PTSD Prevalence in US Prisons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

[La prevalencia del TEPT en las prisiones de EE. UU.: una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis]

Laura Young1, Alexander Trinidad2, & Maite Azabal-Gallego3

1University of Mannheim, Germany; 2University of Cologne, Germany; 3University of the Basque Country EHU, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a7

Received 23 August 2024, Accepted 29 May 2025

Abstract

Background: This study aims to update the evidence on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevalence in US prisons and jails by adopting part of the methodology from a prominent systematic review, specially paying attention to Open Science values, such as transparency and reproducibility for future research updates. Method: Assisted by ASReview, 36,052 papers from six databases were screened, followed by full-text reviews by two independent reviewers. Only studies using validated diagnostic instruments to assess PTSD in random samples of general prison or jail populations in the US between 1980 and 2023 were included. Results: Of the initial 221 studies selected for an in-depth full-text screening, ten studies, with a combined sample size of 4,016 participants, met the inclusion criteria—four more than the original review. Meta-analyses were conducted to estimate pooled prevalence rates and evaluate heterogeneity and publication bias. The point prevalence of PTSD was 16% for men and 32% for women, while lifetime prevalence was 38% for men and 45% for women. Conclusions: Despite restricting the analysis to one country and applying stringent inclusion criteria, high between-study heterogeneity persists, indicating the need for caution in interpreting and generalizing the results.

Resumen

Antecedentes: El estudio es una actualización de las pruebas sobre la prevalencia del trastorno de estrés postraumático en prisiones de EE. UU. utilizando parte de la metodología de una destacada revisión sistemática, prestando atención en especial a los valores de Open Science, como como la transparencia y la capacidad de reproducción pensando en actualizaciones futuras de la investigación. Método: Se revisaron 36,052 trabajos de seis bases de datos con ayuda de ASReview, seguido de revisiones del texto completo por parte de dos revisores independientes. Solo se incluyeron lose estudios que utilizaban instrumentos diagnósticos validados para evaluar el TEPT en muestras aleatorias de poblaciones generales penitenciarias en EE. UU. entre los años 1980 y 2023. Resultados: Solo diez estudios de los 221 elegidos inicialmente para una revisión en profundidad de todo el texto, con un tamaño muestral combinado de 4,016 participantes cumplían los criterios de inclusión (cuatro más que la revisión original). Se llevaron a cabo metaanálisis para medir los índices de prevalencia acumulados y la heterogeneidad y los sesgos de publicación. La prevalencia del TEPT era 16% en los varones y 32% en las mujeres y la prevalencia permanente era 38% en varones y 45% en mujeres. Conclusiones: A pesar de haber limitado el análisis a un país y de aplicar criterios de inclusión rigurosos persiste una elevada heterogeneidad entre estudios, lo que indica que hay que tener precaución a la hora de interpretar y generalizar los resultados.

Keywords

PTSD, Mental health effects, Research methodology/measurement, Female offendersPalabras clave

TEPT, Efectos de salud mental, MetodologĂa/mediciĂłn de la investigaciĂłn, Mujeres delincuentesCite this article as: Young, L., Trinidad, A., & Azabal-Gallego, M. (2025). PTSD Prevalence in US Prisons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 73 - 87. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a7

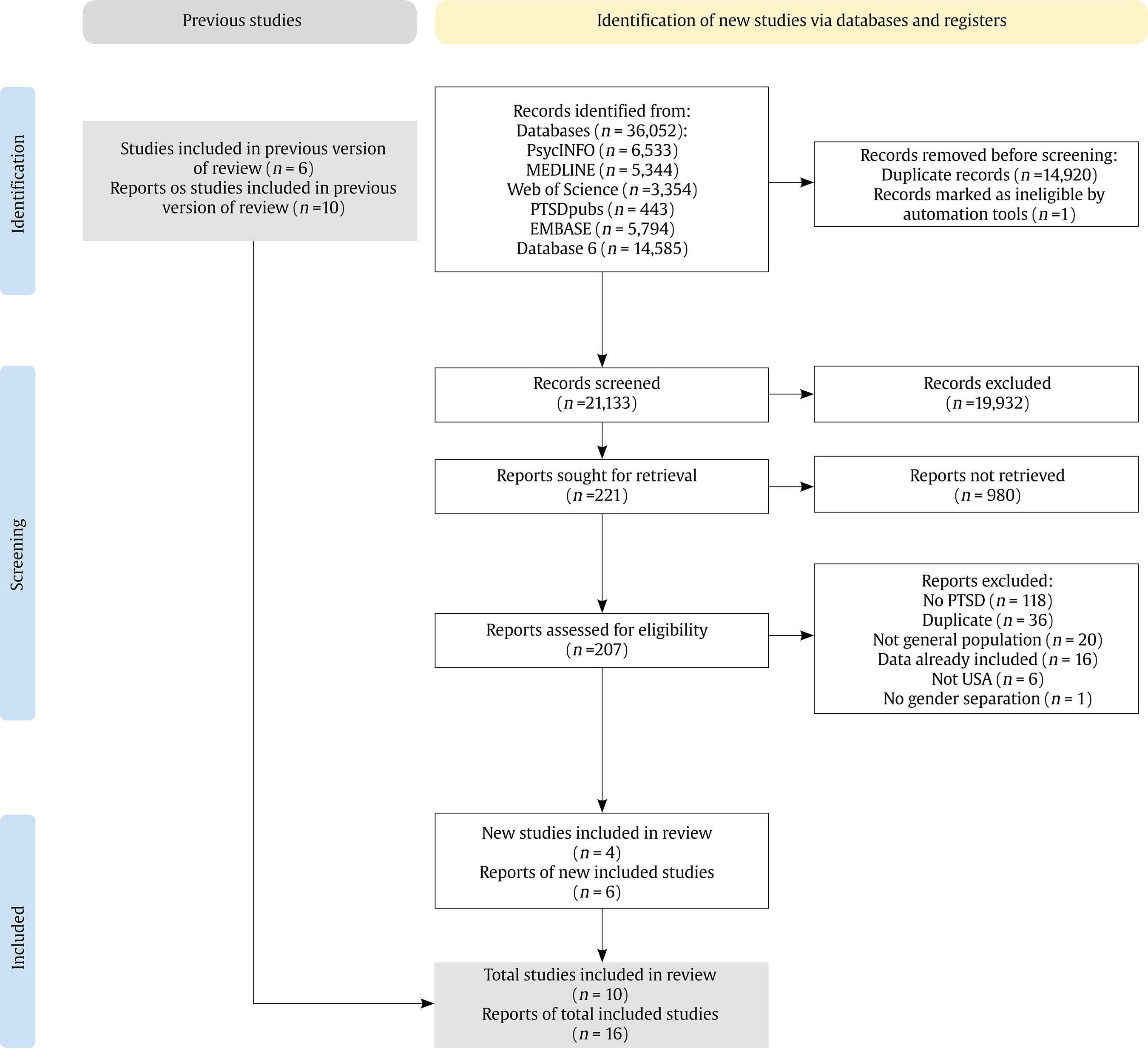

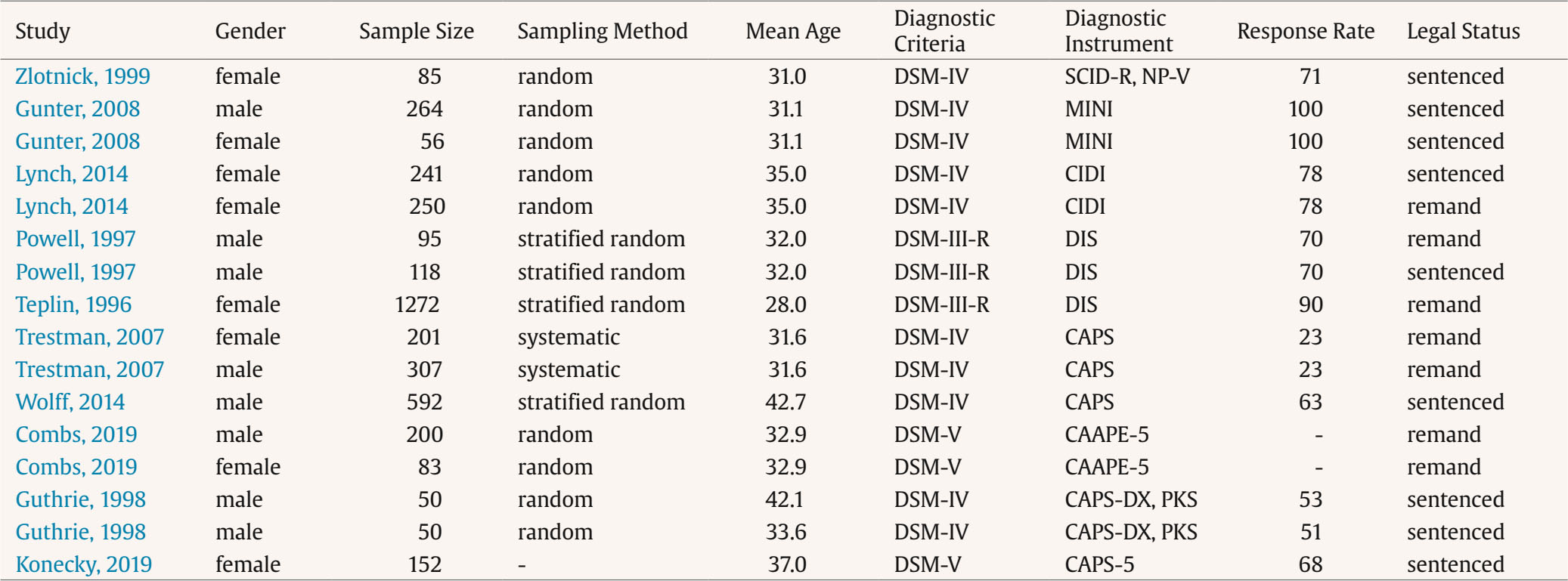

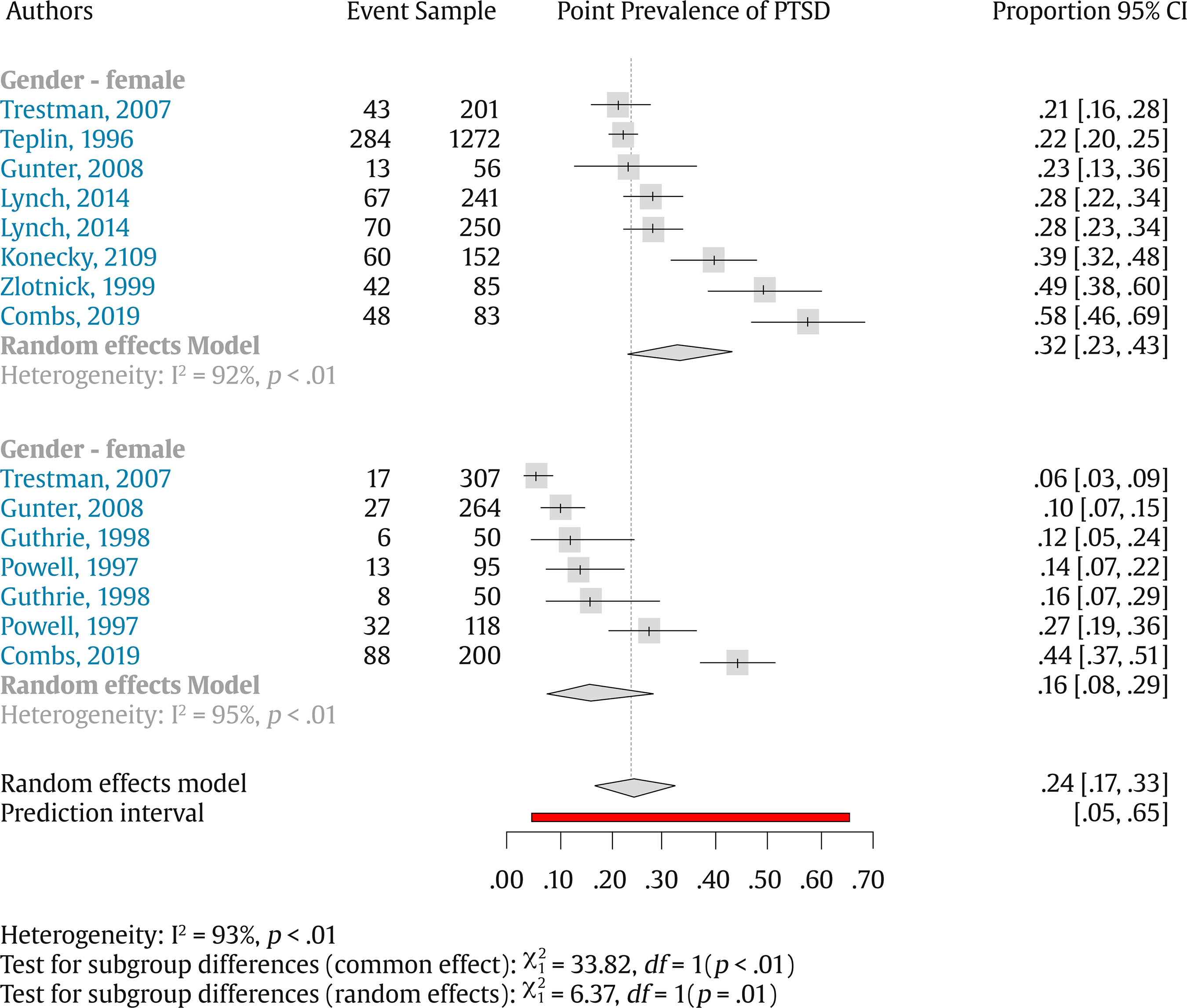

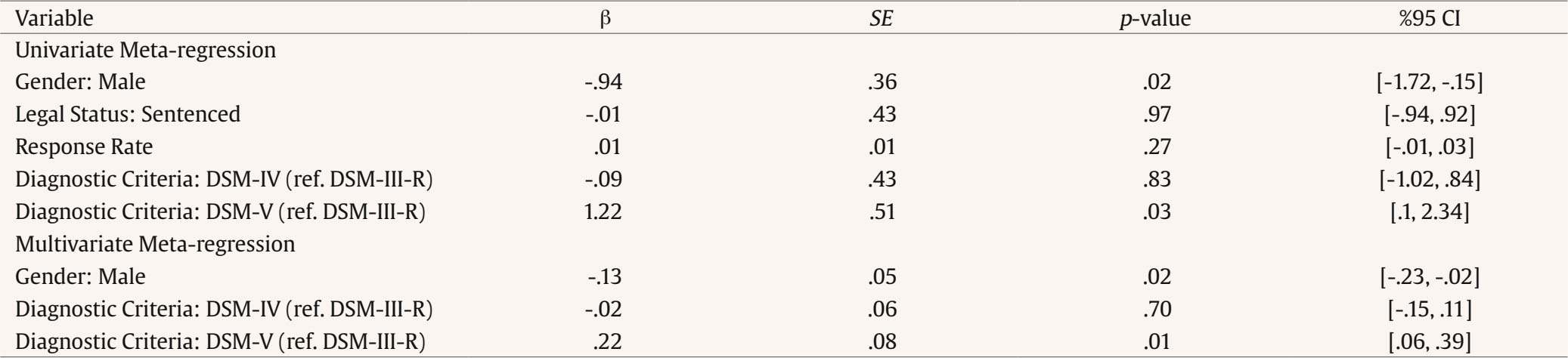

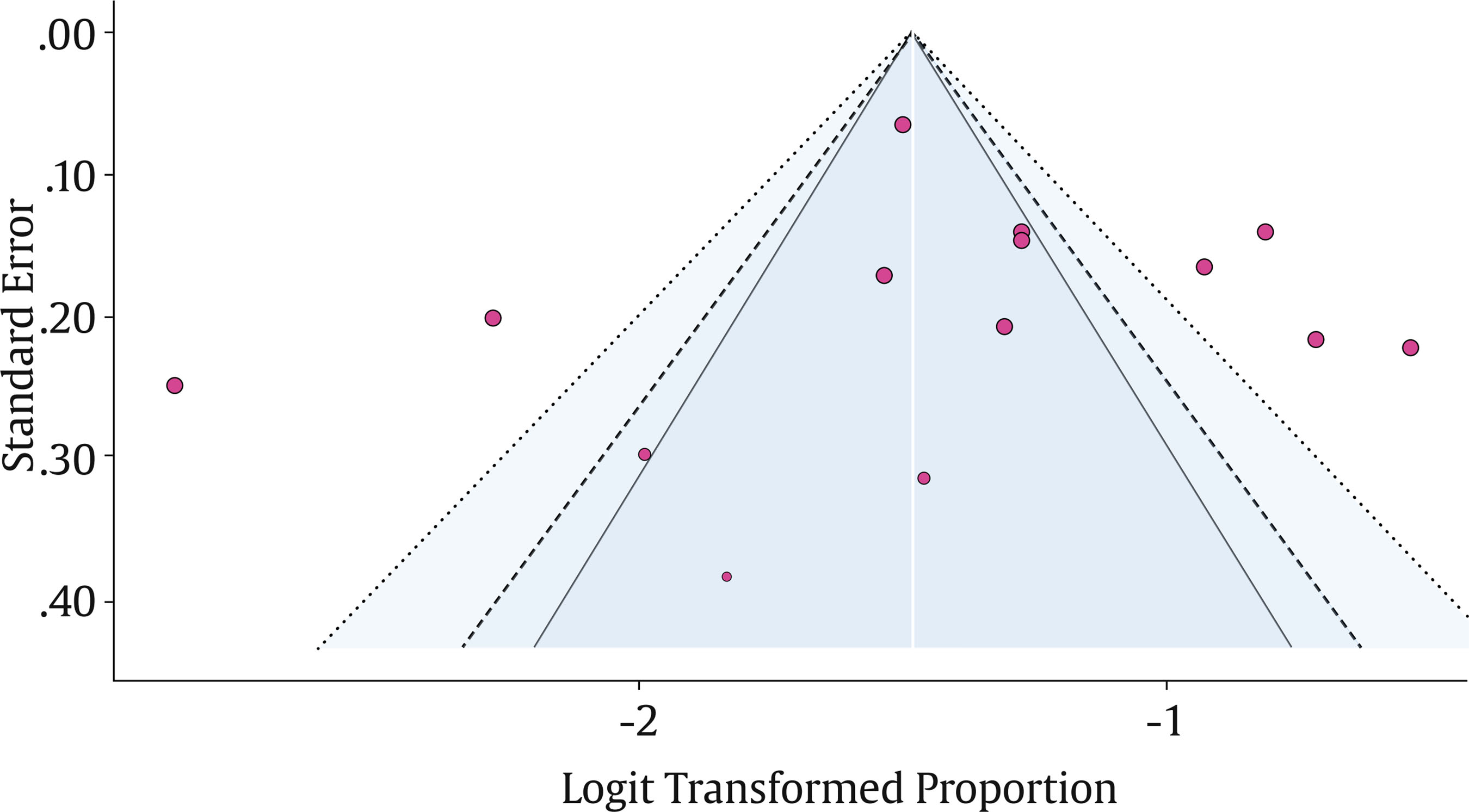

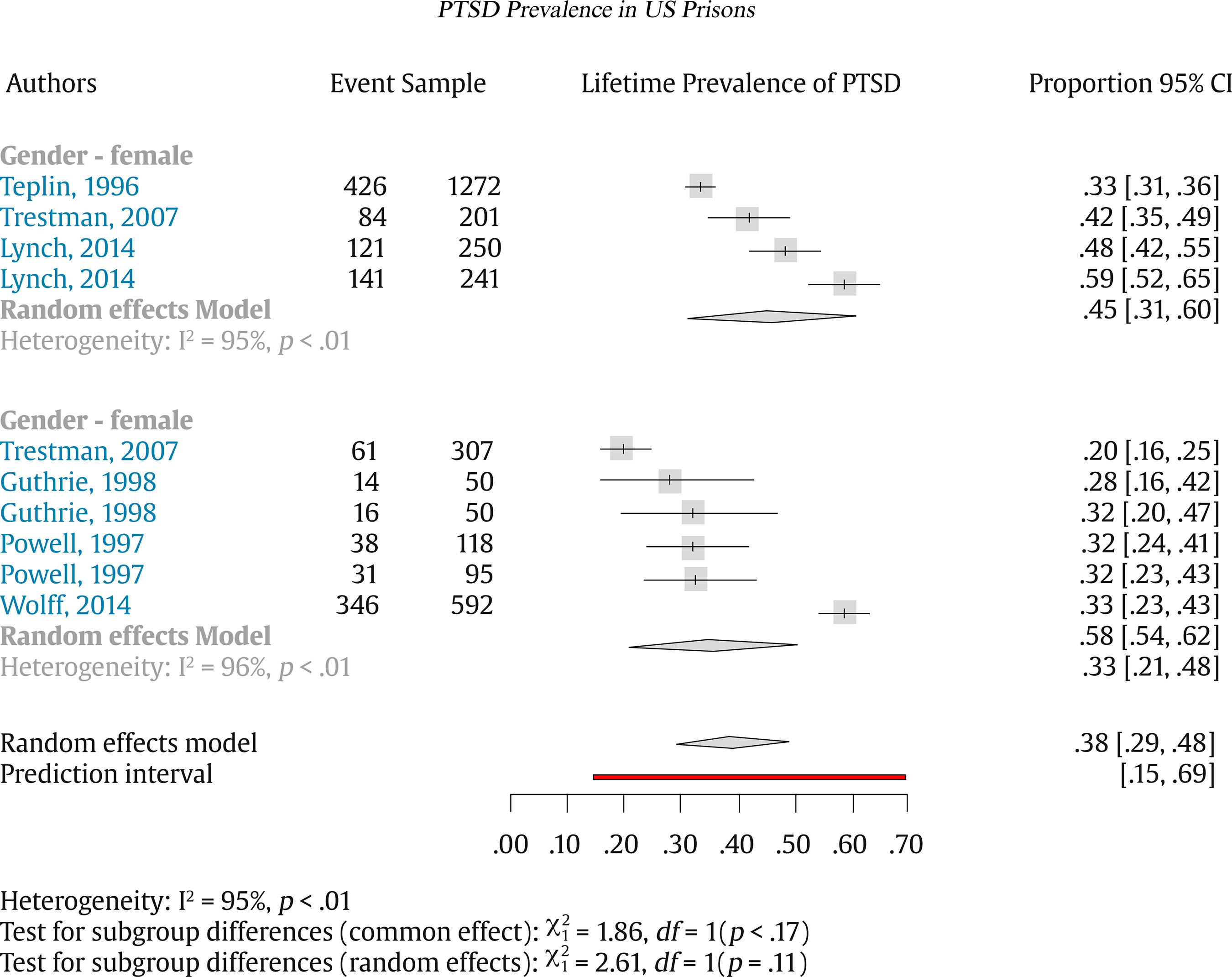

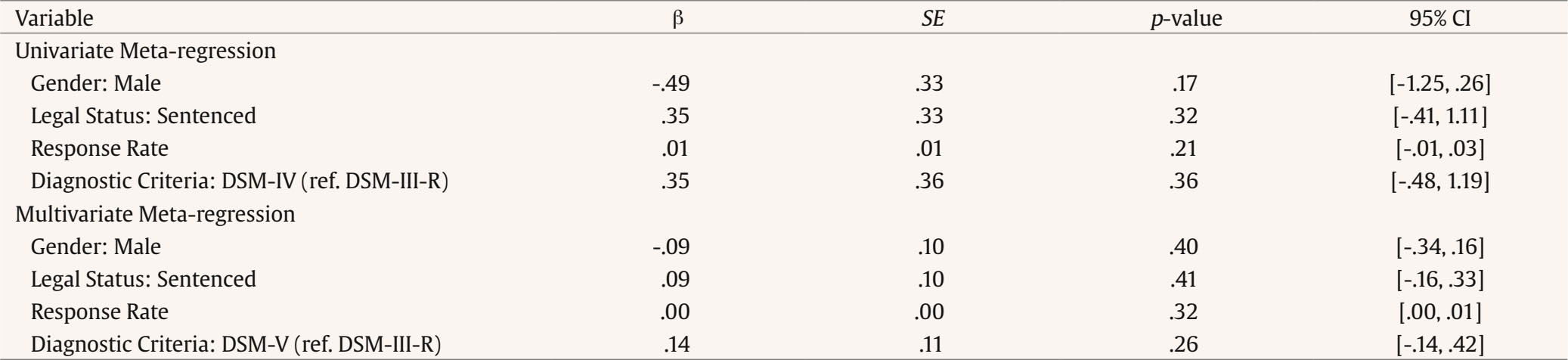

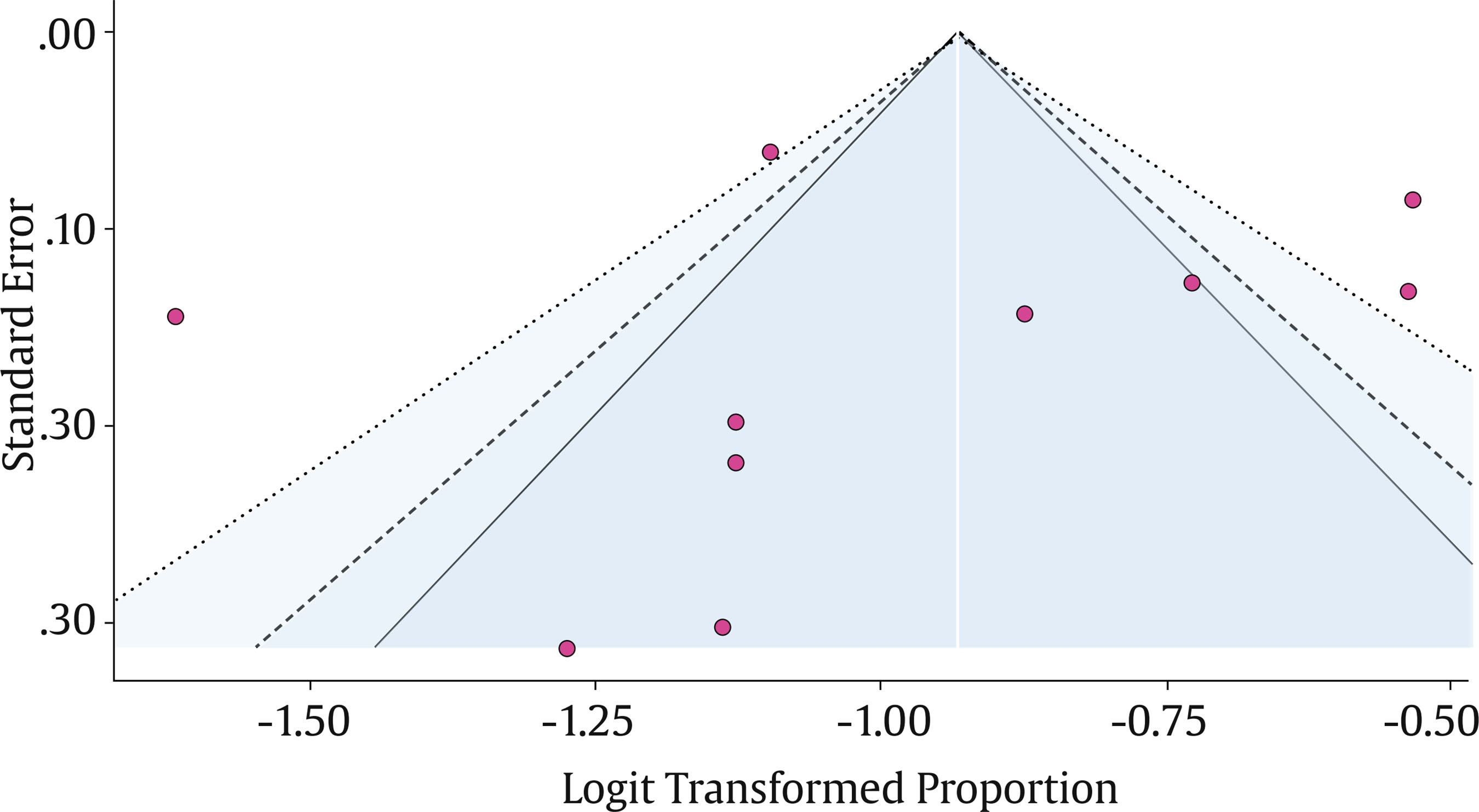

Correspondence: laura.young@uni-mannheim.de (L. Young).Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is one of many possible adverse mental health outcomes which can develop following exposure to one or many traumatic events, including periods of incarceration. These experiences may be targeted and intentional, such as victimization of interpersonal violence, but also include trauma from circumstances that are arbitrary, such as the aftermath of natural disasters. The symptoms include but are not limited to “distressing and intrusive memories and nightmares of the trauma, irritability, hypervigilance [...], difficulty sleeping, poor concentration, and emotional withdrawal” (Yehuda et al., 2015). The prevalence of PTSD is shown to be related to the severity of the event, the timing of the exposure, and the number of traumatic experiences (Lukaschek et al., 2013; Yehuda et al., 2015). It is important to note that, although the vast majority of the US population will experience a traumatic event in their lives, only a small fraction of these individuals will develop PTSD (Benjet et al., 2016). PTSD is still a very frequent occurrence in prison settings (Facer-Irwin et al., 2019). In 2023, the prevalence of PTSD in prisons is estimated at anywhere between 0.1% and 27% for male and 12% and 38% for female inmates compared to the base population level of 0.3% to 8.8% (Fovet et al., 2023). Similar patterns in gender differences are observed in non-prison populations (Olff et al., 2007). Incarceration can potentially lead to a PTSD diagnosis, though it would be misleading to attribute (lifetime) PTSD prevalence in prisons only to the exposure to imprisonment, as this neglects an individual’s prior life experiences. As an example, female inmates with PTSD are prone to have experienced sexual violence as early as childhood (Baranyi et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2008). A number of studies note that women are almost twice as likely to be diagnosed with PTSD compared to men. Some studies explain the discrepancy due to the type and timing of the trauma women experience and the likelihood that they will be revictimized (Olff et al., 2007). These studies often assume that the difference between men and women banishes, in particular when controlling for experiences with childhood abuse or sexual violence. Other papers contend that women are more at risk to develop PTSD even when controlling for past experiences (Holbrook et al., 2002; Stein et al., 2000; Voges & Romney, 2003). While there is a lot of research attempting to summarize PTSD in US prisons, many papers only examine specific strata of the population, for example only focusing on a certain offender type or age group (e.g., Beaudry et al., 2020). Others neglect to take different biases into consideration, which may skew results (Baranyi et al., 2018; Goff et al., 2007; Sirdifield et al., 2009). Baranyi et al. (2018) conducted a comprehensive systematic literature review and meta-analysis with papers sourced from 1980 to June 2017. From the highly selective process with clearly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 56 records were identified from 20 different countries, which resulted in a total sample of N = 21,099 participants. They were able to differentiate between low- or middle-income countries (LMIC) and high-income countries (HIC) and used this and other similar characteristics, such as sample gender and penal status, to perform a series of sensitivity analyses to access and reduce heterogeneity. Study quality was also assessed using an adjusted Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The pooled point prevalence was 6.2% in male and 21.1% in female subjects, while the pooled lifetime prevalence was 17.8% in male and 40.4% in female subjects, albeit with very high heterogeneity between samples. The aim of the current study is to partially replicate the work of Baranyi et al. (2018) and update the evidence on the prevalence of PTSD in prison populations in the US. This is considered a partial replication because our focus is limited to the United States. We chose to update the review with a US-only focus for several reasons which are addressed below. First, as of April 2024, the United States had the highest incarcerated population in the world (Fair & Walmsley, 2024). This is particularly relevant, as Baranyi et al. (2018) used the U.S. as a comparator group when assessing heterogeneity across studies. Second, when comparing various countries, the heterogeneity in prevalence is striking. Although PTSD is a global disorder, the way prisons in different countries deal with mental health differs markedly. Prison systems across countries—regardless of being classified as WEIRD [Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic]—differ significantly in terms of policies, legal structures, healthcare access, and incarceration conditions (Koenen et al., 2017). Even in the same country, there might be differences in jurisprudence between states that have an impact on the prevalence of PTSD in prison. State-specific laws can affect the duration and quality of incarceration, as well as the outlook on rehabilitation, which could be a mechanism for PTSD prevalence (Berger & Scheidegger, 2022; Chen, 2013). Our decision to update the current knowledge on the prevalence of PTSD in prison populations in the United States is in line with international standards and guidelines for conducting systematic reviews, which recommend an update every five years—or sooner if the topic is rapidly developing (Campbell Collaboration, 2021). In this regard, it is reasonable to assume that additional research has become available since the last search conducted in June 2017 by Baranyi et al. (2018). This is particularly relevant given the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which placed unprecedented strain on the mental health of the incarcerated population (Burton et al., 2021; Hewson et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2021). The completed methodology of this systematic review is described in the protocol, which was first uploaded to OSF.io1 on October 10th of 2023. We reported the outcomes of the synthesis following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). For this systematic literature review, the papers were first sourced from databases using a predetermined string of search terms and then deduplicated. The deduplicated data was imported into ASReview and systematically screened with the help of a screening tool. This filtering process was primarily carried out by one researcher, with an additional 10% carried out by another researcher for transparency and to address serious bias. Then, a full-text screening process was conducted with a list of inclusion/exclusion criteria. From this smaller selection of relevant papers, a secondary search was conducted via bidirectional citation searching to potentially collect a few more papers that may have been missed in the initial search. An overview of the full screening processes can be found in the PRISMA flowcharts (Haddaway et al., 2022) on the OSF. For readability, a version of the flowchart which only contains the primary database search is shown in Figure 1. The final corpus was then critically appraised and examined for quality using CASP and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The results were then pooled and statistically analyzed. Eligibility Criteria The studies were first subject to a screening tool via ASReview, and then those identified as initially relevant were further subject to a full text screening. Studies were included if:

Studies were excluded if:

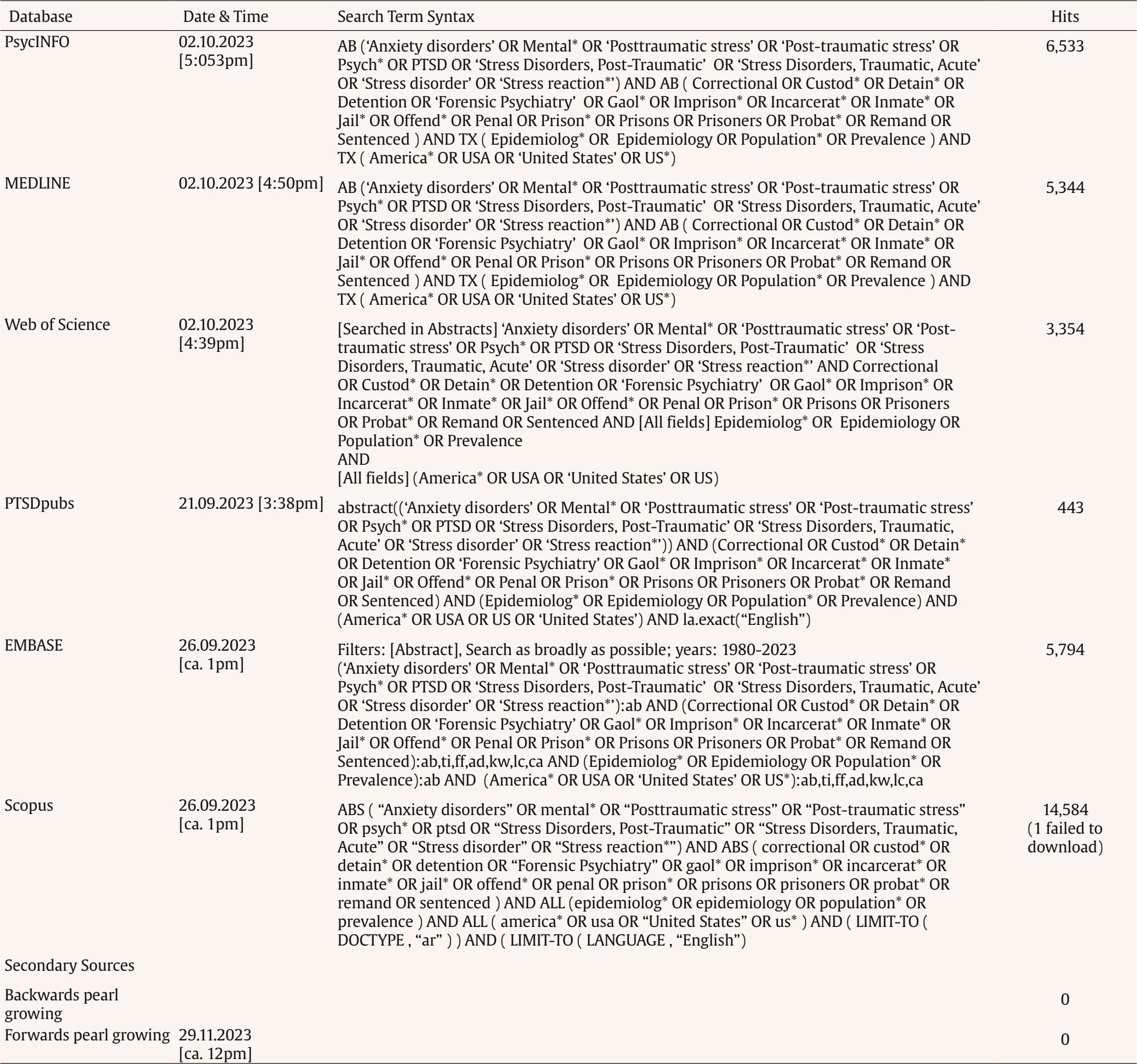

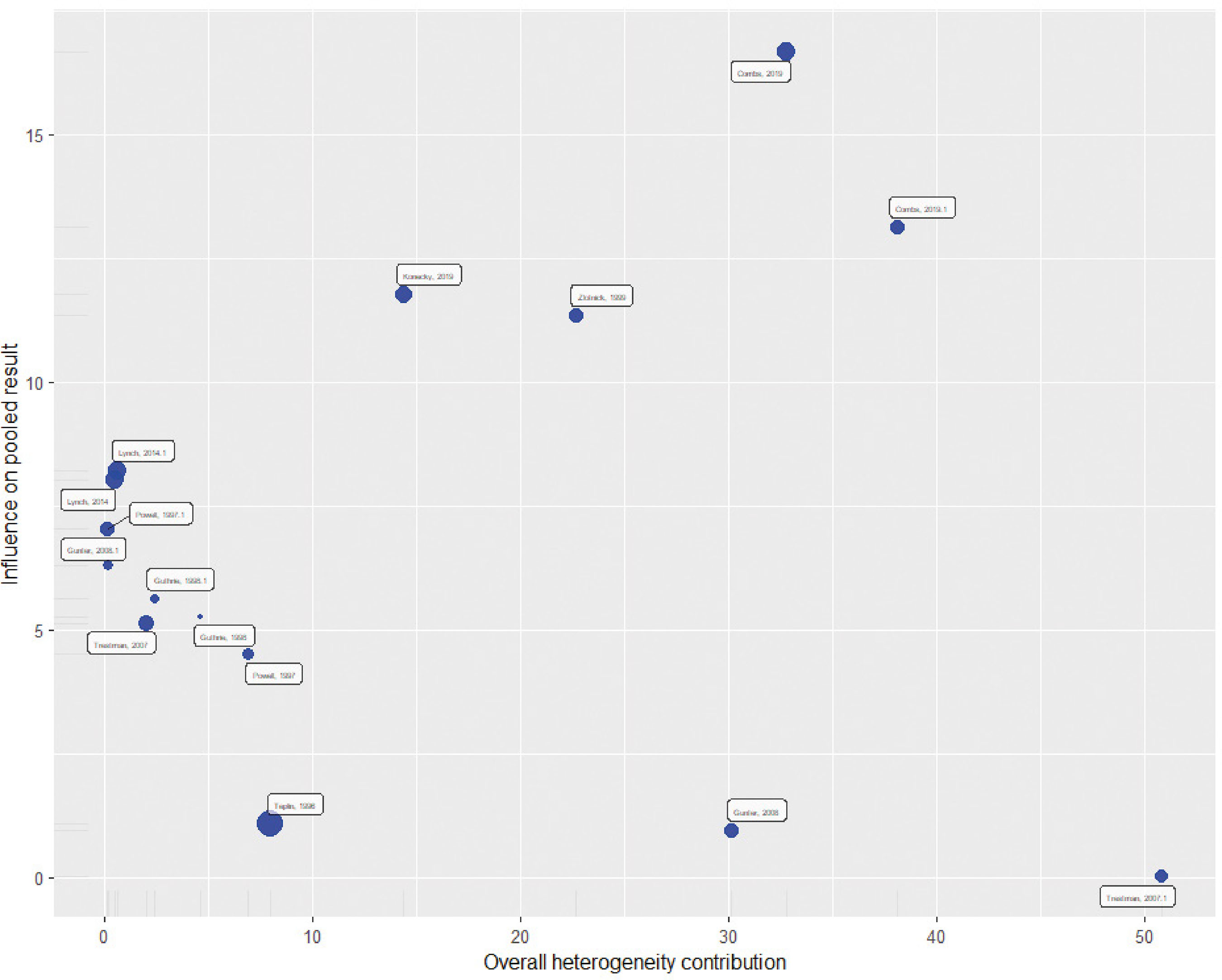

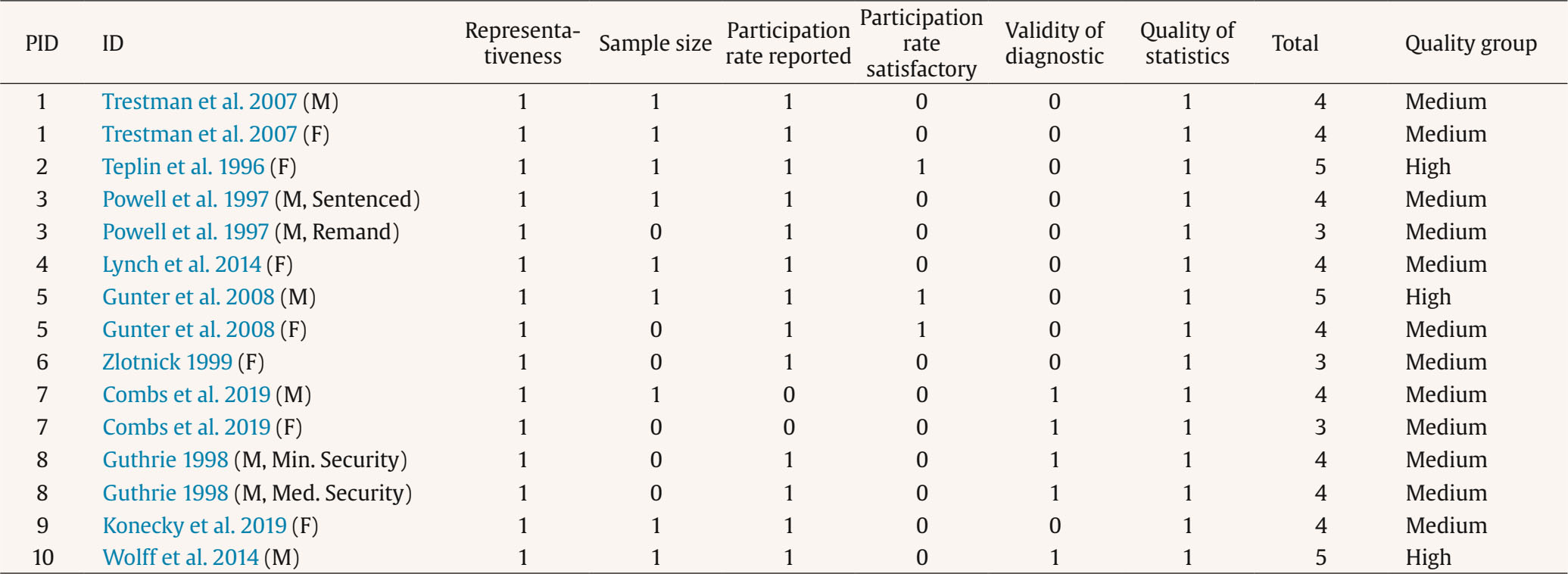

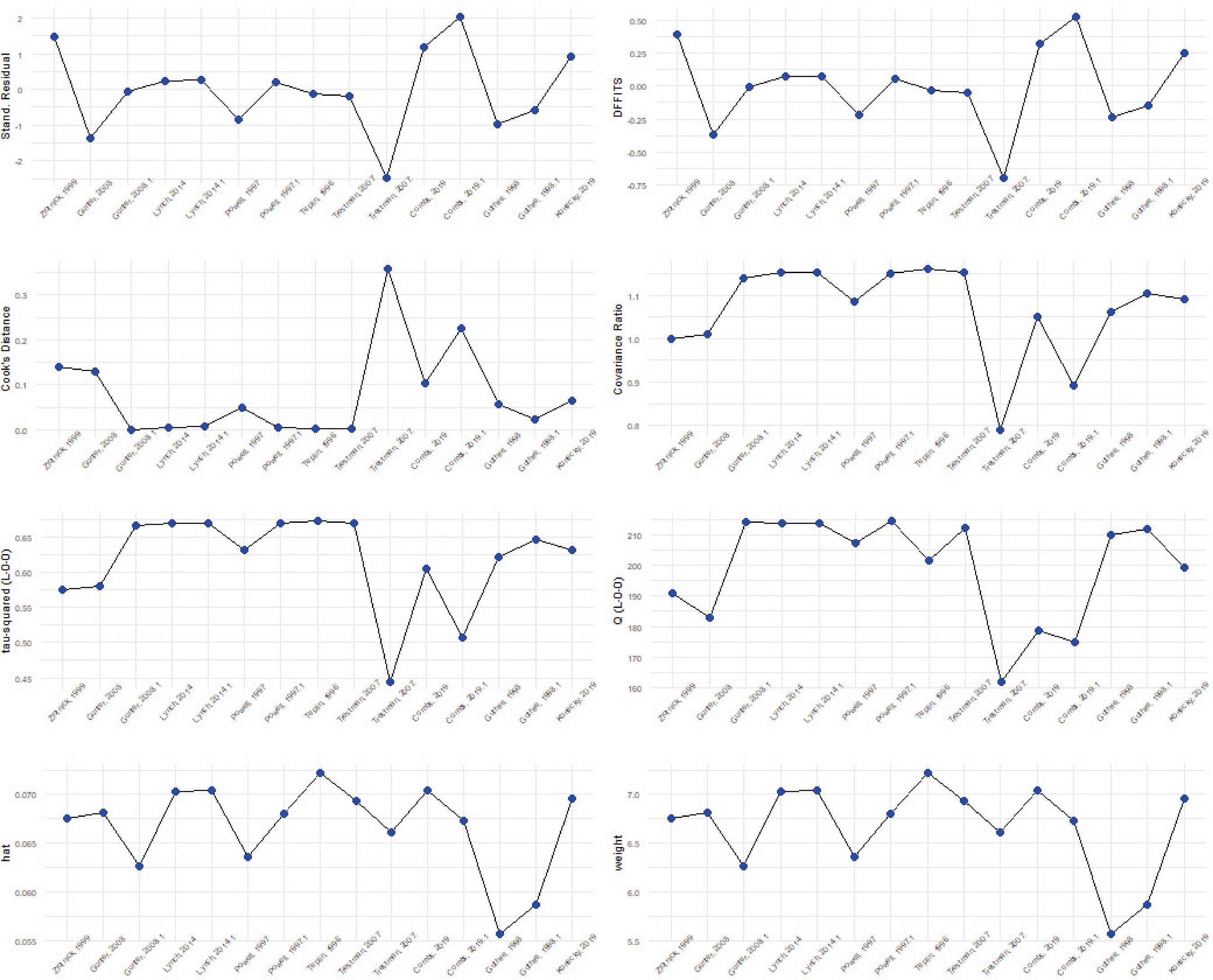

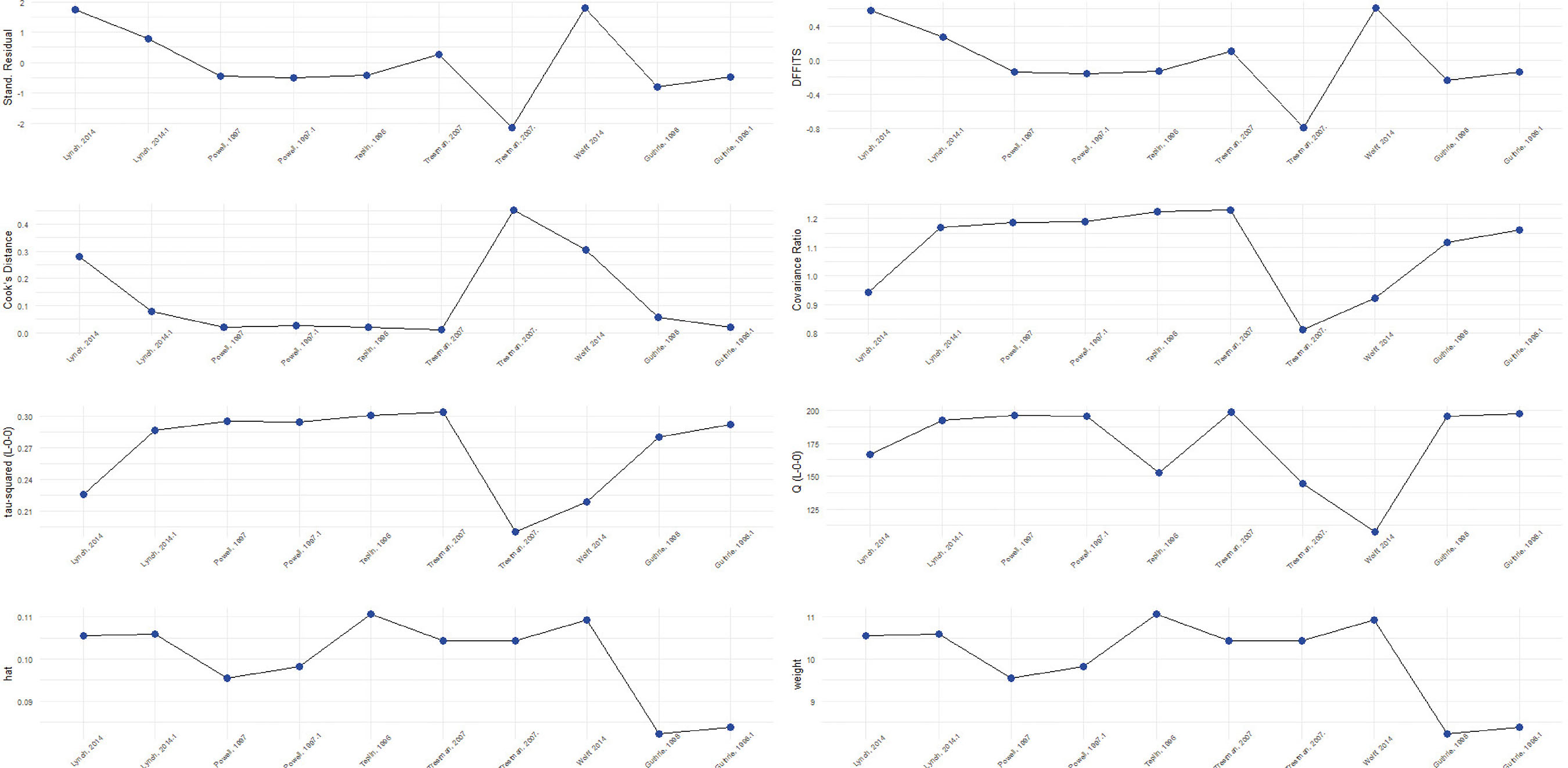

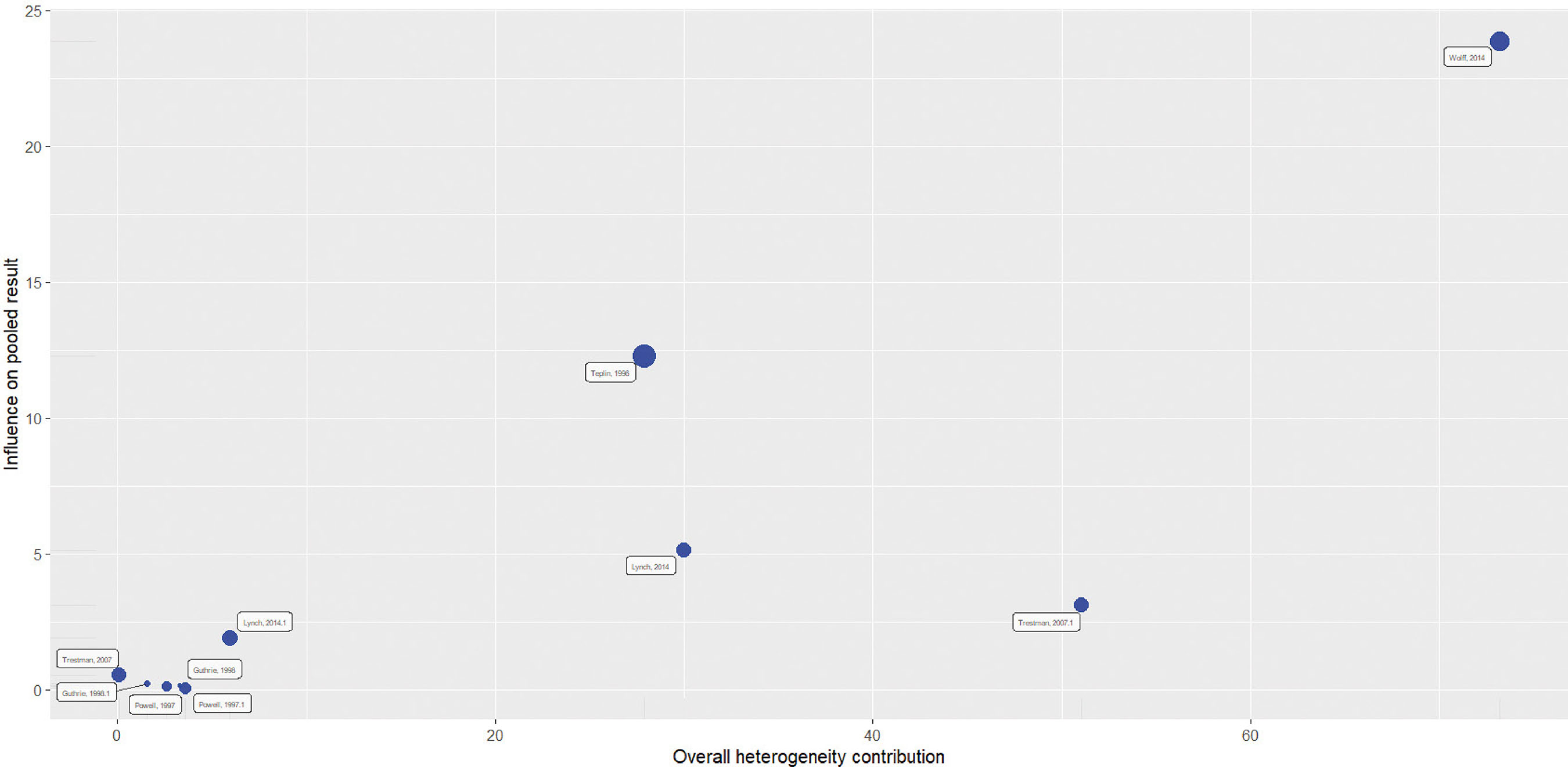

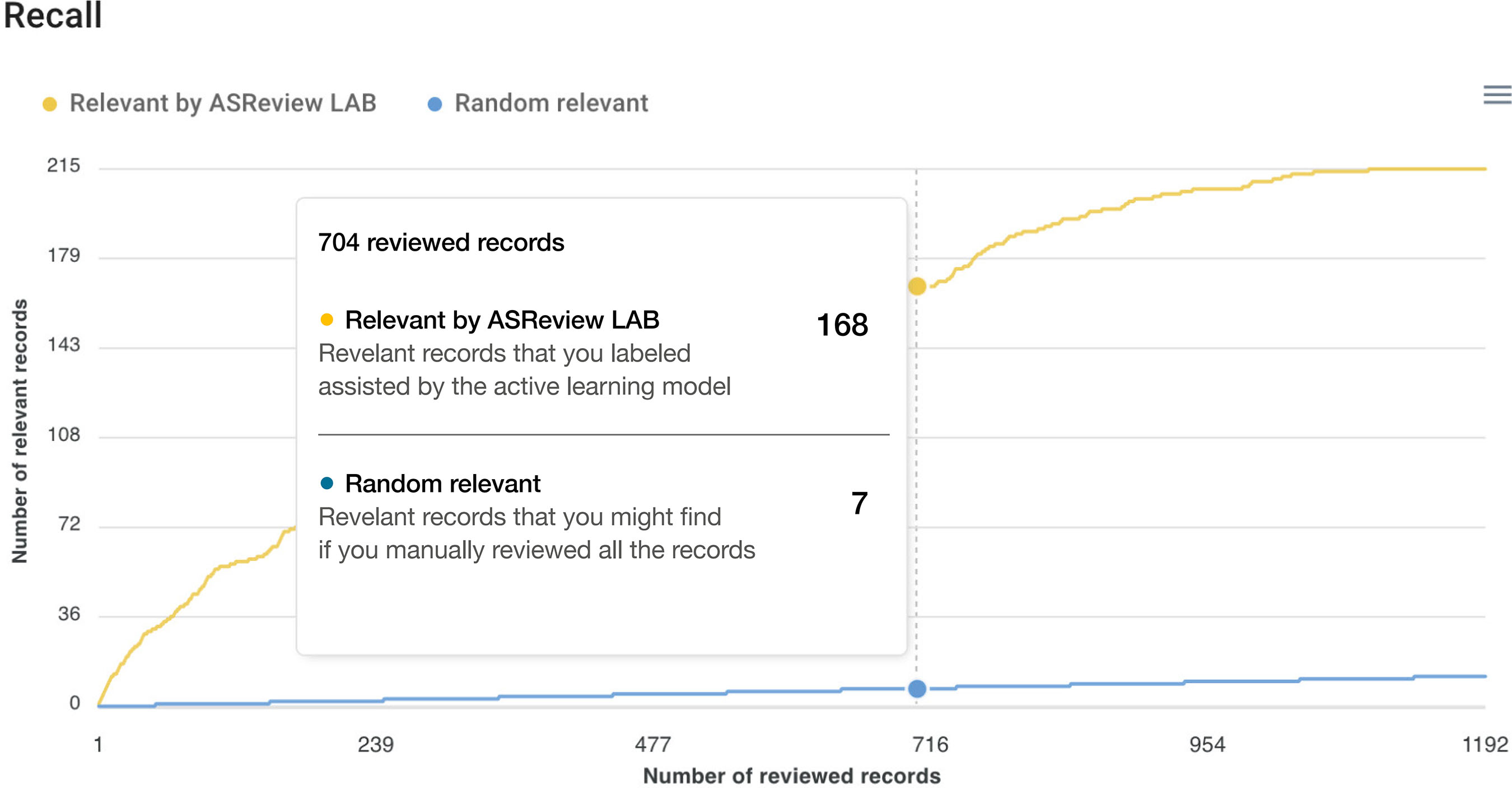

Evidence Identification The majority of the search terms were adopted from Baranyi et al. (2018, p. 135), as these free-text strings were developed in a group consensus by domain experts. We judged it appropriate to build on this established and peer-reviewed set of terms, rather than attempt to develop new terms independently. However, a number of modifications were made to the procedure to distinguish this study from a replication. For example, the scope of this study is narrower, needing additional search terms for more focused, accurate results. These terms are America, USA, US, and United States. [Search in Abstract] Anxiety disorders OR Mental* OR Posttraumatic stress OR Post-traumatic stress OR Psych* OR PTSD OR Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic OR Stress Disorders, Traumatic, Acute OR Stress disorder OR Stress reaction* Correctional OR Custod* OR Detain* OR Detention OR Forensic Psychiatry OR Gaol* OR Imprison* OR Incarcerat OR Inmate* OR Jail* OR Offend* OR Penal OR Prison* OR Prisons OR Prisoners OR Probat* OR Remand OR Sentenced Epidemiolog* OR Epidemiology OR Population* OR Prevalence OR Prevalence America* OR USA OR US OR United States The starting period of this systematic search also begins in 1980, when PTSD was introduced as a diagnostic category in the DSM-3. This search was then extended further until June 2023. Borrowing from the consensus of the original authors and our own research into the validity of the sources and, given the scope of this study, the search includes the following sources: 1) Online databases2 (i.e., Embase, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO; PTSDpubs, National Justice Reference System; Scopus; Web of Science). 2) A secondary search via backwards and forwards citation searching The initial search, conducted between 26.09.2023 and 02.10.2023, rendered N = 36,052 papers in total. A list of sources with the time and date of access, and number of papers retrieved per database is available in Table S1 in Appendix. Study Selection With the corpus of papers collected, the next step was to conduct a systematic screening in order to filter out irrelevant literature. Due to the size of the dataset and the aim for transparency, this required a number of well-documented steps. The corpus was first deduplicated, then screened using ASReview and a screening tool (see Appendix) in accordance with suggested best practice guidelines (Polanin et al., 2019). ASReview allows for scalable manual abstract screening through the integration of active learning techniques. The manual screening of titles and abstracts for relevance is augmented by a machine learning model —in this case, a naive Bayes classifier based on TF-IDF scores; this setup represents the default setup for ASReview, because it has shown to have a good performance (van de Schoot et al., 2021). Because of the predictive power of ASReview, and based on simulation studies, screening anywhere between 5% and 40% of the whole dataset is enough to filter out 95% of relevant papers (Tay, 2021). Based on protocols from other researchers (Langton et al., 2024) and on the ASReview introduction (van de Schoot et al., 2021), we opted for a data-driven approach wherein screening continues until ASReview shows 100 irrelevant studies in a row. The full dataset was screened independently by two researchers using ASReview. The first researcher screened the entire dataset in late 2023 in an ASReview project. The second researcher independently screened the same dataset in a separate ASReview project in early 2024. Although both used the same inclusion/exclusion criteria and tool (ASReview), their screenings were conducted separately and at different times, ensuring independent evaluation. Ten percent of the dataset screened by the authors was screened by a third researcher. Interrater reliability index (IRR) was estimated via Krippendorff’s alpha and, with a Krippendorff’s alpha of .75, the screening is considered satisfactory. The disagreements in screening were recorded and clarified in discussion. These are also readily available on OSF.io, as well as the R code and data used to generate the IRR. The majority of disagreements were due to a misunderstanding of the final question in the screening tool regarding what constitutes a “general population”, and were therefore quickly settled. Critical Appraisal Following the initial screening process and the full-text examination to determine the relevance of the papers, we also assessed the quality of each paper in the sample. For this, we used a version of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (Wells et al., 2000), which was modified by Baranyi et al. for application to PTSD studies. This scale dichotomizes questions of quality in terms of, e.g., how representative the sample is or whether or not the diagnostic tools are valid. Because of the dichotomy of the answers, this scale on its own can be vague. Therefore, we also assessed the studies using the CASP Checklist that is appropriate for the individual study, e.g., CASP Checklist For Diagnostics. Each study scored a medium or high in the NOS analysis and the full review can be found in the Appendix and on OSF. The CASP checklists are meant to deepen the understanding of a paper and explicitly discourage a scoring system (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018). Data Analysis Prevalence rates were recorded for male and female samples separately and, where possible, for differing legal statuses. Because the comparison takes place across many years and in different states of the US, one cannot assume a single, homogenous population in spite of efforts to restrict the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) (Higgins et al., 2023) framework suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews. Therefore, the effect sizes were pooled using a mixed-effects model with the Meta R package (version 6.5-0), rather than a fixed effects model (Harrer et al., 2021). First, the effect sizes (prevalence rates) were logit-transformed and then fed into a generalized linear mixed-effects model (GLMM), which can account for the heterogeneity between studies when estimating the pooled prevalence. Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals were calculated for the individual studies. Even with the steps taken to account for heterogeneity, it is unsure to what extent the (true) effect sizes vary between studies. Between-study heterogeneity was addressed based on Higgins & Thompson’s (2002) I² statistic, which is directly based on Cochran’s Q and “describes the proportion of total variation in study estimates that is due to heterogeneity”. As a rule of thumb, I² > 75% is considered to be an indication of high heterogeneity. To further investigate the heterogeneity patterns we performed a series of meta-regressions. For the multiple meta-regression, we used the maximum likelihood method rather than the restricted maximum likelihood, as this is recommended for comparison between meta-regression models (Harrer et al., 2021). To test the regression coefficients, we chose the Knapp-Hartung method. In addition, an influence analysis was performed using dmetar R package (version 0.1.0) to identify outliers and a sensitivity analysis examines how the pooled prevalence estimates would look without them. This was supplemented with a Baujat plot, which visualizes the studies’ contributions to heterogeneity, measured with Cochran’s Q. Publication bias was addressed with funnel plots of the prevalence estimates against their standard errors (Baranyi et al., 2018; Sterne & Harbord, 2004). All statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.2.1. The code and data for these analyses are also available on OSF.io. From the initial 36,052 articles drawn from the databases, 10 total studies with 16 separate samples were seen as relevant (see Table 1). These are as follows: Trestman et al. (2007), Teplin et al. (1996), Powell et al. (1997), Lynch et al. (2014), Gunter et al. (2008), Zlotnick (1999), Combs (2019), Guthrie (1998)3, Konecky and Lynch (2019), and Wolff et al. (2014). While the first screening could not identify more papers than Baranyi et al., the second screening resulted in four additional papers Combs (2019), Guthrie (1998), Konecky et al. (2019), and Wolff et al. (2014). As a result, this systematic review captures a total of 4,016 participants who fit the inclusion criteria of US-located adults drawn from a general prison population; 58.3% of the sample (n = 2,340) is female and 41.2% (n = 1,676) is comprised of male subjects. There were large differences in sample size between studies, as the largest sample had a size of n = 1,272 female participants, and the smallest a sample of n = 50 male participants. The overall mean age of the participants across studies was 32.4 years, with the reported mean age ranging from 28 to 42.7 between the studies. Geographically, the samples were collected from Connecticut, Maryland, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Colorado, North Carolina, South Carolina, Idaho, Washington DC, Iowa, and Rhode Island. One study described its data collection site as a “rural northeastern state” and another described its data collection site as “a northwestern state”. The data collection years were reported or otherwise obtained by the author for over half of the studies (Combs, 2019; Guthrie, 1998; Lynch et al., 2014; Teplin et al., 1996; Trestman et al., 2007; Wolff et al., 2014). These studies were published anywhere between 1 and 3 years after data collection. The studies differed in response rate, although most had a response rate upwards of 70%. Trestman et al. (2007) represent a major outlier in this regard with a response rate of 23%, likely due to the systematic sampling method. When contacted, Combs et al. (2019) expressed that they did not collect the information needed to calculate the response rate. Most papers (Gunter et al., 2008; Guthrie, 1998; Lynch et al., 2014; Trestman et al., 2007; Wolff et al., 2014; Zlotnick, 1999) utilized the DSM-IV as diagnostic criteria, with the remaining studies relying instead on DSM-III-R (Powell et al., 1997; Teplin et al., 1996) and DSM-V (Combs, 2019; Konecky & Lynch, 2019). The exact diagnostic instruments (e.g., questionnaire) were slightly different in almost every study: CAPS (Konecky et al, 2019; Trestman et al., 2007; Wolff et al., 2014), DIS (Powell et al., 1997; Teplin et al., 1996), CIDI (Lynch et al., 2014), MINI (Gunter et al., 2008), SCID-R (Zlotnick, 1999), and CAAPE-5 (Combs, 2019). Point Prevalence of PTSD Point Prevalence Meta-Analysis Fifteen records provide insight into the point prevalence of PTSD, sourced from ten studies (Combs, 2019; Gunter et al., 2008; Guthrie; 1998; Konecky et al., 2019; Lynch et al., 2014; Olff et al., 2014; Powell et al., 1997; Teplin et al., 1996; Trestman et al., 2007; Zlotnick, 1999) with a total of N = 3,424 participants. Two studies (Combs, 2019; Lynch et al., 2014) provide insights into the period prevalence of PTSD, which is defined as the experience of PTSD symptoms within the last twelve months. To avoid losing valuable data, we decided to widen the scope of point prevalence in this study to also encompass period prevalence. Point prevalence rates ranged from 5.6% to 57.8%. For the female sample, the pooled point prevalence is .32 (95% CI [.23, .43]). The male sample shows significantly lower prevalence with 0.16 (95% CI [.08, .29]). In other words, the pooled point prevalence of PTSD in US prisons in the selected studies is 32% for women and 16% for men, respectively. Irrespective of the subjects’ gender, the pooled point prevalence is 24% (95% CI [.17, .33]). Heterogeneity can already be gleaned from these high confidence intervals, but an I² of 93% (p < .01) confirms that the between-study heterogeneity is very high. I² is still remarkably high when separating the samples by gender, with the male sample at I² = 95% (p < .01) and the female sample slightly lower at I² = 92% (p < .01). This is also visibly apparent in the forest plot in Figure 2, in which the samples from Zlotnick (1999) and Combs (2019) show a prevalence that is twice as high as the other studies. An influence analysis visualized in a Baujat plot (Figure S1, see Appendix) also shows that both Zlotnick (1999) and Combs (2019) had a moderate contribution to the overall result. The male sample from Trestman et al. (2007) also contributed to the overall heterogeneity, albeit with far less influence on the pooled result. How exactly each study influences what metrics can be examined in Figure S2 (Appendix). A sensitivity analysis which removes outliers (Combs, 2019; Gunter, 2008; Trestmann, 2007; Zlotnick, 1999) was conducted on the remaining nine samples with n = 2,820 participants. The pooled point prevalence for PTSD in this model is .23 (95% CI [.17, .31]) with an I² = 80.6% [62.5%, 89.9%]. While it represents a big improvement, this would still generally be considered high heterogeneity (> 75%). Point Prevalence Meta-Regression We run a series of univariate and multivariate meta-regressions (Table 2) gives further insight into possible reasons for the heterogeneity. Although this step deviates from our initial protocol we see relevant to assess the studies’ prevalence variability. We considered the gender of the sample, the legal status, and the response rate, and the diagnosis criteria followed (i.e., DSM version), as they are theoretically relevant. In line with the literature outlined in the State of the Art section, the estimates for male participants are lower than the base prevalence for females by .94 (SE = .36, p = .023, 95% CI [-1.72, -.15]). The effect size can be calculated by subtracting the intercept, which represents the pooled effect of the comparison group (female participants), from the regression coefficient representing the male participants4. In other words, the estimated prevalence among males is 16.7% lower than that among females (prevalence = -.73, .94). However, adding gender as a predictor does not significantly reduce the variation between studies (I² = 93.36%). The legal status of participants—whether they were sentenced or on remand—also does not account for this variation (I² = 95.25%, b1 = -.014, SE = .43, p = .97, 95% CI [-.94, .92]). Similarly, differences in response rates between studies do not help explain the heterogeneity (I² = 95.01%, b1 = -.007, SE = .009, p = .43, 95% CI [-.01, .02]). On the other hand, the diagnostic criteria used in the studies do explain some of the variability. Specifically, when studies used DSM-5 criteria, the estimated prevalence was significantly higher (I² = 90.26%, b1 = 1.22, SE = .51, p = .04, 95% CI [0.10, 2.34]). Next, we conducted multiple meta-regressions, including the predictors that had been analyzed previously. The results show that gender and the diagnostic criteria remained statistically significant (see Table 3). We compared two multiple meta-regressions (including only gender and diagnostic criteria vs. a full model including all predictors). The likelihood ratio test did not suggest a better fit of the full model (= 0.89, p = .641), based on this and the parsimony criteria we prefer the reduced model. Our reduced multiple meta-regression (gender and diagnostic criteria) explains a significant portion of the heterogeneity, 77.42% to be precise. Point Prevalence Publication Bias Finally, in order to address publication bias, the standard errors of the studies were plotted against their respective logit-transformed effect sizes in a funnel plot (Figure 3). In generating the plot, we discovered that the studies deviate quite a bit from the funnel shape, with a number of the studies aligning on the y-axis at the same height. This could be due to homogenous or inaccurate standard errors, but we cannot exclude publication bias as a cause for the unusual pattern. Lifetime Prevalence of PTSD Lifetime Prevalence Meta-Analysis Ten records provide insight into the lifetime prevalence of PTSD, sourced from six studies (Guthrie, 1998; Lynch et al., 2014; Powell et al., 1997; Teplin et al., 1996; Trestman et al., 2007; Wolff et al., 2014) with a total of N = 3,176 participants. For the female sample, the pooled lifetime prevalence is quite high with 0.45 (95% CI [0.31, 0.60]). The male sample shows lower prevalence with 0.33 (95% CI [0.21, 0.48]). The overall pooled lifetime prevalence is 0.38 (95% [CI 0.29, 0.48]) . Heterogeneity is again measured with an I² of 95% (p < .01), signifying again that the between-study heterogeneity is very high. I² is still remarkably high when separating the samples by gender, with the female sample at I² = 95% (p < .01) and, similarly for the male sample I² = 96%, p < .01). Compared to the point prevalence estimates, which showed clusters of similar values with few outliers, the lifetime prevalence values are more dispersed in the forest plot in Figure 4. An influence analysis and Baujat plot (see Figures S3 and S4 in Appendix, as well as deposited in the OSF) indicate that Lynch (2014), Trestman et al. (2007), and Wolff (2014) can be considered statistical outliers, contributing both to the pooled result and the overall heterogeneity. A sensitivity analysis removing both of these studies leaves five studies with n = 1,585 observations and a pooled lifetime PTSD prevalence of .33 (95% CI [.30, .66]) and an improved I² = 0% (95% CI [0.0%, 79.2%]). Lifetime Prevalence Meta-Regression As with point prevalence, we performed a series of multi-regressions (univariate and multiple) (see Table 3) was also conducted to examine the lifetime prevalence heterogeneity. The results of the univariate meta-regressions showed that none of the predictors explain away part of the heterogeneity (see Table 3). Next, we conducted a multiple meta-regression. We did not observe that any of the predictors explain part of the heterogeneity (F = 2.06, p = .223). Lifetime Prevalence Publication Bias Publication bias is addressed once more with a funnel plot in Figure 5. For the lifetime prevalence values, the funnel plot is much more asymmetrical than it is for the point prevalence values. However, these results must be interpreted with caution, as publication bias is not the only probable cause for these results. It is also reasonable to assume that the asymmetry is a result of the high between-study heterogeneity. This is particularly plausible, given that the lifetime prevalence results stem from many of the same studies (Powell et al., 1997; Teplin et al., 1996; Trestman et al., 2007) as the point prevalence results, despite the contradicting plot. This systematic review on the prevalence of PTSD in US prison populations draws from ten unique studies. This study builds upon the valuable contribution of Baranyi et al. (2018) by extending their research on PTSD to focus specifically on the United States prison population. It is a partial replication and update that seeks to achieve high levels of reproducibility and replicability, i.e., with all decisions, code, and data clearly documented and shared on a sustainable open-source platform. The data was pooled and quantitatively tested for various sources of heterogeneity, and the quality of the studies was assessed both qualitatively with CASP and quantitatively in the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. This revealed that, while there were only a few studies to refer to, they were all of at least medium quality. Although it was originally planned to record point prevalence, 12-month prevalence, and lifetime prevalence, only the point- and lifetime prevalences were given in the majority of the studies. Only two studies (Combs, 2019; Lynch et al. 2014) provided 12-month prevalence, which is insufficient for a comparison as a unique category and these were therefore grouped with point prevalence. As expected, the point prevalence and lifetime prevalence rates recorded were quite high, in particular when compared to literature on non-incarcerated population PTSD prevalence; the lifetime prevalence is said to be approximately 6.9% in the general US population (Koenen et al., 2017), whereas prison populations in this study had a pooled lifetime prevalence of 38%. Contrary to some previous studies (Fazel & Danesh, 2002; Goff et al., 2007), but in line with the findings of Baranyi et al. (2018), female inmates are disproportionately affected by both point- and lifetime PTSD. When pooled, point prevalence in male inmates is around 16% and 32% in female inmates. For lifetime prevalence, this increases to 33% in male inmates, and to 45% in female inmates, albeit at the expense of a higher measure of heterogeneity. Despite limiting the study to only one country and applying a rather restrictive set of inclusion/exclusion criteria, between-study heterogeneity continues to be quite high, which indicates that caution is necessary when interpreting and extrapolating the results. This study is not without limitations. One important drawback is the deviation from the data sources first recorded in the protocol. Initially, another database and additional journals were meant to supplement the primary database search and the bidirectional citation searching. Due to access issues, however, these were omitted. In addition, multiple papers were not accessible with the three aforementioned VPNs, and, while unlikely, one cannot rule out that relevant papers may have been lost as a result. Another potential pitfall was the data-driven stopping point selected to end the ASReview screening process; the 100 irrelevant papers mark was arbitrary in nature and it is not clear whether a different approach might have rendered more/better results. Ultimately, only 5% of the records were screened, which puts a lot of (blind) faith in the algorithm, particularly when other sources cited that they needed to screen up to 40% to obtain all relevant records with a 95% certainty (Tay, 2021). It should be noted, however, that the last paper that was relevant was ordered by ASReview as 165th in the relevant records. According to the recall graph (see Figure S5 in the Appendix), the final “truly relevant” study was found in the first ca. 700 reviewed records (out of over 1,000), which could cautiously be interpreted in favor of the early stopping point. Not all limitations were a product of the scope of the review and instead stem from simple human error. The initial backwards citation search was not as transparent as the other screening processes, as it relied only on the judgment of a single researcher and, unlike the other screenings, the reasons for the majority of the exclusions were not formally recorded. This runs counter to the overall aim of the systematic review, namely the justification of each step to reduce bias or, at the very least, be transparent. Finally, while we identified only four additional studies beyond those reported by Baranyi et al. (2018), this is notable given that these were found within just six additional years. Compared to the six U.S. studies identified over a 37-year period in their review, this suggests a considerable relative increase in research on this topic. Outlook Despite these limitations, this study provides a solid foundation for future replications and it clearly reveals that there is still a need for high quality, focused research on PTSD in the United States, particularly in prison settings. The most recent primary research in this review was published in 2019 with the data collected between 2015 and 2016. This leaves an almost ten year gap between the last data collection and the time of writing. Major stressors such as the COVID-19 pandemic are unreflected in these numbers and, while recent years have shown a slight decline in incarceration rates in the US, it still has an immense inmate population in need of recognition and dedicated research. In conclusion, the high prevalence of PTSD among incarcerated populations—especially among women—reinforces the critical need for routine, comprehensive mental health screening within the US prison system. This review underscores the practical importance of investing in prison-based mental health services, including targeted treatment programs, enhanced staff training, and sustained funding for research. By prioritizing transparency and replicability in its methodology, this study offers a foundation for future work that can build systematically on shared decisions, data, and code. Importantly, the review also identifies a significant gap in the literature concerning the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on trauma exposure and PTSD risk among inmates. Addressing this gap through further research holds practical value for informing evidence-based mental health policies and interventions in prison settings. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the reviewers for their insightful comments and constructive feedback. Notes 2 Global Health was also used by Baranyi et al.(2018), however we have omitted this source due to a lack of access. 3 Guthrie (1998) reported on two distinct male populations, which had differing sample sizes and PTSD prevalence rates. One sample was sourced from a minimum security prison, while the other was from a medium security prison. 4 For more information, please see Chapter 8 in Doing MetaAnalysis in R by Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A., & Ebert, D. D. (2021). Cite this article as: Young, L., Trinidad, A., & Azabal-Gallego, M. (2025). PTSD Prevalence in US prisons: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 7(2), 73-87. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a7 References |

Cite this article as: Young, L., Trinidad, A., & Azabal-Gallego, M. (2025). PTSD Prevalence in US Prisons: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 73 - 87. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a7

Correspondence: laura.young@uni-mannheim.de (L. Young).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS