Systematic Review of the Indirect Relationships of Thwarted Belongingness and Perceived Burdensomeness in Suicide

[La revisión sistemática de la relación indirecta entre la pertenencia social frustrada y la sensación de ser una carga en el suicidio]

Patricia Espinosa-Salido1, Miguel A. Perez2, Enrique Baca-García3, and María Provencio Ortega2

1Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain; 2Universidad Camilo José Cela, Madrid, Spain; 3Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital Jimenez Diaz Foundation, Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a27

Received 23 March 2020, Accepted 11 September 2020

Abstract

Joiner’s Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS) considers the interpersonal variables of low social belonging and the perception of being a burden on others as drivers of suicidal ideation. This study has sought to review the empirical evidence on this prediction. In all, 40 studies were found. The findings report a major mediator and moderator role of perceived burdensomeness (PB) and thwarted belongingness (TB) in the relationship between the propensity toward suicide and psychological, social, and environmental factors. As the theory predicts, expecting to find that the interaction of both of these variables would be more closely linked to suicidal ideation, this does not appear to have been fully supported, generally finding a greater significance when they were integrated into separate models. It seems that attributing other forms of relationship with suicide for the variables identified by Joiner would provide IPTS with greater empirical support.

Resumen

La teoría interpersonal psicológica del suicidio de Joiner considera las variables interpersonales de baja pertenencia social y la percepción de ser una carga para los demás como impulsores de la ideación suicida. Este estudio revisa la evidencia empírica sobre esta predicción. En total, se han encontrado 40 estudios. Los hallazgos descubren un importante papel mediador y moderador de la carga percibida y la pertenencia frustrada en la relación entre la propensión al suicidio y los factores psicológicos, sociales y ambientales. Como predice la teoría, esperando encontrar que la interacción de ambas variables estaría más estrechamente ligada a la ideación suicida, esto no parece haber sido totalmente respaldado, encontrando generalmente una mayor significación cuando estas se integraron en modelos separados. Parece que atribuir otras formas de relación con el suicidio para las variables identificadas por Joiner proporcionaría a la teoría interpersonal psicológica del suicidio un mayor apoyo empírico.

Palabras clave

Ideation suicide, Pertenencia frustrada, Carga percibida, TeorĂa interpersonal psicolĂłgica, IdeaciĂłn suicida, RevisiĂłnKeywords

Suicide, Thwarted belongingness, Perceived Burdensomeness, Interpersonal-Psychological Theory, Ideation suicide, ReviewCite this article as: Espinosa-Salido, P., Perez, M. A., Baca-García, E., and Ortega, M. P. (2021). Systematic Review of the Indirect Relationships of Thwarted Belongingness and Perceived Burdensomeness in Suicide. ClĂnica y Salud, 32(1), 29 - 36. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a27

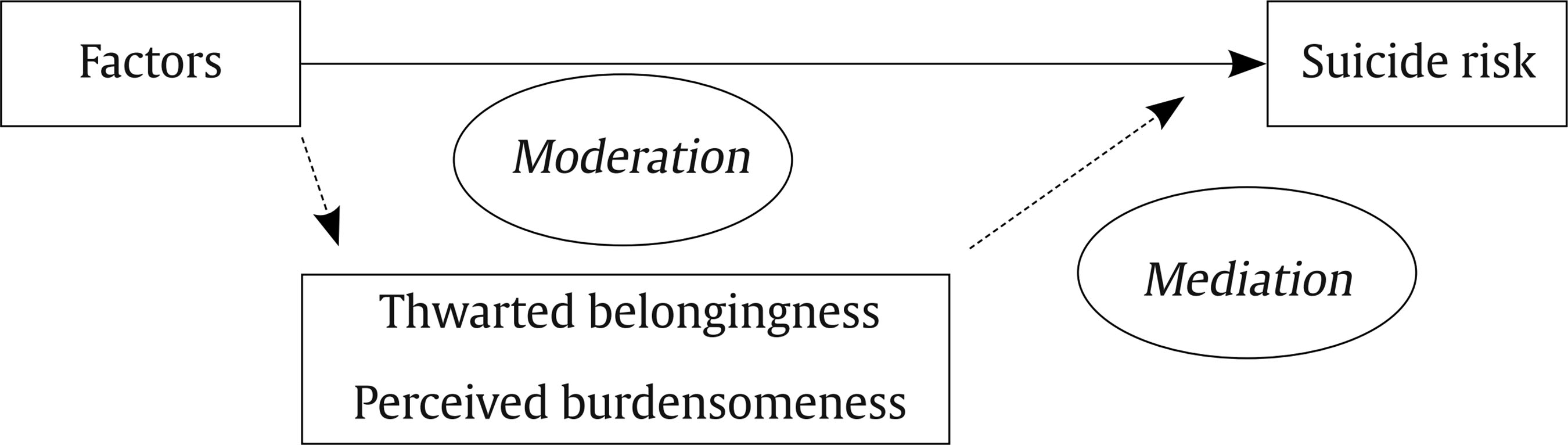

esp.salido@gmail.com Correspondence: esp.salido@gmail.com (P. Espinosa-Salido)According to data provided by the WHO (2017), suicide is one of the main causes of death throughout the world, with around 800,000 people dying in this way every year, whereby it is estimated that a death by suicide occurs every 40 seconds. Many of the models have not been suitably integrating to understand suicidal behaviour (Joiner, 2005). Considering the corpus of empirical evidence that is gathered on an ongoing basis in this science, as in any other field, suicidology has informed a new generation of theories that seek to explain patterns that had not been previously considered, such as why two out of three people considering suicide have ultimately shied away from it (Nock et al. 2008). More recently, in his book Why people die by suicide Joiner (2005) has posited that suicidal behaviour could be explained by the interaction of three factors – two interpersonal variables and the acquired capability – independently of other constructs (Van Orden et al., 2010). The interpersonal variables that influence suicidal ideation are: (1) a sense of low social belonging (TB) and (2) the perception of being a burden on others (PB). As Joiner (2005) explains based on opponent-process theory, etiologically speaking, a body is not designed to cause its own death (this would involve a “struggle” with the survival instinct). For this to happen, repeated exposure has had to be made to aversive stimuli, generating a habituation over time, besides strengthening the opposite response (Solomon, 1998). This means exposures to painful experiences in different contexts and at different times would ultimately lead to a habituation to and tolerance of pain, as well as the absence of fear toward the threat of death (Joiner et al., 2009). The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS) contends that the feeling of social belonging (thwarted belongings, TB) (family, friends, and other social circles) acts as a major predictor of suicidal ideation (Joiner, 2005). TB is described as a dynamic cognitive-affective state (not so much a stable trait) in an individual, which is dimensional and fluctuates over time, and which is influenced by interpersonal and intrapersonal factors (such as the current interpersonal environment, an individual’s active beliefs or thoughts related to their interpersonal environment, and their prevailing emotional state) (Van Orden et al., 2010). IPTS assumes that TB needs to be sustained over time if it is to prompt suicidal thoughts. This construct is closely related to social isolation, a term described by numerous scholars as a major predictor of suicidal behaviour. Studies such as the one by DeCantanzaro et al. (1995) and Qin and Nordentoft (2005) link TB or social isolation to suicidal ideation, revealing it to be a major predictor of suicidal behaviour. The authors understand this multidimensional construct to be a latent variable comprising subordinate variables related to suicidal ideation. These two subfactors are loneliness, “I feel disconnected from others”, and the absence of reciprocally-caring relationships (Van Orden et al., 2010). According to Joiner’s (2005) theory, there is a second variable, understood as the perception of being a burden on others (perceived burdensomeness, PB) (family, friends, or society). Negative circumstances such as being unemployed, family conflicts, or having a physical illness are stressors that could easily prompt this feeling in an individual, and are linked to suicidal behaviour (Dutton et al., 2013; Puzia et al., 2014). As with TB, PB is a cognitive dimensional and dynamic cognitive state whose severity may vary over time. PB may encompass other contexts of a person’s life outside the family, such as friendships. This psychological construct is, in turn, made up of two dimensions of interpersonal functioning: (1) a feeling of not being suitably capable of taking responsibility for others and (2) cognitions of an affective nature (Van Orden, 2010). In short, Joiner’s (2005) IPTS contends that TB and PB are two psychological constructs that are most of the time going to feature in suicidal ideation. This study sets out to review the empirical evidence in multiple populations on the interpersonal variables in the risk of suicide, and specifically whether they moderate or mediate the relationship between other factors and suicide. Another review and meta-analysis have been found about these interpersonal factors of the theory. Ma et al. (2016), found 66 studies where the presence of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired capability in suicide was studied. The conclusion of the review was mixed, finding perceived burdensomeness the most tested and supported relationship (Ma et al., 2016). On the other hand, the analysis found in the meta-analysis (with 122 samples) empirical support for the interpersonal variables of the theory in relation to suicide, although the effect size was moderated by these (Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, et al., 2017) (Figure 1). Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria Criteria were following the PICO strategy for formulating clinical questions (da Costa Santos et al. 2007):

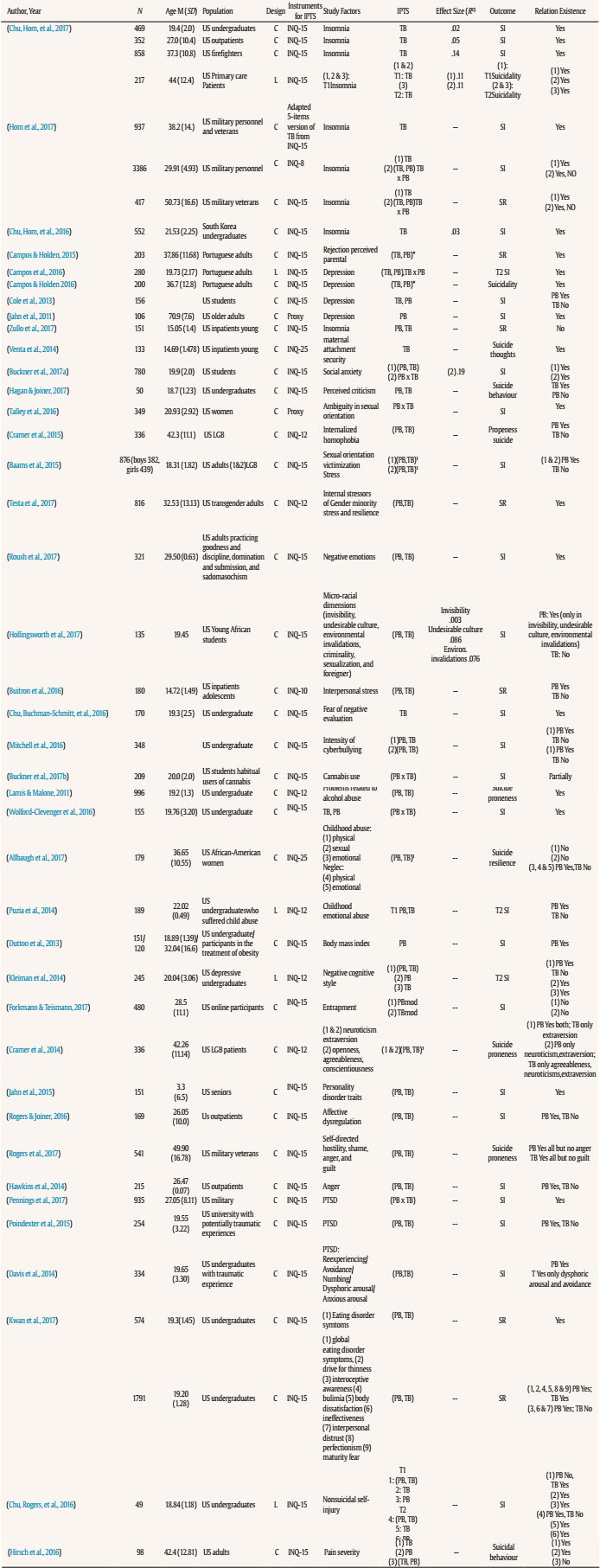

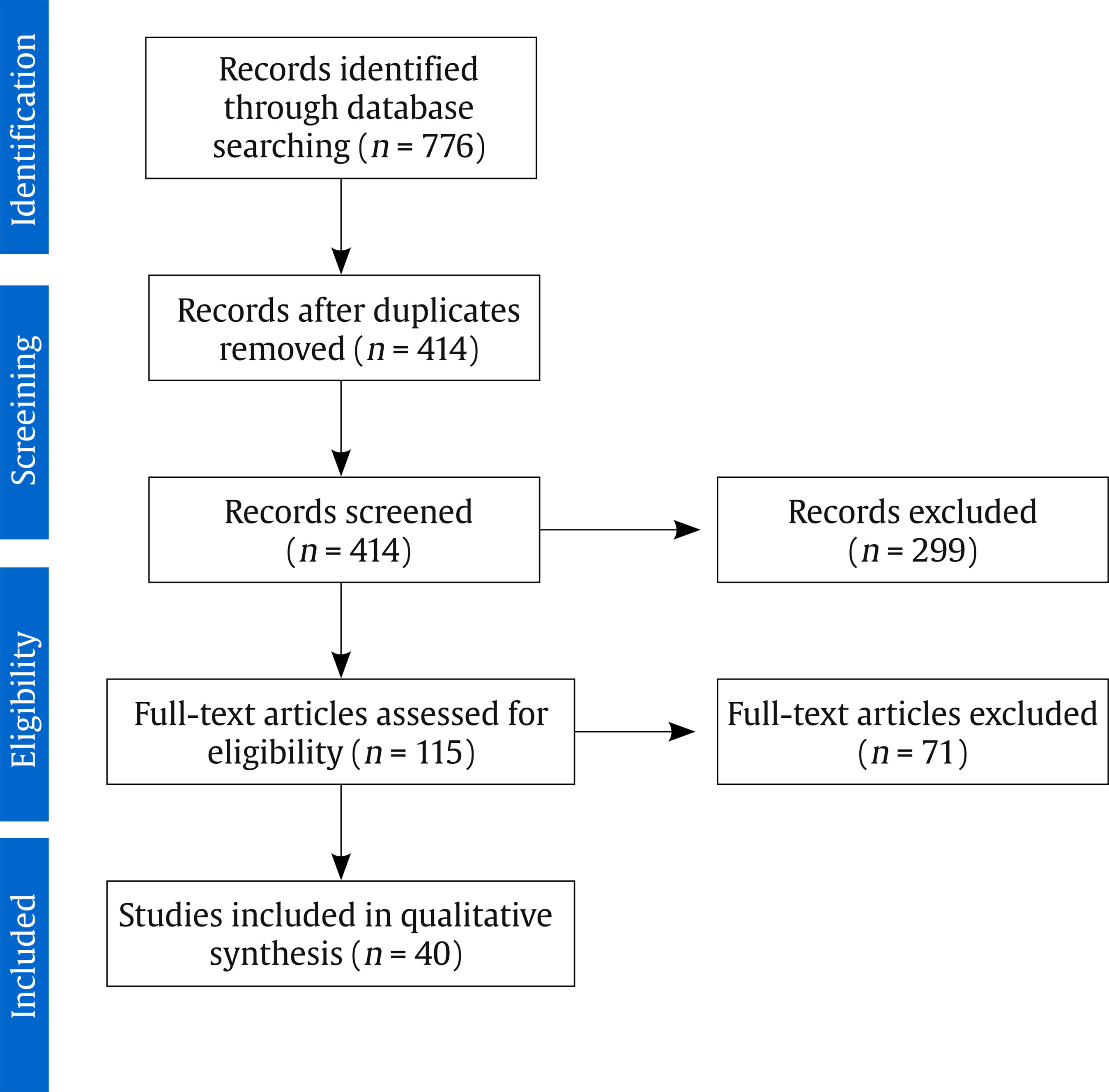

Inclusion criteria for the articles were as follows: (1) the study includes the explicit terms “thwarted belongingness” or “perceived burdensomeness” as moderator or mediator variables; (2) the study includes a suicide construct as outcome; (3)there are statistical analyses of mediation or moderation on the study; (4) the study has been published as of 2005 for the analyses of indirect relationships. No reviews, development texts, or clinical cases are included. Despite this, we included international studies. Finally, unpublished data was not included. In spite of the large body of research out there on the different statistical relationships between Joiner’s interpersonal theory concepts, we only decided to include studies with moderation and mediation data on the “thwarted belongingness” and “perceived burdensomeness” – since the purpose of this review was to respond to this type of relationship. Studies Included To find studies to include in this review, which started in November 28th 2017, we decided to use Scopus, PubMed, and Ebscohost as search systems, having access to databases such as Medline or APA PsycINFO. The controlled key terms used to search were: (Perceived Burdensomeness) OR (Thwarted Belongingness) OR (Interpersonal psychological theory) AND (Suicide). Table 1 Indirect Relationships (from Moher et al., 2009)   Note. TB = thwarted belonging; PB = perceived burdensomeness; SI = suicidal ideation; SR = suicidal risk; L = longitudinal; CS = cross-sectional. statistics: PB, TB = in different mediation analysis models, (PB, TB) = both included in the same mediation analysis model, PB x TB = analysis of moderate mediation between variables, T1 and T2 = time 1 and 2 in longitudinal studies, 1other mediators or covariates included; mod = moderation.>(Hirsch et al., 2016) The sum of studies of the three search systems after having inserted the key words were 776. Using citation management application Endnote version X7 the duplicates were deleted, leaving 414 articles for the first screening. Two independent reviewers (PES, MPO) proceeded to read the abstract by searching for the presence or not of indirect relations analysis; all items that were not quantitative studies were removed – like meta-analysis, qualitative studies or clinical case – with an agreement between the reviewers on the exclusion of studies; 115 articles were found for full-text reading. Each reviewer carried out the reading of the studies, according to the established inclusion and exclusion criteria, removing studies (i.e., investigated other variables of the theory, there were not analyses of indirect relationships between the variables proposed, or these analyses were given in other study variables), 3 articles were excluded for not access to full text, ending up with 40 articles. The review followed Prisma Statement and Checklist (Liberati et al. 2009; Moher et al. 2009), as well as the action guidelines suggested by Cajal et al. (2020). The effect size was calculated given a value of R2. We were not able to do a meta-analysis due to insufficient available data on interaction effects and the heterogeneity of the studies and population (Figure 2). Mediation and Moderation Relationships A total of 40 articles with 46 studies were found with a mediation or moderation analysis of TB (thwarted belongingness) and/or PB (perceived burdensomeness) among psychological constructs and suicide risk (Table 1). Joiner’s IPTS [Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide] constructs have been studied in myriad samples, with a large number of these (34.78%) recruiting university students, military personnel, and veterans (13.4%); 15.21% of this sample is compiled with out- and inpatients, hospital admissions, or mental health sufferers. Three studies (6.52%) in this review noted different variables in Portuguese population, four studies (8.69%) in LGBT and LGB population, two (4.3%) in Afro-American population, and one in South Korean population, the same as in specific populations as practitioners of dominance, submission, and sadomasochism, child abuse, a past history of self-harm, substance abuse or obesity. Almost all the studies are cross-sectional (89.1%). Only five studies (10.8%) took measures from the same population over different moments in time. Quite a few of the studies have investigated whether TB and PB could act as mediators of the symptomology of specific disorders. In a study that identifies the symptomology of an eating disorder (N = 1,791, ages 18 and 47), the results indicate that the desire to be thinner, bulimia, and body dissatisfaction have an indirect impact on the risk of suicide through Joiner’s interpersonal variables, while only PB mediates the relationship with interoceptive awareness, ineffectiveness and lack of trust. In this same study, perfectionism and fear of ageing reveal a moderate mediation through TB and PB and sex. Specifically, perfectionism only impacts upon suicide risk in men through TB, and PB only in women, where it is also stronger (Kwan et al., 2017). Another study with military personnel in which PTSD symptomology is studied (N = 935) finds that more hyperactive people score higher in suicidal ideation through TB solely in the highest levels of PB (Pennings et al., 2017), while Poindexter et al. (2015) have found that PB mediated the symptoms of PTSD, with substance abuse acting as a moderator in this relationship with suicidal ideation. Rogers et al. (2016) studying the symptomology of borderline personality disorder in a sample of 169 outpatients found that PB mediates the relationship between emotional dysregulation and suicidal ideation. Numerous studies have linked depression and insomnia to suicide. Zullo et al. (2017), using a sample of 151 younger psychiatric patients (aged between 12 and 17) in hospital, found that PB and depressive symptoms explain the relationship between insomnia and the suicide risk. A further four studies link a depressive symptomology and suicidal ideation. The results suggest that PB has a greater capacity for mediating between these constructs (Cole et al., 2013; Jahn et al., 2011), with fewer studies finding this relationship on the part of both interpersonal variables (Campos et al., 2016). As regards insomnia, TB seems to play a mediating role in suicidal ideation and risk (Chu, Hom, et al. 2016), although these same studies have not found the same for PB. By contrast, other studies have indeed found this indirect relationship and, what is more, this construct seems to act as a moderator when anxiety mediates insomnia and ideation (Chu, Hom, et al. 2017; Zullo et al., 2017). In addition, this latter indirect effect of TB ceases to have any significance when controlling for symptoms of depression (N = 417 military veterans) (Hom et al., 2017). Substance abuse is another risk factor associated with suicidal behaviour. A study involving frequent users of cannabis (N = 209) has found that consumption is linked to high levels of suicidal ideation through PB solely in high levels of TB (Buckner, Lemke, & Walukevich, 2017). Other studies have reported that the use of substances seems to moderate the relationship among individuals with symptoms of PTSD or victims of domestic abuse and ideation (Poindexter et al., 2015; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2016), and a greater moderation by TB in the association between alcohol-related problems and a propensity toward suicide (Lamis & Malone, 2011). A history of self-harm also appears to be related to suicidal ideation through interpersonal variables (Chu, Rogers, et al., 2016). Concerning social functioning, social anxiety impacts upon suicidal ideation through PB solely when there are also high levels of TB (Buckner, Lemke, Jeffries, et al., 2017). This latter interpersonal construct, nonetheless, appears to mediate the fear of a negative evaluation and perceived criticism (Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, et al., 2016; Hagan & Joiner, 2017). The findings of another study indicate that variables such as interpersonal stress will have an impact on suicidal ideation through PB (Buitron et al., 2016). Elsewhere, a study found that social variables, such as an individual’s subjective assessment of present relationships, might act as moderators of TB in suicidal thoughts (Monteith et al., 2015). Regarding family-related constructs, a study based on the relationship between the style of maternal attachment in childhood and how this might be related to depressive thoughts in the future (N = 133 adolescents) found that not only does TB mediate the relationship between the assurance of the maternal style and depression, but also the relationship between that perception of assurance and thoughts about suicide (Venta et al., 2014). Other family variables such as child abuse – emotional, accumulative and severe – have been associated with suicidal ideation and resilience through PB (Allbaugh et al., 2017; Puzia et al., 2014), while variables such as the perception of parental rejection have found this kind of association with both of Joiner’s interpersonal constructs and suicide (Campos & Holden, 2015). There are studies focussing on other issues of a social nature. For example, a sample of 348 university students revealed that the intensity of cyberbullying is related to suicidal ideation mediated by the PB variable and symptoms of depression (Mitchell et al., 2016). Other studies involving African populations (N = 135) have noted that experiencing certain racial microaggressions – invisibility, culture of low performance or undesirability, and invalidations by the environment – are associated with suffering from higher levels of PB, which is related to higher suicidal ideation (Hollingsworth et al., 2017). A study of 816 transgender adults revealed that internalised transphobia, as well as future expectations, are associated with suicidal ideation through Joiner’s variables (Testa et al., 2017), while internalised homophobia and victimisation due to sexual orientation do so only through PB. This interpersonal construct has only been found linked to the level of depression in the same sample (N = 336 members of the LGB community) mediated by sex (Baams et al., 2015; Cramer et al., 2015). In turn, ambiguity in sexual orientation in a sample of 349 women has been related to suicidal ideation through a moderate mediation, where TB intercedes indirectly between these constructs with higher levels of PB (Talley et al., 2016). Another study involving the LGB population (N = 336) reported that the effects of neuroticism and extraversion are mediated by PB (with a negative indirect effect) in the propensity toward suicide (Cramer et al., 2014). Other studies observing these interpersonal constructs with personality traits or emotions conclude that self-directed hostility, shame, and personality disorder traits – together with symptoms of depression – are related to different suicide variables – ideation, risk – through both interpersonal variables (Jahn et al., 2015; Rogers et al., 2017; Roush et al., 2017). Studies differ regarding guilt and anger. So, while the findings reported by Roush et al. (2017) describe a mediation of guilt in ideation by both interpersonal variables in a sample of 321 adults involved in domination, submission, and sadomasochism, the study by Rogers et al. (2017) only finds mediation by PB. The results are similar for anger: while Rogers et al. (2017) observe it is mediated by TB in relation to the suicide risk, Hawkins et al. (2014) conclude that the associations between anger, suicidal ideation, and behaviour are mediated by PB and TB, albeit to a greater extent by PB. Another study also found that PB mediates the relationship between a negative cognitive style and ideation (Kleiman et al., 2014). As regards the indirect association between the interpersonal variables and other constructs, such as the feeling of entrapment proposed by the integrated motivational volitional model (IMV), no significant results have been forthcoming (Forkmann & Teismann, 2017). Hopelessness has also been studied with regard to suicide and these constructs. A study of 349 women (aged between 18 and 30) found a greater risk of suicidal ideation when they experience hopelessness toward the future together with high levels of PB and TB (Talley et al., 2016). Findings of other reviews regarding the relationship between PB and TB in the suicide phenomenon are mixed and have so far provided partial support for Joiner’s IPTS (Ma et al., 2016). As far as we know, this is the first review to examine whether the interpersonal variables of IPTS may have an indirect influence on suicide, considering other factors distal to Joiner’s theory that have already been addressed in the literature. The results of this review found that PB and TB play a major mediating role in the relationship between the propensity toward suicide and psychological, social, and environmental factors. The constructs found to be most widely studied seem to differ in terms of the variables’ influence. As the theory predicts, expecting to find that the interactions between both variables would be associated more frequently and more strongly with suicidal ideation does not appear to have been fully supported, finding a greater significance when these are integrated in separate models. For example, the research that studied the influence of TB and PB in the relationship between insomnia and a propensity toward suicide reports a greater influence by TB. In depressive symptomology, social constructs and personality traits record a greater indirect influence by PB. The results have generally been mixed, with the indirect relationship on other constructs and the suicide risk through interpersonal variables being largely significant, and all the studies have found indirect associations for one or more of Joiner’s variables. These results might explain the partial support found in the relationship between PB and TB and suicide (Ma et al., 2016). Considering the outcomes of this review, a possible explanation could be that the interpersonal variables of IPTS might affect the influence that other risk factors have on propensity toward suicide. There are studies reporting that resilience factors have an indirect impact on interpersonal variables and the suicide risk (Rasmussen & Wingate, 2011; Tucker et al., 2013; Hollingsworth et al., 2017). This might indicate that just as interpersonal variables may increase or mediate the relationship between risk factors and suicidal ideation, there are other psychological constructs that may protect an individual or weaken the relationship between PB and TB and the suicide risk. The measures used for assessing the interpersonal variables have largely been INQ-15, followed by INQ-12, INQ-18, INQ-10 (Bryan et al., 2010; Van Orden et al., 2012), with less use being made of proxy measures. The populations studied have mostly involved the general population, students, military personnel, veterans, and outpatients. The size of the samples ranges from 49 through to 3,386 participants. Only five longitudinal studies have been found, which restricts the majority of the results to a specific moment in time and not the changes in the interpersonal variables on the suicide risk, with an interesting research stream being their influence on suicidal ideation over time. It is not only suicidal ideation that has been included as a outcome variable, as other studies evaluate other constructs – risk, conducts, suicidal behaviour, propensity towards suicide – which could encompass more aspects or facets other than suicide, with this being one of the study’s major limitations. On the other hand, the so-called “grey literature” has not been included in this review – only the published articles have been selected – so the studies published in this review may not be fully representative of the current literature. Another significant limitation is that information on other variables included in mediation models is not included. The review did not provide information on the total or partial mediation of interpersonal variables in the regression models. Authors (Hayes, 2013) comment that if the direct influence between the independent and the dependent variable is not zero (not just lose significance), once the mediating variables are inserted into the model this could be implying that not all the variables involved would be in the relationship between the independent variable and the result. To conclude, the results of this review reveal that it seems that the variables described by Joiner could have a type of indirect influence on other psychological constructs, TB appearing to have a minor influence on the relationship of other psychological factors (Ma et al., 2016; Chu, Buchman-Schmitt, et al., 2017) and suicide so there could be different relationships between the constructs from which the theory stipulates at the beginning. On the other hand, and seeing the variation of TB influence, other important constructs could have influence on suicide that the theory could not have taken into account. Theory takes hopeless into account, though only one study has been found to specifically assess the IPTS hypothesis regarding the transition of passive suicidal ideation to active suicidal ideation, but the study does not support this hypothesis (Baertschi et al., 2017). Future lines of research should test this. In addition to the influence of TB and PB, this review points out the importance of these social factors which seem to influence the relationship of other proximally-acting factors or cognitive traits (such as fear of negative evaluation, interpersonal stress, rejection perceived parental) with suicide. The results of this review could hint at the influence of subjective perception of social environment on subjects with suicidal ideation. As far as the literature has been studied, there is a great influence on the part of IPTS variables, which helps us to better understand this phenomenon, where there are many factors and variables to consider. Knowing this, and if empirical evidence continues to support theories on suicide that include social variables as an essential part, then it would not hurt to include these, not only in clinical practice treatment programs, but also in suicide prevention programs. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Espinosa-Salido, P., Perez Nieto, M. A., Baca-García, E., & Provencio Ortega, M. (2020). Systematic review of the indirect relationships of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in suicide. Clínica y Salud, 32(1), 29-36. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a27 Funding: Funding for this study was provided by Centro de Enseñanza Universitaria SEK S.A., Calle Castillo de Alarcón, Urbanización Villafranca del Castillo. References |

Cite this article as: Espinosa-Salido, P., Perez, M. A., Baca-García, E., and Ortega, M. P. (2021). Systematic Review of the Indirect Relationships of Thwarted Belongingness and Perceived Burdensomeness in Suicide. ClĂnica y Salud, 32(1), 29 - 36. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2020a27

esp.salido@gmail.com Correspondence: esp.salido@gmail.com (P. Espinosa-Salido)Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS