. Azevedo et al. (2022) assessed 171 community individuals regarding their positive and negative life experiences in different domains throughout their lifespan. Researchers found a tendency for overreporting positive and negative life experiences and that inconsistencies were higher on positive experience reports, although both variables were correlated. Additionally, researchers have often focused on community or clinical samples, especially on individuals with psychopathological disorders. While some studies have addressed specific groups like veterans, refugees, or military personnel (e.g., Koenen et al., 2007; Martin-Wagar et al., 2024; Spinhoven et al., 2006), inmate populations have received limited attention. However, understanding the reliability of reports from inmates, encompassing both positive and negative life experiences is crucial to inform the practice with this population (Butler et al., 2022). The unique environment of prison settings presents distinct challenges, including trust, coercion, and social dynamics, which can significantly influence the reporting of experiences (Fazel al al., 2016). Literature states that inmates report a more comprehensive range of negative experiences when compared to the general population (Teplin, 1990). Several studies also indicate a link between experiences of childhood trauma and criminal behavior (e.g., Braga et al., 2018). For instance, Maschi (2006) argued that inmates adopted a criminal career to deal with the accumulation of negative life experiences. However, as far as we know, there is no empirical data about positive life experiences among prisoners. Thus, in the current study, we aimed to explore the reliability of male inmates’ life experiences reports through a test-retest design, assessing negative and positive experiences occurring before and during incarceration, giving special attention to negative life experiences, as these are the most represented in literature (Yancura & Aldwin, 2009) and (Dube et al., 2004). Additionally, to clarify if bad is more reliable than good, we aimed to compare the reliability of positive and negative life experience reports. Participants Participants were recruited in a Portuguese prison that hosted Portuguese inmates (70%) and foreigners (30%) of both genders whose legal and penal situation was preventive or convicted. For this study, the established eligibility criteria were: i) being male, ii) being able to understand and speak Portuguese, and iii) being incarcerated at the two assessment moments. Penal and criminal characteristics were not considered as eligibility criteria. At the first assessment, 32 inmates were assessed; however, during these moments, two of them were released on parole; therefore, a total of 30 male inmates completed both moments of data collection. Considering the participants that were analyzed at both moments (N = 30), aged between 21 and 58 years old (M = 36.97 years old, SD = 10.59), 93.3% had Portuguese nationality (n = 28) and 6.7% other nationalities (n = 2). As can be seen in Table 1, the modal category for marital status was single, followed by married or cohabitation. Concerning education, the modal category before incarceration was primary school and basic education – the second cycle. Throughout incarceration, the majority did not complete any new level of education. Regarding employment status, 66.7% stated that they were employed before imprisonment (n = 20), 30% were unemployed (n = 9), and 3.3% were retired (n = 1). After detention, it was found that 63.3% were employed (n = 19) and 36.7% were unemployed (n = 11). Regarding the legal-criminal status of the participants, more than 90% were convicted. The mean time spent in prison was 2.69 years (SD = 2.07 years), ranging from 30 days to 19 years. The majority of the participants were incarcerated for the first time. Measures Sociodemographic Questionnaire This questionnaire was explicitly designed for this study to describe inmates’ social and demographic characteristics. It included questions about age, education, employment, duration of the sentence, and prior incarcerations. Lifetime Experiences Scale (LIFES; Azevedo et al., 2020) This is a measure to assess positive and negative life experiences, covering different developmental stages, including both lived and non-lived experiences. The first part comprises 75 experiences divided into eight domains: school, job, health, leisure, living conditions, adverse experiences, accomplishments, and people and relationships; for each item, participants were asked if they lived (“yes” or “no or do not remember”) the experience. When they answered positively, three additional questions are asked, namely: i) to identify the developmental stage of the occurrence (“childhood”, “adolescence”, and/or “adulthood”), ii) to rate its valence (“positive”, “negative”, “neutral”), and iii) its impact (in a five-point Likert scale ranging from not at all to completely). To compare positive and negative life experiences, we used the ratings provided by the participants under analysis, considering as positive those experiences rated positively by at least 51% of them and applying the same criterion to identify negative experiences. The index of positive experiences included 37 experiences, and the index of negative experiences included 24 items; the remaining items were evaluated as neutral or undefined. The valence of each experience is identified in Table 2. The second part evaluates non-lived experiences, and participants are asked to write experiences they desired but did not live. This second section was not analyzed in this study. Lifetime Experiences Scale in Prison (LIFES-P, Fernandes, 2013) This an extension of LIFES adapted to inmates, developed especially for this study. This questionnaire included 54 items related to life experiences throughout incarceration and covered the same topics of LIFES: school, job, health, leisure, people and relationships, living conditions, and adverse experiences. Participants were asked about the occurrence of life experiences in prison and its impact. The index of positive life experiences comprised 25 items, and the negative index included 20 experiences. The distinction between positive and negative experiences was based on inmates’ ratings on valence; to be considered a positive experience it had to achieve at least 51% of the rating as positive, and the same reasoning was applied to negative ones. In the second part of the instrument prisoners can still add “not lived, but desired experiences” after incarceration; however, this section was not analyzed. Procedure The Institutional Review Board and the General Directorate of Reintegration and Prison Services approved the study. Of the specificities of our participants, some special ethical cautions were adopted: besides confidentiality and anonymity, we guaranteed that the information provided would be grouped when presented to prison staff and that no information would be added to their records. It was also highlighted that if they chose not to participate or to give up, they would not suffer any penalty or negative consequence. This study uses a within-subjects design; therefore, the same participants were assessed on two separate assessment occasions (test-retest), three months apart, through face-to-face interviews. The sample was convenience-based, and participants were selected by reintegration technicians according to inclusion criteria – having sufficient sentence time to be present during all data collection moments. The strategy for data collection was chosen to minimize the effects of very low literacy since our participants presented a low education level. Initially, participants were invited to participate in a study about life experiences, and those willing to collaborate answered the questionnaires privately. After obtaining the informed consent and due to the pattern of low literacy of the population, the first author administered the questionnaire booklet to each individual. The average length of the data collection was 60 minutes (ranging from 40 to 80 min). The order of questionnaires remained the same between T1 and T2, and participants were aware of the second data collection. However, they were not previously informed that they would be asked to answer the same questions. Statistical Analyses The software IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27, was used to compute descriptive and inferential statistics. To assess the reliability of life experiences, we used Cohen’s kappa for each item and for the different domains (i.e., school career, professional career, health, leisure, living conditions, adverse experiences, achievements, people and relationships, and other experiences). According to Landis and Koch, the following guidelines should be applied to interpret Cohen’s kappa: poor (< .00), slight (.00-.20), fair (.21-.40), moderate (.41-.60), substantial (.61-.80), and almost perfect (.81-1.00). Besides kappa values, we presented p-values and standard errors. The percentages of agreement between the two data collection moments were also calculated. The presentation of at least two parameters of agreement is highly recommended by some authors (Cohen, 1960; Fleiss et al., 2003). Regarding life experiences before incarceration, Table 2 presents the kappa values and percentage of agreement for individual items. As can be seen, Cohen’s kappa ranged from -.03 to 1. The lowest value of kappa was observed in the item “I recovered from a mental illness” (κ = -.034); oppositely, the experiences “I have some work experience,” “I retired (including due to incapability),” “My parents got divorced,” “I had a child,” “I was expelled from school,” and “I was involved in an intimate relationship” achieved a kappa value of 1.00. Overall, 29 life experiences presented substantial values of kappa, 17 presented moderate values, 14 presented almost perfect values of kappa, 7 presented fair values, and 2 presented poor values; in 6 life experiences, kappa values cannot be computed. The percentage of agreement by domains was 71.14% for people and relationships, 84.99% for accomplishments, 86.11% for both leisure and living conditions, 88.88% for school, 94.14% for adverse experiences, 96.06% for job, and 96.14% for health. The mean number of reported experiences was 59.63 (SD = 9.74) in T1 and 63.03 (SD = 13.05) in T2. When we analyzed the participants’ reports, 13.3% reported the same number of experiences on both times, 33.3% reported fewer experiences at T2, and 53.4% reported more experiences at T2. The overall kappa for positive life experiences before incarceration was .744 (SE = .020; percentage of agreement = 87.48), while for negative life experiences, it was .746 (SE = .025; percentage agreement = 87.53). According to Landis and Koch guidelines, these values are substantial. Table 2 Frequencies of Responses and Agreement Parameters for Occurrence before Incarceration   Note. + = positive experience; - = negative experience; ? = neutral or undefined experience; Y/Y = yes response on both assessments; N/N = no response on both assessments; NR/NR = not remember response on both assessments; N/Y = no response at T1 and yes response at T2; Y/N = yes response at T1 and no response at T2; NR/Y = not remember response at T1 and yes response at T2; Y/NR = yes response at T1 and not remember response at T2; NR/N = not remember response at T1 and no response at T2; N/NR = no response at T1 and not remember response at T2; % = percentage of agreement; к = Cohen’s kappa; SE = standard error. 1Statistics were not computed because variables were constant and crosstabs were empty or included a substantial proportion of zeros. 2Valence was not assessed. +p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Reliability of life experiences throughout incarceration, based on Cohen’s kappa, ranged from -.05 to 1. According to Table 3, the item with the lowest value of kappa was “I was treated for a psychological illness” (k = -.047), and items with the highest values of kappa were “I attended the library,” “I finished some training/extracurricular activities,” “I attended some education,” “Most of the time I felt healthy,” and “I tried to kill or killed someone” (k = 1). Overall, 18 life experiences presented substantial values of kappa, 17 presented moderate values, 6 presented almost perfect values of kappa, 4 presented fair values, 2 presented slight values, and 1 presented a poor value; in 6 life experiences, kappa values cannot be computed. Health was the domain with the lowest percentage of agreement (67.88%); the remaining domains achieved a percentage of agreement higher than 90%, namely leisure and people and relationships (both 91.11%), living conditions (93.33%), adverse experiences (95%), job (95.8%), and school (97.5%). At T1, participants reported a mean number of 19.67 (SD = 5.44) life experiences, and at T2, the mean number was 14.47 (SD = 5.10). Furthermore, only 20.0% of inmates reported the same number of life experiences at T1 and T2; 40% of participants increased the number of reported experiences at T2, and 40% decreased. Table 3 Frequencies of Responses and Agreement Parameters for Occurrence throughout Incarceration   Note. + = positive experience; - = negative experience; Y/Y = yes response on both assessments; N/N = no response on both assessments; NR/NR = not remember response on both assessments; N/Y = no response at T1 and yes response at T2; Y/N = yes response at T1 and no response at T2; NR/Y = not remember response at T1 and yes response at T2; Y/NR = yes response at T1 and not remember response at T2; NR/N = not remember response at T1 and no response at T2; N/NR = no response at T1 and not remember response at T2; % = percentage of agreement; к = Cohen’s kappa; SE = standard error. 1Statistics were not computed because variables were constant and crosstabs were empty or included a substantial proportion of zeros. 2Undefined experience or valence was not assessed. +p < .341, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. When comparing positive and negative life experiences throughout incarceration, the overall kappa was .824 (SE = .021; percentage of agreement = 91.20%) for positive experiences and .585 for negative experiences (SE = .037; percentage of agreement = 92.80%); these values were, respectively, almost perfect and moderate, according to the guidelines of Landis and Koch. This study explored the test-retest reliability of retrospective reports about life experiences before and after incarceration among a sample of inmates. We aimed further to compare the reliability of positive and negative life experiences. Overall, reports presented acceptable reliability regarding reporting positive life experiences, both before and throughout incarceration. Moreover, before incarceration, positive and negative life experiences presented a similar value of kappa and percentage agreement; throughout incarceration, positive experiences presented a high value of kappa but similar values on the percentage of agreement. These results suggest that inmates talk or remember similarly positive and negative life events. This may have to do with memory failures, repressing past traumatic situations, the interviewer, fear of reprisals or victimization from sharing negative life experiences that occurred in prison, even after the interviewer guarantees the confidentiality of the study, or simply because they do not want to share them. It may also be related to the fear that the information will be shared with the prison technicians, even though they have been assured that this will not happen, as reported in the study of Rodicio-García et al. (2024), where the results, from a sample of 509 inmates, indicated that there are sanctions for inmates that do not follow the prison’s rules, that may lead to victimization during and after prison. As pointed out previously, studies about the reliability of reports found heterogeneous results. Our results suggested that we can rely on reports, as concluded by Yates et al. (2008) or Dube et al. (2004). The specificities of the inmate population and the relatively short time interval between the two assessments may contribute to the explanation of our results. Surprisingly, the reliability of life experiences before incarceration was higher than throughout incarceration, which may be due to memory problems (e.g., repression, forgetfulness, and/or omission of trauma), the denial of the past; the (absence) of empathy with the investigator; embarrassment regarding sensitive topics; fear of value judgments; social desirability; physical and mental health and mood at the time of the report. In our study, the comparison between negative and positive life experiences reports indicates that, regarding reliability, not always “bad is stronger than good.” When reporting their life experiences, our sample of inmates tended to have a similar reliability in positive and negative experiences. These results contradict the findings of Azevedo et al. (2022), who reported that positive experiences were less reliably reported than negative experiences in a 171-adult community sample. Suh et al. (1996, p. 1095) also concluded that “bad events seemed to be experienced with much more consistency than good events”, which is not the case in our study. More than 80% of the participants presented misreporting (increased or decreased reports of in-life experiences from T1 to T2). These values are similar to those of Dube et al. (2004), Hardt et al. (2006), Schraedley et al. (2002), and Yancura and Aldwin (2009). Some authors claimed several reasons to explain this pattern, including sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age and gender), cultural, racial, or ethnic specificities of participants; types of abuse and its characteristics (e.g., severity); substance abuse; memory problems (e.g., neglect, repression and/or omission of trauma); denial of the past; (lack of) engagement with the task; unclear questions and answers; (lack of) empathy with the researcher; embarrassment regarding sensitive topics; fear of value judgments; the subjectivity of individual perception; social desirability; resilience; physical health; mental health and/or mood at the time of reporting (Dube et al., 2004; Fergusson et al., 2000; Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Martin-Wagar et al., 2024; Miller & Maia, 2010; Widom et al., 2004; Yancura & Aldwin, 2009). Another factor that might explain the possible incongruences in reports is executive functioning, as it plays a crucial role in the reliability of reporting positive and negative life experiences (Morgan & Lilienfeld, 2000). Individuals with impaired executive functioning may struggle with cognitive processes such as attention, memory, and decision-making, essential for accurate recall and reporting of past events (Trajtenberg et al., 2024). For inmates who, according to the literature, already face more challenges, such as trauma, substance abuse, or mental health issues, compared to the community, deficits in executive functioning can further complicate their ability to provide reliable accounts of their experiences. These individuals may exhibit difficulties in organizing thoughts, inhibiting impulsive responses, or sustaining attention, leading to inconsistencies or distortions in their narratives. Our study focused merely on the reliability of reports, if individuals report the same life experiences when asked more than once about them (e.g., Dube et al., 2004). Although our results suggested that reports are reliable, we cannot draw any conclusion about their validity (if these reports are truthful or not) , studies privileged prospective designs based on official records. For instance, Pinto and Maia (2012) compared the Official Records of Commissions for Protection of Children and Youth (CPCJ) with self-reports of adolescents about maltreatment in childhood. They noted a significant number of false negatives (i.e., adolescents with documented maltreatment but who did not self-reported it) and some false positives (i.e., adolescents with no documented specific maltreatment but who self-reported it). One question that arose from the results of this study was the discrepancy between the values of kappa and the percentage of agreement. Specifically, we identified a paradox in some results: some life experiences presented high percentages of agreement but low kappa values (e.g., “I recovered from a psychiatric disease”). Intuitively, we would expect that experiences with a high percentage of agreement would present high values of kappa and vice-versa, but this does not always happen. This paradox was first described by Feinstein and Cicchetti (1990) and Cicchetti and Feinstein (1990), and remains a pitfall for those computing kappa statistics, especially in this field of research (Hardt & Rutter, 2004; Mesquita, 2015). There are two potential reasons to explain this paradox, namely low frequencies and marginal distribution (Cicchetti & Feinstein, 1990; Feinstein & Cicchetti, 1990; Lantz & Nebenzahl, 1996; Vieira & Garrett, 2005). In short, as far as we know, there is no better option to replace kappa statistics, this being the statistical test suggested by many authors (Fleiss et al., 2003; Kottner et al., 2011; Sim & Wright, 2005). Regarding limitations, despite the originality and novelty of this study, we acknowledge that the low number of participants may be a concern that can compromise the generalization of our results. However, as a pilot study within the Portuguese context, where the inmate population is much smaller than in other international contexts, we believe this sample can still help inform future studies in this field. Future studies should be done to improve this feature. Additionally, the type of assessment – i.e., a researcher reading the questionnaires to the participants – may be another limitation. Some studies (e.g., Dube et al., 2004) suggest that participants may feel uncomfortable when asked sensitive questions, which can give rise to misreports. To further explore this issue, different modes of assessment, using a test-retest design, should be performed. Furthermore, there are no guidelines regarding the ideal time interval to collect this type of data, and studies are pretty miscellaneous, ranging from a couple of days to several years. We chose a three-month interval for practical purposes, but it is reasonable to expect they would remember the answers provided at the first assessment. The participants’ incarceration time range was 30 days to 19 years, and this large time interval might have had an impact on findings; perhaps some incongruences might have been present in reports of participants with longer prison sentences – a hypothesis that should be further explored. Moreover, our sample was exclusively male, which can be considered another limitation. Given that, to our knowledge, there are no studies about the reliability of positive and negative life experiences in inmates and the fact that literature reports gender differences between men and women, we opted to develop this pilot study with the group with the highest prevalence of crimes – men. Additionally, there was only a small group of 10 female inmates in the prison where data was collected, which would not have been enough to do a gender comparative analysis. Thus, we acknowledge that the results of our study cannot be generalized to female inmates, hence the importance of future studies replicating it with a female population. Besides the mentioned limitations, our study contributed to identifying some possible practical implications, such as the importance of recognizing the reliability of inmate reports to criminological science, as it informs whether studies using assessments with this population can accurately capture information or if biases distort it. By evaluating reliability and ensuring the accuracy of the reports, we can provide valuable insights to forensic practice because we can identify the genuine needs of this population, contributing to the development of more targeted and effective rehabilitation intervention strategies, thereby potentially lowering rates of recidivism and overall criminality, consequently fostering safer societies (Kenny & Grant, 2007). Additionally, future studies should be carried out to assess the role of executive functioning on inmate population reports. As the literature indicates, inmates have more executive functioning dispairs compared to the general population, suggesting that reports of both positive and negative life experiences in the inmate population may be less reliable potentially affecting the assessment of their needs, treatment planning, and overall outcomes within correctional settings. Therefore, understanding the impact of executive functioning on reporting life experiences in this population is pivotal to ensuring the validity and effectiveness of interventions that support inmates’ rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. In sum, considering the novelty of assessing the reliability of positive and negative life experiences among inmates, we can conclude that, overall, this group tended to present reliable reports of their lived experiences. Moreover, contrary to other populations, reliability seems similar in reporting positive and negative experiences. These results are challenging and informative for researchers and clinicians or justice professionals working with this group. As it is a pilot study, it should be disseminated and strengthened. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Fernandes, C., Maia, A., Gonçalves, T., Azevedo, V. (2025). Reliability of positive and negative life experiences reported by inmates: A pilot study. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 35, 89-98. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a7 Funding Ângela Maia was supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (Ref.: UIDB/PSI/01662/2020). Vanessa Azevedo was partially supported by national funding from the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (UIDB/00050/2020). References |

Cite this article as: Fernandes, C., Maia, Â., Gonçalves, T., & Azevedo, V. (2025). Reliability of Positive & Negative Life Experiences Reported by Inmates: A Pilot Study. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 35, 89 - 98. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2025a7

Correspondence: vanessa.mazev@gmail.com (V. Azevedo).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS