Dual-factor Models of Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence

Eunice Magalhães

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), CIS-IUL, Lisboa, Portugal

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a6

Received 8 September 2023, Accepted 23 January 2024

Abstract

Objective: Dual-factor models of mental health propose that mental health includes two interrelated yet distinct dimensions – psychopathology and well-being. However, there is no systematization of the evidence following these models. This review aims to address the following research question: what evidence exists using dual-factor models? Method: The current systematic review was conducted using PRISMA guidelines on the following databases: Web-of-science, Scopus, Academic Search Complete, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, ERIC, and MEDLINE. The screening process resulted in 85 manuscripts that tested the assumptions of dual-factor models. Results: Evidence revealed psychometric substantiation on the two-dimensionality of the dual-factor model, and 85% of the manuscripts provided evidence related to classifying participants into different mental health groups. Most studies showed that the Complete Mental Health or Positive Mental Health group is the most prevalent status group, and longitudinal evidence suggests that most participants (around 50%-64%) remain in the same group across time. Regarding the factors associated with mental health status groups, studies reviewed in this manuscript focus mainly on school-related outcomes, followed by supportive relationships, sociodemographic characteristics, psychological assets, individual attributes, physical health, and stressful events. Conclusions: This review highlights the importance of considering the two dimensions of mental health when conceptualizing, operationalizing, and measuring mental health. Fostering mental health must go beyond reducing symptoms, and practitioners would be able to include well-being-related interventions in their regular practice to improve individuals’ mental health outcomes.

Keywords

Dual-factor models, Mental health groups, Systematic reviewCite this article as: Magalhães, E. (2024). Dual-factor Models of Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 89 - 102. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a6

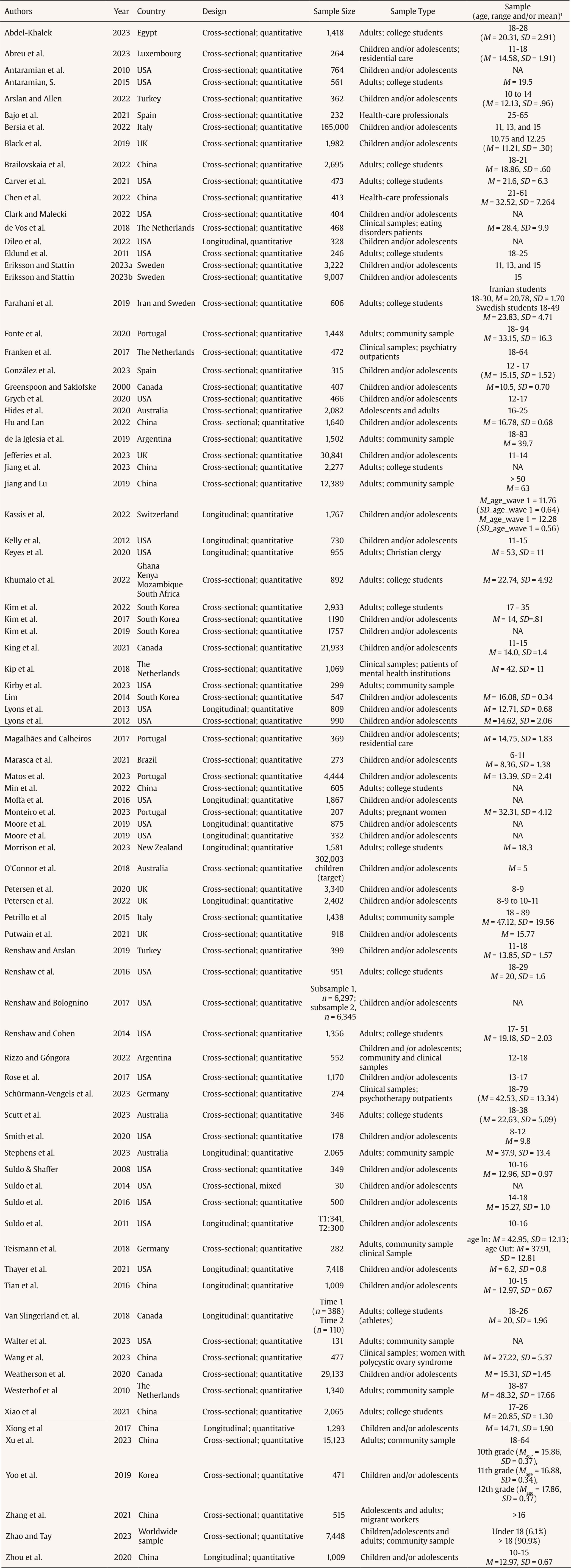

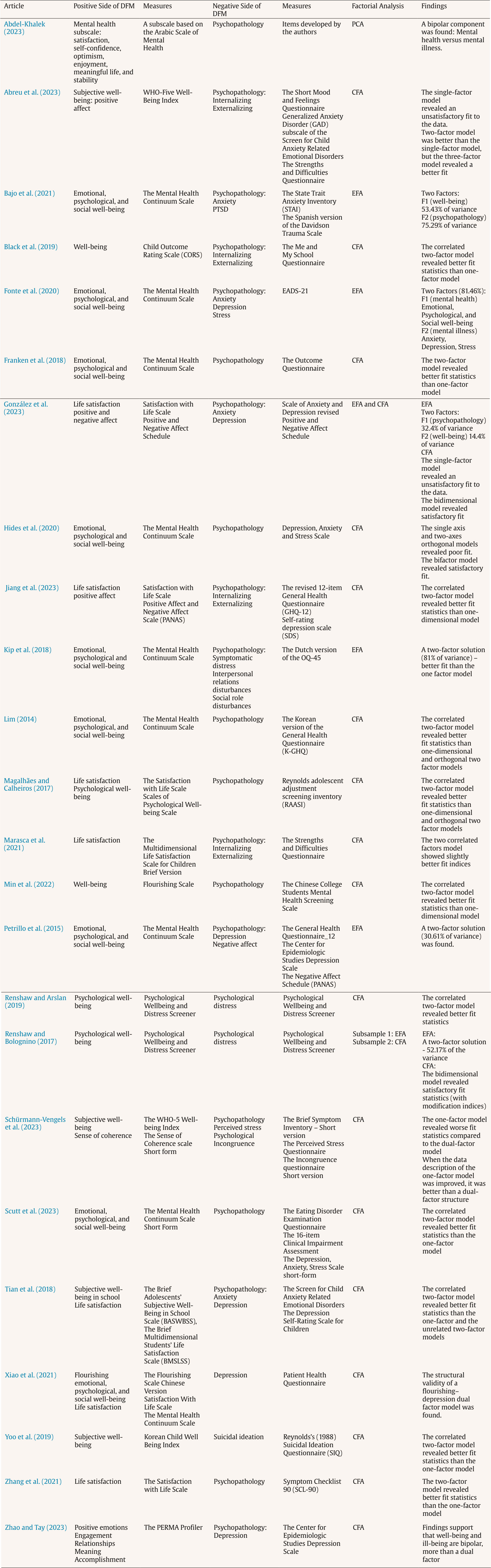

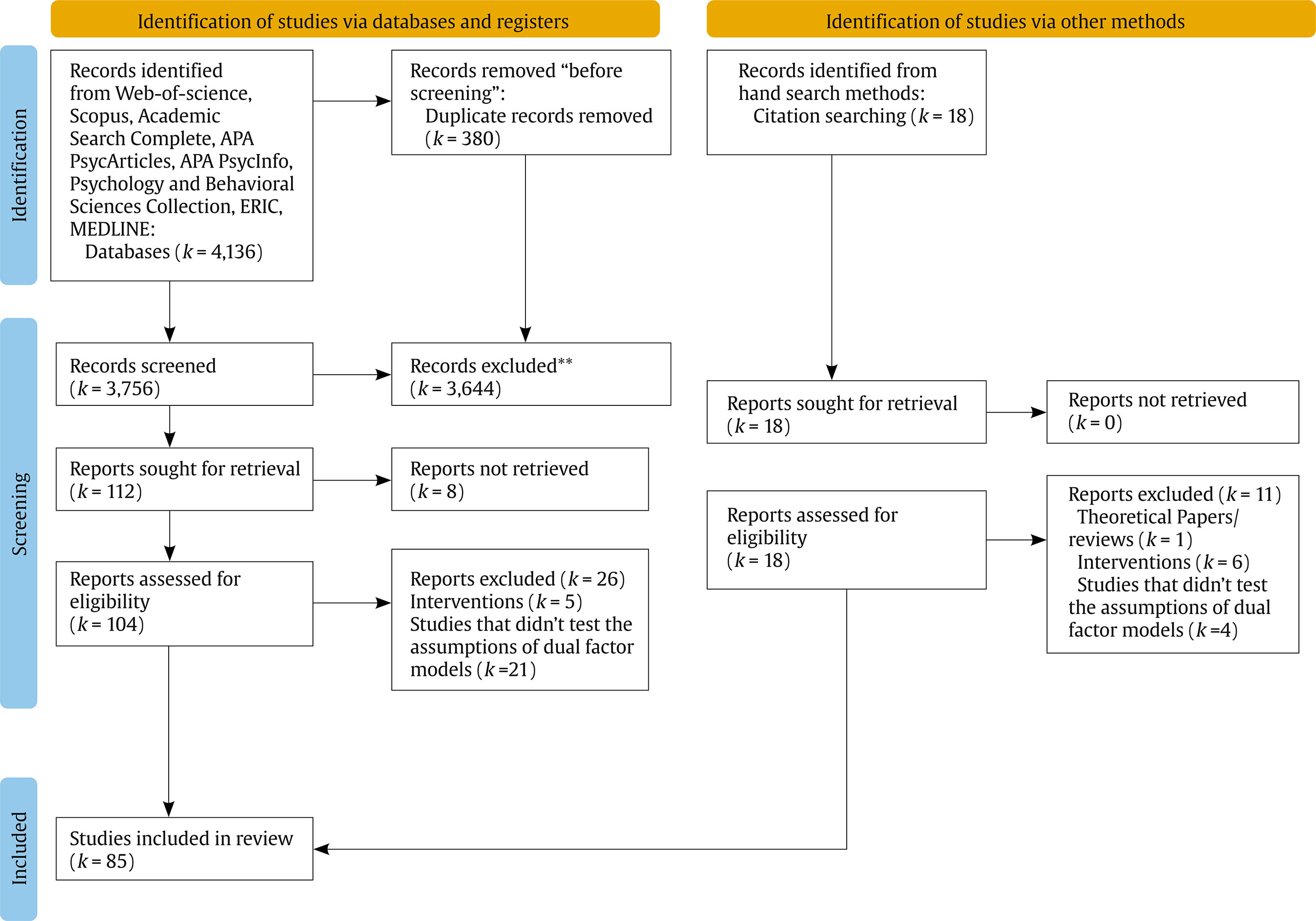

Correspondence: Eunice_magalhaes@iscte-iul.pt (E. Magalhães).The medical model of mental health has been focused across decades mainly in the absence of psychopathology as an indicator of health (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001). However, the last 20 years have brought a more integrative perspective to mental health, moving on to positive psychology and well-being (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Mental health has been conceptualized as including these two interrelated yet distinct dimensions – psychopathology and well-being – contradicting the one-dimensional traditional view (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001). Mental health is viewed as a complete state which includes both positive and the absence of negative outcomes (Wang et al., 2011). The positive side of mental health includes well-being dimensions such as life satisfaction, psychological, emotional, or social well-being, and positive affect; on the other hand, the negative side of mental health involves psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety, internalizing, and externalizing symptoms), indicators of mental distress, and mental disorders (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Westerhof & Keyes, 2010). As such, different profiles might emerge by the intersection of psychopathology (high vs. low) and well-being (high vs. low) (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Wang et al., 2011; Westerhof & Keyes, 2010). This paradigmatic change emphasized the need for prevention and promotion programs and strategies (fostering individuals’ well-being and positive outcomes) rather than solely providing treatment to reduce psychological problems. As such, to be able to design effective interventions (i.e., define strategies, targets, and groups to whom prevention and intervention programs should be delivered), we need to clarify the empirical evidence obtained from these conceptual models, as well as what factors are associated with different profiles of mental health. This systematic review aims to address these needs. Theoretical Proposals of Dual-factor Models Greenspoon and Saklofske (2001) provided evidence on the dual-factor model of mental health for the first time toward a combination of well-being and psychopathology. The authors aimed to explore this combined system of mental health with children, allowing the identification of different at-risk profiles that might inform intervention and prevention (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001). Based on individual scores on well-being and psychopathology, children were classified according to four mental health groups: well-adjusted (high well-being and low psychopathology), externally maladjusted (high well-being and psychopathology), dissatisfied (low well-being and psychopathology), and distressed (low well-being and high psychopathology). The dual-factor model offers a more comprehensive understanding of mental health than unidimensional models, allowing the identification of two additional groups that are frequently overlooked in conventional models: children without clinical scores of psychopathology but also with low levels of well-being, and children with psychopathology but at the same time revealing high levels of well-being (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001; Lyons et al., 2012). Other authors have provided evidence on these four groups, assigning slightly different designations to their groups but with the same meaning: Complete Mental Health (high well-being and low psychopathology), Symptomatic but Content (high well-being and psychopathology), Vulnerable (low well-being and psychopathology), Troubled (low well-being and high psychopathology) (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Suldo & Shaffer, 2008). Other authors named the Complete Mental Health group the Positive Mental Health Group (Antaramian et al., 2010; Lyons et al., 2012), but the other groups remained the same as Suldo and Shaffer (2008). The dual-factor models provide evidence that well-being and psychopathology are not the opposite sides of the same construct, suggesting that around 7-13% of people show low psychopathology and low well-being and that around 9-17% show high well-being but also high psychopathology (Antaramian et al., 2010; Lyons et al., 2012; Suldo & Shaffer, 2008). These findings mean that, on the one hand, it is not enough to have positive mental health outcomes scoring lower on psychopathology measures. On the other hand, it is not incompatible to score high on well-being when dealing with psychopathology (Antaramian et al., 2010; Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017). This assumption has been proven with non-clinical samples of children and adults (such as in school contexts) (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010), but also with samples of children and young people exposed to adversity (Grych et al., 2020) or placed in residential care (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017). Research with victimized or traumatized people tends to overlook other mental health status than the damaged/troubled profile (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017). As such, psychosocial interventions with these samples may overlook the needs of young people with different profiles (e.g., vulnerable or symptomatic but content groups) by providing them with one-size-fits-all strategies to address their mental health difficulties (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017). In sum, dual-factor models of mental health have been providing an alternative conceptualization of mental health for the last 20 years, with children (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001), adolescents (Antaramian et al., 2010), and adults (Eklund et al., 2011). However, there is no systematization of the psychometric evidence for this model and which variables may differentiate the groups. This systematic review aims at (a) summarizing existing evidence about the psychometrics of the dual-factor models and (b) outlining variables that distinguish the different groups of mental health status. The results of this systematic review may provide insightful implications for practice and research. First, based on the current knowledge, researchers may further explore innovative models with predictive value of different mental health groups, and second, practitioners may be more able to develop and implement psychosocial interventions based on the specific needs of different groups rather than based on a classical one-dimensional view of mental health. Literature Search Strategy A literature search was conducted in eight databases (in June 2022): Web-of-science, Scopus, Academic Search Complete, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, ERIC, MEDLINE. The combination of the following keywords was searched: a) Dual factor system OR Dual factor model OR Dual continu* model AND b) mental health OR mental illness OR mental well-being. The search was conducted from the first record to January 3rd, 2024, and it was limited to peer-reviewed journals. This systematic review was not registered. In addition, the list of references of the retained papers was analysed, resulting in the inclusion of a set of articles by hand search (see Figure 1, the identification of studies via other methods). Data was extracted to an Excel file, aggregating information about studies’ characteristics (i.e., authors, title, years, country, design, sample size, sample type, age of participants), dimensions related to dual-factor models (i.e., positive dimensions, measures of positive dimensions, negative dimensions, measures of negative dimensions, factorial evidence), and group classification (i.e., prevalence of mental health groups, classification type, main findings). Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria To be included in this systematic review, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) empirical studies providing psychometric evidence on the two-dimensionality of the dual-factor model, or (2) empirical studies describing the groups of mental health and/or associations with individual, relational, or contextual variables, and (3) published in English, Portuguese, or Spanish. Literature reviews, dissertations, case studies or theoretical articles, qualitative studies, and studies describing interventions were excluded. Study Selection and Data Extraction The step-by-step guidelines of PRISMA Statement [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews] (Page et al., 2021) were adopted to screen the title, abstract, and full text (Figure 1). The database search allowed the identification of 4,136 articles, and after removing duplicates, a screening of 3,756 articles (title and abstract) was performed using the Rayyan web app, which is an artificial intelligence (AI) screening tool for Systematic Literature Reviews (Ouzzani et al., 2016). One researcher screened all articles, and around 30% of them (n = 1,070) was screened also by one other independent rater. Inter-agreement reached 99.4% of agreement, and the disagreements (i.e., six manuscripts) were solved through a discussion between raters. Eight reports were not available in the databases we have access and for that reason, they were excluded. Furthermore, a hand search was performed through the reference list, allowing us to find 18 new papers. After the full-text analyses of 122 articles (104 from databases and 18 from hand search), 37 records were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria: (1) they did not test the assumptions of dual-factor models, (2) they included the test of interventions, and (3) they were a theoretical or review article. This process allowed the identification of 85 manuscripts that focused on testing the assumptions of dual-factor models. The items marked with an asterisk in the reference list are those included in the systematic review. Studies Characteristics The selected studies were published between 2001 and 2023, most of them (f = 53) in the last five years (2019-2023) (Table 1). Regarding the geographic regions, 30 studies were carried out in North of America (e.g., Antaramian, 2015), 23 in Europe (e.g., Black et al., 2019), 18 in Asia (e.g., Jiang & Lu, 2019), five in Oceania (e.g., Hides et al., 2020), three in South of America (de la Iglesia et al., 2019; Marasca et al., 2021), two from Turkey (Arslan & Allen, 2022; Renshaw & Arslan, 2019), two in Africa (Khumalo et al., 2022), and two involving samples from more than one continent (Farahani et al., 2019). Table 1 Characteristics of Studies   Note. 1Age reported in years. NA = not available; T1 = time 1; T2 = time 2. These studies mainly included samples of children and/or adolescents (f = 47; e.g., Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017), 35 involved samples of adults (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2022), and three included both adolescents and adults (Hides et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Most studies were cross-sectional (f = 68; e.g., Bajo et al., 2021), and only 17 were longitudinal (e.g., Kassis et al., 2022). Psychometric Evidence on the Two-Dimensionality of the Dual-Factor Model The dual-factor model psychometric assumptions were tested in 24 studies (Table 2): 17 ran confirmatory factor analyses - CFA (e.g., Black et al., 2019), 5 ran exploratory factor analyses – EFA (e.g., Bajo et al., 2021), and 2 ran both EFA and CFA (i.e., Gonzalez et al., 2023; Renshaw & Bolognino, 2017). Most of these studies (f = 21) provided factorial evidence supporting the dual-factor model of mental health, revealing two independent but related factors: positive mental health and mental illness. Three manuscripts (Abdel-Khalek, 2023; Schürmann-Vengels et al., 2023; Zhao & Tay, 2023) reported that a bipolar component or the one-factor model might represent better mental health than a dual-factor model. Table 2 Psychometric Evidence on the Dual-Factor Models (DFM)   Note. PCA = principal components analysis; EFA = exploratory factor analysis; CFA = confirmatory factor analysis. Mental Health Groups Detailed data extracted from the primary articles is reported in supplementary material (Table S1). Regarding the mental health groups, 72 manuscripts provided evidence of classifying participants into different groups (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010; Arslan & Allen, 2022). To classify people, most of them (f = 45; e.g., DiLeo et al., 2022) applied a cut score approach (which means that they used the participants’ scores on the well-being and/or psychopathology dimensions to group them into high vs. low), 21 used latent analyses (i.e., profile, class, or transition analyses) (e.g., Clark & Malecki, 2022), one applied discriminant function analyses (i.e., Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001), three adopted a hierarchical clusters method (e.g., de la Iglesia et al., 2019), one compared the cut score approach with a latent profile analysis (i.e., Thayer et al., 2021), and one was unclear regarding the classification type (i.e. Kim et al., 2022). A diversity of mental health groups was identified. Twenty-one papers classified their participants according to the following groups: Complete Mental Health, Symptomatic but Content, Vulnerable, and Troubled (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2022). Sixteen manuscripts adopted this classification but replaced the label of some groups with a different proposal (e.g., the Complete Mental Health label was replaced by Positive Mental Health) (e.g., Grych et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2012). Nineteen papers described mental health groups according to the dual continuum perspective (i.e., Languishing and Flourishing), combining these categories with diagnosis or symptom scores (e.g., Kim et al., 2019). Finally, sixteen provided other categories grouping participants in terms of high and low well-being and distress/symptoms (e.g., Carver et al., 2021; Eklund et al., 2011). Most studies (f = 33) show that groups representing high well-being and low psychopathology (e.g., Complete Mental Health, Positive Mental Health) were the most prevalent status groups (Brailovskaia et al., 2022; Grych et al., 2020). Two studies showed that the Troubled group seems to be the most prevalent (35%, 33.9%), involving young people in residential care (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017) and a Chinese community sample (Xu et al., 2023). Also, a study with inpatients and outpatients revealed that the Troubled group was more prevalent (outpatients = 37%, inpatients = 53%), followed by the Vulnerable group (outpatients = 35%, inpatients = 20%), with the Complete Mental Health group being less prevalent (outpatients = 23%, inpatients = 17%) (Teismann et al., 2018). Furthermore, a study with American high school students found that the Vulnerable group was slightly more prevalent (33%) than the Complete Mental Health (27%) (Suldo et al., 2014). Wang et al., (2023), in a study involving women with polycystic ovary syndrome, found that more than half of the sample belongs to the Symptomatic but Content group. The Symptomatic but Content group represents around 3%-53% (e.g., Min et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023), Vulnerable around 4%-35% (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2022; Teismann et al., 2018), and the Troubled group around 3%-53% (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2022; Teismann et al., 2018). Regarding the evidence about the longitudinal trajectories of these groups, this systematic review revealed that most participants (around 50%-64%) remain in the same group across time (Dileo et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2017). Most of these studies suggested that the most stable group status is the Complete Mental Health group (Moore et al., 2019a; Petersen et al., 2022; Xiong et al., 2017), and less stable is the Troubled group (Moore et al., 2019a; Xiong et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2020). Non-consistent findings were found for the Vulnerable group, highlighted as the most stable group (Zhou et al., 2020) and the least stable group (Petersen et al., 2022). Factors Associated with Mental Health Status The studies reviewed in this manuscript focus mainly on school-related outcomes (f = 24), such as academic achievement, academic engagement, grade point average, learning skills (e.g., Marasca et al., 2021; O’Connor et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2020), followed by supportive relationships or interpersonal connectedness (f = 17), from different sources (e.g., peers, family, teachers, staff in residential care) (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010; Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Petersen et al., 2020), and sociodemographic characteristics (f = 16; e.g., Clark & Malecki, 2022; Kassis et al., 2022). Also, individual attributes (such as personality, temperament or locus of control) (f = 8; e.g., Farahani et al., 2019; Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001), physical health and activity (f = 8; e.g., Jiang, & Lu, 2019; Renshaw & Cohen, 2014), psychological assets (f = 7), such as gratitude, grit, or hope (e.g., Carver et al., 2021; Grych et al., 2020), and perceived stress or stressful events (f = 5; e.g., Lyons et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2021), were also explored by these studies. In terms of school-related outcomes, most evidence suggests that the positive/complete mental health group reveals the highest levels of these outcomes (e.g., academic engagement, GPA, academic self-perceptions; e.g., Antaramian, 2015; Antaramian et al., 2010; Arslan & Allen, 2022; Moore et al. 2019b; Kim et al., 2022; Renshaw & Cohen, 2014; Smith et al., 2020), and the Troubled group (or similar profiles with different designations) showing the worst results (e.g., Dileo et al., 2022; King et al., 2021; Moffa et al., 2016; Moore et al., 2019b; O’Connor et al., 2018; Petersen et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2017). Other authors found that the Symptomatic but Content group (high level of symptoms and subjective well-being) revealed the lowest GPA (Marasca et al., 2021) and lower perceived school pressure (Abreu et al., 2023) or that Vulnerable students tend to experience faster declines in GPA (Dileo et al., 2022). Also, non-significant comparisons were spotted between mental health groups for academic outcomes (e.g., Renshaw et al., 2016). Results about supportive relationships, higher perceived affection, and lower hostility tend to be greatly reported by the positive/complete mental health group, more than the other groups (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010; González et al., 2023; King et al., 2021; Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Monteiro et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Mixed methods evidence highlighted that family support is significant for the Complete Mental Health group (Suldo et al., 2014). Moreover, results suggested that the Symptomatic but Content group reveals a more similar pattern to the Complete Mental Health group than the Vulnerable or the Troubled groups (Antaramian et al., 2010; Grych et al., 2020; Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Renshaw & Cohen, 2014). Other authors suggested that the Vulnerable group scores lowest on supportive relationships (Petersen et al., 2020). Furthermore, positive relationships are an essential protective factor of positive mental health trajectories. Positive relationships with teachers or family allow flourishing students to maintain their status and Vulnerable or Symptomatic but Content students to move to a flourishing status. However, this was not true for Troubled students (Kelly et al., 2012). In line with these findings, evidence also suggested that the highest levels of psychological assets (such as gratitude, hope, and emotional regulation) are reported by Complete/Positive Mental Health groups (e.g., Clark & Malecki, 2022; Eklund et al., 2011; Grych et al., 2020; Jefferies et al., 2023; Petrillo et al., 2015). Additionally, findings from the reviewed studies suggest that positive mental health groups presented more excellent perceived physical health than the other groups, followed by the symptomatic-yet-content group (Renshaw & Cohen, 2014; Suldo & Shaffer, 2008; Suldo et al., 2016). Also, flourishing people seem likelier to follow physical activity rules than languishing groups (Weatherson et al., 2020). On the other hand, the complete mental illness group has worse self-reported health and more difficulties in their physical functioning (Jiang, & Lu, 2019). Furthermore, sociodemographic data was also found to be related to mental health status. Specifically, gender, age, socioeconomic status, and racial identity or ethnicity were explored, but non-consistent findings were observed in this review (e.g., Clark & Malecki, 2022; Kassis et al., 2022; Rose et al., 2017; Weatherson et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2017). Regarding gender differences, some evidence suggests that females were significantly more likely to be at risk (Bersia et al., 2022; Eriksson & Stattin, 2023a; Matos et al., 2023), being part of the profiles with high symptoms (i.e., Symptomatic but Content or Troubled) (Clark & Malecki, 2022; Eriksson & Stattin, 2023b; Rose et al., 2017; Weatherson et al., 2020) and males on the adjusted groups (Clark & Malecki, 2022; Rizzo & Góngora, 2022), while other authors revealed that more females than males were in the resilient group compared to the non-resilient group (Kassis et al., 2022), and more males were in the Troubled and Symptomatic but content groups compared to females (Xiong et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2023). Moreover, a diversity of results was found on age differences. On the one hand, older adults with higher education, income, better cognitive function, and employment seem likelier to belong to the Complete Mental Health group (Jiang & Lu, 2019; Jiang et al., 2023) and less likely to belong to the Troubled group (Xu et al., 2023). On the other hand, older adults seem less likely to belong to the Complete Mental Health group or the Complete Mental Illness group, given that they are more likely to belong to the Moderate Mental Health group (Westerhof & Keyes, 2010). Furthermore, with samples of children/adolescents, evidence suggests that older young people are more likely to be part of the Symptomatic but Content group than the Positive Mental Health group (Rose et al., 2017) or the Languishing/high depressive symptoms group (Weatherson et al., 2020). Regarding the ethnicity, also non-consistent findings were observed. Some authors found that adolescents identifying as Black or Hispanic were significantly more likely to belong to the Complete Mental Health group than White adolescents (Clark & Malecki, 2022), while others suggest that White young people are more likely to be part of the Flourishing/low depressive symptoms group compared to other ethnic groups (e.g., Black, Asian, Hispanic) (Weatherson et al., 2020). Furthermore, socioeconomic risk factors were also identified in samples of children and/or adolescents. Some findings suggested that adolescents from lower SES are more likely to be in the mental health groups with high symptoms (i.e., Symptomatic but Content and Troubled groups) (Clark & Malecki, 2022). Also, below-average SES families are more likely to belong to the Vulnerable group and less to the Symptomatic but Content group (Xiong et al., 2017). Finally, other studies revealed no significant associations between mental health groups and socioeconomic status, migration, or ethnicity (Kassis et al., 2022; Rose et al., 2017). Reviewed studies revealed other individual characteristics, such as personality and locus of control. Evidence revealed that well-adjusted and at-risk individuals (the groups scoring low on symptoms) showed lower difficulties in their locus of control (Eklund et al., 2011). Moreover, personality traits such as conscientiousness, humanity, sprightliness, integrity, serenity, moderation, and not being overly nervous or fearful are associated with a more positive, flourishing, and complete mental health status (de la Iglesia et al., 2019; Farahani et al., 2019; Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001). Furthermore, evidence suggests that the Symptomatic but Content group had the highest conscientiousness scores (Farahani et al., 2019) and greater scores on humanity (de la Iglesia et al., 2019). Finally, extraversion and neuroticism (Lyons et al., 2012), and higher trait worry, psychological inflexibility, and dysfunctional perfectionism were significantly associated with Troubled and Symptomatic but Content groups (González et al., 2023). Lastly, stressful events were explored in three studies, and results revealed that the Troubled group reported higher stressful events and adversity (Grych et al., 2020; Lyons et al., 2012), namely when compared with the Vulnerable group (Zhang et al., 2021), and that Positive Mental Health group scored lower on perceived work stress (Zhang et al., 2021). This systematic review aims to summarize evidence about dual-factor models in terms of psychometrics and the variables associated with different groups of mental health status. Regarding the first aim, most of the studies reviewed (87.5%) provided factorial evidence supporting the dual-factor model of mental health, revealing two independent but related factors: well-being and psychopathology. These results highlight that the mental health conceptualization should include these two dimensions, which are independent but related rather than just one dimension. This approach has important implications for assessment and intervention, given that the absence of psychopathology cannot be interpreted as the presence of well-being (Greenspoon & Saklofske, 2001; Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017). While assessing and intervening in psychopathology is critical, promoting well-being is also pressing. It is less expensive than treating psychopathology, and the literature suggests that well-being improves other domains of an individual’s functioning, such as physical health, positive relationships, job performance, and satisfaction (Howell et al., 2016). Furthermore, fostering academic performance of young people requires both the presence of well-being and the lack of psychopathology (Antaramian, 2015). As such, important implications for practices in school contexts could be identified. Interventions at school should include universal and systemic programs that emphasize children’s strengths and assets (Antaramian et al., 2010), which in turn improve subjective and psychological well-being and might facilitate students’ engagement and academic success (Antaramian, 2015). Specifically, single or multiple components programs are effective in improving children’s well-being at school, namely those focused on components such as character strengths, positive emotions, or mindfulness (Oliveira et al., 2022). Moreover, interventions focused on two components (such as hope and gratitude) are effective in improving subjective well-being and reducing psychopathology (Kwok et al., 2016). In sum, the school context might benefit from interventions that promote students’ competencies and a positive relational school environment (i.e., between staff, teachers, and students) (Antaramian et al., 2010), which impact both students’ well-being and psychopathology. Despite this factorial evidence of the dual-factor model, three studies published in 2023 (Abdel-Khalek, 2023; Schürmann-Vengels et al., 2023; Zhao & Tay, 2023) suggest that bipolar models may better represent the mental health construct compared to the dual model, which suggests that testing the psychometric evidence of the dual-factor models has been receiving particular attention in recent years. This new paradigm is even more critical as significant evidence was reported in this manuscript focused on the diversity of mental health status groups. Although different authors labeled the groups with different designations, the combination of the two dimensions of well-being and psychopathology has resulted mainly in the following four groups: a) Complete/Positive Mental Health (high well-being and low psychopathology), b) Symptomatic but Content (high well-being and high psychopathology), c) Vulnerable (low well-being and low psychopathology), and d) Troubled (low well-being and high psychopathology) (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010; Brailovskaia et al., 2022). Mainly, the studies suggested that most participants belong to the adaptive group of positive mental health, except for at-risk groups (e.g., patients or young people in residential care) (Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; Teismann et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023). The results from at-risk samples suggest that, although these groups have more participants in the Troubled group (as theoretically expected), some have positive mental health (e.g., around 20%-30%), highlighting that resilience and positive adaptation are possible despite the risk. These results stress the complexity of mental health status, suggesting that psychological health and adaptation can occur, despite adversity, depending on the dynamic constellation of risk and protective factors (Grych et al., 2015). These findings offer important clinical implications for professionals working with at-risk populations (victims of violence or other life stressors) as this evidence disputes the perspective of “unavoidable harm” and the necessarily negative impact of risk and violence on mental health. Clinical observations and mental health measurements should be sufficiently inclusive to provide a more comprehensive picture of psychological functioning beyond psychological difficulties or disorders. Another relevant finding of this review is that a non-negligible percentage of subjects belong to the two typically neglected mental health groups: The Symptomatic but Content group (around 10%-30%) and the Vulnerable group (around 5%-30%) (e.g., Brailovskaia et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2021). This finding suggests that even if people may show great psychopathology, they may also show high levels of well-being. As such, incorporating strategies focused on fostering well-being outcomes when implementing interventions to reduce psychopathology might catalyze the success of these interventions (Howell et al., 2016). Moreover, people who do not show significant psychopathology do not necessarily present positive mental health, which requires additional efforts to foster well-being outcomes given that it is associated with other positive indicators of adjustment (better health, quality of life, longevity, workplace engagement) and lower costs associated with health care systems (Howell et al., 2016). Regarding the dimensions explored in these studies, they were primarily focused on school-related outcomes. These studies revealed that different mental health groups perform differently on school-related variables. Specifically, there is consistent evidence that the Positive Complete Mental Health health group reveals the highest levels of academic performance and engagement (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010; Moore et al., 2019b), and the Troubled group showed the worst results (e.g., Dileo et al., 2022; King et al., 2021). Furthermore, the Symptomatic but Content group tends to show results more similar to the Complete Mental Health group than, for instance, the Troubled group, in terms of school pressure (e.g., Abreu et al., 2023), sense of school belonging (e.g., Moffa et al., 2016), or online learning indicators (e.g., Kim et al., 2022), and the Vulnerable group shows results closer to the Troubled group, namely in terms of students engagement (e.g., Antaramian et al., 2010), GPA (e.g., Dileo et al., 2022) or online learning indicators (e.g., Kim et al., 2022). This evidence proposes that positive well-being together with the absence of psychopathology is particularly positively linked with academic performance and success (Antaramian, 2015). Moreover, while some authors revealed that lower well-being is a risk factor for academic engagement across time (Dileo et al., 2022), others suggest that well-being is not a protective factor for academic performance, given that the Symptomatic but Content group revealed the lowest GPA (Marasca et al., 2021). This inconsistency may suggest that different patterns of associations between mental health and academic performance might emerge when cross-sectional and longitudinal designs are implemented. Furthermore, supportive relationships were also explored, and the positive/complete mental health group consistently reported higher levels of support than the other groups (e.g., Magalhães & Calheiros, 2017; King et al., 2021). Also, the Symptomatic but Content group reveals a more similar pattern to the Complete Mental Health group than the other groups (e.g., Grych et al., 2020; Renshaw & Cohen, 2014), which suggests that even when there are high psychopathology, supportive relationships might provide a protective context to enhance individuals’ well-being. Having secure, close, and helpful relationships is protective of mental health outcomes, and for this reason, regardless of whether people show significant psychopathology, the quality of the relationships in different contexts (formal or informal) are enhancers of well-being. This finding is theoretically expected given that when people feel valued and supported, their self-esteem and self-acceptance may be fostered, and adaptive coping strategies tend to be selected, which enable them to deal effectively with challenges and stressful events (Ferreira et al., 2020; Wills & Shinar, 2000). Finally, individual variables, such as sociodemographic characteristics, psychological assets, individual attributes, physical health, and stressful events, were less explored. Non-consistent sociodemographic findings (i.e., gender, age, socioeconomic status, and racial identity or ethnicity) require additional evidence to identify the specific role of intra-individual and demographic variables as precursors or moderators of mental health outcomes. Similarly, research based on the dual-factor model should include samples of young people and adults in vulnerable circumstances (such as those who experience violence or stressful events), focusing on the role of trauma and stressful experiences in those different mental health groups. This approach highlights a new understanding of the complexity of mental health trajectories and outcomes following trauma and violence. Despite the theoretical and empirical contributions of this review, such as the psychometric evidence about the dual-factor models and the identification of different groups and profiles that inform research and intervention on mental health, this review still has some limitations. First, the methodological quality of reviewed studies was not analyzed, and second, the risk of bias of the included studies was not included. For this reason, the results presented here should be carefully analyzed in the light of these limitations. However, the studies have been presented in detail to allow the reader to critically analyze the evidence obtained. As such, some implications for research and professional practice will be detailed below. Implications for Research and Practice Most reviewed studies were developed in North America and Europe, which unveils the need for further cross-cultural evidence on this topic, including developing countries or regions. Different stressors can undermine mental health and these stressors might vary cross-culturally. For that reason, obtaining evidence on culturally specific and non-specific factors related to the dual-factor model can inform the literature from a theoretical and empirical point of view. Additionally, most of the studies included samples of children and/or adolescents, which calls for further research involving samples of adults and adopting longitudinal designs (for instance, from adolescence to adulthood). Longitudinal designs might enable us to understand causal relationships between the variables under study (e.g., academic outcomes) and mental health. Similarly, given the results of longitudinal studies here reviewed, which suggest that mental health groups seem to progress differently over time, further studies are needed to understand this progress over a broader life span (e.g., from childhood, adolescence to adulthood). These studies might provide further evidence on the critical development turning points, as well as the identification of protective and risk factors involved in these trajectories. Also, the studies have been focused mainly on academic or school-related outcomes, which reveals a vast field of research to test dual-factor models in other contexts and with different samples of young people and adults. More evidence is needed with groups of children and adults in such a particularly vulnerable condition in terms of mental health, such as victims of violence or crime, minority groups (e.g. LGBTIQA+), or children and young people in the judicial and child protection systems. This evidence could contribute to a mental health conceptualization in these groups that goes beyond the classic view of mental illness, psychopathology, and deficits. Regarding the classification methods, most of the reviewed studies have applied a cut score approach; however, there is evidence suggesting differences based on the classification approach – cut score versus latent profiles (Thayer et al., 2021). For instance, some authors suggested that the cut-score approach was more likely to identify the extreme groups (i.e., the Complete Mental Health and Troubled) while the latent profile analysis was more likely to identify the middle groups (i.e., the Symptomatic but Content and Vulnerable) (Thayer et al., 2021). This evidence requires further insights into the advantages and disadvantages of these different methodological approaches, through the implementation of studies that might simultaneously test different classification methods. In addition to these implications for future research on dual-factor models, this systematic review provided insightful implications for practice. Developing and implementing psychosocial interventions based on the specific needs of different groups is critical rather than based on a classical one-dimensional view of mental health. Interventions aimed at fostering psychological health must go beyond reducing symptoms. Investing in fostering well-being has several advantages: well-being-related interventions might be associated with improvements in physical health or psychological disorders and symptoms, which can help other interventions work better (Howell et al., 2016). Practitioners could include these interventions regularly to improve individuals’ mental health outcomes (Antaramian, 2015). Conflict of Interest The author of this article declares no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Inês Chim for her support in the final revision of the paper and Micaela Pinheiro for her support in the coscreening process. Cite this article as: Magalhães, E. (2024). Dual-factor models of mental health: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 89-102. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a6 Supplementary Data Supplementary data are available at https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a6 |

Cite this article as: Magalhães, E. (2024). Dual-factor Models of Mental Health: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence. Psychosocial Intervention, 33(2), 89 - 102. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2024a6

Correspondence: Eunice_magalhaes@iscte-iul.pt (E. Magalhães).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB Supplementary files

Supplementary files CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS