Group Counseling of Values Clarification to Increase Middle School Students’ Empathy

[Terapia de grupo de clarificación de valores para incrementar la empatÃa de los estudiantes]

I. Made Sonny Gunawan1, Mungin E. Wibowo2, Edy Purwanto2, and Sunawan Sunawan2

1Institute of Teacher Training and Education Mataram, Indonesia; 2State University of Semarang, Indonesia

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2019a5

Received 6 August 2018, Accepted 27 December 2018

Abstract

This research compared the effectiveness of two techniques for administering group counseling focused on values clarification: modeling vs. role play. Effectiveness was measured in terms of participants’ empathy at three time points, using a mixed factorial design. Participants were 40 students from a middle school in Mataram, Indonesia, who completed the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE). Results of three ways mixed ANOVA showed that the two techniques of administering group counseling focused on values clarification were both effective in increasing participants’ empathy, although modeling appeared to be the most effective approach and is likely to be more efficient. Female students’ empathy was higher than males’, but there was no evidence that one group counseling technique worked better for girls than for boys. The results are discussed in terms of their implications for future studies and intervention.

Resumen

Esta investigación comparó la efectividad de dos técnicas para administrar terapia de grupo basada en la clarificación de valores: técnica de modelado frente a juego de roles. La efectividad se midió mediante la empatÃa de los participantes en tres momentos, empleando un diseño factorial mixto. Los participantes fueron 40 estudiantes de una escuela intermedia de Mataram, Indonesia, que cumplimentaron el Cuestionario de EmpatÃa Cognitiva y Afectiva (QCAE). Los resultados de tres formas mixtas de ANOVA mostraron que las dos técnicas de administración de terapia de grupo centradas en la clarificación de valores fueron efectivas para aumentar la empatÃa de los participantes, aunque la técnica de modelado parecÃa ser el enfoque más eficaz y probablemente el más eficiente. La empatÃa de las estudiantes femeninas era más alta que la de los varones, pero no habÃa evidencia de que una técnica de terapia de grupo funcionara mejor para las chicas que para los chicos. Se discuten los resultados en cuanto a su implicación para el estudio e intervención futuros.

Palabras clave

Terapia de grupo, Clarificación de valores, EmpatÃa, Modeling, Juego de roles.Keywords

Group counseling, Values clarification, Empathy, Técnica de modelado, Role play.Cite this article as: Gunawan, I. M. S. , Wibowo, M. E. , Purwanto, E. , & Sunawan, S. (2019). Group Counseling of Values Clarification to Increase Middle School Students’ Empathy. PsicologÃa Educativa, 25, 169 - 174. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2019a5

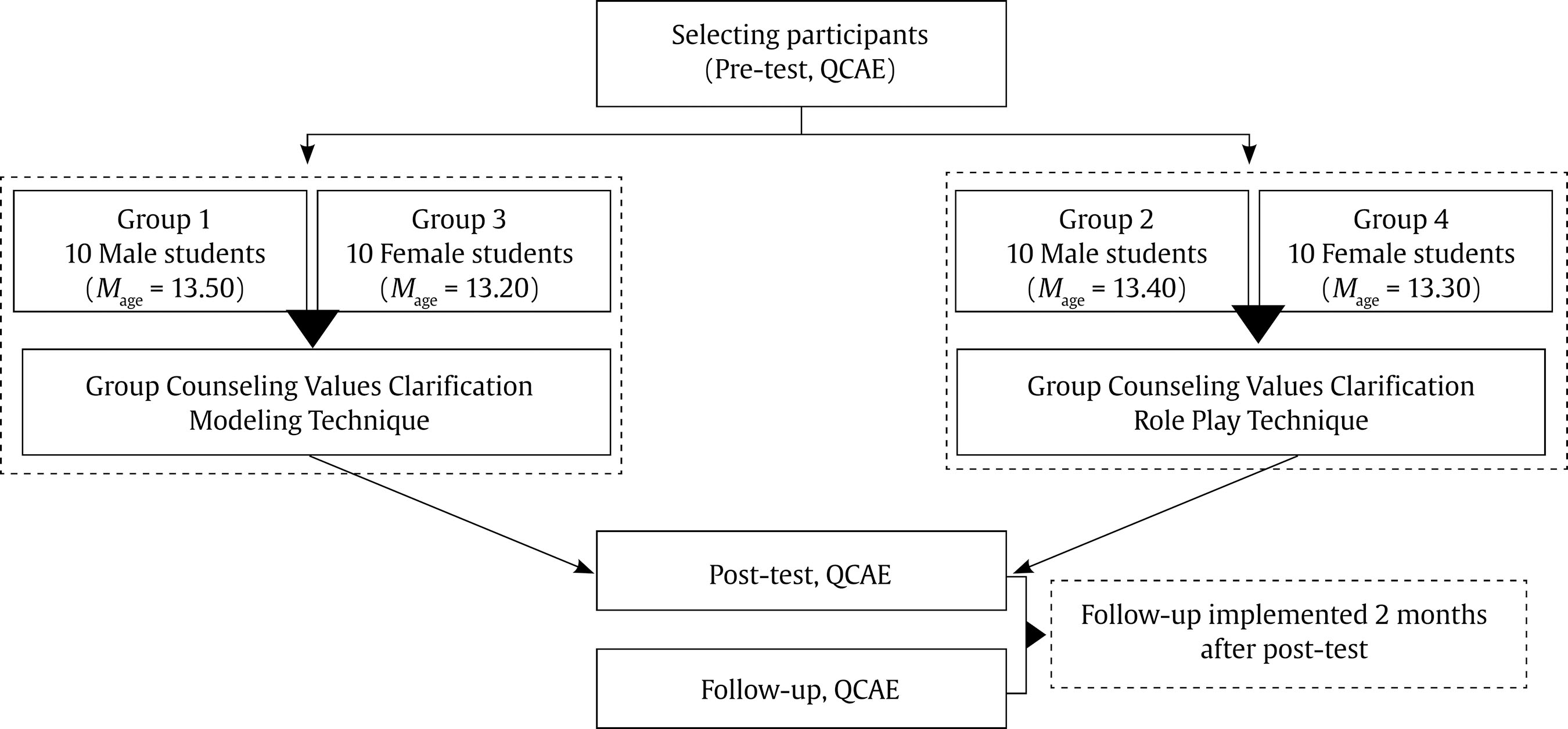

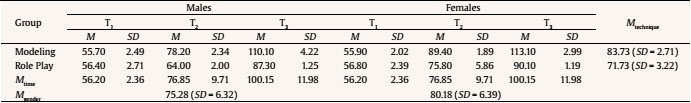

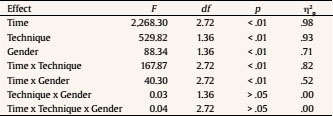

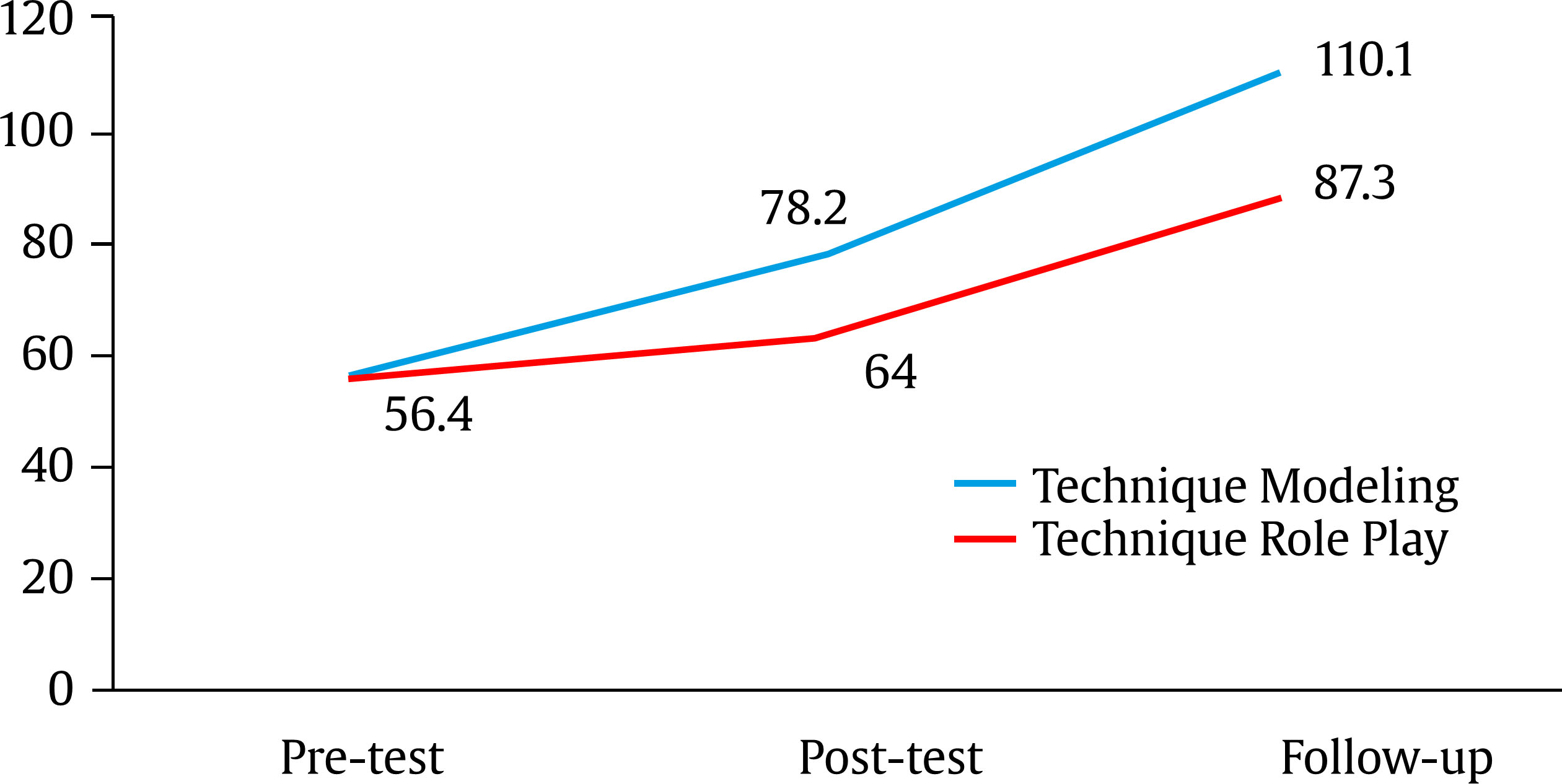

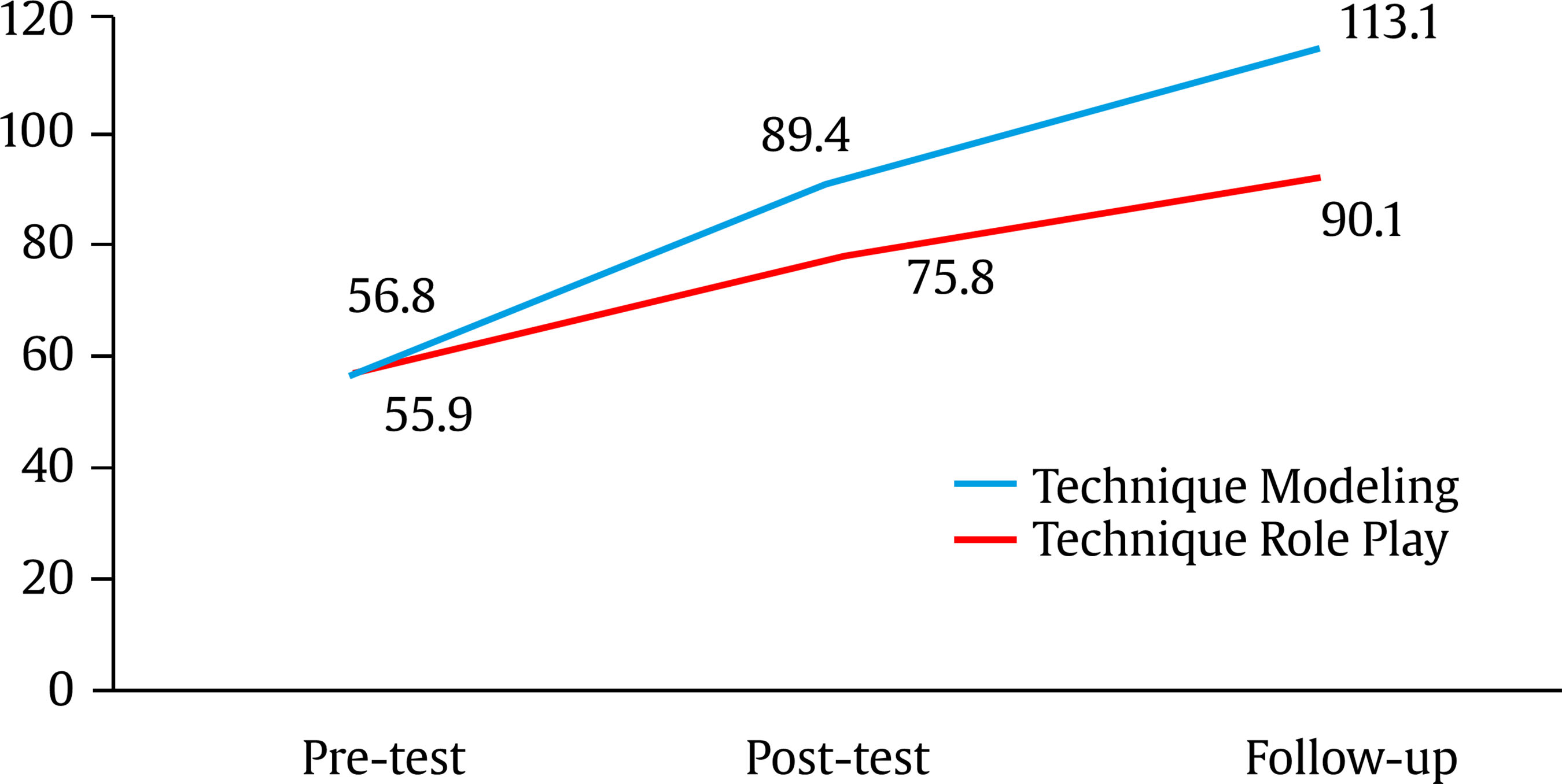

Correspondence: imadesonnygunawan@ikipmataram.ac.id (I M. S. Gunawan).Empathy is a process of knowing and feeling other people’s emotional experiences and values, a process that is at the center of human interaction (Cooper, 2011). Empathy is highly related to one’s cognition, perception, and process of communication (Eikeland, Orenes, Finset, & Pedersen, 2014), interpersonal relationships, individual characteristics (Fittness & Curtis, 2005), emotion, behavior, and morality (Hojat, 2007). Further, Hoffman (2000) and Jolliffe and Farrington (2006) argued that empathy is important because it enhances people’s ability to develop their sense of norms and becomes the source of morality (Goleman, 1995). Empathy has an empirical relation to various behaviors, such as responsibility, friendship, peace seeking, respectfulness, honesty, tolerance, and other human values (Dereli & Aypay, 2012). Seen from a cultural point of view, it is a universal form of assistance of moral behavior (Matsumoto, 2000). The current study focused on the development of students’ empathy. It is very important to develop students’ empathy to improve their adherence to norms and values during their school lives (Aslanargun, Kilic, & Bozkurt, 2014). Empathy is the basis of moral behavior, a societal expectation for young and old people alike. The most important aspect that needs serious consideration in developing empathy is the direct modeling of norms, as it affects students’ understanding of morality values (Koseki & Berghammer, 1992). Further, previous research findings revealed effective techniques for developing students’ empathy with activities and the use of relevant resources (Bonvicini et al., 2009) by focusing on structure and teaching methods (Afghani, Besimanto, Amin, & Shapiro, 2011; Williams, Brown, McKenna, & Palermo, 2015). However, nowadays, many schools have not fully lived up to their roles in improving students’ empathy (Priestley, 2000). A question may arise as to how a school counselor could contribute to meeting this goal. A professional school counselor should work on the basis of values and should be active in facilitating the education program. Thus a counselor, as a part of a school team and school activities, needs to increase students’ adherence to norms and moral values (ASCA, 2016). Furthermore, a school counselor models norms and values, and takes into consideration moral principles in fostering students’ empathy and empathic values (Neukrug, 2012). Cooper (2011) suggested conceptualizing the level of empathy based on children’s age and the modeling they observe during the process of teaching and learning. The older the students, the more likely empathy can be improved (Nunes, Williams, Bidyadhar Sa, & Stevenson, 2011), with the exception of children who are at puberty (Lennon & Eisenberg, 1987, cited in Farrow & Woodruff, 2007), who is an important potential for developing student-oriented empathy because at a young age students begin to learn to understand their social life (Santrock, 2007). While appropriate modeling within the teaching-learning process can enhance students’ understanding of the contents of the lesson (Lickona, 2012), modeling aimed at improving empathy can expose the quality of interaction, teaching-learning, and particularly the reach of moral development. The modeling that increases students’ empathy can be provided through short movies (Erford, 2015). Role play can also be useful for teaching empathy (Tolan & Landrum, 1995). During this process, a school counselor can improve students’ generalized empathy by helping them consider factors outside of their values. Past researchers also reported that the most utilized and applicable ways to improve students’ empathy are through training (Eikeland et al., 2014; Nunes et al., 2011). This element of training can now be seen in schools with a focus on values clarification (Lickona, 2012; Santrock, 2007). The application of values clarification can be conducted through individual and group counseling (Kirschenbaum, 2013). Values clarification is a method that assists students in identifying their norms, values, feelings, ideas, and important decisions that they make based on real life (Easterbrooks & Scheetz, 2004; Hall, 1973). In the current research, values clarification was accomplished through group counseling that led to decide their purpose, direction, and prioritized values as a basis for increasing empathy. Values clarification is effective in various settings. Its effect has been documented in students’ cortisol reactivity to acute stress (Gregg, Namekata, Louie, & Chancellor-Freeland, 2014), midwifery students’ attitudes toward abortion (Mplei & Botma, 2014), senior high school students’ lower dropout rates (Oliha & Audu, 2015), elementary school students’ improved moral values (Rai, 2014), and cancer patients’ improved decision making abilities (Feldman-Steward et al., 2012). On the other hand, Lockwood (1978) challenged researchers in this area to test the effectiveness of values clarification by (1) stating research objectives that are relevant to the goals of values clarification; (2) utilizing reliable and valid measures of the dependent variable; and (3) applying appropriate research methodology. The current study was conducted in line with these standards. The values clarification approach was studied in relation to improvements in students’ empathy by characterizing personal problems of empathic behavior (Kirschenbaum, 2013; Mickleburgh, 1992). A reliable and valid measure of empathy, namely the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (Reniers, Corcoran, Drake, Shryane, & Volm, 2011), was used to assess the dependent measures, namely the cognitive and affective components of empathy. This research adopted a longitudinal design where students’ empathy was measured at multiple time points (Creswell, 2015), namely prior to treatment (pre-test), at the end of treatment (post-test), and two months after treatment ended (follow-up). This research applied the values clarification approach in group counseling to improve the middle school students’ empathy. The results are expected to corroborate the results of earlier studies on the use of values clarification with modeling or role play techniques to improve students’ empathy. Also, this research tested differences in empathy level between male and female students, as female students are commonly found to be more empathetic than male students (Gonzalez-Serna, Serrano, Martin, & Fernandez, 2014). Background Theory Empathy The concept of empathy has been the focus of debate. A key question is whether it involves emotion, cognition, or both (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2004). Generally, empathy is a type of individual response to another person or other people (Pedersen, Draguns, Loner, & Trimble, 2008). In a specific way, empathy can refer to a form of emotional thinking that displays various feelings of others (Hojat, 2007). Therefore, the current study chooses a measure that includes but emotions and cognition to assess empathy. The elements that form empathy are antecedents, process, intrapersonal outcomes, and interpersonal outcomes in the form of helping behavior (Davis, 1996). Antecedents are the causes that influence the occurrence of empathy, where affective and cognitive responses are derived from specific situational contexts. Process is a scheme that describes a beginning and ending of a feeling of empathy, with empathy being based on a high level of understanding of the current situation. Intrapersonal outcomes are affective outcomes that are divided into things and reactive outcomes. Things include parallel outcomes or emotion matching, which refer to a harmony between what the individual feels and what others feel. Reactive outcomes are affective reactions toward others’ different experiences. Intrapersonal outcomes affect the observer, whereas interpersonal outcomes occur in the form of helping behavior. Empathy can be applied through counseling interviews (Eikeland et al., 2014) and training (Afghani et al., 2011; Bonvicini et al., 2009; Nunes et al., 2011; Williams et al., 2015). Moreover, there are several instruments that can be used to measure the level of individual empathy, including the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (Reniers et al., 2011); Hogan Empathy Scale (Hogan, 1969), the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (Davis, 1983), the Impulsiveness Venturesome Empathy Inventory (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1978), and the Empathy Quotient (Baron-Cohen et al., 2003). Group Counseling of Values Clarification The values clarification approach is based on the psychological humanistic theory (Oliha & Audu, 2015), which considers humans to be active individuals with the capacity to evaluate themselves (Feist & Feist, 2006). Values clarification is a counseling approach that focuses on assisting people to choose a direction, make a decision, and identify their priorities in reaching an objective (Kirschenbaum, 2013). In addition, values clarification is considered a method of moral education that can encourage the expression of empathy and other normative values (Kirschenbaum, 2000) and basic ethical principles (Oliha & Audu, 2015). Counseling of values clarification refers to a process that helps people use cognition and affect (Kirschenbaum, 1976) to decide on a purpose, and to develop a plan of action for reaching goals (Hart, 1976). The current study tested the effectiveness of group counseling of values clarification that utilized the steps of group counseling as outlined by Corey (2012), combined with the specific approach of values clarification (Kirschenbaum, 2013). The values clarification component has three levels and seven steps that are inserted into the activities (working stage) of group counseling, namely, (1) appreciation level – the goal of this level is that the counselees can be more aware of their values and can explain whatever they prioritize; this level has two steps: values appreciation and values confirmation; (2) choosing level – the goal is to assist counselees in broadening their concepts by using their imagination to produce new ideas and to assist counselees in making choices of their own for which they can be accountable; this level has three steps: alternatives, bringing up consequences, and choosing freely; (3) action level – counselees are expected to consider their values and to be consistent in applying their chosen values daily; this level has two steps: acting and acting consistently. Table 1 The Steps of Counseling Activities in Values Clarification Groups  Two techniques are commonly used to implement group counseling of values clarification, namely, modeling and role play (Mickleburgh, 1992). The modeling applied in this research involved illustrating target behavior through video recordings. According to Hallenbeck and Kauffman (1995), many research results show that the modeling technique is more effective when the counselees are able to perceive models that are similar to them. Role play is applied by giving a synopsis of stories related to moral dilemmas, then asking the group members to play a role, then being an observer (Tolan & Landrum, 1995). Various moral dilemmas are introduced, so that group members can understand a perspective that differs from their own (Erford, 2015). This research involved 40 middle school students (20 male and 20 female, Mage = 13.35, SD = 0.62), with 10 male students put in the modeling intervention group (Mage = 13.50, SD = 0.84), 10 other males put in the role play intervention group (Mage = 13.40, SD = 0.42), 10 female students put in the modeling intervention group (Mage = 13.40, SD = 0.69), and 10 other female students put in the role play intervention group (Mage = 13.30, SD = 0.48), based on random assignment of boys and girls. The participants were all grade VIII of a junior middle school in Mataram, Indonesia. The area in which the school is located is categorized at the middle-economic level (BPS-Statistics of Mataram City, 2018). Figure 1 Research Procedure.  Instruments The instrument that was utilized in this research was the Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE; Reniers et al., 2011). It includes 31 items (e.g., “I sometimes find it difficult to see things from the other guys’ point of view”) rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). This measure showed high reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha of .90 in the current sample. Research Procedure This research was conducted with grade VIII students in a junior middle school in Mataram, Indonesia. There were 324 students who completed the instrument at pre-test. Based on the results of the pre-test, 40 students with low levels of empathy were identified. Then, these students were randomly assigned to group of modeling (10 boys and 10 girls) and role play (10 boys and 10 girls). The group counseling intervention of values clarification lasted eight sessions, followed by the post-test assessment. A follow-up assessment was conducted two months after the end of the intervention. The data were analyzed using three ways mixed ANOVA. Within all sessions of group counseling of values clarification, the same resources were given to experimental groups with each session lasting 90 minutes 2 times in a week. Each session’s activities can be seen in Table 1, and the steps of the research can be seen in Figure 1. Descriptive Data Male and female students did not differ in age, t(38) = 0.00, p > .05. The characteristics of empathy score for boys and girls at pre-test (T1), post-test (T2), and follow-up (T3) by intervention technique can be seen in Table 2.. Table 2 Empathy Scores by Experimental Group and Gender, Time 1 through Time 3  Main Effects: Time, Technique, Gender The results of a 3 (time: pre, post, follow-up) x 2 (technique: modeling, role play) x 2 (gender: male, female) mixed ANOVA can be seen in Table 3. The main effect of on time empathy was significant, F(2, 72) = 2268.30, p < .01, η2p = .98. That is, there was an increase in empathy score in the total sample across time, T1 (M = 56.20, SD = 2.36), T2 (M = 76.85, SD = 9.71) and T3 (M = 100.15, SD = 11.98). The main effect of technique was significant, F(1, 36) = 529.82, p < .01, η2p = .93, with the modeling being more effective than the role play (MD = 12.00, SE = 0.52, p < .01). That is, both techniques were effective, but modeling was significantly more effective. The main effect of gender was significant, F(1, 36) = 88.34, p < .01, η2p = .71, with empathy being higher among female students than among male students (MD = 4.90, SE = 0.52, p < .01). Table 3 Analysis of Three Way Mixed ANOVA  Interaction Effects: Time x Technique, Time x Gender, Technique x Gender The above 3 (time: pre, post, follow-up) x 2 (technique: modeling, role play) x 2 (gender: male, female) mixed ANOVA also provided information about whether any main effects were moderated by other factors in the analysis. The interaction between time and technique in the prediction of empathy was significant, F(2, 72) = 167.87, p < .01, η2p = .82. That is, the group of modeling had a higher level of increasing of empathy at T3 than the other groups (see Table 4 and Figure 2 and 3). Table 4 Pairwise Comparisons of Experimental Group at Time 1 through Time 3  Figure 2 Increase in Empathy in Modeling vs. Role Play Groups for Male Students.  Figure 3 Increase in Empathy in Modeling vs. Role Play Group for Female Students.  The interaction between time and gender in predicting empathy scores was significant, F(2, 72) = 40.30, p < .01, η2p = .52. That is, the group of girls had a higher level of increasing of empathy at T3 than the other groups (see Figure 2 and 3). This research investigated the effectiveness of group counseling of values clarification, comparing two techniques, namely modeling and role play, to increase middle school students’ empathy. The results of the study corroborates those of earlier research conducted by Lockwood (1978). Both studies used values clarification to increase moral values, such as empathy, used a valid and reliable instrument to measure outcome, and used a complex experimental design. However, this is the first study of values clarification among Indonesian middle school of low economic standing. The research revealed that there was no significant difference between intervention groups (modeling, role play) in age or gender, which indicates that the distribution of participants was random, providing partial evidence of internal validity. The result of this research also showed that group counseling of values clarification is effective in improving students’ empathy. This is in line with the findings of Mplei and Botma (2015), who found that midwifery candidates showed increased empathy for abortion patients after the values clarification intervention; empathy was considered important for this population given that abortion trespasses many norm values. Other findings came from Rai (2014), who investigated the effectiveness of values clarification to improve elementary school students’ moral values in India. Rai concluded that the moral values were affected by others’ perspectives and the competence of the empathy. Empathy is seen as a moral paradigm (Goleman, 1995) and is empirically related to various kinds of behavior, such as being responsible, a friend, a peace seeker, loving, respectful, honest, and tolerant of other values (Dereli & Aypay, 2012). Empathy can be increased by using modeling and role play techniques because the process directly provides understanding that helps establish empathetic thoughts and feelings. The findings of this research demonstrate the effectiveness of modeling and role play techniques in improving students’ empathy. This is in line with prior results showing that the modeling using video (Williams et al., 2015) and the role play (Singh, Bhattacharyya, Veerwal, & Singh, 2017) were both effective but the modeling was more so. This supports research by Bailey, Deardorff, and Nay (1977), who investigated the effectiveness of the role play, feedback, tape recording, and modeling using video within a counseling simulation to change students’ behavior. It was concluded that the modeling using video was more effective in changing students’ behavior than the feedback and the role play. Thus, modeling is considered more effective than role play in improving students’ empathy. In modeling, behavior is illustrated through short videos that are observed directly by group members, students’ understanding can be increased, and it will be easier for them to show effective empathy themselves (Pervin, Cervone, & John, 2005). Implementation of modeling takes less time to learn others’ behavior (Bandura, 1997). In contrast, the role play in this research was implemented by giving synopses of stories to the students, who then do warm-up, action, and sharing and analysis. With these procedures, the students are more in the role of actor than observer, and lose some opportunities for observation (Tolan & Landrum, 1995). Also, the role play requires more time so that group members can understand the roles they are playing (James & Gilliland, 2003). The results showed that female students had higher empathy than male students. The results of this study corroborates former findings showing that female children have more empathy than male children (Gonzalez-Serna et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015). Similarly, there is a perception that women feel, entertain, and support emotional values more easily than men (Michener & Delamater, 1999). This statement is corroborated by Dokmen (cited in Dereli & Aypay, 2012), who asserted that female characteristics are perceived to be soft, polite, sensitive, merciful, responsive, and tolerant, while male characteristics are perceived to be brave, insistent, self-confident, authoritarian, dominant, assertive and ambitious, and being leaders and taking risks. Pursuant to the results of this research, it can be concluded that group counseling of values clarification group using modeling or role play was effective in improving junior middle school students’ empathy in Mataram, Indonesia. Although both techniques were effective, modeling was more effective; modeling has also been shown to take less time, and so may be more efficient than the role play technique in improving students’ empathy. Also, female students had a higher level of empathy than male students and were more responsive to the intervention. Limitations for Future Investigation This research was limited to studying increases in students’ empathy by using group counseling of values clarification with modeling and role play techniques. Future researchers can implement individual or group counseling by using a technique of biblioeducation, using books that narrate moral dilemmas or illustrate values (Mickleburgh, 1992), because it can provide information in improving understanding and raising awareness in problems experienced through reading books (Shechtman, 2002). In addition, empathy was conceptualized only as part of the values moral (Hoffman, 2000). Further, researchers can see empathy from the concept of interaction, such as the communication process, interpersonal relations, and personality characteristics (Fittness & Curtis, 2005). The sample included only students who were in the puberty phase – future researchers should also look at the effect of age on empathy. Cite this article as: Gunawan, I M. S., Wibowo, M. E., Purwanto, E., & Sunawan, S. (2019). Group counseling of values clarification to increase middle school students’ empathy. Psicología Educativa, 25, 169-174. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2019a5 |

Cite this article as: Gunawan, I. M. S. , Wibowo, M. E. , Purwanto, E. , & Sunawan, S. (2019). Group Counseling of Values Clarification to Increase Middle School Students’ Empathy. PsicologÃa Educativa, 25, 169 - 174. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2019a5

Correspondence: imadesonnygunawan@ikipmataram.ac.id (I M. S. Gunawan).Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS