Cognitive Distortions and Decision-Making in Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review

Marta Badenes-Sastre1, 2, Patricia Medinilla-Tena1, 2, Chelsea M. Spencer3, Francisca Expósito1, and 2

1Mind, Brain, and Behavior Research Center (CIMCYC); University of Granada, Spain; 2University of Granada, Spain; 3Kansas State University, USA

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a3

Received 24 July 2024, Accepted 4 November 2024

Abstract

Objective: Exposing women to intimate partner violence (IPV) poses a risk to their physical and mental health, necessitating that they leave the relationship. However, women face various obstacles in doing so, such as cognitive distortions that affect their interpretation of the reality of violence, trapping them and significantly influencing their decision to leave. This scoping review explores, synthesizes, and analyzes the available evidence on the relationship between cognitive distortions and decision-making among women involved in IPV. Method: A systematic search was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines, utilizing the Web of Science, Scopus, and ProQuest databases. A total of 12 studies (five qualitative, four quantitative, and three mixed methodology) were included according to the inclusion criteria. Results: Self-blame, low attribution of responsibility to the aggressor, minimization of violence or damage, normalization of IPV, denial/loss of self, denial injury, control perceived, hope of change, savior beliefs, “should” belief in the relationship, focus on positive aspects of the relationship or aggressor, and denial other emotional options besides the partner were the main cognitive distortions found in women victims of IPV and related to maintaining IPV. Conclusions: These findings highlight the importance of recognizing and addressing cognitive distortions in women, which is crucial in preventing them from becoming trapped in violent relationships. Future research should continue to investigate the role of cognitive distortions in women’s decision-making regarding IPV, as well as the consequences of leaving the aggressor for them.

Keywords

Intimate partner violence, Cognitive distortions, Decision-making, Scoping reviewCite this article as: Badenes-Sastre, M., Medinilla-Tena, P., Spencer, C. M., & Expósito, F. (2025). Cognitive Distortions and Decision-Making in Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(1), 23 - 35. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a3

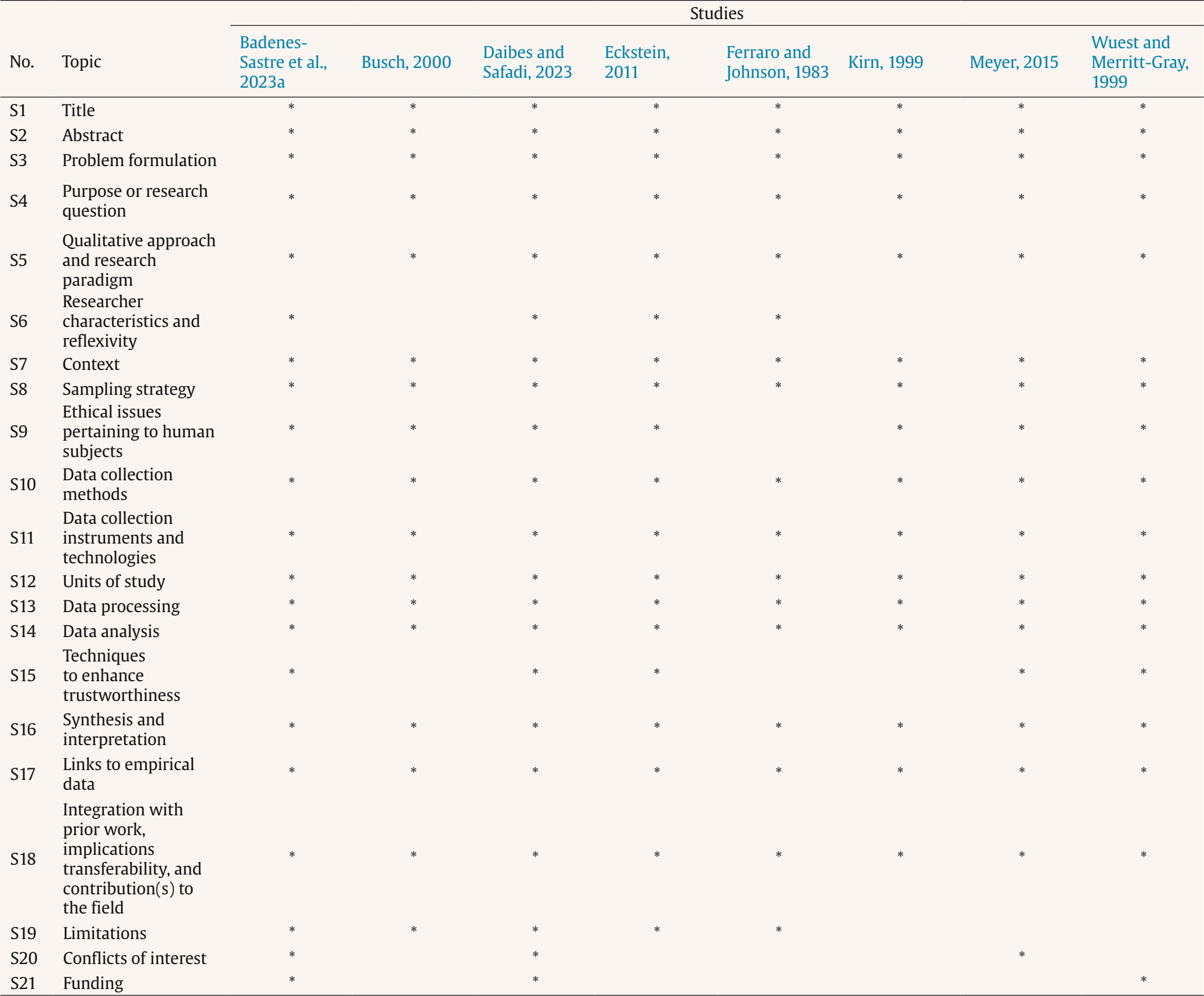

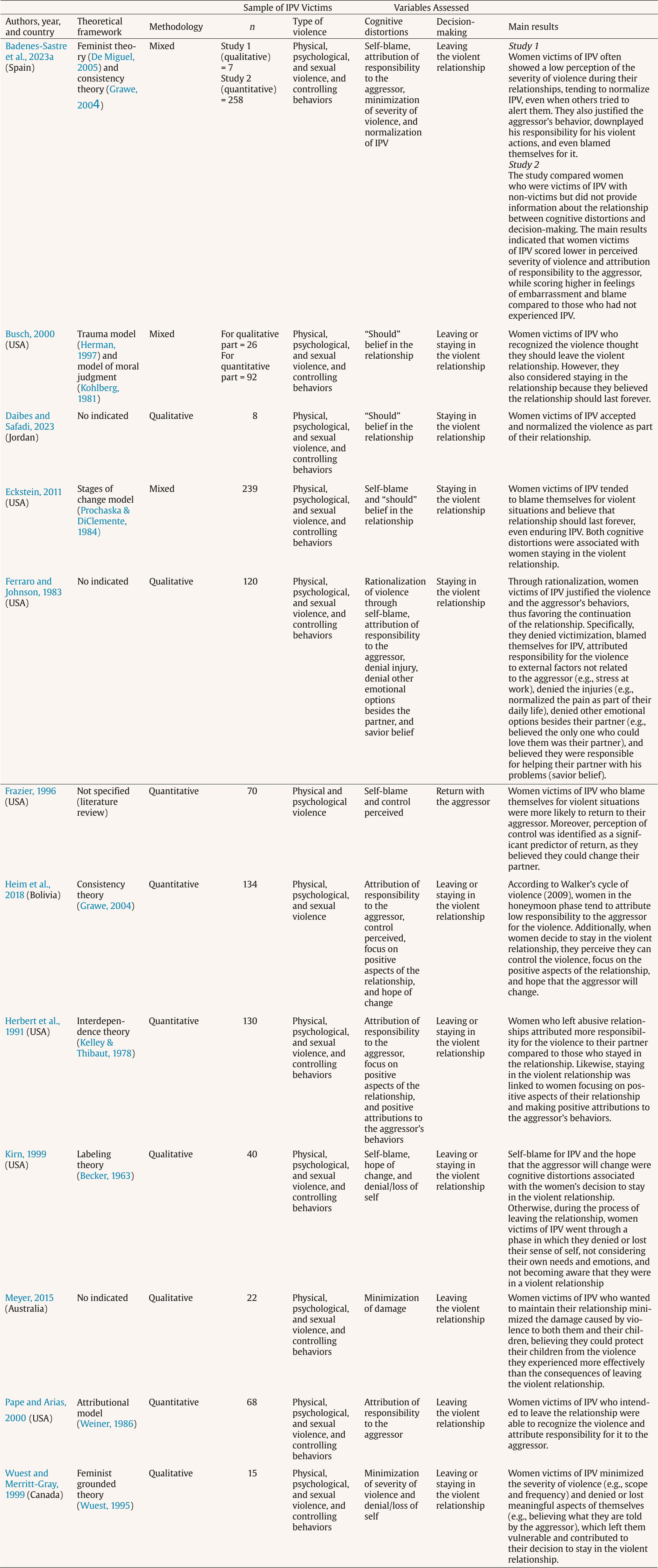

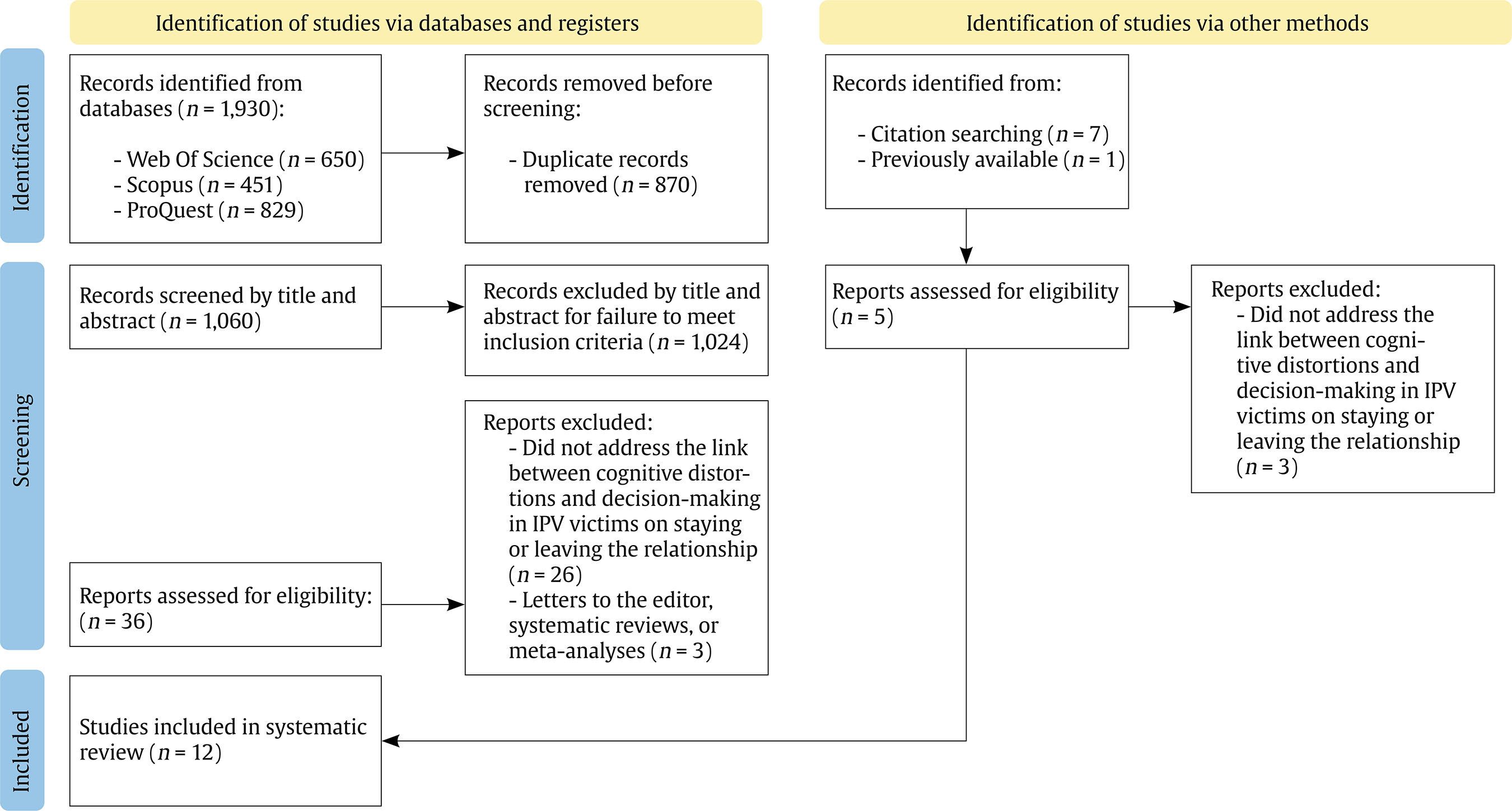

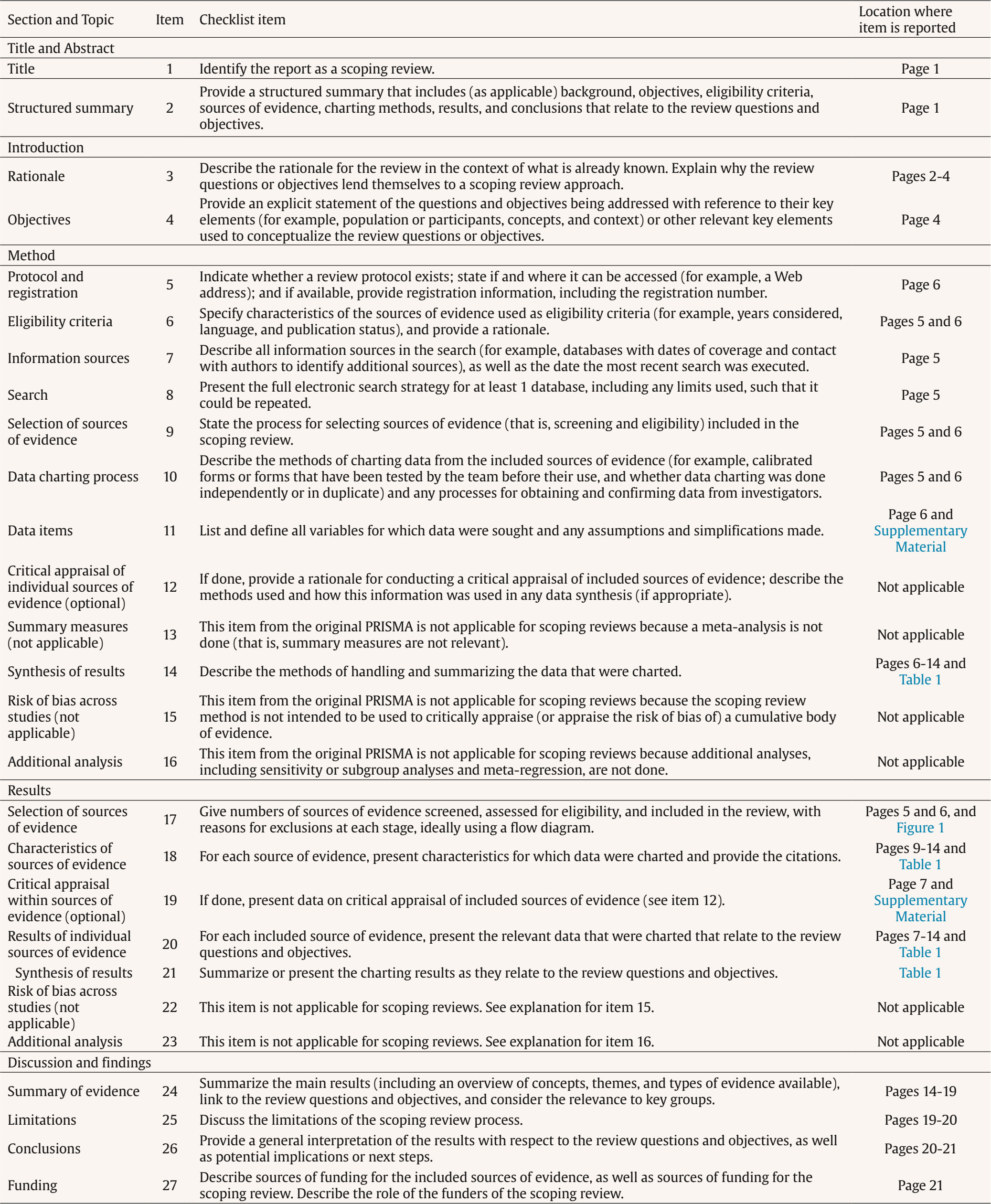

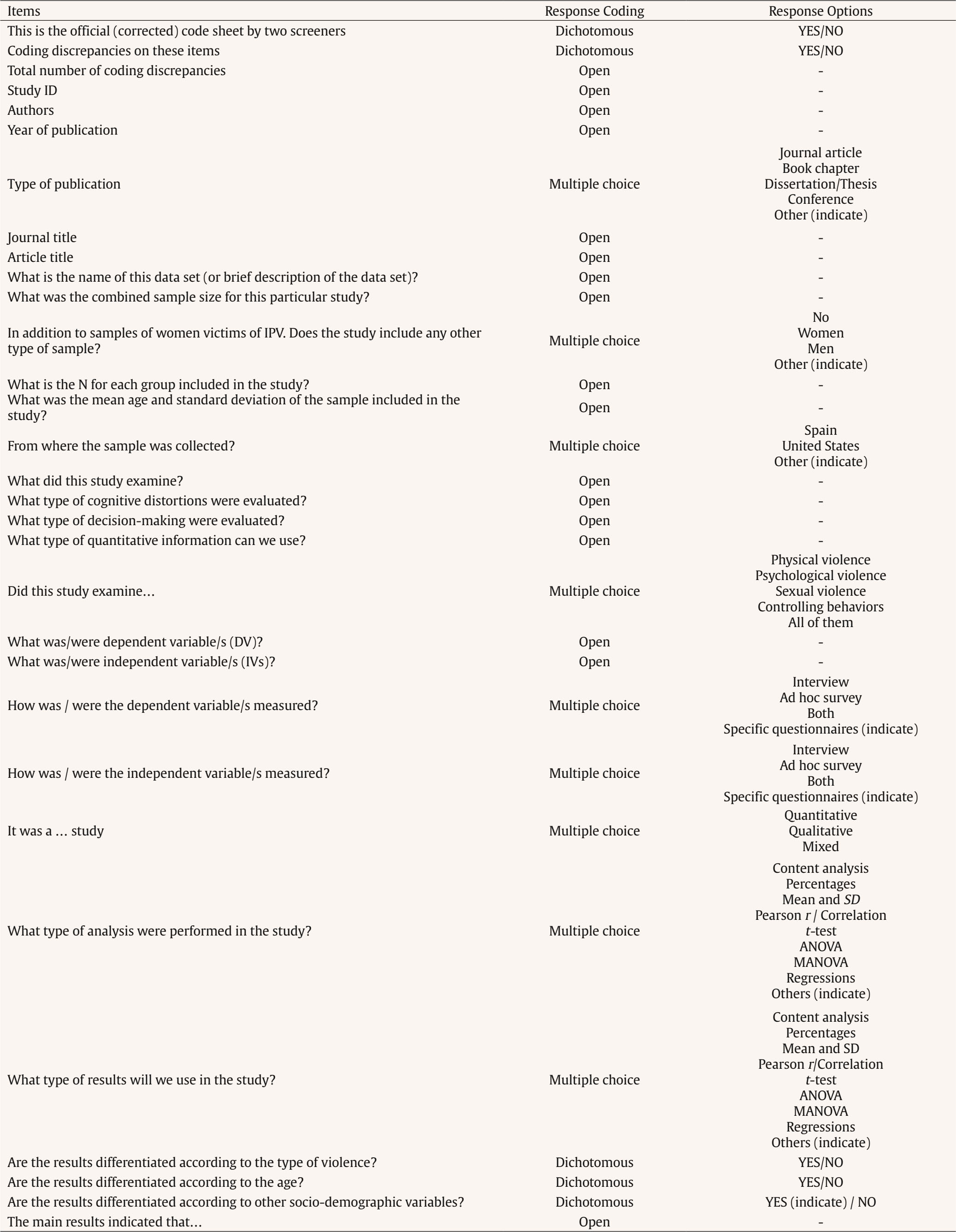

Correspondence: patmedten@ugr.es (P. Medinilla-Tena).Cognitive distortions are unique thought patterns that reflect distorted or unrealistic interpretations, resulting from an erroneous processing of reality (Beck, 1963, 2012). These dysfunctional distortions usually appear in stressful situations (Beck, 2012), such as intimate partner violence (IPV) against women. In this regard, women involved in violent relationships might feel unpleasant about forgiving their partner or staying in the relationship when they believe their partner is abusing them and causing them intentional harm (Gilbert & Gordon, 2017). According to Festinger’s (1957) cognitive dissonance theory, when people have conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or feelings about a situation, it creates an internal dissonance that causes discomfort. As a result, they may change their thoughts to reduce this discomfort, leading to the emergence of dysfunctional cognitive distortions. In situations of IPV, the imbalance between the victims’ thoughts and actions would lead them to reassess and change their negative thoughts about the aggressor and the violent situation in order to find balance and maintain their commitment to the relationship (Nicholson & Lutz, 2017). The distortion of reality in situations involving violence can pose a risk to women and could result in fatal consequences for them (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). Particularly, IPV affects women globally and includes any intentional behavior that harms them physically (e.g., being hit), psychologically (e.g., humiliation), or sexually (e.g., forced sex), as well as controlling behaviors (e.g., restricting contact with others) by a current or former partner (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Machancoses, et al., 2023; World Health Organization [WHO, 2024]). Women’s exposure to IPV has serious consequences for their health and wellbeing, leading to injuries, unintended pregnancy, sleep difficulties, depression, anxiety, and even fatal consequences such as homicide or suicide (WHO, 2024). Unfortunately, around 30% of women in the world suffer the consequences of IPV (Spanish Ministry of Equality, 2020; WHO, 2024), requiring women to identify the violence and make decisions in favor of their well-being and safety. Decision-Making in Violent Relationships Breaking up with an intimate partner is one of the most difficult decisions people can face (Garrido-Macías et al., 2017), especially if the relationship involves IPV. In this sense, victims of IPV often make several attempts before leaving the violent relationship (Anderson & Saunders, 2003; Zapor et al., 2018). Behind these unsuccessful attempts to leave the aggressor, victims may experience cognitive dissonance, that is, a discomfort that occurs when beliefs or/and actions conflict (Festinger, 1975; Nicholson & Lutz, 2017). For example, understanding that their partners, who claim to love them, are capable of intentionally subjugating and harming them, is not an easy task due to the influences of an androcentric culture (Badenes-Sastre, 2023). In coping with these dissonances, women might use cognitive distortions, such as minimizing the severity of or denying the violence, to maintain the relationship (Gilbert & Gordon, 2017; Pijlman et al., 2023). Hence, cognitive distortions affect women’s interpretation of the reality of the violence, entrapping them and significantly influencing their decision to break away from violence (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Heim et al., 2018). According to Rhatigan et al. (2006), women would use cognitive distortions, such as minimization or justification of violence to eliminate or diminish the internal conflict between their thoughts (e.g., “He is violent and I do not deserve this”) and their behaviors (e.g., “Despite what I think, I stay in the relationship”). Along these lines, the results found in the review indicated that women showed more intention to leave the relationship when they made realistic attributions of an aggressor’s responsibility compared to when they blamed themselves or exonerated the aggressor (Rhatigan et al., 2006). In addition, it appears that women’s perception of the increased severity and frequency of violence predicted their intentions to end the relationship (Pape & Arias, 2000), highlighting the need to address cognitive distortions that trap women in IPV and prevent them from recognizing the dangerous reality they are in. In this regard, numerous studies (Anderson & Saunders, 2003; Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Baldry & Cinquegrana, 2021; Barrios et al., 2021; Cravens et al., 2015; Heim et al., 2018; Pape & Arias, 2000) have focused on exploring the reasons why women stay in or leave an abusive relationship, including external variables (e.g., income or social support), relational variables (e.g., dependency or commitment), or individual variables (e.g., risk or severity perception). Regarding the individual variables, cognitive distortions could play an important role in violent relationships as women re-evaluate the situation to be consistent with their decision to stay in it (Nicholson & Lutz, 2017), putting themselves at risk. However, despite the relevance of cognitive distortions in women’s decision to stay in a violent relationship, to the best of our knowledge there are few studies that address this relationship in depth. Furthermore, as far as we know no study has compiled and synthesized the main cognitive distortions involved in women’s decision-making process regarding whether to leave or stay in a violent relationship, highlighting the need for further research. The Current Study Considering the aforementioned and following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018; see Supplementary Material), the present study consists of a scoping review aimed at exploring the available evidence of the relationship between cognitive distortions and decision-making among women involved in IPV. Specifically, the research questions that guided this study were: a) what the main cognitive distortions are in women victims of IPV when making decisions to leave or stay in a violent relationship and b) how these cognitive distortions relate to the decision to leave or stay in a relationship. Search Strategy To address our research questions, in January 2024 we conducted a comprehensive search using the databases Web of Science, SCOPUS and ProQuest, without temporal limitations, and filtered by abstract. The search formula included: (“cognitive distortion*” OR “cognitive error*” OR “distorted cognition*” OR “mind reading” OR overgeneralization OR minimization OR magnification OR “emotional reasoning” OR “fortune telling” OR “dichotomous thinking” OR “disqualifying the positive” OR “discounting positives” OR catastrophizing OR personalization OR labeling OR “should statements” OR “arbitrary interpretation” OR “selective abstraction” OR “mind reading” OR “jump* to conclusions” OR blaming OR “what if” OR “unfair comparisons”) AND (“decision*” OR “decision-making” OR “deciding” OR “resolution” OR “resolve”) AND (“intimate partner violence against wom*” OR “violence against wom*” OR “gender violence” OR “gender-based violence” OR violence OR aggression OR abuse OR “domestic violence” OR maltreatment OR batter* OR “dating violence” OR “partner violence” OR “spouse abuse”). Following the references included in the articles obtained from the database search, an additional manual screening was performed. Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection Studies were considered eligible if they met specific inclusion criteria: a) explored the relationship between cognitive distortions and women IPV victims’ decision-making regarding whether to stay in or leave the relationship, b) were written in English or Spanish, and c) did not include letters to the editor, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded from the study. The initial database search revealed 1,930 studies, of which 870 were duplicates, resulting in 1,060 documents for review. In addition, the manual search identified eight more articles to include. In total, 1,068 articles were included in the study for review. The first round of screening involved reviewing the articles by title and abstract, removing a total of 1,027 studies that did not meet the eligibility criteria, that is, did not provide information on the relation between cognitive distortions and decision-making regarding leaving or staying in IPV. Subsequently, a second full-text screening of 41 documents was conducted. Finally, 12 were included in the scoping review (see the selection process PRISMA flow in Figure 1). Data Extraction and Analysis We preregistered the study in the Open Society Foundations (OSF) like Generalized Systematic Review Registration (osf.io/nsuab). Data extraction and analysis of the studies were performed by three screeners. Specifically, two researchers (P.M. and M.B.) analyzed the documents independently, resolving discrepancies with a third researcher (C.S.) by consensus. The data extraction process consisted of two phases. In phase 1, the studies were analyzed by title and abstract, excluding those that did not meet the inclusion criteria. In phase 2, the studies resulting from phase 1 were read in full text, and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were eliminated. Finally, to analyze the final studies that meet the inclusion criteria, the researchers recorded the data on a coding protocol, which was previously systematized. Specifically, the data gathered comprised the authors, year of publication, type of publication, journal information, study title, characteristics of sample, purpose of the study, type of analysis (quantitative or qualitative), type of violence, instruments, cognitive distortions assessed, type of decisions, the relation between cognitive distortions in victims of IPV and decision-making (leaving/staying in the violent relationship), as well as the main results of the study (see Supplementary Material). Finally, according to Fleiss et al. (2013), to consider an inter-coder agreement index adequate the values should be ranged between .80 and 1. In this study, an adequate intercoder reliability (κ = .80) was obtained for the final studies included in the scoping review, with a final complete agreement among authors. Methodological Quality Assessment To evaluate the methodological quality of each of the studies included in the scoping review, the Cambridge Quality Checklist (Murray et al., 2009) was applied to quantitative studies (see Table 1), while the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR; O’Brien et al., 2014) was applied to qualitative (see Table 2). The mixed-design studies included in this review were assessed using both quality assessments to ensure a comprehensive evaluation. Table 1 The Cambridge Quality Checklists for Quantitative Studies   Note. Correlate score: 0 = study feature not present, or not known; 1 = study feature present; risk factors: X = type of data provided by the study. Table 2 The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research   Note. Correlate score: *study feature present, absence of * = study feature not present, or not known; No = number; Sx = code of item. Of the seven included quantitative studies (of which three are mixed design), five studies (71.42%) were classified as high quality and two (28.57%) as moderate quality based on the Cambridge Quality Checklist criteria. The higher quality studies tended to meet criteria related to sampling method, response rates, measurement of correlates, and measurement of outcome, while the moderate quality studies fell short in sample size. On the other hand, of the eight qualitative studies (including three of mixed design), all followed the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research to varying extents. However, four studies (50%) omitted information on researcher characteristics and reflexivity, and three (37.5%) did not describe the techniques to enhance trustworthiness. A total of 12 studies were included in the scoping review. The search did not include a temporal filter, resulting in studies published between 1983-2023. Only 16.66% of them were published in the last 5 years. Regarding the methodology employed, five studies used qualitative methods, four studies quantitative methods, and three studies mixed methods, combining qualitative and quantitative methodologies. In qualitative studies, open or semi-structured interviews were mainly used (Daibes & Safadi, 2023; Ferraro & Johnson, 1983; Kirn, 1999; Meyer, 2015; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). In quantitative studies (Frazier, 1996; Heim et al., 2018; Herbert et al., 1991; Pape & Arias, 2000), data were collected through standardized measures and ad hoc surveys. Finally, in mixed studies (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Busch, 2000; Eckstein, 2011), different methodologies were combined. The characteristics of studies that were included can be seen in Table 3. Table 3 Characteristics of Studies Included   Note. Mixed = include quantitative and qualitative methods; IPV = intimate partner violence Theoretical Framework Among the 12 articles reviewed, various theoretical frameworks were identified. On one hand, two studies (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999) were based on the Feminist Theory (De Miguel, 2005) and the Feminist Grounded Theory (Wuest, 1995) and two other studies (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Heim et al., 2018) were based on the Consistency Theory (Grawe, 2004). Particularly, the Feminist Theory (De Miguel, 2005) emphasizes patriarchal culture as a main cause of IPV, aiming to dismantle the various ways in which society legitimizes violence against women and to understand social perceptions and attitudes towards this violence (Bosch & Ferrer, 2000; De Miguel, 2005). Similarly, the Feminist Grounded Theory (Wuest, 1995) facilitates the analysis of the impact of the social context, allowing for the examination of the individual behavior of the women victim and her aggressor, as well as the interactions within the system’s structure (Wuest, 1995). The Consistency Theory (Grawe, 2004) proposes that IPV contradicts women’s motivational goals, leading to inconsistency and tension. To reduce this discomfort, women might leave the violent relationship or adjust their thoughts to align with staying in the violent relationship. Other studies were based on the Trauma Model (Herman, 1997), the Labeling Theory (Becker, 1963), the Stages of Change Model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984), the Interdependence Theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), the Attributional Model (Weiner, 1986), and the Model of Moral Judgment (Kohlberg, 1981). Otherwise, four studies (Daibes & Safadi, 2023; Ferraro & Johnson, 1983; Frazier, 1996; Meyer, 2015) did not base their objectives or interpret their results on any specific theory, although they do review literature or mention related theoretical concepts. The Trauma Model (Herman, 1997) highlights the impact of the trauma caused by exposure to IPV on women’s decision making to leave the relationship. In this sense, physical injuries, constant fear, persistent trauma, and violence contribute to a decrease in a victimized woman’s belief in her ability to control her situation, increasing feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. Similarly, the Labeling Theory (Becker, 1963) suggests that women may internalize their role as victims of IPV and feel trapped in violent relationships, thus hindering their ability to leave. The Stages of Change Model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984) considers five stages for decision-making: 1) precontemplation, 2) contemplation, 3) preparation, 4) action, and 5) maintenance. In the context of IPV, this model could explain the process of decision-making regarding what stage of change the victim is in (Khaw & Hardesty, 2009). Moreover, the Interdependence Theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978) explains that people evaluate costs and rewards within relationships; they will stay in an intimate relationship as long as it is at least acceptable and better than any available alternatives. The Attributional Model (Weiner, 1986) suggests that when individuals attribute their partner’s violent behaviors to stable and internal causes, they tend to anticipate continued violence in the future. Consequently, this fosters greater feelings of fear towards the partner and hopelessness regarding the possibility of the partner changing, thereby increasing their intentions to leave the violent relationships. Lastly, the Model of Moral Judgment (Kohlberg, 1981) is rooted in the development of moral reasoning in people, arguing that people’s moral judgment progresses through six stages where they determine what is right or wrong based on their perception of the situation, morals, and thoughts. Sample Characteristics The total sample of all studies included was 1,229 women who were victims of IPV. Regarding age, three studies did not indicate the mean age of participants and one study reported the mean age of participants mixed with a sample of other characteristics (non-victims of IPV). Therefore, the mean age of participants in the remaining studies (n = 8) was 36.02 years. Likewise, some studies informed about the educational level of participants (n = 9), and whether they had children (n = 6). On the contrary, three studies (Eckstein, 2011; Meyer, 2015; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999) did not present any sociodemographic information about the participants, such as educational level or marital status. Regarding the origin of the sample, most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 7) and the rest were conducted in Spain (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Bolivia (n = 1), Jordan (n = 1), and Australia (n = 1). The majority of studies examined physical IPV, psychological IPV, sexual IPV, and controlling behaviors. Only two studies did not include participants who were victims of controlling behaviors (Frazier, 1996; Heim et al., 2018) or sexual violence (Frazier, 1996) by their current or former partners. Main Cognitive Distortions in Women Victims of IPV The results obtained in this study showed that self-blame, low attribution of responsibility to the aggressor, minimization of violence or damage, normalization of IPV, denial/loss of self, denial of injury, perceived sense of control, hope of change, savior beliefs, “should” beliefs in the relationship, focus on positive aspects of the relationship or aggressor, and denial of other emotional options besides staying with the partner were the main cognitive distortions in women victims of IPV. Among the cognitive distortions found in the studies analyzed, self-blame was most frequently reported on, followed by low attribution of responsibility to the aggressor, and minimization of the severity or damage. Other cognitive distortions observed were normalization of IPV, denial/loss of self, denial injury, perceived sense of control, hope of change, savior beliefs, “should” belief in the relationship, focus on positive aspects of the relationship or aggressor, and denial of other emotional options besides staying with the partner. Self-blame refers to the victims’ interpretation of the situation, attributing the responsibility for what happened in the violent relationship to themselves (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Eckstein, 2011; Frazier, 1996; Kirn, 1999), even denying victimization itself, neutralizing the responsibility of the aggressor (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). Likewise, women generally attributed low responsibility to the aggressor for IPV, sometimes even completely denying their responsibility or attributing it to external factors affecting both the victims and aggressors (e.g., pressures at work, or legal problems; Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Ferraro & Johnson, 1983; Heim et al., 2018). On the contrary, two studies (Herbert et al., 1991; Pape & Arias, 2000) found that when women attributed responsibility to the aggressor, they perceived reality more accurately, which was associated with a higher probability of leaving the violent relationship. Similarly, minimization of the severity of violence or damage is characterized by treating experiences of violence as real, but insignificant (Dozois & Beck, 2008). In the context of IPV, women tend to underestimate the severity or damage caused by situations of violence (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Meyer, 2015; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Moreover, normalization of the IPV was another cognitive distortion wherein women perceived the violence as something normative within their relationship (Daibes & Safadi, 2023), thereby not correctly perceiving the severity of IPV (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). Additionally, women exhibited denial/loss of self as a survival strategy in the context of IPV, which involves sacrificing significant aspects of their identity crucial for their self-image (Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Women victims of IPV reported feeling like they had relinquished parts of themselves in situations of violence (Kirn, 1999; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). This denial contributed to victims to downplay the extent and frequency of the violence (Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Additionally, Ferraro and Johnson (1983) found that women could even deny the injuries suffered because IPV was far removed from their idealization of the relationship. Results also found that women had a false sense of internal control, believing that events depend on their behaviors and they could control IPV situations (Frazier, 1996; Heim et al., 2018). Along these lines, women also harbored hopes for change, meaning they anticipated positive outcomes by choosing to stay in the violent relationship, believing their partner would change (Kirn, 1999; Heim et al., 2018). Additionally, savior beliefs and “should” beliefs also emerged among women who have experienced IPV. Particularly, a savior belief refers to the tendency of women victims to believe that their partners depend on their care to survive (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). A “should” belief can include having a belief that marriage should be forever (Eckstein, 2011) and violence might be part of it (Daibes & Safadi, 2023), influencing decision-making based on individual values and cultural norms (Busch, 2000). Furthermore, instead of acknowledging the reality of IPV, women often focused on positive aspects of the relationship (e.g., “There is a great deal of love and affection expressed in our relationship”) and made positive attributions to an aggressor’s behaviors (e.g., “My partner is a loving, caring person”; Heim et al., 2018; Herbert et al., 1991). Finally, women may feel that they have no other emotional alternatives to provide love and affection, only to their partner (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). Relationship between Cognitive Distortions and Decision-Making According to the studies analyzed, self-blame in women victims of IPV was one of the main cognitive distortions contributing to them not leaving the violent relationship. Women who engaged in self-blame were more likely to stay in the violent relationship (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Eckstein, 2011; Ferraro & Johnson, 1983; Kim, 1999). In this regard, self-blame in victims was also associated with return to the aggressor (Frazier, 1996). Conversely, women who thought that they did not deserve to be abused and did not consider themselves responsible for IPV, tended to leave the violent relationship (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). Low attribution of responsibility to the aggressor was associated with higher probability to stay in the relationship, especially when women experienced the honeymoon phase according to Walker’s (2009) cycle of violence (see also, Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Heim et al., 2018; Herbert, 1991; Pape & Arias, 2000). Similarly, if women attributed greater responsibility to the aggressor, it increased the likelihood of leaving the violent relationship (Herbert et al., 1991; Pape & Arias, 2000). On the other hand, the attribution of IPV to external factors (e.g., stress at work) by women was associated with remaining in the violent relationship (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). An association was found between staying in the relationship and minimizing the severity of the violence or the harm caused by the aggressor (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Meyer, 2015; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Normalization of an aggressor’s violent behaviors made it difficult for women to end the violent relationship (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). In relation to the denial/loss of self, it is observed that losing or denying the sense of self, ceasing to consider their needs and emotions, led women to not recognize themselves as victims of violence (Kirn, 1999). This was a determining factor that led victims to stay in the violent relationship (Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Additionally, women began to internalize an aggressor’s perceptions about them, such as believing that they are useless (Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Similarly, the denial of injury led women to deny the impact received and normalized pain as part of their daily life, which again favored staying in the violent relationship (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). Women who were in the honeymoon phase of Walker’s (2009) cycle of violence tended to perceive greater control over the violence, which was related to staying in the abusive relationship (Heim et al., 2018). Moreover, this control was a significant predictor for returning to the aggressor because women thought they could change their partner (Frazier, 1996). In this line, women’s hope that the aggressor would change (Kirn, 1999), as well as savior beliefs—believing they have a responsibility to help their partner with their problems (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983)—were associated with staying in the violent relationship. Another cognitive distortion related to women’s decision to stay in the violent relationship was “should” beliefs, that suggested they “should” stay in the marriage no matter what (Busch, 2000; Daibes & Safadi, 2023; Eckstein, 2011), which led to victims normalizing IPV as part of a marriage that they “should” make work. Similarly, focusing on positive aspects of the relationship or positive traits of the aggressor and attributing good intentions to an aggressor’s behaviors was related to women staying in the relationship (Heim et al., 2018; Herbert et al., 1991). Lastly, denial of other emotional options besides the partner was tied to women victims of IPV staying in the violent relationship, leading them to believe that only their partner could love them and provide emotional support, despite the violence experienced (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). Understanding the difficulties women encounter when trying to leave violent relationships is crucial. Cognitive distortions pose an obstacle for women to perceive the reality of the violent relationship they are involved in, placing them at risk by continuing the relationship. Despite this, the literature on this topic is scarce, requiring a scoping review. To help fill the current gap in the literature, the present study aimed to explore, synthesize, and analyze the available information on the role of cognitive distortions in women’s decision-making processes to either leave or stay in violent relationships. Specifically, 12 studies were analyzed of which only two were published in the last 5 years, suggesting a continued need for research on this important topic. The analyzed studies showed methodological variety, with four studies using quantitative methods, five studies using qualitative methods, and three studies combining both quantitative and qualitative methods. Nevertheless, all fall within empirical research, aiming to address specific issues (Ato et al., 2013). Commonly, studies using quantitative methodology were predominantly conducted to investigate IPV. However, given the complexity of IPV, there has been a need for the development of qualitative studies that complement and contribute to understanding the phenomenon (Cormos et al., 2023; Gómez-Pulido et al., 2024) as recently explored from the perspective of the aggressors (Roldán et al., 2023). In this regard, the methodological heterogeneity of the studies included allows us to approach the constructs from different perspectives, compensating for the inherent weaknesses of each. Regarding the sample, information was collected from 1,229 women who experienced form of IPV victimization. Most of the studies included women victims of physical IPV, psychological IPV, sexual IPV, and controlling behaviors. Only two studies did not take controlling behaviors into account. Particularly, Frazier (1996) assessed women victims of only physical and psychological violence, while Heim et al. (2018) included victims of physical, psychological, and sexual violence. According to WHO (2024), IPV covers the four forms of violence against women (physical, psychological, sexual violence, and controlling behaviors) and impacts women worldwide. In this sense, the studies analyzed were conducted with women of diverse nationalities and other sociodemographic characteristics, predominantly highlighting American women. Other studies did not provide information about the characteristics of the participants, or did so sparingly, requiring attention because, in line with previous studies (Hien & Rugglass, 2009; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2024), demographic or socio-economic factors, such as lower levels of education, may influence IPV victims not to leave the violent relationship. Additionally, nearly all studies based their research on a theoretical framework. These frameworks included the Feminist Theory (De Miguel, 2005), the Feminist Grounded Theory (Wuest, 1995), the Trauma Model (Herman, 1997), the Labeling Theory (Becker, 1963), the Stages of Change Model (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984), the Interdependence Theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978), the Consistency Theory (Grawe, 2004), the Attributional Model (Weiner, 1986), and the Model of Moral Judgment (Kohlberg, 1981), that were employed to explain the role of cognitive distortions in the decision-making process of leaving or staying in a violent relationship by women victims of IPV. The results obtained in all of the studies draw similar conclusions, that is, several cognitive distortions (self-blame, attribution of responsibility to the aggressor, minimizations, normalization of IPV, denials, control perceived, hope of change, savior beliefs, “should” belief in the relationship, and focus on positive aspects) are obstacles for women leaving violent relationships. Finally, the findings obtained in this study address the main research questions: a) what are the main cognitive distortions in women victims of IPV when making decisions to leave or stay in a violent relationship? and b) how do these cognitive distortions relate to the decision to leave or stay in a relationship? Responding to the first question, the main cognitive distortions found in the literature available were self-blame, attribution of responsibility to the aggressor, minimizations, normalization of IPV, denials, control perceived, hope of change, savior beliefs, “should” belief in the relationship, and focus on positive aspects. Specifically, self-blame was the cognitive distortion that appeared most frequently among the studies analyzed. Self-blame in IPV victims mitigates an aggressor’s negative behaviors and prevents a woman from leaving the abusive relationship (Puente-Martínez et al., 2016). At the same time, this self-blame is often reinforced by aggressors, who also make sure to blame the victims (Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Subsequently, the attribution of responsibility to an aggressor appeared frequently in the literature (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023; Ferraro & Johnson, 1983; Heim et al., 2018; Herbert et al., 1991; Pape & Arias, 2000), making it difficult to leave violent relationships. These variables are negatively related, that is, the more the victims blame themselves for the violent events, the less responsibility they attribute to the aggressor (Badenes-Sastre. Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). Hence, it will be necessary to pay attention to how women attribute causality in cases of IPV, ensuring they do not internalize blame for violent situations that are not their responsibility, considering the influence of the sociocultural context in which they find themselves. Moreover, minimization of the severity or damage as well as denial injury were other significant cognitive distortions highlighted in the studies analyzed. This distorted reality could make it challenging for women to assess the level of danger they are in and make decisions to protect themselves (Badenes-Sastre & Expósito, 2021). To perceive the full severity of IPV, it is necessary to identify it in all its magnitude, including even the most subtle signs of violence (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). Likewise, when victims normalize IPV, they distort reality and contribute to staying in the relationship (Daibes & Safadi, 2023). They may recognize indicators of IPV but normalize them, constituting one of the main reasons for staying or returning to the violent relationship (Spanish Ministry of Equality, 2020). In this regard, social norms of acceptance of IPV would favor a context of tolerance and normality that would impact victims’ responses (Ferrer et al., 2020; Flood & Pease, 2009; Gracia et al., 2020). Therefore, IPV may be socially accepted in certain circumstances, leading to its normalization, and breaking away from this could be seen as irrational (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). At other times, because of exposure to IPV, women exhibit denial/loss of self, having sensations of renouncing to parts of themselves (Kirn, 1999; Wuest & Merritt-Gray, 1999). Otherwise, they perceive an internal sense of control, where they believe they can manage the IPV themselves (Frazier, 1996; Heim et al., 2018). Additionally, hope of change was a distorted cognition present in women victims of IPV (Kirn, 1999). In this case, women provide new opportunities to the aggressors and hold onto the hope that they will change. In this vein, women also exhibited savior beliefs, assuming control of the situation by thinking that the aggressor depends on their care and needs them (Ferraro & Johnson, 1983). This is very similar to the distorted belief about marriage where, wrongly, women thought that marriage “should” be forever (despite IPV), perceiving positive aspects of the relationship (e.g., “There is a great deal of love and affection expressed in our relationship”), attributing positive intentions to an aggressor’s behaviors (e.g., “My partner is a loving, caring person”), and denying other emotional options besides their partner (Eckstein, 2011; Ferraro & Johnson, 1983; Heim et al., 2018; Herbert et al., 1991). According to Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al. (2023), these cognitive distortions could be fostered by the gaslighting effect to which IPV victims are subjected. The gaslighting effect stems from a social gender inequality in which aggressors, abusing their power, emotionally manipulate women in the relationship, causing them to experience doubt, confusion, and a distortion of reality that makes it difficult for them to make the decision to break away from the violent relationship (Spear, 2019; Stern, 2019; Sweet, 2019). Women emphasize the relevance of the social context in which the process of leaving takes place to make a final decision (Anderson & Saunders, 2003). In this sense, a social implication is required, so, according to Lorente (2022), IPV is built on sociocultural references of inequality and power relations of men over women, who may perceive violence as a way to correct or punish those women in relationships who do not conform to the patriarchal social model. Findings regarding the second research question showed that cognitive distortions are an obstacle to leaving the violent relationship. In fact, women are more likely not to leave IPV when they a) blame themselves for the violence, b) attribute less responsibility to the aggressor for the violence, c) minimize the severity of the violence or the damage suffered, d) normalize IPV as part of marriage/relationship, e) deny/lose their sense of self, disregarding their needs or emotions and not recognizing themselves as victims, f) deny the injury or other emotional options beyond the aggressor, g) focus on positive aspects of the relationship or the aggressor, h) believe they must save their partner, or i) have hope for the change in the aggressor’s behavior or the violent relationship. Otherwise, Frazier (1996) pointed out that perceived internal control in victims of IPV as well as higher levels of self-blame were important predictors to return with the aggressor. In this sense, women can leave and return to the violent relationship repeatedly, each time acquiring new coping strategies (Anderson & Saunders, 2003). In line with Cravens et al. (2015), the decision-making process for women to leave or stay in a violent relationship is not a punctual event; rather, it entails a complex process that requires a turning point in thinking, reassessing the situation, recognizing the violence, and becoming aware of the danger they are in. They need to recognize that the situation will not change, that the aggressor is solely responsible, and that they need to recover their identity. To conclude, decision-making among women who are victims of IPV appears to be more complex compared to non-victims, as it is influenced by their lived experiences of violence. This necessitates understanding the process within the context of their victimization (Rhatigan et al., 2006). As observed in the present study, cognitive distortions in IPV victims play a differential and crucial role that needs to be addressed, as they are hindering women from leaving the violent relationship. It is important to highlight this because, although it might seem logical to think that the violation of rights and freedoms as a person by one’s partner are more than sufficient reasons to leave a violent relationship, the reality is very different. As noted, when women are exposed to IPV, they may become trapped and encounter numerous difficulties in leaving the relationship due to their distorted reality and external factors that normalize it (Badenes-Sastre, Lorente, Beltrán-Morillas, et al., 2023). Limitations and Future Research Directions This scoping review followed a rigorous methodology. However, some limitations should be considered. First, this study focused on studying the role of cognitive distortions in the decision to leave or maintain a violent relationship. However, decision-making is a process and IPV victims could have different phases before deciding to leave the relationship (Anderson & Saunders, 2003). In this regard, future studies could explore the role of cognitive distortions in other types of decision-making (e.g., seeking formal help or reporting the aggressor). These different decisions might be preliminary steps before definitively ending the relationship. Moreover, different instruments and methodologies found in the studies analyzed could affect the identification and measurement of the objective variables of this study. Given the importance of cognitive distortions in IPV victims when deciding to leave their partner, appropriate and validated assessment tools are needed to accurately identify these distortions. It allows us to enhance the quality and comparability of data obtained across different countries, thereby generalizing results. Lastly, including only studies written in English or Spanish was a limitation of this study because, although they are probably minimal, it restricts the results and prevents access to other potentially relevant literature. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study sets a starting point for future research and highlights the need for further study of cognitive distortions in IPV victims’ decision-making. In the context of IPV, considering the consequences of women’s decision to leave the violent relationship will be important because it increases the risk of being murdered due to aggressors perceiving that they no longer have control over women (Lorente et al., 2022; Spanish Ministry of Equality, 2020). In this case, women could perceive reality without cognitive distortions but would make the decision to stay in the relationship for fear of fatal consequences for them or their children. In fact, over 80% of women victims of IPV stated they continued to feel afraid of the aggressor despite having active police protection measures in place (Muñoz-Rivera et al., 2024). Ensuring the safety of IPV victims and their children, instead of questioning them for not leaving the perpetrator, will be crucial to facilitate women’s decision to leave the violent relationship without posing a greater risk to their lives. Finally, according to Araújo et al. (2023), future studies could consider the role of cognitive distortions in aggressors a way to prevent violence. This is the first study exploring the available literature about the role of cognitive distortions in the decision-making process by women regarding leaving or staying in a violent relationship. The results obtained in this study showed self-blame, low attribution of responsibility to the aggressor, minimization of violence or damage, normalization of IPV, denial/loss of self, denial injury, control perceived, hope of change, savior beliefs, “should” beliefs in the relationship focus on positive aspects of the relationship or aggressor and denial of other emotional options besides the partner as the main cognitive distortions related to maintaining a violent relationship in the analyzed literature. These findings highlight the importance of being aware of the invisible obstacles that IPV victims face when making decisions regarding leaving or staying in a violent relationship. Identifying cognitive distortions in women and addressing them will be essential to helping women make decisions on leaving or staying in abusive relationships. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Badenes-Sastre, M., Medinilla-Tena, P., Spencer, C. M., Expósito, F. (2025). Cognitive distortions and decision-making in women victims of intimate partner violence: A scoping review. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(1), 23-35. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a3 Funding This work was supported by a research project “Violence against women: Implications for their psychosocial wellbeing” (grant) PID2021-123125OB-100 financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. References |

Cite this article as: Badenes-Sastre, M., Medinilla-Tena, P., Spencer, C. M., & Expósito, F. (2025). Cognitive Distortions and Decision-Making in Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(1), 23 - 35. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a3

Correspondence: patmedten@ugr.es (P. Medinilla-Tena).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS