Stop Harassment! Men's reactions to victims' confrontation

[¡Stop Acoso! Reacciones de los hombres a la confrontación de las víctimas]

María del Carmen Herrera1 , Antonio Herrera1 , Francisca Expósito Jiménez1

1Univ. Granada, Dep. Psicología Social, España

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.06.006

Abstract

Sexual harassment is one of the most widespread forms of gender violence. Perceptions of sexual harassment depend on gender, context, the perceivers' ideology, and a host of other factors. Research has underscored the importance of coping strategies in raising a victim's self-confidence by making her feel that she plays an active role in overcoming her own problems. The aim of this study was to assess the men's perceptions of sexual harassment in relation to different victim responses. The study involved 101men who were administered a questionnaire focusing on two of the most frequent types of harassment(gender harassment vs. unwanted sexual attention) and victim response (confrontation vs. nonconfrontation), both of which were manipulated. Moreover, the influences of ideological variables, ambivalent sexism, and the acceptance of myths of sexual harassment on perception were also assessed. The results highlight the complexities involved in recognizing certain behaviors as harassment and the implications of different victim responses to incidents of harassment. As the coping strategies used by women to confront harassment entail drawbacks that pose problems or hinder them, the design and implementation of prevention and/or education programs should strive to raise awareness among men and women to further their understanding of this construct.

Resumen

El acoso sexual es una de las formas más generalizadas de violencia de género. Las percepciones sobre el acoso sexual dependen de factores tales como el género, el contexto y la ideología del perceptor, entre otros. La investigación ha mostrado la importancia que tiene el afrontamiento de la víctima en su nivel de confianza, haciendo que sienta de esta manera que tiene un papel relevante en la solución del problema. El objetivo de este estudio fue indagar en la percepción que los hombres tienen acerca del acoso sexual y de las distintas medidas usadas como respuesta por parte de la víctima. Participaron en el estudio 101 hombres que contestaron un cuestionario en el que se manipulaban dos de los tipos de acoso más frecuentes(acoso de género vs. atención sexual no deseada) así como la respuesta de la víctima (confrontación vs. noconfrontación). También se estudió la influencia en dicha percepción de variables ideológicas como el sexismo ambivalente y la aceptación de los mitos sobre el acoso sexual. Los resultados resaltan la dificultad de reconocer determinados comportamientos como acoso, así como las posibles consecuencias que puede sufrir la víctima en función de la respuesta que dé a estas situaciones de acoso. Las estrategias usadas por las mujeres para afrontar el acoso parecen presentar algún obstáculo o problema para ellas, por lo que se hace necesaria la implantación de programas preventivos y/o educativos con el fin de enseñar a hombres y mujeres a comprender mejor el constructo.

Sexual harassment is one of the most widespread types of gender violence and is a reflection of the socially imbedded male-dominated power relations between men and women (Hotelling & Zuber, 1997). The gender roles attributed to men and women in society have been cited as one of the main causes of harassment e.g., the "theory of the extension of sexual roles" postulates that men transfer their gender-based role expectations to the workplace, which prompts men to sexually harass the women they work with (Gutek, 1985).

Sexual harassment has become a critical social issue particularly in organizational environments primarily due to the rising number of women who are increasingly absorbed into the labour market (Cunningham & Benavides-Espinoza, 2008; Fitzgerald et al., 1988).

In spite of the array of approaches for defining sexual harassment, most researchers contend that it is a psychological experience based on sexually unwanted, offensive, and threatening behaviour at work (Topa, Morales, & Depolo, 2008, p. 208). Though both men and women may be exposed to sexual harassment, the literature on harassment is consistent in reporting that an overwhelming number of victims are women and harassers, men (Pryor, 1995). Thus, one out of every two women have experienced some type of sexual harassment or have been subjected to unwanted behaviour (Pina, Gannon, & Saunders, 2009).

Strikingly, in Spain there is no official register on the prevalence of sexual harassment at work (AmnistĂa Internacional, 2011). Nevertheless, the most recent figures revealed a total number of 6,573 sexual offences against women in 2009, of which 330 were cases of sexual harassment (Instituto de la Mujer, 2009).

Typologies of Sexual Harassment

Gelfand, Fitzgerald, and Drasgows' (1995) definition distinguishes three types of sexual harassment: gender harassment, unwanted sexual attention, and sexual coercion. Gender harassment (hostile, offensive, intimidating, and degrading verbal and nonverbal behaviour against women) is a type of subtle sexual harassment aimed at deterring women from transgressing male domains. As for unwanted sexual attention, behaviours such as persistent nonreciprocal requests for dates, letters, phone calls, deliberate touching, grabbing, sexual advances and propositions, and assault are among the most evident types of this behaviour. Sexual coercion (also known as quid pro quo or sexual blackmail) is the most explicit and recognizable type of sexual harassment where the harasser, a person in power, demands sexual favours from a subordinate worker in exchange for organizational rewards and benefits or threats of reprisal related to job prospects and conditions, e.g., job security and promotion (Fitzgerald, Drasgow, Hulin, Gelfand, & Magley, 1997). Surprisingly, only a small number of cases of harassment (5-10%) meet the inclusion criteria of coercion (Gelfand et al., 1995), which might explain why research has tended to focus on gender harassment, with an estimated prevalence of 50%, and unwanted sexual attention, with a prevalence ranging from 20 to 25% (Saunders & Senn, 2009). Furthermore, several studies have highlighted that men have a narrow perception of harassment and fail to perceive certain types of more subtle behaviours as harassment, which in spite of being subtle, cause distress and are rebuked by the victim (Baker, Terpstra, & Larntz, 1990; ExpĂłsito & Moya, 2005; Jones & Remland, 1992).

Coping Strategies

The strategies most frequently used by women to cope with harassment range from avoiding or ignoring the harasser (Fitzgerald, Gelfand, & Drasgow, 1995; Swim & Hyers, 1999), to reporting the offence. Unfortunately, none of these strategies has proven to be clearly effective in combating harassment at work, nor in raising the confidence of workers, i.e., potential victims, regarding their expectations concerning their current employers. Studies have shown that women who report incidents of harassment are often threatened with reprisals for reporting the incident or making it public (Bergman, Langhout, Palmieri, Cortina, & Fitzgerald, 2002). A further strategy employed by women in coping with sexual harassment is confronting the harasser; however, few studies have provided data on the outcomes of this strategy. Studies designed to evaluate the reactions of men in response to the coping responses of women, as a first step in gauging the efficacy of this method, have provided data suggesting the outcomes need not be inevitably negative (Saunders & Senn, 2009).

Reaction of Men

The negative reactions of men in response to women who challenged their subordinate position were manifested either directly, e.g., by devaluating or underrating women, or indirectly e.g., perceiving roles in stereotypical or counter-stereotypical terms (Herrera, ExpĂłsito, & Moya, 2012). Other researchers in this field have shown male gender stereotypes are characterised as ambitious, power driven achievers, i.e., personality traits reflecting agentic, instrumental or competent stereotypic dimensions, whereas women are characterised as sympathetic, childrearing, and caring for others, i.e., reflecting communal stereotypic dimensions of expressivity or sociability personality traits (Rudman & Glick, 2008). Moreover, both of these dimensions have been frequently associated to inequality in status and/or power. In other words, high status or powerful individuals are commonly conceived as agentic or competent, whereas low status individuals lacking power are considered to be affectionate and expressive; however, this effect disappeared when the low status group was perceived as dangerous or unwilling to cooperate (Fiske, Cuddy, Glick, & Xu, 2002). Research on what is referred to as the backlash effect (Rudman & Glick, 1999), has shown that Western nations embrace the notion that women are competent, but the underlying attitudes towards agentic women is not as positive as one would initially expect, e.g., they are often chastised for not being as feminine as women should be.

The reaction of men have been found to be most negative when women challenged male authority, which was perceived as undermining male-dominated power relations. Thus, the judgment of men regarding women rested on a woman's willingness to accept male decision-making (Herrera et al., 2012). These results corroborated the findings of several studies that women who transgressed traditional roles were more negatively valued by men (Sakalli-Urgulu & Glick, 2003).

Sexist Ideology and Attitudes towards Sexual Harassment

Relations between men and women are characterized by inequality, which is in part endorsed by hostile sexist ideology grounded on negative views of women. Moreover, benevolent sexism continues to perpetuate inequality as can be seen from the responses and evaluations of men regarding women who transgress traditional roles (Abrams, Viki, Masser, & Bohner, 2003; Sakalli-Urgulu, Yalçin, & Glick, 2007).

Attitudes towards victims, perpetrators, and the offence itself may negatively influence the perception of a phenomenon. Thus, tolerance towards sexual harassment has been found to raise the predisposition to harass, which was positively correlated to sexist ideology, hostility towards women, condoning interpersonal violence, adversarial sexual beliefs, and subscribing to the myth of rape (Walker, Rowe, & Quinsey, 1993).

In general, the results show that the more men or women adhere to traditional gender roles, the greater the tendency to consider certain instances of sexual harassment as acceptable or within the limits of normality in the relations between men and women. Moreover, the more an individual perceives the behaviour as normal, the greater the likelihood they will refute the negative consequences of such behaviour (Quinn, 2002).

In relation to attitudes towards sexual harassment, one may observe that an aspect common to all acts of violence, are the many myths associated to them (Leidig, 1981, p. 199). Myths of sexual harassment include beliefs such as self-victimization is a characteristic common to all women, that women enjoy acts of violence, that these acts are only committed by mentally deranged men, or that women exaggerate their reports. Acceptance of myths hinders the ability to visualize the problem and in turn this lack of awareness undermines the willingness to assist the victim (Lonsway, Cortina, & Magley, 2008).

Thus, the aim of this study was to assess sexual harassment at work by examining the influence of the type of sexual harassment (gender harassment vs. unwanted sexual attention) on perceptions of harassment, and to determine if perceptions influenced the predisposition to commit harassment. Moreover, the relationship between type of sexual harassment and the reaction of men to victim responses was analysed. Furthermore, the influence of victim coping strategies on perceptions of harassment were evaluated, and the efficacy of coping strategies in response to sexual harassment was assessed by examining the reaction of men in relation to type of victim response. Finally, the relationships between coping strategies and certain ideological variables such as ambivalent sexism and the acceptance of myths on sexual harassment were analysed both in terms of perceptions of harassment and in the overall evaluation of women.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of a 101 male undergraduates enrolled at different faculties of the University of Granada, their age ranging from 17 to 58 years ( M = 27.76, SME = 1.08).

Procedure

The sample was obtained through incidental sampling in different classrooms of several faculties at the University of Granada. Having obtained informed consent, participants were given approximately 20 minutes to complete the questionnaire in their habitual classrooms. All participants were assured their information and responses would remain anonymous and confidential. Once all students had completed the study, they were informed about the objectives of the study. All of the participants freely volunteered to respond to the questionnaire, and were awarded an extra 0.1 towards their final grade as compensation. The 101 participants were randomly assigned to one of the following conditions: Gender harassment-Confrontation condition (23), Gender harassment-No confrontation condition (22), Unwanted sexual attention- Confrontation condition (34), and the Unwanted sexual attention- No confrontation condition (22).

Materials and Variables Measured

A questionnaire was administered consisting of all the variables to be measured. Participants were presented a scenario, and told to adopt the role of the protagonist in the following story:

John and Ann are workmates, they have no other relationship other than at work, they are not friends, they don't go out together, nor do they meet up anywhere else than at work, they are only workmates. At work sometimes they talk about everyday tasks, discuss issues about the working day, whether it's been productive or not, the future of the business, any noteworthy events, just normal questions one would expect to discuss with a workmate. During the conversation...

The type of sexual harassment was manipulated by providing participants the following information. For Gender harassment: ... John tells Ann: "You would be better off if you showed off more of your charms..." For Unwanted sexual attention: ... John tells Ann while he puts his hand on her thigh: "I know of a way we can forget about these problems, and get rid of this stress..."

The type of confrontation was manipulated by providing participants the following information. For Confrontation: In view of the situation, Ann responds: "Listen John, your behaviour is entirely unacceptable, what you are doing is called sexual harassment, so I would appreciate it if you would make sure it never happened again." For No confrontation: In view of the situation, Ann feels distressed, but decides to do or say nothing.

Thereafter, the following scales were administered:

1. Gender stereotypes: A scale consisting of 26 items for measuring the masculine perception of women (instrumental), and the feminine perception (expressivity) designed and validated by ExpĂłsito (1995) was used. Examples of instrumental items were: ambitious, independent, self-confident, individualist, leadership qualities, and strong; examples of expressive items: cares for others, kind, warm, sensitive to praise, emotional, and able to understand the feelings of others. Participants were told to imagine they were John and were instructed to indicate the degree to which each item was applicable to the protagonist of the story using a 7-point Likert type response format ranging from 1 ( not at all) to 7 (very much ). The α coefficients for participants were .82 on the instrumentality subscale and .83 for the expressivity subscale.

2. Men's evaluation of women was measured using the items To what extent does Ann match your ideal partner?, with a 7-point response format ranging from 1 ( not at all) to 7 (very much), and I think Ann is an impertinent person, rated on a 7-point Likert type response format ranging from 1 ( totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree).

3. Tendency to commit sexual harassment was measured using the item Personally, if you were sure there would be no consequences and nobody would find out, would you have behaved in the same way as John did?, with a 7-point Likert type response format ranging from 1 ( no, not at all) to 7 (yes, most likely).

4. Perception of sexual harassment was measured using the item Do you think John's behaviour constitutes sexual harassment?, with a 7-point Likert type response format ranging from 1 ( it is not sexual harassment) to 7 (it is sexual harassment).

5. Four items were introduced as manipulation checks: a) Type of harassment: To what extent does John suggest to Ann she would be better off if she showed more of her charms? , that was measured using a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 ( he doesn't suggest it at all) to 7 (he clearly suggests it) and To what extent did John deliberately touch Ann while he suggested a way of forgetting their problems?, measured using a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 ( he din't do it at all) to 7 (he did it deliberately) and b) Confrontation: To what extent did Ann respond assertively to John's behaviour , that is, clearly tell him his behaviour was entirely unacceptable, and that he should ensure it never happened again ?, that was rated on a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 ( she didn't respond assertively) to 7 (she responded assertively) and To what extent does Ann not respond to John's behaviour? , measured using a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 ( no response at all) to 7 (responded fully).

6. The Illinois Sexual Harassment Myth Acceptance (ISHMA) Scale (Lonsway et al., 2008), adapted to the Spanish context for this study by using the back translation method, consisted of 20 items measuring the acceptance of myths about sexual harassment using a 7-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 ( strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The scale comprised four dimensions: Invention/ Exaggeration (α = .86), Hidden Motives (α = .78), Natural Heterosexuality (α = .80), and the Responsibility of Women (α = .74). The α coefficient for the total scale was .93. In this study only the global scores were analysed given that the objective was to obtain an overview of myths rather than focusing on specific dimensions.

7. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI) (Glick, & Fiske, 1996; adapted to the Spanish context by ExpĂłsito, Moya, & Glick, 1998) consisted of 22 items measured on a 6-point Likert type scale ranging from 0 ( totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree ). High scores indicated sexist attitudes. Half of the items (50%) were related to Hostile Sexism (HS) ( women get offended quickly, women exaggerate the problems they have at work... ) and the remainder were related to Benevolent Sexism (BS) ( women are bestowed with a purity that few men possess, a man isn't a man without a woman... ). The α coefficient for the total scale was .93, and the Hostile Sexism Scale (α = .93) and the Benevolent Sexism Scale (α = .85) were positively correlated ( r = .59, p < .001).

Results

The descriptive data (e.g., means, standard deviations) and correlations between the dependent variables are shown in Table 1.

Testing Experimental Manipulations

In order to test the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation of the type of sexual harassment, an ANOVA was performed with the Type of sexual harassment (Gender harassment vs. Unwanted sexual attention) as the grouping variable. The results for the item To what extent did John suggest to Ann she would be better off if she showed more of her charms? showed a significant effect for the factor Type of harassment, F(1, 99) = 18.08, p < .001, ηp 2 = . 154, with fewer participants in the Unwanted sexual attention condition ( M = 3.71) indicating that John had made such suggestion than subjects in the Gender harassment condition ( M = 5.38). For the item To what extent did John deliberately touch Ann while he suggested a way of forgetting their problems? , the results of the ANOVA, F (1, 99) = 74.19, p < .001, ηp 2 = . 428, showed more participants in the Unwanted sexual attention condition ( M = 4.96) indicating Ann was the victim of deliberate touching than subjects in the Gender harassment condition ( M = 2.04).

In order to test the effectiveness of the manipulation of confrontation, an ANOVA was performed on the grouping factor Type of confrontation (Confrontation vs. No-confrontation) as presented in the item To what extent did Ann respond assertively to John's behaviour, that is, clearly tell him his behaviour was entirely unacceptable, and that he should ensure it never happened again ?; the results revealed a significant effect for the factor Type of confrontation, F (1, 99) = 165.03, p < .001, ηp 2 = . 625, with more participants in the Confrontation condition ( M = 6.23) indicating that Ann responded assertively to John's behaviour than subjects in the No-confrontation condition ( M = 2.50). Moreover, the results for the item To what extent did Ann not respond to John's behaviour? showed significant differences, F (1, 99) = 52.93, p < .001, ηp 2 = . 348, modulated by the factor Type of confrontation. Thus, more participants in the No-confrontation condition indicated that Ann did not respond to John's behaviour ( M = 20.7) than subjects in the Confrontation condition ( M = 5.05). In short, the experimental manipulations were effective.

Effects of the Type of Sexual Harassment, Victim Response, and Ideological Variables on the Perception of Sexual Harassment, and the Predisposition to Commit Harassment

To test the first aims of this study, i.e., how participants perceived the episode, their predisposition to commit harassment according to the type of harassment and victim response (confrontation or not), and the influence of ideological variables, two analysis of covariance were performed using the ideological measures Hostile Sexism (HS), Benevolent Sexism (BS), and myths of sexual harassment (total ISHMA score) as covariates and the items of perception of harassment, and predisposition to commit harassment as dependent variables.

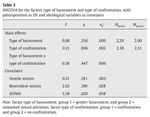

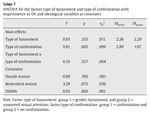

The first step was to conduct an ANCOVA (see Table 2) with a full 2 (Type of harassment: Gender harassment vs. Unwanted sexual attention) x 2 (Type of confrontation: Confrontation vs. No confrontation) factorial design and the ideological measures of HS, BS, and the ISHMA (total score) as covariates for the item Personally, do you think John's behaviour constitutes sexual harassment? . The results showed a main effect for the factor Type of harassment. Thus, fewer participants in the Gender harassment condition indicated John's behaviour constituted sexual harassment than subjects in the Unwanted sexual attention condition. No significant effect was found for the factor Type of confrontation and no interaction was observed between the factors Type of harassment and Type of confrontation (see Table 2). Similarly, the covariates were not significant.

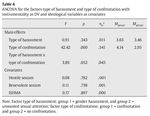

The same experimental design was employed for the predisposition to commit sexual harassment (see Table 3). The results showed no controlling effects (covariate) of myths on sexual harassment (ISHMA), no significant effect of the factors Type of harassment and Type of confrontation, nor an interaction between both factors.

Effects of the Sexual Harassment, Victim Response, and Ideological Variables on the Evaluation of Women

In order to assess how participants evaluated women according to the type of harassment, victim response, and the influence of ideological variables, several analysis of covariance were performed using the ideological measures of HS, BS, and ISHMA as covariates, and the items on the evaluation of women as dependent variables.

To analyse the perception of instrumentality (as a measure of the evaluation of women), an ANCOVA with a full 2 (Type of harassment: Gender harassment vs. Unwanted sexual attention) x 2 (Type of confrontation: Confrontation vs. No confrontation) factorial design was conducted with the ideological measures (i.e., HS, BS and ISHMA) as covariates. The results (see Table 4) showed a main effect for the factor Type of confrontation. Thus, participants in the Confrontation condition attributed more instrumental traits to Ann than subjects in the No confrontation condition. No effect was observed for the factor Type of harassment, interaction (between factors Type of harassment and Type of confrontation), nor for the covariates (see Table 4).

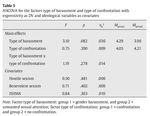

The use of the same full factorial design on the measure of expressivity revealed no significant effect for the factors, the interaction, or the covariates (see Table 5).

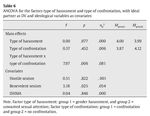

As for the evaluation of women with the item To what extent does Ann fit the image of your ideal partner? , the same experimental design revealed no significant effect controlling the (covariate) effects of Benevolent Sexism (BS), the factors Type of harassment and Type of confrontation, but an effect was observed for the interaction Type of harassment x Type of confrontation (see Table 6). Succinctly, women who did not confront gender harassment ( M = 4.59) fitted best the image of the ideal partner than victims who confronted gender harassment ( M = 3.41). In contrast, women who did not confront Unwanted sexual attention fitted less the image of the ideal partner ( M = 3.65) than victims who confronted such behaviour ( M = 4.34).

As for the evaluation of women with the item, I think Ann is an impertinent person , the results showed a significant effect for the factor Type of confrontation (see Table 7). Thus, more participants in the Confrontation condition indicated that Ann was an impertinent person than subjects in the No confrontation condition (regardless of the type of harassment). Moreover, no main effect was found for the factor Type of harassment, the interaction between both factors, or the covariates.

Influence of Ideological Variables on the Perception of Harassment, the Predisposition to Commit Harassment, and the Evaluation of Women

To verify the results that underscore the impact of ideology and myths on sexual harassment (see Table 1), the correlations between the different dependent and ideological measures were analysed. The results show that low perception of harassment was related to high Hostile ( r = -.33, p < .01) and Benevolent sexist ideology ( r = -.29, p < .01), as well as greater acceptance of myths of sexual harassment ( r = -.32, p < .01). A higher predisposition to commit harassment was related to high HS ( r = .27, p < .01) and myth acceptance ( r = .34, p < .01). High BS scores were related to women being considered less of an ideal partner ( r = -.24, p < .05) and more as impertinent ( r = .23, p < .05).

These results underscored the role of ideological variables on the perception of behaviours associated to sexual harassment, thus additional analysis were undertaken to test further the results.

The Role of ISHMA as a Mediator

Bearing in mind the relationship between Ambivalent Sexism and myths of sexual harassment, and the possible relationship with the main measures under assessment, i.e., perception of sexual harassment and predisposition to commit harassment, mediational analysis was performed to determine if acceptance of myths mediated the relationship between these variables.

Prior to undertaking mediational analysis, the requisite of covariance between the independent variable and the potential mediator was tested (Baron & Kenny, 1986). The results showed a significant relationship between BS (independent variable) and ISHMA (mediator), β = .49, p < . 001, and between BS (independent variable) and perception of harassment (dependent variable), β = -.29, p < . 01. Consequently, the role of ISHMA as a mediator of the relationship between BS and the perception of harassment was assessed. In the third equation the independent variable (IV) and the mediator were introduced as predictors. For there to be mediation, the mediator (ISHMA) must affect the dependent variable (DV); this condition was met, β = -.31, p < . 01. The final step of mediation analysis was to compare the effect of the IV on the DV in equations 2 and 3; the effect should be lower in 3 than in 2. Perfect mediation would occur if the IV had no effect when the mediator was controlled. Mediation was perfect in this study given that the relationship between the BS variable and the perception of harassment fell from -.29 to -.17, and the relationship ceased to be significant, Sobel test = -1.92, p < .05.

Thus, participants with benevolent sexists beliefs tended not to perceive behaviour as harassment (see Figure 1), which was due to the acceptance of myths of sexual harassment.

Figure 1 . Effect of BS on perception of harassment mediated by ISHMA.

In a second mediational analysis where HS was taken as the independent variable and ISHMA as the potential mediator, a covariance, β = .79, p < . 001, was observed for the independent variable HS with the dependent variable, predisposition, β = .26, p < . 01. In the third equation the IV and the mediator were introduced as predictors. For there to be mediation, the mediator (ISHMA) should affect the DV, a condition which was met, β = .34, p < . 01. The final step of mediation analysis involved comparing the effect of the IV on the DV in equations 2 and 3. The effect should be lower in 3 than in 2. Mediation was perfect if the IV had no effect when the mediator was controlled. Mediation was perfect given that the relationship between the HS variable and Predisposition fell from .26 to -.04, and the relationship ceased to be significant, Sobel test = 2.35, p < .01.

Thus, participants scoring high on HS were more predisposed to commit harassment (see Figure 2), which was partly due to the acceptance of myths of sexual harassment.

Figure 2 . Effect of HS on predisposition mediated by ISHMA.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess how men react to different victim responses to sexual harassment. The initial hypothesis was that the type of harassment, victim response (confrontation), and ideology would determine the reaction of men.

In terms of the typology of sexual harassment, one is inclined to ask why men react to confrontation differently according to the type of sexual harassment. Several studies have found subtle forms of sexual harassment were not perceived as discriminatory acts, particularly by men (Baker et al., 1990; Jones & Remland, 1992; Saunders & Senn, 2009). Overall, the results of this study revealed that perception of harassment was lower for Gender harassment than for Unwanted sexual attention. As gender harassment was not perceived to be harassment, or at least it was perceived to a lesser extent than Unwanted sexual attention, this type of behaviour may become normalized, which consequently raises the threat of women being exposed to harassment.

The results show that victims who confronted harassment were negatively evaluated by harassers (both in personal terms and at work), i.e., women who confronted sexual harassment were attributed more instrumental traits. As previously mentioned, the West embraces the idea that women are competent, yet attitudes towards women were not as positive as one would initially expect, i.e., they were chastised for not being feminine enough.

The women who best fitted the image of an ideal partner were those that did not confront gender harassment. In all likelihood this was because gender harassment, being more subtle and disguised, was not perceived as harassment, which in turn led men to interpret women had exaggerated their reactions. In contrast, women who did not confront Unwanted sexual attention fitted even less men's image of the ideal partner since this type of harassment was more evident. As for women who confronted harassment, they were perceived as impertinent, probably because they challenged traditional patriarchal roles.

The results of this study corroborated that there is no reliable or efficacious way of combating sexual harassment. Strategies of the type "ignore or avoid the harasser", fail to deter harassment, yet they are the coping strategies most frequently used by victims (Fitzgerald et al., 1995; Swim & Hyers, 1999). Thus, the results of this study substantiated the findings of other studies asserting that all coping strategies have certain shortcomings that may pose obstacles to victims.

Moreover, the results have underscored the crucial role of ideological variables on the perception of behaviours associated to harassment and the significant influence of the variable Myths of sexual harassment. The data obtained in this study has underscored the significant influence of myths on perception, and thus on the evaluation of the events, which in turn may further heighten the perpetrator's predisposition to commit sexual harassment.

Other ideological variables influencing the perception of certain behaviours as harassment were Hostile and Benevolent Sexism, the latter being the most insidious as it surreptitiously upholds that "good women" should know their place, refrain from complaining, and respect traditional roles.

The results of this study have implications for prevention and/or education programs on sexual harassment in underscoring the need for raising men's awareness and sensitivity to improve their understanding of the construct. Thus, if harassment is confronted, and men are able to perceive the behaviour as such, they will be able to respond more effectively (Saunders & Seen, 2009).

Moreover, the findings of this study can serve to inform evidence-based decision-making for drafting and implementing social policy aimed at combatting sexual harassment and other types of violence against women. From all quarters of modern society, victims are encouraged to report every offence, yet when they attempt to do so they are overwhelmed by a barrage of obstacles with negative repercussions and outcomes. Thus, several studies have underscored the need for interventions designed to raise sensitivity towards harassment and its negative consequences by developing effective strategies and tools to enable both victims and perpetrators to identify behaviour as harassment in order to prevent negative reactions.

Limitations

The reaction of men when confronted to different types of sexual harassment was assessed using a story and questionnaires. Though the literature on the usefulness of these types of studies is extensive, they nonetheless entail certain limitations. Due to the impossibility of recreating real-life situations, the participants in this study may have failed to fully evaluate and react as they would in real life.

Bearing in mind the limitations of this study, the results shed some light on the understanding of how men react to victims of harassment when they challenge such behaviour and in understanding some of the main obstacles hindering women from reporting harassment.

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

Financial Support

This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness with the R&D project "Sexist ideology and power inequality in the development and maintenance of Sexual Harassment" (PSI2011-29720), by Grant SEJ-6225 "Psychosocial analysis of legitimacy and prejudice in the maintenance of asymmetrical social relationships" from the Andalusian Regional Govemment, and by a Grant from the FPU (AP2009-2940) Program of the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport given to the second author.

Manuscript received: 30/07/2013

Revision received: 02/11/2013

Accepted: 06/11/2013

*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to M. Carmen Herrera.

Departamento de PsicologĂa Social. Universidad de Granada.

Campus de Cartuja. 18071 Granada. Spain.

Email: mcherrer@ugr.es

h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; /dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpal.2014.06.006

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perception of a stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84 , 111-125. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ;dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F%2F0022-3514.84.1.111

AmnistĂa Internacional (2011). Datos sobre la violencia contra las mujeres y las niñas en el mundo [Data about violence against women and girls in the world]. Retrieved from h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; w w w & # 4 6 ; e s & #46;amnesty.org/temas/mujeres/violencia-contra-las-mujeres/ magnitud-cifras-y-datos/

Baker, D. D., Terpstra, D. E., & Larntz, K. (1990). The influence of individual characteristics and severity of harassing behaviour on reactions to sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 23, 305-325. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF00288336

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 , 1173-1182. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & #47;/dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bergman, M. E., Langhout, R. D., Palmieri, P. A., Cortina, L. M., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2002). The (un)reasonableness of reporting: antecedents and consequences of reporting sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 230-242. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; /dx.doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.2.230

Cunningham, G. B., & Benavides-Espinoza, C. (2008). A trend analysis of sexual harassment claims: 1992-2006. Psychological Reports, 103, 779-782. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & #47;/dx.doi.org/10.2466%2FPR0.103.7.779-782

ExpĂłsito, F. (1995). Factores psicosociales en las relaciones igualitarias: IdeologĂa y realidad en el fenĂłmeno de la soledad . [Psychosocial factors in egalitarian relationships: Ideology and reality in the phenomenon of loneliness] (Doctoral thesis). University of Granada. Granada. Spain. Retrieved from h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; d igibug.ugr.es/bits-tream/10481/14491/1/2288.pdf

ExpĂłsito, F., Moya, M., & Glick, P. (1998). Sexismo ambivalente: MediciĂłn y correlatos [Ambivalent sexism: Measurement and correlates]. Revista de PsicologĂa Social, 13 , 159-170. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1174%2F021347498760350641

ExpĂłsito, F., & Moya, M. (2005). Violencia de gĂ©nero [Violence against women]. In F. ExpĂłsito & M. Moya (Eds.), Aplicando la psicologĂa social (pp. 201-227). Madrid, Spain: Pirámide.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878-902. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ;dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F%2F0022-3514.82.6.878

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 578-589. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; p s y cnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.578

Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., & Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 425-445. doi: h t t p ://dx.doi.org/10.1207%2Fs15324834basp1704_2

Fitzgerald, L. F., Shullman, S. L., Bailey, N., Richards, M., Swecker, J., Gold, Y., ... & Weitzman, L. (1988). The incidence and dimensions of sexual harassment in academia and the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32, 152-175. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ;/dx.doi.org/10.1016%2F0001-8791%2888%2990012-7

Gelfand, M., Fitzgerald, L., & Drasgow, F. (1995). The structure of sexual harassment: A confirmatory analysis across cultures and settings. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 47, 164-177. doi: h t t p://dx.doi.org/10.1006%2Fjvbe.1995.1033

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 , 491-512. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; /dx.doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.70.3.491

Gutek, B. (1985). Sex and the workplace. Impact of sexual behaviour and harassment on women, men, and organisation: San Francisco, CA: Jossey- Bass.

Herrera, M. C., ExpĂłsito, F., & Moya, M. (2012). Negative reactions of men to the loss of power in gender relations: Lilith vs. Eve. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 4 , 17-42.

Hotelling, K., & Zuber, B. A. (1997). Feminist issues in sexual harassment. In W. O'Donohue (Ed.), Sexual harassment: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 99-108). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Instituto de la Mujer. (2009). Violencia sexual y tráfico de seres humanos [Sexual violence and trafficking of human beings]. Retrieved from h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; w w w.inmujer.es/estadisticas/consulta.do?metodo=buscar

Jones, T. S., & Remland, M. S. (1992). Sources of variability in perceptions of and responses to sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 27, 121-142. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2FBF00290013

Leidig, M. K. W. (1981). Violence against women: A feminist psychological analysis. In S. Cox (Ed.), Female psychology (2nd ed.). New York, NY: St. Martin's.

Lonsway, K. A., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Sexual harassment mythology: Definition, conceptualization, and measurement. Sex Roles, 58, 599-615. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11199-007-9367-1

Pina, A., Gannon, T. A., & Saunders, B. (2009). An overview of the literature on sexual harassment: Perpetrator, theory, and treatment issues. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 14, 126-138. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; /dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.avb.2009.01.002

Pryor, J. B. (1995). The phenomenology of sexual harassment: Why does sexual behaviour bother people in the workplace? Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 47 , 160-168. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ;dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F%2F1061-4087.47.3.160

Quinn, B. A. (2002). Sexual harassment and masculinity: The power and meaning of ''girl watching". Gender & Society, 16, 386-402. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F0891243202016003007

Rudman, L. A. W., & Glick, P. (1999). Feminized management and backlash toward agentic women: The hidden cost to women of a kinder, gender image of middle-managers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1004-1010.

Rudman, L., & Glick, P. (2008). The social psychology of gender . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., & Glick, P. (2003). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward women who engage in premarital sex in Turkey. The Journal of Sex Research, 40, 296-302. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552194

Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., Yalçin, Z. P., & Glick, P. (2007). Ambivalent sexism, belief in a just world, and empathy as predictors of Turkish students' attitudes toward rape victims. Sex Roles, 57, 889-895. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11199-007-9313-2

Saunders, K. A., & Senn, C. Y. (2009). Should I confront him? Men's reactions to hypothetical confrontations of peer sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 61, 399-415. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs11199-009-9638-0

Swim, J. K., & Hyers, L. L. (1999). Excuse me—What did you just say?!: Women's public and private responses to sexist remarks. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35 , 68-88. doi: h t t p://dx.doi.org/10.1006%2Fjesp.1998.1370

Topa, G., Morales, J. F., & Depolo, M. (2008). Perceived sexual harassment at work: Meta analysis and structural model of antecedents and consequences. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 11 , 207-218.

Walker, W. D., Rowe, R. C., & Quinsey, V. L. (1993). Authoritarianism and sexual aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1036-1045. doi: h t t p & # 5 8 ; & # 4 7 ; & # 4 7 ; dx.doi.org/10.1037%2F%2F0022-3514.65.5.1036

Copyright © 2024. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

CrossRef

CrossRef