Early Narratives of Desistance from Crime in Different Prison Regimes

[NarraciĂłn temprana del desistimiento delictivo en diferentes regĂmenes penitenciarios]

Ana M. Martín1, Federica Padrón1, and Santiago Redondo2

1Universidad de La Laguna, Spain; 2Universitat de Barcelona, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a2

Received 11 February 2019, Accepted 15 April 2019

Abstract

Priority given to investigating the onset and maintenance of criminal behavior in the past is currently giving way to a new focus on the process of criminal desistance. Early narratives of future desistance are the first step in this process and, although they do not assure withdrawal from crime, they are the beginning of the personal change that precedes a progressive desistance from criminal activity. This study analyzes early desistance narratives of offenders still in prison and whether these narratives differed depending on their personal, criminal, and social characteristics. Participants were 44 imprisoned male offenders, aged between 20 and 50 years old at different stages of their sentence and in three different prison regimes. They were interviewed using Cid and Martí’s protocol and their accounts were accordingly coded in three categories: early narratives towards a non-criminal identity, perceived self-efficacy to desist from crime, and will to desist. The results show that participants’ early desistance narratives vary depending on their personal, criminal, and social variables. Results on the periods of sentence completion and prison regimes are discussed in terms of how prisons could contribute to enhancing the narratives of desistance from crime.

Resumen

La prioridad otorgada en el pasado a la investigación sobre el inicio y mantenimiento de la conducta delictiva está dando paso actualmente al análisis del proceso de desistimiento delictivo. Las narrativas tempranas del desistimiento futuro son el primer paso en este proceso y, aunque no aseguran dicho desistimiento, son el comienzo del cambio personal que precede al abandono progresivo de la actividad delictiva. Este estudio analiza las narrativas tempranas de desistimiento de delincuentes aún en prisión y si estas narrativas difieren según sus características personales, delictivas y sociales. Los participantes fueron 44 varones encarcelados, con edades comprendidas entre los 20 y los 50 años, en diferentes fases de su sentencia y en tres grados penitenciarios distintos. Fueron entrevistados utilizando el protocolo de Cid y Martí y sus relatos fueron codificados en tres categorías: narrativas tempranas sobre una identidad no delictiva, autoeficacia percibida para desistir del delito y voluntad para desistir. Los resultados muestran que las narrativas tempranas de desistimiento de los participantes difieren según sus características personales, delictivas y sociales. Los resultados relativos a la fase de la sentencia y a los grados penitenciarios se discuten en términos de cómo las prisiones pueden contribuir a potenciar las narrativas de desistimiento delictivo.

Keywords

Criminal desistance, Early desistance narratives, Prison regimes, Identity change, Self-efficacyPalabras clave

Desistimiento delictivo, Narrativas tempranas de desestimiento, Grados penitenciarios, Cambio de identidad AutoeficaciaCambio de identidad, AutoeficaciaCite this article as: Martín, A. M., Padrón, F., & Redondo, S. (2019). Early Narratives of Desistance from Crime in Different Prison Regimes. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11(2), 71 - 79. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a2

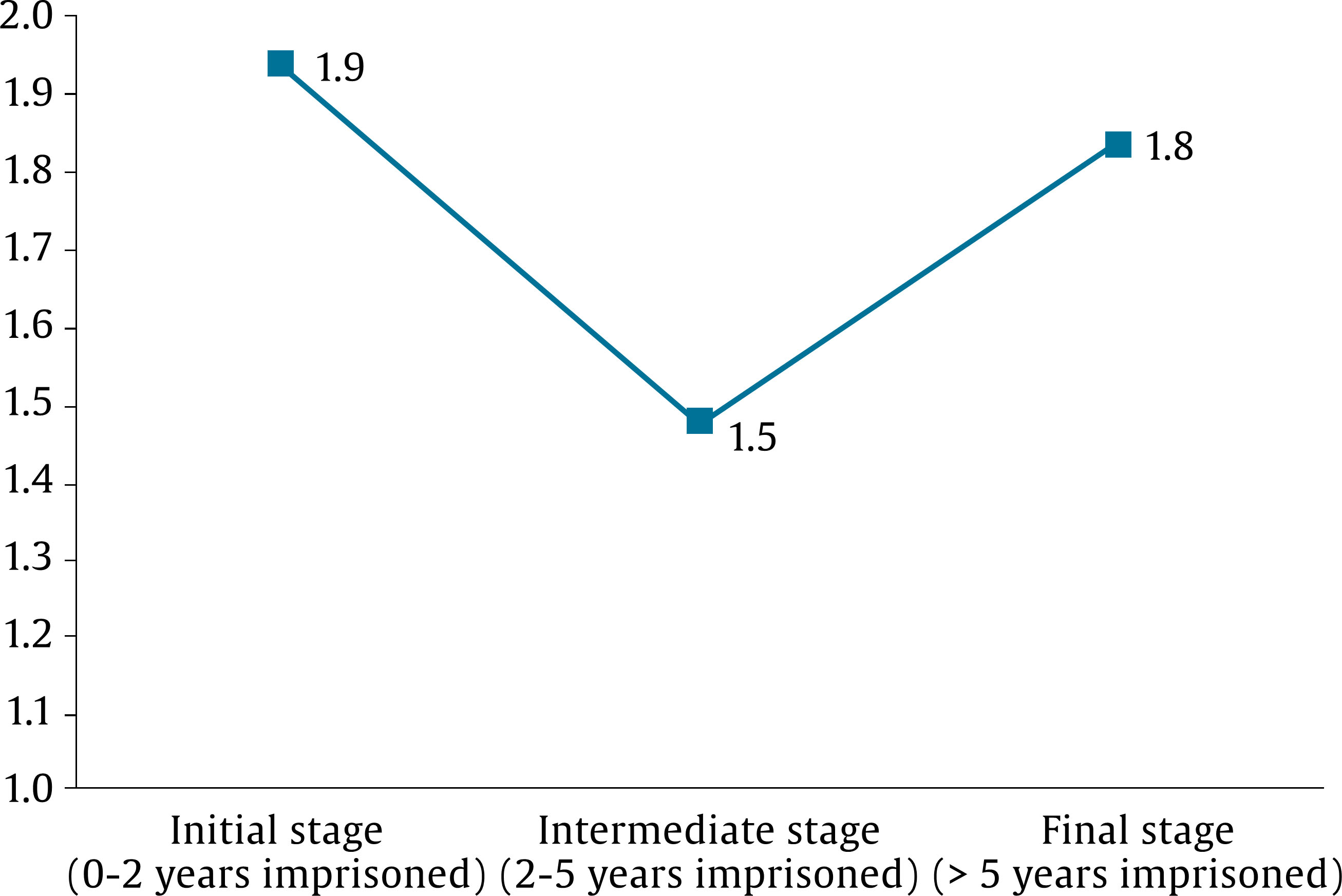

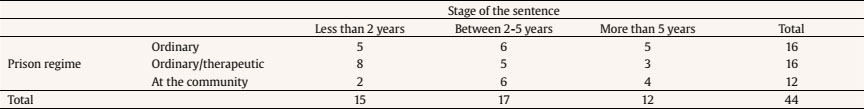

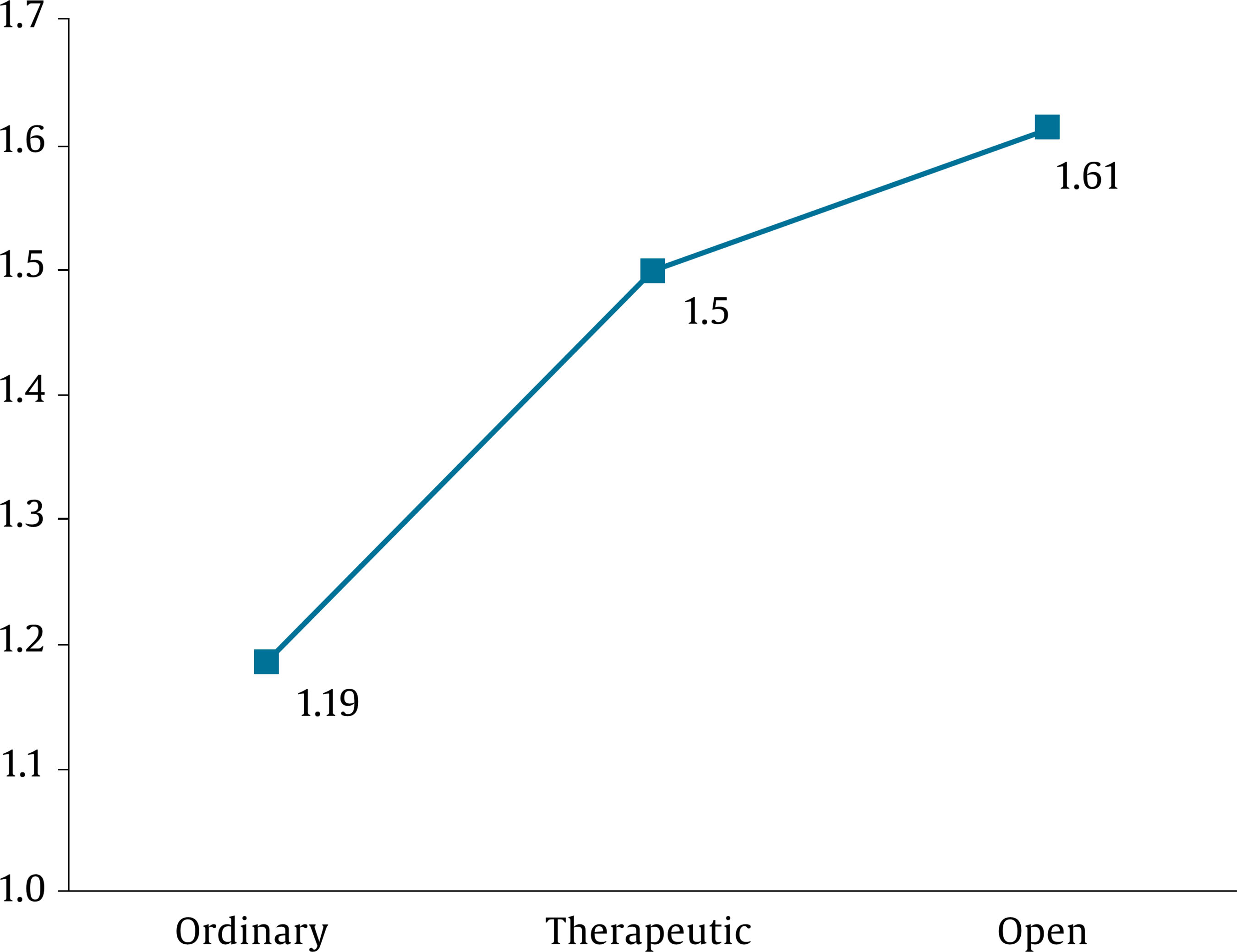

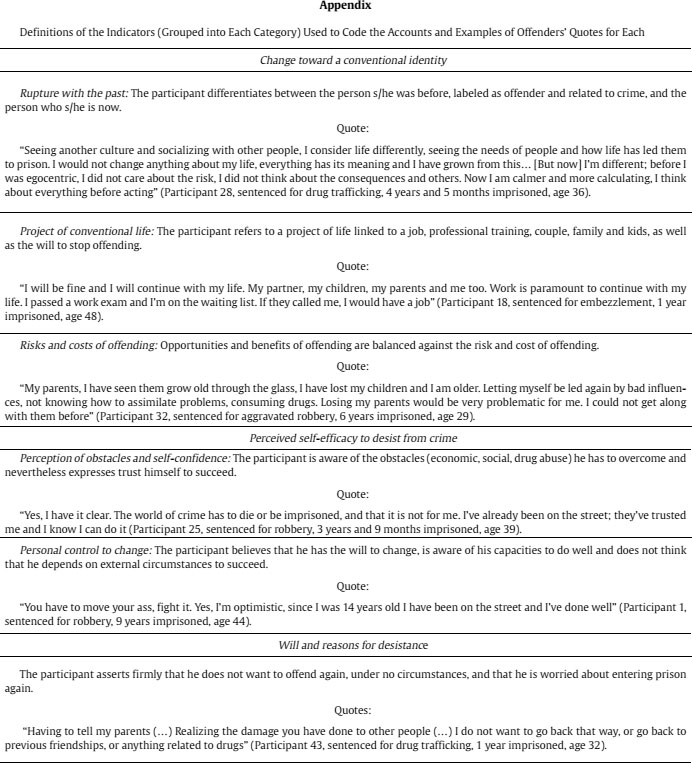

ammartin@ull.edu.es Correspondence: ammartin@ull.edu.es (A. M. Martín).The most frequent indicator of whether or not criminals continue offending has been recidivism rates, which are, on average, around 50% (Zara & Farrington, 2016). This rate means that the remaining 50% of offenders do not re-offend. This percentage can be interpreted as the static figure of crime cessation. However, desistance from crime, albeit quantitatively inverse to the global recidivism rate (Polascheck, 2016; Walker, Bowen, & Brown, 2013), is a more complex and dynamic process than just the final result of whether a person recidivates or not. For this reason, research into desistance requires paying attention to personal and social factors throughout the lives and criminal histories of those offenders who recidivate or desist from crime (Cid & Martí, 2012; Liem & Richardson, 2014). The study of the desistance process and its related factors has gained increasing interest during recent years and given rise to a specific field of criminal analysis (Abeling-Judge, 2017). It is closely linked to both the assessment of criminal careers (Farrington, 2007) and the evaluation of offenders’ desistance narratives (Maruna, 2015). The concept of “desistance narratives” refers to those stories in which people express their rupture (Cid & Martí, 2012; Halsey, 2017; Maruna, 2001; Presser & Sandberg, 2015) or expectations of rupture (Doekhie, Dirkzwager, & Nieuwbeerta, 2017) with their previous criminal identities and, at the same time, perceive themselves capable of beginning a conventional non-criminal life. It has been suggested that such narratives of criminal desistance or prosocial “transformation” include three main elements (Liem & Richardson, 2014; Maruna, 2001): the awareness of individuals of having a normal core self, which implies that criminal behavior does not define them globally; a generative motivation or perception that their own life has (non criminal) meaning; and a sense of agency, or ability to voluntarily take their own decisions and control their lives, including the possibility of stopping criminal behavior. Obviously, the expression by offenders of desistance narratives, generally in terms of intentions of non-criminal future behavior, does not guarantee their factual withdrawal from crime (Doekhie et al., 2017). However, identity change narratives in the direction of a prosocial life are considered a necessary step to give up committing crimes (Cid & Martí, 2012). It has been stated that this onward process towards criminal desistance is related to different personal and social factors: aging and maturation, race, gender, military service, marriage, and stable and meaningful interpersonal relationships (intimate partners, children, friends, etc.), motivation and commitment to change, prosocial values, moderate lack of stress, good mental health, structured activities, reevaluation of previous criminal conduct, stable employment, religion, identity change, perception of self-efficacy, expectation about the future, favorable characteristics of the reintegration context, and received social support (Abeling-Judge, 2017; Barr & Simons, 2015; Cauffman, Fine, Thomas, & Monahan, 2017; de Vries Robbé, Mann, Maruna, & Thornton, 2015; Doherty & Bersani, 2016; Forrest, 2014; King, 2013; Rocque & Wels, 2015; Shepherd, Luebbers, & Ogloff, 2016; Skardhamar & Savolainen, 2014; Stouthamer-Loeber, Loeber, Stallings, Lacourse, 2008; Terry & Abrams, 2017; Veysey, Martinez, & Christian, 2013; Walker et al., 2013; Weaver & McNeill, 2015; Zoutewelle-Terovan, van der Geest, Liefbroer, & Bijleveld, 2014). Various explanations of criminal desistance have been suggested which prioritize one or the other of the above protective factors (Walker et al., 2013). Some suggest that desistance would essentially result from increasing age, which is associated with neurobiological changes (brain development, hormonal variations, etc.) and a greater capacity for self-control. Others theories, such as structural and control criminological theories, suggest that desistance would result from an increase in the social bonds and controls that individuals experience in their transition to adult life (couple relationships, work ties, etc.), which reduce their criminal opportunities (Abeling-Judge, 2017; Paternoster, Bachman, Kerrison, O’Connell, & Smith, 2016; Walker et al., 2013; Youan & McNeil, 2017). Finally, a third group of desistance explanations highlight the fact that individuals experience a cognitive or identity transformation (Giordano, Cernkovich, & Rudolph, 2002; Maruna, 2001; Walker et al., 2013). This change in identity may be the result of learning new roles and definitions of behavior (Giordano et al., 2002; Paternoster et al., 2016), the acquisition of a new prosocial self-concept (Farrall & Maruna, 2004; Maruna, 2001, 2004; Maruna & Roy, 2007), or an increased perception of the benefits derived from leading a prosocial life (Doekhie et al., 2017; Paternoster & Bushway, 2009; Paternoster et al., 2016). From an empirical perspective, concerning personal factors, the most relevant finding is age-crime curve, which points to the fact that, in general, criminal behavior decreases with age (Walker et al., 2013). The process of criminal desistance is usually accompanied by a cognitive reconstruction of one’s own identity as a person (Bachman, Kerrison, Paternoster, O’Connell, & Smith, 2016; Maruna, 2001). However, for successful crime desistance it is imperative that the person relies on his own self-efficacy to make the necessary identity and behavioral changes (Maruna, 2004). Several studies have highlighted that offenders giving up crime tend to hold more optimistic beliefs about their capacities to control and improve their future life (Cid & Martí, 2011; Terry & Abrams, 2017) as well as greater feelings of achievement and personal fulfillment (Lebel, Immarigeon, & Maruna, 2004). Similarly, for the case of offenders that have been in prison for a long time, an increased perception of self-efficacy is a significant difference between those who desist from crime and those who do not (Liem & Richardson, 2014). Favorable personal changes, the evolution towards a non-criminal identity, and greater self-efficacy are related to improvements in the ability to control one’s own behavior. For an improvement in self-efficacy and for a non-criminal identity to appear, it seems to be critical to receive positive recognition from others of offenders’ change efforts, by means of what Nugent and Schikel (2016) have called “relational desistance” (de Vries Robbé et al, 2016; Maruna, 2001, 2004; Maruna & Lebel, 2010). Therefore, for their effective social reintegration, ex-prisoners must improve their social capital in terms of family, friends or work, etc. to be able to cover diverse vital needs ranging from food to housing (Brunton-Smith & McCarthy, 2017; Doekhie et al., 2017; Fox, 2015). In this respect, some authors have described the need for a turning point, a new significant life, or interpersonal event capable of activating the desistance process (Boman & Mowen, 2018; Laub & Sampson, 2003, 2005; Laub, Sampson, & Wimer, 2006; Petras & Liu, 2017; Skardhamar & Savolainen, 2014; Soyer, 2014). Cid and Martí (2012) prefer the term re-turning points because it might not necessarily be a new event which influences the individual in favor of crime desistance, but elements already present in his/her life (family, couple, job, etc.) that may acquire a distinct meaning at a different life stage. For this reason, it has been considered critical to foster both turning and re-turning points, not only during transition from prison to community but during prison stays (Alós, Martín, Miguélez, & Gibert, 2009; Bushway & Apel, 2012; de Vries Robbé et al., 2015). One of the most important sources of turning points that differentiates those who desist from or persist in crime seems to be transitional factors. Transitional factors, in terms of Cid and Martí (2011), are positive experiences that can favor the transition of offenders from prison to community, such as the external social support received for crime withdrawal (e.g., housing, job offer, social services, etc.) as well as family and social bonds (intimate partners, co-workers, new relationships and friendships) capable of reinforcing a new prosocial identity. These social factors, when positive, contribute to improving prisoners’ perceived self-efficacy and motivation to change (Cid & Martí, 2011, 2012). Some studies have analyzed the narratives of identity change of specific age groups of prisoners (Abrams, 2012), offenders serving short or long sentences (Liem & Richardson, 2014), or prisoners in certain prison regimes like therapeutic communities (Stevens, 2012). According to literature on “prison’s” negative effects, it can be expected that longer imprisonment produces increased prisonization and a greater likelihood of future recidivism (Moore & Tangney, 2017; Schaefer, 2016). On the contrary, a shorter and milder incarceration (including frequent contact of inmates with the community) increases their expectations for positive change and social reintegration (Laub & Sampson, 2003, 2005; Schaefer, 2016; Soyer, 2014). Cancellation of previous criminal records has also been shown to have a beneficial effect (Adams, Chen, & Chapman, 2017). It has been highlighted that the expression of a positive outlook in early stages of imprisonment would favor inmates’ future desistance from crime (Apel, 2013; Giordano et al., 2002; Laub & Sampson, 2001; Maruna, 2001; Paternoster & Bushway, 2009). Shapland and Bottoms (2011) have also suggested that for offenders to improve their self-perception they must begin by showing in early stages of imprisonment an initial desire to change. In this context, King (2013) has proposed the concept of “early desistance narratives”, in reference to the first stage of personal change, when individuals begin to make interpretations of their own lives that contemplate the interruption of their criminal activity and of being someone different in the future. This idea is not far from the one formulated decades ago in the context of psychological therapy by Prochaska and DiClemente (2005) from their well-known “trans-theoretical model”. According to these authors, when people change (under the influence of a treatment or other vital circumstances), they usually do so not abruptly but little by little, transiting through different stages of change. An essential condition – or turning point, in the nomenclature of withdrawal analysis – is that individuals evolve from a non-contemplation stage, in which they are not yet aware of their problem, to one of contemplation, or recognition of having a problem that they should solve. In this framework of gradual change that would be expressed by the inmates in their “early desistance narratives”, Maruna (2001) retrospectively analyzed the narratives about their future of twelve former prisoners and of nine prisoners on license. He found a positive relationship between expressing an optimistic view of one’s future life and the factual absence of crime. Similar results were obtained in subsequent studies, where inmates who expressed more optimistic perspectives about their future also ended up showing a more prosocial life proved by facts such as finding work (Howerton, Burnett, Byng, & Campbel, 2009), searching and acquiring bonds and prosocial support from their partners and parents (Shapland & Bottons, 2011), and less criminal behavior (Souza, Lösel, Markson, & Lanskey, 2013). More recently, Doekhie et al. (2017) interviewed inmates about their social capital and other agency factors, as well as about their possible criminal activities, at the end of their prison sentences and three months after having completed them. Using thematic analysis, they found a strong relationship between prior criminal/non-criminal narratives (during incarceration) and later offending/non-offending behavior. As has been documented, the emergence of criminal withdrawal narratives is related to various personal, social, and criminal factors (aging and maturation, interpersonal relationships, employment, social support, fewer criminal opportunities, etc.). Since “early desistance narratives” are essentially desistance narratives expressed early, it is reasonable to think that there is also a relationship between them and those referred to factors. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no specific research in this regard, maybe because the concept of “early desistance narratives” is relatively recent. Hence, the present study pays attention to the investigation of such relationships. Summing up, early desistance narratives seem to be the first step in a progressive process of desistance (Laub & Sampson, 2001; Maruna, 2001) and, although they do not guarantee withdrawal from crime (Cid & Martí, 2012), they do show the beginning of the personal change needed for the interruption of criminal activity (King, 2013). Hence, a better knowledge of the relationship between early expectations of stopping crime and subsequent attempts to give up could contribute to improving the transition processes of offenders to social lives and ultimate desistance (Doekhie et al., 2017; King, 2013). However, it is still quite unknown, as has been highlighted, to what extent these early desistance narratives are related to personal, social, and criminal/prison variables. In particular, although these narratives may start during prison stay, it is largely unknown how they vary between offenders who are at different stages of serving their prison sentences and in distinct prison regimes, including intermediate prison units that allow inmates to go into the community for weekend leaves or therapeutic visits (Liem & Richardson, 2014). Nevertheless, the correctional system could support desistance to the extent that “encourage and support visitation and opportunities for success outside prison walls” (Maruna & Toch, 2005, p. 171). In connection with what has been argued above, this study is mainly concerned with analyzing whether the early desistance narratives of offenders who are still in prison vary depending on their personal, social-relational, criminal, and particularly correctional circumstances. Following Cid and Martí (2011, 2012), early narratives of desistance were assessed using three categories: changes towards a non-criminal identity, perceived self-efficacy to desist from crime, and will for desistance. Personal variables under study are offenders’ age and educational and socioeconomic levels. Criminal and prison variables involve offenses committed, previous and current sentences, age at first offense and at first prison entry, time spent in prison, and prison regimes and stages of offenders’ prison sentences being served. Finally, social-relational variables are individuals’ reasons for desistance, the received emotional support, and their social bonds. These three last variables are included in the current study, also in accordance with Cid and Martí (2011, 2012): the reasons for desistance are part of desistance narratives, as well as social support and social bonds, which are transitional factors that enhance and reinforce the creation of this narrative. Participants Participants were selected at convenience according to their stage of sentence completion and their prison regime, as displayed in Table 1. The final sample was composed of 44 offenders serving their prison sentences in one of the following stages: 34.1% were in initial stage of sentence completion (they had been imprisoned for less than two years), 38.6% in an intermediate stage (imprisoned between 2-5 years), and 27.3% in the final stage (imprisoned for more than 5 years). In accordance with prison regimes described in the next section, 36.4% of the sample was in a second grade or ordinary prison unit, 36.4% were also in second grade but in a special therapeutic-educative unit, and 27.3% of participants were in third grade or community regime. No participant in this study was in first grade or closed regime. In relation to the crimes committed by the sample, in 54.5% of cases participants were sentenced to prison for property crimes (half of them involving violence), 29.6% for drug dealing offences, and the remaining 15.9% for other crimes such as kidnapping, aggravated assault on police officers, resisting arrest, assault and battery, attempted homicide, homicide, and murder. Their sentences ranged from 1.5 to 18.75 prison years (M = 7.67, DT = 5.07) and specifically in the following lengths: 43.2% of the cases were sentenced between less than one year and five years, 25% from more than five years to ten years, and 31.8% from more than ten years to twenty years. In terms of sociodemographic characteristics, participants were between 20 and 50 years old (M = 33.11, DT = 7.92) and most of them were Spaniards (88.6%), plus one person corresponding to each of the following countries: Russia, Senegal, Nigeria, Colombia, and Venezuela. Concerning education, 43.2% of the sample had achieved secondary school level, 31.8% primary level, 18.2% high school level, and 6.8% had not graduated at any level yet. There was 56.8% of the sample that reported having a low economic level and the rest a medium economic level. Procedure and Design This study was carried out in Spain, where the law establishes three regimes for serving prison sentences, mainly depending on two conditions of the offenders: prisoners’ ability for sharing everyday living with others and the proportion of their sentence they already have served. First grade regime is a closed prison regime for inmates requiring high control and security safeguards (this excludes the granting of prison leave). Second grade or ordinary regime is the closed stage for those prisoners who are not ready for open or community regime yet, but could go out with periodic leaves. In the third or open regime, there are usually those offenders who have already served two-thirds of their prison sentence and are eventually eligible for parole. Inmates in open regime can stay the whole day outside prison and come back just for the night (Ley Orgánica 1/1979, de 26 de septiembre, General Penitenciaria, Art. 72.1; see also http://www.institucionpenitenciaria.es/web/portal/idioma/en/laVidaEnPrision/regimenes/). To contact participants, a research proposal describing the study objectives and methodology was prepared and attached to the application for conducting research in the prison. When administrative permission was granted, the objectives of the inquiry were presented to the prison staff, asking for their collaboration in the data collection process. Prison teachers, educators, social workers and psychologists collaborated in selecting and contacting participants. Participant selection followed the criteria of stage of sentence completion and prison regime as described above. Prison rules about using the least intrusive procedure as possible to access participants were carefully followed. Participation in the study was voluntary and personal anonymity of inmates was guaranteed. All inmates who were invited agreed to participate in the study. Participants’ statements were transcribed directly by the interviewer during the interview, because recording inmates inside prison either by video or by audio is prohibited by law in the study setting. Afterwards, transcriptions were analyzed using content analysis and the coding system described in the next section. The design involved comparisons of the criterion variables – change toward a conventional identity, self-efficacy for desistance and will to desist – among groups of participants. These groups were defined in terms of personal and criminal/prison variables. Personal variables included were age, and educational and socioeconomic levels. Criminal variables were records as juveniles, age at first sentence as juvenile, type of offense, age at first prison sentence as adult, length of actual sentence, current prison regime, and stage of sentence completion. Last of all, differences in the criterion variables – change toward a conventional identity, self-efficacy for desistance, and will to desist – were compared in relation to social-relational variables as the reasons for desistance, emotional support and social bonds. Measures Data were collected using the semi-structured narrative interview of Cid and Martí (2011, 2012). This interview is aimed at assessing not only participants’ experience of being in prison, but also the link and transitions between informed events and experiences, as well as details related to time, space, motivations, and strategies used for early crime desistance. This interview contains four sections: participants’ biography, criminal career, last prison entry, and transition narrative. As the present study focuses on participants’ narratives of identity change, perceived self-efficacy, and will to desist from crime, only the specific questions on these topics included in last section of Cid and Martí’s (2011, 2012) interview were used. Specifically, prisoners were asked questions about their future expectations, projects of conventional life, perceived external conditioning factors, optimism about future, will, self-efficacy, reasons and difficulties for desistance, risks and cost of offending, and identity and identity change. Questions were open-ended, such as “Looking back, are there things in the past that you would like to change or that you would have done in another way?”, “Do you feel able to stop offending?”, or “What/who has enabled you to start the process of stopping offending?” Participants’ answers were coded by means of directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Neuendorf, 2017) using narrative categories defined in terms of Cid and Martí’s (2011, 2012). These answers refer to those prisoners’ narratives that support their criminal desistance process, according to three categories: change toward a conventional identity, self-efficacy for desistance, and will for desistance. Several indicators were used for measuring each of these three narrative categories, by rating them 0 (No), 1 (Something) or 2 (Yes). Three final category scores were calculated by averaging scores in these indicators. The Appendix displays definitions of the indicators included in the three categories to code and rate participants’ narratives, as well as examples of quotes for each indicator. Participants were also asked social-relational questions about their reasons for desistance, who were their main sources of emotional support, and who exerted informal control over them by social bonds. Participants’ answers to these three questions were grouped in semantical terms. Participants’ reasons involved family, health, giving up drug abuse, and avoiding consequences of offending and of being in prison. Sources of emotional support included family, partner, children, and friends. Social bonds involved jobs besides the sources of emotional support already cited. Coding Reliability Two coders with extensive experience in using this type of coding procedure (González-Méndez, Martín, & Hernández-Abrante, 2014; Padrón, Martín, & Redondo, 2014, 2016) were trained with a coding manual that included detailed instructions about the definitions and indicators of the categories of analysis, as well as examples of quotes (see Appendix). All the interviews were coded and rated by one of the coders, and subsequently 50% of these interviews were selected at random for an independent double coding by the second coder. Coding was completed with the verification of exact correspondence of the categorization and rating of the quotes, resulting in true inter-coder concordance, as described by Monteiro, Vázquez, Seijo, and Arce (2018). This verification is necessary because otherwise two mistakes may be coded as a hit. Thus, the consistency of the coding process was assessed by inter-coder agreement, calculated by Cohen’s kappa. The result of the verification of coding accuracy or true kappa was .91, which reflects an “almost perfect” (≥ .81) level of inter-coder agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977; Monteiro et al., 2018). As the true concordance between these two raters was so high, and they had been concordant with other raters in other studies (between-contexts) and, by extension, concordant over time (within-concordance), similar data would be found by trained raters in this coding system. Thus, data were gathered in fidelity with the coding system and not biased by potential systematic measurement error dues to the rater-effect (Arce, 2017). Besides rater-effect, another systematic source of error may come from the interviewer-effect when data are collected by interview (Arce, 2017; Vilariño, Arce, & Fariña, 2013). However, biases due to differences between interviewers did not contaminate the responses in this case because only one person questioned participants, as prison authorities allowed nobody else to take part in the process. Likewise, the interviewer has proven to be consistent in previous studies (González-Méndez et al., 2014; Padrón, et al., 2014, 2016). Data Analysis Given that the number of participants did not allow multivariate comparisons and that group variances might not be homogenous for some of the variables under analysis, comparisons were made using t-test and ANOVA. Analyses were carried out with the statistical package SPSS v. 21.0. The results from the statistical analyses are described in terms of personal characteristics, criminal and prison variables, and social-relational variables. Personal Characteristics A general statistical relationship between participants’ age at the moment of being interviewed and their early narratives of desistance (concerning identity change, self-efficacy, and will to stop offending) was not observed. However, when the three age groups were compared, significant differences were found in identity change, t(33) = 2.1, p = .043. Those in their thirties have a higher identity change (M = 1.60, SD = 0.50) than those in their twenties (M = 1.28, SD = 0.40). In addition, no significant relationship was found when the indexes of desistance narrative were compared across educational and socioeconomic levels of the participants. Criminal and Prison Variables In relation to criminal variables, significant differences were found for both identity change, t(34) = 2.49, p = .018, and will to desist, t(33.71) = 2.11, p = .042, in relation to the type of offense committed. Those participants sentenced for drug crimes scored higher in early identity change narratives (Mic = 1.66, SDic = 0.51, and Mwd = 1.91, SDwd = 0.28) than those sentenced for robbery (Mic = 1.26, SDic = 0.42, and Mwd = 1.58, SDwd = 0.65). Having or not having previous records as juvenile delinquents was also significantly related both to identity change, t(42) = 2.1, p = .042, and will to desist, t(42) = 1.9, p = .05. Inmates who did not have juvenile records showed a higher score on identity change (M = 1.53, SD = 0.43) than those who did (M = 1.23, SD = 0.48). In addition, participants who did not have juvenile records also showed a greater will to desist (M = 1.85, SD = 0.36) than those who did (M =1.52, SD = 0.75). When sentences as juvenile delinquents had been imposed at 15 years old or older, self-efficacy, t(12.592) = 2.7, p = .018, and will to desist, t(9.000) = 3.20, p = .011, were higher (Mse = 1.78, SDse = 0.26, and Mwd = 2.0, SDwd = 0.00) than when inmates received their first sentence at a younger age (Mse = 1.15, SDse = 0.66, and Mwd = 1.20, SDwd = 0.78). The age at the first prison entry was also related to early identity change narratives, F(2, 43) = 5.82, p = .006. Post hoc comparisons showed significant differences between those who were first imprisoned being older than 26 (M = 1.71, SD = 0.35) in relation to those who were imprisoned between 21 and 25 (M = 1.16, SD = 0.50) and those who were incarcerated younger than 20 (M = 1.31, SD = 0.43). No statistical differences in early identity change narratives were found between the last two groups. However, no statistical associations were found in general terms between early desistance narratives and the length of offenders’ sentences; an exception were offenders sentenced to long prison sentences (11-30 years) that showed a higher will to desist (M = 1.92, SD = 0.26) than participants sentenced to shorter sentences (6-10 years) (M = 1.45, SD = 0.68), t(12.381) = 2.16, p = .05. Concerning prison variables, a significant relationship emerged, F(2, 43) = 3.52, p = .039, when the early change narrative indexes were compared across prison regimes. Post hoc comparisons indicated that inmates in open regime showed a stronger early identity change (M = 1.61, SD = 0.44) than inmates in ordinary/closed regime (M = 1.18, SD = 0.51). Inmates in therapeutic/close regime scored between both previous groups (M = 1.50, SD = 0.36) as shown in Figure 1, but post hoc differences with the other two groups were not statistically significant. Figure 2 Will to Desist Depending on the Stage of the Fulfillment of Prison Sentence (and corresponding Time Spent in Prison).   A noteworthy result in this study shows that the inmates’ stage of sentence completion was also related to the will to desist, F(2, 41) = 3.58, p = .037. Those who were in an initial stage of serving their sentences (imprisoned less than two years) showed a higher will to change (M = 1.93, SD = 0.25) than those who were in an intermediate stage of their sentence (imprisoned between two and five years) (M = 1.47, SD =.71). Those who were in the final stage of sentence completion (imprisoned five or more years) showed a score on withdrawal narrative between the other two groups but the differences were not statistically significant (see Figure 2). Social-Relational Variables Participants were also asked about their reasons for desistance, about who their main sources of emotional support were, and who exerted informal control over them by social bonds. Almost two thirds of participants (73.8% ) who showed the will to desist say that family was their main reason for stopping offending. Those that focused their reasons for desistance exclusively on their family showed a higher perception of self-efficacy (M = 1.81, SD = 0.37) than those focused on other reasons or on a combination of reasons (M = 1.79, SD = 0.41), t(40) = 2.07, p = .044. The combinations of reasons that included family (e.g., family and health, family and offending consequences, family and human goods) were associated with lower levels of self-efficacy when compared to family alone. All participants said that their main emotional support came from their family and that their main social bonds were their intimate partner (47.7%) and/or their children (45.5%). Only 20.5% referred to non-offender friends or to community bonds outside the family, but 79.5% asserted that they had had a job before entering prison. No statistically significant relationship was found between these bonds based on family or other interpersonal bonds and desistance narratives. However, having had or not had a previous job was significantly related to both the narratives of early identity change, t(42) = 2.28, p = .028, and of self-efficacy, t(42) = 2.59, p = .013. Scores were higher in both cases for those who had had a previous job (Mse = 1.57, SDse = 0.40, and Mic = 1.49, SDic = 0.52) than for those who had not (Mse = 1.11, SDse = 0.44, and Mic = 1.11, SDic = 0.69). The main objective of this study is to analyze if early desistance narratives of a sample of 44 imprisoned offenders, distributed in three different prison regimes, are linked to their personal, criminal/prison, and social-relational characteristics. For the evaluation of participants’ early desistance narratives, the non-criminal identity, perceived self-efficacy, and will to desist variables were assessed according to Cid and Martí (2011). Related to the offenders’ personal characteristics, a general statistical relationship between age and early narratives of desistance was not observed. Nevertheless, the older group of participants (those in their thirties) showed, in general, more identity change narratives than the younger group (those offenders in their twenties). This result is consistent, first, with some of the qualitative narratives expressed by participants (not reported in this paper) in the sense that, as a result of their criminal behavior, they have lost many important things (life time, family, wife, children...), have aged and are tired of prison. Secondly, it is also consistent with the expectations derived from the age curve of crime (Loeber & Stearling, 2011; Redondo & Garrido, 2013), i.e., we can expect that both criminal prevalence and frequency will peak during early adulthood and then gradually decline. A probable reason for this fact is that some risk and protective factors, particularly dynamic factors, may be more or less relevant at different ages (Shepherd et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2013). Connected to the idea of dynamic factors is the concept of resilience or individuals’ capacity for not committing a crime despite the adverse factors influencing them (Rutter, 2012; Walker et al., 2013). With regard to criminal and prison variables, some statistical significant relationships with early desistance narratives were observed. Concerning participants’ criminal behavior, those sentenced for drug offenses, those without previous criminal records, and those convicted at a later age scored the highest on early identity change and will in their desistance narratives. Similarly, participants imprisoned at older age show earlier identity change narratives. These characteristics point to a rather circumstantial profile of delinquents, not overly professionalized, who consequently tend to express earlier intentions of not repeating their previous criminal activity. Although in general terms the length of participants’ prison sentences did not show any relation with their early desistance narratives, those with long prison sentences – more aged and probably more tired of prison – specifically showed greater will and decisiveness to abandon criminal activity. Two particularly relevant results concern the relationship between desistance narratives and specific prison variables. First, participants serving prison sentences in open regime showed greater early desistance narratives than those located in an ordinary/closed prison regime. Second, in relation to the stage of the prison sentence, offenders who were at the beginning of their sentence expressed more will to desist than offenders in the intermediate stage. The differences between these two groups and the group of those in the final stage of sentence were no statically significant. Therefore, the apparently curvilinear nature of the relationship between will to desist and imprisonment stage needs further research with larger samples before reaching final conclusions. In order to work with larger samples, which would allow multivariate statistical analysis, interviews would need to be replaced by questionnaires. The role of the correctional system in the process of desistance from crime has not been precisely addressed by previous research because it has been assumed that desistance from crime is a process that exclusively happens away from the criminal justice system (Farrall, 1995). However, narratives of desistance start during prison stays and vary between offenders who are serving their sentences in different ways (Liem & Richardson, 2014). Therefore, the correctional system could support desistance by providing offender with contacts and opportunities for success in the community, not only after but also during sentence completion (Maruna & Toch, 2005). With respect to the social connections claimed by offenders to stop committing crimes, the immense majority mentioned their family as the main reason. In addition, offenders who mentioned the family as the exclusive reason to stop committing crimes scored higher on perceived self-efficacy than those who also mentioned other reasons. Likewise, all the participants considered that their greatest emotional support came from their family and almost half the individuals mentioned their partner and their children as their main sources of social attachment. One of the greatest obstacles ex-offenders face in desistance and social reintegration can be the hostile attitude that society may adopt towards them at the moment of prison release (Campos, Sáez, Sierras, & Yáñez, 2012). Thus, family and informal social support play critical roles as favorable social bonds required for the process of desistance to occur effectively (Cid & Martí, 2011, 2012; de Vries Robbé et al., 2015; Fox, 2015; Laub & Sampson, 2003, 2005). Cid and Martí (2011, 2012) consider that reasons for desistance are part of desistance narratives, and that emotional support and social bonds are transitional factors that enhance and reinforce the creation of that narrative. Finally, offenders who had job experiences prior to entering prison usually showed stronger early narratives of self-efficacy desistance than those without previous vocational experiences. This result is consistent with literature regarding the positive relationship between pre- and post-release community employment and a more probable criminal withdrawal (Alós et al., 2009; Cid y Martí, 2011; Laub & Sampson, 2003, 2005; Martín, Hernández, Hernández-Fernaud, Arregui, & Hernández, 2010; Visher & Travis, 2003). In a forensic context, it has been pointed out that the answers of individuals involved in the judicial system, such as imprisoned offender, may be systematically distorted by hiding negative characteristics (Arce, Fariña, & Vilariño, 2015) and falsely assuming positive ones (Fariña, Redondo, Seijo, Novo, & Arce, 2017). Such distortions would be higher when individuals’ responses have negative consequences for them, as is the case of a worse prison classification or denials of leave permits. However, in this study inmates were told from the beginning that they were volunteering in an investigation carried out by a university research team, independent from the prison staff, and that the information was provided anonymously in the interviews and would not affect their future prison status. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that in these circumstances offenders’ distortions were minimal and that their narratives reflected their genuine thoughts. The variables under analysis in this study concern early narratives and expectations of criminal desistance that cannot be confirmed by actual withdrawal rates, since offenders are still serving prison sentences. This confirmation is out of the scope of the paper, but it might be addressed by future longitudinal research design to assess the final desistance of a sample after at least two years of follow-up. However, although the results do not allow ultimate conclusions on this point, it may still be of interest bearing in mind that offenders’ narratives of desistance do positively influence their actual desistance (Lebel, Burnett, Maruna, & Bushway, 2008). Presumably, this will be the case of many offenders, as suggested by King (2013), since early confidence in their own change is the beginning of the process of future crime disengagement. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Martín, A. M., Padrón, F., & Redondo, S. (2019). Early narratives of desistance from crime in different prison regimes. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11, 71-79. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a2 References |

Cite this article as: Martín, A. M., Padrón, F., & Redondo, S. (2019). Early Narratives of Desistance from Crime in Different Prison Regimes. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11(2), 71 - 79. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a2

ammartin@ull.edu.es Correspondence: ammartin@ull.edu.es (A. M. Martín).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS