Predictive efficacy of violence risk assessment instruments in Latin-America

[Eficacia predictora de los instrumentos de evaluación del riesgo de violencia en Latinoamérica]

Jorge Óscar Folino1

1Univ. Nal. La Plata, Argentina

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.11.006

Abstract

In Latin America, violence risk assessment used to be based in the non-structured clinical approach. An Argentinian cohort study that included violence risk assessment tools changed the tradition. The objective of this study is to inform of the observed predictive efficacy of these tools in the follow-up until March 2012. One hundred and fifty three consecutive pre-released convicted males were recruited from September 2001 through September 2004 in La Plata, Argentina. The pre-release assessment measures included the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, Assessing Risk for Violence V2, Structured Professional Judgment, and Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. The mean follow-up time was 1,290 days. Ninety-nine(64.7%) subjects had at least one general relapse, and 91 (59.5%) had at least one violent relapse. The incidence rate of violent recidivism was 16.8 per 100 person-years. While some indicators of predictive validity had no clinical significance, the time-dependent indicators did have clinical significance.

Resumen

En Latinoamérica, la evaluación del riesgo de violencia se basaba en la aproximación clínica no estructurada. A comienzos del presente siglo un estudio de cohorte argentino cambió la tendencia. El propósito de este estudio es informar sobre la eficacia predictiva de esos instrumentos en el seguimiento hasta marzo de 2012 de la cohorte de penados liberados. Se reclutó a 153 varones penados, candidatos a ser liberados consecutivamente bajo condiciones entre septiembre de 2001 y septiembre de 2004. Las medidas basales estaban constituidas por el Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised, Assessing Risk for Violence V2,Violence Risk Appraisal Guide y el juicio profesional estructurado. El período promedio de seguimiento fue de 1.290 días. Noventa y nueve (64.7%) sujetos tuvieron, por lo menos, una recidiva general y 91(59.5%) tuvieron, por lo menos, una recidiva violenta. La tasa de incidencia de recidiva violenta fue de16.8 por 100 persona-años. Algunos indicadores de validez predictiva no alcanzaron significación clínica, pero sí los estimadores tiempo-dependientes.

In Latin America, violence risk assessment (VRA) during the 20th century was based on a non-structured clinical approach ( Singh, CondemarĂn, & Folino, 2013 ). But in the last 10 years of the 20 th century, the academic and forensic fields restructured the theoretical conceptualization of the subject in Argentina. Risk assessment predictive quality and its value as a tool to inform prevention plans were highlighted ( Folino, 1994, 1996, 2004; Folino & Escobar-CĂłrdoba, 2004 ). Finally, around 2000 a joint effort between the Master Course in Forensic Psychiatry of the National University of La Plata (UNLP) and the Supreme Court of Justice of the Province of Buenos Aires established a program to acquire empirical evidence on VRA ( Folino, Marengo, Marchiano, & Ascazibar, 2004 ).

The objectives of the Pilot Program for Assessment of Risk in Released Males in the Prosecutor General Bureau of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Province of Buenos Aires were to create a procedure for systematic assessment of the risk of violent recidivism in forensic patients and in the inmates who were applying to any form of anticipated release, and to contribute to the creation of intervention programs that would help to decrease the recidivism rate. It was also a goal of the program to provide the judicial system with an assessment procedure that would be transparent, that the parties involved would be able to supervise it, and that would allow for follow-up assessments.

Due to the prevailing paradigm, there were notorious shortfalls in knowledge, including the base rate for criminal recidivism in populations released from prison. Determining this rate was one of the first aims of the Program. Thus, a cohort of males released in 1991 was formed and the official criminal registries for the subsequent 10 years were obtained. The result was that 34% had had at least one new conviction and 52% had at least one new charge ( Folino & Marchiano, 2002).

In addition, a protocol for pre-release assessment was designed. Nine internationally-used instruments, or parts of them, were translated: the Hare Psychopathy Checklist–Revised (PCL-R; Hare, 1991, 2003 ), the Assessing Risk for Violence V 2 (HCR-20; Webster, Douglas, Eaves, & Hart, 1997; Folino, 2003 ), the Violence Risk Appraisal Guide (VRAG; Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 1999; Quinsey & Lalumière, 1995 ), the Lifestyle Criminality Screening Form - Revised (LSCF–R; Walters, 2003a, 2003b ), the Iterative Classification Tree (ICT; Monahan et al., 2000; Steadman et al., 2000 ), the Rapid Risk Assessment for Sexual Offense Recidivism (RRASOR; Hanson, 1997 ), the Sexual Offender Risk Appraisal Guide (SORAG; Quinsey, Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 2006 ), the Child and Adolescent Taxon Scale (CATS; Quinsey et al., 1999 ), and the Cormier-Lang Scale ( Cormier et al., 1999).

A concurrent cohort study was designed to evaluate the predictive validity and reliability of the pre-release assessment protocol based on “Out” follow-up, from the moment of release on. Other components of validity of the translated instruments were tested as well ( Castillo, 2007; Folino, AlmirĂłn, & Ricci, 2007; Folino, Astorga, Sifuentes, Ranze, & Tenaglia, 2003; Folino, Castillo et al., 2004; Folino, Escobar-CĂłrdoba, & Castillo, 2006; Folino & Hare, 2005; Folino et al., 2005; Folino & Mendicoa, 2006 ).

The Argentinian studies were accompanied by other studies that were frontline in Latin America regarding the subject. In many of them the academic diffusion from the National University of La Plata was of main importance ( Folino & Raverta, 2006 ), including studies with the PCL-R and the HCR-20 in:

- •

Brazil ( De Borba Telles, Day, Folino, & Taborda, 2009; De Borba Telles, Folino, & Taborda, 2009 , 2012; Teitelbaum, 2010).

- •

- •

- •

Ecuador (Ochoa-Rosales, 2007).

Both the “Out” Argentinian cohort study and the “In” Brazilian cohort study – a follow up study of forensic mental health inpatients conducted at the RogĂ©rio Cardoso Forensic Hospital in Porto Alegre – supported the reliability and predictive validity of the VRAG, the Hare PCL-R, and the HCR-20 for forensic populations ( De Borba Telles et al., 2009a,2012; Folino, 2006 ), but not for convicted populations. The “Out” follow up for the Argentinian convicted and released cohort did not produce significant results until the follow-up of January 2007 ( Folino, 2009 ). Thus, it is important to prolong follow-up periods to investigate if there is variation in the rate of violent recidivism and if there is an increase in the predictive efficacy of the pre-release assessment measurements.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the violent and general recidivism rates of a cohort of released convicted male from time of release between September 2001 and September 2004 through March 2012 and to analyze the predictive validity of four VRA instruments included in the pre-release assessment.

Method ParticipantsThe cohort of the study comprised all males ( n = 178) who were consecutive candidates for release during the recruitment period (September 2001 - September 2004) in the Penal Execution Court No. 1 of the Judicial Department of La Plata, Argentina. Of the 178 males evaluated, 25 (14%) were forensic patients and 153 (86%) were convicted. The cohort of the present study comprises the 153 released convicted males; mean age at release was 29.4 years (age range, 20-75 years, SD 8.7).

The Penal Execution Court No. 1 was the only court during the recruitment period in the Judicial Department of La Plata, which has a population of 1 million inhabitants. The mean age of the present cohort was statistically similar to that of the cohort of convicts in the Province of Buenos Aires in 1991 ( n = 3, 324, t = 1.032, gl 95, p = .305, 95% CI = -0.84, 2.66) (Folino & Marchiano, 2002).

The index crimes were crimes against property (85%), threats, assaults, homicides, and attempted homicides (11%), sexual offenses (2%), and other crimes (2%).

Pre-release Assessment and InstrumentsAssessment was conducted before release of all convicted males with the following instruments: HCR-20 ( Webster et al., 1997), PCL-R (Hare, 2003), VRAG (Quinsey et al., 1999 ), and the Structured Professional Judgment (SPJ; Douglas & Ogloff, 2003 ). The SPJ was based on professional review following the guidelines of the HCR-20, and conclusions were expressed as low, moderate, or high recidivism risk. The results were transformed in an ordinal variable with a minimum of 1 and a maximum of 3 for statistical purposes. Recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews have informed that these instruments have a moderate predictive efficacy and values under the ROC curve between .66 and .74 ( Singh, Grann, & Fazel, 2011; Yang, Wong, & Coid, 2010 ).

As recommended ( Blomhoff, Seim, & Friis, 1990; Douglas & Ogloff, 2003; Monahan & Steadman, 1994 ), multiple methods were used to obtain the necessary information (judicial files, clinical and criminal records, psychiatric and social assessment interviews, and psychological and psychiatric forensic reports).

The first translated and commented Spanish version of the HCR-20 was used ( Folino, 2003; Webster et al., 1997 ). Local studies informed of alpha coefficients of .76 for Section H, .55 for Section C, and .88 for Section R; the agreement between evaluators as measured by the intraclass correlation coefficient was .94 for H, .75 for C, and .97 for R ( Folino et al., 2004a).

The authorized Argentinian research version of the PCL-R was used. Two independent studies had provided evidence for its reliability. The first study reported alpha coefficients of .86 for total scores, .83 for Factor 1, and .86 for Factor 2; an intraclass correlation coefficient of .89 for Factor 1 and .92 for factor 2; and .92 for Total Score. The comparison of two categorical diagnoses of three simultaneous evaluators with adjusted kappas was .90 ( Folino et al., 2003 ). In the second study, the results were even higher: alpha coefficient of .99 for Total Score, .98 for Factor 1, and .99 for Factor 2; the singular measure of the intraclass correlation coefficient was higher ( Folino & Castillo, 2006).

Two forensic psychiatrists conducted the clinical interviews of the pre-release assessment (simultaneously in 60% of the cases) and a social worker trained in the forensic field conducted the interviews of the participants and their families for information on environmental risk factors and to obtain other contact information. Evaluators were advised by lawyers who worked for the Penal Execution Court.

DesignThe study had a concurrent cohort design. The events of interest were “general recidivism,” which was any offense or crime or violent act, even though it did not have legal consequences and “violent recidivism,” which implied violence.

It was considered that the subjects were “in opportunity to recidivate” from the moment of release. Administrative censoring was March 1, 2012. The average follow-up period up to general recidivism or censoring was 1,277 days (range, 1 - 3,488 days). The mean time to violent recidivism or to censoring was 1,290 days (range, 1 - 3,488 days).

From September 2001 to September 2004, multiple information sources were used to obtain outcome information, including official records of new charges and interviews with released subjects and their families about every three months. Data from the interviews were obtained by trained social workers who were blind to the pre-release assessment ( Folino et al., 2005).

After that period only the official registries of new penal charges were used (Prosecutor General Bureau Office of the Province of Buenos Aires, Police of the Province of Buenos Aires, Federal Police and GendarmerĂa), though we also checked the Provincial Registry of People and GendarmerĂa for subjects who died or left the country. There was only one lost case due to death.

Predicted OutcomeThe recidivism measure was recorded as both a categorical and continuous variable with the Overt Agression Scale (OAS; Silver & Yudofsky, 1991; Yudofsky, Silver, Jackson, Endicott, & Williams, 1986 ).

As a categorical event, recidivism was considered either “charged” (robbery, homicide, etc.) or “violence with no penal accusation” (using a definition of violence from the HCR-20 ( Webster et al., 1997).

Any OAS score higher than 6 for a single recidivism event was considered “violent recidivism.”

Statistical AnalysisThe point biserial and Spearman correlations were obtained, as well as Kaplan-Meier's survival function and the Area Under the Curve Receiver Operating Characteristics (AUC–ROC). Multivariate logistic regression analysis and Cox regression ( Cox, 1972 ) were executed, after checking if the assumption of proportional hazards was met. Calibration components in risk assessment ( Singh, 2013 ) were also estimated. Age was selected as a control variable for the logistic regression analysis because of its association with recidivism ( Hill, Habermann, Klusmann, Berner, & Briken, 2008; Looman & Abracen, 2010; Lund, Hofvander, Forsman, Anckarsäter, & Nilsson, 2013; Quinsey et al., 1999; Webster et al., 1997 ). The variables were dichotomized as follows: Hare PCL-R score with a cutoff of 30 and VRAG and HCR-20 with the mean. The statistical analysis was made with the IBM SSPS software ( IBM Corp. SPSS Inc, 2011 ). The data was entered in an ad-hoc database with security measures.

Ethical ConsiderationsTwo conditions decreased the risk of ethics faults: a) the observational design maintains the confidentiality of the individuals of the sample; b) the assessments were part of the activities that had been ordered by the Court, with clear knowledge of all parties involved in each case, such as defense attorney, curators, and prosecutors. The data obtained was coded and entered in a database from the Prosecutor General Bureau of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Province of Buenos Aires. The project was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Institute of Bioethics and Humanities of the Mainetti Foundation, which is independent from the Judicial Power and the National University of La Plata.

ResultsDuring the follow-up period, 99 (64.7%) of the subjects had at least one general relapse and 91 (59.5%) subjects had at least one violent relapse. The incidence rate of violent recidivism was 16.8 per 100 person-years.

During the period in which information on recidivism was collected via interviews with individuals and their families, as well as by checking official records, recidivism events were reported by subjects in 14 (14.1%) of the 99 recidivating cases; in 50% of those 14 cases, official information of a second offense was also obtained.

Table 1 shows the mean scores obtained at pre-release assessment.

Descriptive Statistics of Pre-release Assessment Scores

| Instrument | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| PCL-R Total | 20.4 | 7.7 |

| Facet 1 Interpersonal | 3.9 | 2.3 |

| Facet 2 Affective | 5.5 | 2.0 |

| Facet 3 Lifestyle | 5.3 | 2.4 |

| Facet 4 Antisocial | 4.4 | 2.8 |

| VRAG | 11.7 | 9.7 |

| HCR-20 total | 20.1 | 6.9 |

| Subscale H | 11.7 | 4.2 |

| Subscale C | 4.7 | 1.9 |

| Subscale R | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| SPJ | 2.6 | 0.5 |

| Cormier-Lang System nonviolent crime | 15.6 | 31.2 |

| Cormier-Lang System violent crime | 16.8 | 37.8 |

Note. N = 153. PCL-R: Hare Psychopathy Checklist. VRAG: Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. HCR-20: Historical Clinical Risk- 20. SPJ: Structured Professional Judgment. Cormier-Lang System: Cormier-Lang Criminal History Score for Violent/Nonviolent Offenses.

The prevailing diagnoses were related to substance abuse and antisocial personality disorder ( Table 2).

Mental Disorders

| Axis I | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| 30480 – Polysubstance dependence | 68 | 44.4 |

| V7109 – No diagnosis on Axis I | 52 | 34.0 |

| 30500 – Alcohol abuse | 9 | 5.9 |

| 30520 – Cannabis abuse | 6 | 3.9 |

| 30390 – Alcohol dependence | 5 | 3.3 |

| 30420 – Cocaine dependence | 4 | 2.6 |

| 30560 – Inhalant dependence | 4 | 2.6 |

| 30430 – Cannabis dependence | 3 | 2.0 |

| 29690 – Mood disorder not otherwise specified | 1 | 0.7 |

| 3022 – Pedophilia | 1 | 0.7 |

| Total | 153 | 100.0 |

| Axis II | ||

| 3017 – Antisocial Personality Disorder | 106 | 69.3 |

| V7109 – No diagnosis on Axis II | 31 | 20.3 |

| 3019 – Personality disorder no otherwise specified | 15 | 9.8 |

| 30181 – Narcissistic Personality Disorder | 1 | 0.7 |

| Total | 153 | 100.0 |

Note . Diagnostic categories DSM IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

The association of the VRA baseline scores with dichotomous and interval outcome measures was estimated. In general, the point bi-serial correlations for the total values were higher for violent recidivism than general recidivism: HCR 20 (.207, p = .005 vs. .152, p = .03); VRAG (.269, p < .001 vs. .240, p = .001); PCL-R (.206, p = .005 vs. .179, p = .01); SPJ (.248, p = .248 vs. .236, p = .002). For each outcome measure the association with VRAG scores was the strongest, followed by SPJ. With respect to the HCR-20 subscales, the subscale H had the strongest point bi-serial correlation (.189, p = .02). In the case of PCL-R, the antisocial facet (Facet 4) was outstanding ( r = .254, p = .001). The results highlight the relevance of static factors associated with the transgressor lifestyle, which are measured by these scales. Similar results were obtained with the estimate of the AUCs ( Tables 3 and 4 ). The VRAG and the antisocial facet of the PCL-R were best at discriminating violent recidivating individuals.

Instruments and Discrimination Validity to General Recidivism

| Instrument | AUC | SE | p value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | ||||

| PCL R Total | .596 | .049 | .050 | .501 | .691 |

| Facet 1 Interpersonal | .525 | .050 | .614 | .426 | .623 |

| Facet 2 Affective | .534 | .051 | .484 | .435 | .633 |

| Facet 3 Lifestyle | .599 | .049 | .043 | .503 | .696 |

| Facet 4 Antisocial | .619 | .048 | .015 | .526 | .712 |

| HCR 20 | .589 | .048 | .068 | .495 | .683 |

| Subscale H | .586 | .048 | .080 | .491 | .681 |

| Subscale C | .543 | .047 | .377 | .450 | .636 |

| Subscale R | .556 | .050 | .250 | .458 | .655 |

| VRAG | .638 | .047 | .005 | .546 | .729 |

| SPJ | .611 | .049 | .023 | .516 | .707 |

Note . PCL-R: Hare Psychopathy Checklist. VRAG: Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. HCR-20: Historical Clinical Risk- 20. H: HCR- 20 Historical scale. C: HCR- 20 Clinical scale. R: HCR- 20 Risk scale. SPJ: Structured Professional Judgment. SE : Standard Error. AUC: Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic.

Instruments and Discrimination Validity to Violent Recidivism

| Instruments | AUC | SE | p value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | ||||

| PCL R Total | .619 | .047 | .012 | .527 | .711 |

| Facet 1 Interpersonal | .507 | .049 | .880 | .411 | .604 |

| Facet 2 Affective | .574 | .049 | .121 | .479 | .669 |

| Facet 3 Lifestyle | .605 | .047 | .027 | .513 | .698 |

| Facet 4 Antisocial | .643 | .045 | .003 | .555 | .732 |

| HCR 20 | .623 | .046 | .010 | .533 | .713 |

| Subscale H | .607 | .046 | .025 | .516 | .698 |

| Subscale C | .567 | .046 | .160 | .476 | .658 |

| Subscale R | .601 | .048 | .033 | .508 | .695 |

| VRAG | .656 | .045 | .001 | .568 | .743 |

| SPJ | .617 | .047 | .014 | .525 | .709 |

Note . PCL-R: Hare Psychopathy Checklist. VRAG: Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. HCR-20: Historical Clinical Risk- 20. H: HCR- 20 Historical scale. C: HCR- 20 Clinical scale. R: HCR- 20 Risk scale. SPJ: Structured Professional Judgment . SE : standard error. AUC: Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic.

For each VRAG category, a regular growing trend of the proportions of recidivating individuals was identified. While no subject was classified in the lowest category of risk, the percentage of recidivating individuals was 0%, 33%, 50%, 46%, 51%, 73%, 70%, and 100% for the categories 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 respectively.

Predictive validity was also determined by dichotomizing the total pre-release assessment scores. In the case of the PCL-R a cutoff of 30 was used (as recommended by the Technical Manual for the categorical diagnosis of psychopathy) and for the HCR-20 and the VRAG the means were used ( Table 5 ). Of the three instruments, the VRAG had the best predictive power.

Instruments and Performance Indicators

| Instrument | Cutoff | PPV | NPV | NND | NSD | RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCL-R | Psychopaty cutoff (> 29) | .68 | .42 | 1.5 | .72 | 1.18 (0.84, 1.65) |

| HCR-20 | Mean (> 20) | .67 | .49 | 1.5 | .96 | 1.31 (1, 1.71) |

| VRAG | Mean (> 12) | .72 | .53 | 1.4 | 1.08 | 1.52 (1.16, 2) |

Note . PPV: Positive Predictive Value. NPV: Negative Predictive Value. NND: Number Needed to Detain. NSD: Number Safely Discharged. RR: Relative Risk. PCL-R: Psychopaty Cheklist-Revised. VRAG: Violence Risk Appraisal Guide. HCR-20: Historical Clinical Risk- 20.

Logistic regression models were estimated with “violent recidivism” as the dependent variable. When controlling by age ( OR = 0.94; 95% CI .89, 99; p = .012), VRAG higher than the mean (VRAG > 12) doubled the risk of violent recidivism ( OR = 2.14; 95% CI 1.07, 4.35; p = .04), as did PCL-R higher than the mean (PCL-R > 20; OR = 2.13; 95% CI 1.07, 4,24; p = .03) and SPJ measured as an interval variable (minimum 1; maximum 3; OR = 2.13; 95% CI 1.08, 4.21; p = 0.3). However, HCR 20 higher than the mean and PCL-R > 29 showed no significant association when controlling for age. The associations had a marginal statistical significance and no associations were found when total values were entered as interval variables: VRAG ( OR = 1.04; 95% CI .1, 1.09; p = .03); PCL-R (OR = 1.06; 95% CI 1.01, 1.11; p = .01); HCR 20 (OR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01, 1.11; p = .03).

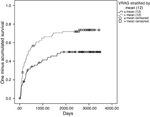

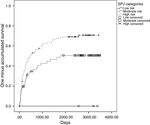

Estimations of Kaplan-Maier function for the VRAG stratified by the mean value and for the SPJ factor stratified in low, moderate, and high scores showed that the greater the risk factor, the higher the accumulated probability of general recidivism during the follow-up time, log rank (Mantel-Cox) = 7.6 (1); p = .006 and log rank (Mantel-Cox) = 7.9 (2); p = .02, respectively. On the other hand, the Kaplan-Meier Function for the HCR-20 stratified by the mean and the PCL-R total stratified by the mean or by the cutoff score of 30 showed no significant differences.

The trend was even more noticeable when calculating the Kaplan-Meier with violent recidivism as the outcome: VRAG, log rank (Mantel-Cox) = 9.5 (1); p = .002; and of those having greater risk according to the SPJ, log rank (Mantel-Cox) = 8.44 (2); p = .015 (Figures 1 and 2 ). Likewise, Kaplan-Meier function with the HCR-20 stratified by the mean and the PCL-R total, either stratified by the mean or by the cutoff score of 30 showed that those that had higher scores in the instruments also had the higher accumulated probability of recidivism with violent acts, but the differences were not significant: HCR-20, log rank = 2.99 (1); p = .08; PCL-R stratified by the means, log rank = 3.31 (1); p = .07; PCL-R stratified by cutoff score of 30, log rank = 0.77 (1); p = .38.

Taking into account the significant result of the function of Kaplan-Meier, Cox regression was estimated with age at release and the dichotomized VRAG factor as co-variables. Controlling for age, RR = .951 (95% IC 0.917, 0.985); p = .006, the VRAG value higher than the mean increased the rate of violent recidivism 57%, RR = 1.573 (95% IC 1.023, 2.419), p = .039.

DiscussionThis study, as part of a program created at the beginning of the millennium in Argentina, has helped to disseminate a systematic style of assessment of risk of violence over traditional non-systematic practices in Latin America. The systematic methodology resulted in a technically improved model with respect to the previous model based on “beliefs and thoughts” that had various vulnerabilities ( Monahan, 1981a, 1981b; Quinsey et al., 1999; Rice, Harris, & Quinsey, 2002 ) and that, due to the non-systematic way of working, created barriers to explore its efficacy. It should be noted that, with independence of results, this study made it possible to test the reliability and predictive validity of a battery of instruments to assess the risk of violent recidivism, for the first time in Latin America. Thus, the program achieved its objective and inaugurated a period of diffusion so that other experts would add evidence to the complex area of violence risk assessment, which sits in the interface of law and mental health.

This study analyzed the predictive validity of various VRA assessment tools in a cohort of released convicted males in Argentina. It provides valuable information about which VRA tool was most reliable, and the results can be used for comparisons with other populations. The long recruitment period of the consecutive candidates for early release enabled us to obtain a representative profile of the prison population at the moment of “leaving” the prison system.

Evidences from several studies support integrated evaluation and intervention according to the model of Risk-Need-Responsivity ( Andrews & Bonta, 2010; Andrews, Bonta, & Wormith, 2006 ). In Argentina, common day practice is far away from the systematic use of the model, but this study shows its plausibility. As found in other countries ( RodrĂguez et al., 2011 ), substance abuse disorders was an outstanding health problem. The program established a thorough diagnostic system for substance abuse disorders, which lead to referral to treatment in the community according to the risk and needs principles. On the other hand, a biochemical monitoring system was implemented. Drug metabolite testing in different substrates (urine, hear, nails) reinforced the monitoring and re-intervention in those cases with a decreased predisposition to withdrawal ( Folino, Arado, Ferrari, & Marengo, 2002 ).

General and violent recidivism rates (65% and 59% respectively) reached in a 3.5-year follow up were much higher than was estimated with a 1991 cohort study from a single province in Argentina with a longer follow-up time ( Folino & Marchiano, 2002 ). The higher rates are worrisome for public security and from a preventive point of view. In addition to their own original vulnerabilities, people released from prison also face the stressors of social re-incorporation ( Folino et al., 2005 ). Thus, there is a clear need for the state to create programs for secondary prevention for this population. The recidivism rates in the present study might be useful as baseline data to compare the impact of future programs aimed at diminishing recidivism rates.

This study found that VRA instruments improve prediction of recidivism rates, but with low efficiency. The results show a lesser efficiency than those from studies in other countries included in recent meta-analyses ( Singh et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2010 ). The four instruments predicted violent recidivism better than general recidivism, contrary to the recent findings with other instruments and with bigger populations ( Zhang, Roberts, & Farabee, 2011 ). The percentage of subjects with a recidivism event increased according to the risk classifications in the nine categories of the VRAG, and the VRAG was the only instrument that reached an AUC of .65 for violent recidivism. But the index is still below .70, which is considered clinically significant.

Predictive efficiency was greater when the probability of accumulated recidivism in the follow-up time was considered. Kaplan-Meier function showed that individuals who had been exposed to greater risk according to VRAG classification and the SPJ had a significantly greater probability of both general and violent recidivism. The results suggest that preventive services should be provided mostly during the first period after release. They also add clinical relevance to the use of instruments.

Age has traditionally been significantly and inversely associated with violent recidivism ( Hill, Habermann, Klusmann, Berner, & Briken, 2008; Looman & Abracen, 2010; Lund, Hofvander, Forsman, Anckarsäter, & Nilsson, 2013; Quinsey et al., 1999; Webster et al., 1997 ). In multivariate analyses controlled for age, the VRAG maintained its predictive value.

The results of the PCL-R were not in line with early studies that reported a high violence predictive power for the diagnosis of psychopathy ( Harris, Rice, & Cormier, 1991; Salekin, Rogers, & Sewell, 1996 ). The slightly better performance found with facets 3 and 4 suggests that preventive measures aimed at addressing criminogenic factors differently than interpersonal or affective personality factors could be more beneficial ( Andrews & Bonta, 2003; Bonta, Law, & Hanson, 1998; Yang et al., 2010 ). There is also the possibility that the effect of personality factors on the risk for violent recidivism is surpassed by socioeconomic and political instabilities, such as those experienced in Argentina from the turn of the century. A recent study in England and Wales has also shown predictive difficulties in psychopathic subjects ( Coid, Ullrich, & Kallis, 2013 ). The authors suggest that one possible reason is that the items of the instruments show little variation in psychopathic offenders and, therefore, are not adequate to differentiate those at high and low risk for violent reoffending. Further research is needed to find better indicators of social performance during the reincorporation period and to identify the most sensitive personality factors.

One limitation of the study is the decrease in information sources in the follow-up period since the last quarter of 2004, when the interviews with released subjects and their families were stopped. The strengths of the study include that the social workers were blinded to the pre-release assessment, the representativeness of the sample, and the wide range of sources of official records for new charges.

The present study's findings complement the results of previous studies in Latin America. While previous Latin American reports supported the predictive validity of the instruments in forensic population ( De Borba Telles et al., 2012; Folino, 2006 ), this study suggests caution about risk assessment when the targeted population is made up by convicts. Future studies should identify local risk factors and look for any interactions with regional socioeconomic conditions.

The performance of these instruments is far from optimal and there is a need to focus on preventive actions in cases that are classified as high risk, as well as in those that are low risk ( Large, Ryan, Callaghan, Paton, & Singh, 2014 ). A future study is planned to explore the distributions of individual risk factors in the different categories formed by the omnibus measure, with the hypothesis that there are different factors that influence different subgroups. This would allow for a refinement in the assessment process and in the planning of interventions.

Unfortunately, the knowledge and diffusion of structured and actuarial systems of assessment is very new in Latin America, as is the acknowledgement of the importance of research on the subject. The lack of dissemination of this kind of systematic assessment prevents studies with larger samples and makes it difficult to adapt the VRA instruments as it occurs elsewhere in the world ( Ragusa-Salerno, Ostermann, & Thomas, 2013; Rettenberger, Haubner-Maclean, & Eher, 2013; Zhang et al., 2011 ;). Further, the penitentiary institutions in Latin America remain disconnected to the precarious “out” services and institutional actions are carried out inconsistently as short-term policies or in reaction to media comments. We will have to wait for the use of evidence-based practices and for bridging the gap between science and practice in penitentiary institutions.

Conflict of InterestThe present study had no specific financing and was conducted as part of the official work for the Prosecutor General Bureau of the Supreme Court of Justice of the Province of Buenos Aires in a covenant with the Master Course in Forensic Psychiatry at the School of Medicine of the National University of La Plata.

The author translated the instruments jointly with an official translator. The results of the present study were provided in a work report to the judicial institution.

Previous results of the program were published in articles mentioned in the bibliography.

Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

CrossRef

CrossRef