Police Records of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Spain: An Eight-year Analysis of Demographic Patterns and Temporal Trends

[Registros policiales de casos de violencia contra la mujer en España: un análisis de los patrones demográficos y las tendencias temporales en un perÃodo de ocho años]

Enrique Gracia1, Pablo Escobar-Hernández1, Antonio López-Quílez1, Miriam Marco1, Marisol Lila1, & Juan J. López-Ossorio2

1University of Valencia, Spain; 2SecretarÃa de Estado de Seguridad, Ministerio del Interior, Madrid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a6

Received 15 April 2025, Accepted 19 May 2025

Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to analyze the demographic patterns and temporal trends of police records of intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) in Spain over an eight-year period. Method: Data were police records of cases of IPVAW in Spain (excluding Catalonia and the Basque Country), recorded between 2016 and 2023 (N = 651,992). Descriptive analysis and analysis of rate differences were conducted for different demographic groups: age, nationality, and urban-rural area. Time series decomposition analyses were conducted to assess change over time, and seasonality for all police records as well as for the demographic groups. Results: Rates of police-recorded IPVAW were significantly higher among younger age groups, among foreign nationals, and in urban areas. Time series analyses showed a significant increase in police-recorded IPVAW over the eight-year period, both in general and for the different demographic groups. A clear seasonal pattern emerged both in general and for the different demographic groups (except for the older age group), with an increase in police-recorded IPVAW in the months of July and August. Conclusions: The increase in police records of IPVAW suggests that the gap between officially recorded and actual prevalence of this type of violence is narrowing in Spain. The high rates of police-recorded IPVAW among younger women and immigrant women support research suggesting that these demographic groups are at greater risk of this type of violence. Seasonal patterns are discussed in terms of changes in behavior during the summer months that seem to increase the risk of IPVAW.

Resumen

Objetivo: El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar los patrones demográficos y las tendencias temporales de los registros policiales de violencia de pareja contra las mujeres (VPM) en España durante un período de ocho años. Método: Los datos fueron registros policiales de casos de VPM en España (excluyendo Cataluña y el País Vasco), registrados entre 2016 y 2023 (N = 651,992). Se ejecutaron análisis descriptivos y análisis de diferencias de tasas para diferentes grupos demográficos: edad, nacionalidad y zona urbana-rural. Se realizaron análisis de descomposición de series temporales para evaluar el cambio en el tiempo, y la estacionalidad tanto para todos los registros policiales como para los diferentes grupos demográficos. Resultados: Las tasas de VPM registradas por la policía fueron significativamente más altas entre los grupos de edad más jóvenes, entre las extranjeras y en las zonas urbanas. Los análisis de series temporales mostraron un aumento significativo de la violencia contra la mujer registrada por la policía a lo largo del periodo de ocho años, tanto en general como para los diferentes grupos demográficos. Apareció un claro patrón estacional tanto en general como para los diferentes grupos demográficos (excepto para el grupo de mayor edad), con un aumento de la VPM registrada por la policía en los meses de julio y agosto. Conclusiones: El aumento de los registros policiales de VPM indica que la brecha entre la prevalencia registrada oficialmente y la prevalencia real de este tipo de violencia se está reduciendo en España. Las elevadas tasas de VPM registradas por la policía entre las mujeres más jóvenes y las mujeres inmigrantes avalan las investigaciones que sugieren que estos grupos demográficos corren un mayor riesgo de sufrir este tipo de violencia. Los patrones estacionales se discuten en relación a los cambios en el comportamiento durante los meses de verano que parecen aumentar el riesgo de VPM.

Keywords

Intimate partner violence, Violence against women, Police records, Age, Nationality, Time series analysis, SeasonalityPalabras clave

Violencia de pareja contra la mujer, Violencia contra la mujer, Registros policiales, Edad, Nacionalidad, Análisis de series temporales, EstacionalidadCite this article as: Gracia, E., Escobar-Hernández, P., López-Quílez, A., Marco, M., Lila, M., & López-Ossorio, J. J. (2025). Police Records of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Spain: An Eight-year Analysis of Demographic Patterns and Temporal Trends. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 59 - 71. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a6

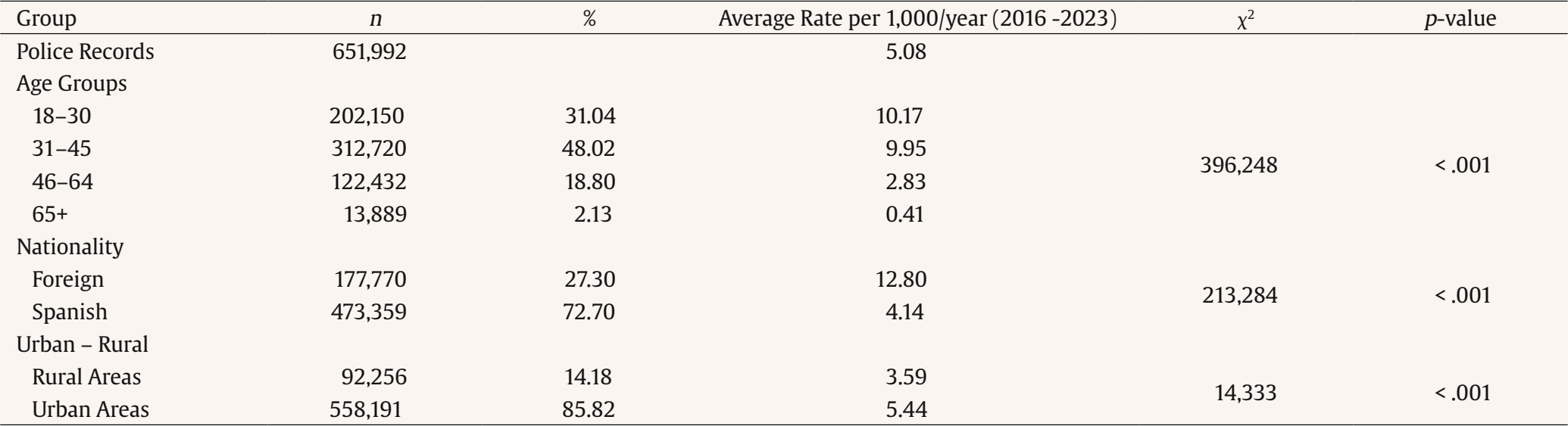

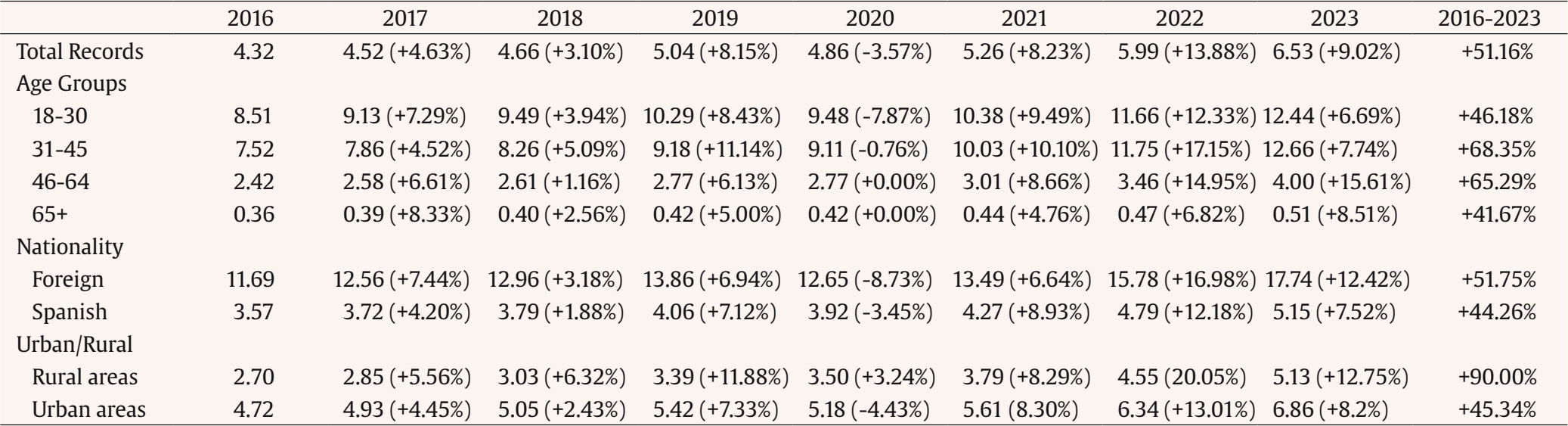

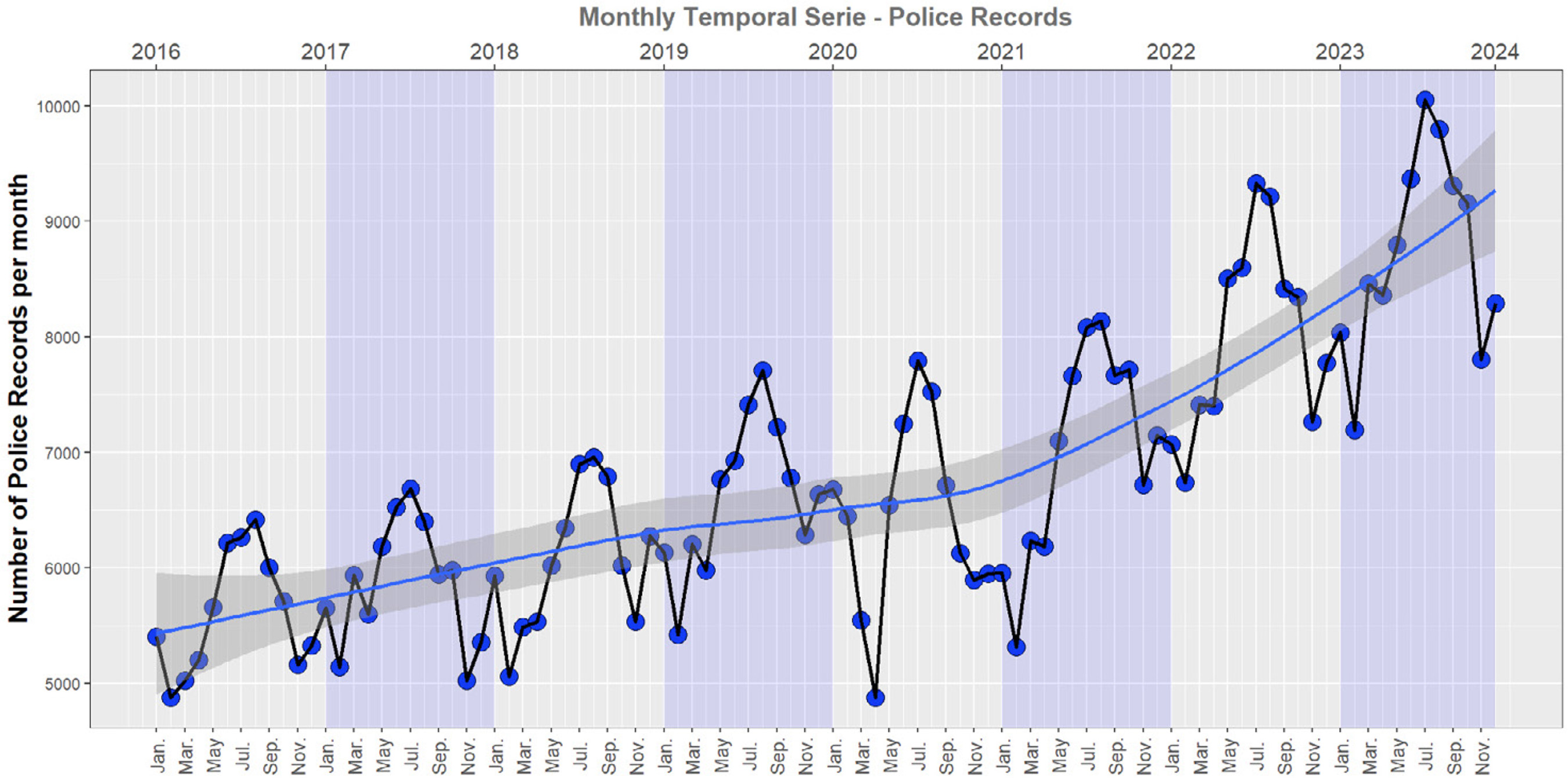

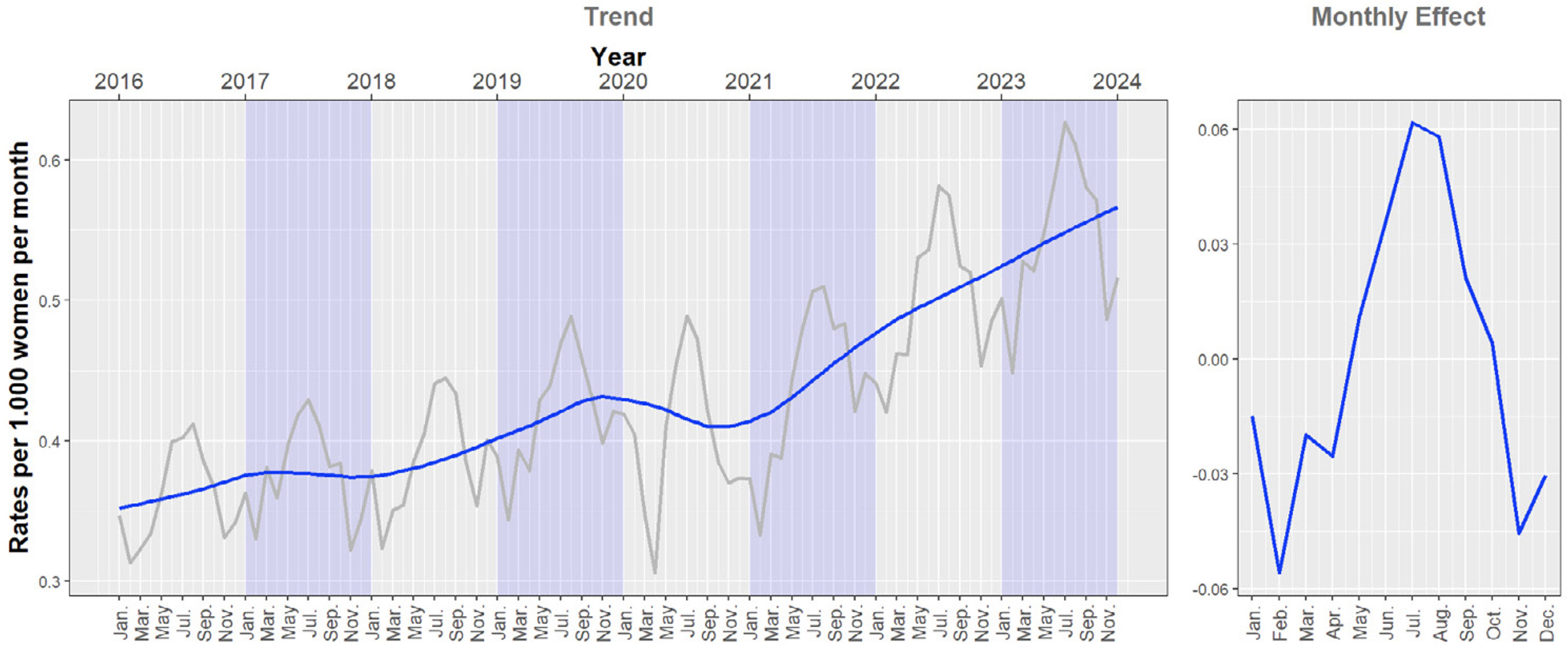

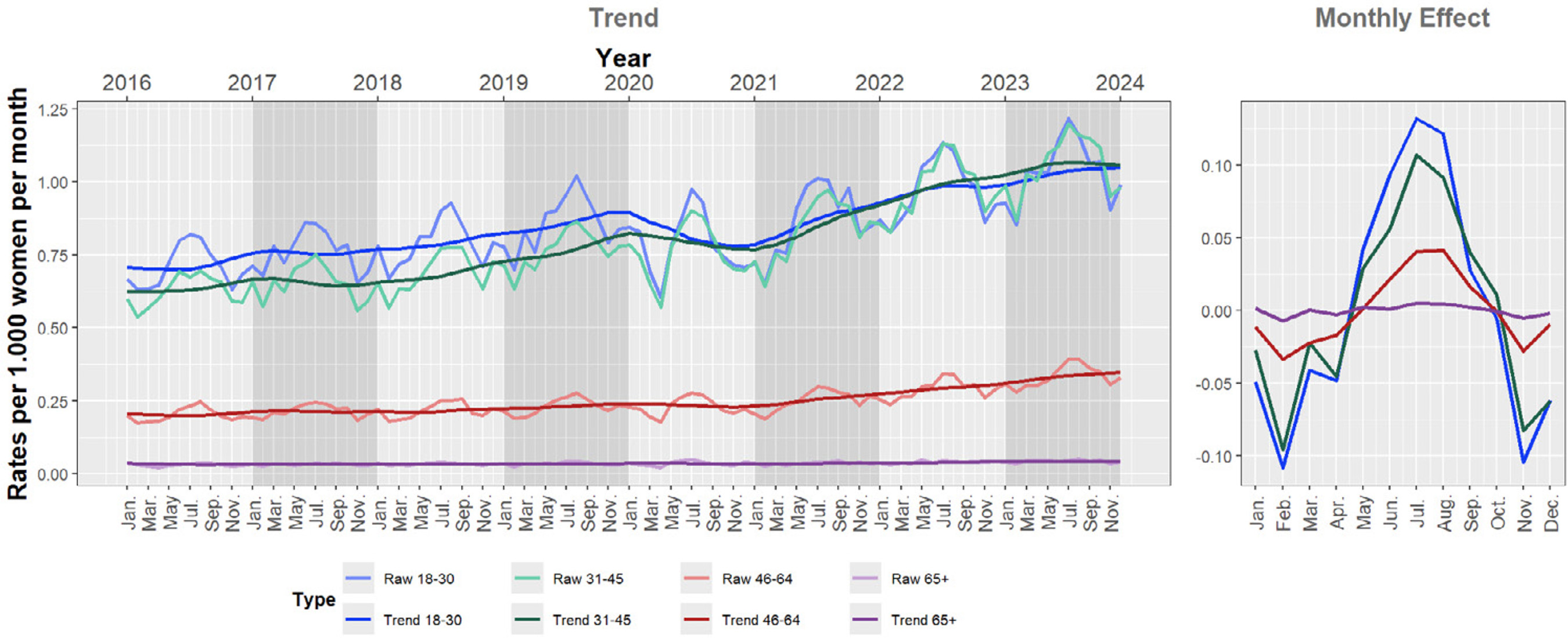

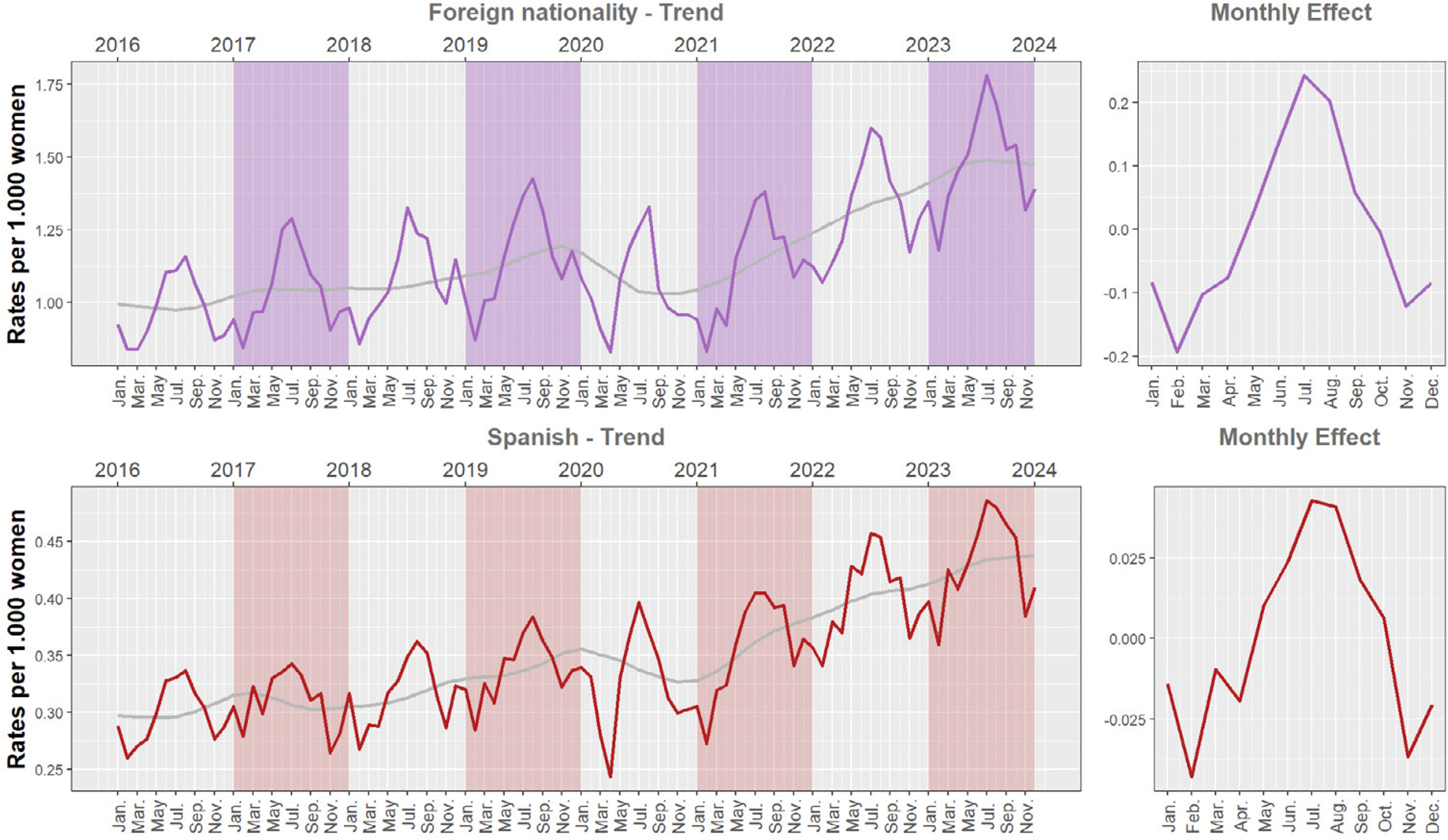

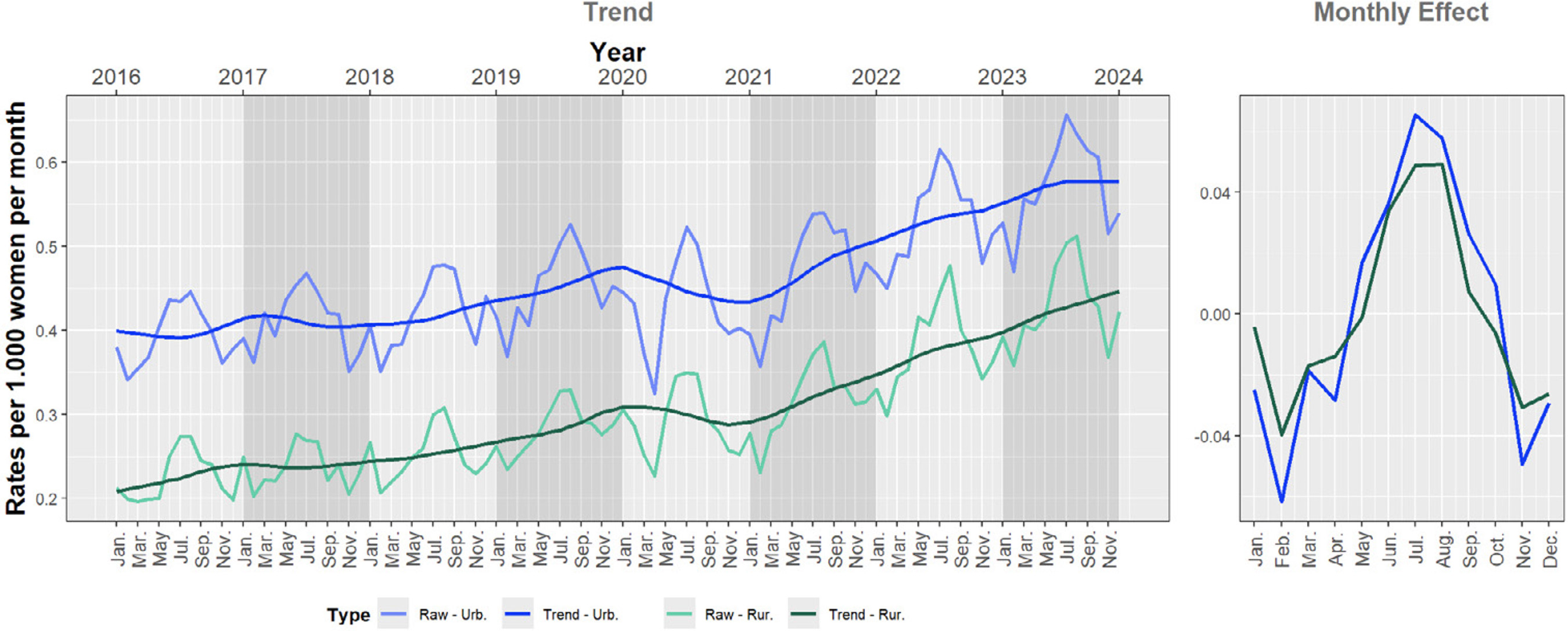

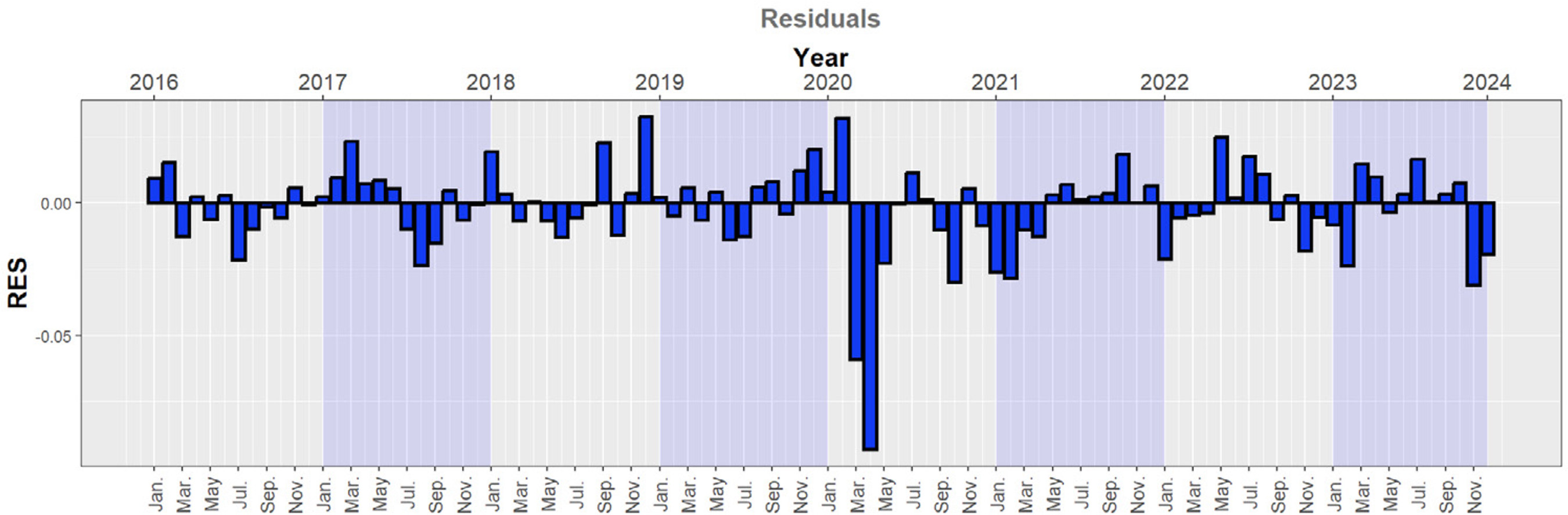

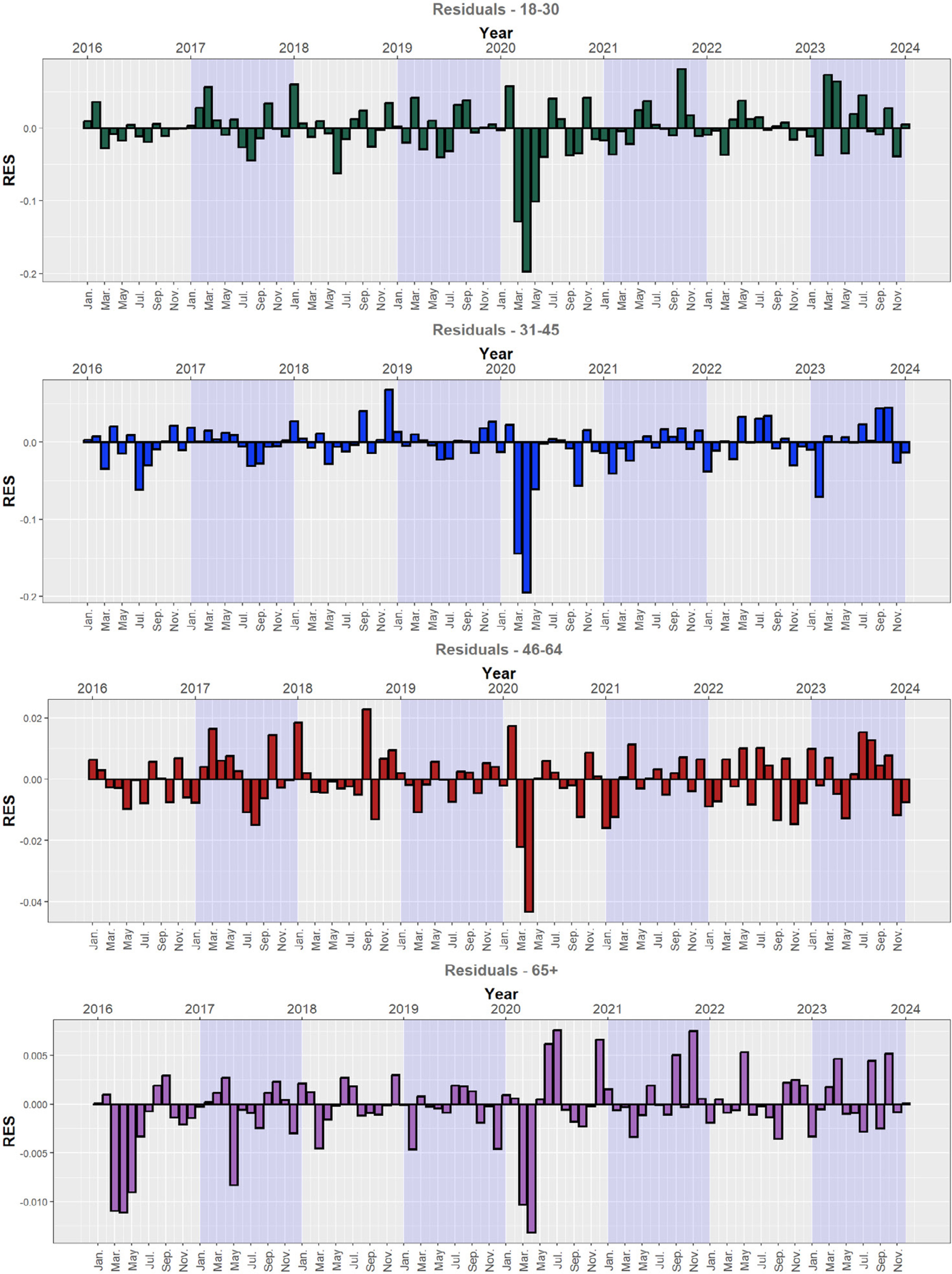

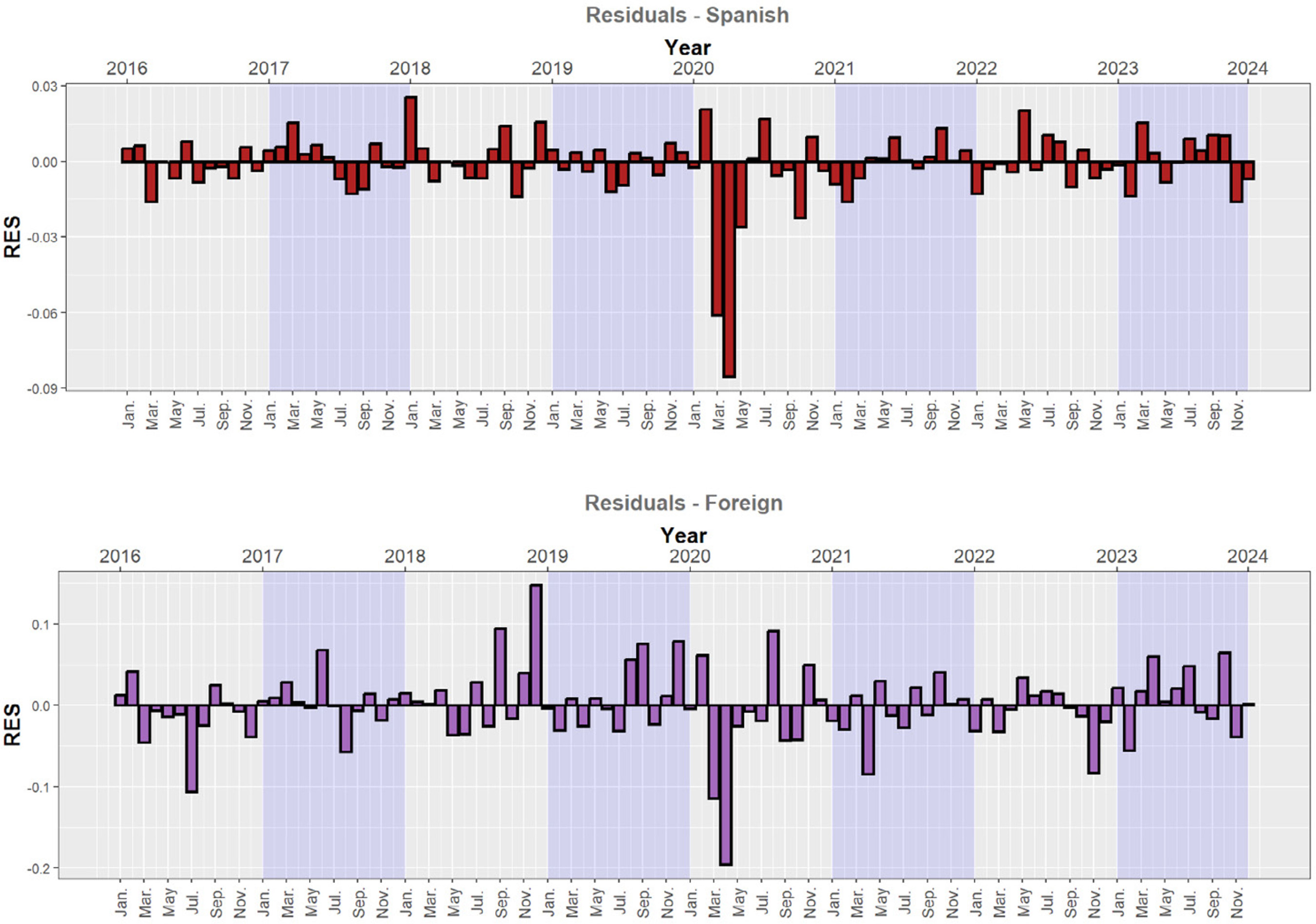

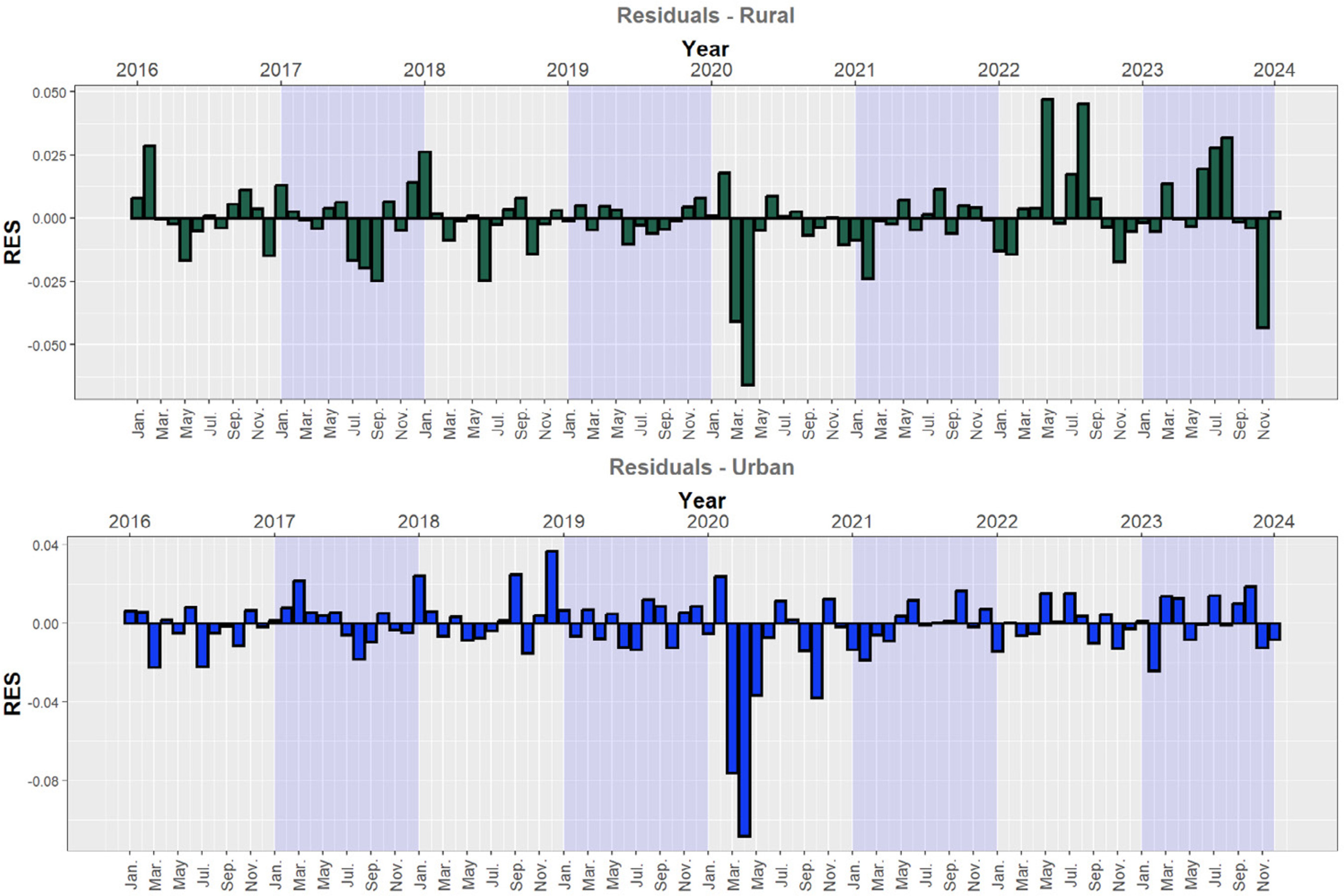

Correspondence: enrique.gracia@uv.es (E. Gracia).The most common form of violence experienced by women is intimate partner violence (IPV), with a global lifetime prevalence estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) at 26% (Devries et al., 2013; Sardinha et al., 2022; WHO, 2021). According to the latest survey on gender-based violence conducted by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA), the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) and Eurostat, in the European Union (EU) an average of 17.7 % of women have experienced physical violence or threats and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime, with prevalence rates ranging from 9.3% to 41.1% across EU countries (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). Although it is important to recognize the current limitations in measuring and reporting psychological violence (WHO, 2021), when psychological violence is included the average prevalence rate of lifetime intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW) in the EU rises to 31.8 % (ranging from 20.5% to 54.6%), and the average prevalence in the past year in the EU is estimated at 5.3% (ranging from 3.5% to 12% across EU countries). In Spain, the country where this study was conducted, the EU survey estimates the lifetime prevalence of IPVAW at 14.4% (28.6% including psychological violence) and 4.1% in the 12 months before the survey (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). This estimated prevalence is similar to that obtained in the last national survey on IPVAW conducted in Spain in 2019 (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2019), which estimated a lifetime prevalence of physical and/or sexual IPVAW of 14.2% (32.4% including psychological violence), and a prevalence of physical and/or sexual IPVAW in the past year of 1.8% (10.8% including psychological violence). These estimates place Spain among the EU countries with the lowest prevalence of IPVAW (Castro et al., 2022; Castro et al., 2024; FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024; Gracia et al., 2019; Martín-Fernández et al., 2019, 2020). The latest Spanish survey also estimated that 32.1% of women who experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former partner reported it to the police or courts (21.7% if emotional violence is included). In this respect, Spain can be considered to have a comparatively high level of reported IPVAW cases since, according to the latest EU survey, on average, only 17.2% of women in the EU who have experienced violence by an intimate partner reported the incident to the police, while in Spain this percentage was 24.6% (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). Police Records of Cases of IPVAW Information on the extent of IPVAW, its characteristics, and its changes over time in our societies comes from two main sources. The first source is the estimated prevalence of IPVAW (either lifetime or in previous years) provided by national or international representative surveys using probability-based methods and usually targeting non-institutionalized populations, such as those discussed above. Despite their methodological limitations, survey-based data on IPVAW could be considered the best approximation of the true extent of the problem in our societies (Bland & Ariel, 2020; FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024; Girard & Higgs, 2023; WHO, 2021). The second source of information is based on police and court records of IPVAW, which reflect cases known to the authorities and are usually included in official statistics. The most obvious limitation of this source is that officially recorded cases of IPVAW reflect only a part of its true dimension. IPVAW in general remains a largely unreported crime, as most incidents do not come to the attention of the police or other law enforcement agencies (Bland & Ariel, 2020; Cho et al., 2023; Falb et al., 2025; Girard & Higgs, 2023; Gracia, 2004; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2024). Nevertheless, and despite their limitations, both survey and officially recorded data on IPVAW should be considered complementary rather than competing sources of information (Falb et al., 2025; FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024, Girard & Higgs, 2023). As the FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat (2024) noted, IPVAW surveys provide detailed information on the nature of the violence and its consequences for women victims, while law enforcement statistics, such as court decisions or IPVAW cases recorded by the police, provide an indicator of how the criminal justice system operates and responds to victims’ needs. Both sources are therefore important for understanding the nature, extent, and trends over time of IPVAW. Police records of IPVAW are a key source of information for researchers, professionals, and policy makers for several reasons. According to Bland and Ariel (2020), police records are the single largest and most consistent source of IPVAW cases available. They provide the main evidence driving key decisions from professionals and law enforcement agencies (police, courts of law, supportive services) that affect victims and offenders. Because victim and offender characteristics can be identified from police records of IPVAW, they are an important source of information for determining level of risk and for guiding criminal justice responses, protective measures, and resource allocation (Bland & Ariel, 2020; Buzawa et al., 2012; Gracia et al., 2014; Klein, 2009; Lila et al., 2019; Rennison et al., 2013). Police records are also one of the primary sources for analyzing IPVAW data patterns (e.g., socio-demographic, geographic, or temporal), which are helpful in designing and better targeting policing strategies and evaluating prevention efforts. In this regard, they also provide an important source for theory building and testing (Bland & Ariel, 2020; Buil-Gil et al., 2022; Gracia et al., 2021; Rennison et al., 2013). Police records of IPVAW also provide an indication of the confidence women have in law enforcement and the criminal justice system (Girard & Higgs, 2023). Finally, police records of IPVAW are also pivotal in determining whether the demographic and temporal patterns of recorded cases of IPVAW are consistent with those observed in national surveys, and the extent to which the gap between recorded and actual prevalence of IPVAW is narrowing. Current Study The aim of this paper is to analyze the demographic patterns and temporal trends of police records of IPVAW in Spain over an eight-year period. Regarding demographic patterns, we will examine differences in police-recorded IPVAW as a function of three demographic characteristics: age, nationality, and the rural-urban divide. These demographic variables have been associated with prevalence rates and risk of IPVAW in surveys and empirical research, and in this study we will examine whether the greater risk of IPVAW among different demographically defined groups also translates into higher rates of police-recorded IPVAW. With regard to age, for example, there is strong evidence that being younger is an important risk factor for IPVAW, with a disproportionately high prevalence among the youngest age cohorts (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024; Gracia et al., 2023; Sardinha et al., 2022, 2024; WHO, 2021; Yakubovich et al., 2018). A substantial body of research also shows that immigrant women are at higher risk of experiencing IPVAW (Hardestyn & Ogolsky 2020; Nesset et al., 2021; Raj & Silverman, 2002; Scheer et al., 2022; Vives-Cases et al., 2009, 2010). With regard to differences in the prevalence of IPVAW between urban and rural areas, the evidence is still sparse and mixed, although a review of the literature suggests that rates of IPVAW are generally similar in rural, urban and suburban areas (Edwards, 2015), and recent survey data indicate that in the EU the prevalence of IPVAW is generally lower in rural areas than in urban areas (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). However, there is broad agreement that women victims of IPVAW in rural areas face more barriers to seeking help and disclosing the violence (Ceccato, 2025; DeKeseredy, 2020; Edwards, 2015; Farhall et al., 2020; Moffitt et al., 2020; Websdale, 1998; Zorn et al., 2017). As for temporal trends, there is evidence of a significant increase in the number of IPVAW-related legal complaints in Spain in recent years (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Perez, 2020). However, questions remain as to whether police-recorded IPVAW has continued to increase in recent years, whether this increase reflects the demographic groups at greater risk (e.g., younger women or immigrant women), and to what extent the gap between police-recorded IPVAW and the actual prevalence of this type of violence is narrowing in Spain. Another relevant research question concerns seasonality in temporal trends detected in police-recorded IPVAW. Criminological research has traditionally pointed to an increase in property and violent crime during the hottest months of the year (Cohn, 1990; Corcoran & Zahnow, 2022; Hipp et al., 2004; McDowall et al., 2012; Michael & Zumpe, 1983; Quetelet, 1842). However, evidence on the seasonality of IPVAW is still scarce and mixed, depending on the data sources used, such as calls to helplines or the police, Google searches, requests for shelter, or recorded legal complaints (Cohn, 1993; Farrell & Pease, 1994; Koutaniemi & Einiö, 2021; Michael & Zumpe, 1983; Sanz-Barberó et al., 2018b). In this study, we will use monthly data over an eight-year period to examine whether police-recorded IPVAW also shows a seasonal pattern. Data The data used in this study were cases of IPVAW (N = 651,992) recorded by the Spanish police forces (i.e., Policía Nacional and Guardia Civil) over an eight-year period (from January 2016 to December 2023). Cases of IPVAW corresponded to crimes that fall under the legal category of gender-based violence. In Spain, according to Organic Law 1/2004 on Integral Protection Measures against Gender Violence, gender-based violence is defined as violence perpetrated by men against women “by those who are or have been their spouses or by those who are or have been linked to them by similar relationships of affection, even without cohabitation [....]. Gender-based violence referred to in this law included all acts of physical and psychological violence, including attacks on sexual freedom, threats, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty.” Therefore, this crime corresponds to the concept of IPVAW perpetrated by male partners or ex-partners. These cases were recorded in the Crime Statistics System of the Secretary of State for Security of the Spanish Ministry of Interior; they included records of both victims’ complaints and proactive police interventions, and represent a stage prior to judicial decisions. For this study, we used an anonymized dataset of cases of IPVAW recorded by the police, provided through an agreement between the Spanish Secretary of State for Security and the University of Valencia. The dataset did not include police records of cases of IPVAW in Catalonia and the Basque Country, as these autonomous communities have their own police forces and registries to deal with these cases. Variables Demographic Variables In this study, we use the following demographic information about the victims of IPVAW available in the anonymized dataset (information about the perpetrators was not available). Age. All IPVAW cases for this study were women of legal age (18+). The anonymized dataset grouped the victims into four age groups, based on the Spanish Crime Statistics System, as follows: 18-30 years, 31-45 years, 46-64 years, and 65+ years. Nationality. The nationality of foreign victims was provided by continent: 46% of the IPVAW cases were from America, 36% from Europe, 16% from Africa, and 2% from Asia and Oceania. As the specific country of origin was not available in the anonymized dataset, and given the wide heterogeneity within the continental groupings and their limited representativeness, for the purpose of this study we classified the nationality into two categories: Spanish nationality and foreign nationality. Rural-Urban Area. The location of the victim at the time of the incident that led to the police record of the IPVAW case was classified as either rural or urban according to the criteria established by the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE): a rural area was defined as a municipality with fewer than 10,000 inhabitants, while an urban area was defined as a municipality with 10,000 or more inhabitants. Temporal Units of Analysis and Rates of IPVAW The dataset included the date of the police record of each IPVAW case. For this study, the temporal units of analysis were the year and month when the IPVAW case was recorded. Rates of police-recorded cases of IPVAW relative to the female population were also calculated annually and monthly. Rates for both months and years were calculated as follows: monthly rates were calculated by dividing the total number of cases per month by the annual female population in Spain, multiplied by 1,000 (monthly population data were not available); yearly rates were calculated by dividing the total number of cases per year by the annual female population in Spain, multiplied by 1,000. Annual female population data were obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE, 2024]). Statistical Analysis First, a descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the distribution of police-recorded cases across different demographic groups. Specifically, the number, percentage, and average rate per 1,000 women per year of police records of IPVAW cases were calculated for each age group, nationality (Spanish or foreign nationality), and rural-urban area. The χ² goodness-of-fit test was used to determine whether the distribution of police-recorded IPVAW rates differed significantly across demographic groups. This test assesses whether the observed differences in frequencies between groups differ from what would be expected if they were proportional to the population in those groups. The descriptive analysis also included an examination of the annual rates of police-recorded IPVAW from 2016 to 2023. For each year, the annual rate was calculated, and the percentage variation between consecutive years was determined to analyze yearly fluctuations in recording patterns. In addition, the monthly trends in police-recorded IPVAW rates were visually represented to explore temporal fluctuations. Second, a time series decomposition approach using LOESS (locally estimated scatterplot smoothing; Cleveland et al., 1990) was applied to analyze the underlying components of police-recorded IPVAW data. The decomposition process separated the observed data into three key components: the general trend, the seasonal effect, and the residuals. The general trend represents the long-term direction of police-recorded IPVAW rates. The seasonal effect captures recurring monthly fluctuations in police-recorded IPVAW rates, which are indicative of seasonal patterns. The residuals indicate random fluctuations that are not explained by the trend or seasonality. This decomposition was performed not only for the total population but also separately for the different demographic categories, namely age group, nationality, and urban-rural area. By conducting the decomposition at multiple levels, we were able to assess whether the general trends and seasonal effects varied across these subgroups. All statistical analyses and visualizations were conducted using R. Demographic Patterns Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and the results of the χ² tests assessing differences in rates of police-recorded IPVAW across demographic groups from 2016 to 2023. The average rate of police records of IPVAW per 1,000 women over the eight-year period was 5.08. Table 1 Descriptive Statistics and Chi-square Tests for Differences in Rates of Police-Recorded IPVAW by Demographic Variables (Spain, 2016-2023)   Note. N represents the number of cases; the percentage column (%) indicates the proportion of cases within each group; rates are expressed as the average over the eight-year period per 1,000 women per year; chi-square (χ2) tests assess differences in IPVAW police report rates between subgroups. With respect to the victims’ age, almost 80% of all police-recorded cases of IPVAW involved women in the younger age groups (18-30 and 31-45). Over the eight-year period, the average rate of police-recorded IPVAW cases was highest among the younger age groups, with rates of 10.17 (18-30) and 9.95 (31-45) per 1,000 women. In contrast, the rates for the older age groups (46–64 and 65+) were substantially lower at 2.83 and 0.41, respectively. A chi-square test confirmed significant differences between age groups (χ² = 396,248, p < .001), and post hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated that all pairwise differences were statistically significant. Regarding nationality, 27.30% of all IPVAW cases recorded by the police involved women of foreign nationality. Over the eight-year period, the average rate of police-recorded IPVAW cases was significantly higher (χ² = 213,284, p < .001) for women of foreign nationality (12.80 per 1,000 women per year) than for Spanish women (4.14 per 1,000 women per year). Finally, the majority of police-recorded IPVAW cases (85.82%) occurred in urban areas. Over the eight-year period, the average rate of police-recorded IPVAW cases was higher in urban areas (5.44 per 1,000 women per year) than in rural areas (3.59 per 1,000 women per year). The difference was statistically significant (χ² = 14,333, p < .001). Temporal Trends Table 2 shows the annual rates of IPVAW cases recorded by the police and their percentage variations across different demographic groups over the eight-year period. Overall, there was a 51.16% increase in the rates of police-recorded cases of IPVAW between 2016 and 2023. An increase in the rates of police-recorded IPVAW was observed across all age groups over the eight-year period. However, this increase was particularly pronounced in the 31-45 and 46-64 age groups, with percentage increases of 68.35% and 65.29%, respectively. In contrast, the 18-30 and 65+ age groups exhibited comparatively smaller increases of 46.18% and 41.67%, respectively. Foreign women showed a greater increase in rates of police-recorded IPVAW (51.75%) compared to Spanish women (44.26%). In rural areas, the increase in rates of police-reported IPVAW over the eight-year period was more pronounced (90%) than in urban areas (45.34%). Table 2 Annual Rates of Police-Recorded IPVAW Cases and Percentage Variations by Demographic Variables (Spain, 2016-2023)   Note. Rates are expressed per 1,000 women; the percentage in parentheses indicates the variation compared to the previous year; the total percentage variation (last column) represents the cumulative change from 2016 to 2023. In every year of the study period, rates of police-recorded IPVAW increased on the previous year, with the exception of 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, which may explain the observed decline in rates across all demographic groups, except for rural areas where there was a slight increase of 3.24%, and the 46–64 and 65+ age groups, where rates remained stable. The most substantial decrease in 2020 was observed among women aged 18-30, with a decrease of 7.87%, and among foreign women, with a decrease of 8.73%. By 2021, police-recorded IPVAW rates had resumed their upward trend across all demographic groups. Figure 1 shows the monthly trends in police-recorded IPVAW cases in Spain between 2016 and 2023. There was a general increase over the 96-month period, although this increase was not uniform, with noticeable fluctuations between months. The data also showed a substantial decrease in March and April 2020, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. After these months, the upward trend in police-recorded IPVAW cases resumed. Figure 1 Monthly Trends of Police-recorded IPVAW (Spain, 2016-2023)   Note. The dots represent the actual number of police records of IPVAW cases per month; the blue line indicates the adjusted trend, while the shaded gray area represents the 95% confidence band of the adjusted trend. Figures 2 through 5 display the results of the time series decomposition for each demographic group, highlighting the trend and seasonal components. To maintain clarity and focus in the main text, the residuals are included in the Supplementary Material. Figure 2 Monthly Trends and Seasonal Effects of Police-recorded IPVAW Rates (Spain, 2016-2023).   Note. The left panel displays the monthly trends in rates of police-recorded IPVAW per 1,000 women per month; the gray line represents the raw data, while the blue line indicates the overall trend; the right panel illustrates the monthly effect (seasonality). Figure 3 Monthly Trends and Seasonal Effects of Police-recorded IPVAW Rates by Age Group (Spain, 2016-2023).   Note. The left panel shows the monthly trends in rates of police-recorded IPVAW per 1,000 women for each age group; the light-colored lines represent the raw data, while the dark-colored lines indicate the overall trend for each group; the right panel illustrates the monthly effect (seasonality) for each age group. Figure 4 Monthly Trends and Seasonal Effects of Police-recorded IPVAW Rates by Nationality (Spain, 2016-2023).   Note. The left panels show the monthly trends in rates of police-recorded IPVAW per 1,000 women for foreign (top) and Spanish women (bottom); colored lines represent the raw data, while gray lines indicate the overall trend; the right panels illustrate the monthly effect (seasonality) for foreign (top) and Spanish women (bottom); the data is presented in separate graphs due to the substantial difference in rates between foreign and Spanish women. Figure 5 Monthly Trends and Seasonal Effects of Police-recorded IPVAW Rates by Urban and Rural Areas (Spain, 2016-2023).   Note. The left panel shows the monthly trends in rates of police-recorded IPVAW per 1,000 women for urban and rural areas; light-colored lines represent the raw data, while dark-colored lines indicate the overall trend; the right panel illustrates the monthly effect (seasonality) for urban and rural areas. Figure 2 shows the general trends in police-recorded IPVAW cases, alongside the seasonal effects. The results show a sustained upward trend, with a slight decrease in the middle of 2020, but with notable monthly fluctuations, particularly peaking in July and August. Figure 3 shows the time series decomposition for the age groups. The presence of seasonality was observed in all age groups, with peaks in July and August, with the exception of the 65+ age group, which did not show a clear seasonal pattern. For this particular age group, the trend remained relatively constant over the months. The time series decomposition for nationality groups (Figure 4) and rural-urban areas (Figure 5) showed similar patterns. Foreign and Spanish women, and rural and urban areas, showed trends consistent with the overall data pattern (upward trend and peaks in July and August). In this paper we aimed to analyze the demographic patterns and temporal trends of police records of IPVAW in Spain over an eight-year period. Using IPVAW cases recorded by the police between 2016 and 2023, the results showed that rates of police-recorded IPVAW followed distinctly different patterns as a function of the three demographic characteristics analyzed (i.e., age, nationality, and urban-rural context), with a significant overall increase over the eight-year period analyzed and a marked monthly seasonal pattern for most demographic groups. Demographic Patterns Regarding age, it is worth noting that almost 80% of all IPVAW cases recorded by the police between 2016 and 2023 corresponded to the younger age groups (18-30 and 31-45). In terms of the average rate per 1,000 women in each age group over the eight-year period, police-recorded IPVAW was significantly higher for the younger age groups (18-30 and 31-45, with rates of 10.17 and 9.95 respectively) than for the older age groups (46-64 and 65+, with rates of 2.83 and 0.41 respectively). This finding is consistent with a large body of research and survey data indicating that the prevalence of IPVAW is higher among younger age groups (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024; Gracia et al., 2023; Sardinha et al., 2022, 2024; WHO, 2021; Yakubovich et al., 2018). For example, the EU 2024 survey found that the prevalence of IPVAW was higher among the youngest group of respondents (35.8%) than in any other age group (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). In Spain, a secondary analysis of the 2019 National Survey on IPVAW found that the highest prevalence rates of physical, sexual, and psychological IPVAW in the past four years and in the past year were among the youngest age group (women aged 18-24). For lifetime prevalence, the youngest age group showed the highest prevalence rates for psychological and physical IPVAW (18-24 years) and women aged 25-34 years for sexual IPVAW (Gracia et al., 2023). What our study adds to this body of research is that in Spain, the higher risk of IPVAW among younger age groups is also reflected in higher rates of police-recorded IPVAW among these groups, suggesting a parallel pattern between estimated and recorded IPVAW. However, it is important to note that although survey data suggest that the prevalence of IPVAW is highest in the youngest age groups (Arrojo et al., 2024; FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024; Sardihna et al., 2024; WHO 2021; Wincentak et al., 2017), in our study the average rate of recorded cases for the eight-year period was similar for the two younger age groups (10.17 vs. 9.95), suggesting that the rate of unreported cases of IPVAW may be higher in the youngest age group. In terms of nationality, our results showed that 27.30% of all IPVAW cases recorded by the police involved women of foreign nationality, with more than 80% of them of American and European nationality (most immigrants in Spain come from Latin American and European Union countries), which is clearly disproportionate given that the weight of the foreign population in Spain as of January 2024 was 13.4% (INE, 2024). This is also illustrated by the rates per 1,000 women over the eight-year period, as rates of police-recorded IPVAW were more than three times higher for women of foreign nationality (12.80) than for Spanish women (4.14). This finding suggests that police records reflect the higher prevalence of IPVAW among immigrant women that has been observed in numerous studies and surveys. A substantial body of research shows that immigrant women, like other ethnic minority and marginalized women’s populations, are at a disproportionately high risk of experiencing IPVAW (Hardesty & Ogolsky 2020; Nesset et al., 2021; Raj & Silverman, 2002; Scheer et al., 2022; Vives-Cases et al., 2009; Vives-Cases et al., 2010). For example, the 2019 Spanish survey estimated that the percentage of women who had been victims of physical and/or sexual IPVAW in their lifetime was twice as high for immigrant women (24.7%) than for Spanish women (12.7%), with the percentage reaching 45.6% for non-Spanish women and 29.9% for Spanish women for psychological violence (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2019). However, our findings do not support other studies suggesting that rates of reporting IPVAW to law enforcement agencies are lower for immigrant women than for the native population (Couture-Carron et al., 2022; Hulley et al., 2023; West, 2016). A number of researchers have suggested that the barriers to seeking help and leaving the relationship (including reporting the violence to the police or courts) that all IPVAW victims face tend to be exacerbated for immigrant women (e.g., fear of deportation, fear of economic consequences or retaliation, cultural pressures), which would translate into lower rates of police records or legal complaints (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Perez, 2020; FRA, 2014; Reina et al., 2014; Sanz-Barberó, Otero-García et al., 2018). In contrast, our results showed that the greater vulnerability and risk of IPVAW among immigrant women appears to be reflected in higher rates of police records, supporting other studies and surveys conducted in Spain that indicate that immigrant women are more likely to report violence perpetrated by their partners (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, 2023; Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2019; Vives-Cases et al., 2009). For example, estimates from the last national survey on IPVAW in Spain (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2019) showed that women of foreign nationality (28.6%) were more likely to report IPVAW to the police or courts than Spanish women (20.0%). According to the 2023 report of the Spanish General Council of Justice (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, 2023), 34.98% of all IPVAW legal complaints involved immigrant women victims (with 35.3% of reported perpetrators also of foreign nationality). This high percentage of reported IPVAW among immigrant women may also reflect the guarantees and resources for the protection of women from this particular population in Spain, which increases trust in the police and other law enforcement agencies and facilitates reporting. In terms of the rural-urban divide, 85.82% of all IPVAW cases recorded by the police were in urban areas, although this high percentage provides a distorted picture given the concentration of the population in urban areas. In relation to the population living in rural and urban areas, the differences in the rates of IPVAW cases recorded by the police per 1,000 women over the eight-year period were not large, although they were significantly higher in urban areas (5.44) than in rural areas (3.59). This finding is consistent with survey data, which indicate that, on average, the prevalence of IPVAW is lower in rural areas than in urban areas in the EU and Spain. For example, in the 2024 EU survey, the estimated prevalence in Spanish cities and towns ranged between 27.5% and 30.5%, while the prevalence in rural areas was estimated at 23.7% (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). The 2019 Spanish National Survey estimated a lifetime prevalence of physical and/or sexual IPVAW of 11.2% in municipalities with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants and 15.3% in cities with more than 10,000 inhabitants (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2019). Again, the differences in police-recorded IPVAW between rural and urban areas reflect the differences in prevalence between these contexts and, although they do not reflect all cases of IPVAW, they suggest a parallel pattern between estimated and recorded IPVAW that is reflected in our findings. Notwithstanding the fact that many cases of IPVAW in both rural and urban areas remain unreported to the police, there is broad agreement among scholars that victims of IPVAW in rural areas face more barriers to seeking help and making violence visible by reporting it to the police, including social isolation, issues of confidentiality and anonymity, a code of silence and non-interference in the community, fear of retaliation, or lack of resources and support services (Ceccato, 2025; DeKeseredy, 2020; Farhall et al., 2020; Moffitt et al., 2020; Websdale, 1998; Zorn et al., 2017). However, as we discuss below when looking at trends over time, the rates of IPVAW cases recorded by the police in rural areas have been increasing in recent years, suggesting that these barriers are diminishing or becoming easier to overcome. Temporal Trends The annual analysis of the overall rate per 1,000 women of IPVAW recorded by the police showed a substantial increase of 51.16% over the eight-year period. This supports the view that in Spain police-recorded IPVAW has been increasing in recent years (Bosch-Fiol & Ferrer-Perez, 2020). According to Bosch-Fiol and Ferrer-Perez (2020), this increase may be the result of changes in the legal framework, broader criteria for filing complaints and collecting information on IPVAW cases, and changes in societal attitudes and the demographic profile of the Spanish population. This increase also supports the view that Spain is a country with comparatively high levels of police-reported IPVAW. According to the latest national survey on IPVAW, it is estimated that in Spain almost one in three serious cases of IPV (sexual and physical), or one in five if emotional violence is included, are reported to the police (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2019). This is in line with EU survey data, which estimated that in Spain 24.6% of women who experienced violence by an intimate partner reported the incident to the police, compared to the EU average of 17.2% (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). The increase in police-recorded IPVAW that we observed over the eight-year period also suggests a narrowing of the gap between recorded and actual prevalence of IPVAW. Survey prevalence data over the last decade suggest a slight increase in physical and/or sexual IPVAW in Spain of around two percentage points, from a lifetime prevalence of 12.5% in 2015 to 14.2% in 2019 (Delegación del Gobierno para la Violencia de Género, 2015, 2019) and 14.4% in 2024 (FRA, EIGE, and Eurostat, 2024). However, the increase of more than 50% in IPVAW recorded by the police over the eight years analyzed suggests that the number of unreported cases of IPVAW is decreasing, indicating that the gap between recorded and actual prevalence is gradually closing in Spain. The increase in rates of IPVAW cases recorded by the police over the eight-year period was observed across all demographic groups, although with some variation. For example, although the increase was observed for all age groups, it was greater for the 31-45 and 46-64 age groups (68.35% and 65.29%, respectively) than for the youngest and oldest age groups (18-30: 46.18% and 65+: 41.67%). There were no large differences in the increase in rates of police-recorded IPVAW between Spanish (44.26%) and foreign women (51.75%), although the increase was greater for foreign women, supporting the view discussed above that the higher risk of IPVAW among immigrant women is also reflected in higher rates of reporting. With regard to the rural-urban divide, it is worth noting that the increase in the rate of cases recorded by the police in rural areas over the eight-year period reached 90%, almost twice the rate in urban areas (45.34%). As discussed above, this suggests that the barriers rural women have historically faced in seeking help and disclosing violence are gradually falling (Ceccato, 2025; DeKeseredy, 2020; Edwards, 2015; Farhall et al., 2020; Moffitt et al., 2020; Websdale, 1998; Zorn et al., 2017). Analysis by year showed that only in 2020 did rates of police-recorded IPVAW decrease from the previous year across all demographic categories (except older age groups and rural areas). This decrease, as the monthly analysis of all police records revealed, could be attributed to the COVID-19 lockdown, especially in the months of March and April of 2020. Although there have been discrepancies in the available research regarding the increase or decrease in police-reported IPVAW during COVID-19 (Hammett et al., 2025; Nesset et al., 2021), our findings are consistent with other studies that found a significant decrease in reported cases of IPVAW during the initial lockdown period (Baidoo et al., 2021; Miller, 2022; Moore et al., 2021; Vives-Cases et al., 2021). However, our results show that after these initial months, the trend continues to follow the general increasing pattern. The nature of our data does not allow us to answer the question of whether this decrease reflected a lower incidence of IPVAW or a change in help-seeking patterns among victims during the lockdown (Moore et al., 2021). A more detailed analysis of temporal patterns revealed that the increase in IPVAW cases recorded by the police over the 96 months of the eight-year period was not constant, but showed variations over the months, suggesting the possibility of a seasonal pattern. To explore this possibility, we conducted a time series decomposition analysis for the monthly rates of overall police-recorded IPVAW in Spain, as well as for the different demographic groups. The results showed that in addition to the general increasing trend over the eight-year period in the rates of IPVAW recorded by the police, there were significant monthly fluctuations, with a marked peak in the months of July and August. This was the case for the overall monthly time series, but this monthly effect was also observed for the different demographic groups: Spanish and foreign women, rural and urban areas, and all age groups, except for the 65+ age group, for which no seasonality was observed. Our results are in line with the general criminological literature, which has traditionally observed an increase in violent crime during the hottest months of the year (Cohn, 1990; Corcoran & Zahnow, 2022; Hipp et al., 2004; McDowall et al., 2012; Michael & Zumpe, 1983; Quetelet, 1842). Our findings also partially support other studies that find increases in domestic violence and IPVAW during the summer months (Farrell & Pease, 1994; Michel & Zumpe, 1986), although these and other studies also report increases during the Christmas holidays and weekends (Farrell & Pease, 1994; McDowall et al., 2012; Sanz-Barberó et al., 2018b). However, our study is the first to include police-recorded cases of IPVAW in recent years, providing strong evidence on the current seasonal patterns of this type of violence against women in Spain. Explanations for the increase in crime during the summer months have traditionally been grounded in the temperature-aggression theory and the routine activity theory (Delgado & Sánchez-Delgado, 2023; Kim & Wo, 2022; McDowall et al., 2012). In the field of IPVAW, however, the theory of routine activities seems to offer a more comprehensive approach to seasonality (Cohen & Felson, 1979; McDowall et al., 2012). As Kim and Wo (2022) noted, seasonality is less about temperature variations over the calendar year, but more about the changing nature of routine activities. According to McDowall et al. (2012), individual behaviors and social activities can be structured by temporal cycles, and these temporally patterned social behaviors and activities can independently produce seasonal variations in crime. In this regard, changes in behavioral patterns during the summer months are likely to be one of the key factors explaining the increase in police-recorded IPVAW. During the summer months, there is an increase in cohabitation which provides more opportunities for conflict and, together with other risk factors such as greater alcohol consumption, and higher levels of irritability and stress, may increase the risk of IPVAW (Hipp et al., 2004; Sanz-Barberó et al., 2018a, 2018b). This could also be a possible explanation for the lack of seasonality we found for the 65+ age group, as cohabitation tends to be more stable after retirement. Policy Implications This study provides some important insights with practical implications. Firstly, our findings show a correspondence between the demographic groups with higher rates of police-recorded IPVAW and those demographic groups that research and survey data have shown to have a higher prevalence of this type of violence (i.e. younger age groups and immigrant women). This parallel pattern suggests that police-recorded IPVAW is a good indicator of the demographic groups at greater risk and can therefore be considered a useful tool for defining intervention strategies, allocating resources, and monitoring progress in prevention policies, as it can provide consistent, reliable and timely information not only on who is the victim of this type of violence, but also on how, when and where this type of violence occurs (Bland & Ariel, 2020; Gracia et al., 2009, 2021; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2024). Second, this study shows a clear increase in the number of IPVAW cases recorded by the police over the eight-year period analyzed, which, as discussed above, suggests that the gap between the actual prevalence and recorded cases of IPVAW is gradually closing. Since IPVAW remains largely underreported, and cases known to police and other law enforcement agencies have traditionally been considered the tip of the iceberg, increasing the number of officially recorded cases of IPVAW is therefore key to increasing the visibility of the hidden part of the iceberg. Policies, awareness-raising campaigns, and educational strategies aimed at increasing the reporting of IPVAW cases are important to this end and should target not only women victims but also key institutional sectors (e.g. health and education), communities, and the social environment of victims (Bland & Ariel, 2020; Falb et al., 2025; Gracia et al., 2021; Gracia et al., 2024). Policies aimed at increasing the reporting of IPVAW incidents to law enforcement authorities are particularly important for a number of reasons. Reporting is key to the protection and safety of women victims (and their children), as it can initiate actions against perpetrators that can prevent revictimization and act as a deterrent (e.g., protection orders and prosecution). Reporting is also the first step that allows for the initiation of support measures and services for women’s recovery and well-being (Baumer, 2010; Bland & Ariel, 2020; Gracia et al., 2014), as well as for re-education programs to prevent perpetrator recidivism, thus preventing further victimization (Expósito-Álvarez et al., 2023, 2024; Lila & Gilchrist, 2023; Lila et al., 2019; Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2024). Increased reporting of IPVAW is also important to increase public confidence in the role of the police and other law enforcement agencies in protecting women (Baumer & Lauritsen, 2010; Girard & Higgs 2023; Rennison et al., 2013). Finally, our findings on seasonality point to an increase in police-recorded IPVAW during the summer months, as changes in behavioral patterns during this period seem to exacerbate the risk of violence, which should be taken into account to better allocate resources and design specific intervention and prevention strategies to address this excess risk. Limitations Our findings should also be interpreted in light of the limitations of the present study. The most obvious limitation is the use of data reflecting only those cases of IPVAW that have been recorded by the police, which limits the extent to which our findings regarding demographic patterns and temporal trends can be generalized to cases of IPVAW that are not known to the authorities. However, because our study showed that the demographic patterns of cases recorded by the police mirror those identified in research and prevalence data, we are confident that our findings nonetheless provide important evidence that furthers understanding of this social problem. Also, the data used do not reflect all cases known by law enforcement agencies, such as those reported directly to the courts. However, this does not represent a major bias in our dataset, as the number of IPVAW cases reported directly to the courts in Spain is relatively small at around 9% (Consejo General del Poder Judicial, 2023). Another limitation is that our data set included all cases of IPVAW recorded by the two main police forces in Spain (Policía Nacional and Guardia Civil). The data did not include police-recorded cases of IPVAW in two autonomous communities (Basque Country and Catalonia), as these are handled by their own autonomous police forces, and generalizations to these Spanish regions should be made with caution. Nevertheless, our study covers cases from 15 of the 17 autonomous communities in Spain, representing approximately 80% of the country’s population. Another limitation is that the anonymized dataset we had access to for this study lacks some information that could have shed light on some relevant issues, such as other socio-demographic characteristics of the women victims (education, economic status, single or married, presence of children, etc.), the type of IPVAW (physical, sexual or psychological), the severity of the violence, whether the recorded case was a single incident or a revictimization, or whether the case resulted in a successful prosecution. Also, the study refers only to intimate partner violence perpetrated by men against women, as this is the specific legal category based on the Spanish legal framework on gender-based violence reflected in our data set. The study does not include other types of violence between partners, such as violence perpetrated by same-sex partners, violence perpetrated by women against men, or mutual violence, all of which are registered under other legal categories that are not included in the dataset used for this study. Finally, the use of a single category for the rural contexts is another limitation. There are notable differences between rural contexts, as some areas are more remote while others are closer to large populations, and significant variations arise depending on the type of economy (e.g., agricultural vs. natural resource-based or tourism-based) or population patterns (declining vs. growing). These variations are associated with different realities and experiences for women, both in general and in relation to IPVAW, which in turn may influence differences in prevalence and recorded IPVAW across rural contexts (Anderson et al., 2017; Ceccato, 2025; Edwards 2015; Kaukinen et al., 2018; Lanier & Maume, 2009; Perreault, 2023). Conclusions Police records are an important source of information for researchers, professionals and policy makers alike. In this study, we analyzed the demographic patterns and temporal trends of cases of IPVAW recorded by the police in Spain over an eight-year period. Our findings revealed different patterns of police-recorded IPVAW as a function of the demographic characteristics analyzed, and an increase in recorded cases of IPVAW over the eight-year period, with a marked seasonal pattern. Our findings provide important information to enhance understanding of the nature, extent, and temporal trends of IPVAW in Spain and to better target and evaluate prevention policies. Our study highlights the importance of policies aimed at increasing the reporting of IPVAW to the police and other law enforcement agencies. By gradually closing the gap between the recorded and actual prevalence of IPVAW, a greater number of women victims of this type of violence become visible and therefore have access to protection and support measures. An increase in police-recorded IPVAW also underscores the important role of the police in combating and preventing this type of violence, reflects greater confidence in the role of law enforcement agencies, becomes an important deterrent for perpetrators, and symbolizes a growing rejection of IPVAW by society. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Gracia, E., Escobar-Hernández, P., López-Quílez, A., Marco, M., Lila, M., &, López-Ossorio, J. J. (2025). Police records of intimate partner violence against women in Spain: An eight-year analysis of demographic patterns and temporal trends. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 7(2), 59-71. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a6 Funding This study was supported by Grant Nº PID2022-137942OB-I00 from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation/State Research Agency and the European Regional Development Fund (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE), and by Grant Nº CIPROM/2021/46 from the Generalitat Valenciana/Prometeo Program. References |

Cite this article as: Gracia, E., Escobar-Hernández, P., López-Quílez, A., Marco, M., Lila, M., & López-Ossorio, J. J. (2025). Police Records of Intimate Partner Violence against Women in Spain: An Eight-year Analysis of Demographic Patterns and Temporal Trends. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 59 - 71. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a6

Correspondence: enrique.gracia@uv.es (E. Gracia).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS