Social Determinants of Mental Health in Armed Conflict-affected Municipalities

Diana Carolina Rubio-León1, Laura Cano-Sierra2, María-Juliana Reyes-Rivera2, Pablo Abitbol3, Dennys García-Padilla1, Sara Lucia Forero-García2, & Wilson López-López2

1Psychology and Health Research Group, School of Psychology, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia; 2Social Ties and Peace Cultures Research Group, School of Psychology, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia; 3Regional Group of Historic Memory, Universidad Tecnológica de Bolívar, Cartagena, Colombia

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a1

Received 9 May 2025, Accepted 20 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Armed conflicts affect mental health. In Colombia, many communities have been victims of armed conflict and multiple social inequalities and injustices for more than six decades. Our research explored the social determinants of mental health in fifteen municipalities affected by the armed conflict in Montes de María, Colombia. Method: A convergent parallel mixed methods design was conducted. In the quantitative component, we assessed mental health (PHQ-4 and DASS-21), social support (Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey - MOS), and sense of community (Brief Sense of Community Scale - BSCS) in a sample of 134 leaders and community members. In the qualitative component, we conducted 35 focus groups and held two regional meetings with 167 leaders to further explore the social determinants of mental health in the region. Quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted concurrently, and methodological triangulation was applied to integrate both data types and thus enhance the comprehensiveness and rigor of the findings. Results: The network analysis (23 nodes, sparsity = 0.708) evidenced strong conditional associations linking mental health (depression, stress, anxiety) with sense of community and perceived social support. Sociodemographic variables showed minimal integration. Psychosocial care showed moderate centrality indicating relevant but secondary associations with mental health compared to more central nodes. Qualitative data showed that armed conflict, state abandonment, economic issues, lack of opportunities, and barriers to access mental health services are SDH that have impacted the current mental health of the community. In this context, social capital and communitarian resistance strategies promote mental health in Montes de María. Conclusions: The results suggest that social determinants of health related to social support and sense of community positively impact the mental health of conflict-affected communities. Both quantitative and qualitative findings highlight the region's challenges, their capacity for resilience, and the urgent need for more effective psychosocial interventions for this population, focusing on psychosocial care that builds on the existing social and community support strengths identified in Montes de María.

Keywords

Social Determinants of Health, Mental Health, Armed Conflict, Victims, Colombia

Cite this article as: Rubio-León, D. C., Cano-Sierra, L., Reyes-Rivera, M., Abitbol, P., García-Padilla, D., Forero-García, S. L., & López-López, W. (2026). Social Determinants of Mental Health in Armed Conflict-affected Municipalities. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260809. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a1

Correspondence: lopezw@javeriana.edu.co (W. López-López).

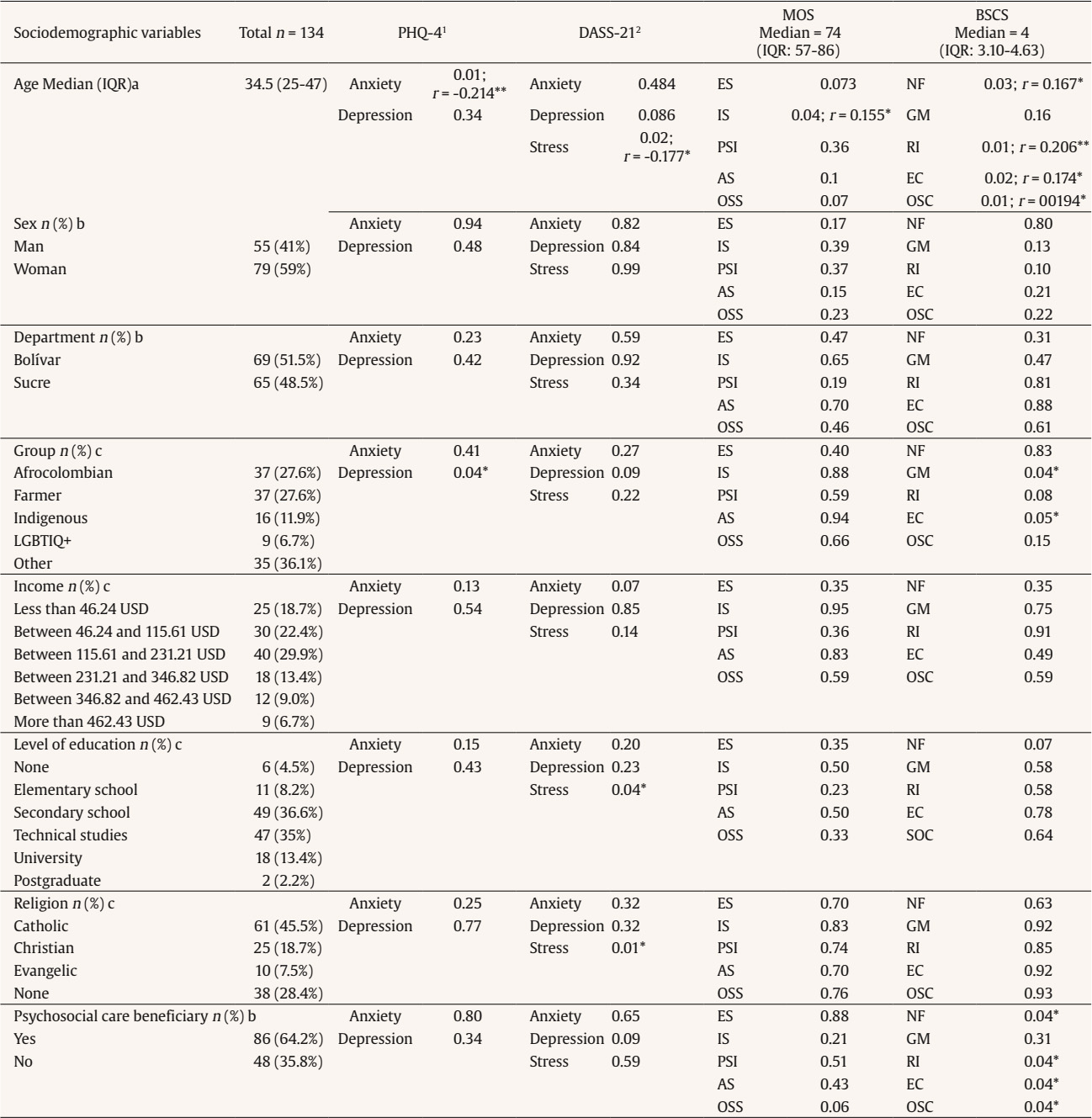

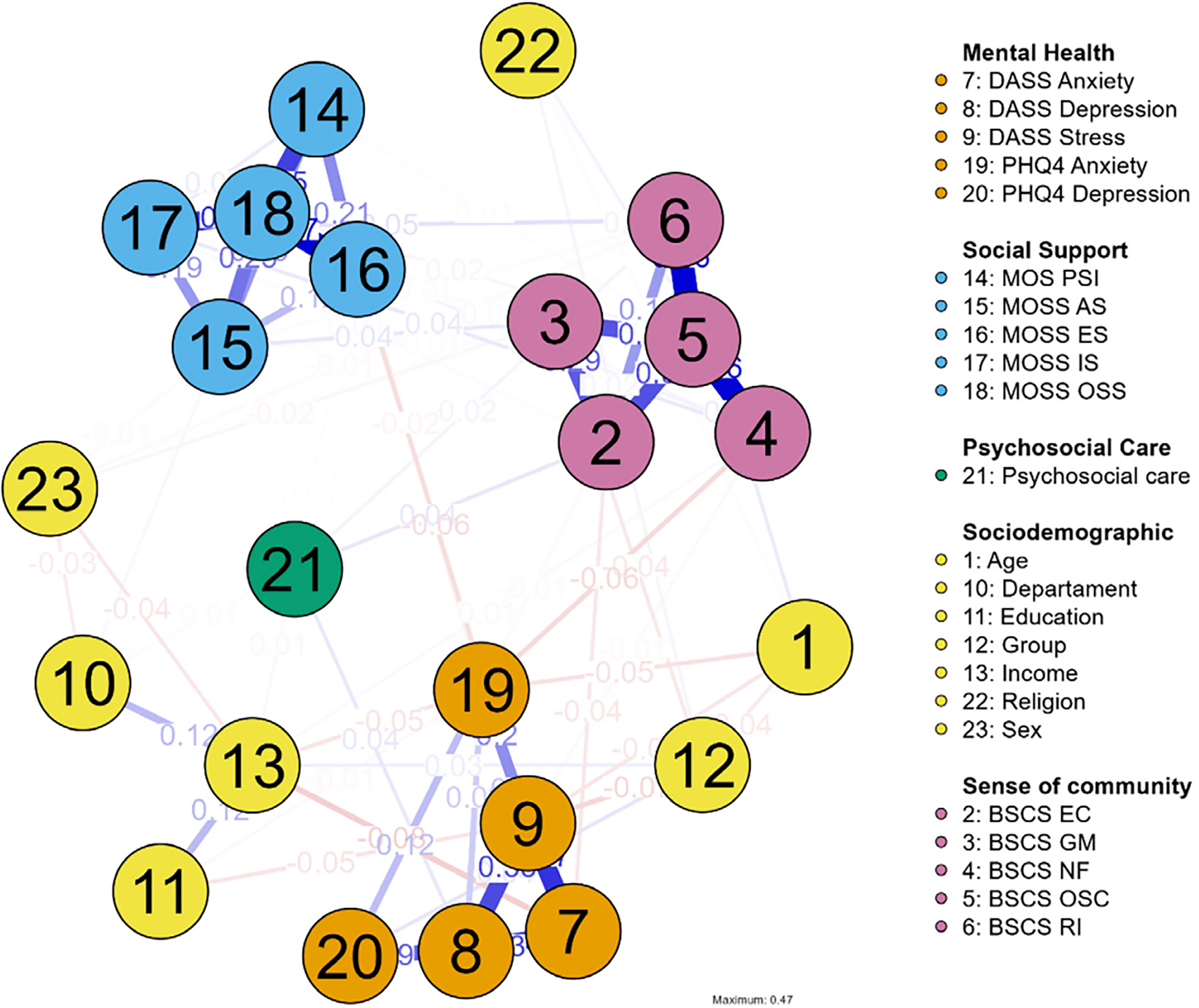

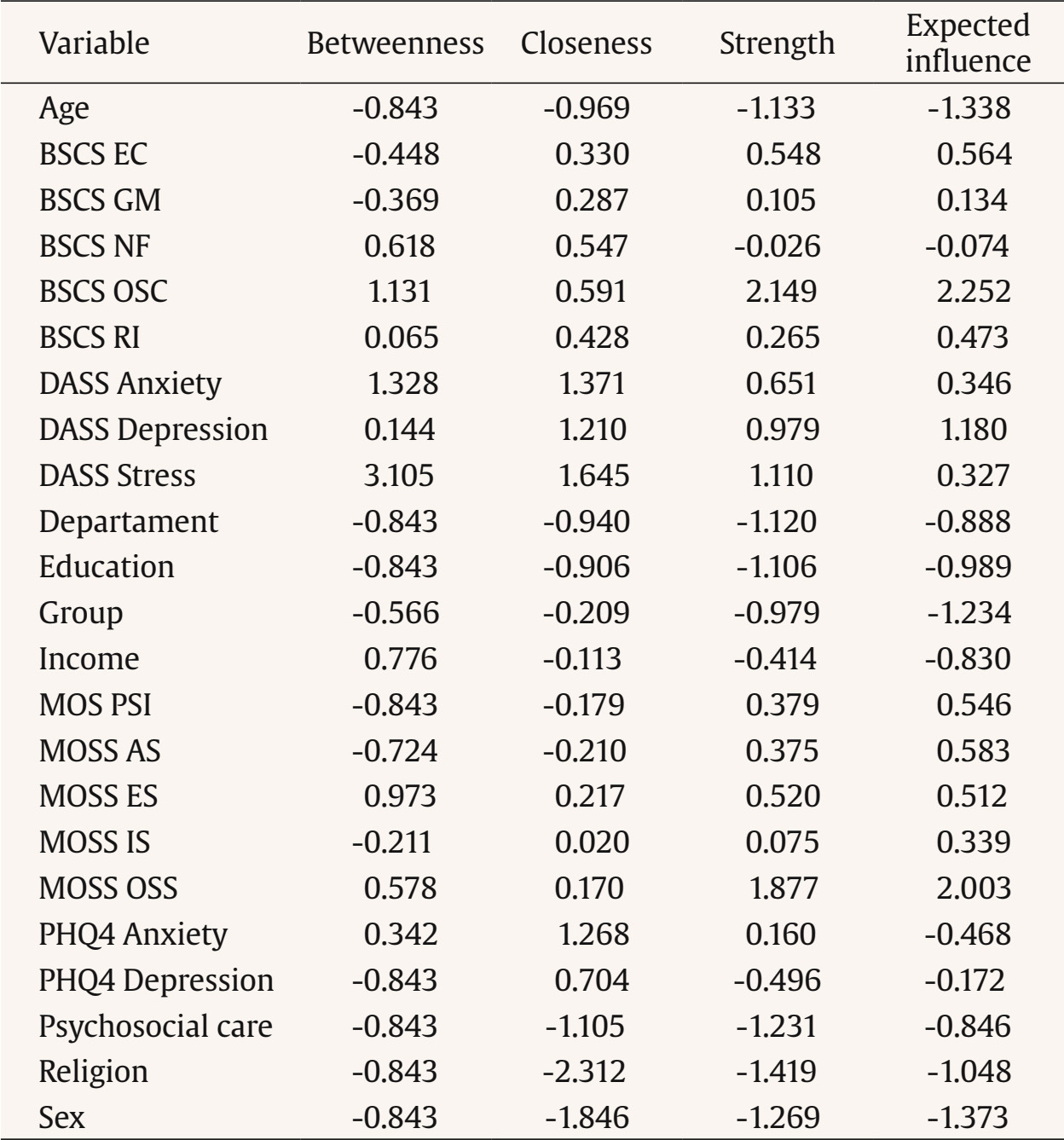

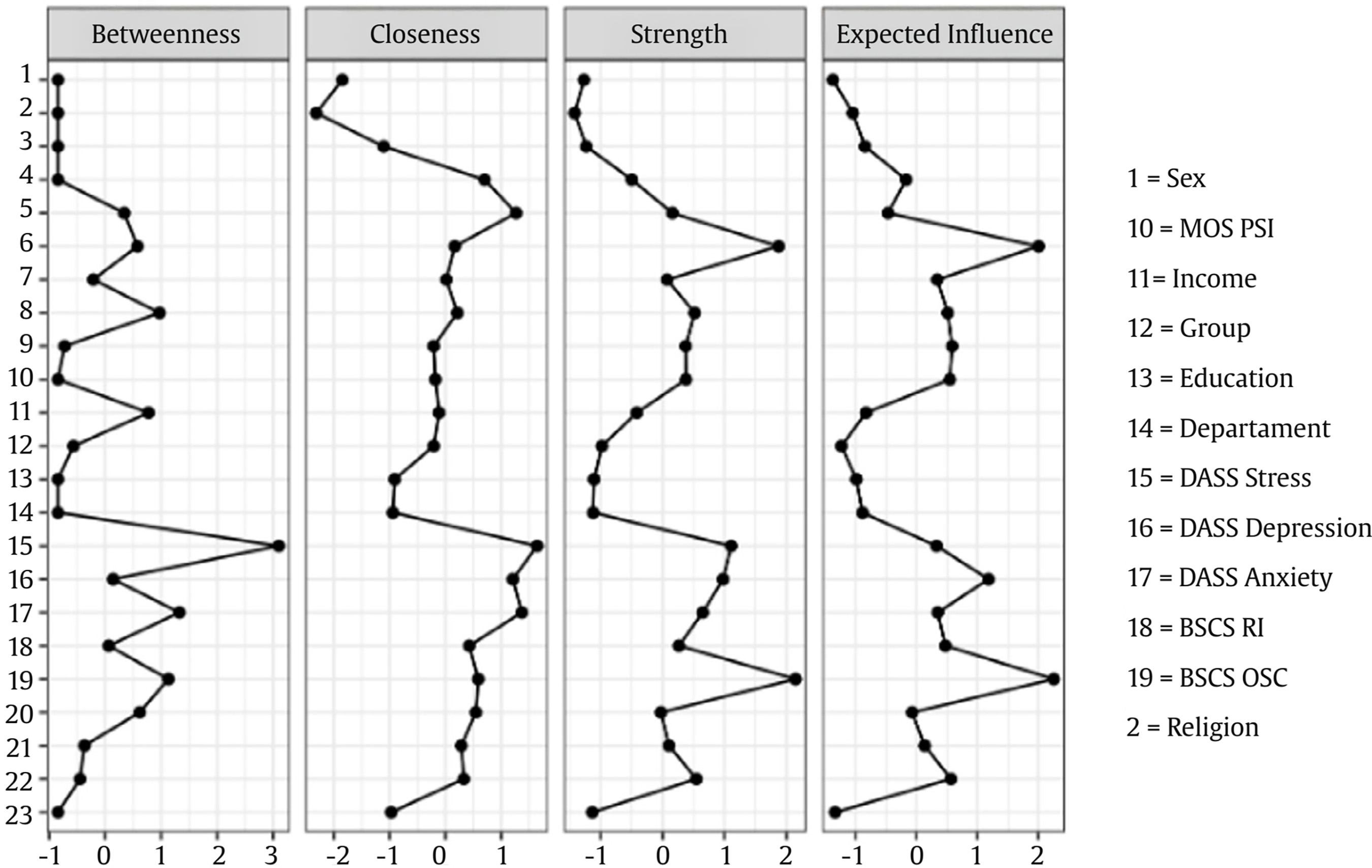

The Colombian armed conflict spans more than six decades and has resulted in more than 9.5 million victims, of which around 80% have been forcibly displaced and have survived other types of victimization (Charlson et al., 2019), causing numerous health impacts, especially regarding Mental Health (MH) (Médecins Sans Frontières, 2023). Multiple efforts to transition to peace have led to the development of transitional justice, which includes psychosocial reparation; however, the conditions of other rights violations, especially in rural populations, have remained constant. Armed groups continue to exist and exert violence, which has an impact on the MH, well-being, and quality of life of people exposed directly and indirectly to violence (Charlson et al., 2019). The burden of mental disorders in conflict-affected populations is high (Charlson et al., 2019), which is related to multiple and complex factors that profoundly impact community and individual MH in conflict-affected settings (Scheuring & Bosqui, 2025; Ubels et al., 2025). For example, in Colombia, prominent MH issues identified include mood disorders, particularly post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety (Castaño et al., 2018; Moreno-Chaparro et al., 2022; Moreno-Murcia et al., 2021; Ramírez et al., 2016; Ramírez-Giraldo et al., 2017). To a lesser extent, eating disorders (Moreno-Murcia et al., 2021), psychoticism and dissociation (Ramírez, et al., 2016), oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, attention deficit disorder, bipolar disorder (Castaño et al., 2018), avoidance of social events, and cognitive difficulties (Moreno-Chaparro et al., 2022) have been reported. Adverse conditions that are exacerbated or directly caused by the armed conflict can be understood through the World Health Organization framework of Social Determinants of Health (SDH) (Bezo et al., 2012; World Health Organization [WHO], 2008) referred to the conditions in which individuals are born, grow, live, work, and age, influenced by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels. These factors shape health inequalities, impacting individuals, groups, and populations through income, wealth, education, access to healthcare services, and social and community networks (Braveman & Gottlieb, 2014; WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2008). In contexts of armed conflict, the SDH framework encompasses economic, cultural, historical, environmental, and political dimensions that shape the living conditions of individuals and communities, thereby affecting their health status (WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2008). In Colombia, the ramifications of armed conflict on health indicators have been documented (Instituto Nacional de Salud & Observatorio Nacional de Salud, 2017) including externally caused injuries, child health, vector-borne diseases, infectious diseases, chronic diseases, reproductive health, vaccination, lack access to health services (Munezero & Manoukian, 2021), and perception of health (González-Uribe et al., 2022). Recognizing the adverse effects of armed conflict on health, Colombia has adopted the SDH in its public health plan including armed conflict as one of the structural determinants of health inequalities and views being a victim or having other roles within the conflict as one of the structural axes of inequality impacting specific health determinants of the population’s health status (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2022). Acknowledging the severity of MH problems, the WHO proposed the Social Determinants of Mental Health (SDMH) (WHO & Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2014) which goes beyond genetic predisposition and individual circumstances, asserting that psychological well-being, MH, and many mental disorders are significantly determined by the social, economic, and physical conditions in which they live. Thus, MH is understood within the framework of inequalities and social justice, especially for groups that are victims of various forms of violence, marginalization, and poverty (Allen et al., 2014; Kirkbride et al., 2024). From this perspective, interventions should take into account factors such as distribution of opportunities, employment, housing, infrastructure, access to health services, food security, community organization, cultural values, social norms, poverty, family stress, abuse, adverse childhood experiences, stress management, parenting practices, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and education among others (Gnanapragasam et al., 2023), and should be articulated with the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Oswald et al., 2024). In consideration of this context, it is necessary to address the MH issues experienced by communities who have been victims of armed conflict and multiple social inequalities and injustices. The region of Montes de María, located between the Colombian provinces of Bolívar and Sucre, has been battered by the conflict given its location and geographic features that make it home to strategic corridors for illicit markets such as drugs, arms, and illegal mining. With the addition of co-optation of state institutions by armed actors, the region has been subjected to multiple forms of violence and experiences heightened negative health consequences (Abitbol, 2022). Nevertheless, this region has also been characterized by multiple community initiatives and organizations that aim to make a significant impact on the processes of truth, justice, and reparation (Fundación Cultura Democrática [FUCUDE] et al., 2020). Many of these initiatives focus on addressing daily problems through the rejection and prevention of violence, as well as the creation of productive initiatives that help meet basic needs (FUCUDE et al., 2020). Additionally, these efforts have helped rebuild cooperation and trust among community members, which has aided in the process of reconstructing social ties. Therefore, this study is motivated by two overarching needs. Firstly, few studies have examined MH from the SDMH perspective in the context of Colombia’s armed conflict (Piñeros-Ortíz et al., 2024), and none have done so specifically in the municipalities of Montes de María. Secondly, effective interventions for enhancing mental health in conflict-affected settings must move toward more ecological, multilevel and multimodal approaches in MH and psychosocial interventions, where community members play a central role (Al-Tamimi & Leavey, 2022; Kamali et al., 2020). Thus, the objective of this research is to explore with a broader perspective the MH and the SDMH in fifteen municipalities affected by the armed conflict in Montes de María, Colombia, with the aim of recognizing context-specific characteristics pertinent to designing psychosocial interventions for this population. Study Design and Setting A convergent parallel mixed methods design (Cresswell, 2015) was conducted, which involves collecting and analyzing quantitative and qualitative data concurrently but separately, followed by triangulation to enhance the validity and depth of the findings (Flick, 2018). Mixed methods research is increasingly applied in psychology due to its potential to enrich quantitative findings and strengthen methodological rigor integrating diverse data sources (Anguera et al., 2020; Creamer & Reeping, 2020). The study was conducted in Montes de María in Colombia, a region consisting of fifteen municipalities from the departments of Bolívar (Maríalabaja, El Guamo, San Juan Nepomuceno, San Jacinto, El Carmen de Bolívar, Zambrano, and Córdoba Tetón) and Sucre (San Onofre, Toluviejo, San Antonio de Palmito, Morroa, Los Palmitos, Ovejas, Colosó, and Chalán) characterized by armed conflict, poverty, state capture, extractive economies, and adaptative structures of macro-criminality (Abitbol, 2022; FUCUDE et al., 2020). Based on community-based participatory research (CBPR) (Lucero et al., 2018), ongoing conversations were held with community leaders during the research project design and data collection to ensure the study’s relevance to the communities. According to the CBPR nucleus, these discussions aimed to produce meaningful results, facilitate the translation of findings to local communities, and improve research by integrating community cultural values and knowledge to address the SDMH. Data collection was conducted in the fifteen municipalities by researchers of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and the Universidad Tecnológica de Bolivar between September and November 2021 and April and December 2023 at different times, considering the challenges imposed by the armed conflict and by the COVID-19 pandemic. Taking into account the constraints and opportunities of the context initial contact was established with community leaders and members from the fifteen municipalities of Montes de María, through previously formed relations with local organizations. These leaders then invited other community members to participate. The study was also presented in community spaces, where additional participants were recruited. Across the quantitative and qualitative data collection, there were participants from 92 social organizations representing afro-descendant, indigenous, farmers, LGBTIQ+, and youth groups who have been victims of threats, sexual abuse, forced displacement, kidnapping, and the murder of loved ones, among other forms of violence. The study was approved by the Psychology IRB at Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained by all the participants. The rigor criteria for mixed-methods studies in psychology were considered (American Psychological Association [APA], 2024). Quantitative Component A cross-sectional and correlational design was used. Participants This sample included 134 leaders and community members (Table 1). Table 1 Bivariate Analysis between Social Determinants and Mental Health, Social Support, and Sense of Community Variables.   Note. 1. PHQ-4: Depression (median = 2; IQR: 1-2), Anxiety (median = 1; IQR: 0-2); 2. DASS-21: Depression (median = 3; IQR: 1.75-6), Anxiety (median = 3; IQR: 1-6), Stress (median = 3; IQR: 2-7). IQR = Interquartile range; ES = Emotional/informational support; IS = Instrumental support; PSI = Positive social interaction; AS = Affectionate support; OSS = Overall social support; NF = Needs fulfillment; GM = Group membership; RI = Reciprocal influence; EC = Emotional connection; OSC = Sense of community; a = Spearman correlation; b = Test Mann Whitney; c = Test Kruskall Wallis. *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01. Given the accessibility of the population, a non-probabilistic convenience snowball sampling technique was used. Inclusion criteria required participants to be over 18 years of age, currently living in any of the fifteen municipalities and have experienced some form of violence related to armed conflict. Instruments Several questionnaires were administered to characterize the participants and to evaluate MH, social support, and sense of community. Sociodemographic Characteristics. A comprehensive set of sociodemographic variables that enables the assessment of the relevant dimensions of inequality within the SDH framework (Bezo et al., 2012) was included in the study. These variables were age, sex, department, group affiliation, income, educational level, religion, and history of receiving psychosocial care. Mental Health Assessment. Two validated questionnaires were employed to assess MH: The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) (Kroenke et al., 2009) consisting of four items with response options ranging from “not at all” (0 points) to “almost every day” (3 points), reflecting the frequency of symptoms of anxiety and depression in adults over the past two weeks. The Colombian validation of the scale was used (Kocalevent et al., 2014), it showed good internal consistency (α = 0.84), validity was established through confirmatory and discriminant analyses, and the fit indices indicated a very good model fit. The Depression-Anxiety-Stress Scale (DASS-21) (Antony et al., 1998), which consists of 21 items reflecting depression, anxiety and stress symptoms over the past week ranging from 0 (“Did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“Applied to me very much, or most of the time”). The Colombian validation of the test by Ruiz et al. (2017) was used, demonstrating high internal consistency (α ranging from 0.92 to 0.95) and a consistent hierarchical factor structure that supports its validity. Social Support Assessment. Recognizing that social capital is a critical SDH (Bezo et al., 2012), and it is defined as the social support, network size, trustworthiness, reciprocity and social interactions available to an individual (Carrillo & Riera, 2017; Lagaert et al., 2021), we used the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (MOS) (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) to assess social support. The MOS consists of 20 items, the item 1 refers to the size of the social network, while the remaining 19 items assess four dimensions of functional social support: emotional/informational support – ES (8 items), instrumental support – IS (4 items), positive social interaction – PSI (4 items), and affective support – AS (3 items). Response options are provided on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The overall social support – OSS is calculated from the sum of the items. Higher scores indicate greater perceived social support. We used a version validated for Colombia (Londoño et al., 2012), which reported a total Cronbach’s alpha of 0.941, with values ranging from 0.921 to 0.736 for the different components and whose validity was established through confirmatory analysis. Sense of Community Assessment. To measure the meso-level of social capital, understood as collective efficacy, community support, trust, civic participation, engagement and reciprocity (Carrillo & Riera, 2017), we used the Brief Sense of Community Scale (BSCS). This scale consists of 8 items that evaluates four dimensions: needs fulfillment – NF (2 items), group membership – GM (2 items), reciprocal influence – RI (2 items), and emotional connection – EC (2 items); each item in a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly agree” to “Strongly disagree” where higher scores indicate a greater sense of community. The overall sense of community – OSC is calculated from the sum of the items (Peterson et al., 2008). The Colombian validated version was used (Palacio-Sañudo et al., 2023), which had a high internal consistency (α = 0.918) and the validity of the test were confirmed through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Analysis Descriptive analyses were conducted for all sociodemographic variables (Table 1). Given that continuous variables violated the assumption of normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), results are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as absolute frequencies and percentages. Bivariate non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney, Kruskal–Wallis, and Spearman correlations) were used to explore associations between sociodemographic characteristics and MH, social support, and sense of community indicators, with a 95% confidence level. These analyses were performed in SPSS version 26. To explore the complex interrelations among study variables, we conducted a network analysis using the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion Graphical Lasso (EBICglasso) method (Isvoranu & Epskamp, 2023) via the Qgraph package in JASP version 19. This approach estimates regularized Gaussian graphical models (GGM), which model partial correlations between pairs of variables while controlling for all others, assuming no unmeasured common causes. GGMs are well suited for psychological data as they focus on the interplay among observed variables and are robust in small samples with sparse structures (Burger et al., 2023). The EBICglasso procedure enhances the graphical lasso by applying an EBIC-based penalty, balancing model fit and complexity while promoting sparsity—weak edges are set to zero, yielding a parsimonious and interpretable network. In the estimated network, nodes represent observed variables and edges represent conditional associations: blue edges indicate positive relationships, and red edges indicate negative ones (Figure 1). Network properties were evaluated through node expected influence (EI), which accounts for both the number and the sign of connections, and bridge strength (BS), which quantifies the extent to which a node connects different communities of variables. This allowed us to identify key variables with the greatest influence and potential bridging roles across domains such as MH, social support, and community sense. Figure 1 Estimated Network Model.   Note. BSCS EC = Emotional Connection; BSCS GM = Group Membership; BSCS NF = Needs Fulfillment; BSCS OSC = Overall Sense of Community; BSCS RI = Reciprocal Influence; MOS PSI = Positive Social Interaction; MOSS AS = Affectionate Support; MOSS ES = Emotional/informational support; MOSS IS = Instrumental Support; MOSS OSS = Overall Social Support. Qualitative Component Descriptive qualitative study (Sandelowski, 2010). Participants The sample included 167 leaders, 107 of which identified as female, and 60 as male. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 78 years (M = 43.4; SD = 1.3). As for their department of origin, 90 of them were from Bolívar and 77 from Sucre. Although some of these participants also took part in the quantitative component, due to the anonymity of the data collection it is not possible to determine any overlap. Therefore, the qualitative and quantitative samples are treated as independent, with data that complement each other and contribute to a deeper analysis and understanding of the SDMH in communities of the Montes de María. Instruments To provide context and support the analysis of the quantitative data, thirty-five focus groups and two regional meetings were conducted to further explore the SDMH in the region. These encounters were led by experts from the research team using a question guide about MH, SDH, effects of the armed conflict, adverse experiences, stressors, community support, community relations, and interactions with MH services. The focus groups and regional meetings were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using NVivo 14. Analysis A content analysis was conducted, with concurrent data analysis and collection and three phases of coding: open, axial, and selective (Schreier, 2014). In the open coding phase, a meticulous line-by-line coding approach was employed, leading to the development of a preliminary codebook, which was continuously reviewed and refined by the research team. Axial coding facilitated the aggregation of data into broader categories, establishing interconnections among them. Selective coding enabled the formulation of overarching categories that elucidated the SDMH within the municipalities. The analysis adhered to the criterion of saturation (Hennink et al., 2019). To ensure methodological rigor (Korstjens & Moser, 2018), the principles of credibility and transferability were carefully upheld. This was achieved through prolonged engagement in the municipalities over several years, fostering an in-depth comprehension of contextual intricacies. The validity of the analyses was further reinforced by presenting the findings to participants during two regional meetings. Throughout the research process, the researchers engaged in a continuous reflexive exercise. Quantitative Results Social Determinants of Health The primary characteristics of SDH among the 134 leaders and community members from the fifteen municipalities of Montes de María that participated in the quantitative phase are presented in Table 1. Participants were predominantly Afro-Colombian, rural farmers, and indigenous individuals. Additionally, members of the LGBTIQ+ community and 35 participants from other demographic groups, particularly young individuals, were also included. Most participants were women (59%). The age range of the participants was between 18 and 68 years, with a median age of 31 [25–48] for women and 37 [26–47] for men. In terms of socioeconomic status, 71% of the participants earned less than the minimum monthly wage (USD 268), and 41.1% earned less than USD 115.61, a significant percentage given that the poverty line in Colombia for 2023 was set at USD 108. Six participants had no formal education, and eleven had only completed elementary education. The predominant religion among participants was catholicism. Furthermore, 64.2% had received psychosocial care. Among those 86 respondents, 56.98% received support from only one institution, 16.28% from two, 17.44% from three, and 9.30% from four or more institutions. The most commonly reported providers of psychosocial care were the Psychosocial Care and Comprehensive Health Program for Victims (PAPSIVI) with 46.51%, followed by Health Promoting Entities (EPS) (44.19%), other participants received care from community organizations and nongovernmental Organizations (NGOs). Among those who received psychosocial care, the most common types of interventions were group talks (90%), followed by workshops (27.5%), individual psychological counseling (20%), psychosocial training sessions (5%), and family psychological counseling (2.5%). Mental Health Regarding MH outcomes, on the PHQ-4 depression scale 21% (14 men and 14 women) had scores indicating the presence of depressive symptoms. On the PHQ-4 anxiety scale 11% (10 women and 5 men) had scores indicating the presence of anxiety symptoms. Regarding the DASS-21, on the depression scale 62% (n = 83) did not have scores indicative of depression, while 38% had depressive symptoms (mild = 25; moderate = 17; severe = 4; extremely severe = 4). On the anxiety scale 62.7% (n = 84) did not show anxiety symptoms, while 37.3% did (mild = 4; moderate = 24; severe = 7; extremely severe = 11). The stress scale showed that 82% (n = 110) did not have stress, while 18% had stress symptoms (mild = 10; moderate = 10; severe = 3; extremely severe = 1). Social Support and Sense of Community Regarding the assessment of social support, the MOS indicated that 23.1% (n = 31) of the participants scored below the established mean for this instrument, while 76.9% (n = 103) scored above the mean. Similarly, the BSCS revealed that 21.6% (n = 29) had a low sense of community, 19.4% (n = 26) had a moderate sense of community, and 59% (n = 79) exhibited a high sense of community. Relationships between Mental Health, Social Determinants, Social Support, and Sense of Community In the bivariate analyses conducted (Table 1), negative correlations were observed between age and PHQ-4 anxiety and DASS stress. Additionally, age positively correlated with the MOS tangible support scale, needs fulfillment, influence, emotional connection of the BSCS, and the overall index of the sense of community of the BSCS. It was found that Afro-Colombians and the LGBTIQ+ community had significantly higher median scores in PHQ-4 depression (p = 0.04). Farmers and indigenous people exhibited significantly higher median scores in the GM dimension of the BSCS (p = 0.04); furthermore, farmers demonstrated a significantly higher median in the EC dimension of the BSCS (p = 0.05) (Table 1). Significantly higher median scores for stress were identified in the group with a technical education level and among those practicing the Christian religion (Table 1). Conversely, the group that received psychosocial support achieved a significantly higher median in the BSCS dimensions. The EBICglasso network analysis examined the conditional relationships between MH domains —depression, stress, and anxiety—and sociodemographic variables, perceived social support, and sense of community (Figure 1). The estimated network comprised 23 nodes and 74 non-zero edges out of a possible 253, yielding a sparsity of 0.708. Regarding MH variables, DASS Anxiety (BS = 0.651, EI = 0.346) (Table 2) emerged as a major connector in the network, linking stress and depression with both social support indicators and sense of community dimensions. DASS Depression (BS = 0.979, EI = 1.180) and DASS Stress (BS = 1.110, EI = 0.327) also displayed significant connectivity, suggesting that these MH indicators share strong reciprocal associations with psychosocial resources (Figure 2). Table 2 Centrality Measures per Variable.   Note. BSCS EC = Emotional Connection; BSCS GM = Group Membership; BSCS NF = Needs Fulfillment; BSCS OSC = Overall Sense of Community; BSCS RI = Reciprocal Influence; MOS PSI = Positive Social Interaction; MOSS AS = Affectionate Support; MOSS ES = Emotional/informational support; MOSS IS = Instrumental Support; MOSS OSS = Overall Social Support. Centrality analyses revealed that dimensions of the BSCS, particularly OSC (BS = 2.149, EI = 2.252), occupied a highly central position in the network (Table 2). This node maintained strong conditional connections with multiple indicators of social support and MH, suggesting that a greater sense of belonging and identification with the community is closely linked to lower distress and higher perceived resources. Other BSCS dimensions, such as EC (BS = 0.548, EI = 0.564) and RI (BS = 0.265, EI = 0.473), also showed substantial centrality, highlighting their structural role in bridging community perceptions with both psychosocial and emotional well-being variables. All social support dimensions were meaningfully integrated into the network, OSS showed the highest connectivity within this group (BS = 1.877, EI = 2.003), reflecting strong conditional links with both MH and sense of community variables: ES (BS = 0.520, EI = 0.512), PSI (BS = 0.379, EI = 0.546), and AS (BS = 0.375, EI = 0.583). Together, these results suggest that diverse facets of perceived support contribute substantially to the cohesion of the psychosocial network, potentially acting as protective factors that link community connectedness with emotional well-being. These patterns indicate that higher perceived social support and stronger community bonds may mitigate psychological distress, while lower scores in these domains could amplify symptoms through interconnected pathways. The analysis also revealed meaningful links between sense of community and social support variables, indicating that individuals who report a stronger identification with their community also tend to perceive higher levels of available support. Sociodemographic variables, however, showed comparatively weaker integration into the network. For example, age exhibited negative values across all centrality metrics (BS = –1.133, EI = –1.338), suggesting limited direct influence on the main psychological constructs when controlling for other variables. Psychosocial care demonstrated moderate centrality (BS = -1.231, EI = 0.846). This dimension does not serve as a primary hub in the network, playing a secondary role compared to the most central nodes such as OSC and OSS, suggesting a supportive but not dominant influence within the overall psychosocial structure. Qualitative Results The following analyses refer to the 167 leaders that participated in the qualitive component of the study. Social Determinants of Mental Health The understanding of MH in Montes de María comes from a contextual and community perspective, that goes beyond the individual and pathological perception of MH: “With mental health and land, we have enough to live”. Consequently, they identified the following elements play an important part in their mental well-being: “Mental health is the balance of trust a person has in their social context. It is the security that allows them to move freely, the trust and security that lets them enter their land without worrying about mines, the balance that lets them eat food without fearing it’s stolen, that allows them to leave their house at any hour of the night without thinking that a thief is waiting for you. It is that balance, that trust in their context.” Armed Conflict Armed conflict is one of the factors most strongly related to the current MH issues in their communities: “The most difficult event, I think for everyone in Zambrano, was the armed conflict, where we suddenly had to live through a war that wasn’t ours, where there was family disintegration, deaths, selective killings, homicides, massacres, displacement, forced disappearances, and many other situations, fear and terror that took over the municipalities.” Each one of these victimizing events had individual psychological impacts that are still present in the ones who experienced them. However, a widespread effect that was felt by every member of the Montes de María community, even if they weren’t direct victims of the armed groups, was the fragmentation of the social ties and the loss of trust in others. This is greatly contrasted with the environment that existed before the armed conflict, described as a free, peaceful, united and supportive community, where the resources were shared, and nothing was lacking: “Even though my family was one of the poorest in the town, we lived in peace, because for us, peace was living freely in our municipalities and having just the minimum, and our territory was a paradise.” As a result, an entire generation has been affected, which in turn creates an intergenerational effect, related to the continuation and normalization of violence as a part of the culture, the rise in family violence cases in the region and other social issues such as drug addiction and prostitution. There was also a constant reminder by the participants that this violence has yet to cease in the region, as many armed groups have returned, bringing back fears, worries, and restrictions that were common during the worst periods of the armed conflict. This fear and insecurity are experienced especially by the leaders, who risk their lives while working for the rights of their communities, which in turn affects their well-being. State Abandonment There is a noticeable lack of action from the public forces, which enables the continuation of problems such as drug use; this inaction is also reflected in the negligence towards infrastructure in sectors like education, healthcare, road systems, and adequate housing, which hinders access to basic needs such as electricity and water. The state’s abandonment is particularly evident among victims of the armed conflict, as the reparations plans and the restoration of their rights, including land restitution, have not been fully implemented: "(In my family) I have two direct victims of armed conflict, and I haven’t been compensated, five or six years ago, they sent me a document saying that I was in the process of being compensated.” There is also a perceived lack of commitment from institutions and their officials due to the absence of continuous actions or failure to meet their commitments to the territory, which hinders the development of the necessary trust to report victimizing events. This is related to a belief that the government is not going to be able to protect and guarantee the communities’ safety, which creates a constant state of fear. Another reason to mistrust the institutions is related to corruption in the territory. The community perceives a possible association between the outlaw groups with government entities, which is why there is a perception that reporting any victimizing act won’t work or could even have negative consequences. Economic Issues and Lack of Opportunities Another common problem is the lack of resources, unemployment, and lack of opportunities in the region, which worsened after COVID-19. These issues are closely related to feelings of sadness, hopelessness, frustration and stress, and physical symptoms such as sleep issues, headaches, and tachycardia, often due to not seeing a way out of the situation. This particularly affects young people, who have few opportunities for higher education or employment to generate income, leading to unclear life goals, many dropping out from school or having to move to other parts of the country to search for those opportunities. It is also related to young people making problematic decisions such as drug abuse, prostitution, suicide, or joining armed groups that offer a higher income than they could earn legally: “Young people in our territories, when they leave school, don’t even have the opportunity to enter a university. Most of them end up staying there, working as motorbike taxi drivers because there are no companies, no job opportunities, and no way to generate income. A young person who finishes high school doesn’t have the means to go to a university, even in the municipality or the departmental center, because there is no work available to provide the economic resources needed.” Additionally, this problem extends to adults who find a lack of resources to support and develop projects, associations, and organizations working in the territory. There is also a lack of guarantees for farmers, who are forced to sell their lands and products at lower prices, leading to economic hardship and constant worry and stress. Barriers to Access Mental Health Services There are severe barriers to access MH services for the inhabitants of the region. The leaders recognize that the impacts of armed conflict on their MH should have been addressed soon after the victimizing events, and the fact that in many cases this didn’t happen has worsened the MH outcomes: “From us leaders, who were not attended to in time and are now the result of almost everything that happens in Montes de María, you can imagine the survivors of sexual violence. Some women have not even received a single psychosocial consultation, these women have given birth, and the aftermath they speak of is a sequel (...). We have survived and have built barriers; today we are leaders, but we have issues that were not addressed and are still not being addressed.” As in the network analysis, psychosocial care only showed secondary associations with MH compared to more central nodes. Some participants had received psychosocial support from government programs like PAPSIVI, however, these programs have been highly criticized by the communities, with many people having negative experiences, as on many occasions, they report the support they are given worsens the wounds that the conflict has left or creates new wounds. This is related to multiple problems identified with the services such as a focus on achieving goals and metrics, rather than offering a high-quality attention, an insufficient number of sessions, infrequent attention, unfinished processes and only implementing group interventions, offering few possibilities of having individual interventions when needed. Besides the programs, other of the main barriers to ensure MH are the non-existence, inadequate functioning, and/or lack of awareness of MH care pathways, which are even less clear in the rural areas, where people must travel extensive distances to access any services. There are also public policies that are not being correctly implemented or are insufficient to deal with all the MH struggles of the community. All these barriers have made community members less likely to seek psychological support. When they are finally able to access MH services, they frequently find poorly trained providers, who sometimes lack sensibility and are likely to make more harmful actions out of unfamiliarity with the population, the issues they are experiencing, and unawareness of their specific needs. Social Capital Consistent with the findings from the quantitative component regarding factors related to social support and sense of community, the qualitative component revealed that despite all the victimizing events, several community members have found the strength to move forward and have organized, creating community initiatives to recover what was lost, such as forming community action boards, sports teams, youth groups, and bringing back artistic and cultural practices. This has allowed the communities to integrate and restore relationships that were broken during the conflict, promoting broader support networks and rebuilding the social fabric. It has also made it possible to heal the distrust instilled by armed groups in the territories, and restore the sense of community which are elements of social capital. These spaces were also recognized as a protective factor for MH and social challenges that are common in the region, such as substance use disorders, mood and anxiety problems, and youth crime. “That has been bringing us all together, young people and adults who previously didn’t have the opportunity to have a space to share and connect. We had never done it before, but through the processes that have been carried out in our community and territory, we have achieved it. This has allowed us to integrate as individuals and gradually rebuild our social fabric. It is still somewhat lost, but little by little, we have been restoring it, and we now have more opportunities to come together and engage in dialogue.” “These community processes have been helping us in all of this, and through that, we, the young people, also had the opportunity to see another way of living” This progress was hindered by the social isolation measures imposed due to COVID-19, which limited social interactions, community gathering spaces and traditional practices in the region, such as mourning rituals and ancestral practices of indigenous and afro-descendant communities. This made it harder to cope with the emotional challenges of the pandemic, as community spaces and interactions were identified within the community as crucial in these processes. Regardless of the various social determinants that affect the MH of Montes de María’s communities, the community leaders are making constant efforts to fight for the rights of their people and secure better opportunities and resources for them. This advocacy has led to improvements such as road and infrastructure maintenance and expanded access to essential services like water and electricity. They are also advocating for reparation from the State for the violence they were exposed to, for the reduction of the violence that is still present and for access to quality healthcare and MH services within the community. These resistance initiatives have reinforced forms of social support at a community level, such as trust, mutual support, civic participation and engagement. They have also had positive effects on the leaders’ MH and sense of community, as many of them find great satisfaction in knowing they are making a positive impact in their communities. This sense of accomplishment strengthens their collective belief in their ability to create change and motivates them to continue their efforts to achieve these goals. “I feel happy, I feel really happy right now because the truth is, I’m helping my community. Very happy, because when you help the community, you feel happy, especially with everything that happened in my town, the violence, everything that went on, but here we are, my community is moving forward.” For over six decades, the armed conflict has profoundly marked the lives of Colombia’s population, particularly those residing in rural areas that serve as strategic corridors for armed groups and criminal structures. The various forms of violence to which nearly 9,737,008 individuals have been subjected to, have perpetuated structural violence, social injustices, and economic inequalities (Unidad para las Víctimas, 2024). These factors translate into limited access to healthcare, education, employment, and a fulfilling life, manifesting as harm, deprivation, and inequities that, as SDH, affect the MH of individuals, groups, and populations (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social, 2022). Numerous studies in Colombia address this issue through the application of quantitative instruments that identify symptoms, problems, and disorders (López-López et al., 2022), focusing predominantly on the individual level and thus lacking sufficient contextual consideration (Ortegón et al., 2022). Acknowledging the necessity of understanding MH as a socially determined phenomenon (WHO & Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2014) requires an approach extending beyond individual-level diagnosis of problems. Therefore, this project adopted a mixed-methods study grounded in CBPR, engaging in dialogue with communities to identify the social determinants of their MH. The aim was to translate this contextualized relevant understanding into psychosocial interventions that align with the needs and potential of the communities of Montes de María. The integration of the three central categories of analysis—MH, armed conflict, and SDH—constitutes a significant contribution to the research on the effects of armed conflict on MH. This approach is innovative in its explicit application of SDH to MH through a mixed-methods study, wherein quantitative and qualitative findings mutually reinforce each other, thus facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. The evidence indicates that the impacts of armed conflict on MH are extensive (Moreno-Chaparro et al., 2022; Østergaard et al., 2023; Piñeros-Ortíz et al., 2024), and they were further accentuated by COVID-19 (Gómez-Restrepo et al., 2023; Moya et al., 2021). Colombia exhibits significant indicators of MH issues within the general population (León-Giraldo et al., 2021), which arise within the context of the social and economic inequities and injustices affecting a substantial segment of the population. Within this framework, the significant adverse impacts on MH attributable to the armed conflict have been documented in previous research (Chaskel et al., 2015), as well as the specific impacts on population groups that highlight the role of socioeconomic status and social class, gender, ethnicity, education, occupation, social cohesion and capital, and access to quality healthcare services (Bezo et al., 2012). The socioeconomic status in Montes de María is characterized by poverty and precariousness. The lack of access to education and employment restricts their developmental prospects and renders them highly vulnerable to social injustices. The association between low income and unemployment with adverse MH outcomes has been established (Blackwell et al., 2023), this situation is further aggravated by the armed conflict which impacts rural inhabitants and indigenous communities (Ruiz et al., 2019). These results align with the arguments that emphasize the intricate intersection of historical legacies of violence and resistance within the region (Abitbol, 2022). 38% of the participants had symptoms of depression, 37.3% had symptoms of anxiety, and 18% had symptoms of stress, which is consistent with previous studies (Moreno-Chaparro et al., 2022; Moreno-Murcia et al., 2021). Younger participants exhibited higher levels of anxiety and stress. Young leaders indicated that, despite not having directly experienced victimizing events, they have faced adverse effects on their MH, which is consistent with prior research involving children and adolescents (Hewitt et al., 2014; Marroquín et al., 2020). This may be related to the lack of educational and employment opportunities, which leads young individuals to experience the effects of social inequities that coexist with armed conflict (Alarcón-Vásquez et al., 2020), structural needs in response to which social support and sense of community emerged as protective factors. The Afro-Colombian and LGBTIQ+ participants showed higher levels of depression, which may be related to the fact that they have been differentially affected by the armed conflict in Colombia, as armed groups often targeted individuals based on their sexual orientation, ethnicity or gender identity (Asociación Internacional de Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales, Trans e Intersex [ILGA World] & Colombia Diversa, 2022; Colombia Diversa, 2017). This violence was related to the rejection of identities perceived as different, resulting in sexual violence, humiliation, stigma and harassment. In addition to the effects of armed conflict, the LGBTIQ+ population generally tend to have higher rates of negative MH outcomes (Henderson et al., 2022; Lozano-Verduzco et al., 2024). The quantitative results revealed significant associations between group membership and emotional connection for peasants and indigenous people. These findings are consistent with previous studies indicating that social support mitigates the negative effects of discrimination in MH within this population (Cabral & Pinto, 2023; Henry et al., 2021). In this study, no significant differences were evidenced when comparing MH of men and women, which is relevant as it is common for MH studies to address sex variables with a predominant focus on women (Echeverry-López, 2024; Ramos et al., 2020; Zamora-Moncayo et al., 2021). There was a significant presence of female leaders who, daily, attend to the MH needs of their communities in the absence of trained professionals. Additionally, the involvement of male leaders throughout the study is noteworthy. Their participation transcended the cultural role of women as primary caregivers and facilitated an initial exploration of their own MH challenges. Their specific MH needs are reflected in the quantitative analyses, where social support and sense of community could be considered protective factors. Regarding social capital, it was found that most respondents of the quantitative survey reported social support levels above the average and a strong sense of community. This suggests that despite the fractures in social fabric caused by victimizing events, the efforts made to restore community relationships have had positive effects in the region. These effects are particularly evident in the qualitative data, when talking about cultural and artistic practices that have contributed to the development of social support networks and have strengthened the sense of community, which aligns with previous research (González-Arango et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2020). The participants of the qualitative component also described a strengthening of social capital related to their leadership roles and participation in community initiatives aimed at defending their rights. The aforementioned factors emerge as protective elements within the region, given the identified negative associations with MH issues, which aligns with other studies that have identified social capital as a predictor of MH (Bezo et al., 2012). Social capital is a multi-dimensional construct that has been described as the interaction between individuals in social associations or networks that generates cooperation and trust required for the realization of common goals (Bezo, 2012). The diverse manifestations of victimization attributable to the armed conflict have had profound effects on MH that coexist with other forms of daily violence reported by the participants, such as gender-based violence and substance abuse. Experiencing continuous violence throughout one’s life is associated with significant MH disorders and an increased likelihood of perpetrating violence toward others (Scott-Storey et al., 2024). The findings are linked to the cycle of violence identified by the participants as a direct consequence of armed conflict. Additionally, it was observed that individuals who had engaged in violent behavior encountered challenges related to employment and limited income (Scott-Storey et al., 2024). Consistent with this study, substance abuse has previously been recognized as one of the most prevalent issues among populations impacted by armed conflict (Castaño et al., 2018). This issue is notably problematic among young people and is exacerbated by the region’s geographical location and the resurgence of armed groups. Studies have highlighted that in Colombia there is a significant disparity in access to MH services. This inequity is particularly pronounced among populations affected by armed conflict (Bernal et al., 2024). Regarding psychosocial care, the leaders indicated that the programs and policies implemented thus far have been insufficient to address the community’s MH needs and identified multiple barriers to accessing these services, which have also been identified by healthcare personnel and administrative staff that are involved in the MH attention for this population (Rubio-León et al., 2025). These findings underscore the challenges in building peace in Colombia concerning the SDGs (Oswald et al., 2024), this aligns with the WHO’s call to strengthen the healthcare response to MH needs (WHO, 2022). In response to the state's abandonment, which has led to multiple structural issues in the region, the community leaders have organized and developed self-care practices that have had positive impacts in their well-being and in the peacebuilding process (García-Padilla et al., 2025). In addition to restoring community relations, these practices have also allowed for continuous mobilization to advocate for their rights and seek opportunities to improve their living conditions. As a result, the region has seen tangible improvements in their living conditions, including the acquisition of resources, productive opportunities and increased access to basic needs. These results align with previous research of marginalized and victimized communities that have developed resistance and visibility processes that, in turn, have positive impacts on MH, as well as personal and social well-being (Arias, 2019; Hernández-Holguín, 2022; Jojoa et al., 2019; Martínez et al., 2020). Considering the SDMH framework (WHO & Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian et al., 2014), it is crucial that local initiatives addressing those determinants are supported and complemented by institutional and governmental level efforts to maximize their impact. This study has significant implications for the training and practice of MH care in these regions. It is essential to address the specific contextual needs and to understand how the intricate interplay of SDH influences MH outcomes, in order to ensure that psychosocial interventions developed in the region are contextually appropriate and have a meaningful impact in the communities (Perera et al., 2020; Sheperis et al., 2023). For psychosocial interventions in these contexts, it is imperative to adopt a multidimensional perspective when working with populations immersed in conflict and peace dynamics. (López-López, 2020; López-López & Taylor, 2021). Limitations This study significantly contributes to understanding the social determinants of MH in communities affected by armed conflict, using a pioneering mixed-methods approach in the Montes de María region. The primary strength of the study was the establishment of trust-based relationships with the leaders, enabling a comprehensive understanding of MH within the specific contexts of Montes de María. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. Due to difficulties in accessing the population, the sample size limits the generalizability of the results to other similar contexts. Nonetheless, the qualitative component includes a larger participation compared to prior studies, and the overall results align with findings from similar previous studies, strengthening the findings’ validity. Additionally, since the study was primarily conducted with community leaders, the qualitative data may have been influenced by their leadership context, which was identified as a protective factor for MH. To mitigate this, leaders were encouraged to focus on collective issues, and the quantitative data collection included the general population. Among the limitations of this study, it should be noted that the data were derived from a cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inferences or temporal predictions. Although the network analysis with EBICglasso allows for estimating partial associations while simultaneously controlling for all variables and reduces the likelihood of spurious links, it does not constitute a path model or a multilevel analysis. Consequently, it does not capture potential hierarchical effects or subgroup differences. This methodology was chosen for its suitability to the exploratory objectives and its ability to parsimoniously represent the structure of interrelations among sociodemographic, psychosocial, and MH determinants. Future studies with predictive or longitudinal aims should incorporate structural or multilevel models to complement and extend the present findings. The findings of this research reveal a complex situation in Montes de María, characterized by profound socioeconomic and demographic inequalities. Participants were rural, Afro-Colombian, indigenous and farmers victims of the armed conflict violent dynamics, most of them having low incomes and limited educational opportunities, conditions that perpetuate social and economic exclusion. All, in a context which still denounces the presence of armed groups, an absence or ineffective responses from state, and significant barriers to access quality MH services. The participants revealed significant mental health needs in Montes de María; however, they also demonstrated a strong sense of community and social support, which have become essential pillars for the recovery and psychological well-being of these communities in the absence of adequate psychosocial care. This research provides compelling understanding of the inherent relations between SDH and MH in communities affected by armed conflict, highlighting the importance of considering these determinants when designing psychosocial interventions for these types of populations. It also emphasizes the urgent need for a complex and multidimensional comprehension of MH and peace related processes, in which future research and policies directed to MH have to be thought considering the socioeconomic issues in the municipalities, thereby ensuring a sustainable recovery and development of the populations. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. aWe confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us. aThe authors LC and JR participated in the project as part of the Young Researchers and Innovators Call (Number 209) as part of the 2021 economic reactivation of MinCiencias. The funder had no role in the interpretation of data or views presented in this article. Acknowledgements We express our gratitude to Montes de María communities with whom we co-constructed this project for four years. We also acknowledge Luis Manuel Silva for his revision and suggestions for improving the article. Cite this article as: Rubio-León, D. C., Cano-Sierra, L., Reyes-Rivera, M-J., Abitbol, P., García-Padilla, D., Forero-García, S. L., & López-López, W. (2026). Social determinants of mental health in armed conflict-affected municipalities of Colombia. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260809. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a1 Funding This manuscript is part of the project “Participatory design of a psychosocial mental health care model in the communities of Montes de María in the framework of the COVID-19 health emergency", funded by the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation of Colombia (MinCiencias), call “Building peace, resilience and mental health: binational research call to enhance support and understanding of Colombia’s current challenges in times of pandemic – No. 884-2020”. Supplementary Information In this regard, the results were shared with participants from the Montes de María communities, healthcare providers, and policymakers, utilizing various materials developed in collaboration with the community: a) video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e-D6PNosZhk), b) formative brochures (https://miniurl.cl/0bdpmq; https://miniurl.cl/0tleda; https://miniurl.cl/gsd7rx; https://miniurl.cl/mifsru; https://miniurl.cl/oiwyjn; https://miniurl.cl/r4gnju); c) podcasts (https://soundcloud.com/facultad-psicologia-puj), d) policy briefs, e) three regional meetings, and f) an event of social appropriation of knowledge. |

Cite this article as: Rubio-León, D. C., Cano-Sierra, L., Reyes-Rivera, M., Abitbol, P., García-Padilla, D., Forero-García, S. L., & López-López, W. (2026). Social Determinants of Mental Health in Armed Conflict-affected Municipalities. Psychosocial Intervention, 35, Article e260809. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2026a1

Correspondence: lopezw@javeriana.edu.co (W. López-López).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS