Forensic Psychological Harm in Victims of Child Sexual Abuse: A Meta-analytic Review

[Daño psicolĂłgico forense en vĂctimas de abuso sexual infantil: una revisiĂłn metaanalĂtica]

Blanca Cea1, Álvaro Montes1, Alexander Trinidad2, & Ramón Arce1

1Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Spain; 2University of Cologne, Germany

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a10

Received 30 April 2025, Accepted 21 July 2025

Abstract

Background/aim: In child sexual abuse (CSA) cases, the forensic evaluation of psychological harm is crucial for substantiating victim testimony and informing compensation awards. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is the primary diagnosis for assessing forensic harm, as it establishes the causal link between the harm and the CSA event. Thus, a meta-analysis was conducted to estimate the effect of CSA victimization on PTSD development and the probability of resulting psychological harm, and to determine the incremental harm attributable to CSA victimization. Method: A total of 126 primary studies were selected, yielding 195 effect sizes and a cumulative sample of 29,517 victims. Random effects psychometric meta-analyses were performed, correcting effect sizes for sampling error and criterion unreliability to obtain the true effect size (δ). Results: An overall large true effect size (δ = 0.93) was found between CSA victimization and PTSD outcomes. Given the heterogeneity of the studies, moderating variables were examined, revealing that female victims (δ = 0.99), intrafamilial abuse (δ = 1.68) and penetrative acts (δ = 1.23) were associated with significantly higher psychological harm attributable to CSA victimization than males (δ = 0.68), extrafamilial abuse (δ = 1.24) and non-penetrative sexual touching (δ = 1.01), respectively. The prevalence of PTSD diagnosis in CSA survivors was estimated at 33.95%. The incremental harm due to CSA victimization was estimated at 42.2% in general, with specific higher rates for intrafamilial abuse (64.3%) and for victims of penetration (54.4%). Conclusions: These findings provide robust evidence of the psychological harm (PTSD) resulting from CSA victimization and identify specific abuse characteristics that exacerbate such a harm. The judicial implications for the burden of proof are discussed and gold standards for civil compensation to victims are suggested as follows: a general gold standard of 42.2% for victims of CSA, and higher gold standards for victims of intrafamilial abuse (64.3%) and victims of penetration (54.4%).

Resumen

Antecedentes/objetivo: En casos de abuso sexual infantil (ASI), la evaluación forense del daño psicológico es crucial para sustentar el testimonio de la víctima y estimar las compensaciones. El Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (TEPT) es el diagnóstico primario para establecer dicho daño, ya que establece el nexo causal entre la sintomatología y la victimización. Por ello, se realizaron metaanálisis con el objetivo de cuantificar el efecto de la victimización por ASI en el desarrollo del TEPT, estimar la probabilidad de daño psicológico y determinar el incremento del daño atribuible a dicha victimización. Método: Se seleccionaron un total de 126 estudios primarios, de los que se extrajeron 195 tamaños del efecto, con una muestra acumulada de 29,517 víctimas. Se ejecutaron metaanálisis psicométricos de efectos aleatorios, corrigiendo los tamaños del efecto por error de muestreo y fiabilidad del criterio para obtener el tamaño del efecto verdadero (δ). Resultados: Los resultados mostraron, para la relación entre la victimización por ASI y el daño psicológico, un tamaño del efecto verdadero promedio general de magnitud grande (δ = 0.93). Dada la heterogeneidad en los estudios primarios, se examinaron los efectos de las variables moderadoras, encontrando que las mujeres y niñas víctimas (δ = 0.99), de abuso intrafamiliar (δ = 1.68) y de abuso con penetración (δ = 1.23) presentaron un daño psicológico significativamente mayor que los hombres y niños víctimas (δ = 0.68), de abuso extrafamiliar (δ = 1.24) y de tocamientos sin penetración (δ = 1.01), respectivamente. La prevalencia del diagnóstico de TEPT en víctimas de ASI se estimó en un 33.95 %. El incremento del daño psicológico atribuible a la victimización por ASI se estimó en un 42.2 % en general, con estimaciones mayores para las víctimas de abuso intrafamiliar (64.3 %) y para las víctimas de penetración (54.4 %). Conclusiones: Los resultados dan pruebas convincentes del daño psicológico (TEP) a consecuencia de la victimización del abuso sexual infantil (ASI) y detectan características que agravan dicho daño. Se comentan las implicaciones jurídicas del peso de la prueba y se proponen criterios de referencia para compensar civilmente a las víctimas: un criterio de referencia general del 42.2% para las víctimas del ASI y mayor aún para las víctimas de abuso intrafamiliar (64.3%) y de penetración (54.4%).

Keywords

Posttraumatic stress disorder, Forensic evaluation, Victimization, Burden of proof, Forensic expertise, Compensation to victimsPalabras clave

Trastorno de estrĂ©s postraumático, EvaluaciĂłn forense, VictimizaciĂłn, Carga de la Prueba, Pericial forense, CompensaciĂłn a vĂctimasCite this article as: Cea, B., Montes, Á., Trinidad, A., & Arce, R. (2025). Forensic Psychological Harm in Victims of Child Sexual Abuse: A Meta-analytic Review. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 111 - 129. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a10

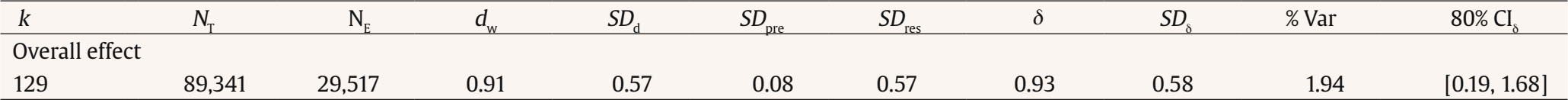

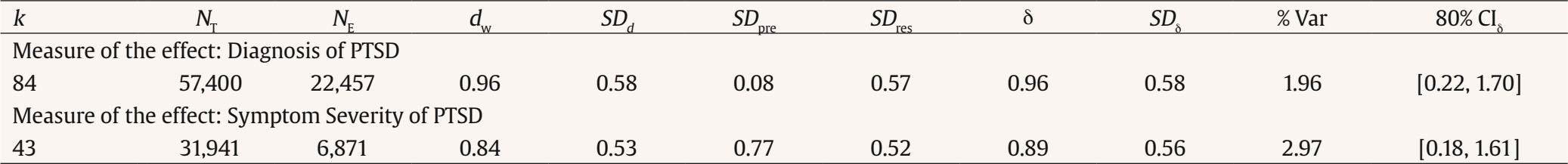

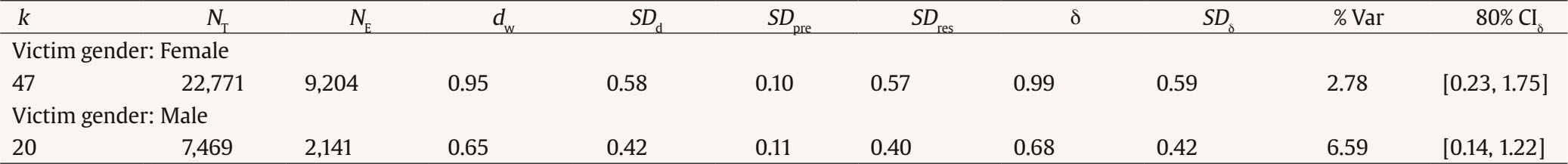

Correspondence: ramon.arce@usc.es (R. Arce).Child sexual abuse (CSA) represents a severe manifestation of child maltreatment and constitutes a severe violation of children’s rights (Simon et al., 2020; United Nations [UN, 1989]). It is recognized as one of the most harmful forms of trauma, associated with a wide range of adverse outcomes, including physical (Downing et al., 2021; Irish et al., 2010; Pulverman et al., 2018), psychological (Fergusson et al., 2013; Gardner et al., 2019; Hashim et al., 2024), behavioral (Hailes et al., 2019; Mii et al., 2024), social (Batool, 2017; Daignault & Hebert, 2009), and sexual problems (Labadie et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023). According to a recent study examining literature from 1990 to 2023, the estimated worldwide prevalence of CSA was approximately 19% for females (with variations between 16.0 and 25.2%) and 15% for males (with variations between 9.5 and 23.5%) (Cagney et al., 2025), highlighting the alarming scale of this phenomenon. CSA research is subject to methodological issues due to varying legal definitions across different regions and countries, depending on factors such as the age of sexual consent, whether an age difference between parties is specified, and the types of acts that constitute sexual abuse (Kilimnik et al., 2018; Mathews & Collin-Vézina, 2019). Given these wide variations, the World Health Organization [WHO, 1999] established a universal criterion, defining CSA as “the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to, or for which the child is not developmentally prepared” (pp. 15-16). Thus, CSA typically involves activity between a child and an adult—or another child who holds a position of responsibility, trust, or power due to age or development—with the activity intended for sexual gratification. Consequently, CSA encompasses a range of acts, including non-contact abuse (e.g., exposure, unwanted sexual propositions), contact abuse (e.g., fondling, genital touching), and intercourse (anal, vaginal, or oral penetration) (Fergusson et al., 2013; Finkelhor, 1994). In a judicial setting, as defined by UN (1985), a victim is characterized by the harm suffered as a consequence of a crime. This harm can vary in nature, including emotional suffering or psychological injury. Forensic psychological evaluation assesses this injury by quantifying the effects of the alleged crime on the victim’s mental health (Seymour et al., 2013; Vilariño et al., 2013; Young et al., 2025), thereby documenting evidence of the CSA victimization and supporting the victim’s testimony (Arce, 2017; Goodman-Delahunty & Foote, 2009; Vallano et al., 2013). This assessment becomes crucial in CSA cases, where direct corroborating evidence, such as eyewitness or physical findings is often scarce, frequently leaves the complainant’s evaluation as the primary source of information (Herman, 2010; Hershkowitz et al., 2018). Within the scope of these forensic evaluations, psychological harm assessment focuses on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or acute stress disorder (ASD; limited to the period from 3 days to 1 month following the traumatic event). These psychiatric disorders are distinct from other disorders because they requires that the clinical symptoms be directly linked to the traumatic event (Criterion A) (Blanchard & Hickling, 2004; Ellekilde et al., 2021; McCloskey & Walker, 2000). According to the DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Association [APA, 2022]), a PTSD diagnosis entails the presence of symptoms distributed across four clusters: (1) intrusion symptoms (e.g., re-experiencing the trauma through memories, nightmares, flashbacks); (2) avoidance (efforts to evade trauma-related stimuli); (3) negative alterations in cognitions and mood (e.g., persistent negative beliefs, emotional numbing); and (4) alterations in arousal and reactivity (e.g., hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response, irritability). Furthermore, in a judicial setting, the suspicion of malingering (the intentional simulation or exaggeration of symptoms) must be assessed in line with the presumption of innocence principle (no innocent should be sentenced) (Arce, 2017; Melton et al., 2017; Puente-López et al., 2024). Additionally, to establish a causal link, the evaluation must rule out other stressful life events experienced by the victim as the cause of their symptomatology (Young et al., 2025). Regarding comorbidity, PTSD frequently co-occurs with other mental health conditions, including depression or anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 2005; MacDonald et al., 2010; Mureanu et al., 2022; Oquendo et al., 2003). In a forensic setting, such comorbid conditions, in the absence of a primary PTSD diagnosis, are insufficient evidence of psychological harm because they fail to establish a causal link between the victimization by CSA and the reported psychological harm (Arce, 2018; Goodman-Delahunty & Foote, 2009; Melton et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the presence of these disorders alongside PTSD typically indicates a greater severity of psychological harm (Kessler et al., 2005; Konstantopoulou et al., 2024; Marshall et al., 2001). Furthermore, PTSD subsyndromes (when a victim experiences significant PTSD symptoms but Criterion A—in our case, CSA victimization—is not fulfilled) do not meet the threshold required to constitute forensic psychological harm (O’Donnell et al., 2006). In relation to its course, the duration of PTSD can be extensive, sometimes lasting for more than 50 years (i.e., a lifespan) (APA, 2022). The disorder can manifest with a delayed onset (at least 6 months passing between the traumatic event–CSA victimization–and the onset of full PTSD symptoms; APA, 2022). It can also manifest with delayed expression, in which some symptoms appear immediately after the event but meeting the full criteria is delayed (APA, 2022). This delayed presentation is particularly relevant, as significant symptoms may not manifest during childhood but can emerge or become more pronounced in adulthood (Ellekilde et al., 2021; O’Donnell et al., 2013). This delayed onset is particularly relevant considering that young children may not exhibit internalizing symptoms necessary for the forensic evaluation mandate of establishing a causal link between the CSA victimization and the PTSD (J. A. Cohen et al., 2010; Dyregrov & Yule, 2006; Scheeringa et al., 1995); instead, the immediate impact of trauma often manifests through behavioral dysregulation or distress reactions (McLaughlin & Peverill, 2020). Moreover, the trajectory of PTSD is not uniform, involving periods of chronic symptoms, or waxing and waning of symptoms. (Handiso et al., 2025; Miller-Graff & Howell, 2015; Putnam & Trickett, 1993). Although the psychological impact on CSA survivors might be broadly perceived as uniform, the literature has identified potential factors that moderate the risk for developing PTSD and its severity (APA, 2022; McTavish et al., 2019). These factors, in a context of CSA victimization, include individual characteristics, such as the victim’s age and gender (Assink et al., 2019; Bulik et al., 2001) or history of prior trauma (Gould et al., 2021; Suliman et al., 2009), specific characteristics of the abuse, like the type of acts (e.g., no contact, contact, intercourse) (Fergusson et al., 2013; Jonas et al., 2011), the victim-perpetrator relationship (Koçtürk & Yüksel, 2019; Molnar et al., 2001), and the duration of the abuse (Batchelder et al., 2021; Gokten & Uyulan, 2021). Post-abuse experiences can also shape the outcomes, such as the availability of social support after disclosure (Cea et al., 2022; Fletcher et al., 2021) and interaction with the judicial system (Campbell & Raja, 1999; Quas & Goodman, 2012). Given the acknowledged heterogeneity in PTSD outcomes (Alves et al., 2024; Haag et al., 2023) and contradictory findings regarding how specific characteristics of abuse affect psychological harm in CSA survivors (Boumpa et al., 2024; Hailes et al., 2019; McLean et al., 2014; Nagtegaal & Boonmann, 2022), this study suggests a meta-analysis to synthesize existing research. The primary objectives were to determine the effect of CSA victimization on PTSD development, the probability of resultant psychological harm, and the incremental harm attributable to CSA victimization. Additionally, to better understand the observed outcome variability, this investigation examined key moderators identified in literature, including measurement type (diagnosis and symptom severity), victim gender, abuse type, and perpetrator relationship. Such findings are crucial for advancing forensic assessment and informing evidence base for economic compensations to victims’ harm with delayed onset or expression (UN, 1989). Search of Studies The literature search aimed to identify those studies addressing the development of PTSD or ASD in victims of CSA. To achieve this, a comprehensive and sensitive multi-source search was conducted employing several meta-search strategies. First, existing systematic and meta-analytic reviews on this topic were identified, and the primary studies that they include were examined. Subsequently, systematic searches were conducted in scientific references databases (Web of Science, Scopus, Pubmed, PsycInfo, and Dialnet), in the ProQuest Dissertations & Theses databases, and in the academic search engine Google Scholar. In the initial search, terms were combined as follows: (child*) AND (sexual abuse OR sexual victimization OR sexual maltreatment) AND (post-traumatic stress disorder) OR (acute stress disorder). To these initial descriptors, those identified in the sources (e.g., adolescent sexual abuse, child molestation, child sexual violence, CSA survivors, incest, childhood sexual trauma,) were added until an exhaustive search was completed. Additionally, a “snowball” procedure was conducted by screening the bibliographies of eligible articles for further potentially suitable studies. Study Selection Criteria Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) participants reported exposure to CSA prior to the age of 18 years (WHO, 1999), the study clearly set the definition of CSA used and the criteria for classifying participants as victims (e.g., self-reported or substantiated); (2) studies provided descriptive data on the sample characteristics (e. g., gender, age, sample size); (3) studies reported an evaluation of PTSD (or ASD), either as a dichotomous variables (e.g., a psychologist/psychiatric diagnosis or meeting a specific cutoff on a scale) or as continuous variable (i.e., a measure of symptom severity using psychometric instruments); and (4) studies reported the effect sizes for the association between CSA and PTSD/ASD, or provided sufficient data from which an effect size could be derived. Studies not meeting the specified criteria were excluded from this review. Specifically, studies were excluded if they did not report a direct and isolated effect of CSA on PTSD. This includes studies referring to general childhood abuse without a specific focus on CSA; studies comparing CSA with other forms of maltreatment (such as physical abuse or neglect) without distinctly reporting the CSA-PTSD association; and studies where the CSA-PTSD relationship was only reports within multivariate models (e.g., multiple regressions), as the effect in such models is inherently presented as moderated by or adjusted for other covariates. Furthermore, studies were excluded if they did not provide a general measure of PTSD, offering instead only subscales scores or specific symptoms. Exclusion also was applied to studies for which the data required for calculating effect sizes were unavailable, even after contacting the authors. Additionally, studies presenting data errors, such as unexplained inconsistencies in group sizes not attributable to missing data, were removed. Finally, to ensure the independence of samples, if multiple publications reported on the same or overlapping samples, the study providing the most comprehensive information was selected. After the screening, 126 primary studies were selected (see PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1), with a cumulative sample of 89,341 subjects, of whom 29,517 were CSA survivors, obtaining a total of 195 effect sizes (see Appendix). Data Extraction The data from the included studies were coded according to the following categories: a) primary study reference; b) document type (i.e., journal article, doctoral thesis, conference proceeding, book, unpublished study); c) sample characteristics (i.e., size, age, gender, country, data collection context); d) measures of PTSD or ASD (i.e., clinical diagnosis, symptom severity scores); e) measures of CSA (i.e., self-report, official records, validated questionnaire); f) reliability of the measurement instruments; and g) moderators (i.e., gender, type of abuse, relationship with the perpetrator, type of PTSD measure). The Appendix presents a summary of the characteristics of the primary studies included in the present meta-analysis. All the studies were coded independently by two experienced and trained researchers. To ensure consistency, each rater re-coded 50% of the studies (for intra-rater reliability). Both between-rater and within-rater agreement were assessed using the true kappa (; Fariña et al., 2002). This measure corrects for chance agreement and ensures only exact coding matches are considered agreements, controlling for systematic error. The assessment revealed total concordance ( = 1); thus, the coding process was deemed reliable, indicating that other trained raters would likely achieve the same results (Wicker, 1975). In relation to moderators, a successive approach procedure was employed (Vilariño et al., 2013) to identify and define moderators. This consisted of scanning by the two raters the selected papers searching for moderators. Identified potential moderators and categories were discussed and a consensus was reached by the raters. As a result, four moderators of relevance for a testimony were coded: 1) gender (categories: male and female), 2) type of abuse (categories: no-contact, touching and penetration), 3) victim-perpetrator relationship (categories: intrafamilial and extrafamilial perpetrator), and type of PTSD measure (categories: diagnosis and symptom severity). Data Analysis Random effects psychometric meta-analyses of primary studies were performed (Schmidt & Hunter, 2015). Initially, effect sizes were standardized as Cohen’s d. These were either extracted directly from primary studies or transformed from other statistics (e.g., odds ratio, r, χ2) using established formulas (J. Cohen, 1988; Rosenthal, 1994). When means and standard deviations were available for PTSD measures for each group, Cohen’s d was computed (or Hedges’ g in cases of unequal sample sizes or heterogeneity of variances); when data for PTSD were provided in probabilities prevalence ratio or Cohen’s h was computed and converted to Cohen’s d; when other statistics (e.g., χ2) were reported in the primary studies, Cohen’s d was estimated; and when other than Cohen’s d effect size for the relationship between PTSD and CSA victimization (e.g., odds ratios, correlation coefficients) were reported in primary studies, they were converted to Cohen’s d. For studies reporting multiple effect sizes across distinct subsamples, a weighted composite score was derived to establish an overall effect size. In cases where a study lacked a control comparison group, the normative sample from the creation and validation study of the psychometric PTSD instrument was employed as the control group. Following this, effect sizes were adjusted for sampling error and, where applicable, for criterion unreliability. Consequently, the following key statistics were calculated: the effect size weighted for sampling error (dw), the standard deviation of d (SDd), the standard deviation of d predicted by artifactual errors (SDpre), the residual standard deviation after removal of variance due to artifactual errors (SDres), the mean true effect size, representing d also corrected for criterion unreliability (δ), along with its standard deviation (SDδ), the percentage of variance explained by artifactual errors (%Var); the 95% confidence interval for d (95% CId), and the 80% confidence interval for δ (80% CIδ). Statistical significance was determined using the 95% CId, if this interval excluded zero, the average effect size was considered significant. Generalizability was assessed using the 80% CIδ, a lower limit above zero suggested the finding would likely extend to a substantial proportion (e.g., 90%) of potential studies. Additionally, & VAR was examined, with values below 75% (Hunter et al., 1982) indicating heterogeneity and the potential presence of moderators. The magnitude of the mean true effect size (δ) was interpreted qualitatively using Cohen’s (1988) established categories: “small” (d = 0.20), “moderate” (d = 0.50), and “large” (d = 0.80); occasionally augmented with “more than large” category for d > 1.20 (Arce et al., 2015). To assess the quantitative implications for forensic practice, the Probability of Superiority (PSES) was calculated (Monteiro et al., 2018; Montes et al., 2022). PSES is an estimation of the probability that the score of a person from the CSA victim group will exceed the score of a person from the control group (e.g., d = 1.20 corresponds to PSES = .8023, indicating the effect size is larger than 80.23% of all possible effect sizes; d = 0.80 to PSES = .7157; d = 0.50 to PSES = .6368; and d = 0.20 to PSES = .5557). Finally, a variation of the BESD (Corrás et al., 2017) was used to estimate the severity of the psychological harm. Criterion Unreliability Effect sizes were corrected for both sampling error and the unreliability of the PTSD criterion measure. Reliability estimates for the PTSD measure were sourced directly from the primary studies whenever available; otherwise, they were obtained from instrument validation studies. Analysis of Atypical Values An exploratory analysis of the distribution of primary data revealed one effect size (d = 6.86; Gwandure, 2007) classified as an extreme value (± 3 * IQR) and another effect size (d = 4.84; Costa et al., 2016) classified as an outlier (± 1.5 * IQR). Given their exceptionally high magnitudes, the observed values of these effects indicated they were unlikely to represent merely inconvenient or spurious findings. Consequently, both effect sizes were removed from the meta-analysis. Overall Effect The meta-analytic results for the overall effect of CSA on PTSD (see Table 1) exhibited a significant, Z = 16.49, p < .001, positive (confirming a positive relationship between child sexual abuse victimization and suffering PTSD), generalizable (the minimum expected effect, lower bond, was δ = 0.19) across studies and of a large magnitude (δ > 0.80) mean true effect size (δ = 0.93; an effect size above 74.5% of all possible effects, PSES = .745). In terms of quantifying such injury, the individuals with a history of CSA (CSA victims) reported 42.2% (r = .422) higher severity on PTSD measures (incremental harm due to victimization) than of those without such a history (CSA non-victims). Table 1 Meta-analyses of the Overall Effect of CSA Victimization and Forensic Psychological Harm (PTSD)   Note. k = number of effect sizes; NT = total sample size; NE = CSA group sample size d = sample size weighted mean effect size; SDd = standard deviation of d; SDpre = standard deviation predicted for sampling error alone; SDres = standard deviation of d after removing sampling error variance; δ = mean true effect size; SDδ = the standard deviation of δ; % var = percent of observed variance accounted by artifactual errors; 80% CIδ = 80% credibility interval for δ. Nevertheless, the effect sizes derived from the primary studies were heterogeneous: all artifacts accounted for 1.94% of δ observed variance, which is below the 75% threshold criterion, indicating that the variability in the overall effect is influenced by moderators (i.e., the remaining variance is systematic). The content analysis of the primary studies identified four potential moderators for further examination: victim gender (female and male), type of PTSD measure (diagnosis and symptom severity), relationship between the perpetrator and the victim (intrafamilial and extrafamilial perpetrator), and the type of abuse (no-contact, touching and penetration). Study of the Psychological Harm Measurement Type Moderator Two categories of outcome measures for PTSD were observed in the primary studies: PTSD diagnosis (a clinical categorical measure) and the severity of the harm (a quantitative psychometric measure). The diagnosis category included studies where the PTSD diagnosis was made by a clinician, psychologist or psychiatrist, or when a validated scale was applied specifying a cutoff point above which a clinically significant PTSD diagnosis was established. On the other hand, the severity of injury was measured by applying psychometric instruments designed to evaluate PTSD symptoms. Firstly, examining the results for PTSD diagnosis (see Table 2), the analysis displayed a significant, Z = 11.27, p < .001, positive (higher diagnosis of PTSD in CSA victims than in CSA non-victims), and of large magnitude (δ > 0.80) mean true effect size (δ = 0.96; an effect size above 75.2%, PSES = .752). This effect was found to be generalizable across studies (lower bond of the credibility interval = 0.22), but with heterogeneous distribution of the population effect sizes (the artifactual components of variance in δ accounted for 1.96% of the total variance), suggesting that the overall effect is mediated by moderators. Addressing the impact of psychological harm, when the observed mean effect size was converted to a probability, it indicated that CSA victims have a 21.3% increased probability (p = .213) of meeting a PTSD diagnosis over non-victims. Table 2 Meta-analyses of CSA Victimization and Forensic Psychological Harm (PTSD) Type of PTSD Measure Moderator   Note. k = number of effect sizes; NT = total sample size; NE = CSA group sample size d = sample size weighted mean effect size; SDd = standard deviation of d; SDpre = standard deviation predicted for sampling error alone; SDres = standard deviation of d after removing sampling error variance; δ = mean true effect size; SDδ = the standard deviation of δ; % var = percent of observed variance accounted by artifactual errors; 80% CIδ = 80% credibility interval for δ. Additionally, regarding the overall prevalence, data from a subset of studies (k = 73, cumulative N = 12,993) that directly reported the probability of PTSD diagnoses among individuals with a history of CSA were used. A weighted prevalence calculated from this subset yielded an estimated PTSD prevalence of 33.95% in CSA survivors. Likewise, the results for the PTSD symptom severity (psychometric measure) (see Table 2) illustrated a significant, Z = 11.55, p < .001, positive (high severity in CSA victims) and of a large magnitude (δ > 0.80) mean true effect size of δ = 0.89 (effect size above 73.6% of all possible effects, PSES = .736). Quantitatively, victims of child sexual abuse endorsed a greater 40.7% (r = .407) score in PTSD symptom severity (incremental harm linked to victimization) than non-victims. This effect also appears to be generalizable (credibility interval lower bond = 0.18), but influenced by moderators (2.97% of variance attributable to artifacts). Comparing these two measurement approaches for psychological harm, the analysis revealed that the observed effect was significantly higher when measured via PTSD diagnosis (δ=0.96) than when measured in terms of symptom severity (δ = 0.89), q(N’ = 1,480) = .096, Z = 2.61, p = .009. Study of the Effect of the Gender Moderator The meta-analytic results for female victims (see Table 3) displayed a significant, Z = 10.26, p < .001, positive (female CSA victims scored higher in PTSD than CSA non-victims) , generalizable across studies (minimum expected effect, lower bound was 0.23), and of a large magnitude (δ > 0.80) mean true effect size(δ = 0.99, above 75.8% of all effects, PSES = .758). As for severity of psychological harm, female victims reportedly experienced 44.4% (r = .444) more PTSD (incremental harm due to victimization) than non-victims. Table 3 Meta-analyses of CSA Victimization and Forensic Psychological Harm (PTSD) for the Gender Moderator   Note. k = number of effect sizes; NT = total sample size; NE = CSA group sample size d = sample size weighted mean effect size; SDd = standard deviation of d; SDpre = standard deviation predicted for sampling error alone; SDres = standard deviation of d after removing sampling error variance; δ = mean true effect size; SDδ = the standard deviation of δ; % var = percent of observed variance accounted by artifactual errors; 80% CIδ = 80% credibility interval for δ. As for male victims (see Table 3), the analysis revealed a significant, Z = 6.37, p < .001, positive (male CSA victims scored higher in PTSD than CSA non-victims), generalizable across studies (minimum expected effect, lower bound was 0.14), mean true effect size (δ = 0.68). However, the magnitude of the effect was moderate (0.50 < δ < 0.80), above 68.4% of all effects, PSES = .684. Regarding incremental harm, male victims of child sexual abuse reported 32.2% (r = .322) greater severity in PTSD symptoms than non-victims. Nevertheless, for both female and male groups, the data from the primary studies exhibited significant heterogeneity. Artifactual components of variance in the observed effect sizes accounted for 2.78% of the total variance for the female-specific data and 6.59% for the male-specific data (under the 75% rule), suggesting that moderators influenced the observed true mean effects. A comparison of the effect sizes for females (δ = 0.99) and males (δ = 0.68) showed that psychological harm was significantly higher in females, q(N’ = 11247) = 0.143, Z = 10.72, p < .001. These gender differences were also reflected in prevalence rates (derived as weighted prevalences from subsets of studies), with a PTSD diagnosis of 39.81% in female victims (k = 24, N = 3,547), compared to 24.23% among male victims (k = 12, N = 1,118). Study of the Effect of the Victim-perpetrator Relationship Moderator Victims in primary studies were classified as having been abused by intrafamilial or extrafamilial perpetrators. The results of the meta-analysis of psychological harm experiences by victims of intrafamilial sexual abuse (see Table 4) showed a significant, Z = 8.23, p < .001, positive (CSA victims of intrafamilial perpetrators scored higher in PTSD than CSA non-victims), and more than large magnitude (δ > 1.20) mean true effect size (δ = 1.68; above 88.3% of all effects, PSES = .883). This effect was generalizable (lower bound of the credibility interval = 1.21). but heterogeneous, % Var = 24.40, suggesting that the overall effect is mediated by moderators. Table 4 Meta-analyses of CSA Victimization and Forensic Psychological Harm (PTSD) for the Perpetrator Relationship Moderator   Note. k = number of effect sizes; NT = total sample size; NE = CSA group sample size d = sample size weighted mean effect size; SDd = standard deviation of d; SDpre = standard deviation predicted for sampling error alone; SDres = standard deviation of d after removing sampling error variance; δ = mean true effect size; SDδ = the standard deviation of δ; % var = percent of observed variance accounted by artifactual errors; 80% CIδ = 80% credibility interval for δ. For victims of extrafamilial sexual abuse, the results (see Table 4) displayed a significant, Z = 7.65, p < .001, positive (CSA victims of extrafamilial perpetrators scored higher in PTSD than CSA non-victims), and of a more than large magnitude (δ > 1.20) mean true effect size (δ = 1.24; above 81.1% of all effects, PSES = .811). Moreover, these results were generalizable (the minimum expected effect, lower bound = 0.46), but influenced by moderators (% Var = 7.38). Comparatively, psychological harm resulting from intrafamilial abuse was significantly greater, q(N’ = 1281) = 0.177, Z = 4.47, p < .001, with victims abused by intrafamilial perpetrators experiencing 64.3% (r = .643) more psychological harm (incremental harm due to victimization) than non-victims, whereas victims of extrafamilial abuse reported 52.7% (r = .527) more psychological harm than non-victims. Effect of the Type of Abuse Information regarding the type of sexual abuse described in the primary studies was coded into three categories: no-contact abuse (sexual exposure without direct contact, like public masturbation or unwanted sexual propositions); touching (episodes involving physical contact such as sexual fondling or genital touching); and penetration (any form of sexual abuse involving vaginal, oral, or anal intercourse). For the no-contact abuse moderator (see Table 5), the primary studies (k = 3) exhibited a non-random distribution, with a total sample size of 857, distributed in individual study samples of 3, 17, and 837 participants (the largest study comprising 97.7% of the total). Therefore, although the observed mean true effect size (δ = 0.76) was positive and significant, Z = 6.18, p < .001, it is not considered generalizable to other studies, requiring more research to ascertain the generalizable effect of no-contact abuse on PTSD outcomes. Table 5 Meta-analyses of CSA Victimization and Forensic Psychological Harm (PTSD) for Type of Abuse Moderator   Note. k = number of effect sizes; NT = total sample size; NE = CSA group sample size d = sample size weighted mean effect size; SDd = standard deviation of d; SDpre = standard deviation predicted for sampling error alone; SDres = standard deviation of d after removing sampling error variance; δ = mean true effect size; SDδ = the standard deviation of δ; % var = percent of observed variance accounted by artifactual errors; 80% CIδ = 80% credibility interval for δ. In turn, the meta-analytic results for the touching abuse moderator (see Table 5) showed a significant, positive (higher scores in PTSD in touching abuse victims than in non-victims), Z = 6.59, p < .001, generalizable across studies (the lower bond of the credibility interval was 0.03) and of large magnitude (δ > 0.80). Nevertheless, the effect sizes from the primary studies were heterogeneous (% Var = 4.12%), suggesting the influence of moderators. Meanwhile, for abuse involving penetration (see Table 5), the results illustrated a significant, Z = 7.46, p < .001, positive (higher scores in PTSD in penetration abuse victims than in non-victims), and more than large magnitude (δ > 1.20) mean true effect size (δ = 1.23, above 80.8% of all effects, PSES = .808). It was also generalizable across studies (the minimum expected effect, lower bound was 0.41). However, the distribution of the effects also showed evidence for moderators (% Var = 6.69%) i.e., the effects for different studies might be quite different. The comparison of effect sizes indicates that psychological harm (PTSD) derived from penetrative abuse was significantly higher in victims of abuse involving penetration (δ = 1.23) than in those who endured non-penetrative sexual touching (δ = 1.01), q(N’ = 1480) = 0.032, Z = 4.58, p < .001. Quantitatively and in terms of the incremental harm due to victimization, victims of touching abuse reportedly suffered 45.1% more psychological harm (r = .451) than non-victims, and victims of penetration experienced 54.4% (r = .544) psychological harm in relation to non-victims. Overall, the results demonstrated a robust (a large magnitude overall effect size) and positive relationship between CSA victims and PTSD outcomes. However, heterogeneity in the distribution of the studies was observed in the overall analysis suggesting that effects for different studies might be quite different (moderators of the effect). In any case, this pattern of results, positive relationship between CSA victimization and psychological harm (PTSD), was observed for the four moderators of the relationship between forensic psychological harm (PTSD) and CSA victimization identified in primary studies: the victim’s gender (males and females), the type of abuse (no-contact, touching and penetration), the victim-perpetrator relationship, and the type of PTSD measure (diagnosis and symptom severity). Thus, the meta-analyses’ results showed a significantly larger effect size for the PTSD-CSA relationship when psychological harm was measured in diagnoses compared to severity scales. Although this may seem counterintuitive, despite stricter diagnostic criteria, it may be due to the greater use of samples from clinical settings in diagnostic studies (Taubman-Ben-Ari et al., 2001), unlike population samples used for severity scores. In the context of forensic evaluation, symptom scores are not optimal indicators for determining psychological injury, as they do not require fulfillment of all diagnostic criteria and do not assess the causation of harm (Arce, 2018; Goodman-Delahunty & Foote, 2009; Melton et al., 2017). Therefore, in forensic settings, a multi-method approach is essential, combining diagnostic interviews (symptom knowledge task) with psychometric instruments (symptom recognition task) (Arce, 2018; Vale et al., 2024; Young et al., 2025), ensuring greater sensitivity and specificity, while meeting stringent forensic standards (Arce et al., 2009; Pereda & Arch, 2012). Regarding victim gender, both females and males face a significant risk of developing psychological harm following CSA. Although consistent with prior research (Mitra et al., 2021; Olff, 2017; Walker et al., 2004), the impact is significantly greater among females, being the estimated PTSD diagnosis prevalence of 39.81% for females compared to 24.23% for males. This association might be explained by an interaction of biological factors (e.g., neurochemical and hormonal influences and genetic predisposition) (Christiansen & Berke, 2020; Garza & Jovanovic, 2017), stronger psychological trauma responses in women (e.g., more intrusive symptoms, hyperarousal, distress and self-blame) (Nomamiukor et al., 2024; Olff, 2017), and sociocultural influences (Ullman & Filipas, 2005), along with the evidence that abuse among women often appears to be more severe (Putnam, 2003; Soylu et al., 2016). However, research has led to an underrepresentation of male CSA survivors, potentially overstating its impact on females (Urquiza & Keating, 1990; Walker et al., 2004). Finally, meta-analyses identified specific abuse characteristics that amplify psychological harm following CSA. With respect to the victim–offender relationship, both categories studied, intrafamilial and extrafamilial, involve a more than large effect in psychological harm (δ = 1.68 and 1.24 for intra- and extra-familial, respectively). Comparatively, intrafamilial abuse entails a significantly greater risk of psychological harm than extrafamilial. This may be attributable to the profound betrayal of trust by a caregiver within a dependent power dynamic (Filipas & Ullman, 2006) and to the nature of the abuse itself, since intrafamilial victimization typically has an earlier onset, longer duration, and involves more severe forms of abuse (Ferragut et al., 2021; Kiser et al., 2014). Additionally, intrafamilial abuse has an indirect effect on family disestablishment, which is strongly related to psychological distress. Similarly, abuse involving greater physical contact was associated with increased psychological harm (Downing et al., 2021). Specifically, abuse involving penetration was associated with an incremental harm of approximately 54%, compared with 45% for non-penetrative (touching), suggesting that different typologies should warrant distinct legal classifications of severity (Amado et al., 2015). As for the estimation of compensation to victims (UN, 1985), the results quantified the incremental harm (loss attributable to CSA victimization) at 42.2%, proposing this value as a general gold standard. This compensation should be paid by the perpetrator (or the states when compensation is not available; UN, 1985). Specific higher gold standards may be considered for intrafamilial abuse, 64.3%, and for victims of penetration, 54.4%. In summary, this research confirmed a large effect between CSA and PTSD, with significantly greater forensic psychological harm (PTSD) observed in female victims (in comparison to males), victims of intrafamilial abuse (in comparison to extrafamilial abuse), and in cases of penetrative abuse (in comparison to non-penetrative abuse). These findings advocate that the criminal responsibility of offenders should not be solely punitive but should also include civil economic compensation for psychological injuries and moral harm caused to victims (Aoláin et al., 2015; Barret et al., 2014; Cea et al., 2022; UN, 1985). To ensure a just and effective reparation, compensation must be commensurate with the magnitude of the harm suffered (UN, 1989). This implies that legal responses must consider factors that exacerbate the severity of abuse, such as an intrafamilial relationship or acts involving penetration (Coburn et al., 2017; Pozzulo et al., 2010), when determining punitive measures and economic compensation (Greene et al., 1999; Vallano, 2013). As for the burden of proof, psychological harm (PTSD), when a causal link between the reported psychological harm and the investigated event of CSA may be established (Arce, 2018), may constitute the keystone of the burden of proof in around 40% of cases. Furthermore, this implies that the absence of psychological harm does not mean that CSA did not exist (however, as for civil implications, the absence of psychological harm may imply no compensation to the victim), nor does it exclude the possibility that psychological harm may manifest in the future (Utzon-Frank et al., 2014). For the remaining cases (± 60%), the evaluation of the witness statement will be the keystone of the burden of proof (Arce, 2017). In this context, it is essential to systematically conduct forensic evaluations to assess psychological harm in CSA cases (Arce, 2017; Kane & Dvoskin, 2011; Montes et al., 2022; Seymour et al., 2013), reinforcing the victim’s testimony and providing it with objective evidence (Carrasco-Azogue et al., 2024). Indeed, research has demonstrated that the assessment of psychological injury affects jurors’ and judges’ judgment making, leading to higher rates of guilty verdicts, higher damage awards, and more severe sentences (Diamond & Salerno, 2013; Novo & Seijo, 2010; Vallano et al., 2013; Vredeveldt et al., 2024). Furthermore, when evaluating young children (i.e., under 12 years), assessment methodologies must be adapted to their cognitive capabilities (Arce & Fariña, 2012; Bull, 1995; Melton et al., 2017) to avoid distorting the results or causing undue distress. Limitations of the Study Despite its findings, this meta-analysis has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the ascertainment of CSA exposure in some primary studies was based on self-report measures, which lack reliability indicators and do not entirely control for the risk of false positives. Second, several methodological issues in PTSD assessment warrant caution. Concerning the evaluation context, many primary studies were conducted in clinical rather than forensic settings, which may involve less stringent criteria (i.e., the causal link between CSA and PTSD was not always rigorously established, nor was malingering systematically ruled out). Further limitations relate to the types of PTSD measures used: some were based on psychiatric diagnoses for which reliability indicators were absent, while other studies employed psychometric instruments measuring symptom severity, which is often insufficient to assess psychological injury in legal contexts. Third, a methodological issue in some studies was the lack of a control group. Consequently, normative population data were sometimes used as a contrast, which could lead to potential distortions in the calculated effect sizes (Briere, 1992). Fourth, although the results of the meta-analysis were highly generalizable (Ns > 400 and a large k; Schmidt & Hunter, 2015), they exhibited variability, implying the potential influence of moderating factors that could not be comprehensively examined. The main reason for this was that primary studies often did not report differential effects related to specific characteristics of CSA potentially involved in PTSD outcomes (i.e., age of onset, duration of abuse, relationship with the perpetrator, types of abuse, polyvictimization); or because the number of these studies was insufficient for certain potential moderator analyses (k ≤ 3). Future research should therefore aim to identify additional moderators with impact in the probability of psychological harm in CSA cases. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Cea, B., Montes, A., Trinidad, A., & Arce, R. (2025). Forensic psychological harm in victims of child sexual abuse: A meta-analytic review. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 7(2), 111-129. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a10 REFERENCES References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the metaanalysis. Appendix Summary Table of Primary Studies Characteristics   Note. ryy = reliability of PTSD measure instruments rxx = reliability of child sexual abuse measure instruments; NGE = experimental group sample size; NGC = control group sample size; d = standardized mean difference effect size; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval for d. (1) Control group (NGC) extracted from a separate normativepopulation study using the same PTSD measure; (2)Outlier value Key to Acronym: DICA-R = Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents Revised; CITES II = Children’s Impact of Traumatic Events Scale II; IES = Impact of Event Scale; TSI = Trauma Symptom Inventory; CPSS = Child PTSD Symptom Scale; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition; CES-D = Studies Depression Scale; CIDI = Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CITES-R = Children’s Impact of Traumatic Events Scale Revised; SCL-90-R = Symptom Checklist 90 Revised; SCID = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; DICA = Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents; PSS = Severity of Symptoms of PTSD Scale; TSQ = Trauma Screen Questionnaire; DSM-IV-TR = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; PTSD-RI = UCLA Adolescent PTSD Reaction Index; UDADIS-5 = Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule; PSS-SR = Child PTSD Symptom Scale Self-Reported; TSCC = Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children; DIS-III-R = Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version III-R; DSM-III-R = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised; K-SADS-PL = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Present/Lifetime Version; PDS = Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale; PTCI = Post-traumatic Cognitions Inventory; HTQ = Harvard Trauma Questionnaire; NWS = National Women’s Study; PCL = PTSD Checklist; DIS-IV = Diagnostic Interview Schedule Version IV; K-SADS-E = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Epidemiologic Version; PCL-C = PTSD Checklist Civilian Version; IES-R = Impact of Event Scale Revised; PPTSD-R = Purdue PTSD Scale Revised; CPTSD-RI = UCLA Child PTSD Reaction Index; PTSD-Q = PTSD Questionnaire; CIDIS-IV = Diagnostic Interview Schedule Computerized version; CAPS = Clinician Administered PTSD Scale; ICD-11 = International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision; PSSI = PTSD Symptom Scale Interview; DICA-6-R = Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents Version 6R; ICD-10 = International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision; ChiPS = Children’s Interview for Psychiatric Syndromes; K-SADS-PL-G = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Present/Lifetime German Version; K-SADS-PL-T = Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Present/Lifetime Turkish Version; GHQ-28 = General Health Questionnaire; SIPTSD = Structures Interview for PTSD; PCL-S = PTSD Checklist -Specific form; PC-PTSD = Primary Care PTSD Screen; TSC-40 = Trauma Symptom Checklist 40, KIDSCID = Children’s Structured Clinical Interview; CRIES-13 = Children’s Revised Impact of Event Scale; TSCYC = Trauma Symptom Checklist for Young Children; SPRINT = Short Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Rating Interview; CITES = Children’s Impact of Traumatic Events Scale; HVF = History of Victimization Form; CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DAST = Detroit Area Survey of Trauma; WSHI = Wyatt Sexual History Interview; TES = Traumatic Events Survey; ACE = Adverse Childhood Experiences; SARS = Sexual Abuse Rating Scale; CTQ-SF = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire Short Form; LEC = Life Events Checklist; ICI = Incident Classification Interview; CSAI = Childhood Sexual Abuse Interview; SAQ = Sexual Abuse Questionnaire; CSEQ = College Student Experiences Questionnaire; ESE = Early Sexual Experiences; CEVQ = Childhood Experiences Violence Questionnaire; TLEQ = Traumatic Life Event Questionnaire; THQ = Trauma History Questionnaire; TEI = Traumatic Event Interview; ETI = Early Trauma Interview; THI = Trauma History Interview; NCS = National Comorbidity Survey; NSA = National Survey of Adolescents; JVQ = Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire; CTI = Comprehensive Trauma Interview; SAP = Sexual Abuse Profile; SAIS = Sexual Abuse Interview Schedule; SAEQ = Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire; TSS = Traumatic Stress Schedule; CCMS-A = Comprehensive Child Maltreatment Scales for Adults; TESI = Traumatic Events Screening Inventory; TAA-R = Trauma Assessment for Adults-Brief Revised Version; SES = Sexual Experiences Survey. |

Cite this article as: Cea, B., Montes, Á., Trinidad, A., & Arce, R. (2025). Forensic Psychological Harm in Victims of Child Sexual Abuse: A Meta-analytic Review. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 111 - 129. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a10

Correspondence: ramon.arce@usc.es (R. Arce).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS