Development of an Index to Evaluate Children’s Risk for Being Instrumentalized in Intimate Partner Violence against Women Contexts

[El desarrollo de un Ăndice para evaluar el riesgo de instrumentalizaciĂłn de los menores en contextos de violencia contra la mujer por parte de la pareja]

José C. Ríos Lechuga1, Juan M. Alarcón Cuenca2, and Esther Lopez-Zafra3

1Social Services Inspection Service, Junta de AndalucĂa, JaĂ©n, Spain; 2Violence against Women Unit, Government Sub-delegation in JaĂ©n, Government of Spain; 3Universidad de JaĂ©n, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a7

Received 17 November 2023, Accepted 13 May 2024

Abstract

Background/Objective: The risk of children being instrumentalized in contexts of gender violence poses a social and health problem that impacts children’s future development. The main purpose of this research is to ascertain which risk indicators should be addressed by security force members when facing an emergency call regarding intimate partner violence in which children are present. This tool could be helpful for evaluating and preventing the risk of future aggression as a means to hurt mothers. Method and Results: In the course of three studies, a set of proposed risk indicators was developed. In Study 1, five interviews and two group discussions with experts working in gender violence cases (n = 18) provided us with information to develop an initial version of a measurement tool, the Index of Children’s Risk of being Instrumentalized (ICRI), for gender violence cases. In Study 2, cognitive debriefing was carried out by professionals (n = 26) to evaluate the suitability of the items. This approach allowed us to obtain valid, content-based evidence. Finally, Study 3 included a pretest study in which security force members (n = 44) evaluate the appropriateness of the ICRI and, if needed, to make any necessary adjustments of the index. The results show that the indicators obtained in this initial approximation could help security forces when reporting cases of gender violence with children at the scene. Conclusions: Further attention to evaluating the risk of children living in intimate partner violence contexts is needed.

Resumen

Antecedentes/Objetivo: El riesgo de instrumentalización de los niños y niñas en contextos de violencia de género plantea un problema social y de salud que afecta a su desarrollo futuro. El objetivo principal de esta investigación fue determinar qué indicadores de riesgo deben abordar los miembros de las fuerzas de seguridad cuando se enfrentan a una llamada de emergencia relacionada con la violencia de pareja en la que hay menores presentes. Esta herramienta podría ser útil para evaluar y prevenir el riesgo de futuras agresiones como medio para hacer daño a las madres. Método y Resultados: A lo largo de tres estudios se desarrolló una propuesta sobre un conjunto de indicadores de riesgo. En el estudio 1 cinco entrevistas y dos discusiones de grupo con expertos que trabajan en casos de violencia de género (n = 18) nos proporcionaron información para desarrollar una versión inicial de una herramienta de medición, el Índice de Riesgo de Instrumentalización Infantil (ICRI), para casos de violencia de género. En el estudio 2 se realizó un debriefing cognitivo por parte de profesionales (n = 26) para evaluar la idoneidad de los ítems. Este enfoque permitió obtener pruebas válidas y basadas en el contenido (validez de contenido). Por último, el estudio 3 incluyó un estudio en el que los miembros de las fuerzas de seguridad (n = 44) evaluaron la idoneidad de la ICRI y, en caso necesario, se realizaron los ajustes pertinentes. Los resultados mostraron que los indicadores obtenidos en esta aproximación inicial podrían ayudar a los miembros de las fuerzas de seguridad a denunciar casos de violencia de género con niños en el lugar de los hechos. Conclusiones: Es necesario prestar más atención a la evaluación del riesgo que tienen los niños o niñas que viven expuestos a violencia en contextos de violencia en la pareja.

Keywords

Children, Evaluation, Intimate partner violence against women, Risk indicatorsPalabras clave

Menores, Evaluación, Violencia de pareja contra la mujer, Indicadores de riesgoCite this article as: Lechuga, J. C. R., Cuenca, J. M. A., & Lopez-Zafra, E. (2024). Development of an Index to Evaluate Children’s Risk for Being Instrumentalized in Intimate Partner Violence against Women Contexts. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 16(2), 77 - 86. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a7

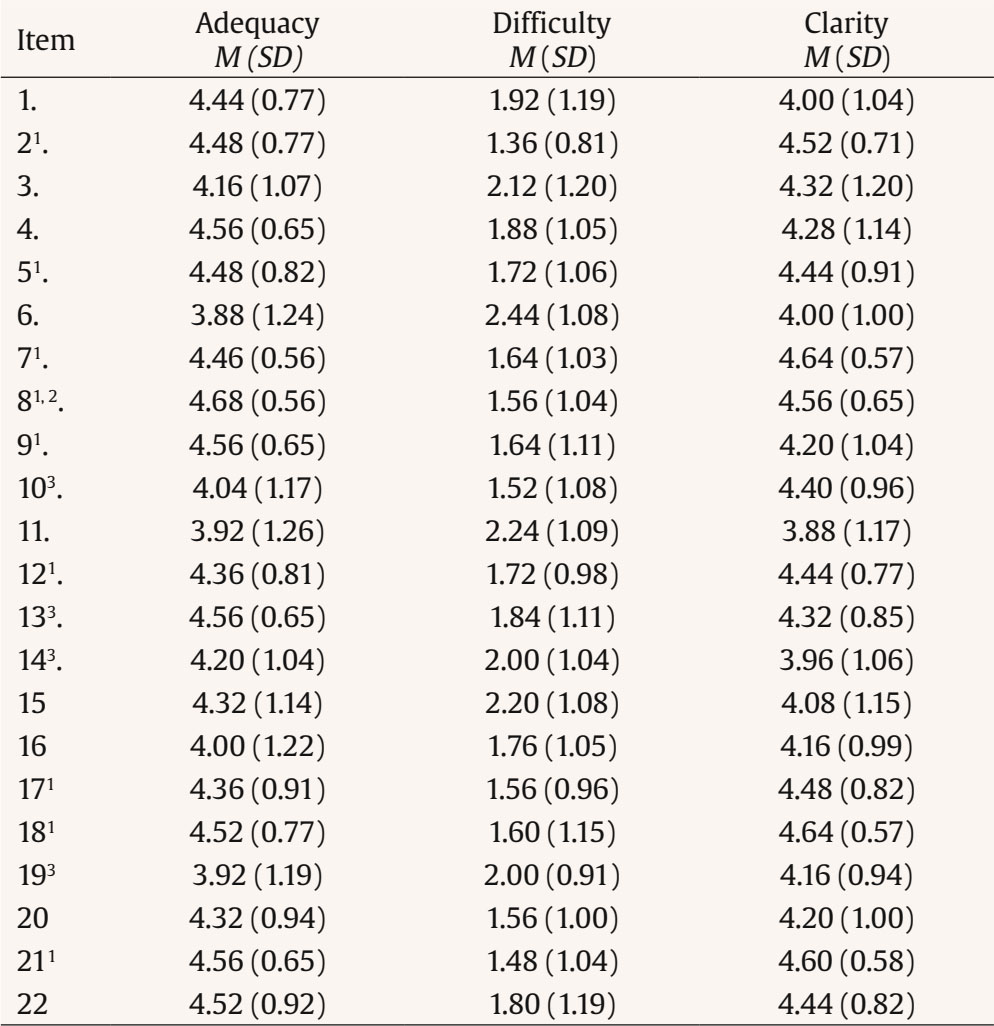

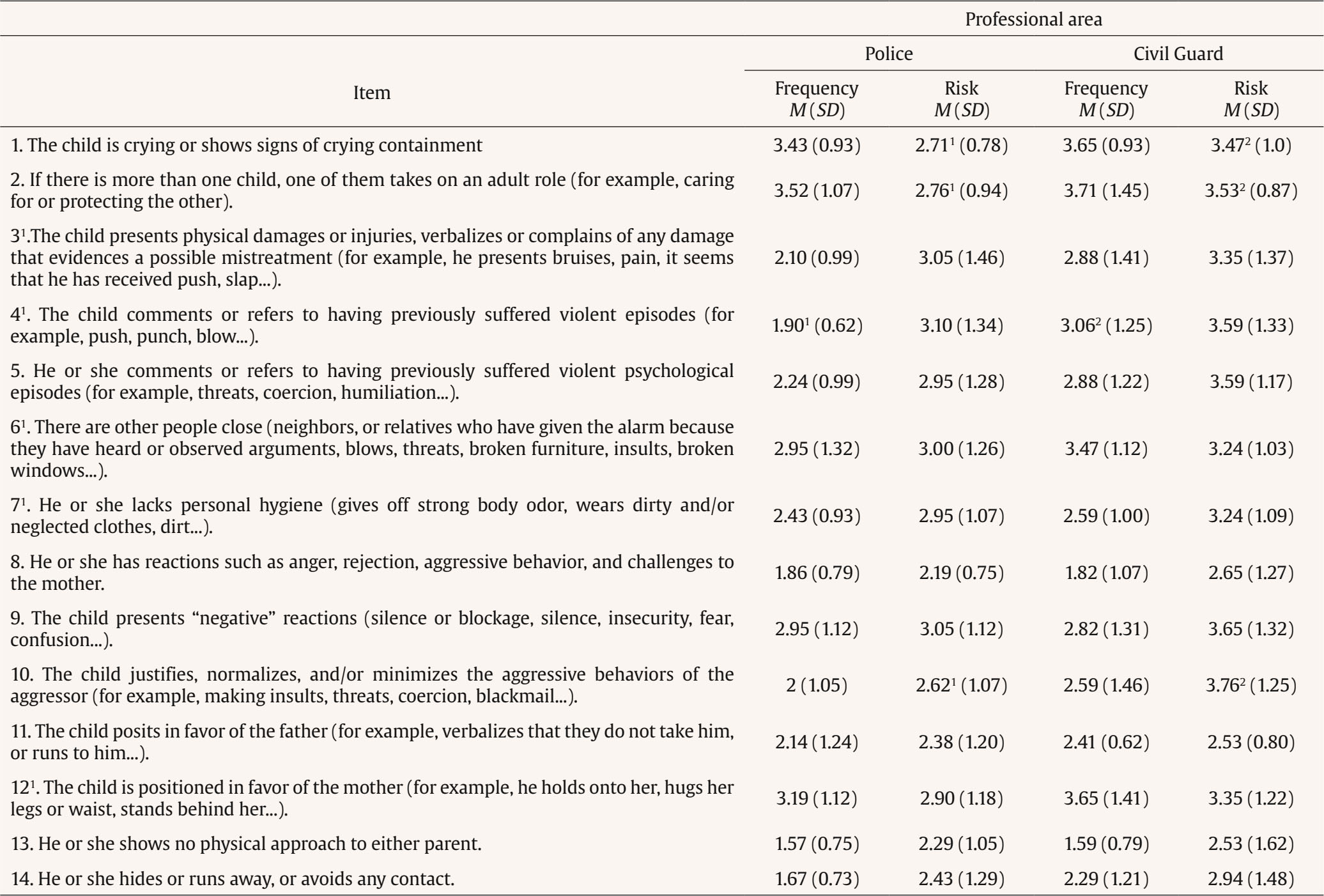

Correspondence: elopez@ujaen.es (Esther Lopez-Zafra).Violence against women occurs primarily in family or partner relationships. In many cases, children living in this context suffer direct damage. Although intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) is recognized as a social (Ferrer-Pérez & Bosch-Fiol, 2014) and priority health issue and major public health problem (World Health Organization, 1997, 2012), the degree of risk of these children is underestimated (Carnevale et al., 2020; Scott et al., 2020). A forensic psychological assessment, risk management, and child-adolescent safety planning in the context of IPVAW should be considered of utmost importance for its correct prevention (Olszowy et al., 2017). Therefore, acknowledging possible risk indicators should be a priority for developing better first interventions with these victims. There is a great debate about the effectiveness of forensic evaluation based on a psychometric measure with that based on the content analysis of the interview of psychological damage in cases of gender violence (Arce et al., 2015). The results show that the forensic evaluation requires the adoption of a multi-method strategy combining psychometric evaluation and interview to nullify the possibility of false positives. In this context, the most appropriate method of evaluation is structured professional judgment (SPJ; López-Ossorio et al., 2020), which combines multi-method: clinical and actuarial procedure (Loinaz, 2017). In both approaches, it is important to consider indicators that allow professionals to make accurate evaluations. Kropp and Hart (2000) defined SPJ as “a decision made without fixed and explicit rules but based at least in part on consideration of a standardized information base” (p. 102). This standardized information can be based on scales and questionnaires offering an evidence-informed approach to ascertain the degree of threat for the victim. In Spain, several instruments have been used to evaluate the risk of a partner being abused to different degrees (i.e., Severe Intimate Violence Partner Risk Prediction Scale, SIVIPAS; Echeburúa, et al., 2009; Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, CTS2; Straus et al., 1996, 1998). These instruments focus on women victims and not on children exposed to this violence at home. Therefore, it is important to develop direct indicators for children. Moreover, individuals using these SPJ tools to assess violence should have formal training in psychological areas (Nichols et al., 2013). However, criminal justice professionals (mostly police) can also be trained to conduct IPVAW risk assessments. For example, in Spain, the current Protocol on Police Assessment of the Risk of Gender Violence (in the terms of LO 1/2004), pertaining to the management of the safety of victims and follow-up of cases through the VioGén System, has implemented a new methodology for dual risk assessment. The VPR5.0-H (Police Risk Assessment, version 5.0-H) and VPER4.1 (Police Risk Evolution Assessment, version 4.1) instruments are structured and articulated from factors linked to violence that are jointly integrated, interpreted, and scored with expert knowledge to reach a final decision on the prognosis of future behavior (López-Ossorio et al., 2020). However, information about children exposed to this context is lacking. Specifically, our examination of the current indicators included in the Protocol on Police Assessment of the Risk of Gender Violence (in the terms of LO 1/2004), pertaining to managing the safety of victims and monitoring cases through the VioGén System (López-Ossorio et al., 2020, 2021), revealed that only three out of the 35 items that make up the form VPR5.0-H (Police Risk Assessment, version 5.0-H) relate to children. The three indicators are included under the subheading Circumstances related to children: the victim is responsible for children; threats exist to the physical integrity of the children; the victim fears for the physical integrity of the children. The Civil Guard also asks about the presence of children when a complaint is lodged. Specifically, they ask whether the children have suffered any maltreatment, whether the victim feels s/he is at risk, and whether the mother is afraid of them being abducted or fears for their safety. Thus, the information is subjective and comes only from the woman victim. We aimed to determine whether other indicators, such as those derived from observations of security force workers, could be more accurate. The Council of Europe (2011) recognizes that children are victims of gender violence as witnesses of violence in the family. Furthermore, “Effective co-operation [is needed] between all relevant state agencies, including the judiciary, public prosecutors, law enforcement agencies, local and regional authorities, as well as nongovernmental organizations and other relevant organizations and entities, in protecting and supporting victims and witnesses of all forms of violence” (p. 31). This recommendation is being considered by national laws. For instance, in Spain, the law on intimate partner violence against women (Ley Orgánica 1/2004, de 28 de diciembre, de Medidas de Protección Integral contra la Violencia de Género [L.O. 1/2004], 2004) included damage to children as part of gender violence. Furthermore, the Spanish rule for the protection of children against violence (Ley Orgánica 8/2021, de 4 de junio, de Protección Integral a la Infancia y la Adolescencia Frente a la Violencia [L.O. 8/2021], 2021) recognizes children as victims of vicarious violence, defined as “violence with the aim of causing harm or harm to women inflicted on their relatives or close relatives who are minors” (p. 15) and provides a series of legal actions to address this phenomenon. Thus, it is fully assumed in the legal sphere as a type of child abuse within the IPVAW in Spain. Indeed, evidence of the damage to children living in a context of gender violence is very strong and has been showed in the scientific literature. Beeble et al. (2007) demonstrated that fathers can harm their children to control their partners. This harm affects children’s health in multiple ways. Reviews on how the health of children is impacted from pregnancy to the first breath of life have shown that this impact occurs beginning with the fetus (Do et al., 2019) and continues with health and psychosocial problems in childhood (Cage et al., 2022; Dababnah et al., 2018; Holmes et al., 2022; Ravi & Black, 2022). Furthermore, these children can have relationship problems in adulthood based on their experiences of IPVAW (Evans, Lee et al., 2022; Evans, Schmidt-Sane et al., 2022; van Rosmalen-Nooijens et al., 2017). Reviews about behavioral impairment include internalizing and externalizing problems, issues with sociocognitive competence or a cognitive context with poor cognitive functioning, impaired verbal and academic skills (Bender et al., 2022; Savopoulos et al., 2023; Vu et al., 2016), inadequate coping strategies (Hines, 2015), normalization of peer violence (e.g., bullying; Lee et al., 2022), or violence against pets (Hartman et al., 2016; McDonald et al., 2017; McDonald et al., 2015). Other reviews have focused on the risk and protective factors (e.g., social and emotional support, resilience) of being exposed to gender violence (Benavides, 2014; Fong et al., 2019; van Eldik et al., 2020). Among those experiencing emotional damage, children and emerging adults instrumentalized in IPVAW contexts suffer from anxiety, anger or depression (Ravi & Casolaro, 2017), and are more aggressive than other young people (Rosser-Limiñana et al., 2020). Moreover, these children can also be abused or polyvictimized (Gregory et al., 2020) as a way to control their mothers. Other reviews have focused on sociodemographic variables (e.g., sex and age; Tailor & Letourneau, 2012), children experiencing other additional adversities (e.g., drugs, abuse, or economic problems; Ravi & Casolaro, 2017), or individual, family, and community factors that affect this gender violence by instrumentalizing children (Carter et al., 2022; Van Wesel et al., 2012). Only one review focused on direct consequences for instrumentalized children, such as being directly exposed to violence, being physically injured or being killed (Jaffe et al., 2012). The most recent systematic review of meta-analyses on this issue (Holmes, 2022) explores different domains in children who have been impacted by this instrumental violence. Among these, young people who had been exposed to IPVAW had much lower levels of socioemotional abilities and greater levels of emotional deregulation than those who had not been exposed. Furthermore, they were more prone to accepting parental violence as normative or justifiable, which in turn predicted their perpetration and/or victimization of intimate partner violence. Finally, adjustment at the academic level decreased with exposure to gender violence, as indicated by increased episodes of expulsion, truancy, disciplinary violations, and suspensions. This effect is aggravated if the child is doubly exposed to IPVAW and child abuse. Although systematic reviews and meta-analyses have focused on specific aspects of this exposure to gender violence at home (Holmes et al., 2022), studies assessing the risk factors linked to exposure to intimate partner violence are scarce. This lack of research hampers the design of evidence-based prevention programs. Therefore, our study aimed to identify the indicators that could help first aid attenders (police, civil guard, sociocommunity workers, etc.) evaluate the risk of children in the context of IPVAW of being abused or damaged in an instrumentalized way by their father or the couple or to hurt their mothers. To address this aim, we performed three studies in a sequential process, moving from the general to the particular, with the goal of obtaining specific items that can be easily and rapidly evaluated. Following the SPJ and international standards (i.e., Douglas et al., 2014; European Institute for Gender Equality, 2020), the main steps were a thorough review of the concept to propose a pool of items (Rios et al., 2023), the testing of item suitability by experts, and empirical testing. The initial approach asserted that professionals involved in IPVAW processes know about the consequences for children exposed to this violence, but there is a lack of instruments that help them, in urgent situations, to capture information on all the damage that children may suffer. Study 1. Qualitative Study The main aim of this first study was to assess experts’ perceptions of the risk situations experienced by children living in a context of gender violence. In addition to the analysis of the current indicators considered in official records, a systematic review of the literature (Ríos et al., 2023) was performed by the research team, along with two postgraduate students trained in IPVAW, to address the elements related to the consequences for children in a gender violence context and to include these elements in a script of questions to be asked to professionals in the area. This review aimed to be comprehensive and state of the art and to review any possible instrument or approach to the risk of children being instrumentalized in contexts of gender violence. The main conclusions of this review were as follows. First, social desirability for both the aggressor and the victim is present when parents report their children’s risk (Guerrero-Molina et al., 2016; Henning & Holdford, 2006). Second, fathers attempt to present the best image of their parental competences by overestimating their qualities but usually refer to a punitive parenting style (Hernández-Palacios, 2017). Third, mothers fail to protect their children because they minimize and normalize the situation at home. Fourth, the children who suffer most from this type of violence are the youngest, are more dependent on their mother, present more internalizing-externalizing symptoms, and experience more problems with creating a secure attachment bond when situations of gender violence occur at home (Silva et al., 2021). Fifth, children in these contexts can intervene in, be victimized, participate, be eyewitnesses of or listen to incidents, observe the initial effects, and experience the aftermath of gender violence; they are thus active agents whom we must consider in assessments. Moreover, children’s difficulty in asking for support is strongly associated with their ability to reveal and communicate their needs, an aspect to which professionals must be sensitive to obtain their collaboration in the evaluation process. Forensic psychological reports are key in these cases for establishing causal links (Adhia et al., 2019). Finally, the research by Muñoz et al. (2022) confirms that assessment records rarely mention aspects of these children such as their personal characteristics, their link to the aggressor, their previous life circumstances, their schooling, or the type of life they have lived. Accordingly, no evaluation reports refer to children’s emotional state prior to being victimized, even though the case makes this a central element of the prosecution. This review highlights the importance of not simply relying on parental reports, but also directly receiving children’s reports about their own experience with exposure to IPVAW. Therefore, in our research, we included children as direct victims, but decided not to include them as informants due to the current stage of this study. Following a critical incident technique, (CIT; Flanagan, 1954; see also Butterfield et al., 2005), the interviewer asked the participants to think of incidents that could help to determine the level of risk (high or low) of children experiencing violence in this context as a way of harming their mother. The recall of critical incidents involves professionals’ implicit knowledge that is available through these memories. Method Participants and Procedure This study had two phases. First, five specialists dealing with children in gender violence contexts were interviewed individually. These specialists represented the legal and forensic fields, including psychologists, coroners, prosecutors, and judges in family and gender violence courts. Theoretical intentional sampling was used. Narrative-focused interviews were carried out, transcribed verbatim and analyzed through grounded theory methodology. In the second phase, two discussion groups were formed. One consisting of six members from the state forces (national policemen, n = 2, local policemen, n = 2, and civil guards from the women-children team, n = 2). The second group comprised seven workers from the social and community spheres, including psychologists from the Institute for Women (n = 2), social workers from Social Services (n = 2), the Education Delegation (n = 1), and from the victims’ attention group and reception center (n = 2). Finally, the sample for the qualitative study was composed of eighteen experts (women = 14, men = 4)1. To organize the sessions, professionals in the field were first contacted via mail and telephone. They were informed about the research aim and the need for their participation. The participants provided informed consent after the session schedules were established but prior to the session. They also consented to be recorded for subsequent transcription. All the processes followed ethical procedures, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Jaén, Spain (Ref. CEIH 160215-1). In the session, the main researcher asked the experts about their work with victims of gender violence and these victims’ children and about the critical aspects that they observed in their job when children were involved. The script was semi-structured to allow participants to make further contributions. The interviews and the group discussions lasted approximately two hours each (for a total of 15.5 recorded hours). Transcriptions were carried out by two postgraduate students trained in IPVAW. Two experts in IPVAW performed content analysis of the transcriptions. First, they read through the information separately, noted a number of ideas, and created a number of general categories, including the main ideas extracted. Then, a third researcher considered both proposals and read the transcriptions on his own, but no new themes were extracted. Finally, five researchers discussed in a workshop the emerging themes and patterns related to the meaning, main ideas, frequency, and relationships among various categories. The final items in this phase were formulated via brainstorming with reference to the main categories and themes described by the three experts. Finally, one of the students generated a list of these items, which the research group read and refined in another session. Instrument A semi-structured interview was performed by including twelve questions related to the children exposure to IPVAW. These items were derived from the literature revision and the professional experience of the three researches performing this study. Summarizing, the questions included 1) conceptualization of the vicarious violence; 2) training of professionals about this type of violence; 3) which professionals they consider that have to evaluate risk in these situations; 4) specific behaviors they usually observe in fathers or intimate partner against mothers and children; 5) direct or indirect consequences of these behaviors they observe in children, considering behaviors, emotions and cognitions; 6) when working with children exposed to these situations, which are the changes in behaviors, emotions and cognitions they observe; 7) verbalizations and emotional expressions in children instrumentalized in IPVAW contexts; 8) reactions of women victims about their children; 9) reactions of aggressors when they intervene as professionals (collaborate or not, negation of the episode, etc.); 10) differences between other maltreatment types and this one; 11) how to detect whether this is a case of instrumentalization of children in IPVAW; 12) which are the main incidents to consider a high risk for these children. Results The interviewees were asked about their conceptualization of vicarious violence, which is the term that Spanish law proposes for this phenomenon (L.O. 8/2021). However, the interviewees agreed that this was not a good term for referring to this problem. In the international literature, also highlighted by Ríos et al. (2023), vicarious violence is used to refer to any violence exerted by a violent male aggressor toward any other person (e.g., mother, neighbor, aunt), pet or even a child, to control a woman victim. The interviewees proposed “extended violence” or “children’s instrumentalization” to indicate that the aggressor is damaging them to hurt their mother. Once the term had been clarified to ensure that they understood the topic of discussion, the interviewees and groups were asked about the ways they evaluate children’s possible risk and about their knowledge of these situations and how to react. All the discussants agreed that their knowledge stems from their experience and that specific information about this topic is scarce. The socio-community workers asserted that they look for patterns and signals but autonomously, not in a way decided by their work superior; thus, they did not feel supported in this arena. This task was even more demanding for participants related to the security forces. Only two participants, a security force member and a socio-community worker, indicated that they had received multidisciplinary courses and education about children and gender violence. All said that there is no specific instrument that could help them evaluate the possible risk for children who are present when they respond to a case of gender violence. They rely on their visual scanning when they arrive at the home, which can provide relevant information about the event; then, after the emergency response, they ask primary care workers (pediatricians and teachers) for information. Workers at the social and community levels also considered it important to ask family treatment teams and social services for information. However, a common point that stood out was coordination among institutions, which is essential to obtaining a good picture of the GV problem and children’s risk. When talking about the key moments or critical incidents that could trigger this violence against the children, security forces workers highlighted drugs use, economic instability or personal conflicts, whereas the socio-community workers emphasized the father’s verbalizations and lies about the mother that the child ended up believing. Deeping on the threats, verbalizations, assaults, or conduct against children present at this emergency scene, security forces members indicated that the aggressors usually threatened the mother but also conveyed this threat to the children (who perceive such facial expressions and nonverbal language), whereas socio-community workers indicated that the aggressors usually played with the threat of not paying the child support, failure to comply with the visitation regimen, or verbalizations to discredit the mother. These two threats are present when the couple still lives in the same home, and the risk increases when they are apart. The statements or emotions that children usually express during the interviewees’ interventions in situations of gender violence range from remaining silent or even seeking their parents’ assent to being apathetic or experiencing difficulty expressing emotions and feelings, which is a signal of a complicated case in which children are at greater risk of being battered. However, children are not usually spoken to in these interventions, and both groups of workers highlighted the importance of paying attention to these signals. When asked about mothers, both groups stressed that mothers try to play down the situation as a way of protecting their children to keep them out the violence episode. However, children’s emotional reactions can contribute to clarifying possible risk. These professionals concurred that the direct and indirect consequences for the children of women victims include affecting their long-term learning about how to solve conflicts or normalizing the situation, among other issues. Nonetheless, the interviewees’ professional experience suggested several important indicators of risk relating to nonverbal clues, posture, the hygiene of both the children and the home during the first visual inspection, the smell of the home, and other visual signs. Finally, based on this collected information, the researchers performed the content analysis mentioned in the procedure section and extracted a pool of 22 items that included the relevant information about this problem provided by the experts. The items were accepted by consensus after a three-hour researcher group discussion about the proposed items. The proposed items were theoretically analyzed to further consider whether they represented similar issues. After a throughout analysis, the researchers concluded that the items involved four theoretical aspects: a) signals of current or previous violence, b) cognitive distortions, c) aggressive behavior, and c) emotional reactions. All items were worded positively to facilitate understanding and avoid the creation of an artificial factor (Dalal & Carter, 2015). Study 2. Quantitative Study. Debriefing: Evaluating the Items The 22 items extracted from Study 1 were included in a cognitive debriefing study to ascertain their suitability (clarity, difficulty, and adequacy) for inclusion as items in a scale for evaluating the risk of children living in an IPVAW context of suffering from instrumental violence. Method Participants and Procedure Of the 36 professionals involved in IPVAW response who were sent a Google form to complete, 26 (80.77% women = 21, 19.23% men = 5) responded to this cognitive debriefing questionnaire (M = 50.48 years old, SD = 7.177, range between 37 and 64 years old). Sixteen of these professionals came from the socio-communitarian sphere (61.54% of the participants), 7 from the legal and forensic sphere (26.92% of the sample), and 3 from the state security forces (11.54% of the total). The other ten responses were not included in the analysis: four were discarded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, and the other six were excluded due to missing responses. Participants in professional positions were recruited using incidental and snowball sampling. The inclusion criteria were that they worked directly with victims of IPVAW who had children younger than sixteen years old2 and that they had experienced at least one instance of responding to an emergency situation in which children were present. Participants were personally contacted, and once they provided informed consent to participate, they received a Google form containing the items, which they were asked to evaluate in terms of adequacy (the item was useful in this context, as this kind of aspect was present in a gender violence episode), difficulty (the situation is difficult to evaluate), and clarity (the item is clear, appropriate, and understandable). Instruments Each item was rated on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, and a space was provided at the end of each item where the respondents could provide an alternative statement of it. At the end of the form, participants were given additional space to indicate any other concerns or aspects related to the items or the concepts. Results The data were analyzed with the statistical package SPSS v.27. Analyses were based on descriptive, response frequency, and multivariate analyses to determine whether there were sex or profession differences or interactions. First, to analyze the adequacy, difficulty and clarity of each item, frequency tables were used to assess participant consensus (> 80%). In a group session with five researchers, these results were analyzed and discussed. The cut-off point to reject or not an item was established considering the consensus regarding the response. For adequacy and clarity, consensus had to be in responses over 3-points (i.e., accumulated frequency ≥ 80 in the participants’ responses to 4 and 5 points), whereas for difficulty consensus had to be in responses below 3-points (i.e., accumulated frequency ≥ 80 in the participants’ responses to 1 and 2 points). Participants’ responses showed that consensus was greater than 80% for 9 of 22 items (Items 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 12, 17, 18, and 21; see Table 1 for the means and standard deviations); the difficulty of the items was low (1 = not at all difficult to 5 = very difficult); the items were perceived as highly adequate for evaluating this context (1 = not adequate to 5 = highly adequate); and the clarity of the items was also considered high (1 = not clear to 5 = highly clear). However, a deeper analysis of qualitative responses showed that for one item, the interviewees proposed improvements to enhance its suitability. The researchers analyzed this item and the suggestions and decided to divide it into two parts, one referring to physical aspects and one referring to psychological aspects. In sum, these 9 items were maintained for the following step, and one was broken down into two items. Ten items were near consensus but failed to meet one of the three criteria (items 1, 3, 4, 10, 13, 15, 16, 19, 20, 22). In this case, the research group decided to remove 7 items and to change the wording of 3 (10, 13, 19). Finally, three items had little consensus and received numerous suggestions from the interviewees (6, 11, 14). Two of these were removed (in one case because the content was similar to Item 12, which was retained) and one was kept but the wording changed. In sum, of the initial 22 items, 13 were related to maintaining but improving wording, 9 were removed, and 1 item was newly included. Thus, fourteen items were considered for a final pretest prior to a general validation. These items reflected three of the four theoretical dimensions derived for Study 1: a) signals of current or previous violence, b) aggressive behavior, and c) emotional reactions. The cognitive distortions dimension was dropped from subsequent studies. It was considered unsuitable because workers are rarely able to talk to children in intervention situations, and it is thus difficult to address this aspect. Table 1 Means and Standard Deviations for Items in Study 2   Note. 1 Items retained for the pretest study; 2 item split into two items; 3 wording of these items changed. The rest of items were rejected. The main aim of this third study was to determine the frequency with which workers acting in an emergency situation involving gender violence encounter children present at the scene. These workers are asked to evaluate based on their experience whether this situation is a signal of the children’s risk of being instrumentalized. Thus, this pretest study was carried out only with members of security forces (police and civil guard). There were two reasons for this decision. The first was that most emergency cases are first announced to these professionals, who can respond with or without social service workers; the second is that the previous cognitive debriefing study showed some differences between the two groups (socio-community and security force workers) regarding question suitability, many of which were related not to the first emergency response, but to the watching of children in many other contexts (e.g., school). Focusing on the security forces group, however, made it more difficult to obtain responses, as fewer respondents had such an experience, and other external variables ceased to engage their participation (e.g., responding via Google form). Therefore, two researchers contacted these professionals and administered a google form or a paper-and-pencil questionnaire depending on their preferences. Method Participants and Procedure The questionnaire was evenly distributed. The inclusion criteria were to be member of a state force (police or civil guard) and to have attended an IPVAW emergency episode in their professional act. Forty-four questionnaires were returned (93.18% men, 20 civil guards and 21 policemen; 6.82% women, 3 police). The mean age was 44.68 years (SD = 7.65, range = 24-59). All of the returned questionnaires pertained to professionals who have had experience in this type of situations, where children were exposed and present at the aid episode. Regarding frequency, the majority have intervened in more than 10 times (44.7%), followed by 1 to 5 times (31.6%) and 6 to 10 times (23.7%). Table 2 Descriptive Statistics and ANOVA Results for Items in Study 3   Note. 1 Items retained for the pretest study. The subscripts indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between the two security forces (police vs. civil guard). Instrument The participants received a 14-item questionnaire (see Table 2 for items), derived from Study 2, with a response format on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. First of all, they informed consented to participate. Then, information about their age, sex, educational level, and their specific security force category (police or civil guard) was gathered. Finally, participants were asked whether they had intervened in a gender violence emergency, the frequency (less than 5 times, between 5-10 times, or more than 10 episodes), and whether there were (or not) children exposed in those situations (see instructions in Appendix). At the end of the form, participants were given additional space to indicate any other concern or aspect related to the items proposed. Results ANOVAs of each item showed that both types of agents shared perceptions of children’s behavioral frequency, except for Item 4, which refers to children’s verbalizations about previous violence at home, as the perceptions of civil guards were higher than the perceptions of police officers (F = 13.39, p = .001; see means and standard deviations for all items in Table 2). Regarding the perceptions of children’s risk, three items yielded significant differences between policemen and the civil guard. These items were 1 (the child is crying; F = 6.50, p = .015), 2 (the older child plays a parental role with his or her brother or sister; F = 6.44, p = .016), and 10 (the child justifies, normalizes or minimizes the aggressor’s behavior; F = 8.86, p = .005). In all three cases, civil guards perceived these situations as indicating greater risk than did police officers (see Table 2). In general, civil guards scored all evaluations of risk higher than police officers, while in all evaluations of frequency, police officers reported higher frequency of Items 8 (the child expresses anger and violence against the mother) and 9 (the child shows negative reactions such as emotional block, silence or fear) than civil guards did. However, there were no significant differences in these items between worker groups (see Table 2). Despite the small sample size, conducting an exploratory factor analysis could reveal interesting patterns (de Winter et al., 2009). An exploratory analysis was performed to test the strength of the items in the theoretical dimensions. To examine the risk criteria, the principal component extraction method was applied. The Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy measure was calculated, indicating a value of .83, and Bartlett’s test was statistically significant, χ2(91) = 436.199, p < .001, thus making the application of factor analysis pertinent. The varimax rotation procedure was used. The analysis revealed three components: a) negative reactions and ambiguity, b) previous maltreatment, and c) an active role in the situation. These components resembled the theoretically driven components (signals of current or previous violence, aggressive behavior and emotional reactions); however, the researchers discussed the content and decided that new labels were more suitable for the final scale. The main reason for adopting this decision was that former labels were more general and, for example, could include positive or negative reactions for the emotional reactions component when a higher risk is only related to negative reactions or the active role not always has to be aggressive. Thus, we think the final labels are more accurate and descriptive of the situation of children risk in IPVAW. Finally, for a closer look at each item’s response ranking (1-5), the graphs by work group (police and civil guard) illustrate that the lower the frequency of the situation, the greater the risk. This was the case for Items 3, 4, and 7. Items 2 and 12 were perceived as frequent situations and as indicators of children’s risk. For four items, the discrepancies between the two groups were high. In all cases, civil guards considered items 1, 2, 9, and 10 to reflect a situation of high risk for children experiencing gender violence. Items 1, 2, and 10 yielded significant differences between groups, but Item 9 did not. In this case, most policemen showed a central response tendency, which may reflect the absence of a clear position about the risk of these situations. Items 8, 11, 13, and 14 showed low frequency and suggested low risk for children; therefore, they were rejected as possible indicators. Finally, Item 5 is not frequently observed in an IPVAW situation, and the perception of risk was unclear, as indicated by the evenly distributed scores. For Item 6 the frequency was differently perceived, but it was still considered an indicator of possible risk for children. In sum, items 3, 4, 6, 7, and 12 are clear indicators of a higher level of risk of being instrumentalized for children who are experiencing gender violence. All items relate to the signals of possible previous maltreatment, except for Item 12, which indicates an active role of the child in relation to the mother. We performed another exploratory factor analysis. The Kaiser Meyer Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy measure was calculated, indicating a value of .68, and Bartlett’s test was statistically significant, χ2(10) = 71.138, p < .001, thus making the application of factor analysis pertinent. The varimax rotation procedure was used. The analysis yielded one factor with a Cronbach’s α = .81 The law in Spain considers children exposed to IPVAW as direct victims of abuse, but as yet children are not considered in first-response interventions by state security forces. Mothers are spoken with in these situations, but they minimize their children’s risk in these cases; however, their perception changes when they are able to be apart from their aggressors and become aware that their children are at risk. Therefore, in many cases, professionals’ risk assessment is limited due to the mother-complainant’s subjective perceptions of risk (Cullen & Fritzon, 2019). In most cases, mothers underestimate risk as a consequence of cognitive biases such as normalization, minimization, and justification of parental violence. Thus, the way to prevent the instrumentalization of children, and even their murder, must be to evaluate risk earlier. The items that were ultimately determined to be clear indicators of this risk primarily concerned simple observations that state forces can perform when attending these cases. If the child shows an active role in the situation, or if there are signs of possible maltreatment, these may be indicators to act immediately regardless of what the mother says, as mothers are also victims who try to minimize and normalize the situation; thus, they may not be in the best position to respond to questions that could be considered as acting against the father. However, the absence of action when the child is actively involved in such situations can be fatal. The high concordance between the police and the civil guard (Study 3) and between the police and the socio-community workers (Study 2) aligns with the findings of Galera et al. (2023). To further advance this research, it is necessary to overcome our difficulties in obtaining answers from security forces. Coordination among the various areas involved must also be improved. However, less attention has been given to both children and professionals. Therefore, professionals must have effective tools for assessing situations that reduce these limitations, as well as institutional coordination at judicial, health, educational, and social levels, to avoid children’s revictimization and to encourage the appropriate care of a victim by the judicial system and the social, health, security forces, and organizations responsible for assisting victims, investigating the offence and/or conducting proceedings (Campbell, 2005). Moreover, new workers often lack enough information and training to act in these cases and need clear indicators based on the experience of other professionals who help in such situations. Furthermore, these professionals need more evaluation instruments and training in these aspects. The good news is that professionals are ready to help and eager to propose how to respond better in these cases. It is important to hear the voices of those who respond in these situations and to consider the multiple obstacles they face. Indeed, we have detected a great willingness of professional workers in IPVAW contexts to contribute their knowledge, but they still perceive that sometimes this is used politically and are reluctant to do so at first. Thus, breaking this barrier is important for ensuring objectivity and unquestionable action. The Forensic Medical Council of Spain (Consejo Médico Forense, 2020) reports that the assessment of risk is not usually requested by judicial actors. Thus, it is necessary to advocate that the judicial authorities and the Prosecutor’s Office request these evaluations. In this regard, we consider it essential to enhance forensic risk assessment by forensic assessment units and by the Administration of Justice in so-called cases of special relevance in which children in a situation of vulnerability are identified. Thus, the following step should be to test these items in real situations in which professionals can evaluate their accuracy. Moreover, the gender proportion of professionals should be more balanced. In our sample, the percentage of participants resembled reality, but incorporating more professionals could help obtain a broader picture of the cases. Furthermore, studies 1 and 2 include more women than men, whereas in study 3 the proportion is reversed. Despite these matches to the reality, gender differences could condition the results and, thus, future studies should analyze this issue. In doing so, we could validate the present factor structure and propose a short measure to respond to the new needs derived from the L. O. 8/2021. Despite the need for further work, the present study lays the foundation for this proposal. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Notes 1 This overrepresentation of female workers is representative of the proportion of professionals in this area, mainly psychologists, social workers, or educators, among others. 2 Although the legal age in Spain is 18, from the age of 16 the civil code regulates that children may emancipate themselves and consent to have relations, work or perform administrative matters. Acknowledgments The authors sincerely thank all the professionals who participated in this study for providing their knowledge, thoughts, and concerns about this issue. The authors are also grateful to Salud María Ruiz Sánchez and Inés López Pérez for their insightful contributions. Cite this article as: Ríos Lechuga, J. C., Alarcón Cuenca, J. M., & Lopez-Zafra, E. (2024). Development of an index to evaluate children’s risk for being instrumentalized in intimate partner violence against women contexts. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 16(2), 77-86. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a7 Funding: This study was funded by the Instituto de Estudios Giennenses (IEG). Diputación Provincial de Jaén (Spain). Informed Consent Statement Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Institutional Review Board Statement This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Jaén, Spain (Code: CEIH 160215-1). The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. References Appendix Instructions for Study 3 Imagine yourself in an emergency situation, and you are the first person to get there. There is a scene where a case of intimate partner violence involving children under 16 years old is reported or suspected. Please, to what extent you consider the following statements to be adequate to enable you to know the level of urgent risk of vicarious violence. To answer use the following scale depending on whether that situation occurs frequently and whether it is an indicator of risk of vicarious violence (based on your experience you consider that such a situation indicates a low to high risk). To evaluate the usefulness of these items to evaluate the possible risk of these children, please indicate at the end of this questionnaire, in the space left for it, the comments you deem appropriate. Thank you very much for your cooperation. |

Cite this article as: Lechuga, J. C. R., Cuenca, J. M. A., & Lopez-Zafra, E. (2024). Development of an Index to Evaluate Children’s Risk for Being Instrumentalized in Intimate Partner Violence against Women Contexts. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 16(2), 77 - 86. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2024a7

Correspondence: elopez@ujaen.es (Esther Lopez-Zafra).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS