Defender, Passive, and Pro-Bully: Exploring Bystanders’ Intentions toward Cyberbullying

Cirenia Quintana-Orts1, Ana Alcántara-Lázaro2, Joaquín A. Mora-Merchán2, & Rosario Del Rey2

1Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Malaga, Spain; 2Department of Developmental and Educational Psychology, University of Seville, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a3

Received 31 January 2025, Accepted 11 November 2025

Abstract

Objective: The present study examines the usefulness of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) in explaining three distinct responses to cyberbullying among adolescents: defending, pro-bully, and passive intentions. A model was constructed to assess intentions, including control variables (gender, age, cyberbullying victimization, and perpetration experiences), social norms (family, friends, and teachers), attitude toward helping cyberbullying victims, perceived behavioral control, and empathy. Method: Data were collected from 2,539 students aged 11 to 18 years (M = 14.07, SD = 1.39) across eighteen schools. The analyses focused on the sample of non-witnesses of cyberbullying (N = 1,825) to assess intentions, using multiple regression analyses. Results: Empathy and helping attitude play a significant role in the intention of the three types of intentions. Additionally, experiences of cyberbullying, particularly as a cyberbully, and gender were linked to pro-bully intentions. Post hoc gender analyses revealed that friends, family, and teachers’ norms were particularly relevant for reducing pro-bully intentions in girls. Conclusions: These findings suggest that TPB is a useful framework for understanding the intentions of defender, passive, and pro-bully cyberbystanders. Future research should include both non-witnesses and witnesses to better compare intention versus actual behavior and investigate temporal and causal pathways within the TPB model.

Keywords

Cyberbystanders, Theory of planned behavior, Empathy, IntentionCite this article as: Quintana-Orts, C., Alcántara-Lázaro, A., Mora-Merchán, J. A., & Del Rey, R. (2026). Defender, Passive, and Pro-Bully: Exploring Bystanders’ Intentions toward Cyberbullying. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260811. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a3

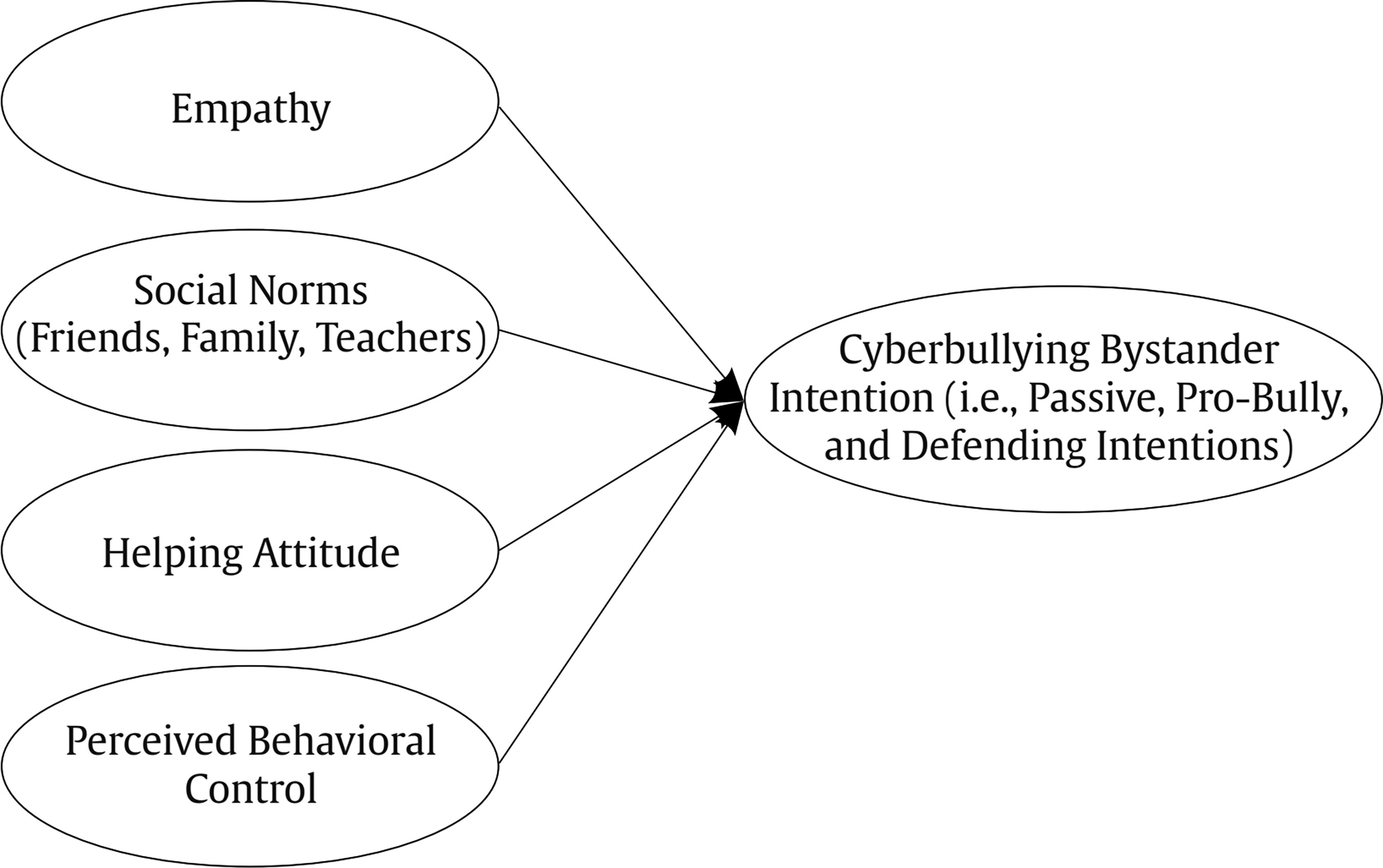

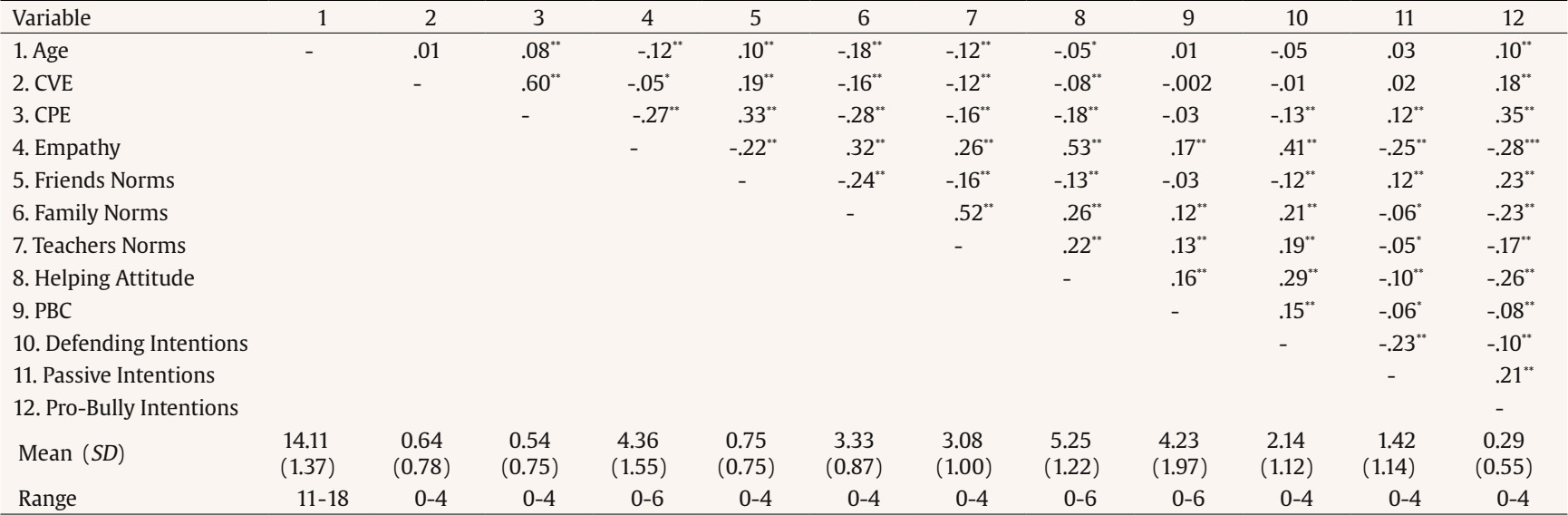

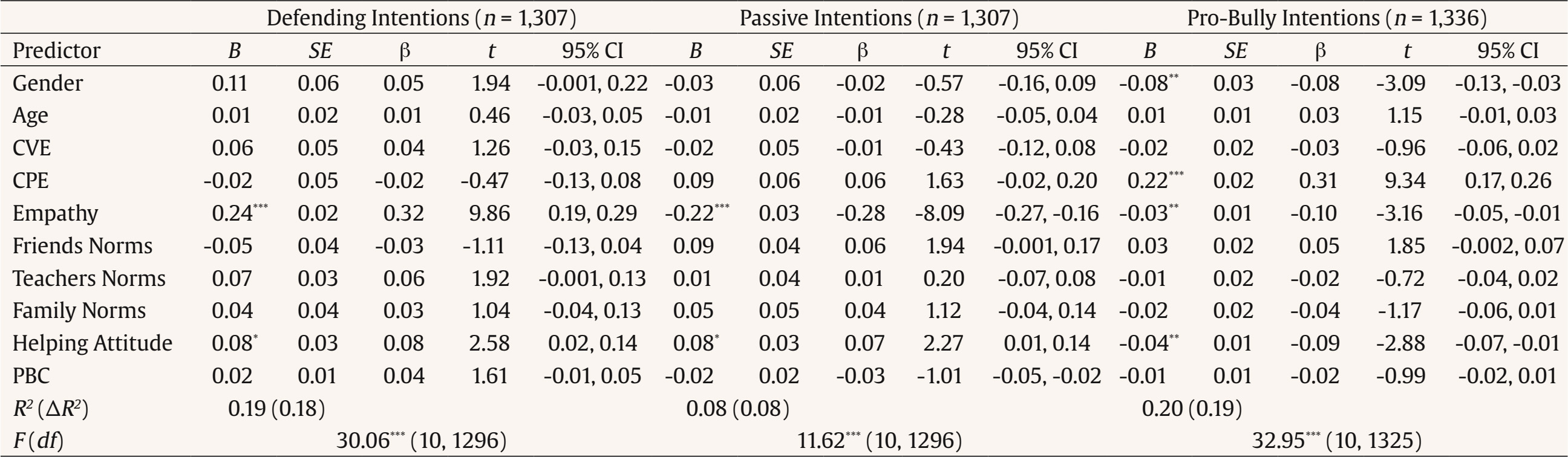

Correspondence: cquintana@uma.es (C. Quintana-Orts).With the rapid advancement of the Internet and Social Networks, an increasing number of people, especially adolescents and youth, are using the Internet for work, study, entertainment, and other activities (Anderson et al., 2023). Unfortunately, social networks have also become a significant setting for the high incidence of cyberbullying (Hayes et al., 2022). Cyberbullying is defined as “an aggressive, intentional act carried out by a group or individual, using electronic forms of contact, repeatedly and over time against a victim who cannot easily defend him or herself” (Smith et al., 2008, p. 376). As a result, cyberbullying has been associated with more negative consequences than traditional forms of bullying (Huang et al., 2023; Kazerooni et al., 2018). Although the exact prevalence of cyberbullying is difficult to determine, estimates suggest that up to 57.5% of internet and social network users have been victims of cyberbullying (Sorrentino et al., 2023). Additionally, Vogels (2022), based on a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2022, indicated that 73% of adolescents between 13 and 17 stated they had witnessed these situations. Given that bystanders represent the largest group involved in the phenomenon, they are in a unique position to detect and intervene in the progression of cyberbullying incidents (Wang, 2021; Zhao et al., 2023). Through their active response or passivity, they can alter the dynamics of cyberbullying episodes (Huang et al., 2023; Jeyagobi et al., 2022). Specifically, bystanders can change the course of events by defending the victim (i.e., hereinafter, referred to as ‘defender’ responses; e.g., supporting them, reporting the incident, or telling the aggressor to stop), reinforcing the bully (i.e., pro-bully response; e.g., spreading the incident or liking the bully’s comments), or adopting a passive stance (i.e., passive response; e.g., watching without intervening) (Dang & Liu, 2022; Machackova et al., 2018). To date, most studies have focused on examining what motivates bystanders to engage in behaviors aimed at helping the victim (DeSmet et al., 2016; Hayashi & Tahmasbi, 2022). Previous studies have provided valuable insights into the aspects that encourage defending reactions to cyberbullying: (a) personal factors such as gender — with girls more willing to help (Wang & Kim, 2021) — , age — with younger adolescents displaying higher rates of helping behaviors (Van Cleemput et al., 2014) — , unpleasant emotions towards aggression (Ferreira et al., 2022), higher self-efficacy (Clark & Bussey, 2020), higher empathy (Huang et al., 2023), lower moral disengagement (Bussey et al., 2020), and prior experience as victims or perpetrators of cyberbullying (Shen et al., 2023; Wang & Kim, 2021); (b) situational factors such as a bad relationship with aggressors and a lower number of other bystanders (Song & Oh, 2018); and (c) contextual factors such as perceived social support (Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2017) or social norms (Bastiaensens et al., 2016). However, it is equally important to address what drives bystanders to choose behaviors that may exacerbate a cyberbullying situation (Barliska et al., 2015; Bastiaensens et al., 2016; Jeyagobi et al., 2022), including the absence of response, which is often considered as a form of silent approval of the aggression (Leung, 2021; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). This gap underscores the need for a deeper understanding of the range of bystander responses in cyberbullying and related factors, whether they involve support or non-intervention. Furthermore, few studies have employed a rigorous theoretical model to explore what influences these reactions and how to effectively mobilize bystanders to intervene positively (Doane et al., 2016; Doane et al., 2020). Cyberbystanders and Theory of Planned Behavior Among the existing explanatory theories, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1991, 2012) shows promising potential for this purpose (DeSmet et al., 2016; Hayashi & Tahmasbi, 2022). According to this theory (Ajzen, 1991, 2012), behavior is determined by the intention to perform it, which is directly influenced by the individual’s belief system, comprising attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Attitudes refer to how positively or negatively behavior is evaluated. Subjective norms, also known as social norms, refer to the perception of what significant others believe one should do (Ajzen, 2020). Perceived behavioral control refers to the perception of how easy or difficult it is to perform the behavior. Prior studies conducted within the framework of the TPB suggest that perceived social norms regarding participation in or avoidance of cyberbullying, positive or negative attitudes toward such aggression, and perceived behavioral control can predict individuals’ intentions to act and their actual behavior in cyberbullying situations. For example, Pabian et al. (2016) found that individuals with a positive attitude toward cyberbullying were less likely to defend victims. DeSmet et al. (2016) indicated that attitudes toward negative bystander behavior (e.g., laughing at victims or observing without intervening) and perceived behavioral control (e.g., perceived self-efficacy) to intervene in cyberbullying episodes were significant predictors of the intention to help victims. In contrast, attitudes toward positive bystander behavior (e.g., defending the victim) were not found to be significant predictors. More recently, Leung (2021) observed that negative attitudes toward cyberbullying, social approval of helping behavior, and perceived self-efficacy positively influenced the intention to intervene on behalf of the victim, which in turn predicted helping behavior. On the other hand, the more favorable the social norms toward cyberbullying, the less likely the bystanders to defend the victim and the more inclined to reinforce the aggressor (Dang & Liu, 2022). Similarly, when inaction is perceived as the predominant social norm, bystanders are more likely to conform to it to ensure their behavior aligns with group expectations (You & Lee, 2019). Despite the growing empirical support for the usefulness of the TPB in explaining cyberbystander behavior, research on the factors associated with different types of cyberbystanders during adolescence remains limited. Most studies focus primarily on a single response, specifically defending reactions (e.g., DeSmet et al., 2016; Leung, 2021). This study addresses this gap by examining three distinct cyberbystander intentions: defending, pro-bully, and passive. By adopting a more holistic approach, this research aims to identify influential variables across these responses, providing a foundation for comprehensive intervention strategies based on a robust theoretical framework. This research places particular emphasis on the role of intentions, which, as posited by the TPB, are the most proximal antecedent of actual behavior. Moreover, it focuses exclusively on adolescents who reported not having witnessed cyberbullying incidents. Studying this “pre-exposure” group enables examination of how TPB components operate before direct bystander experience, offering a clearer view of dispositional factors that shape adolescents’ intended responses and informing early, preventive educational efforts. Previous studies have shown that including additional variables enhances the model’s explanatory power (e.g., Hayashi & Tahmasbi, 2022). In the present study, we investigate an additional variable, empathy, alongside the TPB standard variables to understand its relationship with the three types of cyberbullying bystander responses. This improvement of the model is in line with Ajzen’s ideas, who points out (Ajzen, 2020) that TPB allows the inclusion of other predictor variables as long as they provide significant contributions beyond the three standard components. Empathy has long been recognized as a key driver of prosocial behavior. According to the empathy-altruism hypothesis (Batson et al., 1995; Batson et al., 2015), empathic concern — an other-oriented emotional response congruent with the perceived welfare of someone in need — can evoke truly altruistic motivation, aiming to benefit the person for whom empathy is felt, rather than oneself. This perspective suggests that, in the context of cyberbullying, the empathic concern experienced by bystanders when observing online aggression may increase their willingness to help the victim. In line with this view, studies indicate that individuals with high levels of empathy, who can understand the victims’ feelings, are more likely to defend them when witnessing aggression (Batanova et al., 2014; Song & Oh, 2018). In contrast, those with low levels of empathy tend to reinforce or join the aggressor or refrain from intervening (Barliska et al., 2015; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). Within the framework of the TPB, Hayashi and Tahmasbi (2022) incorporated empathy to enhance the model’s explanatory power. Their findings, consistent with previous research (Barliska et al., 2018; Doane et al., 2020; Van Cleemput et al., 2014), demonstrated that empathy is a significant predictor of helping behavior, standing out even above perceived behavioral control, which is commonly identified as a key predictor of helping intentions and behavior (Desmet et al., 2016; Leung, 2021; Leung & Chiu, 2023; Machackova et al., 2018). These results suggest that empathy adds an essential emotional dimension that is not accounted for in the standard components of the theory, thereby enhancing the TPB model’s explanatory power in predicting bystanders’ specific responses in cyberbullying situations. Present Study’s Aims Despite previous research demonstrating how the standard components of the TPB interact to predict bystanders’ defending responses to cyberbullying, evidence remains limited, particularly regarding pro-bully and passive intentions. The present study addresses some of the knowledge gaps through the following aims: 1) Unlike prior studies, such as DeSmet et al. (2016) and Hayashi and Tahmasbi (2022), which focused on helping behaviors toward victims, the present study aims to examine the TPB model in relation to three distinct cyberbystander intentions in a sample of adolescents: defending, pro-bully, and passive. To do so, the present study included three social norms (family, friends, and teachers), attitude toward helping cyberbullying victims, and perceived behavioral control. Control variables such as gender, age, cyberbullying victimization, and perpetration experiences were considered due to their influence (e.g., Van Cleemput et al., 2014; Wang & Kim, 2021). Additionally, a supplementary variable widely recognized as a key factor influencing bystander behavior and predicting responses to aggression—empathy (e.g., Hayashi & Tahmasbi, 2022; Song & Oh, 2018) — is incorporated. 2) To provide a clearer understanding of the components of the TPB underlying cyberbystanders’ intentions, this study focused on adolescents who reported not having witnessed cyberbullying incidents. Focusing on non-witnesses creates a “pre-exposure” context in which intentions are not influenced by prior witnessing, thus offering a more controlled examination of dispositional predictors and enhancing the usefulness of findings for early preventive interventions. Figure 1 Theory of Planned Behavior Model for Non-Witnesses of Cyberbullying.   Note. Control variables are excluded from the figure for clarity. Participants A total of 2,539 students from eighteen schools in Seville, Cordoba, and Huelva (Spain) participated in this study, recruited through convenience sampling. Participants included 1,243 boys (49.1%), 1,245 girls (49.2%), and 43 (1.7%) who indicated different gender identities; eight individuals did not report their gender. Ages ranged from 11 to 18 years (M =14.07, SD =1.39). Students were enrolled in the four academic years of Compulsory Secondary Education in Spain (equivalent to Grades 7 to 10 in the U.S. system): 1st year (n = 663, 26.1%), 2nd year (n = 674, 26.5%), 3rd year (n = 620, 24.4%), 4th year (n = 486, 19.1%), and the 1st year of Upper Secondary Education (equivalent to Grade 11 or the first year of High School; n = 96, 3.8%). According to the study aims, 497 participants (21.4%) who reported witnessing cyberbullying incidents were excluded from the analysis; therefore, the final sample consisted of 1,825 participants (78.6%) who reported not having observed any such situations. Instruments The items of the questionnaires used in the present study can be found in the Appendix. Cyberbullying Bystander Intentions Bystanders’ responses to cyberbullying were measured using the Spanish adaptation of the Student Bystander Behaviour Scale (SBBS; Thornberg & Jungert, 2013) from Álvarez-García et al. (2021). This 10-item self-report scale, originally based on bullying, was further adapted for the context of cyberbullying to match our purpose. The measure began with a brief definition of cyberbullying, followed by a screening question: “Now think about the current school year. Have you witnessed a situation of cyberbullying?” (response options: Yes/No). Based on this response, adolescents were classified as witnesses or non-witnesses (0 = No, 1 = Yes). Only those who reported not having witnessed cyberbullying were included in the present analyses. These participants were then presented with the prompt “And if not, how do you think you would react?”, which assessed behavioral intentions in hypothetical cyberbullying scenarios. The scale distinguishes between three types of bystander responses — defending the victim, supporting the aggressor, and remaining passive — assessed as behavioral intentions. Specifically, four items (2, 3, 4, and 6) assess the Defender intentions (e.g., “I contacted people I know to try to stop what is happening”). Three items (5, 9, and 10) assess pro-bully intentions (e.g., “I laughed and intervened in the message or comment thread to cheer the aggressor to keep doing it”). Three items (1, 7, and 8) assess passive intentions (e.g., “Nothing. I go on doing whatever I was doing because what’s happening has nothing to do with me”). Items were ranked by frequency on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always). Internal consistency reliability for the current sample was α = .81 for the defender subscale, α = .69 for the pro-bully subscale, and α = .72 for the passive subscale. Standard TPB Variables The attitude toward helping cyberbullying victims (i.e., helping attitude) was assessed with four semantic differential items (e.g., “For me, helping someone bullied online is” 0 = bad, 6 = good). The items were adopted from Hayashi and Tahmasbi (2022). Internal consistency reliability for the current sample was α = .91. Subjective norms of friends, family, and teachers were each assessed using five items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). For friends’ subjective norms, the first four items (e.g., ‘‘Most of my friends think it is OK to upload an offensive video”) were adopted from the Peers’ Subjective Norms Regarding Online Risk Behaviors Scale (Sasson & Mesch, 2016). The last item assessed the injunctive norm of friends approving of cyberbullying (e.g., “Most of my friends think it is OK to bully someone through the Internet or mobile phone”) and was adopted from Bastiaensens et al. (2016). For family and teachers’ subjective norms, the first four items were adopted from the Parents’ Subjective Norms regarding Online Risk Behaviors Scale (Sasson & Mesch, 2016), with adjustments to differentiate the level of imperativeness between the two groups (e.g., “My family forbids me…/ My teachers advise me… not to upload offensive posts to the networks”). The last item for each scale assessed the injunctive norm of family and teachers approving of cyberbullying (e.g., “My family would not approve of me acting violently online”; “My teachers think it’s not OK to act violently online”), respectively. Both items were adopted from Bastiaensens et al. (2016). Internal consistency reliability for the current sample was α = .75 for friends’ subjective norms, α = .82 for family subjective norms, and α = .83 for teachers’ subjective norms. Perceived behavioral control of helping cyberbullying victims was assessed using a single item (e.g., “If someone is bullied online, I consider that it is up to me to help or not to help”), rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The item was adapted for the present study based on the scale from Hayashi and Tahmasbi (2022). Additional Variable Empathy toward cyberbullying victims was assessed with a 5-item scale from Hayashi and Tahmasbi (2022), reflecting both empathic concern (e.g., “I feel very sorry for those who suffer online violence”) and personal distress (e.g., “Sometimes, I get distressed when I read or hear about some online violence situation”). Each item (e.g., “It often makes me distressed when I see someone bullied online”) was rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Internal consistency reliability for the current sample was α = .92. Control Variables This study includes different ages, gender, and cyberbullying victimization and perpetration experiences as covariates. Both experiences were assessed using the Brief Version of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (Álvarez-Marín et al., 2022). Students reported on their experiences on the internet and social media of cyberbullying victimization (3 items; e.g., “Someone has said bad words about me”) and cyberbullying perpetration (3 items; e.g., “I have said bad words about someone”) over the past two months, rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (never) to 4 (more than once a week). The internal consistency for this sample was α = .75 for cyberbullying victimization, and α = .72 for cyberbullying perpetration. Procedure Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the authors’ institution. Permission to collect data was requested from the management of the eighteen participating schools, who then notified parents and solicited their consent. Upon obtaining the required permissions, data were gathered using convenience sampling. Before being enrolled in the study, all participants were informed about the research aims, the voluntary nature of their participation, the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses, and the importance of answering sincerely. Only those who provided informed consent were included. Participants were instructed to complete a paper-and-pencil self-report survey that included demographic questions (e.g., age, gender, school, grade, and social networking sites used, among others) and scales assessing online activities, bystander responses, attitudes toward help cyberbullying victims, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and empathy. The survey was administered in the classroom during school hours on different days across various classes, conducted by the authors and trained researchers who were available to answer students’ possible questions about the survey. A total of 2,520 participants completed the paper-and-pencil survey, with an average completion time of 45-50 minutes. An online version of the survey was also available on SurveyMonkey, following the same structure and sequence as the paper-and-pencil survey. After clicking the “agree to participate” button as a part of the informed consent, 19 participants completed the online version, with a similar average completion time. Data Analysis All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS package (version 26.0; IBM, United States). First, descriptive statistics were carried out to evaluate the scores obtained for each measurement and the association between the variables of interest was analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Second, the regression method was utilized to perform multiple linear regression analysis. This approach was beneficial for understanding and explaining cyberbullying bystanders intentions within the theoretical framework of the TPB. Before conducting the main analyses, assumptions that need to be met for interpreting all estimates were tested and no important violation was observed. Age, gender, and cyberbullying victimization and perpetration experiences were used as covariables (see Figure 1, TPB Model). For defending, pro-bully and passive intentions, the TPB variables (friends-, family's-, and teachers' norms, and perceived behavioral control) and empathy were entered into the regression models. Pearson Correlations All TPB variables were significantly correlated with the three forms of cyberbullying bystander’s intentions (Table 1). More specifically, all TPB variables were negatively and significantly correlated with passive and pro-bully intentions, except for friends’ norms, which were positively correlated. The opposite pattern was found for defending intention. Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlation of Control Variables, TPB Variables and Cyberbullying Bystander Intentions   Note. N = between 1,520 and 1,825; SD = standard deviation; CVE = cyberbullying victimization experience; CPE = cyberbullying perpetration experience; PBC = perceived behavioral control. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Regression Analyses of Intentions for Non-Witnesses In line with the aims of the present study, standard multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess the roles of the TPB variables (friends’ norms, family norms, teachers’ norms, and perceived behavioral control) and empathy in predicting defending, pro-bully, and passive intentions among non-witnesses. Age, gender, and cyberbullying victimization and perpetration experiences were used as covariates in all models. Results of these analyses are presented in Table 2. Table 2 Regression Models using the SBBS as Intentions for Non-Witnesses   Note. Results correspond to multiple regression analyses including all predictors; gender was coded as 0 = boys, 1 = girls. B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; β = standardized coefficient; CI = confidence interval; CVE = cyberbullying victimization experience; CPE = cyberbullying perpetration experience; PBC = perceived behavioral control. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Table 2 summarizes the regression models identifying the factors associated with the three types of cyberbystander intentions among non-witnesses: defending, pro-bully, and passive. All models were statistically significant (p < .05 or p < .001), although they explained a limited proportion of variance, ranging from 8% to 20%. Notably, R-squared values were higher for defending (R2 = .19) and pro-bully intentions (R2 = .20), whereas the model for passive intentions showed lower explained variance (R2 = .08). Cyberbullying Bystander Intentions Models Regarding defending intentions, the regression model was significant (R2 = .19, F(10, 1296) = 30.06, p < .001). Among the predictors, empathy emerged as the strongest and most consistent predictor (B = 0.24, p < .001), followed by helping attitude (B = 0.08, p < .05). The regression model predicting passive intentions was also significant (R2 = .08, F(10, 1296) = 11.62, p < .001). Empathy emerged again as the strongest predictor (B = -0.22, p < .001), followed by helping attitude (B = 0.08, p < .05). Finally, the model predicting pro-bully intentions reached statistical significance (R2 = .20, F(10, 1325) = 32.95, p < .001). In this case, prior experience as a cyberbully was the most robust predictor (B = 0.22, p < .001), followed by gender (B = -0.08, p < .01), a less favorable helping attitude (B = -0.04, p < .01), and lower empathy (B = -0.03, p < .01). Given the gender differences observed in pro-bully intentions, post hoc regression analyses were conducted separately for boys and girls. Although significant for both boys (R2 = .18, F(9, 618) = 14.65, p < .001) and girls (R2 = .20, F(9,683) = 18.73, p < .001), showed distinct patterns. For boys, prior experience as a cyberbully (B = 0.25, p < .001) and helping attitude (B = -0.04, p < .05) significantly predicted pro-bully intentions. For girls, in addition to cyberperpetration experiences (B = 0.17, p < .001) and helping attitude (B = -0.04, p < .05), significant predictors included peer norms (B = 0.09, p < .001), family norms (B = -0.06, p < .01), teacher norms (B = 0.04, p < .05), and empathy (B = -0.03, p < .01). The main goal of this research was to evaluate whether the TPB can contribute to understanding the three cyberbystanders intentions (defending, pro-bully, and passive) of adolescents. To do so, a non-witness sample of cyberbullying episodes was considered to evaluate intentions. The results suggest that TPB, including empathy, is a useful framework to help explain the intentions of non-witnesses. However, there are distinct similarities and differences in the factors associated with each type of cyberbystanders’ intentions. The two factors that appear to be common in the three intentions are empathy and helping attitude. Moreover, the present study revealed that empathy was a more robust predictor of defending and passive (inversely) intentions than attitudes and perceived behavioral control. These results are consistent with existing research suggesting people with empathy are more likely to be defenders (Batanova et al., 2014; Doane et al., 2020; Song & Oh, 2018), and less likely to be passive or pro-bully bystanders in cyberbullying incidents (Shen et al., 2023). In contrast to DeSmet et al. (2016), who found that attitudes toward negative bystander behaviors (e.g., laughing at victims or passivity) significantly predicted intentions to help victims, while attitudes toward positive bystander behaviors did not, our findings highlight a consistent effect of helping attitude across all three response types. Interestingly, this attitude was negatively associated with pro-bully intentions but positively linked with both defending and passive intentions. This pattern is in line with the previous study by Obermann (2011) who found a group of bystanders named “guilty bystanders", who do nothing but think they ought to help the person being bullied. Thus, although adolescents may view helping as valuable, appropriate, and morally correct, other factors might influence their intention to remain passive in cyberbullying situations. For instance, prior research highlights the role of self-efficacy beliefs in bystander intervention, which relates to perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 2020), where lower confidence in the ability to help effectively is linked to passive responses (e.g., DeSmet et al. 2016; Sjögren, Thornberg, et al., 2024). It is also plausible that even with a positive helping attitude, adolescents might view cyberbullying situations as risky or socially complex and might rationalize inaction as less harmful or even necessary to avoid escalating the situation, due to reasons such as the extent to which adolescents believe that they are capable of performing the defending behavior or the fear of being bullied themselves (Sjögren, Thornberg, et al., 2024; Van Cleemput et al., 2014). However, the positive relationship between helping attitude and passive cyberbystander intentions, along with the potential variables underlying this connection such as perceived behavioral control, warrants further investigation. Finally, the results suggest that pro-bully intentions were associated with being a boy and cyberbullying perpetration experience, alongside lower empathy and helping attitude. Previous studies have shown that boys are more likely to reinforce the aggressor, while girls tend to help the victim (Bastiaensens et al., 2014). This may be related to boys’ lower perception of the severity of cyberbullying than girls (Bastiaensens et al., 2014) and to gender differences in socialization. More specifically, post hoc analyses revealed notable gender differences in the number and type of factors associated with pro-bully intentions. Prior experience as a cyberbully was the most strongly predictor of higher pro-bully intentions for both boys and girls. This aligns with research showing that students involved in cyberbullying are more likely to act as pro-bully bystanders (Shen et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023). It is plausible that adolescents with experiences as cyberbullies, regardless of gender, may develop positive attitudes towards cyberbullying, such as justifications for the behavior or blaming victims, and that this attitude is likely to be reflected in their intention as cyberbystanders as well (Zhao et al., 2023). Although cyberbullying perpetration and helping attitude were the common significant predictors of pro-bully intentions among both genders, a broader set of factors emerged for girls. Specifically, girls’ pro-bully intentions were associated not only with prior cyberbullying experience, but also with stronger peer and teacher norms, weaker family norms, and lower empathy. In other words, girls were more likely to report pro-bully intentions when they perceived that their peers and family members found it acceptable to post offensive content or act aggressively online, and when teachers communicated norms related to online behavior, such as advising against uploading harmful content or meeting strangers from the internet. These results suggest that girls may be more sensitive to social and relational influences. On the one hand, prior research has shown that girls tend to be more relationship-oriented and more susceptible to peer pressure, which may increase their likelihood of conforming to socially normative behavior, even in online contexts (Lambe et al., 2019; Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Additionally, girls have been found to be more influenced by peers’ and parents’ opinions in other behavioral domains, such as alcohol use (Kyrrestad et al., 2020) and prosocial behavior (Farrell et al., 2017), a pattern that may extend to their behavior as cyberbystanders. On the other hand, and somewhat unexpectedly, teacher norms were positively associated with pro-bully intentions among girls. While supportive teachers are typically expected to discourage cyberbullying, it is possible that their messages are sometimes perceived as ambiguous. Another potential explanation may be related to how adolescents interpret adult reasoning. Although supportive teachers often listen to and show genuine interest in helping their students, they may inadvertently promote maladaptive behaviors (Quintana-Orts et al., 2024). Thus, girls, who tend to be more attuned to teacher influence, might misinterpret certain messages, inadvertently reinforcing pro-bullying intentions. Thus, these findings highlight the need to examine more closely how teacher-student dynamics shape bystander behavior, especially among girls. Limitations While this study provides new insights into cyberbystander intentions, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, although the sample size was relatively large, it was drawn from a single region in Spain, limiting the generalizability of the findings to adolescents in other contexts and restricting our analysis to a more descriptive level. Additionally, only 21.4% of participants reported witnessing a cyberbullying incident — a rate notably lower than the global prevalence (e.g., 73%; Pew Research Center survey, 2022). This discrepancy could be attributed to differences in measurement approaches. Research has shown that prevalence rates tend to be higher when participants are asked about specific behaviors rather than general questions about the phenomenon (e.g., Sjögren, Bjereld, et al., 2024). This pattern is not unique to cyberbullying but occurs across various phenomena, as individuals may not label certain experiences as part of a broader category due to the normalization of specific behaviors. Incorporating specific behavioral indicators in surveys may therefore yield more accurate prevalence estimates of cyberbullying bystanders. Second, as this study is part of a larger project, to keep the study at a reasonable length for participants, some measures were based on single items or shortened versions. While this limitation may have contributed to the low R2 values observed, particularly for passive intentions and behaviors, the overall findings remain consistent with previous literature (e.g., DeSmet et al., 2016; Hayashi & Tahmasbi, 2022). Third, this study focused exclusively on non-witnesses to examine hypothetical behavioral intentions in a pre-exposure context. While this approach allows for a clearer analysis of dispositional TPB variables unconfounded by previous bystander experiences, it does not capture how these intentions translate into real behaviors. Future studies should include both witnesses and non-witnesses to compare how TPB components operate before and after exposure to cyberbullying incidents. Finally, given the cross-sectional nature of our data, the capacity to infer causal relationships is limited. Although the TPB provides a theoretical basis for directionality, only longitudinal designs (e.g., measuring intentions at Time 1 and behaviors at Time 2) can confirm causal pathways. Future research should also employ behavior-specific TPB measures that ensure alignment among attitudes, norms, perceived control, and the targeted bystander responses (Ajzen, 2020). Moreover, integrating other personal (e.g. victim blaming, emotions like fear, moral disengagement, etc.), situational (e.g., the bystander’s relationship with the victims or aggressors), and contextual (e.g., parental supervision) variables could enhance understanding of how adolescents decide whether to defend, remain passive, or support the bully. Also, the impact of empathy, as well as its dimensions, should be considered in further research due to the importance and complexity of this factor in online contexts (e.g., Barliska et al., 2018). Despite its limitations, this study represents, to our knowledge, the first attempt to apply the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explain three types of cyberbystander intentions (i.e., defending, passive, and pro-bully) in a non-witness sample. These findings broaden the understanding of cyberbystander responses by considering different roles simultaneously (DeSmet et al., 2016; Hayashi & Tahmasbi, 2022). Also, these results demonstrate the importance of focusing efforts not only on TPB factors related to defending responses, but also on understanding their role in passive and pro-bully intentions when designing prevention and intervention programs. Although future studies using more refined measures and sophisticated analytical strategies are warranted, the present findings suggest several practical implications that could inform prevention and intervention efforts in educational settings. First, the consistent role of empathy and helping attitudes across all bystander roles highlights the need to promote these variables as central intervention targets. Programs aimed at increasing defending intentions and reducing passive or pro-bully behaviors may benefit from structured activities that foster emotional literacy and perspective-taking, such as guided discussions of real-life cases, role-play exercises, pedagogical theatre-based activities, or reflection-based exercises that explore the emotional impact of cyberbullying. These activities could be particularly useful for students who display lower levels of empathy and could also help them translate intention into action. Second, our results emphasize the role of subjective norms in shaping pro-bully intentions, particularly among girls. The perception that peers and family members tolerate or even endorse cyberbullying was associated with greater willingness to support the aggressor. This finding suggests the need for interventions that explicitly address and reshape social norms through peer-led monitoring, classroom discussions on digital citizenship, and parent-focused workshops that communicate the seriousness and long-term consequences of cyberbullying. It is essential to engage families in conveying consistent, non-tolerant messages about online aggression, reinforcing that it is not a harmless or inevitable part of adolescence. A particularly surprising and novel result emerged regarding teacher norms. Specifically, among girls, the perception of teacher disapproval of cyberbullying was paradoxically associated with higher pro-bully intentions. While this finding requires further investigation, it raises important questions about how adolescents interpret adult messages. Therefore, teacher training programs should not only emphasize anti-bullying policies but also promote value-based communication and moral reasoning so they can encourage students to recognize the harm of minimizing or justifying cyberbullying. Finally, at the institutional level, it is essential that schools adopt and communicate clear anti-cyberbullying protocols supported by both staff and students. Integrating anti-(cyber)bullying content into the curriculum and promoting a shared sense of responsibility can foster an environment where defending behaviors are encouraged, expected, and socially rewarded. Overall, these findings underscore the need for multilevel, developmentally appropriate interventions that take into account not only individual and attitudinal factors but also the broader social context in which adolescents make decisions about how to respond to cyberbullying. Undoubtedly, further research is needed to better understand how and why these TPB standard factors are influencing and interacting with other relevant personal, situational, and contextual factors in shaping cyberbystanders intentions. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Quintana-Orts, C., Alcántara-Lázaro, A., Mora-Merchán, J. A., Del Rey, R. (2026). Defender, passive, and pro-bully: Exploring bystanders’ intentions toward cyberbullying. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260811. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a3 Funding This study was supported by the Grant PID2020-115913GBI00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the funding for the predoctoral contract FPI (PRE2019-091184) to A.A.-L. Also, this work was supported by the Juan de la Cierva-Formación postdoctoral fellowship program to C.Q.-O. from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities under Grant. Appendix Supplementary Material Questionnaires Used in the Present Study Cyberbullying Experience (never, once or twice, once or twice a month, about once a week, more than once a week) In the last two months, how often have you experienced the following on the Internet and social networks?

Cyberbullying Bystander Responses Now think about the current school year. Have you witnessed a situation of cyberbullying? Yes/No "If so, how did you react? And if not, how do you think you would react?" (0 = never, 4 = always)

Intention to Help (0 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree)

Subjective Norms of Friends (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) My friends…

Subjective Norms of Teachers (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) My teachers…

Subjective Norms of Family (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) My family…

Perceived Behavioral Control (0 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) If someone is suffering online violence, I consider that...

Empathy (0 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree)

| IntroductionMethodResultsDiscussionImplications and ConclusionsQuestionnaires Used in the Present StudyCyberbullying Bystander ResponsesHelping Attitude Intention to Help (0 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) Subjective Norms of Friends (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) Subjective Norms of Teachers (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) Subjective Norms of Family (0 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree) Perceived Behavioral Control (0 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) Empathy (0 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree) |

Cite this article as: Quintana-Orts, C., Alcántara-Lázaro, A., Mora-Merchán, J. A., & Del Rey, R. (2026). Defender, Passive, and Pro-Bully: Exploring Bystanders’ Intentions toward Cyberbullying. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260811. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a3

Correspondence: cquintana@uma.es (C. Quintana-Orts).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS