Care Competencies Training Enhances AdolescentsŌĆÖ Well-being: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Cat-Tuong Phuoc Nguyen1, Wim Beyers2, Martin Valcke2, and Hong-Van T. Dinh1

1Department of Psychology and Education, University of Education, Hue University, Vietnam; 2Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Department of Developmental, Personality and Social Psychology, Ghent University, Belgium

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a10

Received 8 October 2023, Accepted 6 March 2024

Abstract

Objective: This intervention study seeks to assess the impact of a care competencies training program on students’ well-being. Method: This randomized controlled trial involved 191 Vietnamese adolescents (65.4% female, Mage = 16 years and 8 months) in a 7-week intervention study that used video vignettes to build their care competencies. Validated scales were used to determine their care competencies (Care Competencies Questionnaire for Adolescents) and well-being (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, Perceived Stress Scale and Satisfaction with Life Scale) at three points in time: before, immediately after, and two months after the intervention. The full-information maximum likelihood approach was applied to latent growth curve modeling (LGM) in Mplus 8.5 to estimate the initial level (i.e., intercept) and the change (i.e., slope) in care competencies and well-being among adolescents over time. Factor scores of LGMs were saved for correlation and multiple linear regression analysis by using SPSS (version 26.0) to explore the relationships between the changes in care competencies/failures and the changes in well-being. Results: Results showed that, next to a significant increase in care competencies and a significant decrease in care failures, other well-being variables also significantly changed in the intervention group. In the intervention group, but not in the control group, changes in care competencies and failures consistently and significantly predicted changes in well-being. Conclusion: The results support the potential of the video vignette-based intervention to promote the development of adolescents’ care competencies.

Keywords

Mother-child interactions, Parenting programs, Preventive interventions, Home-visiting programsCite this article as: Nguyen, C. P., Beyers, W., Valcke, M., & Dinh, H. T. (2024). Care Competencies Training Enhances AdolescentsŌĆÖ Well-being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(3), 147 - 169. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a10

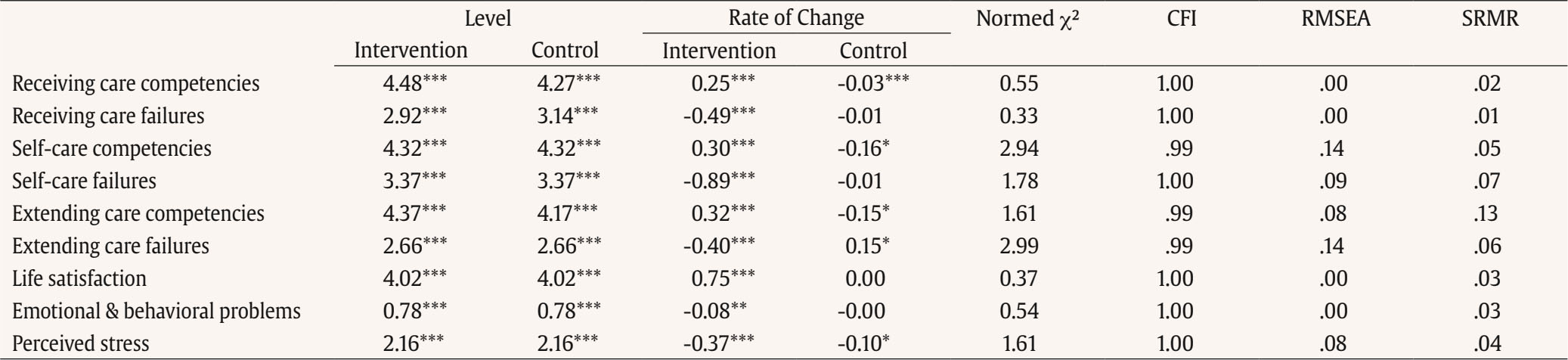

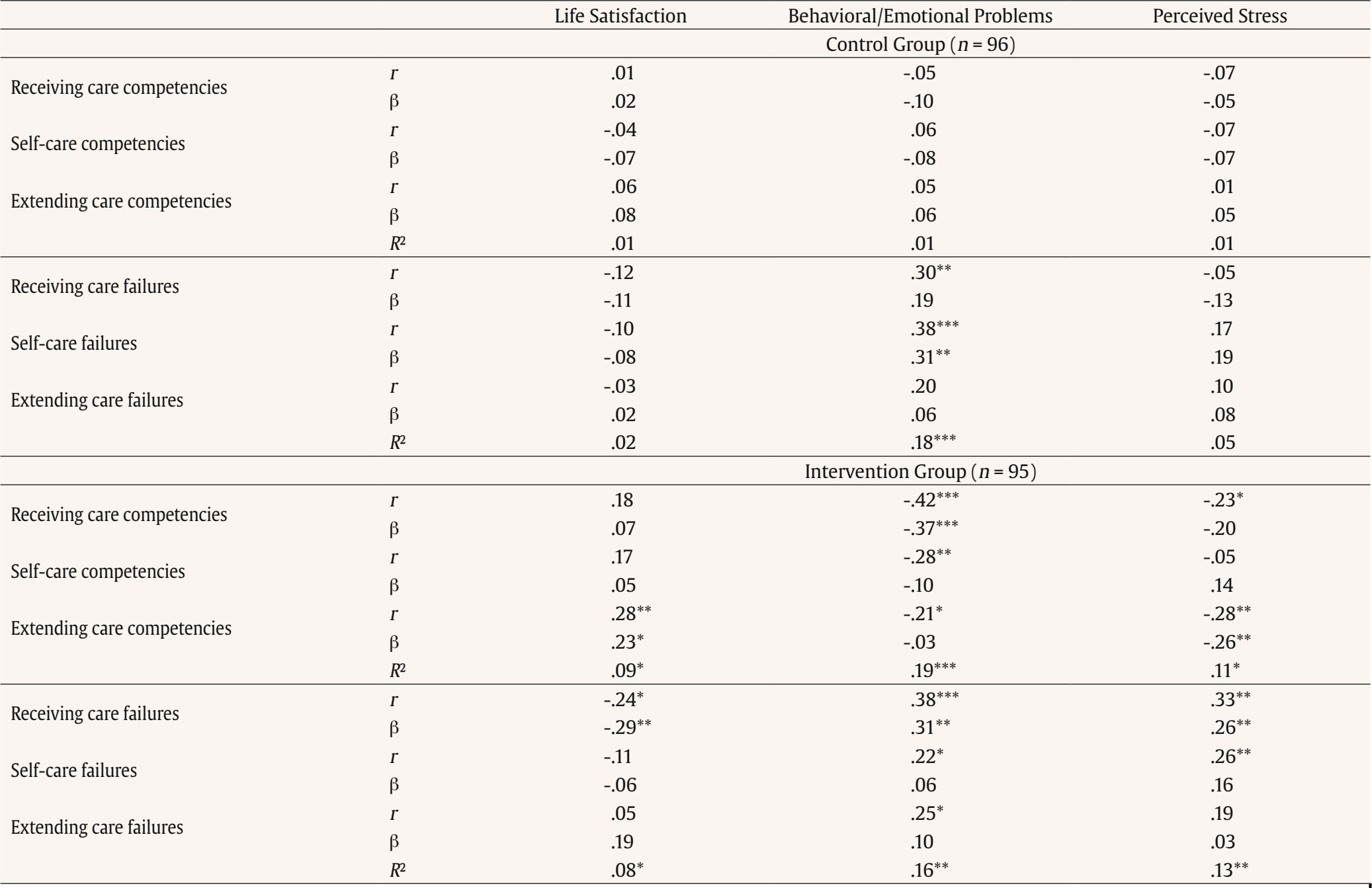

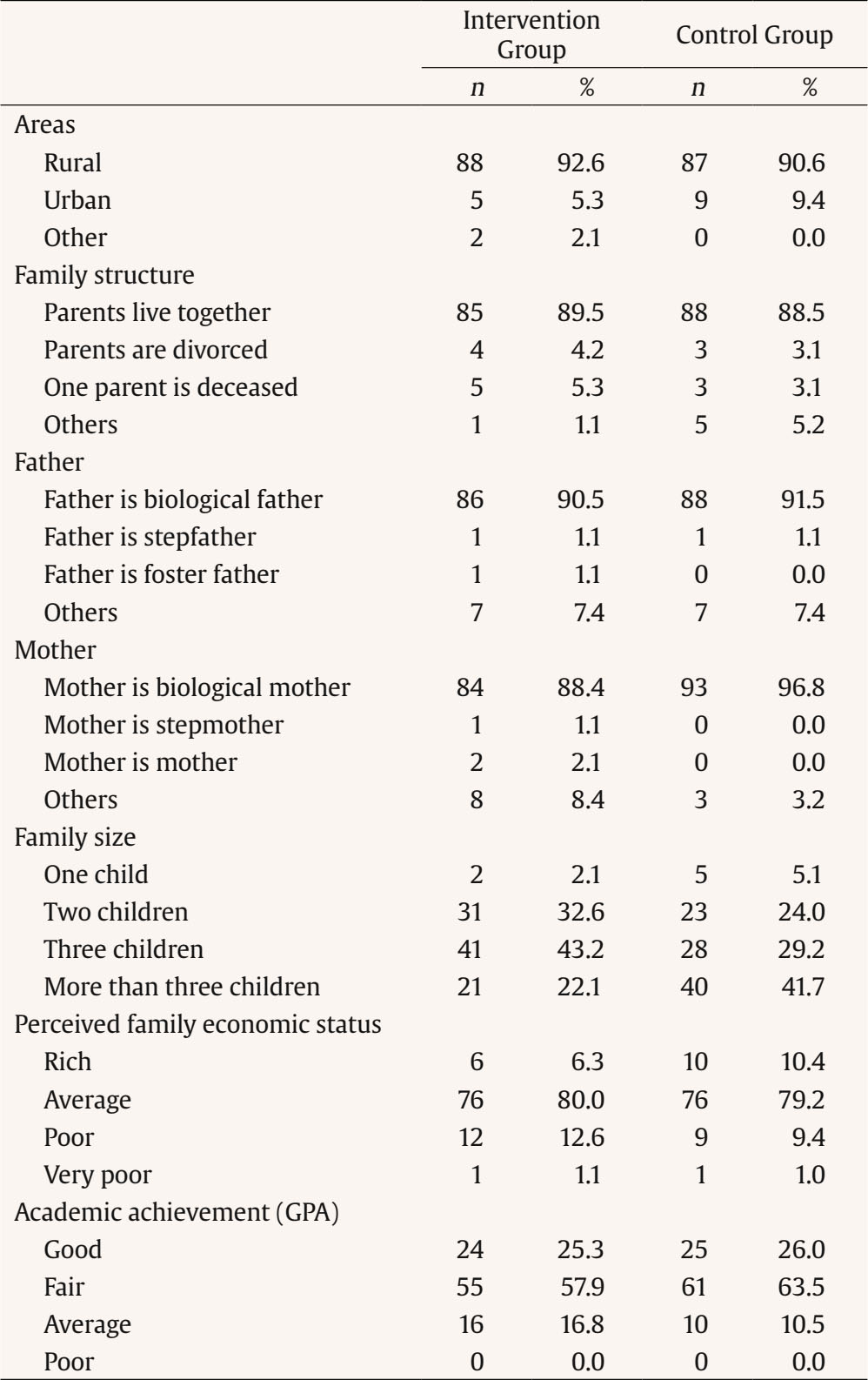

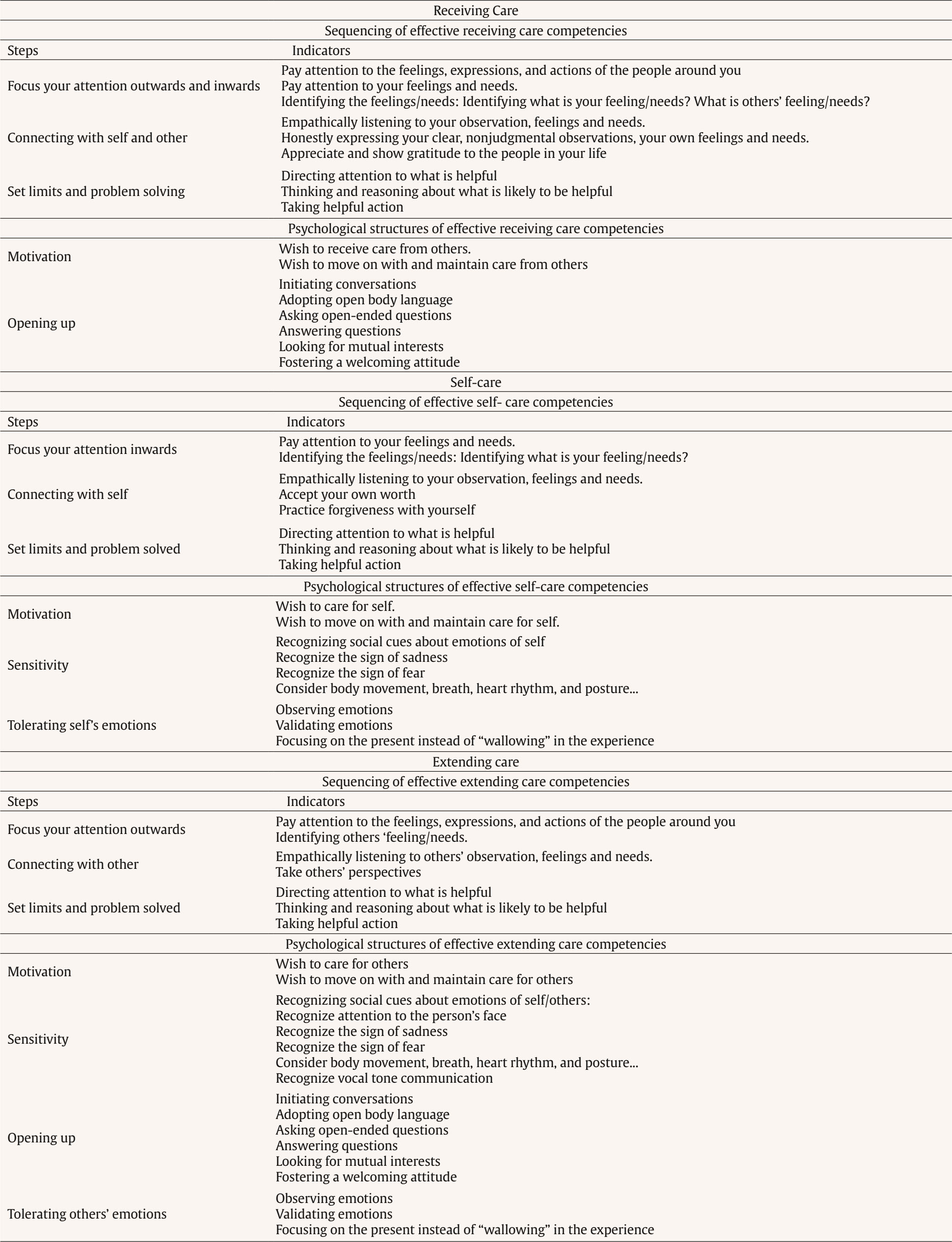

Correspondence: npctuong@hueuni.edu.vn (C-T. P. Nguyen).It has become increasingly common for children and adolescents worldwide to experience mental health issues. According to studies conducted by Choi (2018), the Children’s Society (2023), and Voss et al. (2023), this trend is on the rise. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2021, 2023) has revealed that around one in every seven individuals aged between 10 to 19 years old suffers from a mental disorder, accounting for 13% of the global burden of disease in this age group. Looking at adolescents in school contexts, Parviainen et al. (2020) state that 20% of adolescents in school experience ill-being, while Panchal et al. (2021) find that 63% of students manage depression symptoms. Very recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, associated with confinement and social isolation, seems to have impacted the course of many mental disorders in children and adolescents. Much of the existing evidence shows adolescents and children significantly experienced high rates of ill-being during and after a pandemic (Mansfield et al., 2022; Meherali et al., 2021). Children under 18 years of age have experienced a 24% increase compared to the pre-pandemic period in depression, anxiety, and insomnia (Chi, 2020; Leeb et al., 2020). At least 13% of 10- to 19-year-olds were diagnosed with a mental health disorder during the pandemic (UNICEF, 2021). The fact that these mental conditions remain largely underdiagnosed and undertreated might lead to negative psychological outcomes in adulthood (WHO, 2021, 2023). While there are many factors significantly affecting well-being in adolescents, empirical evidence suggests that providing adolescents with emotional and mental tools to build up good social connectedness, and cultivate inner strengths (e.g., sociability, resilience, self-awareness, integrity, resourcefulness, and empathy) are known as the most important strategies. This introduces our focus on developing adolescents’ care competencies. The feeling of being supported, cared for, accepted, and deeply connected to others seems to help adolescents (Van Ryzin et al., 2007). Commitment to recognize and appreciate others’ feelings and needs, to help others, is reported to contribute to the well-being of adolescents (Administration for Children & Families [ACF, 2012]). Furthermore, self-care practices help adolescents feel well and cope with stress without having to avoid or suppress it (ACF, 2012; Public Health England [PHE, 2014]). Overall, adolescents’ well-being depends on the quality and quantity of care they can receive from others, develop for themselves, and extend to those around them (Mind and Life Institute [MLI, 2014a]). The field of care has made significant progress in understanding the role of care competencies in promoting individuals’ well-being (MLI, 2014a). Available empirical evidence shows how well-developed care competencies (receiving care, developing self-care, and extending care) are related to well-being benefits. Research points to a decrease in negative affect, perceived stress, anxiety, and depression, and an increase in happiness, positive affect, and life satisfaction (e.g., Cosley et al., 2010; Gülaçtı, 2010; Jenkinson et al., 2013; Moses et al., 2016; Murphey et al., 2013; Myers et al., 2012; Nguyen et al., 2020). Accordingly, in some countries the integration of care-based curriculum programs promotes students’ positive emotions and behavior through direct teaching of self-awareness, self-management, responsibility, empathy, and cooperation, creating settings where students feel heard, known, and cared for. These programs are believed to work as potential prevention to enhance students’ mental health, e.g., the Caring School Community Program (CSC), formerly known as the Child Development Project (CDP) in the USA (Center for the Collaborative Classroom, 2016), the Social Skills Improvement System Classwide Intervention Program (Elliot & Gresham, 2008), the Caring and Safe Schools (CSS) in Canada (Canada Ministry of Education, 2010), and the Happy School Projects (HSP) in Asia and Pacific Region (UNESCO, 2016) and in Vietnam (Eurasia Learning Foundation and Association, n.d.). In line with the general global context, a significant minority of Vietnamese adolescents suffer from anxiety disorders, depression, and other mood disorders, behavior problems, and drug and alcohol addiction (UNICEF, 2023). Four hundred two children were surveyed, and up to 21.7% of them had mental disorders; one in five adolescents in Vietnam has mental health problems and needs to use mental health services (UNICEF, 2023). However, only about 8.4 % of them receive the necessary medical support and treatment from professionals (UNICEF, 2023). Along with this, empirical data from previous studies also reveal that Vietnamese adolescents suffer limitations in their receiving care (Duong et al., 2007; Nguyen & Dinh, 2012), self-care (Dinh et al., 2013; Pham et al., 2021), and extending care (Do, 2014; Phan, 2016). Nationwide, there is an increasing concern for the well-being of adolescents (Dinh et al., 2020), not only concerning how it may impact their academic achievement, and engagement with school and psychological resilience but also at the policy level, examining whether and how education systems prioritize student well-being. However, the work of promoting well-being in Vietnamese adolescents has encountered many challenges, such as poor public awareness and a lack of professional services, facilities, medication, and tools (UNICEF, 2018). More importantly, mental health issues are still seen only as the responsibility of the medical health sector. As a consequence, current mental health programs in Vietnam tend to focus only on clinical and medical aspects, rather than on early detection and prevention efforts and on participation with other sectors, especially the participation of schools (UNICEF, 2018). Social and educational policymakers should therefore pay particular attention to preventive and remedial school-based interventions (UNICEF, 2023). Theoretically and practically, promoting Vietnamese adolescents’ well-being by implementing preventive care-based intervention programs could be a feasible approach. However, teaching care is a complex process that should be based on up-to-date theory, research, tools, and skills (MLI, 2014a, 2014b). “When students care, they must employ reasoning to decide what to do and how best to do it” (Noddings, 1984, p. 14). More reflections should be made to fill the gaps in previous intervention studies to build up a more effective one. First, evaluation studies of most care-based projects are hardly documented, and inconsistent findings and limited methodological analysis among documented research were found. Some evaluation studies of the Caring School Community program, the Social Skills Improvement System Classwide Intervention Program, and the Happy Schools Project in Vietnam have been officially published. The Caring School Community program, offered by the Collaborative Classroom, has been implemented in K-8 schools across various districts in the United States. Research from the Caring School Community program underpins its effectiveness in promoting social-emotional skills (Battistich et al., 1997; Center for the Collaborative Classroom, 2016; Chang, 2008; Watson & Battistich, 2006; Watson et al., 2019). Critical ingredients of the Caring School Community program seem to be: direct instruction set up during regular class meetings, integration of care themes into the subject matter, creating a caring climate and extracurricular activities, a focus on experiential learning opportunities such as mindfulness training, journaling, role-play/drama, and game playing. The Caring School Community program seems to provide students with ‘tools’ to improve prosocial behavior, cooperation, their commitment to being fair, empathic, respectful, and responsible (Center for the Collaborative Classroom, 2016; Watson et al., 2019. The evaluative research also provides evidence about the causal relationship between the promotion of care-based skills and the decrease in problem behavior, such as violence, bullying, delinquency, and drug use, and reduced emotional problems, such as depression or stress disorders (Durlak, 2011; Sklad et al., 2012). The Social Skills Improvement System Classwide Intervention Program, offered by SSIS CoLab, focuses on some care-based skills (e.g., self-awareness, self-management, social awareness) from preschool to early adolescence and is applied in many schools in the US and demonstrates evidence of effectiveness in grades 1-2 in terms of internalizing behaviors and empathy (DiPerna et al., 2015, 2018). A recently conducted evaluation study of the Happy Schools pilot project in nine schools located in the Thua Thien Hue Province of Vietnam between 2018 and 2021 has revealed that providing adolescent students with training in specific workshops related to care for others (i.e., empathetic listening, empathy), care for self (i.e., emotional awareness), and caring for nature can help reduce emotional and behavioral issues while promoting overall life satisfaction. The study primarily relied on mini-quantitative research conducted by teachers and students of the participating high schools, as reviewed by Tran et al (2023). However, Debra (2011) also evaluated the effectiveness of the Caring School Community in two primary schools in the US, but found that it had no statistically significant impact on student attendance, discipline, positive behavior referrals, or academic achievement two years after implementation. Similarly, Diperna et al. (2015) also found that the Social Skills Improvement System Classwide Intervention Program did not have a significant impact on variables such as social skills and externalizing problem behaviour of preschoolers. Primary explanations for these non-significant results are found in the short duration of the intervention, the lack of teacher professional development, the lack of leadership opportunities for teachers or administrative support, and a lack of active participation. Besides, previous care-oriented intervention studies rather adopted traditional mean-difference-comparisons methods (i.e., repeated-measures ANOVA; Debra, 2011; paired t-test; Battistich et al., 1997; Tran et al., 2023), which may produce less reliable and precise findings. These methods solely focus on group means for each measurement point and thus ignore variability in the rate of change at the individual level (Hess, 2000). Further, these approaches are vulnerable to effects resulting from missing values, inequivalent time points between subjects, and violations of sphericity, factors which can lead to sampling bias and inflated levels of type I error (Gueorguieva & Krystal, 2004). In order to overcome some of these limitations, methods known as latent growth models (LGM) are being adopted to assess evolving processes across a variety of behavioral domains by modeling both inter- and intra-individual variability in terms of initial levels and consecutive developmental steps (T. E. Duncan et al., 1994). Taking all these issues into account, additional well-designed research is needed to verify the causal relationship between care-based interventions and the enhancement of adolescent well-being. Second, researchers believe that care can be taught if it can be properly defined, specified, and broken down into its elements (Griffiths et al., 2012; McNamee & Mercurio, 2007). A holistic, all-inclusive definition of care is shaped by Nguyen et al. (2020). Accordingly, ‘care’ is a complex concept, reflecting cognitive, affective, and behavioral facets: (1) being aware of and apprehending a person’s current situations or needs (cognitive); (2) responding emotionally to those situations or needs or experience sympathetic or empathetic feelings with that person (affective); and (3) acting to meet the needs of an individual (behavioral). Next to being multi-faceted, care is also multi-dimensional in nature because it interlinks the ‘receiving care’, ‘self-care’, and ‘extending care’ dimension (Nguyen et al., 2020). Receiving care can be seen as (1) being aware and receptive to the others’ notice to one’s own needs (cognitive); (2) being receptive to others’ empathetic feelings to one’s own needs (affective); and (3) being receptive to others’ actions to meet one’s own needs (behavioral). Self-care is regarded as (1) noticing and understanding the needs of oneself (cognitive); (2) empathetically reacting and accepting the needs of oneself (affective); and (3) acting to meet one’s own needs (behavioral). Extending care can be described as (1) noticing and understanding others’ needs (cognitive); (2) experiencing positive emotional reactions to others’ needs (affective); (3) and acting to meet others’ needs (behavioral) (Nguyen et al., 2020). Among these dimensions, receiving care from others is considered the foundation to extend care to others and to develop self-care (MLI, 2014b). Nevertheless, previous studies confirm the empowering role of receiving care, self-care, and extending care competency on adolescents’ well-being, showing that adolescents with higher received support, self-compassion, and empathy experienced higher levels of life satisfaction, positive affect, and lower levels of perceived stress, anxiety, and depression (e.g., Moses, et al., 2016; Murphey et al., 2013; adolescents with higher extending care competencies but lacking receiving care competencies experienced the most stress (Nguyen et al., 2020). Accordingly, training adolescents to develop simultaneously receiving care, self-care, and extending care competencies can surely promote their healthy development and positive mental health (MLI, 2014a). In another vein, according to Gilbert et al. (2017), care also evolves from two mindsets or ‘psychologies’, which encompass a multitude of caring attributes and skills. The first mindset involves the motivation and ability to notice, engage with, and make sense of the suffering of self and others. We are motivated and willing to care for others, receive care from others, and care for ourselves. We are sensitive enough to recognize the needs and emotions of others or ourselves and tolerate staying with rather than avoiding or denying emotions evoked by suffering. The second mindset of care involves the skills and wisdom to undertake actions towards preventing or alleviating the suffering of the self and others. Taking perspectives by Nguyen et al. (2020) and Gilbert et al. (2017) together, we can infer that the sequencing for effective care competencies can be composed of three steps: (1) focusing attention outwards and inwards to notice emotions and needs of self or others; (2) connecting with self and others to show empathy; and (3) setting limits and problem-solving to take helpful actions. The psychological structures for effective care competencies can include motivation with the willingness and wish to care, opening up to welcome care or extend care, sensitivity to detect others’ needs or emotions, and tolerating self and others’ emotions. After conducting thorough investigations (Nguyen et al., 2020), we found that there are no care-based intervention programs that focus on all three dimensions of care simultaneously. Moreover, even though “learning to be cared for is the first step” (Noddings, 2002, p. 24), there are hardly any intervention studies focusing on receiving care. Some care-based interventions only focus either on extending care (e.g., empathy skills; Sakofsky, 2009; Schultze-Krumbholz et al., 2015) or on self-care (e.g., mindfulness; Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2017; Bluth et al., 2015). The above-mentioned holistic perspective on care helps further explain why some care-based intervention programs are not effective. Without learning how to receive care, children have to learn to manage their emotions and behaviors (self-care) and care for others without first feeling that they are loved. The idea that one “should” or “must” care for self, for others, can cause undue stress and is often tied to feelings of inadequacy and guilt and even lead to empathy fatigue (MLI, 2014a). Similarly, the single focus on developing empathy-related skills – as observed in some intervention programs in Vietnam (e.g., Nguyen & Phuong, 2017) – may look cost-effective and easier to implement and assess than a focus on a broader range of skills. But, this might lead to unexpected outcomes of the dark side of empathy such as increasing students’ ill-being and aggressive behavior (Dinh et al., 2021; Keller & Pfattheicher, 2013). Empathy may lead children to feel overwhelmed by others’ emotions if they do not know how to manage their own emotions or feel guilty or powerless because they do not know what to do about it. Empathy is meaningful when children are also taught to be aware and in control of their impulses and emotions so they can focus on how others feel without dismissing their feelings or letting them get in the way (Dinh et al., 2021). More importantly, this deficiency in looking at the full complexity of care skills is also observed in the K-12 life skills training of the Ministry of Education and Training (2015). This program is inspired by the WHO, UNICEF, and UNESCO and is used in many schools. However, in this program, skills related to help-seeking or social support-seeking are rarely mentioned. The main focus is on competencies like expressing sentiments, building good friendships, decision-making, problem-solving, creative thinking, critical thinking, effective communication and collaboration, self-awareness, empathy, and coping with pressure. To address this gap, an intervention for adolescents’ well-being comprising three dimensions of care is necessary. Third, researchers also stress how well-being interventions should build on evidence-based approaches (Choi, 2018). In this context, we can build on recent educational research about fostering complex competency development. An example is the research strand represented by Blömeke et al. (2015). They stress how competencies are to be considered as a disposition, reflecting knowledge, skills, and attitudinal components that together help invoke behavior. But the latter depends on the deployment of situation-specific skills (i.e., perception, interpretation, and decision-making skills, or PID skills). The concept of “situation-specific” implies that learners are put in a realistic and situated setting. In this concrete setting, learners are pushed: (1) to (P)erceive particular events or identify what is important in a setting; (2) to (I)nterpret these events based on their disposition; and (3) based on (1) and (2), to make (D)ecisions about how to respond to the event. This PID approach mostly builds on video-vignettes. These are incomplete short stories that are video-recorded to reflect, in a less complex way, real-life situations in order to encourage discussions, and potential solutions to problems where multiple solutions are possible (Jeffries & Maeder, 2009). The video vignettes represent an authentic experiential event and are accompanied with open-ended questions that activate the situation-specific skills (De Coninck et al., 2018; Muñiz-Rodríguez et al., 2018). The video vignettes simulate real-life situations without putting participants at (emotional, physical, or legal) risk (Dotger et al., 2015) and have proven to be effective in fostering the reflection cycle needed to learn from practice and to apply to real-life problems (Cherrington & Loveridge, 2014; Prado et al., 2020; Siry & Martin, 2014). This approach – often referred to as clinical simulations – has successfully been applied in intervention studies to develop feedback competencies (Muñiz-Rodríguez et al., 2018), parent-teacher communication competencies (De Coninck et al., 2018), teachers’ bullying management competencies (Sung et al, 2020), or aggression-management competencies (Franco & Valcke, 2018). However, to our best knowledge, this approach has not yet been applied in interventions focusing on social-emotional competence development in adolescents. These gaps in the literature and our emphasis on the holistic nature of care inspired the design, implementation, and evaluation of an alternative approach in this study. This alternative intervention aimed at fostering all three dimensions of care in Vietnamese adolescents, based on the Perception-Interpretation-Decision approach and the support of video vignettes, using LGMs for data analysis, with the expectation this would consequently result in a higher level of well-being. We put forward the following general research question to guide our study: Do adolescents enrolled in the video-vignette-based intervention attain a higher level of care competencies and life satisfaction and mirror a lower level of care failures and psychological distress as compared to adolescents outside the intervention? The available theoretical and empirical base helps formulate the following hypotheses: Hypothesis 1: Due to the intervention, care competencies of adolescent students participating in the intervention will increase and care failures will decrease as compared to adolescents in the control group. Hypothesis 2: The intervention will enhance life satisfaction and reduce emotional and behavioral problems and perceived stress of adolescent students in the experimental group compared to adolescent students in the control group. Hypothesis 3: Increasing care competencies and decreasing care failures will predict increasing life satisfaction and decreasing emotional and behavioral problems, particularly in adolescent students in the intervention group. Participants The 11th-grade adolescent students of Phan Dang Luu High School in Hue City, Vietnam received an announcement from their head teachers and registered for participation through their monitors within one week. The inclusion criteria for this study were current school enrollment, age between 17 and 18 years, and ability to attend weekly study sessions. Exclusion criteria were hearing or seeing impairments, injuries, or physical disabilities that would hinder full participation in either intervention. Participants were blind to hypotheses regarding the role of care competencies in this study and were informed that they would be assigned to a “life skills training program” or a control condition. The size of the sample was determined based on the number needed for LGMs analysis (Cheong, 2011) and RCT studies (Sharma et al., 2020; Wang & Ji, 2020). It was suggested that a minimum of 200 participants should be included to perform this statistical analysis. However, we were only able to recruit 193 participants from seven 11th-grade classes initially, which is approximately the required sample size. Information sheets were shared with all potential participants for their comprehension of the study and participants were asked to give their informed consent to this work, indicating they understood the study specifics and their willingness to voluntarily participate. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw and that their decision would not jeopardize their involvement in the intervention. Their parents also were asked to grant permission for their child to be a participant in the study. The principal of the school also gave an official letter to the researcher giving permission to move forward with this study. Ethical approval was obtained from Department of Training and Education of Thua Thien Hue Province before we began recruiting participants. The participants then gave the consent forms and completed the baseline questionnaires offline, hosted by our survey proctors. Within 24 hours of completing the baseline questionnaires, participants were randomized by drawing dots from their head teachers to either start the care-based intervention immediately or to join a control condition. Two participants (3.86%, one girl and one boy) did not complete the intervention and the follow-up session due to health and family problems: one suffered from a bicycle accident and the other lost a family member. After dropout, our final sample comprised 191 students, divided into two groups: intervention group (N = 95; 29 males and 66 females) and control group (N = 96; 37 males and 59 females). Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the adolescents in both groups. Only family size differed slightly (p < .05) between the two groups. Research Instruments All of the instruments used in the study were available in the Vietnamese language. The Care Competencies Questionnaire for Adolescents was created in Vietnamese and has been validated by Nguyen et al. (2020). The well-being measures, including the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire, the Perceived Stress Scale, and the Satisfaction with Life Scales, were translated into Vietnamese and validated by other authors (Nguyen & Nguyen, 2012; Tran, 2006) and have been used in multiple published research studies (e.g., Nguyen & Nguyen, 2020; Nguyen & Nguyen, 2023; Tran et al., 2020). Furthermore, all of the instruments used in the study demonstrated good reliability and validity in assessing care competencies and well-being in Vietnamese adolescents, building on an earlier study conducted by Nguyen et al. (2020). Care Competencies The Care Competencies Questionnaire for Adolescents (CCQA; Nguyen et al., 2020) was used to measure adolescents’ care competencies. This scale comprises six subscales measuring three dimensions of care in two modes of care, that is, competencies and failures: receiving care competencies (5 items; e.g., “I am happy when others share my joys and sorrows”); self-care competencies (5 items; e.g., “I try to understand the cause of negative emotions”); extending care competencies (6 items; e.g., “I feel happy when I see others happy”); receiving care failures (5 items; e.g., “When in sadness, I often avoid the comfort from others”); self-care failures (5 items; e.g., “When doing something wrong, I often criticize and hate myself”); and extending care failures (4 items; e.g., “When I see someone in pain or difficulties, I walk away”). Respondents scored each item on a Likert scale from 1 totally untrue about me to 6 totally true of me. Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales in this study were similar to Nguyen et al. (2020): receiving care competencies (.51), receiving care failures (.65), self-care competencies (.53), self-care failures (.58), extending care competencies (.68), and extending care failures (.63). As noted, some alphas of the subscales are modest. Although useful in assessing internal consistency, coefficient alpha is not without limitations, which unfortunately are often underappreciated (John & Benet-Martinez, 2000). To alleviate the limitations of coefficient alpha, as recommended by John and Benet-Martinez (2000), we also evaluated the average inter-item correlation to estimate internal consistency instead of trying to achieve a particular level of Cronbach’s alpha. Average inter-item correlations should fall somewhere between .15 and .50 (Clark & Watson, 1995). The subscales of the questionnaire showed acceptable internal consistency, with mean inter-item correlations falling within the recommended range (.18-.34) Well-being Well-being of adolescents was measured using three validated scales. The self-rated version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) was used to assess emotional and behavioral disorders of adolescents. It is a 25-item, 3-point Likert-scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = certainly true) widely used screener for detecting ill-being in adolescents in many developed and developing countries, including Vietnam (Tran, 2006); 20 items cover four areas of adolescents’ difficulties (5 items each): emotional symptoms (e.g., “I worry a lot”), conduct problems (e.g., “I get very angry and often lose my temper”), hyperactivity/inattention (e.g., “I am restless, cannot stay still for long”), and peer problems (e.g., “I am usually on my own”); 5 items aim to identify one area of adolescents’ strength: prosocial behavior (e.g., “I often volunteer to help others: parents, teachers, children”). To investigate the negative aspect of well-being among Vietnamese adolescents, in line with the manual, a total difficulties score was calculated (Goodman & Goodman, 2012). Cronbach’s alpha in our data was found to be .65. Second, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Cohen & Williamson, 1988) was used to measure adolescents’ global self-perceived stress over the last month (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”) on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = very often). In the present study, to obtain an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha, we had to leave out four positive items with low item-total correlations. Finally, six negative worded items were retained with a Cronbach’s alpha of .65. Finally, life satisfaction of adolescents was assessed using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985). The five scale items are phrased positively (e.g., “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life”) and rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha was found to be acceptable (.69). Research Procedure Operationalisation of Care Competencies In order to design the care-oriented intervention, a comprehensive framework for the underlying care constructs was needed. Researchers argue that if care can be specified and broken down into its elements, then it can, indeed, be taught (Griffiths et al., 2012). Therefore, based on the conceptualization of care as already mentioned above, we first identified framework components that are related to the sequence in effective handling of care competencies: (1) focusing the attention outward/inward, (2) connecting with self/others, and (3) set limits and problem solving; secondly, four components are identified that refer to psychological structures, such as: (4) motivation, (5) sensitivity, (6) tolerating emotions, and (7) opening up (Gilbert et al., 2017). This structured framework is the base for designing a curriculum: lesson plans were designed to include instructions addressing concrete steps in receiving care, self-care, and extending care, together with specific corresponding practices and techniques such as identifying emotions and needs, honestly expressing emotions and needs, showing gratitude, identifying strengths and weakness, empathetic listening, and accepting own worth (see Table 2, for an overview). Design of Video Vignettes Three video vignettes were developed to allow students to get in touch with the different care competencies. Given the vignette design, the above framework (Table 2) guided choices as to events, angles, and problems. The video vignettes are needed to represent realistic adolescent situations. Therefore, critical incidents related to adolescents’ care competencies were collected through a literature review, and observation and based on interviews with two Developmental Psychology experts and a group of seven adolescents. After clustering proposals for critical incidents, a set of vignettes was selected that helped comprehensively map the framework. Next, concrete video vignette development could start (see Appendix 2 for the overview of the topic, themes and a detailed description). Intervention Procedure The intervention was developed in-house by the main author of this study and based on instructional models adopted from video vignette-based studies in educational settings, such as Sung et al. (2022) and De Coninck et al. (2023). The intervention was set up in a seven-week time frame and consisted of eight sessions. The adolescent students who were part of the experimental group attended all sessions in the main hall of their high school in the morning and then resumed their regular classes in the afternoon as per their schedule. On the other hand, adolescent students in the control group had no instruction related to care competencies and followed their regular classes as usual in the afternoon. Opening Session. A presentation about the research project and the intervention was given. At this point, active informed consent was obtained from all participants. Following this, participants completed all pretest versions of the research instrument described earlier. Instruction Sessions. Instructions on how to receive care, extend care, and develop self-care, four hours each, were carefully delivered in three consecutive sessions. Steps and indicators in the model of care competencies (Table 1) were introduced to the adolescents. We built on Bloom’s taxonomy for adolescents to invoke student engagement by reflecting behavior at the level of remembering/perception, understanding/interpretation, and application. Therefore, instructional strategies were adopted that mixed lecturing with experiential learning approaches, such as discussion, role-play, and hands-on practices. Guided Practice Sessions. Three video vignettes (receiving care, self-care and extending care) and accompanying open-ended questions were respectively introduced to adolescents in three consecutive sessions. Each session lasted three hours. First, the instructor explained the aims and the procedure of the guided practice sessions. Next, the participants watched the vignettes (see Appendix 1), followed by a PID session. Adolescents worked collaboratively in small groups of 8 to 10 students. They used their past and current instructional histories to discuss the answers to open-ended questions embedded in the vignettes (see Appendix 2). The instructor’s comments supported the discussions and prompted adolescents (1) to indicate what they perceived in the video vignette, (2) to describe their interpretation of the situation, and (3) to make a decision and other relevant questions regarding skills and techniques of receiving care, self-care, and extending care. The group discussions provided adolescents with a practice field and with opportunities to reflect on their experiences. Next, role play was also applied to help students demonstrating their competencies to solve problems (specified in the vignettes) related to receiving care, self-care, and extending care. This was followed by feedback from the instructor. Finally, adolescents watched the video vignettes again and answered individually open-ended questions on printed sheets. The above procedure was inspired by the vignette instruction scaffolding design as suggested by Jeffries and Maeder (2009). Closing Session. Participants started by sharing – in their group – their personal experiences about receiving care, self-care, and extending care during the intervention (how they experienced care competencies and applied what they learned to their daily lives). This was followed by completing the post-test version of all research instruments. The session was wrapped up by participants and researchers who summarized and discussed key concepts. Participants were acknowledged for their participation and engagement. Follow-up Session. Two months after the intervention, participants filled out the follow-up version of the research instruments. Data Collection. The above procedure shows how data were collected at pre-test, post-tes,t and follow-up. Three data time points can be distinguished: T1 (right before the intervention), T2 (right after the intervention), and T3 (about two months after finishing the intervention). Data Analysis Descriptive statistics were analyzed using SPSS (version 26.0). We applied the full-information maximum likelihood approach to LGM in Mplus 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) to examine the initial level (i.e., intercept) and the change (i.e., slope) in care competencies and well-being among adolescents over time (Duncan et al., 2006). Model fit was evaluated using the chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ²/df), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the comparative fit index (CFI) (Byrne, 2010). Following benchmark fit values were put forward: normed χ² ≤ 3, RMSEA < .05, with < .08 being acceptable, CFI > .95, with > .90 being acceptable, and SRMR < .05, with <.08 being acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011). We estimated growth curves (i.e., in receiving care competencies, receiving care failures, self-care competencies, self-care failures, extending care competencies, extending care failures, life satisfaction, perceived stress and emotional and behavioral problems) based on nine separate LGMs. The mean intercept in these models represents the average level of the outcome variables at the pre-test. The mean slope represents the average rate of change between two waves. In addition, also variance around intercept and slope was modeled. To compare differences in means of level and rate of change in outcome variables across the intervention and control groups, we applied multigroup modeling (Bollen, 1989). Initially, an LGM was estimated with both means freely estimated in the two groups. Next, we constrained both means to be equal across groups and compared the fit of the free and constrained model by applying a chi-square difference test. If the latter was significant – indicating difference(s) between the two groups – we further checked modification indices to identify which of the two means had to be relaxed to obtain adequate model fit. Finally, factor scores of LGMs were saved to start correlation and multiple linear regression analysis by using SPSS (version 26.0) to explore the relationships between the changes in care competencies/failures and the changes in well-being. Descriptive Statistics Table 3 summarizes the means and standard deviations for student adolescents’ care competencies/failures and well-being scores across the three measurement occasions. Table 4 Univariate Latent Growth Curve Model: Means of Levels & Rates of Change and Model Fit   Note. Different means indicate significantly different (p < .01) mean levels and/or rates of change between intervention and control group. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Changes in Care Competencies/Failures and Adjustment to Be Attributed to the Intervention Table 4 summarizes the multigroup LGMs comparing mean levels and changes in care competencies and failures, as well as adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment, between the intervention and control groups in this study. Fit indices indicated that all final models fitted the data adequately. The mean level differences (intercept) between the control and intervention groups were significant for only three variables, indicating success in randomization. Differences in rates of change (slope) were significant for all nine variables in the intervention group. Thus, adolescents in the intervention group significantly increased, on average, in care competencies and life satisfaction and decreased in care failures and perceived stress and emotional/behavioral problems, whereas this was not the case in the control group. Care Competencies/Failures For receiving care competencies (RCC) the free and constrained models significantly differed from each other in terms of model fit, Δχ²(2) = 22.61, p < .001. Relaxing the mean slopes significantly improved model fit, Δχ²(1) = 14.05, p < .001, as did relaxing the mean intercepts, Δχ²(1) = 15.66, p < .001. As can be seen in Table 3, the level of RCC was higher in the intervention group and only in this group RCC increased following the intervention. In the control group a slight decrease was observed on average. Inspection of individual slope estimates indicated that in the intervention group 91.6% of adolescents showed increasing levels of RCC, whereas in the control group only 34.4% of adolescents increased in RCC. Similar results were found for receiving care failures (RCF). Fit of the free and constrained model was significantly different, Δχ²(2) = 65.99, p < .001. Relaxing the mean slopes, Δχ²(1) = 61.14, p < .001, and the mean intercepts, Δχ²(1) = 26.32, p < .001, significantly improved model fit. As can be seen in Table 3, the level of RCF was lower in the intervention group and only in this group RCF decreased following the intervention. In the control group no change in RCF was observed on average. Individual slope estimates indicated that in the intervention group, all adolescents showed decreasing levels of RCF, whereas in the control group only half of the adolescents decreased slightly in RCF. Free and fixed models for self-care competencies (SCC) differed significantly in model fit, Δχ²(2) = 36.62, p < .001. Only after relaxing the mean slopes, Δχ²(1) = 38.74, p < .001, model fit significantly improved. In the intervention group, SCC on average increased significantly, whereas in the control group, a slight decrease in SCC was observed (Table 3). Individual slope estimates showed that 97.9% of the adolescents in the intervention group increased their SCC during the study, compared to only 43.2% of adolescents in the control group. Similarly, for self-care failures (SCF), the model fit of the free model was significantly different from that of the constrained one, Δχ²(2) = 101.30, p < .001. Only relaxing the mean slopes, Δχ²(1) = 89.09, p < .001, resulted in significant improvement in model fit. Table 3 reveals that adolescents in the intervention decreased in self-care failures across the period of this study, whereas a flat trajectory of self-care failures was observed among adolescents in the control group. Individual slope estimates showed that all adolescents in the intervention group decreased their SCF, while only 56.3% of the adolescents in the control group decreased slightly in SCF. Constrained and unconstrained models of extending care competencies (ECC) differed significantly, Δχ²(2) = 74.88, p < .001. Model fit improved once the constraints on the mean slopes, Δχ²(1) = 100.25, p < .001, and mean intercepts, Δχ²(1) = 30.56, p < .001, were relaxed. As can be observed in Table 4, the ECC level was higher in the intervention group and only in this group ECC significantly increased following the intervention. In the control group, a decrease in ECC was observed on average. Individual slope estimates showed that all adolescents in the intervention group increased in their ECC, while 45.8% of the adolescents in the control group increased in ECC. Similarly, constrained and unconstrained models of extending care failures (ECF) were significantly different, Δχ²(2) = 50.88, p < .001. Relaxing the mean slopes again significantly improved the model fit, Δχ²(1) = 53.70, p < .001. Table 3 shows that in the intervention group ECF on average decreased significantly, whereas in the control group ECF on average increased significantly. Individual slope estimates also showed that all adolescents in the intervention group decreased in ECF, whereas only 37.5% of the adolescents in the control group decreased in ECF. Well-being For life satisfaction (LS), the free and fixed model differed significantly, Δχ²(2) = 62.95, p < .001. The fit of the model significantly improved by releasing constraints only on mean slopes, Δχ²(1) = 49.99, p < .001. As can be seen in Table 4, in the intervention group life satisfaction increased significantly, whereas in the control group life satisfaction did not change during the 12 weeks. Individual slope estimates showed that all adolescents in the intervention group increased in LS, whereas only half of the adolescents in the control group increased in LS. For emotional and behavioral problems, there was a significant difference in model fit between the free and constrained model, Δχ²(2) = 10.97, p < .01. Only by relaxing the constraint on mean slopes, model fit improved, Δχ²(1) = 9.62, p < .01. As shown in Table 4, emotional and behavioral problems decreased on average in the intervention group. In contrast, in the control group, these problems remained stable within the 12-week window. Individual slope estimates showed that emotional and behavioral problems reduced in 86.3% of the adolescents in the intervention group, whereas these problems reduced slightly in 79.2% of the adolescents in the control group. For perceived stress, fixed and free models also significantly differed, Δχ²(2) = 29.91, p < .001. Model fit significantly improved by relaxing mean slopes, Δχ²(1) = 31.48, p < .001. As shown in Table 3, results indicated that perceived stress significantly decreased over time in the intervention group. In the control group, the slope factor mean was not significant, indicating that perceived stress on average remained stable across the data collection period. Individual slope estimates also showed that 60.4% of the adolescents in the control group experienced reduced stress, while 97.9% of the adolescents in the intervention group demonstrated decreases in perceived stress. Changes in Care Competencies/Failures Predicting Changes in Adjustment Due to the Intervention Table 5 shows correlations and regression coefficients relating changes in care competencies and failures to changes in adjustment, separately for the control and the intervention groups. Initially, we examined possible relationships of demographic variables (see Table 1) with changes in the adjustment variables in this study. A multivariate ANCOVA revealed no significant (p < .01) relationships. Therefore, no control variables were included in this last set of analyses. The results showed that in the control group only decreases in self-care failures predicted decreases in behavioral and emotional problems. In the intervention group, both changes in care competencies and failures predicted changes in well-being. Table 5 Correlations and Regressions between Changes in Care Competencies/Failures and Changes in Adjustment, in Control and Intervention Group   *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Specifically, in the intervention group increases in receiving care competencies significantly predicted decreases in behavioral and emotional problems. Further, increases in extending care competencies predicted decreases in perceived stress and life satisfaction. Increases in receiving care failures predicted decreases in life satisfaction, increased perceived stress, and behavioral and emotional problems. The predictive power of changes in receiving care competencies and failures seems to be the strongest. While changes in self-care competencies and failures were found to be correlated with changes in perceived stress, and behavioral and emotional problems, the unique predictive power of changes in self-care failures and competencies was not observed following the intervention. Firstly, our first hypothesis was confirmed. LGM analyses provided evidence that, on the one hand, the care competencies of adolescents in the experimental group increased; on the other hand, their care failures decreased across the time of the study. Specifically, they demonstrated increases in skills related to identifying their own and others’ emotions and needs, tolerating, accepting, and expressing these emotions and needs with an open mind and empathetic heart, as well as taking helpful actions to meet their own and others’ needs. At the same time, they made progress in reducing negative self-talk, self-criticism, harsh judgement, and ignorance about other’s needs and emotions. Among care failures, self-care failures most significantly decreased. Many self-care techniques are closely related to self-awareness skills. The surprising thing about self-awareness is that just thinking about it seems already improving this skill (Bradberry & Greaves, 2015). These findings support previous studies that care-oriented programs might positively affect social and emotional skills in students (Battistich et al., 1997; Center for the Collaborative Classroom, 2016; Chang, 2008; Tran et al., 2023; Watson et al., 2019; Wright & Martz, 2022). Secondly, the second hypothesis of the study was proven. The LGM analyses conducted in the study provided evidence of two main findings. First, the positive aspect of well-being, which was measured by life satisfaction, improved for adolescents in the experimental group. Second, the negative aspects of well-being, which were measured by perceived stress as well as emotional and behavioral problems, decreased throughout the study. These findings were in line with the results of previous quantitative studies to evaluate the impact on well-being (Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2017; Bluth et al., 2015; Charbonnier et al., 2022; Geier & Morris, 2021; Lambert et al., 2022; Sakofsky, 2009; Schultze-Krumbholz et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2023; Watson et al., 2019; Wright & Martz, 2022). Thirdly, the third hypothesis was confirmed. The findings of correlations and regression analysis revealed that increased care competencies and decreased care failures led to better well-being among adolescents in the intervention group, stating that the care-based training led to a significant improvement across diverse psychosocial outcomes. In terms of the role of receiving care on well-being, previous studies discovered that perceived and received social support predicted well-being (Gülaçtı, 2010; Melrose et al., 2015). There is a growing body of evidence that suggests our brain functions better with lower levels of stress hormone cortisol when we interact with others and experience togetherness (Hari et al., 2015; Steptoe et al., 2004). Regarding the impact of self-care practices on well-being, previous studies also reveal that practicing aspects of self-care such as emotional awareness, corrective negative self-talk, positive thinking, or self-talk reduced the harmful effects of stress (Tran et al., 2023) and increased resilience (Bluth & Eisenlohr-Moul, 2017). Next, our study findings support previous research on the positive effects of extended care on well-being. Adolescents’ well-being can be enhanced by understanding and accepting others’ perspectives, intentions, emotions, and needs, as well as living and sharing with others’ emotions (Tran et al., 2023; Watson et al., 2019). Noticeably, care failures are stronger predictors of well-being than care competencies and self-care failures are the strongest predictors of stronger increases in social-emotional difficulties in the control group and the intervention study. These results seem to imply that overcoming care failures is more important than building up care competencies when dealing with ill-being, especially overcoming self-care failures. Moreover, in the present study, changes in receiving care competencies are the strongest predictors of decreases in emotional and behavioral problems, and decreasing receiving care failures is the strongest predictor of decreases in perceived stress and increases in life satisfaction in the intervention group. Thus, besides learning to overcome self-judgment and self-criticism, learning to be more aware of, seeking, and more receptive to many sources and moments of care play an important role in the enhancement of adolescents’ well-being. Receiving care from others can be regarded as the foundation of a healthy, whole person (Lavusa, 2010; Sivan et al., 2017). This is congruent with previous conclusions (e.g., Veslez et al., 2016; Wilkinson & Walford, 2001) and the highlight of WHO (Barker, 2007) on the role of social support-seeking and secure attachment on adolescents’ well-being. Practicing skills for deepening their openness and receptivity to care is, therefore, very critical. It also helps Vietnamese adolescents to consider receiving care as an intuitive entrance point to develop self-care and extend care to others. Our study found that care-based programs must include receiving care competencies that were ignored in previous interventions. An additional shared finding from previous empirical studies is that extending care competency is not a strong precursor to adolescents’ well-being (Dinh et al., 2021; Nguyen et al., 2020). However, in the present study changes in extending care competencies predicted to a certain extent decreasing perceived stress and served as the sole predictor of increasing life satisfaction in the intervention group. In fact, of the three components of care, the relationship between extending care and well-being seems to be the most complicated. As said, extending care may only be related to high well-being when it results from a natural feeling of worthiness, dignity, and self-compassion. The latter seems cultivated through the other components: receiving care and developing self-care. The idea that one “should” or “must” care for others can cause empathy fatigue (MLI, 2014a). Though no interaction analysis was conducted, it seems that increased receiving care competencies and self-care competencies offer a setting in which extending care competencies plays a beneficial role. This finding reiterates the importance of adopting a holistic view towards care in care-based intervention programs for adolescents. Unexpectedly, in the present study, in the control group, some adolescents also reflected an increase in competencies or a decrease in care failures. This might result from being influenced by adolescents from the intervention group. For example, adolescents in the control group might have learned from the way their classmates in the intervention group started regulating their emotions more constructively, or successfully solved problems in potentially stressful situations and/or effectively sought support from teachers and peers. Human learning often results from observing a person who already masters the skills and models them adequately (Bandura, 1969). However, in the intervention group, but not in the control group, the changes in care competencies and failures consistently and significantly predicted changes in well-being. This finding supports the conclusion that adolescents’ larger improvement in well-being can be causally assigned to the care-oriented program. In conclusion, our study findings add to the evidence that supports the connection between a pedagogy of care and fostering well-being. Care competencies could therefore be regarded as catalysts important for adolescents’ well-being. The findings support the argument that caring can be taught/learned if it is properly defined and operationalized (Griffiths et al., 2012). The instructional video vignettes with the PID approach did prove its efficacy in addressing specific care elements, boosting students’ engagement, mobilizing adolescents’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviors to deal, with critical incidents, and resulting in the further development of the care competencies as dispositions and the capacity to overcome care failures. School curriculum could therefore be infused with attention for the development of care competencies, in connection to the traditional academic competencies and skills being pursued (Noddings, 1995). Our study provides a theoretical framework to operationalize care competencies and evidence-based findings that highlight the requirement of including three dimensions of care, especially receiving care competencies in care-based programs. Specifically, it seems fruitful to convey activities with the support of video vignettes for adolescents to internalize and integrate the three components of care, in view of attaining lasting positive effects. Moreover, the activities should be tailored to both promote care competencies and reduce care failures to enhance Vietnamese adolescents’ well-being. In particular, overcoming self-care failures, receiving care failures, and building up receiving care competencies can be the keystones of the program. Limitations and Directions for Future Research A number of limitations have to be addressed in view of developing future research. One of the main limitations of the study is the generalizability of the findings. First, although the samples were supposed to be randomly selected, there were some shortcomings in the random selection process. The School Board only permitted the intervention to be performed on 11th-grade students, so the sample was randomly selected from this group alone. Therefore, each 11th-grade adolescent student had an equal chance of being included in the sample, and the data collected can only provide conclusions for the entire 11th-grade population. To improve the generalizability of the conclusions, future studies should include 10th and 12th-grade adolescent students in the sample. Second, the sampled population of the study was limited to adolescents aged 16-18 years in Hue City, Central Vietnam. This limitation also affects the generalizability of the findings. It puts forward the importance of replicating the study by involving early and late adolescents from the North or South of Vietnam when looking at this particular society. Third, although the study aimed to reach a sample size of approximately 200 to model growth (Cheong, 2011), its power can be criticized due to the small sample size. Future research should try to replicate current findings involving larger and also more varied samples. This returns in a second observation that might affect the generalizability of the current findings. Our sample contained mostly adolescents from rural areas, from intact and well-adapted families. Future studies could look into more detail to critical population stratification variables in a country or region. Fourth, some research instruments reflected lower Cronbach’s alpha values, but the mean inter-item correlation for each subscale was within the recommended range, indicating acceptable internal consistency. In the present study, we dealt with this problem by adopting structural equation modelling (SEM). This helps using latent variables that represent the true variance of a variable, thus, avoiding potential problems caused by measurement error. It is important to note that the validation of the care competencies assessment tool is only the first effort to understand the level of care competencies among Vietnamese adolescents by Nguyen et al. (2020). Further research is required to scale up the tool and test the psychometric characteristics of the questionnaire with a larger number of participants. Fifth, we relied on self-report questionnaires for data collection, which may lead to survey errors such as measurement errors and social desirability bias, despite our efforts to design and test the instruments thoroughly. Future research should include mixed research methods (e.g., questionnaires and structured interviews) and mixed analysis to reduce the impact of these biases. Sixth, our study confirms the potential of enhancing care competencies to promote the well-being of adolescents. Yet, the processes through which this care-based intervention works to enhance well-being remain largely speculative. This introduces the need for setting up future intervention research that addresses mechanisms. Conclusions Some care ethicists believe education should concentrate more on students’ capacity to care. Despite being a core concept in education, care is hardly reflected in Vietnamese school curricula. This weakens their potential to foster the internalization of care-related attitudes and behavior in adolescent students. The present study demonstrated the promise of a structured care-oriented program. While the field is still in its infancy in Vietnam, our findings support the feasibility and adequacy of the proposed caring framework and how video vignettes are a promising ingredient to develop structured educational programs. When care becomes part of the curriculum, children and adolescents might be better able to flourish and reach their potential in a safe, open, and nurturing environment. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We are grateful to the schools and students participating in this study. Cite this article as: Nguyen C-T. P., Beyers, W., Valcke, M., & Dinh, H-V. T. (2024). Care competencies training enhances adolescents’ well-being: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(3), 147-169. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a10 Funding: This research is supported by the VLIR-IUC Program Hue University (iuc.hueuni.edu.vn). |

Cite this article as: Nguyen, C. P., Beyers, W., Valcke, M., & Dinh, H. T. (2024). Care Competencies Training Enhances AdolescentsŌĆÖ Well-being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(3), 147 - 169. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a10

Correspondence: npctuong@hueuni.edu.vn (C-T. P. Nguyen).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS