Social Stigma Towards Mental Health Problems in Spain: A Systematic Review

[El estigma social hacia los problemas de salud mental en España: una revisión sistemática]

Sara Zamorano1, María Sáez-Alonso1, Clara González-Sanguino2, and Manuel Muñoz1

1Complutense University of Madrid, Spain; 2University of Valladolid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a5

Received 6 June 2022, Accepted 17 January 2022

Abstract

Introduction: This review focuses on social stigma associated with mental health problems in Spain in recent years. Method: A systematic search was conducted in SCOPUS, PsycInfo and Pubmed from 2010 to 2021. Twenty-six articles met inclusion criteria, and their quality was assessed following the STROBE-checklist. Results: In the Spanish population, stigmatising dynamics are detected in three dimensions of stigma: cognitive (beliefs of dangerousness, unpredictability, irresponsibility); emotional (prejudices and emotions of fear, anger, blaming for the psychological problem); and behavioural (discriminatory behaviours, avoidance, coercion). The results also show significant levels of stigma among health professionals. In contrast, those who have contact with mental health problems, or are trained in mental health, tend to show lower stigma. Conclusions: Longitudinal studies with rigorous methodology are needed to access strong empirical evidence in this field. Contact and education may be relevant factors in programming interventions, both in the general population and in health professionals.

Resumen

Introducción: Esta revisión se centra en el estigma social asociado a los problemas de salud mental en España en los últimos años. Método: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en SCOPUS, PsycInfo y Pubmed de 2010 a 2021. Veintiséis artículos cumplían los criterios de inclusión y su calidad se evaluó siguiendo la lista de comprobación STROBE. Resultados. En la población española se detectan dinámicas estigmatizadoras en tres dimensiones del estigma: cognitiva (creencias de peligrosidad, imprevisibilidad, irresponsabilidad), emocional (prejuicios y emociones de miedo, ira, culpabilización del problema psicológico) y conductual (conductas discriminatorias, evitación, coacción). Los resultados también muestran niveles significativos de estigma entre los profesionales sanitarios. Por el contrario, aquellas personas que tienen contacto con problemas de salud mental o están formadas en el tema tienden a mostrar un menor estigma. Conclusiones: Se necesitan estudios longitudinales con una metodología rigurosa para acceder a evidencia empírica sólida en este campo. El contacto y la educación pueden ser factores relevantes a la hora de programar intervenciones antiestigma, tanto en la población general como en los profesionales sanitarios.

Palabras clave

Estigma, Actitudes, Discriminaci├│n, Prejuicios, Salud mentalKeywords

Stigma, Attitudes, Discrimination, Prejudices, Mental healthCite this article as: Zamorano, S., Sáez-Alonso, M., González-Sanguino, C., & Muñoz, M. (2023). Social Stigma Towards Mental Health Problems in Spain: A Systematic Review. Cl├şnica y Salud, 34(1), 23 - 34. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a5

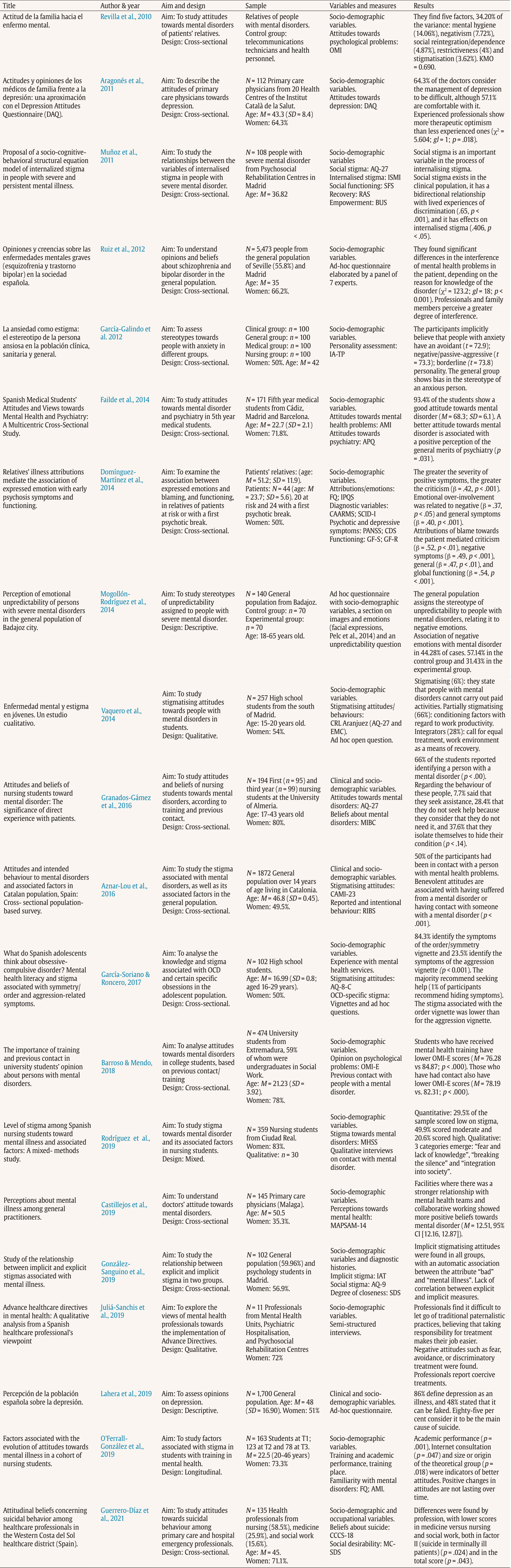

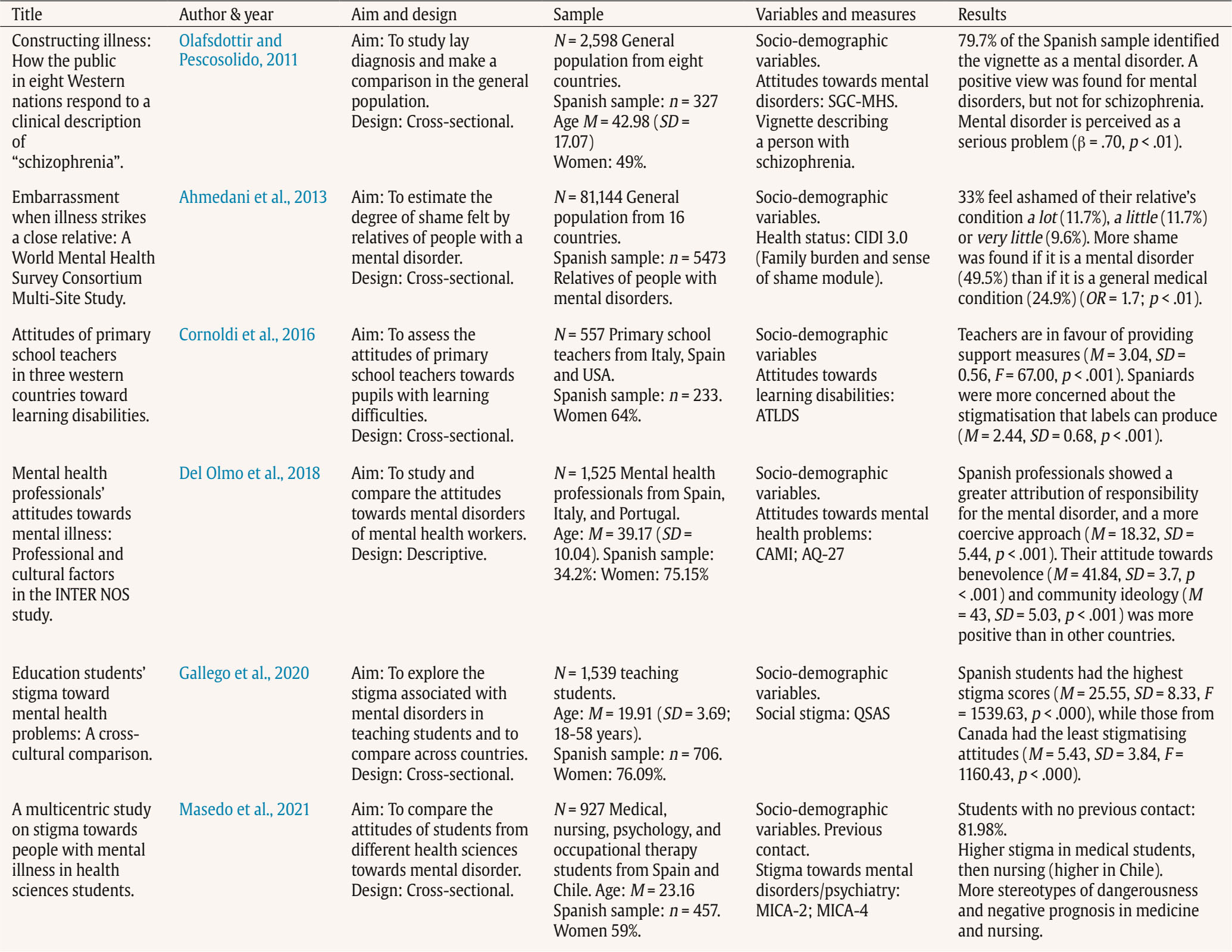

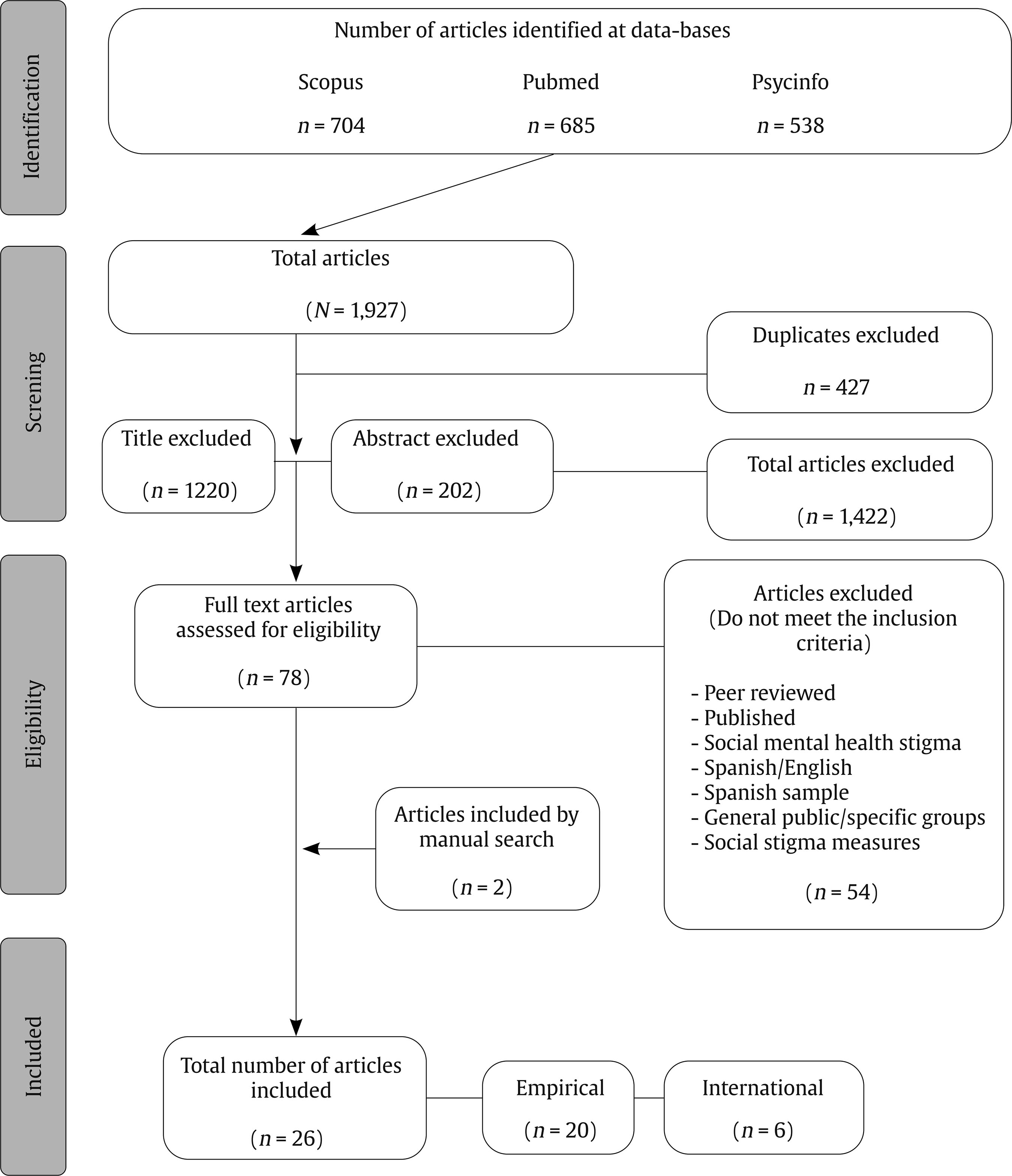

Correspondence: sarazamo@ucm.es (S. Zamorano Castellanos).Stigma towards psychological problems is an ongoing issue that negatively affects people living with these circumstances, diminishing their quality of life and well-being. This stigma can even aggravate the symptomatology itself and hinder the recovery process (Corrigan et al., 2012; Del Rosal et al., 2020; Livingston & Boyd, 2010). The Mental Illness Stigma Framework (MISF) (Fox et al., 2018) conceptualises stigma towards mental health problems from two perspectives: that of the person who stigmatises and that of the stigmatised person. The conceptual cores of the stigmatiser, which make up social stigma, refer to stereotypes (cognitive dimension), prejudice (affective dimension), and discrimination (behavioural dimension) (Corrigan & Watson, 2002). Therefore, social stigma occurs when the general population, based on their shared beliefs about the illness and the negative emotions it generates, acts in a discriminatory manner towards people with psychological problems. From the perspective of the stigmatised person, meanwhile, there is internalised stigma, resulting from the internalisation and self-application of these prejudices and stereotypes, as well as from the discriminatory experiences lived (Livingston & Boyd, 2010). Finally, as a common element in both prisms, there is structural stigma, which limits the opportunities of people with psychological problems at institutional, political and legal levels (Fox et al., 2018). In recent years, societal progress and changes in the healthcare model in psychiatry, together with the impact of recent events such as the Covid-19 pandemic, have increased the importance of the stigma associated with mental health problems, leading to an escalation of research into the construct. Internationally, there are several systematic reviews on the subject from the United States (Parcesepe & Cabassa, 2013), Japan (Ando et al., 2013), India (Gaiha et al., 2020), and Greece (Tzouvara et al., 2016). In all these studies, the authors emphasise that stigma towards mental health problems is a variable that is present and widespread in different societies. These societies share beliefs of dangerousness, incompetence, or guilt towards people with psychological problems, which are transformed into discrimination, a desire for greater social distance and authoritarianism (Parcesepe & Cabassa, 2013; Tzouvara et al., 2016). Moreover, this stigma tends to be higher towards severe mental disorders (Angermeyer et al., 2013), as well as in people who have not experienced or have no direct contact with psychological problems (Ilic et al., 2014). In Spain, the first relevant investigations on the field emerged at the end of the 1990s with the World Psychiatric Organisation’s team “Open the doors”, which revealed the frequent discrimination and stigma experienced by affected people and their families (Kadri & Sartorius, 2005). Later on, in the early 2000s, it is worth mentioning a study carried out in the Madrid region (Crespo et al., 2008), the results of which reveal the existence of stigmatising attitudes both in the general population and in groups of relatives, professionals, and the media. From 2010 onwards, studies on social stigma in Spain began to become more frequent, with the research studies carried out in Catalonia in the Obertament campaign (https://obertament.org/es) standing out for their importance. This 2013 campaign included stigma towards mental disorders as a variable in the Health Survey of Catalonia (ESCA), with a representative sample of its population (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016). However, despite the existence of relevant research on the subject, there is currently no review in Spain that analyses and draws conclusions on the state of research on the social stigma associated with psychological problems. Considering the above, the aim of this paper is to carry out a systematic review of the social stigma of mental health problems in Spain from 2010 to the present day in 2022, identifying the main types of studies and conclusions drawn from them. Sources and Search Strategies To identify papers, we searched the SCOPUS, PsycINFO, and Pubmed databases from October 2021 to January 2022. The search was limited to the last decade, between January 2010 and December 2021. The search strategy in the databases included terms such as “mental health”, “mental illness”, various mental health diagnosis terms, “public opinion”, “belief*”, “prejudice*”, “stereotype*”, “Spain”. The full search strategy can be consulted in the supplementary material (Appendix A). Study Selection Criteria In order to meet scientific quality criteria, studies had to be: 1) peer-reviewed, 2) published in scientific journals, 3) focussed on social stigma associated with psychological problems, 4) in Spanish or English between 2010-2021, 5) carried out with Spanish samples (or residents in Spain, 6) with general population and specific groups, and 7) with measures of social stigma (qualitative or quantitative). The articles were excluded if they 1) did not address social stigma, 2) did not have extractable data, 3) were not peer-reviewed, 4) were not empirical scientific articles, 5) were reviews or meta-analyses, and finally, 6) articles on stigma assessment, and 7) stigma reduction programmes or actions were eliminated as they were of sufficient importance and number of studies to construct an independent review. Data Extraction and Methodological Quality Measurement The study selection process was carried out following the recommendations of the PRISMA guidelines (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis) (Page et al., 2021). The protocol for the review was pre-registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022307511). A total of 1,927 articles were found in the databases. First, articles with irrelevant titles were rejected. After this, abstracts were read and papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria were eliminated. Finally, the full reading of articles was carried out, reviewing a total of 78 papers. This selection was carried out independently by two authors, and, in the case of any discrepancies, these were discussed between them and with a third author. In total, 26 articles were included for review. The full process of article selection can be found in Figure 1. In order to provide a better understanding of the results and their provenance, the studies were divided into two categories: international studies and national studies. The extracted data were synthesised by title, year, objective and methodological design, sample, variables and measures, and results. The methodological quality of the research, the design characteristics and statistical data were assessed. Characteristics of the Studies Twenty national articles with quantitative methodology were found (see Table 1), two of them with mixed designs (Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019; Vaquero et al., 2014). In addition, six international quantitative, multicentre articles were identified (Ahmedani et al., 2013; Cornoldi et al., 2018; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Gallego et al., 2020; Masedo et al., 2021; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011). Most of the studies included are cross-sectional, with a total of 25 articles, and there is only one paper with a longitudinal methodology (O’Ferrall-González et al., 2020). Sample sizes range from 11 (Juliá-Sanchis et al., 2019) to 5,473 (Ruiz et al., 2012) people. The mean percentage of women in the articles that report this data is 61.3%, and there are four papers that do not report gender percentages (Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Muñoz et al., 2011; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011; Revilla et al., 2010). Table 1 Characteristics and Results of National Studies   Note. OMI & OMI-E = Opinion about Mental Illness (y version Española) (Struening & Cohen, 1963; Fresán et al., 2012); DAQ = Depression Attitudes Questionnaire (Botega et al., 1992); AMI = Attitudes to Mental Illness Questionnaire (Singh et al., 1998); APQ = Attitudes towards Psychiatry Questionnaire (Balon et al., 1999); AQ-27 = Attribution Questionnaire of Mental Health (Corrigan et al., 2003); CAMI-23 = Community Attitudes Towards the Mentally (Taylor & Dear, 1981); RIBS = Reported and Intended Behaviour Scale (Evans-Lacko et al., 2011; Rubio-Valera et al., 2016); MHSS = Mental Health Stigma Scale (Varas-Díaz et al., 2016); MAPSAM-14 = Primary Care Physicians and Mental Health Questionnaire (Kustner et al., 2018); IAT = Implicit Association Test (Greenwald et al., 1998); AQ-9 = Attribution Questionnaire-9 (Corrigan et al., 2003; Muñoz et al., 2015); SDS = Social Distance Scale (Link et al., 1987; Senra-Rivera et al., 2008); AQ-8-C = Attribution Questionnaire for Children (Corrigan, 2012; Muñoz et al., 2009); ISMI = Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (Ritsher et al., 2003); CCCS-18 = Questionnaire on Attitudinal Beliefs Regarding Suicidal Behavior (Ruiz et al., 2005); MC–SDS = Marlowe–Crowne Social Desirability Scale (Crowne & Marlowe, 1964); IA-TP = Inventario de Adjetivos para la evaluación de los Trastornos de Personalidad (Tous et al., 2005); SFS = Social Functioning Scale (Birchwood et al., 1990; Vázquez & Jiménez., 2000); RAS = Recovery Assessment Scale. (Corrigan et al., 1999); BUS = Boston University Scale (Rogers et al., 1997); FQ = Family Questionnaire (Wiedemann et al., 2002); IPQS = Illness Perception Questionnaire for Schizophrenia (Lobban et al., 2005); PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndromes Scale (Kay et al., 1987); CDS = Calgary Depression Scale (Addington et al., 1990); GF-S & GF-R = Social and Role Global Functioning Scales (Cornblatt et al., 2007); CAARMS = Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States (Yung et al., 2005); SCID-I = Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis-I Disorders (First et al., 1996); EMC = Cuestionario de Conocimiento de la Enfermedad Mental (Muñoz et al., 2009); MIBC = Mental Illness Beliefs Questionnaire (Meyer et al., 1985). Regarding the participants, most articles deal with samples of the general population (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; García-Galindo et al., 2012; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Lahera et al., 2019; Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011; Ruiz et al., 2012), nursing or medical health professionals (Aragonès et al., 2011; Castillejos-Anguiano et al., 2019; García-Galindo et al., 2012; Guerrero-Díaz et al., 2021), mental health professionals (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019) or university students in health degrees (Failde et al., 2014; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Masedo et al., 2021; O’Ferrall-González et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019) or other degrees (Barroso-Hurtado & Mendo-Lázaro, 2018; Gallego et al., 2020). There are also studies with family members of people with a diagnosis (Ahmedani et al., 2013; Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2014; Revilla et al., 2010) and people with mental health problems (Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2014; García-Galindo et al., 2012; Muñoz et al., 2011). The majority of papers assess the stigma of severe mental disorders (Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Muñoz et al., 2011; Vaquero et al., 2015), such as psychotic disorders (Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2014; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011; Revilla et al., 2010; Ruiz et al., 2012) or bipolar disorder (Ruiz et al., 2012), as well as substance addictions (Ahmedani et al., 2013; Revilla et al., 2010) or suicidal behaviour (Guerrero-Díaz et al., 2021). Only four studies have assessed the stigma of anxiety disorders (García-Galindo et al., 2012; García-Soriano & Roncero, 2017) or depression (Aragonès et al., 2011; Lahera et al., 2019). Also noteworthy is the great heterogeneity of the assessment instruments used to measure stigma, such as scales, questionnaires, and indexes, as well as ad hoc questions and vignettes. The most commonly used instruments are the Attribution Questionnaire-27 (Corrigan et al., 2003), reported in six studies (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; García-Soriano & Roncero, 2017; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Muñoz et al., 2011; Vaquero et al., 2015), and the Community Attitudes Towards the Mentally Ill Scale (Taylor & Dear, 1981), employed in two papers (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019). Few articles are found related to the more behavioural dimension of stigma (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Vaquero et al., 2015). Socio-demographic Variables, and Social Stigma In relation to gender, numerous studies report finding no significant differences between women and men (Ahmedani et al., 2013; Castillejos-Anguiano et al., 2019; Cornoldi et al., 2018; Failde et al., 2014; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Revilla et al., 2010; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019), while other papers report finding lower levels of stigma in women (Gallego et al., 2020; García-Soriano & Roncero, 2017; Masedo et al., 2021), including lower authoritarianism scores (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016). Furthermore, women recognise psychological problems as illnesses to a greater extent than men (Lahera et al., 2019; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011). With regard to the age of participants, most studies which report its relationship with social stigma find positive interactions, i.e., the older the age, the higher the level of stigma (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Lahera et al., 2019; Masedo et al., 2021; Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Revilla et al., 2010). Regarding educational level, one study states that the attribution of unpredictability to people with psychological problems is lower in those with higher education (Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014). Another paper suggests an association between lower education and more benevolent treatment, while higher education correlates with more restrictive and less authoritarian attitudes (Revilla et al., 2010). Only one study provides data on the relationship between social class and stigma (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016), stating that levels of stigma are lower in higher social classes, but only in reference to intentional behaviour. As for the provenance of the international studies, they include data from Europe (Ahmedani et al., 2013; Cornoldi et al., 2018; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Gallego et al., 2020; Masedo et al., 2021; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011), America (Ahmedani et al., 2013; Cornoldi et al., 2018; Gallego et al., 2020; Masedo et al., 2021; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011), Africa, Asia, and Oceania (Ahmedani et al., 2013). Dimensions of Stigma towards Mental Health Problems Beliefs and Stereotypes (Cognitive) Multiple studies highlight the presence of stereotypes of unpredictability and instability among the samples (Lahera et al., 2019; Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Vaquero et al., 2015), with people with mental health problems being considered dangerous (Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019; Ruiz et al., 2012; Vaquero et al., 2015) and aggressive (García-Galindo et al., 2012; Ruiz et al., 2012). In addition, both the general population and health professionals report beliefs of incapacity and lack of personal autonomy, low responsibility and work limitations towards people with psychological problems (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; Lahera et al., 2019; Vaquero et al., 2015). In terms of levels of stigmatisation, only two papers compare stigma in different populations, finding less stigmatising beliefs in health professionals than in the general population (García-Galindo et al., 2012) or family members (Revilla et al., 2010). There are also pessimistic beliefs about the usefulness of therapy and the chronicity of the mental health problems in the clinical (Muñoz et al., 2011), general (Ruiz et al., 2012), and health professional populations (Granados-Gámez et al., 2016). Regarding treatments, the general population perceives psychological treatment as effective, in conjunction with pharmacological treatment, which should be continuous, chronic, and even in the absence of symptoms (Lahera et al., 2019; Ruiz et al., 2012). In addition, biologistic beliefs regarding the cause of mental health problems are found in both medical and nursing professionals (Aragonès et al., 2011; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016), as well as in the general population (García-Soriano & Roncero, 2017; Olafsdottir & Pescosolido, 2011; Ruiz et al., 2012). Attitudes and Prejudices (Emotional) In general, stigmatising attitudes towards people with mental health problems, associated with negative emotions, are found. This occurs in the general population and in patients’ relatives (Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2014; García-Galindo et al., 2012; Mogollón-Rodríguez et al., 2014; Muñoz et al., 2011; Revilla et al., 2010), as well as in health professionals (Aragonès et al., 2011; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019). Another finding related to stigma towards psychological problems is provided by Failde et al. (2014), who report that psychiatry students perceive little social support, and that their families and friends urge them to study other medical specialties. However, various studies reflect positive attitudes among health professionals towards their own mental health problems (Failde et al., 2014) and towards the treatment of these problems, in particular depression (Aragonès et al., 2011). Those with more positive attitudes towards psychiatry tend to be more likely to recommend help-seeking, and are more comfortable with patients with psychological problems (Failde et al., 2014). In relation to decision-making about their treatment by people with mental health problems, studies reflect authoritarian, coercive, and restrictive attitudes towards them (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Revilla et al., 2010). Regarding specific attitudes and emotions, fear (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Muñoz et al., 2011; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019), anger, responsibility for the mental health problem associated with the patient, and pity (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016) stand out. In contrast, some studies show favourable attitudes towards social reintegration and help for people with psychological problems (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Revilla et al., 2010), as well as support for the mental health of the community and benevolence (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019). Discrimination (Behavioural) The area of behavioural discrimination seems to be the least studied. The results point to significant levels of avoidance and social distance towards people with mental health problems, both by the general population (Gallego et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Muñoz et al., 2011) and healthcare staff (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Granados-Gámez et al., 2016). In contrast, one study shows a moderate-high intention of the Catalan population to have contact with people with psychological problems in the future (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016). Another paper mentions the stigmatisation and socio-occupational marginalisation of people with mental health problems, reporting that they receive inadequate treatment in healthcare settings (Ruiz et al., 2012). Overprotective behaviours are also detected, especially towards people with negative symptomatology (Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2014). Contact with Mental Health Problems, and Social Stigma Closeness and Own Experience In terms of closeness to people with mental health problems, studies report a tendency to stigmatise less in the case of those who have had some kind of contact with mental health. In the general population, knowing someone with psychological problems is associated with better attitudes, lower levels of authoritarianism, less stereotyping, and less desire for social distance (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016; Barroso-Hurtado & Mendo-Lázaro, 2018). In a study among high school students, those who had no previous contact showed significantly higher scores on fear and segregation attitudes (García-Soriano & Roncero, 2017). In reference to health professionals, several papers show that those who report some contact with mental health problems exhibit more favourable attitudes and beliefs towards them (Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Guerrero-Díaz et al., 2021; Masedo et al., 2021). Lastly, the data suggest that those who have directly experienced a mental health problem have lower levels of authoritarianism (Aznar-Lou et al., 2016), greater confidence in their own abilities (Ruiz et al., 2012), and more positive perceptions of mental health than those who have not (García-Galindo et al., 2012). Relatives of People with Mental Health Problems The review of papers highlights another means of contact with mental health problems, that of family members. Some data suggest that those with a family member with psychological problems are less stigmatising than the general population. In particular, they exhibit less limiting beliefs (Ruiz et al., 2012), more involvement and information about mental health (Revilla et al., 2010), less social distance (González-Sanguino et al., 2019), and positive attitudes towards their family member’s integration into society (Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019). However, the only study assessing implicit or automatic stigma finds higher levels of implicit stigma in relatives than in the general sample (González-Sanguino et al., 2019). As specific variables, relatives of people with mental health problems show concern, low confidence in recovery, benevolent attitudes, and negative judgements about their relative’s ability to cope on their own (Revilla et al., 2010). Other factors reported in the literature include blaming the family member for the psychological problem, controlling behaviour, coercion, over-involvement (Domínguez-Martínez et al., 2014), and shame (Ahmedani et al., 2013). Moreover, some family members perceive their loved one’s mental health problems as a major family burden more strongly than the general population (Ruiz et al., 2012). Knowledge and Training on Mental Health Problems and Social Stigma Another factor that emerges from the review is knowledge about psychological problems. Of particular note is the lack of information on mental health in the general population found in some studies, where it is pointed out that people do not recognise symptoms or misidentify them with other psychological problems (García-Soriano & Roncero, 2017; Ruiz et al., 2012). Health Students and Health Professionals With regard to students in health care degrees, there is also data on social stigma depending on training and knowledge about mental health. In particular, medical students seem to show higher levels of stigma than nursing or psychology students (Masedo et al., 2021), and they perceive psychiatry as the most reviled medical discipline (Failde et al., 2014). Nursing students also show stigmatising attitudes (Granados-Gámez et al., 2016; Masedo et al., 2021; O’Ferrall-González et al., 2020; Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019), with high scores on responsibility for illness, helping, pity, coercion and avoidance (Granados-Gámez et al., 2016), and moderate to high scores on stigma in 70% of the sample (Rodríguez-Almagro et al., 2019). Psychology or social work students display the lowest levels of stigma (González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Masedo et al., 2021), showing less desire for social distance and fewer stigmatising attitudes. In addition, several studies assess stigma among health professionals, finding, in general, stigmatising attitudes towards mental health problems (Aragonès et al., 2011; Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019; Ruiz et al., 2012). A 2011 study found that 20.5% of family physicians believe that depression is the way people with low resilience respond to adversity (Aragonès et al., 2011). Another paper notes that healthcare professionals perceive severe mental health problems as illnesses that cause great family overload (Ruiz et al., 2012). In a different study, researchers found higher levels of stigma towards mental health problems in a group of nursing assistants, compared to general practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social therapists (Del Olmo-Romero et al., 2019). When assessing the level of stigma of medical, nursing, and social work professionals towards suicide, stigmatising behaviours related to this problem are found (Guerrero Díaz et al., 2021). It is noteworthy that some of these studies report lower levels of stigma in the healthcare professional group compared to the general population (García-Galindo et al., 2012; Revilla et al., 2010), finding lower levels of authoritarianism and restriction. It is also reported that those primary care physicians who collaborate more closely with mental health professionals have more positive beliefs (Castillejos-Anguiano et al., 2019). The results presented in this section can be found in Tables 1 and 2. Table 2 Characteristics and Results of International Studies   Note. CIDI = World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler & Ustün, 2004); ATLDS = Cuestionario de actitudes hacia las dificultades de aprendizaje (Cornoldi, 2012); CAMI-23 = Community Attitudes Towards the Mentally (Taylor & Dear, 1981); AQ-27 = Attribution Questionnaire of Mental Health (Corrigan et al., 2003); QSAS = Questionnaire on Students’ Attitudes toward Schizophrenia (Schulze et al., 2003); MICA-2 & MICA 4 = Mental Illness Clinicians’ Attitudes (Kassan et al., 2010; Gabbidon et al., 2013); SGC-MHS = Vignette describing a person with schizofhrenia (Pescosolido et al., 2008). Quality of Included Studies Study quality was assessed according to the STROBE (Elm et al., 2007) checklist for cross-sectional studies. The aim of the STROBE Statement is to establish a checklist of elements that should be included in this type of research. The assessment of the papers using this checklist can be found as supplementary material to this review. The findings obtained in the present review reveal the state of research on the stigma associated with mental health problems in Spain in the last decade. In terms of socio-demographic variables, the data are consistent with previous investigations, finding mixed outcomes in terms of gender and higher levels of stigma in older people (Gaiha et al., 2020; Tanaka et al., 2004; Trevillion et al., 2012). Furthermore, most of the studies are quantitative and cross-sectional, and there is a lack of international research in cooperation with Spain involving African or Asian countries, not only carried out in Europe or the USA with a Western vision. It should also be noted that the majority of studies are limited to severe mental disorders, depression or mental health in general, which is consistent with the lack of studies in the literature on specific mental health problems such as personality disorders, eating disorders, or neurodevelopmental disorders (Muñoz et al., 2009). Lastly, it is necessary to comment that, although the sample sizes in most of the studies are sufficient, none of the studies included a representative sample of the Spanish population or were conducted on a large scale throughout the country. Among the most widespread beliefs are the assumption of dangerousness and unpredictability towards people with mental health problems. On an emotional level, emotions such as fear, anger, or guilt are frequent. All these data are consistent with previous literature gathered in reviews from other countries (Gaiha et al., 2020; Parcesepe & Cabassa, 2013). Regarding behavioural discrimination, restrictive and social distancing tendencies are found in the Spanish population (Gallego et al., 2020; González-Sanguino et al., 2019; Muñoz et al., 2011), as in other countries such as Greece (Tzouvara et al., 2016) or Japan (Ando et al., 2013). However, there is a notable lack of research studies focusing on the behavioural dimension of stigma and on the behavioural consequences of the construct, such as barriers to access to employment or housing, or direct social discrimination. In addition, the outcomes of this review suggest that social stigma is lower in people who have training or contact with mental health problems. Previous literature estimates that contact is associated with fewer stereotypes, better attitudes, and less stigmatising behaviour. Also, if the contact is due to having experienced a psychological problem, it is associated with more positive perceptions than the rest of the population (Heim et al., 2020; Martínez-Martínez et al., 2019; Morgan et al., 2018; Thornicroft et al., 2016). Thus, there is research that exposes contact with people with psychological problems as the most effective tool to reduce stigma, together with training (Eiroa-Orosa et al., 2021; Manzanera et al., 2018). Further outcomes derived from this review are the existence of stigmatising attitudes towards psychological problems in health professionals. In particular, the data suggest that there is more stigma in nursing and general medicine than in psychiatry and other health care settings. Stigma in these environments results in poorer medical care, masking of physical symptoms, and higher mortality (Henderson et al., 2014; Thornicroft, 2011). This stigma may be due to the fact that these disciplines do not have regular contact with mental health problems. These data are consistent with previous studies that have found significant levels of stigma in the healthcare population (Carrara et al., 2019; Henderson et al., 2014; Rojas Vistorte et al., 2018). There are various limitations to the present review. Firstly, there is a lack of consensus on the measurement of stigma, with a large variability of instruments. This leads to greater complexity in gathering and integrating information, and to problems in comparing it. This presents difficulties for a meta-analysis, as the data are very heterogeneous and effect sizes are not reported in the studies. With regard to the methodology of the studies, most of the articles are cross-sectional and descriptive, which limits the possibility of studying the effects of the variables over time, and in no case do they report causality. In addition, the review process is limited by the language bias of including articles only in English and Spanish, as well as by publication bias. Finally, although the most important databases were searched, it is possible that some studies from other databases were not included. Evidence gathered in this review suggests that, although research on mental health in Spain has increased in the last decade, it is still insufficient when it comes to evaluating the variables related to social stigma and its interrelation with internalised or structural stigma. It is concluded that mental health stigma is an ongoing problem in our country nowadays, for the reduction of which new lines of research, intervention, and structural changes are still required. The results of this review can lay some foundations for understanding the functioning of stigma towards mental health problems, considering that this stigma is a barrier that adds suffering and burden to people with a psychological problem. As future implications, firstly, it seems necessary to invest in actions to reduce stigma, both in the general population and in the healthcare community, which is particularly sensitive due to the type of relationship it has with mental health problems. Moreover, the data suggest that strategies focused on contact and education can be effective in reducing stigma, and thus improve the quality of life of people with mental health problems. Finally, it seems necessary to develop longitudinal studies with representative samples, including instruments that assess stigma in its complexity together with its consequences for those affected by stigma. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Zamorano, S., Sáez-Alonso, M., González-Sanguino, C., & Muñoz, M. (2023). Social stigma towards mental health problems in Spain: A systematic review. Clínica y Salud, 34(1), 23-34. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a5 References Appendix Search Equation (AB,TI,IF(“mental health” OR “mental disorder” OR “mental illness” OR schizo* OR psychosis OR autism OR depressi* OR anxiety OR bipolar OR “obsessive compulsive” OR obsessive OR compulsive OR OCD OR dementia OR personality OR post-traumatic OR posttraumatic OR PTSD OR postraumatic OR “emotional disorder” OR adaptative) AND AB,TI,IF(stigma* OR attitude* OR discrimination OR belief* OR prejudice* OR “public opinion” OR stereotype*) AND AB,TI,IF(spain) AND lo.Exact(“Spain”)) ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “mental health” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “mental disorder” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “mental illness” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( schizo* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( psychosis ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( autism ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( depressi* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( anxiety ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( bipolar ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “obsessive compulsive disorder” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( obsessive ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( compulsive ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ocd ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( dementia ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( personalit) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( post-traumatic ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( posttraumatic ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( postraumatic ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ptsd ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “emotional disorder” ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( adaptative ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( attitude* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( stigma* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( belief* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( stereotype* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( prejudice* ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( discrimination ) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “public opinion” ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( spain ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( AFFILCOUNTRY , “Spain” ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , “English” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , “Spanish” ) ) (“mental health”[Title/Abstract] OR “mental disorder”[Title/Abstract] OR “mental illness”[Title/Abstract] OR “schizo*”[Title/Abstract] OR “psychosis”[Title/Abstract] OR “autism”[Title/Abstract] OR “depressi*”[Title/Abstract] OR “anxiety”[Title/Abstract] OR “bipolar”[Title/Abstract] OR “obsessive compulsive”[Title/Abstract] OR “obssesive”[Title/Abstract] OR “compulsive”[All Fields] OR “OCD”[Title/Abstract] OR “dementia”[Title/Abstract] OR “personality”[Title/Abstract] OR “post-traumatic”[Title/Abstract] OR “posttraumatic”[Title/Abstract] OR “PTSD”[Title/Abstract] OR “postraumatic”[Title/Abstract]) OR “emotional disorder”[Title/Abstract] OR “adaptative”[Title/Abstract] AND “attitude*”[Title/Abstract]) OR “stigma*”[Title/Abstract] OR “belief*”[Title/Abstract] OR “discrimination”[Title/Abstract] OR “prejudice*”[Title/Abstract] OR “stereotype*”[Title/Abstract] OR “public opinion”[Title/Abstract]) AND “spain”[Title/Abstract] AND (“humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (“english”[Language] OR “spanish”[Language])) AND (“humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (“english”[Language] OR “spanish”[Language])) AND (“humans”[MeSH Terms] AND (“english”[Language] OR “spanish”[Language]))) AND ((humans[Filter]) AND (english[Filter] OR spanish[Filter])) |

Cite this article as: Zamorano, S., Sáez-Alonso, M., González-Sanguino, C., & Muñoz, M. (2023). Social Stigma Towards Mental Health Problems in Spain: A Systematic Review. Cl├şnica y Salud, 34(1), 23 - 34. https://doi.org/10.5093/clysa2023a5

Correspondence: sarazamo@ucm.es (S. Zamorano Castellanos).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS