Is perception of the mainstream legal system homogeneous across ethnic groups?

[¿Es la percepción del sistema legal homogénea entre distintos grupos étnicos?]

EstefanĂa EstĂ©vez LĂłpez1 , Marina Rachitskiy2 , Carla RodrĂguez3

1Univ. Miguel Hernández de Elche, Dep. PsicologĂa de la Salud, Alicante, España ,2Blake Hall College, London, United Kingdom ,3Foundation for Science, Health and Education, Madrid, España

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2013a5

Abstract

There is a great social debate regarding possible legal privileges favouring some ethnic groups over others in a particular society. This fact may negatively influence citizens' perceptions about fairness and legitimacy of the mainstream legal system and, thus, compliance with established social norms. The main purpose of the present study was to analyse the perception of the mainstream legal system in citizens belonging to different ethnic groups. In particular, this work had two objectives. First, the purpose was to explore interethnic perceptions of legal authorities and the justice system by examining the following variables: procedural justice, distributive justice, legitimacy of the legal system, contact with police, and reasons for obeying the law. A second objective was to test the predictive power of perceived procedural justice, distributive justice, and contact with police in the subsequent perception of legitimacy across the different ethnic groups. The sample was composed of 351 participants, who were split into two groups: White-Europeans (76.4%) and ethnic minorities (23.6%). Results revealed ethnic group differences in all study variables, showing ethnic minorities a more general negative attitude towards the legal system in terms of procedural justice, distributive justice and legitimacy conceded to the legal system, in comparison with the majority group. Moreover, legitimacy conceded to legal authorities was predicted by procedural justice, but not by distributive justice neither contact with police, in both groups. Practical and policy implications are discussed based on the importance of citizens' perceptions about the legal authorities in order to legitimate the mainstream legal system.

Resumen

Existe actualmente un gran debate social acerca de los posibles privilegios legales que pueden favorecer a ciertos grupos Ă©tnicos frente a otros. Este hecho puede influir negativamente en la percepciĂłn de la justicia y legitimidad del sistema legal dominante por parte de los ciudadanos y, por tanto, en la conformidad con las normas sociales establecidas. El principal objetivo de este estudio ha sido analizar la percepciĂłn del sistema legal por parte de ciudadanos pertenecientes a diferentes grupos Ă©tnicos. En particular, este trabajo tuvo dos objetivos. El primero fue explorar la percepciĂłn inter-Ă©tnica de las autoridades legales y del sistema de justicia mediante el análisis de las siguientes variables: justicia procedimental, justicia distributiva, legitimidad del sistema legal, contacto con la policĂa y motivos para obedecer la ley. El segundo objetivo fue analizar el poder predictivo de la percepciĂłn de la justicia procedimental y distributiva y de los contactos con la policĂa en la posterior percepciĂłn de la legitimidad por parte de los diferentes grupos Ă©tnicos. Participaron 351 sujetos divididos en dos grupos: blancos europeos (76.4%) y minorĂas Ă©tnicas (23.6%). Los resultados mostraron diferencias entre grupos en todas las variables del estudio, mostrando las minorĂas Ă©tnicas una actitud generalizada más negativa hacia el sistema legal en cuanto a justicia procedimental, justicia distributiva y legitimidad que les merece el sistema legal. Además, en ambos grupos la legitimidad que se concede a las autoridades legales se predijo a partir de la justicia procedimental, pero no de la distributiva ni del contacto con la policĂa. Se comentan algunas implicaciones prácticas fundamentadas en la importancia de la percepciĂłn que tienen los ciudadanos acerca de las autoridades legales.

Research has consistently documented ethnic group differences in perceptions of formal authority figures and institutions, with minorities being more likely to hold negative opinions (Cochran & Warren, 2012; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004) and show more distrust and less confidence in the police, the law, and the justice system as a whole (Roux, Roché, & Astor, 2011; Schuck, Rosenbaum, & Hawkins, 2008). Most of the research on attitudes toward the justice and legal systems has been guided by Tyler's (2001, 2006) psychosocial perspective, who argues that people will accept decisions and outcomes from the justice system more willingly when they believe that the authorities are using fair procedures based on trustworthy motivations. This argument was confirmed in his research between majority White and minority (African American and Hispanic) groups in North America (Tyler, 2006). Other studies have shown that citizens are more likely to accept and defer to legal authorities if authorities' actions are evaluated as fair (Olson & Huth, 1998; Paternoster, Brame, Bachman, & Sherman, 1997).

Perceptions of fairness and respectful treatment are, therefore, key aspects for compliance with legal authorities, while verbal and physical abuse, bias, and disrespectful behaviour on the part of the authorities may produce negative attitudes toward those authorities and consequently lower desire to comply with their decisions and actions (Tyler & Huo, 2002; Wortley, Hagan, & Macmillan, 1997). Perceptions of minority groups are an exceedingly relevant issue for social cohesion within current European multicultural societies. Tyler (2006) suggests that particular attention should be placed on the interrelationships existing between evaluations of fairness, legitimacy conceded to legal authorities, and subsequent behaviour related to law in majority and minority groups.

Procedural Justice, Distributive Justice, and Legitimacy

According to Tyler (2001), people judge fairness in terms of two principal issues: procedural justice and distributive justice. Procedural justice refers to judgments about neutrality and impartiality in the decision making process, inferences of honesty and fairness about the motives of the authorities, and respect shown for citizens' rights (Tyler, 2006). Leventhal (1980) specified six criteria of fair procedures, that is, six rules to apply to procedural justice: consistency (e.g., the procedures are applied consistently); bias suppression (e.g., decision makers are neutral); accuracy of information (e.g., procedures are not based on inaccurate information); correctability (e.g., appeal procedures exist for correcting bad outcomes); representation (e.g., all subgroups in the population are heard from); and ethicality (e.g., the procedures upheld ethical and moral standards). Distributive justice refers to the perceived fairness of the final outcome received. Distributive justice exists when the allocation of an outcome is perceived as appropriate and consistent with the implicit norms of a particular situation, such as equity and equality or need (Adams, 1965). Both perception of procedural justice and distributive justice seem to be a core aspect in shaping the degree to which citizens develop positive or negative behaviours regarding established norms, and attitudes towards the police, the courts, and the law as legitimate authorities (Fagan & Tyler, 2005; Lin, Tang, Li, Wu, & Lin, 2007; Weitzer & Tuch, 2005).

Legitimacy of authorities involves support for those in the position of power, such as police officers and judges, as well as the institutions that these formal figures represent, such as the courts and the criminal justice system. It entails a perceived obligation to obey the law and a predisposition to comply with actions and decisions taken on the part of the legal authorities (Tyler, 2006). Citizens' identification with societal values and the mainstream law has been strongly related to their perceptions of legitimacy of authorities, particularly when they believe that the decisions made and rules enacted by these authorities are "right" and "proper" and ought to be followed (Zelditch, 2001). Conversely, the lack of both confidence in authorities and perception of legitimacy of these authorities can undoubtedly lead to the lack of support and cooperation with the law and legal procedures (Chapman, Mirrlees-Black, & Brawn, 2002; Woodlard, Harvell, & Graham, 2008).

Minorities' Trust in Legal Authorities

Despite the relevant consequences and the crucial role such perceptions have on citizens' behaviour, little research exists on public perceptions of legal procedures, authorities, and institutions (Martin & Cohn, 2004). Moreover, most of the studies have been carried out in the United States, with the minority group being primarily from an African American population (Bobo & Johnson, 2004; Hagan, Shedd, & Payne, 2005; Tyler, 2001; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004). These studies concluded that minorities in North American society were less likely to accept decisions made by formal authorities, less likely to trust the motives of legal authorities, and more likely to perceive the legal process as unfair (Longazel, Parker, & Sun, 2011; Matsueda & Drakulich, 2009; Rocque, 2011; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004). In Weitzer and Tuch's study (2004) it was found that Whites in the United States perceived significantly lower levels of corruption, use of excessive force, and verbal abuse than did African Americans and Hispanics.

Weitzer and Tuch (2004) used the group-position thesis to explain the group relations between the social and legal institutions, which are focused on intergroup competition regarding welfare, status, and power within a society. From this perspective, ethnic attitudes would reflect a collective sense of group position with respect to other ethnic groups. The dominant group tends to perceive more affinity with the policies and institutions that are supposed to serve their interests (Lee & Ottati, 2002), whilst minority groups are more inclined to view those institutions as a visible sign of majority domination (Bayley & Mendelsohn, 1969). From this perspective, minority groups may perceive themselves as being treated as subordinate groups, resulting in their unwillingness to defer to the authorities and institutions that they believe the dominant groups have created to primarily serve their own interests (Tyler, 2006).

Numerous North American studies have documented that people belonging to ethnic minorities are subject to more surveillance in disadvantaged neighbourhoods (Sanchez & Adams, 2011) and are arrested, convicted, and incarcerated at higher rates than the White majority (Kennedy, 2001; Rocque, 2011; Solis, Portillos, & Brunson, 2009). In fact, statistics show significant ethnic disparity in prison populations (Blumstein, 2001; Johnson, 2007). According to Johnson (2007), these overwhelming statistics reinforce the perception of bias, which leads, in turn, to lack of trust and suspicion in relation to procedures of the legal system. This may negatively impact the quality of the criminal justice system, since the absence of confidence can reduce citizens' voluntary participation and collaboration with legal agencies. Indeed, research shows that negative attitudes toward the legal system are related to lower involvement in testifying as witnesses, lower commitment as jurors, and lower likelihood to report crimes (Chapman et al., 2002; Sherman, 2002), particularly among minorities (Reza & Magill, 2006).

A number of studies carried out in Europe have suggested a similar trend. Reza and Magill (2006) observed that individuals of African descent were more likely to be stopped and arrested than White individuals. Other studies have revealed that ethnic minority groups perceive higher levels of discrimination on the part of the criminal justice system agencies compared to the White majority (Murphy, Wedlock, & King, 2005; Shute, Hood, & Seemungal, 2005). Shute and colleagues (Shute et al., 2005) asked their participants whether they think they would be treated worse by the criminal justice system because of their ethnicity: 33% of the African group, and 21% of the Asian group felt that they would be discriminated against, compared to 5% of the White population. These studies suggest that, consistent with the North American findings, minority groups within the UK are also more likely to have higher contact with and more negative perceptions of legal authorities than the White majority.

The Current Study

Citizens with different ethnic identities have diverse conceptions of what is socially correct or fair. Understanding that variety of conceptions may be a crucial challenge for current multicultural European societies. Although existing research highlights that citizens' conceptions and perceptions of the legal system seem to exert a great influence on subsequent attitudes and behaviour with respect to law, there is a considerable gap in the literature on public attitudes towards the police and the legal system (Gabbidon & Higgins, 2009). Firstly, most studies on this topic focus on specific aspects of the judicial context, such as the police or the courts. Secondly, the majority of research has been conducted with samples from the United States, with a lack of studies carried out in the European context (Reisig & Mesko, 2009). Finally, conclusions are mainly restricted to adult populations (Brunson & Weitzer, 2009), with few exceptions involving publications regarding younger groups (Martin & Cohen, 2004).

Given the lack of empirical attention dedicated to analysing perceptions of the legal system by European young citizens belonging to different ethnic backgrounds, and in contexts beyond courts, a study was designed to contribute to the literature by accomplishing two main objectives. The first purpose of this study was to explore the role of ethnicity on the perceptions of legal authorities and the criminal justice system by examining the following related variables: procedural justice, distributive justice, legitimacy of the mainstream legal system, contact with police, and reasons for obeying the law. In light of Tyler's (2006) assumptions about legitimacy of authorities, the second purpose of the study was to test the predictive power of perceived procedural justice, distributive justice, and contact with police in the consequent perception of legitimacy across the different ethnic groups.

Method

Participants

Participants were 351 undergraduate students from a university in southern England, of whom 61.3% were female ( n = 215) and 38.7% were male ( n = 136). Ages ranged from 18 to 30 ( M = 22.4, SD = 3.12). Most of the respondents indicated having a middle socio-economic status (88.9%, n = 312). A majority of the participants described themselves as White-European (76.4%); this group was composed of both UK natives and immigrants from within Europe. The rest of the sample consisted of Non-White immigrants of whom 31 (8.8%) indicated they belonged to the Asian-Chinese ethnicity, 31 (8.8%) were of Indian Sub-continental ethnicity, and 21 (6%) were of the African Caribbean subgroup. For the purpose of this study the sample was split into two ethnic groups: White-Europeans (76.4%, n = 268), and ethnic minorities (23.6%, n = 83).

Procedure

Participants were recruited through the university e-mailing network. A total of 756 students registered at the university were sent an e-mail describing the objectives and interests of the study, and were invited to voluntarily participate in an on-line study. Four hundred and five students filled out the questionnaire, of whom 351 provided complete data. The on-line questionnaire was designed with Sawtooth Software for surveys on the Internet and was estimated to take approximately 20 minutes. Instructions stressed the confidentiality of responses and the anonymity of participants at all stages of the research process.

Measures

Participants were given self-report questionnaires that were based on Tyler's (2006) research. The questionnaires used in the present study included Tyler's items and questions, some of which were adapted for the purposes of this work for the analyses by ethnicity. Four measures were used to assess perceptions of the mainstream criminal justice system: The Procedural and Distributive Justice Scale, the Perception of Legitimacy Scale, the Reasons for Obeying the Law Scale, and a questionnaire about Contact with the Criminal Justice System. Items of these scales are presented in the Appendix. The participants were asked to rate how strongly they agree with each item. The items were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 ( Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree ). Higher scores on each measure indicated more positive perceptions.

The Procedural and Distributive Justice Scale was composed of 10 items. Principal component analysis indicated a two-factor structure underlying the responses on this scale. The first factor (38.72% of variance) was defined by six items referring to procedural justice, and the second factor (17.67% of variance) was defined by four items referring to distributive justice. The final scores ranged from 6 to 30 for procedural justice (Cronbach α = .88) and from 4 to 20 for distributive justice (Cronbach α = .75).

The Perception of Legitimacy Scale was composed of 12 items. This unifactorial scale provides a general measure of respondents' support of legal authorities and predisposition to compliance with the mainstream law. The final measure scores ranged from 12 to 60 (Cronbach α = .81).

The Reasons for Obeying the Law Scale was comprised of 6 items. This scale analyses the following reasons explaining why people tend to obey the mainstream law: People obey the law because they fear punishment, because they agree with the mainstream rules, because they trust in the law and authorities, because they feel authorities are competent, because they consider authorities fair and treating everyone equally, and/or because they feel well represented. This instrument does not give a general measure of reasons, but it is informative at the item level.

Contact with police was measured by asking participants to indicate if they had any contact in the past (yes/no), the frequency of contact (how many times), and in what condition (witness, victim, suspect or offender).

Data Analysis

As for the study of the association between the ethnicity (White-Europeans vs. ethnic minorities) and the contact with police as witness, victim, suspect and offender (yes vs. no), chi-squared analyses were performed with phi for the effect. Correlation analyses were executed to evaluate the general trends of the data among the two ethnic groups, with r 2 for the effect size. As heterogeneity of variance matrices was observed, an unpaired t -test was computed for unequal of variances for the comparison of means. Finally, stepwise regression analyses were carried out to design predictive data-based models of the legitimacy of the mainstream criminal justice system, from the perceived procedural justice, distributive justice, and contact with police. As for the control of multicollinearity, tolerance was computed (all >.90), and for Type 1 error the stepwise models were submitted to a cross-validation (dividing at the sample into random subsamples groups), supporting very close results.

Results

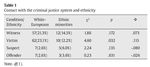

The distribution of contact with police across the different conditions (witness, victim, suspect and offender) for the two ethnic groups is shown in Table 1. Although a higher percentage of White-Europeans reported having had contact with the criminal justice system as a result of being a witness or a victim, more members belonging to ethnic minorities indicated having had contact with police as a result of being a suspect or convicted. The chi-squared test for non-parametric data showed statistically significant differences between the two groups in the role of victim.

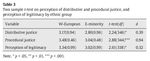

Table 2 presents the results of the bivariate correlations performed on perception of distributive justice, procedural justice, and legitimacy for White-Europeans and ethnic minorities. As can be seen, the two ethnic groups obtained strong positive correlations between distributive justice and procedural justice, explaining 35 and 34% of the variance ( r 2 ), for White-European and ethnic minorities respectively, a large effect size (Cohen, 1988). Correlations between distributive justice and perception of legitimacy were also positive and identical for White-Europeans and ethnic minorities. Nevertheless, the variance explained of the distributive justice by the perception of legitimacy is around 5% for both populations, a small-moderate effect size. Finally, with regards the correlation between procedural justice and legitimacy, the values observed were slightly different between the two groups, with a significant association between these two variables among White Europeans ( r2 = .10) and ethnic minorities ( r2 = .05), a moderate and small effect size, respectively.

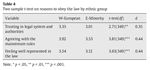

The results of the comparison of means (see Table 3) for perception of distributive and procedural justice and perception of legitimacy by the ethnicity grouping variable (White-European vs. ethnic minorities) revealed significant differences with a moderate effect size in the case of distributive justice and legitimacy and a large effect for procedural justice. Succinctly, White-Europeans reported a more positive perception regarding distributive justice, procedural justice, and legitimacy of the mainstream criminal justice system than the ethnic minorities. This suggested that White-Europeans informed of a higher degree of agreement with the legitimacy of the authorities and legal institutions to impose rules and sanctions for all citizens living in a country. Finally, Table 4 reports the reasons pointed out by both groups in relation to compliance with the mainstream law.

The comparison of means (see Table 4) revealed significant differences, with a moderate effect size, in three of the reasons for obeying the law considered: People obey the law because they trust in the legal system and authorities, people obey the law because they agree with the mainstream rules, and people obey the law because they feel well represented. Again, White-Europeans had a stronger level of agreement on all three reasons than the ethnic minorities.

Finally, a stepwise linear regression was used to evaluate the effect of contact with police -the frequency of contact (how many times)-, procedural justice, and distributive justice on the perceived legitimacy of the mainstream criminal justice system. The results of the regression revealed a support to a model with procedural justice as predictive of legitimacy of the mainstream criminal justice system for both White-Europeans, R 2 = .23, F(1) = 27.20, p < .001, and ethnic minorities, R 2 = .17, F(1) = 3.99, p < .05. These models explained 23% and 17% of the legitimacy of the mainstream criminal justice system, a large effect size, for White-Europeans and ethnic minorities, respectively. Briefly, as for White-Europeans (β = .30, p < .001) and ethnic minorities (β = .22, p < .05), procedural justice is positively related with legitimacy.

Discussion

This study aimed to firstly analyse differences between minority and majority ethnic groups on their perceptions of procedural justice, distributive justice, legitimacy of the mainstream legal system, reasons for obeying the law and previous contact with police. Secondly, the study explored the effects of perceptions of procedural justice, distributive justice, and contact with police on legitimacy conceded to the mainstream criminal justice system among the minority and majority ethnic groups. In regards to reasons for contact with police, the results revealed significant differences in the role of victims. Specifically, White-Europeans were more likely than minority members to have had contact with police in the role of a victim. Although differences in other roles were not statistically significant, at a descriptive level higher frequencies were found for the role of witnesses among the White European group, and for the roles of suspect and offender among people belonging to ethnic minorities.

Considering that ethnic minorities only represent a small proportion of the total population in the country, these results may suggest a discrepancy in numbers also related to perception of injustice. Thus, on the one hand, previous research carried out in the United States has shown a disparity in the over-control of some citizens (Johnson, 2007; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004). For instance, Weitzer and Tuch (2005) found that evidence from street observations of police-citizen interactions and records of police stops, indicated that police indeed tended to view minorities with a high degree of suspicion and as having criminal tendencies. Other studies have also found that minority members are more often stopped (Harris, 2002) and treated more harshly (Terrill & Reisig, 2003), aspects which are closely related to perception of justice. On the other hand, and following the justice system contact hypothesis, previous research has indicated that persons with more intensive experiences of contact with police tend to perceive more injustice than those with no prior contact (Buckler & Unnever, 2008; Buckler, Unnever, & Cullen, 2008; Buckler, Wilson, Hartley, & Davila, 2011; Flexon, Lurigio, & Greenleaf, 2009; Wilson, 2012).

Likewise, the findings of the present study revealed significant differences between White-Europeans and ethnic minorities on both perceptions of distributive justice and procedural justice. White-Europeans reported higher scores on both variables, which entail a higher degree of satisfaction with the outcomes received from the justice system, as well as with the legal processes and procedures. Conversely, citizens belonging to ethnic minorities perceived more unfairness in both cases. These results are in line with previous studies reporting ethnic differences in citizens' views of police and judges misconduct (e.g., Schumann, Steeh, Bobo, & Krysan 1997; Weitzer & Tuch, 2004). These studies concluded that, as a whole, the white majority hold more positive attitudes towards legal authorities and legal procedures and that contact with the justice system tends to have stronger and longer-lasting effects on perceptions of minority groups, both in adults (Tyler & Huo, 2002) and juveniles (Woodlard et al., 2008), as a consequence of their perception of an unfair treatment from the officers. This general negative attitude towards the legal system is based on a shared scepticism of a range of governmental institutions and agencies of the criminal justice (Bobo & Johnson, 2004; Hagan et al., 2005).

As some authors have suggested, the significant differences found in evaluations of the favourability of outcomes and treatment based on ethnicity are strongly linked to perception of legitimacy of the justice system held by each ethnic group (Tyler, 2006; Zelditch, 2001). This seems to be especially the case with procedural justice, as suggested in Tyler's study with North American adults, which indicated that both majority and minority groups based their assessment of legitimacy of legal authorities on their perception of procedural justice (see also Fagan & Tyler, 2005). Likewise, the data of the current study showed higher scores for White-Europeans on the legitimacy perception of the mainstream criminal justice system. Subsequent regression analyses conducted in this work pointed out that, indeed, procedural justice was a predictive factor in relation to perception of legitimacy for both groups. Distributive justice and contact with police did not show any significant effect on legitimacy. These findings are in line with prior research carried out on North American populations (Tyler, 2006) and the study conducted by Page, Wake, and Ames (2004) in England on the essential duties of the criminal justice system, in which participants pointed out that it was "absolutely essential" to treat people fairly regardless of race.

Participants of the present study were also asked for reasons why people in general obey the mainstream law. Significant differences between the two ethnic groups were found on three of the reasons for obeying the law: trusting in the legal system and authorities, agreeing with the mainstream norms, and being represented in the law. White-Europeans scored higher in all cases indicating a faithful support to social norms and legal authorities of their own country, while this support was weaker for ethnic minorities. According to Tyler and Huo (2002), and consistent with our findings, compliance with the legal system and attitudes and behaviours regarding the law are closely related to citizens' identification with societal values. Future research should focus on examining the relationship between reasons for obeying the law highlighted by different ethnic groups and compliance with mainstream social norms.

Although the findings of this study may have practical implications, a number of limitations must be addressed. One of the limitations of this study was the use of a relatively small sample size, which prevented from conducting detailed analyses on the effects of the type of contact (as a witness, victim, suspect, or offender) and the remaining variables. Although some research suggests that the type of contact does not affect attitudes and perceptions towards police (Smith & Hawkins, 1973), the effect of the particular type of contact on perception of distributive justice, procedural justice, and legitimacy should be investigated in future works. Another limitation of this study is that findings are solely based on one source of information, namely undergraduate students, most of them belonging to the middle strata of socio-economic status, which may have an effect on the types of contact with authorities, as well as on how they were treated by the authorities. Finally, future research should combine quantitative and qualitative measures for data collection. Information obtained from interviews or group discussions with participants from different ethnic backgrounds could be valuable in the broader understanding of these findings and in the formulation of interventions and promotion of compliance with the laws and rules set out by the local legal authorities and institutions. It would be also interesting to examine perceptions of the legal system by gender, since some recent work has suggested the existence of differences among men and women in defining their experiences with police (Gabbidon, Higgins, & Potter, 2011).

Despite the above listed limitations, the current study contributes to the literature on different ethnic groups' perception of the legal system by analysing data from a population in a European context. Most of the studies in this field have been carried out in the United States with African American citizens as the traditionally represented minority group. More investigation is needed in this direction in order to understand the link between perceptions of procedural and distributive justice and legitimacy of the mainstream legal system in other research settings and countries.

To sum up, this study revealed that perception of fairness, transparency, and neutrality regarding the processes by which legal decisions are taken shapes perception of legitimacy more strongly than citizens' evaluation of the final outcome or having any contact with legal authorities and institutions. Furthermore, results showed that being a member of an ethnic minority is related to the individual's perceptions of distributive justice, procedural justice, and legitimacy, with ethnic minorities generally reporting less positive perceptions. Finally, the White majority were more likely than minorities to obey the law due to their agreement with the mainstream rules and to their perception of being well represented within the law. As a whole, these findings suggest that in order to improve beliefs in the legitimacy of legal institutions, attention must be particularly focused on improving perceptions of procedural justice and promoting fair and impartial behaviour by the legal authorities. Along this line and according to Gau (2010), one way of improving perception of procedural justice would imply officers' respectfulness toward citizens during personal contacts that enhance their efficacy and impartiality in citizens' eyes.

Also, including members of the minority groups within the legal institutions as members of staff could promote their sense of social belonging and identification with mainstream norms. Along this line, Cochran and Warren (2012) have recently suggested that increasing the number of minority officers may be one viable option for improving citizen-officer relations. Although the number of ethnic minority staff working in the criminal justice agencies in most European countries has been traditionally low, it is true that in recent years there has been a marked improvement in their representation at all grades. As an example, in the United Kingdom targets were set for agencies by the Ministry of Justice to reach full representation in relation to the proportion of their staff belonging to different minority groups (Reza & Magill, 2006). When developing interventions, one should keep in mind that "The goal of democratic multiculturalism cannot and should not be cultural neutrality but, rather, the inclusion of marginal and disadvantaged groups in public life, keeping open the possibility of dialogue and mutual influence" (Modood, 1998, p. 396).

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

ARTICLE INFORMATION

Manuscript received: 02/04/2012

Revision received: 06/05/2013

Accepted: 08/05/2013

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2013a5

*Correspondence concerning this article should be sent to

EstefanĂa EstĂ©vez, Departamento de PsicologĂa de la Salud,

Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche,

Avda. Universidad s/n, Edificio Altamira, 03202 Elche, Alicante (Spain).

E-mail: eestevez@umh.es

References

Adams, J. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 267-299). New York: Academic Press.

Bayley, D. H., & Mendelsohn, H. A. (1969). Minorities and the police. Confrontation in America. New York, NY: Free Press.

Blumstein, A. (2001). Race and criminal justice. In N. J. Smelsen, W. J. Wilson, & F. Mitchell (Eds.), America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences (Vol. II, pp. 21-31). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Bobo, L. D., & Johnson, D. (2004). A taste for punishment: Black and white Americans' views on the death penalty and the war on drugs. Du Bois Review, 1 , 151-180. Doi: 10.1017/S1742058X04040081

Brunson, R. K., & Weitzer, R. (2009). Police relations with black and white youths in different urban neighborhoods. Urban Affairs Review, 44 , 858-885. Doi: 10.1177/1078087408326973

Buckler, K., & Unnever, J. D. (2008). Racial and ethnic perceptions of injustice: Testing the core hypotheses of comparative conflict theory. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36 , 270-278. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2008.04.008

Buckler, K., Unnever, J. D., & Cullen, F. T. (2008). Perceptions of injustice revisited: A test of Hagan et al.'s comparative conflict theory. Journal of Crime and Justice, 31 , 36-58. Doi: 10.1080/0735648X.2008.9721243

Buckler, K., Wilson, S., Hartley, D., & Davila, M. (2011). Racial and ethnic perceptions of injustice: Does prior personal and vicarious incarceration experience alter the racial/ethnic gap in perceptions of injustice? Criminal Justice Review, 36 , 269-290. Doi: 10.1177/0734016811409396

Chapman, B., Mirrlees-Black, C., & Brawn, C. (2002). Improving public attitudes to the criminal justice system: The impact of information. London, UK: Home Office.

Cochran, J. C., & Warren, P. Y. (2012). Racial, ethnic, and gender differences in perceptions of the police. The salience of officer race within the context of racial profiling. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 28 , 206-227. Doi: 10.1177/1043986211425726

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fagan, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2005). Legal socialization of children and adolescents. Social Justice Research, 18 , 217-242. Doi: 10.1007/s11211-005-6823-3

Flexon, J. L., Lurigio, A. J., & Greenleaf, R. G. (2009). Exploring the dimensions of trust in the police among Chicago juveniles. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37 , 180-189. Doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.02.006

Gabbidon, S. L., & Higgins, G. E. (2009). The role of race/ethnicity and race relations on public opinion related to the treatment of blacks by the police. Police Quarterly, 12 , 102-115. Doi: 10.1177/1098611108329692

Gabbidon, S. L., Higgins, G. E., & Potter, H. (2011). Race, gender, and the perception of recently experiencing unfair treatment by the police: Exploratory results from an all-black sample. Criminal Justice Review, 36 , 5-21. Doi: 10.1177/0734016810379904

Gau, J. M. (2010). A longitudinal analysis of citizens' attitudes about police. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management , 33 , 236- 252. Doi: 10.1108/13639511011044867

Hagan, J., Shedd, C., & Payne, M. R. (2005). Race, ethnicity, and youth perceptions of criminal injustice. American Sociological Review, 70 , 381-407. Doi: 10.1177/000312240507000302

Harris, D. (2002). Profiles in injustice: Why racial profiling cannot work. New York, NY: The New Press.

Johnson, R. M. A. (2007). Racial bias in the criminal justice system and why we should care. Criminal Justice, 21, 30-32.

Kennedy, R. (2001). Racial trends in the administration of criminal justice. In N. J. Smelsen, W. J. Wilson, & F. Mitchell (Eds.), America becoming: Racial trends and their consequences (Vol. II, pp. 21-31). Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Lee, Y. T., & Ottati, V. (2002). Attitudes toward U.S. immigration policy: The roles of in-group-out-group bias, economic concern, and obedience to law. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142 , 617-634. Doi: 10.1080/00224540209603922

Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In K. J. Gergen, M. S. Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 27-55). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Lin, S. P., Tang, T. W., Li, C. H., Wu, C. M., & Lin, H. H. (2007). Mediating effect of cooperative norm in predicting organizational citizenship behaviors from procedural justice climate. Psychological Reports, 101 , 67-78. Doi: 10.2466/pr0.101.1.67-78

Longazel, J. G., Parker, L. S., & Sun, I. Y. (2011). Experiencing court, experiencing race: Perceived procedural injustice among court users. Race and Justice, 1 , 202-227. Doi: 10.1177/2153368710388292

Martin, T. A., & Cohn, E. S. (2004). Attitudes toward the criminal legal system: Scale development and predictors. Psychology, Crime & Law, 10 , 367-391. Doi: 10.1080/10683160310001629265

Matsueda, R. L., & Drakulich, K. (2009). Perceptions of criminal injustice, symbolic racism, and racial politics. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623 , 163-178. Doi: 10.1177/0002716208330500

Modood, T. (1998). Anti-essentialism, multiculturalism and the 'recognition' of religious groups. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 6 , 378-399. Doi: 10.1111/1467-9760.00060

Murphy, R., Wedlock, E., & King, J. (2005). Early findings from the 2005 Home Office citizenship survey (Online report 49/05). London, UK: Home Office.

Olson, S. M., & Huth, D. A. (1998). Explaining public attitudes toward local courts. The Justice System Journal, 20, 41-61.

Page, B., Wake, R., & Ames, A. (2004). Public confidence in the criminal justice system . Findings No. 221 . London, UK: Home Office.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Bachman, R., & Sherman, L. W. (1997). Do fair procedures matter? The effect of procedural justice on spouse assault. Law & Society Review, 31, 163-204.

Reisig, M. D., & Mesko, G. (2009). Procedural justice, legitimacy, and prisoner misconduct. Psychology, Crime & Law, 15 , 41-59. Doi: 10.1080/10683160802089768

Reza, B., & Magill, C. (2006). Race and the criminal justice system: An overview to the complete statistics 2004-2005. London, UK: Criminal Justice System Research Unit. Retrieved from h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; w e b a r c h i v e & # 4 6 ; n a t i o n a l a r c h i v e s & # 4 6 ; g o v & # 4 6 ; u k & # 4 7 ; 2 0 1 1 0 2 1 8 1 3 5 8 3 2 & # 4 7 ; h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; r ds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs06/s95overview0405.pdf

Rocque, M. (2011). Racial disparities in the criminal justice system and perceptions of legitimacy: A theoretical linkage. Race and Justice, 1 , 292-315. Doi: 10.1177/2153368711409758

Roux, G., Roché, S., & Astor, S. (2011). Minorities and trust in the criminal justice. French case study. Grenoble, France: University of Grenoble. Retrieved from http://www. p a c t e - g r e n o b l e & # 4 6 ; f r & # 4 7 ; w p - c ontent/uploads/pdf_RAPPORT_EUROJUSTIS_opinion_poll_ final.pdf

Sanchez, C. G. V., & Adams, E. B. (2011). Sacrificed on the altar of public safety: The policing of Latino and African American youth. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 27 , 322-341. Doi: 10.1177/1043986211412565

Schuck, A. M., Rosenbaum, D. P., & Hawkins, D. F. (2008). The influence of race/ ethnicity, social class, and neighborhood context on residents' attitudes toward the police. Police Quarterly, 11 , 496-519. Doi: 10.1177/1098611108318115

Sherman, L. W. (2002). Trust and confidence in criminal justice. National Institute of Justice Journal, 248 , 22-31.

Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L., & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial Attitudes in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shute, S., Hood, R., & Seemungal, F. (2005). A fair hearing? Ethnic minorities in the criminal courts. Devon,UK: Willan Publishing.

Smith, P. E., & Hawkins, R. O. (1973). Victimization, types of citizen-police contacts, and attitudes toward the police. Law & Society Review, 8, 135-152.

Solis, C., Portillos, E. L., & Brunson, R. K. (2009). Latino Youths' Experiences with and Perceptions of Involuntary Police Encounters. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 623 , 39-51. Doi: 10.1177/0002716208330487

Terrill, W., & Reisig, M. D. (2003). Neighborhood context and police use of force. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 40 , 291-321. Doi: 10.1177/0022427803253800

Tyler, T. R. (2001). Public trust and confidence in legal authorities: What do majority and minority group members want from the law and legal institutions? Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 19 , 215-235. Doi: 10.1002/bsl.438

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. New York, NY: Russell Sage.

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. A. (2004). Race and perceptions of police misconduct. Social Problems, 51 , 305-325. Doi: 10.1525/sp.2004.51.3.305

Weitzer, R., & Tuch, S. A. (2005). Racially biased policing: Determinants of citizen perceptions. Social Forces, 83 , 1009-1030. Doi: 10.1353/sof.2005.0050

Wilson, C. (2012). The public and the justice system: Attitudes, drivers and behaviour a literature review. London, UK: Scottish Government Social Research.

Woodlard, J. L., Harvell, S., & Graham, S. (2008). Anticipatory injustice among adolescents: Age and racial/ethnic differences in perceived unfairness of the justice system. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 26 , 207-226. Doi: 10.1002/bsl.805

Wortley, S., Hagan, J., & Macmillan, R. (1997). Just des(s)erts? The racial polarization of perceptions of criminal injustice. Law & Society Review, 31, 637-676.

Zelditch, M. (2001). Theories of legitimacy. In J. T. Jost & B. Major (Eds.), The psychology of legitimacy: Emerging perspectives on ideology justice and intergroup relations (pp. 33-53). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

CrossRef

CrossRef