Social Support and Mental Health of Young People in Residential Care: A Qualitative Study

[El apoyo social y la salud mental de los j├│venes en acogimiento residencial: estudio cualitativo]

Sofia Ferreira1, Eunice Magalhães2, and Ana Prioste3

1Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), Portugal; 2Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL), CIS-IUL, Portugal; 3HEI-LAB, Universidade Lusófona de Humanidades e Tecnologias, Lisboa, Portugal

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a12

Received 15 November 2018, Accepted 21 June 2019

Abstract

The literature suggests the positive role of social support in mental health in residential care. However, most of the studies are focused on psychopathology and fewer on well-being. Also, theoretically-oriented and multidimensional studies on social support are needed. To address these problems, a qualitative study was developed with 29 young people in residential care (76% males), aged from 12 to 19 years old. Data was collected with a semi-structured interview. Results showed young people identify meaningful sources of social support (peers, residential care, and family), considering them available and effective support providers. Social support was also identified as an enhancer of positive psychological functioning and as a buffer of psychological functioning problems. Future research should involve more systematic, multidimensional approaches, both in assessing social support and in mental health. Important implications are recognized for professionals in the justice system.

Resumen

La bibliografía indica el papel positivo del apoyo social en la salud mental en acogimiento residencial. Sin embargo, la mayoría de los estudios se centran más en la psicopatología y menos en el bienestar. Además, se necesitan estudios sobre apoyo social multidimensionales y guiados por la teoría. Para abordar estos problemas, se desarrolló un estudio cualitativo con 29 jóvenes en acogimiento residencial (76% hombres), de 12 a 19 años. Los datos se recogieron en una entrevista semiestructurada. Los resultados mostraron que los jóvenes identifican fuentes significativas de apoyo social (iguales, profesionales en acogimiento y su familia) proveedoras de apoyo disponibles y efectivas. El apoyo social también se identificó como potenciador del funcionamiento psicológico positivo y como amortiguador de los problemas de funcionamiento psicológico. Las investigaciones futuras deberían incluir enfoques más sistemáticos multifuncionales, tanto en la evaluación del apoyo social como en la salud mental. Se reconocen importantes implicaciones para los profesionales del sistema de justicia.

Palabras clave

Apoyo social, Salud mental, Acogimiento residencial, Adolescentes, VictimasKeywords

Social support, Mental health, Residential care, Young people, VictimsCite this article as: Ferreira, S., Magalhães, E., & Prioste, A. (2020). Social Support and Mental Health of Young People in Residential Care: A Qualitative Study. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 30(1), 29 - 34. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a12

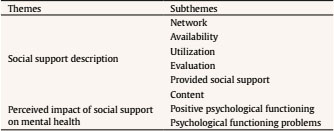

nicemagalhaes@gmail.com Correspondence: nicemagalhaes@gmail.com (E. Magalhães)Generally, social support can be conceived as “the existence or availability of people on whom we can rely, people who let us know that they care about, value, and love us.” (Sarason, Levine, Basham, & Sarason, 1983, p.127). Multiple definitions of social support have been provided in literature, a reason why Tardy (1985) proposed a five dimensional model that guide the conceptualization of social support: direction (i.e., social support can be provided and/or received), disposition (i.e., the availability of social support in terms of quantity or quality vs. the actual use of support), description/evaluation (i.e., the description and evaluation of social support, namely, as it regards to the satisfaction of the individual with the social support), content (i.e., the type of content involved in social support, namely, emotional, instrumental, informational, and appraisal), and network (i.e., the sources of support, namely, parents, teachers, neighbours, friends, professionals). Regardless of the dimension, literature has consistently suggested the positive role of social support in an individual’s mental health outcomes, including adults (Wang, Wu, & Liu, 2003) and adolescents (Demaray & Malecki, 2014). However, literature about this topic with at risk young people or in the judicial system (e.g., adolescents in residential care or unaccompanied refugees) is scarce, despite their social, psychological, and academic vulnerability (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2008; Huemer et al., 2009; Magalhães, Calheiros, & Costa, 2016). Specifically, adolescents in residential care show more emotional and behavioral problems compared to young people living in normative development contexts (e.g., Connor, Doerfler, Toscano, Volungis, & Steingard, 2004), as well as more stressful and traumatic experiences ( Franz, 2004). Actually, they have to endure with a set of cumulative risk factors through their trajectory that are particularly developmentally challenging, namely, family separation and integration into a group home as well as leaving and adapting to new circumstances of life (e.g., return to the family, a new developmental trajectory to independent life, or their integration in a new family) (Bravo & Del Valle, 2003). Likewise, unaccompanied refugee adolescents is the most vulnerable group of refugees regarding mental health outcomes, given that they show higher levels of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (Hodes, Jagdev, Chandra, & Cunniff, 2008; Huemer et al., 2009; Sierau, Schneider, Nesterko, & Glaesmer, 2018). These adolescents also deal with a number of challenges, both in the country of origin and in the host country, namely, their separation of parents, systematic evaluation procedures during the asylum process, life in the refugee camp, difficulties in access to mental health services, racism, and discrimination (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2008; Mels, Derluyn, & Broekaert, 2008). As such, an adequate social support may be helpful to these young people to deal with all these challenges and difficulties in a more effective way (Bravo & Del Valle, 2003; Soldevila, Peregrino, Oriol, & Filella, 2013). In fact, we know that it is in the face of greater stress and vulnerability that the perceived social support has an important role in the psychological functioning of young people (Degner, Henriksen, Ahonen, & Oscarsson , 2014). In the context of residential care, social support is recognized as a protective factor for mental health of children and young people (e.g., Erol, Simsek, & Münir, 2010; Martín & Dávila, 2008; Simsek, Erol, Öztop, & Münir, 2007; Soldevila et al., 2013). High levels of social support are associated with lower levels of emotional and behavioural problems (Erol et al., 2010; Simsek et al., 2007), posttraumatic stress disorder (Gearing et al., 2015), and higher subjective well-being (Dinisman, Zeira, Sulimai-Aidan, & Benbenishty, 2013). The support provided by professionals in residential settings seems to have a key role concerning the behavioural problems (Erol et al., 2010) as well as psychological, emotional, and social well-being of these children and young people (Fournier, Bridge, Kennedy, Alibhai, & Konde-Lule, 2014). Additionally, not only relationships in care are recognized by young people as being supportive but also those with relatives/family. Mothers are perceived as the source that provides the strongest emotional and instrumental support, while the remaining relatives/family members (e.g., father, siblings) are perceived as the poorest source of instrumental support (Bravo & Del Valle, 2003). Moreover, the whole family context (e.g., grandparents, siblings, father, mother) are perceived by youth as particularly important in terms of the affectivity dimension (i.e., feelings of attachment) (Bravo & Del Valle, 2003). However, results suggest an apparent contradictory evidence, with some studies proposing that young people in residential care identify elements of their biological family as important sources of support, particularly their mothers (Dinisman et al., 2013) and others revealing a small number of young people in residential care identifying the members of the family as sources of support, favouring the residential context (Fournier et al., 2014). Actually, the support from residential care elements (professionals and peers) includes different dimensions, namely, emotional, affective, and informational support (Dinisman et al., 2013; Fournier et al., 2014). Specifically, young people in residential care perceive the social support provided by their peers as very satisfactory with positive implications for their mental health outcomes. Close relationships with peers are negative predictors for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression (Gearing et al. al., 2015), and a positive predictor for subjective well-being (Dinisman et al., 2013). Specifically, emotional, instrumental, and informational support from peers significantly predicts the affective component of young people’s subjective well-being (e.g., positive and negative mood) and the cognitive component (e.g., satisfaction with life) (Dinisman et al., 2013). Furthermore, social support provided by peers is reported by young people in residential care as a coping strategy to deal with adversity (Fournier et al., 2014). Looking at literature with unaccompanied refugee adolescents, social support also emerges as an important predictor of positive mental health outcomes (Sierau et al., 2018). Specifically, literature highlights the positive role of formal support sources (e.g., caregivers, mentors, asylum center staff) in processing stressful or traumatic life experiences, enhancing positive mental health outcomes (Mels et al., 2008; Sierau et al., 2018). Formal social support (e.g., instrumental and informational) may foster adolescents’ adaptive coping strategies in the face of negative/traumatic life experiences (Sierau et al., 2018). Actually, formal network is often described as close and meaningful, providing important instrumental, informational, or emotional support (Mels et al., 2008). On the other hand, inconsistent evidence is described in informal support (e.g., from relative). If there are unaccompanied refugee adolescents who maintain contact with relatives and perceive these elements as important tangible sources of social support (Oppedal & Idsoe, 2015), on the other hand there are unaccompanied refugee adolescents who have no contact with their family (Mels et al., 2008). Finally, inconsistent results are described in peers’ social support. There are studies suggesting that unaccompanied refugee adolescents perceive high levels of peers support (Oppedal & Idsoe, 2015) and that this support buffers negative effects of stressful life events (Sierau et al., 2018). In turn, there are also studies reporting that these adolescents may experience significant difficulties in socialization with peers in the host country, with negative implications for their social integration (Mels et al., 2008). As such, all this evidence with at-risk young people suggests the importance of positive and supportive relationships for a resilient psychological functioning, as well as the ability of these young people to form positive social relationships, thereby enhancing their social competence (Fournier et al., 2014). Despite this evidence of the protective role of social support to youth’s mental health, more theoretical-oriented and multidimensional studies are needed. A multidimensional approach is needed regarding the social support conceptualization and measurement but also mental health outcomes. Actually, the majority of studies with at-risk young people (e.g., in residential care) is focused on psychopathology (Erol et al., 2010; Franz, 2004; Gearing et al., 2015; Simsek et al., 2007), with the positive functioning and optimal development being a relatively recent and unexplored research field with this population (Dinisman et al., 2013). As such, a holistic and comprehensive picture of mental health is needed, including positive and negative indicators simultaneously. Finally, an in-depth approach of young people’s meanings and experiences would be useful, through qualitative methods, to understand the role of different sources and contexts of support to their psychological functioning. Through this qualitative empirical study and from a sample of at-risk youth in residential care, we aim to explore young people’s representations and meanings of social support, based on a multidimensional, comprehensive, holistic, and theoretically-oriented approach (Tardy, 1985). In addition, we aim to assess the perceived impact of social support on their mental health outcomes in terms of psychopathology and well-being. Through this approach, this study allows us to provide an opportunity of active voice in research processes to these vulnerable youths (Emond 2003; Fournier et al., 2014). Practical implications will be identified from this study, specifically for professionals and researchers working in legal psychology with vulnerable young people (e.g., youth in residential and foster care, unaccompanied young refugees, or young people with judicial measures of internment). Participants Twenty-nine adolescents in residential care, aged from 12-19 years old (M = 14.79, SD = 1.80), and mostly males (76%) participated in this study. A set of risk factors were identified in their family, namely, divorce/separation (42%), physical abuse (42%), exposure to behaviours that severely affected their safety or emotional well-being (42%), marital violence (35%), unemployment (31%), drug abuse (24%), and psychiatric disorder (24%). These participants had been in the current residential care setting for an average of 29 months, ranging from 0 to 121 months. Considering the overall time since they entered the care system, on average they have been placed there for 56 months, ranging from 0 to 168 months. Furthermore, the majority of these adolescents is in residential care for the first time (45%). The majority of these participants has contacts with their relatives/family (45%), and for that reason the family reintegration is the more prevalent case plan (38%), followed by a plan of autonomy/independent life preparation (28%). Regarding young people’s psychological functioning, 14% of these adolescents show an emotional problem or a cognitive deficit. Instruments Socio-demographic questionnaire. This questionnaire involves data about young people and their families, such as age, school year, school failures, risk factors in the family, and also placement history in the residential care system (e.g., number of previous placements, contacts with family, case plan information). Semi-structured interview. The semi-structured interview script is organized into two thematic sections, namely focusing on the elements of social support (i.e., network, direction, disposition, content, and evaluation) (Tardy, 1985) and perceived relationship between social support and mental health. The first thematic section aimed to evaluate youth’s representations and meanings of social support, based on a multidimensional, comprehensive and theoretically guided approach (Tardy, 1985): network (e.g., “Who are the most important or close people in your life?”), direction and disposition (e.g., “Whenever you need, do you have available people who may help you?”), content (e.g., “Thinking specifically about the support of those people you were talking about, what kind of help do these people give you or do you think they can give?”), and evaluation (e.g., “How do you evaluate this help you receive?”). In the second thematic section we aimed to evaluate the perceived impact of social support on psychopathology (i.e., “When you are going through a hard event, what do you feel when these people help you?”) and well-being (i.e., “How does their help enable you to grow up as a person?”). Procedures of Data Collection and Analysis Firstly, residential care settings were contacted and their collaboration was requested. Then, meetings with professionals from these settings were held prior to data collection to clarify the main objectives of the study and the inclusion criteria of participants. After this authorization, data collection began with the informed assent provided by these adolescents. They were informed about the study objectives as well as about ethical issues, namely the voluntary nature of participation, the right to keep away at any moment, the guarantee of anonymity, and confidentiality of data. For each interview, the same structure and sequence of thematic blocks and questions were followed (as previously described in the Instruments section). These interviews were performed in a private setting (e.g., meeting room, toy room), only with the presence of the interviewer and the adolescent. The total length of the interviews ranged from 6 to 40 minutes. Previously to these interviews, a professional in residential care filled out a questionnaire to describe our participants. Interviews were transcribed and data analysed using ATLAS.ti v.7 software. They were analysed using thematic analysis, which involves the identification and analysis of patterns (themes) in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). According to the authors, the themes can be identified in two ways: inductively or deductively. In this study, a deductive-inductive analysis was adopted, which consists of an approach guided by the theoretical interest of research, but considering also those inputs from participants to name and define themes. Thus, the steps proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006) were adopted in the analysis process: (1) familiarising with the data through repeated reading, which enabled the initial exploration of patterns and meanings; (2) generation of initial codes from the data – relevant semantic characteristics were coded; (3) exploration of themes – a classification of different codes into potential themes was set up. In this phase a table was created in order to obtain a visual representation of the codes, which facilitated the identification of relations between codes/themes; (4) revision of the themes – a review of the relationship between the themes and the data collected was made, in order to ensure that the thematic map and the data set were adequate; (5) definition and naming of the themes. Citations from the interviews that were considered illustrative and representative were selected as examples for each theme/sub-theme. Only the themes reported by at least 20% of the participants will be presented, the number and percentage of participants who reported the respective category/theme being presented along the results. The results obtained in the current study suggest two main subjects, consonant with the structure of the interview script and the theoretical approach underlying the study: 1) social support description and 2) perceived impact of social support on mental health (Table 1). Social Support Description In the context of the first subject, six sub-themes emerged from young people’s speech, once again consistent whit the structured of the script and theoretically oriented: network, availability, utilization, evaluation, provided social support, and content. Network. The majority of the young people identify informal support sources (n = 27, 93%), including family, friends, friends’ family and partner, considering them as close, significant or important people. In turn, formal support is mentioned by approximately half of the participants (n = 14, 48%), with reference, specifically, to the residential care professionals (e.g., educators) and teachers. Availability. Most young people recognize that their sources of social support are available to provide support when they are in need (n = 28, 97%): “I feel like I’m not that lonely and that there are people who can help me, and things like that, and I know that even though I don’t want to tell something, if I ever decide to one day, I know that they will listen to me. (...) Even if we had a fight or something, I know that if anything happens to me, I can always count on them.” (Female, 13 years old). Utilization. The majority of young people refer that they effectively use/receive the help provided by their network (n = 27, 93%): “When something happens (...) and I don’t need to talk, I don’t say ‘Micaela something happened to me, I need your help’ I don’t... I don’t have to say that because she knows that I’m sad and helps even without me asking. But my best friend... When... We... We fight a lot, I mean constantly. We are always fighting so when she sees that I’m sad, I don’t have to say anything, she just asks and says ‘I know that you are sad, now you’re going to tell me what happened’, I tell her and she immediately helps me.” (Female, 13 years old). Nevertheless, some of the participants (n = 9, 31%) suggest not receiving/using available support: ‘They tried to talk to me, but I never wanted to’.” (Male, 16 years old). Evaluation. The evaluation provided by our participants on the received social support is predominantly positive (n = 29, 100%). Specifically, young people are globally satisfied: “It is very good, starting with their effort, which is a great effort to understand us, even when we don’t behave so nicely, they can understand us and help us and we end up turning things around... and also understanding that our attitude was bad, but those people are always there for us. (...) To me, I think that the way they help is good and if they continued it is very good because they will be able to make several children happy.” (Male, 14 years old) – and grateful for the received social support: “There are certain things that sometimes makes me think that I did not deserve the help that they sometimes give me, but there are others that I think that I really needed this help and they are helping me. (...) [Feels] very [grateful].” (Female, 16 years old). However, it is also noted that some of the young people recognize less positive aspects of the received social support (n = 7, 24%), and they are unsatisfied with the received support: “I have also been given bad advices and I created expectations and then I was disappointed. (...) I even stopped talking to my sister.” (Female, 14 years old), considering it irrelevant/not very effective: “There are things they do that I don’t like, but they say that they are helping me, so... Ah... Like, I do not enjoy people messing with my stuff. And they’re going to rearrange it, ok, it’s tidy, but it’s gotta be my way, like I’m used to it, but they just do it and say “oh I’m helping you” (...) but I like the way that it is, but they mess with it, then I stop caring anymore, I let them do it, they say they’re helping me but I don’t think so, but that’s it.” (Male, 15 years old), or identifying additional support needs: “It is always good to receive more and I would like to have even more. (...) I would like to have more (...) advices because the advices give me strength.” (Male, 15 years old). Content. Different types of social support were identified by young people in residential care. Informational support, which essentially includes the advice and guidance received from different sources of support, was the one that most often emerged (n = 29, 100%): “The help they give me is a help that I can use in my present and will affect my future. Give me some good advices, tell me the ways where I can go to have a good future (...). Ahh, for example at this stage, I am moving on to the 7th grade, I will take a professional course and they are advising me on the courses where I can have more professional opportunities.” (Male, 14 years old). In addition, emotional support was also identified by our participants, which involves aspects such as trust, empathy, love, willingness to listen and providing feelings of acceptance when the young person is experiencing difficulties (n = 26, 90%): “My sister helped me once. My father passed away. She was talking to me. Telling me to stay calm, not to cry anymore and to think he’s in a better place.” (Male, 12 years old). Finally, instrumental support, which refers to support of a pragmatic nature (n = 23, 79%), was also recognized in this study: “At work. I was looking for a job in my specialty, which is catering, kitchen. (...) They even helped on my curriculum.” (Male, 18 years old). Furthermore, we found that not only do young people identify different contents (emotional, instrumental, and informational) but also they consider that different types of support may be provided/received according to the source (n = 17, 59%): “It’s different kinds of help, because my sister understands more what I feel. Not that my best friend doesn’t understand (...) but sometimes she can’t be there when I really need it. (...) And my sister unchecks everything she has and focuses on me. (...) She is more available. (...) It depends on the subject. There are subjects my sister does not understand. She even tries to help but there are things that (...) confuse her. With my friend, since she is the same age as me, maybe she has had similar situations, she understands me a little better. (...) When I do something wrong or when I try to demonstrate it in a different way (...) and my sister says ‘why didn’t you do it like that’ and my best friend says ‘ah I already went through this, I know what it is’.” (Female, 13 years old). Specifically, when we analyse in detail the content identified by the young people according to the sources of support, we find that professionals in residential care are considered the source that provides the most informational (n = 20, 69%) and instrumental support to young people (n = 14, 48%), followed by the family (n = 17, 59%; n = 11, 38%) and friends (n = 6, 21%; n = 3, 10%). In turn, regarding the emotional support, the family was mostly identified (n = 16, 55%), followed by the professionals in residential care (n = 15, 52%) and friends (n = 9, 31%). Provided social support. Most young people consider them-selves be an available source of social support to significant others (n = 28, 97%): “My mother. My mother knows I help. My whole family knows. I say it almost every day ‘Mom you know that I am here every day to help’.” (Male, 14 years old), suggesting that they consider the provided support to be affective for people considered significant (n = 20, 69%): “I helped, because the next day she was feeling better, right? She was happy, she wasn’t sad.” (Female, 19 years old). Perceived Impact of Social Support on Mental Health Positive psychological functioning. All participants recognize the positive role of social support in terms of their positive psychological functioning (n = 29, 100%), namely, in terms of perceived self-efficacy: “I believe in myself more than before. I used to be afraid to talk to firefighters if I ever had to. That day I spoke to them and I couldn’t believe it was me, I did manoeuvres, I did everything, I couldn’t believe it was me.” (Female, 14 years old), in acquiring new skills: “I already see things differently. (...) It was thanks to these people and to a certain extent to myself. I had to grow a lot mentally. (...) It has helped me a lot, when it comes to school, experiences at home (...), and in terms of preparing for an autonomous life.” (Male, 17 years old), as well as in terms of the participants’ well-being and quality of life: “Both the warning and the advices, to me it’s the same thing, because the things they tell me make me feel good. I feel sad about being here but I feel good because it’s a good thing they’re doing for me.” (Male, 15 years old). Psychological functioning problems. Most young people also recognize the positive impact of social support on minimizing psychological problems (n = 26, 90%): “I was also a user of this [drug addict] because I also smoked drugs and had my issues and my own ways of solving them, but now because of some friends I quit drugs and the group home helped me and everything.” (Male, 18 years old), recognizing the negative impact of the absence of social support on their mental health: “Good, only sometimes they are not here and sometimes when they do not answer I feel really bad.” (Female, 14 years old). This empirical study aimed to provide an in-depth understanding of personal meanings and experiences of young people in residential care about social support, from a multidimensional, comprehensive, and theoretical-oriented approach (Tardy, 1985). Likewise, we aimed to evaluate the perceived impact of social support on youths’ psychopathology and well-being. Considering the research problems, we aimed to provide additional evidence to the need for multidimensional approaches to the evaluation of both social support and psychological functioning. The results revealed that young people’s social network is not restricted to the group home, opposing some evidence previously reported (Franz, 2004), but consistent with other evidence that reinforced the importance given to informal supportive relationships, particularly in the context of family (Dinisman et al., 2013) and peers (Bravo & del Valle, 2003; Parente, Mendes, Teixeira, & Martins, 2014). In fact, the sources of support identified by youth in care could emerge either in the family or in the residential context (Bravo & del Valle, 2003; Martín & Dávila, 2008; Siqueira & Dell’Aglio, 2010; Siqueira, Tubino, Schwarz, & Dell’Aglio, 2009). Consistently with previous evidence, in this study, the residential care setting is portrayed as a context of major importance for young people, who identified professionals in care as significant sources of social support (Fournier et al., 2014; Gearing et al., 2015). Specifically, and reinforcing previous evidence (e.g., Bravo & del Valle, 2003; Martín & Dávila, 2008), residential care professionals and family members are considered to be the sources that provide the most instrumental, informational, and emotional support. In addition, young people were generally satisfied with the social support, reporting a predominantly positive evaluation in this study. These results are consistent with other studies suggesting that, despite the perceived lower availability of social support of young people in residential care (compared to young people in normative development contexts), generally perceive a satisfying social support (Franz, 2004). Furthermore, most young people in this study recognize that their sources of social support are available whenever they need support. Considering the perceived impact of social support on psychopathology, young people recognize the positive impact of social support on minimizing problems of psychological functioning, which reinforces the results found previously in quantitative studies (e.g., Erol et al., 2010; Gearing et al., 2006; Simsek et al., 2007). In fact, previous studies reveal the important role of social support in mental health, with high levels of social support being associated with lower levels of emotional and behavioural problems. In this sense, social support can be a protective factor against psychological problems of young people in residential care (Erol et al., 2010; Simsek et al., 2007). An important and innovative result of this study is related to the perceived impact of social support on well-being. According to our participants, higher levels of social support contribute to a positive psychological functioning, namely, in terms of perceived self-efficacy, acquisition of new skills (e.g., personal and social), and well-being and quality of life. Therefore, the important role of social support is seen not only as a protective factor in relation to psychological problems, but also as an enhancer of personal growth and optimal functioning. This is theoretically plausible given that supportive relationships may increase individual self-esteem and may be associated with the adoption of adaptive coping strategies, as well as with the acceptance of individual feelings and emotions (Wills & Shinar, 2000). Likewise, the majority of young people considered receiving/using their network’s support, highlighting how their sources of support effectively help them when they need it the most. In addition, we also found that young people consider themselves as an available source of social support to significant others. This reflects the active role of young people as sources of social support, considering that the support they provide may be helpful for people they consider to be important. These results might indicate the well-described benefits of social support in mental health (e.g., increased self-esteem, evaluation of life events as less threatening; Wills & Shinar, 2000). Also, it reinforces the evidence that belonging to a group, where the individual can give and receive support, increases his/her personal control (e.g., increased confidence, personal convictions in the ability to intervene and influence decisions in his life) (Ornelas, 2008). In sum, this study seems to contribute with new insights on young people’s meanings about supportive relationships, by providing a multidimensional and comprehensive approach of this phenomenon in care and considering a more complete picture of mental health indicators (psychopathology and well-being). However, it is also important to identify some limitations, namely, in terms of sample characteristics. Even though the number of young people who participated in this study was satisfactory for a qualitative approach, it would have been important to have a more gender-balanced sample, considering the greater preponderance of males. Despite these limitations, the innovative results from this study enable us to identify a set of implications for professional practices and research. Considering that young people identified both formal (e.g., educators) and informal sources of support (e.g., family, friends), the psychosocial intervention with them in residential care should consider the role of different elements of support (Degner, Henriksen, & Oscarsson, 2010). Therefore, given the positive role of established relationships with the family, residential care professionals, and peers, it is important to invest in these relationships during the placement in care. This is important considering the need to maintain close and adequate relationships with the biological family (particularly when there is the possibility of family reintegration), as well as of providing opportunities for supportive relationships with other adult caregivers (e.g., in the residential context) and peers. In fact, Bravo and Del Valle (2003) emphasize the need to involve families throughout the whole placement process in order to achieve a successful family reintegration. In addition, the identification of significant sources of social support in the residential context highlights the importance of a therapeutic based approach in the relationships in care. A therapeutic model of professional relationships in care suggests that the ability of young people to understand their problems and feelings depends on the existence of trustworthy professionals who understand their behaviours and who are able to return them the causes of misconduct, enabling their behavioural and emotional change (Casa Pia, 2011). Actually, the emotional support from caretakers (e.g., the ability to listen, to support, and to be emotionally linked with youths) is crucial to understand and respond to the emotional needs of young people in residential care. Considering the innovative results on social support and mental health outcomes, particularly, the role of supportive relationships by enhancing the young people’s positive psychological functioning, a set of practical implications could be identified. The intervention should not be restricted to solving the young people’s problems of psychological functioning, but also to promote their optimal functioning and quality of life. It is important to promote youth’s well-being by emphasizing their skills, improving their quality of life and strengthening their social support network (Ornelas, 2008). While this study included young people in residential care, our results may inform also professionals’ practice with different vulnerable groups, such as unaccompanied adolescent refugees and young people facing juvenile justice. It is important to strengthen the social support networks of unaccompanied refugee adolescents and to build relationships of trust (Sierau et al., 2018), namely with peers from the host country (Mels et al., 2008; Oppedal & Idsoe, 2015). Considering the emotional and social needs of unaccompanied refugee adolescents, psychosocial intervention should consider both legal and psychological issues (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2008; Mels et al., 2008). In spite of being viewed merely as refugees (legal perspective), these adolescents may be also viewed as young people in need and their mental health needs must be addressed (Derluyn & Broekaert, 2008; Huemer et al., 2009). Professionals working with unaccompanied refugee adolescents must be aware of their critical challenges in order to be able to evaluate their needs of formal social support (e.g., referral to specialized mental health services (Hodes et al., 2008). Actually, these young people have basic needs but also social and emotional difficulties, which suggest the importance of specialized training for professionals in this area (Mels et al., 2008). For young people facing juvenile justice, intervention must be comprehensive (i.e., considering both individual and contextual factors, rather than an individual perspective of their problems), addressing both the triggering factors and the consequences of disruptive behavior, which may prevent social exclusion chronicity (Córcoles, de la Rosa, García, & Buendía, 2004). In addition to these practical implications, we can also identify implications for future research. Thus, if this study appears as a first exploratory approach to address the set of problems identified in the literature, it also suggests the need to develop more theoretically oriented and multidimensional studies that can overcome the problems arising from the conceptual inaccuracy on social support literature. It is also important to develop research efforts focused not only on psychopathology but also on positive functioning, given that these results suggest that the social support perceived by young people is a crucial factor in their skills acquisition and adaptive development processes. Finally, considering that this is a cross-sectional study (with no causal relationships being possible), it is necessary to develop longitudinal based studies. Conflict of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all residential settings that participated in this study and especially all youth who accepted to participate. Cite this article as: Ferreira, S., Magalhães, E., & Prioste, A. (2019). Social support and mental health of young people in residential care: A qualitative study. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 30, 29-34. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a12 |

Cite this article as: Ferreira, S., Magalhães, E., & Prioste, A. (2020). Social Support and Mental Health of Young People in Residential Care: A Qualitative Study. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 30(1), 29 - 34. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2019a12

nicemagalhaes@gmail.com Correspondence: nicemagalhaes@gmail.com (E. Magalhães)Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS