Profiles of Adolescents who Abuse their Parents: A Gender-based Analysis

[Perfiles de los adolescentes que maltratan a sus padres: un an├ílisis con perspectiva de g├ęnero]

Ana M. Martín and Helena Cortina

Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a5

Received 31 May 2022, Accepted 28 September 2022

Abstract

Adolescent-to-parent violence (APV) is still the most understudied type of domestic violence, although reports filed by victimized parents and youths serving judicial measures for this reason are increasing. The aim of this study is to assess the differential profile of boys and girls who have and have not reported APV in a community sample, following studies showing differences between both genders in initiating and maintaining offending behavior. To this end, each gender was assessed separately in relation to both variables already investigated by research on APV and variables that are relevant for other forms of violence. The sample was composed by 341 high-school students of both genders, aged between 14 to 20 years. They answered a questionnaire including scales on exposure to violence, parent-child relationships, self-concept, psychopathic traits, narcissism, and sexism. They were also asked about drug use, academic performance, family structure, and mental health diagnosis. Data analyses showed that variables that differentiate between youths who reported APV and those who did not were different for boys and girls. Results are discussed suggesting that incorporating a perspective based on gender, that considers differential experiences and psychosocial factors that lead boys and girls to APV, should contribute to designing more conclusive research and more effective interventions.

Resumen

La violencia de los adolescentes hacia sus padres (VAP) sigue siendo el tipo de violencia doméstica menos estudiado, aunque aumentan las denuncias presentadas por padres y jóvenes que cumplen medidas judiciales por este motivo. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar el perfil diferencial de chicos y chicas que o no han reconocido haber ejercido VAP en una muestra comunitaria, en la línea de los estudios que muestran diferencias entre ambos géneros en el inicio y mantenimiento de la conducta delictiva. Con este propósito se ha analizado por separado a cada género en relación tanto con variables que ya habían sido estudiadas en la investigación sobre VAP como con variables relevantes para otras formas de violencia. La muestra consta de 341 estudiantes de bachillerato de ambos sexos, en edades comprendidas entre los 14 y los 20 años. Respondieron a un cuestionario que incluía escalas sobre exposición a la violencia, relaciones paternofiliales, autoconcepto, rasgos psicopáticos, narcisismo y sexismo. También se les preguntó sobre el consumo de drogas, el rendimiento académico, la estructura familiar y el diagnóstico de salud mental. El análisis de los datos muestra que las variables que diferencian a los jóvenes que reconocían haber ejercido VAP de los que no lo hicieron son diferentes para los chicos y para las chicas. Los resultados se discuten sugiriendo que la incorporación de una perspectiva de género, que considere las experiencias diferenciales y los factores psicosociales que llevan a chicos y chicas a la VAP, podría contribuir a diseñar investigaciones más concluyentes e intervenciones más eficaces.

Palabras clave

Violencia filioparental, Diferencias de g├ęnero, Sexismo ambivalente, Autoconcepto, Exposici├│n a la violenciaKeywords

Adolescent-to-parent violence, Gender differences, Ambivalent sexism, Self-concept, Exposure to violenceCite this article as: Martín, A. M. & Cortina, H. (2023). Profiles of Adolescents who Abuse their Parents: A Gender-based Analysis. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 33(1), 135 - 145. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a5

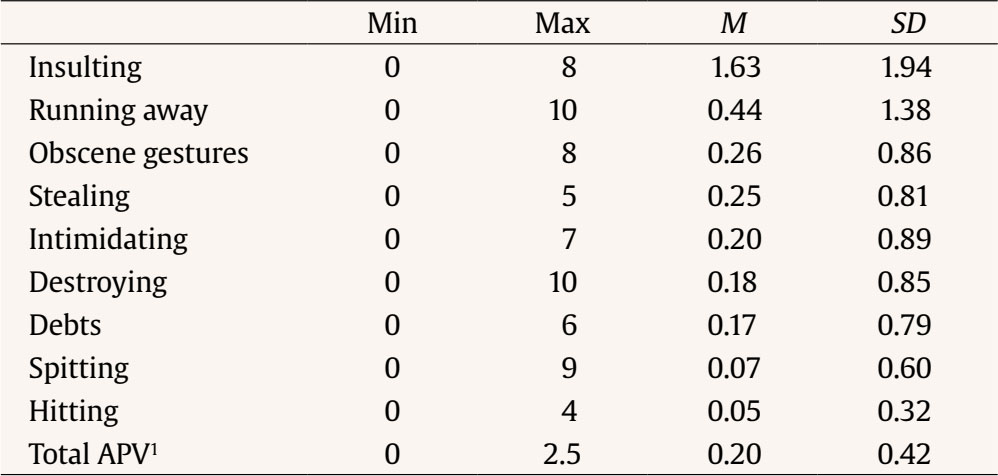

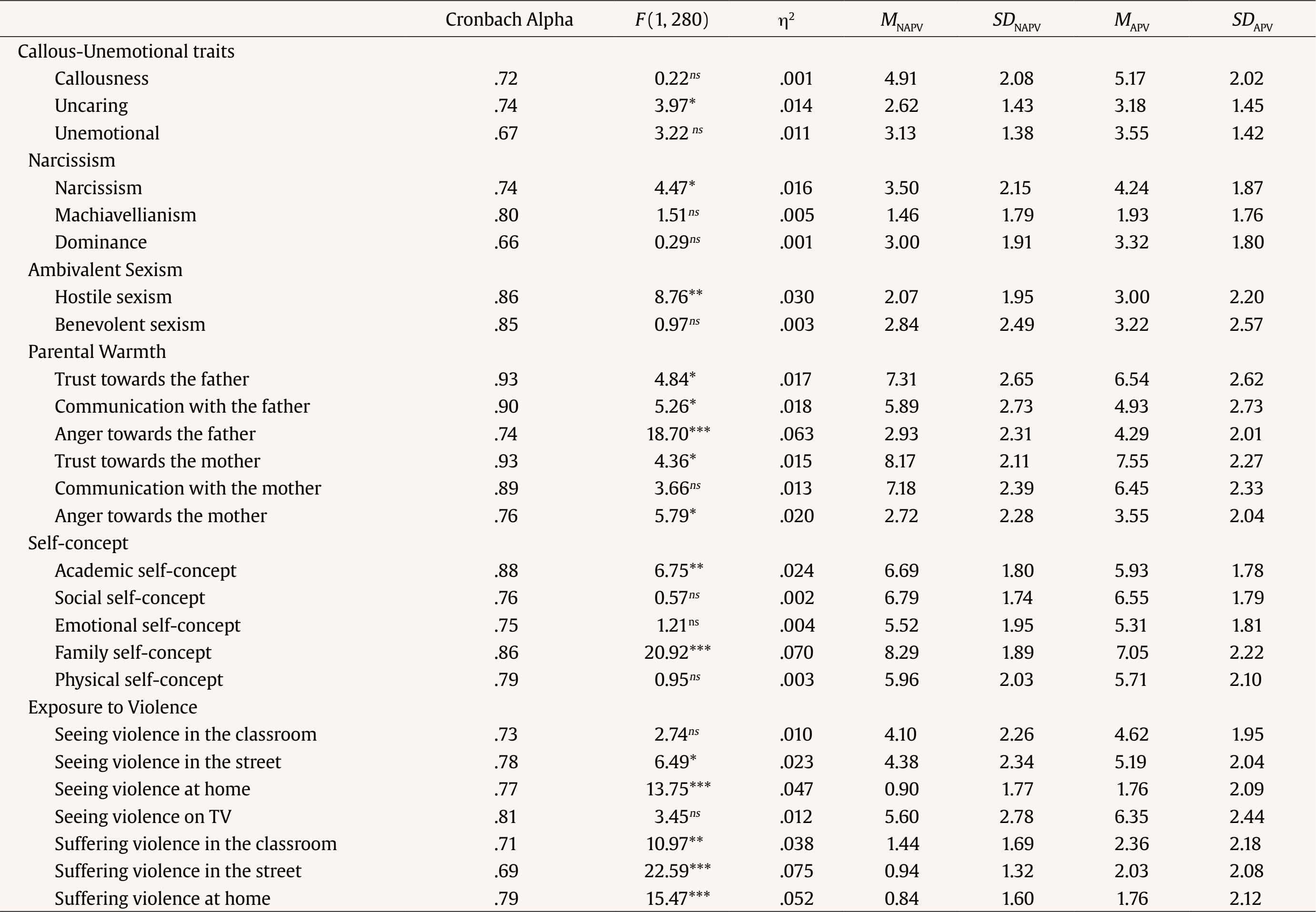

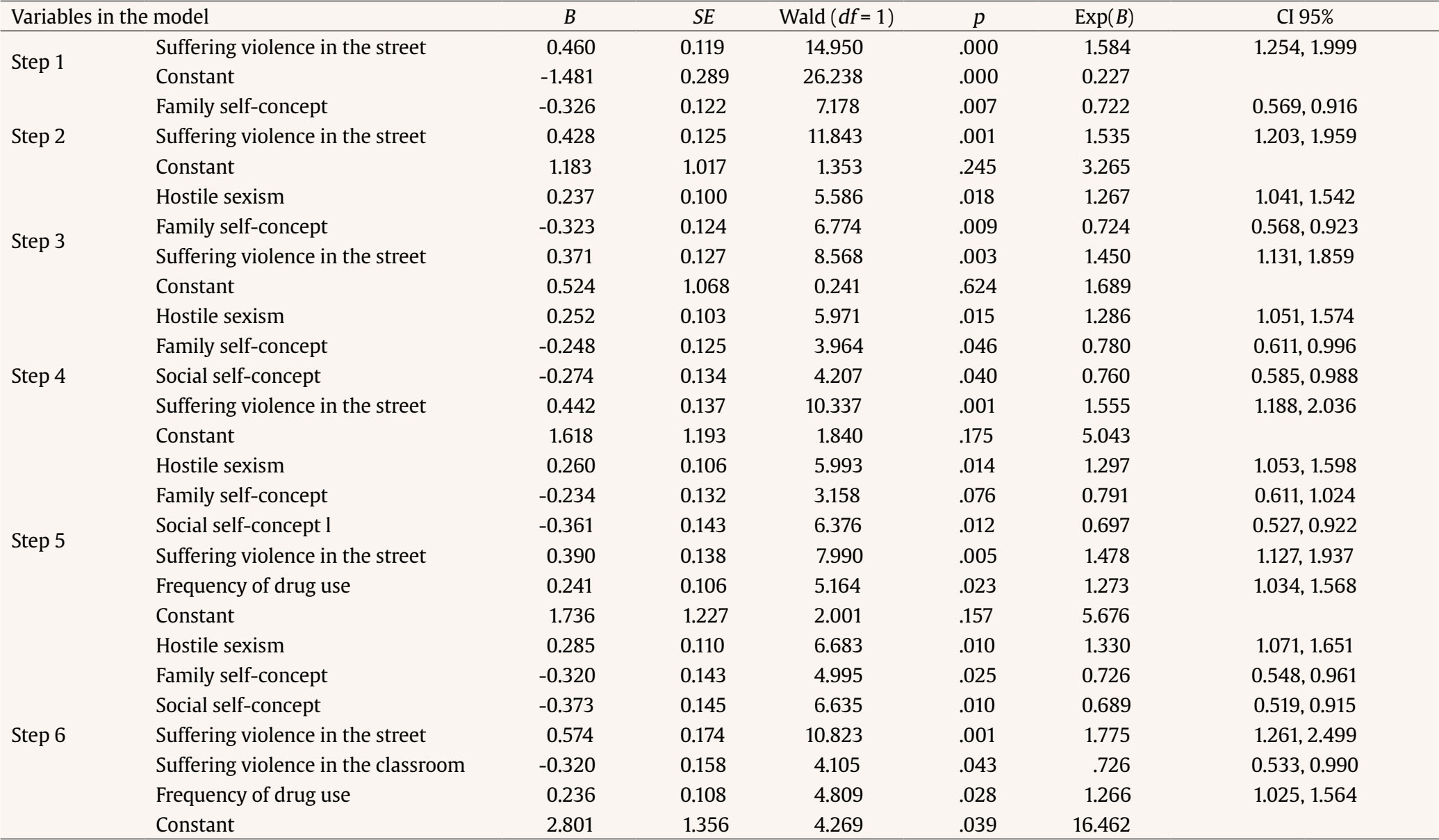

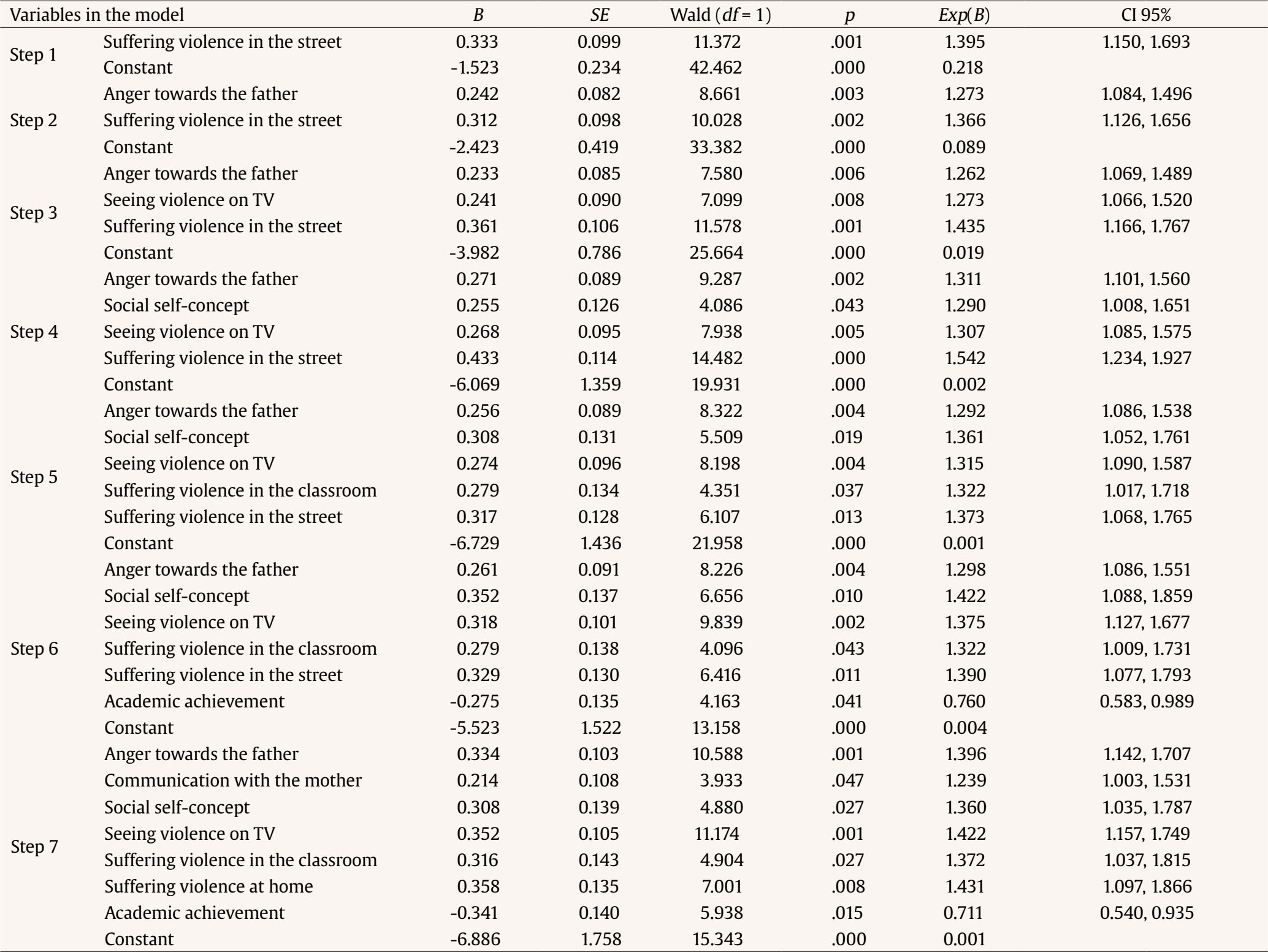

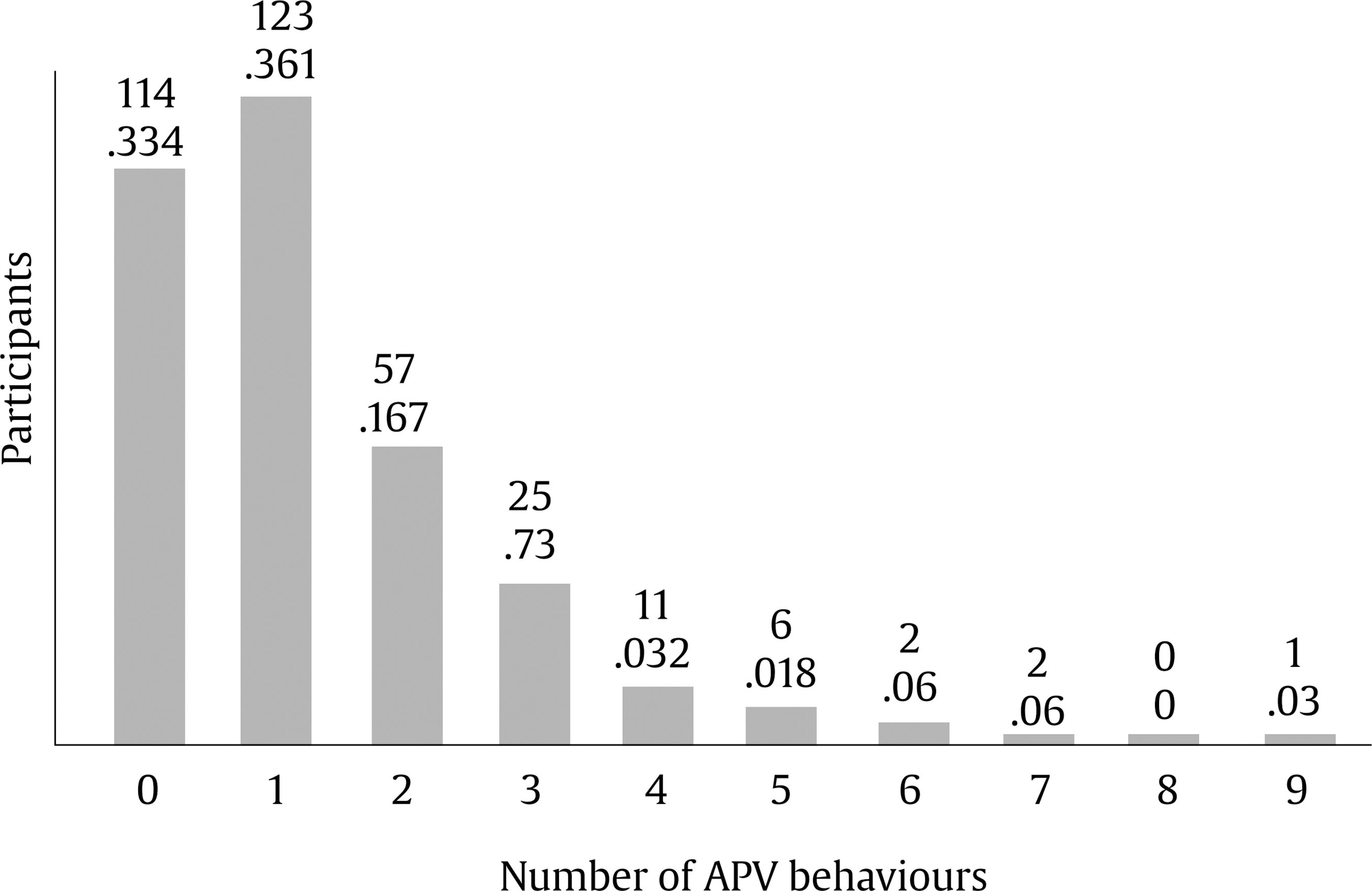

Correspondencia: ammartin@ull.edu.es (A. M. Mart├şn).Adolescent to parent violence (APV) is still the most understudied type of family violence, even though reports filed by parents who are victims, and the number of youths serving judicial measures for this reason, have been on the increase over the last few years (Fiscalía General del Estado, 2021). Even so, the prevalence of APV offenses reflected by official statistics may be lower that the true values, as parents are reluctant to report their children to the authorities (Williams et al., 2016). The available figures have led, both to the generation of social alarm in public opinion that is reflected in the media and to the attraction of the interest of academics (Calvete & Pereira, 2019). Researchers on APV have found some of the difficulties of an emerging field of knowledge, such as the ambiguity of the conceptualization of the phenomenon and the diversity in the terminology and methodology used (Holt, 2012, 2021; Ibabe, 2020). As a result, instead of testing specific theoretical models, most studies have analyzed the influence of individual variables such as sociodemographic characteristics, psychopathology, and personality traits (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020; Loinaz & Sousa, 2020). The aggressor´s gender stands out among the most investigated sociodemographic characteristics. Results from studies with community and clinical samples are inconsistent because the percentage of boys is higher when violent behaviors against parents are severe (Orue, 2019), lower when they are less serious (Suárez et al., 2019), and sometimes there is no statistically significant difference between genders (Cortina & Martín, 2020; Ibabe & Bentler, 2016). What is beyond doubt is that there are more boys than girls serving judicial measures related to APV (Armstrong et al., 2018; Strom et al., 2014), but this may be just because there have always been more boys than girls involved in the judicial system (Fiscalía General del Estado, 2021; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2021). The aggressor´s gender might be a key question for research on APV beyond whether more boys than girls abuse their parents, since research on juvenile delinquency points to gender-based pathways for initiating and maintaining offending behavior (Chesney, 1997; González et al., 2014; Tyler et al., 2001). In the same vein, Armstrong et al. (2018) have pointed out that the life pathway that leads boys and girls to get involved in APV offenses may be different and that it would be useful to study each group separately. They argue that girls with judicial measures, including those for APV offenses, have been victims of physical and sexual abuse, sometimes repetitively, more often than boys (Armstrong et al., 2018; Corrado et al., 2000; González et al., 2014; Moretti & Odgers, 2002). Studies on exposure to violence have consistently shown that adolescents who assault their parents have been victims of violence at home and/or have witnessed marital violence more frequently than those who do not commit APV (Beckmann et al., 2021; Calvete et al., 2013; Calvete et al., 2011; Contreras & Cano, 2016; Gallego et al., 2019; Gámez-Guadix & Calvete, 2012; Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Ibabe et al., 2013; Margolin & Baucom, 2014; Izaguirre & Calvete, 2017; Perkins et al., 2014; Simmons et al., 2018; Ulman & Straus, 2003). At this point it is worth noting that exposure to violence always has consequences, but it is not the same when it occurs at home, at school, in the street or on TV, nor is it the same to be a victim or a witness (Cortina & Martín, 2020; Hernández et al., 2020). In the study of Cortina and Martín (2020) with a community sample, having suffered violence in the street and having witnessed it at home was related to specific behaviors of APV. Hernández et al. (2020) found that suffering violence at home was the type of exposure that allowed the discrimination of adolescents serving measures for APV offenses from both those serving measures for other offenses and normalized students. This relationship is also confirmed for adults serving a prison sentence who admitted to having abused their parents when they were adolescents (Martín et al., 2022). The link between direct exposure to violence at home and parent abuse suggests that the more frequent victimization of girls than boys may be reflected in a gender-based analysis of APV. These results above about the consequences of girls´ and boys´ exposure to violence are consistent with the bidirectional violence hypothesis (Brezina, 1999; Ulman & Straus, 2003), which explains the link between witnessing intimate partner violence at home as a kid and later violence in adult intimate relationships (Black et al., 2010). They also fit well with the theory of intergenerational transmission of violence, which states that there is a relationship between having been a victim of child abuse and abusing children later on as an adult (Haselschwerdt et al., 2019). Lastly, they are consistent with evidence showing that the number, severity, and diversity of adverse experiences to which children are exposed have an impact on their future maladaptive behaviors (Baglivio et al., 2015), including depression (Allwood et al., 2011), anxiety (Tatar et al., 2012), and APV (Calvete et al., 2020; Calvete et al., 2015, Paterson et al., 2002). Early life adversity has also been linked to delinquency in general (Baglivio et al., 2015; Ford et al., 2012; Padrón et al., 2022; Levenson & Socia, 2016; Wolff et al., 2016), and to APV related offenses in particular (Nowakowski-Sims & Rowe, 2017). Other evidence that supports the gender-based analysis of APV is that the use of alcohol and other drugs in adolescents sentenced for APV is higher amongst girls, who also report more depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation than boys (Armstrong et al., 2018). These results are not specific of APV aggressors because there are higher levels of family conflict, drug abuse (Armstrong et al., 2018; Corrado et al., 2000; Simmons et al., 2018; Sondheimer, 2001), and suicide attempts (Lewis et al., 1991) amongst female delinquents, regardless of the type of offense that originated their sentences. But it is especially relevant because of the scientific literature on mental health that has consistently brought to light a link between drug abuse and APV (Calvete et al., 2020). The relationship between aggressor and victim gender has also attracted research interest because APV is mostly directed towards mothers, in community, clinical, and judicial samples (Holt, 2016, 2021). This relationship has led to consider APV as a form of gender-based violence (Downey, 1997). It is true that when mothers have been physically victimized previously by the father, violence against them is higher (Downey, 1997; Ulman & Straus, 2003), especially by their sons (Ibabe et al., 2013). But, again, this effect is mediated by aggressor gender, reflecting the differential socialization of boys and girls according to cultural roles and stereotypes of masculinity and femininity (Cottrell & Monk, 2004; Holt, 2021). The direct relationship between sexist attitudes and APV was explored for the first time by Cortina and Martín (2020). They found a differential pattern for hostile and benevolent sexism for APV behaviors, as in other areas of domestic violence (Juarros-Basterrechea et al., 2019; Martín-Fernández et al., 2018). The roles and stereotypes that exalt power and control over women in personal relationships and that are internalized in the socialization process may be at the root of a differential pattern of violence against mothers. Boys would learn this model of masculinity by observing their fathers, while girls would use violence as a way to distance themselves from the image of female weakness represented by the mother. Therefore, when studying gender bias in relation to APV, it is reasonable considering not only the feelings of hostility towards the female gender, but also the benevolent feelings that coexist with them (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Variables analyzed by previous research on APV that may be related to gender also include empathy, parental warmth, and self-esteem. Low empathy has been inconsistently related to APV (Castañeda et al., 2012; Ibabe & Jaureguizar, 2010; Ibabe et al., 2009), but some authors (e.g., Garrido & Gálvis, 2016) have suggested that narcissism and psychopathy play a role in this relationship. Narcissism has been connected with juvenile delinquency in general (Barry et al., 2007) and with exposure to violence at home (Calvete & Orue, 2013; Young et al., 2003), which is one of the antecedents of APV, as said before. Evidence of a direct relationship between narcissism and APV is provided in a three-year longitudinal investigation by Calvete et al. (2015), in which the lack of parental warmth in the first year led boys to a narcissistic vision of themselves in the second year and to APV in the third year. This lack of parental warmth, defined as positive communication, emotional support, and caring, has been a better predictor of APV than traditional parental styles (Calvete et al., 2014; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012; Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Suárez et al., 2019). In regard to the evidence supporting the relationship between psychopathy and APV, callous unemotional traits have been related to the lack of empathy (Ciucci, et al., 2013) and to criminal conduct (Frick & White, 2008). In the study by Cortina and Martín (2020), uncaring and callousness traits, narcissism, and Machiavellianism were related to specific behaviors of APV and with different strengths. They also found that communication with the mother and anger with the mother, two measures of parental warm, were associated to specific APV behaviors. Lastly, low self-esteem has been related to APV, citing research by Ibabe and Jaureguizar (2010, 2012) and Ibabe et al. (2009) with judicial samples. Nevertheless, these results are inconsistent with evidence from the research of Ibabe et al. (2014), with the same type of sample, and with the low correlation found by Calvete et al. (2011) in a large community sample of adolescents. Some authors (Cortina & Martín, 2020; Hernández et al., 2020; Martín et al., 2022) have stated that self-concept is a more appropriate construct to be studied in relation to APV than self-esteem, given its stability over time and the possibility to differentiate between several domains of adolescent life (García & Musitu, 2014). In the study by Cortina and Martín (2020), both family and physical self-concepts were related to APV in a community sample. Hernández et al., (2020) showed that the differences between adolescents serving judicial measures for APV, compared to both those who had committed other offenses and to the group of students, focused on the family facet of self-concept. Martín et al. (2022) replicated results related to family self-concept with adults serving a prison sentence who admitted to having abused their parents when they were adolescents. To sum up, the aim of this study is to carry out a gender-based analysis of the profile of girls and boys who report having and not having committed APV in a community sample, based on Armstrong et al.´s (2018) proposal to investigate APV in each gender separately. To this end, drug abuse, academic performance, family structure, mental health, exposure to violence, self-concept, parental warmth, callous unemotional traits, narcissism, and sexism are related to APV for boys and girls. Differences between boys and girls in the variables related to APV, and in the percentage explained by them, are anticipated. Likewise, as APV has consistently been seen since the Hammurabi Code as “an unnatural conduct that deserved severe punishment” (Calvete & Pereira, 2019, p. 20), and considered as an even more reprehensive behavior than violence towards offspring or towards the intimate partner, a measure for social desirability is also included in this investigation. Participants The sample included 341 high school students between the ages of 14 and 20 (M = 16.33, SD = 1.16), who lived in both touristic (65.7%) and rural areas (34.3%); 53.1% of them were girls, 20.2% of the participants were in 3rd grade, and 18.8% in 4th grade of Compulsory Secondary Education, whereas 36.1% were in 1st grade and 24.9% in 2nd grade of High School. None of them had had any judicial measures at the time of the study. The mean for academic performance was 6.63 (SD = 1.73); 55.7% reported drugs or alcohol use, with an average frequency of 2.77 out of 10 (SD = 2.32); 3.2% informed to have been diagnosed with depression and/or anxiety, 60.1% lived with both parents, 15.5% only with the mother, 7% with the extended family, 3.5% only with their father, 3.5% part-time with each parent, and only one participant was adopted; 27.6% of those who lived with only one of their parents pointed to separation or divorce as the cause, whereas 3.5% referred to widowhood and 5% to having a single mother. Instruments Participants answered a questionnaire which included nine scales, as well as several items on drug use, mental health diagnosis, family structure, and whether they have of had had judicial measures. The scales were the following:

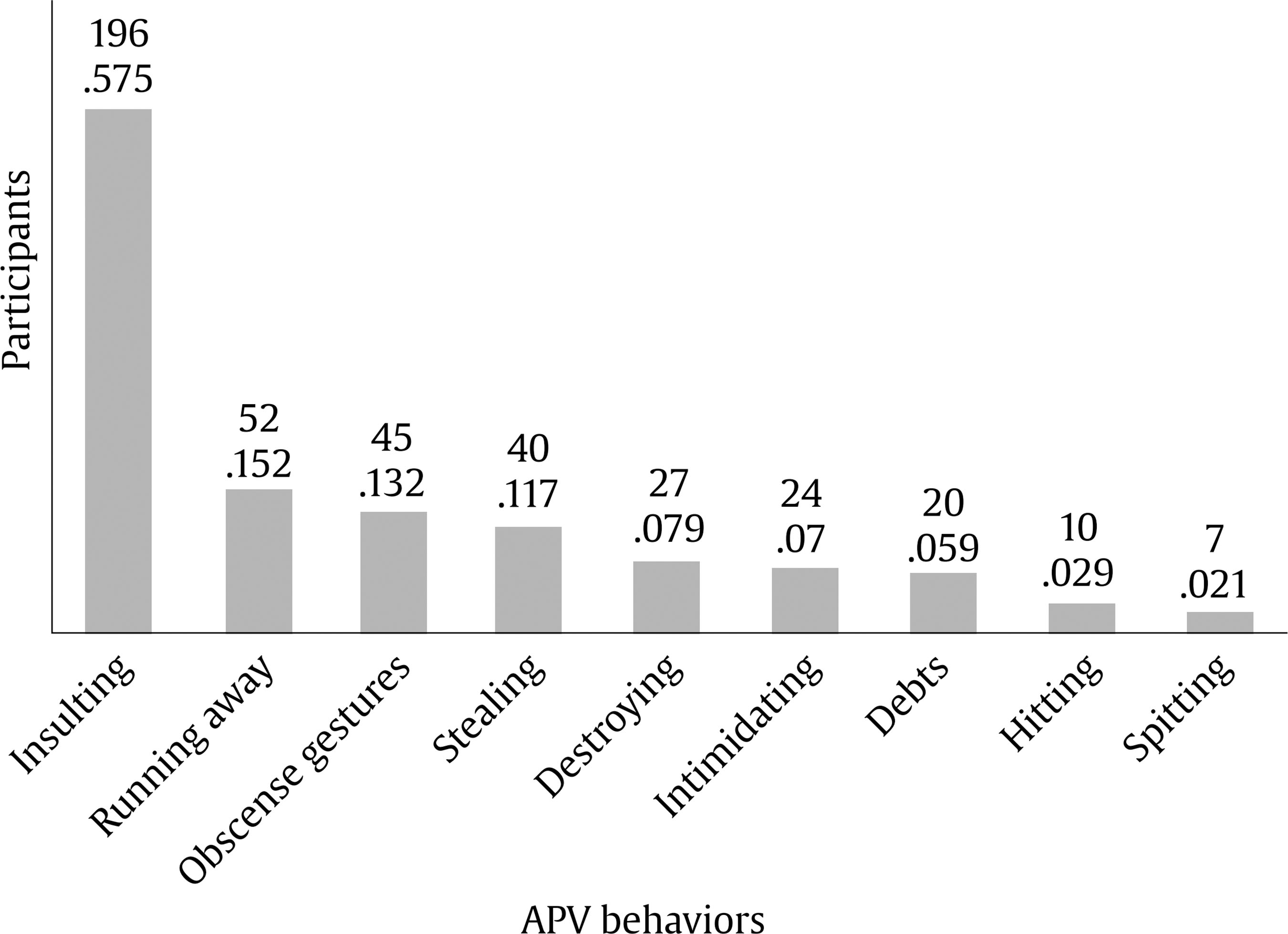

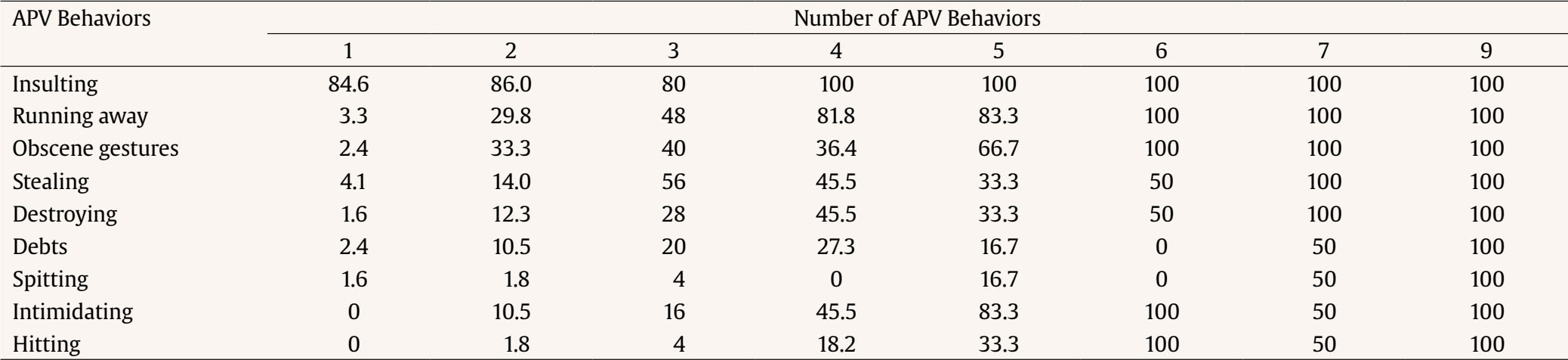

The Spanish adaptation of Crowne and Marlowe´s (1960) Social Desirability Scale was applied through the Spanish adaptation of Ferrando and Chico (2000). The scale includes 33 items that participants were asked to answer saying whether they felt the sentence reflected the way they were (true) or not (false). Ferrando and Chico (2000) provide evidence of validity and reliability for this scale. In this study the internal consistency was acceptable (α = .66). Procedure After permission from the principals of the educational centers was obtained, students were informed that the university was carrying out a research project on “current adolescent habits and behavior, both inside and outside the family”. They were informed that their participation was anonymous and voluntary. All adolescents agreed to collaborate and signed an informed consent. Parents´ informed consent of those under 18 years of age was requested before asking them to collaborate in the study. Participants answered the questionnaire in the classroom, during their regular school schedule, in around 40 minutes. Data Analysis Design Several data analyses were carried out using the SPSS 22.0 statistical package. First, tests of χ2 were used to check the relationship between the frequency of participants who acknowledged having carried out each APV behavior and gender. Gender also was related to the number of APV behaviors carried out by each participant using χ2, because this variable does not follow a normal distribution, as most people are not violent towards their parents. Then, we calculated the proportion of those who had performed each behavior in relation to the number of total behaviors performed. Secondly, a MANCOVA model was applied having gender as an independent variable, social desirability as co-variable, and the frequency in which each participant had carried out each APV behavior as dependent variables. Pillai’s trace was used instead of Wilks’s lambda because it is more robust when statistical assumptions underlying the lineal model are not fully met. This is the case because APV behaviors do not follow a normal distribution, as most people are not violent towards their parents. Thirdly, a MANCOVA model was applied using gender and dichotomized APV as independent variables, social desirability as co-variable, and participants’ scores in the subscales of the scales of exposure to violence, parental warmth, self-concept, sexism, narcissism, and psychopathy as dependent variables. Before running the MANCOVA, we calculated internal consistency (Cronbach α) and descriptive analysis for the APV scale and the subscales of the scales for exposure to violence, parental warmth, self-concept, sexism, narcissism, and psychopathy. As internal consistency for the APV scale was reached only after eliminating one item, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out, using the JASP 1.15 package, to assure the dimensionality of the 8-item scale. The unweighted least squares estimation method was used, because it gives more robust model fits and more accurate parameter estimation for CFA than the maximum likelihood method when data does not meet the multivariate normality assumption, as in this case (Ximénez & García, 2005). Fit indices were χ2, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR. After confirming the unidimensionality of the 8-item scale, the frequency in which each participant has carried out each APV behavior was averaged for further analysis. Lastly, logistic regression analyses were carried out to explore the percentage of variance of the dichotomized APV explained by the variables under study, for girls and for boys separately. APV was dichotomized assigning a 0 to participants whose averaged frequency of APV behaviors was 0 and 1 to those whose averaged frequency was ≥ 1. Participants with scores between 0 and 1 were considered missing for this analysis. Logistic regression was considered an appropriate analysis to perform on these data because it does not undertake the assumptions that underlie lineal regression or discriminant analysis, especially the homoscedasticity, the linearity, and the normality. This analysis gives us, in addition to the rates of fit, Nagelkerke’s R2, the percentage of cases correctly classified by the equation, and the values of Exp(B) or odds ratio for each predictor. The results of the statistical analyses are presented in the order in which they were described in the data analysis section. Firstly, χ2 contrasts showed that there was no statistically significant association between gender and the frequency of violent behaviors. Frequency ranged from 57.7% (n = 196), for insulting, to 2.1% (n = 7), for spitting, as shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 Frequency of Participants Who Admit Having Carried out Each of the APV Behaviors, regardless of Their Periodicity.   Chi-square (χ2) contrasts also indicated that there was no statistically significant association between gender and the number of APV behaviors. The distribution of the number of APV behaviors is displayed in Figure 2. Most of the participants who carried out APV performed a single violent behavior (36.1%), 16.7% two, and 7.3% three. Only 3.2% (n = 22) of the participants admitted having committed more than three violent behaviors. Adolescents who had not carried out any type of APV were 33.4% (n = 114). To insult was the most consistent behavior among the participants, and was carried out by the majority (84.6%, n = 104) of those who engaged in only one violent behavior, as reflected in Table 1. Table 1 Percentage of Participants who Have Carried out Each Specific Behavior in Relation to the Total of Those Who Have Carried out the Same APV Behavior   Note. In each cell there is the percentage of those who have carried out the behavior given their total of behavior; the difference between this value and 100 corresponds to those who have not carried it out. Secondly, with the purpose of carrying out a gender-based analysis of APV behaviors, a MANCOVA was done using participants’ scores for the frequency with which they acknowledged to have performed each of the APV behaviors as dependent variables, gender as the independent variable, and social desirability as a covariable. The multivariate effect for APV behaviors was not statistically significant but was for social desirability, Pillai’s trace = .08, F(9, 331) = 3.18, p < .001, ηp2 = .08. This suggests that social desirability influences self-report of insulting and obscene gestures but that there is no statistically significant difference between boys and girls after controlling its effect. The means for the nine APV behaviors were very low, ranging from .05 to .28, as shown in Table 2. Table 2 Descriptive Statistics for the APV Behaviors, from the Most Frequent to the Least Frequent, and for the Total   1Without Insulting. To average the APV behaviors for further analyses, the internal consistency of the scale was calculated obtaining a Cronbach α of .69, after eliminating insulting from the scale. A confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to assure the dimensionality of the 8-item scale with the unweighted least squares estimation method and JASP 1.15 package. The chi-square test was not statistically significant, χ2(20) = 31.44, ns, and the remaining indexes showed an excellent model fit (CFI = .97, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .041, 90% CI [.002, .067], SRMR = .084). All item loadings were statistically significant (p < .001 for all zs) and over .22. Standard errors for all items remained below .052. The means and the standard deviations for this 8-item scale are also shown in Table 2. Thirdly, in order to conduct a gender-based analysis of the subscales of the scales for exposure to violence, parental warmth, self-concept, sexism, narcissism, and psychopathy, included in the questionnaire, a MANCOVA was carried using gender and APV dichotomized as the independent variables, social desirability as the co-variable, and the scores in these subscales as dependent variables. Internal consistency was assessed before averaging subscale items and then the descriptive analyses of the resulting variables. Table 3 displays Cronbach α, which ranged from .66 to .93. Table 3 Cronbach α, Means and Standard Deviations for Adolescents Who Have or Have not Acknowledged Having Abused Their Parents, and MANCOVA Intersubject Tests for Dichotomized APV, after Controlling the Influence of Social Desirability   *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001, ns = non significant. MANCOVA results show that, even though social desirability has a statistically significant multivariate effect, Pillai’s trace = .27, F(25, 256) = 3.83, p < .001, η2 = .30, the multivariate function for the interaction between dichotomized APV and gender remains statistically significant after removing its influence, Pillai’s trace = .14, F(26, 255) = 1.65, p < .027, η2 = .14. The variables with a statistically significant univariate effect for this interaction, after removing the influence of social desirability were only hostile sexism, seeing violence at home, and being a victim of violence in the street; η2 values were .015 in the three cases. Means show that boys from the APV group were those who scored the highest values both in hostile sexism (M = 3.78, SD = 2.16) and in being victim of violence in the street (M = 2.47, SD = 2.07) and girls from the NoAPV were those who scored the lowest values (M = 1.78, SD = 1.84; M = .79, SD = 1.28). For seeing violence in the home the pattern is different, as girls from the APV group were those who scored the highest values (M = 2.15, SD = 2.61) and girls from the NoAVP group those who scored the lowest values (M = .71, SD = 1.56). According to the objectives of the study, it is especially worth noting the results related to the multivariate function for dichotomized APV, Pillai’s trace = .21, F(26, 255) = 2.66, p < .001, η2 = .21. Inter-subject effects remained statistically significant, after controlling social desirability, for uncaring, narcissism, hostile sexism, trust towards the father, communication with the father, anger towards the father, trust towards the mother, anger towards the mother, academic self-concept, family self-concept, seeing violence in the street, seeing violence at home, suffering violence in the classroom, suffering violence in the street, and suffering violence at home. As shown in Table 3, adolescents who acknowledged having abused their parents scored higher than those who did not in uncaring, narcissism, hostile sexism, anger towards the father, anger towards the mother, seeing violence in the street, seeing violence at home, suffering violence in the classroom, suffering violence in the street, and suffering violence at home. Besides, adolescents who did not acknowledge having abused their parents scored higher than those who did in trust towards the father, communication with the father, trust towards the mother, academic self-concept, and family self-concept. Although no statistically significant differences were found, means follow the same pattern for the possible risk factors of callousness, machiavellianism, dominance, benevolent sexism, physical self-concept, seeing violence in the classroom, seeing violence on TV, and possible protective factors such as communication with the mother, social self-concept, and emotional self-concept. Lastly, in order to carry out a gender based analysis of the variables that account for the higher percentage of APV variance, two logistic step by step regression analyses, one for boys and one for girls, were carried out with the dichotomized APV as the classificatory variable (APV group vs. NoAPV group) and the variables under study as predictors. These variables were the scores in the subscales of the scales for exposure to violence, parental warmth, self-concept, sexism, narcissism, and psychopathy. The analyses also involved age, academic performance, and frequency of drug use. The results, displayed in Tables 4 and 5, show that the variables included in the final models are different for boys and girls. Table 4 Step by Step Logistic Regression Analysis of the Variables under Study in Relation to the Dichotomized APV, for Boys   Note. Nagelkerke R2 = .40; 77.3% correctly classified. Table 5 Step by Step Logistic Regression Analysis of the Variables under Study in Relation to the Dichotomized APV, for Girls   Note. Nagelkerke R2 = .40; 77.3% correctly classified. For boys, the model allows correct classification of 77.3% of cases including the variables of suffering violence in the street (B = .574), family self-concept (B = -.320), suffering violence in the classroom (B = -.320), social self-concept (B = -.373), hostile sexism (B = .285), and frequency of drug use (B = .236) (see Table 4). Looking at the Exp(B), suffering violence in the street increases 1.775 times that of abuse of parents, whereas hostile sexism does so 1.330 times and frequency of drug use 1.266 times. On the contrary, social self-concept reduces APV 0.311 times and both family self-concept and suffering violence in the classroom do so 0.274 times. For girls, the model that allows for correct classification in 77.8% of cases includes the variables for suffering violence at home (B = .358), seeing violence on TV (B = .352), anger towards the father (B = .334), suffering violence in the classroom (B = .316), social self-concept (B = .308), communication with the mother (B = .214), and academic achievement (B = -.341) (see Table 5). Exp(B) indicate that suffering violence at home increases APV 1.431 times, seeing violence on TV 1.422 times, anger towards the father 1.396 times, suffering violence in the classroom 1.372 times, social self-concept 1.360 times, and communication with the mother 1.239 times. By contrast academic achievement reduces APV .289 times. The aim of this study was to carry out a gender-based analysis of the psychosocial characteristics of a community sample of adolescents who report having committed APV. The results show, firstly, that APV rates fit into the estimated range for world prevalence (Gallagher, 2008; Simmons et al., 2018), but that they are lower than the rates found in the Spanish research with community samples (Calvete et al., 2014; Ibabe & Bentler, 2016; Ibabe et al., 2013). This divergence may be due to the differences among the territories of the Spanish samples, but it seems more likely that it relates to differences in the instruments used to measure APV (Cortina & Martín, 2020; Gallego et al., 2019; Holt, 2021; Ibabe, 2020; Simmons et al., 2018). The results also indicate that the proportion of boys and girls engaged in APV is similar, in line with the conclusions of the meta-analysis by Simmons et al. (2018) and with the study carried out in Spain by Ibabe and Bentler (2016). Social desirability affects the APV self-report, as well as the scores of some of the variables used to predict APV, but its impact could be controlled statistically. This result warns about the need to always take into account the possible influence of social desirability on APV when interpreting data, because of its associated great social reproach (Calvete & Pereira, 2019). Another justified caution has to do with the need of considering only the reiteration of behavior when measuring APV, disregarding sporadic incidents of violence towards parents. Lastly, some behaviors traditionally labelled as APV, although reiterated, are currently so common in adolescent-to-parent relationships that it may be better to exclude them from the analyses, like insulting in this study (Pereira et al., 2017; Simmons et al., 2018). Despite the interest in what has already been said, the main result of this study is that, as expected, there were differences in the variables that best explain APV for boys and for girls (Pereira et al., 2017; Simmons et al., 2018). There were statistically significant differences between adolescents who acknowledged having abused their parents and those who did not for many variables, but these differences do not allow knowledge of which variables explain more APV variance for each gender. Differences in variables that increase or reduce the probability of APV for boys or for girls may not be statistically different when comparing APV and non APV groups, and variables that allow a differentiation between APV and non APV groups may not increase the probability of APV when each gender is analyzed separately. In this study, the probability of APV is increased for boys by having been a victim of violence in the street, showing hostile sexism, and frequency of drug use, in this order, whereas family self-concept, suffering violence in the classroom, and social self-concept reduce it. For girls, the probability of APV is increased by having suffered violence in the street, having seen violence on TV, feeling anger towards the father, suffering violence in the classroom, social self-concept, and having good communication with the mother, while academic achievement reduces it. These different profiles deserve some comment. As was said above, one of the most replicated pieces of evidence from previous research is that exposure to violence relates to subsequent violence, including APV (Gallego et al., 2019; Simmons et al., 2018). These results are consistent with the research on adverse childhood experiences, the bidirectionality of violence hypothesis, and the intergenerational transmission of violence theory described above. However, this study lets us take a step further in showing that the pattern differs for APV carried out by boys and by girls in the community, as Armstrong et al. (2018) suggested for judicial samples. For boys, the most relevant exposure to violence is in the street, whereas for girls it is at home and, to a lesser extent, on TV. It is worth noting that, except for TV violence, what predicts APV on this occasion is being a victim and not just seeing violence. These results are consistent with Hernández et al.´s (2020) because in their study what differentiates boys with judicial measures, irrespective of the type of offense committed, from boys in the community is suffering violence in the street. A similar pattern is found for frequency of drug use, which differentiated boys with judicial measures, irrespective of the type of offense committed, from boys in the community. The results regarding the relationship between APV and drug use are consistent with previous research on APV (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020), but just for boys. These findings are in line with research showing a relationship between juvenile delinquency and drugs (Corrado et al., 2000; Sondheimer, 2001), but do not replicate those of Armstrong et al. (2018) showing the highest consumption amongst girls with judicial measures for APV related offences. In that study, depression and anxiety issues were also higher for girls with judicial measures for APV related offences. In the current study, although girls with these problems doubled boys, they were only 3.2% of the sample, maybe because it was a community sample, in which the probability of “traditional” APV (Pereira & Bertino, 2009) is lower than in clinical or judicial samples. The results for suffering violence at home are also consistent with Hernandez et al.´s (2020) because it was this which differentiated boys with judicial measures for APV from the other two groups. In the current study, suffering violence at home predicted APV for girls in the community, but not for boys. These different profiles could be a result of a distinctive socialization for boys and girls, according to gender roles and stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. For boys, APV would be a way to exercise control over their mothers, while for girls it would be aimed at distancing them from the image of female weakness and helplessness (Cottrell & Monk, 2004). This explanation, although reasonable, is just a hypothesis, as the victim gender was not recorded in this study. Nevertheless, it is consistent with the fact that hostile sexism is related to APV only for boys, while for girls suffering violence at home and feeling anger towards the father seem to be more relevant. Also, according to their traditional sex roles, the boys´ profile is more outdoors oriented, whereas the girls´ profile is more indoors oriented (Jackson & Gee, 2006). Anger towards the father may be interpreted in the context of victimization at home, but can also be understood in the adolescent-to-parent relationships involved in APV. Indeed, one of the contributions of this study is to approach the construct of parental style through concepts such as trust, communication, and anger towards both parental figures, as was carried out by Delgado et al. (2016) (see also Cortina & Martín, 2020). In this case, although anger to the father and communication with the mother were relevant and only for girls, the results indicate that further research connecting parent-child relationships with APV in the broader context of the theory of attachment (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1982) may be more promising than that on parental discipline or traditional parental styles (Rico et al., 2017). In addition to the mentioned variables, self-concept displays a relevant role in explaining APV, both in the case of family and social self-concept. Previous studies had found a relationship between family and academic self-concept with adolescents´ revenge (León, 2019) and cyberbullying (Romero et al., 2019). Hernández et al. (2020) also showed that boys serving a sentence for APV have a more negative family self-concept when compared to other young offenders and to non-offenders (see also Cortina & Martín, 2020; Martín et al., 2022). Therefore, in designing this study it was coherent to expect that family self-concept was the dimension of self-concept which was most related to domestic violence, not only because both refer to the same life domain, but also because family relationships have an important role in the origin, maintenance, and desistance of offending behavior (Martín et al., 2019; Redondo et al., 2022). Nevertheless, it was not anticipated that social self-concept would result in a risk factor for girls and a protective factor for boys. This unexpected result may be understood also by turning to the indoor/outdoor orientation linked to gender (Jackson & Gee, 2006), but it will remain unclear why this is so until future research goes deeper into the role of self-concept in APV. What is evident is that self-concept seems to be a more appropiate construct to be studied in relation to APV than self-esteem, given its stability throughout time and the possibility to differentiate between several facets of the adolescent identity (García & Musitu, 2014). The most unexpected finding in this study has been that psychopathic traits and the dimensions of narcissism did not enter into the models for APV. This finding may be seen as contrary to the finding by Calvete et al. (2015) with respect to narcissism, and to results of Martínez et al. (2018) on difficulties in recognizing and expressing emotions. At this point it is worth noting that there were statistically significant differences between the two groups for uncaring and for narcissism, with a big size effect. However, there are other variables which are more important when considering the contribution to the variance of APV in boys and girls. The main limitation of the current study is the reduced number of participants in the APV group. Since APV is an antisocial behavior, and by definition uncommon in the general population, future research should start from an even larger initial sample (e.g., Calvete et al., 2013) to have enough participants who have engaged in APV at different levels, thereby allowing multivariate analyses to be carried out with more conclusive results. A second limitation is that it has not been measured whether the APV behaviors were aimed only at the mother, the father, or both. Although mothers are usually the victim in APV cases, it is necessary to record victim gender in each case to analyze the interaction with the aggressor gender in conclusive terms. Also, the cases of violence towards siblings, either as a type of instrumental violence aimed to make parents suffer or as hostile violence by itself, should be considered, as they are increasing (Desir & Karatekin, 2018). Lastly, although it is very complex to access parents, it would be interesting to take them into account as a source of information simultaneously with their children, in order to compare both views of APV (Calvete & Orue, 2016). Despite the mentioned limitations, this study provides results that broaden knowledge about APV by giving a gender-based approach that could contribute to designing more conclusive research in this area. Until now, gender has been considered only to explore differences in the amount and type of violence exerted by boys and girls, or to argue that, since the mother is the most frequent victim, APV is a manifestation of gender-based violence. Previous research on criminal behavior indicates that basing intervention on factors that are not empirically related to the problem behavior, or that are only moderately connected, not only reduces the efficacy of the programs, but can make the problem worse (Andrews & Bonta, 2010). Besides, research is providing evidence to support that effective intervention with girls and women offenders is gender based (Brown & Gelsthorpe, 2021). In the specific field of APV, professionals are turning to specific programs because generic interventions for conduct disorders have not proven to be effective (Ibabe et al., 2018, 2019). APV is a complex phenomenon that requires considering as many factors as possible in order to design effective interventions (Loinaz et al., 2017; Loinaz & Sousa, 2020; McCloud, 2021). With this purpose in mind, the proposed approach points to the need for further research that takes into account the differential experiences and characteristics that lead boys and girls to be violent against their parents. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Martín, A. M., & Cortina, H. (2023). Profiles of adolescents who abuse their parents: A gender-based analysis. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica, 33, 135-145. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a5 Funding: This work was co-funded by the Agencia Canaria de Investigación, Innovación y Sociedad de la Información [Canary Islands Agency for Research, Innovation and Information Society], of the Consejería de Economía, Conocimiento y Empleo of the Gobierno de Canarias [Ministry of Economy, Knowledge and Employment of the Canary Islands Government] and the Fondo Social Europeo Programa Operativo Integrado de Canarias 2014-2020, Eje 3 Tema Prioritario 74 (85%) [European Social Fund Integrated Operational Program of the Canary Islands 2014-2020, Axis 3 Priority Topic 74 (85%)], through the Ayuda del Programa Predoctoral de Formación del Personal Investigador dentro de programas oficiales de doctorado en Canarias [Aid from the Predoctoral Program for the Training of Research Personnel in official doctoral programs in the Canary Islands], granted to the second author. Referencias |

Cite this article as: Martín, A. M. & Cortina, H. (2023). Profiles of Adolescents who Abuse their Parents: A Gender-based Analysis. Anuario de Psicolog├şa Jur├şdica, 33(1), 135 - 145. https://doi.org/10.5093/apj2023a5

Correspondencia: ammartin@ull.edu.es (A. M. Mart├şn).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS