Peer Support in Chronic Conditions from the Peer Supporters’ Perspective: A Systematic Review

Annika Braun, Bernd Löwe, and Natalie Uhlenbusch

University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf, Germany

https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a14

Received 13 February 2025, Accepted 16 June 2025

Abstract

Objective: Peer support can be a valuable addition to routine care for patients with chronic conditions. While the benefits of peer support are well documented, most research has focused on the recipients’ perspective. Given the central role of peer supporters, their experiences should be considered equally important. This systematic review synthesizes the existing literature on the experiences of peer supporters with chronic conditions. Method: We conducted a systematic search across PubMed, PsycInfo (OVID), Psyndex (OVID), Web of Science and screened grey literature, citation and reference lists. Quantitative and qualitative studies reporting on the experiences of peer supporters with a somatic chronic condition were included. The qualitative synthesis followed a metaethnographic approach. Quantitative findings were summarized descriptively and risk of bias of all studies assessed. Results: Out of 9,144 papers identified, 72 were included, mostly qualitative and varying in quality. The synthesis revealed diverse experiences grouped into three categories. Benefits included meaningfulness of the role, skill development, personal growth, social inclusion, reciprocal support, employment advantages, and better disease management. Challenges involved organisational demands, emotional strain, difficult peer interactions, and unclear roles. Facilitators and suggested improvements concerned support, role clarity, setting, and counselling. Overall, the evidence indicates a slightly positive experience for peer supporters. Conclusions: Being a peer supporter is a multifaceted experience that offers various benefits while also presenting challenges. Incorporating peer supporters’ perspectives is essential to ensuring that peer-based programs benefit all parties involved, thereby maximizing overall impact. Practical implications for design and execution of future peer-based interventions are provided.

Keywords

Peer support, Chronic diseases, Chronic conditions, Peer supporter experiences, Systematic reviewCite this article as: Braun, A., Löwe, B., and Uhlenbusch, N. (2025). Peer Support in Chronic Conditions from the Peer Supporters’ Perspective: A Systematic Review. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 175 - 188. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a14

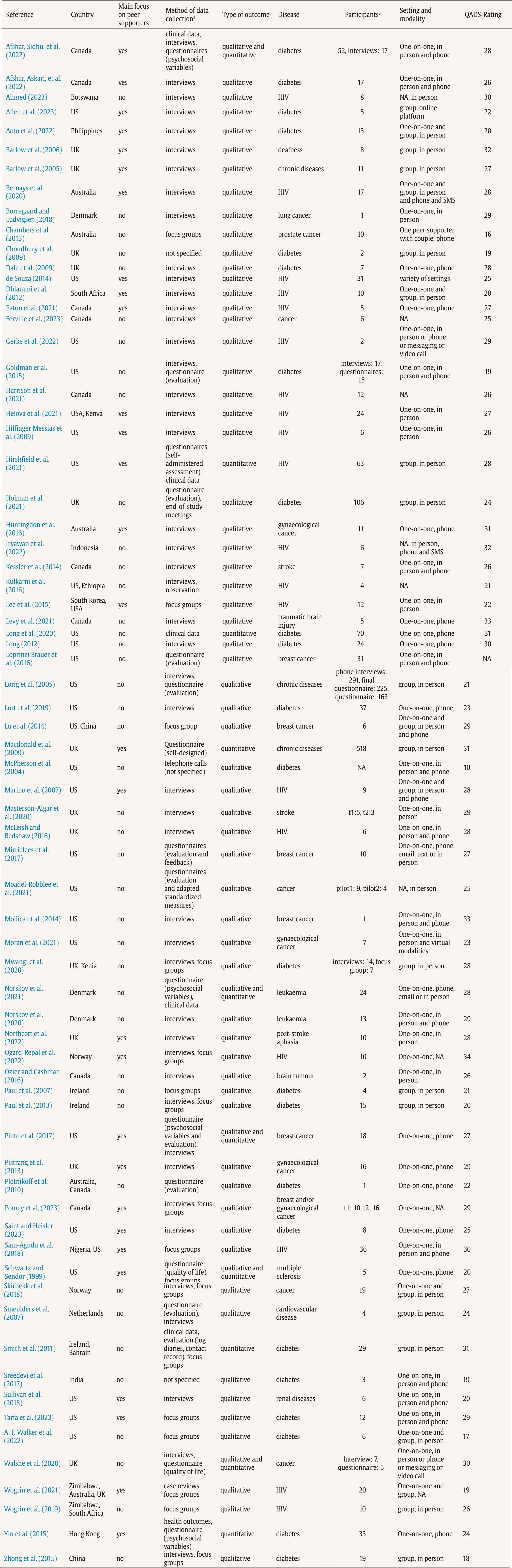

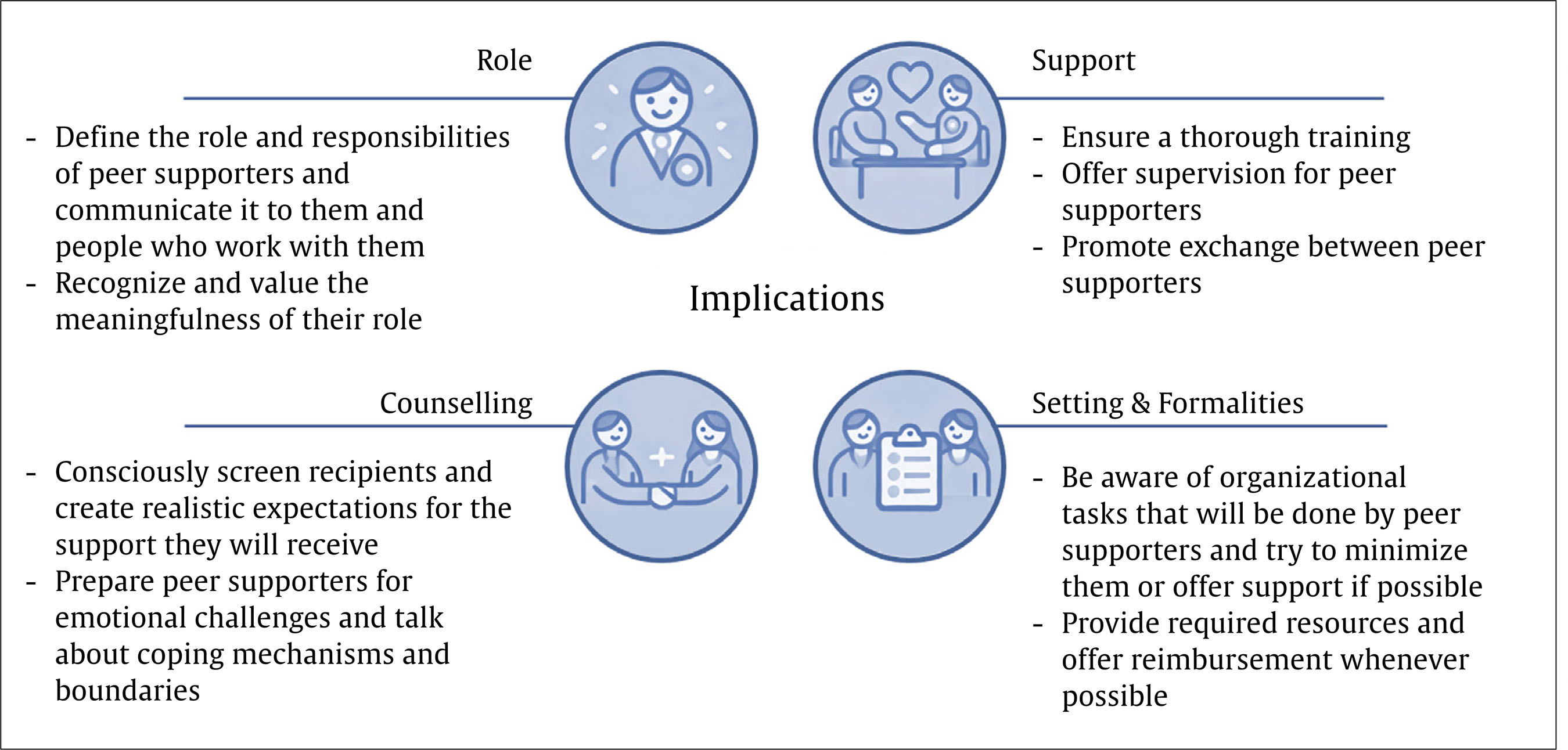

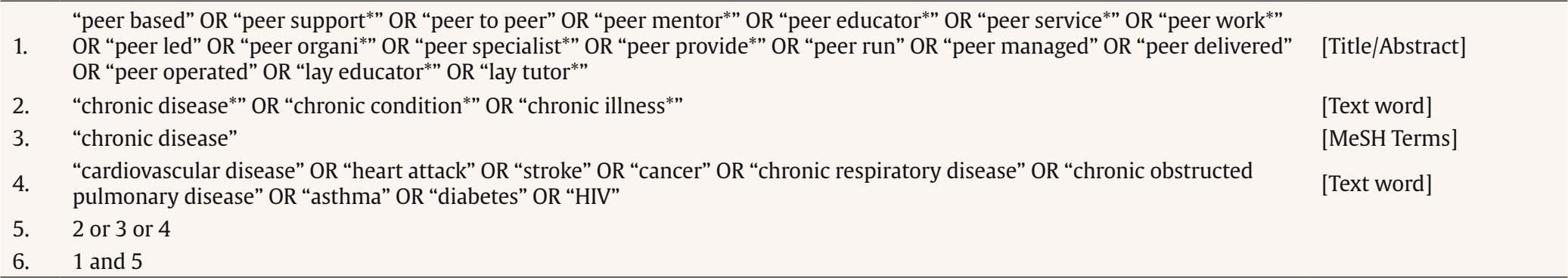

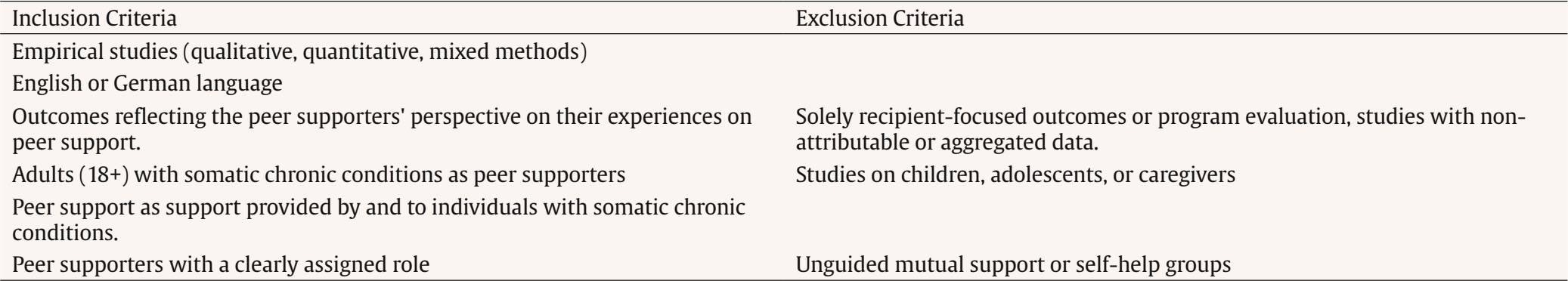

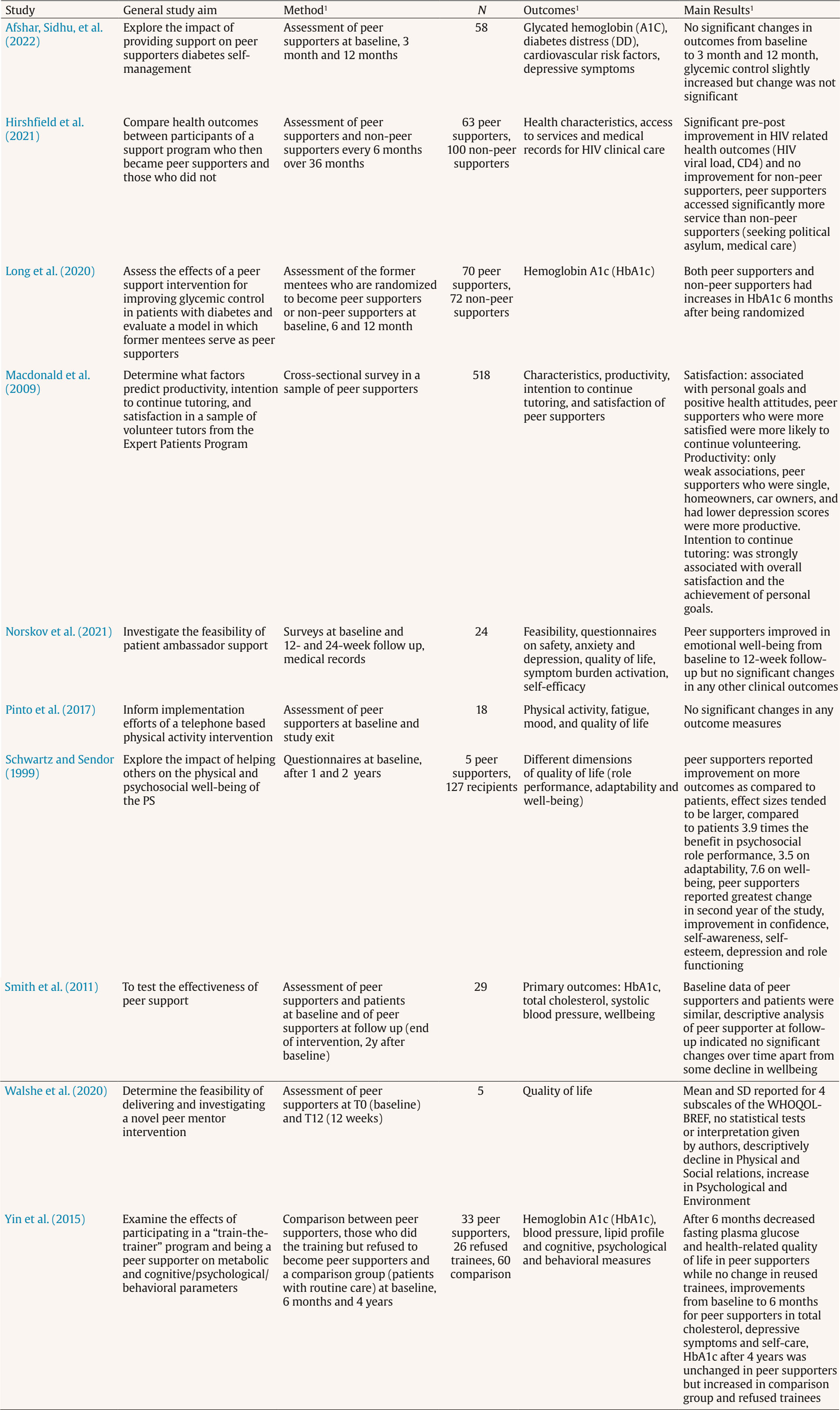

Correspondence: an.braun@uke.de (A. Braun).The global burden of chronic conditions and the pressing need for adequate and holistic care approaches have been frequently demonstrated (Akif et al., 2024; Das, 2022; Yach et al., 2004). With the global prevalence of chronic and non-communicable diseases continuing to rise (van Oostrom et al., 2014), this need is likely to become even more urgent in the future. Beyond their somatic implications, chronic conditions can affect multiple areas of daily life and present individuals with complex, ongoing challenges that require continuous adaptation. While some people live well with chronic conditions, studies have shown increased rates of depression and anxiety and a reduced quality of life (Megari, 2013), as well as an increased risk of loneliness (Petitte et al., 2015). As most people affected by a chronic condition only have very limited time with health care professionals, additional access to support outside of routine care is needed (Reidy et al., 2024). Peer-based interventions present an approach to support individuals across the diverse and complex dimensions of living with their chronic condition. To effectively address increasing demands for mental health care in the general population, Patel et al. (2023) suggest to make use of resources already available by expanding the health care work force to non-specialist providers. A special role amongst these have people with lived experience themselves, so-called peer supporters, also referred to as peer counselors, peer educators, lay tutors, and sometimes community health workers. Peer support, while lacking a universal definition, can broadly be described as support from people with the same or a similar disease. Peer supporters can therefore make use of their lived experiences to support others (Watson, 2019) and can significantly enhance the experience of care for those receiving the support (Repper, 2013). The kind of support is not limited to psychological support but can take various forms, such as social and practical support or assistance with behavioural changes (Thompson et al., 2022). Peer-based support can be provided using various settings and modalities such as face to face, online, in clinical or non-clinical groups, or through activities (Reidy et al., 2024). Evidence on the effectiveness of such interventions is mixed. Reviews on peer support in chronic condition often show positive trends, such as improvement in recipients’ quality of life, depression or distress (Thompson et al., 2022). Reviews in the field of mental health show improvements in, e.g., recovery outcomes or self-efficacy (Cooper et al., 2024). In both these umbrella reviews, the authors highlight the considerable potential of such interventions for recipients while at the same time concluding that consistent statistically significant results are hindered by insufficient high-quality primary research, also reflected in the absence of universal definitions, theories, or outcome domains. To ensure the success of peer support interventions, it is crucial to consider the impact on both recipients and those providing the support (Embuldeniya et al., 2013). Peer supporters, being individuals with a chronic disease themselves and usually not formally trained healthcare professionals, face challenges within the healthcare system, and understanding their experiences, are crucial for enhancing the effectiveness and sustainability of peer support programs, ultimately expanding benefits for themselves and for the recipients. For a long time, research has mainly focused on the recipient’s perspective, leaving a critical gap in understanding peer supporters' experiences. This gap is only beginning to be addressed. A recent umbrella review in mental health found both benefits and challenges for peer supporters, including improved recovery, well-being and social inclusion, but also role confusion, high workload and the feeling of their work not being sufficiently valued (Cooper et al., 2024). Whether these findings are applicable to peer supporters in chronic somatic diseases remains unclear. Reviews focusing solely on the peer supporter experience exist in areas such as mental health (Bailie & Tickle, 2015; Vandewalle et al., 2016; G. Walker & Bryant, 2013), HIV (Roland et al., 2022), and general health (MacLellan et al., 2015), highlighting a significant research gap in chronic condition settings. This review aims to provide an overview of the existing literature on the perspectives of peer supporters in the context of chronic conditions. By doing so, it seeks to enhance our understanding of peer supporters’ experiences and derive practical implications for future peer support programs in this field. We developed the research protocol of this systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). On June 17th 2023, it was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42023433068. Search Strategy We aimed to search for studies that report on peer supporters’ perspective on their experience of delivering peer support in the field of chronic diseases. Without there being a universally agreed-upon definition of peer support, for the purposes of this review and to maintain a clear scope, we defined peer support as support provided by and to individuals from the same peer group, with the peer group being defined as people diagnosed with a somatic chronic condition. The resulting search term was a combination of peer support and chronic diseases. For peer support, we identified multiple frequently used synonyms from existing literature (e.g., peer mentor, peer educator, peer-to-peer). For chronic diseases, we included the keywords “chronic disease”, “chronic illness”, or “chronic condition”, as well as MeSH terms and specific chronic diseases that are listed in the World Health Organization (WHO, 2023) definition of chronic diseases (cardiovascular disease, heart attack, stroke, cancer, chronic respiratory disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, diabetes). We additionally included HIV as a keyword, as the WHO also describes it as a chronic health condition. We used four electronic databases for the systematic search: PubMed, PsycINFO (OVID), Psyndex (OVID), and Web of Science. We adapted the search strategy to the available options in each database. Search strategies and search dates per database are provided as supplementary material in Appendix. We additionally did a hand search of the references of core papers, which were not formally predefined but were selected based on their close thematic relevance and richness of content as well as articles that have cited these papers. For grey literature, we searched the electronic databases of the State and University Library Hamburg and the German National Library for relevant dissertations. Searches were conducted between 30.06.2023 and 06.07.2023. The search strategy was discussed with and approved by an independent librarian. Eligibility Criteria All original empirical studies were eligible, including any study design (e.g., observational, interventional) assessing or evaluating peer support for chronic conditions from the perspective of peer supporters. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods were included, with no publication date restriction, but only studies in English or German were eligible. Population: adults (18+) with a somatic chronic condition providing any kind of peer support were included; in our definition, studies on children, adolescents, or caregivers were excluded. Intervention: peer support provided by and to individuals with somatic chronic conditions. No restrictions were placed on peer support types, level of experience, training, setting (one-on-one or group), formality, compensation, or modality (in-person or digital), nor on support goals. The peer supporter role had to be clearly assigned, excluding unguided self-help groups and mutual dyadic counselling. Outcome: all outcomes reflecting the peer supporters' perspective on their experience of delivering peer support (e.g., benefits, effects, experiences, barriers, facilitators) were included, while outcomes focused solely on program evaluation or recipient experience described by peer supporters were excluded. Studies reporting on both were eligible for inclusion but only data on peer supporters’ perspective was extracted later on. Outcomes had to be clearly assignable to the peer supporter. Therefore, studies presenting aggregated data from multiple stakeholder groups or unattributed qualitative findings were excluded. For a concise overview, see Table 1. Selection Process We imported all identified studies into the EndNote 20 literature program. After removing duplicate records, we imported the remaining studies into the Rayyan open access literature screening program (Ouzzani et al., 2016). One author (AB) conducted a title and abstract screening. Using the predefined eligibility criteria, studies that met an exclusion criterion were removed. Potentially relevant or unclear studies were further evaluated in a second screening round. For that, two authors (AB and NU) independently conducted a full text screening and documented reasons for exclusion. We discussed unclear cases and disagreements until a mutual decision could be found. We piloted the screening process on approximately 10% of the studies eligible for full text screening and discussed the decisions. Data Extraction and Data Synthesis AB repeatedly read the included records to familiarise herself with the data. Data from all included studies were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet, including information on study characteristics, methods, participants, intervention design, and relevant qualitative and quantitative outcomes as reported in the results section. Data extraction was done by AB and proofread by a research assistant (CVP). Without there being consensus on a universally used method for synthesising qualitative data, we based our approach on the principles of metaethnography (Noblit, 1988). This frequently used approach was deemed most suitable due to its aggregative, rather than interpretative, nature as it systematically combines and organizes findings, while still creating a higher-level understanding of the topic. For this review, we employed a tailored procedure. First, key themes were inductively drawn from the qualitative findings as reported in the results section. To integrate findings across studies, initial themes and categories were compared, merged and redefined while remaining open to new emerging themes. Given the lack of an established standard for ordering studies (Atkins et al., 2008), we analyzed them step by step in alphabetical order by first author to ensure a structured comparison. Finally, themes were organized into subcategories and categories. Due to the few quantitative results found, there were no statistical analyses performed. Quantitative results are reported descriptively. Quality Assessment A quality assessment was performed for all included studies to assess the risk of bias using the Quality Assessment for Diverse Studies (QuADS) (Harrison et al., 2021). This tool was considered eligible for this review due to its ability to assess diverse study designs. It has shown substantial interrater reliability and content validity and is publicly available (Harrison et al., 2021). The QuADS tool consists of 13 questions, which are each rated on a scale from zero to three, resulting in possible score between zero and 39, where higher scores indicate better quality (further information is provided as in Appendix). Two reviewers (AB and research assistant CVP) independently rated each included study. This process was piloted with a sample of five studies. One record, a letter to the editor, was excluded from rating, as the selected tool was deemed not suitable for this type of publication. Disagreements were discussed afterwards until a mutual decision was reached. Interrater reliability was calculated using quadratic weighted kappa, as this measure accounts for the ordinal nature of the categories and assigns greater weight to larger disagreements. In accordance with the QuADS manual, no studies were excluded based on their quality but results are reported and discussed. Study Selection Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of identification, screening, and inclusion according to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. A total of 9,134 records were identified via database searching; 4,079 duplicates were removed and 5,055 title and abstracts were screened; 574 articles were eligible for the full-text screening, through which 503 articles were excluded. Interrater reliability was substantial, with a kappa of κ = .80. Approximately 5% of the studies (n = 29) were deemed inconclusive and resolved through a joint discussion. We identified an additional 10 studies via hand search, none of them meeting all inclusion criteria. We could not identify any relevant studies via grey literature search. Therefore, 71 studies were included in this review. Study Characteristics An overview on study characteristics can be found in Table 2. Included records were published between 1999 and 2023 and originate from 21 different countries, with the majority being from the United States. Of the studies, 29 studies focused primarily on the perspective of peer supporters, while 42 studies reported on peer supporters as a non-primary outcome. The most common method to examine the peer supporters’ perspective was interviews, used in 47 studies. Other methods included focus groups, questionnaires, health related measures, unstructured evaluation or recordings. The number of subjects per record ranged from one to 518 (survey), with approximately three-quarters of the records (n = 54) involving less than 20 subjects. Diabetes (n = 23), HIV (n = 19), and different types of cancer (n = 18) were the most commonly studied chronic conditions. Other areas of conditions were cardiovascular disease, deafness, multiple sclerosis, aphasia, renal disease, stroke and traumatic brain injury. Three records reported on disease unspecific interventions for chronic conditions. The level of detail used to describe the peer support interventions varied widely, not allowing a structured comprehensive overview. However, most records described the modality used for delivering the intervention and whether it was done one-on-one or in groups. Specifically, 40 records report on one-on-one interventions, 15 on support groups (led by a peer-supported), eight used a combination of both, one had one peer supporter with two recipients, one used various settings, and six did not specify. Most interventions took place in person (n = 27 studies), while 14 took place via phone and 22 used a combination of modalities. Eight studies reported on other modalities, such as online platforms, video calls or text messages or did not specify. In addition, while detailed descriptions were often lacking, the available information regarding peer supporters and the support they provided can be summarised as follows. As per definition, all peer supporters were individuals with a chronic condition. A common criterion for participation was being well adjusted to the disease, and in some cases, they were former recipients of peer support themselves. Roles ranged from volunteer positions to paid employment or smaller reimbursements, with varying levels of time commitment. Peer support was often but not exclusively delivered as part of a research project. In these cases, the duration of support was typically predefined by the study protocol, ranging from a few weeks to over a year. The goals of support varied widely, including but not limited to improving mental health, promoting disease acceptance, providing disease education, offering social support, assisting with navigation of healthcare or social systems, teaching self-care skills or encouraging physical activity. Table 2 Characteristics of Included Studies   Note. 1Method of data collection used to assess outcomes related to peer supporters. 2Number of peer supporters for whom outcomes were reported. Quality Assessment Total QuADS scores per study are displayed in Table 2. A detailed overview on ratings per category is provided as Supplementary material in Appendix. The quality of the included studies varied widely according to the QuADS criteria, with total scores per study ranging from 10 to 34. Studies reporting qualitative outcomes of peer supporters had the lowest average ratings (n = 60, M = 25.25, Mdn = 26, SD = 4.81), followed by mixed-methods studies (n = 5, M = 26.80, Mdn = 28, SD = 3.96), while studies with exclusively quantitative results received the highest ratings (n = 5, M = 29.00, Mdn = 31, SD = 3.08). Across all studies, lowest ratings were observed in the following categories: reporting the rationale for choice of data collection tools, justification of selection of analytical methods and evidence for the consideration of different research stakeholders. Relatively weak ratings were also noted for the description of data collection procedures and recruitment data as well as appropriate sampling, due to outcomes related to peer supporters often being reported only briefly or as secondary outcomes. Interrater reliability was substantial, with a quadratic weighted kappa of κ = .75. Qualitative Synthesis Sixty-six of the included records reported qualitative results. The amount of data extracted from each record varied widely, with some studies focusing on the peer supporter perspective and other studies only reporting a few sentences that were eligible for this review. The analysis of the extracted data led to 91 themes, which were further sorted into 15 subcategories. The themes emerging from the data showed that the reported perspectives of peer supporters can be grouped in benefits of being a peer supporter, challenges of being a peer supporter and facilitators and wishes for change, leading to these forming the 3 main categories. An overview on all themes, subcategories and categories with referring studies is provided as Supplementary material in Appendix. In addition, the analysis revealed an overarching category reflecting the overall experience of peer supporters, based on 38 studies that reported this aspect. No further subcategories were developed here. Overall Experience Of the 38 studies mentioning an overall experience of peer supporters, 34 described it with positive adjectives such as satisfying, enjoyable, meaningful, beneficial, rewarding or positive. The other four studies described a polarity in the experience such as positive and challenging or beneficial and challenging. No studies described the overall experience using only adjectives with negative connotations. Benefits of Being a Peer Supporter We identified seven subcategories that were commonly mentioned as benefits of being a peer supporter: Meaningfulness of the peer supporter Role, Improvement of Skills, Personal Development, Social Inclusion, Reciprocal Support, Employment Benefits, and Improved Disease Management. Meaningfulness of the Peer Supporter Role. Many peer supporters found the act of helping others to be satisfying, enjoyable, and rewarding. They valued the opportunity to engage in work that makes a difference in others' lives, provides a sense of purpose and meaning and is perceived as valuable. Additionally, peer supporters reported feeling valued and recognized (e.g., by peers, healthcare professionals or the community). Being a peer supporter fulfilled their desire to use their own experiences as patients and to give back to their community. The pride in their work and the ability to witness the success of others, in which they played a part, were also highlighted as benefits. Improvement of Skills. The most frequently mentioned improvements were in skills directly related to peer supporter tasks. Often described broadly as peer-support-related skills, these include interpersonal skills, presenting, speaking on the phone, and caregiving. Some studies specifically noted improvements in empathy, such as better understanding others, as well as enhanced communication skills, including listening, talking, and handling difficult conversations. These skills were often directly applied in their peer support activities. Personal Development. Personal development included an increase in confidence and self-esteem, a sense of empowerment, and a feeling of strength. Personal growth was also mentioned, along with the acquisition of knowledge and wisdom, a sense of inner peace, and feelings of gratitude (e.g., for their own progress or the ability to help others). Many peer supporters experienced a shift in perspective, particularly regarding their own disease, as interacting with others and learning about their experiences often provided a broader outlook and helped them contextualize their own experiences. Social Inclusion. Peer supporters frequently mentioned the advantages of building new connections, expanding their social networks, and creating a social support system through their role, especially with people who share similar lived experiences or health conditions. Many reported a reduction in feelings of loneliness or isolation and enjoyed meeting others with the same condition. Some described it as finding a group, to which they belonged, particularly appreciating the acceptance they received from others. Reciprocal Support. While the primary aim of peer support is to provide help to recipients, many peer supporters reported that they, too, received support. Whereas often not specified further, some studies describe it in a way of sharing knowledge and experiences from both sides. Peer supporters noted that they learned from both their peers and other peer supporters they worked with. This mutual exchange was seen as enriching and motivating. Benefits of Employment. Being a peer supporter also comes with employment-related benefits. For some that meant receiving a financial reimbursement for their work, which especially in lower socio-economic contexts was of big importance for the peer supporters. Beyond financial aspects, having a task provided a sense of productive engagement and increased activity. Some mentioned that their role improved their employability for future jobs. The benefits of employment were also mentioned in a context of previously being limited due to the chronic condition. Improved Disease Management. Being a peer supporter was linked to improvements in managing their own disease. Peer supporters reported personal benefits from the interventions they delivered, often adopting the techniques they taught or making positive lifestyle changes by applying the program’s content in their own lives, which enhanced disease management and compliance. Being a peer supporter also increased disease-specific knowledge and encouraged self-reflection, promoting awareness of poor disease management’s consequences and motivating better health practices. Some peer supporters experienced greater acceptance of their condition, a sense of closure, and improvements in general or emotional well-being. Challenges of Being a Peer Supporter We identified four subcategories that describe challenges of being a peer supporter: Organisational and Operational Demands, Interaction with Peers, Personal and Emotional Challenges, and Role Definition and Team Integration. Organisational and Operational Demands. Some studies report general organizational tasks like administration, paperwork, and logistics, while others highlight specific challenges. Coordinating appointments for calls, meetings, or sessions often posed issues, including contact difficulties, scheduling conflicts, cancellations, and limited availability of interventions. In some cases, peer supporters were involved in patient recruitment, which was also mentioned as challenging. Additional obstacles included commuting, especially difficult for those with severe chronic conditions (e.g., due to fatigue, mobility issues), sometimes compounded logistical or financial difficulties. Venue arrangements and remote counselling through phone-based modalities presented further challenges. Peer supporters also faced issues with co-working, adhering to protocols, inadequate reimbursement, insufficient program funding, and perceived undervaluation of their roles. Unforeseen factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or natural disasters, added complexity to these challenges. Interaction with Peers. Peer supporters often encountered “difficult” or “challenging” interactions with peers. Despite the supportive nature of their role, they sometimes faced peers who were less engaged, lacked motivation, or showed reluctance, especially in peer support programs that followed a structured and predefined format. This included issues such as nonadherence, ignored advice, disinterest, or misaligned goals. Managing peers in poor mental states was also challenging, as peer supporters felt unprepared for these interactions and unsure how to support mental health concerns and felt concerned for their peers. Handling frustrated or angry peers, often due to unmet expectations, was another challenge. Group settings posed further difficulties, as peer supporters found it hard to address the varied needs of all patients. Ending the counselling relationship in programs with a predefined duration and structure was especially difficult, as was dealing with peer health deterioration or death. Some peer supporters also reported “mismatches” when they felt a poor personal fit with certain peers. Personal and Emotional Challenges. Peer supporters often felt overwhelmed by the extent of problems, emotions, responsibilities, or tasks (e.g., emotionally intense stories, complex needs, or high expectations). A strong sense of responsibility for peers led to feelings of disappointment, pressure, or emotional involvement, especially in challenging cases. Setting and maintaining boundaries and determining the level of involvement were significant challenges, requiring complex negotiation between personal and professional roles. Some peer supporters experienced emotional distress and difficult emotions from their tasks. Acting as a peer supporter could also serve as a “trigger” for painful memories of their own disease, as they listened to or shared stories. Insufficient training for these emotional challenges was occasionally mentioned. Some peer supporters struggled with confidence, doubting their ability, knowledge, or fearing mistakes. In disease-specific contexts like HIV, involuntary disclosure was also a challenge, particularly when participation in the program made their condition visible or identifiable. Role Definition and Team Integration. As the role of a peer supporter is not universally defined, many peer supporters struggled to understand their own role and therefore their scope of work and responsibilities. Occasionally peer supporters experienced role ambiguity. This also showed in challenges of finding their place within teams. Some peer supporters described experiencing major problems with the integration into health care teams, which showed in poor communication, limited exchange or strained relationships with other health care workers. Issues of recognition and valuation, both formal and informal, were also reported, with some peer supporters feeling undervalued or unrecognized by their teams or health care professionals. Facilitators and Wishes for Change Facilitators and wishes for change by the peer supporters regarding their role were identified in four key areas: Support, Role, Setting and Formalities, and Counselling. Support. A frequently mentioned facilitator was the support peer supporters received from staff, including study personnel, coordinators, and health care professionals. Organizational support and the availability of supervision, whether one-on-one or in groups, were mentioned. Some peer supporters expressed a desire for more support. Another critical factor was the exchange with other peer supporters. Sharing experiences, successes, and particularly challenges with others in similar roles was a significant resource for many peer supporters, regardless of whether this occurred in a structured or unstructured context. Role. A clear role description served as a facilitator, helping peer supporters understand their responsibilities and scope of work. However, some peer supporters expressed a desire for greater acknowledgment and recognition of their role, including societal and structural recognition of their role. Setting and Formalities. We identified some contradictory findings regarding the setting and formalities. While some peer supporters found the presence of structure and guidelines (such as manuals or protocols) helpful, others expressed a wish for more flexibility. Similarly, while some peer supporters viewed phone-based counselling as a facilitator, others expressed a preference for alternative modalities, such as video calls. There was consensus on the importance of training and compensation, both of which were seen as desirable factors. Inadequate or absent provision in these areas was frequently mentioned as needing improvement. Counselling. For the counselling or interventions themselves, peer supporters found that knowledge of coping strategies and the ability to apply them facilitated their work. A shared identity and similarities with their peers, inherent to the nature of peer support, were also mentioned as facilitators. Additionally, certain characteristics of peer supporters, such as empathy, were occasionally mentioned as useful attributes. Some peer supporters expressed a desire for improvements in matching processes (to better align peer supporters and peers), better screening of peers, and the creation of realistic expectations in peers. Quantitative Results Ten included records reported quantitative results on peer supporters, with five reporting only quantitative outcomes and the other five providing both quantitative and qualitative results. A table with a detailed overview is provided as Supplementary material in Appendix. The findings present a mixed picture. Eight studies assessed potential effects of providing peer support. Of these, three studies reported no relevant changes in the assessed outcomes, four studies showed improvements, and one study reported a deterioration. More specifically, the three studies without relevant changes assessed outcome measures, such as glycaemic control, cardiovascular risk factors and psychosocial constructs (such as depressive symptoms, fatigue, mood, quality of life) (Afshar, Sidhu, et al., 2022; Long et al., 2020; Pinto et al., 2017). In contrast, four studies found significant improvements in at least one reported measure, including HIV and diabetes related health outcomes, emotional wellbeing, self-care, depression symptoms, adaptability and well-being (Hirshfield et al., 2021; Norskov et al., 2021; Schwartz & Sendor, 1999; Yin et al., 2015). Notably, Schwartz and Sendor (1999) reported that peer supporters experienced greater improvements in quality of life than the intervention participants. Yin et al. (2015) found that HbA1c levels remained stable in peer supporters over four years, whereas a matched control group without peer support roles showed deterioration. Only one study reported on negative effects: While clinical measures remained unchanged, well-being declined over time (Smith et al., 2011). Two additional articles focused on other aspects of the peer support role. Macdonald et al. (2009) used factor analysis to show that personal goals, improved health, and altruistic motives predicted satisfaction among peer supporters. Those who were satisfied and driven by personal goals were also less likely to leave the role. Lastly, Walshe et al. (2020) descriptively reported pre-post values of quality of life measures, but did not perform statistical analysis or contextualize their results. This review aimed to synthesize existing literature on the experiences of peer supporters in the context of chronic conditions. The majority of studies reported on qualitative outcomes and their quality varied widely. Through a qualitative synthesis and a descriptive summary of quantitative results, we identified a range of benefits, challenges, facilitators, and wishes for change. Through a qualitative synthesis and a descriptive summary of quantitative results, we identified a range of benefits, challenges, facilitators, and wishes for change, reflecting the complex nature of peer supporters´ experiences. The synthesis of findings reveals that peer supporters generally describe their role as fulfilling, with most emphasizing the sense of meaning and satisfaction it brings. Many highlighted the personal development they experienced, from enhanced skills in communication and empathy to a stronger sense of self-worth and empowerment. Social inclusion was another key benefit, with peer supporters reporting a reduction in isolation and a sense of belonging within a community. Additionally, the role often led to improvements in disease management, as many adopted healthier behaviors and increased disease-specific knowledge. However, challenges were also evident. Organizational demands, such as administrative tasks and logistical difficulties, created significant strain, especially when paired with emotional challenges from managing peers with complex needs. A lack of clarity around their role, as well as integration issues within healthcare teams, further complicated the experience. Despite these obstacles, peer supporters identified several facilitators that made their work more manageable. Clear role definitions, supportive relationships with staff and peers, and access to appropriate training were all seen as crucial for success. Many also expressed a desire for more support, greater recognition of their work, and better resources for managing the emotional demands of their role. The variety of evidence in the literature clearly demonstrating that being a peer supporter offers various benefits is consistent with findings from earlier reviews in mental health (Bailie & Tickle, 2015; Cooper et al., 2024; Repper & Carter, 2011) and general health (MacLellan et al., 2015). Peer supporters appear to benefit from interventions in many ways similar to those who receive them. Social connectedness, a key aspect of peer-based interventions (Lauckner & Hutchinson, 2016; Watson, 2019), seems to be equally important for the peer supporters by fostering social interactions and support networks. Peer supporters also gain knowledge about their own condition, which helps them better manage their disease, similar to benefits seen in participants (Weingarten et al., 2002). That benefits for patients seem to extend to peer supporters is also reflected in the frequent description of the experience as “reciprocal support”. The distinction between the recipient and the provider of support may not be as clear-cut as initially assumed in the design of such interventions. In addition, the peer supporter role offers unique benefits, with a central factor being the sense of meaningfulness. Helping others and making an impact is described as a rewarding experience, often driven by altruistic motives. Previous research has shown that helping others can indeed lead to personal benefits (Jenkinson et al., 2013; Meier & Stutzer, 2007; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010). Along with this, peer supporters experience personal gains, such as greater confidence, enhanced self-esteem, empowerment, and the development of new skills. Furthermore, for individuals with chronic conditions, being a peer supporter can fulfill employment-related needs, which may be unmet due to the limitations of their condition. While experiencing benefits, peer supporters simultaneously face various challenges in their roles. These challenges are reflected in their feedback and highlighted as areas for improvement, while effective solutions can turn them into facilitators. Our results show that peer supporters find themselves balancing the role of being a patient and taking on health care tasks. Unlike health care professionals, peer supporters typically receive only basic training and are often laypeople in this domain. The ambiguity of their role also shows in the lack of a clear definition for their role and scope of work, leaving their place in the health care system vague. This can cause confusion for peer supporters and lead to communication issues within teams or lack of recognition. Similar concerns have also been raised in other health contexts, reinforcing our finding that clearer role definitions are essential to support peer supporters’ confidence and sense of competence (Cooper et al., 2024; MacLellan et al., 2015). We further showed that, organizational demands, such as scheduling and commuting, can be overwhelming for peer supporters, especially since many of them occupy low-paid or voluntary positions while living with a chronic illness and potentially having physical or mental limitations. They also faced emotional challenges presented through their tasks. The emotional strain of working with individuals in distress may be particularly difficult for lay people, who must balance their personal struggles with their new responsibilities and establish boundaries. Reported risk factors for compassion fatigue include fewer healthcare qualifications and less experience, which highlights the particular vulnerability of peer supporters in this regard (Sinclair et al., 2017). Challenges are compounded by a lack of resources, often reflected in inadequate or absent compensation for the peer supporters´ work. Providing compensation can also serve as recognition and appreciation for their time and effort (Lammers et al., 2022). The available evidence does not allow to make a definitive statement about whether the overall experience of being a peer supporter is positive or negative. At the same time, the findings point to a complex and multifaceted experience that goes beyond a simple positive–negative dichotomy. This complexity does not preclude peer supporters from finding their role meaningful or rewarding, nor does it diminish the value of what can be learned from their experiences. Still, there is a slight trend suggesting that the experience tends to be beneficial. Studies that describe an overall experience have almost exclusively used very positively connoted language, which is also reflected in the numerous benefits that were reported. This is further supported by the available quantitative data, which generally paints an either neutral or positive picture, with one included study even suggesting a higher impact on peer supporters than participants. It can be assumed that people who are selected or work as a peer supporter are already better adjusted to their disease than people seeking help. This is important to consider in the interpretation of quantitative results as the potentially better baseline measures of peer supporters can lead to glass ceiling effects (Norskov et al., 2021; Pinto et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the study showing a decline in well-being for peer supporters highlights their demanding role and the importance of paying attention to challenges. It has previously been shown that for peer supporters working in mental health their role also comes with a risk of impeding personal recovery, which nevertheless can be reduced by offering a supportive setting (Bailie & Tickle, 2015). Implications There is a need for further recognition and awareness of peer support as a valuable service. Increased awareness could, in turn, lead to more resources being allocated to peer support programs. An initial step lays within a clearer definition of peer supporters’ position within the healthcare system. While some peer supporters might bring relevant educational or experiential backgrounds, many are not formally trained healthcare professionals, often referred to as lay people. This diversity highlights the crucial role of comprehensive and adequate training, which should not only cover practical skills but also emotional resilience, boundaries, and coping strategies for dealing with challenging situations. Even though this review does not offer specific recommendations for the content of such training due to the variability in its description and evaluation across studies, the importance of training as a facilitator is evident. Another key form of support should come in the form of supervision or intervision. This is essential to offer peer supporters a reflective space to discuss emotional triggers, self-care, and challenges they encounter, ensuring they have the necessary support to manage their role effectively. Such support structures are common practice in mental health services and psychological care, and may be even more critical for laypeople involved in peer support (Lauckner & Hutchinson, 2016; Patel et al., 2023). The relevance of self-care practices and boundaries for peer supporter has previously been highlighted in the field of HIV (Roland et al., 2022). A further essential step in supporting peer supporters is to ensure that their roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, and expectations are openly communicated to them and those they work with. This clarity helps prevent role confusion and ensures that peer supporters feel confident in their responsibilities. While particularly important in structured programs, some degree of role definition may also be helpful in more informal settings to provide orientation and prevent misunderstandings. By considering peer supporters as an integral part of the intervention design, there is an opportunity not only to make this role more attractive but also to enhance the peer supporters’ well-being. Building on the findings of this review, the following recommendations as displayed in Figure 2 can guide the integration of peer supporters into the design and execution of future peer-based interventions. Figure 2 Implications for Integrating Peer Supporter into the Design and Execution of Peer-based Interventions.   Limitations and Future Research A key limitation is the varying and general rather low quality of the included studies, which introduces a potential risk of bias. Although the QuADS tool was used to assess for this, it did not account for the limited detail in reporting secondary outcomes, which were often the focus of this review. This may have contributed to the higher QuADS ratings observed for quantitative or mixed methods studies, as the experiences of peer supporters were more frequently examined as a primary outcome in these studies. Consequently, QuADS ratings may not fully reflect the relevance of the evidence. While following recommendations of the QuADS not to exclude studies based on quality, the results of this review rely more heavily on the higher quality studies, as these also tended to offer more themes within the synthesis. Studies of lower quality tended to support already identified topics rather than presenting new ones. While all included studies reported on the experiences of peer supporters, the support programs they were part of were often described superficially, with important details missing. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn on how certain program characteristics affect peer supporters. The formality of peer support likely has a substantial impact on how the role is experienced. This dimension might be underrepresented in our review, as studies tend to focus on interventions with at least some degree of structure, and fully informal peer support may be less frequently studied. Available data revealed significant heterogeneity in intervention characteristics, such as duration or frequency, diseases, impairment and cultural and socioeconomic contexts. While this heterogeneity must be considered, consistent themes across studies suggest the peer supporter experience may be largely universal. Moreover, this review primarily relies on qualitative data and its synthesis. Despite employing an aggregative rather than interpretative approach, the findings remain somewhat subject to the interpretation of the primary authors, as well as the interpretation within this review. We aimed to minimize bias through ongoing reflexivity. We acknowledge that all authors are involved in a research project on peer support, which may have influenced the interpretation of peer supporters’ experiences. To address this, two of the authors (AB and NU) were involved in coding and theme development, with regular discussions to reach consensus and minimize individual bias. Additionally, data extraction was independently verified by a research assistant. Despite these measures, the subjective nature of qualitative research should be considered when evaluating the conclusions. While grey literature was considered in the search, the strategy focused on selected sources and yielded no additional records. Given the experiential nature of the topic, it is possible that further relevant insights and authentic narratives of peer supporters exist in broader grey literature. Future research should focus on the effects of delivering interventions on peer supporters, with high-quality quantitative and mixed-method studies using standardized measures. Equal consideration should be given to peer supporters alongside participants, and outcome assessments should include their experiences. Evaluating the effectiveness of existing training programs could support the development of evidence-based training tailored to peer supporters’ needs. In addition, peer support may also represent a relevant and promising area for caregivers, whose experiences and needs warrant further investigation. Conclusion This systematic review examined the experiences of peer supporters in the field of chronic conditions. While it does not definitively conclude whether serving as a peer supporter is primarily beneficial or challenging, it rather shows the complexity of their role and provides valuable insights into their experiences and highlights the potential of their role. Peer supporters occupy a dual role. As patients themselves, they benefit from interventions in ways similar to recipients, complemented by unique benefits of their role, such as the meaningfulness of their work. However, they also take on health care provider roles, facing the challenges of this responsibility. This unique nature of their role introduces additional difficulties, such as ambiguity regarding their position within the health care system. Good training and substantial support from professional health care providers is therefore indispensable. Despite these challenges, this review demonstrates the significant potential of the peer supporter role. If we succeed in designing peer-based interventions in a way that effectively addresses the potential challenges and incorporates key facilitators, the role of peer supporters could become even more beneficial. Moreover, the benefits of such interventions could extend beyond participants to positively impact peer supporters as well. Practical implications for integrating peer supporters into the design of future interventions were identified. The review also revealed a critical gap in the structured research of the peer supporter role, particularly in the context of quantitative research. Although peer support interventions are increasingly being studied, the perspective of peer supporters remains underrepresented. This not only limits our understanding of their role but also contributes to the continued undervaluation of peer supporters and their recognition as a legitimate and professional component of healthcare. Future research should prioritize high-quality quantitative studies that incorporate the views of peer supporters. It is crucial to equally consider the perspectives of peer supporters not only in research but also in the design, implementation and execution of peer-based interventions. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements We thank our former research assistant and working student, Christina von Palubicki, whose support was indispensable for this paper. We would further like to thank Norbert Sunderbrink for his valuable support in developing the search strategy. Cite this article as: Braun, A., Löwe, B., & Uhlenbusch, N. (2025). Peer support in chronic conditions from the peer supporters’ perspective: A systematic review. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 175-188. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a14 Appendix Supplementary Materials Database Searches, Search Terms, and Dates a) PubMed Search conducted on June 30, 2023   (“peer based”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer support*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer to peer”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer mentor*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer educator*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer service*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer work*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer led”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer organi*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer specialist*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer provide*”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer run”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer managed”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer delivered”[Title/Abstract] OR “peer operated”[Title/Abstract] OR “lay educator*”[Title/Abstract] OR “lay tutor*”[Title/Abstract]) AND (“chronic condition*”[Text Word] OR “chronic disease*”[Text Word] OR “chronic illness*”[Text Word] OR “chronic disease”[MeSH Terms] OR “cardiovascular disease”[Text Word] OR “heart attack”[Text Word] OR “stroke”[Text Word] OR “cancer”[Text Word] OR “chronic respiratory disease”[Text Word] OR “chronic obstructed pulmonary disease”[Text Word] OR “asthma”[Text Word] OR “diabetes”[Text Word] OR “HIV”[Text Word]) b) PsycINFO & Psyndex (OVID) search PsycINFO search conducted on June 30, 2023 Psyndex search conducted on July 6, 2023

c) Web of science search Search conducted on June 30, 2023 Description and Ratings according to the QuADS Tool The full description of the QuADS tool including a thorough description of the criteria and how each criteria is rated is available here: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06122-y QuADS Criteria, rated from 0 to 3 with 3 being the highest rating Theoretical or conceptual underpinning to the research Statement of research aim/s Clear description of research setting and target population The study design is appropriate to address the stated research aims/s Appropriate sampling to address the research aim/s Rationale for choice of data collection tool/s The format and content of data collection tool is appropriate to address the stated research aim/s Description of data collection procedure Recruitment data provided Justification for analytic method selected The method of analysis was appropriate to answer the research aim/s Evidence that the research stakeholders have been considered in research design or conduct Strengths and limitations critically discussed Ratings of included studies according to the QuADS Criteria |

Cite this article as: Braun, A., Löwe, B., and Uhlenbusch, N. (2025). Peer Support in Chronic Conditions from the Peer Supporters’ Perspective: A Systematic Review. Psychosocial Intervention, 34(3), 175 - 188. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2025a14

Correspondence: an.braun@uke.de (A. Braun).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS