The Effect of Using Countermeasures in Interpreter-Absent and Interpreter-Present Interviews

[El efecto del uso de contramedidas en las entrevistas con ausencia y presencia de intérprete]

Aldert Vrij1, Sharon Leal1, Haneen Deeb1, Claudia Castro4, Ronald P. Fisher2, Samantha Mann1, Eunkyung Jo3, and Nael H. Alami5

1University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK; 2Florida International University, Miami, USA; 3Division of Police Administration, College of Criminal Justice, Dongguk University, Seoul, South Korea; 4Universidad Autonoma de Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico; 5Department of Public Health, Modern University for Business & Science, Beirut, Lebanon

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2022a6

Received 20 August 2021, Accepted 1 April 2022

Abstract

Background: In two experiments we examined whether lie tellers, after reading articles about the Model Statement interview tool and/or about the verbal cues complications, common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies, can successfully use countermeasures by adjusting their statements so that they sound like truth tellers. We also examined whether the presence of an interpreter affect these results. Method: In both experiments, truth tellers discussed a trip they had made; lie tellers fabricated a story. Participants were of Lebanese, Mexican and South-Korean origin. Prior to the interview participants in Experiment 1 did or did not receive information about (i) the working of the Model Statement tool and (ii) three types of verbal detail: complications, common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies. In Experiment 2 the Model Statement Pre-Information factor was replaced by the presence/absence of an interpreter. Results/Conclusions: We found no evidence that lie tellers adjusted their responses after being informed about the Model Statement and / or the types of detail we examined.

Resumen

Antecedentes: Se analiza en dos experimentos si las personas que mienten, una vez han leído artículos sobre la entrevista estándar de obtención de la declaración y auto-depreciación sobre los problemas de los indicios verbales verbales, detalles de conocimiento común y las estrategias de autojustificación pueden utilizar eficazmente contramedidas para ajustar sus declaraciones de modo que parezca que dicen la verdad. También analizamos si influye en estos resultados la presencia de un intérprete. Método: En ambos experimentos, los sujetos que decían la verdad hablaban de un viaje que habían hecho, mientras que los que mentían se inventaban una historia. Los participantes eran de origen libanés, mexicano y surcoreano. Antes de la entrevista los participantes en el experimento 1 no recibían información sobre (i) el funcionamiento de la entrevista estándar de obtención de la declaración y (ii) sobre los tres tipos de detalles verbales: complicaciones, detalles del conocimiento común y estrategias de auto-depreciación. En el experimento 2 se sustituyó el factor información previa sobre la entrevista estándar de obtención de la declaración por la presencia/ausencia de un intérprete. Resultados/Conclusiones: Los resultados nos prestaron apoyo a que los que mienten ajusten sus respuestas tras ser informados sobre la entrevista estándar de obtención de la declaración o los tipos de detalles examinados.

Keywords

Countermeasures, Information gathering, Deception, Checkable sources, PlausibilityPalabras clave

Contramedidas, Recogida de información, Engaño, Fuentes comprobables, PlausibilidadCite this article as: Vrij, A., Leal, S., Deeb, H., Castro, C., Fisher, R. P., Mann, S., Jo, E., & Alami, N. H. (2022). The Effect of Using Countermeasures in Interpreter-Absent and Interpreter-Present Interviews. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 14(2), 53 - 72. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2022a6

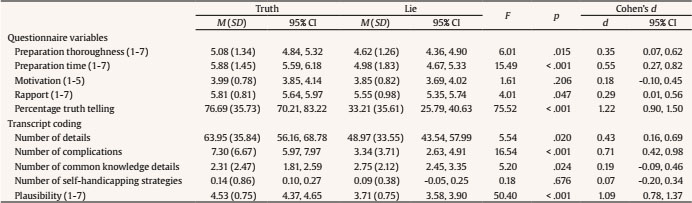

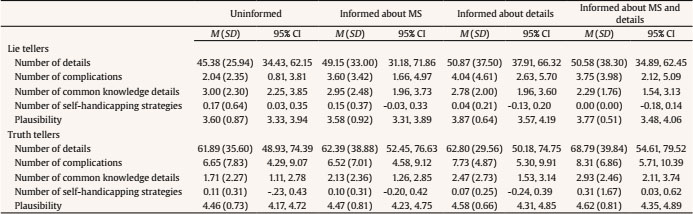

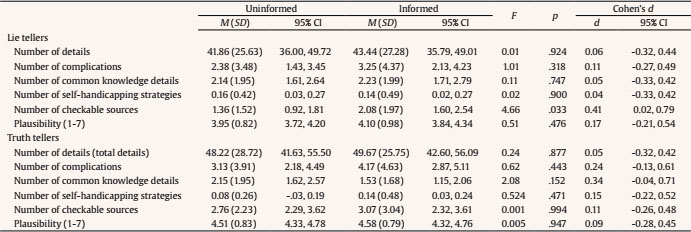

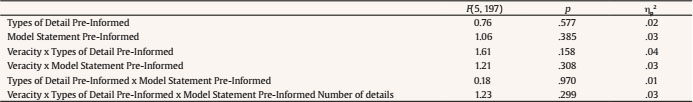

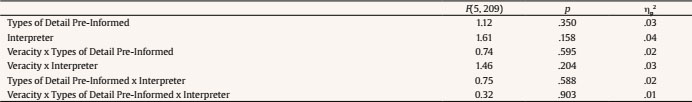

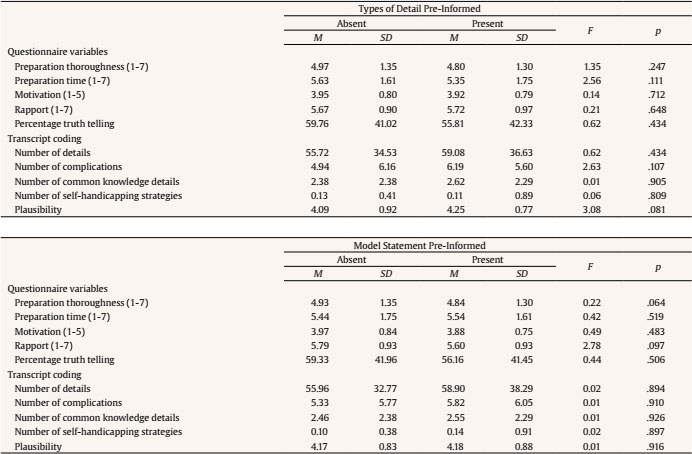

aldert.vrij@port.ac.uk Correspondence: aldert.vrij@port.ac.uk (A. Vrij).Lie tellers prepare themselves for possible interviews (Hartwig et al., 2007). One way of doing this is by searching the internet for (i) interview protocols and lie detection techniques investigators may employ and/or (ii) verbal cues they may pay attention to. This search may lead to publications about Cognitive Credibility Assessment (CCA), a widely researched verbal veracity assessment tool (Vrij, Fisher, et al., 2017). CCA includes the Model Statement interview technique (Vrij, Leal, & Fisher, 2018) and complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies as verbal cues (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Can lie tellers, after reading articles about the Model Statement interview tool and/or about these three verbal cues, successfully use countermeasures by adjusting their statements so that they sound like truth tellers? And does the presence of an interpreter affect these results? The current two experiments examine these questions. The Model Statement Interview Tool In a Model Statement interview, the interviewer gives the interviewee an example – typically presented in an audiotaped format – of a detailed account unrelated to the topic of investigation (Leal et al., 2015; Vrij, Leal, & Fisher, 2018). A Model Statement raises expectations amongst interviewees about how much information they should provide (Ewens, Vrij, Leal, Mann, Jo, Fisher, 2016) and is more effective in eliciting information than the instruction to provide details (Vrij, Leal, & Fisher, 2018). A Model Statement raises the expectations amongst both truth tellers and lie tellers about how much information they should provide (Ewens, Vrij, Leal, Mann, Jo, Fisher, 2016) and truth tellers and lie tellers provide a similar amount of additional details after listening to a Model Statement (Vrij, Leal, & Fisher, 2018). The type of detail they provide differs. For example, exposure to a Model Statement made truth tellers to report more complications (an occurrence that makes a situation more complex) than lie tellers (Deeb et al., 2020; Vrij, Leal, Jupe, et al., 2018; Vrij, Leal, et al., 2017). Complications, Common Knowledge Details, and Self-handicapping Strategies A meta-analysis of verbal and nonverbal cues to deceit revealed that such cues are typically faint and unreliable (DePaulo et al., 2003). Researchers have responded to this in several ways, including by examining new verbal cues. An example is examining complications, common knowledge detail, and self-handicapping strategies (Vrij, Leal, et al., 2017). A recent meta-analysis reported the results of more than 15 experiments in which these cues have been examined (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Complications are occurrences that affect the story-teller and make a situation more complex (“The hiking trail was wet and slippery and I fell in the mud”) (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Complications are related to the variable “unexpected complications”, which is one of the 19 criteria that constitute Criteria-Based Content Analysis (CBCA; Amado et al., 2015). In CBCA, complications are necessarily unexpected events, which is not the case in the complications variable discussed here. Truth tellers typically report more complications than lie tellers (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). First, lie tellers may not be able to report as many complications as truth tellers, because lie tellers may lack the imagination required to fabricate complications (Köhnken, 2004; Vrij, 2008). Second, lie tellers may not be willing to add complications to their stories. They prefer to keep their stories simple (Hartwig et al., 2007), but adding complications makes the story more complex. Lie tellers also believe that reporting complications makes their statements sound less sincere (Maier et al., 2018). Common knowledge details refer to strongly invoked stereotypical information about events (“We had dinner in a typical French restaurant”) (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Lie tellers report more common knowledge details than truth tellers (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Truth tellers have personal experiences of an event which they are likely to report (DePaulo et al., 1996). If lie tellers do not have personal experiences of the event, they will construe the event drawing upon their general knowledge of experiences (Sporer, 2016). In addition, adding details about personal idiosyncratic experiences goes against lie tellers’ preferred strategy to keep stories simple. Self-handicapping strategies refer to justifications as to why someone chooses not to provide information (“My memory is very poor”) (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Lie tellers report more self-handicapping strategies than truth tellers (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Not providing information is an attractive strategy for lie tellers but has as a disadvantage that it may appear suspicious (Ruby & Brigham, 1998). Providing a justification for the inability to provide information may counteract this disadvantage. Whether lie tellers will succeed in using countermeasures and sound like truth tellers will depend on how difficult it is to employ such countermeasures (Vrij, Leal et al., 2020). It is difficult for lie tellers to fabricate a statement that matches the available physical evidence. It may therefore be difficult to successfully employ countermeasures against verbal veracity tools based on physical evidence, such as the Verifiability Approach (VA; Nahari & Vrij, 2019; Vrij & Nahari, 2019) and the Strategic Use of Evidence (SUE; Hartwig et al., 2014). Indeed, informing interviewees about how the VA works (i.e., telling interviewees that the investigator would like to hear details they can verify) made the difference between truth tellers and lie tellers in reporting verifiable details larger, because truth tellers reported more additional verifiable details than lie tellers (Nahari et al., 2014b). Informing lie tellers how the SUE technique works made lie tellers to report more critical details about their activities than uninformed lie tellers, but they were still less forthcoming than truth tellers (Luke et al., 2016). Other verbal veracity assessment tools, such as Criteria-Based Content Analysis (CBCA; Amado et al., 2015; Amado et al., 2016; Köhnken & Steller, 1988; Volbert & Steller, 2014) are not based on physical evidence. Instead, they assume that truth tellers will report specific types of detail more than lie tellers. It should be easier for lie tellers to use countermeasures against such tools. Indeed, lie tellers informed about CBCA criteria sounded similar to truth tellers (Caso et al., 2006; Vrij et al., 2004; Vrij et al., 2000). Complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies are also types of detail that reflect the quality of the answers. If CBCA details are vulnerable to countermeasures, complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies should also be vulnerable to countermeasures. Perhaps particularly when interviewees are informed about the Model Statement tool, because that relates to the amount of information interviewees are expected to provide. Yet, this has not been found in a previous countermeasures experiment, because no evidence was found that lie tellers sounded like truth tellers after being informed about the Model Statement or about complications, common knowledge deetails, and self-handicapping strategies (Vrij, Leal, et al., 2020). There are at least two explanations for lie tellers failing to adjust their responses in Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020). First, the information they read about the Model Statement tool and about the three verbal criteria was not clear enough. Regarding the Model Statement tool, the information sheet did not inform participants how the Model Statement would be used. Vrij, Leal, et al. introduced it in a within-subjects format as suggested by Vrij, Leal, and Fisher (2018). That is, a first free recall was followed by a Model Statement which was followed by another free recall. We informed participants about this interview format in the Model Statement information sheet used in Experiment 1. Regarding the Types of Detail information sheet, perhaps participants did not fully comprehend the academic text. In Experiment 1, we made the text easier to understand by adding a summary sentence to the end of the document to avoid ambiguity. In summary, in a convincing story, complications are often included, whereas common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies are largely absent. A second possible reason why lie tellers failed to adjust their responses in Vrij, Leal et al. (2020) is that participants may have found it too difficult to employ countermeasures. We tried to make the task easier for participants in two ways. First, we allowed them to bring the notes they made during their preparation of the interview with them in the interview. Second, we carried out the interviews through an interpreter. In many interpreter-present interviews a consecutive interpretation style is employed (Ewens, Vrij, Leal, Mann, Jo, Fisher, 2016). The interviewee will provide a statement after which the interpreter will translate that statement. While the interpreter is speaking, interviewees have the opportunity to think what to say next, which may entail thinking about how to include complications and how to avoid common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies in their responses. In Experiment 1 we therefore replicated Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020) and made three changes: we (1) adjusted the materials participants read about the Model Statement and the types of detail and (2) allowed participants to bring in notes and (3) all interviews were carried out through an interpreter. Apart from complications, common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies, we examined two additional verbal variables often investigated in CCA: details and plausibility. Details refer to units of unique information (the sentence ‘I had a cheese sandwich for lunch’ contains three details). Truth tellers typically reporting more details than lie tellers (Amado et al., 2016). Lie tellers may be unable to fabricate many details that sound convincing (Köhnken, 2004) or may be unwilling to do so, because they may be afraid that these details will provide leads to interviewers and analysts (Nahari et al., 2014a). Plausibility refers to the question ‘how likely is it that the activities happened in the way described?’ Someone who claimed to have visited during her one-day trip to London Windsor Castle, Buckingham Palace, Tate Gallery, and Madam Tussaud is telling an implausible story, because these are too many activities to carry out in a single day. The stories of truth tellers typically sound more plausible than the stories of lie tellers (Vrij, Deeb, et al., 2020). Plausibility is not frequently measured in deception research, despite this variable being a more diagnostic veracity indicator than most other verbal cues, including those that are frequently examined, such as details (DePaulo et al., 2003; Vrij, Deeb, et al., 2020). A possible explanation for plausibility’s high diagnostic value is that it takes into account a cluster of cues. For example, it appears to be related to both complications and verifiable sources (Vrij, Deeb, et al., 2020) and also to contextual information (Blair et al., 2010). (The London visit example given above is an example of plausibility assessed through contextual information.) Evaluating statements based on a combination of diagnostic cues (e.g., complications, verifiable sources, and contextual information) is more likely to result in strong veracity indicators than evaluations based on individual cues (DePaulo et al., 2003; DePaulo & Morris, 2004; Hartwig & Bond, 2014). We predicted that lie tellers will be able to use countermeasures most effectively in a Model Statement interview when they are informed about both (i) the types of detail examined and (ii) the amount of information they are supposed to give. Experiment 1, including this hypothesis, is pre-registered at https://osf.io/knemf/ Most deception research has been carried out in the United States and Western Europe (Vrij, 2008). Practitioners often ask us whether the research findings can be applied to different cultures. To answer this question, research outside the US and Western Europe is needed (Leal et al., 2018). In the present experiment, participants from Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea took part. Method Participants The sample size was determined from an a priori power analysis. The power analysis (conducted via G*Power software) revealed that at least 200 participants are required to achieve high statistical power (.99), an alpha level of .05, and a medium effect size (f2 = .0625). We recruited a total of 209 university students (81 males and 123 females, 5 unknown). Their average age was 22.47 years (SD = 4.40). The experiment was carried out at universities in Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea and the participants were of Lebanese (n = 60), Mexican (n = 70), and Korean (n = 79) origin. Procedure Recruitment, Pre-condition Selection Form, Preparation, and Pre-Interview Questionnaire. We used the same procedure as Vrij, Leal, et al. (2017); Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020); Vrij, Leal, Fisher, et al. (2019); Vrij, Leal, Fisher, et al. (2018); and Vrij, Leal, Mann, et al. (2018). Parts of the description of the Procedure were taken from Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020) and Vrij, Leal, Fisher, et al. (2019) word by word. All study materials (recruitment material, selection form, (de)briefing forms, questionnaires, countermeasures material) were provided in the participants’ native language. Native speakers familiar with the relevant deception literature made the translations. Participants were recruited via an advert on the university intranets and advertisement leaflets distributed in university buildings. The experiment was carried out just before and during the COVID-19 outbreak. As a result, data collection in Lebanon and South Korea took place face-to-face, but in Mexico it took place online 12 months after data collection in Lebanon and South Korea was completed. We included ‘site’ as a covariate in the hypothesis-testing analyses. The advert mentioned that in the experiment participants would tell the truth or lie about a trip that they may (or may not) have made within the last year (in Lebanon and South Korea) and in the last 24 months (in Mexico). All previous experiments by Vrij and colleagues using this procedure stated “within the last year” but since many people have not travelled during the COVID outbreak we changed it to 24 months for the Mexican data collection. All study materials were presented in a hard copy format in Lebanon and South Korea and online (via Qualtrics) in Mexico. Participants first read a participant information sheet and signed an informed consent form. They then filled out a selection form that listed six cities that the researchers thought the participants may have visited during the past 12 months (Lebanon and South Korea) or past 24 months (Mexico). In each of the three countries, different cities were listed. We included these six cities on the selection form to obtain some standardisation of the cities discussed in the experiment. The participants were also asked to write down the names of two other cities they had visited during the past 12 months (in Lebanon and South Korea) or 24 months (Mexico). If truth tellers had not visited any of the six cities mentioned on the selection form in the past 12 or 24 months, they could discuss one of these two additional cities in the interview. For each city the participants reported (a) whether and (b) when they had been there during the last 12 or 24 months, (c) for how long they stayed there, and (d) whether they have lived there. For truth tellers, the experimenter selected one of the six cities where the participant had stayed during the last 12 or 24 months for at least two nights but had never lived there. If a truth teller had stayed in only one of those six cities, that particular city was chosen. If a truth teller had stayed in more than one of these six cities the experimenter chose a city that had not been discussed by (too) many truth tellers before to increase the number of cities discussed. If a truth teller had not been to any of the six cities, the experimenter selected an additional city that the truth teller had listed on the selection form. Truth tellers were told that they would be interviewed about this selected city (city X) and to be truthful when answering the questions. For lie tellers, the experimenter selected one of the six cities on the selection form where the lie teller had never been in their life before, or selected a city not on the list that was discussed by a truth teller during an interview (after checking that the lie teller had never been to this city before). Truth tellers’ and lie tellers’ cities were therefore matched. Lie tellers were told that they would be interviewed about city X pretending to have stayed there for at least two nights during a trip made during the last 12 or 24 months. The 118 truth tellers reported trips to 67 different cities. The cities lie tellers discussed were taken from this sample of 67 cities. Participants were given a computer with internet access and twenty minutes to prepare themselves for their interview. They were informed that they were allowed to make notes while doing their research and that they could bring these notes into the interview. They were further told that it was important to be convincing because they would be asked to write a statement about what they told the interviewer in the interview if they did not appear convincing. After participants indicated to be ready for their interview, they were allocated to the Model Statement Information and Types of Detail Pre-Informed conditions. Participants allocated to the Model Statement Pre-Informed Present condition were given an information sheet about the Model Statement, whereas participants allocated to the Model Statement Pre-Informed Absent condition were not. The information was taken from Leal et al. (2015) in which the Model Statement was introduced and from two articles that summarise the Model Statement tool (Vrij, Fisher, et al., 2017; Vrij, Leal, & Fisher, 2018). In sum, the information sheet informed readers that the Model Statement is an audiotaped account of a detailed report that aims to encourage interviewees to say more. It also mentioned how to use the Model Statement as a within-subjects tool, but did not refer to complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies. Vrij, Leal, and Fisher (2018) discuss these three verbal cues, but the participants were not given this information. See Appendix A for the full information sheet. Participants allocated to the Types of Detail Pre-Informed Present condition read about complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies, whereas participants allocated to the Types of Detail Pre-Informed Absent condition were not. They read parts of Vrij, Leal, Jupe, and Harvey (2018). The parts gave definitions and examples of these three variables and how they are related to deception. The Model Statement tool was not mentioned in the information sheet. Vrij, Leal, Jupe, et al. (2018) discuss the Model Statement as a within-subjects lie detection tool, but this information was not given to participants. To remove ambiguity about the relationship between the three variables and deception, we finished the information sheet with the following sentence: in summary, in a convincing story, complications are often included, whereas common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies are largely absent. (See Appendix B for the full information sheet). In a pre-interview questionnaire, thoroughness of preparation was measured via three items: (1) shallow to (7) thorough; (1) insufficient to (7) sufficient; and (1) poor to (7) good. The answers to the three questions were averaged (Cronbach’s alpha = .83). Participants were also asked whether they thought they were given enough time to prepare themselves: ‘Do you think the amount of time you were given to prepare was: (1) insufficient to (7) sufficient. Finally, participants were asked how motivated they were to perform well during the interview: (1) not at all motivated to (5) very motivated. Experimental Conditions. Participants were allocated randomly to one of the eight experimental cells: 118 participants to the truth condition and 91 to the lie condition; 105 to the Model Statement Pre-Informed absent condition and 104 to the Model Statement Pre-Informed present condition; and 103 to the Types of Detail Pre-Informed absent condition and 106 to the Types of Detail Pre-Informed present condition. The Veracity allocations were somewhat unbalanced due to an administrative error. Individual cell sizes varied from 20 to 30. The Interview. All interviews took place through interpreters. The interviewers (non-native to Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea) spoke English and the participants spoke in their native language. Interpreters (native to Lebanon, Mexico, and South-Korea) translated the text from English to the native language and vice versa. They were either professional interpreters or bilingual. The interpreters used a long consecutive interpretation style (Viezzi, 2012), similar to what was used in many previous interpreter experiments (e.g., Ewens, Vrij, Leal, Mann, Jo, Fisher, 2016; Ewens et al., 2017; Ewens, Vrij, Leal, Mann, Jo, Shaboltas, et al., 2016; Vrij, Fisher, et al., 2017; Vrij, Leal, Fisher, et al., 2019). Interpreters were asked to speak in the first person and to recall the interviewee’s response as complete as possible after the interviewee had finished answering each question. They took notes when the interviewee spoke. An alternative way of interpretation is short consecutive interpretation (translating sentence by sentence). When comparing the two interview styles, Ewens, Vrij, Leal, Mann, Jo, Fisher (2016) found no difference in the number of details translated by the interpreters. Nationality is confounded with the specific interviewer and interpreter; we therefore included “site” as a covariate in the hypotheses-testing analyses. Before the interview started, the experimenter informed the interviewer which city the participant would discuss. The interviewer offered the interviewees a glass of water. Offering something helps rapport building (reciprocation principle; Cialdini, 2007). The interviewer started by saying “I will interview you about your trip to_________. Depending on your answers, I may decide to interview you a second time so be as complete as possible when answering the questions.” This was followed by the following question: “Please tell me in as much detail as possible everything you did when you were at _________ from the moment you arrived to the moment you left.” After the response, the interviewer continued: “Thank you, I would like to ask you the questions once more, but this time, before doing so, I am going to play you a model statement to give you an example of how much detail I would like you to include in your responses.” The interviewer then played the audiotaped Model Statement used by Leal et al. (2015), a detailed account of someone attending a Formula 2 motor racing event. The account was a spontaneous and unscripted recall of an event truly experienced by the narrator. It was 1.30 minutes long. After playing the Model Statement the interviewer continued: “I will ask you the questions once more about your trip to _________ When responding to the questions, please bear in mind the amount of detail provided in the model statement you just heard. Please can you tell me again in that amount of detail everything you did when you were at _________ from the moment you arrived to the moment you left?”. The interviews were audio recorded and the text translated by the interpreter into English was transcribed. Post-interview Questionnaire. After the interview, participants completed a post-interview questionnaire. The participants indicated the extent to which they told the truth during the interview on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from 0% to 100%. The Interaction Questionnaire (Vallano & Schreiber Compo, 2011) was used to measure rapport with the interviewer. It consists of nine items rated on 7-point scales ranging from 1 = not at all to 7 = extremely. Examples are “smooth”, “bored”, “engrossed”, and “involved” (Cronbach’s alpha = .81). Participants then answered four questions about the aim of the Model Statement on 7-point Likert scales ranging from 1 = not to all to 7 = very much so: (i) “The model statement made me realise that my initial answers were not detailed enough”, (ii) “The model statement made me realise that my initial answers were too detailed”, (iii) “I think the aim of the model statement is to encourage me to say more”, and (iv) “I think the aim of the model statement is to encourage me to say less.” Participants were then given multiple choice questions to measure their knowledge about the relationship between complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, and deception. For complications the question was “Truth tellers typically report more complications than liars: (i) true, (ii) false, and (iii) I don’t know”. Similar questions were used for common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies. No definitions of complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies were given. For these three questions a total accuracy score was computed. The accuracy score could range from 0 (all three relationships incorrectly identified) to 3 (all three relationships correctly identified). Coding Detail. The raters were blind to the Veracity and Countermeasures conditions and the hypotheses. The first author, who has more than twenty years of experience in coding detail, taught them the coding scheme. Coding occurred on the English transcripts. A rater first read the transcripts and coded each detail in the interview. A detail is a unit of perceptual information about the trip the interviewee allegedly had made. For example, the following sentence has six details: “In the supermarket we purchased ingredients for pasta; we went to the hotel, took a shower, and started cooking.” Each detail in the interview was coded only once and repetitions were ignored. A second rater coded a random sample of 35 transcripts. Inter-rater agreement between the two raters, using the two-way random effects model measuring consistency, was very good (Single Measures ICC = .92). Another rater coded complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, and plausibility. Repetitions were again not coded. A complication is an occurrence that affects the story-teller and makes a situation more complex (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Example are: (a) “We went out to Seongsan Ilchulbong port to catch a boat, but there was no boat, the boat was cancelled”; (b) “The restaurant food was not enough, so we dropped by at the convenience store and purchased additional snacks”; and (c) “We had to turn around just before the top of the mountain because of the storm and rain”. Common knowledge details refer to strongly invoked stereotypical knowledge about events (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Examples are: (d) “We walked the forest trail and enjoyed the views”; (e) “Since it was August, we enjoyed the sea and swimming”; and (f) “We went back to our room, drank and enjoyed the time”. Self-handicapping strategies refer to justifications as to why someone is not able to provide information (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Examples are: (g) “We drank too much so I can’t remember how the evening ended”; (h) “I did not look around much, so I don’t remember the landscape”; and (i) “I did not book the accommodation, so I do not remember the address”. A second rater coded a random sample of 35 transcripts. Inter-rater agreement between the two raters, using the two-way random effects model measuring consistency, was very good for complications (single measures, intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC = .93), good for common knowledge details (single measures ICC = .73), and acceptable for self-handicapping strategies (single measures ICC = .65). Plausibility was defined as “How likely is it that the activities happened in the way described” (Leal et al., 2019, p. 278). It was coded on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) not plausible to (7) very plausible after each of the two questions, taking the plausibility of the previous answer into account (thus, in fact, measuring plausibility of the story as it develops). We report here the average plausibility score. The story by a participant who said that during a walk with her parents they got lost and that her parents started arguing and blaming each other for why they got lost was considered very plausible because of the detailed description of how the argument developed. In contrast, a story by a participant who went to a beach resort for a week but provided little detail by self-handicapping “I did not organise the trip and therefore did not pay much attention” was considered implausible. A second rater coded a random sample of 35 transcripts. Inter-rater agreement between the two raters, using the two-way random effects model measuring consistency, was acceptable (ICC = .66). Results Preparation Thoroughness, Preparation Time, Motivation, Rapport, and Percentage of Truth Telling A 2 (Veracity: truth vs lie) X 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed: present vs. absent) x 2 (Model Statement Pre-Informed: present vs. absent) MANOVA was carried out with preparation thoroughness, preparation time, motivation, rapport, and percentage of truth telling as dependent variables. At a multivariate level, only the Veracity effect was significant, F(5, 197) = 17.07, p < .001, ηp2 = .30. All other multivariate effects were not significant, see Appendices D and E. The Veracity univariate effects are reported in Table 1. Truth tellers found their preparation more thorough than lie tellers, were more satisfied with their preparation time, and rated their rapport with the interviewer as better than lie tellers. They also reported to have told the truth more than lie tellers. Since preparation thoroughness, preparation time, and rapport could affect participants’ verbal output, we introduced these variables as covariates in the hypothesis- testing analyses. Table 1 Statistical Results for Questionnaire Variables and Transcript Coding as a Function of Veracity in Experiment 1   The grand mean scores for preparation thoroughness (M = 4.88, SD = 1.32), preparation time (M = 5.49, SD = 1.68), and rapport (M = 5.70, SD = 0.93) (all measured on 7-point Likert scales) showed that participants thought that their preparation thoroughness and preparation time were good and that they experienced good rapport with the interviewer. The grand mean for motivation (M = 3.93, SD = 0.80) (measured on a 5-points Likert scale) shows that participants were motivated to perform well during the interview. Understanding the Provided Material A 2 (Veracity) x 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Model Statement Pre-Informed) MANOVA was carried out with the participants’ impressions of the aim of the Model Statement as dependent variables. All multivariate effects were not significant, see Appendix E. The participants correctly reported that the aim of the Model Statement was to encourage them to say more (M = 6.00, SD = 1.50) rather than less (M = 1.85, SD = 1.45). They also mentioned that the Model Statement made them realise that their initial answers were not detailed enough (M = 5.11, SD = 1.88), rather than too detailed (M = 2.75, SD = 1.75). A 2 (Veracity) x 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Model Statement Pre-Informed) ANOVA was conducted with accuracy in reporting the relationship between complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies and deception as dependent variable. Participants who did read information about the dependent variables were more accurate in reporting their relationship with deception (M = 1.75, SD = 1.00, 95% CI [1.57, 1.93]) than participants who did not read that information (M = 1.14, SD = 0.90, 95% CI [0.95, 1.33]), F(1, 200) = 20.76, p < .001, d = 0.64, 95% CI [0.35, 0.91]. All other effects were not significant, all Fs < 3.05, all ps > .081. Broken down into the three individual variables, results revealed that amongst the participants who were informed about the three variables, 71.7% reported the correct relationship between complications and deception, whereas 45.7% and 57.1% reported the correct relationship between deception and common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies. Time since the Trip was Made Truth tellers indicated on the pre-condition selection form when they made the trip they discussed. This trip was made on average 6.32 months prior to the interview. This variable was significantly correlated with common knowledge details (r = .22, p = .017); all other correlations were not significant. Hypothesis Testing A MANCOVA utilising a 2 (Veracity) x 2 (Type of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Model Statement Pre-Informed) between-subjects design was used with details, complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, and plausibility as the dependent variables. Preparation thoroughness, preparation time, rapport, and site were covariates. At a multivariate level, the analysis revealed a main effect for Veracity, F(5, 193) = 10.75, p < 001, ηp2 = .22. The univariate main effects for Veracity are presented in Table 1. Truth tellers provided more details, more complications, and fewer common knowledge details than lie tellers. Truth tellers’ stories also sounded more plausible than lie tellers’ stories. The effect sizes (d) ranged from small (common knowledge details) to very large (plausibility). All other multivariate effects were not significant, see Appendices D and E. The presence of significant Veracity main effects combined with the absence of significant interaction effects that involve the Veracity factor suggests that lie tellers were not successful in employing countermeasures, providing no support for the experimental hypothesis. To further examine this conclusion, we conducted additional analyses of covariance for lie tellers and truth tellers separately. We hereby compared the lie tellers who did read the information sheets about the Model Statement tool and/or Types of Detail (informed lie tellers) with lie tellers who did not read the information sheets (uninformed lie tellers). We did the same for truth tellers. We first carried out a one-way MANCOVA for lie tellers only. The Countermeasures factor had four levels (no information, information about Model Statement, information about Types of Detail, information about Model Statement, and Types of Detail). The dependent variables were details, complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, and plausibility; the covariates were preparation thoroughness, preparation time, rapport, and site. At a multivariate level, the Countermeasures effect was not significant, F(15, 243) = 0.82, p = .660, ηp2 = .05. None of the univariate effects were significant either: details, F(3, 83) = 0.97, p = .961, ηp2 = .004; complications, F(3, 83) = 1.04, p = .380, ηp2 = .04; common knowledge details, F(3, 83) = 0.55, p = .650, ηp2 = .02; self-handicapping strategies, F(3,83) = 1.33, p = .270, ηp2 = .05; and plausibility, F(3, 83) = 0.76, p = .522, ηp2 = .03. Table 2 shows the mean results. Table 2 Mean Scores and Standard Deviations for the Transcripts Coding as a Function of Veracity and Different Types of Countermeasures in Experiment 1   We carried out the same one-way MANCOVA for truth tellers only. At a multivariate level, the Countermeasures effect was not significant, F(15, 324) = 0.54, p = .92, ηp2 = .02. None of the univariate effects were significant either: details, F(3, 83) = 0.15, p = .931, ηp2 = .004; complications, F(3, 83) = 0.30, p = .827, ηp2 = .01; common knowledge details, F(3, 83) = 1.14, p = .337, ηp2 = .03; self-handicapping strategies, F(3,83) = 0.39, p = .748, ηp2 = .01; and plausibility, F(3, 83) = 0.34, p = .798, ηp2 = .01. Table 2 shows the mean results. These non-significant results further support the conclusion that participants did not adjust their stories after reading the information sheets. The Relationship between Plausibility and the other Verbal Output Variables Plausibility emerged as the strongest veracity indicator. Through a regression analysis we examined which other verbal output variables contributed to the plausibility ratings. A forced entry method regression analysis was carried out with details, complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies as predictors and plausibility as the outcome variable. Complications contributed to the model (β = .45, p < .001), so did common knowledge details (β = - .23, p < .001). Details (β = .00, p = 1.00) and self-handicapping strategies (β = - .04, p = .561) did not contribute to the model. The main finding in Experiment 1 was that interviewees failed to adjust their verbal responses after being informed about the Model Statement tool and/or specific types of detail, replicating Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020). We reasoned that the absence of an effect in Vrij, Leal, et al. may have been caused by lie tellers finding it too difficult to adjust their responses. We therefore gave interviewees more thinking time in Experiment 1, for example by interviewing them through an interpreter. Given that the current findings and Vrij, Leal, et al.’s findings were similar, it suggests that the presence of an interpreter had no effect on the efficacy of employing countermeasures. However, to make this conclusion more robust the effect of the presence of an interpreter should be examined within one experiment rather than by comparing the results of two experiments. We included Interpreter as a factor in the factorial design of Experiment 2. We gave participants permission to bring the notes they made into the interview. This should have made the use of countermeasures easier but lacks ecological validity because in real life interviews participants are typically not allowed to bring in notes. We did not give participants such permission in Experiment 2. The results further showed that the Model Statement information sheet was ineffective because the participants who did not read that information sheet also clearly understood the aim of the Model Statement (to encourage interviewees to say more). Including this information sheet could thus be considered redundant. In Experiment 2 we therefore focussed solely on the types of detail information. We also introduced one more dependent variable in Experiment 2: checkable sources. These are sources that can be checked to verify a statement (CCTV is a checkable source in the sentence “I went to the library around 3pm and their CCTV camera should show that”). Truth tellers typically report more checkable sources than lie tellers (Leal et al., 2018; Vrij, Leal, Deeb, et al., 2019; Vrij, Mann, et al., 2021). Truth tellers, who describe real activities, typically have more opportunities than lie tellers to back up their statements with independent evidence that can be checked. The checkable sources variable emerged from the Verifiability Approach (VA; Nahari, 2019). The main prediction of the VA is that truth tellers report more details that can be checked than lie tellers, a prediction supported in VA meta-analyses (Palena et al., 2020; Verschuere et al., 2021). Checkable sources are related to verifiable details, because a checkable source is a necessary requirement for a checkable detail and checkable sources always lead to checkable details. For example, the sentence “I went to the library around 3pm and their CCTV camera should show that” contains one checkable source (CCTV) and four checkable details (I, library, 3pm, CCTV). Sources are easier to code than details and can even be coded in real time during interviews, which enhances the applicability of the Verifiability Approach in real life interviews.

Method Participants The sample size was determined from an a priori power analysis. The power analysis (conducted via G*Power software) revealed that at least 200 participants are required to achieve high statistical power (.99), an alpha level of .05, and a medium effect size (f2 = .0625). We recruited a total of 221 university students (91 males and 129 females, 1 unknown). Their average age was 22.91 years (SD = 4.46). The experiment was carried out at universities in Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea and the participants were of Lebanese (n = 71), Mexican (n = 70), and South Korean (n = 80) origin. Procedure The procedure was identical to the Experiment 1 procedure, apart from the following seven differences:

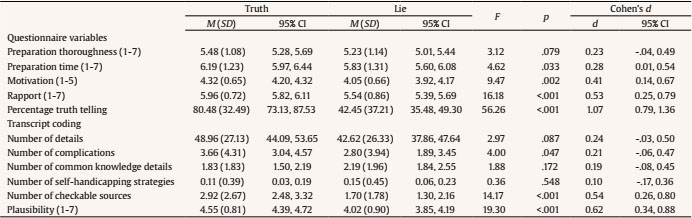

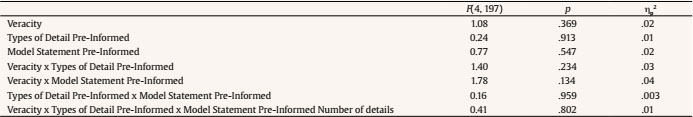

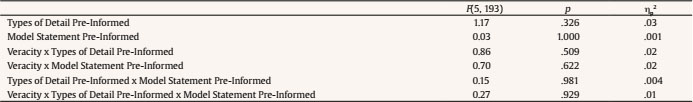

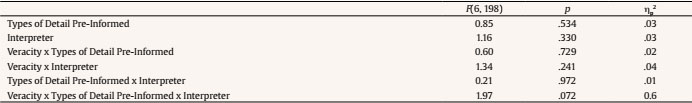

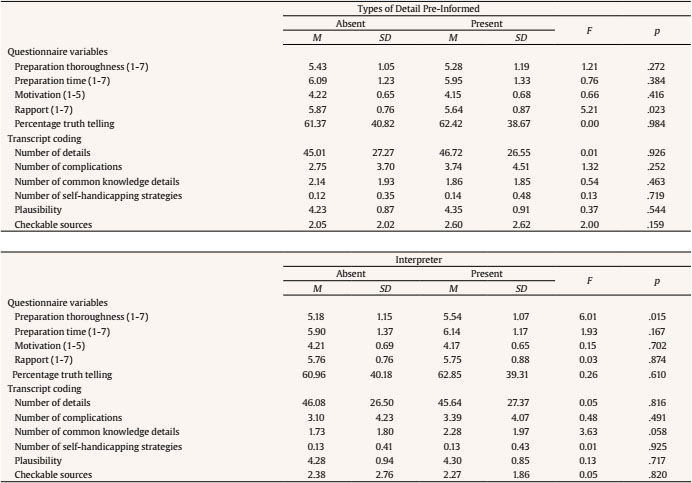

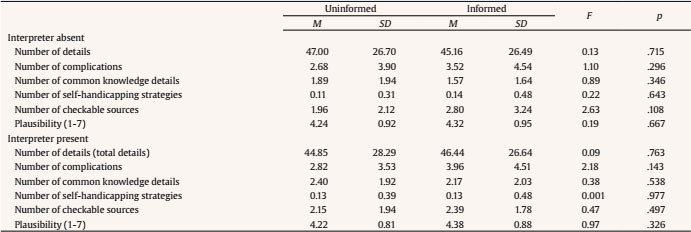

Experimental Conditions. Participants were allocated randomly to one of the eight experimental cells: 113 participants to the truth condition and 108 to the lie condition; 111 to the Types of Detail Pre-Informed absent condition and 110 to the Types of Detail Pre-Informed present condition; and 112 to the Interpreter-absent condition and 109 to the Interpreter present condition. Individual cell sizes varied from 26 to 30. Pre-interview Questionnaire. In the pre-interview questionnaire, the answers to the three items rating participants’ thoroughness of preparation were again averaged (Cronbach’s alpha = .86). The Interview. The interviewers in the Interpreter-absent conditions came from the same countries as their interviewees (Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea) and the interviews took place in their native languages. The interviewers in the Interpreter-present conditions were not native to Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea and spoke English in the interviews. Interpreters (native to Lebanon, Mexico, and South Korea) translated the text from English to the native language and vice versa. They were either professional interpreters or bilingual. Identical to Experiment 1, the interpreters used a long consecutive interpretation style (Viezzi, 2012). Since nationality is confounded with the specific interviewer and interpreter, we included “site” as a covariate in the hypotheses-testing analyses. Prior to the interview, the experimenter told the interviewer which city the interviewee would discuss. Interviewees were offered a glass of water by the interviewer, as offering something helps rapport building (reciprocation principle, Cialdini, 2007). The interviewer started by saying “I will interview you about your trip to_________. Depending on your answers, I may decide to interview you a second time so be as complete as possible when answering the questions.” This was followed by the following five questions which were always asked in the same order: (1) “Please tell me in as much detail as possible everything you did when you were at _________ from the moment you arrived to the moment you left”; (2) “Tell me in as much detail as possible about your accommodation where you stayed, including the location and address if you can remember, and what amenities (e.g., shops, restaurants, gyms) were nearby”; (3) “Tell me in as much detail as possible everything you did to plan this trip in terms of organising where to visit and so on”; (4) “Tell me in as much detail as possible everything you did to plan this trip in terms of organising transport and accommodation”; and (5) “Finally, thinking about what you just told me, can you think of ways in which I can check the details you have told me. For example, this could be names/telephone numbers of witnesses, receipts, emails or photographs – basically anything I can check?”. The 113 truth tellers reported trips to 42 different cities. The cities lie tellers discussed were taken from this sample of 42 cities. The interviews were audio recorded. In the interpreter-absent interviews the Arabic, Spanish, and Korean text was transcribed and then translated into English. In the interpreter-present interviews the English text spoken by the interpreter during the interview was transcribed. Post-interview Questionnaire. The nine items on the Interaction Questionnaire (Vallano & Schreiber Compo, 2011) were averaged (Cronbach’s alpha = .72). Coding Detail. The same raters as in Experiment 1, blind to the Veracity and Countermeasure conditions and the hypotheses, were used. Coding occurred on the English transcripts. One rater coded each detail in the interview, not coding any repetitions. The second rater coded a random sample of 57 transcripts. Inter-rater agreement between the two raters, using the two-way random effects model measuring consistency, was very good (single measures ICC = .95). Another rater coded complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, checkable sources, and plausibility. Repetitions were not coded. Checkable sources (which were not coded in Experiment 1) are named persons who witnessed the activities, photos, receipts, etc. (Palena et al., 2020). Examples are: “I have the photos on my mobile phone”; “I have an email with my hotel confirmation”; and “I have the payment history on my phone”. A second rater coded a random sample of 73 transcripts. Inter-rater agreement between the two raters, using the two-way random effects model measuring consistency, was good for all measures: complications (Single Measures, Intraclass correlation coefficient, ICC = .91), common knowledge details (Single Measures ICC = .69), self-handicapping strategies (Single Measures ICC = .74), and checkable sources (Single Measures ICC = .94). One rater coded the plausibility of all transcripts on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) not plausible to (7) very plausible after each of the five questions, taking into account the plausibility of the previous answers (thus, in fact, measuring plausibility of the story as it develops). We report here the average plausibility score. A second rater coded a random sample of 73 transcripts. Inter-rater agreement between the two raters, using the two-way random effects model measuring consistency, was acceptable (ICC = .66). Results Preparation Thoroughness, Preparation Time, Motivation, Rapport, and Percentage of Truth Telling A 2 (Veracity: truth vs lie) x 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed: present vs absent) x 2 (Interpreter: present vs absent) MANOVA was carried out with preparation thoroughness, preparation time, motivation, rapport, and percentage of truth telling as dependent variables. At a multivariate level only the Veracity main effect was significant, F(5, 209) = 16.58, p < .001, ηp2 = .28. All other multivariate effects were not significant, see Appendices F and G. The statistical analyses for Veracity are presented in Table 3. Truth tellers believed more than lie tellers that they were given sufficient time to prepare themselves for the interview. Truth tellers also reported higher motivation levels and a better rapport with the interviewer than lie tellers. Truth tellers also reported to have been more truthful than lie tellers. Table 3 Statistical Results for Questionnaire Variables and Transcript Coding as a Function of Veracity in Experiment 2   Participants in the interpreter-present condition rated their preparation as more thorough than participants in the interpreter-absent condition (see Appendix F). Since preparation thoroughness, preparation time, motivation, and rapport may affect participants’ verbal output, we introduced these variables as covariates in the analyses where we examined verbal output. The grand mean scores for preparation thoroughness (M = 5.36, SD = 1.12), preparation time (M = 6.02, SD = 1.28), and rapport (M = 5.75, SD = 0.82) (measured on 7-point Likert scales) indicated that participants thought that their preparation thoroughness and preparation time were good and that they experienced good rapport with the interviewer. The grand mean for motivation (M = 4.19, SD = 0.67) (measured on 5-point Likert scale) shows that participants were motivated. Accuracy in Reporting the Relationship between Complications, Common Knowledge Details, and Self-handicapping Strategies and Deception A 2 (Veracity) x 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Interpreter) ANOVA was carried out with accuracy in reporting the relationship between complications, common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies and deception as dependent variable. The statistical analysis is presented in Appendix C. Participants who did read information about the dependent variables were more accurate in reporting the correct relationship between these variables and deception than participants who did not read that information. Broken down into the three individual variables, results revealed that amongst the participants who were informed about the three variables, 67.3% reported the correct relationship between complications and deception, whereas 62.7% and 62.7% reported the correct relationship between deception and common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies. Time since the Trip was Made Truth tellers reported on the pre-condition selection form when they made the trip they discussed. This trip was made on average M = 12.74 months prior to the interview (SD = 6.86). This variable was not significantly correlated with any of the six verbal output variables. Hypothesis Testing A MANCOVA utilizing a 2 (Veracity) x 2 (Type of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Interpreter) between-subjects design was used with details, complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, checkable sources, and plausibility as the dependent variables. Preparation thoroughness, preparation time, motivation, rapport and site were covariates. At a multivariate level, the analysis revealed a main effect for Veracity, F(6, 203) = 4.22, p = .001, ηp2 = .11. The univariate main effects for Veracity are presented in Table 3. Truth tellers provided more complications and more checkable sources than lie tellers. Truth tellers’ stories also sounded more plausible than lie tellers’ stories. The effect sizes (d) ranged from small (complications) to medium (checkable sources and plausibility). The effect for details was marginally significant, with truth tellers reporting more details than lie tellers. All other multivariate effects were not significant (see Appendices F and G). These findings provide partial support for Hypothesis 1 but do not support Hypotheses 2 and 3. The presence of significant Veracity main effects combined with the absence of significant interaction effects that involve the Veracity factor suggests that lie tellers were not successful in employing countermeasures. To further examine this conclusion, we conducted additional analyses of covariance for lie tellers and truth tellers separately. We hereby compared the lie tellers who did read the information sheet about complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies (informed lie tellers) with lie tellers who did not read this informed sheet (uninformed lie tellers). We did the same for truth tellers. We carried out a 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Interpreter) MANCOVA for lie tellers only with details, complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, checkable sources, and plausibility as dependent variables, and preparation thoroughness, preparation time, motivation, rapport, and site as covariates. At a multivariate level, the Type of Detail Pre-Informed main effect, F(6, 94) = 1.15, p = .338, ηp2 = .07; the Interpreter main effect, F(6, 94) = 0.58, p = .736, ηp2 = .04; and the Type of Detail Pre-Informed x Interpreter interaction effect, F(6, 94) = 0.83, p = .552, ηp2 = .05, were non-significant. Table 4 shows the statistical results for the Types of Detail Pre-Informed factor. One significant effect emerged: informed lie tellers reported more checkable sources than uninformed lie tellers. For the Interpreter main effect and Type of Detail Pre-Informed x Interpreter interaction effect none of the univariate effects were significant (see Appendix H). We carried out a 2 (Types of Detail Pre-Informed) x 2 (Interpreter) MANCOVA for truth tellers only with details, complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, checkable sources, and plausibility as dependent variables, and preparation thoroughness, preparation time, motivation, rapport, and site as covariates. At a multivariate level, the Type of Detail Pre-Informed main effect, F(6, 99) = 0.75, p = .609, ηp2 = .04; the Interpreter main effect, F(6, 99) = 20.5, p = .066, ηp2 = .11; and the Type of Detail Pre-Informed x Interpreter interaction effect, F(6, 99) = 1.09, p = .376, ηp2 = .06, were not significant. Table 4 shows the statistical results for the Types of Detail Pre-Informed factor. None of the effects were significant. For the Interpreter factor, a significant univariate effect emerged for common knowledge details, F(1, 104) = 5.27, p = .024, d = 0.44, 95% CI [0.06, 0.81]. The Interpreter-present interviews resulted in more common knowledge details (M = 2.24, SD = 1.89, 95% CI [1.77, 2.69]) than the Interpreter-absent interviews (M = 1.45, SD = 1.71, 95% CI [1.02, 1.92]). All other univariate Interpreter main effects and Type of Detail Pre-Informed x Interpreter interaction effects were not significant (see Appendix H). Table 4 Statistical Results for the Transcript Coding as a Function of Veracity: Comparisons between Uninformed and Informed Participants in Experiment 2   The Relationship between Plausibility and the Other Verbal Output Variables Through a regression analysis we examined which other verbal output variables contributed to the plausibility ratings. A regression analysis using a forced entry method was used with details, complications, common knowledge details, self-handicapping strategies, and verifiable sources as predictors and plausibility as the outcome variable. The model explained R2 = 54% of the variance. Complications contributed to the model (β = .35, p < .001), so did checkable sources (β = .27, p < .001), common knowledge details (β = -.27, p < .001), and self-handicapping strategies (β = -.25, p < .001). Only details did not contribute to the model (β = .004, p = .054). Discussion Being informed about complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies had no effect on the frequency of occurrence of these variables in lie tellers’ statements. This finding, combined with the finding that complications emerged in the experiment as a veracity indicator, suggests that lie tellers failed to adjust their stories to sound like truth tellers. This replicates the Experiment 1 findings and the findings obtained by Vrij, Leal et al. (2020). It could be that lie tellers did not believe the information they read, because they typically believe that reporting complications raises suspicion (Maier et al., 2018). There is indirect evidence for this suspicion. Only 67.3% of the participants who had read the information about the relationship between complications and deception reported the correct relationship in the post-interview questionnaire. Similar percentages were obtained in Experiment 1 (71.6%) and by Vrij, Leal et al. (2020) in their experiment (66.3%). Another explanations why the countermeasures were not successfully employed is that the information sheet was too difficult to grasp for participants or that it was too difficult for them to adjust their stories according to the provided information. Regarding the latter explanation, to make the task easier we interviewed half of the participants through an interpreter. We argued that this would give participants thinking time what to say next when the interpreter translates their previous responses. However, the presence of an interviewer had no effect. Perhaps this was due to the type of interpretation we used. We used in both Experiments 1 and 2 a long consecutive interpretation style where the interpreter makes notes and gives an account as complete as possible of the interviewee’s response after the interviewee had finished answering each question. Participants will have more thinking time in a short consecutive interpretation style where the interpreter translates sentence by sentence. Future research could examine this. In summary, Experiments 1 and 2 and Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020) found that complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies were resistant against countermeasures. We think this is a remarkable finding because it sounds reasonable that participants will be able to adjust their stories after being informed about such variables, even more so because participants were given a good opportunity to learn about these variables: They were given a part of an article to read that was entirely focused on these three variables. One could argue that asking participants to read information about complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies does not reflect real life. Instead, in real life people search the internet to learn more about lie detection methods. We believe the chance to be small that such a search will lead to articles describing these three variables because the internet is dominated by information about nonverbal lie detection methods. We believe that people who search the internet for cues to deceit will focus on nonverbal cues to deceit. This is an empirical question worth exploring. Significant veracity effects emerged for details, complications, common knowledge details, and plausibility in Experiment 1 and for complications, checkable sources, and plausibility in Experiment 2. Complications therefore emerged as a more diagnostic veracity indicator than common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies, which is a typical finding (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). Complications is a cue to truthfulness (truth tellers report more complications than lie tellers), whereas common knowledge details and self-handicapping strategies are cues to deceit (lie tellers report them more than truth tellers). Verbal lie detection is dominated by cues to truthfulness, with the inconsistency cues measured in SUE being an important exception (Hartwig et al., 2014). Verbal lie detection would benefit from cues to deceit (Nahari et al., 2019). At present, lying is largely defined by the absence of cues to truthfulness. Using the absence of a signal as the presence of a phenomenon is a difficult task to perform. It would be easier to detect lies by identifying the presence of cues to deceit (Vrij et al., 2022). Investigators could be more certain that someone is lying if the absence of cues to truthfulness would be accompanied by the presence of cues to deceit (Nahari et al., 2019; Vrij, 2016). Examining cues to deceit should therefore have priority amongst researchers (Nahari et al., 2019; Vrij et al., 2022). In Experiment 2, complications was not as strongly related to deception as typically found in research. The effect size in Experiment 2 was d = 0.21 compared to d = 0.65 in Experiment 1. Also, in Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020) stronger effect sizes for complications (d scores ranged from 0.33 to 0.63) were obtained than in Experiment 2. Finally, an average of g = 0.58 was obtained in a meta-analysis including 18 experiments (Vrij, Palena, et al., 2021). We can only speculate about the relatively weak results for complications in Experiment 2. First, it could be the result of online interviewing. Perhaps participants are less likely to report complications in online interviews than in face-to-face interviews. This is an empirical question worth investigating, given the likely increase of online interviewing in the future because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, it could be the result of delayed interviewing. Truth tellers in Experiment 2 reported a trip that they made on average 12 months before the interview compared to 6 months in Experiment 1 and 5.5 months in Vrij, Leal, et al. (2020). Perhaps during those 12 months truth tellers forgot many complications they experienced during their trips. Third, the stories the participants told in Experiment 2 were rather uneventful, due to COVID-19 restrictions that were in place in the cities they visited. Many attractions, restaurants, and bars were closed and there was little to do for the participants during their stays. A lack of activities leads to a lack of complications to report. Checkable sources – examined only in Experiment 2 – emerged as a veracity indicator, providing more evidence that examining this variable has potential for lie detection. Typically, in the Verifiability Approach verifiable details rather than checkable sources are examined (Palena et al., 2021). The Verifiability Approach has been examined in various settings, but mostly in criminal and insurance settings (Palena et al., 2021). This is the second experiment in which it was examined in a travel setting and in the first experiment checkable sources also emerged as a veracity indicator (Vrij, Leal, Deeb, et al. (2019). The Verifiability Approach thus also seems to be an efficient veracity assessment tool in travel settings. In Experiment 2, lie tellers adjusted their responses after reading about complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies by reporting more checkable sources. This is a peculiar finding because the information they read did not refer to checkable sources at all. It suggests that lie tellers after being informed about complications, common knowledge details, and self-handicapping strategies thought that they needed to do something to appear credible. Mentioning checkable sources was not the best decision for them to make. Since lie tellers did not visit the cities they claimed to have visited, they would have no opportunity to back up their stories with photos, receipts, witnesses, etc. Their lies would fall through if investigators would ask them to show the checkable sources they mentioned in the interview. Plausibility emerged as the strongest veracity indicator in both Experiments 1 and 2, replicating previous plausibility research (Vrij, Deeb, et al., 2020). The regression analyses in Experiments 1 and 2 examining the relationships between plausibility and the other verbal output variables showed overlap. In both experiments, plausibility was positively associated with complications and negatively associated with common knowledge details. A negative association between plausibility and self-handicapping strategies only occurred in Experiment 2. Plausibility was also positively associated with checkable sources in Experiment 2, a variable that was not examined in Experiment 1. The findings for complications and checkable sources replicate previous research (Vrij, Deeb, et al., 2020) and brings us one step further to determine what plausibility entails. In neither experiment did the details variable contribute to plausibility. It was thus the quality of details (e.g., complications and checkable sources) reported rather than the quantity of details (e.g., details) that influenced the plausibility ratings. The explained variance in the regression analyses was somewhat low in Experiment 1 (27%) but much higher in Experiment 2 (54%). The difference in explained variance between Experiments 1 and 2 could have been caused by checkable sources, because that was an important predictor variable in Experiment 2 but not measured in Experiment 1. More variance could probably be explained when contextual information would be taken into account. Blair et al. (2010) distinguished between two forms of contextual information: first, a comparison between the statement and independent evidence such as CCTV footage (statements that contradict independent evidence are considered implausible), and second, an evaluation of the statement in terms of what is conventional or reasonable in the given situation (unconventional or unreasonable activities, such as too many activities carried out in one day, are considered implausible). Contextual information could be examined in future plausibility research. Plausibility is typically neglected by verbal lie detection researchers. One explanation is that they find the concept vague: What is plausibility? Experiments 1 and 2 showed that the inter-rater agreement for measuring plausibility was not high but certainly acceptable, suggesting that different people can have shared views about this cue. It is unfortunate that in the verbal lie detection field where strong veracity indicators are scarce, a cue that seems to work is neglected. The field can hardly afford neglecting potentially strong cues and we thus encourage fellow researchers to start examining plausibility and to give this veracity indicator the attention it deserves. Perhaps researchers could start examining how to define plausibility better, for example, by informing raters what clusters of variables are typically related to plausibility. Another option for research is trying to increase the explained variance when predicting plausibility ratings, for example by examining variables that may be related to plausibility, such as contextual information. The details variable was not a significant veracity indicator in Experiment 2. This is unusual because it often emerges as a veracity indicator (Amado et al., 2016; DePaulo et al., 2003; Vrij, 2008). Same as for complications, perhaps also details is more likely to be a veracity indicator in face-to-face than in online interviews. This is an empirical question worth exploring. Alternatively, the absence of a Veracity effect could have been caused by the rather long (average of 12 months) time delay between truth tellers having experienced their trip and reporting it. Differences in reporting details between truth tellers and lie tellers become smaller over time due to a combination of the forgetting curve that affects truth tellers (memory is becoming worse over time) and the stability bias that affects lie tellers (overestimating of truth tellers’ memory) (Harvey et al., 2017; Harvey et al., 2020; Harvey et al., 2019). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Funding: This work is funded by the High-Value Detainee Interrogation Group, DJF-15-1299-V-0010271 awarded to the University of Portsmouth (UK). Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Government. Cite this article as: Vrij, A., Leal, S., Deeb, H., Castro, C., Fisher, R. P., Mann, S., Jo, E., & Alami, N. (2022). The effect of using countermeasures in interpreter-absent and interpreterpresent interviews. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 14(2), 53-72. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2022a6 References Appendix A The Model Statement Information Sheet Specific interview techniques have been developed that make lie detection easier because truth tellers and liars respond differently when exposed to these techniques. To what extent can a liar who learns about the techniques successfully adjust her/his responses so that they sound like a truth teller? In this document you will find information about one such technique, the model statement technique. Please read this information carefully because in the interview you will be exposed to the model statement technique. This document consists of three parts: The first part Interviewing to detect deception contains some general information about lie detection techniques that successfully discriminate truth tellers from liars. The second part Encouraging interviewees to provide more information gives a little bit more information about the general approach we will use in the interview you will have after reading this document. The third part A model answer (model statement) outlines the specific approach we will use in the interview: The model statement technique. It contains: