The Social Perception of Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence and Problematic Internet Use among Spanish Adolescents: A Serial Mediation Model Involving Teacher-Student Relationships and Stress

Jorge Gómez-Hombrados & Natalio Extremera

Universidad de Málaga, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a4

Received 15 July 2025, Accepted 12 November 2025

Abstract

Objective: Problematic internet use (PIU) has become a significant concern among adolescents. Considering the classroom as a key social environment during adolescence, the way students perceive their teachers’ emotionally intelligent behaviors may be particularly relevant for their academic and personal adjustment. While previous studies had examined individual predictors of PIU, the role of teachers' emotionally intelligent behaviors (TEIB) in mitigating PIU remained unexplored. This research aimed to examine the underlying mechanisms in the link between TEIB and PIU through a serial mediation model involving teacher-student relationships (TSR) and stress in two independent studies. Method: Two studies with Spanish adolescents were conducted: a cross-sectional study (N = 1,966) and a 9-month prospective study (N = 517). TEIB, TSR, stress symptoms (Study 1), perceived stress (Study 2), and PIU were assessed. Results: In both studies, TEIB were positively associated with TSR and negatively associated with stress and PIU. The serial mediation path was significant: TEIB predicted higher TSR scores, which in turn was linked to lower stress levels, thereby reducing PIU. In Study 1 both simple and serial mediation effects were significant, whereas in Study 2 only the serial mediation effect was supported. Conclusions: These findings highlight the importance of TEIB in reducing students’ PIU. Schools should consider implementing emotional skills training programs for teachers to foster supportive TSR and promote healthier online behaviors among adolescents. Finally, school-based recommendations for teachers to prevent adolescents from PIU are suggested in the light of our findings.

Keywords

Teacher emotionally intelligent behaviors, Teacher-student relationships, Stress, Problematic internet use, AdolescenceCite this article as: Gómez-Hombrados, J. & Extremera, N. (2026). The Social Perception of Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence and Problematic Internet Use among Spanish Adolescents: A Serial Mediation Model Involving Teacher-Student Relationships and Stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260812. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a4

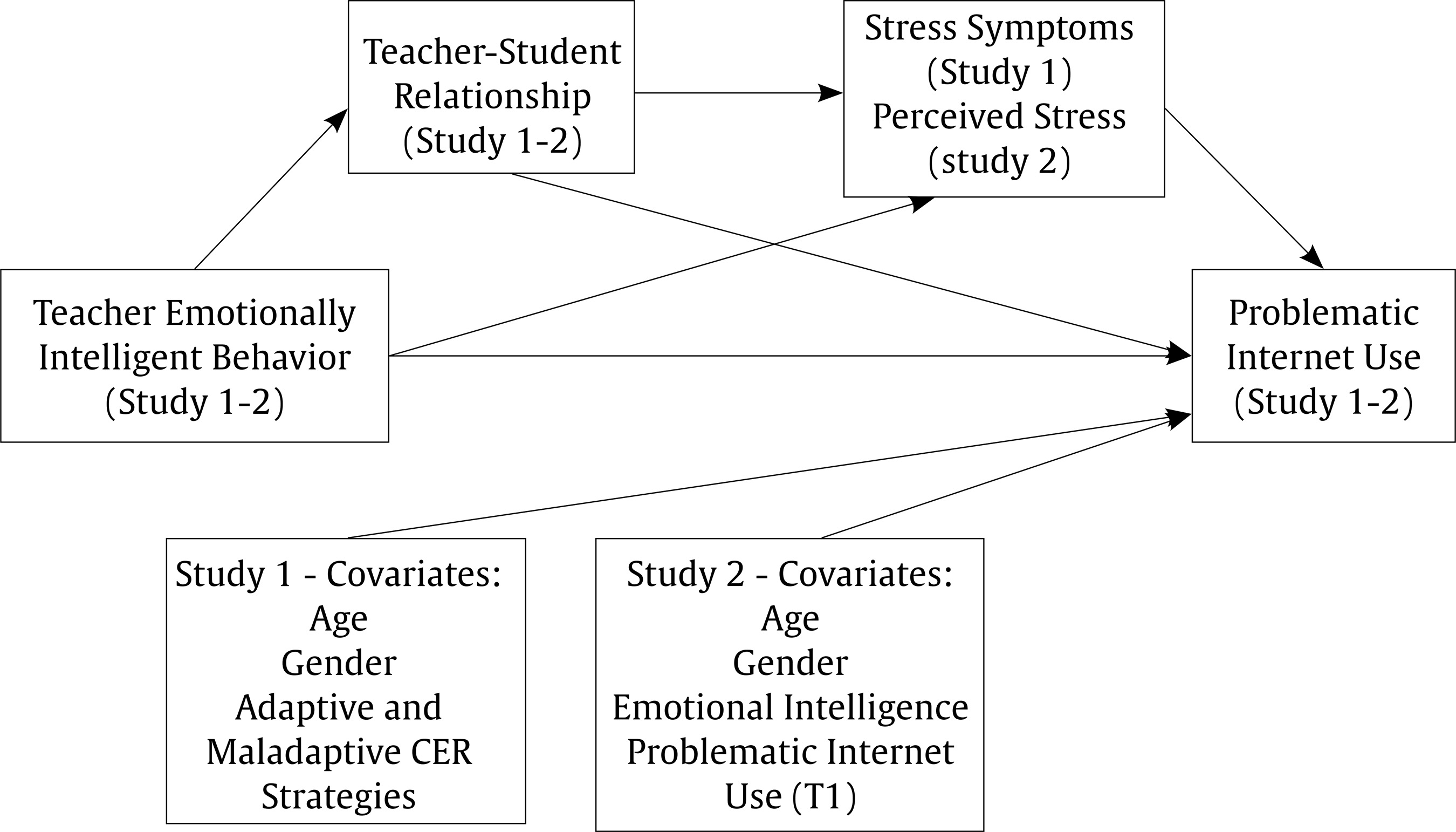

Correspondence: jorgegh@uma.es (J. Gómez-Hombrados)Over the last decade, problematic internet use (PIU) has become a major concern during adolescence and early stages of adulthood (Mishra et al., 2024). Specifically, the prevalence in Spain of this problematic use is around 33% of the adolescent population (Nogueira-López et al., 2023). Adolescence is a developmental stage considered to be at risk (Bickham, 2021) due to the neurobiological and psychosocial changes that occur during this period (Cerniglia et al., 2017). Adolescents are not only more vulnerable to problematic ICT use (Lozano-Blasco et al., 2022) but this use also leads to negative short- and long-term psychological consequences in well-being and mental health (Mishra et al., 2024). Numerous studies have confirmed a robust link between PIU and increased mental health issues (Soriano-Molina et al., 2025), depression (Ye et al., 2023), anxiety (Fumero et al., 2018), suicidal behavior (J. Wang et al., 2022), or sleeping problems (Alimoradi et al., 2019). Considering the potential deleterious effects of PIU on mental health in adolescents, knowing the underlying mechanisms is a significant challenge in research to design future school intervention programs. Given these well-documented risks, it becomes essential to examine the mechanisms that explain why adolescents develop problematic patterns of internet use. In this regard, several models have been proposed to explain the mechanisms underlying problematic technology use. The I-PACE model is a theoretical framework designed to explain the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders and other technology-related addictions (Brand et al., 2019; Brand et al., 2016). This conceptual approach explains PIU as the result of the interaction between predisposing personal characteristics (P component), affective and cognitive responses (A and C components), and executive functioning deficits (E component). Similarly, the Compensatory Internet Use Model is a complementary framework (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) which proposes that PIU is motivated by the need to compensate for emotional, social, or psychological deficiencies like stress, anxiety, or loneliness. However, beyond individual internal characteristics, prior meta-analyses have found that contextual and social factors (e.g., family conditions and parent-child relationships) are associated with mental health problems related to PIU (Fumero et al., 2018). These findings suggest that adolescents’ digital behaviors are shaped not only by individual dispositions but also by their immediate social environments. Adolescents spend a considerable amount of time in classrooms, making them crucial environmental settings that can significantly shape their behavior (Thapa et al., 2013). According to the stage-environment fit theory, a negative school environment may contribute to problem behaviors both within and beyond school boundaries (Eccles et al., 1993). Relatedly, recent studies have highlighted schools’ critical role in adolescent PIU, which is generally thought to occur more frequently outside school (Li, Li, et al., 2013; Li, Zhou, et al., 2016). In this regard, teachers represent one of the key components of the school context (Chemnad et al., 2023). However, contextual factors associated with teachers’ conditions and their relationship with PIU have been neglected (Fumero et al., 2018). Our studies focused on the interpersonal perspective, emphasizing the social perception of individual behaviors perceived by others (Kenny, 2020), that is, how teachers’ behavioral characteristic of emotional intelligence (EI) as perceived by students at school is related to adolescents’ academic and personal outcomes (Extremera et al., 2025; Floman et al., 2023). In this sense, focusing on teachers’ emotional characteristics provides a deeper understanding of how features of the school environment influence students’ adjustment. Teacher Emotionally Intelligent Behaviors and PIU Teacher emotional intelligent behaviors (TEIB) are defined as those behaviors that involve emotional abilities in school contexts, following Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) EI model, which includes emotional skills such as perceiving emotions, using the emotions to enhance others’ thoughts or facilitate problem-solving, understanding causes and consequences of emotions, and regulating oneself´s and others’ emotions (Ivcevic et al., 2021). Traditionally, emotional skills have been assessed with ability and self-report measures (Elfenbein et al., 2015), and both describe actual behavior. Although emotionally intelligent behavior has been theoretically defined as distinct from the EI ability and self-efficacy, research specifically focusing on such behavior as observed by others who closely interact with targets has remained scarce. In the present research, we examined TEIB, measuring it with observer reports. This novel construct was based on supervisors’ emotionally intelligent behavior, which is considered a job resource, and focuses on how employees perceive the emotional competencies of their supervisors and how this impacts the motivational resources of the employees (Ivcevic et al., 2021). In this sense, similar competencies may be needed in school contexts and how students perceive their teachers’ emotional abilities may impact their behavior. In fact, Jennings and Greenberg’s (2009) Prosocial Classroom Model suggests how teachers influence their students not only by teaching but also by promoting prosocial behaviors. This model proposes that emotionally competent teachers better recognize how their emotions impact interactions and understand others’ emotions. Also, they are more able to build strong relationships, manage conflict skillfully, make responsible decisions considering their impact on others, manage emotions and behaviors effectively, and encourage student autonomy. Thus, this repertory of emotionally intelligent behaviors of teachers creates safe, satisfying, and caring school environments that foster the development of adolescent students (Jennings et al., 2021). Previous studies had found that teachers’ EI enhances student academic achievement (Alam & Ahmad, 2018; Singh & Ryhal, 2023), improves student social and emotional competencies (Brackett & Katulak, 2007; Poulou, 2017c; Skura & widerska, 2022), enhances self-esteem (Curci et al., 2014), and mitigates the mental health consequences of cyberbullying (Mérida-López et al., 2025). Considering that PIU is also related to deficits of both emotional (Chen et al., 2021) and social difficulties, like in teacher-student relationships (Fumero et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2018), TEIB might be a significantly protective factor associated with PIU between adolescents. To our knowledge, no studies have yet examined students’ perceptions of their teachers’ EI abilities in relation to PIU. However, based on the Prosocial Classroom Model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), this link between teachers’ emotional competencies and students’ social and emotional competencies might not be directly related, and some underlying mechanisms are potential mediators of this link. Despite growing evidence on the importance of contextual influences on adolescent PIU, as far as we know no prior research has examined how students’ perceptions of their teachers’ emotionally intelligent behaviors may serve as protective factors in PIU. The Mediating Role of the Teacher-Student Relationship During adolescence, social support plays a central role in emotional and behavioral adjustment (Pina et al., 2025). Supportive relationships with parents, peers, and teachers provide adolescents with emotional security, validation, and coping resources that promote psychological well-being (Bi et al., 2021; Herrero Romero et al., 2025). Empirical evidence shows that adolescents with stronger social support networks are less likely to engage in maladaptive behaviors, including problematic or compensatory internet use (Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021; Zhang et al., 2025). Moreover, a lack of perceived support from key figures such as parents or teachers has been linked to higher stress and greater risk of excessive technology use (Rueger & Malecki, 2016; Uçur & Dönmez, 2021). Within this broader network, teachers represent a salient and stable source of social support in daily school life, complementing family and peer influences and fostering adolescents’ social and emotional development (Bi et al., 2021; Jiménez-Iglesias et al., 2017). Some research has underscored the crucial role of supportive teacher-student relationships (TSR) both in the development of adolescents in school contexts and in the creation of healthy school climates (Kincade et al., 2020; Varga, 2017). The quality of TSR is closely linked to PIU in adolescents, with research consistently showing that positive TSR serve as a protective factor against excessive internet use (Jia et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2020). Adolescents who perceive warmth, trust, and support from their teachers tend to exhibit lower levels of PIU, as strong relationships at school reduce the likelihood of turning to the Internet for emotional compensation (Jia et al., 2024). Conversely, poor TSR are associated with higher PIU, as students may seek online environments to fulfill unmet social and emotional needs (Jia et al., 2018; Shi et al., 2023). Studies have also indicated that TSR not merely correlate with PIU but actively moderate its effects, meaning that even students with a tendency toward excessive internet use may show lower levels of PIU when they have supportive teacher interactions (Dong et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2020). This highlights the importance of fostering positive teacher-student interactions as a key strategy for reducing PIU among adolescents. It is also important to consider the cultural context of TSR when interpreting previous findings. Western and particularly Southern European contexts TSR tend to be characterized by greater socioemotional closeness and egalitarian interaction patterns (Artola Bonanno et al., 2024; Bi et al., 2021). In Spain, for instance, adolescents perceive teachers as a significant but emotionally approachable source of support whose warmth and responsiveness contribute to well-being (Díaz-Aguado et al., 2018; Jiménez-Iglesias et al., 2017). Therefore, the present study extends this evidence by exploring TSR in a Spanish sample, where teachers are perceived not only as academic guides but also as emotionally supportive figures contributing to adolescents’ psychological adjustment (Cabello-Sanz & González-Benito, 2022). In fact, based on the Prosocial Classroom Model, teachers’ ability to process and manage emotions, even in stressful situations, might have an impact on TSR (Jennings et al., 2021). Consequently, a teacher’s EI may facilitate the development of strategies that promote TSR. Some studies have found that teachers with higher EI show better positive relationships with their students (Bean, 2020; Poulou, 2017a, 2017b; Wang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023). In short, considering the theoretical Prosocial Classroom Model and empirical research, the TSR factor might be one of the mediating variables that clarifies the relationship between TEIB and PIU. The Mediating Role of Stress A likely candidate to mediate the relationship between teachers’ behavior and PIU is adolescents’ stress. Stress is a multidimensional response to perceived demands that exceed an individual’s adaptive capacities. During adolescence, stress often emerges from academic pressures, peer relationships, and concerns about identity and future goals (Colten & Gore, 2017). In school contexts, stress is particularly relevant because it is shaped by students’ perceptions of the social and emotional climate created by teachers and peers (Núñez-Regueiro & Núñez-Regueiro, 2021). According to the I-PACE model (Brand et al., 2016), stress is a key cognitive-affective factor that contributes to the development and maintenance of PIU. The model posits that individuals with high levels of stress may experience negative emotional states which lead them to seek immediate relief through internet-related activities (Mehmood et al., 2021). As a result, stress functions as a trigger that increases both cue-reactivity and craving, reinforcing compulsive online behaviors. According to the Compensatory Internet Use Model (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), stress acts as a key motivational driver of PIU which creates emotional discomfort and leads individuals to seek temporary relief and distraction through internet-based activities. In this sense, previous studies have found that adolescents perceiving their context as more stressful were likely to report more PIU (Chen et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2023). Stress might disrupt emotional regulation skills and depleting cognitive resources, which may increase the tendency to seek short-term relief and distraction through online activities (Lam & Wong, 2015). Persistent exposure to academic or social stressors has been associated with greater emotional distress along with a heightened need for compensatory experiences, reinforcing maladaptive patterns of use (Chen et al., 2025; Shen et al., 2023). Moreover, when stress occurs with difficulties in self-control or anxiety, adolescents may become especially prone to compulsive online behaviors (Gong et al., 2021; Song & Park, 2019). Altogether, these findings suggest that stress functions as a motivational and affective mechanism that increases susceptibility to PIU, particularly when adolescents lack adaptive coping resources or emotionally supportive environments. According to the Prosocial Classroom Model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), a positive classroom climate is characterized by low levels of conflict, appropriate emotional expression, and supportive relationships. Thereby, when teachers effectively use, express, and manage emotions they improve their relationships with students and create and maintain a safe classroom where students feel connected, engaged in learning, and safe (Jennings et al., 2021; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009). Thus, teachers with good relationships with their students may foster more positive classroom environments, reducing stress, and inspiring healthy coping skills in students (Ahnert et al., 2012; Walker & Graham, 2021). Therefore, students’ perceptions of their teachers’ EI may strengthen teacher-student relationships and reduce the extent to which students perceive situations as stressful. Consequently, the TSR factor and stress may be serial mediators in the relationship between TEIB and PIU. Despite the increasing literature on PIU, there remain substantial gaps in the knowledge, specifically regarding the role of teachers. Based on the aforementioned theoretical approaches and empirical research, the present study we aimed to test a serial mediation model where TSR and stress sequentially mediate the link between TEIB and PIU. The serial mediation model represents an advancement over simple mediation models, as it enables a deeper understanding of in the relationship between TEIB and PIU by examining interconnected mechanisms simultaneously. Thus, elucidating these underlying mechanisms not only contributes significantly to theoretical refinement but also fosters advancements in strategies aimed at preventing PIU during adolescence. Altogether, this work builds upon existing theoretical perspectives by applying their assumptions to an educational context that emphasizes interpersonal and environmental influences. Specifically, while the I-PACE model emphasizes cognitive–affective mechanisms underlying PIU, our approach focuses on an interpersonal and environmental perspective by including teachers’ behaviors as contextual sources of influence. Similarly, whereas the Compensatory Internet Use Model highlights the role of internal stressors driving problematic online behavior, the present study focuses on how stress may be shaped by external conditions within the school environment. In this way, our work bridges theoretical models of individual vulnerability with ecological approaches, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the interplay between personal and contextual determinants of adolescent PIU. In this regard, the present study offers several contributions to the literature on PIU by providing a novel perspective on how teacher-related emotional factors may influence adolescents’ digital behaviors. In addition, this paper helps bridge emotional and contextual perspectives on adolescent adjustment, complementing existing frameworks such as the Prosocial Classroom and I-PACE models. Finally, the findings may inform teacher education and school-based interventions aimed at fostering emotionally supportive classroom climates that protect students from stress and maladaptive technology use. Two studies were conducted to verify the indirect relationship between TEIB and PIU through the same serial mediation mechanism. Study 1 employed a cross-sectional design and Study 2 used a nine-month prospective design to examine whether this mechanism is maintained over time. We also used different measures of stress in each study to broaden the generalizability of our findings: stress symptoms reflecting a physiological component in Study 1 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) and perceived stress reflecting a cognitive component in Study 2 (Cohen et al., 1983). To ensure a stringent test of the proposed model, covariates were included. We included age and gender in both studies, EI in study 2 and CER strategies in study 1, as covariates to control for confounding effects identified in previous research (Arrivillaga et al., 2023; Arrivillaga et al., 2020; Chi et al., 2020). Thus, the present research examines whether TEIB, as perceived by adolescents, predicts lower PIU through the sequential mediating roles of TSR and stress, using both cross-sectional and prospective designs. Taken together, these two studies provide a complementary test of the proposed serial mediation model, depicted in Figure 1, setting the basis for the following hypotheses:

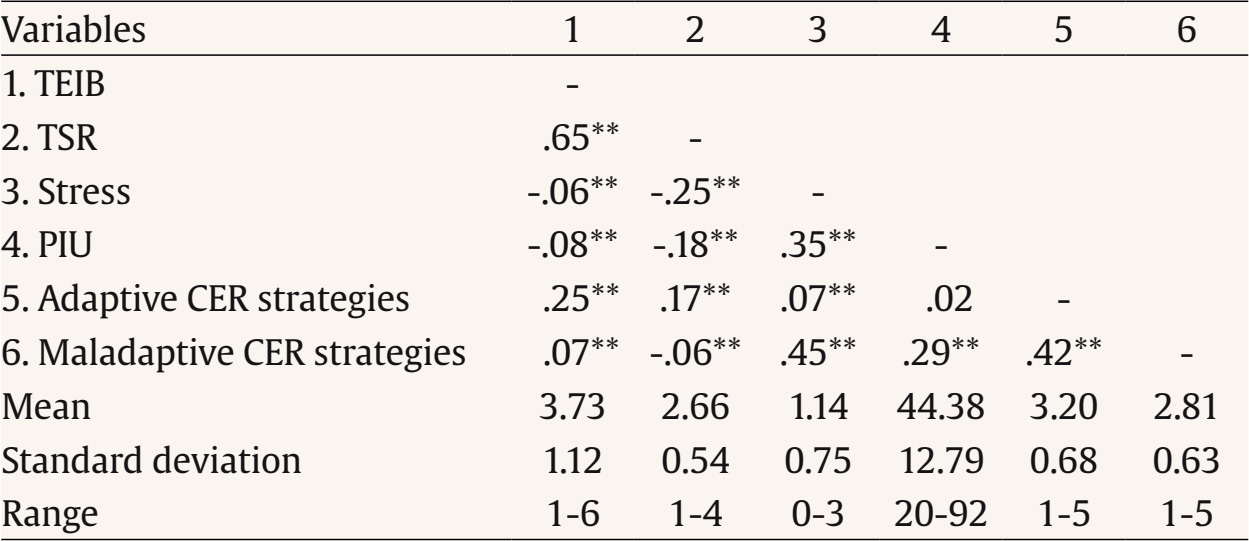

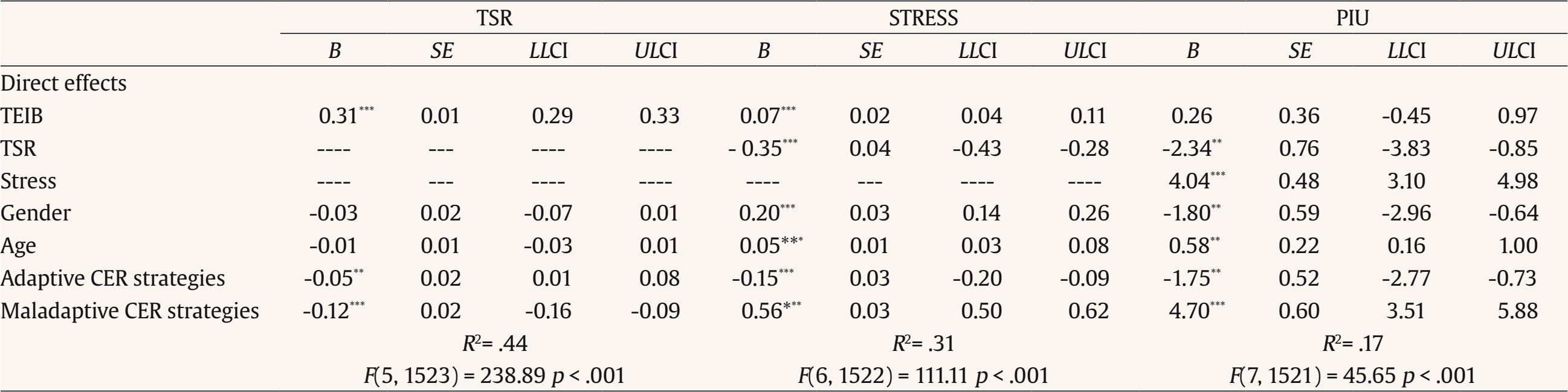

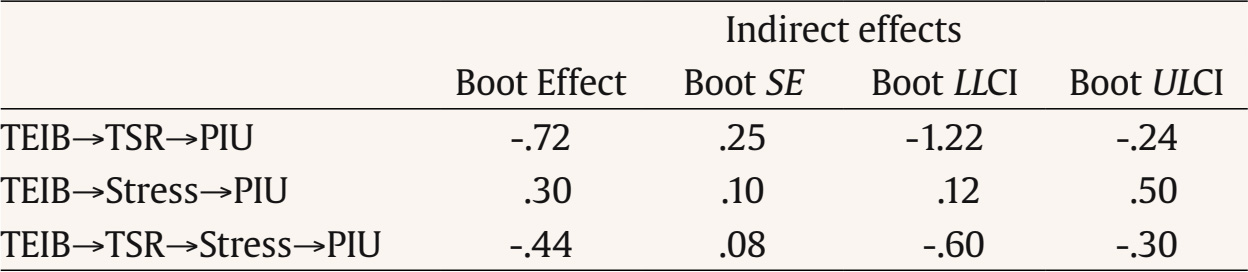

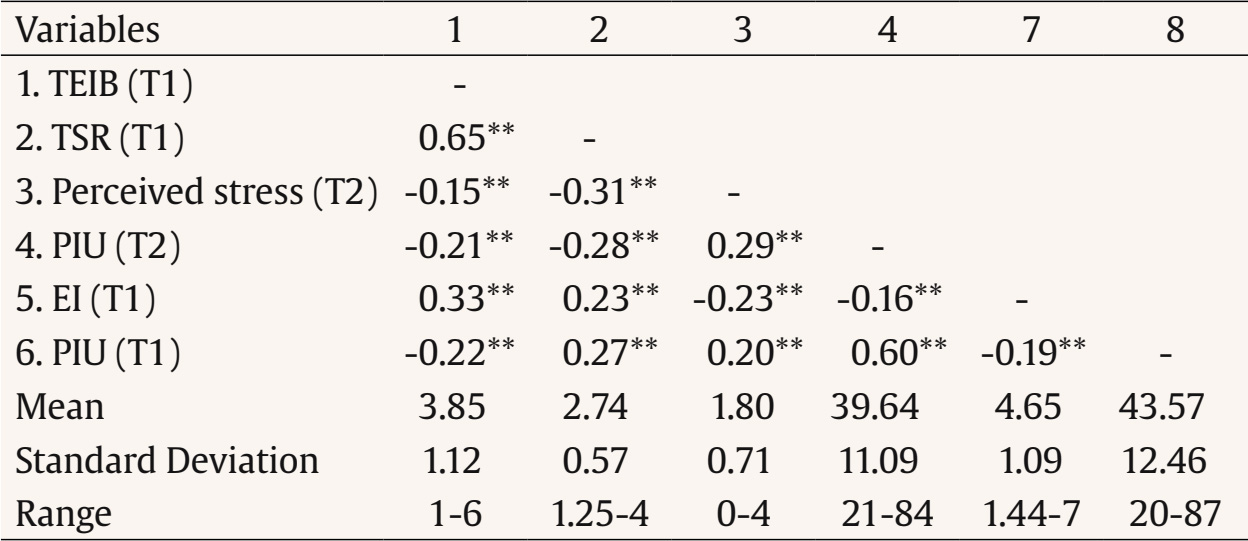

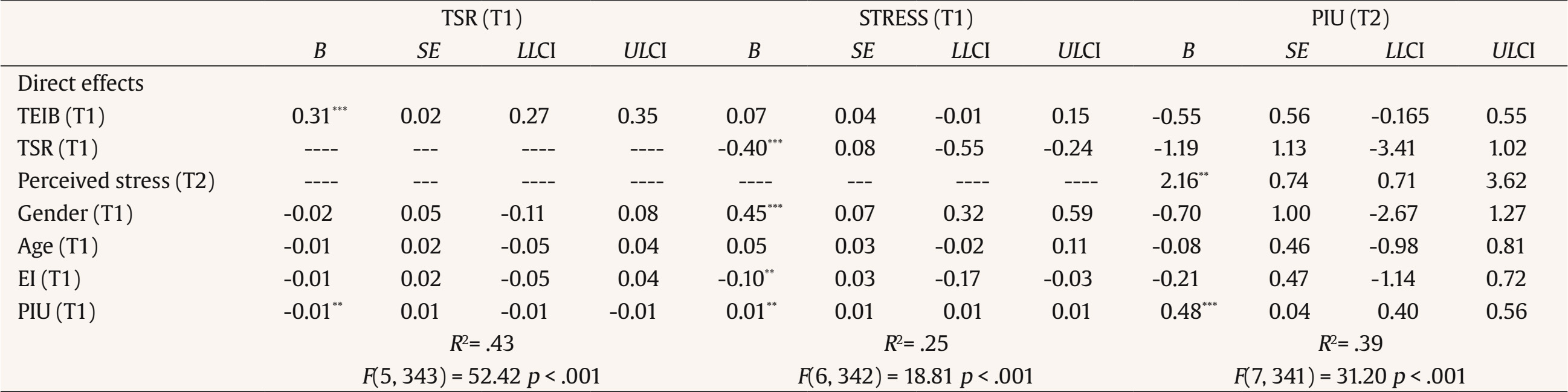

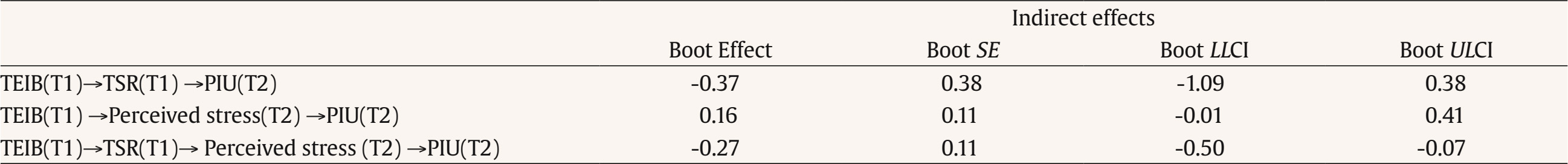

Method Participants and Procedure The participants were 1,966 adolescents (boys = 45.9%, girls = 52.6%, transgender = 0.1%, non-binary = 0.4%) from 10 high schools in southern Spain. Their ages ranged from 12 to 18 years (M = 14.17, SD = 1.45). Most participants were Spanish (88%), with 207 individuals holding other nationalities (10.6%) and 28 not reporting their nationality (1.4%). Regarding their academic level, 21.2% were enrolled in the first year of compulsory secondary education, 21% in the second year, 28.3% in the third year, and 25.5% in the fourth year. A smaller proportion of students attended baccalaureate programs, with 2.5% in their first year and 1.4% in their second year. This study began with an initial briefing to the principals of the participating educational centers, who provided written informed consent for their institutions to take part. Parents or legal guardians were informed about the study’s objectives and procedures through communication from the educational centers. In six of the 10 participating centers, families actively provided informed consent, explicitly granting permission for their adolescents’ participation. In the remaining four centers, a passive consent approach was adopted, meaning that families implicitly approved participation unless they explicitly refused. Data collection took place during regular school hours, with adolescents dedicating up to 2 hours to completing the questionnaire battery. The process was conducted under the supervision of a researcher and at least one teacher to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Malaga (169-2023-H). Instruments Teacher Emotionally Intelligent Behavior. This was measured with the Spanish adaptation and translation (Extremera et al., 2025) of the original scale called the Emotionally Intelligent Behavior scale among supervisors (EIB; Ivcevic et al., 2021). The TEIB scale was adapted to the academic context from the original supervisor version by replacing the terms “supervisor” with “teacher/tutor,” “employees” with “students,” and “at work” with “in the classroom.” This 11-item Likert-type scale was used to ask students about behaviors showing that their teachers/tutors successfully perceived emotions used emotions to help thinking and inspired or assisted problem-solving, understood the causes and consequences of emotions, and managed emotions in themselves and their classrooms, with scoring on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree) (e.g., “My tutor realizes when people are dissatisfied in class”; “My tutor is good at helping others feel better when they are disappointed or upset”). The Spanish version of the TEIB scale has shown satisfactory psychometric properties (Extremera et al., 2025). In this study, the reliability of the scale was excellent (α = .93). Teacher-Student Relationship. It was measured with the Inventory of Teacher-Student Relationships (ITSR; Murray & Zvoch, 2010). The inventory contains 17 items scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The ITSR is a student-report measure of three dimensions of teacher-student relationships: trust (e.g., “I trust my teacher”), communication (e.g., “My teacher understands me”), and alienation (e.g., “I get upset easily at school,” reverse scored). A mean score of all the items was calculated, so higher scores indicated more positive TSR. Prior research that used the Spanish version had demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Chamizo-Nieto et al., 2021). In this study, the reliability of the scale was good (α = .86). Stress Symptoms. These were measured with the Stress Subscale of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) Spanish validation (Bados et al., 2005). This subscale consists of 7 items scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). The subscale evaluates the stress symptoms experienced (e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”). A mean score of all items was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater stress symptomatology. In this study, the reliability of the subscale was good (α = .84). Problematic Internet Use. It was measured with the Internet Addiction Test (IAT; Young, 2009) Spanish validation (Puerta-Cortés et al., 2012). The IAT consists of 20 items scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (rarely) to 5 (always). This scale evaluates the extent to which internet use impacts daily routines, social life, productivity, sleep patterns, and emotions (e.g., “How often do you find that you stay online longer than you intended?”). A mean score of all the items was calculated, with higher scores indicating higher PIU. In this study, the reliability of the scale was good (α = .86). Adaptive and Maladaptive Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies. These were measured with the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; Garnefski et al., 2002) Spanish validation (Chamizo-Nieto et al., 2020). The scale consists of 36 items with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The adaptive dimension (e.g., “I think that I can learn from it”) includes five strategies: putting into perspective, acceptance, positive refocusing, refocus on planning, and positive reappraisal. The maladaptive subscales (e.g., “I think that it’s my own fault”) include four strategies: self-blame, blaming others, catastrophizing, and rumination. In this study, reliability was good for the adaptive dimension (α = .87) and for the maladaptive dimension (α = .82). Analysis Plan IBM’s SPSS Statistics 25 was used to conduct the analyses. First, descriptive analyses and correlations were performed between all variables. Then, Model 6 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) was used to test the serial mediation model. In the serial mediation model, TEIB was introduced as the independent variable, TSR as the first mediator, stress as the second mediator, and PIU as the dependent variable. In the serial mediation analysis, age, gender, and CERQ strategies were entered as covariates. The study followed the standard procedure, and we performed bootstrapped bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI), using 5,000 bootstrapped samples, so an effect was considered significant if the 95% CI did not include zero. Results Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Results Table 1 shows the descriptive and correlation results among the study variables. As expected, TEIB was significantly and positively related to TSR, and negatively with stress symptoms and PIU. TSR was negatively related to stress symptoms and PIU, and stress symptoms positively related to PIU. Adaptive CER strategies correlated significantly and positively with TEIB, TSR, stress symptoms, and age. The maladaptive CER strategies correlated significantly and positively with stress symptoms, PIU, TEIB, and adaptive CER strategies and negatively with TSR. Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables   Note. N ranged between 1,578 and 1,820 due to missing data. Abbreviations: TEIB = teacher emotional intelligent behaviors; TSR = teacher-student relationships; PIU = problematic internet use. *p < .05, **p < .01. Serial Mediation Results The results showed that the total effect model was significant (B = -0.61, SE = 0.29, 95% CI [-1.17, -0.04]) and explained 12.1% of the variance of PIU, F(5, 1523) = 41.86, p < .001. However, the direct effect of TEIB on PIU was nonsignificant after the two mediators were included in the analysis (B = 0.26, SE = 0.36, 95% CI [-0.45, 0.97]). The direct effects of mediators showed that TEIB significantly and positively predicted TSR (B = 0.31, SE = 0.01, 95% CI [.29, .33]) and significantly and negatively predicted stress symptoms (B = 0.07, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.04, 0.11]). TSR negatively predicted stress symptoms (B = -0.35, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.43, -0.28]) and negatively predicted PIU (B = -2.34, SE = 0.76, 95% CI [-3.83, -0.85]). Moreover, stress symptoms positively predicted PIU (B = 4.04, SE = .48, 95% CI [3.10, 4.98]). In short, the main direct effects shown in Table 2 were all significant except for the direct effect of TEIB on PIU. All the covariables showed significant direct effects on PIU: Gender (B = -1.80, SE = .59, 95% CI [-2.96, -.64]) and adaptive CER strategies (B = -1.75, SE = 0.52, 95% CI [-2.77, -0.73]) were negative predictors and age (B = 0.58, SE = 0.22, 95% CI [0.16, 1.00]) and maladaptive CER strategies (B = 4.70, SE = 0.60, 95% CI [3.51, 5.88]) were positive predictors. Table 2 Coefficients of the Mediation Analysis   Note. N = 1529 due to missing data; B = unstandardized beta. SE B = standard error. 95% CI = confidence interval with lower and upper limits; TEIB = teacher emotional intelligent behaviors; TSR = teacher-student relationships; PIU = problematic internet use. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Once the effects of covariates were controlled for, the main indirect effects shown in Table 3 indicate that the three contrasted mediations were significant. First, TSR mediated the relation-ship between TEIB and PIU (Boot effect = -0.72, Boot SE = 0.25, 95% Boot CI [-1.22, -0.24]). Second, stress symptoms mediated the relationship between TEIB and PIU (Boot effect = -0.30, Boot SE = 0.10, 95% Boot CI [0.12, 0.50]). Third, TSR and stress symptoms sequentially mediated the relationship between TEIB and PIU (Boot effect = -0.44, Boot SE = 0.08, 95% Boot CI [-0.60, -0.30]). Thus, the specific indirect effect of TEIB on PIU through the two mediators in serial was significant. Therefore, TEIB was associated with higher TSR which subsequently was negatively linked with stress symptoms, and lower stress symptoms were associated with lower PIU. Table 3 Coefficients of the Indirect Effects of the Mediation Analysis   Note. B = unstandardized beta. SE B = standard error. 95% CI = confidence interval with lower and upper limits. Boot = statistics for the indirect effects are the result of the bootstrapping method. TEIB = teacher emotional intelligent behaviors; TSR = teacher-student relationships; PIU = problematic internet use. Indirect effects were estimated including all the covariates (age, gender, adaptive CER strategies, and maladaptive CER strategies). Method Participants and Procedure A sample of 919 adolescents initially participated in this study. However, at the second wave conducted 9 months later, 517 adolescents were retained, with 402 lost to follow-up. Only participants who completed both waves were included in our analyses. The sample was comprised of 517 adolescents (boys = 45.1%, girls = 54.5%, transgender = 0.2%, non-binary = 0.2%) from five educational centers in southern Spain. Their ages ranged from 12 to 16 years at T1 (M = 13.41, SD = 1.06). Nine months later, during the second wave (T2), their ages now ranged from 12 to 17 years (M = 14.14, SD = 1.03). Regarding their academic level, at T1, 34.2% were in the first year of compulsory secondary education, 30.8% in the second year, 34.8% in the third year, and 0.2% in the fourth year. At T2, 0.8% were in the first year, 34.4% in the second year, 32.3% in the third year, and 32.5% in the fourth year, reflecting the academic progression of participants over the 9 months between waves. Most participants were Spanish (89.6%), while 54 individuals held other nationalities (10.4%). This prospective study involved five educational centers. Principals were briefed about the study and provided written informed consent for their institutions to participate. Parents or legal guardians were informed about the study’s objectives and procedures through communication from the educational centers. In two of the participating centers, families actively provided informed consent, explicitly granting permission for their adolescents’ participation. In the remaining three centers, a passive consent approach was adopted, meaning that families implicitly approved participation unless they explicitly refused. The first wave of data collection (T1) took place during January of 2023 in regular school hours, with adolescents dedicating up to 2 hours to completing the questionnaire battery. Nine months later, in October, during the second wave (T2), data collection was conducted again during school hours, but adolescents required only 1 hour to complete the battery. To ensure the prospective matching of responses while maintaining confidentiality, participants used anonymous nicknames to pair their responses across T1 and T2. Both waves were conducted under the supervision of a researcher and at least one teacher to guarantee confidentiality and anonymity. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Malaga (169-2023-H). Instruments To measure TEIB, TSR, and PIU, the same scales as in Study 1 were used. In this study, TEIB (α = .93), TSR (α = .87), and PIU at T1 (α = .85) and at T2 (α = .85) showed satisfactory reliability. Perceived Stress. This was measured with the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10; Cohen et al., 1983), Spanish validation (Remor, 2006). This scale contains 10 items scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). The PSS-10 measures the extent to which situations in life are perceived as stressful (e.g., “How often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”). A mean score of all the items was calculated, with higher scores indicating higher perceived stress levels. In this study, the reliability of the scale was acceptable (α = .77). EI. It was measured with the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS; Wong & Law, 2002) Spanish validation (Extremera et al., 2019). The scale consists of 16 items scored on a Likert-type scale from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). This scale assesses four dimensions: self-emotion appraisal, other-emotion appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. All items are averaged, and higher scores indicate higher EI (e.g., “I have good control of my own emotions”). In this study, the reliability of the scale was good (α = .88). Analysis Plan IBM’s SPSS Statistics 25 was used to conduct the analyses. First, descriptive analyses and correlations were performed between all variables. Then, Model 6 of the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) was used to test the serial mediation model. In the serial mediation model, TEIB (measured at T1) was introduced as the independent variable; TSR (measured at T1) as first mediator, perceived stress as second mediator (measured at T2), and PIU as the dependent variable (measured at T2). In the serial mediation analysis, age, gender, EI, and PIU at T1 were entered as covariates. Standard procedures were followed (see the description of Study 1). Results Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Results Table 4 shows the descriptive and correlational results among the study variables. TEIB was significantly and positively related to TSR and negatively with perceived stress and PIU. TSR was negatively related to perceived stress and PIU, and perceived stress positively related to PIU. EI correlated positively with TEIB and TSR and negatively with perceived stress and PIU. PIU measured at T1 correlated negatively with TEIB and EI and positively with TSR, perceived stress, and PIU measured at T2. Table 4 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Study Variables   Note. N ranged between 352 and 514 due to missing data; Abbreviations: TEIB = teacher emotional intelligent behaviors; TSR = teacher-student relationships; PIU = problematic internet use; EI = emotional intelligence. *p < .05, **p < .01. Serial Mediation Results The results showed that the total effect model was significant (B = -1.03, SE = 0.45, 95% CI [-1.91, -0.14]) and explained 37% of the variance of PIU, F(5, 343) = 40.09, p < .001. However, the direct effect of TEIB on PIU was nonsignificant after the two mediators were included in the analysis (B = -0.55, SE = 0.56, 95% CI [-1.65, 0.55]). The direct effects of mediators showed that TEIB significantly and positively predicted TSR (B = 0.31, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [0.27, 0.35]) but did not significantly predict perceived stress (B = 0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [-0.01, 0.15]). TSR negatively predicted perceived stress (B = -0.40, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [-0.55, -0.24]) and did not significantly predict PIU (B = -1.19, SE = 1.13, 95% CI [-3.41, 1.02]), whereas perceived stress positively predicted PIU (B = 2.16, SE = 0.74, 95% CI [0.71, 3.62]). In short, the main direct effects in Table 5 show that only the serial mediation paths were significant, and for neither the direct effect of TEIB nor the simple mediation paths. The only covariate that significantly predicted PIU (T2) was PIU at T1 (B = 0.48, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [0.40, 0.56]). Table 5 Coefficients of the Mediation Analysis   Note. N = 349 due to missing data; B = unstandardized beta. SE B = standard error. 95% CI = confidence interval with lower and upper limits; TEIB = teacher emotional intelligent behaviors; TSR = teacher-student relationships; PIU = problematic internet use; EI = emotional intelligence. *p < .05, **p < .01; ***p < .001. Once the effects of covariates were controlled for, the main indirect effects shown in Table 6 indicate that only the serial mediation path was significant. First, TSR did not mediate the relation-ship between TEIB and PIU (Boot effect = -0.37, Boot SE = 0.38, 95% Boot CI [-1.09, 0.38]). Second, perceived stress did not mediate the relationship between TEIB and PIU (Boot effect = 0.16, Boot SE = 0.11, 95% Boot CI [-0.01, 0.41]). Third, TSR and perceived stress sequentially mediated the relationship between TEIB and PIU (Boot effect = -0.27, Boot SE = 0.11, 95% Boot CI [-0.50, -0.07]). Thus, the specific indirect effect of TEIB on PIU through the two mediators in serial was the only significant path. Therefore, TEIB was associated with higher TSR which subsequently was negatively linked with perceived stress, and then lower perceived stress was associated with lower PIU. Table 6 Coefficients of the Indirect Effects of the Mediation Analysis   Note. B = unstandardized beta. SE B = standard error. 95% CI = confidence interval with lower and upper limits. Boot = statistics for the indirect effects are the result of the bootstrapping method. TEIB = teacher emotional intelligent behaviors; TSR = teacher-student relationships; PIU = Problematic internet use. Indirect effects were estimated including all covariates (age, gender, emotional intelligence, and baseline PIU [T1]). In the present research, two studies were conducted that used a cross-sectional design in Study 1 and a 9-month prospective design in Study 2 to test the link between TEIB and PIU in a serial mediation path with TSR and stress as potential serial mediators. The main findings of these studies add knowledge to the current literature by increasing the importance of teachers’ EI in addressing and preventing PIU in adolescents. Regarding the first hypothesis, our results support the expected negative relation between TEIB and PIU in both studies. These findings underscore new findings in research literature to the best of our knowledge, while no studies had yet examined students’ perceptions of their teachers’ EI abilities in relation to PIU and neither teachers’ EI nor adolescents’ PIU. However, this finding is in line with past research that examined the link between teacher EI and student outcomes, that is, academic achievement (Alam & Ahmad, 2018; Singh & Ryhal, 2023), improved student social and emotional competencies (Brackett & Katulak, 2007; Poulou, 2017b; Skura & widerska, 2022), enhanced self-esteem (Curci et al., 2014), and cyberbullying (Mérida-López et al., 2025), which are constructs directly related to PIU. Conversely, TEIB was positively linked to TSR and negatively to both stress symptoms and perceived stress. In this sense, students who perceived their teacher as emotionally intelligent reported a more positive TSR (Bean, 2020; Poulou, 2017a), therefore, it is possible that students who perceive their teacher as supportive and responsive to their emotional needs may feel more protected and better equipped to cope with daily stressors in classrooms (Romano et al., 2020). Another noteworthy finding was the positive link between stress symptoms in Study 1 and perceived stress in Study 2 with PIU. These results cohered with prior longitudinal research that demonstrated that stressful life events are significant risk factors and may contribute to the longitudinal development of PIU among adolescents (Xiao et al., 2019). Thus, our research provides some preliminary generalization about stress dimensions. That is, while in Study 1 we used stress symptoms, which refer to a state of tension and permanent arousal (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995), which is more related to physiological dimensions of stress, in Study 2 we used a well-known perceived stress measure, which refers to perceiving the situations in life as stressful and the degree respondents experience life as unpredictable, uncontrollable, or overloaded (Cohen et al., 1983). Our results showed that in both studies, adolescents who reported higher stress via different scales (either measuring physiological or cognitive dimensions) also reported more PIU; thus, our results generalized across different measures, making our conclusions more robust. Regarding our second hypothesis, both were supported, so that TEIB indirectly predicted negatively PIU through the serial mediation path of TSR and stress. Thus, adolescents who perceived that their teachers showed more emotionally intelligent behaviors experienced a more positive relationship since they probably perceived support and interest from their teachers (Jennings et al., 2021). In turn, this support from teachers might create a more positive climate that favors adolescents’ not turning to the Internet for emotional relief (Zhou et al., 2020). Our findings from both studies were in line with these assumptions. First, TEIB showed a positive link with TSR, in accordance with past research, and teachers with high emotional abilities can cultivate better positive relationships with their students (Poulou, 2017b; W. Zhang et al., 2023). Second, TSR revealed a negative effect on stress, suggesting that having positive relationships with students may create a safe and warm environment where adolescents can feel less tense and perceive the situation as more controllable (Ahnert et al., 2012; Walker & Graham, 2021). Third, a positive relation between stress and PIU was found, suggesting that overwhelmed adolescents may engage in more PIU (Gong et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2023). Based on the Prosocial Classroom Model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Jennings et al., 2021), when teachers put into practice emotionally intelligent behaviors in interactions in classrooms, adolescents may trust their educators’ competencies more and might feel more confident and willing to seek support (Frenzel et al., 2021). Similarly, students who identify their teachers as acting in emotionally intelligent ways may experience more positive emotions and perceive less stress, which may reduce the likelihood of turning to the Internet for emotional compensation (Jia et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2024; Shi et al., 2023). This is in line with the I-PACE model (Brand et al., 2016). According to this model, adolescents who perceive lower levels of stress may be less likely to experience negative emotional states that drive them to seek immediate relief through internet-related activities (Mehmood et al., 2021). Similarly, in line with the compensation model (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), our findings give some credence to the idea that emotionally intelligent teachers might create safer, warmer, and less stressful environments for their students and therefore these adolescents may tend to seek temporary relief and distraction through internet-based activities less often. Another noteworthy finding, while both studies supported the hypothesized serial mediation, the direct association between TEIB and PIU was only significant in the cross-sectional study. This pattern suggests that the influence of TEIB on adolescents’ digital behaviors may be more immediate when assessed concurrently, reflecting proximal perceptions of teacher emotionally intelligent behaviors. Over time, however, these effects appear to operate primarily through more stable interpersonal and emotional processes, such as the quality of TSR and students’ stress levels. This aligns with the Prosocial Classroom Model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), which posits that teachers’ emotional competencies shape student outcomes indirectly through sustained relational and affective mechanisms. From a methodological perspective, the inclusion of baseline PIU in the prospective model likely reduced the residual variance in PIU at T2, further highlighting that long-term effects are transmitted mainly through these mediating pathways rather than through direct associations. Regarding the covariates, several significant effects emerged, particularly in Study 1. Gender and age were associated with PIU, with boys and older adolescents reporting higher levels, consistent with previous findings (Chi et al., 2020). Adaptive and maladaptive CER strategies were negatively and positively related to PIU, respectively, also in line with prior evidence (Arrivillaga et al., 2023). In Study 2, the only significant covariate was baseline PIU, as expected given the relative temporal stability of this construct (Yu & Shek, 2013). Given these considerations, both models remained significant, above the covariates, thus providing further strong evidence for the underlying mechanisms in the teachers’ EI-PIU link. Moreover, testing within cross-sectional and prospective studies provides generalization of our findings, due to the replicability which are scarce in psychology (Patil et al., 2016). Overall, our findings highlight the importance of the school context and the role of teachers not only as providers of knowledge, often under strict time constraints, but also as facilitators of prosocial behaviors as a positive teacher-student relationships characterized by warmth, trust, and caring can help students who are becoming preoccupied with the Internet (Zhou et al., 2020). Theoretical and Practical Implications The present research has made several contributions regarding the importance of teachers’ emotional abilities in relation to PIU and has provided some preliminary evidence for the underlying mechanisms involved. First, our findings are in line with the Prosocial Classroom Model (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009), the evidence supporting that teachers’ emotional competencies showed an impact over social-emotional outcomes under some mediating dimensions. While some prior research had linked teacher EI with student social-emotional competencies (e.g., Skura & widerska, 2022), academic success (e.g., Singh & Ryhal, 2023), and reduced cyberbullying behaviors (Mérida-López et al., 2025), our research suggests a new pathway in which TEIB fosters high-quality TSR, which subsequently relates to less stress and less PIU. This supports the notion that perceptions of emotionally intelligent behaviors in teachers do not only enhance students’ emotional and academic outcomes but also play a role in preventing maladaptive behaviors related to internet use. Moreover, these findings contribute to broader theoretical perspectives on PIU (e.g., I-PACE model) by emphasizing the role of contextual factors in modulating stress-related pathways that lead to excessive internet use. While studies of PIU have often focused on individual factors (Anderson et al., 2017), our study suggests that school environment factors, particularly emotionally supportive teachers, can act as a preventive factor against stress-driven internet use. In this sense, teachers may discourage students from engaging in PIU by reducing the stress that fuels maladaptive digital behaviors. Future research should further explore the broader school climate and peer interactions as additional contextual variables that may interact with these mechanisms to influence adolescent online behaviors. Finally, the current research emphasizes the importance of emotionally competent teachers in school contexts for adolescent development (Chemnad et al., 2023). The findings indicate that emotionally intelligent teachers can contribute to school climates that meet adolescents’ psychological needs for support and stability which, in turn, could prevent PIU. Regarding the practical implications, the findings suggest that integrating EI training into professional development programs could equip teachers with better strategies to manage daily teaching (Gimbert et al., 2023; Pozo-Rico et al., 2023). These programs not only improve their own well-being but also strengthen their capacity to connect with students (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Özdemir Cihan & Dilekmen, 2024). In line with recent recommendations, EI development should be addressed both during pre-service teacher education and through ongoing in-service training, ensuring that emotional skills are cultivated throughout teachers’ professional trajectories (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Özdemir Cihan & Dilekmen, 2024). These initiatives combine personal and professional development by first helping teachers strengthen their own emotion regulation abilities and then transferring these skills to classroom interactions and daily routines (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Schools can evaluate the impact of such training through indicators such as improvements in classroom climate, TSR, and students’ social and emotional competencies (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Oliveira et al., 2021). In this sense, educational institutions should integrate EI training into teacher preparation and professional development programs (Molina-Moreno et al., 2024; Oliveira et al., 2021). In short, teachers should play a key role in tackling the rise of PIU among adolescents by receiving training in both the positive use of technology and emotional competencies as a preventive mechanism against the emergence of PIU. Beyond individual classroom practices, these findings also hold broader implications for educational and public policy. As adolescents’ online behaviors increasingly intersect with their academic and social lives, schools and education authorities could integrate digital well-being programs that complement emotional competence training for teachers (Estes et al., 2022). Such initiatives may include explicit modules on managing students’ stress and digital habits, fostering responsible technology use, and promoting emotionally supportive learning environments. At a policy level, incorporating teacher EI into professional standards and curriculum design could strengthen systemic efforts to prevent PIU and support students’ overall psychological well-being (Estes et al., 2022). Limitations The results of our study must also be viewed in the light of several study limitations. First, we used self-report questionnaires, which may potentially introduce biases from common method variance, and we only assessed the students’ perceptions to address teacher EI or TSR. Future research should explore whether teacher EI shows similar patterns by using both observer-rated EI instruments or typical EI assessments, both through self-report measures or via performance-based EI tests of teachers. These would serve to strengthen the existing evidence regarding teacher EI, particularly in relation to observers’ ratings of emotion abilities. As previous findings suggested that observed-rated EI shows greater predictive validity than self-rated EI (Elfenbein et al., 2015), this research deserves further investigation. Second, in the present research we used a general measure to assess current internet usage patterns. While the IAT is one of the most widely used questionnaires for assessing internet-use behaviors and symptoms, it does not differentiate between various types of internet use (e.g., gaming, smartphone, study-related use). Future studies should focus on using more specific measures to determine which specific behaviors are most impacted by teachers. Third, although this study adopted a prospective design, the analyses were correlational in nature and therefore do not allow for causal conclusions. Future research should employ longitudinal designs with additional time points that enable testing of temporal and reciprocal relationships among the study variables. The use of more advanced longitudinal approaches, such as cross-lagged panel models or random-intercept cross-lagged panel models, could help disentangle within- and between-person effects over time and provide stronger evidence regarding the directionality of the observed associations (Erdem et al., 2025; Torres et al., 2024). Fourth, future research should account for the duration, frequency, and familiarity of students, with the teachers being evaluated (i.e., using some screening measures of personal acquaintances). Perhaps students with greater familiarity possess a broader base of personal experience, potentially resulting in more accurate and meaningful assessments. Despite these limitations, our studies hopefully offer a basis for further research on TEIB as a potential school-related factor related to the prevalence of PIU during adolescence. Fifth, the longitudinal design of Study 2 involved a relatively high attrition rate (approximately 44%), which is a common challenge in multi-wave data collection (Twisk & De Vente, 2002). Although attrition may have introduced some bias, the remaining sample size was adequate to conduct the proposed analyses and draw reliable conclusions. Future studies should aim to minimize participant loss by reducing the time between waves, using digital follow-up procedures, or providing additional incentives for participation. Finally, although the present research provides novel evidence from a Southern European context, cross-cultural comparisons are needed to determine the generalizability of these mechanisms. Differences in teacher-student interaction styles and emotional display norms across educational systems may moderate the associations between teacher EI, classroom relationships, and adolescent PIU. Future studies could adopt multi-cultural designs to explore whether these processes operate similarly in more hierarchical or less relational teacher cultures. Conclusion The present research has provided compelling evidence for the critical role of teacher EI behaviors in preventing PIU among adolescents. By effectively managing and expressing emotions in classrooms, teachers can cultivate positive TSR and contribute to lower levels of student stress, which are in turn linked to reduced PIU. These findings support the theoretical framework of the Prosocial Classroom Model as well as the importance of emotionally competent teachers in school contexts for adolescents’ responsible and adaptive internet use. Educational institutions should integrate EI training into teacher training programs as the competencies teachers possess are important in the prevention of PIU in adolescents. Future studies should build on these findings by examining other school-based and relational processes that may buffer or exacerbate adolescents’ online behaviors, such as school climate. Longitudinal and multilevel approaches could further clarify how classroom-level emotional dynamics shape digital behaviors over time. Expanding this line of inquiry could inform both preventive interventions and evidence-based policies aimed at fostering healthier, and a more balanced technology use among youth. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Gómez-Hombrados, J. & Extremera, N. (2026). The social perception of teachers’ emotional intelligence and problematic internet use among Spanish adolescents: A serial mediation model involving teacher-student relationships and stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260812. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a4 Funding This work was part of the R+D+i project PID2020-117006RB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/ and Group CTS-1048G-FEDER (Junta de Andalucía). The first author was supported by Spanish Ministry of Universities (FPU21/02323). |

Cite this article as: Gómez-Hombrados, J. & Extremera, N. (2026). The Social Perception of Teachers’ Emotional Intelligence and Problematic Internet Use among Spanish Adolescents: A Serial Mediation Model Involving Teacher-Student Relationships and Stress. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260812. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a4

Correspondence: jorgegh@uma.es (J. Gómez-Hombrados)Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS