The Role of Anxiety in the Relationship between Self-efficacy and Math Achievement

[El papel de la ansiedad en la relación entre la competencia percibida y el rendimiento en matemáticas]

María del Carmen Pérez-Fuentes1, Andrea Núñez1, María del Mar Molero1, José J. Gázquez1, Pedro Rosário2, and José C. Núñez3

1Universidad de AlmerĂa, Spain; 2Universidade do Minho, Portugal; 3Universidad de Oviedo, Spain

https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a7

Received 3 October 2019, Accepted 12 February 2020

Abstract

This study aims to improve current understanding of how the relationship between perceived math ability and math achievement may be mediated or moderated by levels of anxiety about math, considering intellectual abilities, gender, and school year. In this study, participants were 2,245 Spanish students (7th to 10th grade). All completed the FennemaSherman Mathematics Attitudes Scales and the Sternberg Triarchic Abilities Test. The main results showed that (i) perceivedcompetence is a potent predictor of achievement (the higher the perceived competence, the better the performance in mathematics), (ii) anxiety about mathematics significantly mediates the relationship between perceived competence and math achievement (although the effect is small), and (iii) levels of anxiety condition the intensity of the effect of perceived competence on math achievement (at high levels of anxiety the effect size of the relationship between perceived competence and achievement is large, whereas at low levels of anxiety the effect is small).

Resumen

El estudio tiene como objetivo mejorar el conocimiento actual sobre cómo la relación entre la capacidad matemática percibida y el rendimiento matemático puede estar mediada, o moderada, por el nivel de ansiedad ante las matemáticas, teniendo en cuenta las habilidades intelectuales, el género y el curso escolar. En el estudio participaron 2,245 estudiantes españoles de 7º a 10º grado. Todos completaron las Escalas de Actitudes Matemáticas Fennema-Sherman y la Escalade Inteligencia Triárquica de Sternberg. Los principales resultados mostraron que (i) la competencia percibida es un potente predictor de rendimiento matemático (cuanto mayor es la competencia percibida mejor es el rendimiento en matemáticas), (ii) la ansiedad ante las matemáticas media significativamente la relación entre la competencia percibida y el rendimiento matemático (aunque el efecto sea pequeño) y (iii) el nivel de ansiedad condiciona la intensidad del efecto de la competencia percibida en el rendimiento matemático (a un nivel de ansiedad elevado el tamaño del efecto de la relación entre la competencia percibida y el logro es grande, mientras que a un nivel bajo el efecto es pequeño).

Palabras clave

Ansiedad matemática, Rendimiento matemático, Competencia matemática percibida, Mediación, ModeraciónKeywords

Math anxiety, Math achievement, Perceived math ability, Mediation, ModerationCite this article as: Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Núñez, A., Molero, M. D. M., Gázquez, J. J., Rosário, P., & Núñez, J. C. (2020). The Role of Anxiety in the Relationship between Self-efficacy and Math Achievement. PsicologĂa Educativa, 26(2), 137 - 143. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a7

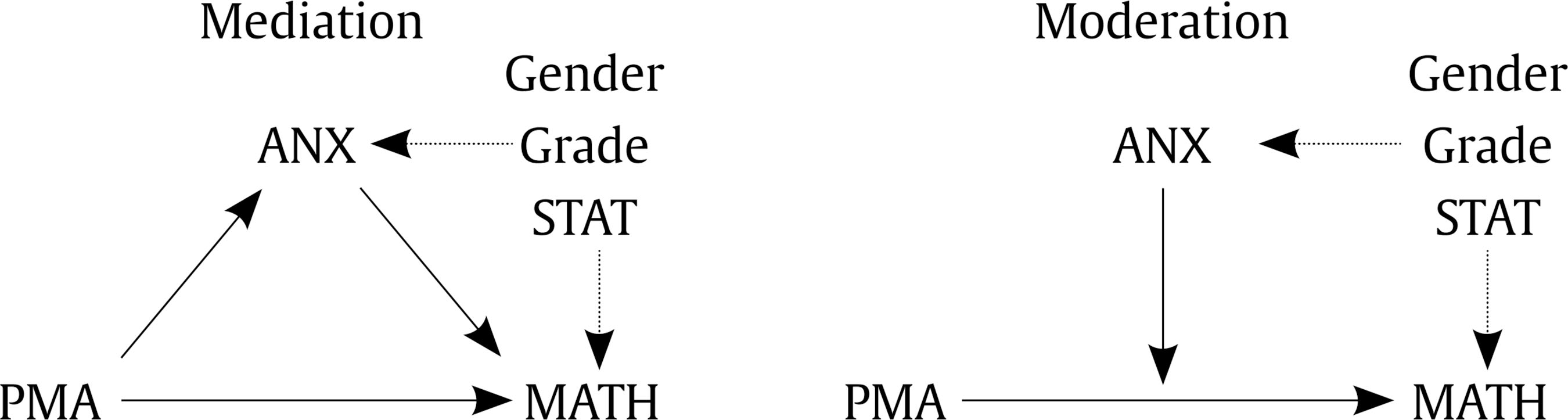

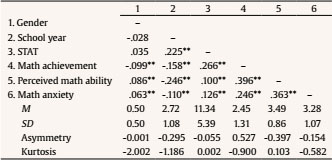

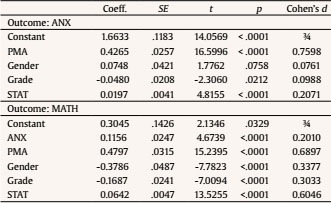

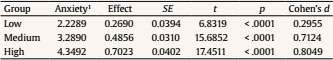

jcarlosn@uniovi.es Correspondence: jcarlosn@uniovi.es (J. C. Núñez)The European Commission has repeatedly highlighted the fact that the Spanish education system has not reached any of the objectives set for secondary students’ achievement (Valle et al., 2009). A recent report of the National Statistics Institute shows that Spain has managed to reduce the rate of school dropout over the last ten years from 31.7% to 17.3% in 2019. However, Spain is still one of the EU countries with the highest school failure rate for young people aged 18 to 24 (INE, 2019). These youth leave education having completed, at most, only the first part of secondary education (ESO). The mathematics subject is an expected concern for the Spanish school system, given the fact that math is involved in a wide range of activities and expertise in modern society. Understanding math is an absolute necessity in a society that is becoming ever more complex and technology-dependent. Nowadays, most sciences, including social sciences such as sociology, psychology, and economics, use more and more mathematical tools. Math is used in sport, dietetics, traffic management, population management etc. However, most academic difficulties and failures are concentrated in math. In fact, math acts as a basic “selective filter” in all educational systems. Failures of learning in math are not limited to the least capable. On the contrary, able students who can achieve high scores in other subjects exhibit poor results in math. Many students who have difficulties with math perceive learning as threatening experiences in which their school performance will be evaluated and their cognitive competence questioned, which is why avoiding learning opportunities is often what they feel to be the best choice. On the other hand, successful students face these episodes as opportunities to broaden their range of skills and therefore value them. As a result, successful students normally exhibit higher perceived learning competence, lower or moderate math anxiety, and good achievement compared to low performing students. These higher beliefs of self-efficacy not only increase motivation for learning, but also the process of self-regulation, making it easier to set ambitious learning objectives and facilitating self-monitoring behavior (Rosário et al., 2014). In contrast, students with low confidence in themselves about learning math tend to be more anxious about their learning and avoid leaning opportunities when they come up (García et al., 2016). Although we have learned a lot over the past sixty years about anxiety and its relationship with performance in math tasks (Dowker et al., 2016), there is still significant inconsistency in the results of past research about the role of non-cognitive variables such as anxiety and perceived competence in the explanation of math achievement, as well as hypothetical differences due to gender or school year (Ching, 2017; García et al., 2016; Hanin & Nieuwenhoven, 2016; Lipnevich et al., 2016). The data generally comes from studies assessing direct effects or the main effects of these variables on math achievement. This study aims to improve our current understanding by examining indirect and interaction effects in addition to principal effects. We examined how the relationship between Math Self-Efficacy (PMA) and Math Achievement (MATH) may be mediated or moderated by levels of Math Anxiety (ANX), considering intellectual abilities, gender, and school year. Math Self-efficacy and Math Achievement Self-efficacy refers to a person’s beliefs about their abilities to perform certain tasks and achieve goals (Bandura, 1977). According to this definition, these beliefs are specific to a domain, rather than being a global construct, which means that nowadays, self-efficacy is mainly used in a domain-specific sense (e.g., mathematics, or writing). Chen (2003) looked at beliefs of self-efficacy in 107 seventh grade math students and its relation to math achievement. The results of this study showed that those expectations have a powerful, direct, positive effect on the prediction of student performance in mathematics. Similar results have been found with Portuguese students from fifth- to ninth grade (Rosário et al., 2012), with British adolescents (Tosto et al., 2016), and with ninth- and tenth grade students in North America (Stevens et al., 2004). Using latent class analysis to relate self-efficacy expectations, self-concept, and math anxiety, Kvedere (2014) found evidence for two classes of students: (1) students with a positive mathematical self (high self-efficacy and self-concept and low math anxiety) and (2) students with a negative mathematical self (low perceived competence, low math self-concept, and high anxiety). In this study, and in others (e.g., Jain & Dowson, 2009), the relationship between perceived competence and math anxiety was negative. In contrast, the relationship between perceived competence and achievement seems to be reciprocal (Guay et al., 2003; Marsh & Martin, 2011; Valentine et al., 2004). Finally, various studies have shown that this relationship is moderated by gender. Recently, Henschel and Roick (2017) found that perceived competence interacted with gender in the determination of differences in math anxiety. Math Anxiety and Math Achievement Math anxiety is characterized by negative feelings towards math, which results in avoiding math classes and subjects based on math skills (Pizzie & Kraemer, 2017). Although it is usually accepted that the relationship between math anxiety and math achievement is curvilinear (Wang et al., 2015), it is usually approached from a linear perspective: as anxiety about a math task increases, execution worsens (Maloney & Beilock, 2012). In addition, while the level of anxiety is usually taken as a cause of math achievement (the debilitating anxiety model) rather than the reverse (the deficit theory), Carey et al. (2016) opted for a relationship with reciprocal effects (the reciprocal theory), even at very early ages (Gunderson et al., 2017). One recently studied additional topic was whether math anxiety and test or exam anxiety were manifestations of a general form of anxiety or the expression of specific anxieties (Mammarella et al., 2018). Similarly, math anxiety has been found to not affect all children or all types of math achievement equally (Ching, 2017). Cates and Rhymer (2003) examined the relationship between math anxiety, fluency, and the number of errors made by students in basic math operations. The results showed that the group with the highest math anxiety had considerably lower levels of fluency in all of the basic math operation tests. They also found that the relationship between math anxiety and math performance was more intense in middle-school education than in elementary education. Similar results were found by Ikegulu (2003), finding that students with the lowest levels of anxiety were more academically successful than those with moderate to high levels of anxiety. They also reported that students with high levels of math anxiety were much less interested in working on math or math-related activities. Ikegulu’s (2003) study found that when gender was considered along with anxiety, it explained close to 90% of the variance in the prediction of math performance. Female students perceived themselves as more anxious about math and male students perceived themselves to be better in their approach to and success with math. The results from Henschel and Roick (2017) were similar, girls exhibited significantly higher levels of (cognitive and affective) anxiety about math than boys, as and the also exhibited perceptions of being less competent in those tasks. In summary, a negative, significant relationship has consistently been found between math anxiety and math performance, from -.27 to -.34 (e.g., Chang & Beilock, 2016; Henschel & Roick, 2017; Ma, 1999; Suárez-Pellicioni et al., 2015). Compared to their less anxious classmates, students with high levels of math anxiety demonstrate lower math self-efficacy and poorer math skills (Ashcraft & Moore, 2009). One curious finding is from Hill et al. (2016), who found that despite girls exhibiting more math anxiety than boys (in secondary school), there were no significant differences between them in math achievement. According to the authors, this might indicate that girls have greater potential for math than boys. Goals of this Study Although there are many studies that have aimed to find the most important variables to explain math achievement in adolescent and pre-university students, the data they have produced is not consistent. Taking for granted the importance of real capability (for example, intellectual abilities), in recent years interest has grown in non-cognitive variables such as perceived math ability (PMA) and math anxiety (ANX) (e.g., Pitsia et al., 2017). Although data on the importance of PMA in explaining math achievement (MATH) is more consistent than data about the role of anxiety, it is often data on the direct effect of PMA and ANX on MATH. Data from previous research (eg, Jain & Dowson, 2009; Kvedere, 2014) indicated that perceived competence shows a significant and negative relationship with anxiety towards mathematics (the greater competition perceived, the less anxiety, and vice versa), and that anxiety is negatively related with mathematical performance (e.g., Chang & Beilock, 2016; Henschel & Roick, 2017; Ikegulu, 2003; Ma, 1999; Suárez-Pellicioni et al., 2015). Thus, acknowledging these findings it is possible to antecipate that anxiety plays a mediating role in the relationship between perceived competence and mathematical performance. To the best of our knowledge, no research has analyzed the mediator role of anxiety. Moreover, it is also feasible that anxiety may interfere in this relationship depending on the value of anxiety (that is, the intensity and the sign of the relationship between perceived ability and performance may vary depending on the levels of anxiety). The latter has not been addressed by literature. Therefore, in the current study, in addition to direct effects, we analyze the mediator role (indirect effect) or moderator role (conditional effect) of ANX in the effect of PMA on MATH. In these analyses the effect of real competence (intellectual abilities), gender, and school year will be statistically controlled for, due to their confirmed part in explaining the differences in MATH. Figure 1 represents the mediation and moderation models to be examined. Figure 1 Mediation and Moderation Models of Math Anxiety (ANX) in terms of the Relationship between Perceived Math Ability (PMA) and Math Achievement (MATH).   Bearing in mind data from previous research, which is abundant in terms of principal effects, but scarce in terms of mediation or moderation effects of anxiety, we have formulated the following three hypotheses: H1. The relationship between perceived math ability (PMA) and math achievement (MATH) is positive and statistically significant (the higher the PMA, the higher the MATH). H2. In addition to the above direct effect, there is a statistically significant indirect effect between PMA and MATH, via math anxiety (ANX) (mediation hypothesis: the higher the PMA, the lower the ANX, and the lower the ANX the higher the MATH). H3. The relationship between PMA and MATH may be conditioned by a student’s level of ANX (moderation hypothesis: the higher the level of anxiety, the weaker the relationship between PMA and MATH). Participants A total of 2,245 Spanish secondary school students from various schools in the north of Spain participated in this study (secondary education in Spain consists of four years of compulsory education, called ESO, followed by two years of Bachillerato; in this study the participants were all ESO students). The sample selection procedure was not random. Although schools were initially chosen at random, not all the selected schools agreed to participate. In addition, within the schools, a small number of students declined to participate for various reasons (being absent in one or more of the evaluation sessions, lack of permission from the family etc.). Gender subgroups were generally equivalent in number (1,122 girls, 49.97%, χ2 = 0.000, p > .05), although there were differences in terms of school year: 415 in first year (18.3%), 484 in second year (21.4%), 693 in third year (30.6%), and 671 in fourth year (29.7%), χ2(3) = 100.183, p < .05. However, gender percentages in each school year were practically the same: first year (9.4% girls, 9.2% boys), second year (10.1% girls, 11.3% boys), third year (15% girls, 15.6% boys), and fourth year (15.7 girls, 14% boys). Students with special educational needs and students in special support classes were not included in this study. Measures and Instruments Perceived math ability and math anxiety. Perceived math ability and math anxiety were determined from the corresponding subscales in the version of the Inventory of Attitudes towards Mathematics (IAM), adapted from the scale of evaluation of attitudes towards mathematics (FSS; Fennema & Sherman, 1976). It uses a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = completely false, to 5 = completely true). The perceived ability subscale has 5 items (for example, “I believe that I could master even the most difficult math tasks”). Math anxiety is measured by 5 items (for example, “When I work with math my mind goes blank and I can’t think clearly”). In the present study, both scales exhibit good reliability (perceived ability: α = .832, anxiety: α = .836), despite the small number of items. Real ability. To evaluate students’ intellectual abilities we used the Triarchic Intelligence Test (STAT) created by Sternberg (1993). This is a test to measure intellectual abilities according to the Triarchic theory of intelligence (Sternberg Triarchic Abilities Test). Its structure is the result of combining the three types of thinking (analytical, creative, and practical) with the (verbal, numerical, and figurative) content. Although it is possible to get a score for each subscale, in this study we only used total test score. As in other studies (e.g., Sternberg et al., 2001), in the present study it has adequate reliability (α = .748) and construct validity (fit for a unifactorial model: GFI = .986, AGFI = .976, CFI = .958, SRMR = .031, RMSEA = .044). Math achievement. Achievement in mathematics was determined from students’ final marks in mathematics subjects provided by the school secretaries, with prior permission from the participating students’ parents. Procedure This study was part of a larger piece of research in which various measuring instruments were applied in morning and afternoon sessions. The inventory of attitudes towards mathematics and the STAT were applied three months before the marks in math were awarded. Families of participating students were informed by the schools and given assurances of confidentiality, and were required to provide their written consent. Data Analysis The data was analyzed in two phases. Firstly, the descriptive characteristics of the variables were calculated, along with a correlation matrix. Secondly, in order to examine the research hypotheses, various regression analyses were performed using the PROCESS module in the SPSS 22 statistical package (Hayes, 2013). The effect sizes were evaluated using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988): (d < 0.20 = insignificant effect, d ≥ 0.20 & d < 0.50 = small effect, d ≥ 0.50 & d < 0.80 = moderate effect, d ≥ 0.80 = large effect). Preliminary Analysis Descriptive data and the correlation matrix are presented in Table 1. Almost all of the correlation pairs were statistically significant. The correlations indicate that girls perform significantly better in mathematics than boys, despite perceiving themselves to be less able than boys in this subject and exhibiting less anxiety. In addition, as students advance through the school years, math achievement is lower, they perceive themselves to be less capable in math, and math anxiety is lower. The correlations also suggest that math achievement is higher when perceived ability is higher and anxiety is greater. Finally, and unexpectedly, the relationship between perceived math ability and anxiety is positive (the greater the perceived math ability, the higher the anxiety). Looking at the mean values of the variables we see that math achievement is in the middle of the scale, whereas mean perceived ability and math anxiety are higher than the midpoints of the scales. Finally, the three main variables of study (perceived ability, anxiety, and math achievement) exhibit values of asymmetry and kurtosis close to zero, which indicates that the distribution of scores can be considered normal. Table 1 Pearson Correlation Matrix and Descriptive Statistics (Mean, Standard Deviation, Asymmetry, and Kurtosis)   Note. Gender (girls = 0, boys = 1); school year (first = 1, second = 2, third = 3, fourth = 4); math achievement (1 = minimum, …., 5 = maximum); perceived math ability (1 = minimum, …, 5 = maximum); math anxiety (1 = minimum, …, 5 = maximum); STAT (Sternberg Triarchic Abilities Test) (0 = minimum, 31 = maximum). *p < .05, **p < .0. Mediation Analysis To evaluate the mediating role of math anxiety (ANX) in the relationship between math self-efficacy (PMA) and math achievement (MATH) mediation analysis was performed using the PROCESS program in SPSS. Gender, school year, and STAT were used as covariables. Table 2 gives the data from the mediation analysis. The regression model explains a significant amount of the variance, both in ANX, R2 = .3824, R2adjusted = .139, F(4, 2180) = 93.3240, p < .0001, and especially in MATH, R = .5023, R2adjusted = .251, F(5, 2179) = 147.0921, p < .0001). Table 2 Analysis of the Mediating Role of Anxiety in the Relationship between Perceived Math Ability and Math Achievement   Note. ANX (math anxiety); PMA (perceived math ability), STAT (Sternberg Triarchic Abilities Test), MATH (math achievement); gender (girls = 0, boys = 1); school year (irst = 1, second = 2, third = 3, fourth = 4); MATH (1 = minimum, …., 5 = maximum); PMA (1 = minimum, …, 5 = maximum); ANX (1 = very low, …, 5 = very high); STAT) (0 = minimum, 31 = maximum). The data in Table 2 supports the first two research hypotheses. Firstly, the relationship between PMA and MATH is statistically significant (b = 0.4797, p < .0001), with a moderate effect size (d = 0.6897), indicating that the higher the PMA, the higher the MATH. Secondly, it gives empirical evidence supporting the medication hypothesis of ANX in the PMA-MATH relationship (indirect effect: b = 0.0493, z = 4.4915, p < .0001). We find that, for example, the higher the PMA, the greater the ANX (b = 0.4265, p < .0001, d = 0.7598) and the higher the ANX, the higher the MATH (b = 0.1156, p < .0001, d = 0.2010), with moderate and small effect sizes, respectively. It indicates that the total effect of PMA on MATH is large (b = 0.5289, p < .0001, d = 0.8210). Finally, the statistical control of covariables produced interesting results both in terms of ANX (very small or small effect sizes) and mainly with respect to MATH the effects are statistically significant (small or moderate effect sizes). Data suggests that (i) girls perform better than boys (although they exhibit less anxiety), (ii) students’ performance is worse as they go up through the school years, and they are less anxious about math, and (iii) the greater a student’s intellectual abilities, the higher their anxiety and the better math achievement. Moderation Analysis Using the variables gender, school year, and intellectual abilities as covariables, the moderator role of anxiety in the effect of perceived math ability on math achievement was analyzed. The data support the third study hypothesis: the relationship between PMA and MATH is conditioned by the different levels of ANX (b = 0.2043, p < .0001), although the effect size of the interaction is small (d = 0.3769). The increase in the explained variance of the model due to moderation is statistically significant, F(1, 2178) = 74.9389, p < .0001. Finally, the model explains 27.72% of the variability of MATH, F(6, 2178) = 139.2259, p < .0001). The three covariables included in the model were found to be significantly associated with math: gender (b = -0.3471, p < .0001, d = 0.3132), school year (b = -0.1495, p <.0001, d = 0.2715) and STAT (b = 0.0602, p < .0001, d = 0.5705). Table 3 details the results of the moderation effect of math anxiety. The PROCESS module subdivides the total group of subjects into three subgroups (low, medium, and high) using the cut-off scores corresponding to the 33rd and 66th percentiles in the measure of anxiety. In this way, it is possible to appreciate how the level of anxiety (low, medium, or high) affects the intensity, and sign, of PMA and MATH relationship. Data suggests that at every level of anxiety (low, medium, high) the effect of PMA on MATH is statistically significant, and it increases as the level of anxiety increases. At low levels of ANX the size of the effect of PMA on MATH is small (b = 0.2690, p < .0001, d = 0.2955), at medium levels of ANX, the effect size is moderate (b = 0.4856, p < .0001, d = 0.7124), and with high levels of ANX, the effect size is large (b = 0.7023, p < .0001, d = 0.8049). Table 3 Conditional Effect of Perceived Math Ability on Math Achievement at Different Levels of Math Anxiety   1 Levels of anxiety: low (minimum score to 33rd percentile), medium (33rd percentile to 66th percentile), high (66th percentile to maximum score). The relationship between perceived math ability and math achievement has been widely studied, producing very consistent data. To a greater or lesser extent, most studies have found the relationship to be strong and positive, indicating that the greater the perceived ability, the better the math achievement (and vice versa). What has been less researched is how that relationship can change (in magnitude, direction and type) when possible mediating or moderating variables are considered. One of those variables, which has been repeatedly associated with learning and math achievement, is anxiety. Because of that, in this study we have attempted to learn whether the relationship between perceived math ability and math achievement was mediated, at least partially, by anxiety, or if this relationship may differ (in intensity or direction) depending on anxiety levels. To examine the models of mediation or moderation, we used gender, school year, and students’ real abilities (intellectual abilities) covariables in order to statistically control for their effects. We formulated three hypotheses: (i) that PMA would significantly determine MATH, (ii) that ANX would mediate this association, and (iii) that the relationship between PMA and MATH would be conditioned by the levels of ANX. Our data generally confirm these three hypotheses. Firstly, we found that when PMA is high, MATH is also high, with moderate effect sizes in the mediation model (d = 0.6897) and large effect sizes in the moderation model (d = 0.963). These results are in line with past research (Guay et al., 2003; Marsh & Martin, 2011; Rosário et al., 2012; Stevens et al., 2004; Tosto et al., 2016; Valentine et al., 2004). Data regarding the covariables in this study are also in line with existing research (e.g., Henschel & Roick, 2017; Hill et al., 2016; Ho et al., 2000; Utsumi & Mendes, 2000; Williams et al., 2016) in that girls, despite reporting lower perceived math ability than boys, exhibit better math achievement. However, both boys and girls, as they go up through the school years, report lower anxiety and exhibit lower math achievement. The effect sizes of gender and school year are small however, both in the mediation and moderation models. Secondly, data from our study suggest that anxiety partially mediates the relationship between perceived math ability and math achievement, although the effect size of the mediation is small. Nonetheless, this mediation is based on relationships of a different direction to those found in some other studies. While in our study the relationship between PMA and ANX is positive, with a large effect size, indicating that the greater the PMA, the higher the ANX, other studies have found it to be negative (e.g., Jain & Dowson, 2009; Kvedere, 2014). Similarly, the relationship between ANX and MATH was positive in our study, albeit with a small effect size, whereas other studies have found it to be negative (e.g., Ashcraft & Moore, 2009; Chang & Beilock, 2016; Henschel & Roick, 2017; Ikegulu, 2003; Ma, 1999; Maloney & Beilock, 2012; Ramirez et al., 2016; Suárez-Pellicioni et al., 2015). This sequence of negative relationships was interpreted to mean that the more confidence a student had in their ability to complete math tasks well, the less anxious they would feel when faced with similar tasks in the future, and the less anxious they feel, the better their math achievement. However, in our study we find a series of positive relationships. How can we explain this apparent contradiction with the majority of previous research? One plausible explanation may be that the higher the perceived ability, the greater the feeling of responsibility, and maybe the greater the fear of failing to perform to the level they believe they are capable of. In turn, this anxiety, rather than blocking the student, may provoke more mobilization of available resources and result in better than expected achievement. In contrast, if perceived ability is low, the fear of failure may be lower, as it is expected, and consequently that reduces anxiety about future tasks. With this combination, low confidence in oneself, together with a lack of anxiety, may lead to low mobilization of required cognitive resources (which often are available), and low math achievement may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. In future studies it would be extremely interesting to no longer look at the relationship between these three variables, but rather the complete explanatory hypotheses, maybe designing longitudional or repeated measure studies that might adequately capture the causal relationships implicit in the two hypotheses. One recent study (Caviola et al., 2017) reviewed past research which looked at how stress induction, manipulation of time pressure, and math anxiety could interfere with and/or condition the selection of strategies to solve arithmetic problems. The researchers concluded that, owing to the scant available literature, the questions could only be partially answered, and currently there is not much evidence of clear associations. Thirdly, we aimed to discover whether ANX also conditioned the relationship between PMA and MATH, something that previous research had not examined. Our data provide empirical evidence that the level of ANX significantly conditions the intensity of the effect of PMA on MATH. We found that as the level of anxiety increased, the effect of PMA on MATH also intensified. When anxiety was high, the size of the effect of PMA on MATH was also large, and when anxiety was low, the effect size was small. This means that when the subject experiences high levels of math anxiety, the importance of their confidence in themselves grows significantly as a determinant of math achievement. In contrast, when anxiety is low, their self-confidence is a much less potent determinant of performance. The data from our study suggests that the intensity of the relationship seen in other studies between PMA and MATH depends to a large extent on the level of ANX. Nevertheless, contrary to what we thought based on data from other studies (e.g., Wang et al., 2015), we did not find moderate levels of anxiety to be the best for deploying the necessary competencies for good learning and subsequent math achievement. Our data suggest that it is when anxiety is greatest that the effect of perceived math ability on math achievement is strongest and vice versa. In summary, data of our study does not allow us to affirm emphatically whether anxiety is mainly a mediating or moderating variable of the effect of perceived math ability on performance in mathematics. However, the size of the effect of the data obtained in our study seem to support the moderation hypothesis more than that of mediation. While a statistically significant indirect effect (mediation) was obtained, its size is small (pulling to very small). However, the size of the effect varies considerably when considering levels of anxiety (moderation): while perceived competence is minimally related to performance when math anxiety is low, this relationship is large in the presence of high levels of anxiety. Consequently, we can conclude that data of the present study suggests that anxiety mainly plays a moderating role of the effect of perceived ability on math performance. Future research could further clarify this issue, through the use of data collection strategies with greater guarantees or control (perhaps based on an experimental or quasi-experimental design). Implications for Educational Practice The results of our study confirm those from much other research in which perceived ability is a significant predictor of achievement in a particular task. Data suggests that math teachers should consider it as important to provide students with good (declarative and procedural) knowledge in class as it is to help them (create optimal conditions) to develop expectations of self-efficacy and results (Foley et al., 2017). In other words, it is essential to ensure that, through daily practice, students gain confidence in themselves about working and succeeding with math, because without that the student will face those daily tasks feeling insecure, lacking expectations of good results, and consequently will progressively become less involved, and stop learning and achieving in math tasks. Working on the level of perceived ability is crucial to positively affect students’ levels of responsibility, and in this way improve achievement in this academic area. Nonetheless, it is very likely that student anxiety comes from other sources in addition to levels of perceived ability. Potential sources include, for example, a teaching process which is not an optimal fit for a student’s pace or style of learning, a teacher’s feedback methods, or the interaction of these factors with the student’s character or personality, it may be parents’ expectations of their child’s performance, or the pressure they are under to achieve results that may be at the limit of their capabilities (Cohen & Rubinstein, 2017). Cohen and Rubenstein (2017) found that in order to better understand the etiology of math anxiety, multiple facets of the children’s upbringing must be considered. Our data shows that when levels of anxiety are high, it significantly increases the potential of PMA to mobilize cognitive and motivational resources needed for good achievement compared to low levels of anxiety. However, it is possible that high levels of anxiety due to variables that are external to the student (family upbringing patterns or specific teaching process variables) do not necessarily lead to better cognitive and motivational involvement of the student in math, and consequent better achievement. This would probably be because this socially determined anxiety does not impact the levels of perceived personal responsibility for future success. For this reason, it would be interesting to design studies that address this general hypothesis. Or more specific questions such as how are the social, cognitive and neural facets of anxiety related? Dowker et al. (2016) concluded that a need for many more interdisciplinary, longitudinal, and intervention studies was able to respond to this and other equally complex questions. Limitations of the Study This research, despite presenting apparently consistent data, from a broad sample of students, does have some limitations which should be considered when drawing conclusions or generalizing the results. One limitation that is very common to research in education is the use of self-reports to gather information on some variables. In our case, we used two subscales of the Inventory of Attitudes towards Mathematics to obtain data on PMA and ANX. It would be useful to examine the extent to which results obtained through other procedures, or using measuring instruments other than self-reports, agree with the results in our study. Similarly, it should be borne in mind that the MATH measure was obtained from the school marks in this subject. It is well known that school marks contain more information than mere student achievement. It is possible that the results of this study may change significantly if standardized tests of math achievement were used (for example, PISA style tests), producing stronger relationships. Finally, another limitation of our study was the strategy used to collect data. Although data was collected at two different time points (MATH after PMA and ANX), the design of the study was not experimental, which means it is not possible to interpret data in terms of causality (although it is done occasionally in describing the results). Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Pérez-Fuentes, M. del C., Núñez, A., Molero, M. del M., Gázquez, J. J., Rosário, P. & Núñez, J. C. (2020). The role of anxiety in the relationship between self-efficacy and math achievement. Psicología Educativa, 26(2), 137-143. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a7 Funding: This research received external funding from the Government of the Principality of Asturias, Spain. European Regional Development Fund (Research Groups Program FCGRUPIN-IDI/2018/000199). References |

Cite this article as: Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Núñez, A., Molero, M. D. M., Gázquez, J. J., Rosário, P., & Núñez, J. C. (2020). The Role of Anxiety in the Relationship between Self-efficacy and Math Achievement. PsicologĂa Educativa, 26(2), 137 - 143. https://doi.org/10.5093/psed2020a7

jcarlosn@uniovi.es Correspondence: jcarlosn@uniovi.es (J. C. Núñez)Copyright © 2026. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef JATS

JATS