Attitudes Towards Suicide: A Systematic Review of Evaluation Instruments in Different Settings

[Actitudes hacia el suicidio: una revisión sistemática de instrumentos de evaluación en diferentes contextos]

Maria Diaz1, David Pina2, Adriana Díez-Gómez2, Andrea Cascales-Martínez1, Reyes López López1, & Esteban Puente-López3

1University of Murcia, Spain; 2University of La Rioja, Spain; 3University of Valladolid, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a8

Received 27 November 2024, Accepted 30 May 2025

Abstract

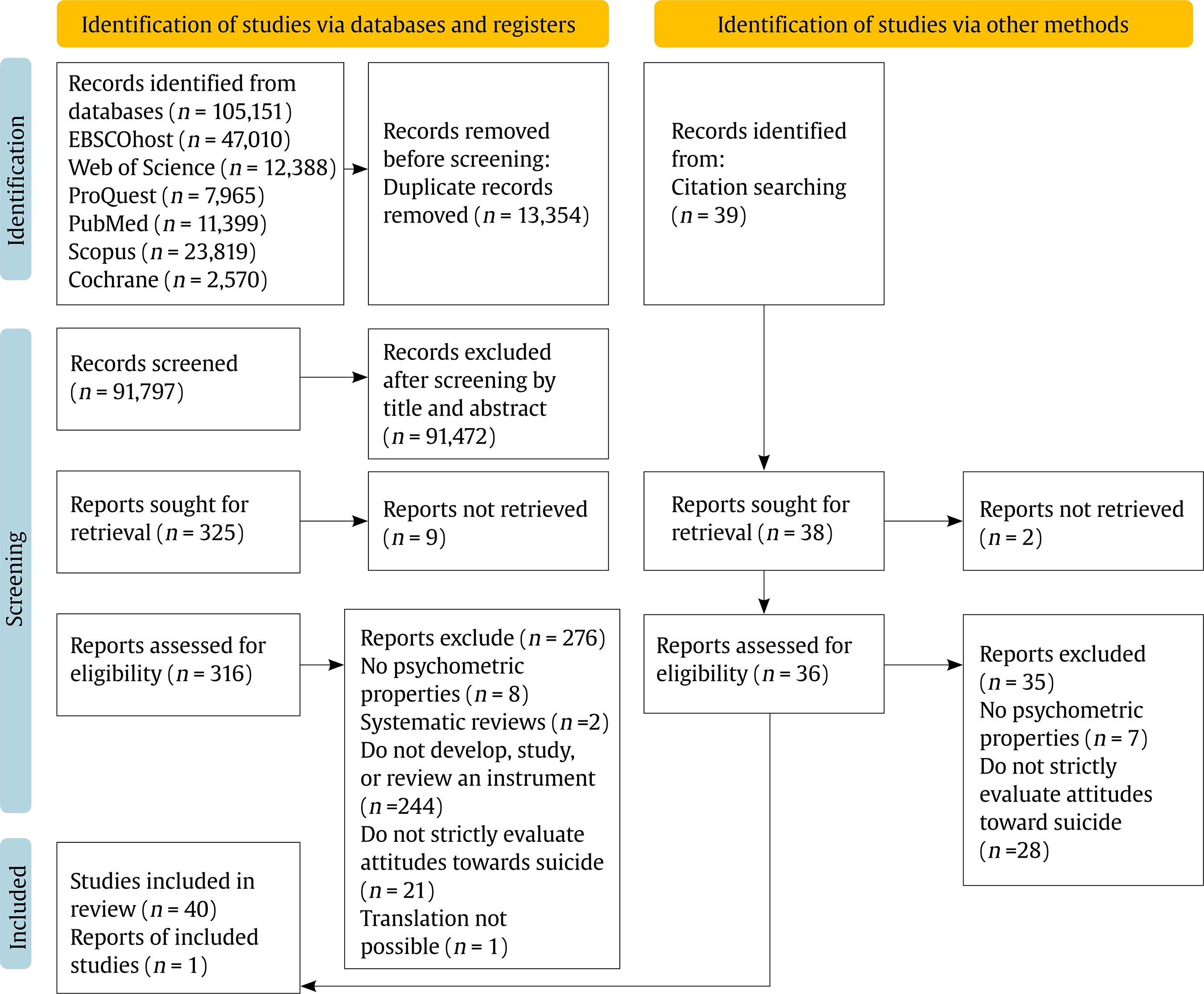

Background/Aim: Suicide is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon that involves multiple variables, among which attitudes stand out. Given its usefulness for suicide prevention and the heteronomy found in the assessment of these attitudes, the aim of this study is to provide an updated synthesis of the instruments available for their evaluation. Method: A systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. The search included articles published up to December 2023 in the databases Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, ProQuest, Cochrane, and the meta-search engine EBSCOHOST. Results: A total of 105,151 papers were obtained, of which 316 were subjected to a full-text screening that identified 41 studies that met the inclusion criteria. We found 14 original instruments, 11 validations in other samples, 13 psychometric studies and 3 papers that developed modified versions of previous questionnaires. Conclusions: This review can serve as a guide for the choice of tools for the assessment of attitudes towards suicide and, in addition, as a complement for studies on the prevention of suicidal behavior. In this way, the results facilitate responsible decision making based on the available evidence and adjusted to the needs of the professional.

Resumen

Antecedentes/Objetivos: El suicidio es un fenómeno complejo y multidimensional en el que intervienen múltiples variables entre las que destacan las actitudes. Dada su utilidad para la prevención del suicidio y la heteronomía encontrada en la evaluación de dichas actitudes, el objetivo del presente estudio es ofrecer una síntesis actualizada de los instrumentos disponibles para su evaluación. Método: Se realizó una revisión sistemática siguiendo las directrices PRISMA. La búsqueda incluyó artículos publicados hasta diciembre de 2023 en las bases de datos Scopus, Pubmed, Web of Science, Proquest, Cochrane y el metabuscador EBSCOHOST. Resultados: Se obtuvieron 105,151 trabajos de los cuales 316 fueron sometidos a un cribado de texto completo que permitió identificar 41 estudios que cumplían los criterios de inclusión. Se hallaron 14 instrumentos originales, 11 validaciones en otras muestras, 13 estudios psicométricos y 3 trabajos que desarrollaron versiones modificadas de cuestionarios previos. Conclusiones: Esta revisión puede servir de guía para la elección de herramientas de evaluación de actitudes hacia el suicidio, y, además, ser un complemento de los estudios sobre prevención de la conducta suicida. De esta forma, los resultados expuestos facilitan la toma de decisiones responsable basada en la evidencia disponible y ajustada a las necesidades del profesional.

Keywords

Questionnaire, Qualitative review, Suicide, Reliability, ValidityPalabras clave

Cuestionario, RevisiĂłn cualitativa, Suicidio, Fiabilidad, ValidezCite this article as: Diaz, M., Pina, D., Díez-Gómez, A., Cascales-Martínez, A., López López, R., & Puente-López, E. (2025). Attitudes Towards Suicide: A Systematic Review of Evaluation Instruments in Different Settings. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 89 - 100. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a8

Correspondence: david.pina@unirioja.es (D. Pina).Suicide, understood as the act of ending one’s own life intentionally (World Health Organization [WHO, 2021]), represents a serious public health issue with profound individual and societal consequences (Richardson et al., 2021). Suicidal behavior is multicausal, resulting from the interaction of psychological, social, biological, and cultural factors (Franklin et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2022). Although mental disorders, traumatic experiences and isolation are relevant risk factors (Favril et al., 2022; Jha et al., 2023), the literature also highlights the importance of other variables such as gender, substance use or family environment (Richardson et al., 2023; Seo et al., 2021). Among the various associated variables, attitudes towards suicide have emerged as a potential predictor of suicidal behavior. Theoretically, attitudes are understood as a psychological tendency expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor (Eagly & Chaiken, 1998, p. 269). According to the classic literature (Eagly & Chaiken, 1998), attitudes are composed of three dimensions: cognitive (beliefs and thoughts about suicide), affective (emotional reactions such as sympathy, rejection, or indifference), and behavioral (intention or willingness to act in a certain way towards suicide or individuals experiencing suicidal thoughts) dimensions. Therefore, attitudes towards suicide refer to the degree of favorability or unfavorability towards suicidal behavior, whether at the cognitive, affective or behavioral level. As reported by Zaldívar-Basurto et al. (2023), attitudes towards suicide can be understood as a key factor within psychological models explaining suicidal behavior, particularly within the framework of the integrative model of suicidal behavior. In this model, attitudes are considered part of the cognitive and dispositional factors that influence the emergence and maintenance of suicidal ideation. Likewise, O’Connor’s (2011) Motivational-Volitional Model (MVI) also gives an important role to attitudes by placing them within the motivational phase, where they shape an individual’s perception of suicide as a feasible solution to psychological pain. Thus, both models converge in suggesting that more permissive or normalizing attitudes towards suicide may lower the psychological barriers to the possibility of taking one’s own life. Thus, far from being attitudes, they are not merely contextual or background variables but rather represent a relevant cognitive component that can modulate the transition from suicidal ideation to suicidal behavior. Recently, Lee et al. (2021, 2023) identified three different attitudinal profiles towards suicide: incomprehensible, mixed, and permissive. This classification is based on the degree of acceptability or understanding of suicide, with the incomprehensible profile reflecting the lowest and the permissive profile the highest degree of acceptance. Notably, participants who reported higher levels of suicidal behavior (e.g., ideation, planning) were more likely to exhibit either a permissive or mixed attitudinal profile. On the other hand, Hom et al. (2019) found that stigmatizing attitudes towards suicide, as well as its normalization or glorification, are linked to a higher likelihood of future suicide attempts. Ultimately, individuals who are more inclined to view suicide as a viable option (i.e., those with favorable attitudes towards suicide) tend to exhibit higher levels of ideation and attempts (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). In turn, stigma represents a major barrier to help-seeking, as stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes can minimize the likelihood of disclosure and negatively impact help-seeking behavior (Arnáez et al., 2023; Campos-Arias et al., 2014). The literature suggests an association between more permissive attitudes towards suicide and a range of risk factors, including low self-esteem (Chen et al., 2024), difficulties in emotional regulation (Gómez-Tabares et al., 2020), severe family dysfunction, lack of social support (Sindeev et al., 2019), as well as unfavorable socioeconomic factors (Chen et al., 2024; Hagedoorn et al., 2019). Conversely, several factors have been identified as protective against the development of such attitudes, including democratic parenting styles and perceived family support (Choi et al., 2020; Navia et al., 2020), religiosity, high self-esteem, resilience (Holman & Williams, 2022; Lee et al., 2023), higher educational level and more favorable socioeconomic status (Holman & Williams, 2022; Lee et al., 2023). Despite ongoing research into the assessment attitudes towards suicide, there is still no consensus on the most effective approach (Ghasemi et al., 2015; Kodaka et al., 2011). Attitudes are highly influenced by culture, highlighting the need to evaluate them within their specific socioeconomic context (Eagly & Chaiken, 1998). Moreover, the wide range of instruments used to assess suicide-related attitudes, combined with the variability of these attitudes over time, raises concerns about the reliability of some tools for diagnostic or research purposes, even when they were originally validated (Ghasemi et al., 2015). In this regard, some studies have identified a significant lack of a solid theoretical foundation and some inconsistencies in factor structures, which limit the usefulness of measuring attitudes through standardized instruments in both clinical and research settings (Sandford et al., 2019). Previous studies have attempted to synthesize the available instruments for assessing attitudes towards suicide. For instance, Kodaka et al. (2011) and Ghasemi et al. (2015) identified 15 psychometric tools focused on attitudes towards suicide, such as the Suicide Opinion Questionnaire (SOQ; Domino et al., 1982), the Suicide Attitude Questionnaire (SUIATT; Diekstra & Kerkhof, 1988), and the Attitudes Toward Suicide (ATTS; Renberg & Jacobsson, 2003). While these reviews present various instruments, not all explicitly evaluate attitudes towards suicide, and only a few provide sufficient psychometric data to support meaningful comparison or informed selection. Recently, Nicholas et al. (2022) conducted a similar review but included only instruments exclusively focused on suicide stigma, potentially excluding a substantial body of relevant work. Finally, Moreno et al. (2022) focused their review on implicit measures of suicide risk, which excludes many instruments assessing attitudes towards suicide that could be valuable. In light of the above, there is a clear need for a systematic and comprehensive search for instruments that assess attitudes towards suicide, given their potential as tools for the prevention, intervention, and study of suicidal behavior. Despite several previous reviews on the subject (e.g., Ghasemi et al., 2015; Kodaka et al., 2010; Moreno et al., 2022; Nicholas et al., 2022), certain relevant validated instruments are missing, in addition to those published recently, pointing to the need for a comprehensive update. Much of the previous reviews have focused on suicide risk or related constructs such as stigma, without explicitly conceptualizing attitudes towards suicide as an independent domain. Finally, these studies provide limited information on the psychometric properties of the included instruments. Therefore, the main objective of the present review is to conduct a thorough and up-to-date synthesis of instruments specifically designed to assess attitudes towards suicide, with particular attention to key psychometric indicators such as internal consistency, structural validity, and factor structure. This will support more informed comparisons and guide the selection of the most suitable tools for various application contexts. Specifically, this review aims to: a) identify studies that develop, validate or analyze the psychometric properties of instruments for the assessment of attitudes towards suicide; b) classify the instruments according to the type of study (original, validation, psychometric study and modified versions); c) describe the methodological and sample characteristics of the included studies; d) analyze and synthesize the reported psychometric properties of each instrument; and e) identify the most appropriate instruments for different application contexts based on the available evidence. Search Strategy and Selection Process The study followed the criteria proposed by the PRISMA guidelines (Page et al., 2021) and is registered in PROSPERO with code CRD42023418308. The search was conducted in electronic databases, including Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, ProQuest, Cochrane, and the EBSCOHOST metasearch engine, using terms related to suicide, attitudes, and assessment instruments. The complete search strategy for each database can be found in Supplementary File 1: https://osf.io/82j3k. Additionally, an incidental search of the bibliography of the selected studies was performed to collect relevant papers not identified in the main search. The final search was conducted in January 2024, covering literature up to December 2023. For the selection of full-text articles, duplicates were first removed. Then, titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were screened. The full texts of articles that passed this initial screening were reviewed using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The entire selection process was conducted by two experienced researchers, resolving inconsistencies with a third reviewer. Eligibility Criteria The inclusion criteria were: a) full-text studies published up to December 2023, with no lower limit on the publication year; b) studies published in English or Spanish; c) articles that develop, validate, review, or study the psychometric properties of instruments assessing attitudes towards suicide; d) instruments based on quantitative methodology, specifically through self-report techniques (questionnaires or structured scales); e) studies reporting, at least, one of the following psychometric indicators: internal consistency (Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω), structural validity (Bartlett’s test, KMO index), factor analysis (exploratory or confirmatory), or goodness-of-fit indices (CFI, TLI, RMSEA, etc. ); f) studies with a minimum sample size of 100 participants, or a ratio of 5 to 10 subjects per item, to ensure greater factorial stability and statistical precision (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014; Snook & Gorsuch, 1989). The exclusion criteria were studies that: a) included instruments that only assess attitudes towards euthanasia or assisted suicide, b) documents not available in full text, c) studies that did not report at least one of the indicators of psychometric properties selected in this review, d) instruments that did not assess attitudes towards suicide explicitly, but other related constructs (such as stigma, prevention or ideology, etc). Variable Coding All variables were independently coded by two reviewers and subsequently discussed. Variables related to methodology, sample characteristics, and outcome measures were coded (study design, objectives, eligibility criteria, data collection, selection process, population, sample size, percentage of females, mean age, measured variable, instrument, language, fit indices, etc.). Psychometric properties collected included Cronbach’s alpha (α), the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, the McDonald’s omega coefficient (ω), and Bartlett’s sphericity test. In general, values of .70 or higher for α, KMO, and ω are considered acceptable. For Bartlett’s test, results are considered adequate when they are significant. The goodness-of-fit indices comparative fit index (CFI), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI), normed fit index (NFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were also collected. These indicators are considered adequate when values exceed .90. Finally, the root mean square residual (RMSR) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were included, being considered adequate when their values are lower than .08 (Campo-Arias & Oviedo, 2008; Muñiz, 2018; Tornimbeni et al., 2008). If a study presented multiple models of the same scale, the version recommended by the authors was selected. If no preference was indicated, the model with the best psychometric performance was chosen. In cases where models demonstrated comparable psychometric properties or could not be directly compared due to differing indices, all relevant models were included. Analysis of Methodological Quality The analysis of the methodological quality of the included studies was developed using an adaptation of Prinsen et al.’s (2018) proposed COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures (see Supplementary File 2: https://osf.io/pagd7). This guideline proposes standardized criteria for evaluating studies on psychometric properties, focusing on items related to structural validity (e.g., the adequacy of factor analysis), internal consistency (evidence of prior structural validity and a Cronbach’s alpha > .70), test-retest reliability, and construct validity (assessment and testing of hypotheses). Each item was independently rated by two reviewers in accordance with the guideline’s recommendations. Inter-rater agreement ranged from substantial to perfect, with kappa indices between .741 and 1, and a mean of .93. The lowest levels of agreement were observed for item 2 (κ = .786) and item 5 (κ = .741). Item 2 assessed the calculation of the internal consistency, considering two criteria of: a) minimum evidence of structural validity and b) a Cronbach’s alpha equal to or greater than .70 for each subscale. On the other hand, Item 5 evaluates hypothesis testing for construct validity, taking into account whether any hypothesis is made in this sense and whether it is fulfilled or not. Overall, inter-rater agreement was considered adequate. Study Selection The flowchart describing the process of inclusion and exclusion of the studies selected in the review can be found in Figure 1. The databases identified a total of 105,151 records and 39 more articles were identified through reading the bibliography. After title and abstract screening, a total of 316 potentially eligible records remained. Finally, 41 studies were included in the systematic review. Study Characteristics Fourteen original instruments, 11 validations to other samples, 13 psychometric studies, and 3 studies that developed new versions of the original scale were identified. The total sample size was 18,743 (mean = 435.98, range 40-3,000), with a mean age ranging from 13.0 to 71.8 (weighted mean age = 28.48, range 11-88 years), with female participants ranging from 8% to 90%. Among these studies, 16 used university students, 9 included general population samples, one included an older general population, 6 focused on adolescents (two of which involved clinical populations), 6 were healthcare professionals, 3 involved military populations, one was a clinical sample, and one did not specify the sample type. One of the studies had a sample comprising 45 countries and the rest were carried out in a single country or in two countries, comprising 23 nationalities, the most common being the USA. Detailed information can be found in Supplementary File 3: https://osf.io/42hfz. Description and Psychometric Properties of Instruments The search identified 14 different scales that assess attitudes towards suicide. In summary, these range from short scales (10 items) to longer scales (100 items). Detailed information on these instruments is provided below, structured according to the type of population and is reflected in Supplementary File 4: https://osf.io/hrzm8 General Population Suicide Attitude Questionnaire (SUIATT; Diekstra & Kerhof, 1988) SUIATT is a scale that assesses attitudes towards suicide and suicide attempts in the general population. The scale consists of 64 items in the form of a question with five response options and is structured around three referents: the respondent, a loved one, and other people. The items are developed based on the three-component model of attitudes, which distinguishes between different attitudinal dimensions: affective (e.g., “If the person most near and dear to you would commit suicide, how would you feel about it?”), cognitive (e.g., “Do you think you have the right to commit suicide?”), and instrumental (e.g., “How probable is it for you to commit suicide in case you did suffer from severe and chronic pain?”). The items can be grouped into six factors: (1) perceived probability of suicide by the respondent or their closest person in cases of severe physical impairment and/or social disruption, (2) perceived right to commit suicide and willingness to assist with suicide, (3) rationality vs. mental abnormality, (4) emotional or affective meaning of suicide, (5) probability of suicide by people in general in case of physical and/or social impairment, and (6) consequences of suicide. The authors obtained alpha values ranging from very low to high (.36-.90). Suicide Attitude Vignette Experience (SAVE-L; Stillion et al., 1989) The SAVE-L is a version for the adult population that comes from the SAVE-A instrument (not included in the present study because it did not offer reliability and/or validity values in the original study) aimed at the adolescent population (Stillion et al., 1984). It is composed of 16 hypothetical scenarios in which an individual is facing a problem and either attempts or commits suicide (e.g., a man, who has a car accident resulting in death for two people and physical harm to himself and his wife, attempts suicide). These scenarios are based on literature related to suicide and cover a range of issues, including academic, social, family, personal, physical appearance, substance use, guilt, and health-related problems. After reading each scenario, participants are asked to rate: a) their degree of sympathy for the person in the story, b) their degree of empathy with the person in the story, and c) the degree of agreement with their decision to commit suicide (equivalent to the three scale factors). These three dimensions correspond to the scale’s underlying factors. Responses are recorded using a 5-point Likert scale. The original study reported high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .89 to .96. German Validation of the Concerning Suicide Scale (CCSS; Biblarz at al., 1991; Cwik et al., 2017) The CCSS questionnaire originally developed by Biblarz et al. (1991), not included in the present review because it did not report reliability and/or validity values in the manuscript, assesses suicide-related cognitions in the general population. It is a self-report measure consisting of 20 items with a 5-choice Likert-type response format grouped into 3 factors: right to commit suicide (e.g., “Everyone has the right to commit suicide”), interpersonal gesture (e.g., “Taking my own life would be a good way to make sure I would always be remembered”), and resilience (e.g., “Life would still be worth living even if I would lose my job”’). This test has a German validation (Cwik et al., 2017), which presents a reduced version of 17 items. This validation yields values α = .67-.83, CFI = .92, TLI = .90; KMO = .84; Bartlett = < .001, RMRS = .07, RMSEA = .06 (Cwik et al., 2017). Questionnaire Measuring Attitudes towards Suicide (ATTS; Renberg & Jacobsson, 2003) ATTS assesses attitudes towards suicide in the general population and students. It has been validated in multiple occasions and contexts. The original ATTS study (Renberg & Jacobsson, 2003) proposes two variants of the scale, elaborated approximately 10 years apart. The first version consisted of 20 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, grouped into 8 factors (permissiveness, unpredictability, incomprehensibility, non-communication, right to prevent, preventability, relationship-causation, and suicidal process) where most of the items referred to people in general. The revised version included 34 items with the same response format but reorganized into 10 factors. In this updated structure, the original permissiveness factor was divided into three distinct dimensions: suicide as a right, taboo, and resignation. The predictability and communication factors were combined into a single communication factor and the incomprehensibility factor was split into two (incomprehensibility and normal-common). This new version is based on the theoretical conceptualization of attitudinal areas as a function of different levels of reference (Diekstra & Kerkhof, 1988), incorporating formulations of other referents (self and close relative). Subsequent work by Hjelmeland et al. (2006) proposes two models, of 31 (in Norwegian population) and 35 items (in Uganda), both with 11 factors (they add the aging factor). In their 31-item version, they obtained an α = .32-.63, while in the 31-item version they obtained an α = .32-.63, whereas in the 35-item version they obtained an α = .28-.84. This scale has also been validated in other countries. On the one hand, de Stecz (2021) validated it in Polish population, reducing the scale to 18 items and 5 factors (α = .54-.83, KMO= .85, Bartlett= χ2 (153) = 1383.523, p <.001, CFI = .89, TLI/NNFI =.86, RMSEA = .07, and AGFI = .81). On the other hand, a first Korean validation (Ji et al., 2016) reduced the scale to only 6 factors, based on those that obtained an acceptable internal consistency score and test-retest reliability (ICC coefficients of .78, p < .001 and ICC coefficient values > .7 in 5 of the 11 factors). In turn, Kim et al. (2022), also in Korea, maintain the original structure and extend it to 37 items (KMO = .082 and Bartlett = p <.001). In addition, Kim et al. (2022), tested a model with 9 factors (although only 4 were significant) and 29 items that showed low internal consistency (α = .29-.73) (Kim et al., 2022). Austrian Validation of the Eskin’s Attitudes Toward Suicide Scale (ATSS; Eskin, 2004) ATSS is a questionnaire originally developed by Eskin (2004) that assesses students’ attitudes towards suicide. It is composed of 24 items with 5 Likert-type response categories that are grouped into 6 factors: acceptability of suicide (e.g., “Someone who is tired of living has the right to kill him/herself”), suicide as a sign of mental illness (e.g., “People who attempt suicide are mentally ill”), punishment after death (e.g., “People who attempt suicide are going to be punished in the next world”), communicating psychological problems (e.g., “People should tell their psychological problems to their friends”), hiding suicidal behavior (e.g., “Families whose daughter or son attempts suicide should hide this from their neighbors”), and open reporting and discussion of suicide (e.g., “Suicide news should be written openly in the newspapers”). The original study (Eskin, 2004) did not provide reliability and validity values and was therefore not included in the present review. Subsequently, it has been validated in Austria in the general population, showing the following values: CFI= .93, TLI/NNFI = .92 and RMSEA = .08 (Nader et al., 2012). Chinese Attitude toward Suicide Questionnaire (CASQ-HK; Lee et al., 2007) The CASQ-HK is an instrument validated in China in the general population. This scale assesses attitudes towards suicide with 98 items divided into three parts: a) 73 statements about attitudes towards suicide on a Likert-type scale with 5 response options, b) 12 statements about difficult situations such as “terminal illness” or “severe depression”, and c) 13 items about sociodemographic characteristics, presence of severe suicidal ideation prior to the suicide attempt and knowledge of someone who had attempted or committed suicide previously. These items are grouped into 9 factors: negative appraisal, stigma, suicidal spectrum, fatalism, social change, support, contagiousness, sympathy, and function of suicide. The total Cronbach’s alpha of the CASQ-HK is .85, while the alpha of the factors ranges from α = .31 to α = .74. Predicament Questionnaire (PQ; Shahtahmasebi et al., 2016) The PQ was developed with the aim of exploring cross-cultural differences in suicide. It is a questionnaire validated in the general population in 45 countries. In this instrument, 32 real-life situations are presented, some of which present complexity or unpleasantness, for example, in the situation of a romantic breakup, two different scenarios are presented: if the characters do not live together or if they have been married for a year. Respondents are asked to focus on the typical responses of people in their community/culture, indicating whether the designated character would have suicidal thoughts. If yes, the respondent is asked to indicate the degree, from mild to strong, where “strong suicidal intent” are those thoughts that could result in suicidal actions. The level of agreement/disagreement with the outcome of each situation is also assessed, with 1 being “none” and 4 being “strong”. Using this scale, the total number of items for each respondent is a measure of suicidal attitude (SA) for each individual, which takes a value between 32 (none/low suicidality) and 128 (very high suicidality). The reliability of this instrument was Cronbach’s alpha = .88, KMO = .90, and Bartlett = < .001. Young and University Population Suicide Opinion Questionnaire (SOQ; Domino et al., 1982) The SOQ is a questionnaire that has been validated in university students, although the original study was conducted in the general American population. The original questionnaire (Domino et al., 1982), not included in the present review because it did not report reliability and/or validity values, consists of 100 items with 5 response options. In addition, it has 7 open-ended items that assess sociodemographic data and personal experiences of suicide. The items were originally grouped into 15 factors: acceptability and normality (e.g., “Potentially, every one of us can be a suicide victim”), mental and moral illness (e.g., “Those who commit suicide are cowards and cannot face life’s challenges”), suicide as semi-serious (e.g., “Once a person survives a suicide attempt, the probability of his trying again is minimal”), religion (e.g., “Most people who commit suicide do not believe in God”), risk (e.g. “A large percentage of suicide victims come from broken homes”), lethality (e.g., “A suicide attempt is essentially a call for help”), normality (e.g., “Suicide is normal behavior”), irreversibility (e.g., “The large majority of suicide attempts result in death”), demographic aspects (e.g., “The suicide rate is higher for blacks than for whites”), aging (e.g., “Most suicide victims are older persons with little to live for”), motivation (e.g., “Most persons who attempt suicide are lonely and depressed”), impulsivity (e.g., “Those who threaten to commit suicide rarely do so”), getting even (e.g., “Many suicides are the result of the desire of the victim to ‘get even’ with someone”), individual aspects (e.g., “Most people who commit suicide do not believe in an afterlife”), and sensation-seeking (e.g., “People who engage in dangerous sports like automobile racing probably have an unconscious wish to die”). Different versions of this questionnaire have been developed. In its version of 100 items and 8 factors (mental illness, cry for help, right to die, religion, impulsivity, normality, aggression, moral evil) its psychometric properties were α = .41-.76, TLI = .63, NFI = .58 and RMSEA = .05 (Anderson et al., 2007) and, α = .23-.76, NFI = .46, TLI = .58 and RMSEA = .056 (Anderson et al., 2008; Domino et al., 2000). Other studies group the 100 items into 5 factors (acceptability, perceived factual knowledge, social disintegration, personal defect, emotional disturbance) with indicators α = .53-.82, NFI = .52, TLI = .63, and RMSEA = .056 (Rogers & Deshon, 1992). In its 4-factor version (erroneous assumptions about suicide, emotional disturbance, acceptability, sitgma associated with suicide) values of α = .57-0.85, KMO = .95 and Bartlett = χ2(4950) = 57947.73, p < .01 were observed (VanSickle et al., 2016a). In addition to the above, two short versions of the scale were found. On the one hand, one of 52 items grouped into 5 factors (Anderson et al., 2008; Rogers & DeShon, 1992; Lester, 2009) with α = .53-.88, NFI = .26-.52, TLI = .63, and RMSEA = .056. On the other hand, the version of 32 items grouped into 2 factors (factual knowledge and acceptability of suicide) (Anderson et al., 2008) shows α = .86, NFI = .62, TLI = .67, and RMSEA = .08. All versions have been validated on U.S. college student or general population samples, except for the studies by Anderson et al. (2008), with a Taiwanese sample, and the study by VanSickle et al. (2016a), with a U.S. military sample. Multi Attitude Suicide Tendency Scale (MAST; Orbach et al., 1991) The MAST, a validation created to assess suicidality in young people, has multiple psychometric studies. In all these studies, 30 items were used, except in 2 that used a shorter version (Osman et al., 2000; Wong, 2004). The items are presented in a Likert-type response format with five options reflecting the degree of agreement or disagreement. They are grouped into four factors: attraction to life (e.g., “I enjoy many things in life”), repulsion to life (e.g., “No one really loves me”), attraction to death (e.g., “In some situations, it is better to die than to go on living”), and repulsion to death (e.g., “I fear death because all my plans would come to an end”). It has been validated in samples from the USA, South Africa, Israel, and China. By type of population, it has been validated in clinical adolescent population, normative adolescents and university students. The alpha values obtained in these studies range from .52 to .96. As for other indexes, it was reported: KMO = .79-.89, NNFI = .93-.98, and RMSEA = .06-.09. In its short version (MAST-28) also obtained adequate values (α = .78 - .89, NNFI = .90, and RMSEA = .06) (Osman et al., 2000), including in its validation in Chinese population (Wong, 2004) (total α = .60, α = .73-.92, CFI = .91, RMSEA = .05, and AGFI = .85). Suicide Attitudes and Attribution Scale (SAAS; Sorjonen, 2002-2003) The SAAS is an instrument that was created to evaluate attitudes towards suicide in Swedish university students. For its application, participants are presented with a fictional case describing a person who commits suicide after a period of high work-related stress. Three variables are manipulated, resulting in 8 possible scenarios: 1) the deceased is a man named Lars or a woman named Lena, 2) the deceased is either married or unmarried, and 3) the deceased either has children (an eight-year-old daughter and a five-year-old son) or does not. Respondents are then asked to indicate their level of agreement with 47 items concerning the characteristics, nature, and causes of the suicide, using a 7-point Likert-type scale. It has 7 factors which are: negative view, right, respect, manipulate, death-wish, external attribution, and internal attribution. Variability is observed in the alpha values, ranging from .55 to .81. Questionnaire of Attitudinal Beliefs about Suicidal Behavior (CCCS-18; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2005) The CCCS-18 assesses attitudes towards suicide in university students. In its original validation it has 18 statements in a Likert-type response format with 7 levels of agreement/disagreement (e.g., “If someone wants to attempt suicide, it is their business and we should not intervene” or “If I felt very lonely and depressed I would attempt suicide”), which are grouped into 4 factors: legitimization of suicide, suicide in terminally ill patients, moral dimension of suicide, and suicide itself. The validation of the original questionnaire shows a Cronbach’s alpha of .87 for the overall scores and an alpha between .73 and .87 for the different factors, each explaining at least 12% of the variance. In addition, with respect to goodness of fit the model obtains GFI = .83, AGFI =.78 and RMSEA = .08. Yatt Suicide Attitude Scale (YSAS; Ibrahim et al., 2019) The YSAS is a validated instrument in a Malaysian university population aged 18-25 years. It was designed to assess two stages of the suicidal process in two subscales: suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. The questionnaire is composed of these two components of Suicidal Attitude and consists of 10 items with 5 Likert-type response options. Psychometric analyses show a Cronbach’s alpha > .80 for both factors. Subsequently, Ibrahim et al. (2022) validated the questionnaire to English obtaining α => .80 and KMO = .89. In addition, in this study they point out the suitability of the instrument because it is shorter than other scales, with simpler sentences and suitable for users who have English as a second language. Suicide Acceptance Questionnaire (SAQ; Stecz, 2020) The SAQ is based on a survey by Hołyst (2002) of views on suicide. This scale assesses the acceptance of suicide in Polish university students. It consists of 10 items in a 5-choice Likert-type response format, as opposed to the original scale, which consisted of 15 items with 3 response options. The reduction of items is justified because the excluded items are not exclusively related to the concept of suicide acceptance, but are associated with other attitudinal objects such as euthanasia or prevention. The items are grouped into a single factor: attitudes towards suicide. The internal consistency of the instrument was ω = .92. The score measured by the SAQ reflects the justification of suicide as a solution and uses a score range from 10 (low acceptance of suicide) to 50 (high acceptance of suicide). Argentine Validation of the Questionnaire of Attitudinal Beliefs about Suicidal Behavior (CCCS-18; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2005) (Desuque et al., 2011) Desuque et al. (2011) conducted an Argentine validation of the CCCS-18 questionnaire, developed in Spain, in adolescent population. In this study, the grouping of items was reduced to 3 factors: own and others’ suicide, terminally ill and right to suicide, and moral dimension of suicide. The internal reliability of the overall scale was .86. This three-factor model, contrasted with the four-factor model, presented slightly higher fit and error indices (GFI = .83, AGFI = .78, RMSEA = .07). Healthcare Population Semantic Differential scale Attitudes towards Suicidal behaviour (SEDAS; Jenner & Niesing, 2000) SEDAS was created and validated in Dutch professionals who were related to and/or had contact with suicide in their work. It has 36 items on suicidal behavior of different actors in different situations, which are: (a) myself, (b) a 14-year-old adolescent, (c) an 81-year-old person with no will to live, (d) a 34-year-old drug abuser addicted for many years, (e) a patient with a tumor that cannot be removed surgically, (f) a person with a history of repeated suicide attempts, and (g) a loved one. Responses are collected using a semantic differential format with 15 adjective pairs (e.g., impulsive-deliberate, natural-unnatural, selfish-altruistic), all rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale. The responses are grouped into two factors: Health/Illness and Acceptance/Rejection. Reported Cronbach’s alpha values range from .70 to .86. Suicide Behavior Attitude Questionnaire (SBAQ; Botega et al., 2005) The SBAQ assesses attitudes toward suicide in nursing staff through 21 statements followed by a visual analog scale (VAS), consisting of a 100-millimeters continuous line ranging from strongly disagree at one end to strongly agree at the other. The respondent is asked to indicate the point on each line that best reflects their opinions, feelings or reactions. This instrument is grouped into 3 factors feelings towards the patient, professional capacity, and right to suicide. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of .70, .60 and .50, respectively, were found in the original version. Subsequently, Ferrara et al. (2021) performed a validation of the questionnaire in Italian population, showing a higher internal consistency than the original (α ≥ .70) through a four-factor structure and the elimination of 5 items. In addition, they report an adequate test-retest reliability (rho = .92, p < .001) and a CVI-I of .97. Finally, Karoui et al. (2022) carried out an adaptation to Arabic, in which they obtain internal consistency values α = .74. As in the original version, they extract three factors. Attitudes Towards Attempted Suicide-Questionnaire (ATAS-Q; Ouzouni & Nakakis, 2009) The ATAS-Q is a questionnaire constructed to assess attitudes towards suicide in healthcare personnel (physicians and nurses). It was originally validated in Greece. It consists of 80 affirmations (e.g. “people who attempt commit suicide are usually mentally ill”) with 5 Likert-type response format that are grouped into 8 factors (positiveness, acceptability, religiosity, professional role and care, manipulation, personality traits, mental illness, and discrimination) and all present α values between .59 and .95 for the subscales. The internal consistency of the test is high, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .96. Barlett’s test was significant (p < .01) and the sample value of the KMO test was .80. Attitude Scale Towards Attempted Suicide Cases for Evaluating Emergency Medical Teams (ASETSA; Gülistan et al., 2013) ASETSA is a scale validated in emergency medical teams in Turkey, which aims to assess attitudes towards suicide in healthcare personnel. A 28-item attitude scale was developed (11 of them extracted from the ATAS-Q) and included subscales for prevention and protection (e.g., “Suicide is not a solution”), individual help (e.g., “I like to help patients who attempted suicide”), institutional help (e.g., “Patients who attempted suicide were treated mercifully in the department I work”), triggers and psychopathology (e.g., “The people attempted to commit suicide are unhappy”), causal attributions (e.g., “personality traits affect suicide attempts”), and medical help (e.g., “Health workers can help the person who attempted suicide”). The final questionnaire includes 58 items with 5 response options that are grouped into 8 factors: affirmation, acceptance, religion, professional role and maintenance, case, management, personal characteristics, mental illness and discrimination. The Cronbach’s alpha value of the scale was .84. Adaptation of the Questionnaire of Attitudinal Beliefs about Suicidal Behavior (CCCS-18; Ruiz-Hernández et al., 2005) to Healthcare Personnel (Villacieros et al., 2016) The CCCS-18 has been adapted for application to healthcare personnel (Villacieros et al., 2016). The authors concluded that the structure that best fits in this population is the three-factor model, joining the original factors of suicide legitimization and suicide in terminally ill patients into a single construct. The scale indicators in this study were ω = .68 -.92, Bartlett = χ2(132) = 260.50, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06. Military Population Military Suicide Attitudes Questionnaire (MSAQ; Vansickle et al., 2016b) The MSAQ assesses attitudes towards suicide specifically in U.S. military personnel. It contains 32 items with 5 response options. The instrument presents a four-factor model that explained 46.4% of the variance: 1) individual-based rejection versus acceptance (e.g., “Admitting thoughts of suicide should not harm someone’s career”), 2) psychache versus pathological (e.g., “Those who attempt suicide just want attention”), 3) Unit-based rejection - Military Unit acceptance (e.g., “Suicide hurts unit functioning”), and 4) moral versus immoral (e.g., “Choosing suicide is morally wrong”). The questionnaire presents an internal consistency >.70 and CFI values .94-.97), TLI .92-.95 and RMSEA .05-.07. Its short version (MASQ-SF, Cramer et al., 2022) is composed of 18 items in the same response format that are grouped into these 4 factors: a) discomfort, b) unacceptability, c) empathic view, d) support. The consistency of this new scale was α = .77-.83 with TLI and CFI values > .90, aRMRS = .07, and RMSEA = .06. Clinical Population Structure of the Verbal Suicide Scale (VSS; Koweszko et al., 2016) The VSS has been validated in hospitalized psychiatric patients aged 19-67 years in Poland. It assesses verbalizations of attitudes towards suicide. It contains 30 items, in which the respondents have to mark a series of words according to what they consider best describes suicide. The structure of the instrument is divided into 3 factors: avoidance of suffering, internalized aggression, and hopelessness. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .71 to .88. The selection of appropriate assessment and screening tools is a challenge for professionals, especially for those with limited experience in a complex area such as attitudes towards suicide. Thus, the findings presented here provide a broad spectrum of tools of interest for both clinical practitioners and researchers. The main objective of the present study was to conduct a systematic review of available validated suicide attitude assessment instruments and their psychometric properties. Forty-one studies were identified, including 17 different psychometric instruments assessing attitudes towards suicide, with their respective validations. These findings update and complement the evidence obtained in the previous reviews by Kodaka et al. (2011) and Ghasemi et al. (2015). The instruments that have not been taken into account in the previous reviews are 7: ASETSA, VSS, PQ, MSAQ, CCSS, YSAS, and SAQ, as well as multiple validations and studies not included in these works. In addition, this study sought to include only instruments that explicitly assess attitudes towards suicide, excluding those that measure related concepts as examined in the recent reviews by Moreno et al. (2022) and Nicholas et al. (2022). Instruments assessing attitudes towards suicide prevention or self-harming behaviors were also excluded, as they do not align with the construct defined in this study. In accordance with recommendations from several authors (e.g., Sellbom & Tellegen, 2019), the choice of an instrument should not rely solely on its psychometric properties. Following the International Test Commission (2013) guidelines, the choice of instrument should be guided by the population and language in which it was developed or validated. As it is impossible to make a universally applicable recommendation, we will highlight the instruments with the best psychometric indicators according to their target population. The recommendations presented here should be interpreted with caution, taking into account the sociodemographic, cultural and linguistic characteristics of the target population. As previously mentioned, attitudes towards suicide are influenced by cultural factors, which limits the cross-cultural applicability of existing instruments and requires careful adaptation to the particularities of the context being assessed (Eskin et al., 2022). Young and University Population Based on our findings, one of the most frequently studied populations has been university students. Meta-analyses estimate a high prevalence of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation in this group (Crispim et al., 2021; Mortier et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2015). Some meta-analyses have estimated a high prevalence of suicidal behavior in this group (Crispim et al., 2021; Mortier et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2015) in which Kamaruddinn et al. (2023), observed a high relationship between attitudes and suicidal behavior. For this population, nine instruments were identified, among which only the MAST, SBAQ-ita (specific to nursing students), CCCS-18, YSAS, and SAQ reported indices within values considered acceptable. Depending on the assessment objective, different instruments offer specific advantages. Both the YSAS and the SAQ stand out for their brevity and high internal reliability, making them particularly suitable for contexts in which streamlining the assessment process is essential. However, the psychometric properties of the CCCS-18 and the MAST are also adequate, and their greater length allows for more in-depth evaluations. In the case of the MAST, it has also been validated in the adolescent population and could therefore be used in more contexts, facilitating comparisons between population groups. Finally, the SBAQ-ita has been validated exclusively in healthcare students, so it is not clear that it is suitable for different types of students. General Population The study of attitudes towards suicide in the general population is also a topic of global interest. Approximately one in five individuals in Europe have wished to die at some point in their lives (Castillejos et al., 2021). Given that attitudes towards suicide are considered a risk factor for suicidal behavior, it is important to have validated population-specific instruments for use in non-clinical adult samples. In this regard, 9 instruments have been identified for the assessment of attitudes towards suicide in the general population. Among these, the ATTS, the PQ scale and/or the CCSS are recommended for their greater accumulated evidence and psychometric properties. On the other hand, for the older population, the SAVE-L is recommended, since it has been specifically validated in this sample and has high reliability. Clinical Population Historically, suicidal behavior has been associated with health problems. This is evident in areas such as psychological disorders (San Too et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019a), sleep disorders (Palagini et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2019b), and cancer diagnoses (Rafiei et al., 2023). In addition, evidence points to attitudes towards suicide as a relevant factor in mental health (Gómez-Tabares et al., 2020). Thus, examining these attitudes within clinical population is essential. Given the wide variability of situations, it is not possible to recommend a single instrument that could be used in all clinical contexts. Nevertheless, among the instruments included in this study, those designed for clinical populations and reporting adequate psychometric values are the MAST and VSS. Healthcare Professionals The study of attitudes towards suicide among healthcare professionals addresses two needs. On the one hand, due to the nature of their job, healthcare professionals are themselves at high risk of suicidal behavior (Dong et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2019). These professionals are more likely to be exposed to individuals with suicidal behaviors, which has been associated with a higher risk of experiencing suicidal behavior in the future (Hill et al., 2020). For this purpose, the SEDAS and CCCS-18 instruments are recommended, as they show adequate psychometric properties and specifically assess attitudes towards suicide. On the other hand, healthcare professionals frequently interact with patients exhibiting suicidal behavior, making their attitudes towards suicide highly relevant in clinical care. In this context, Rayner et al. (2019) conclude that some healthcare professionals may show low empathy and a negative attitude towards patients who present suicidal behavior, potentially harming the professional-user relationship. Therefore, assessing these attitudes can be a first step in improving user treatment and prevention. In this context, the SBAQ and ASETSA are recommended, as they assess this type of attitudes and show adequate reliability (Sahin-Bayindir & Comez-Ikican, 2025). Military Population In the military population, a high prevalence of psychological disorders and suicidal behavior has been reported (Moradi et al., 2021). A recent study by Gutierrez et al. (2021) on the clinical utility of various measures of suicide behavior in military populations concluded that, among the scales examined (Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale, Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire, Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire-Revised, and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation), no single scale emerged as the most effective for assessing suicide risk. To ensure a more comprehensive and in-depth evaluation that enhances the detection of suicide risk, it may be beneficial to incorporate instruments that assess attitudes towards suicide in this population. Based on the findings of the present review, the MSAQ and its short form (MSAQ-SF) are recommended for this purpose. Forensic Evaluation The present review does not include instruments that assess attitudes towards suicide within forensic populations. This is a clear limitation of the current research, which highlights the need for future studies to focus on the validation of specific instruments in this context. The assessment of suicide cases and suicide risk is crucial within forensic psychology. On one hand, forensic psychologists play a key role in investigating suicide cases to distinguish them from homicides through psychological autopsies, suicide note analysis, and behavioral assessments. These tools allow for an in-depth understanding of the circumstances surrounding the death (Bhardwaj et al., 2024). On the other hand, forensic psychologists also play a crucial role in evaluating suicide risk within forensic populations. Evidence shows that self-harm risk, including both non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts, is a serious behavior especially prevalent in forensic populations, where incidence rates are notably higher (Laporte et al., 2021). Individuals with a history of violent behavior often struggle to control negative emotions, which may lead to impulsive self-harm as a maladaptive coping mechanism (Andrade et al., 2024; Saab et al., 2021; Streb et al., 2021). Given the severity of these behaviors in this population, many jurisdictions impose legal requirements obligating professionals to take action to prevent suicide when significant risks are detected, with legal responsibility ensuing if adequate assessment is not conducted (Pinals, 2019; Quevedo-Blasco et al., 2023). In this context, standardized questionnaires with high internal consistency and reliability can support other tools like clinical interviews and the evaluator’s clinical judgment. However, excessive reliance on questionnaires should be avoided due to the unique challenges of the forensic setting, such as the presence of ulterior motives (Deeb et al., 2024; Palena et al., 2024). Here, individuals may exaggerate or feign symptoms to gain benefits, such as economic incentives, access to drugs in cases of addiction, or avoidance of responsibilities or legal consequences (Pina et al., 2022; Walczyk et al., 2018). Therefore, ensuring convergence of evidence through multiple assessments to confirm consistent results is crucial for enhancing the validity of conclusions (Ryan & Oquendo, 2020). Given the importance of suicide risk assessment in forensic psychology, it is essential to continue researching questionnaires and tools tailored to the specific needs of this field. Final Considerations As observed, most scales assessing attitudes towards suicide are multidimensional, with the exception of the PQ and SAQ scales, which derive their measurements from a single general factor. The main challenge in such cases lies in the operational definition of the variable and the clear identification of the most representative behaviors associated with attitudes towards suicide, an essential aspect for the design and reliability of any questionnaire (Muñiz, 2004). For more effective assessment and detection of suicidal behavior, incorporating multiple indicators and risk factors seems to be key, as well as approaching suicide from various dimensions. Thus, some works point out the importance of using multifactorial models and tools, as opposed to those of a single factor, since they could show greater accuracy, sensitivity, and clinical utility in the prediction of suicidal behavior and psychological disorders in general (Seyedsalehi & Fazel, 2024; Steeg et al., 2018; Tutun et al., 2023). Furthermore, it should be kept in mind that in the psychological assessment process, self-report measures should not be relied upon as the sole method of evaluating the object of study. Self-reports are susceptible to response biases, which, in the context of attitude assessment, may be particularly influenced by social desirability. Therefore, other assessment techniques should be considered, integrating different tools that can provide a comprehensive, in-depth and objective assessment, such as ecological momentary assessment. Thus, the assessment of suicide risk should not only include attitudes towards suicide, but also the evaluation of other contextual factors (García-Haro et al., 2023). Limitations Finally, this study is not without limitations. First, due to the broad variety of terms used to refer to the concept of attitudes, and despite using numerous related terms, other terminologies may have been overlooked. Thus, the conceptual complexity involved in defining “attitudes” is a limitation of research in this area, since many studies do not differentiate between related but different constructs, such as beliefs, opinions and/or feelings. Another limitation is the choice of fit indices; some differing scores reported in other studies were excluded, as were studies lacking the selected indicators. Additionally, not all studies provide the same indices, complicating the comparison of scales regarding psychometric quality. In this regard, the assessment of the psychometric adequacy of the instruments is made difficult by the wide variability in the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients reported in some studies. Many of them present wide ranges that make it impossible to clearly determine whether the values obtained reflect an acceptable level of reliability. This heterogeneity limits the possibility of establishing solid conclusions regarding the internal consistency of the instruments analyzed and therefore limits their recommendation. Furthermore, in studying attitudes towards suicide, various types of attitudes have been proposed which, as previously mentioned, require distinct evaluation approaches, also complicating the comparison among these instruments. In relation to the correction and interpretation of the instruments, it was found that none of the studies reviewed provided cut-off points or standardization procedures to determine to what extent a score reflects a greater or lesser risk of suicide. For the most part, the instruments are limited to interpreting high scores as indicative of more favorable or unfavorable attitudes towards suicide, without clear guidance on their behavioral implication. This situation makes the interpretation of the results difficult, especially considering that some instruments understand a favorable attitude towards suicide as a risk factor (reflecting a greater acceptance of suicide as an option), while others interpret a favorable attitude towards suicidal people as a potentially protective characteristic, for example, in contexts of the work of health personnel, as previously mentioned. This lack of unified criteria represents a significant limitation in the field of psychometric assessment of attitudes towards suicide, as no identified instrument provides a standardized framework for interpreting the results as a function of the level of suicidal risk of the individual being assessed. Regarding the methodological quality of the studies, most validations are limited to analyzing the factorial structure and internal consistency of the instruments, often omitting reliability indicators such as measurement error, measurement invariance, criterion validity, or sensitivity. These methodological limitations highlight the need for a deeper analysis of instruments to ensure their suitability for assessing attitudes towards suicide and, consequently, their usefulness in its prevention. The recommendations made here are intended as a guide and should be approached with caution due to the difficulty in comparing the various indices offered by each instrument. Professionals interested in these tools should draw their own conclusions based on their specific needs. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that none of the included instruments report all of the indicators selected in this review, indicating a need for further work on improving these instruments’ properties or developing new evaluation tools. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Diaz, M., Pina, D., Díez-Gómez, A., Cascales-Martínez, A., López López, R., & Puente-López, E. (2025). Attitudes towards suicide: A systematic review of evaluation instruments in different settings. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 7(2), 89-100. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a8 References |

Cite this article as: Diaz, M., Pina, D., Díez-Gómez, A., Cascales-Martínez, A., López López, R., & Puente-López, E. (2025). Attitudes Towards Suicide: A Systematic Review of Evaluation Instruments in Different Settings. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 17(2), 89 - 100. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2025a8

Correspondence: david.pina@unirioja.es (D. Pina).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS