The Effect of Fiction on the Well-Being of Older Adults: A Longitudinal RCT Intervention Study Using Audiobooks

[La influencia de la ficciĂłn en el bienestar de los adultos mayores: un estudio de intervenciĂłn longitudinal de ensayo controlado aleatorizado mediante audiolibros]

Giulia Poerio1,a and Peter Totterdell2,a

1University of Essex, UK; 2University of Sheffield, UK

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a16

Received 14 November 2018, Accepted 10 July 2019

Abstract

Research has examined the psychological benefits of fiction, particularly for socio-cognitive and interpersonal processes, but has yet to examine whether it can have an impact on individuals’ personal well-being in a natural setting over time. A longitudinal randomized control trial (RCT) using audiobooks was conducted to compare the effects of fiction (novels, short stories) and non-fiction on the well-being (subjective, eudaimonic, social) of 94 older adults from diverse urbancommunities over a six-week period. Participants chose one of four books in the condition to which they were allocated. The participants in the fiction, compared to non-fiction, conditions did not show greater improvements in any aspect ofwell-being over the study period. However, regression analysis controlling for initial levels of well-being showed that individuals who reported greater absorption in, and appreciation of, their audiobook showed greater subsequent wellbeing, particularly meaning in life, that extended beyond book completion. The findings indicate that an audiobook can have a positive enduring impact on various aspects of older adults’ well-being, but it depends on them having a personalengagement with its content, and not on its designation as fiction or non-fiction.

Resumen

Se han estudiado los beneficios psicológicos de la ficción, particularmente en procesos cognitivos e interpersonales, pero aún se desconoce si la ficción puede causar impacto en el bienestar en un entorno natural a largo plazo. El presente estudio utilizó un ensayo controlado aleatorizado longitudinal mediante audiolibros comparando los efectos de la ficción (novelas, cuentos) y de la no ficción sobre el bienestar (subjetivo, eudaimónico, social) de 94 adultos mayores de distintas comunidades urbanas durante un periodo de seis semanas. Los participantes escogieron uno de cuatro libros en la condición a la que fueron asignados. Los participantes de la condición de ficción, comparados con los de la no-ficción, no mostraron mejoras significativas en ningún aspecto del bienestar durante el periodo de estudio. Sin embargo, un análisis de regresión controlando los niveles iniciales de bienestar mostró que los sujetos que refirieron una mayor absorción y valoración del audiolibro también manifestaron un mayor bienestar posintervención, sobre todo en el sentido de la vida, que se extendió hasta después de la finalización del libro. Los resultados indican que un audiolibro puede tener un impacto positivo duradero en varios aspectos del bienestar de los adultos mayores, si bien depende de que estos se involucren personalmente con el contenido, independientemente de que el audiolibro sea ficción o no ficción.

Keywords

Fiction, Well-being, Meaning, Absorption, BibliotherapyPalabras clave

FicciĂłn, Bienestar, Sentido, AbsorciĂłn, BiblioterapiaCite this article as: Poerio, G. & Totterdell, P. (2020). The Effect of Fiction on the Well-Being of Older Adults: A Longitudinal RCT Intervention Study Using Audiobooks. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(1), 29 - 38. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a16

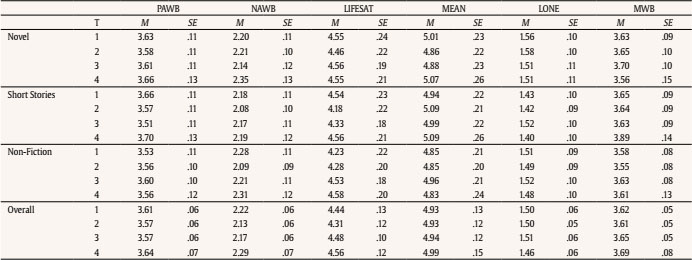

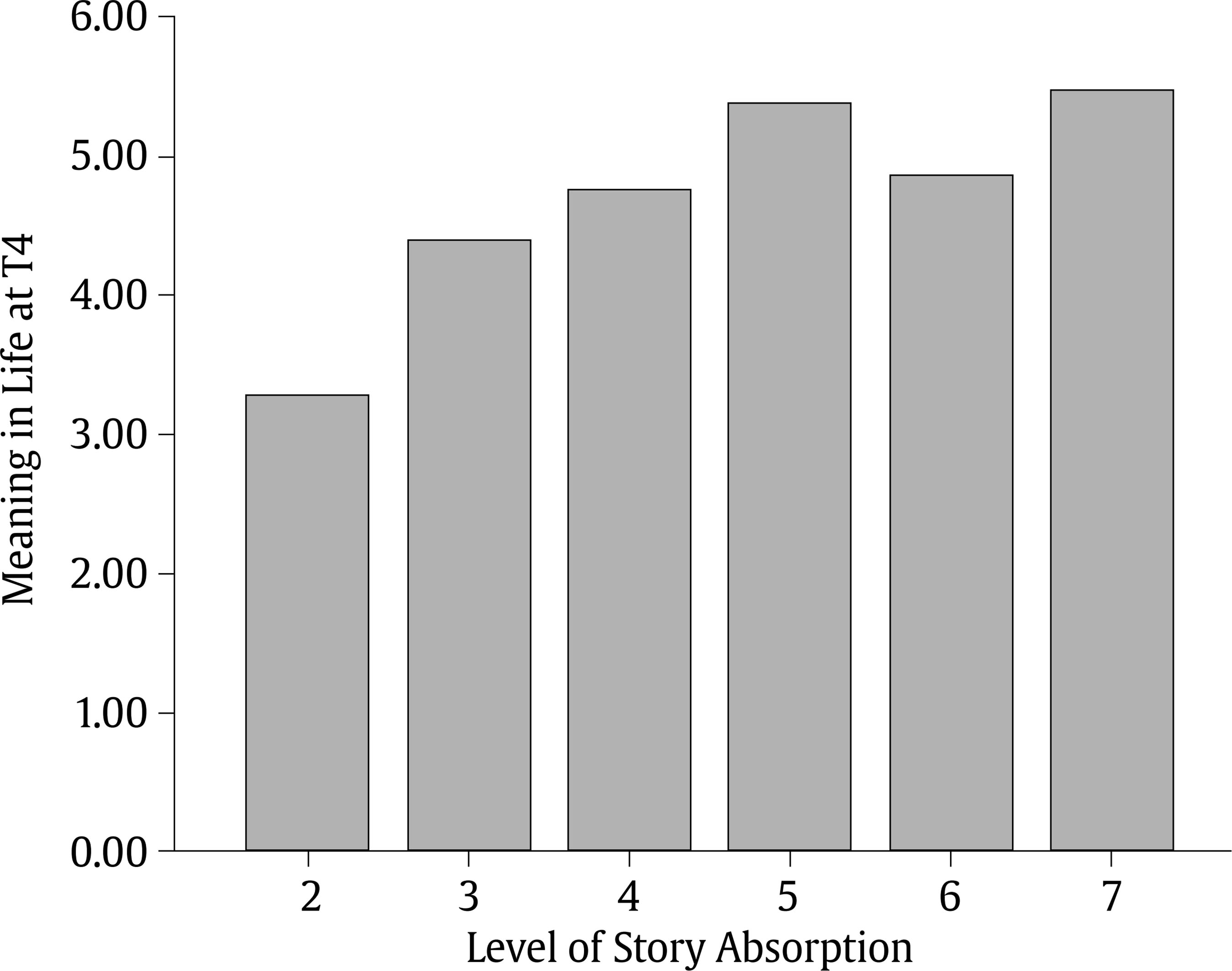

totterdell@sheffield.ac.uk Correspondence: p.totterdell@sheffield.ac.uk (P. Totterdell).“A novel takes you somewhere and asks you to look through the eyes of another person, to live another life.” (Barbara Kingsolver, 2010). Fiction allows people to enter simulated worlds created from an author’s imagination and, by doing so, is proposed to have benefits for cognition and emotion (Koopman & Hakemulder, 2015; Mar & Oatley, 2008; Oatley, 2016). A growing body of research has examined the psychological benefits of fiction, particularly for socio-cognitive and interpersonal processes, but has yet to examine whether it can have an impact on individuals’ personal well-being in a natural setting over time. Lifetime exposure to fiction has been associated with greater empathetic understanding (Koopman, 2015a; Mar, Oatley, & Peterson, 2009) and performance on theory of mind tasks (Djikic, Oatley, & Moldoveanu, 2013; Mar, Oatley, Hirsh, dela Paz, & Peterson, 2006; Mar et al., 2009; Mar, Tackett, & Moore, 2010). Conversely, lifetime exposure to non-fiction has been associated with poorer theory of mind (Mar et al., 2006) and greater loneliness (Mar et al., 2009). Experimental studies have shown that reading short extracts of literary fiction enhances theory of mind when compared to non-fiction and genre fiction (Black & Barnes, 2015; Kidd & Castano, 2013; Kidd & Castano, 2017; Van Kuijk, Verkoeijen, Dijkstra, & Zwaan, 2018), although some studies have failed to replicate this effect (Panero et al., 2016; Samur, Tops, & Koole, 2018). Reading fiction has also been linked with improved attitudes towards stigmatized groups (Johnson, 2013; Kaufmann & Libby, 2012; Vezzali, Hewstone, Capozza, Giovannini, & Wölfer, 2014), increased pro-social behaviour (Johnson, 2012; Koopman, 2015a), a greater perceived ability to learn about the self and others, (Moyer, 2007), and enhanced understanding of one’s own and others’ ethnic identity (Vasquez, 2005). Research shows that exposure to fiction is associated with social ability and that reading fiction can have immediate benefits for interpersonal processes, but does fiction also have an enduring impact on individuals’ personal well-being? The idea that reading can act as a tonic for mental and physical ailments has a long history dating back to the middle ages (Jack & Ronan, 2008). ‘Bibliotherapy’ – a term coined by Samuel Crothers (1916) – involves the use of both fiction and non-fictional materials for therapeutic benefit. Bibliotherapy using fiction is thought to alleviate mental distress through readers’ identification with characters and events in narratives which facilitates new perspectives on problems and meaning-making and provides comfort through shared humanity (Cohen, 1993; Shrodes, 1950). Although early applications of bibliotherapy extol the benefits of fiction, since the 1980s approaches have focused predominately on non-fiction, typically in the form of self-help literature (Riordan & Wilson, 1989). Whilst the effectiveness of non-fiction for therapeutic outcomes using randomized controlled trials has been well documented and researched (e.g., for emotional disorders, Den Boer, Wiersma, & Van den Bosch, 2004), the benefits of reading fiction for well-being have yet to be systematically investigated in a controlled design. Although research has yet to experimentally determine the effect of reading fiction on well-being in an applied setting, reading for pleasure (which can include non-fiction) has been associated with benefits for health and well-being. Those who read for pleasure report lower levels of stress and depression, higher levels of life satisfaction, self-esteem, and the ability to cope with difficult situations, as well as increased feelings of social connection (Billington, 2015). Older adults’ reading for pleasure appears to be associated with lower levels of loneliness, comparable to social activities such as taking trips and playing games (Rane-Szostak & Herth, 1995). Perhaps most strikingly, a recent report based on a large-scale dataset suggested that readers benefited from a 20% reduction in mortality compared to non-readers (Bavishi, Slade, & Levy, 2016). The salubrious effect of reading appeared to be driven by reading books rather than magazines/newspapers and remained when controlling for factors such as education. Although the authors suggested that their book readers were most likely to be fiction readers, it remains unclear whether the benefits of reading resulted from reading fiction, non-fiction, or a combination of the two. In the present study, our primary aim was to test whether fiction, compared to non-fiction (as an active control condition), confers benefits to well-being over time in a natural setting, using a longitudinal randomized controlled trial (RCT) intervention design. We were interested in examining the impact of a long extract of fiction (e.g., a novel or a collection of short stories) rather than the effect of a single short extract. This is important not only because it more accurately reflects how fiction is consumed in naturalistic settings, but also because a single short dose of fiction is probably insufficient for lasting benefits (e.g., mentalizing; Samur et al., 2018). Our primary objective was to compare the effect of fiction versus non-fiction on core dimensions of well-being, including subjective well-being (life satisfaction and the experience of positive and negative emotions), eudaimonic well-being (presence of meaning in life), and social well-being (absence of loneliness). Well-being was assessed not only during the period in which the fiction was presented (4 weeks) but also 2 weeks after the intervention to explore whether any effects of fiction were maintained over time. We chose to present fiction in one of two forms: a novel or a short story collection. Individual short stories are comparable in duration to stimuli typically used in experimental studies on fiction, but compiled as a collection, they are comparable to novels in overall length. Finding a difference between novels and short-story collections would indicate that the duration (or length) of a story’s narrative is a relevant factor for determining the impact of fiction on well-being. We also chose to present our reading intervention in the form of audiobooks to encourage participation from individuals who may not typically read books and to address potential differences in reading fluency between participants. Using audiobooks also extends previous research on fiction which has focused on reading it but not listening to it. The impact of listening to fiction is of practical interest partly because audiobooks are a popular format for consuming fiction but also because listening to storytellers is a longstanding tradition in most cultures. A secondary aim of our study was to examine whether the relationship between literature and well-being is dependent on engagement with its content (regardless of its categorization into fiction or non-fiction). We therefore examined what effects people’s absorption with the literature and their appreciation of it had on their well-being. Factors such as emotional engagement and transportation (absorption) are argued to be key to the beneficial socio-emotional effects of fiction (Djikic et al., 2013; Johnson, 2012, 2013; Oatley, 2016). Previous research shows that transportation into a story encourages beliefs that are consistent with the story (Green & Brock, 2000) and facilitates narrative persuasion (Appel & Richter, 2010). Similarly, experience taking – the imaginative process of assuming the identity of a character – is associated with producing changes in beliefs (Kaufmann & Libby, 2012). Empathy is also higher when readers become emotionally involved in a story (Bal & Veltkamp, 2013; Koopman 2015a). With respect to well-being, emotional responses affect the choice, experience, and consequences of fiction (Mar et al., 2009). For example, complex emotional responses such as feeling moved can motivate meaning-making processes and explain the perhaps counterintuitive occurrence of reading sad or distressing novels for pleasure (Koopman, 2015b). We chose to conduct the intervention with older adults (50+) from local communities in a UK city. For older adults, reading or listening to a book has the potential to be an eminently suitable intervention for well-being because it is an activity that does not depend on physical function or social contacts (both of which are likely to decline with age) and is relatively inexpensive or free if library services are available. Library services in the city concerned had identified more deprived areas as a priority for developing children’s engagement with books as part of a public health well-being initiative. These areas were therefore also targeted in the present study because of the potential links between adults’ and children’s use of library services. Participants A sample size of 90 was determined a priori with G*power3 to give sufficient power (.80) to detect small-to-medium effect sizes (p < .05) for three groups at four time-points. Ninety-four volunteers were recruited to the study – described as an investigation into reading and well-being – via email adverts, posters/flyers, visits to community groups (e.g., lunch clubs and libraries), adverts in community magazines and online forums, and referrals. Participants were provided with a shopping voucher (GBP 10) in exchange for their participation. The sample had a mean age of 64.76 years (SD = 8.41, range = 50-84), 85% were female, and 95% were white. The majority (52%) of the sample were retired, and the remainder consisted of full-time workers (14%), part-time workers (11%), volunteers (7%), occasional/casual workers (5%), self-employed (5%), unemployed (2%), homemakers (2%), and students (1%). Sixty-seven percent of participants had an annual household income below the UK median (GBP 35,200), 26% had an annual income above this amount and 7% declined to answer. Index of multiple deprivation (IMD) scores for participants were calculated using their postal codes (M = 20.69, SD = 17.50, range = 2.47-75.23). IMD is the measure of deprivation used nationally to rank small areas in England (M = 21.54) and combines information from seven domains of deprivation (income, employment, health, education, housing, environment, crime) where higher scores represent higher levels of relative deprivation in that area. Participants were asked about their reading habits for fiction and non-fiction. The majority of participants (56%) reported reading fiction every day or almost every day, 15% reported reading fiction once or twice a week, 9% once or twice a month, 13% a few times a year, and 7% never or almost never read fiction. Non-fiction reading was less frequent: 12% reported reading non-fiction every day or almost every day, 16% once or twice a week, 20% once or twice a month, 36% a few times a year, and 16% never or almost never read non-fiction. Participants were asked three questions from the Booktrust Reading Habits Survey (Gleed, 2013) to assess attitudes towards reading (e.g., “I find reading boring”), rated on 7-point scales from 1(strongly disagree) to 7(strongly agree). These were reverse scored and averaged to create an overall score for positive attitudes towards reading (α = .74). On average, participants had a positive attitude towards reading (M = 6.38, SD = .96). Procedure We preregistered the design of our longitudinal RCT intervention online at https://aspredicted.org/fh2kz.pdf. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the authors’ university ethics committee and informed consent was obtained from participants at the start of the study. Participants attended an induction session during which they chose their audiobook and were provided with materials and instructions for the study. Participants were randomly allocated to one of three conditions (novel, short stories, and non-fiction) using block randomization. The non-fiction condition formed the active control group. Participants selected one audiobook from a choice of four within their allocated category. They were provided with a description of each audiobook and a five-minute audiobook sample to listen to. After making their selection, participants completed a baseline questionnaire (T1) assessing their well-being over the previous two weeks (scales described below). Participants were provided with an MP3 player with instructions and a listening guide for their audiobook. They were asked to listen to approximately half of their selected audiobook in the first two weeks of the study and the remainder in the second two weeks of the study. Participants were provided with additional questionnaire booklets to complete every two weeks over the following six weeks (at T2, T3, and T4) with stamped addressed envelopes for their return. T2 and T3 questionnaires covered the first and second two weeks of audiobook listening respectively, and T4 covered the two weeks that followed completion of the audiobook. All questionnaires included well-being measures regarding the previous two weeks. Questionnaires at T2 and T3 also included measures regarding absorption in the audiobook, and at T3 participants were asked about their overall appreciation of their audiobook. The wording of measures was adapted to refer to the time period or focus of interest where needed but otherwise the original wording was used. The research team was in regular contact with participants and sent them reminders (e.g., via email or phone) regarding questionnaire completion. Materials There were four audiobooks in each category (novel, short story collection, non-fiction) from which participants chose one. This enabled the researchers to curate a set of books that had literary quality but also encouraged engagement with the book by enabling participants to choose one that held appeal to them. To ensure literary quality, the books were chosen from award-winning books/authors with an equal balance of female/male and UK/non-UK authors. Non-fiction books were chosen to cover a range of topics: history, nature, medicine, and science. Selections were roughly equivalent in length (audiobook time) and difficulty. Reading difficulty was indexed by the Flesch Reading Ease test (Flesch, 1948) calculated from the first 700 words of each book. This score rates text on a 100-point scale (with higher scores indicating easier reading) calculated using the following formula: 206.835 – (1.015 x ASL) – (84.6 x ASW) where ASL = average sentence length (the number of words divided by the number of sentences) and ASW = average number of syllables per word (the number of syllables divided by the number of words). We ensured that all books had good ratings on Amazon and Audible (UK) and GoodReads (all ratings are out of 5). Our selected books and criteria as well as how many copies of each book were selected by participants are shown in Table 1. Measures Affective well-being. The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE. Diener et al., 2010) measures positive and negative affective well-being. Participants were asked to think about what they had been doing and experiencing in the past two weeks and indicated how much they experienced each of 12 feelings (six positive feelings such as “happy” and “contented”; six negative feelings such as “sad” and “angry”). Responses were made on a 5-point scale from 1 (very rarely or never) to 5 (very often or always). Positive items and negative items were averaged to create two subscales where higher scores indicate greater positive and negative affective well-being respectively (SPANE-P: T1α = .92, T2α = .92, T3α = .94, T4α = .93; SPANE-N: T1α = .87, T2α = .87, T3α = .90, T4α = .88). Life satisfaction. Life satisfaction was measured using the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985) which was adapted to refer to the past two weeks (e.g., “Recently, the conditions of my life have been excellent”, “If I could re-live the past two weeks, I would change almost nothing”). Participants rated their agreement with each item on a 7-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items were averaged to provide an overall score where higher values indicate greater satisfaction with life over the past two weeks (T1α = .94, T2α = .92, T3α = .92, T4α = .93). Meaning in life. Meaning in life was measured using the presence of the meaning subscale of the Meaning in Life Scale (Steger, Frazier, Oishi, Kaler, & Mallinckrodt , 2006). This 5-item measure was adapted to refer to the past two weeks (e.g., “Recently, my life has had a clear sense of purpose”, “Recently, I have had a good sense of what makes my life meaningful”). Participants rated each item on a 7-point scale from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 7 (absolutely true). The negatively worded item was reverse coded and averaged with the other items to create an overall score where higher values indicate greater presence of meaning in life over the past two weeks (T1α = .89, T2α = .90, T3α = .92, T4α = .94). Loneliness. The 3-item Loneliness Scale (Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2004) measured loneliness over the past two weeks. Participants indicated how often they had felt “left-out”, “isolated from others”, and “that [they] lacked companionship” on 3-point scales from 1 (hardly ever) to 3 (often). Items were averaged to create an overall score such that higher values indicated greater levels of loneliness over the past two weeks (T1α = .77, T2α = .86, T3α = .86, T4α = .85). Mental well-being. The Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being scale (SWEMWBS. Stewart-Brown et al., 2009) was adapted to provide an overall indication of general mental well-being over the past two weeks. Participants read each of the seven statements about feelings and thoughts and chose the response that best described their experience over the past two weeks on a 5-point scale from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Example items include: “Recently, I’ve been feeling optimistic about the future”, “Recently, I’ve been dealing with problems well”, “Recently, I’ve been feeling close to other people”. Items were averaged to provide an overall score where higher values indicated greater mental well-being over the past two weeks (T1α = .80, T2α = .88, T3α = .90, T4α = .55). Table 2 Means and Standard Errors for Well-being at each Time Point Overall and for Each Condition   Note. PAWB = positive affective well-being; NAWB = negative affective well-being; LIFESAT = satisfaction with life; MEAN = meaning in life; LONE = loneliness, MWB = mental well-being. Means are adjusted for covariates (income and negative life events). Absorption in audiobook. We used 12 items adapted from the Story World Absorption Scale (Kuijpers, Hakemulder, Tan, & Doicaru, 2014) to measure experiences while listening to the audiobook. To reduce the demand on participants, three items were selected from each of the scale’s four sub-scales: (1) absorption (e.g., “I felt absorbed in the content of the book”), (2) transportation (e.g., “When listening, it sometimes seemed as if I were in the world of the book”), (3) emotional engagement (e.g., “I felt connected to the events and people described in the book”), and (4) mental imagery (e.g., “When listening, I could see situations in the book being played out before my eyes”). Responses were made on 7-point scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items were averaged to create an overall score such that higher scores indicated greater absorption in the audiobook (T2α = .91, T3α = .95). Appreciation of audiobook. Participants provided their overall evaluations of the book on completing it (i.e., at T3 only). Hedonic and eudaimonic outcomes were measured using nine items adapted from Oliver and Bartsch’s (2010) scale. Hedonic outcomes were measured with three items (e.g., “It was fun for me to listen to this book”); eudaimonic outcomes were measured with two subscales each consisting of three items: “moving/thought provoking” (e.g., “The book was thought provoking”); “lasting impression” (e.g., “This book will stick with me for a long time”). Responses to each item were made on 7-point scales from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items were averaged to create an overall score such that higher scores reflected greater appreciation of the audiobook (T3α = .94). Negative life events. We used a single item to provide an index of negative life events over the past two weeks (“Over the past two weeks, to what extent have you been affected by negative events in your life?”) which was answered from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). This measure was included as a potential control variable. Data Checks and Control Variables To check whether there were any pre-existing differences in well-being at baseline (T1), we conducted a series of 1-way between-subjects analysis of variance with each well-being variable as our dependent variable and condition (novel, short stories, non-fiction) as the independent variable. There were no significant main effects of condition on any of the well-being variables indicating no meaningful pre-existing differences in well-being between participant groups at the start of the intervention: positive affective well-being: F(2, 91) = .39, p = .681, η2p = .008; negative affective well-being: F(2, 91) = 1.33, p = .269, η2p = .028; life satisfaction: F(2, 88) = 0.87, p = .421, η2p = .019; meaning in life: F(2, 89) = 0.22, p = .806, η2p = .005; loneliness: F(2, 90) = 2.41, p = .096, η2p = .051; mental well-being: F(2, 90) = 1.18, p = .312, η2p = .026. We examined correlations between our well-being variables at each time point and the following potential control variables: age, gender, income, and negative events (averaged T1-T4). Age and gender were not consistently associated with well-being. Income was consistently associated with well-being: higher income (over GBP 35,200) was significantly related to greater levels of positive affective well-being (T2, T3), meaning (T2, T3), and life satisfaction (T2, T3, T4) and lower levels of negative affective well-being (T2, T3) and loneliness (T1-T4). Negative life events were significantly associated with well-being for all aspects of well-being at all time points, such that higher levels of negative life events were related to poorer well-being. Given these associations we included income and negative life events as control variables in all subsequent statistical analyses. The Effect of the Audiobook Intervention on Well-Being To examine the effect of our three conditions (novel, short stories, non-fiction) on well-being over time, we conducted a series of general linear analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) mixed effect models for each of our well-being variables, with time as a within-subjects factor (T1, T2, T3, T4) and condition as a between-subjects factor (novel, short stories, non-fiction), and income and negative life events as covariates. We were interested in significant interaction effects which would indicate a difference between conditions for well-being over time. No significant interaction effects were observed for any of our well-being variables: positive affective well-being: F(6, 219) = 0.68, p = .667, η2p = .018; negative affective well-being: F(6, 225) = 0.45, p = .847, η2p = .012; life satisfaction: F(6, 219) = 0.85, p = .535, η2p = .023; meaning in life: F(6, 219) = 0.41, p = .873, η2p = .011; loneliness: F(6, 222) = 0.38, p = .889, η2p = .010; mental well-being: F(6, 225) = 1.46, p = .194, η2p = .037 – see Table 2 for means and standard errors. We were also interested in the main effect of time which would suggest meaningful changes in well-being over time for all our participants. The effect of time was not significant in any of our models suggesting that, on average, well-being did not consistently improve or worsen over the intervention: positive affective well-being: F(3, 219) = 1.31, p = .273, η2p = .018; negative affective well-being: F(3, 225) = 0.36, p = .779, η2p = .005; life satisfaction: F(3, 219) = 0.71, p = .547, η2p = .010; meaning in life: F(3, 219) = 0.74, p = .528, η2p = .010; loneliness: F(3, 222) = 0.65, p = .583, η2p = .009; mental well-being: F(3, 225) = 0.74, p = .531, η2p = .010 – see Table 2 for means. The intervention was not therefore associated with reliable changes in well-being over time (for either fiction or non-fiction audiobooks). The Effect of Audiobook Absorption and Appreciation on Well-Being Next, we examined whether audiobook absorption and appreciation predicted well-being over time. To explore this, we conducted a series of multiple regression models (one for each well-being variable) with income, negative events, and the relevant well-being variable at T1 entered in the first step. First, we examined whether levels of absorption during the first two weeks of listening (T2) predicted well-being in the following two weeks (T3). Second, we examined whether levels of absorption during the second two weeks of listening (T3) predicted well-being in the two weeks following the intervention (T4). Third, we examined whether overall appreciation of the audiobook (measured at T3) predicted well-being in the two weeks following the intervention (T4). T2 absorption predicting T3 well-being. The overall regression models were significant for: meaning in life, R2 = .38, F(4, 82) = 11.91, p < .001); loneliness, R2 = .54, F(4, 82) = 22.50, p < .001); and mental well-being, R2 = .51, F(4, 83) = 20.60, p < .001. Results showed that absorption during the first two weeks of listening was a positive predictor of meaning in life (B = 0.23, SE = .10, β = .20, t = 2.21, p = .030, 95% CI [.02, .43]), and mental well-being (B = 0.11, SE = .05, β = .17, t = 2.16, p = .034, 95% CI [.01, .20]), and a negative predictor of loneliness (B = -0.09, SE = .04, β = -.16, t = -2.12, p = .037, 95% CI [-.18, .-01]) during the two weeks that followed. T3 absorption predicting T4 well-being. The overall regression models were significant only for meaning in life, R2 = .42, F(4, 77) = 12.96, p < .001, such that absorption during the final two weeks of listening to the audiobook was a positive predictor of meaning in life during the two weeks following the intervention (B = 0.23, SE = .10, β = .21, t = 2.31, p = .024, 95% CI [.03, .42]). The longitudinal relationship between audiobook absorption and presence of meaning in life is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1 he Relationship between Participants’ Level of Absorption in their Audiobook and their Reported Presence of Meaning in Life for the two Weeks following its Completion.   T3 appreciation predicting T4 well-being. The overall regression models were significant only for meaning in life, R2 = .41, F(4, 77) = 12.76, p < .001, such that participants overall appreciation of their audiobooks was a positive predictor of meaning in life during the two weeks following the intervention (B = 0.19, SE = .09, β = .20, t = 2.20, p = .031, 95% CI [.02, .36]). Supplementary Analysis of the Effect of Frequent Reading on Well-being To examine whether frequency of reading fiction prior to the study may have had an impact on participants’ well-being at entry to the study, we tested ANCOVA models with the baseline (T1) well-being variables used in turn as the dependent variable, a median-split of the frequency of reading fiction measure used as the independent variable, and income and negative events at T1 used as covariates. Compared to infrequent fiction readers (n = 34), frequent fiction readers (n = 49) reported greater life satisfaction (M = 4.67 vs. M = 3.99; F = 7.69, p = .007, η2p = .09) and greater positive affective well-being (M = 3.69 vs. M = 3.36; F = 6.04, p = .016, η2p = .07). There were no significant differences between frequent and infrequent fiction readers for mental well-being, loneliness, meaning in life, and negative affective well-being. Frequent and infrequent non-fiction readers did not show any differences in well-being. A repeated measures ANCOVA with book absorption in the first and second two weeks of the study as the within-subjects factor showed that, compared to infrequent fiction readers (n = 36), frequent fiction readers (n = 48) were more absorbed by their audiobook (M = 4.97 vs. M = 4.39; F = 6.14, p = .015, η2p = .07). Frequent and infrequent non-fiction readers did not show a difference in absorption. Can listening to fiction versus listening to non-fiction improve well-being over a period of several weeks? This was the central question addressed in the present study. Reading and well-being have been closely associated (Billington, 2015) but the cross-sectional nature of previous research precludes causal conclusions from being drawn (e.g., people with greater well-being may simply read more, or some third variable may explain the association), and have not been extended to listening. Using randomized controlled trials, bibliotherapy research shows that emotional problems can be alleviated through exposure to non-fiction (Den Boer et al., 2004) but the effects of fiction on well-being (and in non-clinical contexts) have not previously been tested. Experimental work shows that exposure to extracts of fiction can provide benefits for socio-cognitive processes (such as theory of mind: Black & Barnes, 2015; Kidd & Castano, 2013; Kidd & Castano, 2017; Van Kuijk et al., 2018) but the impact of fiction on personal well-being and the effects of greater exposure (e.g., reading a novel as might be expected in naturalistic circumstances) are not known. These lines of research, together with anecdotal reports, suggest that literature has the potential to improve a person’s sense of well-being and that there may be something special about fiction. We sought to directly test this idea for the first time by conducting a longitudinal RCT with audiobooks to compare the effects of fiction (novels, short stories) and non-fiction on core components of well-being (e.g., subjective, eudaimonic, social) of older adults from diverse communities in a city over a six-week period. Contrary to expectation, participants in the fiction, compared to non-fiction, conditions did not show greater improvements in any aspect of well-being over the study period. There was also no evidence of a difference in the impact of novels and short-story compilations. In fact, on average across all conditions, participants did not show consistent improvements in any aspect of their well-being. Instead, our results paint a more nuanced picture of whether listening to an audiobook (fiction or non-fiction) is associated with well-being over time. The extent to which participants were absorbed in, and appreciated the content of, their audiobook was crucial to the impact that it had on well-being. Regardless of whether participants listened to fiction or non-fiction, the more absorbed they were when listening during the first two weeks of the study, the higher their levels of meaning in life, mental well-being, and the lower their levels of loneliness during the subsequent two weeks. Absorption during the second two weeks of the study had a lasting effect on meaning in life: participants who were more absorbed in their books during the last two weeks of listening had a greater sense of meaning in life during the two weeks after the intervention had ended. Participants’ overall hedonic and eudaimonic evaluations of their books (e.g., whether they were left with a lasting impression) also had an enduring impact on meaning in life: participants who had greater appreciation of their books overall had a greater sense of meaning in life during the two weeks after the intervention. Our intervention suggests that an audiobook does have impact on aspects of well-being over several weeks, but the impact is dependent on an individual’s personal experience with the contents of the book. Mar, Oatley, Djikic, and Mullin (2011) suggest that fiction will only induce personal transformations when readers engage in a deep experience with it. The effects of books are not universal or guaranteed but rather depend on the experience and outcomes of engaging with them. Many people consider reading as something they do for the hedonic pleasure it provides in the moment, while our research suggests that the activity can provide a more enduring benefit for their eudaimonic well-being. The idea that positive experiences of reading/listening to books can improve a person’s sense of meaning in life suggests that it may be one, relatively easy, method through which a lack of meaning can be addressed. This is particularly important given the host of functional benefits associated with having a meaningful life, including various aspects of physical and mental well-being, and even longevity (see Heintzelman & King, 2014; and Hooker, Masters, & Park, 2018, for recent reviews of the literature). Why might life feel more meaningful during and after listening to books? There are at least two potential explanations that follow from our findings. The first concerns the effects of the act of reading/listening which can result in a state of absorption. The implication is that the individual loses awareness of the self and the external world by mentally constructing another space and time and engaging with the events and people in the book. This may be akin to flow-like experiences which are thought to lead to meaning because they reflect the pursuit of meaningful and intrinsically rewarding activities (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Indeed, research has shown that reading is the most common flow-inducing activity (Massimini, Csikszentmihalyi, & Delle Fave, 1988) and that reading fiction is more likely to produce flow compared to non-fiction (Mcquillan & Conde, 1996). When people become absorbed in literature they can experience a sense of control, mastery, and ultimately purpose through behavioral engagement with the activity. However, these experiences seem less likely to be achieved through listening than they are through reading. The second way that reading/listening to literature might promote meaning is through appreciation (e.g., moving and thought-provoking experiences). This relies not only on the enjoyment and pursuit of the act of reading/listening but crucially on the emotional and cognitive effects of the literature’s content. Djikic and Oatley (2014) in their review of art in fiction propose that individuals who resonate more strongly with fiction, as indicated by strong emotions, are more likely to incorporate the depicted experiences of other people into their own experience and thereby change themselves. Likewise, books that resonate with individuals may facilitate both comprehension and meaning making processes (i.e., that one’s life is coherent and makes sense) as well as fostering mattering (i.e., that one’s life is significant). In this way, literature provides a means of making sense of personal and shared experiences and considering meaningful life questions (Koopman, 2015a; Oliver, 2008). The two proposed explanations – flow and appreciation – are not mutually exclusive, and may work in conjunction to make the act and outcomes of reading/listening particularly conducive to a person’s global sense of meaning. Although we did not find an overall improvement in well-being over several weeks, the findings provide indicative evidence that the impact of fiction on well-being may translate into longer term gains because participants who read fiction more frequently prior to the study reported greater satisfaction with life and positive affective well-being on entry to the study than infrequent fiction readers, and were also likely to find their audiobook more absorbing. Frequency of reading non-fiction did not seem to matter in the same way. However, unlike our other findings, these effects were correlational, so the causal direction of the relationship cannot be assumed – they may instead reflect personality differences between frequent and infrequent readers rather than the effect of them reading, and did not extend to all aspects of well-being. Strengths and Limitations Our study design had several strengths, including a longitudinal randomized controlled design, a multi-dimensional approach to well-being, consideration of mechanisms of potential effects (e.g., absorption, appreciation), adequate sample size to detect effects, and participants from diverse urban communities. There are also several limitations that should be considered. First, describing the study as being about reading and well-being may have alerted participants to a potential connection and thereby influenced their responses but this should not have affected the group comparisons in the analyses. Second, delivering the intervention via audiobook format allowed us to ensure consistency in the delivery of materials, avoid the potential effect of reading fluency on outcomes, and encourage people who may not typically read books to participate. That said, there may be differences between listening and reading, both in individuals’ preference for them and in the emotional response the formats provoke. Indeed, a few participants expressed frustration with the style of narration as well as with the constraints of the MP3 players (e.g., finding it harder to move backwards/forwards in the narrative than with a physical book). Previous studies have examined differences in emotional absorption between watching and listening to a story (Richardson et al., 2018) and between watching and reading a story (Bálint, Kuijpers, Doicaru, Hakemulder, & Tan, 2017) but have yet to compare reading and listening, which could be worthwhile. A third limitation is that the non-fiction literature we used may have had a storytelling mode which would have engaged equivalent mental simulation processes in the reader/listener as fiction. Specifically, our comparison of fiction and non-fiction may have been affected by selecting non-fiction works that have characteristics that are purported to be beneficial for fiction (e.g., narrative style, first person narrative). Although we offered a range of non-fiction works, the overwhelming choice of participants was “Cure” (selected by 22 of 32 participants in that condition) which is a book that uses stories to illustrate scientific research (i.e., it employs a narrative style). Compared to the other non-fiction books, this book may also have had greater personal relevance to our older sample given its focus on ill health and potential ways of mentally counteracting it. An alternative approach for future studies would be to use a passive control condition in which participants are not given an intervention (but that raises the potential for any effect of fiction to be a placebo effect) or are given a meaningless reading/listening activity. Fourth, we allowed participants to select a book from a limited range because previous research has noted that it is difficult to achieve reading engagement in volunteer samples (Mar et al., 2011) and choice may help achieve that, but this meant that we were unable to ensure a balanced selection of books in any one category. Future Research and Practical Implications Future research may want to compare the effect of different styles of writing (expository, descriptive, persuasive, narrative) on well-being (see Koopman, 2015a for effects of writing style on empathy). Comparisons between specific forms of non-fiction could also be conducted. As highlighted above, the non-fiction book selected by the majority of our participants had a narrative style. This style may have a different impact than a paradigmatic style of non-fiction which focuses on explaining relationships between things (and is associated with a scientific mode of thinking) rather than on their meaning (Bruner, 1986). Our findings, however, suggest that the transformative effects of literature on well-being (especially meaning) are more likely to derive from characteristics that promote absorption and appreciation in an audience rather than from categories of fiction and non-fiction. Understanding in this research area would therefore benefit from identifying those characteristics and how they impact on different aspects of what makes life meaningful (e.g., purpose, comprehension, mattering; Hooker et al., 2018). There are also implications for future reading interventions which might seek to maximize flow/absorption and the potential for facilitating meaning-making/mattering through book selection. Examples might be optimizing flow-like experiences by selecting books written with a first person narrative (Hartung, Burke, Hagoort, & Willems, 2016); ensuring a good fit between the book and a person’s reading skill and personal experience to appropriately balance challenge and skills (a key component of flow; Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2014); and maximizing the chance of creating moving and thought-provoking experiences through the use of books that concern issues of personal relevance to individuals (Berthoud & Elderkin, 2013). Extending the research evidence on reading interventions would help when incorporating books in medical dispensing practices to foster well-being. Various public health initiatives have given primary health care professionals the capacity to refer individuals to take part in cultural activities to aid their health and well-being (e.g., Froggett & Roy, 2014; Jensen, Stickley, Torrissen, & Stigmar, 2017; Konlaan et al., 2000). This form of social prescribing is known as “art on prescription” and has included listening to other people read (Jensen, 2019). In support of this idea, Billington, Humphreys, Jones, and McDonnell (2016) found that a shared reading-aloud intervention for individuals with chronic pain had positive effects on their mood and quality of life which may have occurred because the activity absorbed their attention. The effectiveness of such reading-related initiatives would be enhanced if they could draw on research that has compared the impact of different forms of bibliotherapy (e.g., non-fiction self-help literature vs. literary fiction) and different modes of delivery (e.g., listening to a story vs. reading). Literature contributes to the public good in a variety of ways (Rylance, 2016), including its benefits for health (e.g., Bavishi et al., 2016). The current study suggests that fiction and non-fiction do not in themselves have reliable effects on well-being but that enhancing people’s absorption in, and appreciation of, them can be an effective means of reaping their potential rewards for people’s well-being, including their sense of having meaning in life. a Conflict of Interest aThe authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We thank Elana Moore and Emily Preston-Jones for their help with data collection and Emma Warnock for her assistance with data entry. Cite this article as: Poerio, G. & Totterdell, P. (2020). The effect of fiction on the well-being of older adults: A longitudinal RCT intervention study using audiobooks. Psychosocial Intervention, 29, 29-38. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a16 Funding: This work was part of a collaborative research partnership with Luisa Golob at Ignite Imaginations (a UK charitable arts organization) and was funded by a research grant from Arts Council England (32312010). |

Cite this article as: Poerio, G. & Totterdell, P. (2020). The Effect of Fiction on the Well-Being of Older Adults: A Longitudinal RCT Intervention Study Using Audiobooks. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(1), 29 - 38. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2019a16

totterdell@sheffield.ac.uk Correspondence: p.totterdell@sheffield.ac.uk (P. Totterdell).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS