Considering the Effect of Sexism on Psychological Intimate Partner Violence: A Study with Imprisoned Men

[El efecto del sexismo en la violencia psicolĂłgica de pareja: un estudio con reclusos]

Joel Juarros-Basterretxea1, Nickola Overall2, Juan Herrero1, Francisco J. Rodríguez-Díaz1, and 3

1University of Oviedo, Spain; 2The University of Auckland, New Zealand; 3Andrés Bello University, Chile

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a1

Received 20 September 2018, Accepted 12 September 2019

Abstract

Psychological intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most prevalent form of IPV and is often thought to precede physical IPV. However, psychological IPV often occurs independently of other forms of IPV, and it can often emerge during routine relationship interactions. Using data from imprisoned male offenders we investigate the effect of hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes on psychological IPV and the hypothesized mediating role of positive attitudes toward IPV and this effect when accounting for broader risk factors at the levels of community (social disorder), family-of-origin (conflictive climate in family of origin), and personality (antisocial personality traits) variables. The sample involved 196 male inmates of the Penitentiary Center of Villabona (Asturias, Spain). Structural equation models result showed significant total, direct and indirect effect of hostile sexism on psychological IPV, but not of benevolent sexism. When individual, family-of-origin, and community variables were considered, however, hostile sexism showed only an indirect effect on psychological IPV via positive attitudes toward abuse. These results are discussed in light of the debate of the role of sexist attitudes in the psychological IPV explanation when broader models are considered.

Resumen

La violencia de pareja (VP) psicológica es la forma más prevalente de VP y habitualmente suele preceder a la VP física. Sin embargo, la VP psicológica ocurre a menudo independientemente de otras formas de VP y puede darse en interacciones rutinarias con la pareja. Utilizando datos de hombres recluidos en prisión, hemos investigado el efecto del sexismo hostil y benevolente sobre la VP psicológica, así como el rol mediador de las actitudes positivas hacia el abuso de la pareja. Hemos investigado también ese efecto cuando están presentes otros factores de riesgo de VP psicológica señalados en la literatura reciente están presentes: comunidad (desorden social), familia de origen (clima conflictivo en la familia de origen) y factores individuales (rasgos de personalidad antisocial). Participaron en el estudio 196 hombres internos en el Centro Penitenciario de Villabona (Asturias, España). Los resultados de los modelos de ecuaciones estructurales estimados indican un efecto total, directo e indirecto significativo del sexismo hostil sobre la VP psicológica, pero no del sexismo benevolente. Cuando las variables de la comunidad, la familia de origen y factores individuales se incorporaron al modelo únicamente el efecto indirecto del sexismo hostil a través de las actitudes positivas hacia el abuso siguió siendo significativo. Los resultados se discuten en relación con el debate sobre el rol de las actitudes sexistas sobre la VP psicológica en el marco de modelos más generales de violencia.

Keywords

Intimate partner violence, Psychological aggression, Ecological framework, Sexist attitudes, InmatesPalabras clave

Violencia de pareja, AgresiĂłn psicolĂłgica, Marco ecolĂłgico, Actitudes sexistas, PresosCite this article as: Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Overall, N., Herrero, J., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J. (2019). Considering the Effect of Sexism on Psychological Intimate Partner Violence: A Study with Imprisoned Men. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11(2), 61 - 69. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a1

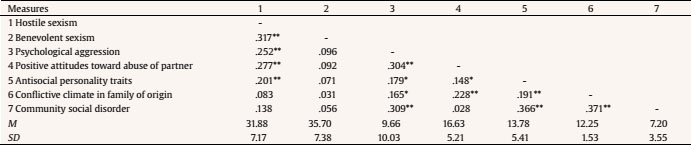

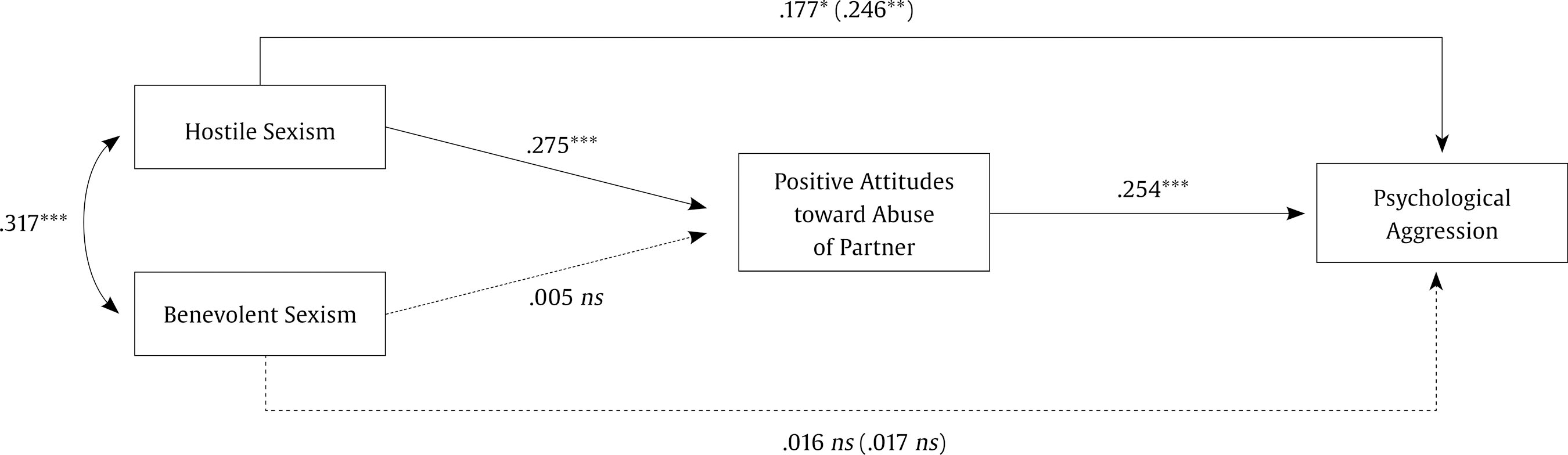

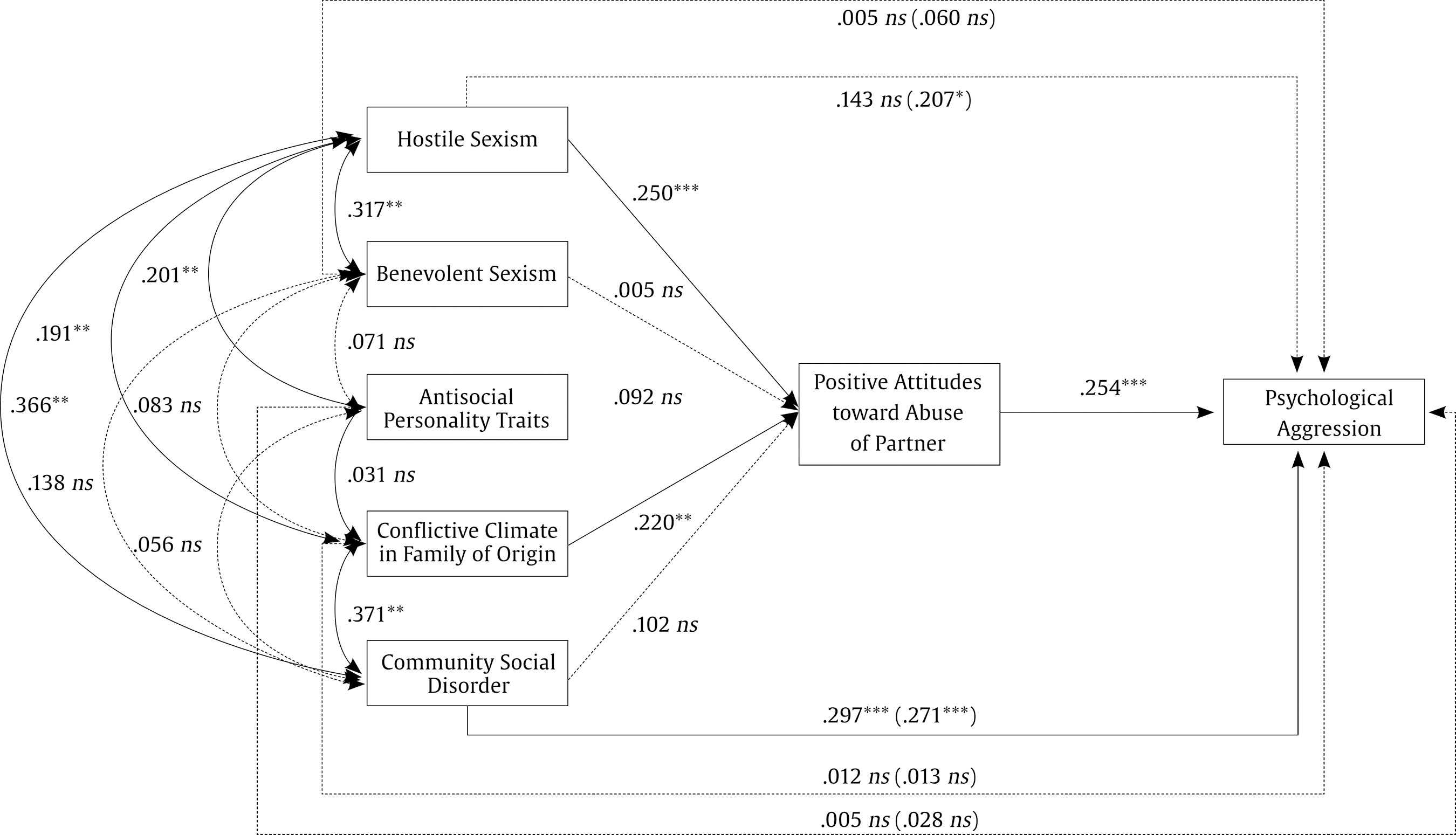

juarrosjoel@uniovi.es Correspondence: juarrosjoel@uniovi.es (J. Juarros-Basterretxea).Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women is a widespread phenomenon around the world with harmful consequences to its victims. The most prevalent form of IPV (Salis, Salwen, & O'Leary, 2014) is psychological IPV, which involves insults, humiliation, and control behaviors that produce psychological harm (Arriaga & Schkeryantz, 2015; Hamby & Sugarman, 1999; Salis et al., 2014). Psychological IPV is often thought to precede, and therefore be an important risk factor of, physical IPV (Murphy & O´Leary, 1989; Salis et al., 2014). However, psychological IPV often occurs independently of other forms of IPV (Hamby & Sugarman, 1999), such as physical and sexual IPV, and it can often emerge during routine relationship interactions (Cross, Overall, Hammond, & Fletcher, 2017). Given the prevalence and harm it can cause, understanding the predictors of psychological IPV is pivotal. Despite its importance, studies of psychological IPV often do not include the same kind of rigorous approach to understanding mediating variables or discriminating across potentially competing risk factors as is commonly done in studies of physical IPV. In the current research, we focus on sexist attitudes as an important risk factor implicated in psychological IPV, and we identify a key mediating variable of the links between sexist attitudes and psychological IPV that should enable more accurate targets for intervention—positive attitudes toward abuse of intimate partners. Also, we only adopt an ecological perspective common to understanding physical violence to assess and model control variables relative to community, family of origin, and personality in order to specify the total, direct, and indirect effects of sexist attitudes on psychological aggression. In doing so, this study represents the first examination of whether sexist attitudes represent effects independent of broader social, familiar, and individual risk factors for IPV. Sexist Attitudes, Acceptance of IPV, and IPV Perpetration One important attitudinal risk factor for IPV against women is men's sexist attitudes toward women. However, sexism is a peculiar type of prejudice because competitive attitudes toward women as outgroup members exist alongside heterosexual men's motivations to seek and maintain long-term romantic relationships with members of this outgroup. The ambivalent sexism theory (Glick & Fiske, 1996) captures these conflicting views of women by specifying two forms of sexist attitudes. Hostile sexism refers to derogatory attitudes of women as inferior to men and general suspicions that women are seeking to control them (Glick & Fiske, 1996, 2012). By contrast, benevolent sexism depicts women “as pure creatures who ought to be protected, supported, and adored and whose love is necessary to make a man complete” (Glick & Fiske, 2012, p. 70), which prescribes traditional gender roles that, despite the positive tone, continue to promote inequality. Distinguishing between hostile and benevolent sexism is pivotal to understanding the mixed evidence that exists regarding the relation between sexist attitudes and IPV perpetration. Allen, Swan, and Raghavan (2009) reviewed existing studies examining the links between sexist attitudes, including hostile and benevolent sexism scales—Spence and Helmreich's (1972) Attitudes Toward Women Scale and Glick and Fiske's (1996) Ambivalent Sexism Inventory—, and IPV usually assessed via behavioral self-reports (e.g., Conflict Tactic Scale 2 - CTS, Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). Their review suggested that sexist attitudes toward women were not consistently related to IPV against women (see also Cross et al., 2017; Herrero, Torres, Rodríguez-Díaz, & Juarros-Basterretxea, 2017; Juarros-Basterretxea, Herrero, Fernández-Suárez, Pérez, & Rodríguez-Díaz., 2018; Renzetti, Lynch, & DeWall, 2015). Allen et al. (2009) pointed out that the relation between sexism and IPV is more consistent when examining hostile sexism, whereas the association between benevolent sexism and IPV is inconsistent perhaps because benevolent sexism promotes protection of women who adhere to gender roles, but more punishing attitudes toward women who violate gender roles (Glick, Sakalli-Ugurlu, Ferreira, & Aguiar de Souza, 2002). Thus, considerations of the links between sexist attitudes and aggression need to take into account the different types of ambivalent sexist attitudes. Given that the mixed results in the literature indicate that not all men who endorse sexist attitudes against women will perpetrate IPV, it is also important to identify the mechanisms that help explain the association between sexist attitudes and IPV perpetration. For example, prison inmates who report past IPV (batterers) do not differ in levels of sexist attitudes from those who do not report past IPV (non-batterers; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2018). A key mechanism why sexist attitudes may lead to greater IPV is the fact that hostile sexist attitudes should promote positive attitudes toward the use of violence toward women. Although the study of IPV has lacked research of attitudinal variables beyond sexist attitudes (and other related attitudes as, for example, victim-blaming; see Martín-Fernández, Gracia, & Lila, 2018), general attitudes toward the use of violence have been studied in depth with regard to more general violent behavior (DeWall & Anderson, 2011). As Anderson and Bushman (2002) pointed out, although positive attitudes toward violence in general are related with high rates of aggression in general, specific attitudes toward the use of violence against certain groups (i.e., women) more precisely predict aggressive behavior against members of that group (i.e., intimate partner). There are also empirical studies showing the relevance of attitudes toward violence mediating predictors of the use of violence. For example, Spaccarelli, Coatsworth, and Bowden (1995) found that attitudes toward violence mediated the association between exposure to family violence and serious violent offending. Stoddard, Varela, and Zimmerman (2015) also demonstrated that attitudes toward violence mediated the effect of thoughts, plans, motivations, and feelings about the future on bullying perpetration. In a similar fashion, attitudes toward violence toward women should be a key mediator between risk factors of IPV and IPV perpetration. Indeed, research has shown that more positive attitudes toward IPV in particular increase the likelihood of actual IPV perpetration (Eckhardt & Crane, 2014). Moreover, and perhaps not surprisingly, hostile sexism also predicts more positive attitudes toward IPV (Forbes, Adams-Curtis, & White, 2004; Glick, et al., 2002; Gracia, Rodríguez, & Lila, 2015; Herrero, Rodríguez, & Torres, 2016; Sakalli, 2001; Wang, 2016; Yoshikawa, Shakya, Poudel, & Jimba, 2014). However, two limitations characterize these prior studies linking sexist attitudes, positive attitudes toward abuse of partner, and IPV. First, a principal focus has been on physical IPV perpetration (wife beating) rather than more common forms of psychological IPV. Second, no research has examined how attitudes toward abuse of intimate partners play an explanatory role in the links between hostile sexism and IPV. In sum, prior research has found mixed results between sexist attitudes and IPV due to the need to clarify different forms of sexism and the need to identify proximal mediating factors. Research examining violence outside intimate relationships (IPV) has shown that specific attitudes toward violence in particular tend to mediate the associations between more general risk factors and violence perpetration. In the current study, we extend prior research to specify that hostile sexism, and not benevolent sexism, will be associated with psychological IPV via (i.e., mediated by) more positive attitudes toward violence. We also extend prior literature on IPV by considering whether these predicted associations between sexism, attitudes toward abuse of partner, and IPV are independent of broader risk factors that could determine or override attitudinal variables. An Ecological Approach to Investigating IPV Sexist attitudes and positive attitudes toward IPV are relevant risk factors of IPV perpetration, but the effect of sexist attitudes may be accounted for by broader factors that predict IPV. In particular, comprehensive ecological models often applied to understand physical IPV recognize and account for multiple risk factors that occur at different levels, including individual characteristics such as sexist attitudes, but also broader family-of-origin and social/community factors. Thus, an ecological approach extends understanding regarding the relevance of specific predictors in the context of a range of influential variables that contribute to violence risk (see Dahlberg & Krug, 2002). In particular, some researchers have pointed out that antecedents of IPV are probably also antecedents of the use of violence in general (Dutton, 1988; Felson, 2006; Felson & Lane, 2010; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2018; Moffit, Krueger, Caspi, & Fagan, 2000; Sjödin, Wallinius, Billstedt, Hofvander, & Nilsson, 2017). Thus, it is possible that the association between hostile sexism, attitudes toward violence toward women, and IPV are simply the result of broader factors that contribute to greater violence. Although prior adoptions of ecological models in investigating IPV exist, this application has typically focused on reviewing, not on empirically assessing, risk factors (e.g. Carlson, 1984; Cummings, González-Guarda, & Sandoval, 2013; Han, Kim, & Tyson, 2010; Heise, 1998; Little & Kaufman, 2002; Tonsing, 2011). However, there have been some recent adoptions of the ecological framework to empirically analyze risk factors (e.g., Akhter & Wilson, 2016; Herrero et al., 2017). In the current research, we apply an empirical, ecological approach to provide more accurate information about the relevance of hostile sexism and attitudes toward IPV in predicting psychological aggression. Thus, we offer a comprehensive analysis of sexist attitudes and the hypothesized mediational effect of positive attitudes toward the abuse of intimate partners by simultaneously modeling other variables established as IPV perpetration risk factors at community-, family-of-origin-, and personality levels. Community and IPV: Social Disorder Although the majority of research examining IPV has considered individual level factors, community factors are important to attend to in relation to general violence (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim., 2012; O´Brien & Sampson, 2015; Wilson & Kelling, 1982) as well as IPV perpetration (Whitaker, 2014). As Beyer, Wallis, and Hamberger (2015) have pointed out in their study reviews, different neighborhood environment aspects, such as lower levels of collective efficacy, lower levels of social cohesion, and stronger norms of nonintervention, influence IPV occurrence. One of those important community variables that extends beyond a typical focus on economic aspects (i.e., socioeconomic level, or community resources; Beyer et al., 2015) is the social community disorder, which prior research has shown relates specifically to positive attitudes toward violence (Gracia & Herrero, 2007) as well as increased IPV (Cunradi, 2007, 2009). The social community disorder involves being exposed to the presence of people drinking and/or taking drugs in public, fighting, selling drugs, prostitution, and other activities that promote insecurity or sense of danger (Wilson & Kelling, 1982). The perceived lack of informal social control in these contexts promotes the feeling of impunity of violent behaviors, such as IPV (Cunradi, 2007, 2009) and stressful neighborhood conditions may trigger IPV (Beyer et al., 2015; Gracia, López-Quilez, Marco, & Lila, 2015; Pinchesvky & Right, 2012). Accordingly, prior research has found positive associations between community social disorder and IPV perpetration (Cunradi, 2007, 2009), and community social disorder and levels of tolerance and acceptability of IPV (Gracia & Herrero, 2007). Family of Origin and IPV: Conflictive Climate Family-of-origin violence (FOV) is also a relevant risk factor of future IPV perpetration in adulthood (Capaldi et al., 2012). FOV involves exposure to violence within the family of origin before the age of 18 (Elmquist et al., 2015). The traditional conceptualization of FOV encompass witnessing interparental physical IPV and witnessing or being a direct victim of parent-to-child physical violence during childhood (Capaldi et al., 2012; Elmquist et al., 2015). However, other aspects of FOV, including hostile parenting and psychological aggression toward the child and parent-to-child maltreatment, are also important components (Capaldi & Gorman-Smith, cited by Lohman, Neppl, Senia, & Schofield, 2013; Capaldi et al., 2012; Herrero, Torres, & Rodríguez, 2018; Lohman et al., 2013). A FOV approach indicates that exposure to violent interactions between parents result in children and adolescents learning that violence is a good way to solve problems, both with other people in general and with romantic partners particularly (Lohman et al., 2013). Individual Characteristics and IPV: Antisocial Personality Traits Different personality traits and disorders also represent possible risk factors of IPV perpetration (Capaldi et al., 2012). In particular, antisocial personality traits and antisocial personality disorder (APD) have been broadly studied in relation with male-to-female IPV perpetration (Brem, Florimbio, Elmquist, Shorey, & Stuart, 2018; Capaldi et al., 2012; Fernández-Suárez, Pérez, Herrero, Juarros-Basterretxea, & Rodríguez-Díaz, 2018). Batterer typologies, for example, have identified specific types of batterers characterized by a large criminal curriculum, violence within and outside the family, including batterers that are: dominating and violent/bully (Faulk, 1974), controllers (Elbow, 1977), tyrants (Caesar, 1986), undercontrolled with regard to hostility (Hershorn & Rosenbaum, 1991), narcissistic/antisocial (Hamberger & Hastings, 1986), antisocial and sociopathic (Gondolf, 1988), generally violent (Herrero, Torres, Fernández-Suárez, & Rodríguez-Díaz, 2016; Saunders, 1992), and generally violent/antisocial (Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994). Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) indicated that this kind of batterer is likely to have an antisocial personality disorder, and that antisocial personality disorder will be higher among batterers who have been arrested. Furthermore, Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) outline that batterers with antisocial personality disorder are usually characterized by exposure to violence during childhood, rigid, and conservative attitudes toward women, and positive attitudes toward the use of the violence in general and against their partners. Thus, this antisocial personality factor could account for the effects of both FOV and attitudinal variables, such as hostile sexism. The Current Research The present study had two aims. The first aim was to investigate the effect of hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes on psychological aggression against intimate partners, and the hypothesized mediating role of positive attitudes toward IPV. The second aim was to follow an ecological approach to examine the relative influence of sexist attitudes and attitudes toward IPV when accounting for broader risk factors at the levels of community (social disorder), family-of-origin (conflictive climate in family of origin), and personality variables (antisocial personality traits). This approach overcomes the potential limitation of prior studies focused on one level of analysis (DeWall & Anderson, 2011) by taking into account different contexts of participants' life when examining the associations between sexism, positive attitudes toward IPV, and psychological IPV. To meet each aim, two fully saturated models were calculated to analyze the effect of sexist attitudes on psychological aggression perpetration in a penitentiary sample of 196 inmates of the Penitentiary Center of Villabona (Asturias, Spain). First, the effect of sexist attitudes on psychological aggression perpetration was analyzed distinguishing the total effect and indirect effect of sexism when the potential mediating role of positive attitudes toward partner abuse was modelled. We hypothesized that hostile sexism (and not benevolent sexism) would predict psychological aggression via positive attitudes toward IPV perpetration. Second, to test whether the connections between sexist attitudes and psychological IPV occur independently of other important community-, family-of-origin-, and personality factors, a second model calculated the direct and indirect effects of sexist attitudes on psychological aggression taking into account additional risk factors at these three levels, including community social disorder, family of origin violence, and antisocial personality disorder. Participants The sample consisted of 196 male inmates of the Penitentiary Center of Villabona (Asturias, Spain). Participants were 19 to 66 years old (M = 36.55, SD = 9.85). Inmates were sentenced for a variety of crimes: 43.3% (n = 85) for crimes related to IPV (gender violence according to Spanish legal system), 36.2% (n = 71) for violent crimes not related to IPV (i.e., homicide, aggressions), and 20.4% (n = 40) for non-violent crimes (i.e., white-collar crimes). Procedure The researchers approached the governmental and penitentiary authorities and explained the study objectives in order to obtain permission to evaluate inmates on a set of variables. After official access was granted, the researchers asked for voluntary participants from a list provided by the penitentiary center with the names and the wing where the inmate was quartered. After obtaining informed consent, participants completed a set of self-report questionnaires. In the present study, only questionnaires pertinent to the aims of the study are considered. Materials Outcome variable Psychological aggression against intimate partner. The psychological aggression subscale of the Revised Conflict Tactic Scales (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) was used to evaluate frequency of psychological aggression perpetration against intimate partners during participants' last year of the relationship with their last partner before imprisonment. The subscale consisted of 8 items (e.g., “Insulted or swore at my partner”). The items were rated on an eight-point Likert scale, from 0 (this never happened) to 6 (happened more than 20 times). There was a further option 7 (not in the past year, but it did happen before), with only 13 (6.6%) participants selecting this option for one of the items. The present study focused on the last year of the relationship to provide uniform assessment across participants, and to cohere with the way the CTS2 is typically used (aggression across the past year). Thus, response category 7 was coded as 0, and then the items averaged to construct overall scores of psychological aggression against intimate partners over the last year prior to imprisonment (α = .926). Predictor Sexist attitudes. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI; Glick & Fiske, 1996) was used to evaluate sexist attitudes toward women. The scale consists of 11 items assessing hostile sexism (e.g., “Women are too easily offended”) and 11 items assessing benevolent sexism (e.g., “Women should be cherished and protected by men”). All the items were rated on a five-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly), and further summed to construct separate scores for endorsement of hostile (α = .831) and benevolent sexism (α = .830). Mediator variable Positive attitudes toward abuse against intimate partner. The subscale of abuse of the Intimate Partner Violence Attitude Scale (IPVAS; Smith, Thompson, Tomaka, & Buchanan, 2005) was used. Nine items assessed positive attitudes toward abuse against intimate partners (e.g., “Threatening a partner is okay as long as I don't hurt him or her” or “It is not appropriate to insult my partner in front of others” [reverse-scored]). Responses ranged on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly) and were scored and summed to construct score for positive attitudes toward abuse against partners (α = .703). Control variables Antisocial personality traits. Antisocial personality traits were measured by Millon's Multiaxial Clinical Inventory III (Cardenal & Sánchez, 2007) APD subscale, which consists of 17 true-false items (e.g. “Punishment never stopped me from doing what I wanted”; 1 = false, 0 = true). Although cut-off scores exist to identify specific categories (75, syndrome; 85, disorder; Cardenal & Sánchez, 2007), we focused on varying levels across the total scores to cohere with all other measures, provide more sensitive tests across levels of antisocial personality, and produce more interpretable results in the context of the overall models. Thus, we summed the scores together so that higher scores represent greater antisocial personality (α = .760) Conflictive climate in family of origin. The conflict subscale of the Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1981, 1994) was used to measure the conflict level among members of the family of origin. The subscale consists of nine items, which originally refer to present family dynamics (e.g., “We fight a lot in our family”). In the present study, items were modified to assess conflictive climate in the family of origin (e.g., “We fought a lot in our family”). Item responses ranged on five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and summed to construct score for conflictive climate level in family of origin (α = .912). Community social disorder. Perceived community social disorder was assessed using three items that asked participants to rate the frequency of crime in their last community before going to prison (“There is a lot of crime in my community [fights with weapons, sexual aggressions, domestic violence, robberies, assaults, etc.”]), presence of drug-related problems (“There are a lot of drug traffic and consumption in my community”), and nightlife (“There is a lot of nightlife in my community”; see Gracia & Herrero, 2007; Herrero & Gracia, 2005 for a similar approach). Item responses ranged from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly) and were summed to obtain an overall score for community social disorder level (α = .756). Data Analysis Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the direct and indirect associations between sexist attitudes and psychological aggression. It is important to note that saturated models do not have degrees of freedom and thus tests to evaluate model or adjustment cannot be conducted. Instead, the interest of saturated models lies in the analysis of relations between all variables. Two fully saturated models were tested. In Model 1, hostile and benevolent sexism predicted partner aggression directly as well as indirectly via their influence on attitudes toward partner abuse. Model 2 added to Model 1 by incorporating the ecological control variables, including antisocial personality, family conflict, and community social disorder, to better assess the relative influence of sexist attitudes on psychological aggression when broader risk factors are considered together. Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Zero Order Correlations across All Variables   *p = .05, **p = .01. EQS 6.3 structural equation program (Bentler, 1995) was used to estimate models, IBM SPSS Statistics 22 package was used to calculate means and standard deviations, and FACTOR 10.3 was used to calculate reliability at item level (items were treated as ordinal variables) (Elosua & Zumbo, 2008). Models were tested at scale level so polychoric correlations were not needed (scale scores were treated as continuous variables). Table 1 provides descriptive statistics and Pearson zero-order correlations across all variables. As expected, hostile sexism was associated with more positive attitudes toward abuse of partner and greater psychological aggression (r = .277, p < .01). Hostile and benevolent sexism also presented a varied pattern of correlations with control variables. Hostile sexism was positively associated with benevolent sexism (r = .317, p < .01), antisocial personality traits (r = .201, p < .01), but not with conflictive family of origin (r = .083, ns) and community social disorder (r = .138, ns). However, conflictive family-of-origin (r = .165, p < .05) and community social disorder (r = .309, p < .01) were significantly associated with psychological aggression. The results of Model 1 are displayed in Figure 1. The total, direct and indirect effects of hostile sexist attitudes on psychological aggression were significant. Greater hostile sexism was associated with positive attitudes toward abuse of partner (β = .275, p ≤ .001), which in turn predicted greater psychological aggression (β = .254, p ≤ .001). The total effect of hostile sexism on psychological aggression (β = .246, p ≤.01) includes both the indirect effect via positive attitudes toward abuse of partner (β = .070, p ≤ .01) and the direct effect on psychological aggression (β = .177, p ≤ .05). Moreover, 28.45% (.070/.246 = 0.2845) of the total effect of hostile sexist attitudes on psychological aggression was explained by the tendency of individuals who endorse hostile sexism to possess more positive attitudes toward abuse of intimate partners. These effects take into account the fact that hostile and benevolent sexism are positively correlated (r = .317, p ≤ .001). Benevolent sexist attitudes did not show a direct statistical relationship with positive attitudes toward abuse of intimate partners (β = .017, ns) after controlling for hostile sexism. Figure 1 Model 1: The Effect of Sexist Attitudes on Psychological Aggression and the Mediational Role of Positive Attitudes toward Abuse of Partner. Total effectsare included in parentheses.   *p = .05, **p = .01, ***p = .001. Second, to better account for alternative explanations of the associations between sexism and IPV, we added to Model 1 the effects of antisocial personality traits (individual), conflictive climate in family of origin (family), and community social disorder (community) on psychological aggression (see Figure 2 [Model 2] below). The indirect effect of hostile sexism via positive attitudes toward abuse of partner remained significant (β = .064, p ≤ .01), but the direct effect was no longer significant (β = .143, ns). Thus, the unique association of hostile sexism with psychological aggression when controlling for broader risk factors occurred via positive attitudes toward abuse. By contrast, community social disorder showed a direct association with psychological aggression (β = .297, p ≤ .001) suggesting wider environmental factors may directly shape aggressive responses. Conflictive climate in family of origin, on the other hand, showed an indirect association (β = .056, p ≤ 05) with psychological aggression, indicating that family dynamics might also influence aggressive behavior by helping to shape more positive attitudes toward abuse of intimate partner. Figure 2 The Effect of Control Variables and Sexist Attitudes on Psychological Aggression and the Mediational Role of Positive Attitudes toward Abuse of Partner.   Note. Total effects are shown in parentheses. *p = .05, **p = .01, ***p = .001. Using data from 196 imprisoned men from the Penitentiary Center of Villabona (Asturias, Spain), this study examined the associations between sexist attitudes and psychological aggression against intimate partners. The aims of the study were twofold: first, we analyzed the effect of hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes on psychological IPV, along with the hypothesized mediational role of positive attitudes toward abuse of intimate partner. Second, we then examined these associations within a broader ecological framework by taking into account the effect of variables at community (social disorder)-, family-of-origin (conflictive climate in family of origin)-, and personality (antisocial personality traits) levels. First, the results supported the hypothesis regarding the mediational effect of attitudes toward abuse against intimate partner explaining the association between hostile sexist attitudes and psychological IPV. Thus, participants' hostile sexism scores were positively related to attitudes toward abuse of intimate partners which, in turn, predicted higher IPV against women. Benevolent sexism did not show a direct or an indirect relationship with IPV against intimate partners. Second, although a significant direct effect of hostile sexism on psychological IPV against partner also emerged in the first analyses, this direct effect was removed once other variables of the ecological context were taken into account (but the indirect effect of hostile sexism on psychological IPV via attitudes toward abuse of intimate partners remained significant). These results suggest that studies on how hostile sexism shapes important processes, such as psychological IPV, should incorporate a wider lens of the varying individual, family, and community variables that also contribute to that behavior. In particular, an ecological approach strengthens understanding of how hostile sexism is likely to relate to important behaviors that have multiple causes. For example, the current analyses indicate that wider social factors, such as more socially disordered community environments, may promote psychological IPV. Two possible mechanisms have been proposed to explain this relationship. First, community social disorder can promote violent behaviors through the perception of lack of informal social control, thus promoting the feeling of impunity of behaviors such as IPV (Cunradi, 2007, 2009). Second, unfavorable community conditions such as social disorder might relate to higher levels of stress, which can trigger IPV (Beyer et al., 2015; Gracia et al., 2015; Pinchesvky & Right, 2012). Conflict within the family of origin was also associated with psychological IPV, specifically via more positive attitudes toward intimate partners abuse. This finding is in accordance with social-learning research that suggests that greater exposure to conflictive climate in family contexts might result in learning violence against intimate partners as an acceptable way to solve problems, thereby promoting psychological IPV perpetration (Lohman et al., 2013). These distinctions again support that personal experiences (family dynamics) and attitudes (hostile sexism) create more specific attitudes about relationship processes (attitudes toward intimate partners abuse) that promote psychological IPV. This is consistent with other studies showing that positive attitudes toward abuse are associated with reports of prior IPV as well as future IPV perpetration (Capaldi et al., 2012; Elmquist et al., 2015; Lohman et al., 2013), and our results identified these attitudes as a potential explanatory mechanism for the association between sexist attitudes and psychological IPV against women. This pattern not only enhances understanding of the ways in which hostile sexism (and conflictive climate in family of origin) shapes psychological IPV, but it also has important implications for treatment. Despite the results obtained in other research (see Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994 for a review), where the batterers with APD or antisocial personality traits use more psychological aggression against their partner than those who present low levels of antisocial traits, our results suggest that the effect of antisocial personality traits were limited when other attitudinal, community, and family-of-origin factors were considered. Prior research has shown that family-of-origin and community variables might relate to the development of antisocial traits or APD (Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994). However, the inclusion of antisocial personality traits, community social disorder, and conflictive climate in family of origin in the same research design, as in our case, helped rule out potentially spurious relationships between antisocial personality and IPV that may be accounted for these other variables. Replicating these effects and establishing if antisocial personality traits are associated with IPV independent of the community-, family-, and attitudinal factors, is an important direction for future research. Strengths and Limitations The current study had both strengths and limitations. The strengths include the participants of the study as well as the ecological framework guiding the research design. By using a prison sample, this study extended the existing empirical evidence from the most commonly assessed community and convenience samples to an important population at risk for both IPV and poor functioning. In addition, the relationships observed between sexism and psychological IPV control statistically for the potential influence of these personal, family and community variables, which again adds robustness to the model (Tonsing, 2011). These two potential strengths add generalizability to the results of the study. Nonetheless, the study also had some potential limitations. First, the measurement of the variables of the family and community settings is dependent on the perceptions and recall of the participants, who may have incorporated biased responses. Thus, the indirect associations between hostile sexism, attitudes toward abuse, and psychological IPV emerged controlling for what participants recalled and believed their history to be rather than objective conditions of their past family, and community contexts. Undoubtedly, the incorporation of other measurement strategies, such as additional key informants or multi-informants of participants (see De Los Reyes, Thomas, Goodman, & Kundey, 2013), would provide stronger evidence for the conclusions offered here. Second, all of the information was obtained through self-reports, which can provide biased data about the dynamics couples, especially in the case of psychological IPV. Collecting information from the other dyad member would allow identification of mutual aggressions (Low, Tiberio, Shortt, Capaldi, & Eddy, 2016) and to explore the role that hostile sexism plays in this process. Examining psychological aggression by the participant's partner, and the impact this aggression has, also will clarify whether the psychological aggression assessed in the current study represents violence victimization as experienced by intimate partners (Cross & Overall, 2018) and allows us to identify the existence of either psychological damage or malingering (Arce, Fariña, & Vilariño, 2015; Vilariño, Amado, Vázquez, & Arce, 2018). Third, and related, the correlational nature of the study cannot establish antecedents versus consequences across the variables assessed. For example, the study does not identify the extent to which positive attitudes toward the use of partner violence reflect an attempt by the subject to make their attitudes consonant with their behaviors. From this point of view, positive attitudes would reflect an attempt by those individuals who act aggressively to cognitively justify their actions. The incorporation of the temporal dimension in future research could help unravel this process. This unique study of 196 incarcerated men of the Penitentiary Center of Villabona (Asturias, Spain) advances in the understanding of the associations between sexist attitudes and psychological aggression against intimate partners. Hostile sexist attitudes were associated with higher IPV via its effect on positive attitudes towards intimate partners abuse. In addition, the links between hostile sexism, more positive attitudes of abuse of intimate partners, and the perpetration of IPV continued after controlling for broader variables such as family of origin and community social disorder. This suggests, on the one hand, that only the most derogatory attitudes towards women (hostile sexism) relate to psychological IPV. But this relationship is, on the other hand, of an indirect nature: sexist attitudes must first be translated into a positive attitude toward abuse to influence psychological IPV. While this pattern suggests that sexist attitudes might help understand IPV, it also indicates the need to analyze other antecedents of violence in different ecological systems (from the individual to the macrosocial systems). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Overall, N., Herrero, J., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J. (2019). Considering the effect of sexism on psychological intimate partner violence: A study with imprisoned men. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11, 61-69. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a1 Funding. Support for this research was provided by FEDER founds from Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO-17-PSI2016-77484-P), and Severo Ochoa scholarship (BP14153) from Foundation for the Promotion in Asturias of Applied Scientific Research and Technology (FICYT, Asturias, Spain). References |

Cite this article as: Juarros-Basterretxea, J., Overall, N., Herrero, J., & Rodríguez-Díaz, F. J. (2019). Considering the Effect of Sexism on Psychological Intimate Partner Violence: A Study with Imprisoned Men. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11(2), 61 - 69. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a1

juarrosjoel@uniovi.es Correspondence: juarrosjoel@uniovi.es (J. Juarros-Basterretxea).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS