A Community Intervention to Increase Positive Parenting: A Three-Year Cohort Study in South Africa

Catherine L. Ward1, Marilyn T. Lake1, Lisa M. Kleyn1, 2, Diketso Mufamadi-Mathebula1, 3, Warren Parker4, Simone Peters1, Wilmi Dippenaar5, & Chandré Gould3

1University of Cape Town, South Africa; 2Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, United Kingdom; 3Institute for Security Studies, South Africa; 4Centre for Communication Media and Society, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa; 5Seven Passes Initiative, Touwsranten, South Africa, and South African Parenting Programme Implementers Network, South Africa

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a2

Received 3 April 2025, Accepted 27 October 2025

Abstract

Objective: We evaluated an intervention to increase positive parenting, reduce corporal punishment, and improve children’s mental health community-wide. All Parenting for Lifelong Health programmes were available to all interested parents alongside an action media intervention designed to amplify positive parenting messages across the community. Method: Three community-wide surveys of parents and of children aged 10+ were conducted at baseline and at 18-month intervals. Parent and child surveys assessed parenting and corporal punishment; parent surveys also addressed intimate partner violence (IPV), parent and child mental health, parent alcohol misuse, and parenting stress. Results: 536 parent-child dyads were included in the surveys; 110 (20.5%) parents attended a parenting programme at least once. Positive parenting did not increase across the whole community; there was a trend towards reduction of corporal punishment. Parenting stress declined and children’s mental health improved by the third survey, possibly through increased parent employment rather than the intervention. IPV, parent mental health, and parent alcohol misuse were unchanged, and were associated with less positive parenting and more children’s mental health symptoms. The action media process may indeed have enabled diffusion of parenting information, but also appeared to be associated with small negative effects on positive parenting, parenting stress and children’s internalising and externalising. Conclusions: Reduction in parenting stress, a trend towards a reduction in corporal punishment, and improvement in children’s mental health, were observed by year three. Parents’ mental health, substance abuse and IPV must be addressed alongside parenting interventions to improve both parenting and children’s mental health.

Keywords

Parenting, Corporal punishment, Prevention, Intervention, CommunityCite this article as: Ward, C. L., Lake, M. T., Kleyn, L. M., Mufamadi-Mathebula, D., Parker, W., Peters, S., Dippenaar, W., & Gould, C. (2026). A Community Intervention to Increase Positive Parenting: A Three-Year Cohort Study in South Africa. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260810. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a2

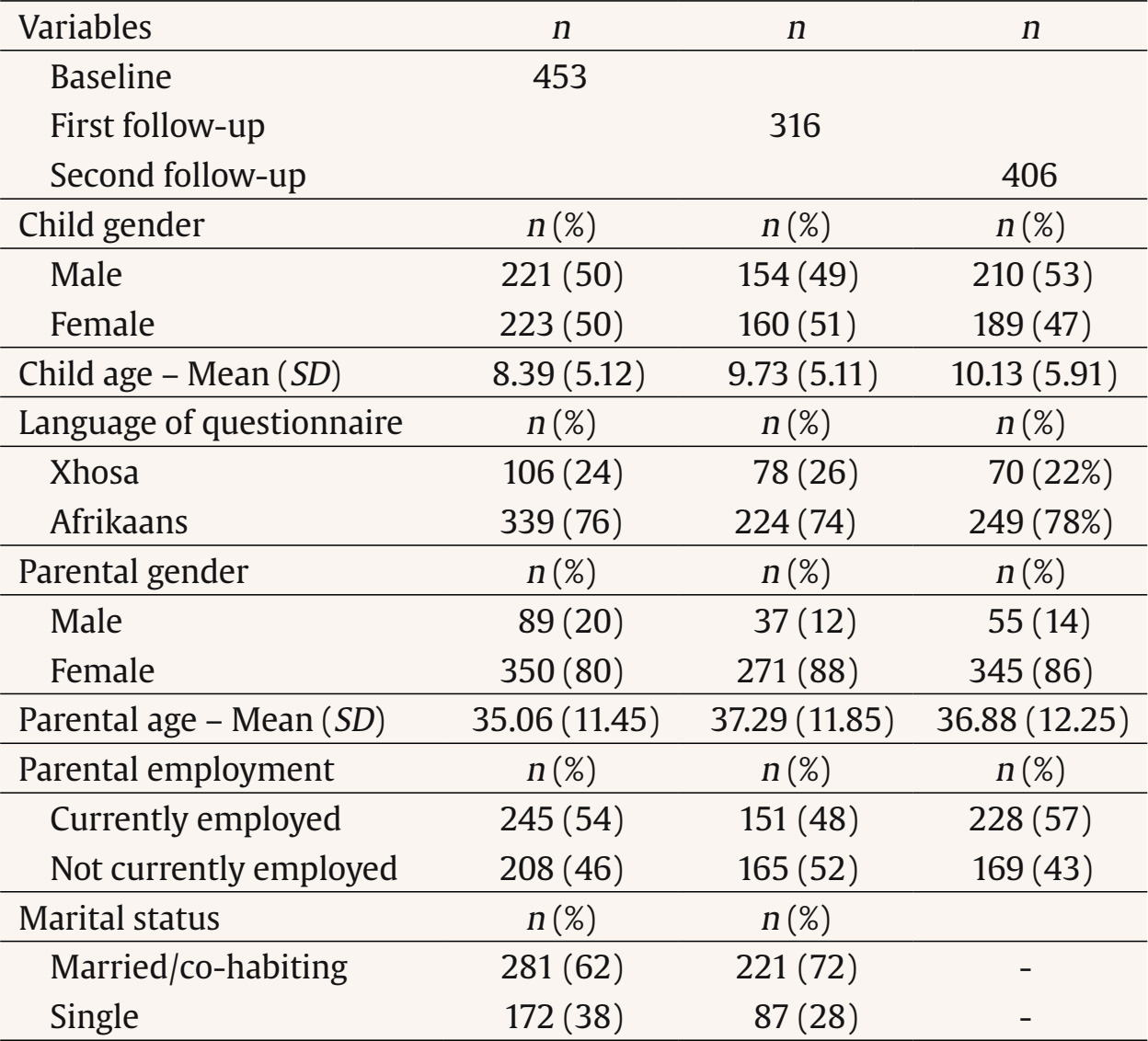

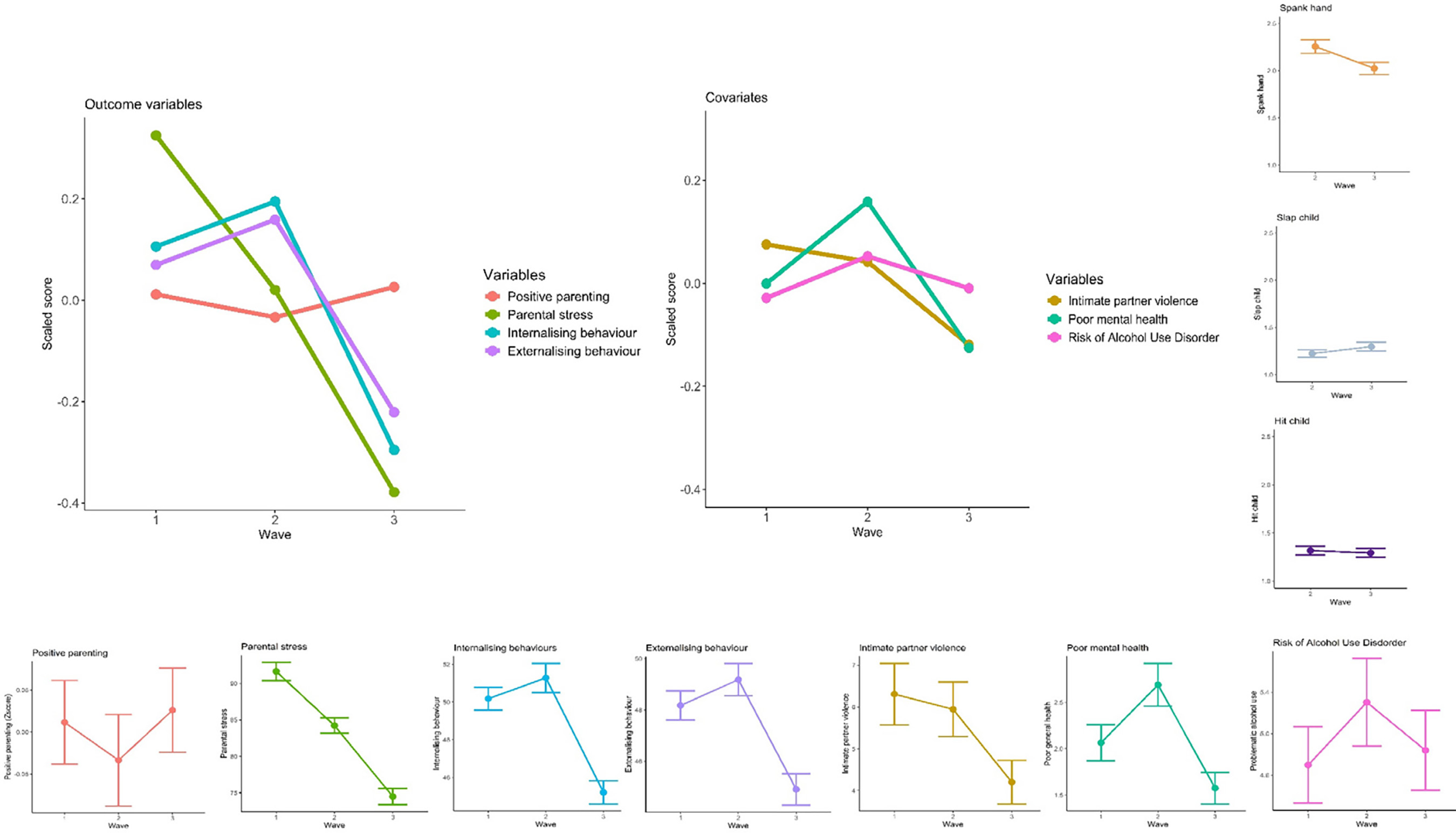

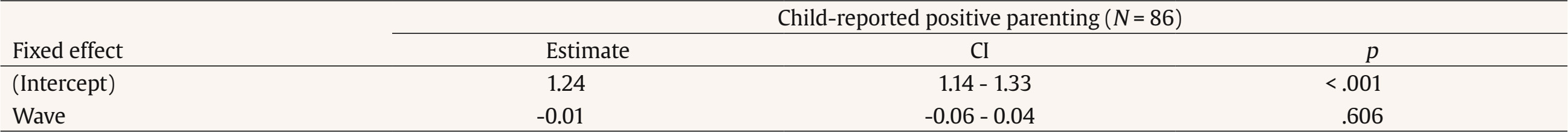

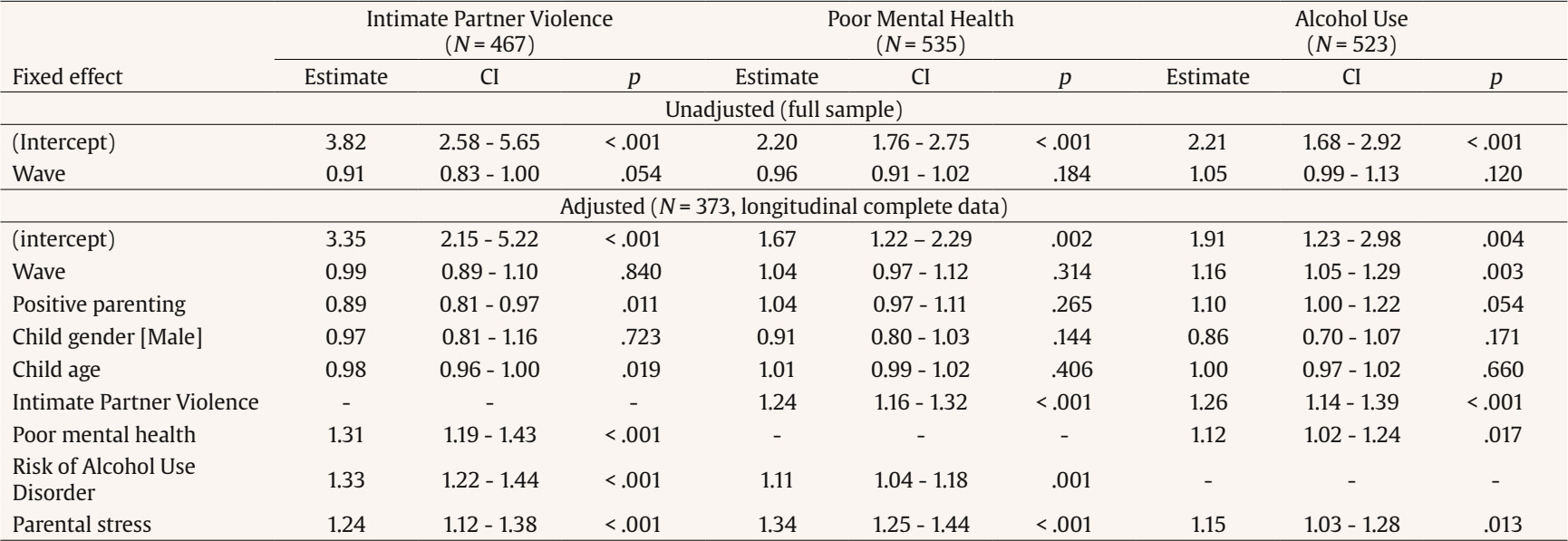

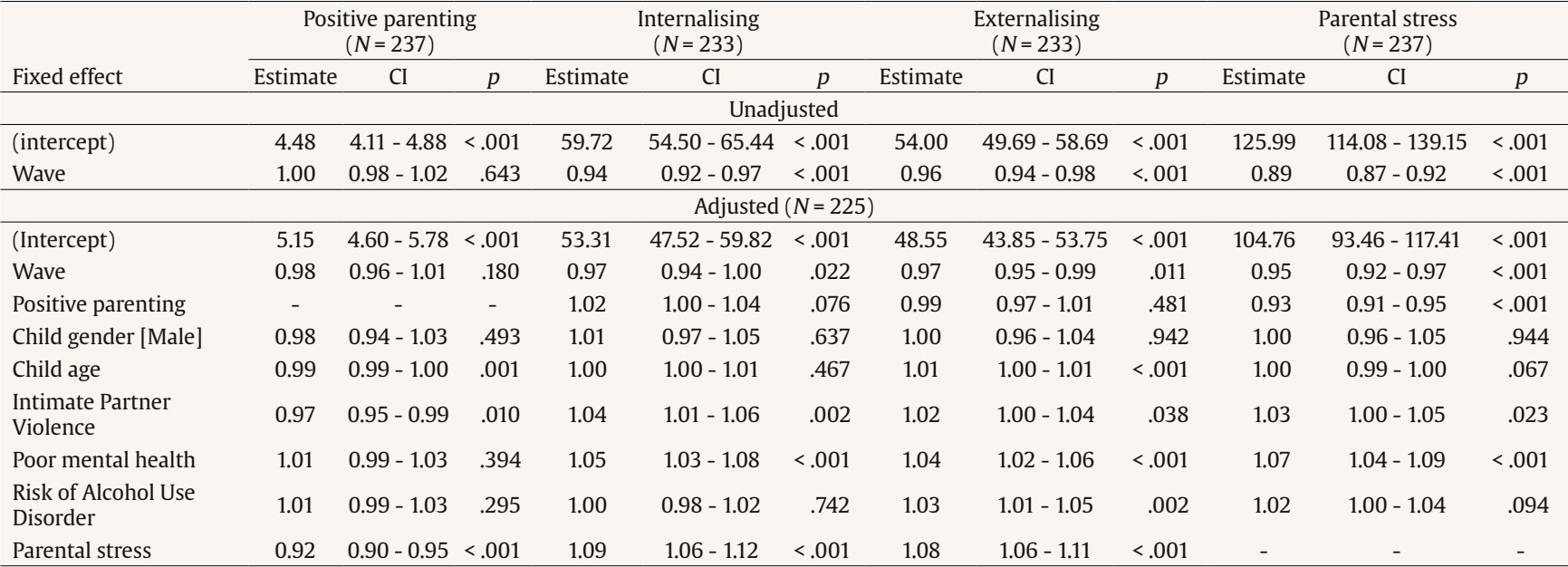

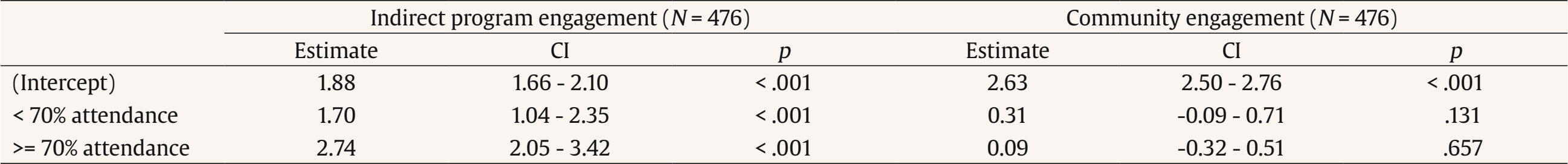

Correspondence: Catherine.Ward@uct.ac.za.Estimates suggest that half the world’s children are exposed to violence, and that rates are higher in low- and middle-income countries (Hillis et al., 2016). Violence against children has both short- and long-term outcomes that can have serious effects on children’s development. These include mental health problems (both internalizing and externalizing), risk behaviours, physical health problems, developmental delays (Hillis et al., 2016) and economic impacts, such as lower wages in adulthood (Zheng et al., 2018). For governments, violence against children can have high costs: for instance, in South Africa in 2015, violence against children was estimated to have cost ZAR238.58 billion, or 6% of South Africa’s gross domestic product (Fang et al., 2017). The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals set the aspirational target of eliminating all forms of violence against children, everywhere, by 2030 (Target 16.2). Parenting programmes – structured intervention to help parents improve their relationship with their child and shift to non-violent discipline strategies, often delivered over a number of weeks (World Health Organization, 2022) – are recognized as an effective strategy to prevent violence against children in the home (Backhaus et al., 2023). Given the ambition of Target 16.2, it follows that parenting programmes should be available to all parents who need them. However, not all parents enrol in programmes, even if they are freely offered, and not all those who enrol actually attend, or, if they attend, engage with the material (Finan et al., 2018; Mytton et al., 2014). Key barriers to parents’ participation in programmes include the time demands of programmes versus other demands such as those of work (Dumas et al., 2007), multiple stressors facing disadvantaged families and lack of readiness to attend (including because of parental substance abuse) (Furlong & McGilloway, 2015; Mytton et al., 2014), concerns about group participation, fear that participation would stigmatise parents as “bad” parents; and for men specifically, a reluctance to participate in what may be perceived to be a women-only group activity (Mytton et al., 2014). Parenting behaviors are not shaped in isolation but within broader community norms and social networks (Ganz et al., 2020). Norm diffusion effects allow parenting practices to extend beyond direct program participants, as parents model behaviors and reinforce attitudes within their social circles (Cislaghi et al., 2019; Valente, 2012). In addition, successful parenting programmes often owe some of their success to building parents’ social support networks (Whittaker & Cowley, 2012). However, many parenting interventions overlook these indirect influences, despite their potential to sustain community-wide behavior change (Marcus et al., 2020) and the recognition that changing norms may assist in keeping children safe (World Health Organization, 2016). Public awareness campaigns targeted broadly are an intuitively obvious way in which to disseminate parenting information cheaply and widely, and so to change norms, but are also limited in their effects: on their own, they may change parental attitudes (such as expectations of child behaviour) (MacLeod & Nelson, 2000) but are less likely to change actual parenting behaviour (Mikton & Butchart, 2009). However, awareness campaigns in areas such as substance use, diet, HIV prevention and cancer screening, have been found to be effective under certain conditions: when they are complemented by other individually-targeted programmes, are communicated through multiple channels, and maintain high exposure over time (Backinger et al., 2003; Verplanken & Orbell, 2022; Wakefield et al., 2010). Together, then, it may be that community-wide media interventions coupled with parenting programmes might overcome a number of barriers to programming, including by reducing the stigma of programmes, disseminating positive parenting information widely, and increasing parents’ readiness to attend programmes. Our earlier work in the community of Touwsranten, in a rural area in the Western Cape Province of South Africa, suggested that there was both a need and a desire for parenting support (Ward et al., 2024). Surveys and qualitative interviews had identified that child mental health problems were prevalent, and that while positive parenting strategies were frequently used by parents, corporal punishment and emotional abuse were also frequent. Parents also reported high levels of parenting stress, compounded by parent mental health issues, risky drinking, and intimate partner violence (Ward et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2024). More positively, parents also indicated that they were interested in parenting support (Ward et al., 2015). We therefore designed an intervention that would offer parenting programmes freely to parents in the community, alongside a social activation process initiated through participatory action methods. Together, the parenting programs and the social activation process were intended to support aspiration for positive parenting (Parker et al., 2020) and thus to both shift norms and disseminate positive parenting values and actions in many ways throughout the community, leading to community-wide changes. We were hoping to achieve the following outcomes across the community as a whole: to increase positive parenting, to decrease harsh parenting, and to improve children’s mental health. This paper reports on the outcomes from the first three years of this intervention, documenting trends in positive parenting, corporal punishment, and children’s mental health. Setting Touwsranten is a small peri-urban village, historically separated under Apartheid from neighbouring, more affluent, areas reserved for White people. The 2011 census put the population of Touwsranten at 2,245. In terms of state services, there is one primary school, a clinic, and a library. Employment is largely to be found in manual labour on nearby farms or national parks, or cleaning houses or as restaurant waitstaff in the more affluent communities nearby. In 2011, 769 adults were employed and 731 unemployed (Statistics South Africa, 2021). The choice of Touwsranten as a location for this study was determined by several factors. Firstly, Touwsranten is a stable community with defined geographic boundaries and low rates of in- and out-migration, particularly amongst the majority Afrikaans-speaking population. This made it possible to track caregiving and child behaviour in a longitudinal sample over time. Secondly, Touwsranten is home to a stable community-based organisation, the Seven Passes Initiative, that had provided after-school care to children aged 5-18 of the community since 2008, as well as occasionally other forms of family support such as referrals for counselling and food parcels. The Seven Passes Initiative was the only charitable organisation in the community, and had strong links to the community, the local school, the clinic, and local churches. It therefore had a strong base for making referrals, understood local issues, and wanted to offer a broader range of family support services with a view to improving children’s and young people’s outcomes socially and academically. A community audit in January 2016, prior to the baseline survey, identified 762 households in Touwsranten, of which 481 (63.1%) included children. A total of 838 children were identified: 22 aged 4-7 months, 159 aged 12-30 months, 325 aged months-9 years, and 332 aged 10 and older. The number of children per household in Touwsranten ranged from one to six (M = 1.74, SD = 1.12). Intervention The intervention had two components: delivery of parenting programmes to individual parents or groups of parents and a community-wide action media programme. Staff of the Seven Passes Initiative were trained to deliver the four Parenting for Lifelong Health (PLH) programmes (see https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/parenting-for-lifelong-health) each of which has evidence for promoting positive parenting (Cluver et al., 2018; Cooper et al., 2009; Vally et al., 2015; Ward et al., 2020). These programmes were developed in South Africa and therefore had good cultural and linguistic fit, and materials were available at no cost. The Parent-Infant Home Visiting Programme provides information on children’s social and emotional development, as well as supportive advice, during home visits that begin during pregnancy and continue for the first six months of the baby’s life. It has been shown to improve mother-child attachment (Cooper et al., 2009). The Book-Sharing programme is a cognitive and socio-emotional stimulation programme in which parents are trained to do dialogic book sharing with their young children, and which improves children’s vocabulary and ability to sustain attention (Vally et al., 2015). It is delivered to small groups of parents and children. PLH for Parents of Young Children (aged 2-9) and for Parents and Teens (aged 10-17) are group-based parenting programmes designed to reduce harsh, inconsistent parenting and improve positive parenting and children’s behaviour (Cluver et al., 2018; Ward et al., 2020). Unfortunately, at the time, it proved impossible to identify an isiXhosa-speaking parenting programme facilitator, and this meant that although the intervention was offered community-wide, effectively only the Afrikaans-speaking community members (approximately 75% of the community) could be directly engaged in the programmes. Alongside these, a social activation process (Parker & Becker-Benton, 2016) was initiated in 2016 with a participatory action media workshop with 15 parents and caregivers (Parker et al., 2020). This approach was chosen because it is very much more active and participative than simply disseminating parenting information. It is therefore more likely to change norms, and has demonstrated success in South Africa before (Parker & Becker-Benton, 2016; Parker et al., 2020). The four-day process included large and small group discussions, community mapping, role plays, visualisation activities, testimonies and games. These activities allowed for in-depth exploration of diverse aspects of parenting in Touwsranten and led to the identification of common attitudes and values related to positive parenting. These were translated into a slogan, songs, a manifesto, and a logo. A Social Activation Group was established, led by a steering committee comprising community members, with the intention of driving ongoing community action to support the values that were identified in the initial workshop. The Parent-Infant Home Visiting Programme was offered on an ongoing basis. Book-sharing was also offered regularly, while the two longer programmes (Parenting for Lifelong Health for Young Children and for Parents and Teens) were offered at least twice a year. While regular meetings of the Social Activation Group were held, it was difficult to sustain participation in the group over time. Nonetheless, a range of activities were carried out over the three-year period. These included street clean-ups, household visits, repair of equipment such as swings in a local park, holding family-oriented community events, and painting of a mural. Many signed the manifesto describing values related to change in Touwsranten and displayed stickers with the ‘Samewerking vir ’n beter gemeenskap’ [‘Working together for a better community’] on the doors of their homes. Participants Caregivers were invited to participate in the study if they were residents of Touwsranten and the primary caregiver of a child under the age of 18; one caregiver per child was interviewed. Each caregiver was asked to choose their eldest child under 18 years old as the focus for the survey. Caregivers were followed (if they gave consent at each wave) across all three waves; parents new to the community at each survey point were also included. In total, 583 unique parent-child dyads were recruited into the study across waves 1, 2, and 3. In 47 cases, a different parent or child responded to the surveys at different waves. After restricting the sample size to only those dyads with consistent parent-child respondents across waves, 536 parent-child dyads were included in the sample. This included 453 dyads at wave 1, 316 dyads at wave 2, and 406 dyads at wave 3. Sample size was smaller at Wave 2 because some households refused to be interviewed, anecdotally because a retrenchment from employment with the Seven Passes Initiative had caused dissatisfaction in the community. Procedure The community audit was followed by three community-wide surveys of caregivers (January 2016, June 2017, and February 2019) to assess parenting, child behaviour and factors impacting parenting and child behaviour in Touwsranten. The 2016 survey of caregivers and children served as a baseline, before the intervention had been implemented. The further two waves of data gathered in June-July 2017 and February-March 2019 assessed parenting behaviour community-wide, social networks of the Afrikaans-speaking mothers, and moderating and mediating factors, during the delivery of the intervention. Quantitative data were collected from parents using handheld devices (Android phones or tablets) with the Mobenzi (www.Mobenzi.com) interface: caregivers could choose either to complete the questionnaire themselves or to have the assistance of an interviewer. Interviewers were trained to ensure that the device screen was always visible to parents to ensure accurate reporting. Interviews took about 90 minutes to complete, and parents had a break and some refreshments approximately halfway through. In the last wave, parents were also offered a food voucher for the local shop to thank them for their participation. Parents were also invited to give permission for children aged ten or older to be surveyed. Children whose parents consented and who themselves gave informed assent, then completed a paper questionnaire either on their own or with the assistance of an interviewer. All interviews were completed in private settings by trained interviewers. In terms of intervention monitoring, the Social Activation Group kept minutes of their meetings. Programme attendance was recorded by programme facilitators for each parent for each programme, and facilitators’ fidelity to the programme was assessed in weekly supervision sessions. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities, University of Cape Town (Reference no. PSY2015-014). Measures Questionnaires were translated into the two local languages, Afrikaans and isiXhosa, with translations checked by back-translation. Demographic Data Demographic information collected about participants included the participants’ preferred language, gender and age, relation to the focus child, marital status, and employment status. Children’s Mental Health The Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) for children aged 6-18, and the pre-school CBCL (for children aged 1.5-5), were used to assess children’s emotional and behavioural problems (Achenbach & Ruffle, 2000; Ebesutani et al., 2010). Parents responded to statements such as “Can’t concentrate” on a 3-point scale: 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), 2 (very true or often true). Initial studies suggested that the CBCL has reliability and validity in many cultural contexts (Achenbach et al., 2008), including in South Africa (Nöthling et al., 2013). In this study, the pre-school CBCL had Cronbach’s alphas of .93 (internalising) and .91 (externalising), while the CBCL for older children had Cronbach’s alphas of .86 (internalising) and .89 (externalising). Parent Self-report of Positive Parenting The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) Global Parent Report (Essau et al., 2006) was used to assess the parenting behaviour, related to youth and conduct problems, in parents of children 6 -18 years old in this study. It is specifically designed to assess parenting associated with conduct problems and delinquency in youth (e.g., “You slap your child when he or she has done something wrong”; “You hug or kiss your child when he or she has done something well”). The APQ is a 42-item questionnaire for parents, and has five subscales, namely: (a) poor supervision and monitoring, (b) parental involvement, (c) positive parenting, (d) inconsistent discipline, and (e) corporal punishment (Shelton et al., 1996). Following our earlier work, where it appeared that parents had struggled with the 5-point Likert scale for answers (Ward et al., 2015), we adapted the answer scale so that each question had only three possible answers: always/often, sometimes, seldom/never. Cronbach’s alphas for these scales were all over .70 in this sample except for inconsistent discipline and corporal punishment, which both had alphas of .58. For this reason, the inconsistent discipline subscale was not included in our models, and we used the three corporal punishment items (spanked with the hand, slapped, and beaten with an object) as individual items in our models. The other APQ items were summed to give a positive parenting score, and this had a Cronbach’s alpha of .73. Two subscales – Setting Limits and Supporting Positive Behaviour – from the Parenting Young Children Scale (PARYC) (McEachern et al., 2012) assessed the parenting behaviours of parents of children 18 months to 5 years (e.g., “How many times in the past month did you teach your child new skills?”; “How many times in the last month did you stick to your rules and not change your mind?”). The original validation study among high risk caregivers in the US found good reliability (McEachern et al., 2012), and it has successfully been used in South Africa before (Ward et al., 2020). In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was .89 for Supporting Positive Behaviour and 0.91 for Setting Limits, , so both scales were retained. These were also summed to give a total positive parenting score for this age group, and had a Cronbach’s alpha of .89. The corporal punishment items from the APQ were also used with this age group in waves 2 and 3 of the study. Child Report of Parenting Children aged 10 or over were invited to complete the Child Report Questionnaire of the APQ (Shelton et al., 1996). This questionnaire includes 37 items regarding female caregiver’s behaviour towards the child, and equivalent questions pertaining to male caregiver’s behaviour. The child-reported Involved Parenting and Positive Parenting had alphas of .81 and .84 respectively, but child reports of poor parental monitoring and inconsistent discipline had low Cronbach’s alphas (.36 and .21 respectively) and so were excluded from analyses. The sum of the other items gave a child report of positive parenting, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .74. Factors Putting Positive Parenting at Risk Parental mental health problems, substance misuse, parenting stress, and intimate partner violence can all be associated with harsh, inconsistent parenting (Chiesa et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2024; Reupert & Maybery, 2016; Solis et al., 2012), and therefore these were also assessed. The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) was used to assess respondent’s mental health, using the binary scoring method whereby any score equal to or greater than 4 indicated ‘psychiatric caseness’ (Goldberg & Hillier, 1979). It has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of psychological well-being in a wide range of contexts , and in this sample had a Cronbach’s alpha of .91. The alcohol subscale from the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement test (ASSIST; World Health Organization, 2010) was used to assess alcohol misuse, since alcohol was the most widely used substance in Touwsranten. The ASSIST has been found to be valid and reliable widely around the world (Humeniuk et al., 2008), including South Africa (van der Westhuizen et al., 2016), and in this sample Cronbach’s alpha was .74. The Parenting Stress Index Short Form (Abidin, 1990) was used to assess parenting stress. This is a 36-item self-completion scale that quickly screens for stress in the parent-child relationship (e.g., “my child is not able to do as much as I expected”). It has been found to have good reliability and validity in a variety of contexts, and following norming in a US sample, scores between the 85th and 89th percentiles are regarded as high, and those in the 90th percentile or higher are considered clinically significant (Abidin, 1990). Cronbach’s alpha in this sample was .95. Thirty-two items exploring psychological and physical aggression from the Conflict Tactics Scale-Revised (Straus et al., 1996) were used to assess levels of intimate partner violence. The measure has been found to have good internal consistency and factor validity in diverse samples (Chapman & Gillespie, 2019), and in this sample had a Cronbach’s alpha of .95. Involvement in Social Activation A series of 16 items assessing aspects of the social activation process were developed for this study, addressing questions such as involvement in the social activation activities and community-related activities. Multiple correspondence analysis was conducted to derive potential latent dimensions, of which two dimensions emerged. One dimension consisting of 12 items, Programme Indirect Engagement, assessed any type of indirect involvement with social activation activities and included items such as “You have a positive parenting T-shirt” and “You live with someone that has completed a parenting programme.” The second dimension, Community Engagement, assessed one’s involvement in community activities that were promoted by the Social Activation Group, and included 4 items such as “You have used the clinic, library or crêche in the past year.” See Appendix 1 for details of the scale and the analysis. This measure was used in the second and third surveys: the programme indirect engagement subscale had a Cronbach’s alpha of .84, and the community engagement subscale an alpha of .85. Data Analysis Since two different measures were necessarily used for assessing positive parenting, scores for each age group were then centred, and the z-score used in analyses. Given the differences in scale ranges across variables, all model covariates were also mean centered and scaled. In addition, all model outcomes, excluding corporal punishment items, were logarithm-transformed to assist in interpreting model coefficients as percentage changes. Log-transformed mixed-effect models using the lme4 package in R (Bates et al., 2015) were used to investigate trends in positive parenting and child internalizing, and externalizing behaviour in the community over the three waves of the study, as well as to identify the major covariates that were associated with these outcomes. Additional models were used to test whether programme attendance and social activation were associated with changes in positive parenting, parental stress, child internalizing and externalizing behaviour across waves 3-5, by including interaction terms. Trends in corporal punishment were assessed over all three waves for older children, and the last two for younger children, using Wilcoxon. Signed Rank Tests, whilst the potential impact of social activation and programme engagement on corporal punishment was assessed using Kruskal-Wallis tests attendance and Spearman correlation tests and Kruskal Wallis tests, respectively. Given sample size differences across the waves, a sensitivity analysis was conducted by comparing all model estimates to findings from a smaller complete subset, which included the 373 parent-child dyads who had participated in all three waves of the study and had complete covariate data. This was to assess to the extent to which the assumption of missing data at random (MAR) was upheld and assess whether findings could be generalized to the broader Touwsranten cohort. Estimates were considered consistent across samples if those of the complete subset fell within the 95% confidence intervals of full cohort estimates (see Figure 1 for details of the sample size). Sample Characteristics Table 1 provides the characteristics of the sample at baseline and the following two waves of data collection (18 months apart). At baseline, 160 parents (24%) chose to complete the questionnaire in isiXhosa, and 339 (76%) in Afrikaans. This meant that a quarter (24%) of the parents were unable to access the parenting programmes since they were delivered in Afrikaans rather than isiXhosa, a percentage that remained largely stable over the three years of the study. The average child age was between 8 and 10 years across the waves. Child gender distributions were fairly equivalent across waves, except for Wave 3, which included a greater proportion of boys. Eighty percent of parents interviewed at baseline were female, with this proportion increasing across the waves. The mean parent age at baseline was 35. Most (281, 62%) parents were married or co-habiting at baseline. Most were biological parents (91.61%), followed by grandparents (5.52%), foster parents (0.88%) or other (0.88%), adoptive parents (0.66%), and stepparents (0.44%). Intervention Processes and Participation Parenting programme quality and fidelity was assessed in weekly supervision sessions, and judged to be excellent by the supervisor (who was independent of this study and of facilitator training). The Social Activation Group (effectively a small committee organising family-oriented community events and positive parenting messaging) struggled to maintain as a committee and to plan effectively, but with support from the Seven Passes Initiative, did manage to organise some community events. Positive parenting stickers and T-shirts remained available to all who took part in a parenting programme, and were increasingly in use across the community, as planned. The third community-wide survey found that more than half of community members (53%) had heard of the Social Activation Group (Saamstaangroep) and around a fifth (21%) had attended an activity held by the group. A fifth (20%) had signed the ‘Saamstaan’ (‘Stand together [to support children]’) manifesto. Over the course of the study, 110 parents (20.5%) attended a parenting programme, and by Waves 2 and 3, on average parents recognized two or three aspects of the social activation programme, and had themselves participated in two or three community events. Trends in Children’s Mental Health, Parenting Strategies and Correlates, Programme Engagement Table 2 provides the scores in children’s internalising and externalising, positive parenting, corporal punishment, and correlates of parenting and children’s outcomes (alcohol use, parenting stress, parent mental health, and intimate partner violence), across the three survey waves. At baseline, 88 (23.6%) children fell into the clinical or borderline clinical ranges for internalizing disorders on the Child Behavior Checklist, and 64 (17.0%) for externalizing disorders. For older children, parents reported using positive parenting strategies often, seldom using poor monitoring, often being involved in their children’s lives, and using spankings sometimes. Older children also reported on their parents’ parenting tactics, and reported high levels of positive parenting. For younger children, parents reported using moderate levels of limit setting and of supports for positive behaviour. Table 2 Sample Scores by Wave for Parenting and Correlates   Note. 1 = (Wave 1 n = 86); 2 = (Wave 2 n = 76); 3 (Wave 3 n = 38). In terms of corporal punishment, slapping and beating with an object were reportedly seldom used by parents, and showed no change over time. In the community-wide sample, there was a possible trend towards a decrease in parent-reported spanking (V = 4447, p = .05). Corporal punishment of younger children was unfortunately not measured at baseline. In terms of factors likely to affect parenting practices, at baseline, 82 parents (18%) reported being in poor mental health, 87 (18.8%) reported risky levels of drinking, 136 (30%) reported intimate partner violence in their current relationship, and 133 parents (30%) reported high levels of parenting stress (53, 12%, in the top 20th percentile). Trend analyses for the whole community (see Figure 2 and Table 3), both unadjusted and adjusted for risks influencing parenting, showed that there was no significant change in parent-reported positive parenting over the study period. Positive parenting, as reported by the children aged ten and older, also showed no change over time (B = 0.94, 95% CI [0.87, 1.02], p = .147). Despite the lack of change in parenting strategies, children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms both demonstrated significant (albeit small) decreases over time: 5% and 3% in unadjusted models respectively, and 4% and 3% respectively in adjusted models (see Table 3). Notably, parenting stress declined significantly (by 10% in the unadjusted, and 5% in the adjusted, models) over the three survey waves. Table 3 Log-transformed Mixed-effect Models of Parenting, Child Behaviour and Parenting Stress over Time   Among the correlates of parenting, intimate partner violence, parent’s poorer mental health, alcohol use and greater parenting stress were all associated with increases in children’s mental health symptoms in both cases. There were no significant changes in reported intimate partner violence, parent mental health, or alcohol misuse over time (see Figure 2 and Table A2.2 in Appendix 2). Table 4 details associations between intervention components (attending a parenting programme and social activation components) and changes in positive parenting, children’s internalising and externalising symptoms, and parenting stress. It shows small but significant changes community-wide in children’s internalising and externalising, as well as in parenting stress. In terms of the association between outcomes and the intervention, in the unadjusted and adjusted models, attending a parenting programme, regardless of how many sessions were attended, was not associated with using more positive parenting strategies or changes in children’s mental health or parenting stress. With regard to the social activation component of the intervention, indirect programme engagement such as living with someone who had attended a programme, was associated with 3% less positive parenting, 4% more internalising and 5% more externalising in children, and with 8% more parenting stress. Community engagement had no relationship with changes in parenting, children’s mental health or parenting stress, in the unadjusted model. In the adjusted model, there was a similar pattern for programme indirect engagement: 4% less positive parenting, 5% more internalising and 6% more internalising in children, and 8% more parenting stress. Community engagement was associated with a 5% drop in positive parenting, but had no relationship to any other outcome. Table 4 Log-transformed Mixed-effect Models Examining the Association between Program Attendance and Social Activation on Changes in Parenting, Child Behaviour, and Parental Stress between Waves 1-3   Note. 1Reference category: no parenting programme attendance. In summary, we therefore found no change in positive parenting, and only a trend towards a reduction in corporal punishment, in the community, but statistically significant (if small) declines in parenting stress and in both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children over time. A fifth of parents in the community (20.5%) attended at least one of the parenting programmes at least once, but attendance was not associated with any change in positive parenting. Most parents had at least some awareness of the social activation programme, but it never became entirely community-driven: the Seven Passes Initiative was always left to stimulate participation and take the lead in organising activities, despite a number of attempts to capacitate members of the community to take ownership. The social activation activities were associated with small negative changes in all the outcomes assessed. The high levels of positive parenting reported at baseline may have created a ceiling effect, that is, levels were high enough at baseline that little change was discernible using the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire and the Parenting of Young Children scale. It also demonstrates that most parents were aware of positive parenting strategies and trying to use them. However, parents in the community also faced a multitude of inter-connected stressors, both in the community and at home, including intimate partner violence, substance misuse and mental health issues, all of which continued to be associated with harsh parenting and children’s mental health problems. Corporal punishment continued, but two things offer some hope. First, we found a possible trend towards a decrease; and second, in a previous analysis of a smaller Afrikaans-speaking sub-sample of all the women (regardless of parenting programme attendance) who completed all three surveys there was a significant decrease in corporal punishment (Kleyn et al., 2021). In this subsample, women became less isolated in terms of parenting support over the three-year period, and it appeared that positive parenting information spread through their denser support networks (Kleyn et al., 2021). It may be, therefore, that three years was too short a time to change a behaviour that was entrenched, and/or that if the isiXhosa-speaking community had been able to access parenting programmes, we may have detected a bigger change. This study does confirm, however, that interventions that ignore substance misuse, parent mental health, and intimate partner violence, may not achieve much change in parenting. These vulnerabilities are common in South Africa and affect both the ability to parent and to engage with parenting programmes. Future programming should consider additionally offering support to overcome these difficulties. Community-wide there were a number of structural issues that put addressing these stressors beyond the reach of a single organization. There was a clinic in the community, but it did not provide any mental health services, not even dispensing medication such as anti-depressants. Accessing care thus meant an expensive and time-consuming trip to other clinics, putting mental health treatment beyond the reach of most in the community. While parenting programmes have sometimes been shown to improve parental mental health in the short term (Barlow et al., 2014), it is likely that long-standing difficulties (which, based on case reports from the Seven Passes Initiative, may have been the case for a number of parents in the community) would need a more intensive intervention. Substance abuse was also widespread in the community and often an integral part of social events: a lack of alcohol-free options for social interaction both tends to promote substance misuse, and undermine attempts to stay sober (Kelly & Ward, 2018). Finally, in families where there is intimate partner violence, this must be addressed, in support of child mental health and child and parent safety. Addressing this via integrating support for co-parenting and appropriate family conflict management into parenting interventions involving both parents may be a fruitful way to address this (Bacchus et al., 2024). Involvement of both parents in such programmes would be key, yet involvement of fathers has been difficult to achieve, both in Touwsranten and elsewhere (Lechowicz et al., 2019). Nonetheless, there are successful examples of father engagement in programmes (de Santis et al., 2020) and promising examples where intimate partner violence has been reduced alongside reductions in violence against children (Doyle et al., 2023; Siu et al., 2024). Despite these difficulties, parenting stress did reduce over the period of the study. Since attending a parenting programme was not associated with a change in parenting stress, and the social activation component was associated with a slight increase in parenting stress, it appears that this may have been due to factors outside of the intervention. Notably, between waves two and three, there was significant roadwork in the community and many community members found short-term employment through this construction. Financial stress has been found to be related to children’s mental health (Lansford et al., 2019), and relief of financial stress has been shown to reduce violence against children (Cluver et al., 2020). This reduction in parenting stress may therefore have been what played a role in the reduction in children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms (Barroso et al., 2017; Fang et al., 2024). This study has a number of limitations. It took place in only one community, and thus we cannot draw clear causal inferences. In addition, the results rely heavily on self-report data from parents, and are thus vulnerable to social desirability bias. However, the parenting data collected from children aged 10-17 and the multiple waves of data collection may have mitigated this effect. In addition, we did not address the extent of individual parent engagement in programmes in our models, and future research should include this, as higher levels of engagement do typically result in increased benefits (Mytton et al., 2014). Despite these limitations, this study has much to offer. While community-wide change did not occur as definitively as we had hoped it would, the success in the smaller group of Afrikaans-speaking women (Kleyn et al., 2021) does suggest that future such interventions would be worth attempting, provided that more attention is paid to enhancing the social activation component; specific attempts are made to include all, including fathers; and programmes include opportunities to address other vulnerabilities such as substance misuse and mental health problems. Including fathers would offer the opportunity to reduce intimate partner violence, and our data suggest (as has been found elsewhere) that this would also increase positive parenting and reduce corporal punishment (Doyle et al., 2023; Siu et al., 2024). This may of course necessitate recruitment strategies that specifically target fathers as well as mothers, and changing the programme content to address inter-parental conflict (Panter-Brick et al., 2014). There are some successful models of programmes that integrate substance abuse and parenting (Neger & Prinz, 2015). While there are fewer examples of integrated parental mental health and parenting intervention programmes (Overbeek et al., 2023), our data suggest that parent mental health cannot be ignored if improved outcomes for children are to be achieved. Our experience with the social activation group suggests that it may indeed have supported positive parenting, but future interventions should also include community development practitioners who can focus specifically on this aspect of the work, and build skills and enthusiasm in the community for taking this aspect of the initiative forward. Finally, future programmes may be wise to provide job skills training and to work in a setting where income generation would be possible to mitigate financial stress on families. In short, parenting programmes, coupled with social activation, may be helpful to families, and there may be value in community-wide interventions. But families living in situations of multiple deprivation need a wide range of services (including economic activities) to improve their lives, and those of their children, alongside parenting interventions. These are not simple to implement, but violence against children arises from complex, intertwined factors, and interventions need to address that complexity. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We are grateful to the community of Touwsranten for graciously participating in this study, to the staff of the Seven Passes Initiative and to our fieldworkers who worked hard to collect the data, to the World Childhood Foundation whose financial support made this work possible, to the parenting programme facilitators (Shannon Buys, Amelia King, Sheridan Kennedy, and Roslynn Wehr-Damons), to Clowns Without Borders South Africa and The Parent Centre for the training they provided to the facilitators, and to the developers of Parenting for Lifelong Health for training and advice. We dedicate this paper to the memory of Helet Theron, who passed away in December 2024, and who provided much behind-the-scenes invaluable support to this work. Cite this article as: Ward, C. L., Lake, M. T., Kleyn, L. M., Mufamadi-Mathebula, D., Parker, W., Peters, S., Dippenaar, W., Gould, C. (2026). A community intervention to increase positive parenting: A three-year cohort study in South Africa. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260810. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a2 Funding: This work was generously supported by grants from the World Childhood Foundation. The dataset and its metadata are available at ZivaHub (https://figshare.com/s/2e8008b2bc3d5123b2a6). Appendix 1 Social Activation Measure The group organising the ongoing social activation activities was known in the community as the “Saamstaan Groep” [Stand Together Group] or the Samewerking Groep [Work Together Group]. We developed a questionnaire to assess participants’ awareness of the Social Activation Group’s activities, with the following items:

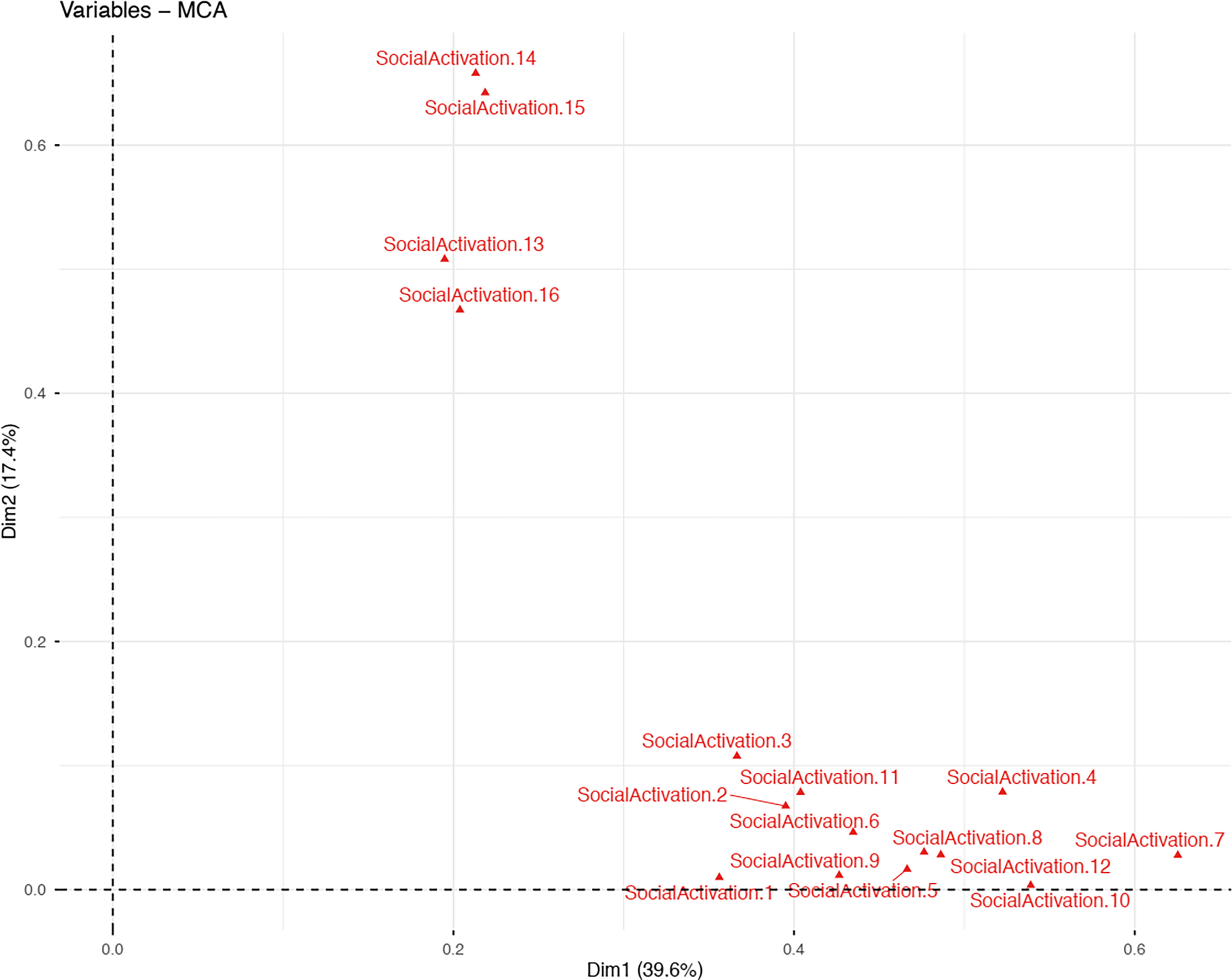

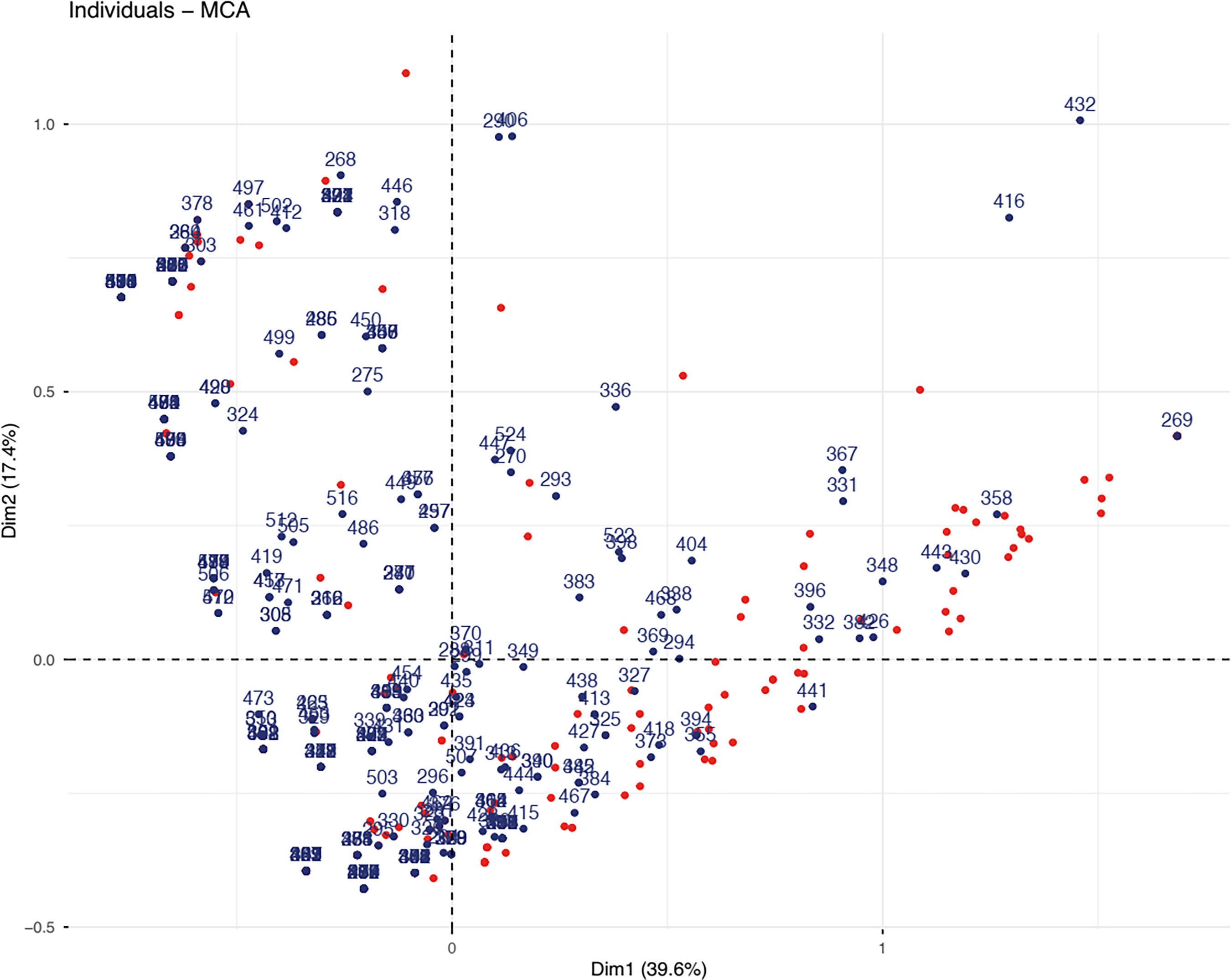

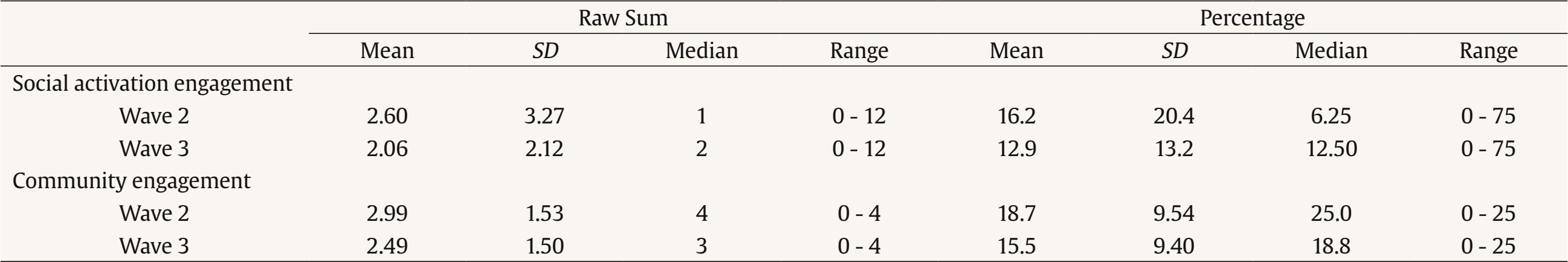

A Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) was conducted in order to reduce the data collected on these Social Activation items into fewer latent dimensions for use as variables in models. More specifically, the MCA was run on data collected at Wave 2 of the intervention phase (collected in 2017), where a two-dimension model was extracted; with dimension 1 and 2 explaining 39.6% and 17.4% of total variance respectively. Dimension 1 (consisting of items 1-12) captured engagement with aspects of the social activation programme (“Social activation engagement”), whilst Dimension 2 (items 13-16) captured engagement within the wider community (“Community engagement”). Figure A1.1 Graphical Representation of a Two-dimension Model, Displaying the Correlation of each Social Activation Item with Two Extracted Dimensions.   The two-dimension model was then used to predict data collected at Wave 3 of the intervention phase (collected in 2019), where Wave 3 data appeared to be somewhat well-predicted by a two-dimension model. Figure A1.2 Graphical Representation of the Predictive Accuracy of Two-dimension Model, where Predicted Wave 3 Coordinates (Dark Blue Dots) Appear to Overlap with Fitted Wave 1 Coordinates (Red Dots).   “Social activation engagement” and “community engagement” variables were computed as the sum of Social Activation items 1-12 and 13-16 respectively. Average social activation engagement significantly decreased from 2.60 in Wave 2 (SDw2 = 3.27, p = .01) to 2.06 in Wave 3 (SDw2 = 2.12, p < .001), although the effect size was small (d = 0.196). Additionally, average community engagement significantly decreased from 2.99 in Wave 2 (SDw2 = 1.53) to 2.49 in Wave 3 (SDw2 = 1.50), with a small effect size (d = 0.333) |

Cite this article as: Ward, C. L., Lake, M. T., Kleyn, L. M., Mufamadi-Mathebula, D., Parker, W., Peters, S., Dippenaar, W., & Gould, C. (2026). A Community Intervention to Increase Positive Parenting: A Three-Year Cohort Study in South Africa. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260810. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a2

Correspondence: Catherine.Ward@uct.ac.za.Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS