Interaction of Parental Discipline Strategies and AdolescentsŌĆÖ Personality Traits in the Prediction of Child-to-Parent Violence

[Interacci├│n entre estrategias de disciplina parental y rasgos de personalidad de los adolescentes en la predicci├│n de la violencia filioparental]

Aitor Jiménez-Granado, Joana del Hoyo-Bilbao, and Liria Fernández-González

University of Deusto, Bilbao, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2023a5

Received 25 October 2022, Accepted 30 December 2022

Abstract

Background: Child-to-parent violence is a family issue that needs a systemic and integral approach for its evaluation. The main objective of this longitudinal study was to assess the moderating effects of adolescents’ borderline personality and psychopathic traits (grandiose-manipulative, callous-unemotional, and impulsive-irresponsible dimensions) in the predictive association between inadequate parental strategies (psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and ignoring misbehavior) and child-to-parent violence. Sex differences were analyzed. Method: The community sample comprised 671 adolescents aged from 12 to 17 years old (Mage = 13.39, SD = 1.15; 50.8% girls, 47.7% boys, and 1.5% non-binary), assessed twice, six months apart from each other. Results: Results showed slightly different patterns of violence towards fathers and mothers – ignoring misbehavior predicted aggression toward mothers, while psychological aggression predicted aggression toward fathers. Moderation analyses showed that the predictive association from ignoring misbehavior to both child-to-father violence (CFV) and child-to-mother violence (CMV) was only significant for adolescents who were high in the psychopathic trait of callous-unemotional, and the predictive association from psychological aggression to CFV was only significant in those adolescents who scored low in the borderline personality trait. Some sex specificities emerged. Conclusions: These findings support the relevance of working on parents’ discipline strategies and add the need to work on adolescents’ emotional regulation to prevent or deal with child-to-parent violence.

Resumen

Antecedentes: La violencia filioparental (VFP) es una problemática familiar cuya evaluación requiere una perspectiva sistémica e integral. El objetivo principal de este estudio longitudinal fue evaluar los efectos moderadores de los rasgos límite y psicopáticos (dimensiones grandiosa-manipulativa, fría-insensible e impulsiva-irresponsable) en adolescentes en la relación predictiva entre estrategias inadecuadas parentales (agresión psicológica, castigo físico e ignorar el mal comportamiento) y la VFP. Se analizaron diferencias por sexo de los adolescentes. Método: La muestra comunitaria estuvo compuesta por 671 adolescentes, de edades comprendidas entre 12 y 17 años (Medad = 13.39, SD = 1.15; 50.8% chicas, 47.7% chicos y 1.5% no binarios), evaluadas en dos momentos con seis meses de diferencia. Resultados: Los resultados mostraron patrones ligeramente diferentes en la violencia hacia padres y madres: ignorar el mal comportamiento predijo la violencia hacia los madres, mientras que la agresión psicológica predijo la la violencia hacia los padres. Los análisis de moderación mostraron que la asociación predictiva entre ignorar el mal comportamiento y la violencia hacia ambos progenitores era significativa solo en adolescentes con rasgos elevados de frialdad emocional y que la relación predictiva entre agresión psicológica y violencia hacia el padre fue significativa solamente en adolescentes con bajos niveles de rasgos límite. Se observaron algunas especificidades según el sexo de los adolescentes. Conclusiones: Estos resultados abundan en la importancia de trabajar en las estrategias de disciplina parentales y en la regulación emocional de los adolescentes en la prevención de la VFP o en su intervención.

Keywords

Child-to-parent aggression, Psychopathic traits, Borderline personality traits, Parental discipline strategies, AdolescentsPalabras clave

Violencia filioparental, Rasgos psicop├Īticos, Rasgos l├Łmite de personalidad, Disciplina parental, AdolescentesCite this article as: Jiménez-Granado, A., Hoyo-Bilbao, J. D., & Fernández-González, L. (2023). Interaction of Parental Discipline Strategies and AdolescentsŌĆÖ Personality Traits in the Prediction of Child-to-Parent Violence. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 15(1), 43 - 52. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2023a5

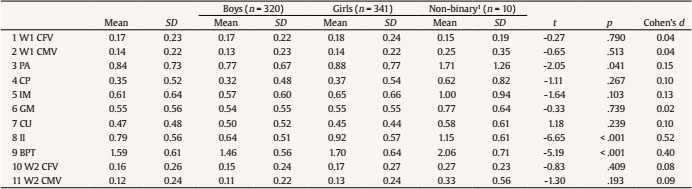

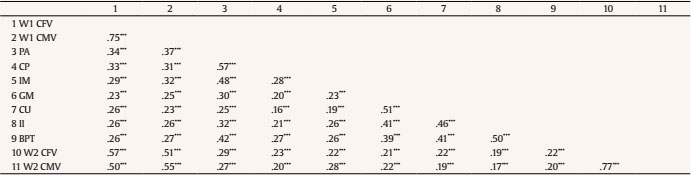

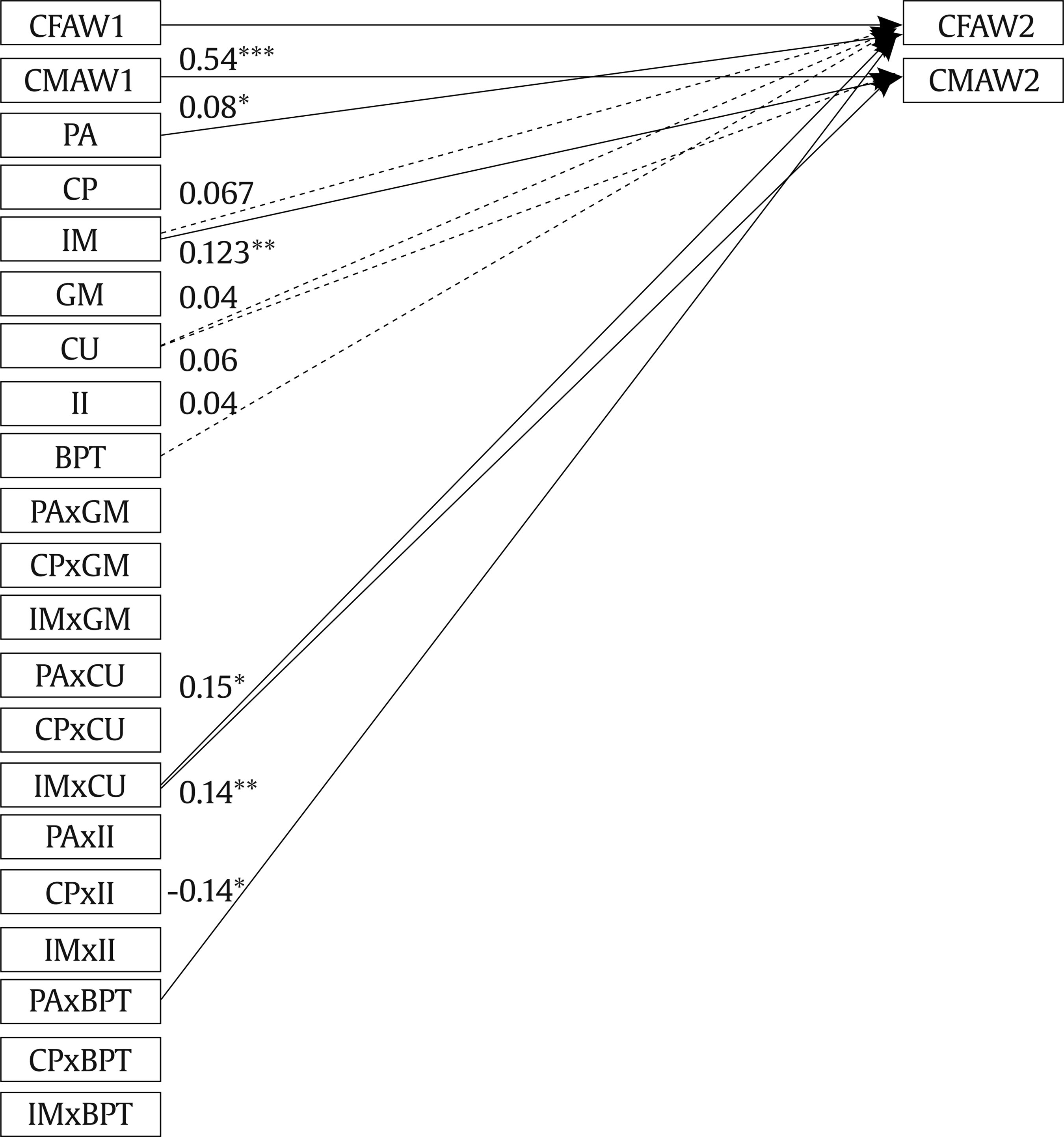

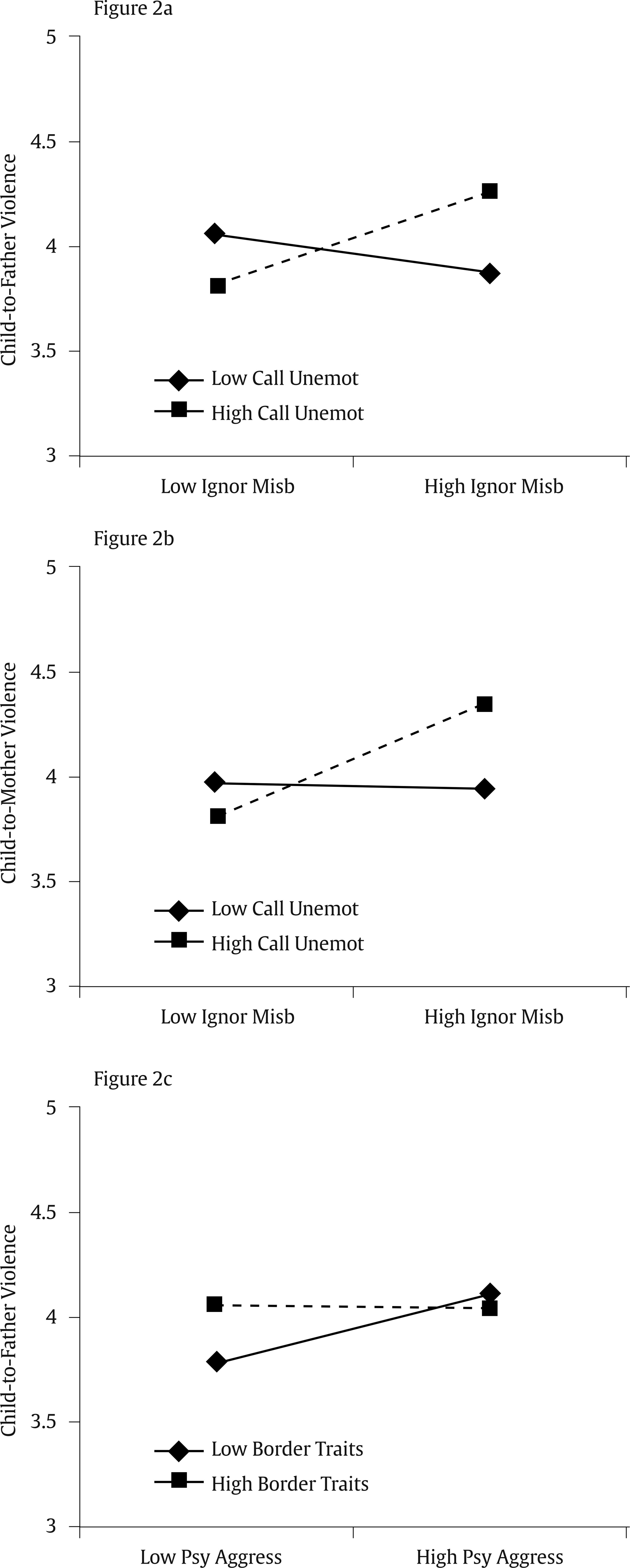

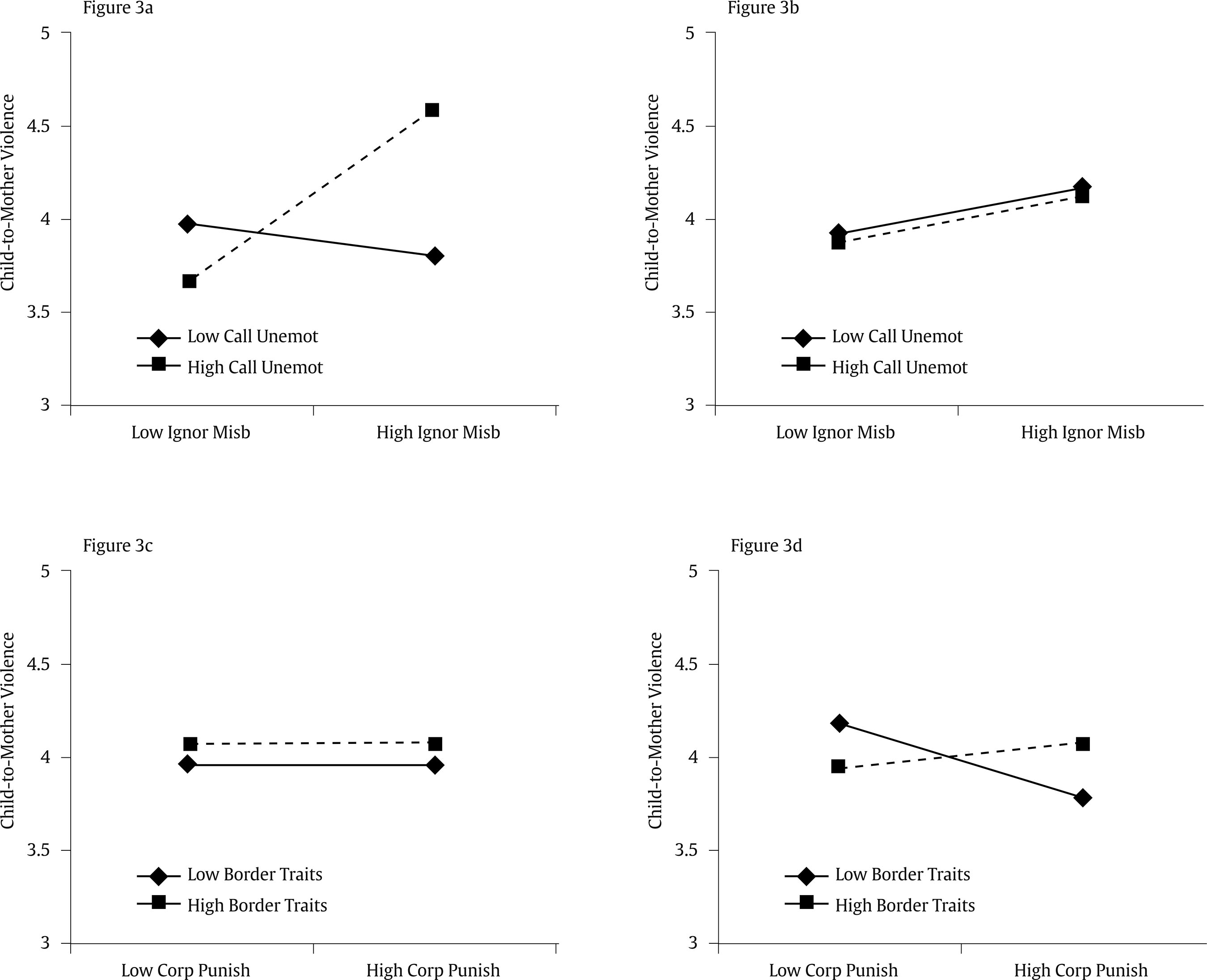

Correspondence: aitor.jimenez@deusto.es (A. Jim├®nez-Granado).Child-to-parent violence (CPV) is repeated behaviors of physical, psychological (verbal or non-verbal), or economic violence directed toward parents or primary caregivers. Specific attacks, attacks amid a mental breakout, or murders without previous violence would be excluded from this definition (Pereira et al., 2017). Despite its prevalence and negative consequences both for adolescents’ emotional well-being and family relationships (Kennair & Mellor, 2007), the topic remains understudied and less visible than other forms of family violence, such as intimate partner violence or child abuse (Condry & Miles, 2014; Gallego et al., 2019). Prevalence rates in community studies vary widely depending on the criteria used to define CPV (i.e., one unique behavior or a repeated pattern) and across countries: in Chile, 82.2% of the adolescents declared psychological aggressions at least once in the last year, 52.2% financial abuse, and 20% physical aggressions (Ilabaca-Baeza & Gaete-Fiscella, 2021); in Spain, a recent study found that 68.2% of the adolescents reported to perform at least one CPV behavior to their parents (mainly, insulting) (Cortina & Martín, 2022); in Germany, 45.3% of the adolescents reported at least one psychological aggression in the last year and 5.5% reported physical aggression. Moreover, findings of previous studies suggest different prevalence rates when considering parents’ sex, where mothers are more often the target of these behaviors than fathers (Calvete & Orue, 2016). Despite challenges in the area, there is a broad consensus among researchers on the social concern regarding CPV, focusing on family dynamics (Cottrell & Monk, 2004; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020). Parental styles, such as authoritarian and negligent styles, have been related positively to CPV behaviors (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012), while authoritative and indulgent styles have been related negatively (Suárez-Relinque et al., 2019). In addition, some discipline specific strategies, mainly linked to authoritarian parental styles, have been addressed: correlational (Beckmann et al., 2021) and longitudinal (Pagani et al., 2004, 2009) studies have found a positive association of parents’ psychological aggression and CPV behaviors. In the case of corporal punishment, results are more inconclusive: some cross-sectional studies have found an association between concurrent corporal punishment and CPV (Beckman et al., 2021; Ibabe et al., 2013) and a direct association of corporal punishment with CPV towards mothers, but not fathers (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020). In the same line, a longitudinal study found an association of corporal punishment and physical CPV behaviors towards mothers, but not fathers (Pagani et al., 2004, 2009), what may rely on previous mothers’ physical punishment (Margolin & Baucom, 2014). In addition, while Margolin and Baucom (2014) found an association of previous corporal punishment to physical but not verbal CPV, another longitudinal study found the opposite results (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2018). Therefore, it is not clear whether corporal punishment associates directly with or might be moderated by other mechanisms, such as adolescents’ individual features. However, strategies linked to negligent parental styles, such as ignoring misbehavior or lack of supervision, have had smaller attention from researchers, where just one correlational study considered and related them to CPV behaviors (Ibabe, 2015), but as part of coercive strategies. Finally, other studies focused on the way implementing discipline is displayed, for instance, parental warmth protects (Cano-Lozano et al., 2020), while the lack of it enhances the development of CPV behaviors (Calvete et al., 2015). Although more longitudinal studies centered on specific strategies are needed to establish conclusions in the predictive relationships between parental discipline and CPV, in general, the role of family variables in the origin of CPV is already well-established. Nonetheless, not all children and adolescents raised in abusive and/or neglectful family environments behave aggressively toward their parents (Gallego et al., 2019). The interaction of risk family situations with other variables, such as adolescents’ personality features, could be essential to understand the final behavior of adolescents. Although the interactions between discipline strategies and adolescents’ individual characteristics in association to CPV have not specifically been examined, findings of a few studies on aggressive behavior in adolescence suggest that the interaction of certain discipline strategies with individual characteristics of adolescents may be related to the development of CPV. For example, one study indicated that parental rejection and punishment in interaction with narcissism and Machiavellianism (Yendell et al., 2022) or parental monitoring with callous-unemotional traits (Muñoz et al., 2011) were associated with aggressive conduct in adolescence. In addition, some adolescents’ traits are related to CPV. In particular, impulsiveness has been related to CPV in previous community cross-sectional (Rico et al., 2017) and longitudinal studies (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020). Moreover, lower self-esteem and empathic traits in adolescents convicted due to CPV compared to those judicialized under other charges (Contreras & Cano, 2015) and higher antisocial personality traits in convicted adolescents compared to non-convicted (Castañeda et al., 2012) have been associated with CPV in cross-sectional studies. These personality characteristics in adolescents are closely related to psychopathic traits, which have been the focus of researchers in the field of youth criminal and aggressive behavior in the last few years, following the studies of psychopathic traits in adults (Buss, 1966; Hare, 2003). The conceptualization of psychopathic traits has evolved in the last decades, leading to a widespread 3-factor model: grandiose-manipulative (interpersonal dimension), callous-unemotional (affective dimension), and impulsive-irresponsible (behavioral dimension). This structure appears to be applicable in adults and adolescents (for a review see Salekin, 2017). It is the basis of the widely used questionnaire, the Youth Psychopathic Self-inventory (Andershed et al., 2002), to assess psychopathic traits. Previous empirical studies have linked psychopathic traits with aggressive behavior in children and adolescents. In particular, there is evidence of a predictive association of psychopathic traits with cyberbullying (López-Larrañaga & Orue, 2019) and antisocial behavior (Penney & Moretti, 2007). However, in the case of CPV, there is only one previous study whose findings suggest a predictive role of psychopathic traits in CPV (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2022). Other personality traits linked to aggressive behaviors in childhood and adolescence are borderline personality traits. Borderline personality traits are those features that refer to tendencies of schemas, emotions, and behaviors of instability, impulsivity, and fears of abandonment, among others. These traits might increase the risk of developing a borderline personality disorder in adulthood (Crick et al., 2005). At an empirical level, borderline personality traits have been associated with proactive physical aggression and relational aggression (e.g., manipulating others’ feelings) in previous longitudinal studies (e.g., Banny et al., 2014). However, no exploration of its relation to CPV has been carried out as of yet. The Role of Sex Results of previous studies regarding sex differences in CPV are still inconclusive. While most of the studies found a symmetry in perpetration (Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Pagani et al., 2009), some of them found higher rates of psychological aggression in girls (Margolin & Baucom, 2014; Calvete et al., 2015) and higher rates of physical aggressions in boys, especially in clinical or judicialized samples (Simmons et al., 2018). Sex may also be relevant when considering personality traits and their relationship with aggressive behaviors. Some studies have not found sex differences in psychopathic traits (Horan et al., 2015). However, a cross-sectional study in adolescents who had been separated from their parents early on found that boys showed higher psychopathic traits than unseparated boys, but this change did not show up in girls (Ang et al., 2014). Moreover, sex moderated the predictive association between psychopathic traits and aggressive behaviors in adolescents (Orue et al., 2016), where callous-unemotional traits were more relevant in girls, while grandiose-manipulative traits were more relevant in boys. Regarding borderline personality traits, even though it is a far less assessed topic in childhood and adolescence than in adults, the tendency appears to be the same: borderline personality traits are higher in girls than boys (Crick et al., 2005). Moreover, some sex-related specificities appear in the relationship between borderline traits and antisocial or aggressive behaviors. In particular, when presenting borderline personality traits, girls seem to be more involved in relational aggressions and boys in physical aggressions (Banny et al., 2014; Ostrov & Godleski, 2010), and those relations appear to be stronger in clinical samples (see Mancke et al., 2015, for a review). Nevertheless, a longitudinal study suggests that, in girls, borderline traits might not be relevant in the association between childhood aggression and relational aggression (Burnette & Reppuci, 2009). Thus, these results, while inconclusive, suggest that aggressions might answer to slightly different patterns by sex: girls might get involved in more relational and psychological aggressions, particularly when borderline and/or callous-unemotional traits are present, and boys in physical aggressions, particularly when grandiose-manipulative and/or borderline traits are present. The Present Study As follows from the literature review, there is a broad consensus on the relevance of family variables (e.g., psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and ignoring misbehavior) in CPV development. On the other hand, there is still little evidence about the role adolescents’ individual variables may play. Some personality traits, particularly psychopathic and borderline personality traits, have shown a predictive role in violent or aggressive behavior. However, almost no studies have explored its influence on CPV specifically. Given that personality is dynamic to some extent, mainly in adolescence (Crick et al., 2005), knowledge about the role of these personality traits in CPV development and maintenance, as well as their interaction with family variables, is crucial to improve our understanding of CPV etiology to enhance its detection, prevention, and intervention. This study, thus, examined the predictive role of adolescents’ personality variables (namely, psychopathic and borderline personality traits) and inadequate parental discipline (namely, psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and ignoring misbehavior), as well as their interactions in CPV development both when perpetrated toward fathers (CFV) or mothers (CMV). We hypothesized that all inadequate parental discipline strategies (Pagani et al., 2004, 2009) and adolescents’ personality traits – psychopathic and borderline – (Banny et al., 2014; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2022) will predict both CFV and CMV. Moreover, we expected to find significant interactions between inadequate parental discipline strategies and adolescents’ personality traits in CPV prediction. In particular, we expected that the predictive association between inadequate parental discipline strategies and CPV would be higher for those adolescents who report higher scores on psychopathic and borderline personality traits than those who report lower scores on these personality traits (Muñoz et al., 2011; Yendell et al., 2022). In addition, we also considered sex differences. Inadequate parental strategies and personality traits were expected to predict CFV and CMV in both girls and boys. Given the absence of previous research studying the moderating role of adolescents’ sex in this relationship, we analyzed this issue exploratorily. Participants The initial sample consisted of of 905 adolescents (49.5% girls, 49.1% boys, and 1.4% non-binary; Mage = 13.48, SD = 1.19; ranged from 12 to 17) from five high schools (from 7th to 11th grade) in Biscay (Basque Country, Spain) who answered questionnaires at Wave 1 (W1). Of these, 671 adolescents (74.14%) also answered the questionnaires at Wave 2 (W2) six months later, making up the final study sample (50.8% girls, 47.7% boys, and 1.5% non-binary; Mage = 13.39, SD = 1.15). Regarding nationality, 95.8% of the participants were Spanish, 4% were from other countries (mainly South America), and the remaining 0.2% did not report their nationality. Regarding socio-economic status, parents’ professions were classified as follows (according to the criteria of the National Institute of Statistics of Spain, 2012): scientific and intellectual professionals (23.72%), restaurant and security service workers and vendors (22.22%), artisans and skilled workers in the manufacturing and construction industries (18.42%), elementary occupations (8.01%), housekeepers (5.91%), accounting and administrative employees (5.91%), machinery operators (4.70%), unemployed (4.30%), technicians and support professionals (3.00%), directors and managers (3.00%), and skilled workers in the agricultural, livestock, forestry, and fishing sectors (0.80%). Attrition analyses were conducted to examine whether participants who completed both study waves were similar to those who dropped out at W2. Results showed no significant differences by sex, χ2(2) = 4.033, p = .133, although adolescents who failed to complete W2 were older, t(955) = 4.75, p < .001. Concerning the other study variables (i.e., inadequate parental discipline strategies and adolescents’ personality traits), we only found a significant difference between completers and non-completers in the callous-unemotional traits, being higher in those who dropped out at W2, t(855) = 2.15, p = .033. Measures Child-to-Parent Violence The Revised Child-to-Parent Aggressions Questionnaire (CPAQ-R; Calvete et al., 2022) was used to assess child-to-father and child-to-mother violence behaviors. The CPAQ-R includes two sections. The first section assessed CPV behaviors and the second explored adolescents’ reasons for perpetrating those behaviors. For this study, only the behavioral section was used. In particular, this section consists of two parallel forms regarding fathers (CFV) and mothers (CMV), of nine items each (e.g., “You’ve made fun of him/her”). Items are answered on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (six or more times). Participants were asked to answer on their behavior referring to the last three months. For this study sample, ordinal alphas were .88 for CFV and .89. for CMV at W1, and .90 for CFV and .91 for CMV at W2. Inadequate Parental Discipline Strategies The Dimensions of Discipline Inventory – Childreport (DDI-C; Straus & Fauchier, 2007; Spanish adaptation by Calvete et al., 2010) was employed to assess inadequate parental discipline strategies. The DDI-C evaluates nine disciplinary strategies of the parental figures. Considering the objectives of this study, the subscales of psychological aggression (four items; e.g., “How often did your parents shout or yell at you?”), corporal punishment (four items; e.g., “How often did your parents shake or grab you to get your attention”), and ignoring misbehavior (two items; e.g., “How often did your parents purposely not pay attention when you misbehaved?”) were used. Participants were asked to think of these behaviors when they were 10 years old. Items were answered on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (almost daily). Ordinal alphas for this study sample were .85 for psychological aggression, .86 for corporal punishment, and .58 for ignoring misbehavior. Psychopathic Traits The Yout h Psychopathic Inventory – Short Version (YPI-S; van Baarderwik et al., 2010; Spanish adaptation by Orue & Andersen, 2015) was used to assess psychopathic traits. It includes 18 items divided into three subscales (six items each): grandiose-manipulative (interpersonal dimension, e.g., “It’s easy for me to manipulate people”); callous-unemotional (affective dimension, e.g., “To be nervous and worried is a sign of weakness”), and impulsive-irresponsible (behavioral dimension, e.g., “I consider myself as a pretty impulsive person”). The items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 4 (applies very well). In this study, ordinal alphas coefficients were .87 for grandiose-manipulative, .80 for callous-unemotional, and .78 for impulsive-irresponsible. Borderline Personality Traits The Personality Belief Questionnaire – Short form (PBQ-SF; Butler et al., 2007; Spanish adaptation by Ferrer et al., 2018) was used to measure borderline personality traits. The PBQ-SF is a 63-item questionnaire that assesses the central dysfunctional beliefs related to each personality disorder. For this study, participants only answered the seven items of the borderline personality disorder subscale (e.g., “I can’t trust nobody”), rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (nothing at all) to 4 (absolutely). The ordinal alpha coefficient for this sample was .89. Procedure The Research Ethics Committee approved the project (masked for review). After approval, we invited 20 high schools from Bizkaia (Spain), randomly selected, to collaborate in the study. Of them, one urban and four metropolitan high schools agreed to participate (three were subsidized private schools and the other two public schools). We asked both parents and adolescents to provide their informed consent. Parents received information in a passive consent form sent by the school online, highlighting its voluntary, anonymous (answers from wave to wave were linked through codes), and confidential nature, along with the possibility of withdrawing their permission at any time. If parents would decline their children’s participation, they had to return the consent form to the center or the researchers themselves. Around 3% of the parents declined their children’s participation, while only two adolescents refused to participate. Adolescents were provided with information documents through the educational centers’ directions and again received explanations in person from the researchers on the day of the assessment. W1 assessment measures were collected between December 2020 and March 2021, and W2 assessment measures six months later. Participants completed measures on inadequate parental discipline strategies and psychopathic and borderline personality traits at W1 and CPV at W1 and W2. The questionnaires were answered online through Qualtrics®, in their classrooms with the researcher with them to clarify any of their questions. Data Analysis Descriptive statistics and Spearman’s rho correlation coefficients were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.28. Path analyses were conducted with LISREL 8.8 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006). Considering that data did not follow a normal distribution, we used the robust maximum likelihood (RML) method, which estimates the asymptotic covariance matrix of the sample variances and covariances, and includes the Satorra-Bentler scaled χ2(S-B χ2). The goodness of fit was examined using the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normed fit index (NNFI), and the root mean square of error approximation (RMSEA). Generally, CFI and NNFI values of .95 or higher and RMSEA values lower than .08 indicate a good fit for longitudinal data (Little, 2013). The hypothesized model included: (a) the auto-regressive paths between CFV and CMV at W1 and W2, respectively; (b) the predictive paths from psychopathic traits (grandiose-manipulative, callous-unemotional and impulsive-irresponsible), borderline personality traits, and inadequate parental discipline strategies (psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and ignoring misbehavior) to CFV and CMV at W2; and (c) predictive paths from the two-way interaction terms between personality traits and discipline strategies to CFV and CMV at W2. For the moderation analysis, the total scores of discipline strategies (psychological aggression, corporal punishment, and ignoring misbehavior) and personality traits (grandiose-manipulative, callous-unemotional, impulsive-irresponsible, and borderline) were transformed into z-scores. The signification of the plotted slopes was assessed by the method developed by Dawson (2018) with his Excel macros. We also explored whether the model was invariant across sex through a multiple-group analysis. First, the hypothesized model was tested separately for boys and girls, where new paths appeared in both models. Second, we tested the configural invariance of the pattern of fixed and free model parameters across sex subsamples with the paths that were represented in, at least, one of the models (general, boys or girls). Third, we tested the invariance of the paths of the configural model one by one. Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square comparisons were conducted following the method developed by Satorra & Bentler (2001). Descriptive Analyses Table 1 shows descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviations) for all study variables. As can be seen, sex differences were found for the parental discipline strategy of psychological aggression, the impulsive-irresponsible, and borderline personality traits, where girls report significantly higher scores. Furthermore, Table 2 gathers the correlations among study variables, which all positively and significantly correlated. Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Sex Differences for All Variables of the Study   Note. W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2; CMV = child-to-mother violence; CFV = child-to-father violence; PA = psychological aggression; CP = corporal punishment; IM = ignoring misbehavior; GM = grandiose-manipulative; CU = callous-unemotional; II = Impulsive-Irresponsible; BPT = borderline personality traits. 1 Non-binary were excluded for sex difference analyses because of the low number of adolescents who reported that category. Table 2 Spearman’s Rho Correlations Coefficients among the Study Variables   Note. W1 = wave 1; W2 = wave 2; CMV = child-to-mother violence; CFV = child-to-father violence; PA = psychological aggression; CP = corporal punishment; IM = ignoring misbehavior; GM = Grandiose-Manipulative; CU = Callous-Unemotional; II = Impulsive-Irresponsible; BPT = borderline personality traits. *** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. Predictive Path Analyses Figure 1 shows the significant model paths for the total sample. This parsimonious model obtained adequate fit indices: S-B χ2(173, n = 671) = 643.07, RMSEA = .063, 90% CI [.057, .068], CFI = .96, NNFI = .95. The model explained 33.3% of the variance of CFV at W2 and 42.1% of CMV at W2. All autoregressive paths were significant. Moreover, psychological aggression towards the child predicted an increase in CFV at W2, while ignoring misbehavior predicted an increase in CMV at W2. The interaction between ignoring misbehavior and callous-unemotional also significantly and positively predicted CFV and CMV at W2. In contrast, the interaction between psychological aggression and borderline personality traits significantly and negatively predicted CFV at W2. Figure 1 Model of Inadequate Discipline Strategies, Personality Traits and Their Interactions Predicting CFV and CMV.   Note. Significant paths are depicted by continuous lines; non-significant paths are not depicted, except for needed paths (depicted in dashed lines); significant sex differences are not depicted, but commented in the text. CFV = child-to-father violence; CMV = child-to-mother violence; PA = psychological aggression by parents; CP = corporal punishment by parents; IM = ignoring misbehavior by parents; GM = Grandiose-Manipulative; CU = Callous-Unemotional; II = Impulsive-Irresponsible; BPT = borderline personality traits. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. As displayed in Figure 2a, ignoring misbehavior predicted a significant increase in W2 CFV in those adolescents who score high in the callous-unemotional trait (β = .217, t = 4.26, p < .000). However, for those adolescents who score low in the callous-unemotional trait, the relation between ignoring misbehavior and W2 CFV was not significant (β = -.095, t =-1.79 p = .073). We found similar results for the interaction between ignoring misbehavior and the callous-unemotional trait in predicting W2 CMV, that is, a significant increase is predicted for those who score high in callous-unemotional (β = .271, t = 6.29, p < .001; see Figure 2b), with no significant changes for those who scored low (β = -.023, t = -0.52, p = .601). When it comes to the interaction of psychological aggression and borderline personality traits, the pattern turned out to be the opposite (see Figure 2c). Parental strategies of psychological aggression predicted a significant increase in W2 CFV in those adolescents who scored low in the borderline personality trait (β = .163, t = 2.95, p = .003). However, the predictive association between psychological aggression and W2 CFV was not significant for those adolescents who scored high in this trait (β = -.003, t = -0.07, p = .944). Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c Interactions of Ignoring Misbehavior and Callous Unemotional towards CFV (2a) and CMV (2b), and Psychological Aggression and Borderline Personality Traits towards CFV (2c).   Note. Low/High Ignor Misb = low/high ignoring misbehavior; Low/High Psy Aggress = low/high psychological aggression; Low/High Call Unemot = low/high callous-unemotional ; Low/high Border Traits = low/high borderline personality traits. Sex Differences in the Model First, the model was tested separately for boys, S-B χ2(147, n = 320) = 258.49, RMSEA = .049, 90% CI [.039, .059], CFI = .98, NNFI = .96; and girls, S-B χ2(155, n = 341) = 399.58, RMSEA = .068, 90% CI [.059, .076], CFI = .97, NNFI = .95. The model for boys explained 39.2% and 41.2% of the variance of CFV and CMV at W2, respectively. The model for girls explained 38.3% and 39.2% of the variance of CFV and CMV at W2, respectively. Second, we tested the configural invariance of the model to demonstrate that the pattern of fixed and free parameters was equivalent across sex subsamples. To this end, a more parsimonious model was estimated, which included the significant paths in the full model, plus in boys and girls separately; S-B χ2(284, n = 661) = 658.77, RMSEA = .063, 90% CI [.057, .069], CFI = .97, NNFI = .95. Third, we tested the invariance of the model’s longitudinal paths. This constriction did not increase S-B χ2 significantly, χS-B χ2(26, n = 661) = 31.05, p = .226. However, considering the differences in the models for boys and girls, one-by-one path comparisons were conducted. These analyses showed that two predictive paths were significantly different for boys and girls (see Figure 1). The interaction between ignoring misbehavior and callous-unemotional predicting CMV was positive and significant only in girls. The interaction between corporal punishment and borderline personality traits predicting CMV was positive and significant only in boys. Figures 3a and 3b depict the interaction of ignoring misbehavior and callous-unemotional predicting W2 CMV. For girls (Figure 3a), ignoring misbehavior predicts an increase on CMV in those with high callous-unemotional traits (β = .454, t = 6.92, p < .001), but not for girls who are low in callous-unemotional (β = -.088, t = -1.45, p = .149). Nevertheless, for boys (Figure 3b), ignoring misbehavior tends to be associated with increases in CMV regardless the scores in callous-unemotional, although none of the slopes are significant (β = .120, t = 1.95, p = .052, for boys who are high in callous-unemotional; β = .116, t = 1.61, p = .108, for boys who are low in callous-unemotional). Figures 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d Significant Interaction in Girls (3a) but not in Boys (3b) and not Significant Interaction in Girls (3c) but Significant in Boys (3d).   Low/High Ignor Misb = low/high ignoring misbehavior; Low/High Corp Punish = low/high corporal punishment; Low/High Call Unemot = low/high callous-unemotional; Low/High Border Traits = low/high borderline personality traits. Finally, Figures 3c and 3d show the interaction between corporal punishment and borderline personality traits in predicting W2 CMV. As shown in Figure 3c, girls who are high in borderline personality traits reported higher mean scores on CMV than girls who are low in borderline personality traits, regardless of of the level of corporal punishment. However, corporal punishment did not predict an increase on W2 CMV for either girls low (β = .004, t = 0.057, p = .954) or high (β = .000, t = 0.000, p = 1.000) in borderline traits. For boys (Figure 3d), corporal punishment predicted an increase in W2 CMV for those with high borderline traits, although this predictive association was not significant (β = .064, t = 0.788, p = .431). For boys who were low in borderline traits, corporal punishment predicted a decrease on W2 CMV (β = -.192, t = -2.323, p = .021). This study examined the predictive role played by inadequate parental discipline strategies and personality traits (i.e., psychopathic and borderline personality traits) in adolescents’ CFV and CMV behaviors. We also examined the potential moderating role of personality traits in the predictive association between parental discipline strategies and CFV/CMV. Adolescents’ sex differences were considered in the analyses. The bivariate analyses showed positive cross-sectional and predictive associations between inadequate discipline strategies, psychopathic and borderline personality traits, and CFV and CMV. However, the longitudinal path analysis results showed that the most relevant variables in predicting CPV were psychological aggressions toward the child (which predicted CFV) and ignoring misbehavior (which predicted CMV). These results are partially consistent with previous studies evidencing how the lack of parental supervision predicts CMV but not CFV, whereas psychological aggressions toward children predict both types of CPV (Pagani et al., 2004, 2009). The previous studies estimated separate models for fathers and mothers. Our study introduced CMV and CFV in the same model, which could cause differences, such as psychological aggressions not predicting CMV. The fact that corporal punishment did not predict CPV requires more discussion. A recent study showed that corporal punishment predicted psychological CPV (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2018). However, when considering parents’ sex, Pagani et al. (2004, 2009) found that only CMV was associated with previous corporal punishment, and others found this relation only with maternal punishment (Margolin & Baucom, 2014). Additionaly, corporal punishment can cause other types of consequences (e.g., internalizing symptoms) and back out adolescents from answering aggressively, particularly younger ones (Gershoff, 2002; Simmons et al., 2018). Another line of research states that the context in which punitive discipline (corporal punishment and psychological aggression) happens has greater relevance than the strategy itself in CPV development (Cano-Lozano et al., 2022), or even other outcomes (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2010). Further investigation is needed on the role of corporal punishment in CPV, and as part of unhealthy outcomes, due to incongruences found in previous literature (Simmons et al., 2018). Regarding the relationship between adolescents’ personality traits and CPV, the lack of a significant direct predictive association in the longitudinal model between psychopathic traits and CPV differs from the only previous study examining these variables (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2022), as well as from other studies exploring similar characteristics as impulsiveness (Rico et al., 2017) and grandiosity (Orue et al., 2021). A possible explanation might come from the triple-interaction theory of psychopathic traits, which states that these characteristics might not be as powerful in predicting aggressive behaviors by themselves as their interaction (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2022; Somma et al., 2018). Within the three-factor distinction of psychopathic traits, this theory states that none of the features (cognitive, emotional, or behavioral factors) are related to aggressive or violent behavior but only if the three appear together. For example, an adolescent who acts recklessly (impulsive-irresponsible) can be hazardous but not harmful to others. Instead, these results might partially agree with a recent study that analyzed the role of different psychopathic (callousness, uncaring, and unemotional traits) and narcissistic traits, suggesting that they may be related only to some behavioral specificities of CPV (Cortina & Martín, 2020). Specifically, they found that callousness relates only to obscene gesturing and uncaring to spitting, in line with our results, while unemotionality and narcissism did not relate to CPV at all. In this same vein, our findings might answer to changes to the new version of the CPV assessment tool (CPAQ-R; Calvete et al., 2022), which does not differentiate between psychological and physical CPV behaviors (as the first version did), and is now more restrictive regarding violent behaviors, making the tool more sensitive to offenders (for a review, see Calvete et al., 2022). Particularly, the items of the previous CPAQ referring to common dissocial behaviors in adolescence were erased (e.g., “You ignored him/her”) and more violent behaviors added (e.g., “You made him/her feel frightened in an argument”), which might help explain the lack of predictive associations from impulsive-irresponsible or callous-unemotional traits to CPV (even in the general population). Similarly, contrary to previous studies on early adolescents’ general aggressive behaviors that have found a direct prediction from borderline personality traits (Banny et al., 2014; Crick et al., 2005), our findings did not show a direct predictive relationship between borderline personality traits and CPV. A possible explanation for these differences may be related to how borderline personality is measured. While cited studies have measured borderline personality mainly as emotional dysregulation traits, the measure we used relies mainly on dependency traits (the highest correlation of the borderline personality scale in the PBQ is with dependent personality: r = .84; Ferrer et al., 2018). In this regard, previous studies have shown that emotional dysregulation is highly associated with aggressive behavior (Banny et al., 2014), but dependency is not (Schweizer et al., 2020). Nevertheless, borderline personality – as well as psychopathic traits – were significant to understand CPV when considering its interaction with inadequate parental discipline strategies. The interaction between ignoring misbehavior and the callous-unemotional trait predicted both CFV and CMV, meaning the predictive association between ignoring misbehavior and CMV gets stronger with high callous-unemotional scores. Additionally, the prediction from ignoring misbehavior towards CFV is only significant if callous-unemotional traits are high. In this sense, deliberately not paying attention to children (i.e., ignoring them) and fathers’ tendency to be more absent (Kokoulina-Cherevach & Fernández-Martínez, 2016) may make adolescents move away. Nonetheless, the appearance of callous-unemotional traits, through unemotionality and remorselessness, may elicit CFV. Regarding the interaction between parental psychological aggression and borderline personality traits in predicting CFV, our findings suggest that adolescents with high parental psychological aggression and low borderline personality traits score higher in CFV. Thus, low levels of dependency and interpersonal sensitivity might reinforce the relationship between previous psychological aggression by parents and CFV. Future studies could focus on dependency to assess whether high dependent traits could lead to a retreat of CFV through other paths (e.g., short-term compliance and the development of internalizing symptomatology; Boxer et al., 2008; Gershoff, 2002). Finally, some significant sex differences emerged in the predictive model. The interaction between ignoring misbehavior and callous-unemotional traits in predicting CMV was only significant in girls. This difference could be because boys tend to be more sensitive to mothers’ ignoring behaviors (Godbout et al., 2019) and, therefore, callous-unemotional traits do not add explanative power. Moreover, the interaction of corporal punishment and borderline traits is only significant in boys. Specifically, results show that scores in CMV decrease when boys are victims of high levels of corporal punishment and have low borderline traits, with no significant differences for boys with high borderline traits. This could mean that borderline personality traits, at least as measured in this study, are not a relevant moderator in the predictive association between corporal punishment and CMV. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions To our knowledge, this is the first study examining the moderating role of personality traits in the predictive relation of inadequate parenting strategies and CPV behaviors. Moreover, using a more restrictive CPV assessment tool makes this research more representative. Still, we should address some limitations. First, participants were asked about childhood to measure parental discipline strategies, which may induce retrospective memory biases. Second, the ordinal alpha of ignoring misbehavior of the DDI-C (Calvete et al., 2010) for this sample was lower than that obtained in previous studies, suggesting caution about our conclusions for this discipline strategy. Third, participants’ mean age (13.48 years old) was lower than the age at which CPV behaviors peak (around 15 years old; Calvete et al., 2020), which is interesting because it focuses on the first stages of child-parent problems. However, some consequences of the suffered violence and CPV behaviors may change over time. Future directions might be considered based on this manuscript. For example, a three-wave mediational approach would also be of interest, given the previous literature describing the predictive role of parenting styles and child maltreatment in developing psychopathic and borderline personality traits. Finally, as our findings refer to adolescents’ general populations, they could differ from clinical or judicialized samples. Thus, future research should replicate these findings with adolescent clinical or CPV judicialized samples. Conclusions and Practical Implications The theoretical and empirical literature on adolescent aggressive behavior reveals the interaction between family and individual factors. Based on our findings, this conceptualization also applies to CPV. In particular, the results of our study support that the parental discipline strategy of psychological aggression is particularly relevant in predicting CFV and ignoring misbehavior in predicting CMV. In addition, emotional coldness (or callousness) in the presence of the previous parental discipline strategies, specifically ignoring misbehavior, has a relevant role in predicting aggressive behaviors toward fathers and mothers. These findings support the idea that emotional callousness might be the core of psychopathic traits and that these might play a relevant role in CPV development in adolescents (Hare, 2003). Also, sex-related differences in the model suggest that the callous-unemotional traits might be more relevant in girls when interacting with ignoring misbehavior from parents. Finally, regarding the sex of parents, parental psychological aggression was more relevant in CPV toward fathers, while ignoring misbehavior was more relevant in CPV towards mothers. Our findings highlight the need for CPV preventive and intervention programs or actions to consider parental discipline strategies used in rearing (especially on the consequences of psychological aggressions) and adolescents’ individual or personality traits. In particular, when speaking of adolescents, it could be helpful for interventions to work on adolescents’ affectivity to be more conscious of their own flaws when practicing empathetic behaviors or to learn to handle emotional dysregulation. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Funding: This study was supported by the Research Training Grants Program for Pre-doctoral contracts from Deusto University, Bilbao, Spain (FPI Scholarships). Cite this article as: Jiménez-Granado, A., del Hoyo-Bilbao, J., & Fernández-González, L. (2023). Interaction of parental discipline strategies and adolescents’ personality traits in the prediction of child-to-parent violence. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 15(1), 43-52. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2023a5 References |

Cite this article as: Jiménez-Granado, A., Hoyo-Bilbao, J. D., & Fernández-González, L. (2023). Interaction of Parental Discipline Strategies and AdolescentsŌĆÖ Personality Traits in the Prediction of Child-to-Parent Violence. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 15(1), 43 - 52. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2023a5

Correspondence: aitor.jimenez@deusto.es (A. Jim├®nez-Granado).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS