Suicidal Ideation and Suicidal Attempt in Spanish Adolescents: Risk Profiles Identified Through Decision Tree Analysis

Teresa I. Jiménez1, J. Francisco Estévez-García2, Gonzalo Musitu3, and Estefanía Estévez4

1University of Zaragoza, Teruel, Spain; 2University of Alicante, Spain; 3Pablo Olavide University, Seville, Spain; 4Miguel Hernández University, Elche, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a13

Received 25 April 2025, Accepted 12 June 2025

Abstract

Objective: Adolescent suicide has become a serious public health problem in Spain, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. The research aims were twofold: (1) to explore the key risk factors for suicidality in adolescents in a pool of family, peer, and school relational factors and (2) to analyze specific interactions between them. These objectives involved differentiating suicidal ideation from suicidal attempt and participants’ gender. Method: Participants were 3,252 adolescents enrolled in Compulsory Secondary Education schools in Spain, aged between 11 and 17 years (49.3% boys). ANOVAs and chi-square tests were used for group comparisons, and conditional inference tree analysis was applied for multivariate analysis. Results: Negative mother’s and father’s parental styles, gender, having a partner, child-to-mother violence, cybervictimization, and social media usage frequency were relevant predictors for, in that order. The tree model generated a series of useful decisions rules to identify subgroups of adolescents at elevated risk. The key predictors of suicidal attempt in girls were maternal negative parenting style along with an experience of cybervictimization. For suicidal ideation, key predictors in girls were having a partner, being violent toward their mothers, or having mothers with a negative parenting style, along with intensive social media use. For suicidal ideation in boys, cybervictimization in the absence of other relationship problems was the key predictor. Conclusions: These exploratory findings suggest different gender-based risk profiles to consider for targeted prevention strategies.

Keywords

Adolescence, Suicidal ideation, Suicidal attempt, Family, Peer victimization, Conditional inference tree

Cite this article as: Jiménez, T. I., Estévez-García, J. F., Musitu, G., and Estévez, E. (2025). Suicidal Ideation and Suicidal Attempt in Spanish Adolescents: Risk Profiles Identified Through Decision Tree Analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 161 - 173. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a13

Correspondence: eestevez@umh.es (E. Estévez).

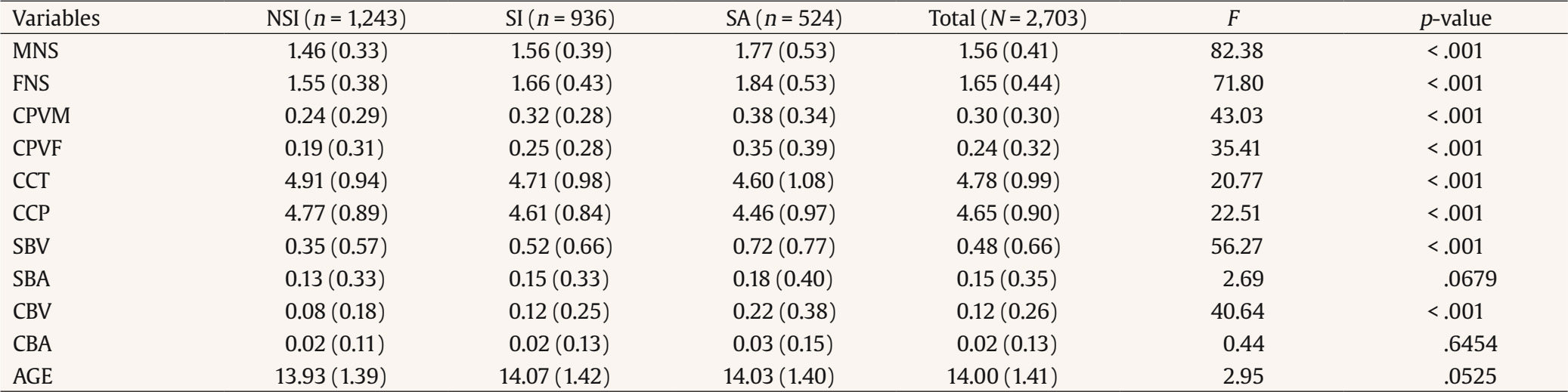

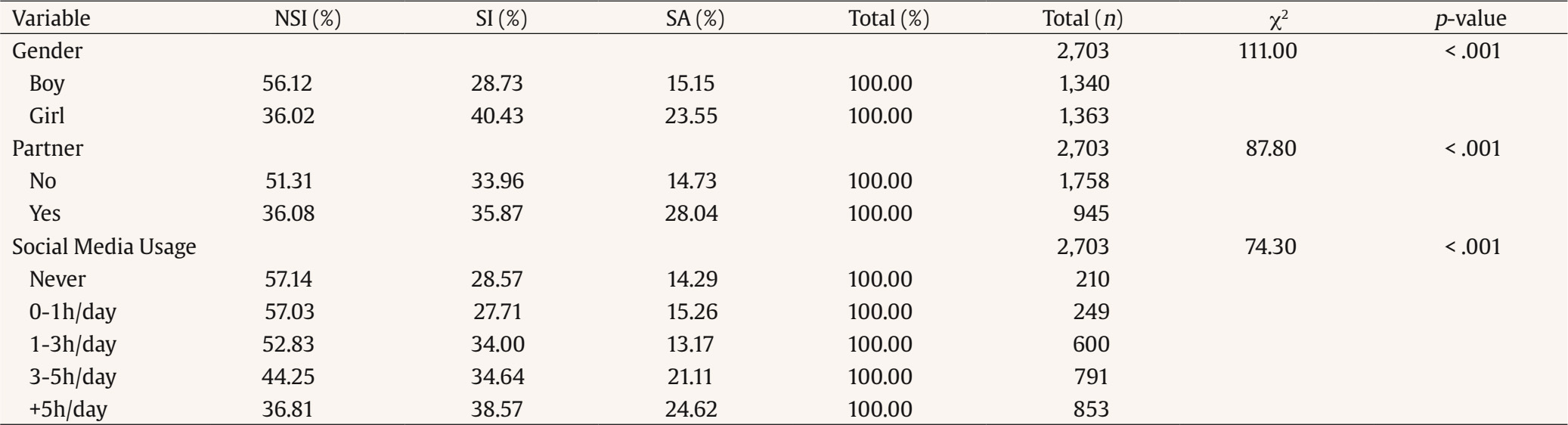

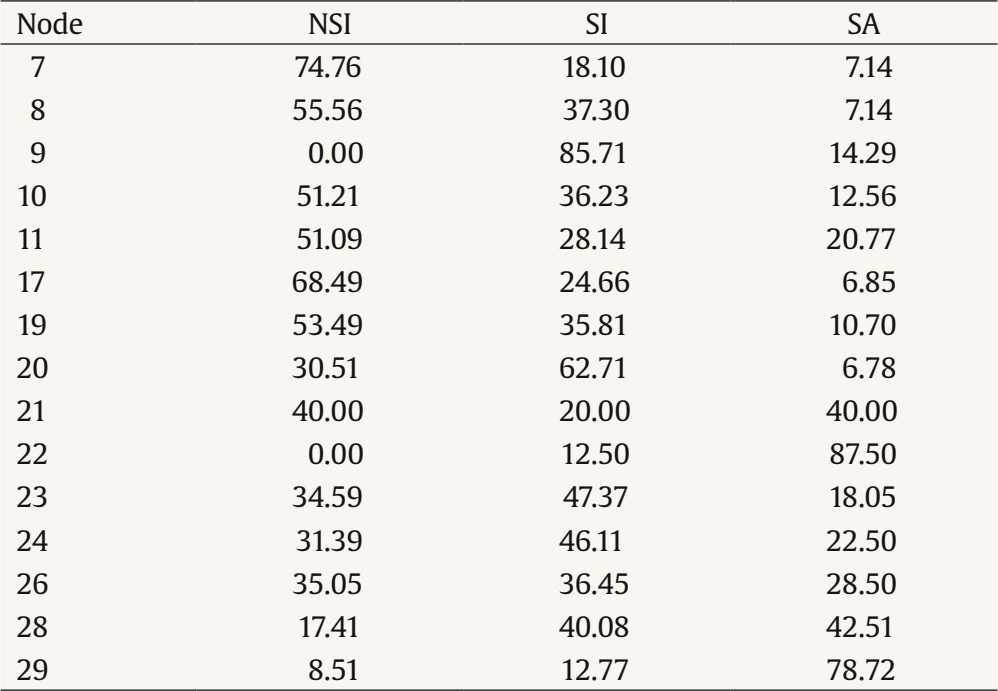

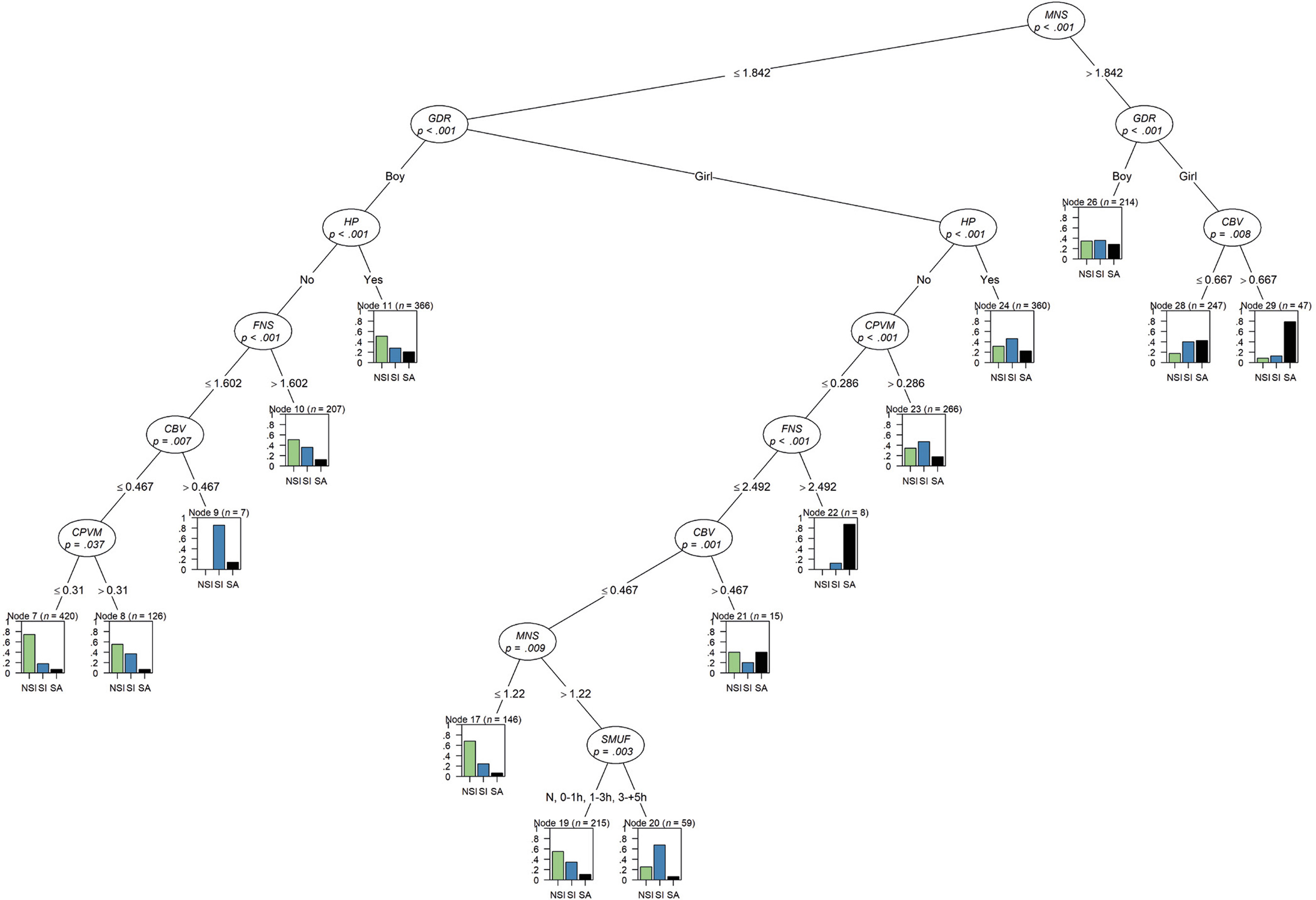

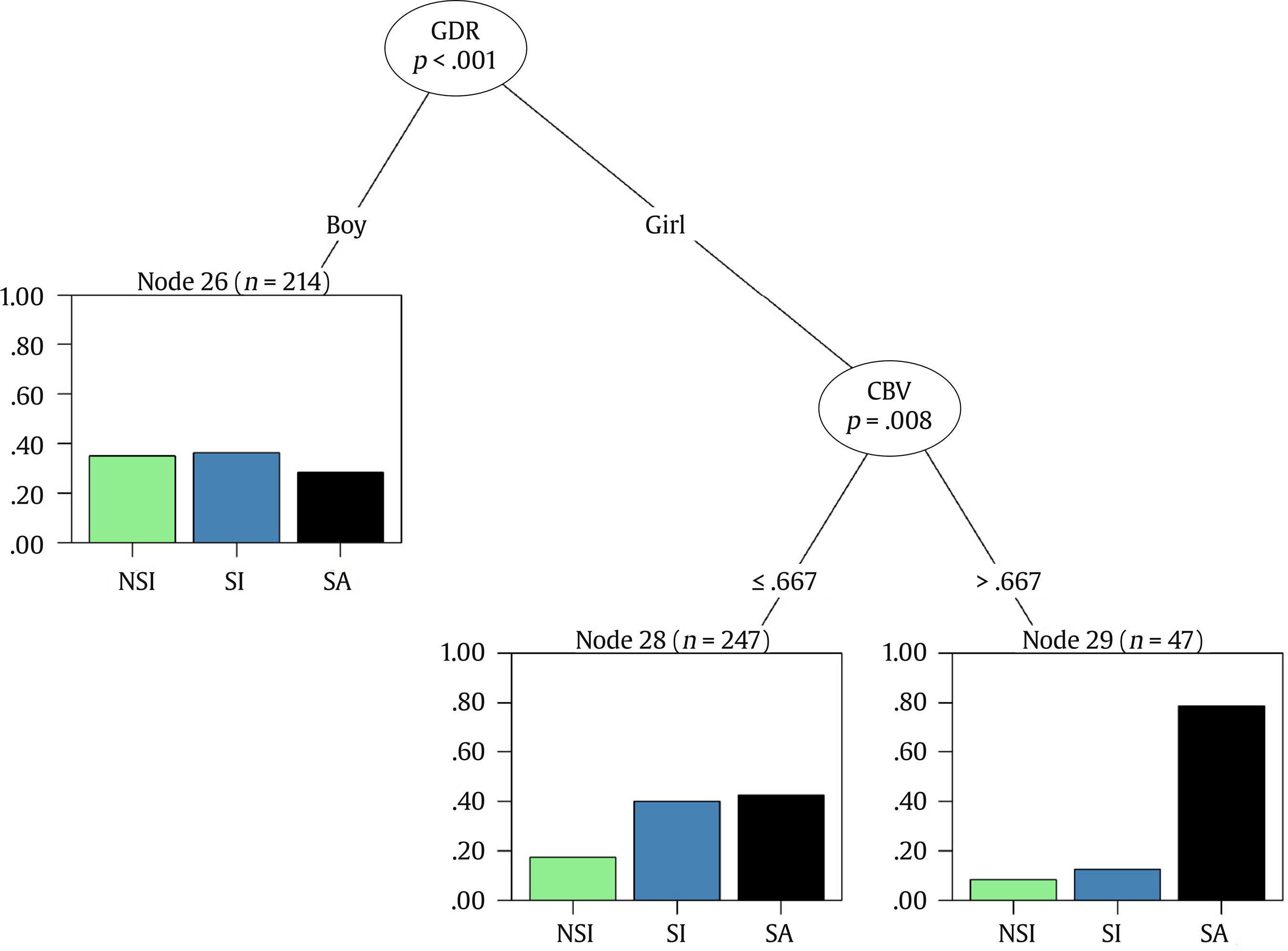

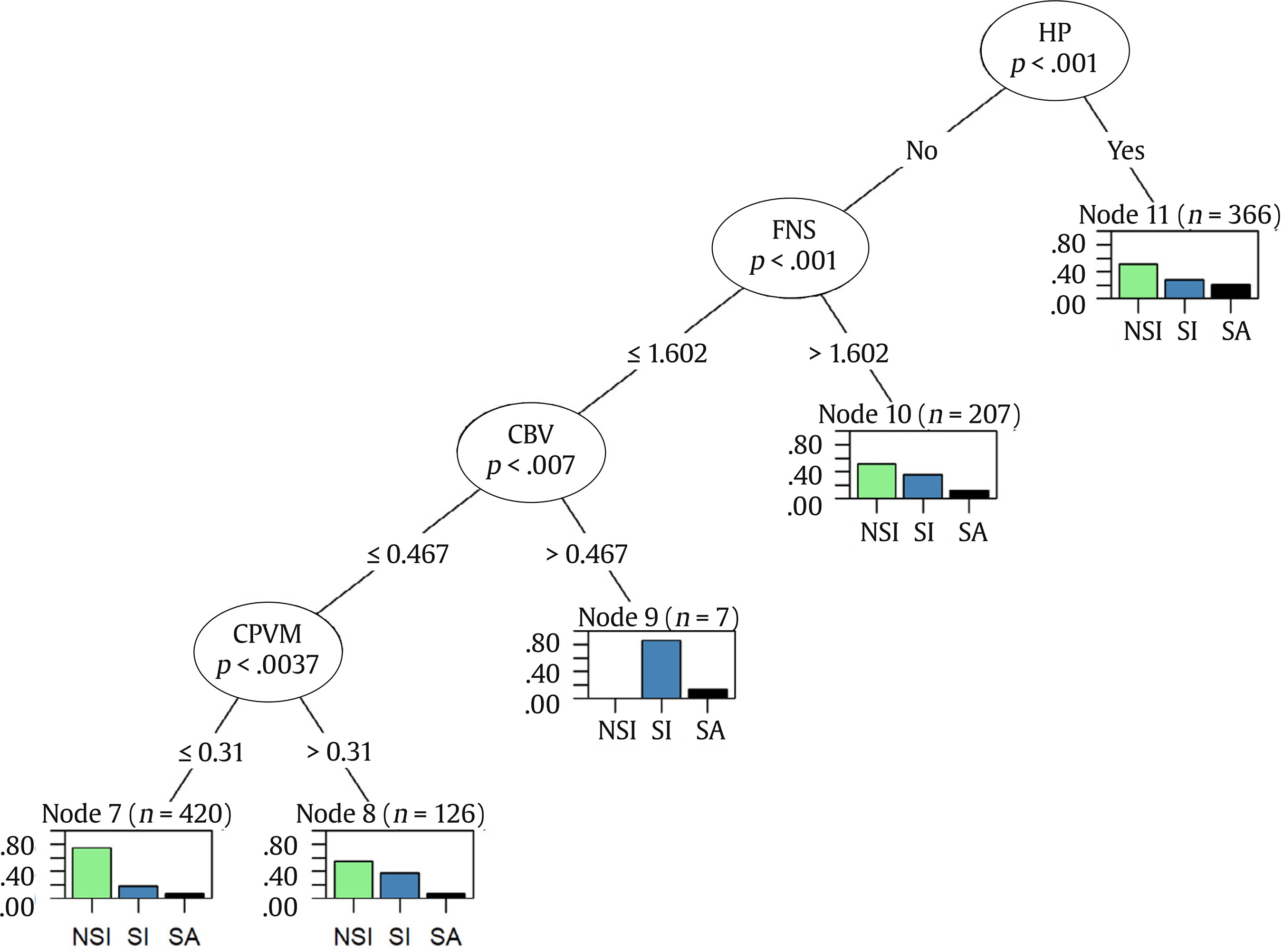

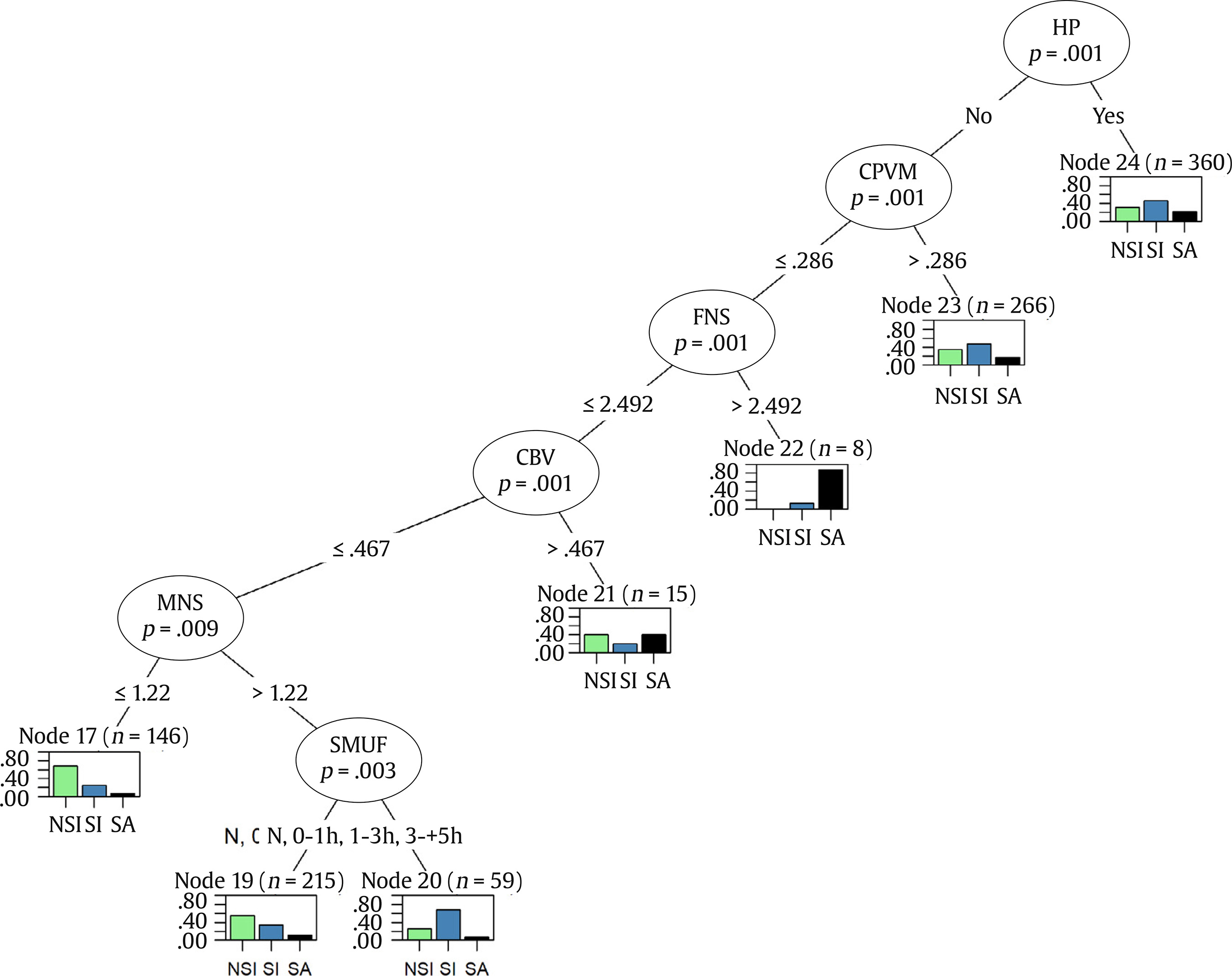

Adolescent suicide is a major concern worldwide and the fourth leading cause of death among 15 to 29 year-old young people according to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021) and the second one when considering a younger age group (5 to 19) according to the 2019 Global Burden of Diseases (Kim et al., 2024). This study, based on data from 204 countries between 1990 and 2019, showed a decrease in suicide rates during those decades. However, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have reversed this trend in many countries, increasing the risk of suicidal behavior in adolescents (Kim et al., 2024). This is Spain’s case, where suicide has been the first cause of external death in young people aged between 15 and 29 (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE, 2021, 2022, 2023]). Specifically, 2020 was the year with the highest frequency of suicides registered in the history of Spain, exceeding this maximum in 2021 (INE, 2022). Indeed, the pandemic had a devastating impact on young people’s mental health. In Spain and other countries, it was observed that the symptoms of anxiety, depression, sleep problems, and risk of suicide increased between 2019 and 2022, along with social isolation and problematic use of the internet (Villanueva-Silvestre et al., 2022; Windarwati et al., 2022), especially affecting girls aged 13 to 18 (Aarah-Bapuah et al., 2022). Recent metanalyses have reported an increase of 10% in the prevalence of suicidal ideation, 4.68% of suicidal attempts, and 10% of suicide deaths in adolescents after the pandemic than before the pandemic (Bersia et al., 2022; Dubé et al., 2021). Therefore, specialists have linked the increase in adolescent suicidality to a worsening of young people’s mental health in the pandemic and post-pandemic periods. Thus, the mental health of adolescents is a challenge today, which is overwhelming public health services in Spain and most of the world (Roncero et al., 2020; WHO, 2024). It is estimated that for every suicide that is completed, there have been twenty or more attempts (WHO, 2021). Suicidal ideation, that is, thoughts about the worthlessness of life and death wishes (Sveticic & De Leo, 2012), is much more frequent, with variations from country to country and between age and gender groups. For example, in a population-based study of 82 countries (Biswas et al., 2020), the global prevalence of suicidal ideation in adolescents (“Did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide during the past 12 months?”) was 14%, with the highest pooled prevalence observed in Africa (21.0%) and the lowest in Asia (8.0%). In Spain, using a similar question to evaluate suicidal ideation (e.g., “Have you ever thought of taking your life, even though you were really not going to do so?”), the prevalence data varies between studies carried out pre-pandemic (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2018) and post-pandemic (Jiménez et al., 2024), from 21.7 to 36.5%, and related to suicidal attempts (e.g., “Have you ever tried to take your own life?”) from 4.1 to 7.7%. In these studies, girls had a prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts between 28% and 35% higher than boys. Gender differences are paradoxical: in studies carried out with adult samples, women have rates of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts twice as high as men, but men exceed them in completed suicides (Beautrais, 2002; Turecki & Brent, 2016). In adolescents and young adults, these differences are replicated in meta-analyses (Glenn et al., 2019; Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019). Evidence suggests that suicidal ideation is one of the main risk factors for suicide deaths after a previous suicide attempt (Franklin et al., 2017; Goñi-Sarriés et al., 2018), and roughly one-third of adolescents with suicide ideation will go on to attempt suicide within one year (Nock et al., 2013). Although the nature of transitions between these two stages of suicidality remains poorly understood (Sveticic & De Leo, 2012), both suicidal ideation and specific suicidal attempts have a significant and moderate association with suicide (for a review and meta-analysis, see Large et al., 2021). Therefore, their study is very important for developing specific prevention strategies to tackle the suffering associated with both stages of suicidality in adolescents. However, very few studies have analyzed the potentially different profiles of people who think about suicide and people who have attempted suicide. In a study carried out with adults (Pirkis et al., 2000), it was found that people with suicide attempt history are more likely to be unemployed and unmarried, and employment was the only factor differentiating people who have made a suicide attempt from those who have thought about suicide but not acted out on their ideation. In another study carried out with adult men, Bennett et al. (2024) showed that higher levels of loneliness and mental health diagnosis increased the probability of being in the suicidal ideation group, and a mental health diagnosis and being non-heterosexual increased the probability of being in the suicide attempt group compared to controls. In the case of adolescents, studies are even scarcer. In a study carried out in Korea (Kwon et al. 2018), depression, peer victimization, internet-related delinquency, and positive attitudes toward suicide were associated with suicidal ideations and attempts. Adverse life events were also associated with suicide ideation, but not attempts, while not living with both parents and poor family relationships were associated with suicide attempts, but not ideation. Therefore, further empirical research to specifically explore potential psychosocial factors related to suicidal ideation and psychosocial factors related to suicidal attempts in adolescents is needed to develop informed primary detection and prevention programs. Moreover, this distinction must be made taking gender into account, given the existing evidence on relevant differences between boys and girls, both in the aforementioned prevalence rates and in potentially different risk profiles. In this line, in a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies carried out with adolescents, Miranda-Mendizabal et al. (2019) found that common risk factors of suicidal behaviors (including suicide attempts or death) for both genders were previous mental disorders or substance abuse disorder and exposure to interpersonal violence. Female-specific risk factors for suicide attempts were eating disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, bipolar disorder, being a victim of dating violence, depressive symptoms, interpersonal problems, and previous abortion. Male-specific risk factors for suicide attempts were disruptive behavior/conduct problems, hopelessness, parental separation/divorce, a friend’s suicidal behavior, and access to means. In a more recent study carried out with Spanish adolescents, Jiménez et al. (2024) identified peer victimization and a mother’s negative parenting style as common risk factors for suicidality (including suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts) in both boys and girls. Moreover, for boys, violence towards the father was also a relevant risk factor, whereas for girls this factor was significant only in interaction with a high level of the mother’s negative parenting style. Some identified suicide risk factors for adolescents overlap with those for adults (e.g., mental health diagnosis). Nevertheless, the developmental characteristics of adolescence may strengthen the impact of some factors. Indeed, considering that development at the adolescent stage involves a dynamic interaction of different relational systems and that adolescent psychological adjustment is strongly rooted in social goals, the issue of adolescent suicidality must be approached and understood from an ecological view (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006; Gallagher & Miller, 2018), including the role of significant relational contexts, that is, peer group, school, and family. Even more, from a specific model of suicide, such as the Integrated Motivational-Volitional model (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018), suicidal behavior results from a complex interplay of factors where the quality of relationships with peers, parents, and teachers can be understood as motivational moderators that increase or decrease feelings of entrapment that precede to ideation and intention formation of suicide as a salient solution to life circumstances. In this way, empirical studies and reviews have identified relevant risk and protective factors for adolescents’ suicidality in their significant relational contexts. Among peer factors, it is worth highlighting being a victim of bullying and/or cyberbullying (e.g., Estévez-García et al., 2023; Iranzo et al., 2019; Katsaras et al., 2018; Quintana-Orts et al., 2021) and of intimate partner violence (Barter & Stanley, 2016; Devries et al., 2013), especially for girls and in an online context (Macrynikola et al., 2021). At the school level, factors such as low school attachment (Haynie et al., 2006) and low perceived teacher support (Cava & Musitu, 2003) have been identified. Finally, at family level, studies point to poor parent-child attachment, low parental support, low family cohesion and communication, child abuse, neglect, and intense child-parent conflicts and violence (Buelga et al., 2024; Fortune et al., 2016; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2020; Sánchez-Sosa et al., 2010; Suárez-Relinque et al., 2023). Together, these and other reviews (e.g., Ati et al., 2021; Wasserman et al., 2021) can identify between 20 and 30 risk factors and 5 and 10 protective factors. Developing prevention and intervention strategies to manage so many factors is complicated. Moreover, most research focuses on examining the impact of an isolated factor or domain of factors, but their underlying interrelationships are likely more complex. Thus, more specific research is key to identifying the most relevant risk factors and the interplay between them to prioritize and focus the prevention efforts. From the perspective of public mental health, adolescent suicide is a main issue to address. Previous research has linked many factors to adolescent suicidality, but few of them have considered how these factors may act together to increase the risk of suicidal thoughts or actions. We need good insights into the key risk factors and their interplay to obtain relevant information. Consequently, the aims of this research were twofold: (1) to explore the main risk factors for suicidality in adolescents in a pool of family, peer, and school factors previously identified as relevant from an ecological perspective and (2) to analyze their specific relevant interactions. As mentioned above, some authors have argued the relevance of distinguishing psychosocial factors related to thinking about suicide from factors related to attempted suicide. However, very few studies have made this distinction with adolescent samples, and even fewer have taken gender differences into account. Therefore, these objectives will be developed by differentiating suicidal ideation from suicidal attempt and the participants’ gender to formulate potential specific risk profiles and make informed decisions for early detection and prevention programs. To achieve these objectives, conditional inference tree analysis will be used. Decision trees can be used within adolescent suicide research because they can examine complex interactions among risk factors, place greater emphasis on key differentiating factors, and identify high-risk groups that can be targeted by prevention and intervention efforts (Battista et al., 2023). Participants Data were collected from a sample of Spanish secondary school students through random cluster sampling in eight schools from the Valencian Region, Aragon, and Andalusia. The primary sampling units were urban and rural areas within these three regions, with public secondary schools as the secondary units. All students from first to fourth grade of Compulsory Secondary Education in the selected schools were included, leading to data collection in 173 classrooms. The study achieved a response rate of 81.1%, facilitated by institutional support and in-class guidance provided during questionnaire completion. The total sample comprised 3,252 adolescents (49.3% boys), of whom 2,703 were included in the analysis after excluding those who reported no relationship with either parent. Participants were aged 11 to 17 years (M = 14.02, SD = 1.42), evenly distributed by academic level: 24.7% in first grade, 25.9% in second grade, 25.0% in third grade, and 24.4% in fourth grade of Compulsory Secondary Education. Regarding family living arrangements, 66.0% of the adolescents lived with both their father and mother, 7.4% lived with their father, mother, and other relatives, 10.2% alternated living with each parent,13.2% lived with only one parent, usually with their mother or with their mother and other relatives, and 3.1% indicated other living situations. The students had an average of 1.2 siblings. Concerning origin, 90.4% of students were Spanish, with the remainder predominantly from Latin American countries. Among the parents, the majority had secondary education (23. 7% of fathers, 21.1% of mothers) or university degrees (18.2% of fathers, 24.2% of mothers). Approximately 17.7% of students were unaware of their father’s educational level, and 12.47% were unaware of their mother’s educational level. Procedure Data for this research were collected between February and May of 2022 as part of a larger study on violent behavior, school bullying, cyberbullying, and suicidal behavior in adolescents after gaining the approval of the corresponding research ethics committee of the participating university. The study complies with the ethical values required in research with human beings and follows the fundamental principles of the Helsinki Declaration. First, a letter with a summary of the research project was sent by email to the selected schools. Subsequently, initial telephone contact with the school principals was established, followed by a briefing with the teaching staff in each school, briefing them on the objectives and methodology of the study in a 2-hour presentation. In parallel, a letter describing the study was sent to the parents, requesting them to indicate in writing if they did not wish their child to participate (1% of parents used this option). Students also attended a short briefing in which they provided written consent. A group of trained and expert researchers in each region administered an online survey. To monitor the process and ensure comprehension of the items, at least two researchers were present in each classroom during data collection. Participants voluntarily and confidentially filled out the scales during a regular class period of about 50 minutes. Following the recommendations of the university ethics committee that approved the study, a code was assigned to each student. Thus, we could identify participants at risk due to their level of victimization or suicidal ideation and activate the corresponding institutional intervention protocols. Instruments Dependent Variables Suicidal Ideation and Suicidal Attempt. These variables were assessed using the Paykel Suicide Scale (Paykel et al., 1974) in its Spanish adaptation by Fonseca-Pedrero et al. (2018). This scale consists of five dichotomous (Yes/No) items that assess different levels of suicidality experienced during the past year, ranging from general thoughts of dissatisfaction with life to specific suicidal attempts. Items 1 to 3 assesses general discomfort with life and suicidal ideation (e.g. “Have you ever felt that life is not worth living?”). Items 4 and 5 address suicidal attempts, including suicide plans. In the present study, the scale’s internal consistency, measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was .83. For analytical purposes, participants were classified into three mutually exclusive groups. The first group, No Suicidal Ideation (NSI), comprised individuals who answered all items negatively, indicating no signs of suicidal thoughts or behaviors. The second group, Suicidal Ideation (SI), included participants who provided positive responses to at least one of the items assessing suicidal ideation (Items 1 to 3) but not to those assessing suicidal attempt. The third group, Suicidal Attempt (SA), consisted of adolescents who reported positive responses to one or both items evaluating suicidal plans and attempts (Items 4 and 5), regardless of their responses to the previous items. This classification is consistent with previous research (Bennett et al., 2025; Bertolote et al., 2005; Dubé et al., 2021) and allowed for a detailed understanding of the spectrum of suicidality within the sample, distinguishing between different stages of suicide risk: the absence of suicidal symptoms, the presence of suicidal thoughts, and the occurrence of suicidal plans and attempts. Independent Variables Family Context. The family context was assessed through measures that captured parenting styles and the presence of child-to-parent violence, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of family dynamics. Negative Parenting Styles. These styles were evaluated using the Child-Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ; Rohner, 2005) in its Spanish adaptation by Del Barrio et al. (2014). This instrument consists of 29 items that measure four dimensions related to the behavior of both parents toward their child. The four dimensions are: Fondness/affection, composed of eight items (e.g., “Says good things about me”), Hostility/aggression with six items (e.g., “Hits me, even when I don’t deserve it”), Indifference/neglect composed of six items (e.g., “Doesn’t pay attention to me”), and Rejection with four items (e.g., “When I misbehave, it makes me feel like I’m not loved”). Responses were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (rarely true) to 4 (almost always true). For this study, the four subscales were combined to compute a global index of negative parenting style for each parent. The fondness/affection dimension was reversed to reflect a lack of affection, following the procedure proposed by Del Barrio et al. (2014). Separate scores were obtained for mothers and fathers, generating the Mother’s Negative Style and Father’s Negative Style indices. Higher scores on these scales indicate more negative parenting behaviors. In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha for the global scores was .95 for mothers and .95 for fathers, demonstrating excellent internal consistency. Child-to-parent Violence. This was assessed using the Adolescent Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire (CPAQ; Calvete et al., 2013). This instrument evaluates children’s psychological and physical violence towards both their mother and their father, exercised during the last year. The scale comprises two subscales of 10 items completed separately for each parent. Sample items are: “You insulted or swore at your mother” (psychological violence) and “You hit your father with something that could hurt” (physical violence). Responses are given on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (frequently). For the present study, psychological and physical violence subscales were combined to create separate indices of Child-to-Parent Violence toward the Mother and Child-to-Parent Violence toward the Father. Higher scores indicate higher levels of aggression toward the respective parent. The internal consistency of the global scale measured through Cronbach’s alpha was .75; by dimensions, it was .72 and .75 for psychological violence towards the mother and the father, respectively; and .70 and .77 for physical violence towards the mother and the father, respectively, indicating acceptable internal consistency. This dual focus on parenting styles and child-to-parent violence provided a detailed picture of the parent-child relationships, capturing both parental behavior towards the children and children’s violent behaviors toward their parents. School Context. The school context was evaluated using instruments that assessed classroom climate and involvement in school bullying, providing insights into key dynamics in the adolescents’ daily lives within the educational setting. Classroom Climate. This was measured using the Relationship dimension of the Classroom Environment Scale (CES; Moos & Trickett, 1973) in the Spanish adaptation by Fernández-Ballesteros and Sierra (1989). This instrument comprises 20 items, which evaluate two subscales of classroom relationships from the student’s perspective: Affiliation and Teacher Support. The Affiliation subscale captures the degree of friendship and support among classmates (e.g., “Students in this class get to know each other really well”), whereas the Teacher Support subscale measures the extent to which the homeroom teacher provides help, trust, and confidence to their students (e.g., “The teacher takes a personal interest in the students”). Responses are given on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). In this study, the internal consistency of the global scale measured through Cronbach’s alpha was .82, and .74, and .81 for the Affiliation and Teacher Support subscales, respectively. These measures provided insights into classroom relationships through the dimensions of Classroom Climate-Teacher and Classroom Climate-Peers. School Bullying. These dynamics were assessed using the Peer Bullying Screening (Garaigordobil, 2013), an instrument designed to measure school bullying victimization and aggression and cyberbullying behaviors. The first part of the instrument comprises the Bullying subscale, which includes nine items assessing four modalities of bullying during the last year: physical, verbal, social, and psychological. Participants respond to two parallel questions: “Have you been attacked or molested in this way in the past year?” and “Have you attacked or molested others in this way in the past year?”. Responses are given on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always), which allows for the classification of involvement in bullying as victim or aggressor. This study extracted two dimensions: School Bullying Victimization and School Bullying Aggression. The internal consistency of the full scale was .81, with Cronbach’s alpha values of .83 and .80 for the Victimization and Aggression subscales, respectively. These measures provided relevant information about key elements of adolescents’ face-to-face relationships in school with the teacher and classmates, such as perceived support, affiliation, aggression, and victimization. Online Context. The online context was assessed through measures of cyberbullying involvement and social media usage frequency, capturing both harmful online interactions and general patterns of digital engagement. Cyberbullying. This was evaluated using the second part of the Peer Bullying Screening (Garaigordobil, 2013). As described previously, the first part of this instrument focuses on school bullying, whereas the second part specifically measures cyberbullying dynamics involvement during the last year. This section evaluates cyberbullying-related behaviors using the same 4-point Likert response scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). The scale includes 30 items in two parallel subscales: one measuring victimization (15 items, e.g., “Have you been blackmailed or threatened through calls or messages?”) and another assessing aggressive behaviors (15 items, e.g., “Have you disseminated private or compromising photos or videos of someone via mobile phone or the Internet?”), offering two indices, Cyberbullying Victimization and Cyberbullying Aggression. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale of cyberbullying was .91, with internal consistency values of .89 for CBV and .90 for CBA. Social Media Usage Frequency. This was assessed through a single item in the questionnaire, which asked participants how many hours per day they connected to social media for communication, viewing, or sharing information with other people. The item included six response options ranging from 0 (I never connect to social media) to 5 (More than 5 hours a day). This measure provided an overview of adolescents’ social media usage habits, with higher scores indicating more frequent use of social media. These measures provided insights into both the presence of cyberbullying involvement and social media in adolescents’ daily lives, offering a comprehensive understanding of their online context. Sociodemographic and Partner Relationship Variables. Sociodemographic and partner relationship variables were included to provide specific information about the participants. Gender was coded as a binary variable, with 0 indicating male and 1 indicating female. Age was recorded as a continuous variable ranging from 11 to 17 years, reflecting the typical age range of secondary school students in Spain. The presence of a romantic relationship as assessed with the question: “Have you had a partner in the last year?” Responses were coded as a binary variable (0 = No, 1 = Yes). This variable identified adolescents who had been involved in romantic relationships during the specified time frame. Data Analysis We assessed whether the missing data, which accounted for less than 5% of the dataset, could be considered Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) using Little’s MCAR test implemented in the MissMech R package. Missing data could be treated as random, justifying the use of imputation techniques without introducing bias into the analysis. The missing values were subsequently imputed using Predictive Mean Matching (PMM), implemented via the Mice package in R. Subsequently, descriptive statistics were calculated. Measures of central tendency, variability, and frequency distributions were computed for both continuous and categorical variables, ensuring that the data were appropriate for subsequent modeling. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for continuous variables to compare differences between the dependent variable groups (NSI, SI, and SA). In cases where Levene’s test indicated a violation of the homoscedasticity assumption, the Welch ANOVA was used, as it is more robust to unequal variances. For categorical variables (gender, partner and social media usage frequency), a hypothesis test for independence was conducted using the chi-square test. Table 1 Means (Standard Deviations) of Metric Variables by Group of Suicide Risk, with ANOVA Results   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA = suicidal attempt; MNS = mother’s negative style; FNS = father’s negative style; CPVM = child-to-parent violence towards the mother; CPVF = child-to-parent violence towards the father; CCT = classroom climate-teacher; CCP = classroom climate-peers; SBV = school bullying victimization; SBA = school bullying aggression; CBV = cyberbullying victimization; CBA = cyberbullying aggression. To identify predictive factors for the dependent variable, a conditional inference tree (CTREE) was employed using the “Ctree()” function from the party package in R (Hothorn & Zeileis, 2015). CTREE is a statistical model that identifies the most relevant predictors of an outcome thorough recursive partitioning. The subgroups are determined using a series of binary splits that resemble a tree structure. CTREE separates the splitting determination into two steps. First, the optimal variable to split on is chosen based on the strongest association with the outcome. Second, the optimal splitting point for that variable is determined. This splitting process continues recursively among each subgroup until a stopping rule is reached. Continuous and categorical variables can be split multiple times throughout the tree at different cut-points. This multivariate technique was selected for its robustness to statistical assumptions, such as normality and linearity, and its ability to handle datasets with mixed-type predictor variables (continuous and categorical) and complex relationships between them while maintaining interpretability. By focusing on statistically significant splits, the model highlights the most relevant predictors and their hierarchical relationships with the dependent variable, providing a clear and interpretable framework for understanding the factors associated with suicidality in adolescents (for a further explanation of its applicability to youth mental health studies, see Battista et al., 2023). The predictor variables included in this study are the dimensions of negative parenting styles, child-to-parent violence, classroom climate, school bullying, cyberbullying, and the adolescents’ gender, age, partner relationship status, and frequency of social media usage. Next, the CTREE was built by recursively partitioning the data into subsets, using statistically significant splits determined via conditional independence tests based on p-values. Continuous predictors (e.g., age and parenting styles) were divided at optimal thresholds, while categorical predictors were partitioned by their levels. Additionally, the relative importance of each predictor was assessed through the Varimp function in R. This approach involves randomly shuffling the values of each variable (100 permutations in this study), while keeping the rest of the model unchanged. The model’s predictive accuracy before and after each permutation is then compared to estimate the unique contribution of each predictor. A greater decrease in accuracy indicates higher importance, as it suggests that the variable plays a key role in the model’s decision-making process. This method is particularly suitable for CTREE models because it accounts for interactions between variables and avoids the bias of favoring predictors with more possible splits—a common issue in traditional decision trees (Strobl et al., 2007). Finally, a 10-fold cross-validation approach was applied to validate the model. Cross-validation involves dividing the data into folds, using one subset for training and the remaining subsets for testing iteratively, which ensures a robust evaluation of the model’s performance. Performance metrics, such as precision and area under the curve (AUC), were calculated to assess the model’s ability to accurately classify participants into the three groups of the dependent variable. The final decision tree was visualized to highlight the hierarchy of predictive factors, with terminal nodes displaying bar graphs showing the proportions of participants in each category of the dependent variable. Preliminary Analysis Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of the metric variables analyzed in the model, distributed according to the categories or groups of the dependent variable (NSI, SI, SA), together with the results of the ANOVA. Regarding the family context, we observed that the relationship of negative parenting styles with suicide risk increased. These increases were statistically significant, suggesting that both negative maternal and paternal styles were associated with adolescents’ suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt. An increase in the mean child violence toward the mother and the father as a function of suicide risk was also observed. Both increases were statistically significant, revealing that increased violence is also associated with the risk of suicidality. Concerning the school and online contexts, both the teacher- and peer-related classroom climate showed an inverse trend with the risk of suicide. Again, the differences were statistically significant, suggesting that a positive classroom climate is linked to lower levels of risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt. Regarding school and online victimization, adolescents in the SA group obtained significantly higher values than adolescents in the NSI group, both in school bullying victimization and cybervictimization school bullying victimization and cyberbullying victimization. Therefore, these forms of bullying are also important risk factors. However, school bullying aggression and cyberbullying aggression showed low scores in all the groups, and the group differences were not statistically significant. Finally, the groups’ mean age did not differ substantially and was not statistically significant. These results suggest that negative parenting styles, child-parent violence, school victimization, and school climate are significantly associated with adolescents’ suicidal ideation and behavior. In contrast, school bullying, cyberbullying, and age did not show significant group differences. Table 2 presents the descriptive results of the three categorical variables included in the analysis: gender, partner relationship, and usage frequency of social networks, also disaggregated according to the categories of the dependent variable. Table 2 Percentages of Categorical Variables by Group of Suicide Risk   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA: suicidal attempt. The analysis revealed significant differences in gender distribution according to the suicidal risk groups, with a higher percentage of girls in the SI and SA groups. The data also suggested that having a partner relationship could be associated with increased vulnerability to suicide risk. Finally, social media usage frequency showed a striking pattern. In general, as the use of social networks increased, so did the proportion of adolescents with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt. For example, among users with a network consumption greater than five hours a day, only one-third did not present suicidal ideation, whereas in groups with lower consumption the percentage of adolescents with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt was significantly lower. This pattern suggests that intensive social media use may be associated with adolescents’ increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt. Taken conjointly, these findings suggest increased vulnerability in certain groups: girls, adolescents in a partner relationship, and those who use social networks intensively on a daily basis have a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt. Analysis of the Conditional Tree Model The CTREE analysis allowed us to identify the key variables and their relative importance in the prediction of suicide risk. All variables were entered into the CTREE model. However, only those that significantly contributed to dividing the sample—either directly or through interactions—are represented in the tree. The results indicated that negative parenting styles, gender, cybervictimization, having a partner, violence towards the mother, and high usage frequency of social media were significant predictors of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt, and interactions among these predictors construct a hierarchical decision tree model (see Figure 1 for a visualization with higher resolution; see Appendix). Although the CTREE graph illustrates the distribution of cases by node, Table 3 shows more precisely the percentages of adolescents in each category of the dependent variables (NSI, SI, and SA) in each model node. Table 3 Distribution Percentage of the Dependent Variable in each Node of the Conditional Tree Model   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA = suicidal attempt. Figure 1 Conditional Tree Model for Predicting Suicide Risk in Adolescents.   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA = suicidal attempt; MNS = mother’s negative style (1-4); FNS = father’s negative style (1-4); CBV = cyberbullying victimization (0-3); GDR = gender; HP = has partner; CPVM = child-to-parent violence towards the mother (0-3); SMUF = social media usage frequency; N = never, 0-1h: until 1 hour/day, 1-3h: from 1 to 3 hours/day, 3-5h: from 3 to 5 hours/day, + 5h: more than 5 hours/day. Firstly, we observed that the negative maternal style was the main discriminating factor in the root node. Adolescents with high mother’s negative style values (> 1.842) were likelier to belong to the SI and SA groups. For example, in Node 29, comprising girls with high mother’s negative style scores and cybervictimization, 78.72% of the cases corresponded to the SA group, indicating an extreme risk associated with the combination of these factors. Moreover, the decision tree identified a threshold effect: beyond a low level of cybervictimization (> 0.667), the probability of SA increased sharply in girls with high mother’s negative style, forming a high-risk subgroup. Secondly, gender was also a relevant differentiating variable in the tree, showing that girls had a higher risk of suicidality. Even in adolescents with low mother’s negative style values, girls were more likely to be in the SI and SA groups. For example, in Node 24, 46.11% of the girls with a partner belonged to the SI group, while in Node 11, made up of boys with a partner, this percentage dropped to 28.14%. These differences reflect significantly different risk patterns for adolescents with a partner as a function of gender. The negative parental style was also relevant in the model. In adolescent boys with high father’s negative style values (> 1.602), the risk of suicidal ideation or behavior was greatly increased. This was evident in Node 10, where, overall, 48.79% of the cases presented SI or SA (36.23% and 12.56%, respectively). For girls, the relevance of the father’s negative style was critical for suicidal attempt in the absence of other risk factors. Thus, in Node 22, 87.50% of the cases corresponded to the SA group. Regarding the online context, several aspects should be highlighted. On the one hand, cybervictimization played an interesting role in the model. We observed that, in the absence of other potential risk factors, suffering from cybervictimization was different depending on gender: for boys, it meant an increase in SI (85.71% of cases in Node 9), and for girls, it meant an increase in SA (40% of cases in Node 21). On the other hand, even if girls did not suffer from cybervictimization, if their mother had a moderately negative style (> 0.122), 62.71% were in the SI group if their daily social media consumption was more than 5 hours (Node 20). Finally, the analysis also showed the relevance of having a partner as a variable that modulated risk as a function of gender. For boys, in Node 11 we observed that having a partner was associated with a lower risk of suicidal ideation for half of the cases (51.09%) but that the rest were distributed between the SI and SA groups. Moreover, in Node 10 we found that not having a partner could modulate the effects of having a father with a negative style, with 51.21% of cases in the NSI group. For girls, as mentioned in Node 24, we observed that having a partner was associated with increased SI. In addition, in Node 23, we found that among girls with a violent relationship with their mother not having a partner does not seem to mitigate suicidal risk. Regarding the relative importance of the variables estimated by the model, mother’s negative style was the primary risk factor for SI and SA, with a value of .0756, followed by father’s negative style, which also presented a significant weight of .0638 in the tree divisions. Gender, with a weight of .0619, reaffirmed the relevance of risk differences between boys and girls. Having a partner (.0591), child-to-mother violence (.0530), and cybervictimization (.0472) were also prominent factors, although with less weight than the parental styles. Finally, the social media usage frequency, with a value of .0082, was relatively much less important, indicating that it was not a key factor in the prediction of suicidal attempt except for suicidal ideation and in very specific circumstances such as those mentioned for Node 20. The tree model offered a series of reliable rules to identify adolescents classified in each suicidality group. Firstly, adolescents in the NSI group had low levels of all risk factors, both boys and girls (Nodes 7 and 17), although, with an important difference: in boys, 74.76% of the cases were classified in the NSI group out of a subsample of 420 subjects (Node 7) and in girls, only 68.49% of the cases were classified in the NSI group out of a subsample of only 146 subjects (Node 17). This implied that only 100 girls in the total sample had low levels in all risk factors and did not present suicidal ideation and that far fewer girls were in this low-risk situation compared to boys. Secondly, for boys, the key factor for the prediction of SI was having high cybervictimization in the absence of other risk factors (Node 9), whereas for girls, the key was having a partner and child-to-mother violence in the absence of other risks, and social media usage frequency together with a moderate mother’s negative style (Nodes 24, 23, and 20, respectively). Thirdly, for girls, the key factors for the prediction of SA was the combination of a mother’s negative style with cybervictimization (from low levels) and father’s negative style and cybervictimization in the absence of other factors (Nodes 29, 22, and 21, respectively). However, no specific risk factors were identified in boys that clearly segmented this group into a high risk of SA within the model. This result does not imply that there were no relationships between risk factors and suicidal attempt within the data but that the relationship was smaller, and the decision tree did not find a combination of variables that would allow for such precise segmentation. It should be noted that although the CTREE was computed considering all the independent variables, not all of them showed sufficient relevance to be selected in the final divisions. The variables not included in the tree were child-to-father violence classroom climate-teacher, classroom climate-peers, cyberbullying aggression, school bullying victimization and school bullying aggression. These variables are related to suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt, but their absence in the model indicated that their relevance was lower or redundant when the rest of the variables included in the model were taken into account. In summary, these results underscored the importance of considering family factors conjointly, such as parenting styles and child-parent violence, along with cybervictimization, partner relationships, and usage frequency of social media to gain an in-depth understanding of the risks associated with adolescents’ suicidality. The differences between boys and girls and between suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt, as well as the interaction between the different factors, were key elements in the formulation of risk profiles. Model Performance The predictive performance of CTREE was evaluated using cross-validation of 10 folds, general accuracy, and the AUC for each category of the dependent variable (NSI, SI, and SA). This approach ensured robust model evaluation by reducing the risk of overfitting. The model achieved an overall accuracy of 54.24%, indicating moderate performance. This accuracy was reasonable considering the inherent complexity of predicting suicidality in adolescents, where multiple risk and protective factors interact in subtle and sometimes overlapping ways. The model’s ability to discriminate between the dependent variable categories was evaluated using the AUC, whose values were .71 for NSI and SA. These results indicated that the model had a moderate ability to identify adolescents without suicidal ideation and those with suicidal attempt. Discriminatory capacity was lower for the category of suicidal ideation, with an AUC of .64, likely due to the complex and heterogeneous nature of the factors associated with this category. In conclusion, the model demonstrated moderate overall performance, with an increased ability to discriminate adolescents at the extremes of the suicidal spectrum, NSI and SA, and greater challenges in identifying those with suicidal ideation. The current study aimed to explore the key risk factors and their interplay to predict different stages of suicidality in adolescents considering gender. Potential predictors were selected based on previous findings from a developmental-ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), and a conditional inference tree analysis was applied to identify the most relevant predictors and how they interact in shaping suicide risk. First of all, it should be noted that gender emerged as a key factor in the model and that it already structured the prediction tree from the second node. Understanding this result was enriched by the data reported in the final nodes of the tree, where two subsamples of adolescents were classified because of their lowest levels in all risk factors and the lowest level in suicidal symptoms: while the subsample of boys with these characteristics comprised 420 participants, the subsample of girls only included 146. These results are consistent with previous literature, which found significant quantitative and qualitative gender differences in the analysis of adolescent suicidology (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019; Vivier et al., 2021) and suggested the need to differentiate between genders when analyzing adolescent suicide. Therefore, from now on, the results will be discussed with a focus on gender differences. The mother’s negative socialization style, in the first place, and the father’s, in second place, were the risk factors with the greatest relative importance in the model, compared, for example, with cybervictimization and social media usage frequency. This result indicates a greater importance of family variables in predicting suicide risk in adolescents compared to variables related to adolescents’ online environment, recently highlighted in studies on adolescent suicidology (see, for example, Jaycox et al., 2024; Macrynicola et al., 2021). From an ecosystem approach to human development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006), in the adolescent stage, the family, and especially the relationships with parents, is crucial in the children’s psychological adjustment. Parental socialization is the closest relational environment in which adolescents find affection, recognition, and support to develop self-regulation mechanisms, with significant consequences for internalizing symptomatology such as suicidal ideation (Estévez-García et al., 2023; Falcó et al., 2024; Gorostiaga et al., 2019). Moreover, our results indicated that the negative maternal style, characterized by a lack of affection, hostility, indifference, and rejection, was the factor that constituted the root node of the model for both genders. This meant that it was the strongest predictor of suicidality in the sample, both in boys and girls. This result was consistent with the idea that mothers probably continue to spend more time with their children (Cano, 2021) and that, in this context, maternal hostility, essentially linked to rejection, can emerge as one of the most pernicious factors of negative parenting, a trigger for internalized disorders, especially in daughters (Jiménez et al., 2024; McLeod et al., 2007). Delving into the role of the mother’s negative socialization style, we observed that this factor contributed significantly, in interaction with the online variables mentioned above, to specific high-risk profiles for suicide ideation and suicide attempt in girls. On the one hand, a moderate level of a mother’s negative socialization style predicted suicidal ideation in girls who used social media intensively (more than 5 hours per day); on the other hand, a high level of a mother’s negative socialization style predicted suicidal attempt when girls suffered cybervictimization (from low levels). In both profiles, the mother’s negative socializing style seemed to be a breeding ground for girls’ suicidality, whose effect is triggered in situations of problematic use of social media or being cybervictimized. These results report a complex interaction between family and online factors and may fill the gap identified by certain authors on how specific risk factors (e.g., hours of social media use) interact with contextual and individual vulnerabilities related to suicide risk in youths (Buelga et al., 2024; Jaycox et al., 2024). In this sense, although the factors related to adolescents’ online environment (cybervictimization and social media usage frequency) obtained the lowest relative weight in the predictive model, they were relevant when their role was interpreted within the framework of the tree drawn by the rest of the contextual variables. Furthermore, these results can be interpreted in light of the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model, where the relationship with the mother, characterized by the absence of intimate support, could act as a chronic stressor and the adolescents’ online problems as an acute stressor, jointly triggering feelings of entrapment that precede girls’ suicidal ideation and attempt. However, in boys we note the risk of being a cybervictim for the development of suicidal thoughts, even when no other risk factors were found in family or partner relationships. This result is consistent with previous studies that related the experience of being a cybervictim with increases in adolescents’ suicidal ideation (Estévez-García et al., 2023; Iranzo et al., 2019) and extended the comprehension of this risk relationship by focusing on boys who did not present risks in other areas of their lives. In addition, in our results, face-to-face peer bullying or victimization and cyberaggression were not selected by the multivariate model, which could reinforce the idea that cybervictimization has a specific weight in predicting adolescents’ suicide risk versus other forms of involvement in peer harassment (Katsaras et al., 2018; Massing-Schaffer & Nesi, 2020). After negative parenting styles and gender, the next key factor in predicting suicidal risk was having a partner. This result may be surprising given the protective effect that a partner relationship seems to have against the risk of suicide in adults. Indeed, in studies conducted with adults, both men and women, it has been found that being romantically unattached or unmarried were potential risk factors for suicide (Pirkis et al., 2000; Still, 2021). However, previous studies suggested that challenges related to romantic relationships in adolescents’ lives can contribute to the emergence of suicidal behavior (Gallagher & Miller, 2018; Jiménez et al., 2024). Indeed, inexperience in first relationships entails a dose of personal distress that, together with poor emotion-regulation skills, has been associated with conflictive dating relationships (Valdivia-Salas et al., 2021; Valdivia-Salas et al., 2023) and, consequently, with suicidal ideation and attempts (Barter & Stanley, 2016). Our results encouraged delving into the risk or protection role of adolescent couples according to gender. It seems that while for some boys, having a partner could have a protective effect in itself or in the context of negative parental socialization, for girls, having a partner is mainly associated with greater suicidal ideation. Although previous studies have analyzed gender differences in the potential impact of intimate partner relationships on suicidal thoughts and attempts, these analyses have been carried out with adults with inconsistent results (Kazan et al., 2016). Therefore, it is a field of study we need to continue deepening. Finally, after negative parenting styles, gender, and partner relationship, the variable of violence toward the mother was the next key factor for the prediction of suicide risk. The presence of child-to-mother violence was especially relevant for a girl’s suicidal ideation. This result extends the scarce previous evidence regarding the relationship between child-to-parent violence and suicidal behavior (Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2020; Suárez-Relinque et al., 2023) and placed the focus back on the mother-daughter relationship. Some previous studies have informed that mothers suffer violence from their children more frequently than fathers (Martínez et al., 2015; McElhone, 2017) and that girls perpetrating violence towards their parents have more suicidal ideation (Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2020; Suárez-Relinque et al., 2023). However, there are no comparative studies available that consider both aggressors and victims of child-to-parent violence in gender dyads, and more research is needed to analyze differences in these dyads related to children’s mental health outcomes (Russell & Saebel, 1997). Limitations and Future Research Overall, the results of this study contribute to a deeper understanding of the role of relational factors in the risk of suicide in adolescents from an eco-developmental approach. However, the authors acknowledge certain limitations that should be considered for future research. Firstly, the validity of our results is limited by the fact that adolescents who have died by suicide cannot be directly included in the studies. In this sense, the transition between suicidal thoughts, attempts, and effective suicide is not clearly established (Sveticic & De Leo, 2012), and, therefore, we focused on the two most relevant suicide risk indicators without referring to the probability of effective suicide. Secondly, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits establishing causality or directionality. This means that the decision tree cannot show causal relationships between predictors and outcomes. More broadly, decision trees are considered exploratory methods used for hypothesis generation (Battista et al., 2023). Longitudinal designs with measurements collected at different times (for example, over the four years of secondary education) would clarify transitions between different stages of suicidality and the directionality hypothesis. Also, the CTREE method used in this study does not account for the potential hierarchical nature of the data (i.e., students clustered within schools and classrooms). Future research should examine the nonindependence of the observations with the appropriate methods. Thirdly, another limitation of this study is the moderate overall model fit, indicating a moderate ability to correctly identify adolescents in the different stages of suicidality, especially adolescents in the SI group. This is probably due to the complex and heterogeneous nature of the factors associated with suicide risk and suggests that other intrinsic factors that are not captured in this study play an important role in predicting suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt, such as depression, which is already a well-established predictor (Battista et al., 2023; Iranzo et al., 2019). Our results regarding key predictors in boys were limited in this sense. We may have captured key factors for girls but not for boys, and therefore, further gender-differentiated research is needed to contrast potential differences in risk profiles. Finally, psychopathological assessment has not been considered in this study which may limit de interpretation of the results, and no generalization of conclusions can be made to institutionalized adolescents or outside the school system. Conclusions and Implications for Practice Despite these limitations, this work provides insights into key relational risk factors for adolescents’ suicidality and the interplay between them to obtain relevant information and guide prevention efforts. Empirical evidence has been found for different profiles for suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt depending on gender. Adolescent girls’ suicidal attempt has been fundamentally related to a family context characterized by a negative maternal socialization style in interaction with experiencing cybervictimization. Girls’ suicidal ideation has been related to having a partner, having a violent relationship with their mothers, perceiving some hostility, indifference, and rejection in their mothers, and using social networks intensively and daily. In boys, suicidal ideation has been fundamentally related to being cybervictimized, while no key factors for suicidal attempt have been found. These results suggest that the family is a key relational context in adolescent suicidology and that risk profiles are different depending on the type of risk indicator (i.e., ideation or attempt) and gender. Prevention strategies would require a multi-context approach with varied strategies to reach adolescents, particularly the most vulnerable, such as cybervictimized girls with a problematic relational context in their families. It is crucial to implement intervention protocols based on this evidence, ensuring appropriate and professional management of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts in health and educational settings. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Jiménez, T. I., Estévez-García, J. F.,, Musitu, G., & Estévez, E. (2025). Suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt in spanish adolescents: Risk profiles identified through decision tree analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 161-173. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a13 Funding This study was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, “Bullying and cyberbullying among peers and in adolescent couples: from emotional regulation to suicidal ideation" Research Project, grant number PID2019-109442RB-I00. Appendix Supplementary Materials Figure S1 Conditional Tree Model Predicting Suicide Eisk in Adolescents with High MNS   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA = suicidal attempt; MNS = mother’s negative style (1–4); CBV = cyberbullying victimization (0–3); GDR = gender. Figure S2 Conditional Tree Model for Predicting Suicide Risk in Boys with Low MNS.   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA = suicidal attempt; MNS = mother’s negative style (1–4); FNS = father’s negative style (1–4); CBV = cyberbullying victimization (0–3); HP = has partner; CPVM = child-to-parent violence towards the mother (0–3). Figure S3 Conditional Tree Model for Predicting Suicide Risk in Girls with Low MNS.   Note. NSI = no suicidal ideation; SI = suicidal ideation; SA = suicidal attempt; MNS = mother’s negative style (1–4); FNS = father’s negative style (1–4); CBV = cyberbullying victimization (0–3); HP = has partner; CPVM = child-to-parent violence towards the mother (0–3); SMUF = social media usage frequency, N = never, 0-1h: until 1 hour/day, 1-3h: from 1 to 3 hours/day, 3-5h: from 3 to 5 hours/day, + 5h: more than 5 hours/day. |

Cite this article as: Jiménez, T. I., Estévez-García, J. F., Musitu, G., and Estévez, E. (2025). Suicidal Ideation and Suicidal Attempt in Spanish Adolescents: Risk Profiles Identified Through Decision Tree Analysis. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 161 - 173. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a13

Correspondence: eestevez@umh.es (E. Estévez).

Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS