Optimizing Engagement: Factors Influencing Family Participation in a Positive Parenting Program among Vulnerable Households with Young Children

Hector Cebolla1, Juan Carlos Martín2, and María José Rodrigo3

1Instituto de EconomĂa, GeografĂa y DemografĂa, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones CientĂficas, Madrid, Spain; ; 2Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain; 3Instituto Universitario de Neurociencia (IUNE), Universidad de La Laguna, Campus de Guajara, Tenerife, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a5

Received 1 July 2024, Accepted 5 December 2024

Abstract

Objective: This paper addresses a critical gap in family research by examining the risk of families with young children receiving the Minimum Living Income (MLI) in rejecting targeted social interventions, also known as non-take-up (NTU). Method: We analyze recruting process data from the first invitation to participate in a social benefit including the “Growing Happily in the Family-2” program developed in Madrid, Spain, to their written consent prior to its implementation. Measurements of subjective factors reported as reasons for NTU and objective factors of sociodemographic characteristics and detailed household patterns of prior engagement with social services to study NTU response were based on official records and project data. Results: Descriptive findings reveal that jobless parents with high economic hardship, poorer physical and mental health, heavy demanding childbearing, and poor family-job conciliation aggravated by adverse life events profile the NTU response. Linear probability models predicting the rejection/acceptance decision showed that lack of previous contact with the social services, younger parental age, male, and nonimmigrant status significantly elevate NTU risk. Notably, although a longer stay in social services increases the probability of NTU, this does not occur among the most vulnerable families that have received more intensive support, challenging the idea of intervention fatigue. Conclusions: These findings have implications for the design of policies and practices to support children and family as subjects of rights, underlining the need for preventive and capacity-building strategies that address specific barriers to program uptake. Overall, the study highlights innovation areas that lie in the interception of social and employment benefits to improve the reach of the intended population and the positive impact of parenting interventions aimed at supporting vulnerable families.

Keywords

Non-take-up phenomenon, Subjective and objective factors, Minimum Living Income, Young parenting, Positive parenting programCite this article as: Cebolla, H., Martín, J. C., & Rodrigo, M. J. (2025). Optimizing Engagement: Factors Influencing Family Participation in a Positive Parenting Program among Vulnerable Households with Young Children. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(1), 53 - 62. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a5

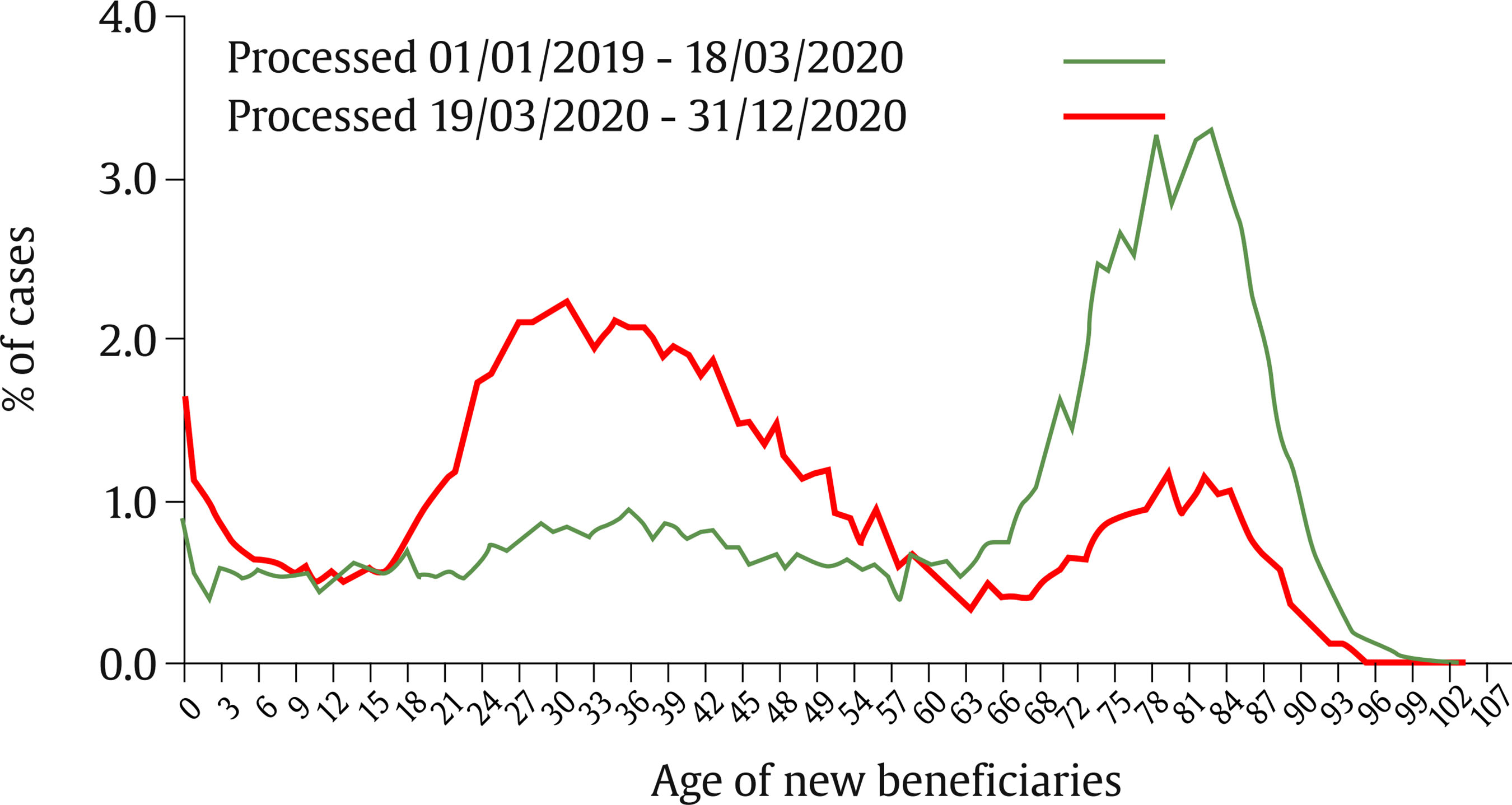

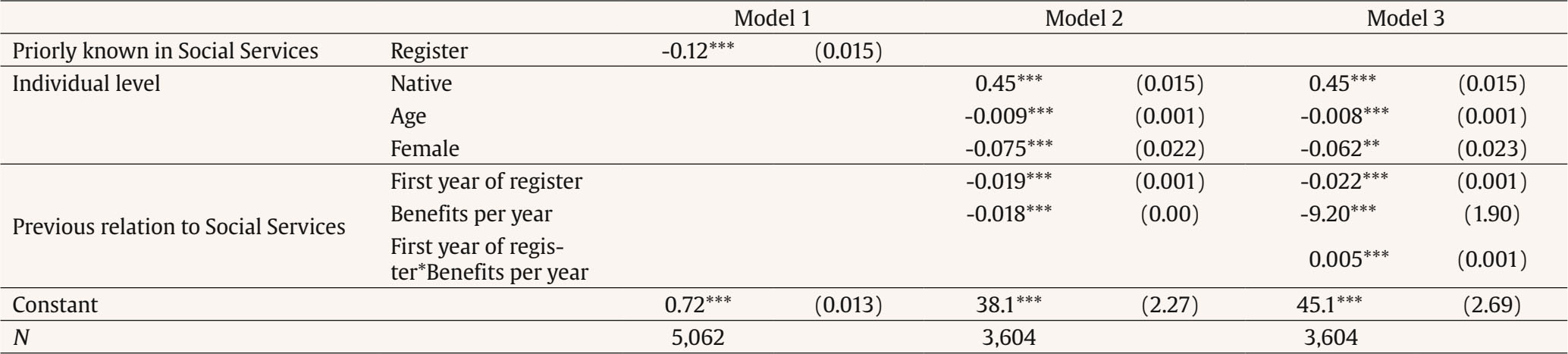

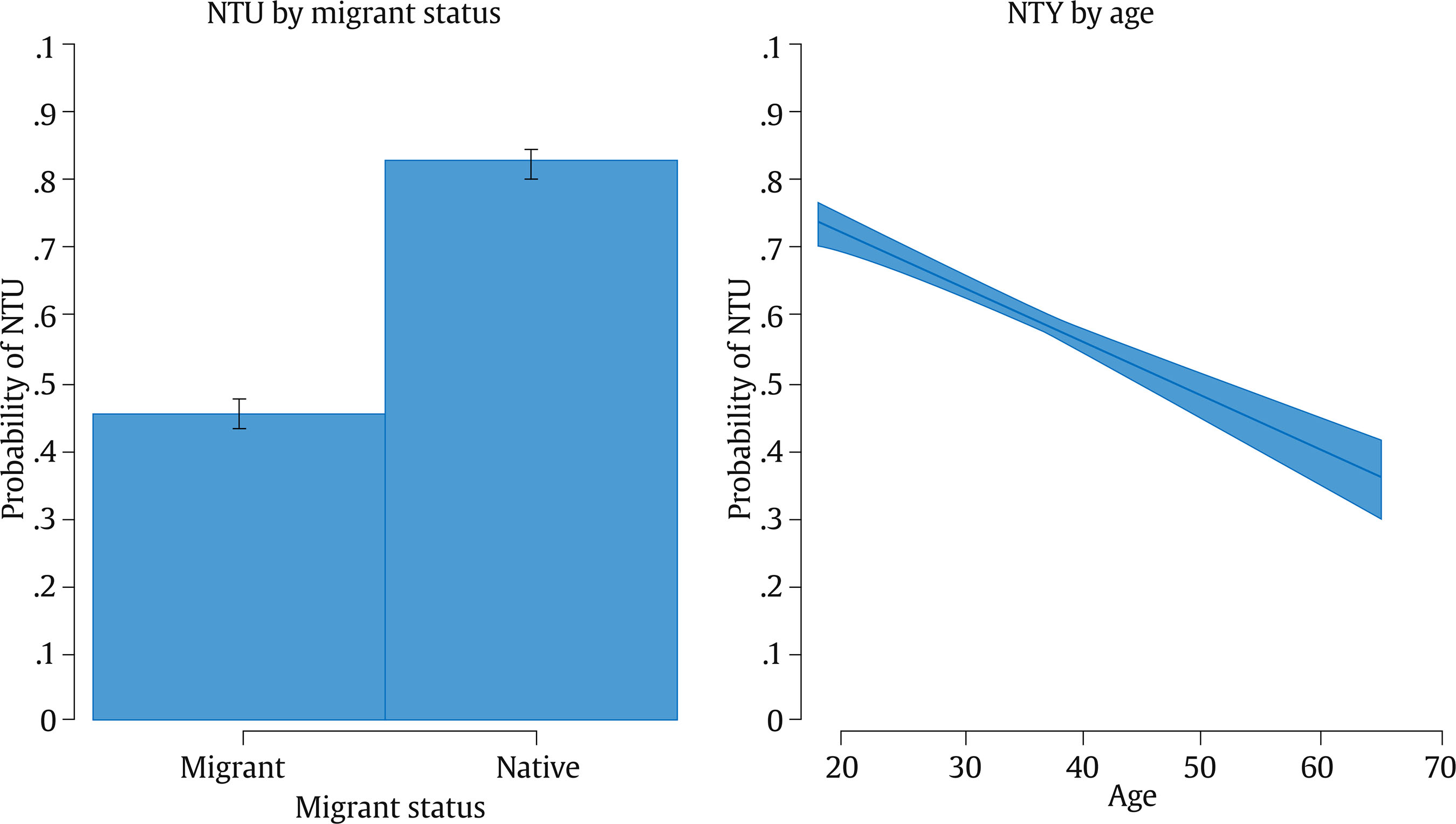

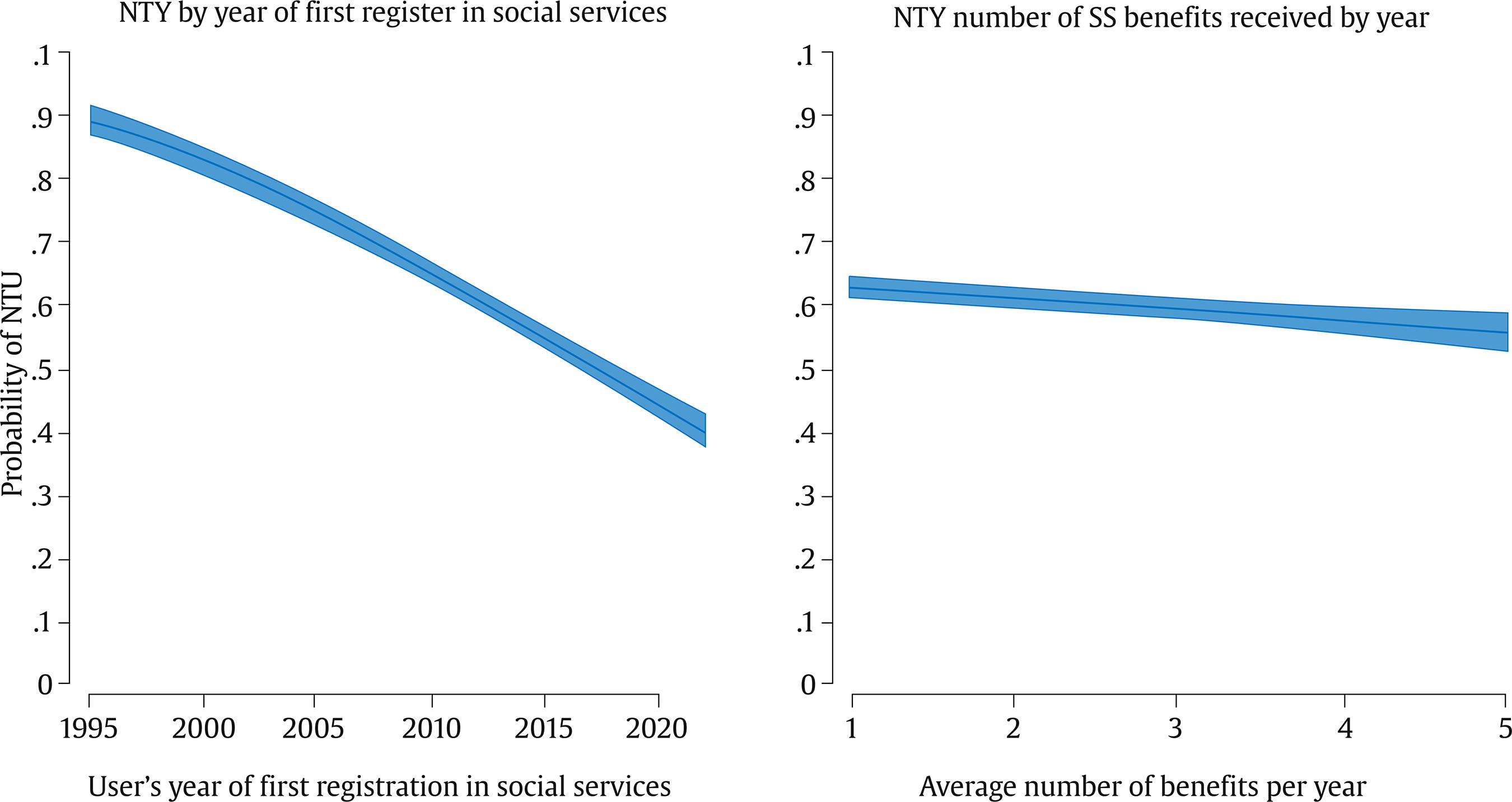

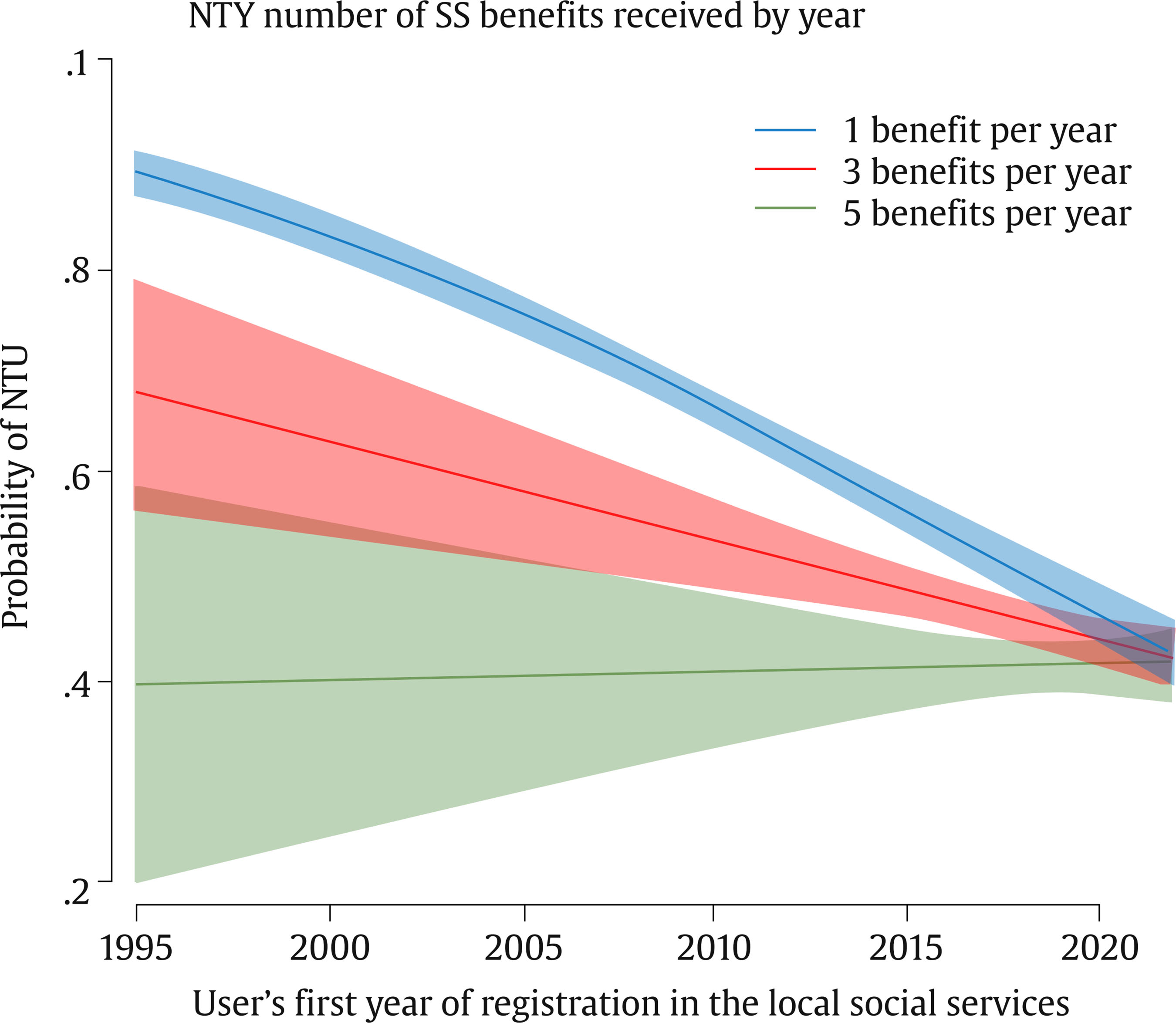

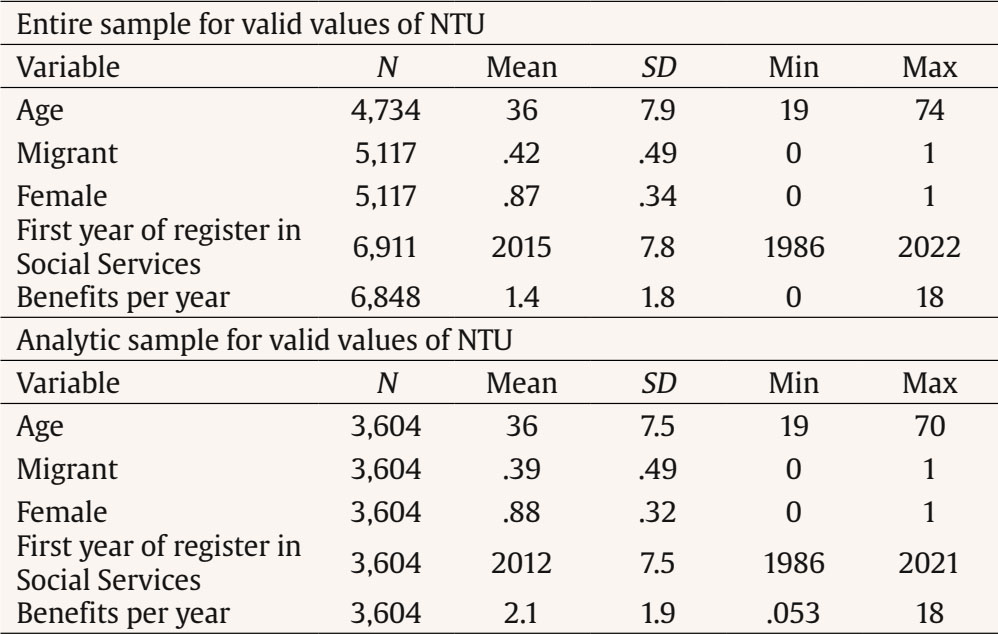

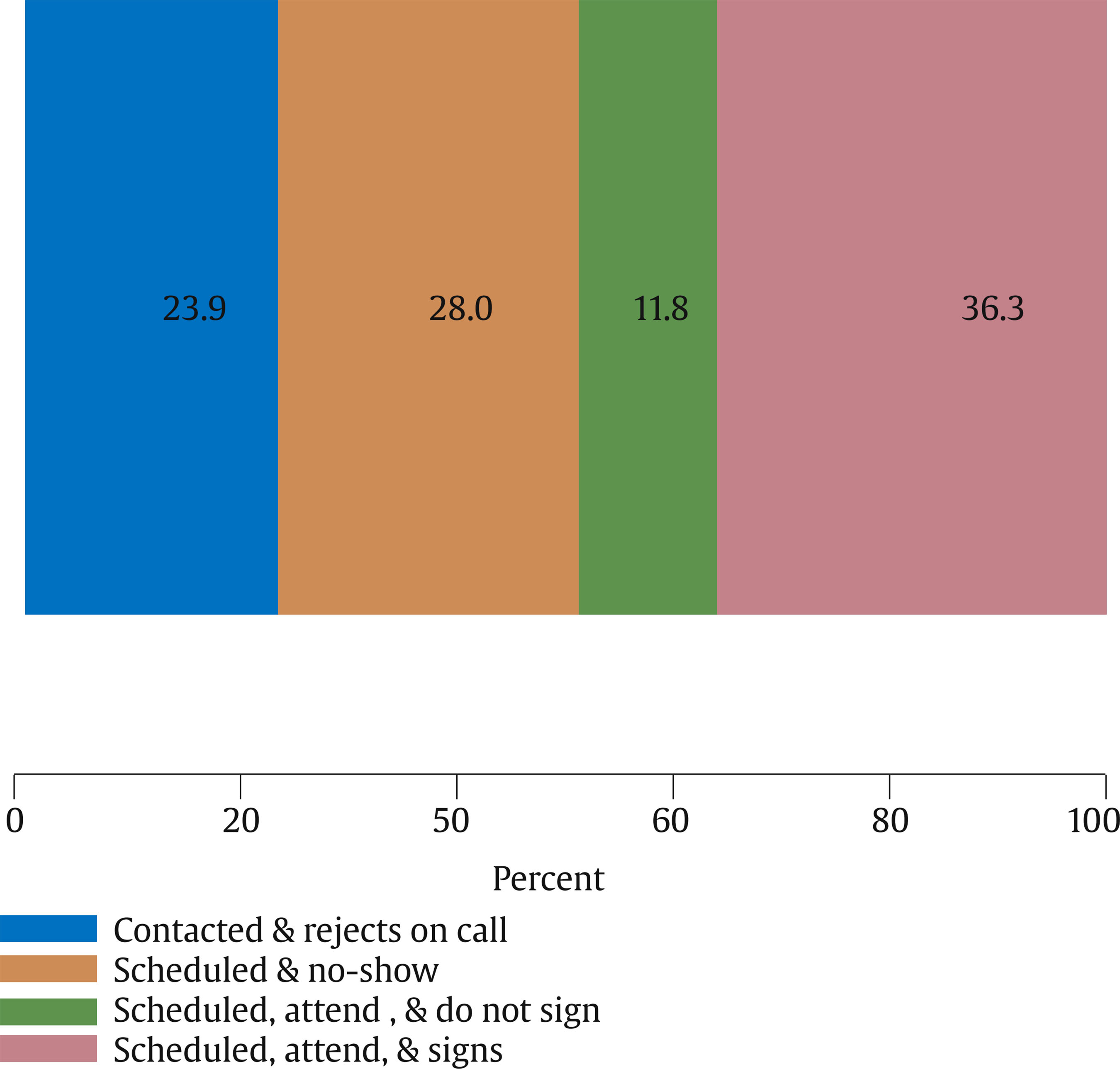

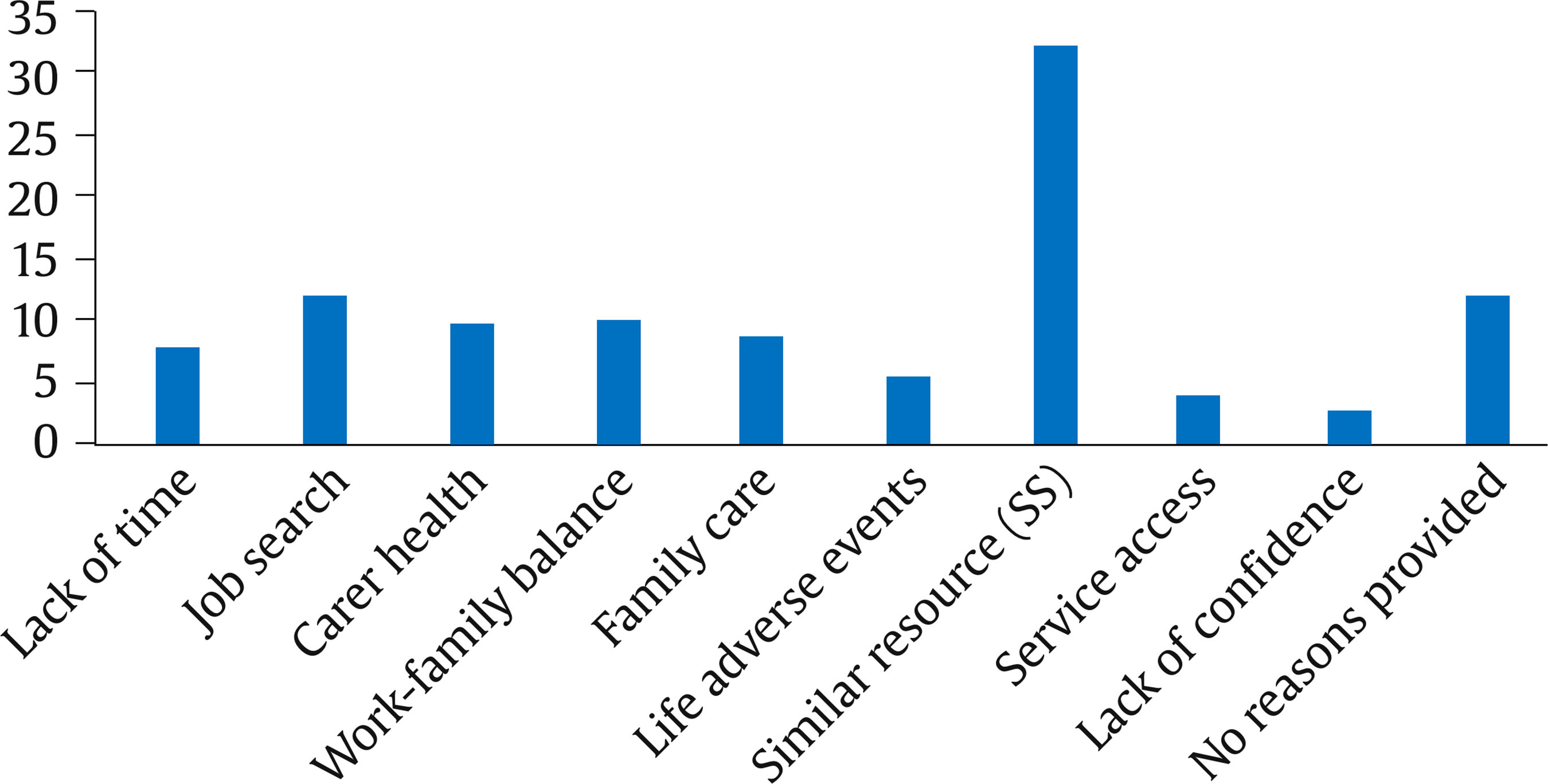

Correspondence: mjrodri@ull.es (M. J. Rodrigo).Raising young children is a challenging task, requiring parents to continually adapt their skills and strategies to match the rapid developmental changes occurring in the child’s abilities (Corkin et al., 2018). Furthermore, managing time and balancing work with family responsibilities can be taxing for parents of young children, particularly for vulnerable families with complex needs that require economic and social support. The extreme vulnerability of childhood, at a very important stage for its development in which adverse experiences must be avoided, requires a very considerable investment of time and effort, which are sometimes incompatible with the harsh living conditions of primary caregivers (Guralnick, 2013). Positive parenting programs are interventions seeking to support families facing concerns around time management (Repetti & Wang, 2014) highlighting the importance of meeting the needs of vulnerable families through early childhood support (Weiner et al., 2021). Positive parenting has had a prominent role in the policy research agenda of social scientists interested in vulnerable families with young children (Berger & Carlson, 2020; Crosnoe & Cavanagh, 2010). Through the evaluation of social interventions and the research that underpins them, we have come to understand the significant impact of promoting positive parenting on the healthy and cognitively stimulating development of vulnerable children, preserving their rights and strengthening parental capacities (Doyle et al., 2023; Rodrigo et al., 2015; Rodrigo et al., 2023; Vlahovicova et al., 2017). This requires a shared responsibility between parents and the State in creating the appropriate conditions for a positive exercise of the parental role (Council of Europe, 2006; Rodrigo, 2010). Despite the considerable efforts in providing parenting support to vulnerable families, there is a gap in understanding their interest in participating in the kind of interventions they are involved and, ultimately the profile of families refusing this type of support. A lack of knowledge about the systematic patterns that cause certain families to participate in parenting interventions more than others is a crucial limitation both for the academic research agenda and practitioners of positive parenting seeking to implement programs effectively. Systematic selection biases in accessing parenting programs may potentially confound with empirical evaluations of the intervention’s impact. Quantifying this bias and profiling families by their risk of refusing participation is precisely one of the contributions that our paper makes. Overlooking systematic participation patterns can obstruct the development of effective strategies to engage deserving families in social programs (Katz, 2007). Ignoring systematic patterns in participation hinders the identification of successful strategies to retain and engage vulnerable families in social programs (Shepardson & Polaha, 2023). Moreover, sustained high NTU rates can undermine the impact of early intervention programs, which play a vital role in disrupting the intergenerational transmission of social disadvantage (Cheng et al., 2016). One possible reason for the paucity of research on NTU to welfare benefits is that, although engagement with parenting programs has been identified as a crucial step, it is a multidimensional construct that is difficult to define and measure (Becker et al., 2015). The comprehensive CAPE model (Connect [recruitment/enrollment], Attend [retention], Participate [involvement], and Enact [implementation of learned strategies and techniques]) is very useful to frame this process (Piotrowska et al., 2017). Our study focuses on the Connect stage that refers to the recruiting process of potential applicants from the first invitation to participate in a social benefit to their written consent prior to its implementation. The social benefit offered here is the positive parenting program (Crecer Felices en Familia II [Growing up Happily in the Family -2 - GHAF-2]), delivered in a group-based and home-visit modalities. The program is a highly standardized evidence-based intervention to prevent child maltreatment targeted at parents of children up to eight years old in at-risk psychosocial contexts from any type of household unit. Its objective is to provide psychoeducational support leading to more effective child-rearing practices, reduced levels of parenting stress for individuals and households, and increased readiness for autonomy among adults. The evaluation of the first version of the program has shown its effectiveness when applied in social services, educational centers, and NGOs in Spain (Álvarez et al., 2020, 2021, 2006). Improvements have been obtained in parental attitudes towards parenting and education, better and more adjusted perception of parenting skills, reduction of parenting stress, and improvement of the family educational scenario. Quality of implementation factors such as greater program adherence, fewer crucial content adaptations, participant responsiveness, and better didactic functioning of the sessions predicted positive changes in parental child-rearing attitudes. Understanding Non-Take-Up: Who Rejects Social Policies and Why? There are three main reasons for the increasing attention given to NTU in social interventions and policy research. Firstly, its prevalence is significant. NTU rates in advanced democracies are notable, though challenging to compare due to diverse benefits, countries, and methods (Marc et al., 2022). Empirical research indicates that NTU rates vary from 50% (Bargain et al., 2007; Bruckmeier et al., 2021; Fuchs et al., 2020) to approximately 75% in specific contexts (Bouckaert & Schokkaert, 2011). Secondly, beyond prevalence, NTU is a detrimental factor for the success of social policies, undermining their effectiveness, efficiency, and equity (Dubois & Ludwinek, 2014; Hernanz et al., 2004). Finally, NTU can reflect systematic biases, potentially worsening the plight of excluded subgroups and impairing the accuracy of impact evaluations. Despite its significance in social policy research, NTU has received sporadic attention, particularly within the realm of family interventions and child welfare. Research on NTU was originated in the UK in the 1960s and disseminated to the US and certain European nations in the 1980s, though it has gained increasing focus in recent times (Goedemé & Janssens, 2020). Two clear reasons explain the slow irruption of this crucial stream of research. On the one hand, the belated acknowledgment of unintended consequences within benefit systems is the lack of suitable data. It is particularly difficult to pinpoint the exact portion of the population eligible for a benefit who either remain unaware or choose not to apply. This issue often arises from inadequate records that fail to precisely delineate the intended beneficiaries. Although administrative records can alleviate this problem to some extent, they may not be easily accessible for research purposes and often contain insufficient details for evaluating complex theoretical propositions and empirical testing. As a result, researchers sometimes conduct ad hoc surveys to assess the prevalence and reasons behind NTU. Many of these surveys, however, come with structural limitations, such as non-response from the most vulnerable-hard to reach populations, and response quality concerns (Bruckmeier et al., 2021; Marc et al., 2022). On the other hand, NTU was initially seen as counterintuitive, clashing with the dominant economic rationality suggesting eligible individuals should naturally claim available benefits (Blundell et al., 1988). This simplistic view, failed to account for the daunting complexity of regulatory frameworks and stringent administrative processes (Van Oorschot, 2002). It also underestimated cognitive challenges and the psychological barriers encountered by certain segments of the beneficiary population (Bhargava & Manoli, 2012, 2015). Recognizing these factors is crucial for addressing NTU and crafting policies that are accessible and engaging to all eligible individuals. Earlier causal accounts of NTU (see Hernanz et al., 2004) point at the importance of information costs, associated with application complexity, the psychological burdens of receiving benefits, stigma (Baumberg, 2016; Garthwaite, 2015), and cognitive barriers (Babcock et al., 2012). While behavioral economists attach less importance to information deficits (Bhargava & Manoli, 2012, 2015), financial literacy has emerged as a crucial barrier (Bertrand et al., 2006), alongside with institutional distrust and lack of support in benefit claims (Simonse et al., 2023). More updated understandings of NTU delineate three primary clusters of non-participation reasons: individual or “primary NTU”, administrative or “secondary NTU” factors and policy-related or “tertiary NTU” (Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022). The administrative factors refer to the degree and quality of information provision, user-friendliness of application procedures, and both internal and external organization of agencies responsible for policy delivery. The “policy factors” involve the degree and method of targeting public provisions, the nature of the benefits (type and structure), and the degree of discretion in policy implementation. While our research acknowledges the first two factors, it mostly concentrates on primary causes of NTU, which refer to individual decision-making processes, balancing costs and benefits associated with claiming, information and process costs, psychological and social costs, behavioral barriers, trigger events, and network effects. Notably, our methodology involved a personalized contact that, we claim, mitigated secondary and tertiary sources of NTU as the local staff contacted by phone all potentially deserving families and addressed them individually, explaining the intervention and requesting no further arrangement to participate that their informed consent. While the mainstream elaboration on the causes of NTU was essentially developed in the field of monetary or social security benefits, refusal to participate in positive parenting programs can also have its specific foundations. These programs, distinct in their approach to monetary benefits, demand considerable time and active engagement from both parents and children, whether in group settings or through more personalized methods such as home visits. The goals of such programs may seem unclear to some participants focused on facing more urgent needs, which can lead to reluctance or distrust. This could be particularly true for more socially isolated individuals lack of meaningful community connections (Metzel, 2005). This sentiment is tied to the so-called “dependency mentality” (Iacobuta & Mursa, 2018), a concept associated with numerous challenges including limited education and reliance on government aid that is frequently perpetuated by the media (Misra et al., 2003). Yet, while it is known that the duration of poverty significantly shrinks the likelihood of exiting poverty (Finnie & Sweetman, 2003), longer durations on welfare may simple reflect the persistent nature of poverty (Contini & Negri, 2006) and its negative effects on civic participation (Dahl et al., 2008). Context for the Present Study: Increasing Vulnerability of Families with Young Children The year 2021 produced an acute economic crisis due to pandemic-related lockdowns and economic slowdowns. Madrid, as many other big cities, experienced a significant shift in the sociodemographic profile of vulnerability. An analysis using local social services’ general register, illustrated in Figure 1, reveals an unprecedent growth of new users among the youngest children and adults aged 28-35. Vulnerability, according to all records, also intensified among migrant households. Figure 1 Age Distribution of Newcomers to the Social Services of Madrid before (green) and during the Pandemics (red).   Source: Own elaboration from the Registry of Social Services, Madrid City Council. This changing socioeconomic context prompted local authorities to revise and innovate their support strategies. A project was designed to assess the effectiveness of traditional poverty alleviation interventions focusing mostly on employability against those offering additional psychoeducational support to foster effective child-rearing practices, reduce parenting stress, and enhance adult autonomy. “Growing Happily in the Family-2” (GHF-2) was the brand-new social intervention that was set by the Madrid City Council in collaboration with the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security, and Migration and the Universities of La Laguna and Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. GHF-2 fosters positive parenting among vulnerable families with children under the age of eight years old receiving monetary support (Minimum Living Income [MLI]) from the National Institute of Social Security in Spain or the Madrid City Council (Family Card [FC]). A universe of 6,911 potentially eligible households was identified, which are the bases of our analyses. In January 2022, a multidisciplinary team of 48 practitioners comprising psychologists, educators, and social workers, under research contract for the entire project by the Madrid City Council sought to enroll at least 1,600 families upon acceptance to participate. The GHF-2 program was administered following a random assignment of participants in two groups (RCT trial registration: ISRCTN91206647, registered on 02/12/2022 before data collection of the intervention). The control condition involved an employability intervention delivered online (100 hours); the intervention group was divided into two subgroups: (a) people receiving employability intervention plus 40 hours of free childcare or for home chores support by external assistance and (b) people receiving employability intervention plus the opportunity to participate in the GHF-2 (45 hours) involving 20 group plus 7 home visiting sessions. The connection phase of this project presented a chance to analyze the traits distinguishing families who engage in interventions from those declining participation, following the process from the first invitation to the final parents’ written consent to enroll. We first explored the individual reasons (primary causes) of NTU reported by the interlocutors during the phone contacts. According to Piotrowska et al.’s (2017) CAPE model, connection failures may depend on a set of factors including family sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., parent’s age, socioeconomic status, economic stress, and family structure), child characteristics (e.g., age and gender), family processes (e.g., parental mental health, interparental conflict, and family/household chaos), contextual factors (e.g., migration status, and help-seeking beliefs), and organizational factors (e.g., access and availability factors). Therefore, any of these factors, as well as others, may appear in the reasons given by the interlocutors to justify their refusal to participate. Secondly, we investigated systematic differences between families who declined at initial contact and those who proceeded to engage with the program. Based on the official and project records of their individual sociodemographic characteristics and detailed household patterns of social service interaction, the study assessed the impact of prior engagement with social services, service tenure, assistance intensity, and ongoing social service relationships on the decision to participate or reject (Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022; Piotrowska et al., 2017). To sum up, this paper provides updated evidence on NTU in social interventions, enhancing the limited literature on family and parenting interventions—a relatively unexplored area in NTU research. This not only fills a crucial research void, but also carries significant policy and practical implications for family and parenting program implementation in contexts of vulnerability. Data Collection Procedures and Variables With the collaboration of the Spanish Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security, and Migrations (Registry of MLI beneficiaries), the Madrid City Council (Registry of Social Services; Registry of Family Card [FC] beneficiaries) and the project data on the contact phase a comprehensive database was compiled including all families eligible to participate in the program. Through this unique exchange of information, a pool of 6,911 potentially eligible families was identified. Inclusion criteria were: 1) perception of the MLI as residents in the Municipality of Madrid or the FC to any type of household unit; 2) having at least one child aged up to eight years old who they care for; 3) able to comprehend and understand Spanish to provide further consent to the study; 4) able to provide written informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: 1) participants who did not have a sufficiently good working knowledge of Spanish to provide written informed consent; 2) participants whose current mental symptoms or drug addiction seriously compromised their ability to concentrate on the assessments or intervention sessions; 3) participants whose infant have been removed from their care on a non-temporary basis by the child protection system. To minimize unwanted staff effects, a standardized protocol was applied to make contacts and obtain the informed consent (see Supplementary file) conveying the following information: (a) the aim of the action, (b) the formal involvement of national and local authorities supported by European funding, (c) the participation in the activities derived from the project, joining the treatment or the control groups randomly assigned after the consent, as well as the corresponding itinerary, (d) the confidentially of the personal data collected, and (e) the informed acceptance or rejection. Personalized telephone calls were done following a strict script to provide all basic information about the project. During the calls, families were formally offered participation in the project and were invited to attend a face-to-face interview to receive more detailed information about what is expected to do and potential benefits on each of the interventions, and to sign an affidavit of responsibility upon agreement. The multidisciplinary staff (21 professionals for the telephone calls, and 27 professionals for the posterior in-person meetings) recorded detailed information about the entire contact process, including whether and why the family refused to participate during the initial telephone call, their agreement to attend the interview, non-attendance, refusals to participate during the interview, and final agreement to participate, a long recruiting period that lasted five months. All participating families received a pack of school materials at the beginning of the project as a welcome gift. Upon acceptance, participants were also provided with a tablet with Internet access, free local transportation, and a school materials kit for their children. The study followed the Ethical protocol from the General Secretariat of Objectives and Policies of Inclusion and Social Welfare of the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security, and Migrations of Spain. The study has also been approved by the University Ethical Committee (University of La Laguna, Spain); registration number CEIBA2022-3194; date of approval: 18 November 2022. Written informant consents were obtained from all the participants complying with the two committee regulations. Plan of Analyses The comprehensive data set collected allowed us to better profile of households and individuals, as well as to reconstruct previous patterns of vulnerability and benefits accessed in the Social Services. Age is treated as a continuous variable, while migrant status and sex are represented as dummy variables (taking the value of 1 for migrants and females, respectively). The prior relationship with social services is modeled using three different approaches. Firstly, a continuous variable measures the first year in which the beneficiary was registered in the local social services. For any unregistered potential beneficiary, we attributed 2022 as the first year of contact. Thus, the first year of contact proxies the seniority of household members in social services, helping us to understand sustained assisted vulnerability over time. Secondly, the analyses also incorporate a ratio between time in social services and the number of benefits registered under their name. This variable provides a proxy for the intensity of the assistance provided over time. Finally, to calculate the ratio seniority by intensity of care, the most recent year of registration in social services was also registered, which helps to distinguish between long-term uncontacted vulnerable household members from those who, at the time of contact, were active in the local services. Table 1 displays the distribution of the intervening variables for both the analytic sample and the entire sample of valid cases. Three linear probability models tested the assumption that individual sociodemographic factors and the historical relationships with Social Services may contribute significantly to the likelihood that families accept or decline to participate in a social benefit including a positive parenting intervention. The chosen dependent variable in the analysis is a binary outcome scoring 1 if the family agrees to participate and 0 otherwise. Accordingly we employ linear probability models to allow for between model comparisons of estimates (Mood, 2010): Yij = αj + β1Xit + uit; where Yij is the outcome variable, Xij are the predictors for each family contacted, αi are individual specific intercepts for technicians j = 1,…, n and uit stands for the residual error. The three probability models were successively tested. Model 1 examines the effect of being engaged or not with social services prior to the formal invitation to participate in our program. Model 2 examines the influence of specific individual profiles with three variables: parents’ age, gender, and native/migrant condition; as well as the history of relation to social services with two variables: the effect of a longer or shorted history of social service interaction (first year of registration), and the intensity of support received from the system (mean count of benefits received for year). Finally, Model 3 tests the influence of variables included in the Model 2 plus the interactive effects of the duration of support by intensity of care on NTU. Description of Contact Process A pool of 6,911 potentially eligible families was identified. After administrative screenings of eligibility from the data base on MLI/FC beneficiaries, 5,574 were confirmed to be eligible to receive an invitation. Figure 2 categorizes the initial group of 5,574 families, which constituted the target population. This number excludes 538 families who were unreachable by phone due to incorrect contact information. Among the remaining families, 1,202 (23.9%) declined to participate during the initial phone call. Subsequently, the remaining families expressed their willingness to attend a personal appointment with the local staff to learn more about the project. However, out of these families, 1,412 failed to attend the scheduled appointments (28%), and an additional 593 attended the meetings but ultimately decided not to participate (11.8%). In the end, 1,829 families (36.3%), which accounts for more than one-third of the total population, signed agreements accepting their participation. Reasons for Rejecting on Call During the contact phase 1,202 families, 23.9% where asked the reasons for rejecting on phone contact and the following pattern of responses was obtained (Figure 3). The response categories showed a varied profile of reasons not only of problems in obtaining employment and that they were attending a ‘similar’ social service but also lack of time, lack of confidence, health problems of the holder, family care overload, work-family balance problems, various types of life events such as crowded housing, evictions, family conflicts, as well as foreseen logistical problems of traveling to the service centers at further stage of implementation. Modeling the Variables Predicting the Rejection/Acceptance Decision Linking the contact database of the project with the records on the history of participants with the Social Services, provided significant household and individual information for a portion of families who had previous interactions with local social services. Only 1,407 families had no prior registration. Therefore, this is the number of households for which no pre-contact phase information is available. This group constitutes 27.9% of the overall population. In multivariate analysis, any missing cases using household or individual information result from this unavoidable limitation. Notably, 20.9% of the unregistered (383 families) participated in personal interviews and signed participation agreements, allowing us to fill in some of this pertinent information for statistical analysis. The results of the three linear probability models are structured through a sequential analytical approach. To streamline the presentation, findings were shown on illustrative diagrams, while overall comprehensive model outputs, inclusive of coefficients and standard deviations, are delineated in Table 2. Table 2 Ordinary Least Square regressions (OLS) on the Rejection/Acceptance Decision   *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 As we know from the descriptive section, the propensity to decline participation in positive parenting programs is generally high (acceptance rate is 36.3%), but according to Model 1 NTU significantly increases for individuals who have not engaged with social services previously. Those participants with past social services interactions face about a 60% chance of not taking up the offer. In contrast, for newly identified, unregistered individuals, the non-take-up rate jumps by more than 10 percentage points, with an alarming 72.7% choosing not to participate. Results from Model 2 show that women and migrant families, who often lack extensive support networks in their new localities, do show a higher propensity to engage in the intervention. Figure 4 indicates that migrant status is the strongest predictor of participation: natives demonstrate a significantly higher likelihood of refusal at 82.7%, whereas migrant acceptance rates are considerably higher at 45.3%. Figure 4 Proportions of NTU by Migrant Status and by Age.   Note. Estimates obtained from Model 2 in Table 2. Conversely, data reveals an inverse relationship between age and willingness to participate, with younger households displaying greater reticence. The rejection rate peaks at approximately 70% for households where the beneficiary of reference is aged 20 and shrinks to 55% by age 40. Results from Model 2 also show that a longer history with social services is notably linked to a decreased likelihood of accepting an offer to join the parenting program. Figure 5 (panel on the left) elucidates that earlier registration with local social services leads to a substantial dip in participation rates. Users who had their initial interaction with municipal services shortly before the outreach were more inclined to accept the program, with a participation rate hovering around 90%. However, this openness markedly diminishes with the length of service tenure: individuals whose first contact with the services dates back approximately a decade exhibit refusal rates exceeding 60%. In addition, the intensity of care received from social services deters further engagement in new interventions (Figure 5, panel on the right). The modeled effect of care intensity on the likelihood of participating in our study is virtually flat, indicating a negligible association between the number of yearly benefits received and the risk of NTU. Figure 5 Proportions of NTU by Year of the First Register and Number of SS Benefits by Year.   Note. Estimates obtained from Model 2 in Table 2. According to Model 3, the interaction between the duration of social service engagement and the intensity of care yielded significant insights, despite the previous significant effects. Data reveal that sustained vulnerability does always not correlate with a higher likelihood of NTU. Only long-term beneficiaries with minimal interventions exhibit a significantly pronounced decline in participation. However, as depicted in Figure 6, families that have longer engaged with social services and more intensively—receiving three to five interventions annually—show a much flatter slope, indicating steadier engagement rates. This suggests that families facing prolonged hardship may indeed be very receptive to new interventions aimed at supporting their parenting needs, challenging the assumption that greater vulnerability leads per se to service saturation and NTU. The group characterized by prolonged, but less intense, interaction with social services, shows an NTU rate of around 40%. This implies that despite enduring vulnerability, only one in six of these families remains receptive to supportive interventions. Figure 6 Proportions of NTU in the Interaction of First Year of Registration (Seniority) by Number of Benefits per Year.   Note. Estimates obtained from Model 3 in Table 2. Robustness of the Results The modelling strategy used for the estimation of the results prioritizes simplicity and parsimony. However, the robustness of our results was through a variety of alternative estimation methods. These include logistic regression models, Heckman selection models that account for biases due to non-participation in social services, and hierarchical models that correct for different skills among staff who contacted families, with a small intra-class correlation (ρ = .09) indicating minimal variation due to staff differences. Furthermore, the introduction of alternative control variables did not substantially alter the outcomes including last year of register in the social services, type of benefits obtained, and household type. Across all these checks, the findings remained stable, reinforcing the validity of the conclusions drawn from the primary analysis. Moreover, our findings stand if using multinomial modeling approaches that categorize responses as either immediate refusal at the first call, refusal post-agreement to schedule an informative meeting, or consent to participate as evidenced by a signed agreement. Research on NTU in family support programs is an underdeveloped field of scientific and practical inquiry. And yet when people do not receive benefits to which they are entitled, the risk of poverty and exclusion increases, especially when the benefits are intended for the poorest families and children. In Spain, efforts to quantify non-take-up in social programs by actors, other than producers of official statistics or economic researchers, represent a very small minority mainly linked to social researchers and applied to municipal settings (Lain & Juliá, 2022). In turn, the international implementation research on social interventions such as evidence-based parenting programs has produced a variety of models (Berkel et al., 2011; Fixsen et al., 2009) and reporting standards (Hickey et al., 2021), but none of them stress the relevance of analyzing the contact phase prior to acceptance. This study tries to fill this gap by addressing the traceability of the NTU phenomenon during the contact phase, before implementation of the broad RCT parenting intervention including the “Growing Happily in the Family-2” program. Using sources of household and individual data from the interviews in the contact process combined with the records of the Registry of Social Services of the Madrid City Council (5,574 cases in total), we have obtained an acceptance rate of 36.3% (1,829 people) to participate. Notice that the rejection rate of 63.7% corresponds to a genuinely informed decision since the potential applicants are aware of all three conditions (one control and two interventions), although there is still uncertainty concerning which one they will be randomly assigned to. NTU of Minimum Living Income benefits is a widespread phenomenon in a variety of European countries, with rates around 50 to 60% in Spain, Germany and Belgium, over 30 to 40% in Finland and France, and a recent drastic reduction of rates from 44% to 10% in UK, despite the differences between the social welfare and security systems among countries (Marc et al., 2022). Based on the parents’ reasons for NTU emerge a complex profile of individual and family processes involving socioeconomic vulnerability, employment search, time constraints, physical and mental health problems, family caregiving overload, and conflictive relationships, combined with chronical stress motivated by cultural factors since the majority are migrant, crowded housing and evictions, in addition of attendance to social services. Jobless parents with high economic hardship had also a profile of poorer physical and mental health, heavy demanding childbearing, family-job conciliation and housing problems aggravated by adverse life events (Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022), all of them stand for primary individual and family reasons of NTU in our sample. The pattern is in line with the multidimensional nature of the NTU in the connection phase according to the CAPE model (Piotrowska et al., 2017). The vulnerability of socioeconomic poverty and asset deprivation also carries a burden of chronic stress and emotional blockage that has negative effects on physical and mental health, as well as on the quality of parenting (Jones et al., 2018). Paradoxically, high-needed families because of their demanding and traumatic life circumstances are in a worse position to benefit from parenting support unless preventive and accompanying measures are taken to alleviate their situation. Our findings also reveal the characteristics of participants accepting the social intervention compared to those who refuse to participate. The profile with the higher NTU rates is made of natives (82.7%) and younger potential recipients in the range of 20 to 40 years old (70 to 55%). The high NTU rates cannot be attributed to a poor communication strategy from the institutions since we have combined phone calls and in-person meetings that has been previously related to NTU reductions (Lain & Juliá, 2022). The extreme bias of acceptance rates towards migrant applicants (corresponding to 16% of the total population in the city of Madrid) is counterintuitive for those who claim that having less experience in dealing with the welfare system and, consequently, less information is related to higher NTU rates (Janssens & Van Mechelen, 2022). This trend could be more the result of a meaningful decision-making context which implies expectancies (probably held by women which are also majoritarian in our sample) of a better life for the family in the host country (Cebolla-Boado et al., 2021). Higher rates of mothers are in line with the underrepresentation of fathers in intervention studies despite his positive influence on the couple and children wellbeing (Castellano-Díaz et al., 2024; Osborne et al., 2022; Pfitzner et al., 2015). In turn, given that all families have younger children and social vulnerability, the increasing tendency to lower NTU in middle and older adulthood may be attributed more to the greater awareness of the need for parenting support, compared to younger participants, rather than to vulnerability per se. Another remarkable finding is related to the effects of seniority in the social services on NTU. Rate of acceptance is approximately 90% for uses who had their first contact with the municipality shortly before being contacted, whereas if the first contact happened around 10 years earlier, the rate of refusal was above 60%. This trend underscores a counterintuitive dynamic where prolonged engagement with social services may not foster closer cooperation with additional support programs, but rather, it seems to be correlated with a growing reluctance to participate. This finding aligns with what is commonly referred to as ‘intervention fatigue’ (Heckman et al., 2015). Individuals with extensive histories of social service interaction may experience a form of intervention fatigue, whereby repeated exposure to various programs and initiatives leads to a certain weariness or skepticism regarding new interventions. This could explain the higher refusal rates observed among long-term service users, indicating that the cumulative effect of sustained engagement does not necessarily equate to increased participation but may, in fact, engender a reticence towards additional programs. Such insights highlight the need for a nuanced understanding of how long-term service users perceive and respond to new support opportunities. However, intensity of support provided during these years, although slightly negative and marginally significant, fosters a positive inclination towards utilizing additional services, thereby counteracting somehow any potential ‘intervention fatigue’ factor. The significant interactive finding of seniority by intensity of care obtained in Model 3 helps to disentangle the previous dissonance. This finding reveals that seniority in the social services is not a significant predictor of NTU for the most vulnerable users who consistently receive more intensive levels of support. Intervention fatigue is predominantly observed among those with an extensive yet superficial engagement with social services, such as simple receiving material benefits without engaging in real supportive relationships with the practitioners. In our case, the basic social services, staffed exclusively by social workers, tend to provide individual assistance mainly consisting of material aid to vulnerable families. Likewise, upon statistical testing alternative control variables in our models including last year of register in the social services, type of different material benefits obtained, and household type did not substantially alter the results. Therefore, this relevant finding adds an important reason to recommend the use of parenting programs delivered by multidisciplinary professionals. especially able to develop collaborative alliances and to strengths the capacities of children and parents who use the services (McGregor et al., 2020). A large body of research on formal social support has highlighted its benefits in the context of parenting, especially in circumstances of high adversity (Kang, 2012; Turner & Brown, 2010). However, it has also been documented that the exclusive reliance on the provision of formal support (multi-assisted families) may undermine parental feelings of adequacy and confidence in their role (Doherty & Beaton, 2000). It has also been shown that parents who declare higher levels of satisfaction with parenting programs are those who excessively rely on professionals’ work and do not complement their parenting task with informal sources of support (Rodrigo & Byrne, 2011). Therefore, it is recommended that in addition of providing formal support, professionals should also help families to expand their natural support networks. The insights provided by this research are also crucial for policy makers and practitioners who aim to design and implement more effective social interventions. To mitigate NTU rates, policies must consider targeted outreach to previously unregistered families and tailor intervention approaches to the unique needs of younger parents. Additionally, the finding that longer service tenure may increase NTU suggests a need for varied engagement strategies for different family histories within social services. Ultimately, this paper informs a nuanced understanding of NTU determinants and challenges prevailing assumptions about service utilization. It calls for a strategic re-evaluation of how social interventions are presented and communicated to potential beneficiaries, ensuring that the families who could benefit the most are not those left behind. Our study has several limitations worth noting. As a main limitation, this study analyses the NTU phenomenon under specific conditions that could compromise the generalization of its findings. The broad RCT community trial involving employment training and family support for parents with young children has been unconditionally offered to recipients of social benefits. Secondly, prior contact with social services may skew the results. Although our robustness checks with Heckman re-estimation models support our conclusions, we only controlled for, rather than directly modeled, potential selection biases. Lastly, it would also be important to address the generalizability of the findings beyond the studied context. This is a well-funded, large-scale, experimental project with time-intensive interventions, located in a major urban area, whose participant pool was primarily drawn from official registries of applicants for MLI benefits. Our findings should be contrasted with other smaller community and less-resourced settings where potential participants have prior relationships with professionals in the Social Services who are the program implementers, likely resulting in a different NTU pattern. This study has helped us reflect on the advantages of studying the NTU of beneficiaries of the social welfare system in the realm of family research. Our findings of the NTU phenomenon respond to the relevant question “to what extent the intended population has been reached” that lies at the interception of evidence, policy, and practice. Our empirical answer is that, once defined the pool of potential applicants, there is a need to improve accessibility to information and to reinforce support and accompaniment to the parents (father and mother) in the recruitment process, overcoming the first organizational barrier to reaching the target population. In our case, from the internal barrier of self-selection bias underlying the NTU’s final decision to reject/accept, a peculiar target group has emerged. They are overloaded women, mother of young children and migrant, a group that is likely to be left out of consideration in labor policies and practices, despite its claim for equal gender and culturally inclusive opportunities. More efforts should be made to adapt family support and labor policies and practices to meet the needs of these families and reduce NTU rates. From the scientific point of view, quality standards for community-based evidence should emphasize the need for NTU studies to gain more visibility, especially when referring to applicants of both financial and family support benefits (Acquah & Thévenon, 2020; Gottfredson et al., 2015). Parents and children are subjects of rights therefore they are entitled to receive parenting and family support in the best conditions whatever could be their situation (Dolan et al., 2020). Including the reasons for NTU responses is also very useful to better understand the complex needs of this segment of the population, aggravated by severe life adversities and excessive family burden, whose social transfer lies at the interface between employment assistance and welfare policies. This evidence opens the way to identify successful strategies to engage and retain vulnerable families in parenting support programs. The policy design should essentially determine the benefit levels and eligibility criteria that can affect take-up rates both directly and indirectly. The most needed families who are unwilling to access family support intervention also underscores the importance of preventive measures to alleviate the daily burden on these families. In this line, European family support policies emphasize that professional work should provide parenting support for a great variety of families aimed at prevention and promotion of capacities and resilience even in the most vulnerable cases, as well as a coordinated approach from multiple sectors to address the full range of families’ needs (Canavan et al., 2016; Frost et al., 2020; Rodrigo et al., 2015). In sum, community researchers and the evidence they provide on NTU can help inspire changes that policy makers and practitioners need to undertake to avoid passive chronicity as welfare recipients, designing better timing and typology of support provision, and ways to facilitate the uptake of family support benefits in both fathers and mothers to improve child and family well-being. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgments We would like to express our gratitude to the General Sub-Directorate of Social Innovation of the General Directorate of Social Services and Attention to Disability of the Government Area of Social Policies, Family and Equality of the Madrid City Council, to all the technical and administrative staff for their great dedication and involvement in the project, as well as the families for their participation. Cite this article as: Cebolla, H., Martín, J. C., & Rodrigo, M. J. (2025). Optimizing engagement: Factors influencing family participation in a positive parenting program among vulnerable households with young children. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(1), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a5 This study was supported by The European Commission for the National Plan for Recovery, Transformation and Resilience of Spain, which was transferred to the Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migrations of Spain to perform an RCT early intervention study that was carried out by the Madrid City Council under a research contract with the University of La Laguna and the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canarias, Spain. Supplementary Data Supplementary data are available at https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a5 The datasets generated and/or analyzed in the contact phase are publicly available. The anonymized microdata files on the Open Data Portal files is uploaded to the Open Science Framework https://osf.io/preprints/osf/sxgqt?view_only= and Google drive https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/1hcOP98557TInHKP22VS1BD9EM7uKA6qy including the same data base (.xlsx), the data in format stata (.dta) and the statistical programming used (.do). In the case of publication or dissemination, please make special reference to the authors of the study and the funding agencies. |

Cite this article as: Cebolla, H., Martín, J. C., & Rodrigo, M. J. (2025). Optimizing Engagement: Factors Influencing Family Participation in a Positive Parenting Program among Vulnerable Households with Young Children. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(1), 53 - 62. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a5

Correspondence: mjrodri@ull.es (M. J. Rodrigo).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB Supplementary files

Supplementary files CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS