Leaving the Teaching Profession: Examining the Role of Social Support, Engagement and Emotional Intelligence in TeachersŌĆÖ Intentions to Quit

[Dejar la profesi├│n docente: an├Īlisis del papel del apoyo social, el engagement y la inteligencia emocional en la intenci├│n de abandono del profesorado]

Sergio Mérida-López1, Martín Sánchez-Gómez2, and Natalio Extremera1

1University of M├Īlaga, Spain; 2Universitat Jaume I, Castell├│n, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a10

Received 19 September 2019, Accepted 2 March 2020

Abstract

The study aimed to test mediator and moderator factors in the relationship between workplace social support (i.e., perceived support from colleagues and supervisors) and intentions to quit in a sample of teaching professionals. Specifically, utilizing job-demands-resources theory to focus on social support, we examined whether work engagement mediated the relationship between workplace social support and intentions to quit. Moreover, the potential moderator role of emotional intelligence in the proposed model was tested. The study sample comprised 1,297 teaching professionals (64.8% females) working as preschool, primary, and secondary teachers in several centers in eastern and southern Spain. The main results demonstrated that work engagement totally mediated the relationship between social support from colleagues/supervisors and intentions to quit. The findings showed that teachers’ levels of emotional intelligence significantly moderated the indirect paths between perceived support from colleagues/supervisors and intentions to quit. Teachers with the lowest levels of work engagement reported low support from colleagues or supervisors, togetherwith low emotional intelligence. Similarly, highest intentions to quit was reported by those teachers reporting low work engagement and low emotional intelligence. Finally, we discuss the relevance of these findings for basic and applied research seeking to retain a more engaged teaching force.

Resumen

Este estudio pretende evaluar los factores mediadores y moderadores en la relación entre el apoyo social organizacional (apoyo percibido de compañeros y supervisores) y los niveles de intención de abandono en una muestra de profesionales de la enseñanza. Específicamente, usando la teoría de demandas y recursos laborales y centrándose en el apoyo social, se examina si el engagement laboral media la relación entre apoyo social organizacional e intención de abandono. Además, se analiza el posible papel moderador de la inteligencia emocional en el modelo propuesto. La muestra del estudio esta compuesta por 1,297 profesionales de la enseñanza (64.8% mujeres) que trabajaban como docentes de Infantil, Primaria y Secundaria en varios centros del este y sur de España. Los resultados principales demostraron que el engagement laboral mediaba totalmente la relación entre el apoyo social de compañeros y supervisores y la intención de abandono. Los hallazgos mostraron que el nivel de inteligencia emocional de los docentes moderaba significativamente las relaciones indirectas entre el apoyo percibido de compañeros y supervisores y la intención de abandono. Los docentes con un nivel más bajo de engagement laboral informaron de bajo apoyo de compañeros y supervisores, así como de un bajo nivel de inteligencia emocional. Igualmente, aquellos docentes con bajo engagement laboral y baja inteligencia emocional informaron de mayores niveles de intención de abandono. Finalmente, se discute la importancia de estos hallazgos para la investigación básica y aplicada enfocada a la retención de un capital docente comprometido.

Keywords

Social support, Work engagement, Intention to quit, Emotional intelligence, Teaching professionalsPalabras clave

Apoyo social, Engagement laboral, Intenci├│n de abandono, Inteligencia emocional, Profesionales docentesCite this article as: Mérida-López, S., Sánchez-Gómez, M., & Extremera, N. (2020). Leaving the Teaching Profession: Examining the Role of Social Support, Engagement and Emotional Intelligence in TeachersŌĆÖ Intentions to Quit. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(3), 141 - 151. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a10

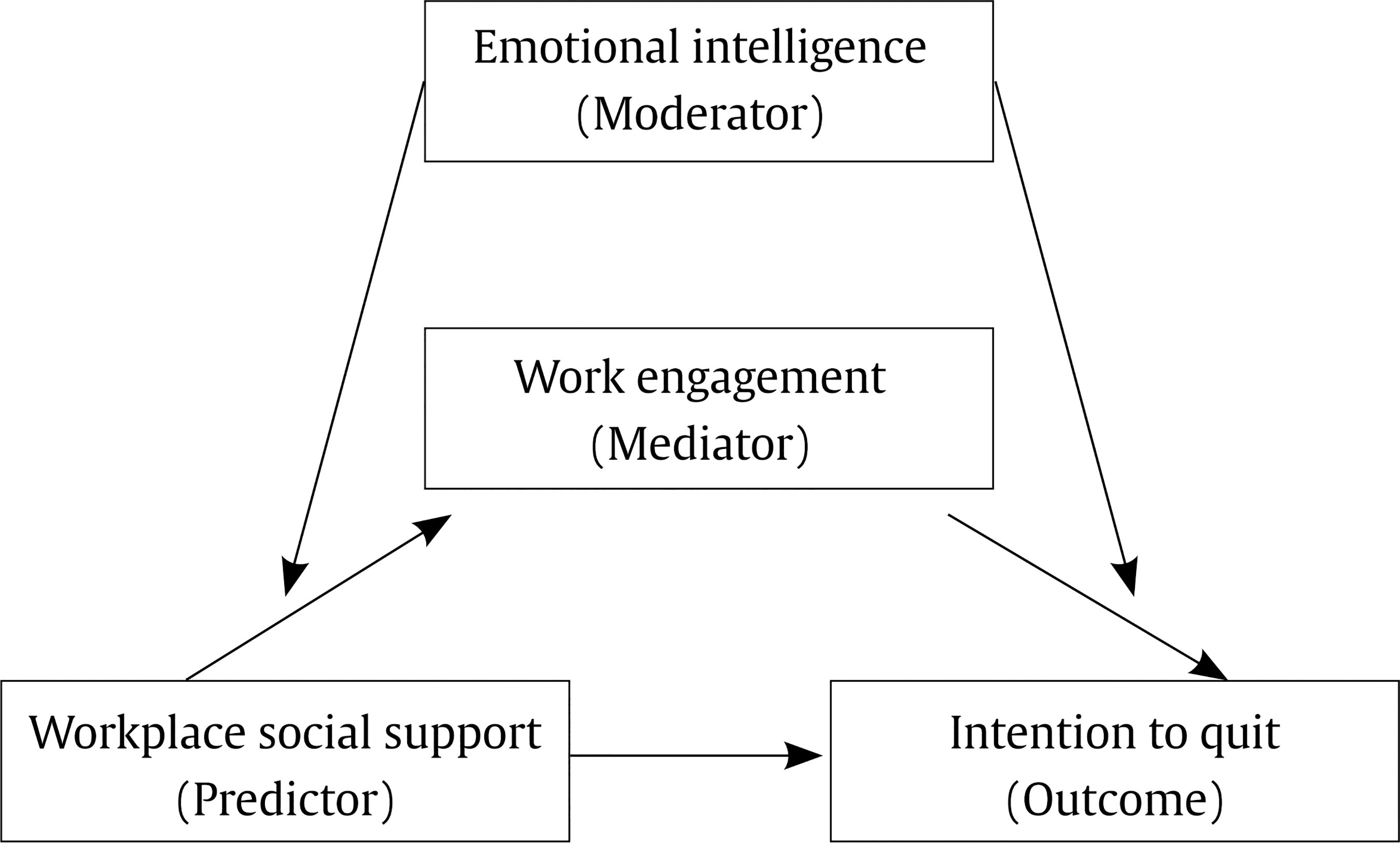

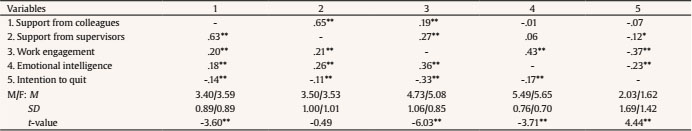

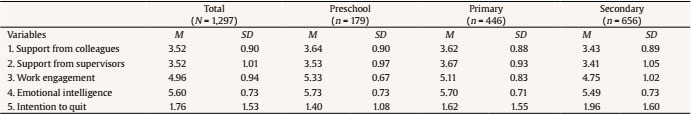

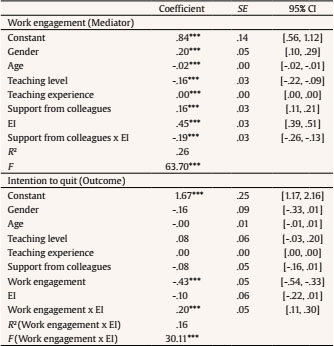

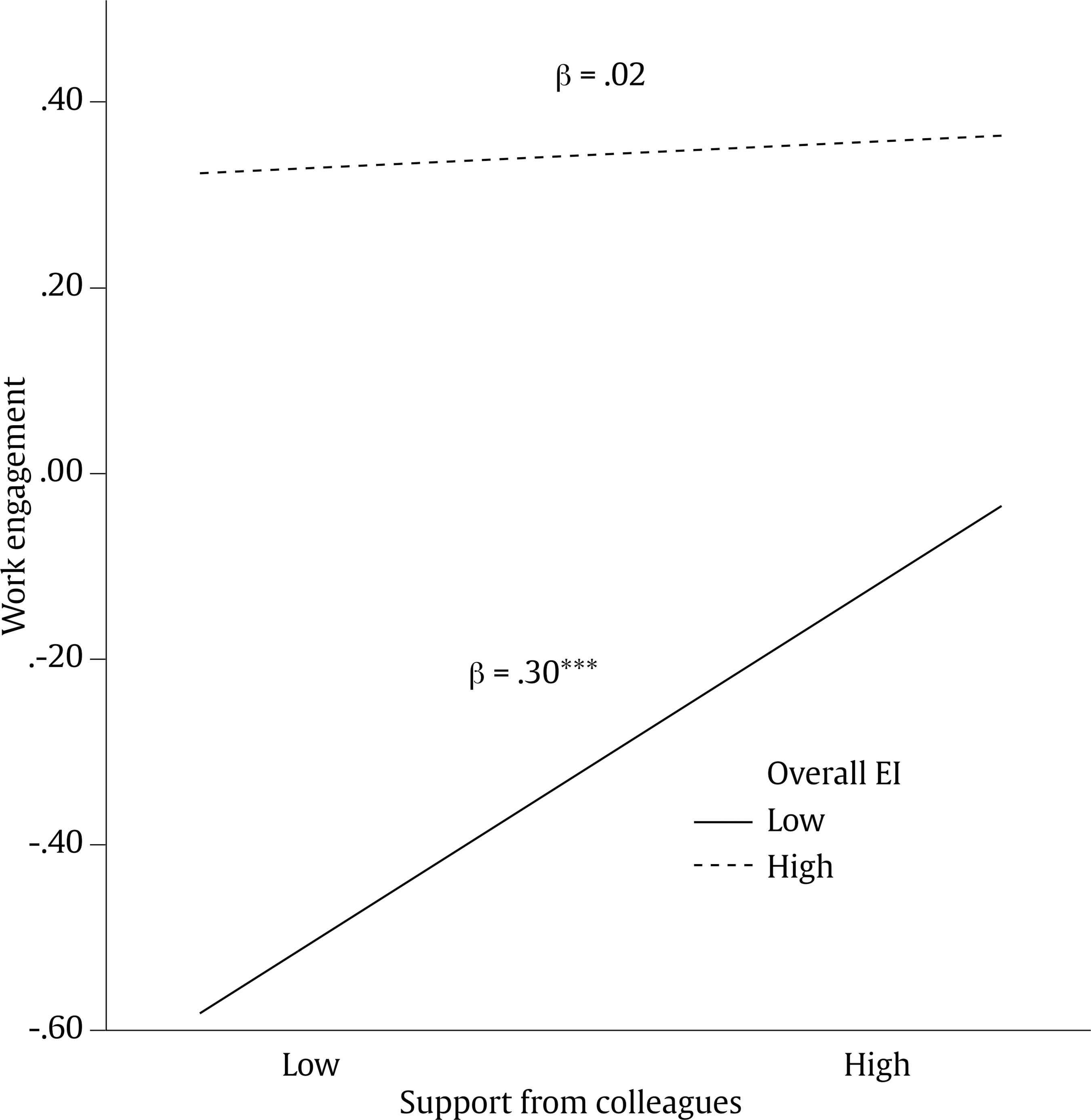

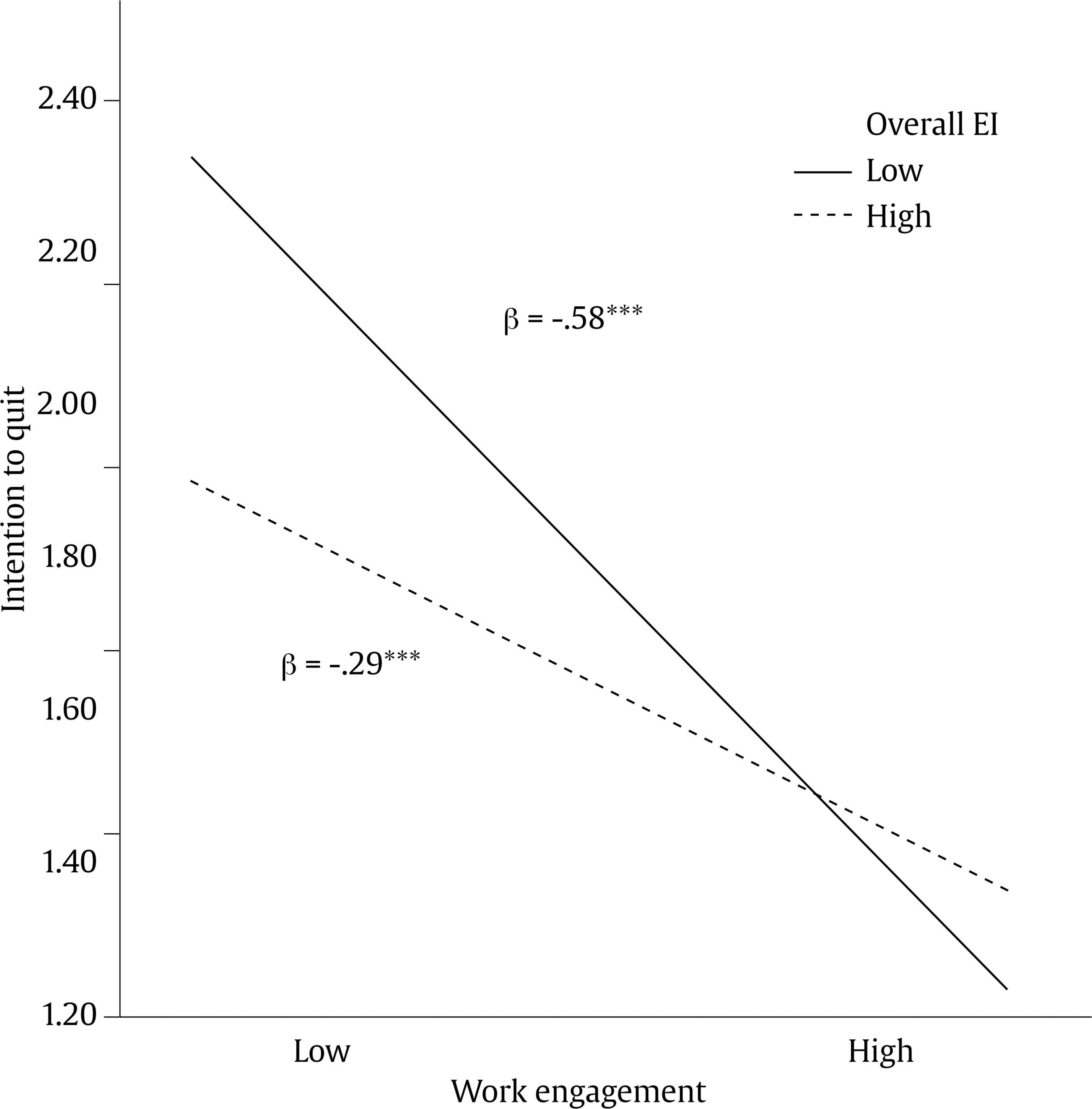

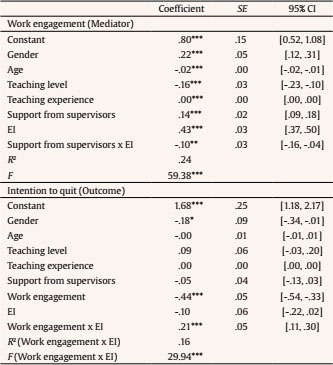

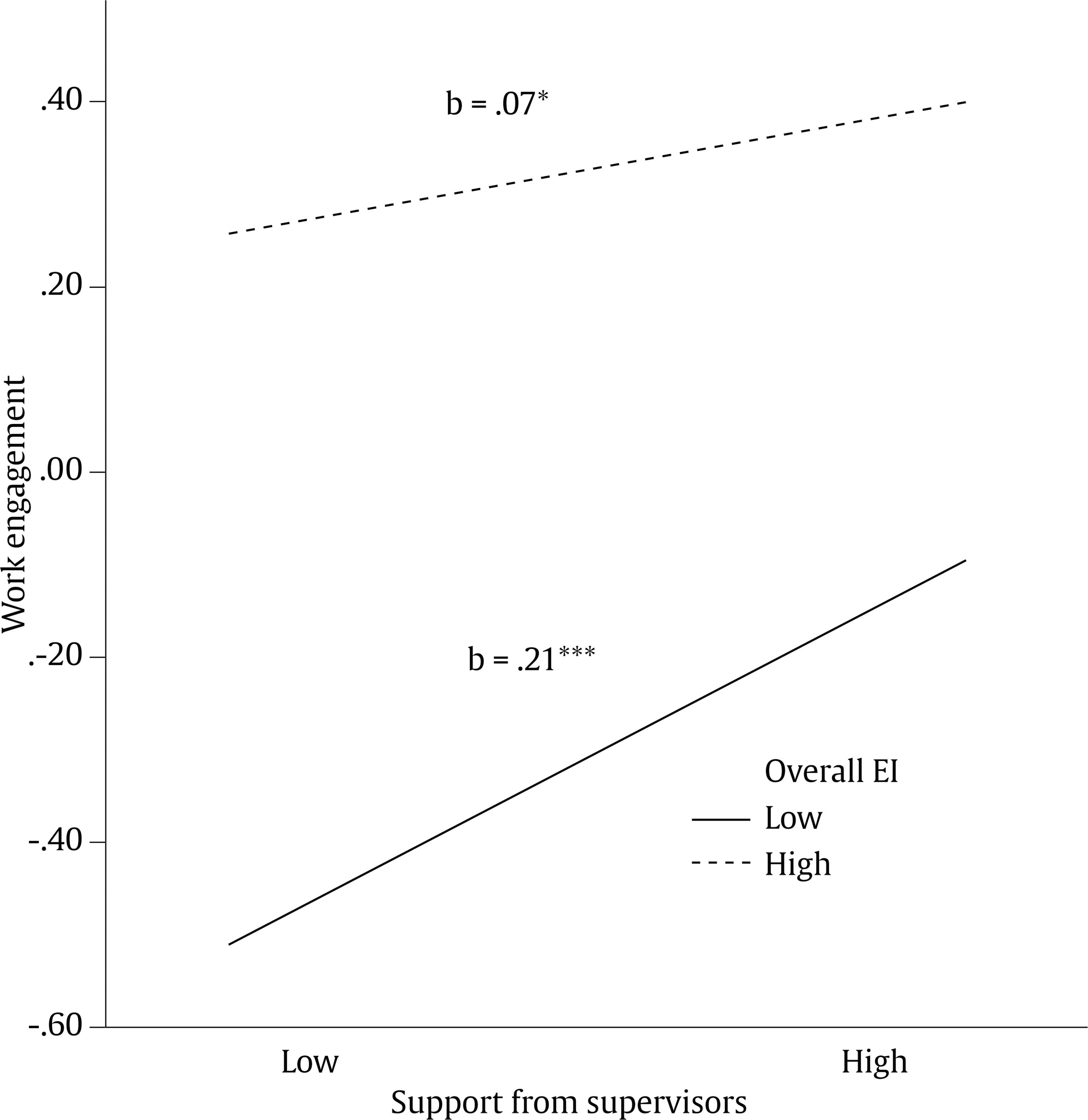

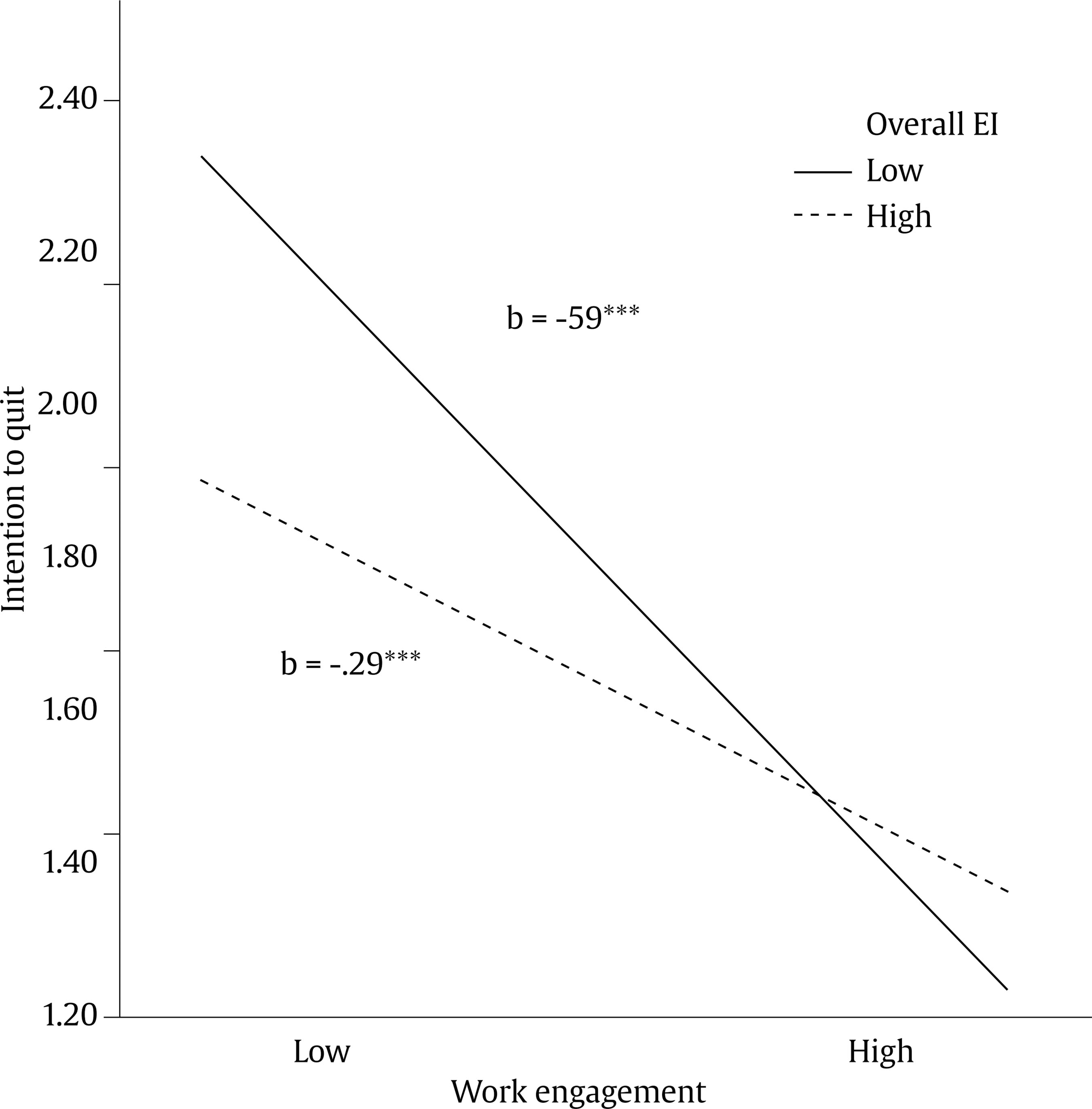

nextremera@uma.es Correspondence: nextremera@uma.es (N. Extremera).In recent decades, accumulating research has highlighted teacher attrition as an alarming issue for policymakers and social and educational administrators, mainly due to the cost of mental health treatment for teachers, the increase in healthcare expenditure and, ultimately, a decrease in student learning (Craig, 2017). Recent data from several countries have shown that the number of teachers leaving the profession within the first five years is placed at between 8% and 50% (Kelly et al., 2019). For instance, data from the United States show that 25% of teachers leave the profession before their third year (Chang, 2009), and 25% to 40% of educators in western countries consider withdrawal within their first five years of teaching (Guarino et al., 2006). These rates have increased to the point that prior research has shown that more teachers leave voluntarily in comparison to those who remain in the classroom until retirement (Ingersoll et al., 2014). Teacher attrition impairs a wide variety of economic, social, and educational outcomes. For instance, this issue conveys high costs for taxpayers (Ronfeldt et al., 2013). Likewise, it has been reported that replacing one leaving teacher can cost between $8,000 and $20,000 (Ingersoll, 2001). Teacher attrition reduces teamwork, diminishes a school’s sense of community, and negatively affects student learning (Guin, 2004; Ronfeldt et al., 2013). In this context, numerous schools are currently dealing with a significant challenge regarding building and maintaining a healthy and high-quality teaching force (Sutcher et al., 2019). It has been demonstrated that intentions to quit is predictive of actual withdrawal (Thoresen et al., 2003). We therefore focused on this variable as an indicator of eventual teacher attrition (Høigaard et al., 2012; Klassen & Chiu, 2011). Researchers on teacher attrition agree that several factors account for teachers’ decisions regarding leaving or staying in their profession (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Clandinin et al., 2015). It has been shown that specific organizational factors (e.g., low salaries, poor relationships with colleagues and supervisors, workload) and individual factors (e.g., sex, workplace seniority, psychological resources) lead teachers to consider occupational withdrawal (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Chan et al., 2008; Guarino et al., 2006). For instance, attrition rates are higher for female than for male teachers (Guarino et al., 2006). Moreover, there is evidence of younger teachers being more likely to leave teaching than older teachers (Borman & Dowling, 2008). Although teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions can be predictive of actual departure (Ladd, 2011), there are individual differences in psychological resources (e.g., resilience or emotional abilities) explaining teachers’ decisions about leaving their profession (Chesnut & Cullen, 2014; Hong, 2012). This study examines both organizational (i.e., workplace social support) and individual resources (i.e., emotional intelligence) as positive predictors of teachers’ work motivation and associated low intentions to quit. This paper may thus expand current understanding of social and personal factors affecting teachers’ decisions about leaving and so benefit further efforts for retaining human capital within educational settings. Workplace Social Support and Intentions to Quit Job Demands-Resources theory (JD-R) (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Demerouti et al., 2001) proposes relations among work characteristics (namely, job demands and job resources) and health, motivation, and work outcomes (especially well-being, motivation, and work performance). According to this framework, there are two independent processes (i.e., health impairment process and motivational process) that ultimately explain work outcomes. This theoretical background has attracted extensive attention worldwide and has served to develop basic and applied psychosocial research with teacher samples (Taris et al., 2017). Considering JD-R theory, workplace social support – defined as the physical, emotional, informative, and instrumental assistance that an individual perceives from their environment (Cobb, 1976) – is an important type of job resource derived from interpersonal relationships within the organization. In this study, we focus on perceived social support from colleagues and supervisors. While collegial relationships may play a significant role when a teacher is confronted with instructional issues, principals often provide support regarding classroom instruction issues (Van Maele & Van Houtte, 2012). Nonetheless, literature highlights both colleagues’ and supervisors’ provisions of support as key within educational settings as these dimensions exert a positive influence on teachers’ work-related well-being and motivation (Collie et al., 2017; Van Maele & Van Houtte, 2012). Research on workplace social support indicates that building a positive school climate with enhanced support from both principals and colleagues is a promising avenue to prevent teacher leaving (Collie et al., 2017; Ju et al., 2015). For instance, it has been demonstrated that emotional and social support networks are positively related to job satisfaction, which sustains the value of this job resource in educational institutions (Thomas et al., 2019). Finally, available knowledge shows that perceiving the support of peers and supervisors acts as a key element to achieving safer and healthier work environments, where teachers are motivated to exert their best efforts and improve their commitment to teaching, which leads to a reduction in withdrawal intentions (Geiger & Pivovarova, 2018; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018). The Mediator Role of Work Engagement A great deal of attention has been paid to negative factors that are predictive of teachers’ reduced commitment or increased intention to quit (e.g., lack of job resources, job demands, or stress; Taris et al., 2017). With respect to educational settings, the focus has been primarily put on teacher burnout as a negative job outcome linking deleterious organizational aspects with impaired health and negative attitudes towards teaching. Building upon the positive organizational psychology movement, it has been advocated that one way to reduce teacher attrition is to create awareness of the factors contributing to teachers’ satisfaction and commitment (Collie et al., 2017; Taris et al., 2017). Therefore, there is a growing interest in examining which organizational and personal resources lead to teacher well-being and satisfaction and to a reduced intention to withdraw (Hong, 2012; Klassen & Chiu, 2011). In order to expand this promising line, we examined the influence of workplace social support and emotional intelligence (EI) on teachers’ work engagement and intention to quit. Evidence shows that teachers are more likely to stay if they perceive that they work in a supportive and collaborative environment (Achinstein et al., 2010). These supportive relations may not only affect teachers’ motivation at work, but they can also improve student achievement (Kaufman et al., 2012). Accordingly, earlier research has shown that perceived organizational support influences burnout (Ju et al., 2015), organizational commitment (Brenninkmeijer et al., 2010), and intention to leave (Conley & You, 2017). Literature based upon the JD-R theory states that the link between a job resource such as workplace social support and intention to quit would not be direct, but instead would be mediated by a motivational factor such as work engagement (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Work engagement is defined as a motivational state of work characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2002). This construct has been often examined as a motivational factor explaining the relationship between job characteristics and work outcomes, such as turnover (Halbesleben, 2010). There is evidence suggesting that the relationship between working characteristics and teachers’ intentions to leave are mediated by work engagement (You & Conley, 2015). Support from colleagues and supervisors positively relates to engagement (Bakker et al., 2007). Moreover, work engagement is regarded as a motivational driver of intention to stay within an occupation (Agarwal & Gupta, 2018; Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2008). Prior studies conducted with newly qualified teachers have reported findings in this vein (Høigaard et al., 2012). In sum, work engagement appears to be a mediator factor explaining the relationship between workplace social support (i.e., support from colleagues and support from supervisors) and intention to quit. The Moderator Role of Emotional Intelligence Following Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) model, EI is defined as the ability to perceive, appraise, and express emotion accurately; the ability to access and generate feelings when they facilitate cognition; the ability to understand affect-laden information and make use of emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote growth and well-being (Mayer & Salovey, 1997). Accumulative research has shown that EI is a key psychological resource associated with better personal (Sánchez-Álvarez et al., 2016), interpersonal (Alonso-Ferres et al., 2019), and organizational functioning (Mérida-López et al., 2017a). Furthermore, EI is increasingly regarded as a personal resource within the JD-R theory, meaning that it may function similarly to job resources (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). On the one hand, personal resources are regarded as direct predictors of well-being. For instance, EI positively relates to work engagement beyond the variance accounted for by personality traits (Akhtar et al., 2015) and it also associates with dimensions of teachers’ work engagement (Castillo-Gualda et al., 2017). On the other hand, personal resources may moderate the relationship between job characteristics and well-being (Bakker et al., 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). In the same vein, Newton et al. (2016) reported that EI buffered the relationship between job stressors and work-related satisfaction in the healthcare sector. Similarly, EI is found to interplay with job characteristics (i.e., role ambiguity) to predict teachers’ levels of work engagement (Mérida-López et al., 2017b). These findings accord with the moderator model of EI proposed by Côté (2014), stating that the relationship between contextual factors (i.e., colleagues’ and supervisors’ support) and work criteria (i.e., work engagement) may be moderated by workers’ EI levels. With regard to JD-R theory, intention to quit is regarded as a negative outcome among individuals experiencing low motivation at work (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). However, differences in EI may attenuate or exacerbate the effects of workers’ state affectivity and mood on their intention to quit (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017). A recent meta-analytic review supports the assumption that emotionally intelligent workers are more satisfied at work, committed to their professions, and are therefore less likely to engage in turnover behaviors (Miao et al., 2017). Regarding teaching context, teachers’ EI is associated with lower burnout as well as with higher teacher satisfaction (Rey et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2013). Beyond direct effects of EI on enhanced work-related attitudes, current knowledge suggests that EI may interact with work engagement to explain intention to quit. One potential mechanism of this effect is that emotionally savvy individuals may be more aware of the positive implications of engagement at work. As such, engaged workers with high EI would better grasp and appreciate the significance of experiencing pride and vigor regarding their work, which would facilitate desires about remaining in their profession. Conversely, workers experiencing disengagement and perceiving themselves as unable to manage their own and others’ emotions are more likely to hardly trust in their abilities to control and act in their environment successfully, thereby being more reactive to emotion-invoking experiences at work (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017). For instance, employees experiencing low engagement and scoring low in EI are more likely to be involved in deviant organizational behaviors (De Clercq et al., 2014). Therefore, one could expect teachers experiencing low work engagement and perceiving themselves with low EI to be more willing to consider leaving the teaching profession than their counterparts with higher EI abilities. There are both theoretical and empirical reasons for expecting that the magnitude of the associations among workplace social support, work engagement, and intention to quit might vary depending on EI levels. Although previous research has reported interactive effects between workplace social support and emotion-regulation ability to predict levels of job satisfaction (Mérida-López et al., 2019), to date there is no evidence on the interplay of dimensions of workplace social support and EI as predictors of work engagement. Similarly, research examining the relationship between EI and intention to quit among teachers is still scarce (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017). Therefore, this study may contribute to the current knowledge on psychosocial antecedents of teacher intention to quit, as it examines a moderated-mediation model in which workplace social support influences the intention to quit through work engagement, with the magnitude of these indirect relationships being modulated by levels of EI (see Figure 1). Figure 1 Proposed Moderated-Mediation Model to Empirically Test the Associations between Workplace Social Support, Emotional Intelligence, Work Engagement, and Intention to Quit.   The Present Study The main objectives of this study were: 1) to assess whether work engagement mediates the relationship between workplace social support (i.e., support from colleagues and support from supervisors) and intention to quit and 2) to evaluate the moderating role of EI on the indirect effect of workplace social support on intention to quit through work engagement. Based upon prior research, the proposed hypotheses were: 1) teachers’ work engagement mediates the relationship between support from colleagues and intention to quit (H1a); 2) teachers’ emotional intelligence moderates the indirect pathways from support from colleagues to intention to quit (H1b); 3) teachers’ work engagement mediates the relationship between support from supervisors and intention to quit (H2a); and 4) teachers’ emotional intelligence moderates the indirect pathways from support from supervisors to intention to quit (H2b). These hypotheses are displayed in Figure 1. Participants Following a cross-sectional design, approximately 2,800 questionnaires were distributed among educational centers mostly placed in southern and eastern Spain. A total of 1,378 questionnaires were collected, yielding a response rate of 46%. Due to incomplete data, 81 surveys were removed. Therefore, the final sample comprised 1,297 teaching professionals (64.8% female), of whom 50.6% were secondary teachers, 34.4% were primary teachers, and 13.8% were preschool teachers. Sixteen participants did not specify their teaching level (1.2%). The mean age was 43 years (M = 43.06, SD = 9.34, range = 22-67 years). Teaching experience was approximately 11 years, and average organizational tenure was 6 years. With respect to the educational center, a 72.6% of the teachers worked at a public center, 10.6% at a semi-public or private center, and 16.8% did not report this data. Regarding their contracts, 70.1% of teachers were working with civil servant status, that is, they reported having an indefinite contract at state-run institutions. While 19.1% reported having a temporary contract, the remaining 10.8% of participants were either working with an ongoing contract (7.6%) or did not specify their contract type (3.2%). The marital status of the participants was: 57.4% married, 23.7% single, 10.3% in a relationship, 6.1% separated/divorced, and 1.1% widow/widower. Eighteen participants did not report their marital status. Design and Procedure In line with previous field studies, teaching professionals were contacted with the help of psychology students who had been previously trained in the administration of questionnaires. This procedure was followed in line with the guidelines provided for applying this sampling technique (Wheeler et al., 2014). Students contacted several educational centers, asking headteachers and teaching professionals whether they would be willing to participate in a cross-sectional survey on psychosocial factors and motivation among teaching professionals. The students received extra course credit for their participation. The participants were given a brief introduction to the main goal of the study and the voluntary and confidential nature of their participation was explained. Once the completed questionnaires had been collected, they were returned to the research staff for further statistical processing. The procedure was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Málaga (66-2018-H). Instruments The surveys included several aspects of sociodemographic data (i.e., age, gender, marital status, teaching level, contract and school type, teaching experience, and organizational tenure), in addition to the main study variables. Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire II (Pejtersen et al., 2010). The Copenhagen scale was used to measure social support. This scale includes two three-item scales assessing perceived support from colleagues (e.g., “How often are your colleagues willing to listen to your problems at work?”) and supervisors (e.g., “How often do you get help and support from your nearest superior?”), with responses ranging from 1 (always) to 5 (never). Scores were recoded so that higher scores reflected higher perceived support at work. We used the Spanish version, which has shown good psychometric properties (Moncada et al., 2014). Cronbach’s alpha for the reliability of this instrument in this study was .78 for support from colleagues and .79 for support from supervisors. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli et al., 2002). This instrument was used to measure work engagement and consists of 9 items rated on a 7-point, Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). This scale assesses three dimensions of work engagement: vigor (e.g., “When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work”), dedication (e.g., “I am enthusiastic about my job”), and absorption (e.g., “When I am working, I forget everything around me”). As these three subdimensions are highly correlated, the authors suggest that rather than computing three different scores, the total score, reflecting overall work engagement, can be used. As in previous studies, we used overall work engagement in this way (Xanthopoulou et al., 2013). A well-validated Spanish version of the scale was used (Salanova et al., 2000). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for the total score was .91. Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (Wong & Law, 2002). This scale contains 16 items with responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), evaluating four dimensions of self-reported EI ability: self-emotion appraisal, other-emotion appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. Examples are “I have good control of my own emotions” or “I really understand what I feel.” However, as in previous studies, we combined the subscales into a global EI measure, as we were more interested in overall EI (Wong & Law, 2002). We used the Spanish version of this scale, which has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Extremera et al., 2019). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .91 for the total EI score. Occupational Withdrawal Intentions Scale (Hackett et al., 2001). The 3-item version of this instrument was used to assess intentions to quit teaching (e.g., “I think about quitting the teaching profession”), with responses ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 9 (agree strongly) (Klassen & Chiu, 2011). The instrument was professionally translated from English into Spanish using the back-translation method. This scale has shown adequate internal consistency with Spanish samples (Mérida-López & Extremera, 2020). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .91. Plan of Analysis The analysis was conducted with SPSS 24.0 software. Preliminary analysis consisted of descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations to examine the associations among variables. Thus, SPSS macro PROCESS 3.3 (Hayes, 2017) was used to examine the proposed associations regarding the moderated-mediation model displayed in Figure 1. This procedure allows researchers to examine conditional process models using a bootstrap method based on 5,000 resamples of the data, which produces 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to test the significance of estimated effects. Finally, in order to determine the effect size of the interaction terms, we calculated effect size statistics (f2) to determine the unique variance explained by the interaction term (Aguinis et al., 2005). We followed Kenny’s (2016) criteria to determine whether the interaction products accounted for small (f2 = .005), medium (f2 = .01) and large effects (f2 = .025). Table 1 Descriptive Results Separately for Males and Females   Note. N = 1,297; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.; M/F = males/females. Correlations above the diagonal are for males (n = 456). Correlations below the diagonal are for females (n = 841). *p < .05, **p < .01. Table 2 Descriptive Statistics for the Total Sample and Separately by Teaching Level   Note. M = mean; SD = standard deviation. Sixteen participants did not report their teaching level. To test our hypotheses, we first used Model 4 of SPSS macro PROCESS to examine the mediator role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace social support (i.e., support from colleagues and support from supervisors) and intention to quit. Furthermore, we tested the moderator role of EI in previously established mediator model by means of SPSS macro PROCESS (Model 58). This method estimates parameters for two regression models to obtain bootstrapped confidence intervals for the mediation model at different levels of EI. In these analyses, gender, age, teaching level, and teaching experience were covaried. Teachers’ gender was coded as a dummy variable (male = 0 and female = 1). Descriptive Analyses Descriptive analyses were conducted to examine potential cofounding effects of relevant sociodemographic variables (i.e., gender and teaching level) on intention to quit. Table 1 shows results of the comparisons between scores by gender. Considering gender differences, this variable was included in main analyses as a covariate. Regarding the total sample, means were low in intent to quit, moderate in workplace social support dimensions (i.e., support from colleagues and support from supervisors), and moderate-high in work engagement and EI. Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for the total sample and separately by teaching level (i.e., preschool, primary and secondary education). One-way analyses of variance with Scheffe’s post hoc tests were conducted to examine potential differences by teaching level in main study variables. For work engagement, EI, and intention to quit there was a significant difference between preschool teachers and secondary teachers (p < .01) as well as between primary and secondary teachers (p < .01). Considering differences by teaching level, this variable was included in main analyses as a covariate. Regarding Pearson correlations, analyses were conducted for both the total sample and separately by teaching level (i.e., subscript 1 = total sample; subscript 2 = preschool subsample; subscript 3 = primary subsample; subscript 4 = secondary subsample). Support from colleagues was positively related to engagement (r1 = .21, p < .01; r2 = .19, p < .05; r3 = .25, p < .01; r4 = .17, p < .01) and negatively linked to intention to quit (r1 = -.12, p < .01; r2 = -.08, p = .26; r3 = -.16, p < .01; r4 = -.09, p < .05). Likewise, support from supervisors was positively associated with engagement (r1 = .23, p < .01; r2 = .21, p < .01; r3 = .23, p < .01; r4 = .23, p < .01) and negatively related with intention to quit (r1 = -.11, p < .01; r2 = .01, p = .93; r3 = -.09, p = .06; r4 = -.13, p < .01). Results showed EI to be positively associated with support from colleagues (r1 = .12, p < .01; r2 = .25, p < .01; r3 = .09, p < .05; r4 = .08, p < .05), support from supervisors (r1 = .19, p < .01; r2 = .51, p < .01; r3 = .09, p = .05; r4 = .15, p < .01) and work engagement (r1 = .40, p < .01; r2 = .29, p < .01; r3 = .31, p < .01; r4 = .44, p < .01). There was a negative association between EI and intention to quit (r1 = -.20, p < .01; r2 = -.15, p = .05; r3 = -.17, p < .01; r4 = -.21, p < .01). Finally, work engagement was negatively associated with intention to quit (r1 = -.37, p < .01; r2 = -.21, p < .01; r3 = -.25, p < .01; r4 = -.41, p < .01). Testing for Mediation Effect with Support from Colleagues as Predictor Regarding H1a, it was proposed that work engagement would mediate the relationship between support from colleagues and intention to quit. The results showed that support from colleagues was positively associated with engagement (β = .18, p < .001), which in turn was negatively related to intention to quit (β = -.56, p < .001). The residual direct effect of support from colleagues on intention to quit became insignificant (β = -.08, p = .09), indicating that work engagement totally mediated the relationship between support from colleagues and intention to quit (indirect effect = -.10, 95% CI [-.15, -.07]). No significant effects of any of the covariates were found to explain intention to quit. The final model explained 14% of the variance. Thus, results supported H1a. Testing for Moderated Mediation with Support from Colleagues as Predictor With respect to H1b, EI was expected to moderate the indirect relationship between support from colleagues and intention to quit through work engagement. These results are displayed in Table 3. Table 3 Coefficients for the Tested Moderated Mediation Model with Support from Colleagues as Predictor   Note. SE = standard error; 95% CI = confidence interval with lower and upper limits. EI = emotional intelligence. ***p < .001. As shown, gender, age, teaching level, teaching experience, support from colleagues and EI predicted work engagement. Additionally, EI moderated the association between support from colleagues and work engagement (interaction term: B = -0.19, p < .001, 95% CI [-.26, -.13]). The interaction term accounted for a medium (f2 = .02) amount of unique variance in work engagement, after partialling out the variance accounted for by covariates, support from colleagues, and EI (ΔR2 = .02, F = 35.14, p < .001). Regarding the prediction of intention to quit, the results showed no significant effects of the covariates. Although neither support from colleagues nor EI predicted the intention to quit, work engagement was a significant predictor. The results showed that EI moderated the association between work engagement and intention to quit (interaction term: B = 0.20, p < .001, 95% CI [.11, .30]). The interaction term explained a medium (f2 = .012) amount of additional variance in intention to quit beyond the main effects of covariates, support from colleagues, work engagement and EI (ΔR2 = .012, F = 17.69, p < .001). Thus, results supported H1b. The significant moderated mediation model was further tested by analyzing the indirect effect of support from colleagues on intention to quit at different levels of EI. Following standard procedures (Hayes, 2017), EI was divided into categories of low (the mean minus 1 SD), and high (the mean plus 1 SD). The interaction of support from colleagues and EI on work engagement is displayed in Figure 2. As is illustrated, the relationship between support from colleagues and work engagement weakened as EI increased. For those teachers reporting high EI, higher support from colleagues was not related to higher work engagement (β = .02, p = .48). By contrast, the relationship between support from colleagues and work engagement was positive at low levels of EI (β = .30, p < .001). Post hoc analysis showed there was a significant difference between the slopes (t = 5.67, p < .001). Figure 2 Relationship of Support from Colleagues and EI for Predicting Work Engagement. EI = emotional intelligence.   ***p < .001. Figure 3 illustrates the moderating effect of EI in the relationship between work engagement and intention to quit. As shown, this relationship weakened as EI increased. For those teachers with a low EI, higher work engagement was associated with a lower intention to quit (β = -.58, p < .001), whereas this association became less intense at high EI levels (β = -.29, p < .001). Post hoc analysis revealed a statistical difference between the slopes (t = 3.35, p < .001). Figure 3 Relationship of Work Engagement and EI for Predicting Intention to Quit. EI = emotional intelligence.   ***p < .001. Testing for Mediation Effect with Support from Supervisors as Predictor Regarding H2a, it was proposed that work engagement would mediate the relationship between support from supervisors and intention to quit. The results showed that support from supervisors was positively associated with engagement (β = .19, p < .001), which in turn was negatively related to intention to quit (β = -.56, p < .001). Results showed the residual direct effect of support from supervisors on intention to quit to be insignificant (β = -.05, p = .21), indicating that work engagement totally mediated the association between support from supervisors and intention to quit (indirect effect = -.11, 95% CI [-.15, -.07]). The final model explained 14% of the total effect of support from supervisors on intention to quit. Thus, H2a was supported. Testing for Moderated Mediation with Support from Supervisors as Predictor With regards to H2b, it was expected that EI may function as a moderator in the direct and/or indirect effect between support from supervisors and intention to quit. Results are displayed in Table 4. Table 4 Coefficients for the Tested Moderated Mediation Model with Support from Supervisors as Predictor   Note. SE = standard error; 95% CI = Confidence Interval with lower and upper limits. EI = emotional intelligence. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Gender, age, teaching level, teaching experience, support from supervisors and EI predicted work engagement. Furthermore, EI did moderate the relationship between support from supervisors and work engagement (interaction term: B = -0.10, p < .01, 95% CI [-.16, -.04]). The interaction term accounted for a medium (f2 = .006) amount of unique variance in work engagement beyond the variance accounted for by covariates, support from supervisors, and EI (ΔR2 = .006, F = 9.63, p < .01). Regarding intention to quit, solely gender and work engagement were significant predictors. Although EI did not predict intention to quit, it did moderate the association between work engagement and intention to quit (interaction term: B = 0.21, p < .001, 95% CI [.11, .30]). This product accounted for a medium (f2 = .012) amount of unique variance in intention to quit beyond the main effects of covariates, support from supervisors, work engagement, and EI (ΔR2 = .012, F = 18.22, p < .001). Thus, results supported H2b. Figure 4 illustrates the interaction effect of support from supervisors and EI on work engagement. While higher support from supervisors was related to higher work engagement for those teachers with a low EI (β = .21, p < .001), this relationship weakened as EI increased. For high-EI teachers, the association between support from supervisors and work engagement decreased, but remained significant (β = .07, p < .05). Post hoc analysis showed there was a significant difference between the slopes (t = 3.02, p < .05). Figure 4 Relationship of Support from Supervisors and EI for Predicting Work Engagement. EI = emotional intelligence.   *p < .05, ***p < .001. Finally – as demonstrated in Figure 5 – the relationship between work engagement and intention to quit weakened as EI increased. For those teachers with a low EI, higher work engagement was associated with a lower intention to quit (β = -.59, p < .001). However, at high EI levels, this association became less intense (β = -.29, p < .001). Post hoc analysis revealed that the slopes were statistically different (t = 3.36, p < .001). Figure 5 Relationship of Work Engagement and EI for Predicting Intention to Quit. EI = emotional intelligence.   ***p < .001. This research aimed to assess whether work engagement mediates the relationship between workplace social support (i.e., support from colleagues and support from supervisors) and intention to quit, as well as to evaluate the moderating role of EI on the indirect effect of workplace social support dimensions on intention to quit. Prior studies have tested these factors independently. However, the current study is the first to integrate these organizational and personal factors as antecedents of teachers’ work engagement and intention to quit. Regarding the mediator role of work engagement in the relationship between workplace social support and intention to quit (H1A and H2A), the results showed significant associations between support from colleagues and supervisors with teacher engagement and intention to quit. These findings are in line with prior research suggesting the influence of these work characteristics on teachers’ motivation and decisions about leaving their profession (Geiger & Pivovarova, 2018; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018). Indeed, study hypotheses were confirmed, suggesting that the perception of supportive relations with colleagues and supervisors was significantly associated with work engagement, which, in turn, was linked with lower withdrawal intention. This finding indicated the indirect effect of working conditions on teacher attrition through work engagement, which is consistent with the motivational process of JD-R theory. This result has prior empirical support with teacher samples (You & Conley, 2015). With respect to the proposition that EI would moderate the indirect pathways between workplace social support and intention to quit through work engagement (H1b and H2b), the findings corroborated the proposed hypotheses. These data are in line with the moderator model of EI (Côté, 2014) and accord with prior research testing the interaction of EI dimensions with contextual factors to predict well-being (Newton et al., 2016). Specifically, results showed that teachers with the lowest levels of engagement were those reporting low support from colleagues or supervisors, together with low EI levels. By contrast, teachers reporting the highest levels of work engagement were those who reported higher workplace social support and higher EI. Results did not point to additive but to compensatory effects of EI for predicting work engagement (Côté & Miners, 2006). For those teachers with high EI levels, support from colleagues did not associate with work engagement. By contrast, support from supervisors did still relate with higher work engagement among those high-EI teachers. This finding may suggest that EI and workplace social support dimensions are associated with work engagement in distinctive ways. It is shown that workers’ abilities to perceive and understand how they and others feel lead to the establishment of healthier and more positive relationships (Côté, 2014). In fact, EI is associated with greater quantitative and qualitative support and so this personal resource predicts teachers’ personal well-being (Rey & Extremera, 2011). Findings revealed that teachers’ EI may make a difference regarding the effects of colleagues’ support on work engagement, whereas EI exerted a relatively less intense influence in the supervisors’ support-work engagement relationship. This suggests that there may be other salient predictors of teacher engagement when considering support from supervisors beyond differences in EI levels. For instance, principals may provide support for autonomy (Collie et al., 2017) and so this job resource would facilitate greater work engagement even among those teachers reporting high EI. Considering these findings, there is a need for future in-depth comparison of both forms of support and their interactive effects with teachers’ EI in order to predicting motivation and retention indicators. Results confirmed that the highest levels of intention to quit were found among those teachers with low work engagement and low EI levels. The finding that EI may contribute to the prediction of decreased intention to quit among teachers reporting low engagement is in line with prior research relating teachers’ personal characteristics to retention (Hong, 2012; Tait, 2008). For instance, when teachers feel exhausted at work and give limited effort, it is conceivable that they perceive their workplace as negative and threatening (Thoresen et al., 2003). This may explain why they may experience a greater desire to leave than their engaged counterparts. Whether teachers might continue with their career or decide to quit their profession may depend on whether their perceptions of their work as disengaging and the negative emotions associated with those perceptions are adequately managed or not. These results suggest EI should be considered in relation to the implications of mood at work on intention to quit (Ashkanasy & Dorris, 2017). Regarding theoretical implications of the study, these findings are informative for occupational psychology and teacher education literature as they yielded new information on how a psychological resource, such as teachers’ EI, would influence associations between job resources, work motivation, and intention to quit teaching profession. This work expands current knowledge on personal resources applying the JD-R theory in educational settings (Taris et al., 2017). Together, these findings provide support for emerging prior research advocating for the joint examination of positive organizational and personal factors as significant predictors of teachers’ work-related well-being and work criteria (McInerney et al., 2018). Although earlier research has shown that workplace factors are key predictors of teachers’ intentions to quit, it seems important to consider whether teachers perceive themselves as emotionally competent. Taken together, these results may serve as a starting point for the development of practical strategies aiming at increasing teacher work motivation and eventually reducing teachers’ withdrawal intentions. A fruitful avenue for reducing teachers’ intention to quit would be to adopt individual-organizational interface programs (Randall & Travers, 2017). These preliminary findings suggest educational administrators and researchers should pay attention to EI levels when designing programs to promote teachers’ work motivation and commitment. For instance, interventions providing structured time for collaborative efforts and creating roles for teachers to guide professional development may lead teachers to feel that they are part of a supportive environment and thus influence their commitment (Collie et al., 2017). School administrators should provide newly-qualified teachers with a supportive environment during their teacher education preparation, as the promotion of a rich environment with collaborative relationships among coworkers may lead to the enactment of feelings of belonging and pride and may relate to a higher confidence in the resolution of daily challenges. Such an approach seems worthwhile as it may lead to higher retention rates among teachers in their early professional stages (Ingersoll et al., 2014). Likewise, it is critical to improve the perception of support from principals and administrators as they influence teachers’ perceptions of barriers within their occupational context (Geiger & Pivovarova, 2018). Recent findings show that EI training may contribute to teachers’ occupational health and well-being (Schoeps et al., 2019). These results together with current findings underline the value of designing future psychosocial interventions focusing on teachers’ perceptions of their skills for dealing with their own and other peoples’ (e.g., colleagues, families, or students) emotions to improve their work engagement and to facilitate greater desires to remain in teaching (Castillo-Gualda et al., 2017; Yin et al., 2013). Although further research is needed, these findings suggest that the increase in social resources at work should consider baseline levels of teachers’ personal resources such as EI. This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future lines of research. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data makes it difficult to establish the direction of the relationships among variables. Although our data are grounded in theory and relied on a relatively large sample of teaching professionals, replicating these findings with longitudinal studies would provide further insights into the contribution of EI and job resources to work engagement and intention to quit. Second, the use of a self-report EI questionnaire may potentially be related to social desirability (Conway & Lance, 2010). Previous research has confirmed that self-reported and EI ability tests may differ in their predictive validity with respect to work outcomes (Miao et al., 2017). Future studies should therefore combine self-reporting measures with EI performance tests (Mayer et al., 2016), or even consider new proposals adapted to the organizational context, such as the Mobile Emotional Intelligence Test (Sanchez-Gomez & Breso, 2019). Moreover, it would be fruitful to pay attention to other variables that may be related to intention to quit, as we solely focused on the motivational process of JD-R theory. Although we provided novel evidence on positive work and individual aspects explaining work engagement and intention to quit in the teaching profession, it would be worthwhile to study the role of EI in relation to other elements of JD-R theory. For instance, future research should assess whether EI dimensions might attenuate the effects of interpersonal job demands (e.g., classroom disturbances) on intent to quit through job burnout. This approach would benefit current knowledge on the role of teachers’ EI regarding the health impairment process (Taris et al., 2017). Furthermore, integrative models testing the role of individual resources regarding both positive (i.e., resources) and negative (i.e., demands) teaching-related job aspects would increase our knowledge on how teacher engagement and teacher burnout are related to predicting commitment (McInerney et al., 2015; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2018). Future studies could also examine the influence of EI for developing positive interpersonal relationships between educators and families (Martínez-González et al., 2016) and it would be worthwhile replicating this research and taking into consideration personality traits, as they may explain levels of work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). This field of research would also benefit from examining whether certain sociodemographic factors, such as gender, teaching level, or teaching experience (Borman & Dowling, 2008; Høigaard et al., 2012) affect relationships among variables. Future studies are needed to replicate the patterns of descriptive results found in this study so it can be confirmed whether female teachers at secondary levels are at a greater risk of deciding to withdraw. Likewise, as previous studies have reported differences between early-career teachers (i.e., first five years of teaching) and experienced teachers in terms of attrition rates, this approach merits further attention (Guarino et al., 2006). Finally, there is a limitation regarding the sampling method used. This research included workers recruited by student-recruited sampling, which is a non-random sampling technique with potential limitations. Although this technique has shown validity and reliability, as well as usefulness in field studies within organizational psychology (Wheeler et al., 2014), this sampling method may be more biased toward more cooperative participants, thereby limiting generalizability of results. In conclusion, these results highlight the interactive role of job and personal resources as predictors of teachers’ work engagement and associated intent to quit teaching. These novel findings suggest the need for implementing psychosocial intervention programs to promote EI and organizational support as valuable means for increasing teachers’ work motivation and thus facilitate decisions about staying in their occupation. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Mérida-López, S., Sánchez-Gómez, M., & Extremera, N. (2020). Leaving the teaching profession: Examining the role of social support, engagement and emotional intelligence in teachers’ intentions to quit. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(3), 141-151. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a10 Funding: This work was supported by Junta de Andalucia/FEDER funds (UMA18-FEDERJA-147) and the Spanish Ministry of Education and Vocational Training (FPU16/02238). |

Cite this article as: Mérida-López, S., Sánchez-Gómez, M., & Extremera, N. (2020). Leaving the Teaching Profession: Examining the Role of Social Support, Engagement and Emotional Intelligence in TeachersŌĆÖ Intentions to Quit. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(3), 141 - 151. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a10

nextremera@uma.es Correspondence: nextremera@uma.es (N. Extremera).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS