Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia in Court: Legal Professionals’ Experience with Traumatic Memory Loss Claims

[Memoria reprimida y amnesia disociativa en los juzgados y tribunales: experiencia de los operadores jurídicos con las denuncias por pérdida de memoria de un evento traumático]

Ivan Mangiulli1, 2, Fabiana Battista1, Antonietta Curci1, Henry Otgaar2,3

1University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, Italy; 2Leuven Institute of Criminology, Faculty of Law and Criminology, Leuven, Belgium; 3University, Maastricht, Maastricht, The Netherlands

https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2026a1

Received 12 February 2025, Accepted 27 November 2025

Abstract

Background/Aim: Repressed memory and dissociative amnesia are contested concepts in psychology with serious ramifications in the courtroom. We investigated whether legal professionals (judges, prosecutors, and lawyers) had encountered these concepts in the legal arena, their beliefs concerning them, and gathered insights from their practical experiences. Method: A total of 77 legal professionals answered a survey about thier beliefs and practical experiences with repressed memories and dissociative amnesia in court. Results: Reported encountering cases involving repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, and that such cases have increased over time, particularly during 2010-2023. Interestingly, most legal professionals opposed setting time limits after which the retrieval of traumatic experiences should be considered unreliable. Moreover, many participants held inaccurate beliefs about traumatic memory. Conclusions: These findings highlight the critical need for improved education on traumatic memory loss among legal professionals and law students to ensure fair and accurate handling of cases involving such claims.

Resumen

Antecedentes/objetivo: La memoria reprimida y la amnesia disociativa son conceptos controvertidos en psicología, con serias repercusiones en los tribunales. Hemos investigado si los operadores jurídicos (jueces, fiscales y abogados) se han topado con estos conceptos en el terreno legal, sus creencias al respecto y su experiencia práctica. Método: Un total de 77 operadores jurídicos respondieron a una encuesta sobre creencias y experiencias prácticas en juzgados y tribunales con memorias reprimidas y amnesia disociativa. Resultados: Los operadores jurídicos dicen que se han encontrado con casos sobre memoria reprimida y amnesia disociativa, aumentando tales casos con el tiempo, sobre todo en el periodo 2010-2023 y, lo que es más interesante, la mayoría de los operadores jurídicos se han opuesto a poner límites temporales, más allá de los cuales la recuperación de experiencias traumáticas podrían ser consideradas poco fiables. Por otra parte, muchos operadores mantienen creencias inexactas sobre la memoria traumática. Conclusiones: Estos resultados destacan la necesidad imperiosa de mejorar la formación de los operadores jurídicos y estudiantes de Derecho en la pérdida traumática de memoria para garantizar un manejo justo y preciso de los casos que presentan estas reclamaciones.

Keywords

Repressed memory, Dissociative amnesia, Traumatic memory loss, Legal professionals’ beliefs, Court proceedings

Palabras clave

Memoria reprimida, Amnesia disociativa, Pérdida traumática de memoria, Creencias de los operadores jurídicos, Procesos judiciales

Cite this article as: Mangiulli, I., Battista, F., Curci, A., & Otgaar, H. (2026). Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia in Court: Legal Professionals’ Experience with Traumatic Memory Loss Claims. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 18, Article e260176. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2026a1

Correspondence: ivan.mangiulli@uniba.it (I. Mangiulli).

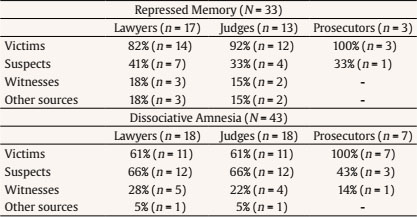

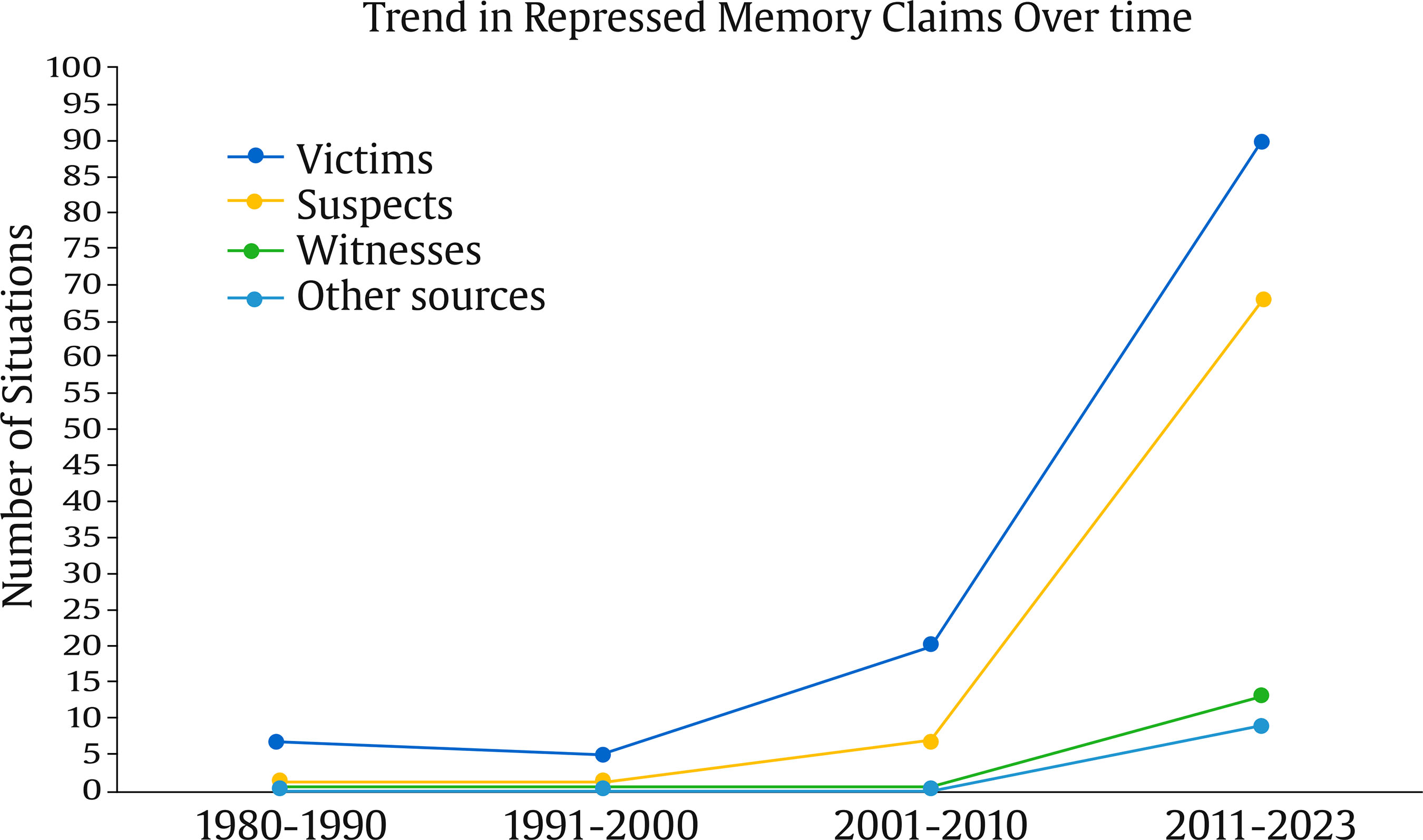

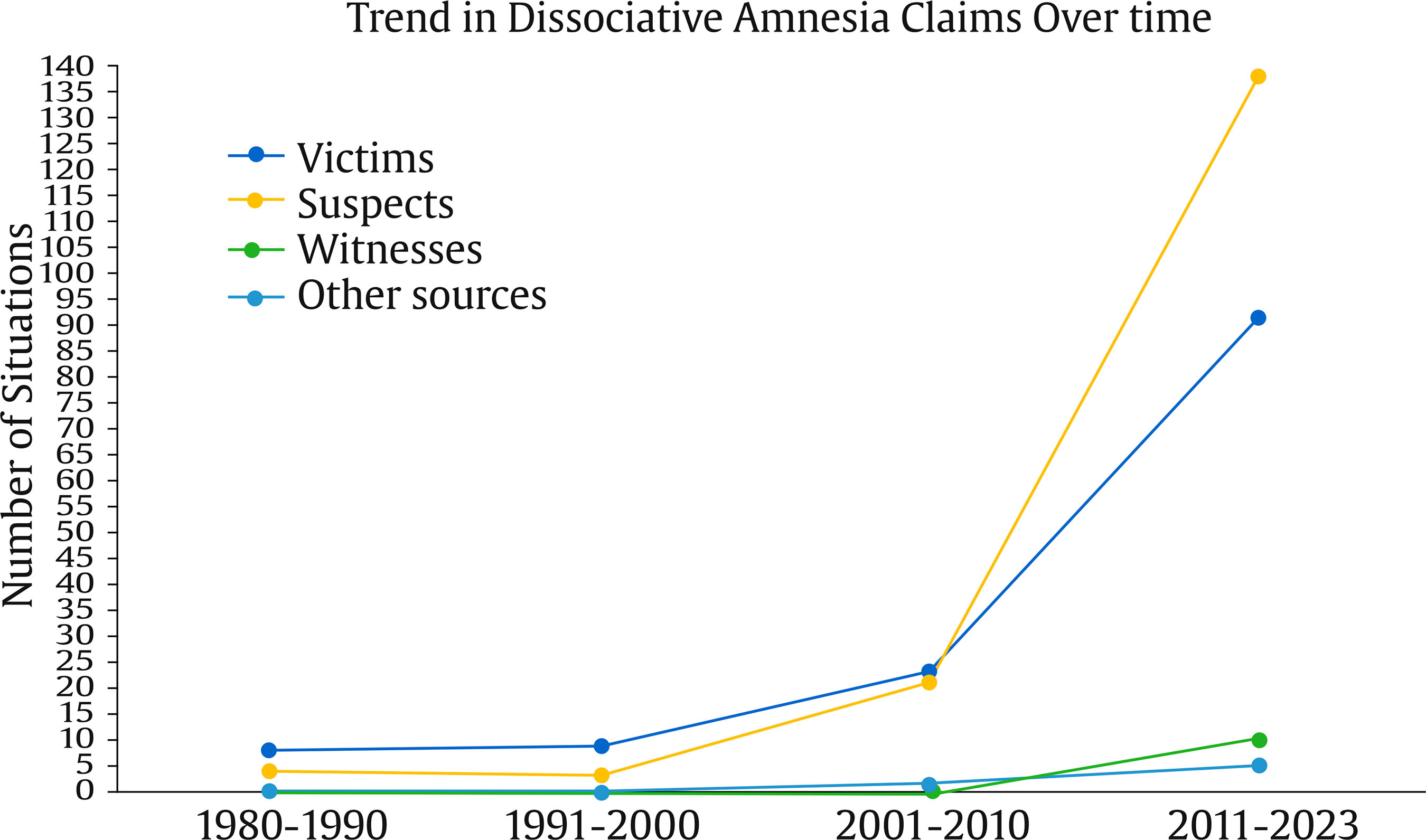

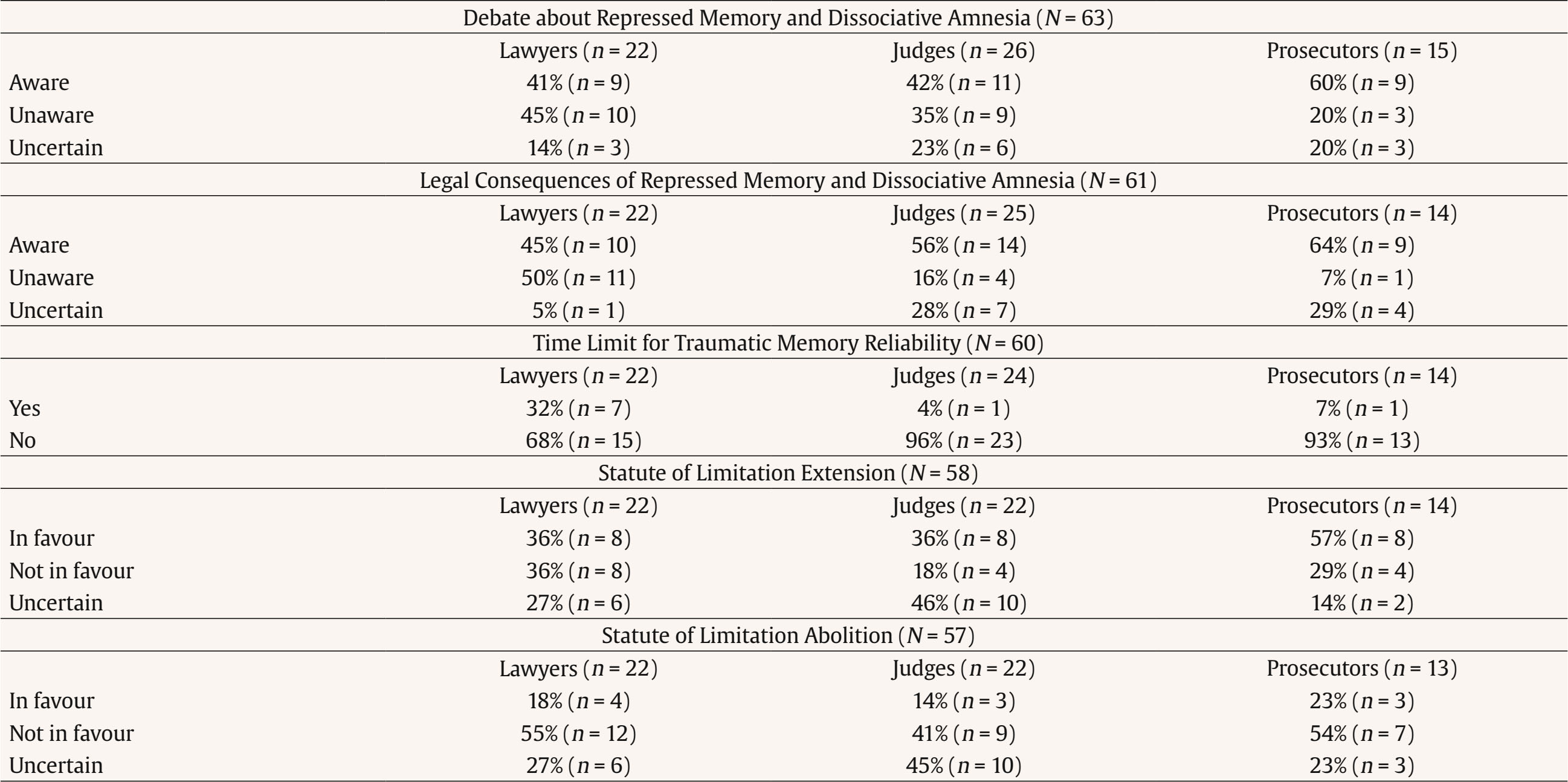

The concepts of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia have been the subject of intense debate within psychological science and beyond (Battista et al., 2023). Repressed memories refer to unconscious traumatic memories that cannot be recalled until they are later recovered, often through therapeutic intervention (Loftus, 1994). Dissociative amnesia involves a more general inability to recall important autobiographical information, typically after experiencing severe trauma (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The concepts of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia are closely related and often used to describe responses to traumatic or highly stressful experiences (Battista et al., 2023; Mangiulli et al., 2025; Mangiulli, Otgaar, et al., 2022). Proponents of these concepts (e.g., Brewer et al., 1996; Dalenberg et al., 2012; Staniloiu & Markowitsch, 2024; van der Kolk & Fisler, 1995) argue that the overwhelming trauma can trigger a defense mechanism in the mind, leading to either a complete unconscious repression of the memory (repressed memory) or a dissociation from the memory itself (dissociative amnesia). To some extent, these two distinct mechanisms suggest distinct processes at play. However, scholars have contended that these phenomena are nothing more than an overlapping entities (Battista et al., 2023; Holmes, 1994; Mangiulli, Otgaar, et al., 2022; Otgaar et al., 2019; Pope et al., 2007; Salkeld & Patihis, 2025). Indeed, both concepts emphasize the inability to consciously access particular memories. While repressed memory suggests the memory is unconsciously blocked, dissociative amnesia focuses on the difficulty of retrieval due to emotional barriers. Ultimately, the outcome is the same: the memory is temporarily inaccessible. Moreover, techniques used to recover repressed memories often overlap with those used to treat dissociative amnesia. Specifically, therapists might use hypnosis, guided imagery, or exploration of emotional triggers to unlock traumatic experiences (Cassel & Humphreys, 2016; Fine, 2012). Although these phenomena have long captivated public and scientific interest, they remain highly contentious (Otgaar et al., 2019). Cognitive psychological research provides a nuanced understanding of how trauma can impact memory (Dodier et al., 2024). First of all, a substantial body of research indicates that traumatic experiences are generally well remembered (Goodman-Brown et al., 2003; Merckelbach et al., 2003; Wagenaar & Groeneweg, 1990), meaning that trauma and stressful memories are rarely, if ever, completely forgotten (Goldfarb et al., 2019; McNally, 2003). Rather, trauma survivors might choose not to think about or discuss their experiences (Goodman et al., 2003). Moreover, they may sometimes even forget details of the traumatic events, but this does not equate to the unconscious repression of or dissociation from the distressing incidents (Arnold & Lindsay, 2002; McNally, 2003, 2007; Merckelbach et al., 2006). Additionally, some people might not have perceived the event as traumatic at the time it occurred and only later reinterpret it as abusive (McNally & Geraerts, 2009; Patihis & Pendergrast, 2019; Schooler, 2001). Furthermore, people undergoing suggestive techniques, such as hypnosis or guided imagery, may recover repressed memories or recover from dissociative amnesia, when in fact they are recalling false memories (Howe & Knott, 2015; Lilienfeld, 2007; Lynn et al., 2003). With these considerations in mind, several concerns arise regarding the reliability of recovering allegedly repressed or dissociated memories, not only in clinical and academic settings but also, and particularly, within the legal field (Deferme et al., 2024). The debate over the existence of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia remains unresolved in clinical and academic circles, such that there is a dearth of research on the extent of this debate within the legal domain (Battista et al., 2023). Specifically, claims of repressed memory or dissociative amnesia in court may have dramatic consequences, wherein such claims could allow someone to potentially falsely accuse another person of, for instance, sexual abuse based on the recovery of a purported memory (Smeets et al., 2017). Nonetheless, the legal system operates on a foundation of solid evidence and established timelines to prosecute crimes. Statutes of limitations, which set deadlines for filing lawsuits, often hinge on the moment victims become aware of their abuse and file official complaints. Here, the question of memory recovery becomes a critical battleground (Ernsdorff & Loftus, 1993). Recently, Deferme et al. (2024) highlighted how in recent years some European countries have extended or abolished the statute of limitations for prosecuting sexual crimes. For instance, in France, the statute of limitations for sexual offenses against minors was extended to 30 years in 2018 to give victims more time to file complaints, considering that repressed traumatic memories might delay reporting (Dodier & Tomas, 2019). Parliamentary debates in 2021, sparked by a high-profile abuse case, led to further reform. The statute of limitations for a first offense was extended to match that of a subsequent offense, effectively abolishing it for repeat offenders. This change aimed to address the issue of delayed reporting due to repressed memory claims.1,2 Moreover, in Belgium, a law enacted on November 14, 2019,3 eliminated the statute of limitations for sexual offenses against minors. This change aligns with a broader legislative trend toward extending limitation periods for sexual offenses and crimes committed against minors (Deferme & Otgaar, 2020; Meese, 2017), a trend also supported at the international level. While this decision was primarily aimed at strengthening the rights of victims of sexual abuse who may come forward with an accusation many years after the crime, the Belgian legislators did not thoroughly examine the possible drawbacks of extending these statutory limitations (Deferme et al., 2024). That is, the absence of statutes of limitations can shift the emphasis to certain types of evidence, hypothetically compromising the defence’s ability to counter the claims. This often results in greater reliance on victims’ memories for abuse from a distant past. In such cases, diagnosing dissociative amnesia could inappropriately influence the court’s evaluation of these memories. Over time, moreover, memories are prone to change (Kensinger & Ford, 2020) as the likelihood of forgetting and memory distortions can increase (Brainerd et al., 2008). Such a risk is heightened because victims may encounter misinformation about the event over time. For instance, discussions with family, friends, or therapists who pose suggestive questions can facilitate false memory formation (Loftus, 2005; Principe et al., 2006; Principe & Schindewolf, 2012). The abolition or extension of the statute of limitations has sometimes directly been motivated by incorrect beliefs about how memory works when encoding, retaining, and retrieving traumatic experiences (see Dodier & Tomas, 2019). Over the past few decades, numerous studies have indicated that clinical psychologists, other mental health professionals (Murphy et al., 2025; Ost et al., 2017; Patihis & Pendergrast, 2019; Schemmel et al., 2024; Yapko, 1994; Zappalà et al., 2024), and laypeople (Magnussen et al., 2006; Mangiulli et al., 2021; Merckelbach & Wessel, 1998; Patihis et al., 2014) often support the notion that traumatic memories are subjected to special memory mechanisms. For instance, they believe that the mind can unconsciously block traumatic memories from awareness. Overall, it is estimated that more than one out of two people hold a firm belief in the existence of repressed memory and/or dissociative amnesia (Otgaar et al., 2019). While beliefs of clinical experts and laypeople regarding traumatic memory loss have been extensively studied, there is a notable gap in research concerning the knowledge of other professionals who also require accurate understanding of memory, such as law enforcement officers (Odinot et al., 2015) and child protection workers (Erens et al., 2020). Notably, very few studies have specifically examined legal professionals’ beliefs about how memory works in these circumstances. Recently, Radcliffe and Patihis (2024) found that a significant majority of legal professionals hold beliefs about the concepts of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. Specifically, 78% (n = 117) of legal professionals endorsed the idea that traumatic memories are often repressed, which is concerning given the potential implications for legal proceedings. Additionally, 88% (n = 132) of their sample agreed that dissociative amnesia can prevent individuals from recalling traumatic experiences. Moreover, Benton et al. (2006) found that 73% (n = 81) of jurors, 50% (n = 21) of judges, and 65% (n = 34) of law enforcement personnel endorsed belief in long-term repressed memories. Although scholars may argue that legal professionals are likely to be skeptical of memory loss claims during criminal cases, thereby causing courts to question their validity (Porter et al., 2001), others contend that cases concerning repressed memory and dissociative amnesia continue to find their way into judicial proceedings (Mangiulli, Riesthuis, et al., 2022; Otgaar et al., 2019). For instance, Otgaar et al. (2019) examined cases in the Netherlands from 1990 to 2018 in which traumatic memory loss was a factor. The authors showed that the incidence of cases referencing repressed memories and dissociative amnesia had grown over time. Therefore, understanding how these concepts are perceived by professionals involved in judicial proceedings is urgently needed. The Current Study To address this gap, the current study aimed to provide a timely and comprehensive examination not only of the beliefs held by legal professionals (i.e., lawyers, judges, and prosecutors) regarding repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, but also to address a more relevant issue. That is, we specifically investigated legal professionals’ familiarity and experience with these phenomena. This is particularly important given the influential role these professionals play in the adjudication of cases involving traumatic memory claims (Otgaar et al., 2019). We aimed to estimate how frequently these claims are made and to identify the typical sources (e.g., victims, suspects, eyewitnesses) of cases involving them. Furthermore, considering the debate surrounding the extension and abolition of statutes of limitations for prosecuting sexual crimes (Deferme et al., 2024), we assessed the level of understanding among legal professionals regarding the controversial nature of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia along with their potential legal repercussions. Finally, we examined whether misconceptions about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia were prevalent among legal professionals. In this latter regard, and in line with previous research (e.g., Benton et al., 2006; Erens et al., 2020; Odinot et al., 2015; Radcliffe & Patihis, 2024), we anticipated that the majority of our sample would agree with most of the proposed notions regarding those two concepts. By investigating these issues, our final aim in the present study was to illuminate the extent to which misconceptions about traumatic memory loss might impact judicial outcomes and inform future reforms in legal practice and policy. Participants We recruited legal professionals working in Belgian criminal law by reaching out to them via email, using publicly available contact addresses listed on the websites of their respective professional associations (e.g., ‘Orde van Advocaten’ and ‘College van Procureurs-Generaal’). Acknowledging the potential difficulty in accessing such a sample, our goal was to contact as many legal professionals as possible without setting a predetermined number of participants. We reached 101 people, of whom 24 did not start the survey after giving their consent to take part in it. Eventually, we gathered relevant information from 77 legal professionals (Mage = 42.62, SD = 10.79, range = 27-65, 63.6% females). On average, our sample had worked in the criminal law field for 17.77 years (SD = 10.62, range = 2-40), and demonstrated optimal proficiency in English, French, and Flemish. Our participants were judges (40.3%, n = 31, 54.8% female), followed by lawyers (35.1%, n = 27, 63% female), prosecutors (24.7%, n = 19, 78.9% females). Note that, however, as participants continued with the survey, we experienced some dropouts. Consequently, the number of respondents for certain questions (see, for instance, part 2 and 3 of the results section) varied from the original total number of participants. The current project was approved by the Social and Societal Ethics Committee at KU Leuven (G-2021-4308-R2[MAR]). The survey and the dataset are available on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/wnju7/?view_only=6c6fa82f18cb4c5aac24ff08586c98a5).4 Procedure The survey was conducted in English, created with Qualtrics, and distributed to participants via an internet link. Before starting the survey, participants were informed about its purpose and reminded of the definitions4 of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. After giving informed consent, participants first provided demographic information and then proceeded to the survey, which consisted of three main sections. Each section ended with an attention-check question (e.g., “Please answer false to the following question”). No participants were excluded, as none failed the three attention checks. Finally, all participants were thanked for their participation and debriefed. Part 1: Claims of Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia in Court In the first part of our survey, we aimed to collect information about the occurrence of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims in court. Specifically, participants were asked if they were aware of any cases where these issues played a role in any stage of a judicial proceeding. To the best of their knowledge, they were then asked to indicate among different sources (i.e., victims, suspects, witnesses, forensic experts, jurors, or the media covering the case), which most frequently made claims of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. For this question, participants could select multiple answers. Subsequently, participants were asked if they had personally been involved (meaning directly handling, investigating, or adjudicating) in cases where repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims were mentioned during judicial proceedings. If so, they had to indicate, to the best of their knowledge, an estimate of how many such cases they had been involved in, specifying both the source of the claims and the decade in which the case occurred (i.e., 1980-1990, 1991-2000, 2001-2010, 2011-2023). Part 2: Awareness of the Debate Surrounding Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia and its Consequences In the second part of our survey, we investigated whether our participants were aware of the current debate about the existence of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia (Battista et al., 2023) and of the legal implications that such issues could have. For both questions, participants indicated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly unaware (1) to strongly aware (5)5. Moreover, participants were asked whether they believed there should be a time limit after which the recall of traumatic experiences should be considered likely unreliable. If they answered affirmatively, they were asked to estimate such a time limit (i.e., 1-2 years, 3-5 years, 10 years or more). Next, they were asked if they supported extending or abolishing the statute of limitations for prosecuting sexual abuse based on the notion that traumatic experiences could lead to repressed memory or dissociative amnesia (Deferme et al., 2024). For both questions, participants indicated their level of support on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly not in favour (1) to strongly in favour (5)6. Part 3: Acquired Knowledge and Beliefs about Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia In the final part of our survey, we examined the primary ways in which legal professionals learned about dissociative amnesia and repressed memory. These sources included education (school and/or university/college), media (newspapers, science magazines, scientific books), the Internet, through movies and/or crime fiction, via novels and/or short stories, their professional work, or through the current survey. Additionally, in line with previous work (see Mangiulli et al., 2021), we asked participants to rate ten statements related to contentious aspects of repressed memory (e.g., “Repressed memories for events that did happen can be accurately retrieved in therapy”) and dissociative amnesia (e.g., “People who experienced traumatic events during their childhood, such as sexual abuse, are likely to suffer from amnesia for those events”). Participants rated these statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5)7 Claims of Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia in Court Among the surveyed legal professionals, 42.85% (n = 33/77) and 55.84% (n = 43/77) were aware of cases where claims of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, respectively, played a role during a judicial proceeding. Overall, when repressed memory issues were brought up during legal proceedings, most of the claims were made by victims (88%, n = 29/33). Similarly, when dissociative amnesia issues were raised, many of the claims were made by victims (67%, n = 29/43). Table 1 displays judges’, lawyers’, and prosecutors’ self-reported frequency of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims in courtroom as a condition of the different sources. We tested the association between the type of claim (repressed memory versus dissociative amnesia) and the sources of the claim (victims, suspects, witnesses, etc.). However, we found no statistically significant association between the two variables, χ2(3) = 6.42, p = .093, Cramer’s V = .23, 95% CI [.043, .280], meaning that there was no evidence suggesting that the distribution of the sources of claims differed between repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. Table 1 Legal Professionals’ Self-reported Frequency of Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia Claims in Courtroom as a Condition of Different Sources, Split by Lawyers, Judges, and Prosecutors   Note. Percentages have been rounded up to the nearest whole number. Forensic experts, jurors and media coverage were grouped into other sources. Note that for this question, participants were allowed to select multiple answers. Next, among the surveyed legal professionals, 42.4% (n = 28/66) reported that they were personally involved in cases where repressed memory issues were raised. Legal professionals reported being involved in a total of 220 situations, M = 55, SD = 53.91; lawyers: 24.09% (n = 53), judges: 49.10% (n = 108), prosecutors: 26.81% (n = 59), where the issue of repressed memory was mentioned during the legal proceedings over the four decades. A Poisson regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the trend in repressed memory cases from 1980 to 2023. The trend was statistically significant (Wald χ2 = 173.83, p < .001, IRR = 1.145, 95% CI [1.122, .168]), meaning that repressed memory claims statistically increased over time. This result was confirmed even when taking into account the number of participants active during each decade, based on their years of experience (i.e., 1980-1990: 3 participants; 1991-2000: 7 participants; 2001-2010: 18 participants; 2011-2023: 28 participants), z = 13.185, p < .001. Victims and suspects were the primary sources of these claims. As a matter of fact, over the four decades, 55% (n = 121/220) of the claims came from victims, followed by suspects with 35% (n = 77/220). A chi-square test, χ2(3, N = 220), = 87.42, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .36, 95% CI [.018, .119], showed that victims and suspects were reported more frequently than it would be expected under the equal contribution assumption, whereas witnesses, 5.91% (n = 13), and the other categories, 4.09% (n = 9), were reported less frequently. Figure 1 illustrates the trend of repressed memory claims over time. Figure 1 Number of Repressed Memory Cases in Which 28 Participants Reported Involvement, Divided by Source across Four Decades.   Regarding dissociative amnesia, 50.7% (n = 38/75) of surveyed legal professionals reported involvement in a total of 323 cases, M = 81, SD = 82.94; lawyers: 36.53% (n = 118), judges: 58.51% (n = 189), prosecutors: 4.96% (n = 16), where dissociative amnesia claims were raised during judicial proceedings across four decades. Of interest, and as with repressed memory, this trend was statistically significant over time (Wald χ2 = 244.41, p < .001, IRR = 1.121, 95% CI [1.105, 0.138]), meaning that dissociative amnesia claims statistically increased from 1980 to 2023. The trend in dissociative amnesia cases over time remained statistically significant even after accounting for the number of active participants per decade (i.e., 1980-1990: 3 participants; 1991-2000: 8 participants; 2001-2010: 27 participants; 2011-2023: 38 participants), z = 2.773, p = .006. Over the four decades, suspects, 52.32% (n = 169/323) and victims, 41.48% (n = 134/323), were the primary sources of these claims. Data demonstrated that suspects and victims were reported more frequently than it would be expected under the equal contribution assumption, whereas witnesses, 3.41% (n = 11), and the other categories, 2.79% (n = 9), were reported less frequently, χ2(3, N = 323), = 154.39, p < .001, Cramer’s V = .40, 95% CI [.015 .098]. Figure 2 shows the trend of dissociative amnesia cases over time. Figure 2 Number of Dissociative Amnesia Cases in Which 38 Participants Reported Involvement, Divided by Source across Four Decades.   Finally, a Mann-Whitney U test showed that the number of dissociative amnesia cases (M = 81, SD = 82.94, Mdn = 31) was not statistically significantly different from the number of repressed memory cases (M = 55, SD = 53.91, Mdn = 17), W = 11, p = .468, r = .26, 95% CI [.096 .410]. Awareness of the Debate Surrounding Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia and its Consequences Almost half of the legal professionals (46.1%, n = 29/63) reported being aware of the debate surrounding repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, while 34.9% (n = 22/63) were not. The remaining 19% (n = 12/63) indicated uncertainty about their awareness of the debate. Similarly, 54.1% (n = 33/61) of participants disclosed being aware of the legal consequences that repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims may cause, while 26.2% (n = 16/61) were not. The remaining participants (21%, n = 12/61) indicated uncertainty. Moving on to the time-limit issue (Deferme et al., 2024), only 15% (n = 9/60) of participants answered that there should be a time limit after which the recall of traumatic experiences should be regarded as likely to be unreliable. Among those, 33% (n = 3/9) indicated 1-2 years as an estimate of the time limit, while the remaining participants indicated 3-5 years (33%, n = 3/9) or 10 years or more (33%, n = 3/9), respectively. A large majority of surveyed legal professionals (85%, n = 51/60) stated that there should not be a time limit for such situations. Furthermore, the majority of our participants (41.4%, n = 24/58) expressed their favour in extending the current statute of limitations for persecuting sexual abuse based on the idea that traumatic experiences could lead to repressed memory or dissociative amnesia. While 27.6% (n = 16/58) of participants were not in favour of extending the current statute of limitations, the remaining participants were undecided (31%, n = 18/58). Finally, almost half of the participants (49.1%, n = 28/57) claimed that they were not in favour of completely abolishing the current statute of limitations for prosecuting sexual abuse. Only 17.5% of the surveyed legal professionals (n = 10/57) were in favour, while the rest stated they were uncertain (33.3%, n = 19/57). In Table 2, we present participants’ responses to all the questions regarding this section of the survey, divided by lawyers, judges, and prosecutors. Table 2 Legal Professionals’ Views on the Dispute about Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia, Divided by Lawyers, Judges, and Prosecutors   Note. Percentages have been rounded up to the nearest whole number. Acquired Knowledge and Beliefs about Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia More than one-fourth of our participants (29.8%, n = 17/57) learned about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia through their work, while, interestingly, 24.6% (n = 14/57) acquired knowledge about these concepts because of the current survey, 10.5% (n = 6/57) by reading newspaper and/or science magazine and/or scientific books, 5.3% (n = 3/57) during school and/or university, 3.5% (n = 2/57) via novels and/or short stories, 1.8% (n = 1/57) through movies and/or crime fiction. The remaining participants (24.5%, n = 14/57) reported learning about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia from multiple sources. Table 3 presents the percentage of participants who agreed or disagreed with each of the ten statements about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, categorized by profession (i.e., lawyers, judges, and prosecutors). Overall, the majority of participants agreed with six out of ten statements, which reflected dubious notions regarding both concepts. For instance, 86% (n = 49) agreed with the idea that memory can unconsciously “block out” traumatic events. Similarly, 61% (n = 35) agreed with the notion that people who commit severe and violent crimes can develop dissociative amnesia for those events (see also statements 1, 3, 8, and 9 in Table 3). Additionally, many participants neither agreed nor disagreed with three out of the ten statements. For instance, 44% (n = 25) were undecided about statement 2: “Hypnosis can accurately retrieve memories for events that did happen, but were previously not known to the client/patient” (see also statements 6 and 7 in Table 3). In only one situation, the majority of participants disagreed with a statement. Specifically, 43.9% (n = 25) disagreed with the idea that poor memory of childhood events is indicative of a traumatic childhood. Table 3 Participants’ (N = 57) Frequencies and Percentages of Agreement and Disagreement with Ten Statements about Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia, further Split by Lawyers, Judges, and Prosecutors   Note. Percentages have been rounded up to the nearest whole number. Participants answered to each statement on a fully anchored 5-point Likert scale with the following anchors: strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree and strongly agree. Participants who chose strongly agree and somewhat agree were collapsed as agreeing with a statement, while those who chose strongly disagree and somewhat disagree were counted as disagreeing. Finally, we cross-tabulated participants’ beliefs with their involvement in cases where repressed memory or dissociative amnesia claims were raised. This analysis aimed to determine whether agreement rates with these beliefs were higher among legal professionals who had personal experience with such cases (n = 33) as compared with those who did not (n = 24). However, the relationship between beliefs in repressed memory and dissociative amnesia and participants’ involvement in related cases did not reveal any statistically significant associations for any of the proposed statements (p > .05). We surveyed legal professionals, including lawyers, judges, and prosecutors, to examine their experience with legal cases with repressed memory and dissociative amnesia and investigate their beliefs concerning these concepts. Our main results can be summarized as follows. First, the surveyed legal professionals stated that they had encountered many legal cases in which people claimed to have had repressed memory or dissociative amnesia. Second, while many legal professionals acknowledged the potential consequences of such claims in legal proceedings, they also expressed opposition to time limits on recalling traumatic experiences due to concerns about their reliability. Third, as expected, we showed that a significant portion of legal professionals hold incorrect beliefs about traumatic memory loss. Traumatic Memory Loss Claims in Legal Proceedings Our findings indicate that repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims, particularly from victims and suspects, are frequently present in court proceedings and seem to have increased in legal contexts over time. This finding aligns with previous research indicating a rise in legal cases in which repressed memory and dissociative amnesia have been mentioned and scholarly literature on these concepts over time, especially in the 2010-2023 decade (Battista et al., 2023; Otgaar et al., 2019). Interestingly, this aligns with recent findings by Battista et al. (2023). They observed significant peaks in publication numbers in the field of traumatic memories, particularly between 2012 and 2021, highlighting the continued academic interest in repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. This trend, nonetheless, could be attributed to several factors. One possibility is that there is indeed a genuine rise in the incidence of these phenomena in legal proceedings, possibly due to heightened societal stressors or greater awareness of psychological conditions. Alternatively, this trend might reflect a recency effect, where more recent and memorable cases disproportionately influence perceptions of frequency (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). Also, the increased recognition and acceptance of psychological trauma and its impacts on memory might contribute to the rising number of claims. As legal and clinical practices use trauma-related concepts, individuals may feel encouraged to make claims about repressed memories or dissociative amnesia, even if evidence for their accuracy remains undetermined (Lynn et al., 2003). In our survey, legal professionals reported that both victims and suspects frequently made these claims, with a remarkable distinction in their application: victims often claimed repressed memories, whereas suspects predominantly claimed dissociative amnesia. This pattern suggests that the use of these claims may vary depending on the individual’s role in a proceeding, reflecting differing motivations and, perhaps, psychological states. On the one hand, victims’ claims of repressed memories might be driven by a need for justice or disclosure. This phenomenon, particularly in cases where the abuse allegedly occurred in childhood and was only recalled later in life, has been documented in studies showing that purported memories for traumatic events can be repressed and later recovered (Briere & Conte, 1993; Chu et al., 1999; Freyd, 1996). However, the reliability of such memories remains highly uncertain and contentious within the scientific community (Loftus & Davis, 2006; Otgaar et al., 2019; Otgaar, Howe, et al., 2022). Critics argue that people can be susceptible to suggestive therapeutic interventions that can lead to false recovered memories for abuse (Loftus, 1994, 2005; Otgaar, Curci, et al., 2022). Moreover, victims’ repressed memory claims may also be influenced by the growing societal awareness and acceptance of trauma and its psychological impacts, which could encourage more individuals to come forward with their experiences (Lynn et al., 2015; McNally, 2003; Pope et al., 2007). Relatedly, some researchers argue that dissociative symptoms can sometimes be influenced by external factors which, in turn, may exacerbate the possibility of recovering something that has never occurred. That is, media portrayals of trauma, particularly those that emphasize dissociation as a hallmark of abuse or suggest the development of multiple personalities, can shape incorrect beliefs about how trauma can impede memory (Lynn et al., 2014). On the other hand, in criminal cases dissociative amnesia can manifest as a block on unwanted memories, particularly those related to the crime itself. This phenomenon can act as a coping mechanism or a defense for the offender, shielding them from the emotional distress of the event (Parkin, 1999; Parwatikar et al., 1985). Yet suspects’ claims of dissociative amnesia in court are often questioned, especially because, on average, one-third of violent offenders report memory loss for their actions (Mangiulli, Riesthuis, et al., 2022). Scholars argue that such claims could be malingered (Jelicic, 2018). Offenders may malinger memory loss for several reasons: some may aim to hinder investigations (Tysse, 2005), hoping to weaken the prosecution’s case (Tysse & Hafemeister, 2006), while others might use it to avoid discussing the crime during treatment, as guilt and shame are common among offenders (Cima et al., 2002; Gudjonsson, 2003, 2006). It is not surprising, therefore, that legal professionals in our sample reported that the vast majority of dissociative amnesia claims came from suspects, irrespective of their potential veracity. The Debate Moves to the Court Many legal professionals were aware of the debate about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia and their consequences in legal proceedings. Whereas this awareness is certainly positive, it is concerning that 85% of our sample, mostly represented by judges, stated that there should not be a time limit after which the recall of traumatic experiences was considered likely unreliable. Such a stance is problematic, given the body of research challenging the reliability of repressed and dissociative memories, particularly in court (Dodier & Patihis, 2021). This also suggests a potential willingness among legal professionals to overlook the significant risks of false memories and wrongful convictions. Despite being aware of the debates surrounding repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, many legal professionals, especially judges, seemed willing to accept these claims in court to support allegations of traumatic memory loss. Yet this willingness might reflect a broader inclination to advocate for victims of sexual abuse, particularly those who report traumatic events years after they occurred, by potentially extending the time frame for considering such recovered memories as credible. Research has shown that victims of childhood sexual abuse often delay disclosure due to various psychological and social factors (Goodman et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the inclination to support victims aligns with broader societal movements, such as the xxxMeToo movement8, which emphasizes the importance of believing survivors and creating an environment where they feel safe to disclose their experiences. This societal shift has influenced legal professionals, fostering a more victim-centered approach in legal proceedings (Masters et al., 2015). While well-intentioned, this approach risks neglecting the critical need for evidence-based practice and the potential consequences of accepting unreliable memory claims (Deferme et al., 2024). Once again, it should be acknowledged that the reliability of such delayed memories is oftentimes highly questionable (Goodman et al., 2017). Thus, the stance that there should not be a strict time limit raises significant concerns about the potential for miscarriages of justice. However, balancing this understanding with the need for a fair legal process is crucial. The majority of our sample, predominantly represented by lawyers, did not support completely abolishing the statute of limitations for sexual crimes. This position, perhaps, reflects a necessary concern for safeguarding the rights of the accused. The statute of limitations exists to protect against the erosion of evidence over time, ensuring that defendants have a fair opportunity to present a defense (Connolly & Read, 2006; Deferme et al., 2024). As memories fade and evidence deteriorates, the risk of wrongful convictions increases (Howe & Knott, 2015; Howe et al., 2018). Maintaining some temporal boundaries in legal cases is essential for preserving judicial system integrity. Therefore, these two positions – supporting the reliability of delayed traumatic memory recall and maintaining the statute of limitations for sexual crime – highlight the complex interplay between protecting victims and ensuring a fair legal proceeding. Arguably, legal professionals recognize the need to validate the experiences of trauma survivors while also safeguarding the integrity of the legal system. However, this dual approach must be carefully managed to avoid the pitfalls of endorsing scientifically dubious concepts like repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. Legal Professionals’ Incorrect Beliefs The majority of participants endorsed controversial notions about both repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. They agreed with six out of ten statements, including misconceptions like “trauma memories can be unconsciously blocked” or “violent criminals develop amnesia for their crimes.” This result aligns with previous research showing widespread misconceptions about traumatic memory, among mental health professionals (e.g., Murphy et al., 2025; Schemmel et al., 2024; Zappalà et al., 2024), and non-experts (e.g., Erens et al. 2020; Mangiulli et al., 2021). Of importance, we replicated findings from previous research (e.g., Benton et al. 2006; Radcliffe & Patihis, 2024) showing that a significant number of legal professionals believed in long-term repressed memories. Interestingly, in our study, while some held incorrect beliefs, a substantial portion of participants remained neutral. To some extent, this neutrality may suggest a knowledge gap, as also evidenced by the fact that the majority of participants reported that they either learned about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia through their work or because of our survey. While we suppose that our work helped these latter participants simply to assign a label to notions they already knew, this ambiguity underscores the urgent need for improved education on traumatic memory and the dissemination of evidence-based information within the legal field, starting from law students. The need for better education is further emphasized by research showing that misconceptions about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia can be corrected through targeted educational interventions. That is, recent studies demonstrated that providing law and criminology students with evidence-based knowledge about controversial issues within the legal psychological field (e.g., repressed memory and dissociative amnesia) significantly reduced their endorsement of incorrect beliefs (Battista & De Beuf, 2024; Otgaar, Mangiulli, et al., 2022). We strongly think that a similar approach could be of value. With proper education, future legal professionals can develop a more accurate understanding of traumatic memory, ultimately enhancing the integrity of legal proceedings. Limitations Our work has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, participants’ responses might have been influenced by the ongoing public debate about repressed memory and dissociative amnesia in Belgium (Deferme et al., 2024; Meese, 2017). Media coverage and public discourse on these topics could have shaped participants’ perceptions and responses, potentially introducing bias. This influence underlines the need for caution when interpreting self-reported data, as participants’ views may not solely reflect their professional experiences but also the prevailing societal narratives. Relatedly, and second, it is crucial to note that our findings are based on self-reported data, which inherently lacks corroborating evidence. Therefore, our results should be interpreted with an understanding of these limitations, and future studies should consider incorporating more objective measures or triangulating self-reports with other data sources (e.g., case files). A third limitation concerns participants’ understanding of the concepts of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. Although both terms were presented and defined at the beginning of our survey, we cannot ascertain that all participants read or fully understood these definitions before completing the questionnaire. Hence, this may have influenced how some respondents interpreted the items assessing beliefs about memory, potentially leading to over- or underestimation of certain views. Similar challenges in ensuring construct comprehension have been reported in recent work (see, for instance, Murphy et al., 2025), suggesting that misunderstandings of these complex concepts are not uncommon. Future studies could address this issue by including attention or comprehension checks to ensure that participants’ responses accurately reflect their understanding of the terms provided. A four th caveat of our study is that instances of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia in legal proceedings stemmed from a limited number of legal professionals rather than being broadly representative. However, not every legal professional in Belgium handles cases involving repressed memory and dissociative amnesia. Certain practitioners, perhaps due to their specialization, are more frequently exposed to such claims. This does not imply that these phenomena are rare. Rather, our findings demonstrate that claims of traumatic memory loss are recurrent in court proceedings, underscoring their legal relevance regardless of the number of professionals encountering them directly. Finally, while legal professionals reported that victims often claimed repressed memory and suspects frequently stated dissociative amnesia, we cannot determine whether these claims were inherently distinct or if they were later categorized as such by our sample. It may be that both victims and suspects initially reported a general memory loss, which was subsequently attributed to repressed memory or dissociative amnesia by the legal professionals. Our work did not capture the specifics of these cases where claims of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia were mentioned. Understanding the context in which these claims arise, such as whether victims’ repressed memory claims are primarily associated with sexual abuse cases or whether dissociative amnesia claims are predominantly made by offenders of violent crimes, could provide deeper insights into the application and impact of these concepts in legal settings. The growing frequency of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims in court highlights the critical need for legal professionals to be well-informed about the scientific underpinnings and controversies surrounding these concepts. Misunderstandings or misapplications of these concepts can have significant ramifications for the outcomes of legal cases (Otgaar, Curci, et al., 2022; Otgaar et al., 2023). For instance, the acceptance of repressed memory claims without sufficient scrutiny could lead to wrongful convictions, while (malingered) dissociative amnesia claims could lead judges to consider alternative sentences, potentially including placement in a forensic psychiatric facility, rather than prison (Mangiulli, Riesthuis, et al., 2022). To address these challenges, the legal system needs to integrate robust, evidence-based guidelines for evaluating repressed memory and dissociative amnesia claims (Mangiulli et al., 2025). Training programs and continuing education for legal professionals on the latest research and best practices in legal psychology could enhance their ability to assess such claims critically and fairly. Additionally, interdisciplinary collaboration between legal and psychological experts can foster a more nuanced and informed approach to these complex issues (Howe & Knott, 2015). Such efforts are essential to ensure that legal professionals are well-informed and that justice is administered based on accurate and reliable information. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Notes 1 Bonfils, P. (2021). Protéger les mineurs des crimes et délits sexuels et de l’inceste. Présentation de la loi n° 2021-478 du 21 avril 2021. Droit de la Famille, n° 6. 2 Detraz, S. (2021). Le dédoublement des agressions sexuelles. Commentaire de certaines des dispositions de la loi du 21 avril 2021 visant à protéger les mineurs des crimes et délits sexuels et de l’inceste. Droit Pénal, 6. 3 Official Gazette December 20, 2019 (entry into force December 30, 2019). For revised version of the text see Law March 21, 2022 (Official Gazette March 30, 2022). 4 The exact definitions of repressed memory and dissociative amnesia, that we gave to participants, could be viewed on OSF (https://osf.io/wnju7/?view_only=6c6fa82f18cb4c5aac24ff08586c98a5), at the start of our survey. 5 Participants who chose strongly unaware and somewhat unaware were eventually collapsed as unaware, while those who chose strongly aware and somewhat aware were counted as aware. 6 Participants who chose strongly not in favour and somewhat not in favour were eventually collapsed as not in favour, while those who chose strongly in favour and somewhat in favour were counted as in favour. 7 Participants who chose strongly agree and somewhat agree were eventually collapsed as agreeing with a statement, while those who chose strongly disagree and somewhat disagree were counted as disagreeing. 8 xxxMeToo is a social movement and campaign aimed at raising awareness about sexual abuse, harassment, and rape culture, where women share their personal stories of experiencing sexual misconduct. Cite this article as: Mangiulli, I., Battista, F., Curci, A., & Otgaar, H. (2026). Repressed memory and dissociative amnesia in court: Legal professionals’ experience with traumatic memory loss claims. European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 18, Article e 260176. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2026a1 References |

Cite this article as: Mangiulli, I., Battista, F., Curci, A., & Otgaar, H. (2026). Repressed Memory and Dissociative Amnesia in Court: Legal Professionals’ Experience with Traumatic Memory Loss Claims. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 18, Article e260176. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2026a1

Correspondence: ivan.mangiulli@uniba.it (I. Mangiulli).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS