Examining Internal and External Consent in Consensual and Non-Consensual Contexts in Women

[InvestigaciĂłn del consentimiento sexual interno y externo de las mujeres en contextos consentidos y no consentidos]

Nieves Moyano1, Antonio Rafael Hidalgo-Muñoz2, María del Mar Sánchez-Fuentes3, Kristen Jozkowski4, and Reina Granados5

1Departament of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Education Sciences, University of Jaén, Spain; 2Department of Basic Psychology, Psychobiology, and Behavioral Sciences Methodology, University of Salamanca, Spain; 3Mind, Brain, and Behavior Research Center, University of Granada, Spain; 4Department of Applied Health Science, School of Public Health, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA; 5Nursing Department, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Granada, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a5

Received 6 August 2024, Accepted 16 December 2024

Abstract

Background/aim: The Internal and External Consent Scales (ICS and ECS) have been used to measure these constructs, primarily among college students or young adults in the United States during consensual sexual activity. The aim of this work is to examine women’s internal and external consent to both consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences. Method: Building on this research, we applied these measures to both consensual and nonconsensual contexts in a sample of 764 adult women from Spain. Then, among women who experienced nonconsensual sex (n = 252), we further analyzed situational factors associated with the encounter: setting (i.e., whether the participant was in a known vs. unknown location when the nonconsensual sex occurred), and whether the nonconsensual sex was sexual coercion or sexual assault. Results: Our results show that, with regard to external consent, when engaging in consensual sex, women indicated greater use of all cues ranging from communication/initiation behavior to nonverbal behaviors than those who experienced nonconsensual sex. Similarly, those who experienced nonconsensual reported lower physiological responses of arousal, less safety/comfort, consent/wantedness, and readiness compared with those who had consensual sex. Further, those who experienced nonconsensual sex in an unknown setting (vs. known) reported feeling less safety and readiness in term of internal consent. Finally, women who experienced sexual coercion (vs. sexual assault) indicated greater use of borderline pressure. Conclusion: Our study expands on previous conceptualization of the ICS and ECS to include both consensual and nonconsensual encounters, which provides further insight about the continuum of sexual consent.

Resumen

Antecedentes/objetivo: Las Escalas de Consentimiento Interno y Externo (ICS y ECS) han sido empleadas para medir estos constructos, principalmente entre estudiantes universitarios o adultos jóvenes en los Estados Unidos en contextos sexuales de consentimiento. El objetivo de este trabajo consistió en examinar el consentimiento interno y externo de las mujeres en contextos de consentimiento y no consentimiento sexual. Método: Se aplicaron las escalas de ICS y ECS tanto en contextos consentidos como no consentidos en una muestra de 764 mujeres adultas de España. Entre las mujeres que experimentaron relaciones sexuales no consentidas (n = 252), se analizaron los factores situacionales asociados con el encuentro: el entorno (es decir, si la participante se encontraba en un lugar conocido frente a uno desconocido cuando se produjo la relación no consentida), y el tipo de relación no consentida (coacción sexual o agresión sexual). Resultados: Nuestros resultados muestran que, en lo que respecta al consentimiento externo, al participar en relaciones sexuales consentidas, las mujeres indicaron un mayor uso de todas las señales que van desde comunicación/comportamiento de inicio hasta conductas no verbales, en comparación con quienes experimentaron sexo no consentido. De manera similar, aquellos que experimentaron un comportamiento no consentido informaron de menor excitación, menos seguridad/comodidad, consentimiento/deseo, y disposición en comparación con aquellas que tuvieron relaciones sexuales consentidas. Además, las mujeres que experimentaron relaciones sexuales no consentidas en un entorno desconocido (vs. conocido) informaron sentirse menos seguras y con menor disposición en términos de consentimiento interno. Por último, las mujeres que sufrieron coerción sexual (vs. agresión sexual) indicaron un mayor uso de la presión límite. Conclusión: Nuestro estudio amplía la conceptualización previa del ICS y el ECS para su análisis tanto en contextos consentidos como no consentidos, lo que proporciona más información sobre la continuidad del consentimiento sexual.

Keywords

Sexual consent, Internal consent, External consent, Nonconsensual, Sexual coercionPalabras clave

Consentimiento sexual, Consentimiento interno, Consentimiento externo, No consentido, CoacciĂłn sexualCite this article as: Moyano, N., Hidalgo-Muñoz, A. R., Sánchez-Fuentes, M. D. M., Jozkowski, K., & Granados, R. (2025). Examining Internal and External Consent in Consensual and Non-Consensual Contexts in Women. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(1), 49 - 57. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a5

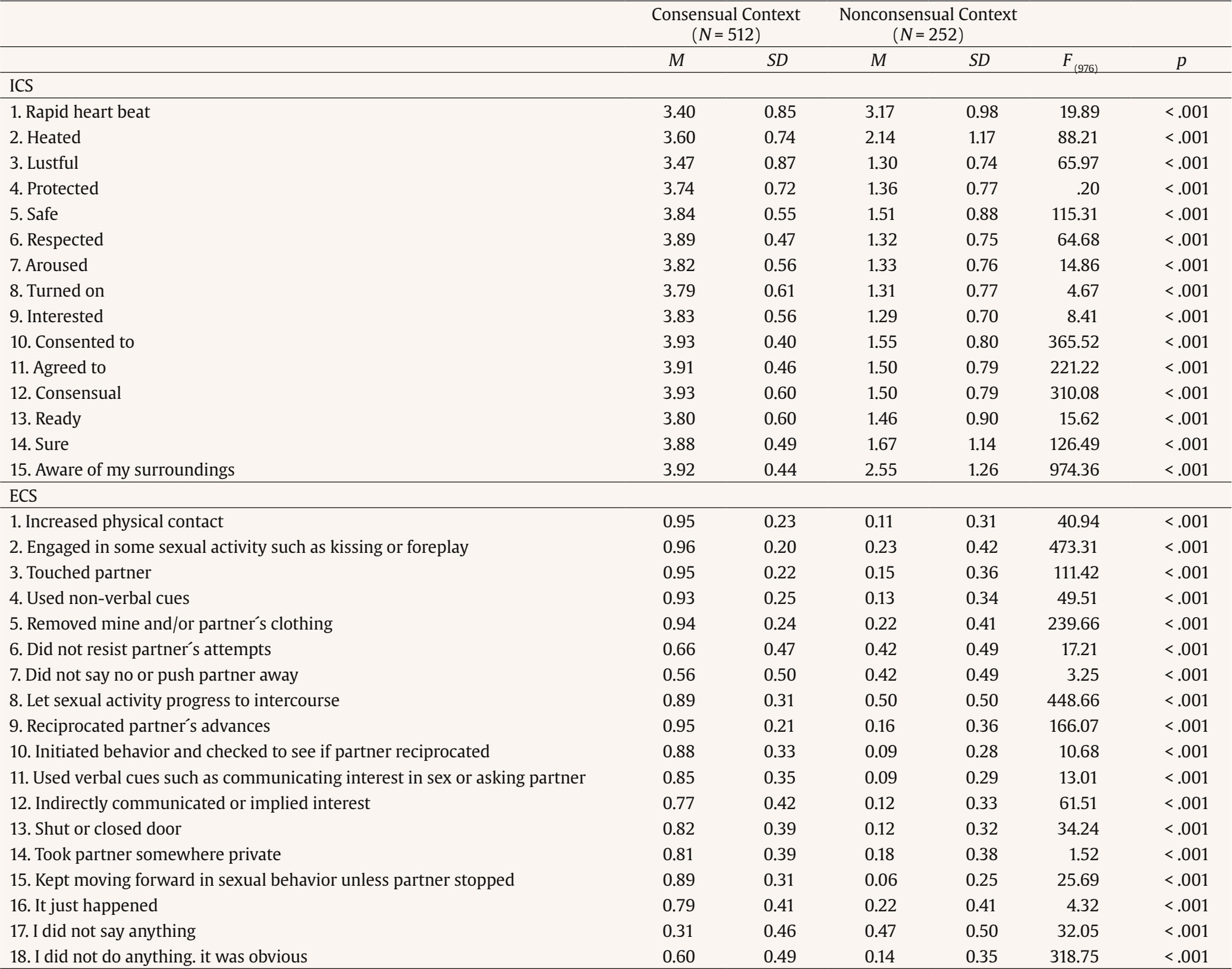

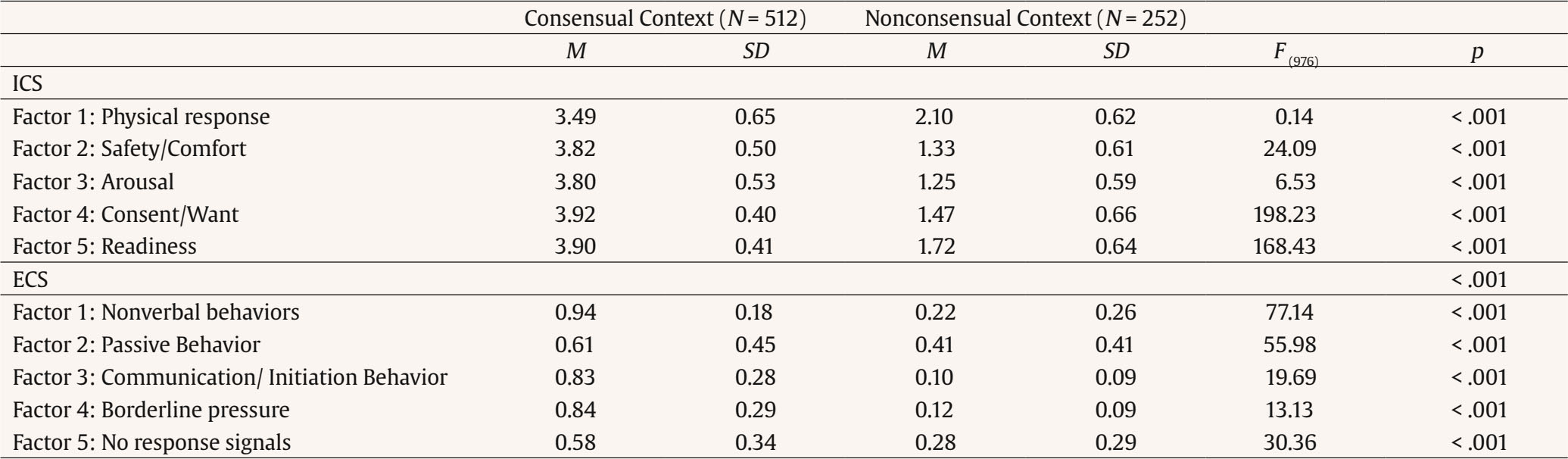

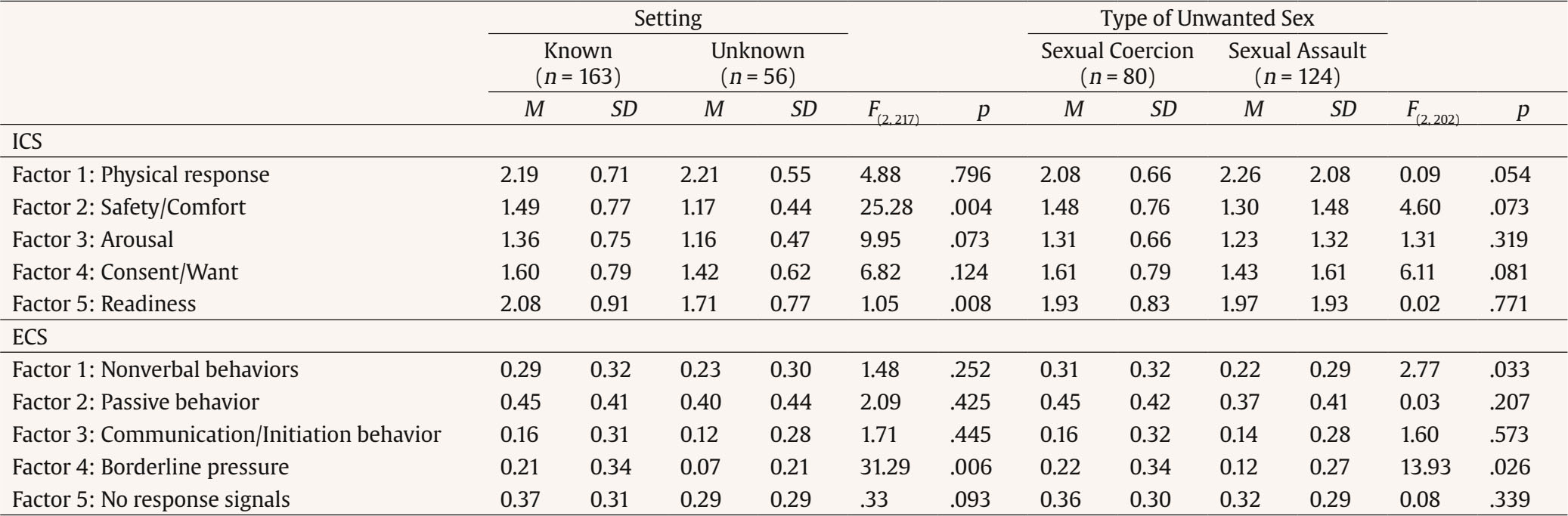

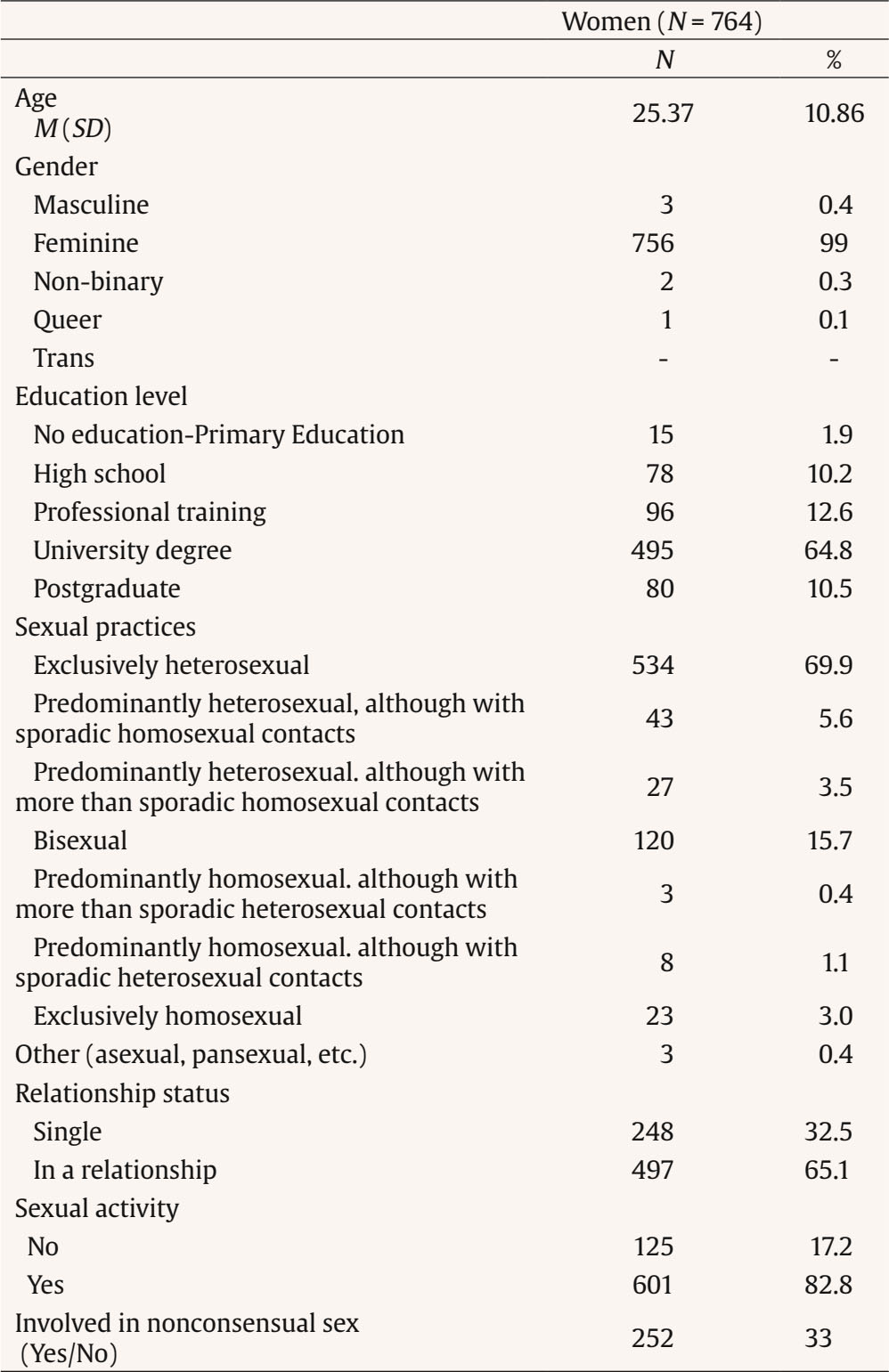

Corresponding author: Nieves Moyano (mnmoyano@ujaen.es).Recent research emphasizes two related aspects of sexual consent—the internal feelings people experience leading to consensual sex (i.e., internal consent) and the external cues people use to communicate their consent to a sexual partner (i.e., external consent; Jozkowski et al., 2014b; Walsh et al., 2019; Willis et al., 2019, 2021). Internal consent comprises multiple “feelings” including willingness as well as feelings of safety/comfort, readiness, and agreement, demonstrating its multi-faceted nature (Jozkowski, 2019; Jozkowski et al., 2014b). These feelings exist on a continuum such that men and women may experience them to varying degrees within and across different sexual experiences (Willis et al., 2021). Thus, internal consent is not an “on and off” switch, but rather a continuum. Alternatively, external consent comprises the ways in which individuals “communicate” their willingness to engage in sexual behavior including a range of cues both explicit and implicit as well as verbal and nonverbal, which people say or do to express their willingness or agreement to engage in sexual behavior (Jozkowski et el., 2014b). Like internal consent, external consent also varies across context (Willis et al., 2021). Importantly, there is a distinction between “wantedness” and consent (Jozkowski & Peterson, 2013; Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2007). Indeed, some individuals experience sexual encounters that may be wanted, but not consented to and vice versa—experiences they do not want, but consent to (Peterson & Muehlenhard, 2007). Such sexual encounters can vary in the degree that they are distressing (Hills et al., 2020). Research examining both internal and external consent to date has largely, if not exclusively, examined these constructs in the context of consensual sexual activity. Yet, individuals may experience internal feelings and use external cues during both consensual and nonconsensual sex, however the latter has been relatively unexplored. Therefore, we examined women’s internal and external consent to both consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences to further examine the extent that internal and external consent may vary across setting and type of nonconsensual sexual behavior (i.e., coercion vs. assault). Internal and External Dimensions of Consent Internal consent refers to the internal feelings associated with willingness to engage in sexual activity, while external consent refers to a range of verbal or non-verbal, direct or indirect, cues people report using to signify consent to sexual activity (Jozkowski, 2019; Jozkowski et al., 2014b; Muehlenhard et al., 2016; Willis et al., 2019). The Internal Consent Scale (ICS) and the External Consent Scale (ECS) were developed and have been used to measure both of these related, but distinct aspects of consent (Jozkowski, 2019; Jozkowski et al., 2014b; Walsh et al., 2019; Willis et al., 2019, 2021a, 2021b). Both scales were initially developed to examine internal and external consent to engage in consensual vaginal-penile intercourse (Jozkowski, 2019; Jozkowski et al., 2014) and then further used to examine other sexual behaviors beyond vaginal-penile intercourse (Walsh et al., 2019; Willis et al., 2021). Notably though, in all these administrations of the measures, participants were asked to consider consensual sexual behavior, which makes sense because the original intent of the measures was to capture the feelings experienced and cues used to communicate sexual consent. However, sexual consent is a complex construct (Muehlenhard et al., 2016). Men and women experience a range of feelings during both consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences. Research examining people’s internal consent feelings and use of external consent cues in the context of unwanted or nonconsensual sex is lacking. Sexual Consent vs. Non-consent The ways non-consent is experienced and expressed may significantly differ from the ways consent is experienced and expressed. Walsh et al. (2022) suggest that voluntary sexual encounters involve the use of more explicit signs of external consent than involuntary (or nonconsensual) sexual experiences. When college students were asked to define nonconsensual sex, they indicated feelings of unwantedness, unwillingness, and discomfort (Marcantonio & Jozkowski, 2023), whereas they typically associate consensual sex with feelings of wantedness, willingness, and comfort (Jozkowski et al., 2014a; 2014b). However, college students report using both verbal and nonverbal cues to communicate consent and non-consented to sexual behavior (Jozkowski et al., 2014a; Marcantonio & Jozkowski, 2023). Indeed, despite acknowledging that explicit and ideally verbal cues are best practice for communicating consent and refusal/non-consent (Beres et al., 2004), young adults commonly report more frequently using non-verbal cues to communicate both consent and refusal/non-consent (Jozkowski et al., 2014a; Marcantonio & Jozkowski, 2020). Unfortunately, many women do not feel as though they do not want to disappoint, unset, or anger their male sexual partner (Jozkowski et al., 2017), because they feel as though refusing is useless/they will not be listened to, or may freeze up during the encounter (Bucher & Manasse, 2011). Therefore, the ways in which women refuse unwanted sex range (Clay-Warner, 2002; Ullman, 2007). For this reason, there are recent studies that have focused on analyzing which behavioral indicators are considered signs of sexual consent/non consent. As such, the study of both internal feelings and external cues associated with both consensual and nonconsensual sex is warranted. Such information may provide insightful information to guide sexual violence prevention. Sexual Consent and Context: Setting and Type of Nonconsensual Sex Sexual consent is contextual (e.g., Anyadike-Danes et al., 2024; Willis et al., 2021). For instance, individuals report the physical context or location of interactions as being relevant to perceptions of consent (Jozkowski et al., 2018; Jozkowski & Willis, 2020). Additionally, in the context of sexual violence, individuals who experienced sexual assault may feel less safe based on their physical location during the nonconsensual sex (Culbertson et al., 2001). In this sense, the setting where sexual intercourse occurs can influence how people experience sex and consent. Research about behavioral manifestations facing nonconsensual sex in different locations is scarce, besides some research on gender differences in place safety perceptions (e.g., Basu et al., 2021), or on the severity of sexual assaults (e.g., Young et al., 2009). Given the variability in location that sexual behavior can occur, we focused on individual´s familiarity with a “setting” (i.e., known setting vs. unknown setting) (Felder, 2021). In this sense, place is not simply a physical location, but also the constructions and social-relational experiences that make up the reality of each person (Wilson & Donna, 2008). According to Kaufman (2024), among college women, safety behavior is based on bullying, perceived delinquency, and secondary trauma. All of this, entails carrying out a spatial behavior around avoiding “dangerous” or feared places, regardless of whether they have suffered violence in them. In general, although no place seems to be totally safe (Hutson & Krueger, 2019), a known place is associated with the perception of control and safety compared with an unknown location (Macmillan et al., 2000; Vuanello, 2009). This is paradoxical since most sexual violence against women occurs in the private sphere by perpetrators known to them (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021, 2022; Koskela & Pain, 2000). In this way, a familiar place can become an aversive and unsafe context if, for example, it is the place where sexual assault has occurred or continues to occur. As indicated by Cook and Messman-Moore (2018), it is important to examine non-consent within the context of different types of sexual victimization to increase our understanding of women’s experiences. Therefore, among women who experienced nonconsensual sex, it is of great relevance to distinguish two likely situations that may occur: (1) “sexual coercion”, for situations in which one partner explicitly “pressures the other for sex” (Katz & Tirone, 2009), a common form of sexual violence (Pugh & Becker, 2018). Generally speaking, this behavior reflects situations in which one person does not want to engage in sexual behavior, but ultimately stops refusing or may feel as though refusing is useless due to the use of tactics to elicit sexual activity from unwilling partners (Pugh & Becker, 2018), and (2) “sexual assault”, referring to situations in which the participant was made to have sex when they did not consent. The Present Study Our study comparing internal and external consent across consensual and nonconsensual contexts provides relevant information to better understand both consensual experiences, as well as sexual assault and violence for both future research and for the practical context of criminal law (Arrigo & Shipley, 2005; Shipley & Arrigo, 2012). Exploring the association between these aspects is important considering that some internal feelings such as awareness of one’s environment and external behaviors such as the non-resistance of the victim, not saying no, or the passivity of the victim are debated (Faraldo & Acale, 2018; Randall, 2010) and sometime used to challenge the credibility of victims’ experiences of sexual violence. Most studies using the ICS and ECS have explored consensual sex experiences. To the extent of our knowledge, a recent study used both scales in sexual victims. Their findings indicate lower levels of internal consent and greater use of passive behavior (Walsh et al., 2024). However, more research should examine these constructs in a nonconsensual context to better understand sexual violence in which other situational factors may play a key role and to determine whether some external cues could be similar in both contexts. To address these gaps, the present study had two main goals for which the following hypotheses were tested: (1) Examine ICS and ECS for both consensual and nonconsensual sex. H1: We hypothesize that women experiencing consensual sexual activity will report higher scores on all internal consent sub-scales (physical response, safety/comfort, arousal, agreement/wantedness, and readiness), than those who experienced nonconsensual sexual behavior. And we hypothesize that women who report on consensual sexual experiences will report using explicit cues to communicate consent (i.e., communication/initiator behaviors) compared with those who experience nonconsensual sex. (2) Among those who experienced nonconsensual sex, we further analyzed some specific situational factors related to the “setting” (“known” vs. “unknown”) and type of sexual violence (“sexual coercion” vs. “sexual assault”) in women. H2.1: We hypothesize that women experiencing nonconsensual sexual activity in a known setting will report higher scores on all internal consent sub-scales (physical response, safety/comfort, arousal, agreement/wantedness, and readiness) than those who experienced nonconsensual sexual behavior in an unknown setting. We hypothesize that women who report on nonconsensual sexual experiences in a known setting will report greater use of external consent cues-nonverbal behaviors, passive behavior, borderline pressure, and no response signals than those in an unknown setting. H2.2: We hypothesize that women experiencing nonconsensual sexual activity in the sexual assault situation will report lower scores on all internal consent sub-scales (physical response, safety/comfort, arousal, agreement/wantedness, and readiness), and also will report lower external consent cues –nonverbal behaviors, passive behavior, borderline pressure, no response signals– than those who experienced nonconsensual sexual behavior in a sexual coercion situation. Participants A cross-sectional study was conducted. Inclusion criteria were: a) being Spanish, b) being at least 18 years old, c) women, d) actual partner or past male couple, and e) had maintained consensual sexual relations. Data from 764 women were analyzed. Most of the sample held a university degree (75.3%) and self-labeled as exclusively heterosexual (69.9%). In total, 33% of women indicated at least one experience of nonconsensual sex along their lifetime (n = 252). Table 1 shows sociodemographic characteristics for the sample. Instruments Sociodemographic information was collected from participants (see Table 1) and we assessed the following constructs: Consensual and Nonconsensual Sex Participants were provided the following definition of sexual consent based on Willis and Jozkowski (2019): “one’s voluntary and conscious willingness to engage in a particular sexual behavior with a particular person within a particular context”. Based on this definition, participants were asked whether they had experienced a nonconsensual encounter: “If the statement described above was not met at any of your sexual encounters, please indicate “Yes”. Dichotomous options were provided “Yes/No”. Participants who reported nonconsensual sex were asked whether the nonconsensual experience occurred in a setting Known vs. Unknown by you. These participants were also asked via an open-ended question: “Please, indicate the reasons why you consider sex was not consented and how it occurred”. Two independent researchers reviewed the responses and classified them into the following two main categories: (1) sexual coercion (initial sexual activity was unwanted and due to partner’s pressure, finally the respondent acquiesced to sex) and (2) sexual assault (sexual activity was unwanted from the beginning until the end of sexual activity, or explicit physical violence was used). Other reasons such as “I was just blocked”, “intoxicated/drugged” and other ambiguous responses were also reported but in a lower percentage (less than 5% as a theme), therefore no further analysis of those responses was conducted. Internal Consent Scale-Short form (ICS-short form) (Jozkowski et al., 2014b; Willis et al., 2022) was translated into Spanish and was used to assess internal consent or the internal feelings related to willingness to engage in sexual activity. Of note, according to the Spanish validation, the Spanish version of the measure comprised the same items distributed across the same structure as the original (Moyano et al., 2023). The ICS-short form comprises five factors, with 3 items for each factor: Factor 1: Physical response, Factor 2: Safety/Comfort, Factor 3: Arousal, Factor 4: Agreement/Want, and Factor 5: Readiness. Items are answered in a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). The original version asked participants to report whether they had experienced those aspects in their most recent partnered sexual activity. Higher scores indicate stronger internal consent. The five factors of the ICS have demonstrated an excellent internal consistency of the scale in past research, as well as for the factors (.95, .94, .93, .93, and .95; Jozkowski et al., 2014b), and McDonalds Omega (.84, .91, .88, .90, and .79, for factor 1 to factor 5, respectively; Willis et al., 2022). In the latter, invariance across gender has also been supported. The scale has shown significant correlations with the ECS factors, gender differences, and across relationship status (single vs. in a relationship). Cronbach’s alpha values for the present study were .73, .84, .92, .96, and .87 for factors 1 to 5, respectively. Regarding External Consent Scale (ECS) (Jozkowski et al., 2014b), the Spanish validation was used, that has a similar structure to the original one, except for items 8 (“Let sexual activity progress to intercourse”) and 9 (“Reciprocated partner´s advances”) that belonged to Factor 1: Nonverbal behaviors, instead of Factor 2: Passive Behavior (Moyano et al., 2023). The authors provide an 18-item version with a five- factor structure to assess: Factor 1: Nonverbal behaviors, Factor 2: Passive behavior, Factor 3: Communication/Initiator Behavior, Factor 4: Borderline pressure and Factor 5: No response signals. The ECS used dichotomized response choices as either “Yes” or “No”, that were coded as 1 and 0, respectively. The original version asked participants to report whether they had experienced those aspects in their most recent partnered sexual activity. In case of more than one nonconsensual sex, they should refer to the one they recall the best. The five factors of the ICS have demonstrated strong internal reliability in past research based on Cronbach’s alpha values: .78, .81, .79, .78, and .67 for each of the five factors respectively, and .95 for the ICS overall factor in a sample of men and women (Jozkowski et al., 2014b). Cronbach’s alpha values for the present study were .90, .87, .73, .74, and .66 for factors 1 to 5, respectively. Importantly, for the purposes of the present study, participants were asked to report the extent that they had experienced those cues based on whether they had experienced consensual or nonconsensual sex. Therefore, the same instructions as those indicated by Jozkowski et al. (2014b) were followed for those who indicated to have been involved in consensual sex, for which their responses should refer to their most recent sexual activity. Alternatively, those indicating nonconsensual sex were asked to refer to their nonconsensual experience. In instances of more than one nonconsensual sexual experience, participants were instructed to refer to the encounter they recall the best. Procedure Participants were invited to participate in an online survey about sexual relationships and how sex is negotiated. The survey was distributed using virtual platforms (i.e., social networks and e-mail). When the participants clicked on the link, they were directed to the study information and informed consent, which provided information about the study purpose and its selection criteria. Then participants were asked if they wished to participate. They had to indicate “Yes” to go through all the questionnaires. Based on their responses, a different set of items were presented. Those who experienced a nonconsensual encounter were led to different instructions from the ICS and ECS, as indicated in the Measures section. None of the questions were mandatory, except for the informed consent agreement. Anonymity, data protection, and confidentiality were protected to the extent allowed by law and university policy. Some procedures were used to control online samples to prevent duplicate, fraudulent, or bot-generated responses, including tracking the IP address, a numerical CAPTCHA in the form of a randomized arithmetic calculation at the beginning of the questionnaire, as well as tracking URLs posted in suspicious locations. Table 2 Descriptive Statistics of the ICS and ECS Items by Consensual and Nonconsensual Context in Women.   Table 3 Descriptive Statistics of the ICS and ECS Subscales by Consensual and Nonconsensual Context in Women.   All participants were volunteers and did not receive any compensation for taking part in this research. The present study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the universities involved in the research for data recruitment (Jaén, Granada and Salamanca). Data Analyses First, we examined descriptive statistics of all items and subscales from ICS and ECS based on responses for consensual sex and nonconsensual sex for the total sample and by gender factor performing ANOVAs. Secondly, only within the nonconsensual situation, ICS and ECS subscales were compared in women by Setting (Known vs. Unknown) and Type of unwanted sex (Sexual coercion vs. Sexual assault). Descriptive Analyses The scores of the internal consent (ICS) ranged from 0 to 4 and for the external consent (ECS) for 0 to 1. As can be seen in Table 2, significant differences emerged for all internal consent (ICS) and external consent (ECS) items between consensual and nonconsensual sex contexts indicating higher scores for both the internal consent (ICS) and external consent (ECS) in the consensual context in comparison to the nonconsensual one. In a similar vein, significant differences emerged between the internal consent (ICS) and external consent (ECS) subscales between both contexts. As shown in Table 3, the consensual sex mean scores for all the internal consent (ICS) and external consent (ECS) subscales were very close to the upper limit, which reflects high levels of internal and external consent, respectively. The lowest mean score from the internal consent (ICS) was that for Factor 1: Physical response, while the highest mean scores was shown for Consent/Want. For the external consent (ECS), the highest score was reached by Factor 1: Nonverbal behaviors and the lowest for Factor 5: No response signals. Alternatively, when examining nonconsensual sexual experiences, for the total sample, mean scores of subscales from the internal consent (ICS) and external consent (ECS) were significantly lower, indicating lower levels of both internal and external contents. For the internal consent (ICS) subscales, the lowest mean was shown in Factor 3: Arousal and the highest for Factor 1: Physical response. Regarding external consent (ECS) scales, we observed some very low scores, especially in Factor 3: Communication/Initiation and Factor 4: Behavior and Borderline, being the highest score detected in Factor 2: Passive Behavior. ICS and ECS factors within nonconsensual context, by Setting and Type of unwanted sex Table 4 shows scores from the internal consent (ICS) and external consent (ECS) factors for nonconsensual sexual behavior only for women, based on “setting” (“known” vs. “unknown”) and type of “unwanted sex” (“sexual assault” vs. “sexual coercion”). Regarding “setting”, significant differences emerged in the internal consent (ICS) Factor 2, 4, and 5 (Safety/Comfort, Consent/Want, and Readiness, respectively), and in external consent (ECS) in Factor 1 and 4 (Nonverbal behaviors and Borderline pressure, respectively), indicating lower scores in the “unknown” setting compared with the “known” setting. Table 4 Descriptive Statistics of the ICS and ECS Factors in Nonconsensual Sex by Setting and Type of Unwanted Sex in Women.   Based on the type of unwanted sex, what they described was coded as “sexual assault” or “sexual coercion”. About 53.57% of women’s described experiences were coded as “sexual assault”, while 32.93% were coded as “sexual coercion”. The remaining 13.5% indicated “Other”. Significant differences were yielded in the internal consent (ICS) Factor 2 and 4 (Safety/Comfort and Consent/Want, respectively) and from the ECS in Factor 1 and 4 (Nonverbal behaviors and Borderline pressure, respectively), indicating lower scores in “sexual assault” sex in comparison to “sexual coercion”. The goal of the present study was to obtain greater insight about internal and external sexual consent across both consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences in women, which may help us to better understand consent as a construct and shed light on the ways consent is conceptualized during experiences of nonconsensual sex. In general, the hypotheses proposed in this study were supported, as we found higher levels of ICS and ECS scores during consensual compared with nonconsensual sexual experiences. Differences in Internal and External Consent across Consensual and Nonconsensual Encounters We found women reported experiencing stronger feelings of internal consent during consensual sexual experiences than nonconsensual experiences which adds support to the validity of these measures. Our findings indicate that during consensual sex, the core of internal feelings are those related to “consensual” and “consented”, which leads individuals to feelings of safety and comfort as previously found (Jozkowski et al., 2014b). In other words, we would expect women experiencing consensual sex to have stronger feelings across all five subscales as researchers argue that this measure reflects internal feelings of consent (Jozkowski, 2019; Jozkowski et al., 2014b). Interestingly, the smallest discrepancy between the consensual and nonconsensual experiences was for the physical response subscale. For instance, during nonconsensual sex, item 1 related to “heart beat” reached the highest score. Perhaps cardiac activity is a physiological indicator of arousal that could be applicable for both a desire/wanted/consensual situation, and also in a fearful or particularly undesired/not wanted/nonconsensual situation. Willis et al. (2022) noted issues with measurement invariance across gender for this item as well. Considering this, coupled with our findings, physiological measures of cardiac activity may not be as strong of a distinguishing factor between consensual and nonconsensual sexual activity. This is in line with previous studies in which, heart beat is not included as a “core” aspect of internal consent (Willis & Smith, 2022). Also related to the ICS within nonconsensual sex, it is worth mentioning that, contrary to what might be expected, a high score is obtained in item 15 (i.e., “Aware of my surroundings”). This may suggest that victims are aware of what is happening, potentially due to perceived danger (Messina Coimbra et al., 2023). Indeed, in these contexts it is possible that the victim is tapped into and aware of their environment (Forsyth et al., 2000; Fusé et al., 2007; Heidt et al., 2005), but perhaps unable to move, resist, or respond. Regarding the ECS, within a consensual sexual experience, passive behaviors such as “not resisting”, “doing nothing”, “not saying no” seem not to be considered as external expressions of consent, compared with nonverbal cues. In contrast, for nonconsensual sexual experiences, the highest scores of the ECS are obtained for the “No Response Signals” (i.e., not resisting, not saying no, not pushing the partner, and not doing anything). This is a key aspect for legal actions, as sexual violence should not be defined in terms of forced sex (by the aggressor) and the victim’s response or resistance to that action, instead, it should be defined as to whether that sexual relationship has been consented or non-consented (Muehlenhard & Peterson, 2004). Therefore, consent should not be conceptualized as a victim’s response or behavior, as this may lead to a justification of violence and rape culture, in which victim could be considered responsible and blamed for not confronting or opposing the conduct of the aggressor. Aligning with this, high scores in item 8 within a nonconsensual context (“Let sexual activity progress to intercourse”) also express a passive behavior in which some fear toward the aggressor or feeling block may play a role (Muehlenhard & Peterson, 2004; Rodríguez-Castro et al., 2020). Thus, these results also suggest that the definition of affirmative consent should be considered with caution in practice. For example, in the case of Spain, the recent Act on the Comprehensive Guarantee of Sexual Freedom 10/2022, September 6th, does not define sexual consent, but states that consent will only be understood to exist when it has been freely expressed through acts that, in accordance with the circumstances of the case, clearly express the will of the person. Our results lend support that in contexts of nonconsensual sex, victims commonly engage in passive behavior. Differences in Internal and External Consent for Nonconsensual Encounters across Context We also examined the extent that situational factors such as the familiarity of setting location may influence internal and external consent in the context of nonconsensual sex. Our results suggest that women who experienced nonconsensual sex in an unknown setting feel even less comfortable and less ready than when it occurred in a known place. This may be linked to feelings of vulnerability and limited agency, which may have significant implications for policies and court (Andersson & Edgren, 2018). In addition, more severe forms of sexual violence and rape tend to occur in unknown places (Tanoli et al., 2022), which could lead to a feeling of helplessness or impossibility to escape, and the victim freezing. We also compared internal and external consent across coercive and assaultive experiences. With regard to internal consent, women reporting on assaultive experiences indicated lower feelings of safety and want/consent compared with those who reported on nonconsensual sex due to their partner’s pressure and coercion. This may be explained because women experiencing coercion are less likely to blame perpetrator, therefore it is likely that they may not consider this is a form of sexual violence (Brewer & Forrest-Redfern, 2022). With regard to external consent cues, participants reported using passive behaviors indicating that they did not say or do anything and that sex —in this case, nonconsensual sex— just happened. More specifically, women who reported on experiences of sexual coercion had higher scores for the borderline pressure subscale than those who experience assault. Therefore, unwanted sex may be expressed by absence of resistance and even by behaviors that could be interpreted as receptivity, and consequently as indicators of consent (Beres et al., 2004; Hickman & Muehlenhard, 1999). Further research should explore the reasons of sexual decision making in sexual coercion, since they can vary from an intense fear to reprisals or extreme violence to blame feelings to avoid partner’s disappointment. Limitations and Future Research Some limitations should be considered in this study, including the generalizability of the data. Although participants ranged in age, our sample skewed toward being young and having a university degree. In addition, our sample comprised more women. Future research could be enriched by examining these scales in randomized samples of different ages, education levels, sexual orientation and genders, among other diverse sociodemographic characteristics. Additionally, it is worth mentioning the possible retrospective effect error of the participants who had experienced sexual violence. Another aspect not evaluated was the relationship status between our participants and their sexual partners —for both the consensual and nonconsensual experiences—. We recommend researchers measure this variable in the future. Although a known place generates a perception of safety, future research should evaluate this perception of safety or insecurity in the place where both consensual and nonconsensual sexual activity occurs. It is important to reiterate that we measured internal and external consent in the context of nonconsensual sex. Although we believe there is merit to examining these constructs in the context of nonconsensual sex —including providing further evidence for the validity of the measure— we recognize that these measures were not designed to capture feelings and cues associated with non-consent. Importantly, the ICS and ECS do not explicitly assess feelings (e.g., discomfort, disgust, and fear) or behaviors (e.g., saying no, pushing someone away) that indicate unwillingness or lack of consent. Thus, it can be difficult to determine some nuances in consent feelings and communication strategies for nonconsensual vs. sexually coercive experiences. Further research on this topic is needed to examine whether ICS and ECS are invariant based on gender, as well as cross-cultural studies to analyze whether the scales are invariant in Spanish-speaking populations, as previous studies have found cross-cultural differences in variables such as the double sexual standard (Sánchez-Fuentes et al., 2020). In addition, validating the measures in other countries will provide an opportunity to increase cross-cultural research and address cultural bias in the field of sexual violence/sexual consent research. There is evidence of the nuanced interplay between cultural expectations and past experiences in shaping sexual consent (Gomez-Pulido et al., 2024). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the ICS and ECS have been examined in nonconsensual contexts. Thus, this research expands our understanding about sexual consent as a continuum. According to Peterson and Muehlenhard (2007), consensual and wanted sex and nonconsensual and unwanted sex can be conceived as opposite ends of a theoretical continuum. We argue that the evaluation of consent should consider internal feelings of willingness to participate in the sexual activity and outward expressions of willingness to agree to engage in sexual activity in a similar kind of continuum. Finally, our findings indicate differences in the ICS/ECS dimensions depending on whether the sex is consensual or nonconsensual, which provides additional support for validity of these measures. This research attempts to provide new insights considering that sexual consent is a key aspect of sexual violence prevention (Jozkowski et al., 2016; 2022; Moyano et al., 2022; Willis & Jozkowski, 2018). Therefore, it is important to examine these dimensions of consent both in the context of consensual and nonconsensual sexual experiences. Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Moyano, N., Hidalgo-Muñoz, A. R., Sánchez-Fuentes, M. M., Jozkowski, K., & Granados, R. (2025). Examining internal and external consent in consensual and non-consensual contexts in women. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(1), 49-57. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a5 Ethical Approval The study was conducted in agreement with the guidelines issued by the Ethics Committee of University of Jaén, and was in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. These data are available upon reasonable request. A copy of the survey instrument is available to those who contact the corresponding author. References |

Cite this article as: Moyano, N., Hidalgo-Muñoz, A. R., Sánchez-Fuentes, M. D. M., Jozkowski, K., & Granados, R. (2025). Examining Internal and External Consent in Consensual and Non-Consensual Contexts in Women. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(1), 49 - 57. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a5

Corresponding author: Nieves Moyano (mnmoyano@ujaen.es).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS